Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--bystander CPR and end expired carbon...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--bystander CPR and end expired carbon...

ˇ

Resuscitation (2007) 72, 404—414

CLINICAL PAPER

Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiacarrest—–Bystander CPR and end expiredcarbon dioxide�

Stefek Grmeca,b,c,d,∗, Miljenko Krizmaric b, Stefan Mallya,Anton Kozeljb, Mateja Spindlera, Bojan Lesnikb

a Centre for Emergency Medicine Maribor, Ulica talcev 9, 2000 Maribor, Sloveniab University of Maribor-University College of Nursing Studies, Sloveniac Faculty of Medicine Maribor, Sloveniad Faculty of Medicine Ljubljana, Slovenia

Received 3 December 2005; received in revised form 17 July 2006; accepted 17 July 2006

KEYWORDSBystander CPR;Capnography;Basic life support;Utstein template;Witnessed cardiac arrest

SummaryIntroduction: The aim of this prospective cohort study was to describe the outcomefor patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Maribor (Slovenia) over a 4 yearperiod using a modified Utstein style, and to investigate elementary knowledge ofbasic life support among potential bystanders in our community.Patients and methods: Through the prehospital and the hospital database systemwe followed up a consecutive group of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest(OHCA) between January 2001 and December 2004. We investigated the effectsof various factors on outcome in OHCA, especially partial end-tidal CO2 pressure(petCO2), efficacy of bystander CPR and their elementary knowledge of basic lifesupport (BLS). We also examined motivation among potential bystanders and possibleimplementation for BLS education in our community.Results: OHCA was confirmed in 592 patients. Advanced cardiac life support wasinitiated in 389 patients, of which 277 were of cardiac aetiology. In 287 patients theevent was bystanders witnessed and lay-bystander basic life support was performed

only in 83 (23%). After treating OHCA by a physician-based prehospital medical teamROSC was obtained in 61%, the ROSC on admission was 50% and the overall survivalto discharge was 21%. Initial petCO2 (OR: 22.04; 95%CI: 11.41—42.55), ventricularfibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia as initial rhythm (OR: 2.13; 95%CI:1.17—4.22), bystander CPR (OR: 2.55; 95%CI: 1.13—5.73), female sex (OR: 3.08;95%CI: 1.49—6.38) and arrival time (OR: 1.29; 95%CI: 1.11—1.82) were associatedwith improved ROSC when using multivariate analysis. Using the same method we� A Spanish translated version of the summary of this article appears as Appendix in the final online version at10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.07.012.

∗ Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Grmec).

0300-9572/$ — see front matter © 2006 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.07.012

Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest 405

found that bystander CPR (OR: 5.05; 95%CI: 2.24—11.39), witnessed arrest (OR: 9.98;95%CI: 2.89—34.44), final petCO2 (OR: 2.37; 95%CI: 1.67—3.37), initial petCO2 (OR:1.61; 95%CI: 1.28—2.64) and arrival time (OR: 1.39; 95%CI: 1.33—1.60) were associatedwith improved survival. A questionnaire to potential bystanders has revealed disap-pointing knowledge about BLS fundamentals. On the other side, there is a welcomedwillingness of potential bystanders to take BLS training and to follow dispatchersinstructions by telephone on how to perform CPR.Conclusion: After OHCA in a physician-based prehospital setting in our region, theoverall survival to discharge was 21%. The potential bystander in our community isgenerally poorly educated in performing CPR, but willing to gain knowledge and skillsin BLS and to follow dispatchers instructions. Arrival time, witnessed arrest, bystanderCPR, initial petCO2 and final petCO2 were significantly positively related with ROSC onadmission and with survival. Prehospital data from this and previous studies providestrong support for a petCO2 of 1.33 kPa to be a resuscitation threshold in the field.In our opinion the initial value of petCO2 should be included in every Utstein style

td.

I

ThdmIrlcpabfteccsfoon2pvieae

P

S

Il

Dcgag

S

Tassy

Ds

CtIwblttcdt

Lephysician and two registered nurses or medicaltechnicians.

The BLS team is manned by two medical

analysis.© 2006 Elsevier Ireland L

ntroduction

he prognosis among patients who suffer out-of-ospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is poor. Persistentiscouraging low survival rates requires reassess-ent of current strategies and capacities.1—6

mprovement in the results of cardiopulmonaryesuscitation (CPR) and the subsequent quality ofife after cardiac arrest is one of the greatesthallenges in emergency medicine.7,8 Documentedrognostic factors are ventricular fibrillation (VF)s the initial rhythm, witnessed cardiac arrest,ystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, timerom collapse to CPR and time to first defibrilla-ion. Human studies have suggested that partialnd-tidal CO2 (petCO2) correlates closely with suc-essful resuscitation and predicts the outcome ofardiac arrest reliably.9—12 Recent studies empha-ise bystander CPR as a very important contributoryactor in survival from OHCA.13—19 The aim of thisbservational study was to evaluate the outcomef OHCA and CPR in the town of Maribor (Slove-ia) in the period from January 2001 till December004. Our aim was to investigate the effects of ahysician-based prehospital emergency unit, initialalue of petCO2 and bystander CPR on outcomen OHCA in our community. We investigated thelementary knowledge of basic life support (BLS),nd the possible implementation and motivation forducation among potential bystanders.

atients and methods

tudy design

n this observational prospective study we col-ected data in the period from January 2001 until

tMTt

All rights reserved.

ecember 2004. All emergency calls in this periodlassified as OHCA dispatched to prehospital emer-ency unit were included. Data were collectednd analysed according to the Utstein criteria anduidelines.20

tudy area and population

he study community (town of Maribor with ruralrea) has a population of circa 200,000 inhabitantspread over an area of approximately 780 km2. Thetudy population was composed of adults over 18ears with OHCA.

escription of the emergency medicalystem (EMS)

onsistent with the European Union recommenda-ions, we have a single emergency number, 112.n the Centre for Emergency Medicine at Maribore have two prehospital emergency teams and twoasic life support teams equipped with the defibril-ators, 24 h a day and 7 days a week. Additionally, inhe period from April till October during daytime,here is a motorcycle rescuer with defibrillationapability; he and prehospital emergency team areispatched simultaneously and they rendezvous inhe field.

The prehospital emergency team is an Advancedife Support (ALS) unit of 3 members with anquipped road vehicle, including an emergency

echnicians or nurses and a driver (paramedic).otorcycle rescue is provided by a registered nurse.he prehospital emergency team is dispatched rou-inely in emergency situations (in case of presumed

S

Cwcpii((

rAsutI

R

Aa

IpcTco6of

L

T

406

cardiac arrest, heart attacks, respiratory distress,cerebrovascular incident, trauma, delivery, poison-ing, etc.). BLS and ALS are provided using a regionalprotocol that incorporates European ResuscitationCouncil guidelines and clinical algorithms for car-diac resuscitation. After resuscitation, the patientis transferred to the Intensive Care Unit of theteaching hospital in Maribor. Data for the Utsteincriteria, demographic information, medical dataand petCO2 values were collected for each patientin cardiac arrest by the emergency physician. Hos-pital records were used for outcome analysis, andincluded assesment of cerebral performance cate-gory (CPC) by intensive care unit specialist. A CPCscore of 1 reflected good cerebral performance,CPC 2 and 3 moderate and severe cerebral disabil-ity, CPC 4 comatose, vegetative stage, and CPC 5brain death.

End-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure(petCO2)

We measured petCO2 continuously and recorded itevery minute during resuscitation beginning withintial postintubation petCO2 (first petCO2 valueobtained). Measurements of petCO2 were done bymainstream method with infrared capnometer inte-grated into a Lifepack 12 defibrillator monitor,Physio Control, Medtronic Inc.

Questionnaire

In the second part of study we investigated themotivation of potential bystanders as to theireducation in CPR and tested their theoretical

knowledge of BLS with a questionnaire. We com-pared group I (persons who did not have anyexperience with acute coronary syndrome in theirown community) and group II (persons who hadexperience with acute coronary syndrome, mostlyin their own families).ivqBav

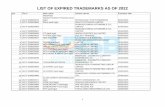

Table 1 Incident location and resuscitation profile

Totalarrests

Witnessed BystanderCPR

Inrh

Total 389 (100%) 287 (74%) 83 (22%) 13

LocationHome 203 147 (72%) 18 (21%) 6Public place 134 95 (71%) 32 (39%) 5EMSa 23 23 (100%) 0 1Other 29 22 (76%) 33 (40%)a EMS-personnel of Emergency Medical Service.

S. Grmec et al.

tatistical method

ontinuous data were expressed as a medianith a range. Proportions were reported with 95%onfidence interval. Analysis for variables wereerformed using a �2-test (with Yates correction,f appropriate) and exact Fisher test. Compar-sons between groups were performed using t-testnormally distribution) and Mann—Whitney testnormality test failed).

The null hypothesis was considered to beejected at p-values less than 0.05 in all tests.nalyses of independent predictors for ROSC andurvival from univariate analysis were performedsing a multivariate logistic regression. For statis-ical analysis we used computer software SPSS12.01nc. Chicago, IL, USA.

esults

ll cases of OHCA and resuscitationttempts

n evaluation period there were 592 emergencyatients without signs of circulation. Finally resus-itation was attempted in a group of 389 patients.he aetiology was presumed cardiac in 277 (72%)ases and non-cardiac in 112 (28%). Restorationf spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was obtained in1% (237/389) and ROSC on admission to hospitalccurred in 50% (195/389). Survival to dischargerom hospital occurred in 21% (82/389) (Figure 1).

ocation of the incident

he profile according to location of OHCA is shownn Table 1. Ventricular fibrillation and pulselessentricular tachycardia were observed more fre-

uently in patients who collapsed in public places.ystander CPR was performed in a higher percent-ge in public and working places than at home (40%ersus 22%, p = 0.02).tialythm VF

Intialrhythm VT

Initial rhythmasystole

Intialrhythm PEA

7 (35%) 19 (5%) 159 (41%) 74 (19%)

1 (31%) 2 (1%) 101 (49%) 39 (19%)4 (40%) 5 (4%) 57 (42%) 18 (14%)3 (57%) 5 (22%) 1 (4%) 4 (17%)6 (21%) 3 (10%) 8 (28%) 12 (41%)

Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest 407

tal c

A

Tm(bap

awc

Figure 1 Utstein reporting template for out-of-hospi

ge, sex and time analysis

wo hundred and seventy-three (70%) patients wereale and 116 female. The average age was 60 years

ranging: 18—91) without significant differencesetween survivors and those who died. In univari-te analysis we found significantly more femaleatients with ROSC than male (Tables 2 and 3). Sex

ap1i

Table 2 Clinical and demographic characteristics for 389 ca

Death in the

Sex (M/F)a 150/44Age (years)b 60.8 ± 13.2Initial rhythm VF + VT/ASY + PEAa (n/n) 54/140Witnessed arrestsa (Y/N; n/n) 138/56Bystander CPRa (Y/N; n/n) 24/170Initial petCO2 (kPa)b (n, n ± n, n) 0.944 ± 0.655Final petCO2 (kPa)b (n, n ± n, n) 1.000 ± 0.348Response time (min)b (n, n ± n, n) 10.93 ± 4.330

a Fisher test.b Wilcoxon rank sum test.

ardiac arrest in Maribor obtained in a 4 years period.

nd arrival time were associated with ROSC andith admission to hospital. Arrival time was asso-iated with survival (Tables 4 and 5).

The median interval from the call until the

rrival of prehospital emergency team at theatient’s side was 5 min (1—16) in the city and0 min (7—29) in suburban and rural area. Thisnterval was significantly shorter in survivors (6 minrdiac arrest patients, according to immediate outcome

field ROSC with hospitalization p-Value

123/72 0.00359.7 ± 12.5 0.273102/93 <0.001158/37 0.02458/137 <0.001

5 2.418 ± 0.7413 <0.0016 3.629 ± 0.9711 <0.001

8.41 ± 4.472 <0.001

408 S. Grmec et al.

Table 3 Clinical and demographic characteristics for the 389 cardiac arrest patients, according to survival

Death in the field Survivers p-Value

Sex (M/F)a 220/87 53/29 0.224Age (years)b 60.1 ± 13.1 60.5 ± 12.4 0.861Initial rhythm VF + VT/ASY + PEAa 118/189 38/44 0.206Witnessed rhythma (Y/N) 216/91 81/1 <0.001Bystander CPRa (Y/N) 49/258 33/49 <0.001Initial petCO2 (kPa)b 1.4 ± 0.9 2.6 ± 0.9 <0.001Final petCO2 (kPa)b 1.9 ± 1.3 3.9 ± 1.2 <0.001Response time (min)b 10.7 ± 4.4 5.9 ± 2.9 <0.001

a Fisher test.b Wilcoxon test.

Table 4 Variables associated with ROSC and admission to hospital in OHCA

Variables Odds ratio 95% confidence interval p-Value

Sex 3.08 1.49—6.38 0.002Intial rhythm (VF/VT) 2.13 1.17—4.22 0.02Time arrival 1.29 1.11—1.82 0.01Witness 1.19 0.54—2.65 0.66

1UCa(19s

Iw

ThpRad

Bystander CPR 2.55Initial petCO2 22.04

(1—14) versus 11 min (4—29), p < 0.0001). In thegroup of bystander witnessed OHCA the mediantime from collapse to 112 call was 4 min (2—26).

Resuscitation time by medical team (intervalfrom arrival to patient’s side to ROSC) was signif-icantly shorter in survivors (16 min (3—27) versus28 min (4—46) min, p < 0.0001).

Spontaneous circulation on admission to thehospital and survival

In our study, 195 (50%) patients had ROSC onarrival to the hospital and 82 (21%) were dis-charged alive from hospital. The univariate analysisfor ROSC on admission and survival are presentedin Tables 2 and 3. In a multivariate analysis(Tables 4 and 5) initial petCO2 (OR: 22.04; 95%CI:11.41—42.55), ventricular fibrillation or pulseless

ventricular tachycardia as initial rhythm (OR:2.13; 95%CI: 1.17—4.22), bystander CPR (OR: 2.55;95%CI: 1.13—5.73), female sex (OR: 3.08; 95%CI:1.49—6.38) and arrival time (OR: 1.29; 95%CI:(

ha

Table 5 Variables associated with survival in OHCA

Variables Odds ratio

Arrival time 1.39Witness 9.98Bystander CPR 5.05Intial petCO2 1.61Final petCO2 2.37

1.13—5.73 0.02411.41—42.55 <0.0001

.11—1.82) were associated with improved ROSC.sing the same method we found that bystanderPR (OR: 5.05; 95%CI: 2.24—11.39), witnessedrrest (OR: 9.98; 95%CI: 2.89—34.44), final petCO2OR: 2.37; 95%CI: 1.67—3.37), initial petCO2 (OR:.61; 95%CI: 1.28—2.64) and arrival time (OR: 1.39;5%CI: 1.33—1.60) were associated with improvedurvival.

nitial and final value of petCO2 of patientsith OHCA

he initial values of petCO2 were significantlyigher in patients with ROSC on admission to hos-ital compared with the group of patients withoutOSC (2.4 ± 0.8 kPa versus 0.9 ± 0.7 kPa, p < 0.0001)nd in those who survived compared with those whoied (2.6 ± 0.9 kPa versus 1.4 ± 0.9 kPa, p < 0.0001)

Tables 2 and 3).The final values of petCO2 were significantlyigher in the group of patients with ROSC ondmission to hospital compared with those without

95% confidence interval p-Value

1.33—1.60 0.012.89—34.44 <0.00012.24—11.39 <0.00011.28—2.64 0.0291.67—3.37 <0.001

U st

Raw(p

sfpfa

I

Ovvww(TV

Rta

W

IatawRtc

B

A

tstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arre

OSC (3.6 ± 0.9 kPa versus 1.0 ± 0.8 kPa, p < 0.0001)nd in those who survived compared with thoseho died (3.9 ± 1.2 versus 1.9 ± 1.3, p < 0.0001)

Tables 2 and 3). All patients with ROSC had an intialetCO2 value over 1.33 kPa.

In 158 (81%) of all 195 ROSC patients the firstign of ROSC was a rise in petCO2 (on averageor 1.8 ± 0.6 kPa), before palpable pulse or bloodressure was detected. In multivariate analysis weound association between intial and final petCO2nd ROSC and survival in OHCA (Tables 4 and 5).

nitial rhythm

ne hundred and thirty-seven patients had OHCA inentricular fibrillation and 19 patients in pulselessentricular tachycardia. In all, 28 (21%) patientsith VF and 10 (53%) patients with pulseless VT

ere discharged alive. Asystole was present in 15941%) and PEA in 74 (19%) of cases (Figure 1,ables 2 and 3). The patients with VF or pulselessT as initial rhythm had twice as good a chance of

hacB

Figure 2 The Utstein style report for out-of-hospital

409

OSC on admission to hospital and five times bet-er chance for survival compared to patients withsystole or PEA as the intial rhythm (Tables 4 and 5).

itnessed arrests

n the group of 291 patients with witnessed cardiacrrest we observed ROSC on admission to hospi-al in 158 (54%) and 81 (29%) were dischargedlive (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3). The patients withitnessed OHCA had 1.2 times better chance ofOSC on admission to hospital and 9.9 times bet-er chance for survival compared to unwitnessedollapse (Tables 4 and 5).

ystander CPR

total 83 (23%) of all treated patients with OHCA

ad bystander CPR (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3). Inddition in 23 cases the emergency team witnessedollapse in the field. The patients who receivedLS had 2.6 times better chance of surviving tocardiac arrests with presumed cardiac aetiology.

w2w

P

TFad

P

WoccdOh

410

hospital admission and five times better chanceof being discharged alive from hospital comparedto others (Figure 1, Tables 4 and 5). The patientswho received CPR from EMS professionals had 2.7(1.3—4.3) times better chance to be dischargedalive from hospital compared with other bystanderCPR. In our investigation we found that bystanderCPR performed by a lay person was associated with2.6 and 2.2 better chance of surviving event atthe field and being discharged alive from hospitalcompared to cases, where no bystander CPR wasperformed.

In our area only 13% (36/291) of bystanders fol-lowed dispatcher-provided telephone instructionsfor CPR, which represents 43% of all bystanders CPRin the field. Survival (discharge from hospital) in thedispatcher subgroup was 39% (14/36), and that issignificantly better than the general survival ratein OHCA patients (39% versus 21%, p = 0.001).

Neurological outcome

Out of all cases of cardiac arrest, 82 patients weredischarged alive from hospital. Of these 51 patients

Q

Tc

Figure 3 The Utstein style report for out-of-hospi

S. Grmec et al.

ere with CPC-1 or CPC-2 (13% of all OHCA victims),9 were with CPC-3 or CPC-4 (7.5%) and 2 patientsere with CPC-5 (0.5%).

resumed cardiac aetiology

he information on cardiac aetiology is shown inigure 2. Overall 24% of patients were dischargedlive from hospital, who had OHCA due to cardiacisease.

resumed non-cardiac aetiology

e found 112 (29%) patients with non-cardiac aeti-logy of collapse. The most frequent cause ofardiac arrest were hypoxia (33) and cerebrovas-ular incident (25). In Figure 3 the outcome isescribed with regard to non-cardiac aetiology.verall 15% of patients were discharged alive fromospital.

uestionnaire of potential bystanders

he group without experience of ACS had signifi-antly more individuals who had undertaken a BLS

tal cardiac arrests with non-cardiac aetiology.

Utstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest 411

Table 6 The results of the questionnaire for potential bystanders

Question The group with experiencewith ACS, N = 130

The group withoutexperience with ACS, N = 150

p-Value

Sex Male 64/130 (49%) Male 72/150 (48%) 0.86Female 66/130 (51%) Female 78/150 (52%)

Age 50 (18—80) 37 (18—86) 0.24

Have you undertaken any BLScourse?

Yes: 72/130 (55%) Yes: 111/150 (74%) 0.04

No: 58/130 (45%) No: 39/150 (26%)

Have you renewed any BLScourse?

Yes: 18/72 (25%) Yes: 26/111 (23%) 0.89

Could you recognise cardiacarrest?

Yes: 18/130 (14%) Yes: 23/150 (15%) 0.67

No: 14/130 (11%) No: 7/150 (5%)Possibly: 98/130 (75%) Possibly: 120/150 (80%)

Would you follow instructionsfor CPR by telephone(dispatcher)?

Yes: 102/130 (79%) Yes: 143/150 (95%) 0.23

No: 25/130 (19%) No: 4/150 (3%)I do not care: 3/130 (2%) I do not care: 3/150 (2%)

Where is the position for chestcompression?

Correct answer: 75/130 (58%) Correct answer: 65/150 (43%) 0.04

What is the appropriate ratio ofcompressions to rescuebreathing?

Correct answer: 28/130 (22%) Correct answer: 22/150 (15%) 0.73

What is the recommended rateof chest compressions?

Correct answer: 26/130 (20%) Correct answer: 7/150 (5%) 0.03

/130

cubctCpfn(

D

ToiIOwiroy

dIfirdescio

hcit9HAP

How deep must you press for aeffective chest compression?

Correct answer: 59

ourse (p = 0.04), but not significantly more who hadndertaken refresher training in BLS (p = 0.89). Inoth groups only 14% or 15% of potential bystandersould be presumed to recognise cardiac arrest. Par-icipants in both groups agreed with instructions forPR by telephone (79% and 95%). There were disap-ointing results when they answered on some veryundamental questions about BLS. Results were sig-ificantly better in group with experience of ACSTable 6).

iscussion

he observed incidence of attempted CPR in out-f-hospital cardiac arrest (50 per 100,000 per year)n this study is close to the international average.n the analysis by Herlitz et al.21 the incidence ofHCA in which resuscitated efforts were attemptedas similar in a range of 34—63 per 100,000 inhab-

tants. In European perspective Skogvoll et al.22

eported an annual incidence of attempted CPRf between 33 and 71 per 100,000 inhabitants perear.

aoT

(45%) Correct answer: 43/150 (29%) 0.03

As reported in most studies the majority of sud-en cardiac arrests are of cardiac aetiology.1—6,10,22

n our study, a primary cardiac cause was con-rmed in 277 (72%) out of 389 attempted CPR. Theegistered pre and post-incident hospital diagnosesocument a high prevalence of cardiovascular dis-ases among our patients: more than half of theurvivors (59%) and non-survivors (63%) were dis-harged with the final diagnosis of acute myocardialnfarction. These results correlate with results ofther studies.3,6,22

The observed 50% ROSC in patients admitted toospital and 21% overall survival in our region islose to the results from others studies. In compar-son, overall survival after OHCA was better thanhose from other EMS (Trondheim 11%22; Katowice%; Heidelberg 14%; Bonn 16%; Saint-Etienne 8%;elsinki 17%2; Copenhagen 11.7%1; Taipei 15.6%8;lachua County — Florida 4.4%23; Okayama 5%3;ittsburgh 11.5%24).

For patients presenting with VF and pulseless VTfter bystander witnessed collapse of cardiac aeti-logy the 38% survival rate (34/88) is similar to therondheim 32%,22 Bonn 34%,2 Copenhagen 20%,1

ii

rdwBb

cynCteftCtwCtmniocHmcCct(psgnrta

bgfEdmfTopprevious CPR training. Dorph et al.35 confirmed that

412

Helsinki 33%2 and better than in New York City(5.3%)25 or in Katowice (10%).2 The difference inoutcome may depend on the EMS system, responseinterval, incidence of VF and VT, socioeconomic anddemographic status, comorbidity and so on.24—26

We found a significant proportion (29%) ofpatients discharged with severe mental disability(CPC 3 or CPC 4). When we compare this fact withthe excellent cerebral outcome from in-hospitalCPR in a study of Skogvoll et al.,27 we can concludethat the time from arrest to CPR is crucial for goodneurological outcome. In 68% (36/56) of patientswith CPC 1 or 2 the time from call to arrival atpatients site was less than 6 min and 70% (39/56)of these patients had bystander CPR. With strictapplication of recommendations about inducedtherapeutic hypothermia we expect better resultsin future.28,29

As we reported previously, petCO2 monitoringis correlated with ROSC and survival after cardiacarrest.10—12 The results of this study confirmed theprognostic value of capnography in monitoring car-diac arrest in prehospital setting. In our previousstudy we found that initial, final, maximum, min-imum and mean petCO2 values were all higherin patients, who were resuscitated than in thosewho were not.10 In a similar study11 we confirmedthat initial and final values of petCO2 were higherin discharged patients and in patients with ROSC,and in all of them the initial petCO2 value wasover 1.33 kPa. This fact was confirmed again in thisstudy. In 81% of patients with ROSC a rise in petCO2value was the first evidence of ROSC, before apalpable pulse or measurable blood pressure wasestablished.

Our study provides a strong support for consider-ing a petCO2 threshold of 1.33 kPa for resuscitationin the field. We recommend intial petCO2 to beincluded ranked in every Utstein style report,where patients should be separated in two cate-gories: ‘‘Patients with intial petCO2 > 1.33 kPa’’ and‘‘Patients with petCO2 = or < 1.33 kPa’’. The Utsteinstyle analysis with above information will giveus valuable information about initial condition ofpatients in cardiac arrest.

In our investigation we found that bystander CPRperformed by a lay person was associated with bet-ter chance of surviving the event in the field andto be discharged alive from hospital compared tocases where no bystander CPR was performed. CPRperformed by EMS professionals was associated withhigher survival compared with CPR performed by

lay persons. These results are in agreement withsimilar studies.13—15 Bystander CPR was performedin 28% of patients with OHCA and is comparable toother studies findings (36% in Sweden, 23% in Katow-iwa

S. Grmec et al.

ce, in Heidelberg 25%, Bonn 15%, Helsinki 16% andn Copenhagen 16%).1,2,15

A questionnaire of potential bystanders hasevealed disappointing knowledge about BLS fun-amentals. On the other side, there is a welcomedillingness of potential bystanders to undertakeLS training and to follow dispatchers instructionsy telephone on how to perform CPR.

We must recognize this facts in an emergencyall for intervention. Most BLS trainees are usuallyoung. Because most cardiac arrests are wit-essed by older individuals we must change thePR training strategy and focuse on elder poten-ial bystanders, especially on those, who havexperience with acute coronary syndrom in theiramilies.30,31 Casper et al.32 confirmed, that vic-ims of cardiac arrest are more likely to receivePR when event is witnessed by bystander unknowno the victim than by friends or family. In our triale found a significantly lower rate of bystanderPR at home than in public places or other loca-ions (Table 1). These results suggests than weust focus on educating members of families with

o experience of prior cardiovascular incidents,ncluding ACS. So far, CPR training has been skillsrientated, and has assumed that a bystanderompetent in CPR will intervene when required.owever, this does not seem to be the case. Perhapsotivation aspects how to overpass psychologi-

al hindrances to start CPR should be included inPR training. Besides manikin instructor courses weould include audio or video-tape coached selfprac-ice on manikins. Mere viewing of demonstrationstelevised public service announcements) withoutractice has enabled more persons to perform somekills effectively compared to untrained controlroup. Repetitive television spots and brief inter-et movies for motivating and demonstrating wouldeach all people.33 Becker et al. confirmed thathe television public service announcements haven impact on the rate of bystander CPR.34

In our trial survival to discharge was significantlyetter when CPR instructions by telephone wereiven. In our area, only 13% (36/291) of bystandersollowed dispatcher telephone instructions for CPR.ffective telephone CPR requires rapid dispatchersetection of suspected cardiac arrest, good com-unication with short and clear instructions (only

or chest compression?) and cooperative bystander.he largest group of cardiac arrest patients are menver the age of 60 years at home, and most probableotential CPR provider is an older woman without

n this group of bystanders dispatcher-assisted CPRas of very poor quality. In spite of that, dispatcher-ssisted bystander CPR seems to increase survival in

U st

cc

C

Ao2wCortirtips

C

Te

R

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

tstein style analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arre

ardiac arrest, and should be included in emergencyall processing.

onclusions

fter OHCA in a physician-based prehospital EMS inur region, the overall survival to discharge was1%. Variables associated with ROSC and survivalere: arrival time, witnessed arrest, bystanderPR, intial petCO2 and final petCO2. This, andur previous studies, provide strong support for aesuscitation to be attempted considering a petCO2hreshold of 1.33 kPa in the field. We recommendntial petCO2 to be ranked in every Utstein styleeport to provide better insight into initial condi-ion of patients in cardiac arrest. The bystandern our community is generally poorly educated inerforming CPR, but willing to gain knowledge andkills in BLS and to follow dispatchers instructions.

onflict of interest statement

he authors declare they have no conflicts of inter-st regarding this study.

eferences

1. Horsted TI, Rasmussen LS, Lippert FK, Nielsen SL. Out-come of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—–why do physicianswithhold resuscitation attempts? Resuscitation 2004;63(3):287—93.

2. Rudner R, Jalowiecki P, Karpel E, Dziurdzik P, Alberski B,Kawecki P. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrestsin Katowice (Poland): outcome report according to the‘‘Utstein style’’. Resuscitation 2004;61(3):315—25.

3. Hayashi H, Ujike Y. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in OkayamaCity (Japan): outcome report according to the ‘‘UtsteinStyle’’. Acta Med Okayama 2005;59(2):49—54.

4. Fredriksson M, Herlitz J, Engdahl J. Nineteen yearsexperience of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Gothenburg—–reported in Utstein style. Resuscitation 2003;58:37—47.

5. Bunch TJ, White RD, Gersh BJ, et al. Long-term outcomes ofout-of-hospital cardiac arrest after successful early defibril-lation. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2626—33.

6. Herlitz J, Bang A, Gunnarsson J, et al. Factors associatedwith survival to hospital discharge among patients hospi-talised alive after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: change inoutcome over 20 years in the community of Goteborg, Swe-den. Heart 2003;89(1):25—30.

7. Wilcox-Gok VL. Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.Med Care 1991;29:104—13.

8. Weng TI, Huang CH, Ma MH, et al. Improving the rate ofreturn of sponatenous circulation for out-of-hospital cardiac

arrests with a formal, structured emergency resuscitationteam. Resuscitation 2004;60(2):137—42.9. Wayne MA, Levine RL, Miller CC. Use of end-tidal carbondioxide to predict outcome in prehospital cardiac arrest. AnnEmerg Med 1995;25:762—7.

2

413

0. Grmec S, Klemen P. Does the end-tidal carbon dioxide(EtCO2) concentration have prognostic value during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest? Eur J Emerg Med 2001;8(4):263—9.

1. Grmec S, Kupnik D. Does the Mainz Emergency EvaluationScoring (MEES) in combination with capnomety (MEESc) helpin the prognosis of outcome from cardiopulmonary resuscita-tion in a prehospital setting? Resuscitation 2003;58:89—96.

2. Grmec S, Lah K, Tusek-Bunc K. Difference in end-tidal CO2between asphyxia cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrilla-tion/pulseless ventricular tachycardia cardiac arrest in theprehospital setting. Crit Care 2003;7:R139—44.

3. Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Effect of bystander car-diopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrestpatients in Sweden. Resuscitation 2000;47:59—70.

4. Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Factors modifying theeffect of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation on sur-vival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in Sweden.Eur Heart J 2001;22:511—9.

5. Herlitz J, Svensson L, Holmberg S, Angquist KA, Young M.Efficacy of bystander CPR: intervention by lay people andhealth care proffesionals. Resuscitation 2005.

6. Becker L, Vath J, Eisenberg M, Meischke H. The impactof television public service announcements on the rate ofbystander CPR. Prehosp Emerg Care 1999;3(4):353—6.

7. Eisenburger P, Safar P. Life supporting first aid trainingof the public—–review and recommendations. Resuscitation1999;41(1):3—18.

8. Swor RA, Jackson RE, Compton S, et al. Cardiac arrest inprivate locations: different strategies are needed to improveoutcome. Resuscitation 2003;58(2):171—6.

9. Swor R, Fahoome G, Compton S. Potential impact of atargeted cardiopulmonary resuscitation program for olderadults on survival from private residence cardiac arrest.Acad Emerg Med 2005;12(1):7—12.

0. Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, Berg RA, Billi JE, BossaertL, Cassan P, Coovadia A, D’Este K, Finn J, Halperin H,Handley A, Herlitz J, Hickey R, ldris A, Kloeck W, LarkinGL, Mancini ME, Mason P, Mears G, Monsieurs K, Mont-gomery W, Morley P, Nichol G, Nolan J, Okada K, PerlmanJ, Shuster M, Steen PA, Sterz F, Tibballs J, TimermanS, Truitt T, Zideman D, International Liaison Committeeon Resuscitation, American Heart Association, EuropeanResuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, NewZealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundationof Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, ResuscitationCouncils of Southern Africa, ILCOR Task Force on Car-diac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Outcomes.Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcomereports: update and simplification of the Utstein templatesfor resuscitation registries: a statement for healthcare pro-fessionals from a task force of the International LiaisonCommittee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association,European Resuscitation Council, Australian ResuscitationCouncil, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart andStroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Founda-tion, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa). Circulation2004 Nov 23;110(21):3385—97.

1. Herlitz J, Bahr J, Fisher M, Kuisma M, Lexow K, ThorgeirssonG. Resuscitation in Europe: a tale of five European regions.Resuscitation 1999;41:121—31.

2. Skogvoll E, Sangolt GK, Isern E, Gisvold SE. Out-of-hospitalcardiopulmonary resuscitation: a population-based Norwe-gian study of incidence and survival. E J Emerg Med

1999;6(4):323—30.3. Layoon AJ, Gabrielli A, Goldfeder BW, Hevia A, Idris AH.Utstein style analysis of rural out-of-hospital cardiac arrest(OOHCA): total cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) time

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

414

inversely correlates with hospital discharge rate. Resusci-tation 2003;56(1):59—66.

4. Wang HE, Min A, Hostler D, Chang CC, Callaway CW. Differ-ential effects of out-of-hospital interventions on short- andlong-term survival after cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscita-tion 2005;67(1):69—74.

5. Lombardi G, Gallagher J, Gennis P. Outcome out-of-hospitalcardiac arrest in New York City. The Pre-Hospital arrest Sur-vival Evaluation (PHASE) Study. JAMA 1994;271:678—83.

6. Clarke SO, Schellenbaum GD, Rea TD. Socioeconomic statusand survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Acad EmergMed 2005;12(10):941—7.

7. Skogvoll E, Isern E, Sangolt GK, Gisvold SE. In-hospitalcardiopulmonary resuscitation. 5 years’ incidence and sur-vival to the Utstein template. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand1999;43:177—84.

8. Holzer M, Bernard SA, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Roine SO, Sterz F,Mullner M. On behalf of the Collaborative group on InducedHypothermia for Neuroprotection after cardiac arrest.

Hypothermia for neuroprotection after cardiac arrest: sys-tematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis.Crit Care Med 2005;33(2):414—8.9. Virkkunen I, Yli-Hankala A, Silfvast T. Induction of therapeu-tic hypothermia after cardiac arrest in prehospital setting

3

S. Grmec et al.

using ice-cold Ringer’s solution: a pilot study. Resuscitation2004;62(3):299—302.

0. Swor R, Compton S. Estimating cost-effectiveness of masscardiopulmonary resuscitation training strategies to improvesurvival from cardiac arrest in private locations. PrehospEmerg Care 2004;8(4):420—3.

1. Swor R, Fahoome G, Compton S. Potential impact of targedcardiopulmonary resuscitation program for older adults onsurvival from private-residence cardiac arrest. Acad EmergMed 2005;12(1):7—12.

2. Casper K, Murphy G, Weinstein C, Brinsfield K. A com-parison of cardiopulmonary resuscitation rates of strangersversus known bystanders. Prehosp Emerg Care 2003;7(3):299—302.

3. Eisenburger P, Safar P. Life supporting first aid trainingof the public-review and recommendations. Resuscitation1999;41(1):3—18.

4. Becker L, Vath J, Eisenberg M, Meischke H. Theimpact of television public service announcements on the

rate of bystander CPR. Prehosp Emerg Care 1999;3(4):353—6.5. Dorphe E, Wik L, Steen PA. Dispatcher-assisted cardiopul-monary resuscitation. An evaluation of efficacy amongstelderly. Resuscitation 2003;56(3):265—73.