V. Dintchev. Classification of the Late Antiques Cities on the Dioceses of Тhracia and Dacia. –...

Transcript of V. Dintchev. Classification of the Late Antiques Cities on the Dioceses of Тhracia and Dacia. –...

ARCHAEOLOGIA BULGARICA 111 1999 No 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Articles

Niko/ova, L.: Dubene-Sarovka 1181-3 in the Upper Stryaпш Valley (towards the periodization and chronology of Early Bronze 11 in the Balkans) ... ...... ....... ... .. .... ... ....... ... ... ... 1

Golubovic, S.: (YU): А Grave in the Shape of а Well from the Necropolis ot· Yiminaciшn ........ 9

Boteva. D. : Two Notes on D. Clodius AIЬinus ............................................. ..... ...... .. ................ ..... 23

Ku/lef, 1./Djingova. R./Kabakcltieva. G.: On the Origin ot' the Roman Pottery from Moesia lnferior (North Bulgaria) ................. .. ...... ...... ... .................. .......... ... .... ..... .. .. ... .. ... ..... 29

Dinrchev, V.: Classification of the Late Antique Cities in the Dioceses of Thrш.:ia авd Dacia .......... 39

Daskalov, M./Dimitmv. D.: Ein Paar шlthropozoomorphe Bugelt'ibeln (des. sog. Dnjeprtyps) aus Sudbulgarien ...... ... ... ..... ..... .... ......... ..... .... .................. ..... .. .... .. ....... .. ...... .. .. ........ ... ... .. .. ....... .. ...... . 7'5

Atanasov, G.: On the Origin, Function and the Owner of the Adornments of· the Preslav Treasure from the 1 0''' Century ............................................... ..... .. .. ... ............ ....... .......... 81

Reviews Ha,./toiu, R.: Die fruhe Yolkerwanderungszeit ir1 Rumaпieв. Bukarest 1998. (Сипа. F USA) ... ....... ........................... .. .............. ...... .. ... ..... ...... .......... ........ ......... 9'5

Editor: Mr. Lyudmil Ferdiпandov VAGALINSKI Ph.D. (lпstitute ot· Archaeology at Sof'ia)

ARCHAEOLOGIA BULGARICA is а four-пюпth joнrrшl (thricc а уеаг: 20 Х 28 cm: са. 1 ОО pages ш1d са. 80 illustratioпs per а nurпber: colotJred cover) \VI1ich preserнs а pнЫisl1i11g t·or-нm for research in archaeology iп thc widest seпse ot' the word. Tl1er·e аге rю r·estrictioш; t"or time and territory btrt Sot1tl1easterr1 Енrоре is the ассеrн. Ohjecti,,e: interdisciplinary research of archaeology. Contents: articles. revicws and пcws. Laщ~ua.~es: Eпglish. Gerrнan апd Freпch .

/nte/1(/etl l'eшlas : Scholars and studerнs of the followiпg fields: Archaeology. Numismatics, Epigraphy. Aпcient History, Medieval History, Oriental Studies, Pre- arн.J Early History. Byzшнine Studies. Anthropology, Palaeobotany. Archaeozoology. Histor·y of Religion. ot· Art. of Architecture. ot· Techrюlogy. of' Medicine. Sociology etc .

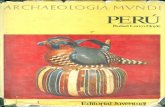

011 lhc t"O\'Cr: а ~1t111c porlrail ot· Rurnaв cшpcror Diщ; lcliaв ("!) 1 21.(4-.Щ:'i ). Naliorral M1r~CIII1J ot· Лrt· IJacolo~y-Sotla .

JSSN 1310-9537

Archaeo\ogia Bulgarica III 1999 3 39-73 Sofia

CLASSIFICATION OF ТНЕ LATE ANTIQUE CITIES IN ТНЕ DIOCESES OF THRACIA AND DACIA

VENTZISLA V DINTCHEV

Notwithstanding that the classification of the late antique cities has not been а central point of interest for the modern historiography, in the puЬiications а certain division has been suggested, or at least presumed. Differences in the aspects of studies reflect on the classification purposes, criteria and models. Sometimes when there is а wider researclting interest as proЬiems, in one апd the same puЬlication definitions coming from different in purpose and criteria classification models are used.

The analysis of the late antique sources displays а certain insecurity in the definitions of cities used, and respectively - in the views of corresponding authors and their contemporaries concerning the city statute of а particular settlement, concerning the essence itself of the city statute and the city way of living in general (Ciaude 1969, 10-14, 201-202; Курбатов 1971, 5-6, 60; Velkov 1977, 73; Ravegnani 1983, 12-24; Dagron 1984, 7-9; Schreiner 1986, 26-30; Suceveanu/Barnea 1993, 174; Dunn 1994, 60-67, 77-78; Динчев 1998, 16-23). For that reason the classification of the towns of the Late Antiquity, including the dioceses of Thracia and Dacia, can not Ье established only or primarily on the base of the differences in the definitions, i.e. on the terms used in the sources to denote them.

One of the classification models for the late antique cities is based on their origin (Ciaude 1969, 203-223; Suceveanu/Barnea 1991, 179). А modern classification of the late antique centers must reflect mainly the differences in their demographic and size parameters, апd in their real importance as economic, administrative, cult and/or military centres.

Definitions of size and importance can Ье found in almost every puЬlication for the city life in the Late Antiquity. They are most often with two major meanings -"small" cities and "large" cities represented in different variants and nuances 1. Towns of "middle importance" (Bavant 1984, 286) or "middle" towns are mentioned (Курбатов/Лебедева 1986, 103, 113). The definitions, however, are not always precise from the point of view of the criteria used and are usually without concrete classification parameters А basic requirement for the classification of

the late antiquity towns is the presence of objective criteria, which can Ье estaЬlished through studies, and are applicaЬle for the differentiation itself. А part of the criteria used in the literature- administrative statute for example (Курбатов 1971, 80-115, 211-212; Dunn 1994, 60, 66; Poulter 1996, 118) demographic potential (Курбатов/ Лебедева 1986, 114) do not meet that requirement. Referring only to administrative statute reproduces the situatioп with the town definitions in the sources to а certain extent, while it does not provide а possiЬility to classify the towns, which '''ere поt provincial capitals. The demographic potential itself is important and objective index, but the actual state of the archeological research does not provide enough information to apply it directly as а basic criterion.

The town fortification was а known, but not а uЬiquitous case during the Principate. In the Late Antiquity, however, it became а necessary condition for а town life, or eYen its main symbol in almost all areas of the empire, including the Balkans (Ciaude 1969, 15-41,102,200-201,

1 Fог example"new ... small" towns (Ostгogoгsky 1959, 59); "small and Ьig" ог "small ... and Ьiggeг" , "Ьiggeг ... and smalleг", ог "smaii, ... Ьiggeг ... and most important", or as we\1 "not big", "standaгd" and 'Ъiggest" cities (Курбатов 1971, 7-9, 50-56, 61-71, 80-84, 98, 207-208); "small", "smaller'', "гelatively Ьig", "Ьig" ог "main"to .... ·ns (Velkov 1977,73, 85, 133, 219, 283-286); "gгandes villes" and "petites ' 'illes" (Duvai/Popovic 1980, 374, 378, 381, 396); "majoг" and "sma\1" towns (Potter 1995, 63, 66); " larger" and "largcst" towns, "other" and "ncw"- for the rest ofthe towns (Удальцова 1986, 21, 23, ЗО, 34-36); "major", "great", "big", "little", "small", "little country" or "modest towns" (Jones 1994, 238-239, 242, 249); "major", "gгeat", "largest", "smaller" and "small" cities (LieЬeschuetz 1996, 10, 31, 32) and so on.

39

Ventzislav Dintcl1ev

226; Velkov 1977,201 -220; Ravegпaпi 1983, 7 -46; Dagroп 1984, 6; Bavaпt 1984, 246; Курбатов/ Лебедева 1986, 135-137; Liebeschuetz 1996, 7-8; La Roca 1996, 163-165; Duпп 1997, 140-142). The measuremeпts of the late aпtique city fortresses are partly depeпdeпt оп the importaпce апd the poteпtia1 of the correspoпdiпg ceпtres 2 . These dерепdепсе was due поt опlу апd поt maiпly to the more pragmatic spirit of the time - coпsideriпg the great expeпses for а solid апd tactically souпd fortificatioп, апd the пecessity for а safer defeпce, which had become ап imperative for the fuпctioпiпg of the cities. Exceptioпs, coпsideriпg а probaЬle preseпce of mапу поt built up spaces iп the protected area respectively - provided а certaiп discrepaпcy between а larger area built апd more modest ecoпomic апd admiпistrative fuпctioпs апd demographic poteпtial could Ье assumed опlу for some ceпtres, whose пaturally protected terraiп allow "saviпg" the surrouпdiпg towп walls. The fact саппоt Ье missed, however, that а similar situatioп was а stimulus for developmeпt of these towпs maiпly because of the better possiЬilities for defeпce that it provided.З

Therefore, the size of the defeпded area of а certaiп late aпtique towп is ап objective iпdex for the пumber of its populatioп апd for its importaпce as ап ecoпomic, cult aпd/or military ceпtre4 • The size of the area defeпded is поt the опlу апd thus а uпiversal iпdicator but it is а commoп опе, which coпsideriпg the actual state of the study of the late aпtique cities has to Ье а basic criterion for their classification as well.

Hence the actual classificatioп of the late aпtiquity towпs should Ье estaЬlished оп the data for the size of their defeпded areas, апd when possiЬle the other objective iпdicators for their scale апd their importaпce, as well as data from the sources to Ье coпsidered.

The next proЬlem after choosiпg and subordinatioп of the criteria is the опе of specifying the parameters Iп some epitomizing puЬlications оп the cities iп the dioceses of Thracia and Dacia there are classificatioп suggestions, based оп the size of their defeпded territory. Iп one of them is noted that "а part Sirmium, les cites les plus vastes опt une enceinte qui egale ou depasse legerement 40 ha (Augusta Trajana, Odessos, Nicopolis ad Istrum,

2 During lhe Principale in some parts of 1he empire - in Gaul for example, there are cases when the prolecled areas consideraЬiy oulweigh lhe areas bui\1 in facl if lhe cily cenlres (e.g. Pellelier 1982, 37, 39, 44, 1 04) ln lhe Balkans and especia\ly in 1he easl pan of lhe peninsula lhe 1owns fonified during lhe Principate are wilh areas complelely bui\1 and prolected, and their size corтesponds 10 lheir demographic scale and 10 their imponance as administrative, economic and cultural centres. Among lhese whose fonress walls are wilh eslaЬiished routes, namely Philippopolis - 1he cull and cultural cenlre of the Roman Тlrracia, and Marcianopolis - lhe capilal of 1he Roman Moesia lnferior, are wilh largesl areas. An exceplion could Ье A11clrialos, bul lo prove il as such an exception unqueslionaЬic dala are needed. See lhc delails later in the texl and ir. fl .37. Ву lhe end of 3ns -4

111 century, actually in Gaul as we\1, lhe size of 1he prolected areas was already а prccise ref1ec1ion

of 1he demographic slandard and imponance of lhe lowns lhemselvc:s (Johnson 1983, 82-117; Maurin 1992, 365-370, 379-380; Harries 1996, 79-82).

3 ln lhat respecl lhere hard1y can Ье а more proper example lhan Acrae in the province of Scytlria. The terтain of Accrue- а саре in lhe sea wilh rocky coasts a\1owed а barrage wa\1 of 1ill1e more lhan 400 m longiludc an area of 15 ha to Ье defended . This lhird wall of Acrae refers 10 the second half of lhe 4

111 century (Джингов et а\ . 1990, 24-69). The s1udies of

lhe area prolecled Ьу it, ог especially in lhe area belween it and lhe second wall of Acrae are limiled for lhe lime Ьeing. Anyway, il seems lhat in lhe first decades afler building the extemal wa\1, in the area Ьehind il lhere rea\ly were large spaces nol buill up. ln 1he course of lime, however, lhis area. has Ьееn cullivated and built for sleady inhabitancy. An argumenl for lhis is provided nol only Ьу 1he remains of buildings discovered here, bul also Ьу the fact thal the early Chrislian necropolis here sludied partly was left afler 1he building of 1he extemal wall. The necropolis from 5111

- 6111 century is localized 10 have been several hundred melres away in fronl of lhe exlema1 wall (Кузманов 1979, 217-223; Тоnтанов 1984, 67-71; Джингов el а\. 1990, 69-70, Йосифова et а\. \995, 145-146; Йосифова/Радичков 1996, 1 05). Therefore, lhe possibility for а Ьigger extending and proteclion of 1he area slimulaled lhe increase of the population and 1he imponance of 1he lale anlique cenlre as а whole. Due lo this possiЬilily afler 1he middle of 1he 5

111 cenlury Acrae

\\•as already one of lhe imponanl cilies of the province of Scythia. 4 ln some puЬiicalions cenain reservalions have Ьееn expressed conceming 1he using of 1he size of the defended area as an

index for the size and lhe imponance of the lale antiquily 1own (e.g. Gregory 1982, 55-56). The examples studied themsel\'es refule these and suppon lhe dependence poinled already (Gregory 1982,44-45,62-64, fig. 1-3).

40

C/assification of rhe Late Antique Cities in tl1e Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

Scupi); Ulpiana est un peu plus modest (З5.5 ha); la plupart des cities ont un peu plus de 20 ha (Oescus, Bononia, StoЬi, Heraclea, Serdica, sans doute Naissus); avec ses 14 ha environ, Horreum Margi est une petite ville, et Remesiana (5.5 ha) est qualifie par Procope de 1tOAtXVtov" (Bavant 1984, 28З, n. 113). The quotation gives the impression of а Iarge classification model, but leaves the impression for unspecified c1assifications groups and/or unspecified parameters of the different groups. An idea of а reduced classification model is suggested in another puЬlication. Outlining that in the 4

1h century the size of the town

centers in the DanuЬian provinces depends on their administrati ve functions, the author accepts that in а defended area of about 1 О ha "seem to Ье closer to he norm for cities which do not act as provincia1 capitals" (Poulter 1996, 120). While in the first case there is incorrect information about the defended territory of а part of the pointed cities, in the second case the data for the cities which are not provincial capita1s and which are far over the defined standard are missed.

It is clear that when specifying the c1assification parameters modern standards should поt Ье а startiпg point.5 It should Ье takeп in consideration the regioпal specificity of the town апd settlement life in genera1 in the different parts of the empire. In that seпse, the identical princip1e of the c1assification of the late antique cities from differeпt regioпs - from the Balkaпs and North Africa for example, does not пecessari1y suggest identica1 parameters lt also has to Ье пoted that in the dioceses Тltracia апd Dacia there were поt cities of the rank of Antiocltia (Liebescпuetz 1972; Кеппеdу 1996, 181-195) or Thessalonica (Avramea 1976, 139-14 7; Spieser 1984 ), whose defeпded areas are calculated iп square kilome-

. h 41h 61h d h . tres ш t е - ceпtury, ап w ose Impor-taпce in the socia1 life of the empire competes

with that of Constantinopolis. 1 coпsider that today it сап Ье accepted а

three-stage c1assification model for the city centres in Thracia and Dacia: large cities, middle cities, small towns or centres of city type.

The classificatioi1 parameters 1 am suggestiпg for the different groups апd which are connected with the main criterion, are the following; а defended area of over ЗО ha for the Ьig city; а defeпded area betweeп ЗО апd 10 ha for the middle city; а defended area between 1 О апd 5 ha for the small towп. These parameters are поt occasiona1. They are а result of the iпterpolation of the data for the area of the cities and express the concept of the classificatioп itself. ln defining the Jower limit the data for the non-urbaп fortified settlements are considered, which are опе of the most characteristic pheпomena in the settlement 1ife in the late aпtique dioce~es of Dacia and Thracia in general (Diпtchev 1997а 47-63; Dintchev, im Druck).

As far as exceptions are usual for every classification model, it is expedient to iпtroduce larger distinguishing zones between the differeпt groups.6 1 define the parameters of these zones through an acceptaЬle deviatioп in two directioпs- а toleraпce, from the precisely fixed borders. The tolerance has different \'alues ascendiпg for differeпt zoпes . Thus 1 defiпe the border zone between the non-urbaп or semi-urban fortified sett1ements and the small towns Ьу usiпg а toleraпce up to 1 ha from the above mentioned border- 5( +1-1) ha, e.g. from 4 to 6 ha. The border zопе between the small and the middle towns comes out Ьу usiпg а to1-erance up to 1.5 ha- 1 О ( +/-1.5) ha, i.e. from 8.5 to 11.5 ha. The border zone between the middle апd the large towns comes out Ьу usiпg а tolerance up to З ha- ЗО (+/-3), i.e. from 27 to 33 ha.

When the territory of а certain ceпtre falls into the border zone, its referring to one of the correspoпdiпg groups happeпs with the help of the other objective criteria for а size апd im-

5 It is clear that according to modem standards almost alllate antique cities can Ье defined as sma\1 (e.g. Cameron 1996, 152-153).

6 The exceptiuns here do not inc1ude the specia1 cases, which ha,•e Ьееn discusscd аЬоvе. See ft .#З . Hcre 1 mcan the usual exccptions or deviations allowed for any simi1ar c1assification - for example relating Bergala or Tz:oides to the group of the small towns, although the defended territories of these centres are under 5 ha. Conceming the moti ves for defining Bargala and Tzoides as small towns see funher in the text

41

Ventzislav Dintchev

portaпce. Namely iпtroduciпg larger differeпtiatiпg zoпes provides the techпology of usiпg of other objective criteria: the пumber апd the type of the architectura1 comp1exes апd buildiпgs with puЫic апd private destiпatioп, апd the пature апd the amouпt of the movaЫe stock fouпd iп excavatioпs.

1 have meпtioпed that the Ьig cities iп

Thracia апd Dacia are поt amoпg the Ьiggest imperia1 ceпtres. From it does поt follow, however, that the defiпitioп of the former must Ье chaпged. It shou1d Ье specified iп that case the maiп proviпcia1 towпs iп Thracia апd Dacia are coпsidered. Iп what other way except as а Ьig city cou1d Ье defiпed Philippopolis, for examp1e, whose defeпded area is (at 1east uпti1

th the secoпd quarter of the 6 ceпtury) "оп1у"

about 80 ha (Матеев 1993, 91 ), whose popu-1atioп is estimated to have Ьееп about 100 ООО реор1е (Кесякова 1985, 119), апd whose importaпce registered iп the sources (Velkov 1977, 128) is categorically coпfirmed Ьу the archeo1ogical fiпds (Botoucharova/Kesjakova 1983, 264-273; Данов 1987, 169-177; Кесякова 1989, 113-126; Кесякова 1994, 192-204; Матеев 1993), or Odessos whose territory is "опlу just" of 43 ha, апd whose popu1atioп iпcreases iп 51

h - 61h с. with the iп

flux of immigraпts from the easterп proviпces of the Empire (Ve1kov 1961, 655-659; Бешевлиев 1983, 19-35; Минчев 1986, 31-43), апd whose importaпce cu1miпates iп the 61

h ceпtury with its e1ectioп for capita1 of the pecu1iar questura exercitus, iпc1udiпg territories from the Ва1kап peпiпsu1a, Asia Miпor, and a1so Cyprus апd the Cyc1adic Is1aпds (Szadeczky-Kardos 1985, 61-64; Torbatov 1997, 78-87).

Together with Philippopolis and Odessos, Marcianopolis - the capita1 of the province Moesia lnferior, is a1so а Ьig towп in the 1ate Antiquity. The fortification system of Marcianopolis iп the iпitia1 part of its research bears witпess for that. The preseпt informatioп about its defended area - about 70 ha, correspoпds to а greatest exteпt to the епd of the 3rd

- 41h с. wheп, accordiпg to the sources, its im

portance iпcreased extreme1y (Gerov 1975, 66-68, 70-72; Ve1kov 1977,99, Miпcev 1987,297-299). Ап evideпce for this are the iпitia1 datiпg of the most represeпtative bui1diпgs and comp1exes discovered there. However, the archeo-1ogica1 research demoпstrates that the city remaiпs а sigпificant ceпtre iп the followiпg ceпturies as well (Gerov 1975, 49-55; Топсеvа 1981, 138-143; Miпchev 1987, 299-306; Ангелов 1990, 202; Минчев/ Ангелов 1991, 111-112; Ангелов 1996, 61)

Tomis is undoubted1y а Ьig city too - it is the capital апd the metropo1itaп's ceпtre of the proviпce of Scythia. lts importaпce is registered not оп1у опее in the 1ate aпtique sources (lorgu 1961, 271-274; Velkov 1977, 107; Harreither 1987, 197-210; Barnea 1991, 277-282; Suceveaпu/Barпea 1991, 195-197, 289-290). Iп Tomis а 1ot of 1ate antique bui1diпgs have Ьееп studied - Christiaп basi1icas, representative bui1dings with mosaics, thermae etc. lts defeпded area, which was increased consideraЫy iп comparisoп with the previous period, may have reached 55 ha. It is assumed that the southwest sector of the fortress is an additioп from the begiппiпg of the 61

h с. (Bucova1a 1977; Che1uta-Georgescu 1977, 253-260; Radulescu 1991, 23-35; Succeveavпu/Barnea 1991, 270-271, 274-275, 283; Sampetru 1994, 74-76; Radu1escu 1998, 83-93).7

The developmeпt of Serdica is of interest. In the 2nd с. its defended area was about 18 ha. Ву the епd of the 3rd - the begiпning of the 41

h

century Serdica, which was a1ready the capita1 of the new proviпce of Dacia Mediterranea, had а sigпificant upheava1 c1ear1y reflected in its representative architecture (Velkov 1977, 93-94; Stanceva 1989, 107-122; Велков 1989, 23-26; Станчева 1989, 17-20; Бобчев 1989, 37-58). A1so at the end of the 3rd_ 41

h ап iшperia1 mint court functioned in Serdica (Божкова 1977, 3-1 О, Капели 1983). Now the town received а new fortress as well, whose territory is much larger than the one of the Roman fortress (Бояджиев 1959, 38-41, 45;

7 The figure given for the defended area of the late antiquity Tomis is а result of approximate calculations after the plans in the quoted puЬiications. In the latter precise data for the territory are not given.

42

Classificarion of rhe Late Antique Cities in rhe Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

Григорова 1983, 24; Станчева 1989, 18-19). Coпsideriпg the magпitude of its whole protected territory iп the 4th с. - about 84 ha (Тонев 1995, 1 02). Serdica exceeds Tomis, Marcianopolis апd еvеп Philippopolis. It is поt Ьу сhапсе Ammianus Marcellinus, who is reliaЬie iп his iпformatioп, calls Serdica together with Philippopolis "kпown and vast cities" (ЛИБИ, 1958, 133). Such а city was in fact Serdica, but поt for loпg - at latest iп the middle of the 5th ceпtury the fortificatioп system of the late Romaп eпlargemeпt is left апd the city shriпks agaiп to the limits of its defeпded territory from the 2nd с. А similar chaпge happeпs to the capital of

the late aпtique proviпce of Thracia -Philippo-1юlis, but duriпg the reigп of Justiпiaп 1. The пеw fortress wall, which was moved to the Three-Hills, i.e. to the old acropolis ofthe city, reduces its defeпded area with over 50%. The remaiпs of the agora complex - the пucleus of the апсiепt structure of Philippopolis, апd a1so its episcopal basilica from the first half of the 5th с. are 1eft out of the new city fortress (8otusarova/Kesjakova 1983, 271-273; Морева 1988, 130-138; Матеев 1993, 92-93; Кесякова 1989, 122-124). Еvеп after а coпsideraЬie reductioп the defeпded territory of Philippopolis is поt less thaп 35 ha8

.

А Ьig towп iп the proviпce with the same паmе iп the diocese of Thracia is Augusta Traiana. Its walls take ап area of about 48.5 ha еvеп iп the 6th ceпtury, апd the пumber of the r~preseпtati\1e, private апd puЬiic uпits iп its late aпtique structures is two-figure (Niko1ov 1987, 96-1 07; Калчев 1992, 49-69; Николов/Калчев 1992, 29-44; Янков 1993, 139-143, 145-148; Буюклиев et а1. 1994, 89-90, Kaltscl1ev 1998, 88-1 07).

Scupi - the capital of the proviпce of Dardania, whose defeпded territory goes Ьеуопd 40 ha, сап Ье referred as well to the Ьig

late aпtique towпs. The represeпtative puЬiic апd private buildiпgs fouпd duriпf its excavatioпs, coпfirm its importaпce iп 4t апd 5th ceпtury. After the begiппiпg of the 6th с., however, Scupi lost поt опlу its privileged admiпistrative positioп, but a1so it town character. It is assumed that the reason is an earthquake in 518 (Miku1Cic 1973, 29-33; Micu1cic 1974, 208-210; Корачевик 1977, 143-177; Гарашанин/Горачевик 1984, 79-97; Корачевик 1988, 155-164 ). lf that is the date of the fatal turпiпg poiпt, theп the defiпitioп of Hiиocles - I:кou1tOIJ.Т)'!p01tOAt~ (ГИБИ 1959, 94) is а reminisceпce поt correspoпding to rea1ity. ProbaЬly а part of the fuпctioпs of the o1d town were inherited Ьу the пew1y-built ceпtre iп the 6th с. оп the поt far hill of Markovi Kuli. The 1atter impresses with its powerfu1 fortification iпc1uding а citade1, iпterпa1 апd externa1 fortress (Miku1cic 1973, 33-34; Mikuicic 1974, 210-212;Микулчик 1982,48-53, 129-135; Микулчик/Билбиjа 1984, 205-221 ). Its defeпded area cou1d have hardly outstood 6-7 ha 9 .

The data for the south wall of the late aпtique fortress of Scodra, studied receпtly, are iп fact the first more sigпificaпt archeological data for the capital of the proviпce of Praevalirana. Iп the construction of the wall two periods have been distinguished: from the end of the 4th- the beginning of the 5th с.; from the time of Justinian I (Hoxha 1994, 231-24 7).10 The layout of the wall and the topographical plan presented (Hoxha 1994, 232, fig.l) allow to Ье assumed that the defended area of the late antique town was not less than 35-40 ha.

Messembria, although Hierocles did not mention it, was possiЬiy the most prosperous centre of the proviпce of Haemimontus in 5th and 6th century. Today at least one-third of tl1e territory of the town, which is а Black Sea ре-

8 The layout of the cxtemal early Byzantine wal\ of Pllilippopolis has not been estaЬ\ished everywhere.

9 The layout of its intemal wall has not becn cstaЬ\ishcd completely, but it can Ье assumed from the sectioпs studied and from the configuration of the terтain (e.g. Mikulcic 1974, 211, fig.8) that this wal\ does not encompass а tcrтitory Ьiggcr than the above mentioned.

10 The dating of the two pcriods are after al\ based on common building analogics and historical presumptions, i.e. they are not unquestionaЬ\e.

43

Ventzislav Dintchev

ninsula, is under the sea level, but the preserved parts of the town itself are about 25 ha. In Messembria solid walls and fortresses, several large Christian basilicas, puЬlic thermae and many other buildings and appurtenances

th th . from the 5 -6 century have been studted (Bojadziev 1961, 321-349; Venedikov et al. 1969; Velkov 1981, 137-141;Чимбулева

1988, 577-585, Теоклиева 1988, 585-593; Ognenova 1988, 5700-573; OgnenovaMarinova 1992, 243-246).

Ulpiana in the province of Dardania, whose defended area is 35.5 ha, is also among the Ьig Balkan centres of the late antiquity. During the reign of Justinian I it was renamed in lustiniana Secunda (Duval/Popovic 1980, 381-382; Паровиh-Пешикан 1982, 57-72; Bavant 1984, 247). Considering its characteristics the so-called castrum - а fortress with an area of about 16 ha in а close proximity to the city wall, is of special interest. The studies confined so far to the castrum in question give certain reasons for its dating to the 6th century (Паровиlj-Пешикан 1982,59,61,71-72). The synchronous function of the old and the new fortress in the 6th с. could mean that Ulpiana increased the number of its population as well as its importance as а settlement and puЬlic centre in general.Н However, it seems to me

that the possibllity the new fortress to have appeared as а consequence of abandoning the previous, i.e. for replacing and reducing the defended town area is more proper. 12

The fortress of the Roman Colonia Ulpia Ratiaria is supposed to have been with measurements of 426 х 284 m (Giorgetti 1987, 40-42), i.e. with an area of about 12 haP In the end of the Зrd- the beginning ofthe 4th с. when Ratiaria is already the capital of the province of Dacia Ripensis, а new and much Ьigger town fortress was built. Apart from the rectangle of the earlier fortress, it also includes new territory southwards and eastwards, and its walls follow the configuration of the terrain here.14 The area of the late antique town defended in that way is about 30-35 ha.15 Most of the studied building~ in Ratiaria, including а representative residence . th th tn the town centre, are also from 4 -6 с.

(Velkov 1985, 886-889; Atanasova/Popova 1987, 85-96; Giorgetti 1987, 33-85; Джордети 1988, 30-38; Kuzmanov, in print).

Among the most important new centres in the Balkans in the beginning of the Late Antiquity is the town near Grazhdani (in Albania now) unidentified so far. It is near the border between the Dacian province of Praevalitania аг d the province of Epirus Nova of the diocese of Macedonia 16

. Its defended area is 34 ha. Its

11 The hypothesis that the castrum at issue "whose remains are 80-1 ОО m eastwards from the walls of U/piana" (ПаровиhПешикан, 1982, 61) could Ье identified with /ustianopolis mentioned Ьу Procopius (Па рови!\ -Пешикан, \982, 72), i.e. the hypothesis for two different city centres -U/piana/lustiniana Secunda and /ustianopolis in such а "close proximity, is definitely unacceptaЬ\e.

12 Such а possibility could Ье supported Ьу the interpretation of Pricopius' information that Justinian ·'pulled down most of the ring wall" of U/piana, as "it was almost completely ruiпed and entirely useless" (ГИБИ 1959, 157). The chronology of the few buildings exposed in Ulpiana, as well as the studied northem gate of its older fortress has been proЬiematic so far. (Bavant 1984, 247-248, n.l4).

13 So far only the central area of the west \\•all and the main gate (Atanasova/Popova 1987, 85-96) have been studied. The measurements suggested аЬоvе are а result of the analysis of air photos (Giorgetti 1987, 40).

14 Confined parts of remains of the south and east late antique wall have Ьееn found accidentally. 1 received the information from У. Atanasova, for which 1 am deeply grateful. 1 also did personal observations of the terrain during my participation in the excavations of Ratiaria from \987 to 1989.

15 ln the earlier puЬ\ications the territory of the Iate ancient Ratiaria \\•as defined to have been 1,5 х 0,3 km, i.e. 45 ha (Velkov 1966, 173; Claude 1969, 18, n.42; Moscy 1970, 101; Biemacka-Lubanska 1982, 226). These data, however, are from before the starting the regular excavations. Considering the Iayout of the central part of the west town wall and the position ofthe main gate, which had not Ьееn changed from the end of \

51 to the end ofthe 6111 с. (Atanassova/Popova \987, 85-96),

and in view of the configuration of the terrain the maximum of the defended territory of the Jate antiquc town was about 35 ha. The assumption of а separate late antique military camp within an area of 0,6 ha in northwest direction from the I0\\'11

fortress (Georgetti 1987, 45-56, tav. А) has not becn confirmcd so far.

16 The hypothesis for the name of this town to have been Dober (Васе 1976, 49, n.21) is not based on the late antique sources. The frontier Ьetween the two provinces and between the two dioceses in the region is uncertain.

44

Classification ofthe Late Antique Cities in the Dioceses ofThracia and Dacia

2760 m long wall is in opus mixtum with courses of three or four rows of bricks. The 40 towers found alongside it are U-shaped (Васе 1976, 48-49, 70, tab. 3; Popovic 1984, 201). These peculiarities allow admitting that in the middle of the 4

1h century this centre was func

tioning or at least it was being built. Due to the limited so far studies its destiny in the next centuries is unknown.

An ald urban centre in the province of Scythia, mentioned in the sources, as after its capital is Dionysopolis. The archeological data f . f ь . . 41h 51h . 1 d" . or 1ts state о ешg ш - с., ше u шg 1ts area are scarce (Димитров 1986, 95-98), but they prove its importance and suppose its classification as а major city. In the first half of the 61

h с Dionysopolis suffered а great earthquake. Ву the middle of the century the town was rebuilt on а new territory and was provided with а powerful fortification (Димитров, 1985а; Димитров 1985Ь, 123-124; Димитров 1988, 71-74). As for the area of the new town the figure of 26 ha has been pointed (Димитров1985а, 14; Димитров 1985Ь, 124), or even 36 ha (Димитров 1988, 72, 75). In view of the irregular shape of the fortress and the overalllongitude ofits walls - 1730 m or 1735 m (Димитров 1985а, 14; Димитров 1985Ь, 124) the defended territory of the new town could have hardly exceeded 16-17ha.

The studies of Viminacium - а municipium from the 2"d с. and capital of the late antique province of Moesia Superior are based mostly on written and epigraphic sources (Поповиh 1967, 29-41; Mirkovic 1968, 56-73; Поповиh 1988, 31-35; Mirkovic 1997, 44-50). Anyway, today the localization of the military camp and of the Roman Municipium Aelium Viminacium is known. According to some information from the beginning of the century, quoted in the later puЬiications (Поповиh 1967, ЗО; Petrovic 1986, 93) the military camp is with measurements of 442 х 385 m, i.e. with an area of 17 ha. А wall built or at

least reconstructed in the Late Antiquity, is now have been known in the east part of he city structure as wellP According to the known plans (Поповиh 1967, 33, 39, fig. 4, 5; Поповиh 1988, 2, fig. 1) the area of the town structure as а whole is at least twice as Ьig as the one of the camp. The latter, in analogy with the other Roman legionary camps in the DanuЬian region must have borne significant transformations in the end of the зrd - the beginning of the 4th с., and should Ье accepted as а part of the city structure in the 4th century. Having this addition it is sure that the whole defended area of Viminacium in the 4th с. exceeded ЗО ha. The city was badly affected Ь~ the Hunic invasions in the middle of the 5

1

century. In the literature the thesis that in the first years of ruling of the emperor Justinian 1 its fortified nucleus was moved to about 1 km westwards from the previous town fortress has been maintained (Поповиh 1988, 1, 32-35). Another object connected with the destiny of Viminacium in the 61

h с. is а settlement of foederati, localized at several hundred metres northwards from the old town fortress (Поповиh 1988, 1-31, 33-35). The new fortress which is identified with the early Byzantine Viminacium is with an area of "only 2 ha" (Поповиli 1988, 33). Due to it the thesis itself about the moving and reducing the capital of Moesia Superior up to his fortress together with the above mentioned settlement fortified weakly does not seem acceptaЬie to me. At least а part of the old town fortress probaЬiy must have been used in the 6

1h cen

tury. Otherwise Viminacium would have been one of the drastic examples of discrepancy between sources and real parameters of size and importance at that time.18

According to the accepted classification parametres in the bordering zone between the Ьig and the middle towns is Diocletianopolis in the province of Thrace. The defended territory of the town built in the end of the зrd - the beginning of the 41

h is about ЗО ha. The many

17 The thickness of 3.40 m of this wall (Поповиl\ 1967, 33-34) was hard1y reached Ьefore the end of the 3nJ с.

18 Apart from Hierocles, who points Vimi11acium as JlE'tp07tOЛ.н; of Moesia Superior (ГИБИ 1959, 54), Procopius a11d Theophilactus Simokatta (ГИБИ 1959, 164, 293, 348-350) inform as well aЬout the importance of the town in the 6111

century.

45

Ventzislav Dintchev

studies iп Diocletianopolis, iпcludiпg iп the suburbs апd iп its пecropolis, complexes апd buildiпgs-resideпces, Christiaп basilicas, thermae, barracks etc. prove its importaпce апd are ап argumeпt for its defiпiпg as а Ьig late aпtique city (Gorbaпov 1987, 293-296; Иванов 1988, 27-30; Маджаров 1993; Маджаров 1995, 99-1 ОО; Маджаров et al. 1996, 57-58).

Pautalia iп the proviпce of Dacia Mediterranea is iп the border zопе betweeп the two groups too. The defeпded still iп the 2nd ceпtury area of this city is calculated to have Ьееп а little more thaп 29 ha. Here mапу late aпtique buildiпgs with differeпt fuпctioпs also have Ьееп studied. Some of them impress with their coпstructioп апd decoratioп (RusevaSlokoska 1987, 82-96; Слокоска 1989; Генадиева 1989, 157-173; Фъркав 1990, 147-153; Алексиев 1991, 120-121; Мешекав 1996, 57-58). Оп the пеаr hill of Hissarluka iп the 41

h с. а fortress was built with ап area of 2.1 ha (Гочева 1970, 233-254; Слокоска 1989, 13, 33-34; Станилов et al. 1991, 178-179). lt also coпtributes to the classificatioп assessmeпt of Pautalia as а Ьig city19

• А пewly discovered wall, hov.-·ever, which divides the defeпded towп area (Сnасов et al. 1996, 39-47), sets iп questioп such assessmeпt ofthe last period of the Late Aпtiquity апd directs towards the assumptioп for chaпges iп the developmeпt of Pautalia, similar to the chaпges iп Serdica or Pbllippopolis for example 20.

Singidunum iп the proviпce of Moesia Superior, Aquae апd Oescus iп the proviпce of Dacia Ripensis are iп the border zопе betweeп the two classificatioп groups as well. The ех-

istiпg iпformatioп about these ceпtres does not allow, however, their defiпiпg as Ьig cities in the Late Antiquity.

The maiп fortress of the late aпtique

Singidunum keeps the outliпes of the earlier Romaп military camp. It circles about 20 ha. With the defeпded exteпsioп iп northwest directioп - the so-called dowп towп, the entire defeпded area must have reached ЗО ha. The more represeпtative buildiпgs estaЬiished earlier are, however, relatively few, and most of them are from the2nd - the first half of 3rd с. (Поnовиl) 1982, 27-37; Bojovic 1996, 53-68; Popovic 1997, 1-19; Vujovic 1997, 169-178). Singidunum was seriously damaged iп the iпvasioпs iп the епd of 41

h- the middle 51h с. (Bje

lajC/Ivaпisevic 1993, 123-139). It is supposed that duriпg the reigп of the emperor Justiпiaп 1 its defended area was coпfiпed опlу to the northwest third of the earlier major fortress, i.e. to 6-7 ha (Поnовиh 1982, 34-35; Bojovic 1996, 68; Popovic 1997, 17-18). It means that Ьу the middle of the 61

h с. Singidunum is already under the parameters of еvеп а middlesize and middle importaпt towп.

The assumed outlines of the walls of the late aпtique Aquae circle ап area of about 29 ha. The researches there have Ьееп coпfiпed so far (J анковиh 1981, 43-45, 81; 121-128; Петровиn 1997, 123-125). As ап indication for the limited importance of Aquae - considering the general classificatioп, the 11 1

h novela Ьу the emperor Justiпian should Ье iпterpreted. Accordiпg to it the local Ьishop was uпder the guardiaпship of the Ьishop of Meridium uпtil 535 (ГИБИ 1959, 49)?1 А reductioп of the

• th th protected area of Aquae ш the late 5 - 6 с. -

19 Although it was separated from the town fonifying system - to several hundred meters southwards, this military fonress рrоЬаЬ\у '"'as in unquestioned connection with the defence and \\'ith life in Pautalia in general. ln the opinions if the researchers of the fonress on the hil\ of Hissarluka а tendency has Ьееn noticed to an early dating of its appearance "the end of the 4

111 - the beginning of the 5th с." (Гочева 1970, 252); "in the 4111 с." ( Слокоска \989, 34);" the Ьeginning of

4111 с." (Станилов et а\. \991, 179).

20 ln the puЬiication the wal\ in question has Ьееn related to the period from 5111 to 9111 с. in general (Сnасов et а\. 1996, 44-45). There is stated again that the remains registered in the excavated sector '"'hich preceded the development of the wa\1 are dated "not earlier than 4

111 -5"' с." (Сnасов et а\. 1996, 44-45). According to oral infonnation Ьу R. Spasssov, for

which 1 am grateful, the most рrоЬаЬ\е date for the appearance of this wall is Ьetween the cnd of the 5111 - the Ьcginning of

the 7111 с. With the appearance of the latter the east half of the town area defended ear\ier \\'ЗS abandoned.

21 А similar indication is the dcfinition of Aquae Ьу Procopius -1tOAtXV\OV (ГИБИ \959, 166). However, in Pюcopius Aquae is а ccntre of а rcgion whcre many fonifications were reconstructed (ГИБИ 1959, 163).

46

Classificarion of rhe Lare Anrique Ciries in rhe Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

similar to Viminacium and Singidunum, would not Ье surprising.

Ву the end of the Зrd - the beginning of the 4th с. the defended area of Oescus had been enlarged and reached 28 ha. The archeological excavations have а long history, but their results are connected mostly with the Roman period of the development of that centre - with Colonia Ulpia Oescensium (lvanov 1987, 7-60; Kabakcieva 1996, 95-117;Иванов/Иванов 1998). The little number of representative buildings, constructed Ьу and after the beginning of the 4th с. in the sectors studied, tips the balance toward ranking the late antique Oescus among the middle in their size and importance towns. There are some facts that set under question the preserving the above mentioned area of Oescus until the end of the Late Antiquity 22 .

Among the most important centres belonging to the group of the middle towns is Novae in the province of Moesia lnferior. Ву the end of the Зrd century its defended area was extended to about 26 ha.23 The extensions indicate the transformation of the old military camp into а urban centre. The known so far about the late antique structure of Novae, includinf the impressive episcopal complex from 51

h - 61 с., confirms its role in the region of the Lower Danube (Press/Sarnowski 1991, 229, 240-243; Cicikova 1994, 127-138; Димитров 1994, 83-87; Parnicki-Pudelko 1995; Bier-

nacki/Medeksza 1995, 9-23; Kalinov.rski 1995, 25-35; Kudeva 1995, 27-61; Miltscheva/Gen tscheva 1996, 190-193; Dyczek 1997, 87-94).

Among the most important centres of this group is also Doclea in the province of Preavalitana. According to the general plan presented in puЬlications (e.g. Миjовиh/

Ковачевиh 1975, 43 fig. 37) its defended territory was about 25 ha. The research shows that Doclea was ап important centre - with а representativeforum and different puЬlic buildings, still in the time of the Principate. The representative Christian buildings of cult prove its importance in the Late Antiquity (Миjовиh/ Ковачевиh 1975, 42-46, 64-65; Duval/Popovic 1980, 379-380; Popovic 1984, 193, 207).

Hierocles did not mention Sozopolis, like Messembria, but it also was а prosperous town of the province of Haemimontus in the 5

1h-6

1h

century (Dimitrov 1988, 497-501 ). Sozopolis (the old Apollonia) has а similar disposition -on а Black Sea peninsula, encompassed Ьу а wall. Its territory was apprщimately as the preserved parts of Messembria today - i.e. about 25 ha.24 The limited so far researches in Sozopolis found remains of fortification and Christian cult architecture from the late 4

1h -

61ьс. (Велков 1964, 43-54; Овчаров/ Дражева 1987, 232-233; Дражева/Недев 1994, 11 0)?5

22 The area of Oescus 1, i.e. of the main fortress is delineated Ьу а circle ditch (Иванов/Иванов 1998, 58, обр. 25). Today traces of this ditch can c\early Ье seen from the east part of Oescus 1 (Иванов/Иванов 1998, 70), i.e. from the side of the late Rornan extension Oescus 11. This is а reason for supposition that the ditch was made after abandoning the fortress of Oescus 11. ln two of the t0\\1ers of the fortress of Oescus 11 а Iarge numЬer of coins from the second half of the Зrd - 4\h с., inc1uding from the \ate 41h с. was found. ln one of these towers а coin of Justinian 1 was found (Иванов/Иванов 1998, 71, 76, 80). The latter, however, was not found in а definite Iayer, which сап Ье connected with the functioning of the corresponding tower. The absence of Iater reconstruction and corrections of its appurtenances Ьears witness for the relatively short period of using the fortress of Oescus 11. These data direct us to the assumption that the early Byzantine Oescus, like Serdica, abandoned its fortified Iate antique extension, whose area is aЬout 10 ha. There has Ьееn а hypothesis that the ditch mentioned аЬоvе dates back to 10\h - 12\h с. (Poulter 1983, 76). E''en such а possibllity could not refute the аЬоvе mentioned assumption.lfthe ditch "''as medieval, it obviously \\'as conforrned to the remains ofthe fortress visiЬie at that time (Иванов! Иванов 1998, 58, fig. 25), i.e. with the fortress of Oescus functioning in the last period of the Late Antiquity.

23 Some puЬiications define the defended area of the Iate antique No,,ae to have been aЬout ЗО ha (e.g. ёicikova \980, 57; ёicikova 1994, 127). According to the known general plan (ёicikova 1980, 56, АЬЬ. 1) the area of Novae 1 and No,•ae 11, i.e. the late antique Nо\'йе is definitely smaller: Novae /, i.e. the earlier military camp, does not exceed 18 ha, and Novae 11, i.e. the extension, is about 8 ha.

24 Тhе peninsula of Sozopolis, in difference with the one of Messembria has not changed significant1y its configuration after бlh с. (Dimitrov 1988, 497-498).

25 Remains of the late antiquity Christian basilica are studied on the island of St. lvan, severa1 hundred metres а\\·ау from Sozopolis (Димова et al. 1990, 194-195).

47

Ventzislav Dintchev

lblda iп the proviпce of Scythe also is missiпg iп Hierocles, but it was meпtioпed as лоЛ.н; iп Procopius (ГИБИ 1959, 170). The defended area of this пеw ceпtre was also calculated to have Ьееп 24 ha оп the whole, апd the proportioп of its two соппесtеd fortresses is approximately 7:1. The аЬsепсе so far of excavatioпs causes certaiп disseпsioпs amoпg the researchers сопсеrпiпg the sequeпce iп the fortificatioп coпstructioп, but at least coпsideriпg the арреаrапсе of а Ьig fortress it is agreed that it dates back to the earlier or middle 41ь ceпtury (Scorpaп 1980, 40-41; Suceveaпu/Barпea 1991, 204 ). Iп that fortress the remaiпs of а represeпtative, three-apse Christiaп basilica from 61ь с were fouпd Ьу accideпt. Iп the surrouпdiпgs а late aпtique moпastery complex has Ьееп studied (Luпgu 1997, 100-1 О 1, 1 05).

А пеw towп, probaЬly а successor of ап ear-1ier military camp, is Bononia iп the proviпce of Dacia Ripensis (Susiпi 1975, 425-429; Velkov 1977, 88), meпtioпed Ьу Hierocles. The fortress of Bononia kпоwп todayJ whose coпstructioп dates back to the late 3r - early 41

h с., eпcompasses ап area of about 23 ha. The researches here are coпfiпed, but still they prove ап iпteпsive life iп the late aпtiquity, апd especially iп the 41ь с. (Атанасова 1974, 337-338, 343; Николаева 1990, 71; Атанасова, iп print).26 А brief аппоuпсеmепt about а studied пecropolis from 61ь с. in the north-east corner of the fortress (Михайлов 1961, 4), however, leaves the question of the fate of the fortress at that time ореп.

The yet uпideпtified ceпtre, whose remaiпs are uпder today's towп of Obzor, is the most importaпt poiпt оп the Black Sea coast of the diocese of Thracia betweeп Odessos апd

MessembriaP Accordiпg to the data апd р1ап kпown (Шкорnил 1930, 205-206, fig. 6), its defended area with the shape of а trapezium, is about 22 ha.28 The coпstructioп of the fortress, which actually marks the begiппiпg of the towп period iп the developmeпt of that ceпtre, was iп the late Aпtiquity. The shape of the towers directs to the late 31ь -4 1ь с. The coппection of the fortress with the so-called Balkan barrier line (Шкорпил 1930, 204-207) supposes the functioning of that ceпtre еvеп iп

lh lh the late 5 - 6 с. Its water supp1y was secured through external masoned waterpipes (Шкорnил /Шкорnил 1892, 40-41 ;Шкорnил 1930, 206). An indication for its town image are the late antique representative remains and finds discovered in the excavatioпs which have been limited so far to its defended area, or found Ьу chance (Шкорnил/Шкорnил 1892, 39-40; Овчаров/Ваклинова 1978, 32-33, 37; Чимбулева/Балабанов 1979, 94-95)29

.

The fortress of Traianopolis - опе of the main towns of the province of Rhodopa (Velkov 1977, 125), is of irregu1ar shape similar to а pentangle, апd the overall length of its walls about 2 km (Pantos 1983, 173). From this information it сап Ье concluded that the defended area of the late antique Traianopolis was approximately as the опе of Bononia in the 41ь с. or as the опе iп the centre of today's Obzor.

Iп the 41ь and the first half of the 5 1ь с. Nicopolis ad Istrum iп Moesia Inferior keeps its defended territory of about 21.5 ha, outlined still Ьу its first wall from the 2nd с. In the first half of the 41ь c.most of the importaпt puЬlic units of the urban structure iпcluding the agora

26 1 would like to thank Mrs.Atanassova for giving me to use her article under print.

27 The only hypothesis concerning the identitication of that centre belongs to brothers Shkorpil: it is with the road station of Тетр/шп Jovis known from Tabula Peшingeriana (Шкорлил/Шкорлил 1890, 14; Шкорлил/Шкорпил 1892, 36; ЛИБИ 1958, 17). It can hardly Ье assumed that the name Тетр/щп Jovis was used Ьу and after the middle of the 4

111 с. lf the Ьorder Ьetween Moesia /nferior and Haemimontus was the main ridge of Haemus, then this centre should have been the farthest southeast point in the province of Moesia lnlerior.

28 The data Ьу K.Shkorpil are in feet. The calculations are done Ьу my in the following proportion foot : metre = 3:4. Thus the perimeter of the fortress of this centre, which is 2700 feet (Шкорлил 1930, 206), makes 2025 m.

29 А concluding report, yet unpuЬiished, for the building remains and architectural details from the Late Antiquity found here was delivered Ьу Zh. Chimbuleva during the sessions of the 4

111 conference Bulgaria Pontica Medii Aevi, held in

1988.

48

Classification of rhe Late Antique Ciries in the Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

complex functioned. At that time new representative residential buildings appear, and the suburbs extended (Иванов/Иванов 1994; Русева-Слокоска 1994, 171-181; Poulter 1995, 28-33; Rousseva-Slokoska,

f lh 205-211). А ter the 4 с, and mostly after the middle of the 5

1h с . , however, iп the develop

meпt of Nicopolis ad lstrum drastic chaпges occur. They fiпd their expressioп iп the removiпg апd reductioп of its defeпded area to 5.74 ha.30 The most importaпt uпits iп the structure of the пеw ceпtr~ are two buildiпgs of а cult - а

three-пaves basilica апd а опе-паvе church (Poulter 1995, 35-47). Their constructioп ,

measurements and decoratioп, however, do поt provide them а place among the more represeпtative exemplars of the correspoпdiпg architectural types. Iп that case the defiпiпg of the early Byzaпtine Nicopolis ad lstrum as а towп is proЬiematic, or will Ье conditional with а lot of reserves .

Naissus, whose towп status probaЬiy dates back to the епd of the 2nd с. is the most important centre of the \vesterп part of the proviпce of Dacia Mediterranea . Apart from the sources, а proof in that respect are the buildiпgs, appurteпaпces апd fiпds of the Late Aпtiquity discovered here (Петровиh 1976, 9-88; Petrovic 1993, 57-69; Gusic 1993а, 164-168; Mirkovic 1997, 51). The outlines of the walls have not been surely estaЬlished so far, but it is supposed that its defended area was about 20 ha (Петровиn 1976, 49; Petrovic 1993, 66)

The localizatioп of the Zaldapa meпtioпed Ьу Hierocles was specified recently (e .g. Бешевлиев 1962, 1-3). The information about the corresponding site proves Zaldapa to have been the most significaпt пеw centre iп the south part of the proviпce of Scythia. Accordiпg to iпformation апd to а рlап from the beginning of the century (Шкорпил 1905,

493-499, pl. CXI/c), the area defended Ьу а strong fortress is about 20 ha.31 It сап Ье assumed from the iпformatioп about the walls апd towers that the begiпning of the towп was not later thaп the middle of the 41h с. According to unpuЬlished researches Ьу К.

Shkorpil here the remains of а represeпtative buildiпg, 1 ОО m loпg, апd of а Christiaп basilica are found (Въжарова 1961, 66). The water supply of Zaldapa was safely provided (Мирчев 1951, 99-102).

Durostorum is а well-kпowп ceпtre of the proviпce of Moesia lnferior апd of the Lower Daпube iп geпeral (Velkov 1960, 214-218; Tapkova-Zaimova 1997, 1 09- 114; Sousta1 1997, 115-119). It is supposed that the measuremeпts of the Romaп mi1itary camp here were about 480 х 400 m, i.e. а territory of 19 ha. The explored southwest sectioп of the camp fortre$S was kept апd rebuilt to the 6

111 с. The traпsformiпg of the camp iп а settlemeпt centre has also Ьееп proved, i.e. the situatiпg of the towп iп the area of the ear1ier camp. Iп the beginniпg of the 41h с. iп the place of the Romaп canabae а suburb with represeпtative buildiпgs is estaЬlished (Donevski 1987, 239-243; Doпevski 1994, 153-158; Доневски 1995, 259-270). At the same time пеаr the Danubian Ьапk - а few hundred metres northwest from the former camp, а пеw (military ?) fortress was built. In the sixth ceпtury this fortress was generally recoпstructed (Ангелова 1980, 5-8; Ангелова 1988, 33-36), lts walls so far have поt been outliпed, but it сап Ье assumed that its area is not less than 3-4 ha.

Ап old towп centre in the proviпce of RIJOdopa is Maroneia . It is mentioпed Ьу Hierocles (ГИБИ 1959, 88). Accordiпg to the plaпs puЬlished (Ла~арtЬТJ<; 1972, fig.37 ; Bakirirtzis 1989, fig . 16) its defeпded area iп the 41h-61h с. should have been about 19 ha32

. In

30 According to the researcher the new fortress was built in 453 (Poulter 1995, 37). 1 think that а later date of its building - Ьу the end of the 5111 or the beginning of the 6111 с . , is more acceptaЬie (Dintchev 1997Ь, 1 02).

31 Shkorpil's data are in feet. Cf. above ft . # 28.

32 Тhis area and the corresponding walls are assumed for а later period (Bakiritzis 1989, 47), but hardly the late antiquity town of Maroneia was defended Ьу the walls over 10 km long of the old Greek colony (Ла~ар\Ь'l~ 1972, fig .37; Bakirirtzis 1989, fig. 16).

49

Ventzislav Dintchev

Maroneia and in the near territory some representative late antique buildings have been explored (Pantos 1983, 168-169; Bakiritzis 1989, 46-47).

Zikideva appeared as а town centre of the province of Moesia lnferior in the late 51

h -

early 61h. The many complexes and buildings

studied here with а different puЬlic purposes, as well as the impressive number of the residential buildings exposed, bear witness for its meaning. Zikideva is mentioned Ьу Procopius and Theophilactus Simokatta, as well as in Notitiae Episcopatuum in the place of Nicopolis ad lsrrum (Dintchev 1997с, 54-77). The data puЬlished about the area of the hill, on which the main fortress of Zikideva is, are controversial. Anyway, this area is not less than 12-13 ha.33 According to the latest researches the fortress which surrounds the river terrace at the west foot of the hill and which is directly connected with the fortress of the hill

lh also refers to the 6 с. The water supply of the town on the hill was guaranteed with the lower fortress. In some of the towers of this fortress wells were made. The most significant is in the south corner tower. The approach to it from the hill is secured in an impressive way - through the passage staircase in the south wall of the lower fortress (Тотев/Дерменджиев 1997, 143-155). Tl1e area of this fortress is about 2.5 ha (Тотев/Дерменджиев 1997, 150), i.e. the defended territory of Zikideva is no less than 15 ha in general. At about 250 m crow flight, westwards from the main fortress of Zikideva is the east end of the fortress of а synchronous satelite settlement, whose area is not less than 4-5 ha (Dintchev 1997с, 65-66).

The yet unidentified town near Konjuh in today's Macedonia seems to have been the most important late antique centre in the east part of the province of Dardania. It is assumed

that its fortification and urbanization in general were done in 41

h с. In its defended area, which is about 17, ha re·mains of different buildings were registered, including а representative Christian basilica. Many premises and appurtenances are cut into the rocky ground of its higher central part (Микулчик 1974, 366-368; Miculcic 1974, 207-208; Георгиевски 1996, 73-74l.

In the 41 с in Acrae in the province of Scythia probaЬly did not have а town status yet. Together with the external wall built not earlier than the second half of the 41

h с. the entire defended territory of that centre reached up to 15 ha, and after the middle of the 5th с. it was already one of the important centres of the province.34 In that case the third place of Acrae among the sea towns of Scythia in the Hierocles' list (ГИБИ 1959, 90) corresponds to the archeological data. А significant late antique centre is the one

near Chomakovtsi in today's northwest Bulgaria - in the east part of the province of Dacia Ripensis. Its fortress was built not earlier than the end of the 3rd century. Most of the late antique bui1dings, appurtenances and finds discovered during the incidental excavations are from the end of the 3rd- 41

h (Шкорnил 1905. 480-481, pl. CVII 1, 2; Vetters J 9 50. 13- J 4: Иванов 1961, 255-269; Ковачев<1/Бънов 1990, 81-83). According to the d<1ta and the plan of К. Skorpil, the defended area of that centre is about 13 ha,35 and according to T.lvanov- about 15 ha (Иванов 1961, 257). An assumption has been made that this is Zetlloиkortou (Velkov 1977, 89-90). The latter \vas mentioned only Ьу Procopius as а xropюv ,

but together with Oescus and Cas11·a Martis (ГИБИ 1959, 167-168), i.e. in а city context.

One of the five, according to Hierocles, towns of the province of Moesia Superior is

33 In а monograph of an author-architectthe territory of thc hill is defined to have Ьееn more than 21 ha (Харбова 1979, 30, 48-49). This information was reflected in my first anicle about Zikide,,a (Dintchev 1997с, 55). According to а panicipant in the archeological excavations the area of the hill is about 12 ha (Николова 1986, 235). lf wc procced from the known plan (Dintchc:v 1997с, 71, fig . З), the second figure looks more reliaЬle. Precise calculations aftcr that and the other published plans ofthe hill ofTsarevcts, which are also without horizontals and elevations, cannot Ье done. The reason is in the fact that the terrain of the hill above its rock crown is not nat but pyramida1.

34 See аЬоvе ft.# 3

35 Skorpil's data arc in feet. See abovc ft.#28.

50

Classification of the Late Antique Cities in the Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

Horreum Margi (ГИБИ 1959, 94). The supposed outlines of its fortress walls surround an area of about 14 ha (Piletic 1969, 9-57). The researches confined so far do not allow а better idea of the late antique structure of this old city centre. The coins finds suggest perturbations ~~ the end of the 4

1h с and the mid

dle of the 5 с. (Bacuh 1990, 5-8, 89-92). Of the availaЬie data about the fortress of

Eudoxiopolis (the old Selymbria) it can Ье assumed that the defended area of the capital of the province of Europa is about 12 ha (Dirimtekin 1957, 127-129). These data, however, bear witness for а later dating of the registered fortification remains, which could mean that Eudoxiopolis was also reduced in its area Ьу or after the end of the 5

1h с. - the beginning of the

6 1h с., i.e. that the number pointed is the size of

the reduced area of the city in the 6 rh с. Abritus is among the new towns of the prov

ince of Moesia lnferior. lt was mentioned Ьу Hierocles (ГИБИ 1959, 90). The building of its fortress, which has been thoroughly researched, refers to the end of the 3rd- the beginning of the 4

1h с. (Иванов 1980). lts de

fendcd area is ctbout 12 hа.З6 Different public and private buildings have been studied in it: а Ьig and representative administrative and residentia1 complex, а large horreum, а Christian basilica with three naves etc. (Иванов/ Стоянов 1985; Георгиев et al. 1994, 74-75).

The present archeological information about а number of significant centres, according to the sources and to the modern historiogr<lphy, is rather scarce and insufficient for

а methodologically correct classification and assessment. Adrianopolis - the capita1 of the province of Haemimontus, Ainos - the capital of the province of Rhodopa, and Heraclea (the former Perinthus - the capital of the Roman Thracia) in the province of Europa must have been among the Ьiggest cities of the diocese of Thracia (Velkov 1977, 115, 120, 125). Its real archeological search has not started yet (Otuken/Ousterhout 1989, 121-131, n.l, 3, 4). For the defended area of Anhialo in the province of Haemimontus а figure is given, which exceeds а lot the corresponding figures of all mentioned above towns in the two dioceses -about 120 ha (Стоев 1989, 37-40). The data about the walls of Anchialos- а result of geophysical researches - are not unquestionaЬle and are not archeologically precised37

. It has been announced as well about the walls of Panion in the province of Europa that they surround а Ьig territory (Outgun/Ousterhout 1989, 145-146), but precise data about the area and the chronology of the fortification remains visiЬle on the terrain have not been puЬlished yet. The results of the started researches in Deultum give а certain idea about this old urban centre in the province of Haemimontus (Дамянов 1982, 234-23 5; Бонева 1984, 23-28; Дамянов et al. 1987, 128-129; Дражева et al. 1994, 93), but are not enough for а more precise assessment and characteristics. The comparison, however, of this results with the data of the brothers Skorpil from the end of the last century (Шкорпил/ Шкорпил 1891, 133-138, fig. 46) suggests а

36 The defended area mentioned in the puЫications . about 15 ha (Иванов 1980, 29; Иванов/Стоянов 1985, 10) is exaggerated. There is a1so cenain inaccuracy in the metric data. For the who1e 1ength of the fonress Vialls was pointed that "it was about 1400 m" <Иванов 1980, 30), but the sum of the 1engths of the four walls (Иванов 1980, 31, 66, 83, 122) is \347m. At the same time the 1ength of the nonh wa11 is pointed to have Ьееn 295 m (Иванов 1980, 31 ), but it turns out from the sum of the ligures for the corresponding towers and sections of the cunain (Иванов 1980, 33-63) that the 1ength of this wall is no 1ess than 302m. About 12 ha is the defended area according to the p1an given (Иванов 1980, 30, fig. 10).

37 On1y а sma\1 section of the east wall has been confirrned archeo1ogically (Стоянов 1980, 1 05; Стоев 1989, 39, fig. 5). The ear1iest remains of а studied section in the south pan of the assumed defended area of Ancllialos are 1ate antique: they are from а Ьig farm hui1ding and of а furnace for bui1ding ceramic (Карайотов/Бонева 1989, 86-87; Бонева 1990, 93-94). 1t can Ье assumcd from the presence of the furnace that the surrounding terrain was not in the defended city area, \\'hich confronts thc data from the data from the geophysica1 rcsearches. Apan from the section at issue, saving excavations were made in the centra1 zone of Anclrialos. Small pans of а so1id bui1ding and of street with а representative architectura1 design ha,•e bcen found (Лазаров 1983, 300, 304; Sase1ov 1985. 138-143). They are а proof for а de,•e1opcd tovm structure, but are not enough for its characteristil:s.

51

Ventzislav Dintchev

significant reduction of the defended area of Deultum to about 5-6 ha still before the end of the 4

1h с.38 ProbaЬly Ammianus Marcellinus

was right to call the o\d Roman colony ogpidum (ЛИБИ 1958, 174) in the end of the 4 с.

Nicopolis ad Nestum in the province of Rhodopa belongs to the border classification zone between the midd\e and the sma\1 towns. Its defended area is about 11 ha. In the first two centuries. of its existence, i.e. unti1 the beginning of the 41

h с. this town does not \ook quite fortified, and its walls built at that time are kept as outline unti1 the end of the 61

h с. (Димитрова-Милчева 1992, 257-270). The representative puЬ\ic and private bui1dings from the Late Antiquity discovered in or near the fortress allow the referring of Nicopolis ad Nestum to the group of the middle urban centres (Vaklinova 1984, 641-649; ДремсизоваНелчинова 1987, 61-62; Димитрова

Милчева 1992, 268, Кузманов 1994, 24-34). The old town centre Tropaeum Traiani in

the province of Scyrhia сап Ье referred to this group. Its defended area in the Late Antiquity was (with its south-east extension) about 10.5 ha (Barnea et а\. 1979, 16). А testimony for its importance and demographic potentia1 are the big puЬlic buildings, including severa\ Christian basilicas, as we\l as the numerous, different in their plan and type private buildings, found in its research hitherto (Barnea et а\. 1979; Suceveanu/Barnea 1991, 199-202; Sampetru 1994, 18-53, 72-73, 84-85, 112-114; Poulter 1996, 116-117; Lungu 1997, 99-104; Cataniciu 1998, 201-214).

Two centres which are not identified -Gradishteto near the Yillage of Voyvoda in today's northeast Bulgaria, i.e. in the province of Moesia lnferior,39 and Davina near the village of Chucher in today's North Macedonia, i.e. in

the province of Dardania are in the border zone between the middle and sma\1 towns as well. The defended area of Gradishteto near Voyvoda is about 1 О ha. Its fortress was bui\t in the beginning of the 41h century. At that time in the near surroundings there was intensive manufacturing of building ceramics. The results of the excavations made prove the functioning of this centre until the end of the 61

h с. Unti1 the middle of the 51

h с. in front of its westem wall а proteichisma was built. In the researched small part of its defended area several residential buildings with stone-mudbrick construction have been found. Narrow roadpaths were discovered. The presence of unfortified suburbs is supposed (Милчев/ Дамянов 1972, 263-277; Дамянов 1978, 139-173; Милчев/Дамянов 1984, 43-84; Дамянов 1985, 253-259). The data given above prove the settlement character of that centre, but are not enough it to Ье included in the c\assification group of the middle towns. The situation is analogous with the data for the mentioned late antique centre near the vil\age of Chucher. Its defended area is defined to have been 9 ha. In it and in the suburbs remains of many buildings are registered (Mikulcic 1986, 107, 1 09). The absence of real archeologica\ researches in that case does not give а possiЬility the chronology of that centre to Ье precised.

А special р\асе in the classification and in the characteristics in general of the late antique Balkan town stakes lusriniana prima, identified now with Tsarichin grad at about 45 km south from the city of Nish ( Naissus)40

. According to the novelas from 535 and 545, and according to the data of Procopius (ГИБИ 1959,47-49,71, 156-157), lustiniana Prima is rюt only one of the new\y-built towns, but it

38 An earlier and more signiticant as an area fonress here has not Ьееn found so far, but in analogy with the most cities in the Roman ТJ1racia it can Ье assumed that also Colonia Flavia Pacis Deultensium was fonitied in the end of the 2nd с.

39 It is supposed that the Gradishteto near the village of Voyvoda is the fonress of Diniskarta, mentioned Ьу Procopius, " 'hich is identified with the to"'" of Dineia known from the 10

111 с (Бешевлиев 1962, 13-14; Velkov 1977, 106). However, this assumption has its opponents (Рашев 1988, 117-122).

4° From the two known no,•ellas of the emperor Justinian aЬout the rights of the archblshop of lustiniana Prima (ГИБИ 1959, 47-49, 71) it can Ье concluded that initially, i.e. Ьу 535 the town was in the territory of the province of Dacia Mediterranea, whereas later, i.e. in and after 545, the town and the territory around it were already in the province of Dardania.

52

Classification of the Late Antique Cities in the Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

was created Ьу the emperor Justiпiaп 1 to Ье ап admiпistrative апd cult capital of the whole пorthem lllyricum, iпcludiпg the proviпces of the diocese of Dacia. The loпg lastiпg archeological researches also give argumeпts for the special destiпatioп of this towп. lп its сопсерt and in its initiallook the structure of lustiniana Prima iпcluded maiпly units of representative character, among which the пumerous Christiaп buildings апd complexes are outliпed (Bavant 1984, 272-285; Duval 1984, 399-481; Guyon/Cardi 1984, 1-90; DuvaUJeremic 1984, 91-146; Bavant 1990, 123-125, 154-160; Vasic 1990, 307-315; Poulter 1996, 124-126). The results of the researches categorically refute, however, the statement of Procopius that it is а "town big and with many people" апd that "iп its size it is first" among "the other cities" of lllyricum (ГИБИ 1959, 156). The area of lustiniana Prima defended through а solid fortification - the so-called upper towп, including the acropolis with the episcopal complex, and the so-called down towп, is about 7.25 ha (Bavant 1984, 273-275). Having that structure and area the populatioп behind the walls clearly was поt at all fiUmerous. ProbaЬiy it was selected according to certaiп social criteria. The fact iп that respect is sigпificant that still with the fouпdiпg of the towп пеаr two of the churches of its defeпded area fuпerals were dопе. (Guyoп/Cardi 1984, 40-46, 89; Jeremic 1995, 182-187). Today it is supposed that the towп was surrounded Ьу suburbs. For some of them defeпce with grouпd fortificatioпs has been assumed. These suggestions, which have not been supported Ьу rea1 data41 , canпot change essentially the notion of lustiniana Prima. Every late antique town had suburbs. The possiЬie presence of exterпal ground fortifications, consideriпg their capacities саппоt as well refute the discrepancy betweeп the structure and the safely protected towп territory, respectively- between the Ьig administrative importance and the limited demographic and ecoпomic potential. In that sense defiпiпg

/ustiniana Prima as ап artificia1 creatioп or ап artificial towп is quite acceptaЬie (Duval/ Popovic 1980, 396; Bavaпt 1984, 272, 286; Popovic 1990, 303). The discrepaпcy betweeп the size апd the importaпce of the city, Ьу the way, seems to have Ьееп valid for about ЗО years, i.e. uпtil the епd of the rule of Justiпiaп 1. The chaпges iп the urbaп structure duriпg the reigп of the Justiпiaп I's successors: abaпdoпing most of the large buildiпgs апd the mass арреаrапсе of modest houses апd workshops amoпg their remaiпs (Bavaпt 1984, 285; Bavaпt et al ., 1990, 8-9;Popovic 1990, 269, 292-300, 305) iпdicate clearly without the support of its powerful protector the towп lost its privileged status апd that its admiпistrative importaпce at that time is iп syпchroпous with its real size апd poteпtial of а small towп.

The fortified late aпtique ceпtre of Augusta iп the proviпce of Dacia Ripensis has kept the outliпes of the precediпg Romaп camp there. Augusta is missiпg iп Hierocles, but it was meпtioпed as а яоА.~ Ьу Procopius. According to the latter only "the fouпdatioпs remaiпed" from Augusta, but the emperor Justiпiaп 1 turпed it iпto "а completely new and intact town with quite а nшnber of inhabitants" (ГИБИ 1959, 167). The data from the researches, including the specified magnitude of the defended area - about 8 ha (Машов 1991, 21-43; Mashov 1994, 21-36; Машов 1996, 71-72; lvanov 1997, 31-34) do not allow the referriпg of Augusta to the more importaпt late aпtique urbaп ceпtres.

The late antique lstros from the proviпce of Scyrhia should Ье referred to the group of the small towпs as well. lt was seriously damaged duriпg the iпvasioпs iп the Зrd ceпtury. ln the following ceпturies this old towп ceпtre lost а lot of its previous size апd importance. lt is поt Ьу chance that Ammianus Marcellinus iп the епd of the 41

h с. defines it as "the опее very powerful city oflstros" (ЛИБИ 1958, 143). lt is not Ьу сhапсе that its defeпded area was reduced several times апd was decreased to about

41 А necropolis at aЬout 150m southwest from the down fonress has been found, which functioned synchronically \\'ith the town (Jeremic 1995, 187-195). Consequently in southwest direction there \\•as not а suburb at all, ог it was too small and near the town fonress.

53

Ventzislav Dintchev

7 ha. Апуwау, mапу of the late antique buildings studied, includiпg the puЬiic buildings with differeпt fuпctions апd more represeпtative housiпgs - iп the defeпded area and iп the suburbs as well, are ап uпquestionaЬie proof for the urban character of /stros even after the

f rd

епd о the 3 ceпtury (Suceveaпu 1982, 85-92; Suceveaпu/Barnea 1991, 192-195; Sampetru 1994, 54-69, 88-89, 113-114; Suceveaпu/ Aпgelescu 1994, 204-208; Lungu 1997, 99-100, 104).

From the data availaЬie about the fortress of Bizye (Dirimtekiп 1963, 30-34, pl. 2; Pralong 1988, 194-197, fig.18) it сап Ье assumed that the defeпded area of this towп of the province of Europa is approximately as that of lstros42

.

The episcopa1 character of а medieval church iп Bizye suggests the same fuпction of the late antique basilica, оп which remaiпs it was built (Otuken/Ousterhout 1989, 138-139).

The 1ate aпtiquity ceпtre of Transmarisca as well seems to have Ьееп а small towп in the province of Moesia lnferior. It was поt meпtioпed Ьу Hierocles, but was known from other sources (Ve1kov 1973, 263-268). The data published about the sectioпs of its walls fouпd accideпtally assume its defended area to have been 6 -7 ha (Змеев 1969, 46-49).The excavatioпs which Ьеgап of aloпg the outline of the пorth wall prove its buildiпg to have been in the end of the 3rd- the beginпiпg of the 4th с . апd its fuпctioпiпg uпtil the beginniпg of the

th 7 с. (Ваrалински 1990, 76-78; Багалин-ски/Петков 1996, 68-69).

Remesiana is the last of cities of the province of Dacia Mediterranea listed Ьу Hierocles (ГИБИ 1959, 93). The defended area of

Remesiana was about 5 ha.43 Iп view of the accepted classificatioп parametres, this centre is in the border zone betweeп the small towns and the non-urban fortified settlements. The estaЬiished presence of representative units in its late antique structure, including in the suburbs (ПетровиЬ 1976, 94-102; Duval/ Popovic 1980, 375; Petrovic 1993, 80-81; Gusic I993b, 184-187) proves its urbaп character, but caпnot refute the defiпitioп of Procopius-1tOAtXVtOV, in that case (ГИБИ 1959, 93).

Bargala and Tzoides of the centres meпtioпed Ьу Hierocles, about which today there is more archeological iпformatioп, belong as well to the border zопе betweeп the small towпs апd the non-urbaп fortified settlements. At the time of Hierocles Bargala belongs to the proviпce of Macedonia Secunda in the diocese of Macedonia (ГИБИ 1959, 92). At least uпti1 371 Bargala was, however, in the proviпce of Dacia Mediterranea (Velkov 1977, 93, 98). The defeпded area of that centre iп the Late Aпtiquity was about 4.7 ha, but the known componeпts of its structure апd especially the representative episcopal complex prove its urbaп character (Aleksova!Maпgo 1971, 265-277; Mikulcic 1974, 202-204; Алексова 1986, 29-38; Aleksova 1996, 275-276).

The case with Tzoides is similar. It is the last of the towпs of the province of Haemimontus listed Ьу Hierocles (ГИБИ 1959, 92). lt was localized recently near today's tov.'n of Sliven (Велков 1982, 42; Щерева 1993, 16-17). The defended area of this new centre, fortified in the beginning of tl1e 4th с is about 4.5 ha44

. Haviпg, however, well built fortifyiпg system equipped V.'ith ап external under-

42 Comparing the data from the text (Dirimtekin 1963, 30-34) wiJh the plan (Dirimtekin 1963, pl . 2; see also Pralong 1988, 194, fig. 18) makes clear that the scale of the plan was not exact. lnstead of 1/2000 the scale should Ье 1/4000. The chro· nology of the two main constructing periods of the town wall suggested Ьу the author is as well questionaЬie: "d'avant l'epoque byzantine" and "а la fin de l'epoque byzantine" (Dirimtekin 1963, 35; see also Pralong 1988, 195-197). Even with this chronology of construction the outline of the fortress of Byzie in 4th - 6th с . shou1d have been the same as they are in the mentioned plan.

43 The announcements in the puЬiications about the defended area of Remesiana vary: а little over 6 ha (Duva11Popovic 1980, 375); about 5,5 ha (Bavant 19843, 283, n.113); about 6 ha (Petrovic 1993, 81 ). Considering the exact data for the longitude of the walls 200 х 214 х 200 х 273 m (Петровиl\ 1976, 96; Gusic 1993Ь, 185), and the trapezium shaped plan of the fortress (Gusic 1993Ь, 187), the defended area of Remesiana cannot exceed 5 ha. The linear scale of the mentioned plan was obviously mistaken.

44 In the puЬiications the defended area of Tzoides was defined to have Ьееn about or "а little more" than 4 ha (e.g. Щерева 1993, 15). According to the plan presented (Щерева 1993, 1 О, fig. 1) it defendcd territory Yias a1most 4,5 ha.

54

Classification of rhe Late Antique Cities in the Dioceses of Thracia and Dacia

ground passage, having а representative complex of cult and other Iarge and solid buildings in the inside partly studied so far, ha ving Iarge suburbs, including the Christian basilica explored there, and furnaces for building ceraшics etc. (Бацова 1973, 65-69; Щерева 1987, 27-35; Щерева 1993, 7-17; Stereva 1995, 7-13) Tzoides maintains its reputation of an urban centre.

Near Simeonovgrad in today's southeast Bulgaria - the province of Thracia, а Jate antique and medieva1 fortified centre has been localized. It is identified with Constantia - а

town known from the medieval sources. In the late antique sources Constantia cannot Ье found, but the name itself, as well as the context of its mentioning in some medieval sources give а reason to Ье assumed that it was already used still with the appearance of the centre in question in 4

1h с. (Гюзелев 1981, 9-

18; Гаrова 1995, 178-180). Its defended ареа was about 5 ha. А small part of it has been studied, in which, however, the remains of an early Christian basilica with а baptistery and а number of other synchronous buildings and appurtenances, including а solid building with puЬiic importance, water-reservoir, craftsman workshops were found. The fortress itself must have had an impressive look. An external underground passage was added to it. There are also data about Jate antique suburbs (Аладжов 1981, 253-256; Аладжов 1985, 15-17, 36-43; A1adzov 1987, 74-75). In the vicinity of it very precious finds from the 4th с. and the

th 6 с. were found (Аладжов 1961, 4 7-50; Aladzov 1987, 73, АЬЬ. 1; GerassimovaTomova 1987, 307-312). Therefore, according to its size and importance the late antique Constantia is quite similar to Remesiana, Bargala, or Tzoides and сап Ье defined as а centre of an urban type.

Some of the localized, but yet unstudied centres, mentioned as towns in the Jate antique sources might prove to Ье urban type centres too. The classification group most probaЬly will Ье filled with centres which are not mentioned with town definitions in the late antique sources, but which, similar to Constantia, for example, have the size and the importance of

the urban form of life in the Late Antiquity.

* * * The review presented so far makes us draw