A Comparison of College Football and Auto Racing Consumer Profiles: Identity Formation and...

Transcript of A Comparison of College Football and Auto Racing Consumer Profiles: Identity Formation and...

???Sport Marketing Quarterly, 2015, 24, xx-xx, © 2015 West Virginia University

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 43

Introduction

Knowledge of antecedents and outcomes of identifica-tion with teams or athletes, alongside motivations forspectatorship, allow organizations to adopt models ofsport consumption that best meet tactical purposes(Stewart, Smith, & Nicholson, 2003). This strategypotentially increases sport consumption (Sutton,McDonald, Milne, & Cimperman, 1997) in partbecause understanding disparities in market segmentsis crucial to isolating consumers’ needs, identifyingtheir foundations of loyalty and commitment, andexposing spending patterns (Pitts & Stotlar, 1996;Shilbury, Quick, & Westerbeek, 1998). Strategicallytargeting social or collective identities has been pur-ported to link to managerial outcomes such asdecreased price sensitivity and performance-outcomesensitivity, making it easier to sell tickets at higherprices even in cases when teams do not perform well(Sutton et al., 1997). To achieve these ends, organiza-

tions must have the ability to identify psychological,cognitive, and behavioral mechanisms that drive iden-tity processes and motivations for sport consumption.Comprehending these arrangements is especiallypoignant when considering that sources of identifica-tion and sport consumption may differ by sport type(James & Ross, 2004). Essentially, sport consumers“display a bewildering array of values, attitudes, andbehaviors” (Stewart et al., 2003, p. 206); thus, it isvaluable to classify and explicate disparities betweendifferent types of sport so organizations can target eachaccordingly.This investigation is a comparison of different con-

sumer groups in relation to antecedents of sport con-sumers’ identification and motives. Authors of thisstudy consider the range of literature in sport/socialpsychology as well as sport management and market-ing to better understand variations in identity forma-tion and spectator motivations between college football

A Comparison of College Football andNASCAR Consumer Profiles: IdentityFormation and SpectatorshipMotivation

Shaughan A. Keaton, Nicholas M. Watanabe, and Christopher C. Gearhart

Shaughan A. Keaton, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Young Harris College.His research interests include sport communication, identity formation, intergenerational communication, and listening.Nicholas M. Watanabe, PhD, is an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism’s sportmanagement emphasis at the University of Missouri. His research interests include sport economics and sport management.Christopher C. Gearhart, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Tarleton StateUniversity. His research interests include sport and communication, including fantasy football and studies of team identifi-cation.

Abstract

This research is a comparison of identification and motivation factors between sports with team as a pointof attachment (college football) and sports with an individual athlete as a point of attachment (NASCAR).The results contribute to advancing our understanding of identity formation and spectator motivation.Geography and family were found to be important antecedents of college football team identification, whilemedia influence drove consumer identification with NASCAR drivers. NASCAR sport consumers wereprone to watch their sport casually, while college football sport consumers were influenced to watch theirsport by the aesthetics of the game, and a relationship to other recreational activities such as tailgating.Findings help us to understand what specific factors play a role in individuals connecting with different typesof sport symbols, but also have implications for the management, marketing, communications, and sellingof sport and sport-related products.

and auto-racing sport consumers. Essentially, we queryto what extent different points of attachment (teamversus single athlete) vary in regard to identityantecedents and consumer motivations.

Sport Type Differences

In many cases, consumer-based research has includedexaminations of fandom in different manners, whetherby personal commitment and emotional involvement,a single factor inquiring into a sport consumer’s self-reported level of support for the team (Kwon & Trail,2001), self-concept, social and cultural identity affir-mation (Stewart et al., 2003), or obliquely referencedwith regards to game attendance (and the influence offriends and family), merchandise and media consump-tion, and loyalty (Fink, Trail, & Anderson, 2002).However, when considering these aspects, it is alsoimportant to note there are a number of attachmentpoints for a sport consumer, such as a team, player,coach, society, type, and level (Trail, Robinson, Dick,& Gillentine, 2003). This study is framed throughcomparison of sport consumers who identify by way ofa team as a point of attachment as opposed to sportconsumers who identify with an individual athlete as apoint of attachment. Researchers investigating differences among sport

consumers from each of these points of attachmentoffer contradictory findings. For instance, James andRoss (2004) examined consumer behaviors acrossbaseball, softball, and wrestling, and found differences

in age, education, employment, income, and familycharacteristics between audiences of different sports.Specifically, those attending wrestling matches (with aplayer as a point of attachment) were more interestedin athletic performance and drama, while baseballsport consumers (with team as a point of attachment)scored lowest on these dimensions. This observationsuggests that sport consumers with different points ofattachment display diverse motivations for attendanceand consumption. Wenner and Gantz (1989), in contrast, have found

that spectatorship motivations are similar for thoseconsumers who have different attachment points. Forinstance, several general motivations to watch a teamsport—such as college football (CFB)—are similar tothose for sports like tennis (where consumers identifywith a player as a point of attachment), includingbeing a fan in general, leisure time, and social compan-ionship. These authors have attempted to explicate this dis-

crepancy between previous studies by comparing twodifferent consumer group profiles in regard to identifi-cation and spectatorship motivation: Those who iden-tify with a team as an attachment point to those whoidentify with a single athlete as an attachment point.CFB was chosen as an operational example of a sportthrough which consumers have teams as their point ofattachment. For a sport in which consumers have asingle athlete as an attachment point, authors chose theNational Association for Stock Car Auto Racing

44 Volume 23 • Number 4 • 2014 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

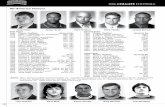

Table 1List of Hypotheses and Support

Hypothesis Prediction SupportH1 No group differences exist between CFB and NASCAR sport consumers Not supported

with regard to self-reported importance of viewing sporting events with family members

H2 CFB sport consumers self-report greater importance for geographic Supportedproximity during identity formation than NASCAR sport consumers.

H3 NASCAR sport consumers self-report greater influence from media Supportedcoverage during identity formation than college football sport consumers.

H4 No group differences exist between CFB and NASCAR sport consumers Mixedwith regard to self-reported importance of entertainment motives.

H5 College football sport consumers self-report greater importance for Not supportedathletic success and performance than sport consumers identifying with a NASCAR driver.

H6 NASCAR sport consumers self-report greater importance for aesthetic Not supportedmotivations than CFB sport consumers.

(NASCAR). College football and auto racing rank asthe third and fourth favorite sports by Americans, withauto racing the highest ranked sport through whichconsumers have a single athlete as a point of attach-ment (Corso, 2013). Following is an overview thatincludes a discussion of three identification factorsfrom sport psychology literature and three predomi-nant consumption/spectatorship motives. Authors alsowish to recognize there may be overlap between identi-ty and motivation factors. Hypotheses/research ques-tions that guide the research are proffered in thissection (a complete list of hypotheses can be viewed inTable 1).

Identification Processes of Sport Consumers

Sport team identification (STI) is “the extent to whicha fan feels a psychological connection to a team andthe team’s performances are viewed as self-relevant”(Wann, 2006, p. 332). Consumer identification is acomplex yet important concept studied in a variety ofdomains, including sport consumer behavior litera-ture, which touches upon the concept of team identifi-cation and its role in consumer behavior. For instance,Heere and James (2007) address the importance ofpsychological constructs in studying and understand-ing sport consumption behaviors through their devel-opment of a multi-dimensional team identificationscale. Conclusions reached by Heere and James werelargely derived from literature regarding team identifi-cation from other domains such as social psychologyand group identity research. It is from these variousperspectives that these authors consider factors of teamidentity formation alongside those for identity forma-tion with individual athletes.Identity formation factors are largely consistent in

sport research (Keaton & Gearhart, 2013; Wann,2006), including but not limited to commonantecedents such as family socialization, geography,and media influence (Jones, 1997; Keaton & Gearhart,2013; Wann, Tucker, & Schrader, 1996). These factorsare integral when selecting a favorite team, yet we donot know the extent that they might differentiallyinfluence a sport consumer to identify with a singleathlete (such as a NASCAR sport consumer identifyingwith a driver).

Family SocializationRegardless of sport, consumers having individual ath-letes and teams as points of attachment both reportthat viewership is partially a function of their socialrelationships (Spinda, 2011). Watching races or gameswith others facilitates social interaction and serves asan opportunity for family members to spend timetogether. Spinda, Earnheardt, and Hugenberg (2009)

note in detail the importance among NASCAR sportconsumers of viewing races with family members.Specifically, they found that a majority of respondentsidentifying as NASCAR fans report having familymembers who were also fans (62%), indicating thatfamily as socializing agents was influential in sportconsumer identification. James (2001) has found thatchildren as young as five were capable of forming apsychological commitment to a team, and that fatherswere the strongest influential factor during this identityformation process. The role of family has also beenreported as influential in team identity formation inregard to CFB in particular (Keaton & Gearhart, 2013).It is not a stretch, especially when considering socio-psychological research and the role of modeling inchildhood development, to consider the notion thatchildren often become socialized to support the sameNASCAR drivers or CFB teams that their parents do.For this reason, we predict:

H1:No group differences exist between CFB andNASCAR sport consumers with regard to self-reported importance of viewing sporting eventswith family members.

GeographyThe need for belonging is an important factor inexplaining team identification (Wann, 2006), and indi-cations within existing research are that the opportuni-ty for affiliation with others (and venues throughwhich to act out these affiliations) is one of the top fivereasons for identifying with a favorite team (Wann etal., 1996). Indeed, Sutton et al. (1997) claim, “commu-nity affiliation is the most significant correlate of fanidentification” (p. 18), and they offer that ties betweena local team and its community provide the “strongestlong term effects” (p. 19) on identification. Researcherspoint to the importance of community, more particu-larly the role of geography, in a sport consumer’s selec-tion of a favorite team (see Wann, 2006, for a review),with respondents in one study citing proximity as atop-five reason for starting to, continuing to, or ceas-ing to following a team (Wann et al., 1996). Jones(1997) investigated factors indicative of team identifi-cation with English soccer clubs and found that localityto the team was the most important factor. To thesepoints, many CFB sport consumers share some geo-graphic proximity with their identified team (Keaton &Gearhart, 2013), either by growing up near a campuswith a team, currently living nearby it, and/or attend-ing the school, although not all proximal sport con-sumers necessarily identify with the team. By contrast, scholars suggest geography may not

influence identification with NASCAR due to theabsence of a prominently featured “home field” for

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 45

46 Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

drivers and their hometowns. Rather, for NASCARsport consumers connections to local geographic com-munities are replaced by loyalty to sponsors and prod-ucts (Levin, Beasley, & Gamble, 2004; Levin, Beasley, &Gilson, 2008), whereby driver uniforms signal atten-tion to entities like beer brands and car manufacturersrather than cities such as New York and Los Angeles.Stated simply, “NASCAR fans pick drivers regardless ofgeography” (Hugenberg & Hugenberg, 2008, p. 639).Hugenberg and Hugenberg reference popular and suc-cessful NASCAR driver Jeff Gordon, a four-time cham-pionship winner, stating that his fans come from allover the US, “not just from near his childhood homein Indiana or his current residence in Florida” (p. 639).Whereas the fierce loyalty of CFB sport consumersoften emanates from geographic proximity (Keaton &Gearhart, 2013), for NASCAR sport consumers it isreplaced by a brand devotion to their favorite driver’ssponsors. Thus:

H2:CFB sport consumers self-report greaterimportance for geographic proximity during iden-tity formation than NASCAR sport consumers.

Media Influence By and large, CFB is restricted to a smaller geographicarea in which teams belong to regional conferences(i.e., Southeastern Conference, Pacific 12 Conference),thereby allowing sport consumers greater access tolocal information about their favorite teams. On theother hand, NASCAR sport consumers often travellarge distances to watch races that are spread across theUS. To follow favorite drivers, sport consumers mustrely upon national media for information because thelack of hometown coverage of individual drivers. Forsport consumers that are unable to travel such dis-tances or for traveling sport consumers who want tokeep up to date with favorite drivers, national mediaare vital to their consumption of the sport (Hugenberg& Hugenberg, 2008). To wit, the former SPEED net-work and current MAV TV network cable channels areexclusively dedicated to coverage of automotive sportssuch as NASCAR. In no place is the relationshipbetween national media and NASCAR more evidentthan in television advertising. NASCAR sport con-sumers are exposed to drivers outside of traditionalsport media via commercials and advertisements, andthese sponsors and partnerships provide opportunitiesfor identification apart from actual racing (Levin et al.,2004). Two of the most popular drivers in NASCAR—Dale Earnhardt, Jr., and Danica Patrick—are notamong the most successful in winning races but theyare easily recognized for their numerous endorse-ments, television commercials, and print advertise-ments. Earnhardt, Jr., for instance, appears in

television commercials for Mountain Dew, AmpEnergy drink, Taxslayer.com, Wrangler Jeans, andNationwide Insurance, to name a few; given this expo-sure, it is evident why he was voted the most populardriver in NASCAR for the 11 years prior to 2008(Hugenberg & Hugenberg, 2008). His popularity withsponsors and within media drives his reputation as apopular favorite driver. Accordingly:

H3:NASCAR sport consumers self-reportgreater influence from media coverage duringidentity formation than college football sport con-sumers.

Spectatorship Motivations of SportConsumers

Sport consumption and spectatorship motivations arerelated to factors of identity formation (as there is arelationship between why one watches a team and whyone identifies with a team), and have been categorizedby a number of scholars, ranging from leisure to aes-thetic appreciation (e.g., Scale of Sport SpectatorshipMotives [Keaton, 2013; Keaton & Gearhart, 2014];Sport Interest Inventory [Funk, Mahony, & Ridinger,2002]; Sport Fan Motivation Scale [Wann, 1995]). Acomparison of spectatorship motivations of NASCARand CFB sport consumers focuses on entertainment,achievement, and aesthetics.

Entertainment In a study concerning spectator motivations ofNASCAR sport consumers, Spinda (2012) indicatedthat a factor termed eustress/entertainment (i.e., enjoy-ing the stimulation, arousal, and drama associated witha race) accounted for the largest amount of variance(36.8%) in spectatorship motives by a wide margin.This finding is consistent with research among othersports, including CFB, which suggests that entertain-ment (i.e., seeking excitement, stimulation, socializa-tion, or just to occupy free time) has been a primaryviewership motive (e.g., Gantz, 1981; Wann, 1995;Wann, Schrader, & Wilson, 1999; Wann & Waddill,2003). Essentially, because sport viewing is entertainingfor sport consumers regardless of the sport type orpoint of attachment, it is expected that these entertain-ment motives will be similarly important for sportconsumers of CFB and NASCAR:

H4:No group differences exist between CFB andNASCAR sport consumers with regard to self-reported importance of entertainment motives.

AchievementAthletic performance is a team identity formationantecedent dealing with spectatorship motivation. It isalso an important factor of consumer motivation for

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 47

NASCAR viewership, as these consumers can experi-ence a personal sense of achievement from watching adriver who performs well (Spinda, 2012). NASCARsport consumers experience successes and failures oftheir favorite drivers through “basking-in-reflected-glory” and “cutting-off-reflected-failures” (Cialdini etal., 1976; Spinda, 2011). However, other characteristicsseem to be more important in motivating NASCARsport consumers to consume the sport: Researcherssuggest that a perceived homophily between the com-munity of racing sport consumers and their favoritedriver(s) is more significant, a feeling based upon char-acteristics such as demographic similarity and a per-ception of shared patriotic values (Hugenberg &Hugenberg, 2008) rather than the successes of the driv-ers. On the other hand, feelings of personal successhave been associated more closely with CFB sport con-sumers. McDonald et al. (2002), in a cross-sport com-parison of spectatorship motivation, show thatachievement spectatorship motivations are higher forCFB sport consumers (M = 15.8) than auto racingsport consumers (M = 14.2) (Table 5, p. 108).Therefore, we assert:

H5: College football sport consumersself-report greater importance for athletic successand performance than sport consumers identifyingwith a NASCAR driver.

AestheticsThe aestheic motivation for spectatorship reflects sportconsumer involvement due to the artistry of the sportor team that they follow (e.g.,Wann et al., 1999). Whenindividuals see sport as containing beauty, grace, or asrequring a high level of skill, they are more likely tobecome active spectators as they can appreciate theperformance apart from winning. As Smith (1989)writes, “even ordinary plays or actions may evoke anaesthetic response. The tight spiral of a football, a crispbody check, or a well timed feint, may exude a simpleelegance which forges a bond between the player andthe audience” (p. 59). Consumers of sports with individual athletes as

points of attachment have been linked to higher levelsof aesthetic motivation (Wann et al., 1999). ForNASCAR sport consumers specifically, motivation towatch races can emanate from appreciation of physicalrisks associated with racing at speeds over 200 mphand the accompanying expert driving skills required(McDonald et al., 2002). Moreover, other non-com-petive aesthetic qualities of NASCAR racing such aspreviously mentioned patriotic values and religiouspageantry, in conjunction with perceived homophilybetween drivers and sport consumers (Hugenberg &Hugenberg, 2008), make aesthetic motivations one of

six primary motivations for NASCAR spectatorship(Spinda, 2011). Conversely, McDonald et al. (2002)have reported low aesthetic motivation for consumersof football, and Wann et al. (2008) note that aestheticmotivation was found to be greater in sports with indi-vidual athletes as points of attachment (such asNASCAR) than sports with team as a point of attach-ment (such as CFB); although, when comparing themeans of auto racing (3.06) and college football (2.95)directly, there was not a statistically meaningful differ-ence. Recognizing that previous researchers have, how-ever, reported differences across the two sports, wepropose that:

H6:NASCAR sport consumers self-reportgreater importance for aesthetic motivations thanCFB sport consumers.

Methods

ProceduresStudents were recruited for the study via an onlinescheduling system. Those choosing this study as anoption from a list of departmental projects earned1.5% of their course grade for participating. All datacollected were confidential, all students providedinformed consent, and the appropriate InstitutionalReview Board approved all procedures. Participantswere directed to an external and secure universalresource locator (URL) where they chose to completeself-report scales measuring potential causes for identi-ty formation and spectatorship motives for either teamsport consumption (National Collegiate AthleticAssociation [NCAA] football) or racing sport con-sumption (NASCAR). The researchers made an explic-it effort to recruit those who self-described as fans ofone of the two sports. The participants were instructedto keep either their favorite NASCAR driver or colle-giate football team in mind as they were responding tothe corresponding set of scale items. This between-sub-jects design enabled comparison of two groups freelyidentifying as fans of either sport. Participants onlycompleted a set of surveys for one sport.

ParticipantsA total of 546 (280 females, 263 males, 3 not indicated;193 NASCAR sport consumers, 353 college footballsport consumers) undergraduate and graduate stu-dents attending Louisiana State University andAgricultural & Mechanical College constituted theconvenience sample for this study. Students rangedfrom 18 to 39 years of age (M = 20.20, SD = 2.39) andrepresented the freshman (n = 194), sophomore (n =153), junior (n = 98), and senior (n = 91) ranks; tworespondents indicated graduate student status, two

48 Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

indicated “other,” and six did not indicate class.Although recruited through communication studiescourses, only 82 self-identified as department majorsor minors. The participants self-described as white orCaucasian (78.9%), black or African-American(12.3%), Asian-American or of Asian descent (1.3%),Asian Indian (0.4%), Native American (0.7%), MiddleEastern (0.4%), Hispanic or Latino (3.1%), or Other(2.9%).

Preliminary AnalysesPrior to running primary analyses, data were inspectedfor violations of multivariate assumptions (Tabachnick& Fidell, 2007). All measurement scales were assessedfor dimensionality and ability to represent currentdata. Commonly used fit indexes and comparisonthresholds were utilized: The comparative fit index(CFI) above .90 and the root mean square error ofapproximation (RMSEA) below .08 (e.g., Byrne, 2010;Kline, 2005; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2006). Internalconsistency was estimated using Cronbach’s �. A posthoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power soft-ware (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). With N= 546 and alpha set at .05, power to detect smallPearson correlation effects (r = .10) was .76 andexceeded .99 for medium (r = .30) and large (r = .50)effects (see, Cohen, 1988).

MeasuresThe following self-report measures were chosenbecause they have been shown to exhibit consistentand satisfactory psychometric properties. These partic-ular scales were developed after a comprehensive andrigorous analysis of the most frequently used scales insport consumer and sport psychology literature andcontain original items from those scales (Keaton &Gearhart, 2014). They have been shown to replicate inat least six data sets in the US and Japan (Keaton, 2013;Keaton & Gearhart, 2013, 2014; Keaton, Gearhart, &Honeycutt, 2014; Keaton & Honeycutt, 2014;Watanabe, Keaton, & Tomiyama, 2014), have been sig-nificantly correlated with behavioral, cognitive, physio-logical, and psychological variables (Keaton, 2013;Keaton & Gearhart, 2013; Keaton & Honeycutt, 2014),and are a cumulative result of sport scale research anddevelopment.Antecedents to sport team identification. The

Causation of Sport Team Identification Scale (Keaton,2013; Keaton & Gearhart, 2013, 2014) was adminis-tered to study participants. The C-STIS measures teamidentification antecedents on a 7-point Likert scale andcontains 22 items across five latent constructs (MediaPopularity/Influence, Geography, Family, AthleticPerformance, and Team Characteristics). Four factors

were retained for this analysis: MediaPopularity/Influence (e.g., “I chose my favorite teambecause they receive a substantial amount of nationaltelevision coverage”; n = 4; � = .88), Geography (e.g., “Iam a fan of this team because it is an important con-nection between me and my hometown or university”;n = 5; � = .93), Family (“I chose my favorite teambecause my parents and/or family follow this team”; n= 5; � = .92), and Athletic Performance (which is aspectatorship motive factor important to identity for-mation; e.g., “Watching a well-executed athletic per-formance is something I enjoy”; n = 4; � = .84). Sport spectatorship motives. The second measure-

ment scale, the Scale of Sport Spectatorship Motives(Keaton, 2013; Keaton & Gearhart, 2014), explains rea-sons why people choose to become spectators of sport-ing events. The scale contains 18 items across four latentconstructs (Recreational Value, Fan Self-Concept,Aesthetics, and Casual Spectatorship). Three factorswere retained for this analysis: Recreational Value (e.g.,“One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games isto seek excitement and stimulation”; n = 4; � = .76), theextent of their Aesthetics (e.g., “One of my reasons towatch and attend sport games is the beauty and grace ofthe game”; n = 5; � = .88), and the extent to whichsomeone watches sport simply to pass time (CasualSpectatorship: e.g., “One of my reasons to watch andattend sport games is to kill time”; n = 4; � = .82).

Results

These data fit the proposed factor structure, χ2(413) =1041.93, p < .001, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .06, CI90% =.05, .06, providing evidence of construct validity.Furthermore, average variance extracted (AVE) hasbeen provided for each variable to provide evidence ofconvergent validity. AVE explains how much varianceaccounted for by each latent variable in comparison tothe amount of variance due to measurement error(Fornell & Larcker, 1981), or the degree of error-freevariance in a set of items consisting of a factor (Ping,2005). Typically, it is desirable for the average varianceextracted to be greater than .50, signifying that thevariance due to measurement error is less than half ofthe variance due to the construct. All of the factorsincluded in this analysis met the criterion (Table 2).Because these authors were interested in between-

class variation (i.e., multivariate group differences)concerning linear combinations of sets of continuousvariables, canonical linear discriminant models wereestimated for each measurement scale (identity forma-tion and spectatorship motives) in regard to the twoconsumer groups (CFB and NASCAR sport con-sumers). Significant roots indicated that the factors ofidentity formation and spectatorship motivation have

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 49

Table 2Scale Psychometrics for Identity Antecedents and Motivations

Factor/Item Standardized AVE αLoading

Media Popularity/Influence (identity antecedent) .84 .88I chose my favorite team because they receive a substantial amount of national television coverage. .89

I chose my favorite team because they receive a substantial amount of national newspaper coverage. .85

I chose my favorite team because they are popular. .74I chose my favorite team because they receive a substantial amount of radio coverage. .79

Geography (identity antecedent) .93 .93I follow my favorite team because I attended school in the same city or state. .91I chose my favorite team because it is close to a school I now, have, or hope to attend. .82I chose my favorite team because I live or have lived in or around the area. .93I have to support this team because it is located in my hometown or university. .78I chose my favorite team because of geographical reasons (like town, city, or state this team represents and/or I live in or around the area). .89

Family (identity antecedent) .88 .84I chose my favorite team because older family members follow this team. .88I chose my favorite team because my immediate family follows this team. .93One of the reasons for being a fan of the team is that my family members are fans of the team. .93

I have been a fan of my favorite team since childhood. .46I chose my favorite team because extended family members (e.g., cousin, aunt/uncle, grandparents) follow this team. .81

I chose my favorite team because my parents and/or family follow this team. .90

Athletic Performance (identity antecedent and motivation) .60 .84Watching a well-executed athletic performance is something I enjoy. .80I enjoy a skillful performance by the team. .85I am a spectator of sport because of sport competition. .56I enjoy watching a highly skilled player perform. .86

Casual Spectatorship (entertainment; spectatorship motivation) .52 .82One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is to occupy my free time. .76One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is to kill time. .80One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is just to keep me busy or occupied. .78

Recreational Value (entertainment; spectatorship motivation) .50 .76One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is to seek excitement and stimulation. .83

One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is to use it as a form of recreation. .66I like the stimulation I get from watching sports. .82I like to watch, read, and/or discuss sports because doing so gives me an opportunity to be with my family. .48

50 Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

differential multivariate associations with consumers ofCFB and NASCAR. This procedure allows the creationof sport consumer profiles for purposes of comparison.The discriminant dimension for the team identifica-

tion antecedent model was significant, F(5,500) =104.92, p < .001, rcanonical = .72. By examining thecanonical loadings (in Table 3) and group centroids(Table 4), we can observe that on the positive(NASCAR) end of the continuum, media influence is amore important antecedent of (driver) identity forma-tion, whereas on the negative (CFB) end, a combina-tion of geography and family are important in teamselection (Table 3). Accordingly, the notion that athletic performance (a

spectatorship motive) is a greater source of sport con-sumers’ identification for CFB consumers thanNASCAR consumers is not supported. According to

these data, there is no relative importance for thisantecedent (H6) and neither factor distinguishesbetween either type of sport consumer. Furthermore,the assertion that family socialization is of equalimportance to NASCAR and CFB sport consumptionis not supported (H3) as it is more strongly associatedwith the CFB consumer profile. Results support theclaim that geography is of greater relative importanceto identification with a CFB team rather than thoseidentifying with NASCAR drivers (H4) and that mediainfluence is of greater importance to identificationwith NASCAR drivers than with identification to col-lege football teams (H5). In the second model estimation, a significant root

indicated that the factors of spectatorship motivationhave differential impacts on CFB and NASCAR sportconsumers. The discriminant dimension was signifi-

Table 2Scale Psychometrics for Identity Antecedents and Motivations, continued

Factor/Item Standardized AVE αLoading

Aesthetics (spectatorship motivation) .51 .88One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is the beauty and grace of the game. .75

One of my reasons to watch and attend sport games is the artistic value of the game. .86I enjoy watching the artistry of my favorite sport. .78My favorite sport should be considered an art form. .75One of the main reasons that I watch, read, and/or discuss sports is for the artistic value. .75

Note: AVE = Average Variance Extracted

Table 3Standardized Discriminant Function Coefficients and Loadings for the Ability of Identity Formation, Spectatorship Moti-vation, and Psychological Effects to Categorize Different Sports

Factors Standardized function Function loadingcoefficient

Family (identity antecedent) .01 -.29Geography (identity antecedent) -1.01 -.85Media Popularity/Influence (identity antecedent) .55 .24Recreation (entertainment; spectatorship motive) -.29 -.68Casual Viewing (entertainment; spectatorship motive) .44 .32Athletic Performance (identity antecedent and spectatorship motive) -.01 -.14Aesthetics (spectatorship motive) .25 -.27

Note. Standardized discriminant coefficients indicate the relative importance of each variable. Discriminantloadings show the amount of variance shared among the linear combination of variables. Only moderate load-ings were considered of relative importance, using the common criteria of approximate values: .10 for small,.30 for moderate, and .50 for large.

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 51

cant, F(4,499) = 27.85, p < .001, rcanonical = .43. Byexamining the canonical loadings (in Table 3), we cansee that on the positive (NASCAR) end of the continu-um, watching sport casually was the strongest motiva-tion to watch sport, whereas on the negative (CFB)end, a combination of recreation and aesthetics wereimportant motivators (Table 3).There is limited support that entertainment motives

are the same for NASCAR and CFB sport consumers,because while recreation is higher for CFB sport con-sumers the casual viewing, motive is higher forNASCAR sport consumers (H1). Results do supportthe claim that achievement and success motives aregreater for CFB consumers (H2) but not that aestheticmotivations are of greater relative importance for sportconsumers of NASCAR drivers than CFB (H7).

Discussion

The goal of this research was to create sport consumerprofiles to compare a sport with a team as a point ofattachment (CFB) to a sport with an individual athleteas a point of attachment (NASCAR) in regard to iden-tity formation and spectatorship motivation. If differ-ences are isolated, then organizations can follow thesuggestion of Stewart et al. (2003) to strategically targetdifferent sport consumer segments for purposes ofincreasing consumption rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches that would not address the com-plexities of sport consumer beliefs, attitudes, andbehaviors. Prior researchers (Funk, Beaton, &Alexandris, 2012; Heere & James, 2007) have noted theimportance of advancing the theoretical understandingof sport consumer motivations and behaviors. The fol-lowing discussion highlights specific points in how theinstruments employed within this research help toadvance this theoretical understanding.There were observable differences between the two

consumer profiles regarding the measures of identityformation and spectatorship motivation. Overall, theCFB sport consumer profile paints a picture of an indi-vidual who is influenced by geography and familywhen choosing a favorite team and chooses to watchthat team for purposes of recreation and aesthetics.This finding helps to extend the knowledge and theo-retical understanding of CFB sport consumers, whichhas been set in prior research (Ferreira & Armstrong,2004; James & Ridinger, 2002; James & Ross, 2004). Inthis profile, it makes sense that those living near a col-lege football team would likely favor that team.However, given the proliferation of newer technologiesthat have helped non-geographically proximate EnglishPremier League soccer teams achieve popularity in theUS, we may see a change in the influence of geographyduring team identity formation in younger genera-

tions; but, as of the present, we conclude from thefindings that geographical proximity is still importantto this consumer group.College football sport consumption also appears as

more of a family engagement than NASCAR sportconsumption, suggesting that parents or family of thesport consumer also followed the team during her orhis formative years. Coinciding with the fact that recre-ation was found to be an important reason for viewing,sport consumers socialized by sources such as familyhave been shown to report higher levels of social obli-gation (Koch & Wann, 2013). In the southeastern US,for example, the phenomenon of “tailgating” is animmensely popular activity before CFB games, as sportconsumers from all over the region come to eat anddrink together hours (if not days) before the actualcontest, adorned with team paraphernalia to proclaimtheir allegiance and to identify themselves as part of anin-group. In some sense, as Koch and Wann (2013)have indicated, being a Southerner almost creates theobligation to tailgate at college football games withother Southerners and other CFB sport consumers.Although pilgrimages to NASCAR events may rivalthese tailgating events in terms of social function, weconclude from the results that this type of social gath-ering was more important to CFB sport consumers inthis study. Admittedly, the student participants in thisstudy likely do not have the time and financialresources to follow NASCAR drivers nationwide andenjoy those social benefits. Perhaps we can also specu-late that those who make pilgrimages to NASCARevents are more highly identified, and the typical sportconsumer—presumably those who are lesser identi-fied—do not expend those types of resources on racingevents. Lastly, the consumer profile of a sport con-sumers with a CFB team as a point of attachmentincludes appreciation of the aesthetics of football,where consumers indicate that the beauty and theartistic value of the game are important. In contrast, a NASCAR sport consumer was more

likely to identify with a particular driver because thatdriver received a substantial amount of media cover-age. Drivers such as Dale Earnhardt, Jr. and DanicaPatrick, who can be frequently seen in television adver-tisements, exemplify this phenomenon. Thus, to attractsport consumers to a driver, NASCAR owners couldexpand efforts to garner media attention for less popu-lar drivers and focus on characteristics that are moreappealing to these sport consumers. Previous researchinto NASCAR and consumer behavior has examinedthe connection between sport consumers and theirfocus on brands within the sport (Dees, Bennett, &Ferreira, 2010; Kinney, McDaniel, & DeGaris, 2008;Levin et al., 2004; Levin, Joiner, & Cameron, 2001).

This study supports the authors’ attempts to push for-ward the examination of NASCAR consumer behaviorbeyond understanding brand associations, and moretowards the motivations and identifications that theseconsumers make with individual athletes (Roy, Goss, &Jubenville, 2010). Results also indicate geography andfamily are less influential factors when choosing a driv-er to support. NASCAR sport consumers are moreprone to watch the sport casually—to occupy free timeor to keep busy—rather than for recreational value (toseek excitement or stimulation). By recognizing the similarities and differences

between consumers of team and individual sports thisstudy supports the authors’ attempts to advance thetheoretical understanding of sport consumers as indi-viduals. From a consumer behavior perspective, thefindings lead us to conclude there are important differ-ences between consumers of sports with differingpoints of attachment (see Table 5 for a summary).Through this distinction, the theoretical conception ofsport consumers should be considered more compre-hensively, especially when practically applied by organ-

izations for marketing or managerial purposes. Theresults also provide insight into how individuals maybecome sport consumers of certain teams or individualathletes. Where consumers of team sports often makeconnections through social and geographical ties, fansof individual drivers are able to connect because of theexposure those athletes receive. Taking theoreticalunderstanding to an empirical and practical level, it ispossible to potentially make important decisions in themanagement of sport organizations and media fromthese findings, which suggest that psychological vari-ables associated with personality and identity are asimportant in these contexts as those related to con-sumerism. The results of this research display the importance of

media exposure in having consumers identify with anindividual athlete be it NASCAR, golf, tennis, or swim-ming. With this knowledge in hand, a manager ormarketer for a sport brand should understand thatmarketing and displaying an individual helps to buildstrong ties to that individual. While many teams dofully employ this strategy (i.e., the Los Angeles Lakerswith Kobe Bryant), it may work better with individualathletes as points of attachment when paired in tan-dem with other variables to which it was related in thisstudy, particularly regarding the importance NASCARsport consumers place on recreation as a spectatorshipmotivation. Organizations should ask themselves whattypes of athletes create an atmosphere through whichsport consumers will choose a NASCAR outing as arecreational activity over other types of activities (espe-cially when attempting to attract new sport con-sumers). Using NASCAR as an example, packaging

52 Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Table 4Group Centroids on Discriminant Functions

Factors Group centroids

Identity FormationNASCAR 1.39College Football -.75

Spectatorship MotivesNASCAR .66College Football -.34

Table 5Summary of Findings and Implications

Findings Marketing/Management Implications

1. Differences exist between the Marketing to consumers should focus on specific factors through consumer profiles of NASCAR which individuals come to identify with teams and drivers, and on and CFB. factors motivating consumers to watch the two sports

2. CFB identification is linked to Marketers can target groups for consuming team sport based on their geography, aesthetics and locale, as well as the aesthetics of the sport. Additionally, sport recreation. consumers may identify sport with recreational activities such as

tailgating

3. NASCAR driver identification is Marketers and mangers may be able to enhance the interest in certain greatly driven by media individual athletes through additional coverage. There is a need to coverage. consider the balance of coverage provided to the various athletes

within a sport competition, such as a lesser well known driver who might exemplify traits that encourage new fan attendance and spectatorship.

lesser known and upcoming drivers in television adver-tisements with popular racers like Dale Earnhardt, Jr.in ways that depict shared activity and recreation maybe a strategy for increasing sport consumers identifica-tion. Because athletic performance had the highestmean of the NASCAR driver identification variables(see Table 6), NASCAR officials may wish to instructtheir best drivers to behave in ways that attract thosewho might choose a NASCAR event for their recre-ational activities. NASCAR can follow the lead of teamsports, where this practice can be observed by a deci-sion made by David Stern, the former commissioner ofthe National Basketball Association (NBA). OnOctober 17, 2005, Stern implemented a dress code forhis players, attempting to change the manner in whichthe athletes were perceived by sport consumers, there-by attempting to portray a safer, more conservativeimage rather than the one previously portrayed (moreassociated with the supposedly negative aspects of hip-hop culture). At the same time, it may be more difficult to market

a whole team to sport consumers outside of a geo-graphical region in which that team is based; one mightconsider yet unsuccessful efforts the National FootballLeague (NFL) has made to appeal to international audi-ences. One solution to marketing a sporting event withteams tied to certain geographic locations would not beto feature the two teams and the potential matchupbetween the groups, but instead to highlight and focuson certain star individuals on the teams and the charac-teristics of those players. In this mode, a sport organiza-tion could potentially make further connections withconsumers across larger geographic areas.Some strategies for intensifying sport consumer

identification with an individual athlete—and henceexpanding the ability to efficiently target audiences forconsumption—include increasing player accessibilityto the public, increasing community involvementactivities, fostering characteristics that cater toward

consumers’ preferences and motivations, and creatingopportunities for group affiliation and participation—all of which nurture a sense of social identity in an usversus them fashion (Sutton et al., 1997). Results of thisresearch and implications of consumer behavior wouldreinforce the existing practice that a NASCAR sponsorwould want to employ an individual driver in a mediaor marketing campaign to gain exposure, but reinforcethe practice in tandem with additional tactics.Individual sports could target lesser-known athletesthat exemplify characteristics that encourage new sportconsumers to attend events. This research helps to pro-vide an important profile of racing sport consumersfor stakeholders in NASCAR and other individualsports to better understand the individuals who areinterested in single athletes. Capturing a better profileof race consumers could not only benefit marketingand sales campaigns, but could also be employed totarget sport consumers more efficiently, as well asimprove race operations and management of proper-ties and stakeholders in dealing with consumers.

LimitationsWithin this study there are potential limitations. Thefirst is the sample employed to collect the data. A larg-er sample from a wider demographic range would havebeen ideal. However, because of various restrictions,the sample for this study was limited to university stu-dents. The use of students is a widely employed strate-gy for research projects, especially ones that focus onsport identification and consumption. Thus, while theuse of student subjects within this research is notentirely ideal, it is an acceptable research practice. Inour case, the sample may have had the potential to biasresults given that these data were collected at a schoolpopular for its football program. Variables such asgeography, family, and social motivations may havebeen particularly influenced in this sample.

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 53

Table 6Means, Standard Deviations (SD), and Ranks for Identity Formation and Spectatorship Motivation Factors

NASCAR College FootballVariable Mean Rank SD Mean Rank SD

Family (identity antecedent) 3.72 3 1.55 4.69 3 1.70Geography (identity antecedent) 2.54 4 1.45 5.20 2 1.96Media Influence (identity antecedent) 4.07 2 1.36 3.27 4 1.56Athletic Performance (identity antecedent and motive) 5.59 1 1.15 5.92 1 1.10

Recreation (entertainment; motive) 3.41 1 0.74 3.92 1 0.78Casual Viewing (entertainment; motive) 3.01 3 0.82 2.70 3 1.00Aesthetics (motive) 3.04 2 0.90 3.29 2 0.91

A second limitation that exists within this study isthe focused nature of research within a certain regionof the United States. While the sample is suitable forthis manuscript, future research studies could considera larger sample group from various demographic back-grounds both within the US and other countries. Thereis need for further testing of this methodology in vari-ous contexts.Finally, these authors wish to address the fact that we

only tested a small number of identification and moti-vation variables. There are myriad influences on thedevelopment of an individual’s identity and their moti-vations to consume sport. These authors chose toexplicate on a small cross-section of that process;mainly authors felt that previous research directedthem to include variables relevant to socialization (i.e.,family, community, media, recreation, and spectator-ship). Future research should begin to explicate otherrelevant areas.

Future Research and ConclusionIn further consideration of the results and implica-tions, future researchers should also continue to inves-tigate several important areas and contexts. This studyincluded the differences between CFB and NASCARsport consumers in the US, and though this specificcontext is unique and important, future researchshould consider the vast array of sport consumers ofindividual athletes—especially in other cultures—andhow they compare to one another. Future researchersshould consider how sport consumers are similar anddifferent from one another in other types of individualsports, such as tennis, golf, drag racing, and track andfield, to name a few of many. Clearly there are a largenumber of contexts through which to consider differ-ent types of sport consumerism and how they compareto one another, as well as relations to other types ofsport consumers with different points of attachment.Future research can help to expand theoretical andempirical understanding of sport consumers. The aim of this study was to compare sport con-

sumer profiles of CFB and NASCAR sport consumersin regard to antecedents of identification and specta-torship motivations. In support of several hypotheses,findings indicate that media influence is a key contrib-utor to identification with NASCAR drivers, whereasgeography and family socialization are integral sourcesof CFB team identification. Results also show thatachievement and success motives are of greater impor-tance for CFB sport consumers than NASCAR sportconsumers. Considering these results, several strategiesand recommendations were discussed to help organi-zations and marketers of both team and individual

sports increase consumption by current sport con-sumers and continue to grow audiences.

ReferencesByrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS (2nd ed.).

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Routledge.Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd

ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Corso, R. A. (2013, January 17). Football continues to be America’s favorite

sport; the gap with baseball narrows slightly this year. Harris Interactive.Dees, W., Bennett, G., & Ferreira, M. (2010). Personality fit in NASCAR:

An evaluation of driver-sponsor congruence and its impact on sponsor-ship effectiveness outcomes. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 19, 25-35.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: Aflexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, andbiomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175-191.

Ferreira, M., & Armstrong, K. L. (2004). An exploratory examination ofattributes influencing students’ decisions to attend college sport events.Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13, 194-208.

Fink, J. S., Trail, G. T., & Anderson, D. F. (2002). Environmental factorsassociated with spectator attendance and sport consumption behavior:Gender and team differences. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 11, 8-19.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation modelswith unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of market-ing research, 18, 39-50.

Funk, D. C., Beaton, A., & Alexandris, K. (2012). Sport consumer motiva-tion: Autonomy and control orientations that regulate fan behaviours.Sport Management Review, 15, 355-367.

Funk, D. C., Mahony, D. F., & Ridinger, L. L. (2002). Characterizing con-sumer motivation as individual difference factors: augmenting the SportInterest Inventory (SII) to explain level of spectator support. SportMarketing Quarterly, 11, 33-43.

Gantz, W. (1981). An exploration of viewing motives and behaviors associ-ated with television sports. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media,25, 263-275.

Heere, B., & James, J. D. (2007). Stepping outside the lines: Developing amulti-dimensional team identity scale based on social identity theory.Sport Management Review, 10, 65-91.

Hugenberg, L. W., & Hugenberg, B. S. (2008). If it ain’t rubbin’, it ain’tracin’: NASCAR, American values, and fandom. The Journal of PopularCulture, 41, 635-657.

James, J. D. (2001). The role of cognitive development and socialization inthe initial development of team loyalty. Leisure Sciences, 23, 233-261.

James, J. D., & Ridinger, L. L. (2002). Female and male sport fans: A com-parison of sport consumption motives. Journal of Sport Behavior, 25,260-278.

James, J. D., & Ross, S. D. (2004). Comparing sport consumer motivationsacross multiple sports. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13, 17-25.

Jones, I. (1997). A further examination of the factors influencing currentidentification with a sports team; A response to Wann et al. (1996).Perceptual and Motor Skills, 85, 257-258.

Keaton, S. A. (2013). Sport team fandom, arousal, and communication: Amultimethod comparison of sport team identification with psychological,cognitive, behavioral, affective, and physiological measures. Doctoral dis-sertation, Louisiana State University.

Keaton, S. A., & Gearhart, C. C. (2014). Identity formation, identitystrength, and self-categorization as predictors of effective and psycho-logical outcomes: A model reflecting sport team fans’ responses to high-lights and lowlights of a college football season. Communication &Sport, 2, 363-385.

Keaton, S. A., & Gearhart, C. C. (2014). Measuring self-reported perceptionsof sport fandom: Evaluating, developing, and refining existing scales insport psychology. Paper presented at the Seventh Summit onCommunication and Sport, Brooklyn, NY.

54 Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Keaton, S. A., Gearhart, C. C., & Honeycutt, J. M. (2014). Fandom and psy-chological enhancement: Effects of sport team identification and imag-ined interaction on self-esteem and management of social behaviors.Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 33, 251-269.

Keaton, S. A., & Honeycutt, J. M. (2014). The effects of sport fandom onphysiology, communication, and mental health. In J. M. Honeycutt, C.Sawyer, & S. A. Keaton (Eds.), The influence of communication in physi-ology and health. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Kinney, L., McDaniel, S. R., & DeGaris, L. (2008). Demographic and psy-chographic variables predicting NASCAR sponsor brand recall.International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 9, 169-179.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Koch, K., & Wann, D. L. (2013). Fans’ identification and commitment to asport team: The impact of self-selection versus socialization processes.Athletic Insight: The Online Journal of Sport Psychology, 15(2).

Kwon, H., & Trail, T. (2001). Sport fan motivation: A comparison ofAmerican students and international students. Sport MarketingQuarterly, 10, 147-155.

Levin, A. M., Beasley, F. M., & Gamble, T. (2004). Brand loyalty ofNASCAR fans towards sponsors: The impact of fan identification.International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 6, 11-21.

Levin, A. M., Beasley, F. M., & Gilson, R. L. (2008). NASCAR fans’ respons-es to current and former NASCAR sponsors: The effect of perceivedgroup norms and fan identification. International Journal of SportsMarketing & Sponsorship, 9, 193-204.

Levin, A. M., Joiner, C., & Cameron, G. (2001). The impact of sports spon-sorship on consumers’ brand attitudes and recall: The case of NASCARfans. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 23(2), 23-31.

McDonald, M. A., Milne, G. R., & Hong, J. (2002). Motivational factors forevaluating sport spectator and participant markets. Sport MarketingQuarterly, 11, 100-113.

Ping, R. A. (2005). What is the average variance extracted for a latent vari-able interaction (or quadratic)? Retrieved fromhttp://home.att.net/~rpingjr/ave1.doc

Pitts, B., & Stotlar, D. (1996). Fundamentals of sport marketing.Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2006). A first course in structural equationmodeling (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Roy, D. P., Goss, B. D., & Jubenville, C. B. (2010). Influences on eventattendance decisions for stock car automobile racing fans. InternationalJournal of Sport Management and Marketing, 8, 73-92.

Shilbury, D., Quick, S., & Westerbeek, H. (1998). Strategic sport marketing.Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin.

Smith, G. J. (1989). The noble sports fan redux. Journal of Sport & SocialIssues, 13, 121-130.

Spinda, J. S. W. (2011). The development of Basking in Reflected Glory(BIRGing) and Cutting off Reflected Failure (CORFing) measures.Journal of Sport Behavior, 34, 392-420.

Spinda, J. S. W. (2012). From good ol’ boys to national spectacle: Motivesand identification among young NASCAR fans. In A. C. Earnheardt, P.Haridakis, & B. Hugenber (Eds.), Sports fans, identity, and socialization:Exploring the fandemonium (pp. 177-189). Lanham, MD: LexingtonBooks.

Spinda, J. S. W., Earnheardt, A. C., & Hugenberg, L. W. (2009). Checkeredflags and mediated friendships: Parasocial interaction among NASCARfans. Journal of Sports Media, 4, 31-55.

Stewart, R. K., Smith, A. C., & Nicholson, M. (2003). Sport consumertypologies: A critical review. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12, 206-216.

Sutton, W. A., McDonald, M. A., Milne, G. R., & Cimperman, J. (1997).Creating and fostering fan identification in professional sports. SportMarketing Quarterly, 6, 15-22.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5thed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Trail, G. T., Robinson, M. J., Dick, R. J., & Gillentine, A. J. (2003). Motivesand points of attachment: Fans versus spectators in intercollegiate ath-letics. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12, 217-227.

Wann, D. L. (1995). Preliminary validation of the sport fan motivationscale. Journal of Sports and Social Issues, 19, 377-396.

Wann, D. L. (2006). The causes and consequences of sport team identifica-tion. In A. A. Raney & J. Bryant (Eds.), Handbook of sports and media(pp. 331-352). Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wann, D. L., Grieve, F. G., Zapalac, R. K., & Pease, D. G. (2008).Motivational profiles of sport fans of different sports. Sport MarketingQuarterly, 17, 6-19.

Wann, D. L., Schrader, M. P., & Wilson, A. M. (1999). Sport fan motiva-tion: Questionnaire validation, comparisons by sport, and relationshipto athletic motivation. Journal of Sport Behavior, 22, 114-139.

Wann, D. L., Tucker, A., & Schrader, M. P. (1996). An exploratory exami-nation of the factors influencing the origination, continuation, and ces-sation of identification with sports teams. Perceptual and Motor Skills,82, 995-1001.

Wann, D. L., & Waddill, P. J. (2003). Predicting sport fan motivation usinganatomical sex and gender role orientation. North American Journal ofPsychology, 5, 485-498.

Watanabe, N. M., Keaton, S. A., & Tomiyama, K. (2014). A cross-culturalexamination of sport fandom: Japanese and US team identity formation,spectatorship motives, and psychological effects. Paper presented at theSeventh Summit on Communication and Sport, Brooklyn, NY.

Volume 24 • Number 1 • 2015 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 55