A Sustainable Livelihoods Framework-Based - Unsworks ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of A Sustainable Livelihoods Framework-Based - Unsworks ...

ASustainableLivelihoodsFramework-BasedAssessmentoftheSocialandEconomic

BenefitsofFishFarminginEastNewBritainProvince

ShaniceTong

AthesissubmittedinfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeofMasterof

Philosophy

SCHOOLOFBIOLOGICAL,EARTHANDENVIRONMENTALSCIENCES

FACULTYOFSCIENCE

THEUNIVERSITYOFNEWSOUTHWALES

November2018

ORIGINALITYSTATEMENT‘Iherebydeclarethatthissubmissionismyownworkandtothebestofmyknowledgeitcontainsnomaterialspreviouslypublishedorwrittenbyanotherperson,orsubstantialproportionsofmaterialwhichhavebeenacceptedfortheawardofanyotherdegreeordiplomaatUNSWoranyothereducationalinstitution,exceptwheredueacknowledgementismadeinthethesis.Anycontributionmadetotheresearchbyothers,withwhomIhaveworkedatUNSWorelsewhere,isexplicitlyacknowledgedinthethesis.Ialsodeclarethattheintellectualcontentofthisthesisistheproductofmyownwork,excepttotheextentthatassistancefromothersintheproject'sdesignandconceptionorinstyle,presentationandlinguisticexpressionisacknowledged.’

Signed……………………………………………..............

Date……………………………………………..............

Copyright Statement ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/will apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.'

....................................

Authenticity Statement ‘I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor variations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.’

....................................

ii

INCLUSIONOFPUBLICATIONSSTATEMENT

UNSWissupportiveofcandidatespublishingtheirresearchresultsduringtheircandidatureasdetailedintheUNSWThesisExaminationProcedure.

PublicationscanbeusedintheirthesisinlieuofaChapterif:• Thestudentcontributedgreaterthan50%ofthecontentinthepublicationandisthe“primaryauthor”,ie.thestudentwasresponsibleprimarilyfortheplanning,executionandpreparationoftheworkforpublication

• ThestudenthasapprovaltoincludethepublicationintheirthesisinlieuofaChapterfromtheirsupervisorandPostgraduateCoordinator.

• Thepublicationisnotsubjecttoanyobligationsorcontractualagreementswithathirdpartythatwouldconstrainitsinclusioninthethesis

Pleaseindicatewhetherthisthesiscontainspublishedmaterialornot.

�This thesis contains no publications, either published or submitted for publication (if this box is checked, you may delete all the material on page 2)

�Some of the work described in this thesis has been published and it has been documented in the relevant Chapters with acknowledgement (if this box is checked, you may delete all the material on page 2)

� This thesis has publications (either published or submitted for publication)incorporated into it in lieu of a chapter and the details are presented below

CANDIDATE’SDECLARATIONIdeclarethat:

• IhavecompliedwiththeThesisExaminationProcedure• whereIhaveusedapublicationinlieuofaChapter,thelistedpublication(s)

belowmeet(s)therequirementstobeincludedinthethesis.

NameShaniceTong

Signature Date(dd/mm/yy)8/08/2018

Surname/FamilyName : TongGivenName/s : ShaniceHaLinAbbreviationfordegreeasgiveintheUniversitycalendar : MPhil

Faculty : FacultyofScienceSchool :

ThesisTitle :

BEESASustainableLivelihoodsFramework-BasedAssessmentoftheSocialandEconomicBenefitsofFishFarminginEastNewBritainProvince

Abstract350wordsmaximum:(PLEASETYPE)InPapuaNewGuinea(PNG)malnutritionfromalackofproteinisasignificantissue,particularlyforthemajorityofthepopulationlivingininlandruralareasofthemainland.Fishfarmingwasintroducedtoaddressthisissue,andtodate,moststudieshavefocusedonthehighlandsofPNG;itspotentialtoimprovelivelihoodsofcoastalcommunitiesispoorlyunderstood,particularlyfortheeasternislandsofPNG.Thisstudyinvestigatedhouseholds’availablecapitalsandevaluatedthesocialandeconomicpotentialofinlandfishfarminginEastNewBritain(ENBP).Thestudyutilisedamixedqualitativeandquantitativeapproachusingasustainablelivelihoodsandlifestyleanalysis(SLifA)framework.Datawerecollectedthroughahouseholdsurvey,animbeddedSWOTanalysisandfocusgroupdiscussions.ThestudyincludedthefourdistrictswhichmakeupENBP:Rabaul,Kokopo,GazelleandPomio.Intotal,56householdsurveysand5focusgroupswereconducted.Themethodscaptureddataonhouseholdcapitals,assets,production,marketingandlifestyle.Thereisanabundanceofsocialandnaturalcapital,butalackoffinancial,physicalandhumancapital.Socialcapitalwasthebiggestinfluenceonlifestyleandhelpedhouseholdscopewithemotionalandfinancialshocks.Thelackoffinancial,physicalandhumancapitalhadadetrimentaleffectonfishfarmers.Alow-levelofinstitutionalsupport,extensionservicesandtrainingwerekeybottlenecks.Whilenaturalcapitalwasabenefittoinlandfishfarming,farmerswerealsoimpactedbyfloods.Toaddressthelackofextensionservicesandsupport,trainingprogramsshouldbeprovidedtoprovincialofficerstotransfertechnicalknowledgetoexistingandinterestedinlandfishfarmers.ThegrowthoffishfarmingoverallinPNGrequiresmoregovernmentinterventionparticularlytofundinitialinvestmentandtraining,andbyregulatingpolicy.ThisstudyprovidesabaselineofdataforENBPfishfarmingdevelopmentandwillenablethePNGGovernmenttohavetargetedinterventionsthataddresslocalissues.Inlandfishfarmingisaviableoptiontofirstlyimprovehouseholdnutritionthroughproteinconsumptionand,secondly,asasourceofincomeforthepeopleofENBP.

Declarationrelatingtodispositionofprojectthesis/dissertation

IherebygranttotheUniversityofNewSouthWalesoritsagentstherighttoarchiveandtomakeavailablemythesisordissertationinwholeorinpartintheUniversitylibrariesinallformsofmedia,noworhereafterknown,subjecttotheprovisionsoftheCopyrightAct1968.Iretainallpropertyrights,suchaspatentrights.Ialsoretaintherighttouseinfutureworks(suchasarticlesorbooks)allorpartofthisthesisordissertation.

IalsoauthoriseUniversityMicrofilmstousethe350wordabstractofmythesisinDissertationAbstractsInternational(thisisapplicabletodoctoralthesesonly).

……………………………………………………………Signature

……………………………………..………………WitnessSignature

……….……………………...…….…Date

TheUniversityrecognisesthattheremaybeexceptionalcircumstancesrequiringrestrictionsoncopyingorconditionsonuse.Requestsforrestrictionforaperiodofupto2yearsmustbemadeinwriting.RequestsforalongerperiodofrestrictionmaybeconsideredinexceptionalcircumstancesandrequiretheapprovaloftheDeanofGraduateResearch.

FOROFFICEUSEONLYDateofcompletionofrequirementsforAward:

iii

Acknowledgements

IwouldliketoextendmygratitudetotheENBPparticipantsofthisstudy

whoshowedtruegenerositybywelcomingustotheirhomesandsharingtheir

experiences.

A/ProfJesSammut,youhavegoneaboveandbeyondinyourroleasa

supervisor.Yourinputandinsightshavebeenimmeasurable.

IacknowledgetheACIARandAquacultureunitofNFAfortheirassistance

andfundingduringmyfieldwork;MrJacobWaniandHaviniVira,thankyou.

ToEllisonSemi,JoeAlois,MicahArankaandJerryTobata,Iamgratefulfor

yourirreplaceableknowledge,guidanceandsupportduringmyfieldwork.

TheRoom601team;Angela,Elizabeth,Lara,Damon,Jenny,Bayu,Hatim,

Taylor,KarthikandMichael.Youhaveallbecomemysecondfamilyandithasbeen

bothanhonourandinspirationtoworkamongstyou.Specialmentionto

CharishmaRatnamwhosecommentsandperspectivealwayskeptmepushingme

todobetter.

Thankyoutomyfamily,friendsandJoshfortheendlesssupportand

encouragement;itdidn’tgounnoticed.Youallsetaprecedentashardworkersand

weremymotivationasIwrotethisthesis.

Thisthesisisdedicatedtomyparents,whogavemetheopportunitytogrow

upinPNGandfindmyownpath.Withoutyourloveandsupport,thisthesiswould

notexist.Thankyou.

iv

TableofContentsAcknowledgements .............................................................................................................iii

ListofFigures&Tables.....................................................................................................vii

GlossaryofAbbreviation................................................................................................... ix

Abstract ................................................................................................................................... xi

ChapterI:Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1

1.1InlandAquaculture.................................................................................................................................... 2

1.2AbriefoverviewofInlandAquacultureinPNG............................................................................ 6

1.3Problemstatement..................................................................................................................................11

1.4AimsandResearchQuestions ............................................................................................................14

1.4.1Overallaim .........................................................................................................................................14

1.4.2Researchobjectives ........................................................................................................................14

1.5Approach .....................................................................................................................................................15

1.6SustainableLivelihoodAnalysisframework................................................................................16

1.6.1Introducinglifestyleintothesustainablelivelihoodsanalysis ...................................19

1.6.2Vulnerabilitycontext .....................................................................................................................20

1.7Assets,CapitalsandCapabilities .......................................................................................................21

1.7.1Humancapital ...................................................................................................................................21

1.7.2Socialcapital ......................................................................................................................................22

1.7.3Financialcapital ...............................................................................................................................23

1.7.4Physicalcapital .................................................................................................................................23

1.7.5Naturalcapital ..................................................................................................................................24

1.8Structure ......................................................................................................................................................25

ChapterII:HistoryandLegislationofAquacultureinPapuaNewGuinea......26

2.1AquacultureinPNG.................................................................................................................................26

2.2HistoryofAquacultureinPNG ...........................................................................................................28

2.3AquaculturePoliciesandDevelopmentStrategiesinPNG ....................................................41

2.3.1Aquaculturelegislationandpolicy ..........................................................................................42

2.3.2Governmentprogramsrelatedtoaquaculture...................................................................49

2.4Summary......................................................................................................................................................51

ChapterIII:Methodology..................................................................................................53

3.1Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................53

3.1.1Studygroupdescription ...............................................................................................................54

3.1.2Theauthorsroleintheproject..................................................................................................56

3.2 Methods.................................................................................................................................................56

v

3.2.1Fishfarmersurveys........................................................................................................................57

3.2.2Focusgroups .....................................................................................................................................60

3.3Analysis ........................................................................................................................................................63

3.3.1Significanceandoutcomes ..........................................................................................................63

3.4LimitationsandEthics ...........................................................................................................................64

ChapterIV:ENBPFishFarmingCapitalsAvailableandBottlenecks.................66

4.0Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................66

4.1ENBPdemographics ...............................................................................................................................67

4.1.1SchoolinginENBP...........................................................................................................................69

4.1.2Involvementinfishfarming........................................................................................................71

4.1.3SpecieschoiceandpondsinENBP ..........................................................................................72

4.2ThecapitalsavailabletofarmfishinENBP..................................................................................74

4.2.1Social&humancapitals................................................................................................................74

4.2.2NaturalcapitalavailableinENBP.............................................................................................77

4.2.3PhysicalcapitalinENBP...............................................................................................................81

4.2.4FinancialcapitalsinENBP...........................................................................................................83

4.3 Social,EconomicandEnvironmentalBottlenecksforFishFarminginENBP........87

4.3.1 EconomicbottlenecksaffectingthefishfarmingindustryinENBP .................88

4.3.2 SocialconstraintsimpactingthefishfarmingindustryinENBP .......................93

4.3.3 EnvironmentalbottleneckshinderingfishfarminginENBP...............................98

4.4Summary................................................................................................................................................... 100

ChapterV:TheSocialandEconomicBenefitsofFishFarmingDevelopmentinPNG........................................................................................................................................ 102

5.0Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 102

5.1SocialBenefitsofFishFarming....................................................................................................... 103

5.1.1EastNewBritainbenefits ......................................................................................................... 103

5.1.2PapuaNewGuineabenefitsoffishfarming ...................................................................... 110

5.2TheEconomicBenefitsofFishFarming...................................................................................... 115

5.2.1EconomicbenefitsoffishfarmingtoEastNewBritain ............................................... 115

5.2.2EconomicbenefitsoffishfarminginPapuaNewGuinea ........................................... 118

5.3FarmerSurveySWOTAnalysis ....................................................................................................... 120

5.3.1Strengths .......................................................................................................................................... 121

5.3.2Weaknesses..................................................................................................................................... 125

5.3.3Opportunities ................................................................................................................................. 129

5.3.4Threats .............................................................................................................................................. 132

5.4ThePotentialNegativeImpactsofAquaculture............................................. 136

vi

5.5Summary................................................................................................................................................... 138

ChapterVI:SynthesisandConclusion....................................................................... 140

6.1Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 140

6.2MajorFindings ....................................................................................................................................... 141

6.3InteractionofMajorFindings .......................................................................................................... 143

6.4FutureResearch..................................................................................................................................... 146

6.5RecommendationsonFutureInterventions ............................................................................. 149

6.6Conclusion................................................................................................................................................ 157

References.......................................................................................................................... 158

AppendixA:SLAsurveyhouseholdquestionnaire............................................... 186

AppendixB:FocusgroupquestionstranslatedtoTokPisin ............................ 208

AppendixC:PhotosofFishPonds .............................................................................. 211

vii

ListofFigures&Tables

Figure1.1:MapofENBPandspecificareascoveredbystudy .................................... 13

Figure1.2:SustainableLivelihoodsFramework ............................................................... 18

Table2.1:ListofintroducedspeciestoPNGfrom1930’s-2000(adaptedfrom

Glucksman,West&Berra,1976) ............................................................................................... 35

Table2.2:ACIARprojectnativespeciespotentialintroductionspecies

(FIS/2004/065)................................................................................................................................. 40

Table2.3:Classificationoflevel1,2and3activities ....................................................... 44

Table2.4:UnlawfulenvironmentalhardasdefinedbyEnvironmentAct

(Amendment)2014.......................................................................................................................... 44

Figure2.1:TheprocessofgettinganenvironmentalpermitinPNG(PNGLNG

EnvironmentalImpactStatement2009) ................................................................................ 46

Table2.5:Finesforbeingguiltyofanoffencewithoutanenvironmentalpermit

................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Table3.1:ParticipantswithineachENBPdistrict ............................................................ 57

Table3.2:Questionsthemesrelatingtocapitalsinthefarmersurvey.................... 58

Table3.3:Focusgroupdiscussionparticipantsandlocations .................................... 62

Table4.1:DemographicsofEHPfarmersurvey2014andENBPfarmersurvey

2017 ........................................................................................................................................................ 68

Figure4.1:HighestlevelofschoolingforENBPfishfarmersfromsurveydata .. 70

Figure4.2:Reasonsforinvolvementinfishfarming ....................................................... 72

Figure4.3:SpeciesculturedinENBPfromsurveydata ................................................. 73

Figure4.4:SocialandculturalinvolvementintheENBPcommunity...................... 75

Figure4.5:CommunalresourcesutilisedinENBP ........................................................... 79

viii

Figure4.6:PrimarysourcesofpowerutilisedinENBP.................................................. 82

Figure4.7:AbreakdownofphysicalassetsoffishfarmersinENBP........................ 83

Figure4.8:ENBPIncomeandexpensesforeachsurveyedhousehold.................... 84

Figure4.9:AbreakdownofwhereENBPhouseholdsspendtheirsavings ........... 85

Figure4.10:Averageallocationofincome&expensesinENBP ................................ 86

Figure4.11:MainconstraintstofishfarmingfromENBPandEHPsurveydata 88

Figure4.12:MostcommoncombinationoffarmingactivitiesinENBP.................. 91

Figure4.13:SocialchangesinENBPoverthepastdecadementionedbysurvey

participants.......................................................................................................................................... 95

Figure4.14:ThemostcommoninfluencesonlifestyleinENBP ................................ 95

Figure5.1:LifestyleaspirationsfoundintheENBPfarmersurvey ....................... 107

Figure5.2:DifferentplacesforENBPfishfarmersgotoforsupport.................... 110

Figure5.3FishfarminginputsoverthreemonthsinENBP ...................................... 118

Table5.1:TheENBPSWOTAnalysis–rankedstrengths ........................................... 124

Figure5.4:SourcesoffingerlingsforfishfarmersinENBP.......................................124

Table5.2:ENBPSWOTAnalysiswithrankedweaknesses ........................................128

Figure5.5:PrimaryplacesfishfarmersweretrainedinENBP................................129

Figure5.6:Theseasonalityofproduction,consumptionandsalesforfishfarming

inENBP............................................................................................................................................... 129

Table5.3:SWOTanalysisopportunities ............................................................................ 131

Figure5.7:FeedsuppliedinENBP........................................................................................ 131

Table5.4:SWOTanalysisthreats .......................................................................................... 133

Figure5.8:MainmarketinENBP ..........................................................................................134

Table5.5:SummaryofSWOTfactorsforENBP.............................................................. 135

ix

GlossaryofAbbreviation

ACIAR–AustralianCentreforInternationalAgriculturalResearch

CEPA–ConservationandEnvironmentProtectionAuthority

DAL–DepartmentofAgricultureandLivestock

DASF–DepartmentofAgriculture,StockandFisheries

DEC–DepartmentofEnvironmentandConservation

DFID–DepartmentforInternationalDevelopment

DFMR–DepartmentofFisheriesandMarineResources

DSIP–DistrictServicesImprovementProgram

EIA–EnvironmentalImpactAssessment

EIS–EnvironmentalImpactStatement

ENBP–EastNewBritainProvince

FAO–FoodandAgricultureOrganizationoftheUnitedNations

FISHAID–FisheriesImprovementbyStockingatHighAltitudesforInland

Development

GIFT–GeneticallyImprovedFarmedTilapia

HAQDEC–HighlandsAquacultureDevelopmentCentre

JICA–JapanInternationalCooperationAgency

LARDEC–LowlandAquacultureResearch,DevelopmentandExtensionCentre

LLG–LocalLevelGovernment

LPYTF–LakePindiYaundoTroutFarm

NADP–NationalAgricultureDevelopmentPlan

NAqDP–NationalAquacultureDevelopmentPolicy

NARI–NationalAgricultureResearchInstitute

x

NDAL–NationalDepartmentofAgricultureandLivestock

NFA–NationalFisheriesAuthority

NGO–Non-governmentOrganisation

NSO–NationalStatisticalOffice

ODI–OverseasDevelopmentInstitute

OISCA–TheOrganizationforIndustrialSpiritualandCulturalAdvancement

OTML–OkTediMiningLimited

PDF–ProjectDevelopmentFund

PEEST-PoliticalEconomicEnvironmentalSocialTechnical

PICTs–PacificIslandCountriesandTerritories

PNG–PapuaNewGuinea

PNGDSP–PapuaNewGuineaDevelopmentStrategicPlan

RPNGC–RoyalPapuaNewGuineaConstabulary

SLA–SustainableLivelihoodAnalysis

SLifA–SustainableLifestyleAnalysis

SRSEP–SepikRiverStockEnhancementProject

SWOT–StrengthsWeaknessesOpportunitiesandThreats

WHO–WorldHealthOrganization

WP-WesternProvince

UN–UnitedNations

UNARI–UniversityofNatural

UNDP–UnitedNationsDevelopmentProgramme

UNESCO–UnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCulturalOrganisation

xi

Abstract

InPapuaNewGuinea(PNG)malnutritionfromalackofproteinisasignificant

issue,particularlyforthemajorityofthepopulationlivingininlandruralareasof

themainland.Fishfarmingwasintroducedtoaddressthisissue,andtodate,most

studieshavefocusedonthehighlandsofPNG;itspotentialtoimprovelivelihoods

ofcoastalcommunitiesispoorlyunderstood,particularlyfortheeasternislandsof

PNG.Thisstudyinvestigatedhouseholds’availablecapitalsandevaluatedthe

socialandeconomicpotentialofinlandfishfarminginEastNewBritain(ENBP).

Thestudyutilisedamixedqualitativeandquantitativeapproachusinga

sustainablelifestyleanalysis(SLifA)framework.Datawerecollectedthrougha

householdsurvey,animbeddedSWOTanalysisandfocusgroupdiscussions.The

studyincludedthefourdistrictswhichmakeupENBP:Rabaul,Kokopo,Gazelle

andPomio.Intotal,56householdsurveysand5focusgroupswereconducted.The

methodscaptureddataonhouseholdcapitals,assets,production,marketingand

lifestyle.Thereisanabundanceofsocialandnaturalcapital,butalackoffinancial,

physicalandhumancapital.Socialcapitalwasthebiggestinfluenceonlifestyleand

helpedhouseholdscopewithemotionalandfinancialshocks.Thelackoffinancial,

physicalandhumancapitalhadadetrimentaleffectonfishfarmers.Alow-levelof

institutionalsupport,extensionservicesandtrainingwerekeybottlenecks.While

naturalcapitalwasabenefittoinlandfishfarming,farmerswerealsoimpactedby

floods.Toaddressthelackofextensionservicesandsupport,trainingprograms

shouldbeprovidedtoprovincialofficerstotransfertechnicalknowledgeto

existingandinterestedinlandfishfarmers.Thegrowthoffishfarmingoverallin

PNGrequiresmoregovernmentinterventionparticularlytofundinitialinvestment

xii

andtraining,andbyregulatingpolicy.Thisstudyprovidesabaselineofdatafor

ENBPfishfarmingdevelopmentandwillenablethePNGGovernmenttohave

targetedinterventionsthataddresslocalissues.Inlandfishfarmingisaviable

optiontofirstlyimprovehouseholdnutritionthroughproteinconsumptionand,

secondly,asasourceofincomeforthepeopleofENBP.

1

ChapterI:Introduction

1.0 Introduction

Aquacultureisthefarmingofadiverserangeofaquaticorganismsusingnatural

resourcessuchasfreshwater,marinewaterorsoil(Bostocketal.,2010).Globally,

aquacultureisoneofthefastestgrowingfoodproducingsectors,particularlyin

poor,countriesthatfacefoodandnutritionalinsecurity(FAO,2018).Unlikethe

capturefisheriesindustry,thepotentialofaquaculturehasnotreachedareas

wherefoodandincomesecuritycouldbeimprovedupon(Ahmed&Lorica,2002).

Aquacultureisaboomingindustry,globallyproducing110.2milliontonnesof

aquaticorganismsin2016withanestimatedvalueofUSD243.5billion(FAO,

2018).Inlandaquaculture,particularlyinlandfishfarming,alsoknownas

freshwaterfishfarming,accountsfor40%oftheworld’scapturefinfishfisheries

andaquaculture,andisamainsourceofproteinandlivelihoodindeveloping

countries(FAO,2014).However,productivityishighlyvariableamongcountries

duetofarmers’capacity,accesstotechnologiesandlackofsupport,whichhave

hindereditsgrowth(Brummett,Lazard&Moehl,2008;Hambrey,Edwards&

Belton2007;Katiha,Jena,Pillai,Chakraborty&Dey,2005;Lasner,Brinker&

Nielsen,2016).

2

1.1InlandAquaculture

Inlandaquaculture–principallythefarmingoffreshwaterfinfish–isconsidereda

criticallyimportantactivityforproteinproductionindevelopingcountries

(Tidwell&Allan,2001).Aquacultureisparticularlyimportantforareastoofar

awayfromasourceoffishfrommaricultureandcapturefisheries,orincoastal

hinterlandswheresuitablelandcanbeconvertedtopond-basedfarmingsystems

(FAO,2008).Inlandaquaculturecanbepracticedinnumerouswayswithtanks

andcage-basedfarminginreservoirscommonlyusedtoproducefinfish.Cagesin

reservoirs,whileflourishing,requirestrictregulationtomonitortheir

environmentalimpact(Bostocketal.,2010).Cagescanbeusedindifferentplaces

suchaslakesandrivers(Silva,2003).However,pond-basedaquacultureisthe

dominantmethodforland-basedaquacultureglobally(Waiteetal.,2014;FAO,

2018).Pondsvaryinsizeandusefromsmallindividualpondsforhouseholduseto

large20-100hectareponds,whichareusuallyconvertedorintegratedrice

croppingsystems(Edwards,2015).Anincreaseininlandaquaculturehasthe

potentialforhighproductivityinthefuturewithtechnologyadvances(Subasinghe,

Soto&Jia,2009),andthepotentialtoaddressproteinneedsofruralcommunities

indevelopingcountries.

1.1.1TheroleofInlandFishFarminginfoodandincomesecurity

Inlandaquacultureprovided51.4milliontonnesoffood,andaccountsfor64.2%of

theworld’sfarmedfoodfishproduction(FAO,2018).Thetopthreeinland

aquacultureproducersbycontinentareAsia,AfricaandtheAmericas(FAO,2018).

3

Fishisanimportantsourceofprotein,particularlyindevelopingAsiancountries,

whereconsumptioninruralareasishigherthaninurbanareas(Deyetal.,2005;

Kautsky,Berg,Folke,&Larsson,1997);itspopularityindevelopingcountriesis

largelydrivenbythelowlabourcostsandaccesstolandandwaterresources

(Ahmed&Lorica,2002).

Inlandfishfarmingisoftenintegratedwithotherfarmedcroppingsystemssuchas

vegetableandricefarmsincountriessuchasBangladesh(Dey,Spielman,Haque,

Rahman&Valmonte-Santos,2013).Inrecenttimesfreshwaterpondaquaculture

producedamajorityoffinfish(FAO,2016).Inlandaquaculturecanbepracticedin

numerouswayswithtanksandcagearraysinreservoirsalsowidespread(Naylor

etal.,2000).Inlandaquaculturecanalsorangeinintensity,withsmall-scale

householdaquaculturethroughtolargecommercialproduction(Subasingheetal.,

2009).Smallinlandfishfarmsindevelopingcountriesoftenoperateassmall-scale,

family-runoperationsthatprovideacashcropandsourceofanimalproteinforthe

household(Brummet&Williams,2000).

Unsurprisingly,fish-producinghouseholdsconsumeahigherpercentageoffish

thanhouseholdsthatdonot,whichmeanstheyoftenhaveahighernutritional

statusthanothersintheircommunity(Ahmed&Lorica,2002;Deyetal.,2005).As

morefarmsproducefish,marketsupplyincreasestokeeppricesdown,allowing

otherhouseholdstogettheirintakeofprotein(Ahmed&Lorica,2002).Intermsof

employment,ifpoorindividualscannotaffordthelandneededforfishfarming

thereisstilltheopportunitytogainemploymentvialabourormanagementof

ponds(Bénéetal.,2016).

4

Fishfarmingisusuallynotthesoleincomeforahousehold,withmanyusingitto

supplementtheirdietasopposedtomakingittheirprimaryincome(Smith,Khoa

&Lorenzen,2005).Thediversificationoflivelihoodsisoftencommoninruralor

poorcoastalcommunitiesandhelpstocreatehouseholdproteinandincome

(Blanchardetal.,2017).Thosewhopracticeinlandaquacultureareoften

constrainedbylimitedaccesstoresourcessuchaslandandinfrastructure,andare

usuallyconsideredpoor(Tidwell&Allan,2001).Anotherlimitationforinlandfish

farmersistravellingtosellproduceatbiggermarketswithmanypreferringtosell

theirfishtonearbycommunities(Bostocketal.,2010).Technologicaldevelopment

andeffectivefishhusbandryknowledgewillallowdevelopingcountriestogainthe

fullspectrumofbenefitssuchasfoodsecurityanddiversificationoflivelihoods

(Edwards,2000;Rajan,Dubey,Singh&Khan,2016;Smith,Gordon,Meadows&

Zwick2001).

1.1.2GlobalTilapiaProduction

TheNileTilipaisoneofthethreemostcommonlyfarmedspeciesacrossthe

developingworld.TherearenineTilapiaspeciesusedinfishfarming,withmost

nativetoAfricaandcontributing7.6%ofoverallfreshwaterproduction(Bostock

etal.,2009;Gupta&Acosta,2004).KenyawasthefirsttocultureTilapiain1924

beforeitspreadintotheFarEast,thentheAmericasinthe1940sand1950s

(Gupta&Acosta,2004).Tilapiaproductionreached5.7milliontonnesin2015,and

tilapiaistradedinternationally(FAO,2016).ThemainTilapiaproducersare

developingcountriessuchasChinaandVietnam,withimprovedtechnologyand

5

fishhusbandryknowledgeallowingthecontinuedspreadofproduction(FAO,

2018;Yue,Lin&Li,2016).Ariseinfishconsumptionduetochangesinconsumer

attitudesandincreasedinmarketinghasdriventheriseintilapiaconsumption.

TheNiletilapia,Oreochromisniloticus,hasbeenintenselyculturedanddominates

globalproduction(FAO,2016;Wang&Lu,2016).Duringthe1980sand1990s

threespecificspecies(O.niloticus,O.mossambicusandO.aureus)wereprevalently

produced.O.niloticusproductionexpandedintotheAsianmarketinChina,

ThailandandIndonesia(Fitzsimmons,2000).

Tilapiaisomnivorousmeaningitrequiresminimalfeedsinceitalsousesnatural

foodandcanbefarmedinbothsaltandfreshwater(Bostocketal.,2010).These

requirementssuggestthatitisaffordableandeasytorearspecies,whichhis

particularlyimportanttosubsistencefarmers(Campos-Mendoza,McAndrew,

Coward&Bromage,2004).Tilapiaisconsideredalow-valuefishduetolow

productioncostscomparedtootherspecies,wherethespeciesoffarmedfishis

usuallydependentontheincomeofthefarmer(Ahmed&Lorica,2002).In

ThailandandthePhilippines,low-valuefishareusuallyfarmedinhigherquantities

inruralorpoorhouseholdsthanurbanhouseholds,duetoadifferencein

accessibilityofproteinsources(Deyetal.,2005).Tilapiacanbeculturedinmany

differentsystems,ranginginintensity.Themostcommonare:cages(Philippines),

ponds(China,Bangladesh)andtanks(Brazil)(Kumar&Engle,2016;Wang&Lu,

2016).

ThereareafewcommonkeyconstraintsfoundfromglobalTilapiaproduction;the

firstistheabilitytocontrolbreeding(Subasingheetal.,2009).Awidelyused

6

solutionforthisistoutiliseamalemono-sexpopulation,howeverthismaybe

difficultforsmall-scalefishfarmers(Gupta&Acosta,2004;Rokocy,2005)dueto

thecostofhormonesandtheadditionalspacerequiredforthenurserystage.Poor

broodstockproductivity,duetolowfecundityandinbreeding,isasignificant

limitationthataffectscommercialfishfarms(Campos-Mendozaetal.,2004;Dey,

2000).Thedeteriorationofgeneticqualityisaconstraintthataffectsallfarms

acrossallintensities(Dey,2000).Wherebreedingprogramsforselectionandsex

controlareemployed,improvedproductionandgrowthbenefitshaveoccurred

(Gupta&Acosta,2004).AnothersignificantlimitationforallTilapiafarmsisthe

lackofmarketing,developmentofinfrastructureandlackofinstitutionalsupport

neededtogrowhumancapital(Subasingheetal.,2009).Nevertheless,developing

countriesusetilapia,alongwithcarpspecies,asasourceofproteinand

supplementaryincome(Yueetal.,2016).

1.2AbriefoverviewofInlandAquacultureinPNG

PapuaNewGuinea(PNG)hasapopulationof8,084,991andisanaturallydiverse

countryconsistingofawiderangeofnaturalenvironments(TheWorldBank,

2017).Nearbycountries,suchasIndonesiaandVietnam,havehadmajorinland

freshwaterfishfarmingwhichhaseffectivelycreatedincomeandimprovedfood

security,particularlyinruralareas(Belton&Thilsted,2014;Pucher,Mayrhofer,

El-Matbouli&Focken,2015).About33%ofthePNGpopulationearnslessthan

US$1.25perdaywith87%ofthepopulationbeinginlandinhabitantslivingin

ruralareasandusingsubsistencefarmingandnaturalresourcestomeettheir

7

needs(FAO,2017).Duetoalackoflivestockproductionandadependencyonhigh

carbohydratefoods,49.5%ofthepopulationshowsstuntingfrommalnutrition

(WHO,2015).AlthoughPNGhashadalonghistoryofcrop-basedagriculture,with

75%ofthepopulationdependentonsubsistenceagriculture,fishfarmingisa

recentactivity(Bourke&Harwood,2009;UNDP,2012).Fishfarmingwas

introducedtoaddressfoodandincomesecurity,withmostfishfarmsbeing

earthenponds(Smith,2007).

InPapuaNewGuinea(PNG),aquacultureisgrowingatarapidrateof10%ayear

asshownbystudiesdonebyVira(2015)andAustralianCentreforInternational

AgriculturalResearch(ACIAR)projectFIS/2014/062.Smallinlandearthenponds

arethemainfarmingmethodusedforinlandfishfarming.Thesepondsconsist

predominantlyofTilapiaandEuropeanCarpthatarethemainmethodandspecies

offishfarming,particularlyinruralareasofPNG(Smith,2007).Since2006there

hasbeenasignificantincreaseinthenumberoffishfarms,specifically

communitieswithlessaccesstoresourcesthanthatofcoastalregions(Vira,2015).

1.2.1 OpportunitiesandConstraintsofaquaculturedevelopmentinPNG

AquaculturedevelopmentinPNGposesmanyopportunitiesandconstraints.Vira

(2015)conductedaStrengths,Weakness,OpportunitiesandThreats(SWOT)

analysisofEasternHighlandsProvinceinPNG.Therewereanumberofkey

opportunitiesfoundintheSWOTanalysis.Therewerethatfarmersremainedopen

totrainingandextension,demandforfishwasgrowing,educationalinstitutions

wereopentointroductionofaquacultureascontentforcourses,good

8

environmentalconditionsforfishfarmingarepresent,waterisfreelyavailable,

andfarmerswanttoimprovethequalityfishfeed.Threatsincludedalackofan

organisedmarket,slowgrowthoffishevenwithfeedandtheft,whichoverall

discouragesfishfarming.TheculturalconditionsinPNGcanalsobeanadvantage,

withpeoplerelyingonthecommunitywantoksystemforassistance(explained

furtherinSection1.2.3).

TheNationalFisheriesAuthority(NFA)CorporatePlan2008-2012identified

weaknessesfromacorporatepointofview:alackofmarketaccess;inadequate

onshoresupportfacilities(particularlyforcoastalfisheries);lackoftrainedstaff

andcrew;conducivebusinessclimateforinvestmentgoodgovernance;lackof

facilities;and,linkagewithotheragenciesorservices.Improvedtrainingthrough

institutionalsupportwasreiteratedbyACIAR(Smith,2007).Thesepointswere

alsorestatedbyVira’s(2015)SWOTanalysisoffishfarmersinPNG.Farmer-

relatedweaknessesincludealackoffishhusbandryknowledgeandskills,arelated

lackoftraining,andhighpriceoffishfeed.Highcapitalcostsofsettingupfish

farmswereanotherconstraint(Smith,2007).

PNG’saquaculturesectorhasnotseenthesamelevelofsuccessofother

developingcountries.Thisisdue,inpart,toalackofinfrastructure,andfinancial

andinstitutionalconstraintssuchaslackofmanagementandsupport.PNG’s

challengesindevelopingfishfarmingaremirroredbyAfrica.Withsimilar

economic,politicalclimateandpopulationgrowth,Africa’smainconstraintisthe

needfortrainingandculturalconstraintssuchasthelackoftraditionalfish

husbandryskills,mirroringtheneedsofPNGsfishfarmingindustry(Brummet&

9

Williams,2000).PNGalsohassocialconstraintsthataffectthesuccessof

communitymembersviathewantoksystem(see1.2.3).

1.2.2 CurrentInlandAquacultureresearchinPNG

CurrentandrecentresearchintoinlandfishfarminghasbeenconductedbyNFA

andUNSWwithfundingfromACIAR.AlargerACIARinlandaquacultureproject

(FIS/2014/062)isanactiveprojectthatisresearchingwaystoincrease

productionfrominlandaquacultureforfoodandincomesecurity.Partofthis

projectinvolvesconductinghouseholdsurveysin7otherprovinces:Manus,

Madang,WesternHighlandsProvince(WHP),EasternHighlandsProvince(EHP),

Cimbu,JiwakaandMorobe.ThisprojectwillfocusonENBP,whichwasoneofthe

lastprovincestobesurveyedmakingthetotalnumberofprovincessurveyed8.

ENBP,althoughastandaloneproject,waschosentoprovidemoreinformationon

coastalcommunitiesinvolvedinfishfarmingandprovideacomparativedataset

fortheumbrellaACIARproject.Thesurveysutilisedasustainablelifestyleanalysis

(SLifA)modifiedfromasustainablelivelihoodanalysis(SLA)frameworktocollect

dataonthestatus,availablecapitalsandbottlenecksforinlandfishfarminginPNG

(furtherdiscussedinSection1.6).Thisstudyutilisedthesamesurveyformatand

modifiedquestionstosuitthecontextofENBP.Thefindingsfromthiscomponent

ofthestudyisshapingstrategiesforresearchandmanagement.TheACIARproject

targetsthesignificantconstraintstohouseholdpondswhichwerethelackof

technicalcapacityandfishhusbandryknowledge.

10

1.2.3TheWantoksystem

PNGisacountryrichincultureandsocialcapital,withacomplexwebofnetworks

(Baynes,Herbohn&Unsworth,2017;Nanau,2011).Akeyexampleofsocialcapital

inPNGisthewantoksystem,whichisasystemofreciprocity.Wantoktranslatesto

mean‘onelanguage,orpeoplewhospeakthesamedialect’,butcanalsoreferto

commonkinship,socialorreligiousgroups,andethnicidentity(deRenzio,2000).

Itisanetworkofrelationshipsandbehaviours.Onamacro-level,itisanidentity

concept,whileonthemicro-level(i.e.householdandfamilies)itisasocialcapital

(Reilly,2001).Thewantoksystemcanoftenactassocialwelfaresupportbasedon

relationshipsoftrustandcooperationwithotherwantoks(deRenzio,2000).

Communitieswithahighlevelofsocialcapitalareconsideredtohaveabetter

chanceofsolvingproblemsthroughcollectiveactionandrelyingonother

memberstoreciprocatebasedontheirtrustinoneanother(deRenzio,2000).

Havinghighstocksofsocialcapitalalsopositivelyimpactseconomicand

governmentsectors(Fitz,Lyon&Driskell,2016).Thewantoksystemisbuilton

thevaluesandtraditionsofthecommunityandallowsforthesharingof

information.Thisfoundationofsharedinformationcanallowforagreateruptake

ofagriculturalimprovementtechniquesandmoreworkopportunities(Ngwira,

Johnsen,Aune,Mekuria&Thierfelder,2014;Sisifa,Taylor,McGregor,Fink&

Dawson,2016).Whilethewantoksystemcancreategreaterefficiency,itcanalso

bringaheavyburdentocertainmemberswho,forexample,havemoresupport

fromfamilyorearnahigherincomeandgiveothersa“free-ride”–wherepeople

takeadvantageofotherindividuals’capitalandreapthebenefits(Woolcock,

1998).Theamountofsupportanindividualhasisbasedonthegrouptheyarea

11

partofortheirfamilyconnections(Reilly,2001).Thewantoksystemissignificant

tofishfarminginPNGsincesharingnewagriculturalpracticesisoftendoneona

ruralcommunitylevelandhastheabilitytodevelopruralcommunities(Nanau,

2011;Pratiwi&Suzuki,2017).Fishfarmingalsoprovidesbenefitsforcommunity

householdnutritionandaddedfinancialcapital(Thilstedetal.,2016).

1.3Problemstatement

Thereiscurrentlyaknowledgegaponthesustainabilityofinlandfishfarmingfor

coastalprovincessuchasENBP,theavailablecapitalsandhowitsdevelopment

hasbeenhindered.Anincreasedpopulationhasledtooverfishingandsocial

tension,andfoodsecurityininland,ruralcommunitiesisoftenprecarious(Bellet

al.,2009).Therefore,fishfarmingwassuggestedbyNFAtoimproveeconomicand

socialgrowthwithinENBP,PNG(J.Sammut,personalcommunication,2Nov

2017).FishfarminghasbeenachallengeforPNGfarmers.Commercialor

advancedmethodsofproductionareoftentoohighforruraldwellers(Narimbi,

Mazumder&Sammut2018;Vira,2015).However,thereispotentialforsmall-scale

fishfarmstosucceedwhichisevidencedinareasoftheEasternHighlands

Province,JiwakaProvinceandWesternHighlandsProvince(Smith,2007).A

SustainableLivelihoodsandLifestyleFrameworkwasproposedbySammutand

Wani(2015),withothermethodsofdatacollectiontounderstandthefivecapitals

thataffectfishfarmingopportunities.Therehasbeennosurveyworkconductedin

ENBPwherepossibledifferentconstraints,lifestyleandlivelihoodassetsare

present.Thus,theproposedstudywillenableNFAandtheumbrellaACIARproject

12

tomakecomparisonsbetweenprovincesandplaninterventionsstrategicallyand

equitably.TheoverallACIARprojectandthisstudywillcontributetocreatingthe

largestsocio-economicdatabaseforfishfarminginPNGandabaseline.

Thepurposeofthisstudyistoutiliseanadaptationofasustainablelivelihood

framework(SLA)todetermineifthecommunitiesinEastNewBritainhavethe

capitalstoformasuccessfulandsustainablesourceofincomeandproteinthrough

inlandfishfarming.Thisprojectwillalsoprovideabetterunderstandingofthe

community’sprioritiesandcapitalsinrelationtofishfarmingasalivelihood.This

informationwillinformgovernmentagenciessuchasNFAandProvincial

authorities.ACIARisalargefunderofinlandfishfarmingresearchandother

fisheriesprojectsinPNG.Keyoutcomesofthisstudyareexpectedtoaddvalueto

theACIARproject(FIS/2014/062),generateinformationneededfordecision-

makingbyNFA,andtoidentifybottlenecksforindustrygrowthneededfor

researchandmanagementactivitiesinPNG.

1.3.1StudySite

EastNewBritainprovince(ENBP)isinNewBritainIsland,withapopulationof

~328,369peopleinthe2011census(NSO,2011).Theextentoffishfarmingin

ENBPiscurrentlyunknownandisnotcurrentlyincludedintheACIARproject’s

sustainablelifestyleanalysis(SLiFA).ThisstudywillbeundertakeninRabaul,

Gazelle,KokopoandPomiodistrict,whichmakeupENBP.Amajorityofpeople

fromGazelle,KokopoandRabauldistrictareTolai.TherearealsoBainingpeople

fromGazelledistrict,thathistoricallyarethoughttohavebeendisplacedbythe

13

Tolai.TherearethreeroutinelyspokenlanguageswhichareEnglish,TokPisinand

theTolaivernacularKuanua.Despitethecoastallocation,theislandregions

(Bouganville,ENBP,Manus,NewIslandandWestNewBritain)populationsstill

experiencestunting(38/1%)andenvironmentalconstraints(UNICEF,WHO&

WorldBank,2015).ENBPisatriskofearthquakes,volcaniceruptionsand

subsequentlandslidesduetoitslocationwithinthevolcanicringoffire(Kuna&

Zehner,2015).Thiscontributestopoorqualityroadsandlackofaccessibility,

makingsourcesofproteindifficulttoaccess.However,theproductionoffishis

foundtobeasoundsourceofproteinandcanbeproducedinbackyardsandin

croppingareas(Allison,2011).Producingproteincanreducetheadverseeffectsof

povertysuchasmalnutrition(Golden,Allison,Cheung&Dey,2016).

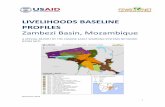

Figure1.1:MapofENBPandspecificareascoveredbystudy

14

1.4AimsandResearchQuestions

1.4.1Overallaim

Theoverallobjectiveofthestudyistoidentifyindividual’savailablecapitalsand

evaluatethesocialandeconomicpotentialoffishfarminginEastNewBritain

Province(ENBP),PNGusinganSLifAframework.Thisprojectaimstoinform

futureACIAR-fundedworkandNFAprogramstodetermineandsupportinland

fishfarmingopportunitiesandincreasethesocialandeconomicbenefits.

1.4.2Researchobjectives

Thespecificobjectivesandtheirunderpinningresearchquestionsareto:

1. Determineanddescribetheopportunitiesanddriversofsocial,human,natural,

physicalandfinancialcapitalsavailabletosustainablyfarmfishinENBP;

Whataretheopportunitiesforgrowthofthelocalindustrybasedonthesocial,

physical,naturalandfinancialcapitalsofthefarmersorpotentialfarmers?

2. Identifyanddescribethecurrentsocial,economicandenvironmentalbottlenecks

togrowthofinlandaquacultureinENBP;

Whataretheeconomic,socialandenvironmentalbottlenecksforgrowthofinland

aquacultureinENBP?

15

3. Evaluatethesocialandeconomicbenefitsofinlandfishfarmingdevelopmentin

ENBPandPNG;and

Whatarethesocialandeconomicbenefitsofinlandfishfarmingdevelopmentin

ENBPandhowdotheycomparetoexistinglanduse/livelihoods?

4. Makerecommendationsforchangestotheinstitutionalmanagementframework

foraquaculturedevelopmentinENBP

WhatinstitutionalarrangementsarerequiredtoenableNFAtofacilitategrowthof

theindustry?

1.5Approach

Thisisasocio-economicstudyusingamixed-methodsapproach,mainlyfocusing

onqualitativedesignandanalysisduetothesmallpopulationoffishfarmersin

ENBP.Arigorouslyquantitativeanalysiswasnotpossibleduetothestatistical

powerofasmallsamplesize.Thestudyconsistsofinterviews,surveydataand

basicstatisticalanalysis.ItfollowstheACIARmethodologyofaSLifA.

16

1.6SustainableLivelihoodAnalysisframework

Alivelihoodistheaccumulationofassets,activitiesandaccessthatistheliving

gainedbyanindividualorhousehold(Allison&Ellis,2001).Sustainable

livelihoodsanalysisframework(SLA)isapeople-centeredapproachthatimproves

knowledgeontherelationshipsaffectingandinfluencingpeople’slivelihoods,and

guidespolicyanddevelopment,particularlyforpoorandvulnerablecommunities

(Allison&Horemans,2006).Theframeworkfocusesonfourtypesof

sustainability:institutional,economic,socialandenvironmental.Thestudy’sSLA

frameworkfollowsthewidelyuseddefinitionoflivelihoodasdevisedbyChambers

andConway(1992)andisanintegralmethodologyforthisproject.

“Alivelihoodcomprisesthecapabilities,assets(stores,resources,claimsandaccess)

andactivitiesrequiredforameansofliving:alivelihoodissustainablewhichcan

copewithandrecoverfromstressandshocks,maintainorenhanceitscapabilities

andassets,andprovidesustainablelivelihoodopportunitiesforthenextgeneration;

andwhichcontributesnetbenefitstootherlivelihoodsatthelocalandgloballevels

andintheshortandlongterm”(Chambers&Conway,1992,i).

Sustainablelivelihoodsframeworkanddefinitionshavesinceevolvedandgrown

rapidly(Carney,1998;Ellis,2000;Scoones,1998).Theexpansionanduptakeof

thisanalyticalframeworkhasbeenappliedinawiderangeofissuesfrom

HIV/AIDS(Loevinsohn&Gillespie,2003),conservation(Cattermoul,Townsley,&

Campbell,2008),foodsecurity(Ellis&Freeman,2004)andpovertyreduction

(Carney,1999;Lloyd-Jones&Rakodi,2002).Itisalsousedbyorganisations(e.g.

17

FAO,WorldBank,DFID),NGOsandresearchinstitutes(e.g.ODI)asananalytical

evaluationoflivelihoodoraplanningtoolforfuturedevelopment.SLAis

implementedinmanyhouseholdstudiesbecauseitispeople-centeredandcan

makeslinksbetweenthecomplexfacetsofhouseholds(Chernietal.,2007;Ellis&

Biggs,2001;Scoones,2009).SLAaimstomakethecomplexityoflivelihoodsofthe

pooreasiertounderstandandguidedecisionmakingtoovercomedeficiencies

(Morse&McNamara,2013).Bebbington(1999)notesthatitcreatesmicro-and

macro-scalelinksbetweencommunitiesandtheirinfluencelocalinfluenceon

institutionalandpolicy.

TherearefiveintegralcomponentstoSLA:thevulnerabilitycontext;assetsand

capitalsofthehousehold;transformingstructuresandprocesses;livelihood

strategies,and,livelihoodoutcomes(Figure1.2).Morse&McNamara(2013)

contendthatpeople’sassetsaredestroyedorcreatedbythreeexternalfactors:

trends,shocksandseasonalitythatmakeupthevulnerabilitycontext(further

discussedinsection1.6.2).TherearefiveassetcapitalsclassifiedinaSLAwithin

thevulnerabilitycontext,whicharehuman,social,natural,physicalandfinancial

(Ellis,2000).Theseassetsareusuallydepictedinapentagram(Figure1.2).Eachof

thesecapitalscaninfluencetheothersbothdirectlyandindirectly.Socialcapital

interactswiththeothercapitalsandgivesrisetointeractionandrelationship

buildingatalocalandinstitutionallevel(Bebbington,1999).Bebbington(1999)

identifiedtheneedtounderstandthatpeople'scapitalsaresubjecttochangeover

timeandneedreadjustmentthroughouttheirlife.SLArecognisestheactivitiesand

actionspeopledotomakealivingandinvestigateslivelihoodfromalocallevelas

18

wellashowenvironmental(climatechange)andinstitutional/policycanimpact

people.

Figure1.2:SustainableLivelihoodsFramework(Carney,1999)

ThewideuseofSLAisnotwithoutcriticism.Theliteraturecritiquesthescopeand

complexitythattheSLAframeworkcovers(Carney,2003;Scoones,2009).

However,SLAshouldbebroadinordertocoverthecomplexityoflivelihoodas

thisistherealityofapeople-centeredanalysis.Carney(2003)wasconcernedthat

theframeworkdowngradesissuessuchasgovernance,institutionsandpower

whenSLAwasusedinpractice,anddidnotintegrate‘sustainability’fully,

especiallyenvironmentalsustainability(Ashley&Carney,1999).Thiscritiquealso

tiesintotheissueofSLAbeingtoobroadbutisdependentontheindividual

prioritiesofparticipantsandstaff(Ashley&Carney,1999).TheuseofSLAin

respecttolong-termshocksandstressesneedsmorefocus,particularlyrelatingto

environmentalchangeduetoanincreaseinclimaticvariabilityrelatingtoclimate

change(Scoones,2009).Thismeansmanycommunitieswillbemoresusceptible

19

toshocksandstressesbroughtaboutbyclimatechange,thereforeSLAcouldbe

implementedtoevaluatelivelihoodstrategiestohelphouseholdscope.Monitoring

long-termprogressisanotherkeydifficulty,withmuchoftheliteraturebeing

shorttermstudiesthatdonotmonitorchangesthatoccurinhouseholdlivelihoods

(Kranz,2001).

TheapplicationofSLAtotheaquacultureandfisheriesindustryhasgrownover

thelastdecade(Allison&Ellis,2001;Allison&Horemans,2006;Ahmed,2009;

Sari,2015).Allison&Ellis(2001)usedthisframeworkinthecontextofadapting

developingcountries’small-scalefisheriesmanagement,whichcanbeappliedto

thisproject’ssmallcommunityfishfarminginPNG.Theframeworkinthisproject

willbeusedtoanalyticallyprovideknowledgeonthecurrentandfutureneedsfor

developmentofinlandaquacultureinPNG.PNGprovidesaninterestingresearch

settingtoapplySLAbecauseofthetribalsociety,clanownershipofland,lowlevels

ofdevelopment,yetabundantnaturalresources.

1.6.1Introducinglifestyleintothesustainablelivelihoodsanalysis

ThisprojectwillutilizeavariantoftheSLAframeworkdesignedbytheUnited

Kingdom(UK)DepartmentofInternationalDevelopment(DFID)sinceithasa

strongemphasisonitsuseasaholisticdevelopmenttooltoimprovetolivelihoods

ofthepoor(StephenandMcNamara,2013).SustainableLifestyleAnalysis(SLifA),

whichwillbeusedinthisstudy,isbuiltuponthefivecomponentsoftheSLA

framework.Theassetpentagonvarieswiththecenterofthepentagram

representingzeroaccesstoresources(Figure1.2).Therefore,eachpointofthe

20

pentagramcanvarydependingonindividualhouseholds.Assetscanaffecteach

otherandtheaccesstovariousresources.Eachoftherelationshipsbetweenassets

isimportanttounderstandduetotheirrelationship.Livelihoodgoalsusually

supportpeople’slifestyleschoices,alsoconsideringspiritualandaspiration

aspects.Theinclusionoflifestyleencompassesotheraspectsofhumanlifesuchas

cultureandsocialstatus,whichimpactslivelihooddecisions(Morse&McNamara,

2013).ThisframeworkalignswiththeACIARproject’sapproachtofacilitate

comparisonandalsoaddresstheumbrellaobjectivesforinlandandcoastalareas

ofPNG.

1.6.2Vulnerabilitycontext

Thevulnerabilitycontextinvolvestheexternalenvironmentalfactorsthatpeople

havenocontrolover.People’slivelihoodsandassetstatusareaffectedbytrends

(population,resources),shocks(economic,natural)andseasonality(prices,

production).Ahouseholdisaffectedbybothinternalandexternalfactorsthat

affecttheavailabilityofassetsandoptionsforbeneficiallivelihoodoutcomes(Lax

&Krug,2013).Shockscaneliminateassetsdirectly,trendsareusuallylessharmful

andmorepredictable,andseasonalityisoneofthelong-termadversitiesthatface

thepoor(Cannon&Muller-Mahn,2010).Thoughnotalwaysnegative,the

vulnerabilitycontexthighlightsthefactorsthatpredominantlyimpactthepoor,

whichaffectstheirlivelihoodoptionsandabilitytochangetheirlivelihood

strategy.Tochangethevulnerabilitycontextinwhichthepoorlive,itisoftenupto

transformingstructuresandprocesses(e.g.reformingpolicy)(Carney,1999).

Helpingpeopletocopebetterwithshocksincreasestheirabilitytotakeadvantage

21

ofopportunitiestobuildtheirassets.WithoutsocialnetworkssuchastheWantok

system,thereisanincreaseinvulnerabilitytolivelihoodbreakdowns(Koczberski

&Curry,2005).Theidentificationofthefactorsthataffectacommunitywillenable

anunderstandingoftheimpactsandallowstrategiesforminimization.

1.7Assets,CapitalsandCapabilities

1.7.1Humancapital

Humancapitalisknowledge,healthandskillsthatallowhouseholdstofollow

differentlivelihoodstrategiesandachievelivelihoodoutcomes(Carney,2003).

Humancapitalisthelabourskillatahouseholdlevelandshowstheamountand

qualityoflabouravailable.AcapitalisconsideredthesameasanassetinthisSLA

framework,whilecapabilitiesarenotsimplyresourcesusedbutgiveindividuals

theabilitytoactandbe(Bebbington,1999).Humancapitalhasbeenfoundtohave

significantinfluenceonfactors,othercapitalsandeconomicgrowth(Hanushek,

2013).TheDepartmentofInternationalDevelopment(DFID)UKconsidersthis

capitalorassetessentialtogainingaccessandutilisingtheotherassets,whilenot

sufficientonitsown.Humancapitalimpactscanbeatahousehold,communityor

nationalscale.Thevaryingsizeofhouseholdsimpactstheirhumancapitalfrom

educationandskillstoageandgender,influencingthepursuedlivelihood

strategies(Morse&McNamaraetal.,2009).Indirectstructuresandprocesses,

suchasreformtopoliciesandchangetoculturalnorms,areequallyimportantto

complementindividualinvestment.Toachievepositivelivelihoodoutcomes,

22

individualsmustbewillingtoimprovetheirhumancapitalbyinvestingin

themselvesthroughtrainingandschools.InPNGthenetenrolmentratefor

primaryschoolis84.28%,whichmaybepartlyattributedtopooraccessibility

meaninglessprovisionbythegovernmentinhealthandeducationservices

(Gibson&Rozelle,2003).Thislackofprovisionofserviceimpactsrural

community’shumancapitalandlimitstheirlivelihoodstrategies.

1.7.2Socialcapital

Socialcapitalinvolvesthesocialresourcespeopledrawoninpursuitoftheir

livelihoodobjectivesthroughinteraction(Ellis,2000).Carney(1999)classifies

socialcapitalasanintrinsiccapitalthatprovidesabuffertothevulnerability

contextfactors(i.e.shockssuchasdeath)andhowpeoplecope.Itismadeupof

networks,culturalnorms,formalisedgroupsandrelationshipsofsocialsupport,

trustandreciprocity,forexampleasseenunderthewantoksystem(Sayer,

Campbell&Campbell,2004;Woolcock&Narayan,2000).Itsavailabilityis

dependentonthehouseholdmembersandtheirinteractionwithotherpeople,

directlyimpactingtheotherfourcapitals.Socialcapitaliscloselyrelatedto

transformingprocessesandstructures(Figure1.2)withtherelationshipbeing

two-way.Directsupportthroughimprovementofgroupssuchasleadershipand

extendingexternallinksoflocalgroupsfurtheraretwowayshouseholdscan

improvetheirsocialcapital(Carney,2003).Indirectly,thedevelopmentofgood

governanceandstrongorganisations,helpingtodevelopmethodsofinteraction

withcivilsociety,canprovideacohesivesocialenvironment.Whileitcanhelpto

23

preventeconomicfailures,throughsupportfromothers,itcanalsohelptoshift

perspectivesandattitudesofcommunities(deRenzio,2000).

1.7.3Financialcapital

Financialcapitalistypicallytheassetleastavailabletothepoorandisnotconfined

tosimpleeconomicsasitincludesnotonlyflowsbutalsoanyfinancialmeansthe

householdhas(e.g.income,savings,credit).Therearetwomaintypesoffinancial

capital:availablestocksandregularinflowsofmoney.Availablestocksareusually

savingsandcantakeonanumberofforms(e.g.cash,livestock).Regularinflowsof

moneyontheotherhandconsistofincomeandpensions.Theseinflowsshouldbe

reliable(notone-off).Accesstofinancialgoodsenablesthehouseholdtoachieve

livelihoodgoalsandpayforessentialgoodsandservicesvitaltotheirlivelihood

strategy(Krantz,2001).Itshouldbenotedthatfinancialcapitalcanbeconverted

toothercapitalandusedindirectfulfillmentoflivelihoodoutcomessuchasthe

purchasingforfoodtoincreasefoodstability(Carney,2003).AmajorityofthePNG

populationisclassifiedaslivinginpovertywithoutdisposableincome,andwith

someassetssharedbetweenfamilymembersandwantoks(WorldBank,2009).

1.7.4Physicalcapital

Physicalcapitalreferstotheinfrastructurethatchangesthephysicalenvironment,

neededbythepeopletobemoreproductive.Essentialinfrastructurefor

24

sustainablelivelihoodsistheaccessto,andaffordabilityof,cleanwater,transport,

shelterandcommunicationtechnology(Lax&Krug,2013).Infrastructureis

usuallyexpensiveduetoinitialcostsforbuildingandlong-termmaintenance.

Householdscanputgreaterimportanceoncertaininfrastructurethanothers.If

thereislittleaccesstotransport,householdscannotgettheirproduce(e.g.fish)to

marketwhichdetrimentallyaffectstheirproductivityandlivelihoodoutcomes.In

PNGaccesstoaffordableandreliabletransportisnotreadilyavailable,withan

overalllackofinfrastructureandharshlandscapeimpedingitsdevelopmentand

maintenance(Edmonds,Wiegand,Koomen,Pradhan&Andree,2018).

1.7.5Naturalcapital

Naturalcapitalisclassifiedbyawiderangeofnaturalresourcesand

environmentalservices(Kranz,2001).Itincludesintangiblegoodssuchas

biodiversityandtheatmosphere(Carney,2003).Itisalsorelatedtothe

vulnerabilityfactors,particularlyseasonality(e.g.seasonalclimate,weather,

marketseason)whereaccessandqualitycanchangesignificantly.Naturalcapital

providesasignificantcontributiontogoodsandservices.Therefore,long-term

trendsinuseandqualityareimportantandneedtobemonitoredtodetermine

livelihoodstrategiessuchasthroughconservationandimplementationofservices

(Costanza&Daly,2003).Environmentalsustainabilityisoneofthefour

sustainabilitytypesthatSLAfocuseson,inbalancewithmeetingpeople’sneeds.

Indirectchangestotheinstitutionsthatmanagenaturalresourcesandclear

environmentallegislationwillallowbetteraccessandmanagement(Carney,

2003).InSLA,naturalcapitalaimstounderstandhownaturalcapitalisusedand

25

valued.PNGisrichinnaturalcapitalwithhighbiodiversity,naturalresourcesand

landavailability(Barrowsetal.,2009).

1.8Structure

Thisthesisiscomprisedofsixintegralchapters.Inwhatfollows,Chapter2will

discussthehistoryandcurrentstateoftheAquacultureindustryinENBP.Chapter

3outlinesthemethodologyandanalysisconducted.Chapter4presentsaresults

anddiscussiontoevaluatethefirstandsecondresearchobjectives.Chapter5is

alsoaresultsanddiscussionansweringthethirdresearchobjective,referringto

Chapter4.RecommendationsaremadefromthisinChapter6.

26

ChapterII:HistoryandLegislationofAquaculturein

PapuaNewGuinea

2.1AquacultureinPNG

InmanyPacificIslandCountriesandTerritories(PICTs),theissuesandlimited

understandingofnutritionalongsidefoodimportsandavailabilityisprominent

(WHO,2010).Micronutrientdeficiency,higherprevalenceofnon-communicable

disease,anddiabetesarecommonhumanhealthissuesinPICTsduetoadeclinein

qualityfoodandsubsequentnutritionalsecurity(Hoy,Roth,Viney,Souares,&

Lopez,2014;WHO,2010).Thedrivetoincreasefishfarmingindeveloping

countriesstemsfromtheneedforasustainableandattainablesourceofprotein.

DietsinPICTshavetransitionedfromtraditionalfoodsconsistingoffreshfish,

meatandgreenvegetables,toamoderndietofimportedprocessedandrefined

foods(Charltonetal.,2016).Malnutrition,causedbydeficiencyinvarious

nutrientssuchasprotein,canleadtostuntedgrowthanddevelopmentaldelay

(WHO,2010).Awidelysuggestedsolutiontofoodsecurityistoencouragethe

farmingoflocally-producedhighproteinfoods,suchasfish,totakeadvantageof

thenaturalresourcesthatcansupporttheirproduction(Charltonetal.,2016;

FAO2008;Gabrieletal.,2007).

AquacultureinPapuaNewGuinea(PNG)isquicklyexpandingwithasignificant

increaseinfishfarmsinthepastdecade(Vira,2015).Thedemandforfishfarming

hasincreasedduetoitspotentialtoimprovehouseholdnutritionandfood

27

security;itisalsoconsideredmorepracticalforsmall-scalefarming,oftenfamily-

runventures,indevelopingcountries(Charltonetal.,2016).Thisisparticularly

relevanttoPNGbecause80%ofthepopulationlivesinruralinlandareas,away

fromcoastalresources(Nordhagen,Pascual&Drucker,2017).ThePNG

communities’fishconsumptionisundertherecommendedlevels,whichcanbe

attributedtoalackofaccessibilityandthehighcostoffish(Belletal.,2009;Vira,

2015).Currently,thePNGaquacultureindustryusessmall-scaleearthenpondsfor

subsistencelivingorinvolvessmallcommunitymarketsandpondswithoralong

vegetablegardensusinglowtechnologyapproaches(Vira,2015).

ThePNGfishfarmingindustryisdominatedbyGeneticallyImprovedFarmed

Tilapia(GIFT),followedbyCarp.ItwasinferredbySmith(2007)thataquaculture

contributed4%tosmall-scalefarmer’sincome,whichisexpectedtobemuch

highernow,givenitsgrowthinthepastdecade.Otherfreshwaterspeciessuchas

rainbowtroutandbarramundihavealsobeenfarmed;thereareonlythreetrout

farmsandbarramundifarmingrecentlyceasedduetoalackoffingerling

production.Vira(2015)SWOTanalysisrecognizedthatkeyconstraintstofarming

troutandbarramundiincludedthelackofequipmentandmaterials,knowledgeon

accessingcreated,andthelimitedcontacttowatersupply.Furthermore,feedand

husbandryskillswerelimitingfactorsforfarmingcarpandtilapia.Thecurrent

scopeofthefishfarmingindustryishighlyconcentratedinthehighlandsofPNG–

thoughtheACIARprojectcoveredManus,Madang,WesternHighlandsProvince

(WHP),EasternHighlandsProvince(EHP)andMorobe–whichshowsitisgaining

momentum.

28

Thischapterwillcriticallydiscusspreviousandcurrentworkinthedevelopment

ofsmall-scaleinlandfishfarminginPNG.Thechapterincludesahistorical

overviewoftheindustryandexaminesexistingpolicyandregulationsrelatedto

aquacultureinPNG.AcomparisonofresearchbetweenAsiaandotherpacific

countriesisalsoincludedtoplacethePNGaquacultureindustryinawiderAsia-

Pacificcontext.Inthischapter,publishedandunpublisheddocumentsare

analysed,thelatterbeingmainlygovernmentordonor-agencyreportstofill

knowledgegapsinthescantpublishedliteratureonaquacultureinPNG.

2.2HistoryofAquacultureinPNG

PNGhasintroducedandtrialledmanydifferentspeciessincetheintroductionof

aquacultureover50yearsago.FishfarminginPNGwasanearlyrecommendation

stemmingfromoffoodsecurityandnutrientdeficiency.Theintroductionoffish

farmingwasalsoattributedtohavingapredominantlyinlandpopulationandled

totheimportationof21speciesfrom1930-1974(Glucksmanetal.,1976).Dueto

thelimitedknowledgeoffishhusbandry,andrecurrentfailurefarmingnative

species,theintroductionofexoticspecieswasneeded(Smith,2013).Thissection

willfocusonthehistoryofinstitutionsinvolvedinfreshwateraquaculture.

Additionally,thischapterdiscussesfreshwaterfishfarmingspeciespreferencein

PNG,theirprevalenceandthesurvivalofspecies.

29

Earlyhistory1930s-1960s

Mosquitofish(Gambusiaaffins)wasthefirstknownintroduction,around1930,

intendedtocontrolthemosquitopopulationandhelpreduceprevalenceof

malaria(Glucksmanetal.,1976).Inthelate1940s,browntrout(Salmotrutta)was

introducedforstockingintheHighlandsofPNGforfoodandsportsfishing

(Glucksmanetal.,1976).Thisspeciesneverachieveditspotentialasafishfarming

speciesandisnowuncommoninPNG(Glucksmaetal.,1976).Rainbowtrout

(Oncorhynchusmykiss)wasintroducedin1952andshowedmorepotentialforfish

farmingthanbrowntroutforfoodandsportsfishing(Blichfeldt,1974).

Oncorhynchusmykississtillfarmedandoccursinthewild,butwithascattered

populationbecauseitissuitedtothecooler,higheraltitudeconditionsinthe

HighlandsofPNG(Verhille,English,Cocherell,Farrell&Fangue,2016).Onlythree

farmscurrentlyproducethisspeciesinPNG,andrecurrentfailureiscommon.

In1954,theHighlandsAgricultureExperimentalStation(Aiyura)wasdeveloped

bytheDepartmentofAgriculture,StockandFisheries(DASF)tosupportthe

productionoffreshwaterfishinPNG.Thisdepartmentprecededtheestablishment

ofNFA.TheaimsofthisinstitutionweretocreateaproteinsourceforPNGs

malnourishedpopulationandgeneratecashincomeforsmallholderfarmsata

small-scaleandcommerciallevel.Throughout1954-1957afewotherspecieswere

alsointroducedforhumanconsumption(Table2.1).Mozambiquemouthbrooder

(Oreochromismossambicus)isstillrelativelywidespreadandusedforfood,but

mainlyinthelowlands.Atitsintroductionitwasconsideredafailureforfish

farmingduetoslowgrowthrates.However,itbecameestablishedintheSepik

30

Riverduetofavourableenvironmentalfactors(Coates,1987)andisnowpartofa

capturefishery.

Thecommoncarp(Cyprinuscarpio)wasimportedtoreplaceOreochromis

mossambicusforaquaculturein1959,withthegovernmentplayingarolein

distributingthespecies(Glucksmanetal.,1976).Thecommoncarpwasandstillis

oneofthemostsuccessfullyfarmedfishinPNGwithawidespreaddistributionfor

bothcommercialandsmall-scalefarms(Smith,2007;Vira,2015).Itwasreported

thatsweetpotatoandricebranwereusedasfeedforcommoncarp(Cyprinus

carpio)(Wani,2004).Atthistime,mostfarmerswereusingpelletisedfeedsmade

forchickensandotherlivestock,withAiyurapromotingthefertilizationofponds

tostimulatenaturefoodproduction(La’a&Glucksman,1972).TheFAO,in

conjunctionwiththeDepartmentofFisheriesandMarineResources(DFMR),

introducedmanyofthefarmingspeciesandattractedcommunityinterest(Table

2.1).Throughoutthe1960s-70s,DASFstockedmanyfishspeciesforfoodandpond

culture.Otherintroductionsweremadeforarangeofpurposessuchasfood,sport

andaquariumsduringthistimebutfoundnosuccess.Thiswasattributedto

environmentalfactors,mortalityorescapingtheirenclosure(Table2.1)

(Glucksmanetal.,1976).

1970s-1990s

Inthe1970s,therewaspotentialforfishfarmingbutadeclineininterestdueto

thelackofpoliticalsupport,technicalknowledgeandfishhusbandryskills(Kan,

31

1981).Alackoftraditionalfishhusbandrymeantthatfarmedfishshowedslow

growthrates;fishfarmingwasnotwidelypracticed(Glucksmanetal.,1976)thus

husbandryskillswerenoteasilylearnedorshared.In1970,Kotunitroutfarmin

Gorokawasthefirstfarmtotryandproducefarmtrout,specificallyrainbowtrout

(Oncorhynchusmykiss)(Coates,1987).In1973,rainbowtrout(Oncorhynchus

mykiss)wassuccessfullycommerciallyfarmedatKotuni.However,in1984Kotuni

commercialtroutfarmingclosedduetocommunityandmanagementissues,with

somecommunityattemptsatrevivingtheactivitysinceitsclosure(Adams,Bell&

Labrosse,2001;JoeAlois,personalcommunication,12Dec2017).Farmingof

rainbowtrouthasoccurredsparselythroughoutthehighlandsduetotherequired

coolerweatherconditions(Smith,2007).Rainbowtroutoptimumtemperatures

arebelow21˚Cwhiletospawnandgroware2˚to12˚C(Fornshell,2002).Small-

scalefarmersreliedonafewlocalfarmsorcatchingwildtroutforfingerling

supplies(Pitt,1986;Vira,2015),whilstsomeimportedeggsbutexperienced

lossesduetofungalinfectionsintheeggstock.Rainbowtroutisdifficulttofarm

successfullybecauseofdependencyonahighproteincontentinthefeedandthe

needforasupplyofconstantandwelloxygenated,fast-flowingwater(Hair,Wani,

Minimulu&Solato,2006).In1985Aiyuraalsoceasedtroutfingerlingproduction

duetoslowgrowthratesandlackofinterestwithinthecommunity(Pitt,1986).

In1987,LakePindiYaundoTroutFarm(LPYTF)commencedproduction,

producing10tonnesperannumforthedomesticfishmarket(Hairetal.,2006).A

Goroka-basedfarm,NupahaTroutfarm,alsocameintooperationin1990(Povlsen,

1993).Acollaborationbetween1987and1993withthePNGgovernmentand

32

FAO/UnitedNationsformedtheSepikRiverStockEnhancementProject(SRSEP

projectnumberPNG/85/001)whichintroducedanumberoffishspeciesto

increasefreshwaterfishproductionforSepikcommunities.Bigheadcarp

(Aristichthysnobilis)andRedbresttilapia(Coptodonrendalli)wereboth

introducedtooccupynichesnotfilledbynativefishandtoprovidefreshwater

foodsourcesforcommunities(Dudgeon&Smith,2006).Bigheadcarpappearsto

havediedout(Smith,2007).FisheriesImprovementbyStockingatHighAltitudes

forInlandDevelopment(FISHAIDprojectnumberPNG/93/007)1993-1996

followedwhereSRSEPleftoffandintroducednumerousspecies(refertoTable

2.1).

TheJapaneseInternationalCooperationAgency(JICA)wasanearlyinternational

donorthatsignificantlyhelpedtoestablishinlandaquacultureasasourceof

incomeandfoodsecurity.UndertheinfluenceofJICAtheaquacultureindustryhad

significantgrowthinthe1990swiththeexpansionofpondsandhatchery

infrastructure(Smith,2007).JICAhadanearlycollaborationwithDFMR,now

NationalFisheriesAuthority(NFA),beforedelegatingtheroleofaquaculture

developmenttotheEasternHighlandsProvincialgovernmentin1998(Smith,

2013).JICAthenwentontoimprovetheHighlandsAgricultureExperimental

StationatAiyura,nowrenamed,theHighlandsAquacultureDevelopmentCentre

(HAQDEC).HAQDEChadtheaimofincreasingfingerlingproductionandtechnical

skillsofofficersandfarmers.Theyweresuccessfulinincreasingfingerling

distributionofcarpandtroutbyimprovingfishhusbandryskillsandproviding

extensiontrainingprograms(Mufuape,Simon&Chiaka,2000).

33

1999-2008

GeneticallyImprovedFarmedTilapia(GIFT)(Oreochromisniloticus)was

introducedbyJICAin1999andfurthersolidifiedaquaculture’splaceinPNGdueto

itssuccess(Smith,2013).FingerlingdistributionofGIFTcommencedinlate2002

fromHAQDECinMorobeandEasternandWesternHighlandsProvinces(Smith,

2007).GIFTisnowrecognisedasoneofthepreferredfarmingspecies,duetoits

fastbreedingandreducedneedforexpensivehatcherieswithsmall-scalefarmers

supplyingtheirownfingerlings(Gupta&Acosta,2004;Smith,2007).HAQDECat

Aiyuraproducedfingerlingsforcommoncarp(Cyprinuscarpio),GIFT(Oreochromis

niloticus)andJavacarp(Puntiusgonionotus),distributingthemthroughoutthe

country.Anyspeciesthatlowersthecostsoffishfarmingbenefitstheownerin

termsofincomeandruraldevelopmentinthecommunity(Vira,2015).An

investigationbyJICAandHAQDECspecifictocarpexaminedthecompositionof

dietsatYonkiReservoir(Smith,2007).Localfarmersalsoexperimentedwith

chickenmanureandcoffeewastewithlimitedsuccessexemplifiedbystunted

growth(Smith&Kia,2000).Fishfarmingbecameamainstreammethodfor

obtainingfoodsecurityinPNG(Smith,2013).

SincetheJICAprojectendedin2000,theNFAandthefederalgovernmentinPNG

havehighlightedtheneedforaquaculturedevelopmenttocombatfoodsecurity

issues(Wani,2004;Vira,2015).TheAustralianCentreforInternational

AgriculturalResearch(ACIAR)hasalsobeenamajorcontributorandcollaborator

since2001,particularlyinongoingfreshwaterinlandaquacultureprojects.ACIAR

hasenabledaquacultureresearch,capacitybuildingofscientistsandfarmers,and

increasedfishhusbandryknowledgethroughcollaborationwithNFA.Additionally,

34

byfundingresearchbyAustralianagenciestoestablishfoodsecurityinPNG.In

2001-2004anACIARprojectassessedtheindustryandevaluatedsmallholder

researchanddevelopmentneeds(ProjectnumberFIS/2001/034).Thestudy’s

initialestimatednumberoffamerswasalmostdoubledduringthesurveyand

providedimportantdatarelatingtotypesoffarmersandthefeedlocalsused

(ACIAR,2004).Theprojectlaidthefoundationfordeterminingtheextentoffish

farminginPNGthroughsurvey.Followingthisproject,anotherstudyfrom2005-

2008evaluatedimprovingfingerlingsupplyandnutritionforsmallholderfarms

(FIS/2001/083).Thisprojectcametofruitionafterthepreviousprojectfoundthe

lackoffingerlingsupplyandfeedwerekeyconstraints.Theresearchwascarried

outatHAQDECatAiyuraandtheUniversityofWesternSydney,withaworkshop

onhatcheryoperationsprovidingvitalinformation.Thissubsequentlyincreased

theefficiencyandknowledgeforhatcheryandbroodstockmanagementthatwere

applicablefortheagriculturalconditionsinPNG(ACIAR,2008).Theoutcomesof

thisprojectimprovedsmall-scalefarmersaccessibilitytofishhusbandry

knowledgeandfingerlingsupply.However,theprojectultimatelyendedbeforethe

benefitscouldbeaccuratelyquantified(ACIAR,2008).

35

Table2.1:ListofintroducedspeciestoPNGfrom1930’s-2000(adaptedfromGlucksmanetal.,1976)

Species Date

introduced

DistrictIntroduced Use Status

Mosquitofish(Gambusiaaffins) 1930 Widespread Malariacontrol Widespreadbutholdslittlevalue.Didnotcontrol

mosquitosasoriginallyintroducedfor.

Browntrout(Salmotrutta) 1949 SHD,WHD,ChD,EHD Food-sport Uncommoninthewild.Hadsomepotentialin

aquacultureandasafoodsource

Rainbowtrout(Salmogairdneri

renamedOncorhynchusmykiss)

1952 SHD,WHD,ChD,EHD,

MD

Food-sport Commonalthoughscattered.Hadbetterpotential

thanS.trutta

Mozambiquemouthbrooder(Tilapia

mossambicrenamedOreochromis

mossambicus)

1954 Widespread Food-pondculture DASF.Widespread.

Giantgoramy(Osphroneumusgoramy) 1957 WSD,ESD,WHD,MD,

MaD,WD,ENBD,CD

Food DASF.Small,scatteredpopulations

Snakeskingoramy(Trichogasteror

Trichopoduspectoralis)