World AIDS Day

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of World AIDS Day

La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée orientale

Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

Volume 25 / No. 12December/Décembre

املجلد اخلامس والعرشون / عدد 122019ديسمرب/كانون األول

Eastern Mediterranean H

ealth Journal Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

#Integrate HIVservices World AIDS Day1 December 2019

Of the 37.9 million people living with HIV at the end of 2018, 79% received testing, 62% received treatment, and 53% had achieved suppression of the HIV virus with reduced risk of infecting others. Thousands of community health workers and members of the HIV and key population networks contributed to this success. On World AIDS Day 2019, WHO is highlighting the difference these communities are making to end the HIV epidemic, while drawing global attention to the need for their broader engagement in strengthening primary health care.

EditorialEffective health information systems for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals and the universal health coverage agendaArash Rashidian ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................849

Research articlesRole of climatic factors in the incidence of dengue in Port Sudan City, SudanElsiddig Noureldin and Lynn Shaffer ....................................................................................................................................................................................................852

Coût hospitalier des pneumococcies invasives chez les enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans en TunisieArwa Ben Salah, Sana El Mhamdi, Manel Ben Fredj, Chebil Ben Meriem, Jihen Bouguila, Khaled Ben Helel, Lamia Sfaihi, Rafiaa Mustapha, Mohamed Sfar et Mohamed Soltani...................................................................................................861

Fingernail length as a predisposing factor for perforations of latex gloves: a simulated clinical experimentSuhail Al-Amad, Ala’a El-Saleh, Shorouk Elnagdy, Fatimah Al-Nasser and Sarah Alsellemi ................................................................................................872

Workplace stress and its relation to cardiovascular disease risk factors among bus drivers in EgyptAmira Mohsen and Sally Hakim .............................................................................................................................................................................................................878

Quality of life outcomes in thalassaemia patients in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional studySoheir Adam ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................887

Mediterranean dietary patterns and risk of type 2 diabetes in Islamic Republic of IranMarjan Ramezan, Golaleh Asghari, Parvin Mirmiran, Zhale Tahmasebinejad and Fereidoun Azizi ..............................................................................896

Knockdown resistance mutations contributing to pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti population, Saudi ArabiaOmer Dafalla, Adel Alsheikh, Waheed Mohammed, Khalid Shrwani, Feras Alsheikh, Yahya Hobani and Elsiddig Noureldin ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................905

ReviewStrategies to reduce informal payments in health systems: a systematic reviewHamed Zandian, Atefeh Esfandiari, Minoo Sakha and Amirhossein Takian ..........................................................................................................................914

ReportMove for health: addressing the built environment and physical activity in OmanRuth Mabry, Huda Al Siyabi, Muhssen Kannan and Amal Al Siyabi ..........................................................................................................................................923

WHO events addressing public health prioritiesRegional consultative meeting on primary health care for universal health coverage ........................................................928

Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal

IS the official health journal published by the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office of the World Health Organization. It is a forum for the presentation and promotion of new policies and initiatives in public health and health services; and for the exchange of ideas, concepts, epidemiological data, research findings and other information, with special reference to the Eastern Mediterranean Region. It addresses all members of the health profession, medical and other health educational institutes, interested NGOs, WHO Collaborating Centres and individuals within and outside the Region.

املجلة الصحية لرشق املتوسط هى املجلة الرسمية التى تصدر عن املكتب اإلقليمى لرشق املتوسط بمنظمة الصحة العاملية. وهى منرب لتقديم السياسات واملبادرات اجلديدة يف الصحة العامة واخلدمات الصحية والرتويج هلا، ولتبادل اآلراء واملفاهيم واملعطيات الوبائية ونتائج األبحاث وغري ذلك من املعلومات، وخاصة ما يتعلق منها بإقليم رشق املتوسط. وهى موجهة إىل كل أعضاء املهن الصحية، والكليات الطبية وسائر املعاهد التعليمية، وكذا املنظامت غري احلكومية املعنية، واملراكز املتعاونة مع منظمة

الصحة العاملية واألفراد املهتمني بالصحة ىف اإلقليم وخارجه.

La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée Orientale

EST une revue de santé officielle publiée par le Bureau régional de l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé pour la Méditerranée orientale. Elle offre une tribune pour la présentation et la promotion de nouvelles politiques et initiatives dans le domaine de la santé publique et des services de santé ainsi qu’à l’échange d’idées, de concepts, de données épidémiologiques, de résultats de recherches et d’autres informa-tions, se rapportant plus particulièrement à la Région de la Méditerranée orientale. Elle s’adresse à tous les professionnels de la santé, aux membres des instituts médicaux et autres instituts de formation médico-sanitaire, aux ONG, Centres collaborateurs de l’OMS et personnes concernés au sein et hors de la Région.

Correspondence

Editor-in-chief

Eastern Mediterranean Health JournalWHO Regional Office for the Eastern MediterraneanP.O. Box 7608 Nasr City, Cairo 11371 Egypt Tel: (+202) 2276 5000 Fax: (+202) 2670 2492/(+202) 2670 2494 Email: [email protected]

Members of the WHO Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean Afghanistan . Bahrain . Djibouti . Egypt . Islamic Republic of Iran . Iraq . Jordan . Kuwait . Lebanon Libya . Morocco . Oman . Pakistan . Palestine . Qatar . Saudi Arabia . Somalia . Sudan . Syrian Arab Republic Tunisia . United Arab Emirates . Yemen

البلدان أعضاء اللجنة اإلقليمية ملنظمة الصحة العاملية لرشق املتوسط األردن . أفغانستان . اإلمارات العربية املتحدة . باكستان . البحرين . تونس . ليبيا . مجهورية إيران اإلسالمية

اجلمهورية العربية السورية . جيبويت . السودان . الصومال . العراق . ُعامن . فلسطني . قطر . الكويت . لبنان . مرص . املغرباململكة العربية السعودية . اليمن

Membres du Comité régional de l’OMS pour la Méditerranée orientale Afghanistan . Arabie saoudite . Bahreïn . Djibouti . Égypte . Émirats arabes unis . République islamique d’Iran Iraq . Libye . Jordanie . Koweït . Liban . Maroc . Oman . Pakistan . Palestine . Qatar . République arabe syrienne Somalie . Soudan . Tunisie . Yémen

Subscriptions and Permissions

Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Knowledge Sharing and Production, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, PO Box 7608, Nasr City, Cairo 11371, Egypt (tel: +202 2670 2535, fax: +202 2670 2492; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce, in part or in whole, or to translate publications of WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, at the above address; email: [email protected].

EMHJ is a trilingual, peer reviewed, open access journal and the full contents are freely available at its website: http://www/emro.who.int/emhj.htm

EMHJ information for authors is available at its website: http://www.emro.who.int/emh-journal/authors/

EMHJ is abstracted/indexed in the Index Medicus and MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Systems on Line), ISI Web of knowledge, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Lexis Nexis, Scopus and the Index Medicus for the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR).

© World Health Organization (WHO) 2019. Some rights reserved.This work is available under the CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

If authors are staff members of the World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the World Health Organization.

ISSN 1020-3397

Cover 25-03.indd 4-6 4/25/2019 11:15:19 AM

Editorial

Effective health information systems for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals and the universal health coverage agendaArash Rashidian ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................849

Research articlesRole of climatic factors in the incidence of dengue in Port Sudan City, SudanElsiddig Noureldin and Lynn Shaffer .........................................................................................................................................................................852

Coût hospitalier des pneumococcies invasives chez les enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans en TunisieArwa Ben Salah, Sana El Mhamdi, Manel Ben Fredj, Chebil Ben Meriem, Jihen Bouguila, Khaled Ben Helel, Lamia Sfaihi, Rafiaa Mustapha, Mohamed Sfar et Mohamed Soltani ........................................................................861

Fingernail length as a predisposing factor for perforations of latex gloves: a simulated clinical experimentSuhail Al-Amad, Ala’a El-Saleh, Shorouk Elnagdy, Fatimah Al-Nasser and Sarah Alsellemi......................................................................872

Workplace stress and its relation to cardiovascular disease risk factors among bus drivers in EgyptAmira Mohsen and Sally Hakim ..................................................................................................................................................................................878

Quality of life outcomes in thalassaemia patients in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional studySoheir Adam.........................................................................................................................................................................................................................887

Mediterranean dietary patterns and risk of type 2 diabetes in Islamic Republic of IranMarjan Ramezan, Golaleh Asghari, Parvin Mirmiran, Zhale Tahmasebinejad and Fereidoun Azizi ...................................................896

Knockdown resistance mutations contributing to pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti population, Saudi ArabiaOmer Dafalla, Adel Alsheikh, Waheed Mohammed, Khalid Shrwani, Feras Alsheikh, Yahya Hobani and Elsiddig Noureldin ...................................................................................................................................................................................................905

ReviewStrategies to reduce informal payments in health systems: a systematic reviewHamed Zandian, Atefeh Esfandiari, Minoo Sakha and Amirhossein Takian ................................................................................................914

ReportMove for health: addressing the built environment and physical activity in OmanRuth Mabry, Huda Al Siyabi, Muhssen Kannan and Amal Al Siyabi ................................................................................................................923

WHO events addressing public health priorities

Regional consultative meeting on primary health care for universal health coverage ...........................................................928

Vol. 25.12 – 2019

La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée orientale

Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal

Ahmed Al-Mandhari Editor-in-ChiefArash Rashidian Executive EditorAhmed Mandil Deputy Executive EditorPhillip Dingwall Managing Editor

Editorial Board Zulfiqar Bhutta Mahmoud Fahmy Fathalla Rita Giacaman Ahmed Mandil Ziad Memish Arash Rashidian Sameen Siddiqi Huda Zurayk

International Advisory Panel Mansour M. Al-Nozha Fereidoun Azizi Rafik Boukhris Majid Ezzati Hans V. Hogerzeil Mohamed A. Ghoneim Alan Lopez Hossein Malekafzali El-Sheikh Mahgoub Hooman Momen Sania Nishtar Hikmat Shaarbaf Salman Rawaf

Editorial assistantsNadia Abu-Saleh, Suhaib Al Asbahi (graphics), Diana Tawadros (graphics)

Editorial supportGuy Penet (French editor)Eva Abdin, Fiona Curlet, Cathel Kerr, Marie-France Roux (Technical editors)Ahmed Bahnassy, Abbas Rahimiforoushani (Statistics editors)

Administration Iman Fawzy, Marwa Madi

Web publishingNahed El Shazly, Ihab Fouad, Hazem Sakr

Library and printing supportHatem Nour El Din, Metry Al Ashkar, John Badawi, Ahmed Magdy, Amin El Sayed

Cover and internal layout designed by Diana Tawadros and Suhaib Al Asbahi Printed by WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt

849

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Editorial

Effective health information systems for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals and the universal health coverage agenda

1Director of Science, Information and Dissemination, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt. (Correspondence to: Arash Rashidian: [email protected]).

Citation: Rashidian A. Effective health information systems for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals and the universal health coverage agen-da. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(12):849–851. https://doi.org/10.26719/2019.25.12.849

Universal health coverage (UHC) and the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) cannot be achieved without the appropriate measurement and monitoring mechanisms (1). At the global level, extensive attention is given to mechanisms that focus on measuring and reporting the status of SDG indicators, to help in shaping global priorities, and to steer political will and leverage for action at the national level. National decision-making, however, goes beyond accepting UHC and the SGDs as targets: it should also include specific policies that improve access to health services and health outcomes . The importance of such detail has been well documented before, including in the case of a major global policy for child health (2).

Unfortunately, most global comparisons and the summary indices developed from them are not sensitive enough to national policy change and may not help countries in this direction (3). It is hard to imagine that the phenomenal country successes witnessed in the post-Alma Ata primary health care implementation era would have been as successful as they were, if they had relied on global estimation and reporting processes as sources of data (4). The pivotal role of collecting data on a small set of locally-relevant and policy-oriented indicators, using the paper-based approaches of the time, in the success of primary health care implementation plans is well documented (5). The same is true today; countries cannot reach UHC objectives and the SDGs by relying only on international comparisons and estimation processes.

National health information systems that respond to national needs and are efficient are required. Such national systems provide the locally-relevant information from routine sources (e.g. civil registration and vital statistics systems and health care facilities), as well as from household surveys and census surveys, that is required for national planning and monitoring of implementation. The results framework of WHO’s Thirteenth General Programme of Work, 2019‒2023, is intended as an overarching approach to data and information for health (6). It is a WHO commitment that its work with countries, alongside other United Nations agencies and partners, results in improved health outcomes (7). The framework includes a set of key indicators that complements the SDG agenda, with a further focus on the triple objectives of improving UHC, enhancing safety and increasing population health (7). Alongside this, it includes a core set of activities to improve national data systems so that globally comparable data are valid, timely

and reliable, while countries benefit from the availability of the information needed for national and subnational planning, policy implementation and monitoring of health outcomes and equity objectives (8).

In countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region, WHO work in this area is within the domains outlined in Table 1. The core health indicators agenda (including the health-related SGD indicators) (9), reflects the global approach to regular reporting of comparable data from countries. The regional civil registration and vital statistics systems agenda is a key initiative in response to the many limitations of the current systems in most countries of the Region, and is focused on timely and complete registration of deaths, and accurate certification of the cause of death (10). Regarding surveys, WHO supported the conduct of its first pilot of the new World Health Survey approach (WHS+) in 2016 in Tunisia and a model national survey plan has been developed for use by countries. This was a response to the observation that in many countries surveys were done as a response to global or donor requests rather than national needs, and that many surveys with considerable overlap were conducted too close to each other, while several years might pass with no national household survey undertaken in the country.

In terms of routine health information system development, regional initiatives have been developed to assess national health information systems (followed by strategy development), and a programme of capacity-building for countries in need of District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS-2) package implementation has been carried out (11). Recently, the agenda has been expanded to include the Primary Health Care Measurement and Improvement Initiative (PHCMI), and a similar approach is being developed for hospital information system support (12). Following the release of the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), extensive work has been undertaken to support its adoption in countries as the basic standard for data reporting on mortality and morbidity. This work is now being expanded to encompass the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) due to be released in 2020, and technical support is being provided to ensure that all health-related data systems are based on these global approaches and WHO-sanctioned standards for health data.

While the Region faces many structural limitations on national data improvement, these programmes that

Arash Rashidian1

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Editorial

850

are based on strong national political commitment and country demand have resulted in key improvements to data systems and coverage (13). A few countries of the Region are experiencing emergencies that negatively affect their national systems for health data, while massively increasing the need for data generation. While data systems for emergency settings are beyond the scope of this short article, they are an important part of

WHO’s work in this area (14). In the end, these initiatives are as successful as the commitment given to them on the ground. Health information systems and the data generated by the estimation process have important comparative value, but their best use is when they can equip policy-makers and managers with the evidence and knowledge they need for decision-making (15). This is the goal that we are striving towards.

References1. Health in 2015: from MDGs to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

2. Ahmed HM, Mitchell M, Hedt B. National implementation of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI): policy con-straints and strategies. Health Policy. 2010;96(2):128‒133. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.01.013.

3. AbouZahr C, Boerma T, Hogan D. Global estimates of country health indicators: useful, unnecessary, inevitable? Glob Health Action. 2017;10(sup1):1290370. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1290370.

4. Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, Van Lerberghe W. The contribution of primary care to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of major primary care initiatives. Social Sci Med. 2010;70:904–911. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.025.

5. Mehryar AH, Naghavi M, Ahmad-Nia S, Kazemipour S. Vital horoscope: longitudinal data collection in the Iranian primary health care system. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2008:23(3):55‒74. doi:10.18356/ea6aec90-en

6. Thirteenth general programme of work, 2019–2023. Results framework: an update. Geneva: World Health Organization: 2019.

7. Mahjour J, Mirza Z, Rashidian A, Atta H, Hajjeh R, Thieren M, El-Adawy M, Hammerich A, Al-Yousfi A, Haka RB, El Khodary H. “Promote health, keep the world safe, serve the vulnerable in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2018:24(4):323‒324. doi:10.26719/2018.24.4.323.

8. SCORE to reach your health goals: a technical package to strengthen country health data (working document). Geneva: World Health Organization: 2018.

9. Alwan A, Ali M, Aly E, Badr A, Doctor H, Mandil A, et al. Strengthening national health information systems: challenges and response. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;22(11):840‒850.

Table 1 WHO initiatives for improving national information WHO strategic areas of support for improving availability and use of health data

Global WHO initiatives Current WHO initiatives for data systems in the Eastern Mediterranean Region

Global comparison of nationally representative indicators, and enhancing visibility and use of national and subnational indicators

SDG monitoring and indicators WHO Impact FrameworkGlobal Health Observatory

Regional SDGs and core-indicator reportingRegional Health Observatory

Enhancing national health information systems and infrastructure, including birth and death registration and certification of cause of death

SCORE assessments and package of health information system initiativesSupport for DHIS-2 development

National civil registration and vital statistics system assessments and strategiesComprehensive national health information system assessmentRegional SCORE reviewDHIS-2 implementation in target countriesPHCMI analysis and reporting support

National capacity-building and support for household surveys, and subnational and equity-oriented analyses

World Health Survey (WHS+)Health equity assessment toolkit (HEAT Plus) WHO STEPwise approach to Surveillance (STEPS) surveysService availability and readiness assessment (SARA) surveysDisease-specific surveys

WHS+ global pilotsDeveloping national household survey plansSARA survey conduct and analysisSupport for other surveysSupport for national health observatories

Enhancing national health information systems and infrastructure, including birth and death registration and certification of cause of death

WHO family of international classifications, including ICD-11, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and ICHI

ICD-10 and ICD-11 implementationICHI capacity-building and pilot implementation

851

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Editorial

10. Resolution EM/RC60/R.7. Regional strategy for the improvement of civil registration and vital statistics systems 2014–2019. Cai-ro: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2013 (http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/RC60_Resolutions_2013_R7_15140_EN.pdf?ua=1, accessed 22 December 2019).

11. Sahay S, Rashidian A, Doctor HV. Challenges and opportunities of using DHIS2 to strengthen health information systems in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A regional approach. Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12108 (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/isd2.12108, accessed 22 December 2019).

12. Rashidian A, Doctor H, Aly E, Badr A. Health information in primary care and family practice: concept, status and a vision for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. In: Salah H, Kidd M, editors. Family practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: universal health coverage and quality primary care. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press; 2019:57‒73.

13. Eastern Mediterranean Region: framework for health information systems and core indicators for monitoring health situation and health system performance 2018. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2018 (https://rho.emro.who.int/sites/default/files/booklets/EMR-HIS-and-core-indicators-2018.pdf%20, accessed 22 December 2019).

14. Samhouri D, Ijaz K, Rashidian A, Chungong S, Flahault A, Babich SM, Mahjour J. Analysis of Joint External Evaluations in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(5):477‒487. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.5.477.

15. Rashidian A, Mandil A, Mahjour J. Improving evidence informed policy-making for health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2017:23(12):793‒794. doi:10.26719/2017.23.10.793.

852

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

Role of climatic factors in the incidence of dengue in Port Sudan City, SudanElsiddig Noureldin 1 and Lynn Shaffer 2

1National Center for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC), Ministry of Health, Jazan, Saudi Arabia (Correspondence to: Elsiddig Noureldin: [email protected]). 2Trinity Health System, Mount Carmel Health System, Columbus, United States of America

AbstractBackground: Dengue fever outbreaks have occurred in Port Sudan City, Sudan, during the last 2 decades. Climatic factors may play a role in dengue incidence.Aims: This study aimed at discribing the relationship between climatic factors and dengue fever incidence in Port Sudan during 2008–2013.Methods: This ecological study entailed secondary data analysis of dengue fever cases and climate information to explore which climatic factors predict the incidence of dengue fever. The Wilcoxon rank sum test and multiple linear regression examined the association between number of dengue fever cases and climatic factors during lag times of 1–6 months. Results: Relative humidity and maximum and minimum temperatures were correlated with dengue incidence in Port Sudan at different time intervals during 2008–2010. Precipitation and relative humidity were correlated with dengue fever during 2011–2013. However, 3–5-month lagged relative humidity was the strongest explanatory variable for the incidence of dengue.Conclusion: Dengue transmission appears sensitive to climatic variability. Elucidating the role of climatic factors in dengue fever helps in risk assessment and prevention of epidemics.Keywords: dengue, infection control, incidence, climate, Port SudanCitation: Noureldin El; Shaffer L. Role of climatic factors in the incidence of dengue in Port Sudan City, Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(12):852–860. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.19.019Received: 29/08/17; accepted: 12/02/18Copyright © World Health Organization (WHO) 2019. Some rights reserved. This work is available under the CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

IntroductionDengue is a viral disease transmitted to humans by the bite of infected females of the main mosquito vector Ae-des aegypti and to a lesser extent Aedes albopictus (1). Tradi-tionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) has clas-sified dengue into three categories according to severity: dengue fever, dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome (2). The clinical characteristics of den-gue are sudden onset of severe fever, pain behind the eyes (retro-orbital), nausea, swollen lymph nodes (lym-phadenopathy), intense headache, muscle pain (myalgia), gastrointestinal problems, joint pain and rash (3). Dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome cause lethal complications that include severe haemorrhage, plasma leakage, organ impairment, fluid accumulation, and respiratory distress (3).

Dengue fever is considered by WHO to be the most important mosquito-borne viral disease. Dengue incidence has increased > 10-fold throughout the last 3 decades, with a currently estimated 50–100 million annual cases distributed over > 100 countries. WHO has advocated the development of preventive and proactive measures to limit dengue transmission and outbreaks (4).

Previous investigators have examined factors that affect populations of Ae. aegypti and subsequent dengue fever incidence. Unplanned urbanization and climatic factors, including high temperatures and rainfall, might

contribute to epidemics of dengue (5,6). Aedes mosquitoes are found in urban settings, especially in tropical areas, where they maintain a sustainable relationship with humans, which has led to re-emergence of dengue virus infections (7). Climatic factors of temperature, rainfall and humidity are thought to have the most potential to affect the maturation periods, habitats, survival time and vectorial capacity of Aedes mosquitoes (8). Researchers from various geographic areas have reported significant associations between temperature, relative humidity, precipitation and dengue distribution and transmission, e.g., India (9), Thailand (10), Malaysia (11), Viet Nam (12), Philippines (13), Indonesia (14), and Singapore (15). For example, Karim et al. (16) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, found positive significant correlations between the 2-month-lagged relative humidity, rainfall, maximum temperature, and the reported monthly dengue cases. Other researchers reported no effect of climatic factors on the incidence of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever (15,17). Also, in Central Visayas, Philippines, Picardal and Elnar (18) found no correlation between dengue cases and rainfall or temperature. Given these variable findings, it is possible that the effects of climatic factors such as precipitation, temperature and relative humidity may depend on the normal conditions of a particular geographic area.

In the last 2 decades, Port Sudan City has witnessed several dengue outbreaks, and the incidence of dengue

853

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

was estimated as 94 cases per 10 000 during the 2010 outbreak in which 3765 cases were reported (19,20). There have been no ecological investigations of the role of climatic factors on the incidence of dengue fever in Sudan, particularly in Port Sudan, where most of the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever in the country has occurred. Since climatic factors are thought to affect the population of Ae. aegypti and dengue fever incidence, this information could be helpful in planning for public health preventive and control measures in this region.

The present study aimed to describe the temporal relationship between climatic factors (maximum and minimum temperatures, relative humidity or rainfall) and the incidence of dengue fever in Port Sudan City, Sudan, during 2008–2013.

MethodsStudy design and settingThis study was an ecological analysis of the association between climatic factors and dengue fever incidence in Port Sudan City, Sudan, for the period 2008–2013. Port Sudan is located on the Red Sea and has an arid (low precipitation) and humid (Mediterranean) climate. The mean maximum temperature is around 40°C in summer (June–September) and the mean minimum temperature is 20.5°C in winter (November–March). Total annual pre-cipitation is 76.1 mm in the rainy season (October–Jan-uary), and the annual average relative humidity is 63% (19,21).

Sampling frameThe sampling frame was the monthly secondary data (datasets) of the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fe-ver cases and the climatic information from 2008 to 2013. The time period 2008–2013 was chosen because it con-tained complete information on dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases. The sampling frame included the monthly number of dengue fever/dengue haemor-rhagic fever cases, relative humidity, temperature (max-imum and minimum), and rainfall (precipitation). The data of weekly dengue cases were obtained from the De-partment of Epidemiology, Ministry of Health, Red Sea State, Sudan. All dengue fever cases are required to be re-ported to the health authorities in Port Sudan, namely the Department of Epidemiology, and all suspected cases are sent to local laboratories for confirmation of dengue in-fection. Laboratory tests that are dengue positive are sent to the National Public Health Laboratory in Khartoum for confirmation. The data were captured in an electron-ic dataset. The climatic variables were obtained from the Sudan Meteorological Authority, which collects data on temperature, relative humidity and rainfall in real time through its widely distributed sentinel meteorological stations including one in Port Sudan.

Data analysisIt was noted from the preliminary graphic analysis that the number of dengue cases was higher during 2008

through to most of 2010 and then declined significantly in 2011–2013. The reason behind that was the strong epi-demiological and entomological surveillance and control measures undertaken by the Ministry of Health, Red Sea State to deal with the outbreak that started in June 2010 and continues to the present (Department of Epidemiolo-gy, Red Sea State, personal communication, 2014). There-fore, for the purposes of analysis the study period was split into 2008–2010 and 2011–2013.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were utilized to examine the association between number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases and the following factors: minimum temperature, maximum temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall for 1–6 months’ lag time, according to cutoff values for the climatic factors that were identified from preliminary graphic analysis, which indicated threshold relationships between the climatic factors and dengue fever incidence, rather than dose–response relationships. Lag time indicated the number of months between the time when dengue fever cases were reported and the pattern of the climatic factor of interest. The unit of time was months, as weather data were available only in monthly units. Multiple linear regression was used to determine which independent variables still influenced the monthly number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases during lag time of 1–6 months after taking into account the other climatic factors. SPSS version 20 was used for statistical analysis.

ResultsFigures 1–4 illustrate the relationships between precip-itation, relative humidity and maximum and minimum temperature and the number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases for 2008–2010 and 2011–2013. For each climatic factor, the histogram bars show the me-dian number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fe-ver cases according to whether the monthly average fac-tor was above or below the threshold value derived from graphical analysis (vertical axis), and the time lag for that particular climatic factor (horizontal axis). The number on the horizontal axis represents the number of months between the measurement of the climatic factor and the reporting of the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases, with negative numbers to indicate that the climatic measurement took place prior to the occurrence of the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases. It should be noted that although the shape of the trends for Figures 1–4 are similar for the two time periods, the total number of cases was smaller during 2011–2013.

Precipitation Although there were some differences in the number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases accord-ing to whether there was any rainfall 4–6 months prior to the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever reporting month, precipitation was not correlated with dengue inci-dence during any of the 6 months lag time during 2008–2010 (all P > 0.05, Figure 1). Nevertheless, the incidence of dengue cases at average precipitation > 0 exceeded that of

854

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

dengue incidence when there was no recorded precipita-tion in all months except 0 and 1 month prior to the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever reporting month during 2008–2010 (Figure 1). In contrast, for 2011–2013, although the total number of dengue fever cases was lower, the oc-currence of any precipitation during 5 or 6 months prior to the dengue fever reporting month was associated with a significantly elevated number of cases (P = 0.0433 and 0.0298, respectively). The shape of this trend is similar to that observed for the time period 2008–2010 in that the dif-ference in number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases between conditions of no precipitation versus at least some precipitation was most extreme at 4, 5 and 6 months prior to the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever reporting period.

Relative humidity For 2008–2010, relative humidity started to show a positive association with dengue fever/den-gue haemorrhagic fever at the 3-month lag time (P = 0.0025) and continued at 4 months (P = 0.0003) and 5 months (P = 0.0037) (Figure 2). The highest occurrence of average (rather than median) number of dengue cases cor-related with high relative humidity at the 3-month (246.4), 4-month (253.8) and 5-month (226.4) lag times. Relative hu-midity < 56% compared to ≥ 56% during 3–5 months prior to the dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever reporting month produced the largest difference between numbers of cases during 2008–2010. For 2011–2013, relative humid-

ity ≥ 56% was significantly associated with an increased number of dengue fever cases only at 3 months prior to the reporting of those cases, with 21.8 average (rather than median) monthly reported dengue cases compared to 6.2 cases when relative humidity was < 56% (P = 0.0202).

Maximum temperatureIn 2008–2010, maximum temperature was significantly correlated with dengue at the 2-, 3- and 4-month lag times (P = 0.0196, 0.0027 and 0.0365, respectively. (Figure 3). It appeared that average maximum temperature < 35°C fa-voured high incidence of dengue, with average (rather than median) numbers of dengue fever/dengue haemor-rhagic fever cases of 220.8, 217.4 and 186.2, respectively, compared to only 26.5, 18.7 and 49.1 when the average max-imum temperature was ≥ 35°C. No significant trends were seen with respect to maximum temperature for 2011–2013 (all P > 0.05).

Minimum temperature The minimum temperature was significantly correlat-ed with dengue at the 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-month lag times (P = 0.0427, 0.0012, 0.0024 and 0.0215, respectively) during 2008–2010 (Figure 4). The incidence of dengue was signif-icantly increased when the minimum temperature was < 25°C compared to ≥ 25°C. No significant trends were seen with respect to minimum temperature for 2011–2013 (all P > 0.05).

Figure 1 Number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases according to the occurrence of precipitation and number of months prior to reporting

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2008-2010 2011-2013

No. momths prior to month DF/DHF cases reported

Med

an n

o. D

F/D

HF

case

s

No precipitation Precipitation

0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6

855

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

Association of climatic factors with dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever incidenceMultiple linear regression modelling was done to de-termine whether all of the climatic factors individually associated with an increase in dengue fever cases re-mained independently associated after other climatic factors were taken into account. The final regression model is displayed in Table 1. Only relative humidity < 56% versus ≥ 56% at 3, 4 and 5 months prior to the dengue fever reporting month remained independently associat-ed with the number of dengue fever cases reported. The interaction term in the model indicates that this effect of relative humidity was greater during 2008–2011 than 2011–2013. The results also indicate that the other climat-ic factors do not have any significant relationship with dengue fever cases after controlling for relative humidi-ty. In other words, the minimum temperature, maximum temperature and precipitation were strongly correlated with relative humidity, and once we took into account relative humidity, they did not add any information for predicting the number of dengue fever cases.

DiscussionOverall, this study suggested that relative humidity ≥ 56% was strongly and independently associated with an increased number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases 3–5 months later. The lower number of cases reported during 2011–2013 also suggested that the control measures put in place in 2010 by the Ministry of Health, Red Sea State, were effective. Precipitation in 2008–2010 showed no significant association with dengue inci-dence, probably because most of the breeding sites were available indoors for Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, and this vec-tor was therefore dependent on the behaviour of humans rather than precipitation for their survival and develop-ment (22,23). In Philippines, Singapore and Indonesia, outbreaks of dengue have occurred even in dry seasons, possibly due to practices of water storage (24). This may partly explain the weak impact of precipitation compared to other climatic factors on the dengue cases. However, the relationship between precipitation and Ae. aegypti population is complex (25).

We showed that precipitation at 5 and 6 months’ time lag was positively correlated with

Figure 2 Number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases according to relative humidity and number of months prior to reporting

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

2008-2010 2011-2013

No. momths prior to month DF/DHF cases reported

Med

an n

o. D

F/D

HF

case

s

Relative humidity <56% Relative humidity ≥56%

0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6

Table 1 Linear regression describing relationship between relative humidity and monthly frequency of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases, 2008–2013Model factors Estimated

coefficientStandard error P

Relative humidity < 56% vs. ≥ 56% at 3, 4 and 5 months2008–2010 vs. 2011–2013Interaction term

222.3238.34

−108.63

51.4359.8232.0

0.00010.52370.0012

856

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

dengue cases in 2011–2013. This is in line with the findings of Hii et al. (26), who found a linear increase in dengue cases in Singapore at a time lag of 5–20 weeks after elevated precipitation. Vu et al. (12) reported 0–3 months’ time lag after precipitation and before the incidence of dengue, while Rubio-Palis et al. (17) identified 4 months as the critical time point. Furthermore, it has been found that the abundance of A. aegypti adults and larvae in Port Sudan is directly proportional to relative humidity and precipitation (27).

Relative humidity ≥ 56% was significantly associated with dengue cases at 3–5 months’ lag time in 2008–2010, and at 3 months’ lag time in 2011–2013. Corroborating results have been reported by Ahmed (27), who found that the population density of Ae. aegypti larvae in Jeddah was large at 55.4% relative humidity and small at 45.4%. Banu et al. (28) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, also revealed that relative humidity was positively correlated with dengue incidence at a 4-month lag time. Relative humidity is “the amount of atmospheric moisture present relative to the amount that would be present if the air were saturated” (http://graphical.weather.gov/definitions/defineRH.html) and is a function of temperature: relative humidity increases as temperature decreases. As relative humidity has its effects on all stages of the mosquito life cycle, its combined impact with temperature significantly affects the survival rate of the mosquito, number of blood meals, and eventually its capacity to become infected and transmit dengue (29).

In our study, maximum temperature < 35°C in 2008–2010 was positively associated with dengue incidence at lag time of 2–4 months before the incidence of dengue.

This is in accordance with the work of Depradine and Lovell (30), who found a 4-month time lag between maximum temperature and dengue incidence. Moreover, the present study revealed that average maximum temperature < 35°C favoured high incidence of dengue in Port Sudan. Similar results of an association between temperature > 26°C and dengue risk have been reported (26).

Minimum temperature was significantly correlated with dengue at 1–4 months’ lag time in 2008–2010. Several researchers found a similar association with slight differences. For example, Depradine and Lovell (30) reported a 3-month lag time between minimum temperature and dengue incidence, and Gomes et al. (31) reported a 1-month lag. Honório et al. (32) found a positive effect of air temperature of 22–24°C on the development of A. aegypti but no effect was evident above 24°C in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The general trends in our study seem to be that higher relative humidity at 3–5 months prior to the reporting month for dengue fever, and then lower or more moderate minimum and maximum temperatures 2–4 months before are related to large increases in the number of dengue fever cases. This is in line with the findings of Chen et al. (33), who suggested that warmer temperature at 3-months’ lag, and high humidity with high mosquito population increased the rate of transmission of dengue fever in Southern Taiwan.

Although our multiple linear regression showed that the primary factor involved with dengue fever

Figure 3 Number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases according to maximum temperature and number of months prior to reporting

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2008-2010 2011-2013

No. momths prior to month DF/DHF cases reported

Med

an n

o. D

F/D

HF

case

s

Tmax <35° Tmax ≥35°

0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6

857

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

Figure 4 Number of dengue fever/dengue haemorrhagic fever cases according to minimum temperature and number of months prior to reporting

incidence was relative humidity, it seems that relative humidity is closely linked to moderate temperatures. Moderate temperatures allow for higher relative humidity and thus optimum conditions for Ae. aegypti to reproduce. Valsson and Bharat (34) argued that there is a negative correlation between temperature and relative humidity. Therefore, the relationship between relative humidity and minimum/maximum temperatures is not necessarily one of confounding, but that minimum/maximum temperatures are precursors to, or preservers of, the level of relative humidity.

The time lag seems to suggest that it takes a few months of favourable climatic conditions to build up a large enough mosquito population that a sufficient number of people would be exposed to dengue virus. This could happen through the effect of these climatic factors on the life cycle of the dengue virus and its vector. Climatic factors influence all the developmental stages of the mosquito until it becomes an adult, then they affect virus replication and its incubation period inside the mosquito (the extrinsic incubation period) and humans (intrinsic incubation period). The latter might culminate in dengue outbreaks that may in turn be represented by a cumulative time lag (29,35).

The lag between climatic factors data and dengue incidence data differs depending on the corresponding lag between mosquito life stage and the expression of clinical symptoms. In the case of minimum temperature, this lag is expected to be shorter because minimum

temperature is often associated with mortality in adult mosquitoes, and longer in case of high relative humidity, which influences the hatching and survival of adult mosquitoes. Mean temperature is usually associated with all biological cycles of the vector Ae. aegypti, which take more time to affect the incidence of dengue (35).

These patterns were observed in the present study.The present study had some limitations. The cutoffs

used for some of the analyses were based on visual inspection of the scatterplots. It would be beneficial to assess whether the findings of the present study could be replicated in another dataset based on a climate similar to that of Port Sudan City. In most low-income countries, dengue cases are often under- or over-reported. Moreover, those reported dengue cases might be affected by documentation of subclinical cases, public health systems availability, and case definition. Based on this, the aforementioned factors should be considered prior to identifying any associations between dengue transmission and climatic factors. Finally, this ecological analysis did not consider socioeconomic or other factors that may influence DF incidence; therefore, this study could not examine their role relative to that of climatic factors.

ConclusionAmong other factors, dengue transmission in Port Sudan appears sensitive to variability in climate. Other factors

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

2008-2010 2011-2013

No. momths prior to month DF/DHF cases reported

Med

an n

o. D

F/D

HF

case

s

Tmin <25° Tmin ≥25°

0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6

858

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

Rôle des facteurs climatiques dans l'incidence de la dengue dans la ville de Port Soudan, SoudanRésuméContexte : Des flambées de dengue sont survenues dans la ville de Port Soudan (Soudan) au cours des deux dernières décennies. Les facteurs climatiques peuvent jouer un rôle dans l'incidence de cette maladie.Objectif : La présente étude avait pour objectif de décrire la relation entre les facteurs climatiques et l'incidence de la dengue à Port Soudan au cours de la période 2008-2013.Méthodes : La présente étude écologique comprenait l'analyse de données secondaires sur les cas de dengue et des informations climatiques afin d'étudier les facteurs climatiques qui permettent de prévoir l'incidence de la dengue. Le test de la somme des rangs de Wilcoxon et la régression linéaire multiple ont permis d’examiner l'association entre le nombre de cas de dengue et les facteurs climatiques pendant des périodes de 1 à 6 mois. Résultats : L'humidité relative et les températures maximales et minimales ont été corrélées avec l'incidence de la dengue à Port Soudan à différents intervalles de temps au cours de la période 2008-2010. Les précipitations et l'humidité relative ont été corrélées avec la dengue au cours de la période 2011-2013. Cependant, l’effet différé de l'humidité relative 3 à 5 mois plus tard était la variable explicative la plus forte pour l'incidence de la dengue.Conclusion : La transmission de la dengue semble sensible à la variabilité climatique. L'élucidation du rôle des facteurs climatiques dans la dengue contribue à l'évaluation des risques et à la prévention des épidémies.

دور العوامل املناخية يف اإلصابة بحمى الضنك يف مدينة بورتسودان يف السودانالصديق نور الدين، لني شافر

اخلالصةاخللفية: حدثت أوبئة محى الضنك يف مدينة بورتسودان بالسودان خالل العقدين األخريين. وربام يكون للعوامل املناخية دور يف اإلصابة بحمى

الضنك.هدفت هذه الدراسة إىل وصف العالقة بني العوامل املناخية ومعدالت اإلصابة بحمى الضنك يف مدينة بورتسودان خالل الفرتة من األهداف:

2008 إىل 2013طرق البحث: تطلبت هذه الدراسة البيئية حتليل بيانات ثانوية عن حاالت محى الضنك، ومعلومات مناخية الستكشاف العوامل املناخية التي تتنبأ باإلصابة بحمى الضنك. ونظر "اختبار ويلكوكُسن للَمْرَتبة واملجموع" واالنحدار اخلطي املتعدد يف العالقة بني عدد حاالت محى الضنك والعوامل

املناخية خالل فارق زمني يرتاوح من شهر إىل 6 أشهر. النتائج: وجد ارتباط بني الرطوبة النسبية ودرجات احلرارة القصوى والدنيا من جهة، ومعدالت اإلصابة بحمى الضنك يف بورتسودان من جهة أخرى يف فرتات زمنية خمتلفة خالل الفرتة من 2008 إىل 2010. كام وجد ارتباط بني هطول األمطار والرطوبة النسبية من جهة واإلصابة بحمى الضنك من جهة أخرى خالل الفرتة من 2011 إىل 2013. ومع ذلك، كانت الرطوبة النسبية املتأخرة ملدة ترتاوح من 3 إىل 5 أشهر أقوى متغري

تفسريي ملعدالت اإلصابة بحمى الضنك.تقدير الضنك عىل املناخية يف اإلصابة بحمى العوامل دور توضيح املناخ. ويساعد بتقلب يتأثر الضنك انتقال عدوى محى أن يبدو االستنتاج:

املخاطر والوقاية من األوبئة.

may include, but are not limited to, human population level, mobility, socioeconomic status, population’s im-mune status, and human–mosquito interaction. Increas-ing urbanization around Port Sudan has led to a rise in population. This suggests continued likelihood of den-gue fever outbreaks and the need to develop prevention and control mechanisms. As a port, dengue outbreaks in Port Sudan may represent dangers to surrounding cities, or of transporting dengue to other locations via ships. It is important to elucidate the role of climatic factors in dengue transmission because it helps in risk assessment of epidemics and facilitates preventive actions. This is especially relevant given that time lags of 2–5 months were identified, which allows for adequate planning. Fu-ture studies should integrate the analysis of climatic and

nonclimatic factors that maintain a sustainable viral cir-culation, such as human population size, human renewal rate, household infestation, and ratio of mosquito vectors per person.

The results of this study should help to strengthen dengue surveillance and control programs in Port Sudan City, and to establish climate-based outbreak alert and early warning systems for dengue in the city and Sudan as a whole. Health authorities can synchronize efforts across meteorological departments, research institutions, and national surveillance systems to develop and integrate a climate-based dengue forecasting system.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

859

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

References1. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control: new edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009

(WHO/HTM/NTD/DEN/2009.1; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44188/9789241547871_eng.pdf;jsession-id=9D1A2B484148F3953ED915F732DC598C?sequence=1, accessed 16 April 2019).

2. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2nd edition. Geneva: World health Organization; 1997 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/41988/9241545003_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, accessed 16 April 2019).

3. Dengue [website]. World Health Organization (http://apps.who.int/tdr/svc/diseases/dengue, accessed 16 April 2019).

4. Report of a WHO technical working group meeting on dengue prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012 (http://www.who.int/denguecontrol/Summary_Technical_working_group_meeting.pdf?ua=1 2012, accessed 16 April 2019).

5. Crowell G, Cazelles B, Broutin H, Munayco CV. The influence of geographic and climate factors on the timing of dengue epi-demics in Peru, 1994–2008. BMC Infect Dis. 2011 Jun 8;11:164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-164 PMID:21651779

6. Banu S, Hu W, Hurst C, Tong S. Dengue transmission in the Asia–Pacific region: impact of climate change and socio-environ-mental factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2011 May;16(5):598–607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02734 PMID:21320241

7. Su GL. Correlation of climatic factors and dengue incidence in Metro Manila, Philippines. Ambio. 2008 Jun;37(4):292–294. PMID:18686509

8. Wu PC, Lay JG, Guo HR, Lin CY, Lung SC, Su HJ. Higher temperature and urbanization affect the spatial patterns of dengue fever transmission in subtropical Taiwan. Sci Total Environ. 2009 Mar 15;407(7):2224–2233.

9. Sankari T, Hoti SL, Bhubonchandra Singh Th, Shanmugavel J. Outbreak of dengue virus serotype-2 (DENV-2) of Cambodian origin in Manipur, India – association with meteorological factors. Ind J Med Res. 2012 Oct;136(4):649–665. PMID:23168706

10. Promprou S, Jaroensutasinee M, Jaroensutasinee K. Climatic factors affecting dengue haemorrhagic fever incidence in Southern Thailand. Dengue Bull. 2005 Dec;29:41–48.

11. 11. Nazri CD, Abu Hassan A, Abd Latif Z, Rodziah I. Impact of climate and land use variability based on dengue epidemic outbreak in Subang Jaya. In: Proceedings of Humanities, Science and Engineering (CHUSER), 2011 IEEE Colloquium, Penang, Malaysia, 5–6 December, 2011.

12. Vu HH, Okumura J, Hashizume M, Tran DN, Yamamoto T. Regional differences in the growing incidence of dengue fever in Vietnam explained by weather variability. Trop Med Health. 2014 Mar;42(1):25–33. http://dx.doi,org/10.2149/tmh.2013-24 PMID:24808744

13. Opena ELL, Teves FG. Climate and the incidence of dengue fevers in Iligan City, the Philippines. Asia–Pacific J Soc Sci. 2011(Spe-cial Issue):114–131.

14. Zulfaidah PG, Nobukazu N. Climatic variability and dengue hemorrhagic fever incidence in Nganjuk district, East Java Indone-sia. Acta Biologica Malaysiana. 2013;2:31–39.

15. Wang ZC, Hoong MH, Martin LL, Gary KK. Delayed effects of climate variables on incidence of dengue in Singapore during 2000–2010. APCBEE Procedia 2012;1:22–26.

16. Karim MN, Munshi SU, Anwar N, Alam MS. Climatic factors influencing dengue cases in Dhaka city: A model for dengue pre-diction. Indian J Med Res. 2012 Jul;136(1):32–39. PMID:22885261

17. Rubio-Palis Y, Pérez-Ybarra LM, Infante-Ruíz M, Comach G, Urdaneta-Márquez L. Influence of climatic variables on dengue cases and abundance of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Maracay, Venezuela. Boletín de Malariología y Salud Ambiental. 2011 Dec;51(2):145–157.

18. Picardal JP, Elnar AR. Rainfall, temperature and the incidence of dengue in Central Visayas, Philippines are not correlated. CNU J Higher Educ. 2012;661–70.

19. Seidahmed OME, Hassan SA, Soghaier MA, Siam HAM, Ahmed FTA, Elkarsany MM et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of den-gue transmission along a Red Sea coastline: a longitudinal entomological and serological survey in Port Sudan City. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012; 6(9):e1821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001821 PMID:23029582

20. Seidahmed OME, Siam HAM, Soghaier MA, Abubakr M, Osman HA, Abd Elrhman LS, et al. Dengue vector control and surveillance during a major outbreak in a coastal Red Sea area in Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2012 Dec;18(12):1217–1224. PMID:23301396

21. Sudan [website] World Meteorological Organization (http://www.worldweather.org/085/c01535.htm, accessed 16 April 2019).

22. Saifur RGM, Dieng H, Hassan AA, Salmah MRC, Satho T, Miake F, et al. Changing domesticity of Aedes aegypti in Northern Peninsular Malaysia: reproductive consequences and potential epidemiological implications. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030919 PMID:22363516

23. Moore CG, Cline BL, Ruiz-Tiben E, Lee D, Romney-Joseph H, Rivera-Correa E. Aedes aegypti in Puerto Rico: environmental determinants of larval abundance and relation to dengue virus transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978 Nov; 27(6):1225–1231. PMID:727328

24. Aiken SR, Frost DB, Leigh CH. Dengue hemorrhagic fever and rainfall in Peninsular Malaysia: some suggested relationships. Soc

860

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

Sci Med D Med Geog. 1980 Sep;14(3):307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-8002(80)90043-X

25. Gage KL, Burkot TR, Eisen RJ, Hayes EB. Climate and vector-borne diseases. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Nov; 35(5):436–450. PMID: 18929970.

26. Hii YL, Rocklöv J, Nawi Ng, Tang CS, Pang FY, Sauerborn R. Climate variability and increase in intensity and magnitude of dengue incidence in Singapore. Glob Health Action. 2009 Nov 11;2 http://dx.doi.org/0.3402/gha.v2i0.2036 PMID:20052380

27. Ahmed YE. The effect of climatic factors on abundance of Aedes aegypti L. and transmission of dengue fever in Port Sudan (Sudan) and Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) [thesis]. University of Khartoum; 2014.

28. Banu S, Hu W, Hurst C, Tong S. Dengue transmission in the Asia–Pacific region: impact of climate change and socio-environ-mental factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2011 May;16(5):598–607. http://dx.doi,org/10.1111/j. 2011; 1365-3156.2011.02734 PMID:21320241

29. McMichael A, Haines A, Slooff R, Kovats R. Climate change and human health: an assessment by a task group on behalf of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization, World Meteorological Association, United Nations Environ-ment Programme; 1996 (http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/62989, accessed 16 April 2019).

30. Depradine C, Lovell E. Climatological variables and the incidence of Dengue fever in Barbados. Int J Environ Health Res. 2004 Dec;14(6):429–441. PMID:15545038

31. Gomes AF, Nobre AA, Cruz OG. Temporal analysis of the relationship between dengue and meteorological variables in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2001–2009. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012 Nov;28(11):2189–97. PMID:23147960

32. Honório NA, Codeço CT, Alves FC, Magalhães M. Temporal distribution of Aedes aegypti in different districts of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, measured by two types of traps. J Med Entomol. 2009 Sep;46(5):1001–14.

33. Chen SC, Liao CM, Chio CP, Chou HH, You SH, Cheng YH. Lagged temperature effect with mosquito transmission potential ex-plains dengue variability in Southern Taiwan: insights from a statistical analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2010 Sep 1;408(19):4069–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.05.021 PMID:20542536

34. Valsson S, Bharat A. Impact of air temperature on relative humidity – a study. Architecture Time Space People. 2011 Feb;38–41.

35. Gharbi M, Quenel P, Gustave J, Cassadou S, La Ruche G, Girdary L, et al. Time series analysis of dengue incidence in Guade-loupe, French West Indies: forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. BMC Infect Dis. 2011 Jun 9;11:166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-166 PMID:21658238

861

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

Coût hospitalier des pathologies invasives à pneumocoque chez les enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans en TunisieArwa Ben Salah,1,2 Sana El Mhamdi,1,2 Manel Ben Fredj,1 Chebil Ben Meriem,2,3 Jihen Bouguila,4 Khaled Ben Helel,5 Lamia Sfaihi,6 Rafiaa Mustapha,7 Mohamed Sfar 8 et Mohamed Soltani 1,2

1Service de Médecine préventive et d’Épidémiologie, Centre hospitalier universitaire (CHU), Monastir (Tunisie). 2Laboratoire de recherche, Épidémiologie appliquée à la santé de la mère et de l’enfant, CHU Monastir, Tunisie. 3Service de Pédiatrie, CHU, Monastir, Tunisie. 4Service de Pédiatrie, CHU Farhat Hached, Sousse, Tunisie. 5Service de Pédiatrie, CHU, Kairouan, Tunisie. 6Service de Pédiatrie, CHU Sfax, Tunisie. 7Service de Pédiatrie, Hôpital régional de Nabeul, Tunisie. 8Service de Pédiatrie, CHU, Mahdia, Tunisie. (Correspondance à Arwa Ben Salah à : [email protected] ).

RésuméContexte : Les infections à pneumocoque sont une cause importante de morbidité et de mortalité dans le monde et en Tunisie. Des données sur le fardeau économique de ces infections sont nécessaires pour éclairer la décision d'inclure le vaccin antipneumococcique dans la vaccination systématique des enfants. Objectifs : La présente étude visait à estimer le coût médical des hospitalisations causées par une pneumococcie invasive (pneumonie et méningite) chez les enfants de moins de 15 ans en Tunisie.Méthode : Une étude prospective multicentrique a été menée dans 15 services de pédiatrie, dans différentes zones socio-économiques de la Tunisie, de juin 2014 à mai 2015. Tous les enfants de moins de 15 ans hospitalisés pour une pneumonie à pneumocoque ou une méningite bactérienne confirmée ont été inclus. Un formulaire de rapport de cas a été rempli pour chaque cas éligible. La méthode des coûts à base d'activités (méthode ABC) a été utilisée pour estimer le coût hospitalier. La saisie des données et l'analyse statistique ont été effectuées à l'aide du logiciel SPSS 20.0.Résultats : Au cours de la période de l'étude, 727 enfants ont été hospitalisés pour une pneumonie à pneumocoque et 60 autres pour une méningite bactérienne, dont 21 (35 %) avaient une méningite à pneumocoque confirmée. Le coût hospitalier médian pour la pneumonie à pneumocoque était de TND 353, 910 et de TND 1680, 632 pour la méningite à pneumocoque. Par extrapolation globale des données, nous avons estimé que près de 1091 hospitalisations pour pneumonie à pneumocoque et 69 hospitalisations pour méningite à pneumocoque surviennent chaque année chez des enfants tunisiens de moins de 15 ans, pour un coût total de TND 502 079, 408.Conclusion : Le fardeau économique des infections à pneumocoque semble être important en Tunisie. Les coûts estimés ne reflètent pas les coûts réels de cette infection. Des études sur le rapport coût-efficacité seraient utiles pour aider les responsables de l'élaboration des politiques à prendre les décisions nécessaires.Mots clés : Pneumonie à pneumocoque ; méningite à pneumocoque ; coût hospitalier ; TunisieCitation : Ben Salah A; El Mhamdi S; Ben Fredj M; Ben Meriem C; Bouguila J; Ben Helel K; et al. Coût hospitalier des pathologies invasives à pneumocoque chez les enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans en Tunisie. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;25(12):861-871. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.19.036Reçu : 22/12/16 ; accepté : 27/03/18© Organisation mondiale de la Santé 2019. Certains droits réservés. La présente publication est disponible sous la licence Creative Commons Attribution–Pas d’utilisation commerciale – Partage dans les mêmes conditions 3.0 IGO (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ; (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

IntroductionLe pneumocoque constitue l’un des principaux germes responsables de pneumonie, de méningite et de septicémie chez les enfants (1). Les infections causées par le pneumocoque Streptococcus pneumoniae constituent une cause importante de morbidité et de mortalité partout dans le monde. Chaque année, 826 000 enfants âgés de moins de cinq ans décèdent suite à une infection par le pneumocoque, ce qui correspond à 11 % de tous les décès dans ce groupe d’âge (1). Les progrès réalisés en matière de réanimation et de prise en charge diagnostique et thérapeutique ont certes contribué à la réduction de cette mortalité mais ceci aux dépens d’une charge morbide plus importante, et par conséquent d’un coût plus élevé.

Dans sa note de synthèse de 2012, l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS) a recommandé l’introduction des vaccins antipneumococciques conjugués dans les programmes nationaux de vaccination des différents pays du monde (2). Deux vaccins conjugués (10-valent

et 13-valent), ayant démontré leur innocuité et efficacité (3–8), sont actuellement disponibles et utilisés dans plus de 100 pays dans le monde entier, dont des pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire (9). En outre, ces vaccins peuvent être facilement intégrés dans le Programme élargi de vaccination et co-administrés avec d’autres vaccins sans aucun risque d’interaction (2). Toutefois, le processus décisionnel doit se baser sur des données locales et des estimations objectives de la charge morbide et du coût de prise en charge des infections causées par le pneumocoque.

En Tunisie, les données disponibles montrent que ces infections constituent un problème réel de santé publique (10). En effet, l’étude réalisée par Khalifa et al. au Centre hospitalier universitaire (CHU) de Monastir en Tunisie a montré que S. pneumoniae était le germe le plus retrouvé dans les méningites des individus âgés de cinq ans et plus (11). De même, une étude communautaire réalisée par Maalej et al. a montré que S. pneumoniae

862

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article

occupait la deuxième position dans les méningites du nourrisson et du petit enfant et la première position dans les méningites de l’enfant de plus de cinq ans (12). La même étude a montré que ce germe se caractérisait par des taux importants de résistance à la pénicilline. Cependant, l’ampleur de ce problème et de sa charge réelle sur le plan des dépenses de santé n’a pas été précisée, d’où l’intérêt de la présente étude.

L’objectif de cette étude était d’estimer le coût hospitalier des méningites et des pneumonies à pneumocoque chez les enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans en Tunisie.

MéthodesType, lieu et population d’étude Il s’agit d’une étude longitudinale prospective multicentrique réalisée entre le 1er juin 2014 et le 31 mai 2015 dans 15 services de pédiatrie, au niveau de huit centres hospitalo-universitaires et trois hôpitaux régionaux, répartis dans différentes régions socio-économiques du pays : district de Tunis (trois sites), régions du nord-ouest (deux sites), du nord-est (trois sites), du centre-est (trois sites), du centre-ouest (un site), du sud-ouest (un site) et du sud-est (trois sites).

Notre population d’étude était constituée de l’ensemble des enfants âgés de moins de 15 ans, hospitalisés dans l’un des sites de l’étude pour pneumonie ou pleuropneumonie à pneumocoque ou méningite bactérienne. Dans cette étude, nous avons exclu les otites à pneumocoque étant donné qu’elles sont souvent traitées en ambulatoire. Nous avons également exclu les septicémies à pneumocoque en raison de la difficulté d’obtention d’une confirmation bactériologique.

Le diagnostic de pneumonie ou pleuropneumonie à pneumocoque était basé sur un ensemble de critères cliniques (fièvre, toux, douleur thoracique, dyspnée, râles crépitants localisés, souffle tubaire, etc.), radiologiques (opacité systématisée pouvant être associée à un épanchement pleural, ou pleurésie sans foyer de pneumonie) et biologiques (hyperleucocytose à polynucléose, CRP [C-reactive protein ‒ protéine C réactive] supérieure à 20 mg/L et isolement de S. pneumoniae à l’hémoculture ou à la culture du liquide pleural). C’est ce dernier critère bactériologique qui permet de confirmer le diagnostic. Toutefois, étant donné que le germe n’est isolé par hémoculture que dans moins de 8 % des cas (13), nous avons inclus dans cette étude les cas « probables », définis comme étant toutes les situations répondant aux critères cliniques, radiologiques et biologiques sans confirmation bactériologique avec une évolution favorable du patient sous antibiothérapie visant S. pneumoniae.

Le diagnostic de méningite bactérienne repose aussi sur un ensemble de critères cliniques (apparition soudaine de fièvre, refus de téter, vomissements, troubles de la conscience, convulsions, hypotonie, fontanelle bombée, céphalée, raideur de la nuque, etc.), de critères biologiques (examen cytobactériologique du

liquide céphalo-rachidien : protéinorachie supérieure à 100 mg/dL, glucorachie inférieure à 50 % de la glycémie, pléiocytose à prédominance neutrophile, et identification du germe par examen direct et/ou culture et/ou recherche d’antigène [Ag] soluble). La confirmation du diagnostic se fait grâce au dernier critère biologique (identification du germe). Ainsi, le cas de méningite est classé en méningite bactérienne à pneumocoque confirmée, méningite bactérienne confirmée à d’autres germes ou méningite bactérienne à germe non identifié. Ce dernier groupe correspond aux cas probables de méningites bactériennes devant les signes cliniques évocateurs et l’examen cytologique du liquide céphalo-rachidien (protéinorachie élevée avec glucorachie diminuée et pléiocytose à prédominance neutrophile) sans confirmation bactériologique par identification du germe en cause. Ils correspondent aux cas de méningites décapitées par une antibiothérapie avant la pratique de la ponction lombaire.

Il convient de noter que les enfants dont le lieu de résidence n’appartient pas aux gouvernorats de l’étude étaient exclus de l’étude. Les méningites néonatales étaient également exclues.

Déroulement de la surveillance et collecte des données Les cas éligibles de chaque site ont été repérés par un médecin coordonnateur de l’enquête (désigné par le chef du service correspondant). Les différentes données sociodémographiques (date de naissance, sexe, lieu de résidence, service d’hospitalisation), ainsi que les données cliniques, biologiques et radiologiques ont été consignées sur une fiche de renseignement spécifique pour chaque type d’infection (pneumonie ou méningite). Ces enfants ont été suivis tout au long de l’hospitalisation afin de notifier les différents soins procurés et médicaments consommés ainsi que l’évolution clinique et la durée totale de séjour.

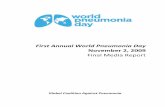

Calcul du coût Méthode de calcul Pour les besoins de cette étude, nous avons identifié la prise en charge hospitalière des méningites bactériennes et des pneumonies à pneumocoque comme un « service » fourni aux malades et ayant un coût de revient. Ce coût a été par la suite calculé selon la méthode basée sur les activités – méthode ABC (Activity Based Costing). Il s’agit d’une méthode de calcul du coût, issue du domaine industriel (14), qui repose sur une vision transversale de l’entreprise (ici l’hôpital), c’est-à-dire une vision par processus où le concept d’activité joue un rôle central. Partant du constat que ce sont les activités qui consomment les ressources, et que les produits ou services consomment des activités, la méthode ABC se propose, grâce à la description des activités qui sont effectivement réalisées, de comprendre comment les ressources sont effectivement consommées (15). Ainsi le processus de prise en charge hospitalière des méningites

863

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019

bactériennes et des pneumonies à pneumocoque consomme différentes ressources qui peuvent être regroupées en trois grandes catégories, selon les activités produites : les ressources utilisées dans les activités de diagnostic biologique et radiologique ; les ressources utilisées dans les activités de soins et de prise en charge thérapeutique ; et les ressources utilisées lors des activités d’hébergement (Figure 1).

Calcul proprement dit

· Coût des activités de diagnostic biologique et radiologique

· Pour chaque patient, nous avons listé l’ensemble des activités de prélèvement de liquide biologique, d’analyse biologique et de diagnostic radiologique.

Ces activités ont été par la suite converties, selon une pondération prédéfinie par le ministère de la Santé, en un nombre d'APB (pour les Activités de Prélèvement de liquide biologique réalisées par un infirmier), de Ke (pour les activités de prélèvement de liquide biologique réalisées par un médecin), de (pour les tests biologiques réalisés aux laboratoires de biologie) et de R (pour les examens Radiologiques réalisés au service de radiologie) (16). En l’absence de données locales spécifiques pour chaque établissement, les coûts unitaires des APB, Ke, B et R utilisés dans cette étude étaient ceux élaborés par le ministère tunisien de la Santé, selon la méthode ABC, et utilisés actuellement pour la tarification des actes de soins : B = 0,16 dinar tunisien (TND) (USD 0,08) ;

Figure 1 Processus de prise en charge d’un enfant admis pour méningite bactérienne ou pneumonie à pneumocoque

Activités d'hébergementHÔtellerie, restauration, matériel et équipement multi-usage, élecricité, etc.

« B »Activités d'analyse

biologique

« APB »« Ke »

Activités de prélèvement

de liquide biologique

« Ke »« Kc »

« VM »Activités

réalisées par un médecin

« AMI »« AMM »

Activités réalisées par un personnel paramédical

Enfa

nt e

ntra

nt p

our P

EC

Enfa

nt so

rtan

t pri

s en

char

ge

« R »Activités de diagnostic

radiologique

Ressources : électricité, réactifs, dispositifs médicaux, personnel médical et paramédical, médicaments produits pharmaceutiques, bâtiments, etc.

PEC : prise en charge

Activités de diagnostic

biologique et radiologique

Activités de soins et de

prise en charge thérapeutique

864

EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 12 – 2019Research article