Women in War Working Copy

Transcript of Women in War Working Copy

The Implications of Inequalities: Gender Role Socialization, the State, and Wartime Rape

Holly Williamson Arizona State University

Working Copy

Do Not Cite

Williamson 2

The Implications of Inequalities: Gender Role Socialization, the State, and Wartime Rape

Abstract Women and children are disproportionately affected by armed conflict, and have frequently been subjected to varied acts of sexual violence in war (United Nations 2013). A growing body of literature has sought to explain the nature and effects of wartime rape. However, a critical problem that persists concerns why wartime rape varies both within and across conflicts. Recent contributions suggest that combat group cohesion can explain why some groups employ rape as a military strategy, while others refrain from doing so (Cohen 2013; Wood 2009). In this line of argumentation, combatants in units with low social cohesion will be more likely to engage in sexual violence in an effort to cohere as a fighting group. While this research generates important findings, it fails to provide an effective answer as to how and why wartime rape should function to provide higher levels of cohesion for fighting units. In this paper, I explore the implications of gender inequality as an important and relevant factor in wartime rape, while also addressing some of the challenges with some of the leading explanations for wartime rape. I contend that the levels of gender inequality present during periods in which combatants were socialized into a set of gender norms at a young age has implications for the severity of rape across conflicts. Cross-national analysis using World Development Indicators (World Bank 2011) and a rape severity scale (Cohen 2013) provides preliminary evidence that the level of gender inequality present during combatants’ formative years can explain why enacting rape in conflict can facilitate group cohesion.

Williamson 3

Violence associated with war has generally been an expected cost of conflict. However,

limits on wartime violence have long been moderated through conventional agreements of jus in

bello. These laws addressing “justice in war” have been customarily accepted by combatants as

guiding norms of conflict, informing acceptable conduct during war for centuries (Alston and

Goodman 2013). Over the past half century, the development of formal international legal norms

has further attempted to moderate atrocities committed during war1, yet this has largely been in

relationship to interstate conflict and has disproportionately addressed concerns surrounding

identified combatants belonging to militarized bodies.

However, the face of war has begun to transform and the venue is no longer primarily an

interstate locale, but rather is situated within territorial nation-state boundaries expressed as

persistent and pervasive intrastate conflicts with civilians being regularly impacted by militarized

action. Along with this changing face of war, concerns about civilian targets, particularly women

and children, is on the rise (United Nations 2013). Where once acts of violence, particularly

sexualized violence, were considered unfortunate but expected costs of war, a norm has begun to

emerge since around the 1990’s that takes particular interest in atrocities enacted upon women

and children during conflict (Tripp 2013).

In this paper, I will begin by examining this transformation in modern warfare by

analyzing the ways in which gender and violence intersect during conflict. Next, I explore some

of the leading explanations for the variance in wartime rape both within and across conflicts.

Drawing upon these arguments, I outline the means by which notions of gender hierarchies

become integrated during the early childhood socialization of combatants and the implications

this has for enacting rape during war and in building combat group cohesion. In the final section,

1 See Alston and Goodman (2013) for a discussion on International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC), p. 404 – 485.

Williamson 4

I provide cross-national evidence demonstrating the linkages between gender inequality, combat

socialization theories, and the variance in wartime rape.

Gendered Violence in War

One of the more concerning consequences of modern warfare, as the United Nations

(UN) has noted, is that, “the vast majority of casualties in today’s wars are among civilians,

mostly women and children (United Nations 2013).” One way, amongst many in which women

and children are being impacted, is by being targeted for sexual violence by combatants - often

as a strategic weapon of war. The sheer numbers of those affected are chilling. The UN has

compiled data on some of the more severe conflicts and reported the following findings: “In

Rwanda, between 100,000 and 250,000 women were raped during the three months of genocide

in 1994. UN agencies estimate that more than 60,000 women were raped during the civil war in

Sierra Leone (1991-2002), more than 40,000 in Liberia (1989-2003), up to 60,000 in the former

Yugoslavia (1992-1995), and at least 200,000 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since

1998 (2014).”

With the impact of war on women and children increasing, this leads to questions about

protections and preventions for women and children. Existing treaty protections for civilians and

non-combatants are addressed in common Article III of all four Geneva Conventions of 1949,

which in part states that, “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading

treatment,” are wholly prohibited (ICRC 1949). However, the language employed in the treaties

within the body of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) has remained relatively gender

avoidant, failing to explicitly name rape as an atrocity of war. And it is here, in this historical

absence of rape in the language of law that the evidence of the existence of structural violence

expressed through the vehicle of gender hierarchies begins to be revealed. The omission of rape

Williamson 5

as a war crime in the historical legal treaties governing wartime conduct is only one of the ways

that it is implied that war has been considered the exclusive domain of men, relegating women to

an outlier position - relatively invisible, lacking agency, with rape and sexual violence

considered a normalized part of war processes - unfortunate but expected (United Nations

2013.)2.

However, notions of erga ormes suggests that certain peremptory norms exist for all

people, and further that states are obligated to secure and guarantee these inherent natural rights

of the individual. Yet, modern warfare situates women as the leading victims in war with sexual

violence often serving as a chosen weapon of soldiers. As such, women disproportionately carry

these costs of modern war that are in direct violation of jus cogens. The price of wartime rape is

high and is not limited to harm to the individual. It tears at the social fabric of communities,

traumatizes the victim, breaks up families, and leads to health related issues (i.e. HIV, unwanted

pregnancy, and STI’s). Furthermore, the legacy of psychological effects and potential legal costs

if redress is sought are costs that many post-conflict environments can little afford to field in the

fragile aftermath of war (United Nations 2013).

Current Explanations of Rape and War

Biosocial Hypothesis

The aforementioned concerns alone are sufficient impetus to engage scholars in

attempting to identify important causal factors pertaining to rape and war. However, other

2 This is not to infer that advances in the international human rights legal institutions have not been made. In fact, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (hereafter ICTY, 1993) included rape in its conceptualization of crimes against humanity, genocide, torture, etc. (United Nations 2013). However, the proliferation of this normative shift to states parties is questionable at best. Additionally, pubic outcries concerning the mass rapes in Yugoslavia and Rwanda are well documented, but victims still receive more social sanction than perpetrators leading to vast underreporting and invisibility as to the true extent of rape during war (ibid).

Williamson 6

features related to the presence of rape3 in war are equally puzzling. Severity of wartime rape

seems to vary both across and within conflicts (Cohen 2013; Wood 2006, 2009), which

undermines arguments that claim that rape is simply a prerogative of war and that it is in fact the

wartime setting that has allowed baser biological urges to be set free. This has often been coined

the opportunism hypothesis, which is articulated not wholly as a biological imperative, but rather

simultaneously perpetuated by the denigration of social norms during state breakdown that

creates a permissive environment to enact baser urges. While such biologically deterministic

explanations appeal to apparent “natural” differences between men and women, they are

problematic at best.

Gottschall (2004) purports that the biosocial theory is the singular theoretical explanation

that coheres the consensus of disparate theories concerning wartime rape into a sound causal

argument. He contends that the biosocial theory includes sociocultural mechanisms, but

“emphasizes that sexual desire is likely to be a primary influence on a soldier’s decision to rape

(Gottschall 2004, 129).” While Gottschall (2004) cedes that “(f)eminist scholars and activists

deserve credit for being the first to systematically investigate…wartime rape,4” he suggests that

the various feminist arguments have a “poor theory-data fit,5” arguing that empirical evidence

shows that patriarchy levels vary and that systematic and widespread rape both in peace and war

is sufficient evidence to undermine feminist claims. In turn, Gottschall (2004) advances the

biosocial argument, but first distinguishes it from biological determinism by noting that it is not

3 Moving forward I will generally refer to rape only. This is because the data I have chosen to use to identify empirical patterns makes clear distinctions between rape and sexual violence. Rape as a variable will be conceptualized later in this paper, but it is important to note this distinction at this point. Generally speaking, sexual violence might include acts of forced marriage and human trafficking that are considered to be conceptually distinct from rape in this case. 4 p. 130 5 ibid

Williamson 7

simply a blind biological genetic imperative that cause male soldiers to rape, but rather that

because wartime rape is present across time, space, cultures, religious and ethnic group

identifications, the common determinant that remains is the “simple sexual desire of individual

fighters,6” coupled with sociocultural influences that can explain the variation. In an effort to

bridge a divide, Gottschall (2004) attempts to suggest that sociocultural arguments cannot stand

without the inclusion of the genetic imperative.

Returning to Gottschall’s (2004) goodness of theory-data fit framework, empirical

evidence does not wholly support his claims. In part Gottschall (2004) draws upon biological

determinism, while simultaneously attempting to distance biosocial claims from it, to explain

how biology informs rape by describing a “peak physical attractiveness” mechanism. This

portion of the argument suggests that soldiers predominately target young women of

reproductive age due to the biological sexual desire imperative. He simultaneously states that,

“the evidence is indeed clear7” that this pattern exists, and yet “while (it) cannot be statistically

demonstrated, anecdotal accounts leave little doubt as to its accuracy.8”

However, Gottschall’s (2004) claims are wholly anecdotal with no empirical treatment of

his theory. Indeed, in contrast to Gottschall’s (2004) argument, Wood (2006) notes that women

in Rwanda participate in sexual violence, often inciting and encouraging men to rape, and that

US servicewomen have also been involved in the sexualized humiliation of detainees at Abu

Gharib and Guantánamo. Furthermore, the notion of the rape of the young and attractive needs to

be problematized. Case in point, a recent Reuters report stated that infants as young as 6 months-

old were victims of rape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and children as young

6 ibid 7 ibid 8 ibid

Williamson 8

as 4 years-old have been raped in Somalia with reparations being enumerated at the equivalent of

$150 (USD) (Nichols 2013). Additionally, while women are the primary demographic at which

wartime rape is targeted, sexual violence is also directed at other men in war more often than in

peacetime (Goldstein 2003). This suggests that outside of the context of war, soldiers enacting

homosexual rape are not “sexually attracted” to men per se, but rather are being propelled to act

by something other than “simple sexual desire9.” Furthermore, when contending that wartime

rape is primarily driven by libidinal tendencies, this in a sense infers that men are less able to

manage sexual impulses and that in contrast, women are presumed to be without sexual impulse

or desire, which only serves to deepen existing gender stereotypes. Even in peacetime, rape and

power are intimately connected, significantly undermining the validity of Gottschall’s (2004)

primary claim of sexual desire.

Combatant Socialization Theories

In contrast to biosocial claims, a nascent line of argumentation holds that mechanisms

associated with group cohesion and group socialization can explain the variance in wartime rape

across conflicts (Cohen 2013; Wood 2006, 2008, 2008). Cohen (2013) theorizes that low group

solidarity/cohesion amongst fighting units seems to be related to higher rates of rape amongst

these groups, which is further linked to the military recruitment strategy of combatants. As such,

combat groups that have been constructed as a result of abduction or conscription appear to enact

rape more often than voluntary armies, which Cohen (2013) suggests can explain variance in

wartime rape patterns across civil wars. However, an explanation as to why enacting rape should

serve to shore up group cohesion amongst the low solidarity combat groups has yet to be fully

developed and tested, which this paper seeks to remedy.

9 I discuss this issue further during the theorizing of my main argument.

Williamson 9

In another, but similar line of theorizing, Elisabeth Wood (2008) discusses distinct social

processes that are disrupted by civil war, which indelibly impacts and reshapes social networks.

Two social processes unpacked by Wood are military socialization and transformation of gender

roles, which have important implications for the theory addressed in this paper10. Military

socialization is at the heart of Cohen’s (2013) argument and is of particular relevance as to why

rape might be used to create cohesion amongst a group. Wood (2008) describes the rituals of

military training as formal and informal processes of hazing and initiation, along with drills and

the ‘tearing down and building up’ of the individual soldier. This socialization to conflict builds

cohesion amongst the group in order to wage war effectively as a unit. In essence, these groups

create a combat readiness culture that increases certainty and trust within combat groups that

have engaged in these rituals, which is valuable during the crisis of battle.

But, a question might be raised as to what might be the effect of gender roles in this

process of military socialization identified by Wood (2008)? In answer, Goldstein (2003) finds

support for the hypothesis that males are primed for war throughout childhood socialization and

combat readiness processes. He makes the case that, in essence, war is a glorified “test of

manhood” in many cultures and is considered an implicitly male enterprise11. In this sense,

Goldstein (2003) suggests that masculinity is often considered to be the equivalent to power,

strength, and emotional flatness. Support for Goldstein’s hypothesis that war is a test of manhood

suggests that the underlying mechanism at work in order for rape to serve as a solidarity building

function for the combat group is the enactment of hyper-masculinized values fostered within, and

10 My treatment of Wood’s (2008) social processes argument is partial. Wood (2008) distinctly discusses the ways in which these six processes are interactive via a process tracing within four nation-states (Peru, El Salvador, Sri Lanka, Sierra Leone). Due to the limitation in the number of cases she examines and the likelihood of path dependence particular to each country, I take liberty here to address the particular processes that are of interest to my main hypothesis. 11 See Goldstein’s (2003) hypothesis 5A and 5B for a more robust discussion.

Williamson 10

also inherent to, militarized settings. Cohen (2013) in part states that, “(mostly) male groups

commit sexualized violence – in part, perhaps, because it communicates norms of masculinity,

strength, and virility (464 – 465)12.” Equating masculinity with power is at the core of gender

asymmetries cross-nationally and is an important link to recognize when explaining wartime

rape.

However, Wood (2008) questions whether or not gender roles are so static in times of

civil war. She notes that women have often become part of insurgencies, sometimes as fighters,

but more often take on head of household roles that had previously been reserved for men. This

is in large part out of necessity, but Wood (2008) contends that the features of civil war create

radical displacement of gender roles. However, there are some challenges that ought to be raised

when considering this claim. While there are some all female insurgent groups (LTTE)13, and

some mixed-gender insurgency groups, this is hardly the rule (Wood 2008). Goldstein (2003)

finds that on the whole there are extremely few women fighters, which is indicative of gender

asymmetries pertaining to war since women who do fight, do so well. Additionally, Goldstein

(2003) finds that women often support war by reinforcing soldiers’ masculinity. Finally, social

structural change is painfully slow and even in times of great shock (i.e. civil war), it could be

argued that clinging to traditions (not just in terms of gender) can serve as orienting principles in

a time of great chaos and uncertainty.

12 Emphasis in original 13 LTTE refers to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The common reference to the rebel group is the Tamil Tigers. LTTE was a rebel separatist group active in Sri Lanka from around 1976 to approximately 2009 See the Department Of State Human Rights Report on Sri Lanka from 2009 for more.

Williamson 11

Gender Inequality

The scholarship in this area is fairly vast and operates from several distinct perches in

relationship to the role gender inequality plays in explaining rape during war. Perhaps the most

prevalent are arguments that claim that the presence of patriarchal structures alone is sufficient to

explain rape (Cohn and Enloe 2003; Koo 2002). While it is important to consider patriarchy, it is

not sufficient to explain the curious variance that exists across conflicts. Some social systems are

in fact patriarchal, and yet do not engage in collective and/or wartime rape. Consider, for

example, that while Bosnian women were victims of systematic rape, Bosnian fighters did not on

the whole in turn employ rape as a weapon of war14. Here it might be important to consider

whether or not combatants are in the aggressor or defender role, as these roles might also be

couched in gendered terms as power dynamics often split along gendered lines.

Additionally, another variant of the gender inequality argument claims that existing

gender inequity in societies has a psychological effect that results in the acceptance of violence

being enacted upon women (Green 2006; Seifert 1996). This argument further holds that the

inherent destruction of women via the use of collective rape is a strategic and symbolic effort to

annihilate the culture of the enemy (Seifert 1996). While each of these arguments may be

credible, they have difficulty answering to the patterns of variance in wartime rape.

In an effort to test the leading arguments concerning rape and war, Cohen (2013) tested a

variant of the gender inequality hypothesis, which asserted that, “Greater gender inequality is

associated with conflict-wide rape (2013, p. 463).15” While Cohen (2013) found that the

14 Another example might be related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Both group identities have fairly particular prescribed roles for men and women in society, yet this conflict is not characterized by the extreme levels of wartime rape observed in many other conflicts. This suggests that other gender asymmetries alone are not sufficient to explain the variance. 15 Emphasis in original.

Williamson 12

coefficient representing gender inequality was consistently positively correlated, this hypothesis

was not found to be significant in her model, leading to questions about the exact nature of the

presence of gender inequality and wartime rape. It is the attempt to answer this question that is

the purpose of this paper.

A Theory of Gender Role Socialization

Early Childhood Identification of Gender Differentiation

A critical difficulty that is apparent in the approach previous scholars have taken to test

gender inequality pertains to the ways in which they have conceived of the relevance of its

presence. It is important to consider that other scholars have already made the link between the

presence of gender inequality and conflict onset (Caprioli 2005; Fearon 2011), but equally

significant and substantive links to wartime rape remain somewhat elusive. I contend that the

challenge associated with measuring the presence of gender inequality at the time of war is that it

misses key socializing dimensions related to gender, essentially rendering prior processes

entirely exogenous to the phenomenon of wartime rape.

Recognition of the importance of early childhood development and gender role norming

has critical implications for the presence of wartime rape. Gender differentiation and the sense of

one’s own gender identity is one of the earliest distinctions that individuals are primed to assess.

Consider that even prior to birth, the potential gender of a child is one of the first questions

considered, and further that the living environment in which the child will be reared is thusly

designed to normative gender specifications assigned to the child’s sex. Indeed, as early as three

years of age, children are able to identify their own gender and that of others and further feel

some pressure to follow the expected behavior ascribed to the gender role the individual has been

assigned to (Blakemore, Berenbaum, and Liben 2008; Bussey and Bandura 1999). Interestingly,

Williamson 13

much of this gender role identification occurs prior to the period of earliest available memory

recall, thusly resulting in individuals’ tacit acceptance of gender norms with few exceptions.

Although it by no means can be argued that gender role socialization is a fixed and

completed process at three years old, certain orienting principles become difficult to unravel

since the individual presumably has little cause to question what is considered to be a “fact”. In

his treatment of Durkheimian postulations concerning the constraints of social facts, Parsons

(1968) discusses the composition of social structures through which the individual is

simultaneously shaped and shapes. He further asserts that the theorizing of both Durkheim and

Piaget suggest that moral attitudes and logical thought are largely developed during socialization

as a child (Parsons 1968, 401), affirming that periods of early childhood are critical in terms of

the assessment of gender differentiation and moral thought. Despite the fact that Bussey and

Bandura (1999) assert that sociocoginitive development occurs across a lifetime, they also

suggest that modeling of gender-linked roles leads to early gender differentiation identification,

although ages can range somewhere between three and seven across various gender role

development theories.

Gender Hierarchies

Hudson and Brinton (2007), paraphrasing French Philosopher Sylviane Agacinski,

observe that gender is the first social difference identified as a child and is the frame by which

other social and structural distinctions are understood. Furthermore, incorrect identification of

gender difference is a heavily sanctioned process, resulting in immediate and intense discomfort

for the individual acting outside of prescribed gender roles (Bussey and Bandura 1999).

Additionally, between ages three and eight, children begin to segregate by gender and choose to

play with other children they identify as being of the same gender (Goldstein 2003; Maccoby

Williamson 14

1990), which allows gender roles and gender differentiation to become even more deeply

embedded. Goldstein (2003) has found some support for the hypothesis that this type of early

childhood segregation serves as a training ground for later war roles, with play in gender specific

male groups modeling combat (i.e. play fighting, games of aggression, games engaging

war/battle scripts) (2003, 228 -249).

Returning to the earlier, albeit brief discussion of social facts, this argument can thus be

oriented to the inherent problem of the social facts surrounding gender asymmetries. They exist

exogenous to the individual and are not per se created by the individual, rather are reenacted and

as such recreated into a version of social reality. The assumption that gender distinctions are

“natural” as advanced in some capacity by Gottschall (2004) is to effectively fail to investigate

the sources and historical process of these distinctions. Enloe (2004) argues that “(a)ny power

arrangement that is imagined to be legitimate, timeless, and inevitable is pretty well fortified

(3),” which is undoubtedly the case with asymmetrical gender distinctions.

However, before examining how these hierarchies might explain patterns of wartime rape

in intrastate conflict, it is critical to consider Lasswell’s (1950) exposition on the study of politics

and the influential. He states that “politics (is) who gets what, when, (and) how,” and that power

dynamics largely shapes this process (Lasswell 1950) . Situating gender hierarchies within the

frame of this series of questions serves to demonstrate how perceived gender asymmetries might

have implications for rape as a weapon of war. Answering these questions within the framework

of recognizing the latent messages that are communicated concerning gender distinctions will

illustrate how gender inequality and wartime rape are linked.

Simone de Beauvoir and Sylviane Agacinski identify critical societal and structural

features at the heart of gender hierarchies being accepted as (social) fact. First, Simone de

Williamson 15

Beauvoir (1978) addresses what she describes as the duality of Self and Other, which has

implications for how both men and women process the role of women. She states, in part, that

women are “nothing other than what man decides; she is thus called ‘the sex,’ meaning that the

male sees her essentially as a sexed being; for him she is sex, so she is it in the absolute. She is

determined and differentiated in relation to man, while he is not in relation to her; she is the

inessential in front of the essential. He is the Subject; he is the Absolute. She is the Other (1978,

6).” Sylviane Agacinski (2001) moves the argument a step further when she asserts that within

hierarchical structures, “woman is neither the other nor different, but only an incomplete being,

inferior or mutilated (x).”

Keeping in mind the relegation of women to an inferior space, Goldstein’s (2003)

confirmed hypothesis concerning the feminization of enemies further supports the claim raised in

this argument that the value individual soldiers assign to gender categories has implications for

variance in wartime rape across conflicts. Furthermore, the gendered value assignment is

indelibly linked to the measure of structural gender inequalities present during early childhood

socialization. These structures are so profoundly a part of daily life that they are in fact, the

mortar with which individual beliefs about their social world are built. They are deeply

foundational and nearly impossible to shift once grounded into the psyche as social fact.

For example, Goldstein (2003) draws on Thucydides and utilizes the Melian dialogue to

illustrate historically the various means employed in the feminzation of the enemy (357), but this

hypothesis also serves as evidence of systemic gender hierarchies over time. In the Melian

Dialogue, Thucydides describes the role of women as private property and spoils of war, which

is still relevant today in the normalization of wartime rape as a routine and often expected part of

conflict. However, other means of the feminization of the enemy, which includes castration, acts

Williamson 16

of homosexual rape, simulating positions of domination, and insults and intimidation leveled in

gendered terms, further substantiate the problem of gender hierarchies in wartime violence

(Goldstein 2003). These forms of “symbolic domination” demonstrate the implicit assumption of

the feminine as entirely inferior and the masculine as superior. Enloe (2004) asserts that this

asymmetry is further realized by gendering the political. Nationalism might be equated with the

masculine in-group and the feminine with the rebel out-group16.

Applying the structural imperatives concerning gender to Lasswell’s (1950) political

question series, the following answers might be framed. Men get power during war by leveling

wartime rape against women as a symbolic attack on the “manhood” of the enemy. Additionally,

groups with low social cohesion gain group solidarity by enacting collective wartime rape as an

act of power and domination, thereby affirming the superiority of masculinity. Also, women get

victimized and subjugated during collective wartime rape by the reenactment of asymmetrical

scripts from childhood concerning gender roles. Finally, men get (or pursue) power through

collective rape during war as a result of being socialized into particular notions of gender

hierarchies during childhood.

16 Consider the following excerpt from Enloe (2004) concerning Serbian militia fighter, Borislav Herak who was indicted for being a part of perpetuating the systematic rape during the conflict in former Yugoslavia in 1991. Enloe interviewed Herak and found some of these themes to be present in his responses: “He was a man. More to the point, he was a man raised in the 1960’s, ‘70’s, and ‘80’s to think of himself as masculine. Or perhaps it is more useful to say that Borislav was a man raised to think of himself as needing to be masculine. If we leave this process out of the story, if we treat it as unproblematic, then we leave out the exploration of the gendered politics of nationalism. With such a gaping omission, we will have a hard time arriving at a satisfactory explanation of why a factory worker became a militarized rapist (p. 101).” This example is illustrative of the value assignment to gendered categories and some of the critical intersections with these values.

Williamson 17

Of course exceptions always apply – women are often complicit in violence and

oppression, not only in terms of themselves, but also others (Enloe 2004)17. However, these

incidents are typically the exception and not entirely the rule. In any case, examples of women

oppressing other women might be attributed to a sort of false consciousness that the systemic

structures described in this theory are likely to foster18. Nonetheless, the potential implications of

a theory of gender role socialization and soldiers conduct concerning wartime rape calls for an

empirical test of the claims posited here19.

As such, I hypothesize that the presence of a higher degree of gender inequality during

the early childhood socialization of combatants can be linked to the severity of wartime rape.

This is a directional hypothesis in that I claim that as gender inequality increases, then the

severity of wartime rape also increases.

Hypothesis (1): Greater measures of gender inequality present during the childhood

socialization period of state combatants is positively associated with rape by state actors during

civil war.

17 See Abu Gharib and Guantánamo, along with women of Rwanda inciting rape (United Nations 2013). 18 Consider Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth (2004) for more on the notion of the identification of the oppressed with the oppressor. Fanon articulates the problem colonization in the psychology of the colonized as believing in the identity prescribed by the oppressor. 19 Throughout the theorizing portion of this paper, the concept of implicit was mentioned, but not fully expounded on. A concept of social cognition is relevant to the way by which soldiers access prior scripts. Consider the following: “The identifying feature of implicit cognition is that past experiences influence judgment in a fashion not introspectively known by the actor (Greenwald and Banaji 1995, 4).” Thus soldiers and women who have been subject to wartime rape alike may be compelled to take action based on prior scripts of gender inequalities without awareness, meaning that this socialized imperative can direct individual behavior without conscious awareness of its presence.

Williamson 18

Gender Role Socialization and Wartime Rape: Cross-National Analysis

Data and Methods

This design draws upon existing data to perform a classical linear regression (OLS)

analysis. This is a cross-national analysis, with intrastate conflict as the unit of analysis. A lagged

socialization period has been established prior to conflict onset by employing proxy indicators

for gender inequality. A lagged period of 18 – 25 years prior to conflict onset has been

established for the predictor variables in the model, but due to the relatively small sample size

and in order to limit the large number of inputs that would result in a degrees of freedom

problem, a mean score for each independent variable encompassed over the eight year period has

been established for each conflict. Several different datasets and sources have been utilized for

the empirical testing of this theory, which will be described in more detail below.

Variable of Interest: Severity of Rape by the State

Drawing upon Cohen’s (2013) wartime rape severity dataset, which includes the coding

of rape severity for 86 major civil wars occurring between 1980 – 2009, I have operationalized

the rape severity variable for the state combatants to represent the dependent variable in this

analysis20. The choice to examine strictly state level rape is due to matching the proxies

representing gender inequality most appropriately with the childhood socialization experiences

of known soldiers associated with the state21. Indicators are measured at the state level and as

20 Cohen notes that this is a data set built from the existing framework of (Fearon and Laitin 2003) and coded rape severity from a similar coding schema established by (Butler, Gluch, and Mitchell 2007) premised on the widely used Political Terror Scale (PTS) from (Gibney, Cornett, and Wood 2011). For more information on the coding procedures utilized, please see Explaining Rape During Civil War: Cross-National Evidence (1980 – 2009). 21 While this is a conceptual choice for this paper, in future, I would like to also explore models that examine conflict-wide severity, which also accounts for rebel groups. In many ways, it is a logical choice to consider the conflict as a whole due to the unit of analysis being the civil war. Since the examination is concerned with intrastate dynamics, most combatants would likely have

Williamson 19

such, the rape severity measure ought to be state level to avoid any ecological fallacies. The state

combatant rape severity variable is an ordinal measure from 0 – 3, where 0 = little to no rape

severity and 3 = rape as a strategic weapon of war. Cohen (2013) utilized US Department of

State reports and various human rights reports to capture rape severity across the cases. For the

conflict level value, the highest ordinal measure a state incurred in a conflict year over the course

of the conflict is the value assigned for the rape severity measure.

Soldiers’ Childhood Socialization Environment

To account for the childhood socialization periods for soldiers, several considerations

were undertaken, but ultimately conceptual assumptions have been advanced to establish a lag

period of 18 – 25 years prior to conflict onset22. Considering that gender role socialization

largely occurs between ages 3 - 7, this period ought to generally capture the socialization period

for soldiers ranging between 18 – 30 years old. While shifts in the indicators could vary

significantly over two decades, annual shifts tend to be less substantive, which allows for this lag

period to account for the general societal climate during the socialization period of interest23.

Some cases fall outside of the available data parameters for the indicators being utilized. For

example, the conflict period for the Angola case is 1975 – 2002, which means that the lagged

period would cover the years 1950 – 1957. For three of the indicators used to proxy gender

inequality, this period is prior to the first available data reported in 1961. However, since annual

been socialized under the same gendered structures. However, since rebel groups are challengers to the state, this analysis will focus on state behavior. 22 One option included an effort to code military data from the CIA World Factbook covering the same year range (1980 – 2009) as Cohen’s (2013) dataset. However, this effort did not yield significant enough data to establish proportional measures reflective of the state military machinery engaged in conflict. 23 Ideally, child soldier data would be used to control for the issue of child soldier socialization. However, that data is not readily available, but can be added in the future. Due to an already significant reduction in cases, those conflicts with known child soldiers remain in the model, but the model does control for recruitment.

Williamson 20

change is relatively minute, any cases that falls within 5 years or less of 1961 will be preserved

and the value for 1961 will be utilized in the analysis.

Indicators

Gender Inequality and Soldiers’ Childhood Socialization Environment

Debates are rampant concerning how to effectively measure the presence of gender

inequality. While many efforts have been advanced to create various indices reflective of the

lived experience of women, available data for the time period of interest does not allow for the

utilization of those developed indices. The lag period needed to account for childhood

socialization ranges rules out several robust data indicators as a means of measurement (i.e. CIRI

Women’s Economic, Social, and Political Rights and Womanstats). Returning to the literature,

both Fearon (2011) and Carprioli (2007) describe the use of fertility rates as a good proxy for

other gender indices and have further employed this indicator to reveal substantive links between

the presence of gender inequality and conflict onset. I explore Caprioli’s (2005) logic for

employing fertility rates in this way.

Caprioli (2005) notes that, “(a)lthough gender roles change over time and are culturally

dependent, gender is used as a benchmark to determine access and power, and is the rubric under

which inequality is justified and maintained (165) .” As such, essential to the argument being

raised here is the assumption that gender role socialization does indeed change over time and that

the proxy variables employed to represent gender inequities ought to effectively serve as

indicators representative of the relationship between gender hierarchies and access and power.

Caprioli (2005) further claims that fertility rates serve as a direct indicator of gender inequality

and a robust proxy indicator for lower levels of education, employment, and decision-making

Williamson 21

power (169)24. Data from the World Bank allows for the collection of stable fertility rate data

over the periods of interest25.

While Caprioli (2005) indicates that fertility rates can effectively proxy for many

dimensions of gender inequality, the physical dimension seems largely underrepresented from

fertility rates alone. Fertility rates address complex issues related to maternal health, but other

indicators might address physical integrity and safety of women as a measure of gender

inequality. In consideration of Amartya Sen's (1990) calculation of the missing women in the

world, by accounting for the percentage of the population that is female and the life expectancy

ratios between men and women, a general sense of the physical integrity of women might be

assessed26. Again, World Bank data has consistent World Development Indicators (WDI) from

which to collect this information for analysis.

Consequently, the independent variables under analysis create a multi-dimensional

picture of the presence of gender inequality. By employing mean values for fertility rates, female

to male life expectancy ratios, and accounting for the percentage of the population that is female

over the lagged eight-year soldier socialization range, a comprehensive multivariate statistical

model representing the earlier theorizing outlined should serve as a meaningful empirical test of

the argument described.

Control Variables

I am interested in adding a link to the some of the conceptual map already established by

Cohen (2013) and Wood (2005, 2008). Cohen (2013) argues that wartime rape serves as a

24 For more, see Caprioli (2005) Primed for Violence: The Role of Gender Inequality 25 See data file for more- (World Development Indicators). There are some exceptions that have been outlined in the body of the paper. 26 (Anand and Sen 1995; Sen 2001) suggest a statistical calculation that might better situate these variables in relationship to each other and perhaps provide a more nuanced picture of the implications of this design.

Williamson 22

cohering function for combat groups with low social cohesion, largely due to the ways by which

they were recruited for combat. While this explanation makes an important contribution, I am

concerned with exploring how and why wartime rape should improve group solidarity. Because

of this, the control variables used in this OLS model include most of the variables utilized in

Cohen’s (2013) state actor models27. These variables are briefly described below.

Genocide is a dummy variable using existing (and updated data) on genocide and

politicide between 1955 – 2006 and for this model, genocide only accounts for genocidal acts

perpetuated by the state. Also included are controls for population (log) from the Penn World

Tables 7, ethnic war28 to assess whether or not the conflict was based on ethnic claims, and

conflict aim controls for whether or not the war was secessionist, regime change, or mixed29.

Other controls include the magnitude of state failure, troop quality (log), pressganging, and

conscription.

Data Limitations

A note must be added to address significant data limitations. Cohen (2013) clearly

articulates that the reliability of true values of rape reports is not wholly available. Problems of

potential overrepresentation of rape in a given conflict due to media attention associated with

conflict events, along with problems of victim underreport (previously mentioned), plagues a

research agenda engaging questions surrounding rape. With that being said, the consensus

amongst scholars to rely on similar data with significant enough patterns indicative of validity

suggest that these limitations should not wholly undermine the analysis employed in this design.

27 See Cohen (2013) Model 4 and 5 for replication purposes and more on the control variables. I note that most of the same variables are used for control, but Cohen’s model is operationalized by conflict year, which allows for the logic of the account of certain variables appropriate under that unit of analysis, but less than ideal with the conflict-level model described here. 28 From Fearon’s original coding schema 29 From Fearon’s original coding schema

Williamson 23

Additionally, due to the lagged nature of this design, eleven cases were eliminated due to the fact

that the length of war was such that data was not available for the socialization period of interest.

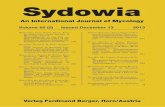

Table 1: Soldier Gender Socialization and Wartime Rape

Table 1: Summary of OLS regression (β1, β2, β3) of effect of fertility rates as a proxy for gender inequality on rape as a weapon of war. NOTE: Values represent OLS parameter estimates with standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0: 05, **p < 0: 01, ***p < 0: 001 Interpretation

In Model 1, the primary variable indicative of gender inequality, fertility rates, is

statistically significant, which suggests that the levels of gender inequality present at the time of

Model β1 (SE) Model β2 (SE)

Model β3 (SE)

Model β4 (SE)

(Intercept) -7.70 (6.62) -1.05 (9.23) -8.49 (6.60) -1.05 (9.19) Gender Inequality Fertility rates 2.93 (1.16)* 2.31 (1.08)* 2.79 (1.16)* 2.52 (1.09)* Percentage of population (female)

1.27 (1.26) 1.44 (1.26)

Life expectancy (female/male ratio)

-3.98 (3.62) -4.36 (3.60)

Controls Genocide (by government)

5.29 (3.04) 4.01 (2.94) 4.52 (2.96) 4.91 (3.02)

Magnitude of state failure

3.93 (8.06) 6.06 (7.91) 4.11 (8.07) 5.66 (7.88)

Polity2 6.29 (2.49)* 6.31 (2.48) 6.56 (2.48)* 6.04 (2.48)* Troop Quality (log) 3.96 (1.29) 5.35 (1.24) 9.97 (1.29) 4.23 (1.24) Population 4.59 (6.60) 2.67 (6.18) 5.30 (6.58) 2.17 (6.17) Ethnic War 7.21 (1.80) 1.29 (1.78) 9.83 (1.79) 9.78 (1.79) Conflict Aim 2.90 (1.81) 2.12 (1.75) 2.59 (1.80) 2.51 (1.78) Pressganging 5.58 (2.76)* 5.60 (2.78)* 5.63 (2.77)* 5.55 (2.77)* Conscription -5.17 (2.97) -1.88 (2.81) -1.14 (2.92) 3.91 (2.84) N 63 63 63 63 Adjusted R2 0.17 0.16 0.17 0.17 Residual standard error 0.93 0.93 0.93 0.93

Williamson 24

the gender role identity formation for combatants helps to explain patterns of rape employed by

the state in war. Furthermore, fertility rates remains significant across all four models reported,

in spite of different changes in controls, which provides additional support for the argument that

greater levels of gender inequality for combatants during childhood does indeed have an impact

on the severity of wartime rape. These four models have been run to manage problems of

collinearity. In Model 2, both the percentage of population (female) and life expectancy variables

are been removed with the result being that the primary proxy for gender inequality, fertility

rates, remains significant. Models 3 and 4 remove one of each and the same significance holds

for fertility rates across all models. In fact, several different model specifications garnered the

same results30, suggesting that the role of gender inequality in explaining variance in wartime

rape is a critical one.

The theory raised here does not seek to undermine the group cohesion hypothesis

advanced by Cohen (2013), but rather it addresses the mechanism that makes collective rape an

instrument of cohesion for the group. This finding supports the theoretical claims raised to

address these important linkages. Importantly, Cohen’s (2013) findings that combatant

recruitment mechanisms help to explain variance in wartime rape remain robust even with

inclusion of the gender inequality predictor(s). In particular, the more severe forcible recruitment

strategy on the part of the state, pressganging, remains significant in all four models. Also, while

the adjusted r-squared value suggests that only under a quarter of the variance in the regression

line can be explained, the values match closely to Cohen’s (2013) suggesting that the theory that

undergirds this argument is consistent across the two research designs. All in all, these findings

offer empirical support for the gender inequality and gender role socialization argument raised,

30 Not reported in this paper.

Williamson 25

but a different statistical model (ordered probit model) would likely be a better option due to bias

related to the dependent variable.

Conclusion

The presence of gender inequality as a causal mechanism in explaining state perpetuated

rape in intrastate conflict finds strong support in this research design. These findings have crucial

implications for policymakers, states in conflict, and post-conflict states alike. Policymakers

ought to consider the troubling outcomes for ongoing gender asymmetries and the terrible

individual costs associated with them. If gender hierarchies persist, this model suggests that the

likelihood of state combatants to use rape as weapon of war against civilians if war returns is

high, which could have significant repercussions for state stability and reconstruction efforts.

Furthermore, scholars engaged in research surrounding the topic of rape and war should

problematize questions that fail to consider gender asymmetries as part of their explanations. The

growing body of literature on group socialization theories is one area that ought to consider how

including measures to account for gender hierarchies might serve to strengthen the cohesion of

their causal story.

As for this design, while it is simply a beginning, it has the promise of revealing other

causal stories. First, the statistical modeling of this design needs refinement, perhaps enlarging

the n, considering other units of analysis, or more complex models that can account for the

different measures inherent in the variables used. However, of more substantive value, would be

adding in other identity differentiation dimensions (ethnic, religious, national identities) in a

more meaningful and interactive way. Considering that this theory argues that the first distinction

individuals learn to identify is gender, the ways in which differentiation is employed (i.e. ethnic

identity) may be intimately linked to gender. Case study that explores these intersections is

Williamson 26

critical in enhancing the early findings of this study. The hope of such an agenda would be to

engage research that can have a meaningful impact on the lived experiences of survivors, both

victims and perpetrators alike, and begin to eradicate the scourge that is rape and its attendant

human suffering.

Williamson 27

Bibliography

Agacinski, Sylviane. 2001. Parity of the sexes. New York: Columbia University Press.

Alston, Philip, and Ryan Goodman. 2013. International Human Rights: The Successor to International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics and Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anand, Sudhir, and Amartya Sen. 1995. “Gender Inequality in Human Development: Theories and Measurement.” http://economics.ouls.ox.ac.uk/12470/1/sudhir_anand_amartya_sen.pdf (December 16, 2013).

Beauvoir, Simone de. 1978. The Second Sex. New York: Knopf.

Blakemore, Judith E. Owen, Sheri A Berenbaum, and Lynn S Liben. 2008. Gender Development. Hove: Psychology.

Bussey, Kay, and Albert Bandura. 1999. “Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Development and Differentiation.” Psychological Review 106(4): 676–713.

Butler, Christopher K., Tali Gluch, and Neil J. Mitchell. 2007. “Security Forces and Sexual Violence: A Cross-National Analysis of a Principal-Agent Argument.” Journal of Peace Research 44(6): 669–87.

Caprioli, M. 2005. “Primed for Violence: The Role of Gender Inequality in Predicting Internal Conflict.” International Studies Quarterly 49(2): 161–78.

CAPRIOLI, MARY et al. 2009. “The WomanStats Project Database: Advancing an Empirical Research Agenda.” Journal of Peace Research 46(6): 839–51.

Cingranelli, David L., David L. Richards, and K. Chad Clay. 2013. “The Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset.” http://www.humanrightsdata.org.

Cohen, Dara Kay. 2013. “Explaining Rape during Civil War: Cross-National Evidence (1980–2009).” American Political Science Review 107(03): 461–77.

Cohn, Carol, and Cynthia Enloe. 2003. “A Conversation with Cynthia Enloe: Feminists Look at Masculinity and the Men Who Wage War.” Signs 28(4): 1187–1107.

Department Of State. The Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affairs. 2009. Sri Lanka. Department Of State. The Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affairs. Report. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2008/sca/119140.htm (May 13, 2014).

Enloe, Cynthia. 2004. Curious Feminist: Searching for Women In a New Age of Empire. University of California Press.

Williamson 28

Fanon, Frantz, and Richard Philcox. 2004. The wretched of the earth. New York: Grove Press.

Fearon, James D. 2011. “Governance and Civil War Onset.” https://openknowledge-worldbank-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/handle/10986/9123 (December 16, 2013).

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. 2003. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” The American Political Science Review 97(1): 75–90.

Goldstein, Joshua S. 2003. War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa. Cambridge University Press.

Gottschall, Jonathan. 2004. “Explaining Wartime Rape.” The Journal of Sex Research 41(2): 129–36.

Green, Jennifer Lynn. 2006. “Collective Rape: A Cross-National Study of the Incidence and Perpetrators of Mass Political Sexual Violence, 1980--2003.” Ph.D. The Ohio State University. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/docview/305299814/abstract?accountid=4485 (December 17, 2013).

Greenwald, Anthony G., and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 1995. “Implicit Social Cognition: Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Stereotypes.” Psychological Review 102(1): 4–27.

Hudson, Valerie M., and Carl H. Brinton. “Women’s Tears and International Fears: Is Discrepant Enforcement of National Laws Protecting Women and Girls Related to Discrepant Enactment of International Norms by Nation-States?” http://womanstats.org/APSA07HudsonBrinton.pdf (December 8, 2013).

“ICRC Databases on International Humanitarian Law.” 00:00:00.0. http://www.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/vwTreaties1949.xsp (December 16, 2013).

Koo, Katrina Lee. 2002. “Confronting a Disciplinary Blindness: Women, War and Rape in the International Politics of Security.” Australian Journal of Political Science 37(3): 525–36.

Lasswell, Harold Dwight. 1950. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How. P. Smith.

Maccoby, Eleanor E. 1990. “Gender and Relationships: A Developmental Account.” American Psychologist 45(4): 513–20.

Nichols, Michelle. 2013. “Babies as Young as Six Months Victims of Rape in War: U.N. Envoy.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/04/17/us-war-rape-un-idUSBRE93G13U20130417 (December 16, 2013).

Parsons, Talcott. 1968. The Structure of Social Action: A Study in Social Theory with Special Reference to a Group of Recent European Writers. Vol. 1, Vol. 1,. New York; London: Free Press : Collier-Macmillan.

Williamson 29

Seifert, Ruth. 1996. “The Second Front: The Logic of Sexual Violence in Wars.” Women’s Studies International Forum 19(1–2): 35–43.

Sen, Amartya. 1990. “More than 100 Million Women Are Missing.” The New York Review of Books 37. http://books.google.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/books?hl=en&lr=&id=TUdaFwb2uGAC&oi=fnd&pg=PT221&dq=100+million+missing+women+Sen&ots=Exxm64rIM5&sig=LvUTvaSzIfHLobEQzBKXeygAJOU (December 16, 2013).

———. 2001. “The Many Faces of Gender Inequality.” New republic: 35–39.

Tripp, Aili Mari. 2013. “Toward a Gender Perspective on Human Security.” In Gender, Violence, and Human Security: Critical Feminist Perspectives, eds. Aili Mari Tripp, Myra Marx Ferree, and Christina Ewig. New York: NYU Press.

United Nations. “Background Information on Sexual Violence Used as a Tool of War - Outreach Programme on the Rwanda Genocide and the United Nations.” http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/about/bgsexualviolence.shtml (December 16, 2013).

Wood, Elisabeth Jean. 2006. “Variation in Sexual Violence during War.” Politics and Society 34(3): 307–41.

———. 2008. “The Social Processes of Civil War: The Wartime Transformation of Social Networks.” Annual Review of Political Science 11(1): 539–61.

———. 2009. “Armed Groups and Sexual Violence: When Is Wartime Rape Rare?” Politics & Society 37(1): 131–61.

World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development.