Using Nominal Group Technique to investigate the views of people with intellectual disabilities on...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Using Nominal Group Technique to investigate the views of people with intellectual disabilities on...

Using Nominal Group Technique to investigate the views of people

with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

Irene Tuffrey-Wijne, Jane Bernal, Gary Butler, Sheila Hollins & Leopold Curfs

Accepted for publication 6 November 2006

Irene Tuffrey-Wijne BSc RN RNMH

Research Fellow

Division of Mental Health, St George’s,

University of London, London, UK

Jane Bernal MB ChB MRCPsych

Honorary Senior Lecturer

Division of Mental Health, St George’s,

University of London, London, UK

Gary Butler

Training Advisor

Division of Mental Health, St George’s,

University of London, London, UK

Sheila Hollins MBBS FRCPsych FRCPCH

Professor of Learning Disabilities

Division of Mental Health, St George’s,

University of London, London, UK

Leopold Curfs

Professor of Learning Disabilities

Department of Clinical Genetics, University

Maastricht/Academic Hospital Maastricht,

Maastricht, The Netherlands

Correspondence to I. Tuffrey-Wijne:

e-mail: [email protected]

TUFFREY-WIJNE I . , BERNAL J. , BUTLER G., HOLLINS S. & CURFS L. (2007)TUFFREY-WIJNE I. , BERNAL J. , BUTLER G. , HOLLINS S. & CURFS L. (2007)

Using Nominal Group Technique to investigate the views of people with intellectual

disabilities on end-of-life care provision. Journal of Advanced Nursing 58(1), 80–89

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04227.x

AbstractTitle. Using Nominal Group Technique to investigate the views of people with

intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

Aim. This paper is a report of a study using the Nominal Group Technique as a

method to elicit the views of people with intellectual disabilities on sensitive issues,

in this example end-of-life care provision.

Background. Establishing consumer views is essential in providing appropriate end-

of-life care, yet people with intellectual disabilities have historically been excluded

from giving their opinion and participating in research.

Methods. Nominal Group Technique was used in three groups, with a total of 14

participants who had mild and moderate intellectual disabilities. This technique

involves four steps: (1) silent generation of ideas, (2) round robin recording of ideas;

(3) clarification of ideas and (4) ranking of ideas (voting). Participants were pre-

sented with an image of a terminally ill woman (Veronica), and were asked: ‘What

do you think people could do to help Veronica?’

Findings. Participants generated a mean of nine individual responses. The highest

rankings were given to issues around involvement in one’s own care, presence of

family and friends, offering activities to the ill person, and physical comfort meas-

ures.

Conclusion. People with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities are capable of

expressing their views on end-of-life care provision, and should be asked to do so.

The Nominal Group Technique presents an effective and acceptable methodology in

enabling people with intellectual disabilities to generate their views.

Keywords: attitudes, death and dying, learning disabilities, Nominal Group Tech-

nique, palliative care, patient participation, qualitative approaches

Background

There has been a growing emphasis in recent decades on the

importance of obtaining consumer input around healthcare

delivery (Crawford et al. 2002). Where traditionally the

shaping of healthcare services may have been based

exclusively around the views of professionals, it is now

standard practice to take account of consumer preferences,

for example through consumer forums. Most healthcare

services in Western countries have seen a proliferation of

tools measuring the appropriateness, effectiveness and quality

of healthcare services and interventions (Streiner & Norman

RESEARCH METHODOLOGYJAN

80 � 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1995, Bowling 2002). People with intellectual disabilities

have historically been excluded from decision-making about

the delivery of services that affect their lives, generally based

on the presumption that they are incapable of forming an

opinion around their own problems and needs. Although

there is growing emphasis in the Western world on inclusion,

empowerment and self-advocacy (Department of Health

2001, Marks & Heller 2003, Brandon 2005), reports of

meaningful involvement of people with intellectual disabil-

ities in the shaping of healthcare services remain scarce

(Young & Chesson 2006).

Dramatic demographic changes over the past century

have resulted in increased longevity for people with

intellectual disabilities, with patterns of mortality and

morbidity now approaching those of the rest of the

population (Tuffrey-Wijne et al. in press). Little is known

about the palliative care provision for this client group, and

in particular, around the appropriateness of end-of-life care

currently being provided. This is a pertinent issue: as both

intellectual disability services and palliative care services are

faced increasingly with the prospect of providing prolonged

end-of-life care for people with intellectual disabilities, they

need to find ways of tailoring such care to their clients’

needs.

When it comes to palliative care, ascertaining consumer

views and satisfaction with services presents particular

challenges, yet in this area of health care, too, consumer

input has become an important factor (Small & Rhodes

2000, Aspinal et al. 2003). If both user-involvement and

person-centred care are taken seriously, it seems imperative

to establish the views of people with intellectual disabilities

on what they value at the end of life. The importance of this is

exemplified in studies that have shown discrepancies between

the views of patients and those of staff or relatives about

factors considered important at the end of life (Payne et al.

1996, Steinhauser et al. 2000a, Catt et al. 2005).

Palliative care is ‘an approach that improves the quality of

life of patients and their families facing the problems

associated with life-threatening illness’ (World Health

Organisation 2002). Inherent in this definition is the need

to establish what constitutes ‘quality of life’ for an individual.

During the past decade, the concept of ‘quality of life’ has

gained prominence in intellectual disability services, with a

growing emphasis on the need for quality of life applications

to be the basis for intervention and support (Schalock et al.

2002, Brown & Brown 2005). Whilst this is mostly hailed in

the literature as a positive development, it can also be

contentious, with concerns being raised that seeking to define

‘quality of life’ may lead to other people deciding what

constitutes a good quality of life for people with intellectual

disabilities, rather than empower people with intellectual

disabilities themselves (Northway & Jenkins 2003). From

this perspective too, then, ascertaining the views of people

with intellectual disabilities themselves on end-of-life care is

crucial, as they will be the experts on their own ‘quality of

life’.

Participative research, in which people with intellectual

disabilities are participants or even researchers themselves, is

gaining recognition (Kiernan 1999, Rodgers 1999, Walmsley

& Johnson 2003, Walmsley 2004). It is clear that people with

intellectual disabilities can and do express their views with

authority. However, in the area of palliative care, they have

been totally excluded; many are still being protected from

knowledge about death and dying (Todd 2004). Establishing

the views of people with intellectual disabilities about what is

important in end-of-life care provision may seem too difficult

a challenge. Apart from the existing taboos around death,

questions around palliative care may seem too abstract for

this client group. In addition, ethical concerns around

research involving people with intellectual disabilities in

questions around death and dying may seem prohibitively

challenging.

In other populations (such as hospice patients or the

elderly), views about end-of-life care have been elicited using

interviews (Townsend et al. 1990, Payne et al. 1996, Steinha-

user et al. 2000b, Vig et al. 2002), focus groups (Steinhauser

et al. 2000b, Tong et al. 2003) or postal questionnaires

(Steinhauser et al. 2000a). The choice of methodology for a

population of people with intellectual disabilities needs careful

consideration (Lindop 2006); some of the methods used in the

above studies are inappropriate for this group without major

adaptations.

The Nominal Group Technique

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was initially devel-

oped by Delbecq et al. (1975) as an organizational planning

tool. In healthcare settings, it has been used widely for

evaluating education (Davis et al. 1998, Lloyd-Jones et al.

1999, Lancaster et al. 2002, Dobbie et al. 2004), whilst it has

also been employed as a method for problem identification

and problem-solving in consumer groups (Miller et al. 2000,

Shewchuk & O’Connor 2002, Dewar et al. 2003). NGT

combines quantitative and qualitative data collection in small

groups of stake holders and typically involves four steps: (i)

silent generation of ideas by each individual; (ii) round-robin

recording of ideas; (iii) structured and time-limited discussion

of ideas; (iv) selection and ranking of ideas (voting) (Moore

1987). The advantages of this highly structured methodology

over Delphi and focus groups or brainstorming include an

JAN: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

� 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 81

avoidance of one individual monopolising the discussion,

allowing all participants to contribute equally, producing a

large pool of items, and being easy to implement (Gallagher

et al. 1993). A literature search produced highly limited

descriptions of the use of NGT with groups of people with

intellectual disabilities; one example is a study by Bostwick

and Foss (1981), who used it to identify major problems

faced by people with mild and moderate intellectual disabil-

ities in the domains of employment, community living and

social relationships.

The study

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate the use of the

Nominal Group Technique as a method to elicit the views of

people with intellectual disabilities on sensitive issues, in this

example end-of-life care provision.

Participants

The participants were a convenience sample of 14 people

recruited from a London theatre company for people with

intellectual disabilities, aged between 25 and 45 years. We

had no access to their clinical notes, but they all functioned

within the mild/moderate range of intellectual disabilities

(mental retardation) as defined by ICD-10 (World Health

Organisation 1992). Two members of the research team

(including GB, who has intellectual disabilities himself)

visited the theatre company to explain the study to three

different groups of about 18 people, asking them to volunteer

to participate in the study by joining a data collection session

the following week. The topic and the research question were

explained explicitly. The researchers clarified that partici-

pants’ views were important and would be widely dissemin-

ated, albeit anonymized. The aim was to establish groups of

six participants, bearing in mind that the ideal group size for

NGT is between five and nine participants (Moore 1987).

Two groups produced six volunteers; in the third group more

people volunteered, and staff at the theatre company selected

those who were, in their opinion, most able to cope with the

topic and verbalize their ideas. The researchers were not

aware of participants’ personal bereavement history, but staff

were asked to indicate whether, given people’s personal

histories, they thought it was appropriate for them to

participate. This did not lead to anyone being excluded.

Because of limited resources, the only room available for

conducting the study was up stairs; regrettably, this led to one

person being excluded because of mobility problems. Partic-

ipants were given an explanatory letter to take home and

share with their family or carers, detailing the context and

content of the study. Carers were alerted to the possible need

of participants to discuss at home the issues raised in the

study, and were asked to contact the research team if they

had any concerns. No concerns were raised by family, carers

or staff.

Data collection

Data were collected on three consecutive days in 2006. Four

volunteers decided not to attend, stating a reluctance to

discuss death and dying on that particular day. This left a

total of 14 participants (two groups of four and one group of

six). All had verbal skills, although some lacked literacy

skills. Staff were asked to be alert to possible signs of distress

following to study, and the research team offered to de-brief

participants if needed. One person showed signs of distress

after the information session; staff supported her in talking

about her own losses. Participants received a small gift token

at the completion of the NGT session.

Nominal Group Technique

Nominal Group Technique is a single-question technique,

and its success depends on the unambiguity of a question that

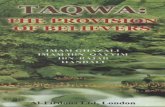

can generate a wide range of answers. For this study, a

picture of a woman resting in an armchair was selected

(Figure 1), accompanied by the following statement and

question: ‘This is Veronica. Veronica is very ill. She is not

going to get better. The doctor knows that she is going to die.

What do you think people should do to help Veronica?’ The

question was piloted with two colleagues who had intellec-

tual disabilities, and who provided feedback on the appro-

priateness and accessibility of the question. Training for the

co-researchers (JB and GB) and two research assistants was

provided by the principal researcher (IT).

Each session was led by IT and GB, and supported by two

other members of the research team. A member of staff from

the theatre company was also present, but did not take part in

the data collection. After introductions, the participants were

shown the picture and asked the question.

Step 1: generating ideas

The objective of this part is to facilitate contributions from all

group members. Each participant worked individually with a

researcher, who wrote down the participants’ ideas verbatim.

To reduce the likelihood of bias through researcher influence,

facilitators had been instructed not to question participants’

answers nor make any suggestions. It was stressed that all

I. Tuffrey-Wijne et al.

82 � 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

ideas were important and would be documented; there was

no limit to the number of ideas one individual could give.

Some participants had to wait until a researcher was available

to record their ideas. Most participants seemed pleased with

themselves after completing this step, smiling and giving

comments like ‘I did really well’.

Step 2: round robin recording of ideas

It was explained that this part of the process was to map the

group’s thinking, and to generate as wide as possible a range

of ideas from which participants could later choose the most

important ones. Participants were asked to read out (or to be

helped to read) one idea in turn, which was written verbatim

onto a flip chart. Some participants contributed new ideas,

inspired by those of other group members; these were also

recorded. No discussions or questions were permitted at this

stage. Each idea was affirmed; for example, when one parti-

cipant laughed at another’s idea of ‘an outing, like shopping

or going out for lunch’, commenting that Veronica surely

couldn’t do this as she was terminally ill, the group leader

noted that there may well be some terminally ill people who

would find the idea helpful.

Step 3: clarification

The group leader read through all the ideas written on the flip

charts, and asked for clarification where necessary. For

example, one participant who had suggested ‘lie in peace’ was

asked whether this meant ‘being in a peaceful room’, and

clarified that she meant ‘lie in peace after she dies’. Another

participant explained to the group what ‘make a will’ meant.

Step 4: voting

Whilst participants had lunch, the research team combined

the group’s ideas, collapsing similar ideas and simplifying the

wording. These were printed out onto separate pieces of

paper for each participant, producing sets of ‘voting slips’.

Participants were asked to select, individually, the five ideas

they thought were most important, putting all other slips of

paper aside. They were then asked to rank the ideas, giving a

score of 5 to the top idea, 4 to the next important idea, and so

on. Participants put the slips into voting boxes of decreasing

size, labelled 5 to 1. All researchers circulated the room

during this task, giving assistance where needed. Whilst some

participants could manage the task unaided, most (in par-

ticular those who lacked literacy skills) needed one to one

support. In most cases, the facilitating researcher read out

each idea and asked the participant whether to shortlist it or

not; the non-shortlisted ideas were removed, and the process

repeated until only five ideas remained. Many participants

found a comparison with the voting system at the Eurovision

Song Contest helpful, where the best song is given maximum

points.

Participants assisted in counting the votes. At the close of

the sessions, groups were asked for verbal feedback in

response to the simple question ‘What was it like for you to

be in this study?’ The whole process took around 2 hours,

including lunch.

Ethical considerations

Despite repeated efforts, we could find no ethics committee

responsible for work undertaken with the theatre company,

as this was a private company not governed by health or

social services. In recognition of the sensitive nature of this

study, we sought advice from the chairperson of the South

East London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee to

ensure that the study was conducted with due regard for

ethical issues, particularly concerning informed consent,

minimizing harm, and follow-up. This study is part of a

larger programme of work by the research team, consisting of

Figure 1 The NGT question. ‘This is Veronica. Veronica is very ill.

She is not going to get better. The doctor knows that she is going to

die. What do you think people should do to help Veronica?’

JAN: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

� 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 83

in-depth investigation of the perspectives of people with

intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care. This wider body of

research has been rigorously reviewed and approved by the

South East London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee

(Tuffrey-Wijne & Davies 2007).

Data analysis

Scores were added up for each idea, and the ideas were

ranked with the highest total score first, producing a list of

the groups’ ‘top ideas’. Identical scores were given the same

ranking number, although an idea that had more individual

votes was listed higher (for example, a score of 5 made up of

one vote of five points was lower on the list than one made up

of two votes of two and three points).

Results

Participants generated a mean of nine individual responses

(range 4–16). Identical responses were eliminated from the

group’s list, and collapsing ideas resulted in reducing the

number of ideas by half, leaving a total of 25, 17 and 15 ideas

respectively (See Table 1).

Participants appeared to have varying approaches to

answering the NGT question. Some searched the picture for

clues to what Veronica might want, resulting in suggestions

such as ‘close the window, give her a drink, keep her warm,

go to bed, someone to look after her dog when she goes to

hospital’. Others seemed to remember what happened when

they themselves had been ill: ‘give her a magazine, send cards

and flowers, watch TV’. A few participants based suggestions

on their experiences of the terminal illness of someone close

to them, for example: ‘Go into a nursing home’ and ‘Support

the parents because they are going to lose a daughter’.

The ideas put forward by the 14 participants were wide

ranging, covering several areas for end-of-life care provision.

These include factors associated with physical illness (medical

treatment, pain relief, food and drink, keeping warm),

involvement (tell her what is going on, listen to her wishes),

relationships (have family and friends around, phoning

friends, comfort and touch), organising supporting care (help

in the house, nursing presence, walk the dog, go to a nursing

home), keeping active and occupied (work, outings, TV,

magazines), atmosphere (lively, friendly, emotionally sup-

portive) and preparation for death (organize the funeral,

support the family, say goodbye).

The number of times an idea was suggested was no

indication of the final ranking of the idea; one of the highest

scores was given to an item that was suggested by only one

Table 1 Results

(a) Top 10 ideas for each group (with total score)

Group 1 (four participants)

1. Someone to listen to her wishes (7)

2. Make her comfortable and warm (5)

3. Have family and friends around (5)

3. Help her to go to work (5)

3. Ring an ambulance (5)

3. Care for her (5)

7. Help her to learn new things (4)

7. Hospital treatment (4)

7. Someone to walk her dog (4)

10. Help her family not to be scared (3)

Group 2 (six participants)

1. A ‘get well’ card, flowers and chocolate (17)

2. Get her a phone with credit so she can talk to her friends (14)

3. Get her family, sisters and neighbours (10)

4. Give her something she likes doing

(music, magazines, TV, book etc.) (10)

5. Ask her what she wants (6)

5. Give her medicine (6)

7. A nurse to come into the house and look after her (6)

8. Give her a cuddle and a kiss (5)

9. Get her something for her headaches (4)

9. Keep her warm enough (4)

Group 3 (four participants)

1. Tell her what is going on. Show her signs and pictures (9)

1. Support the parents; tell them what is going on (9)

3. Make her comfortable (8)

4. Have neighbours and friends around (6)

5. Go and do something (exercise, shopping and lunch) (5)

5. Someone to look after her (maybe a nurse) (5)

7. Organize the funeral (4)

8. Keep the pain away (4)

8. Someone to help her if she is feeling sad (4)

10. Go to bed, go to sleep (4)

(b) Other ideas (not in the top 10)

Be lively, happy, laughing

Help her to relax

Go into a nursing home

Someone living with her

Help with the housework

Give her food and drink

Lie in peace (after she dies)

Say goodbye

Check if she is hearing or not

An animal keeping her company

Make a will

Be friendly

Hold her hand

(c) Ideas with highest rankings across all groups

Involvement in one’s own care

Presence of family and friends

Offering activities to the ill person

Physical comfort measures

I. Tuffrey-Wijne et al.

84 � 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

person, but then had all six group members voting for it

(Get her a phone with credit so she can talk to her friends),

whereas the same group did not give any votes to an item

suggested by all six group members (Give her food and

drink). Likewise, issues around involvement in one’s own

care were put forward by only one participant in each group,

yet in all groups received a relatively high number of votes,

ranking first in two groups. Other issues with the highest final

rankings in all three groups were the presence of family and

friends, and offering activities to the ill person. Physical

comfort measures (other than medication or pain relief) also

scored highly in two groups [See Table 1(c)].

Evaluating the session, all participants said that they had

enjoyed it, using words like ‘fun’ and ‘exciting’. They

particularly liked the opportunity to give their ideas and

voting. Participants commented that the process seemed

difficult at first, but once they had started they found it easy

to complete. Other comments included ‘it was good to learn

about it’ and ‘it gets you thinking about yourself’.

Feedback from staff at the theatre company suggested that

none of the participants showed any signs of distress

following the NGT sessions, although some talked about

friends or relatives who had died and of whom the study had

reminded them. During the sessions, however, several

participants asked whether Veronica (the woman in the

picture) was a real person, and commented how sad her

situation was. The researchers stressed that Veronica was not

real, and compared the picture to ‘a story’, which participants

seemed to find helpful and reassuring.

Discussion

Our findings show that the people with intellectual disabil-

ities who participated were able to think about a difficult and

often taboo topic, such as death and dying. They were not

only able to give their opinions and show an ability to think

about a wide variety of issues that may be of importance in

end-of-life care, but relished the opportunity to do so. One

important question to ask is whether the ideas put forward by

our participants, or their prioritization, were affected by the

presence of intellectual disability. Of particular interest is the

relatively high ranking in all groups of issues of involvement,

and the emphasis on practical measures and keeping occu-

pied; it could be hypothesized that people with intellectual

disabilities give greater priority to these issues than those

without such disabilities. The findings further suggest that it

may be important, when supporting people with intellectual

disabilities who are terminally ill, to consider not only who

are the important people in a person’s life (and ensure that

these are encouraged to offer support), but also what kind of

activities the person enjoyed previously, and hence to what

extent this can be built into their end-of-life support. Choice

in palliative care is often not only concerned with obvious

issues such as planning funerals, but also with day-to-day

issues related to the use of available time; for example, people

suffering from cancer-related fatigue may be helped to plan

their activities through energy-conservation measures (Barnes

& Bruera 2002, Lipman & Lawrence 2004).

Direct comparisons of the findings with a general popula-

tion would only be possible in a larger study involving

participants with and without intellectual disabilities. Stein-

hauser et al. (2000a) found that seriously ill patients

suggested similar factors to be of importance at the end of

life, including help with symptoms or personal care, prepar-

ation for the end of life and being treated as a ‘whole person’

(such as humour, dignity, presence of close friends and

having someone who will listen). Catt et al. (2005) used NGT

to assess older people’s attitudes to end-of-life issues, and

found that they valued choice, dignity, addressing social

isolation, involvement and preparation for death. It seems

likely that several attributes, including participants’ social

and family roles, their own experiences of death and dying,

and closeness to death, affect the findings of such studies. It is

also interesting to note that both Steinhauser et al. (2000a)

and Catt et al. (2005) made comparisons with the views of

healthcare professionals, and found discrepancies with the

responses of patients and older people themselves. This is a

pertinent issue for people with intellectual disabilities, who

may be less involved in decisions about their own care and

support, and more dependent on decisions made by carers

and professionals.

Our findings provide a strong argument for involvement of

people with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities who

are facing a life-threatening illness in establishing priorities

for their own care. This has implications for nurses and other

healthcare professionals in a wide range of settings, including

acute settings, primary care, palliative care and intellectual

disability services. They need to try and find appropriate

methods and approaches to enable people with intellectual

disabilities to express their views and wishes. Apart from the

option of straightforward discussions, one way of achieving

this may be to use part of the technique described here, by

showing the person an image of someone in a situation

similar to themselves and asking what this fictional person

might need and want. Our findings suggest that many people

with intellectual disabilities base their answers on personal

experience; it is, therefore, likely that people who themselves

are terminally ill could identify with the image and answer

accordingly. The use of pictures to enable people with

intellectual disabilities to talk about cancer has been found to

JAN: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

� 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 85

be effective (Tuffrey-Wijne et al. 2006). Any measures taken

to establish the views of people with intellectual disabilities

about their own end-of-life care necessitates the presence of

staff who are skilled and sensitive, and this may have

implications for training and staff support. Nurses need to be

aware, however, that openness about death and dying can be

contentious amongst families and carers, and good collabor-

ation between everyone involved in a person’s care is crucial

(Tuffrey-Wijne 2003, Todd 2004, Brown et al. 2005).

Using NGT

Despite the particular context and limited sample size, affect-

ing representativeness of this study, the methods used in this

study may be generalizable and thus of interest to nurses and

other healthcare practitioners who are working with people

with intellectual disabilities and endeavouring to establish user

perspectives. This study could be regarded as a pilot study for

the use of NGT in this context; it is therefore important to

describe some of the methodological issues that emerged.

Moore (1987) states that ‘NGT is easy to learn and use,

(and) groups enjoy participating in an NGT because they

realize they have been unusually productive in a relatively

brief time’ (p 35). For people with intellectual disabilities,

who have seldom been asked for their opinion and have been

excluded from participating in research, the experience of

giving and ranking ideas may be particularly empowering. It

is crucial to create a safe and structured environment within

the group, calling for a skilled and experienced group

facilitator. NGT is a highly structured approach, which

may be particularly suitable for people with intellectual

disabilities. In a discussion of interviewing people with

intellectual disabilities, Booth and Booth (1994) note a

tendency to answer questions with a single word or a short

phrase, and a responsive rather than a proactive style. They

recommend that ‘techniques other than just talking have to

be used to engage the informant’ (p. 421). Sigelman et al.

(1981, 1982) found that a structured approach to questioning

produced the highest responsiveness. They conclude that

although open-ended questions were more difficult for

respondents, these were preferable to yes/no questions,

because of a tendency among people with intellectual

disabilities to respond ‘Yes’ regardless of the question. In

the light of these findings, it seems that NGT has great

potential for use with people with intellectual disabilities.

Following our study, a number of observations and

recommendations for further studies can be made. Whilst

certain ideas were consistent between groups in this study,

each group came up with entirely new suggestions, indicating

that saturation of ideas had not been reached. Considering

the fact that many participants voted for ideas that were

generated by others, it may be worth repeating the study with

other groups of people with intellectual disabilities until

saturation is reached, to develop a forced choice inventory

based on the most consistently high-ranking ideas that could

then be used by larger groups of participants (Bostwick &

Foss 1981).

The process of sorting and ranking ideas was the most

challenging for the participants, particularly for those who

lacked literacy skills. Confronted with a large number of

pieces of paper with printed text, some participants struggled

with the need to compare and prioritize sometimes abstract

concepts. A simple picture or other visual reminder on each

voting slip might be a source of bias, as some participants

might simply vote for the most attractive picture, but this risk

may outweigh the disadvantages of only using written text. It

would reduce the need for facilitator input (which is in itself a

potential source of bias), as well as enabling those with more

severe intellectual disabilities to participate. Other threats to

reliability include the possibility that participants might

choose randomly when confronted with a ranking decision;

this could be detected by measures to reduce bias, for

example, asking the person to do the task twice (Streiner &

Norman 1995).

Repeating NGT with different groups presents problems

with data analysis, as each group generates different lists of

items that are then difficult to compare. In collapsing the

individual responses into more general ideas for voting

purposes, we considered it important to remain as close as

possible to participants’ original ideas, resulting in slight

variations in wording, although concepts may have been

similar between groups (e.g. ‘someone to listen to her wishes’

and ‘ask her what she wants’). Having groups of only four

participants affects the validity of the final rankings, as even

one (possibly random) vote could move an item towards the

top of the list. Again, developing a standard set of items that

could then be voted on by larger groups of participants would

overcome the problem of analysis, although it may reduce

‘ownership’ (and therefore acceptability) of the process if

participants have not had a chance to generate their own ideas.

We recommend that when conducting NGT sessions with

people with intellectual disabilities, inviting eight participants

to each group is ideal; it is possible to accommodate eight

people in a group, whilst non-attendance should not reduce

the size of the group too much.

This study was conducted with people with mild and

moderate intellectual disabilities. To participate, a certain

level of verbal ability and a capacity to express ideas is

essential, although it may be possible for people without such

ability to take part in the final steps (voting). NGT in this

I. Tuffrey-Wijne et al.

86 � 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

format is not suitable for people with severe and profound

intellectual disabilities, who will have difficulty conceptual-

izing the question; to establish their views on end-of-life care

provision, a different methodology may be more appropriate;

one possibility would be participant observation (Angrosino

2004, Tuffrey-Wijne & Davies 2007).

Study limitations

Threats to validity and reliability have already been noted

above. Given the limited sample size, the findings need to be

treated with caution and are not easily generalizable. It is

worth noting, in particular, that people with intellectual

disabilities are a highly heterogeneous group, with wide

variations not only in level of intellectual ability and ability to

think in abstract concepts, but also in their own personal

experiences of death and dying. These variations may all

affect the way participants prioritize end-of-life care issues. It

is also worth noting that the participants in this study, as

members of a theatre company, were used to working in

groups and generating ideas.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that people with mild and moderate

intellectual disabilities are capable of giving their opinion,

and indeed should be asked to do so. This paper presents a

template for researchers, service managers and healthcare

providers who wish to assess the views of people with

intellectual disabilities about care and services provided. The

tools presented here are eminently transferable and can be

employed in other domains affecting the lives of people with

intellectual disabilities. More work is clearly warranted in the

important area of end-of-life care, particularly concerning

factors (such as age, life experience, level of intellectual

ability and social role) that affect the way people prioritize

issues. If we have demonstrated that people with intellectual

disabilities can contribute ideas about a taboo subject, such

as death and dying, then nurses and other health and social

care professionals have an obligation to involve them in

decisions about their care.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants and staff at the Theatre

Company in London for their generous help with this study.

Thanks to Michael Woodman for secretarial and technical

support, and help with data collection. The picture of

Veronica is taken from the book Getting On With Cancer

(Donaghey et al. 2002), with kind permission from the

publishers.

Author contributions

IT, JB and GB were responsible for the study conception and

design and IT was responsible for the drafting of the

manuscript. IT, JB and GB performed the data collection

and IT performed the data analysis. JB and LC made critical

revisions to the paper. SH and LC supervised the study.

References

Angrosino M. (2004) Participant observation and research on intel-

lectual disabilities. In The International Handbook of Applied

Research in Intellectual Disabilities (Emerson E., Hatton C.,

Thompson T. & Parmenter T., eds), John Wiley & Sons Ltd,

Chichester, pp. 161–177.

Aspinal F., Addington-Hall J., Hughes R. & Higginson I. (2003)

Using satisfaction to measure the quality of palliative care: a review

of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing 42, 324–339.

Barnes E. & Bruera E. (2002) Fatigue in patients with advanced

cancer: a review. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer

12, 424–428.

What is already known about this topic

• Growing numbers of people with intellectual disabilities

face a prolonged terminal illness and are in need of

appropriately tailored end-of-life care.

• People with intellectual disabilities have traditionally

been excluded from expressing their views on issues that

affect their lives, and from participating in research.

• End-of-life care provision for this group has been based

on the views of professionals, rather than those of pa-

tients.

What this paper adds

• The views of people with intellectual disabilities on

death, dying and end-of-life care have not been inves-

tigated or described in the literature. This paper shows

that people with intellectual disabilities want to give

their views, and are capable of doing so.

• The use of Nominal Group Technique with people with

intellectual disabilities has been limited. This paper

describes clearly how the methodology can be used with

this group, thus providing a template for other

researchers and service providers who wish to establish

the views of people with intellectual disabilities on is-

sues around service delivery.

JAN: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

� 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 87

Booth T. & Booth W. (1994) The use of depth interviewing with

vulnerable subjects: lessons from a research study of parents with

learning difficulties. Social Science & Medicine 39, 415–425.

Bostwick D. & Foss G. (1981) Obtaining consumer input: two

strategies for identifying and ranking the problems of mentally

retarded adults. Education & Training of the Mentally Retarded

16, 207–212.

Bowling A. (2002) Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health

and Health Services, 2nd edn. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Brandon T. (2005) Empowerment, policy levels and service forums.

Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 9, 321–331.

Brown R. & Brown I. (2005) The application of quality of life.

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 49, 718–727.

Brown H., Burns S. & Flynn M. (2005) Dying Matters: A Workbook

on Caring for People with Learning Disabilities Who are Ter-

minally Ill. The Mental Health Foundation, London.

Catt S., Blanchard M., Addington-Hall J., Zis M., Blizard B. & King

M. (2005) The development of a questionnaire to assess the atti-

tudes of older people to end-of-life issues (AEOLI). Palliative

Medicine 19, 397–401.

Crawford M., Rutter D., Manley C., Weaver T., Kamaldeep B.,

Fulop N. & Tyrer P. (2002) Systematic review of involving patients

in the planning and development of health care. British Medical

Journal 325, 1263–1265.

Davis D., Rhodes R. & Baker A. (1998) Curriculum revision:

reaching faculty consensus through the Nominal Group Technique.

Journal of Nursing Education 37, 326–328.

Delbecq A., Van de Ven A. & Gustafson D. (1975) Group Techniques

for Program Planning. Scott, Foresman and Company, Glenview, IL.

Department of Health (2001) Nothing About Us Without Us.

Department of Health, London.

Dewar A., White M., Posade S. & Dillon W. (2003) Using nominal

group technique to assess chronic pain, patients’ perceived chal-

lenges and needs in a community health region. Health Expecta-

tions 6, 44–52.

Dobbie A., Rhodes M., Tysinger J. & Freeman J. (2004) Using a

modified nominal group technique as a curriculum evaluation tool.

Family Medicine 36, 402–406.

Donaghey V., Bernal J., Tuffrey-Wijne I. & Hollins S. (2002) Getting

on with Cancer. Gaskell/St George’s Hospital Medical School,

London.

Gallagher M., Hares T., Spencer J., Bradshaw C. & Webb I. (1993)

The nominal group technique: a research tool for general practice?

Family Practice 10, 76–81.

Kiernan C. (1999) Participation in research by people with learning

disability: origins and issues. British Journal of Learning Disabil-

ities 27, 43–47.

Lancaster T., Hart R. & Gardner S. (2002) Literature and medicine:

evaluating a special study module using the nominal group tech-

nique. Medical Education 36, 1071–1076.

Lindop E. (2006) Research, palliative care and learning disability. In

Palliative Care for People with Learning Disabilities (Read S., ed.),

Quay Books, London, pp. 153–165.

Lipman A. & Lawrence D. (2004) The management of fatigue in

cancer patients. Oncology 18, 1527–1535.

Lloyd-Jones G., Fowell S. & Bligh J. (1999) The use of the nominal

group technique as an evaluative tool in medical undergraduate

education. Medical Education 33, 8–13.

Marks B. & Heller T. (2003) Bridging the equity gap: health pro-

motion for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Nursing Clinics of North America 38, 205–228.

Miller D., Shewchuk R., Elliot T. & Richards S. (2000) Nominal

group technique: a process for identifying diabetes self-care issues

among patients and caregivers. The Diabetes Educator 26,

305–314.

Moore C. (1987) Group Techniques for Idea Building. Sage Publi-

cations, London.

Northway R. & Jenkins R. (2003) Quality of life as a concept for

developing learning disability nursing practice? Journal of Clinical

Nursing 12, 57–66.

Payne S., Langley-Evans A. & Hillier R. (1996) Perceptions of a

‘good’ death: a comparative study of the views of hospice staff and

patients. Palliative Medicine 10, 307–312.

Rodgers J. (1999) Trying to get it right: undertaking research invol-

ving people with learning difficulties. Disability & Society 14,

421–433.

Schalock R., Brown I., Brown R., Cummins R., Felce D., Matikka L.,

Keith K. & Parmenter T. (2002) Quality of life: its con-

ceptualization, measurement and application. A consensus docu-

ment. Mental Retardation 40, 457–470.

Shewchuk R. & O’Connor S. (2002) Using congitive concept map-

ping to understand what health care means to the elderly: an

illustrative approach for planning and marketing. Health Market-

ing Quarterly 20, 69–88.

Sigelman C., Budd E., Spanhel C. & Schoenrock C. (1981) When in

doubt, say yes: acquiescence in interviews with mentally retarded

persons. Mental Retardation 19, 53–58.

Sigelman C., Budd E., Winer J., Schoenrock C. & Martin P. (1982)

Evaluating alternative techniques of questioning mentally retarded

persons. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 86, 511–518.

Small N. & Rhodes P. (2000) Too Ill to Talk? User Involvement and

Palliative Care. Routledge, London.

Steinhauser K., Christakis N., Clipp E., McNeilly M., McIntyre L. &

Tulsky J. (2000a) Factors considered important at the end of life by

patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 284,

2476–2482.

Steinhauser K., Clipp E., McNeilly M., Christakis N., McIntyre L. &

Tulsky J. (2000b) In search of a good death: observations of pa-

tients, families, and providers. Annals of Internal Medicine 132,

825–832.

Streiner D. & Norman G. (1995) Health Measurement Scales, 2nd

edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Todd S. (2004) Death counts: the challenge of death and dying in

learning disability services. Learning Disability Practice 7, 12–15.

Tong E., McGraw S., Dobihal E., Baggish R., Cherlin E. & Bradley

E. (2003) What is a good death? Minority and non-minority per-

spectives. Journal of Palliative Care 19, 168–175.

Townsend J., Fermont D., Dyer S., Karran O., Walgrove A. & Piper

M. (1990) Terminal cancer care and patients’ preference for place

of death: a prospective study. British Medical Journal 301, 415–

417.

Tuffrey-Wijne I. (2003) The palliative care needs of people with

intellectual disabilities: a literature review. Palliative Medicine 17,

55–62.

Tuffrey-Wijne I. & Davies J. (2007) This is my story: I’ve got cancer.

‘The Veronica Project’: and ethnographic study of the experiences

I. Tuffrey-Wijne et al.

88 � 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

of people with learning disabilities who have cancer. British

Journal of Learning Disabilities 35, 7–11.

Tuffrey-Wijne I., Bernal J., Jones A., Butler G. & Hollins S. (2006)

People with intellectual disabilities and their need for cancer in-

formation. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 10, 106–116.

Tuffrey-Wijne I., Hogg J. & Curfs L. End-of-life and palliative

care for people with intellectual disabilities who have cancer or

other life-limiting illness: a review of the literature and available

resources. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities,

in press.

Vig E., Davenport N. & Pearlman R. (2002) Good deaths, bad

deaths, and preferences for the end of life: a qualitative study of

geriatric outpatients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

50, 1541–1548.

Walmsley J. (2004) Involving users with learning difficulties in health

improvement: lessons from inclusive learning disability research.

Nursing Inquiry 11, 54–64.

Walmsley J. & Johnson K. (2003) Inclusive Research with People

with Learning Disabilities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

World Health Organisation (1992) ICD-10: International Statistical

Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th

Revision). World Health Organisation, Geneva.

World Health Organisation (2002) National Cancer Control Pro-

grammes: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. World Health

Organisation, Geneva.

Young A. & Chesson R. (2006) Obtaining views on health care from

people with learning disabilities and severe mental health pro-

blems. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34, 11–19.

JAN: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of-life care provision

� 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation � 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 89