The Tropical Forestry Action Plan: Is It Working

Transcript of The Tropical Forestry Action Plan: Is It Working

• & ••vs. •$

t-.'-.

•' •• * .•; •• ? .•-•• ' 5 ^ f" -? 1 • » . - : !•" - . . . "•".?."-

X

TAKING STOCK:

THE TROPICAL FORESTRY ACTION PLANAFTER FIVE YEARS

Robert Winterbottom

W O R L D R E S O U R C E S I N S T I T U T E

TAKING STOCK:The Ttopical Forestry Action PlanAfter Five Years

Robert Winterbottom

n

LT

W O R L D R E S O U R C E S I N S T I T U T E

June 1990

Kathleen CourrierPublications Director

Brooks ClappMarketing Manager

Hyacinth BillingsProduction Manager

Each World Resources Institute Report represents a timely, scientific treatment of a subject of public concern. WRI takesresponsibility for choosing the study topics and guaranteeing its authors and researchers freedom of inquiry. It also solicits andresponds to the guidance of advisory panels and expert reviewers. Unless otherwise stated, however, all the interpretation andfindings set forth in WRI publications are those of the authors.

Copyright © 1990 World Resources Institute. All rights reserved.ISBN 0-915825-58-9Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 90-071056

CONTENTS

PAGE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii

FOREWORD v

I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. TFAP—A PROPOSED RESPONSE TO THE DEFORESTATION CRISIS 3

III. ORGANIZATION OF THE TFAP PLANNING PROCESS 7

IV. RESULTS OF TFAP IMPLEMENTATION 9

V. ASSESSMENT OF THE SUCCESS OF THE TFAP 21

VI. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 27

NOTES 33

REFERENCES 35

APPENDICES

1. History of the Development of the TFAP 412. Underlying Causes of Tropical Deforestation 453. TFAP's Basic Principles 494. Confronting the Cycle of Destruction: The TFAP for Ecuador 515. Proposal for a New Management Structure for the TFAP 57

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people deserve to be recognized for theirspecial role in the production of this report. CherylCort, Libby Halpin and Owen Lynch researched andprepared supporting working papers on issues relatedto NGO participation, indigenous peoples, and swid-den agriculture, respectively. Bruce Cabarle wrotethe appendix on the TFAP in Ecuador, and ChipBarber provided background information on theTFAP for Indonesia. Beth Floyd compiled the resultsof the WRI workshop on TFAP implementationissues. Cheryl, Owen, Bruce, Beth, Libby, Chip,Peter Hazlewood and Anukriti Sud all helped in ourreview and analysis of the contents of national TFAPreports, particularly with regard to the attentiongiven to policy reform and institutional issues.Dennis McCaffrey also provided many ideas and sug-gestions for the paper as it was being developed, andwas a helpful critic as it was finalized.

Tom Fox and Mohamed El-Ashry provided over-all guidance for the research and drafting of the re-port. Their constant encouragement and many help-ful criticisms have greatly strengthened this report.Many other staff members of the World Resources

Institute offered valuable comments on the drafts ofthe report, particularly Gus Speth, Kenton Miller,Walt Reid, Kirk Talbott, and Mark Trexler. The finalmanuscript was greatly improved by the editorial as-sistance of Kathleen Courrier and Diana Page. Andthe report could not have been produced withoutthe able assistance of Faye Kepner and other WRIstaff that contributed to the production process.

We are also grateful to the many reviewers whotook time to comment thoughtfully on the draft re-port. This includes the members of WRI's AdvisoryPanel on Tropical Forests, and a wide range ofspecialists with intimate knowledge of the TFAP andthe problems related to tropical deforestation. Al-though they are too numerous to name individually,we are particularly grateful for the comments andsuggestions received from Jim Barnes, Bob Blake,Antonio Carrillo, Mark Collins, Jim Douglas, ChrisElliott, Louise Fortmann, Robert Goodland, HiraJhamtani, Hollis Murray, Matt Perl, Carlos Pimentel,Ralph Roberts, Jeff Sayer and Monty Yudelman.

R.W.

i i i

FOREWORD

In 1985, our reading of the state of the world'stropical forests and the pace of deforestation forcedus to conclude that an ambitious global campaign in-volving more funds and people than any other en-vironmental action plan ever launched was urgentlyneeded. Our shared sense of the best way to get suchan initiative off the ground was to scour and analyzeall the data then available on tropical forests, to callon international agencies and forestry and agricul-ture experts from around the world to put these ana-lyses into perspective, to search for successfulprojects that might be worth emulating, and to de-velop a budget for getting what we then called Trop-ical Forests: A Call for Action implemented at thenational level in ways that suited each participatingcountry's development needs and natural resourcemanagement challenges.

Five years later, the needs to control deforesta-tion and to reclaim lost forestlands are greater thanever, and the need to take a close, hard look at theplan that has since evolved into The Tropical Forest-ry Action Plan (TFAP) is pressing. Because of WRI'srole in launching the TFAP, we feel a particularresponsibility to assess its successes and failures, itsstrengths and weaknesses, and to recommend howthe process might be improved and better utilized inthe future. Taking Stock is such an assessment.

As Robert Winterbottom's analysis indicates, theoriginal plan was flawed in some respects. The rightsand needs of forest dwelling peoples were notstressed in the original plan, for example, and it wasassumed that increasing funding for the forestry sec-tor would solve problems whose roots reach deepinto economic and social policies made and ob-served outside the forestry sector.

Some parts of the original plan have also beenmisread or simply gone unread. Careful study of ACall for Action must assuage any skeptic's doubtsthat it is simply about trees. Over and again, the im-portance of sustainable agriculture to sustainable for-estry is stressed, and increased attention to land use,forest management for industries, fuelwood andenergy supplies, conservation of ecosystems, publicparticipation, and institution building form the basisof the action plan.

More important, however, is the principal find-ing of WRI's analysis: the actual implementation ofthe TFAP has not lived up to original plans and ex-

pectations. As Winterbottom observes, the plansprang from a widely shared belief that more effec-tive programs in forest conservation and sustainablemanagement, policy reform both within and outsidethe forestry sector, and improved land-use planningand inter-sectoral coordination could help makeheadway against uncontrolled deforestation and thewaste of tropical forest resources; but, many of theinstitutions controlling the TFAP—FAO, donors, andnational governments—seem to have become preoc-cupied with accelerating investment in the forestrysector at the expense of the quality control anddirection needed to make the planning process andthe plan itself succeed.

Taking Stock details a number of urgentlyneeded steps for revitalizing the TFAP process sothat the potential inherent in the effort can be real-ized. Looking to the future, the report stresses fourgoals in particular. First, the TFAP planning processmust meet the needs and safeguard the livelihoods ofpeople who live in or depend on the forest. Second,the plan should help ensure that the remaining areasof tropical forests are used in ways that contribute tonational development, encourage multiple uses offorest lands, and protect biological diversity. Third,the TFAP should mobilize the resources needed toregenerate degraded tropical forest lands and pro-mote sustainable land use around tropical forestareas. Stabilizing land degradation and promotingsustainable development patterns that relieve pres-sure on remaining natural forests are especially highpriorities. Fourth, the TFAP should help stimulateneeded policy reforms both in tropical countries andin development assistance institutions.

Taking Stock is a systematic attempt to call at-tention to flaws in the TFAP and lapses in its im-plementation and to weigh both against the plan'sintended goals, its true potential, and the progressmade so far in spite of set-backs and failings. Signifi-cantly, its conclusions were reached through a par-ticipatory process that was itself influenced by fiveyears of experience with the TFAP. If the recommen-dations are taken with that same spirit, the odds aregood that this tremendously important initiative canbe put right in the 1990s—the decade in which thefate of tropical forests and their inhabitants could besealed.

The research and preparation of the report was

made possible by the generous support of the Rock- also contributed to the development of this assess-efeller Foundation, the Moriah Fund, the W Alton ment, through their support for two workshopsJones Foundation, and the Charles Stewart Mott related to TFAP implementation, and for WRI proj-Foundation. The Atkinson Foundation, the General ect activities in Ecuador, Zaire, Cameroon andService Foundation, the Canadian International Burkina Faso.Development Agency (CIDA), the NetherlandsDevelopment Cooperation, the German Institute for James Gustave SpethTechnical Cooperation (GTZ), the U.S. Agency for PresidentInternational Development, the U.N. Food and World Resources InstituteAgriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Bank

VI

I. INTRODUCTION

This assessment of the Tropical Forestry ActionPlan (TFAP) reflects WRI's growing concern that thePlan will not, as it is currently being implemented,be able to meet many of its intended objectives. Fiveyears after the TFAP was first proposed, importantquestions need answers. Is the Plan making reason-able progress toward its original goals?1 Is the Planhelping to conserve tropical forests and promotewiser use of forest lands and a better life for peoplewho depend directly on tropical forests?2 Will fur-ther support for TFAP's implementation promotesustainable development, policy reforms, and theother actions needed to address deforestation's rootcauses? Will increased development assistance forforestry fully capture the long-term developmentbenefits of tropical forests?

Taking Stock seeks to answer these questions. Itreflects many months of research and analysis atWRI on the Plan's accomplishments and the short-comings encountered in implementing the TFAP.The analysis draws upon the discussions of thetwice-yearly meetings of the TFAP Forestry AdvisorsGroup and a number of status reports and interim as-sessments prepared by WRI, FAO, and various aidagencies.3 It also builds upon the conclusions andrecommendations of several workshops organizedby WRI and others to review the Plan's progress, andon critiques by such organizations as the WorldRainforest Movement, Friends of the Earth, andWorld Wildlife Fund (U.S.).4 The analysis alsoreflects the information and insights that WRI hasgained in working directly on country-level TFAPswith governments, aid agencies, other internationaland national nongovernmental organizations(NGOs), and with local communities involved inplanning and managing forest lands in Africa, Asia,and Latin America.5

Even with the benefit of workshops, otherreports, and experience to draw on, for many rea-sons it is hard to pass judgment on TFAP's record.First, at least three levels of action are involved: pro-motion of international consultation and coordina-tion of the donor agencies; mobilization of supportfor a country-level development planning process;and stimulation of investment and other actions atthe national level to implement TFAPs. Second, theTFAP planning process has been under way for lessthan five years. Third, governments and donors have

tended to count all development assistance for for-estry in the last few years as funding of the TFAP,even if it doesn't fit into the TFAP framework.Fourth, the Plan is a moving target insofar as its con-ceptual framework, guidelines, and implementationprocedures have evolved considerably since 1985.And, finally, different elements and actions pro-posed in the Plan have been emphasized in differentcountries, so there is no clear-cut template to use tomeasure progress.

Different elements andactions proposed in thePlan have been empha-sized in different coun-tries, so there is no clear-cut template to use tomeasure progress.

9V

The difficulty of working with and around theseobstacles will not be lost on the primary audiencesfor this report—the national governments, FAO, theaid agencies, and the Forestry Advisors Group thatare together managing or influencing the Plan's im-plementation and the NGOs and international or-ganizations that are monitoring the TFAP processand the TFAP's impact and effectiveness.

Despite these difficulties and the incomplete na-ture of this assessment, the inescapable conclusionof this paper is that the TFAP effort is in need of a re-commitment to the plan's basic principles and goals,a new institutional framework, more systematicmonitoring, and a more open and accountable man-agement structure. Moreover, Taking Stock, to-gether with various other critiques and assessmentsof the TFAP, underlines the urgent need to make theTFAP planning process more participatory and tofocus it on the identification of strategies for the sus-tainable development and conservation of forestlands. Significant progress in implementing thesereforms should be a precondition for further fundingof development assistance projects identified in theTFAP planning process.

II. TFAP—A PROPOSED RESPONSE TO THEDEFORESTATION CRISIS

The TFAP grew out of a desire to respond moreeffectively to the accelerating loss of tropical forests.The most recent data, however, indicate that thisgoal is still far from being achieved. Some 16 to 20million hectares of tropical forest are being lostevery year,6 compared to an estimated 11 millionhectares a year in 1980.7 In short, the crisis of tropi-cal deforestation is deepening.8 Considering howcomplex the causes of deforestation are, it is not sur-prising that progress in controlling net forest losseshas faltered over the past few years, but the serious-ness of current trends in deforestation is an impor-tant point of departure for any analysis of the TFAP.

BACKGROUND ON THE DEVELOPMENTOF THE TFAP

For more than a decade, beginning in the early1970s, the international community of foresters andenvironmentalists had become increasingly con-cerned about the rapid destruction of tropical forestsand increasingly frustrated at their inability to con-trol tropical deforestation. In a succession of inter-national meetings, statements on the magnitude ofdeforestation and its likely consequences grew morestrident as the analysis of the causes became moreemotive and complex.

In 1983, the Committee on Forest Developmentin the Tropics (CFDT)9 charged FAO with preparingan "Action Programme" to identify the priorityproblems and corresponding proposals for action.This initiative was principally driven by the commit-tee's concern that development assistance for forest-ry was stagnating even though the need for suchassistance was increasing. Despite the urgency of de-veloping such an action program, by the end of1984, it was unclear to many observers if or whensuch a program would be completed by FAO.

Beginning in May 1984, another effort began inparallel. The World Resources Institute convened ameeting of some 75 leaders of science, government,industry, and citizen's groups from 20 countries todiscuss "The Global Possible: Resources, Develop-ment and the New Century." The conference pro-duced an "agenda for action" on such pressingtopics as population stabilization, poverty allevia-tion, the conservation of biological diversity, agri-cultural development, and the control of tropical

deforestation. In the case of tropical forestry, a num-ber of goals and suggested priority actions wereoutlined.

As a follow-up to the Global Possible Confer-ence, WRI organized an International Task Force tofurther develop a program for "arresting and ulti-mately reversing the destruction of tropicalforests."10 This Task Force began work in December1984 and released their draft report in June 1985-The Task Force report, "Tropical Forests: A Call forAction" was finalized and published in October1985.

This "Call for Action" was developed with thesupport of private foundations and a number of de-velopment assistance agencies, including the WorldBank, the Canadian International DevelopmentAgency, the U.S. Agency for International Develop-ment (USAID), the Netherlands Development Coop-eration, and the United Nations DevelopmentProgramme. FAO was invited to take part in the TaskForce, but declined.

Coincidentally, spurred on by the work of theWRI Task Force, the FAO convened an informal ex-pert meeting in March 1985 to review proposedaction programs in five main areas related to the de-velopment and rational utilization of tropical forests.These proposals were endorsed in June, 1985 by theCFDT. In October 1985, FAO formally released theTropical Forestry Action Plan (TFAP), with a viewtowards "the harmonizing and strengthening of themuch-needed cooperation in tropical forestry."

These two "roots" of the TFAP came togetherin July 1987, when FAO, the World Bank, UNDP,WRI, and the Rockefeller Foundation convened ahigh-level meeting on tropical forests at the BellagioConference Center in Italy. This meeting wasprimarily aimed at building political awareness ofthe need for more effective action and acceleratedinvestment to control tropical deforestation. At Bel-lagio, a new, summary version of the TFAP was pre-sented. This version drew on both FAO's 1985 Planand WRI's "Call for Action," modified to a degreeby the early criticisms of both reports. The revisedTFAP booklet noted the need to "avoid the costlymistakes of massive development projects" and to"plan and coordinate projects to avoid wasting ordestroying forest resources or jeopardizing forestconservation areas." It also pointed to the threat

posed by deforestation to indigenous people. Thesechanges aside, the basic objectives and approach ofthe "new" TFAP remained much the same: to over-come the perceived lack of political, financial, andinstitutional support for combatting deforestationthrough a "common framework for action."11

The "Statement" of the Bellagio meeting notedthe economic and environmental costs of deforesta-tion, as well as its causes. According to the report,more attention was needed in the TFAP's implemen-tation to quantifying the costs of inaction, incor-porating recommendations for action into nationaldevelopment plans, promoting community partici-pation, encouraging the private sector, initiatingpolicy reform within both national governments andaid agencies, protecting forest ecosystems, integrat-ing forestry into broader land-use concerns,strengthening research, monitoring tropical defor-estation, and coordinating international action. (SeeAppendix on the History of the Development of theTFAP.)

FAO and various aid agen-cies viewed the TFAP pri-marily as a mechanism toharmonize developmentassistance in forestry,while WRI and others sawthe TFAP as a vehicle tolaunch a broadly-basedprogram to address the rootcauses of deforestation.

99

As indicated in the foregoing, very brief historyof the development of the TFAP, a range of agenciesand organizations were involved in the conceptionof the plan. Grassroots development organizationsand communities living in the tropical forests, how-ever, were not well represented in the early stages ofthe development of the global TFAP framework.Furthermore, although the principal "founders" ofthe TFAP joined together at the 1987 Bellagio meet-ing to encourage the adoption of the TFAP as a plan-ning framework, different expectations of the TFAPpersisted. FAO and various aid agencies viewed theTFAP primarily as a mechanism to harmonize de-velopment assistance in forestry, while WRI andothers saw the TFAP as a vehicle to launch abroadly-based program to address the root causes ofdeforestation.

TFAP's PRINCIPAL THEMES ANDANTICIPATED BENEFITS

Careful scrutiny of the TFAP makes it clear thatthe plan has indeed provided a broad framework foraddressing the challenges and needs related to theconservation and development of tropical forests.Over the past five years, the TFAP planning frame-work has maintained a focus on five inter-relatedareas:

1. Forestry in Land Use. Activities aimed at the in-terface of forestry and agriculture and at morerational land use through community forestry,integrated watershed management and desertifi-cation control, and land assessments and forestresource inventories. To include planting ofmulti-purpose trees on farms, to help combatdeclining soil fertility and shortages of poles,fuelwood and other forest products.

2. Forest-based Industrial Development. Activitiesaimed at promoting appropriate forest-basedindustries—among them, small-scale "cottage"enterprises and other forest-based income-generating activities in rural areas, as well as in-dustrial plantations and the expansion of forestproducts exports.

3. Fuelwood and Energy. Activities aimed atrestoring a balance between fuelwood supplyand demand, by increasing production andreducing demand of wood fuels; also, includedprograms to develop wood-based energysystems.

4. Conservation of Tropical Forest Ecosystems.Activities aimed at conserving, managing, andusing forests' genetic resources, including pro-tected areas management and the managementof forests for sustainable production.

5. Institution Building. Activities aimed at remov-ing the institutional constraints to conservingtropical forests and using them wisely, includingsupport for training, research, extension; great-er institutional support to NGOs and the busi-ness community; the strengthening of publicforestry agencies; and the revision of laws andpolicies to better integrate forestry into nationalplanning.12

A look back at the original plan also shows thatthe anticipated benefits of the TFAP were as broad asthe plan's scope of action. Implementation of the

TFAP was expected to "contribute decisively to im-proving life in developing countries."13 Benefitswere to include:

• more jobs, income, and a stimulus to rural de-velopment, as well as increased flows toproducts and services from sustainably managedforests;

• improved food security, agricultural productiv-ity, and land use;

• more dependable sources of fuelwood;

• increased exports of forest products, with morevalue added locally;

• increased local community involvement in localforest management; and

• increased protection of wilderness, wildlife, andthe genetic diversity of forests.14

LIMITATIONS OF THE TFAP GLOBALFRAMEWORK

As broad-based as these goals and expectedbenefits were, they were to be achieved mainly,though not exclusively, by increasing developmentassistance to the forestry sector. The idea was thatboosting investment, technical assistance, and sup-port for forestry would brighten the prospects forinformation collection, program development, coor-dination among sectors, increased political support,and forestry's enhanced contribution to nationaldevelopment.

While the five theme areas of the TFAP may notaddress all of the major causes of tropical deforesta-tion, progress in each of these areas is crucial to suc-cess in controlling deforestation and in promotingthe sustainable development of tropical forests. {SeeAppendix on Underlying Causes of Deforestation.)Also, unlike the FAO's version of the TFAP, the WRITask Force report underlined the importance ofstimulating changes in the agricultural sector as wellas in the forestry sector. The "Call for Action" re-port recommended that at least 30 percent of theproposed 5-year investment of $8 billion be agricul-ture-related so as to provide farmers and landlesspeople with alternatives to the destruction of forestsand woodlands.15 Nonetheless, the TFAP has limiteditself largely to assistance in the forestry sector.

A related question of degree is how far fromconventional approaches to development assistancethe new initiatives would go. Although the TaskForce report confirmed the need to work with exist-

ing aid agencies and national governments, the "Callfor Action" did signal the need for significant depar-tures from a "business as usual" approach to de-velopment assistance. Increased investment was tobe linked to policy reform, and priorities shifted soas to give more attention to forest conservation,agroforestry, and other neglected areas. The TaskForce also cited the need for the full participation oflocal communities, NGOs, and other groups that hadnot been sufficiently involved in development plan-ning and project implementation in the past.

It was a mistake to viewthe TFAP as primarily atechnical planning exer-cise within the forestrysector when, in fact, a newpolitical planning processwas needed to analyzetrade-offs and to balanceconflicting demands onforest lands.

Neither the FAO's TFAP nor the WRI Task Forcereport were sufficiently clear, however, about theneed for new institutional mechanisms to implementsuch a broadly based and participatory developmentstrategy. In retrospect, it was a mistake to view theTFAP as primarily a technical planning exercisewithin the forestry sector when, in fact, a new polit-ical planning process was needed to analyze trade-offs and to balance conflicting demands on forestlands.

For example, both plans apparently assumedthat there would be few conflicts between local andnational interests in an accelerated program of de-velopment assistance in forestry, and that the contri-bution of the forestry sector to the national econo-my and to a country's export earnings could beexpanded while simultaneously protecting the liveli-hoods and meeting the needs of forest-dependentlocal communities. Increased production of woodproducts and intensified forest management was alsoassumed to be compatible with safeguarding a coun-try's biological resources and maintaining the en-vironmental services of tropical forests. A tendencyto overlook or minimize the significance of suchtrade-offs has made it difficult to achieve the fullrange of the TFAP's anticipated benefits.

III. ORGANIZATION OF THE TFAP PLANNING PROCESS

GUIDELINES AND PROCEDURES FORTHE TFAP

The key to any assessment of the TFAP is an un-derstanding of both what is intended to happen andwhat actually happens in-country as part of the na-tional level TFAP planning process. (See Figure 1.)The process is initiated or sanctioned by a formal re-quest to the FAO or a prospective donor agencyfrom the interested national government. Once theofficial request has been received, the TFAP Coor-dinating Unit of FAO16 takes the lead in advising aidagencies that may want to provide core funding for

the sector review or otherwise support its prepara-tion and implementation.

Next, an "issues paper" is prepared to highlightthe major obstacles to developing the forestry sec-tor. Typically, the issues paper is based on informa-tion available in FAO and aid agency files, and ondata provided by the host-country government. Theissues paper is reviewed by the government and thenused as a basis for preparing terms of reference forthe sector review mission and its individual teammembers. The issues papers and terms of referencefor sector reviews are generally treated as internal,working documents by the aid agencies and the na-

Figure 1. FAO's Process for Preparing a National Forestry Action Plan

Preparatory Phase

• Request to FAO from national government

• Identification of lead donor agency

• Preliminary mission of international team leader tocountry to work with national team leader

• International and national team leaders prepare IssuesPaper on basis of existing information

• Government reviews draft Issues Paper; Issues Paper cir-culated as widely as possible

• Issues Paper finalized and circulated to all partiesinvolved

• Identification of sectors of intervention; terms of refer-ence for consultants identified, securing participation ofNGOs & local people in process; program and schedulefor mission

• National counterpart consultants and other participatingdonor agencies confirmed

• Seminar or workshop (type I roundtable) organized tobring together all interested national partners

Execution Phase

• Donor-sponsored consultants carry out field missions •

Principal conclusions presented for discussion with(Note: type II roundtable may come before finalizationof draft report, with provisions for incorporating the

National roundtable (type II) to obtain political involve-ment and support from all parties

governmentPreparation of draft mission report and submitted togovernment

• Draft report circulated within government and par-ticipating agencies; revisions made based on commentsreceived

• Report finalized and adopted by government

seminar's comments into final report)International roundtable (type III) government and par-ticipating donors discuss effective implementation of theNational Forestry Action Plan

Follow Up PhaseFollow up project identification and preparation mis- • Project appraisal, funding and implementationsions by FAO or by participating donor agencies; assist „ . ,. . . . T,.^,.-„.»,

' J r v t> & • periodic review with FAO/TFAP secretariat to reviewprogress of implementation

government in preparing more detailed projectproposals

(Source: Annex 2 "Basic Checklist and Schedule of Activities for the Preparation and Execution of TFAP Sector Review Mis-sion" from Guidelines for Implementation of the TFAP at Country Level, FAO 1989)

tional government. Only rarely are they formallyadopted or circulated beyond the circle of specialistsparticipating in the review mission.

A "type I" roundtable meeting is sometimes or-ganized by the government before the sector reviewmission is recruited and fielded. At such a meeting,representatives of government agencies and otherorganizations that may have helped prepare the na-tional TFAP discuss the steps needed. Once the sec-tor review mission has been completed and a nation-al TFAP drafted, a "type II" roundtable meeting isgenerally held at which technical staff and agencyrepresentatives go over the draft sector reviews andnational action plans.17

The reports are then finalized, distributed to do-nor agencies, and formally presented to a "type III"roundtable meeting convened to coordinate fundingfor the National Action Plan. In theory, after thisthird meeting, investment commitments are thenconfirmed in discussions between the donor agen-cies and the national governments, and other actionsare taken to implement the TFAP. In all, preparingand executing a TFAP mission takes about 18 monthsfrom the time of the initial request to completion.18

PARTICIPATING AGENCIES ANDORGANIZATIONS

The principal institutions most directly respon-sible for the implementation of the TFAP have beenthe two inter-governmental bodies which overseeFAO's Forestry Department, namely the Committeeon Forest Development in the Tropics (CFDT) andthe Committee on Forestry (COFO).1* The FAO For-estry Department itself (including the FAO/TFAPCoordinating Unit), other UN agencies (UNDP,UNEP, UNESCO, UNSO, WFP, ILO), and representa-tives of multilateral and bilateral aid agencies havebeen directly involved as "participating agencies" inthe planning and implementation of the TFAP. Gov-ernments of donor countries have been representedmost often by the chief forestry advisor of their de-velopment assistance agencies. Developing countrygovernments have been involved primarily throughthe national Forestry Departments (which, in mostcases, involves the Ministry of Agriculture), as wellas through other government agencies (such as theMinistry of Planning and/or Finance) that negotiatedevelopment assistance.

The FAO has been charged by its statutory bod-ies (CFDT and COFO) with the overall coordinationof the implementation of the TFAP. In most country-level TFAP planning exercises,20 a designated donoragency takes the lead in funding and organizing aforestry sector review mission and related follow-up

activities, in concert with the FAO and the hostcountry government agencies. According to the FAOguidelines for implementing the TFAP, "the HostGovernment would arrange for the involvement ofnational NGOs and the private sector."21

THE TFAP FORESTRY ADVISORSGROUP

Over the past five years, an unofficial "ForestryAdvisors Group" has met every six months to pro-mote information sharing and collaboration amongthe various aid agencies, national governmentagencies, and other organizations involved in im-plementing the TFAP. The nine regular meetings ofthe Advisors Group held since November 1985 haveprovided a forum for planning and organizing thenational sector review missions, going over theresults of such missions, and coordinating follow-up.The Advisors Group meetings have also provided asignificant opportunity for dialogue between TFAP'sfunding agencies and a number of NGOs with an in-terest in the TFAP.22

The Advisors Group meetings have emerged asthe single most important forum for shaping thescope and procedures of national TFAP planning ex-ercises. The "general terms of reference" for TFAPmissions were outlined at the first Advisors meetingin November 1985 and progressively expanded onthe basis of discussions in the Advisors Group meet-ings to include more explicit guidance to missionteam leaders.23 As the need for more systematicmonitoring of the TFAP has been recognized, theAdvisors Group has played an important role instimulating the FAO Coordinating Unit to developindicators for assessing the results of the TFAP andto organize a review of these results.

Despite its crucial role, the Advisors Group hascome up against serious impediments. It has no in-stitutional stature or authority to insure compliancewith the TFAP guidelines or to otherwise influenceTFAP planning at the national level.24 Also, as thenumber of countries participating in the TFAP hasincreased, and as the range of issues related to TFAPimplementation has multiplied, the Advisors Group'smeeting agenda has become so crowded that there isseldom enough time to fully debate or resolve key is-sues. Most agenda items relate to the implementationand coordination of TFAP country-level exercisesand to various funding issues or other bottlenecks ofdirect concern to the aid agencies. Only occasionallyhas the Advisors Group had enough time to wrestlewith the full implications of some of the conceptualor structural problems with the TFAP's frameworkand approach.

IV. RESULTS OF TFAP IMPLEMENTATION

PARTICIPATION OF NATIONALGOVERNMENTS

The intent of the TFAP from the beginning hasbeen that the plan would be implemented at thenational level through the preparation of nationalTFAPs. In 1986, FAO reported that more than 25countries were involved in one stage or another ofthe planning process. Since then, the number ofcountries participating has steadily grown. (See Fig-ure 2.)

Figure 2.Number of Countries Participating in TFAP

1986-198980

70-

60-

50-

40

30H

20^

10-

1986 1987

| | Requests

| | Ongoing FSR

| | Complete FSR

Roundtable III

TOTALS

1988 1989

1986 1987 1988 1989

15 22 8 11

5 19 38 42

6 5 13 12

0 0 1 9

26 46 60 74

As of March 1990, seventy countries that to-gether possess roughly 60 percent of the world's re-maining tropical forests have completed or started toprepare national action plans for the forestry sec-tor.25 Not all countries, however, are following

FAO's guidelines for preparing national TFAPs. Manyof the Asian countries are developing a "ForestryMaster Plan" (FMP), based on guidelines developedby the Asian Development Bank. The planning pro-cess for FMPs places comparatively more emphasison quantitative analysis of the projected supply anddemand of forest products and generally incor-porates a longer-term, more detailed analysis ofdevelopment prospects in the forestry sector.

Straying from the guidelines for national TFAPpreparation is not the only way that countries have

itAs of March 1990, seventycountries that togetherpossess roughly 60 percentof the world's remainingtropical forests have com-pleted or started to pre-pare national action plansfor the forestry sector.

99

modified or "adapted" the proposed TFAP planningprocess. As indicated in Table 1, many countrieshave jumped from an issues paper (prepared in mostcases by FAO or a lead donor agency) directly to asector review and type II roundtable meeting. Onlyeight countries organized an in-country type Iroundtable meeting to discuss the organization ofthe sector review missions, the major problems to beaddressed, and other issues early in the TFAP plan-ning process.

In a number of countries, the TFAP planningprocess has clearly lost momentum. Of the 27 coun-tries that had initiated TFAPs as of 1986-87, onlyeight have formally adopted their plans and subse-quently presented them to potential donors. In theDominican Republic, Panama, Guyana, Fiji, Malay-sia, and Sierra Leone, the TFAP forestry sector re-view and draft national plan were prepared, buthave languished for months without being formallyadopted by the national government and presentedto a donors roundtable meeting; consequently, fund-

ing for these national plans has not yet been mobi-lized and the proposed actions haven't been imple-mented. In Cuba, Mauritania, Mali, and Nicaragua,the planning process has been stalled in recent yearsor has made only slight progress. In Kenya and pos-sibly in Ethiopia, it appears that the TFAP planningprocess will be repeated so as to improve on theTFAP prepared several years ago.

kk

Only rarely have NGOsplayed an important rolein preparing the nationalTFAPs and influencing theoutcome of the planningprocess.

91

AID AGENCY SUPPORT OF THE TFAP

Among most donor agencies, response to theTFAP (at least in terms of financial commitments)has been relatively strong. Since 1985, more than 40aid agencies, which together account for virtually allof the official development assistance provided tothe forestry sector, have collaborated to support theorganization of more than 50 country-level forestrysector reviews (See Table 2). Typically, these sectorreviews involve teams of a dozen or more technicalexperts and several person-years of consultants andother technical assistance and logistical support val-ued at over $700,000 per country.

FAO and UNDP have most often been the leadagencies for the national sector review missions, butseveral sector reviews or related TFAP missions havealso been led by the World Bank, CIDA, the Nether-lands, and France, and the AsDB has coordinated thepreparation of a series of FMPs. FINNIDA, ODA,SIDA, GTZ, and USAID have also provided leader-ship for TFAP missions. Participation in the TFAP bythe IDB and the AfDB, as well as such bilaterals asJICA, NORAD, and Switzerland, however, has beenrelatively modest. In a number of countries, onlyone or two aid agencies have been recruited to assistin the planning exercise. Seven TFAPs have beenprepared by national teams of experts, with very lit-tle assistance from FAO or other aid agencies.

NGO AND COMMUNITYPARTICIPATION

NGOs—presumably a good vehicle to achievepopular participation in the TFAP planning process—

have been consulted in a number of national plan-ning exercises. However, only rarely have theyplayed an important role in preparing the nationalTFAPs and influencing the outcome of the planningprocess.26 Of the 25 countries for which WRI hasreasonably good information from NGOs, only sevenheld meetings for NGOs to voice their views, and sixof these roundtables were organized at the initiativeof the NGOs. (See Tables 1 and 3.) Few NGOs wereinvolved early in the review of issues papers andterms of references for national TFAPs. In ten totwelve countries, NGOs were invited to participatein TFAP roundtable meetings and seminars or askedto comment on TFAP reports. NGOs (both local andinternational NGOs) played a substantial role in thepreparation of TFAP reports in only seven or eightcountries.

A comprehensive survey of NGOs and theircapabilities was prepared in seven countries, includ-ing three surveys conducted at the initiative of theNGO community. In at least seven countries sur-veyed by WRI, there was minimal or no involvementof local, national, or international NGOs. In five tosix countries, NGOs submitted project proposals aspart of the action plans; but, in general, they lackedthe technical support needed to participate fully. Inthe few countries where NGOs have received someassistance to make it easier for them to participate inthe formulation of national TFAPs, the support hasmost often been provided by international NGOs, of-ten using resources provided by a donor agency par-ticipating in the TFAP exercise.

Such international NGOs as IUCN, WWF, IIED,TNC, CI, and WRI have provided technical supportdirectly to sector review missions or otherwiseplayed a significant role in TFAP planning exercisesin Cameroon, Mali, Tanzania, Zaire, Bolivia, CostaRica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Papua New Guinea, andLaos. Their involvement has helped to increase theattention given to conservation, policy reform, landuse, and inter-sectoral linkages. More direct partici-pation of local NGOs and the people they representis essential, however, to better articulate the rightsand interests of forest dwellers and other groupsomitted from the planning process.

PROPOSED INVESTMENT AND FUNDINGOF NATIONAL TFAPs

Although data on the agencies participating inTFAP exercises is readily available from the FAO, in-formation on proposed and actual investments in theTFAP is much harder to obtain. A review of elevennational TFAPs for which detailed information isavailable indicate that investment levels of about

10

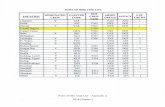

Table 1. Status of Selected National Forestry Action Plans as of May 19901

CountryArgentinaBelizeBoliviaBurkina FasoCameroonColombiaCongoCosta RicaCote d'lvoireDominican Rep.EcuadorFijiGhanaGuineaGuyanaHondurasIndonesiaJamaicaKenyaLaosMalaysiaMaliMauritaniaNepalNicaraguaPanamaPapua New GuineaPeruPhilippinesSierra LeoneSomaliaSudanTanzaniaZaire

RequesttoFAO

4/8711/8710/86

1/876/863/874/878/87

5/8610/87

*6/867/87

9/876/886/8619876/8619879/86

10/876/86

5/86

2/8710/87

IssuesPaper

1/889/879/89 -9/86

*4/89

*7/86

11/86#

10/86

11/87

1/86

6/8711/889/86

3/892/89

12/88

NationalRoundtable

(type I)

*9/89

10/87

*6/87

**

o

1/87

NGOWorkshop

oo

oo

9&H/89 +o

4/89 +1988/89 +

oooooo

o

o9/88 +

o1987

oo

8/89 +4/88 +

SectorReview

Completed11/886/884/88

5/87

9/869/872/90

12/884/868/86

11/88

9/8910/869/89

6/885/895/87

**

19852/89

10/89

DraftPlan9/891989

10/88

5/871/88

3/902/871/88

10/88

5/881/894/875/90

*5/88

4/88

6/889/8919877/897/89

4/863/892/90

NationalRoundtable

(type II)

1/89

1/88

11/89

4/882/90

10/88

3/89

5/9011/89

7/88

6/88

8/89

4 & 8/89

FinalPlan

5/89

6/884/89

12/88

1/87

3/903/87

12/88

3/88

3/90

9/895/90

Internat'lRoundtable

(type III)11/88

7/89

5/896/89

5/90

oo

1/88

5/90

5/88

4/902/89

5/90

12/89

LeadAgencyNational

ODAUNDP/FAOGTZ/CILSSUNDP/FAONetherlandsUNDP/FAONetherlandsFAO/WBCPUNDP/FAO

NationalUNDP/FAOFAO/WBCP

FranceCIDA

NationalNational

UNDP/FAOWorld BankUNDP/FAO

NationalFrance

UNDP/FAOAsDBSIDA

UNDP/FAOWorld Bank

CIDAAsDB

UNDP/FAOUNDP/FAOWorld Bank

FINNIDACIDA

KEY:* completed—but date uncertaino this activity was not carried out+ this activity was an NGO initiative

1. Compiled from FAO/TFAP Coordinating Unit, "TFAP Update" Nos. 1-16 and TFAP Forestry Advisors GroupMeetings Summary Reports, 1985-1989.

Table 2. Participation of Development Assistance Agencies in National TFAPS1

Country

Argentina

Belize

Bhutan

Bolivia

BurkinaFaso

Burundi

Cameroon

Colombia

Congo

Costa Rica

Coted'lvoire

Cuba

DominicanRepublic

Ecuador

EquatorialGuinea

Lead Agency

National

ODA

AsDB/DANIDA

UNDP/FAO

FRG/CILSS (?)

UNDP/FAO

Netherlands

UNDP/FAO

Netherlands

FAO/WBCP

National

UNDP/FAO

FAO

FAO/WB

Participating andInterested Aid Agencies

CIDA, FAO, IDB, JAPAN,UNDP

CIDA, FAO, USAID

FAO, ODA, Switzerland,UNDP, WFP, WB

Belgium, FRG, IDB, ODA,Spain, Switzerland,Netherlands, UNDP

CIDA, EEC, FAO, France,FRG, Switzerland, Nether-lands, UNDP

FAO, WB

AfDB, CIDA, EEC, France,FRG, Japan, ODA, WB,WFP

CIDA, FAO, France, FRG,IDB, Spain, UNDP, WB

AfDB, EEC, FAO, France,FRG, WB

FAO, IDB, Italy, Japan,ODA, Switzerland, UNDP,USAID

CIDA, France, UNDP,UNEP, WB

FAO, UNDP, USSR

CIDA, FRG, IDB, Israel,USAID

Italy, FRG, Netherlands,ODA, Switzerland, UNDP

EEC, France

Country Lead AgencyParticipating andInterested Aid Agencies

Haiti UNDP/FAO

Ethiopia WB/UNDP/FAO AfDB, CIDA, FINNIDA,France, Italy, SIDA, Swit-zerland, WFP

Fiji

Gabon

Ghana

Guatemala

Guinea

Guyana

UNDP/FAO

France

FAO/WBCP

USAID

France

CIDA

AsDB, Australia, EEC,FRG, IDB, Japan, NewZealand, ODA•>

CIDA, ODA

FRG, Netherlands, UNDP

CIDA, FAO, FRG, EEC,ODA, UNDP, USAID

FAO, FRG/KfW, IDB,ODA, UNDP

Honduras National

Indonesia National

Jamaica UNDP/FAO

Laos UNDP/FAO

Lesotho UNDP/FAO

Madagascar UNDP/FAO

Malaysia National

Mali France

Mauritania UNDP/FAO

Mexico FAO

Nepal AsDB/FINNIDA

Nicaragua SIDA/NETHER-LANDS/FAO

Pakistan AsDB

Panama UNDP/FAOPapua New WBGuinea

Peru CIDA

CIDA, FAO, France,UNDP, USAID, WB

CIDA, EEC, FAO, FINNIDA,FRG, Italy, Japan, ODA,Spain, Switerland, Nether-lands, UNDP, USAID

AsDB, CIDA, FAO,FINNIDA, France, FRG,Japan, ODA, Netherlands,UNDP, USAID, WB

CIDA, ODA, UNEP

AsDB, Australia, EEC,France, SIDA, WB

AfDB, EEC, IFAD, ODA,SIDA, USAID

AfDB, France, FRG, Swit-zerland, USAID, USSR, WB

AsDB, CIDA, FAO, France,Japan, UNDP, WB

AfDB, CIDA, EEC, FAO,FRG, Switzerland, Nether-lands, UNDP, UNEP,USAID, WB, WFP

AfDB, France, DANIDA,EEC, Italy, Netherlands,UNEP, UNSO, USAID, WB

FINNIDA, FRG, IDB, ODA,Spain, UNDP, USAID, WB

IDRC, CIDA, FAO, EEC,JAPAN, NORAD, ODA,Switzerland, Netherlands,UNDP, USAID, WB

CIDA, NORAD, UNDP,FINNIDA

CIDA, FAO, FRG, ILO,NORAD, Netherlands,ODA, Switzerland, UNDP,USAID, WB

IDB, Japan, ODA

AsDB, Australia, FAO,FRG, Japan, New Zealand,UNDP

FAO, France, FRG, IDB,Japan, Spain, Switzerland,Netherlands, UNDP,UNEP, USAID, WFP

1. From FAO, "Donor Participation List," November 25, 1989. Note: only includes countries which are preparing a nation-al TFAP; only lists official multilateral and bilateral development assistance agencies (see explanation of abbreviations/acronyms at the end of the list).

12

Table 2. Continued

Country Lead AgencyParticipating andInterested Aid Agencies Country Lead Agency

Participating andInterested Aid Agencies

Philippines AsDB/FINNIDA CIDA, FRG, Italy, Japan,

Senegal

SierraLeone

Somalia

Sudan

Surinatne

Tanzania

KEY:Acronym

AfDBAsDBCDCCIDADANIDAEEC

FAOFINNIDAFRGIDBIDRCIFAD

Netherlands, UNDP,USAID

UNDP/FAO CIDA, EEC, France, FRG,Japan, Netherlands, USAID

UNDP/FAO FRG, ODA

UNDP/FAO AfDB, EEC, FINNIDA,FRG, Italy, ODA, UNSO,WB

WB FINNIDA

FAO Netherlands

FINNIDA AfDB, DANIDA, EEC,FAO, FRG, Japan, Nether-lands, NORAD, ODA,SIDA, Switzerland, UNDP,WB

Agency

African Development BankAsian Development BankCommonwealth Development CorporationCanadian International Development AgencyDanish International Development AgencyEuropean Development Fund/European

Economic CommunityU.N. Food and Agriculture OrganizationFinnish International Development AgencyFederal Republic of GermanyInterAmerican Development BankInternational Development Research CentreInternational Fund for Agricultural

Development

Thailand

Togo

Venezuela

Viet Nam

Zaire

Zimbabwe

CARICOM

Acronym

NORAD

ODASIDAUNDPUNEPUNSO

USAIDUSDAUSSRWBWFP

UNDP/FINNIDA AfDB, DANIDA, EEC,FAO, FRG, Japan, Nether-lands, NORAD, ODA,SIDA, Switzerland, UNDP,

WB

UNDP/FAO EEC, France, FRG, WB

FAO IDB, Netherlands, UNDP

UNDP/FAO SIDA, Switzerland, USSR,WB

CIDA AfDB, FAO, France, FRG,EEC, UNDP, WB

: WB AfDB, CIDA, FRG, ODA,USAID, WB

FAO/ODA CARICOM DB, CIDA, EEC,USAID, USDA

Agency

Government of Norway, Ministry ofDevelopment Cooperation

U.K. Overseas Development AgencySwedish International Development AgencyUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Environment ProgrammeUnited Nations Sudano-Sahelian Office

(New York)U.S. Agency for International DevelopmentU.S. Department of AgricultureSoviet UnionWorld BankWorld Food Program (U.N.)

U.S.$28 million per country per year are being pro-posed. (See Table 4.) If all seventy countries nowpreparing and implementing national TFAPs requirethe same amount on average, nearly U.S.$2 billionwill be needed—roughly double the current levels ofdevelopment assistance in the forestry sector.

Forestry in land use and forest industries to-gether account for more than half the proposed in-vestment in 12 national TFAPs that have recentlybeen completed, while forest conservation and fuel-wood programs only amount to 20 percent of thetotal investment. However, these global averages ob-scure comparatively larger shares earmarked for for-est conservation or land use in a number ofcountries.

Overall, funding commitments in the forestrysector have at least doubled over the past five years,from some $500 million annually to more than 81billion a year in official development assistance inthe TFAP's five general areas. (See Table 5.) Over thepast year or two, the World Bank has committed it-self to tripling investment in forestry, and the UKOverseas Development Administration pledged 100million pounds over three years to the TFAP. TheFederal Republic of Germany (via the KfW Bank andGTZ) has also sharply increased the amount of lend-ing and assistance earmarked for forestry, and fund-ing by USAID of forestry projects increased from $50million in 1988 to $72 million in 1989-

How does this support break down among the

13

Table 3- Summary of NGO/Local Community Participation in TFAP Activities in Selected Countries

Extent of NGO/community participation

1. TFAP exercise includes survey ofNGOs

2. NGOs consulted in preliminarystage

3. NGOs submitted reports forTFAP

4. NGOs reviewed TFAP draftreports

5. NGO comments incorporated intofinal drafts

6. NGOs attended TFAP seminars/workshops

7. NGOs presented papers atseminars

8. Local NGO members of natT TFAPmission or steering committee

9. Technical support provided to localNGOs for participation in TFAP

10. NGOs submitted project profilesfor funding consideration

11. Plans identify NGOs in projectimplementation

12. Projects to give technical assistanceto NGOs

13. NGOs involved represent conserva-tion issues

14. NGOs involved represent rural de-velopment issues

15. International NGOs involved in pre-paratory/mission/follow-up stage

BF

1S

0

M

S

0

0

M

G

1M

CAM

1S

0

1)

M

M

0

0

0

M

M

S

s

G

CI

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

AFRICAGHA MAL SEN

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

s

M

M

G

1S

0

s

G

G

1M

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

M

SL

0

0

1M

0

M

M

0

0

0

0

0

0

s

TAN

12VG

S

M

S

G

S

M

VG

VG

G

S

VG

G

ZAI

12G

S

S

s

s

M

M

S

G

G

FIJ

0

0

M

M

0

0

S

IND

0

0

0

0

0

M

0

0

0

0

0

G

s

M

ASIAMYA NEP

0

0

M

0

s

M

0

M

M

S

G

M

M

S

M

PNG

12M

S

M

0

0

s

s

G

G

G

S

G

PHI

0

M

0

M

M

S

0

0

BEL

0

0

M

0

0

s

M

0

BOL

S

G

M

G

G

G

S

S

G

M

COL

0

M

M

G

S

G

S

S

s

s

s

s

LATIN AMERICACOS DR ECUHON

12G

G

0

M

M

G

0

G

G

0

VG

0

G

G

G

S

s

s

s

s

G

M

G

0

1G

M

G

S

S

s

0

G

1

s

G

G

G

G

0

0

0

M

0

0

s

M

M

0

NIC

G

G

S

s

PAN

G

S

S

s

s

s

G

M

PER

0

s

G

M

G

M

S

S

0

G

M

M

ASIA

KEY: 0 = none/no, M = minimal/very limited, S = modest/some, G = good/yes, VG = very good, shaded blank = insufficient information.1 = NGO initiated, 2 = goverment/donor supported.

COUNTRIES COVERED ABOVE:AFRICA

Burkina Faso SenegalCameroon Sierra LeoneCote d'lvoire TanzaniaGhana ZaireMali

FijiIndonesiaMalaysia

NepalPapua New GuineaPhilippines

LATIN AMERICABelize EcuadorBolivia HondurasColombia NicaraguaCosta Rica PanamaDominican Republic Peru

Table 4. Assignment of National Priorities by TFAP Theme1

ProposedAnnualInvestments:

AFRICA

CameroonGhana3

Tanzania

Forestryin Land

UseUS$m/annum

6.31

14.7

%

23%.4

41

LATIN AMERICA & CARIBBEAN

BoliviaColombiaDominican

Republic3

HondurasJamaicaPanamaPeru

ASIA

Nepal3

Papua NewGuinea

Total ProposedInvestment4

Percent of total(average for 12countries)

5.920

117

53

14.5

27

0.9

118

36%

26.544

.550482229

.8

4

Fuelwoodand

EnergyUS$m/annum

0.8827%

0.96

1.91

283.20.40.355.3

49

0

14

4%

%

3%

3

8.53

943

10

0

ForestIndustries

US$m/annum

7.42.49.4

74

2.511.87.5

16

17.8

3.8

80.6

24%

%

27%4424

319

463

175532

31

17

Conservationof Ecosystems

US$m/annum

2.306.7

2.98.9

.24

.881.92.35

5.7

16

53

16%

%

9%0

18

1319

42.5

18179

10

72

InstitutionsUS$m/annum

10.31.65.4

4.611.5

1.412.2

1.30.529.8

5.7

1.5

65-8

20%

%

38%2914

2125

2235134

19

10

6.6

TotalAnnual

Investment2

US$m/annum

275.5

37

22.345.5

5.634.310.613.750.6

57

22.2

331.3

100%

NOTES:

(1) The figures refer only to proposed (not confirmed) investment, as outlined in the currently available documentation for na-tional TFAPs. Also, note that investment in one program area may have direct and indirect impacts on investment in severalother areas and that the absorptive capacity and funding requirements often differ in each program area; that the absorptivecapacity and funding requirements often differ in each, a small investment in one area may address the major needs, while an-other program area may absorb large amounts for infrastructure.

(2) Figures represent estimated annual level of needed investment; derived from review of total investment proposed over differ-ent planning periods (generally five years).

(3) In this case, investment for "Fuelwood and Energy" programs was not separated, but included in the Forestry and Land Useprogram. For overall analysis, joint proposed investments are calculated into Forestry and Land Use figures.

(4) Total for proposed annual investment in TFAP programs, in 12 countries.

various action programs of the TFAP? Because assis-tance programmed within the TFAP frameworkcrosses over sectoral lines, it is difficult and evenmisleading to attempt to distinguish amounts allo-cated to various sub-sectors. However, FAO's analy-sis of official development assistance in 1988 for theTFAP indicated that investment in forest industriesaccounted for the largest share (32 percent) of thetotal, followed by "forestry and land use" (23 per-cent) and "insti tutions" (20 percent) (See Table 5).Forest ecosystems conservation received less than 9

percent of the total, and to date fuelwood programshave received only half of the amount indicated inthe estimated investment requirements for the globalTFAP.27 Predictably, development banks preferredto fund industrial forestry projects, while the bilater-al aid agencies have provided the most support forland-use and institution-building projects. TheNetherlands also has pledged to substantially in-crease its assistance for forestry and for land-use andwood-energy programs.

Sketchy data indicate that national TFAPs are

15

Table 5. Distribution of Official Development Assistance by TFAP Fields of Action in 1988

Fields of Donor Countries Development Banks UN Agencies TotalAction USSmillion % US$million % US$million % US$million %

Forestry inLand Use

Forest-basedIndustries

Fuelwood andEnergy

Conservation

Institutions

150 27.4% 13-9

92.6 17 146.4

97.9 17.9 12.9

50.3 9.2 20

155.5 28.5 19.4

6.5% 50

68.9 63.8

26.6% 213-9 22.6%

33-9 302.8 32

6.1

9.4

9.1

47.2

13.2

13.8

25-1

7

7.4

158

83.5

188.7

16.7

8.8

19.9

Subtotals 631.7* 100% 212.6 100% 188 100% 1,032.3* 100%

*Includes undetermined US$85.4 million, 13.5% of total, from Federal Republic of Germany

(Source: FAO, 1989, "Review of International Cooperation in Tropical Forestry")

receiving differing levels of funding. At the high endis Nepal, which has received 65 percent of what itasked for. At the other extreme are Peru, Colombia,Panama, and Argentina, which received only a smallproportion (less than 10 percent) of the total fundingoutlined in their TFAP investment plan. Low levelsof actual funding of proposed TFAPs usually doesnot reflect a lack of donor coordination so much aspolitical factors affecting the flow of developmentassistance, or donor dissatisfaction with weakly de-veloped TFAP strategies and poorly documented na-tional plans. For such countries as Peru and Came-roon, donors also had reservations about thenational TFAP proposals for expanding industrialforestry activities.

ATTENTION TO POLICY ANDINSTITUTIONAL REFORMS

Although the FAO, national governments, andothers have emphasized the extent of funding pro-posed and mobilized through the TFAP planningprocess, institutional and policy reforms within andoutside of the forestry sector have also been a part ofthe proposed actions in national TFAPs.28 (See Table6.)

Given the composition of the sector review mis-

sions and the predominant role of the FAO ForestryDepartment and national forestry agencies in theTFAP country-level exercises, it is not surprising thatmost of the proposed reforms are related to the reor-ganization of the forestry administration. However,the revision of national forest policy, reforms in for-estry concession management systems and relatedfiscal policies,29 and improved incentives for tree-planting have also been proposed in some nationalTFAPs. The TFAP for Sierra Leone emphasizes in-stitutional reorganization and restructuring, aimed atimproving extension activities, consolidating train-ing programs, and increasing the effectiveness of theWildlife Conservation Unit. The TFAPs for Jamaica,Cameroon, and a number of other countries notedthe need to clarify conflicting mandates and to im-prove information exchange among the variousagencies involved in forest land management. TheTFAP for Papua New Guinea recommends creating anew institution to formulate and apply policy,reconcile conflicts, and administer forest resources.

A number of national TFAPs also recommendimproved institutional mechanisms for inter-sectoralcoordination and land-use planning and changes inland tenure laws. Nepal's Forestry Master Plan islinked to the country's National Conservation Strate-gy. The TFAP exercise in Colombia was reportedly"an unprecedented exercise in multisectoral plan-

16

Table 6. Proposed TFAP Institutional and Policy Reforms from Selected Countries

Within Forestry Sector Outside Forestry Sector

AFRICA

Cameroon

Ghana

Tanzania

ASIA

Papua NewGuinea

Nepal

Development of Forestry Master Plan to be incorporatedinto National Development Plan. Institutional reforms callfor creating a Ministry of Forestry, a National Wood Of-fice, Socio-economic study and Planning Unit within theForestry Administration, a national forestry school, forest-ry extension training centers, community forestry depart-ment, and strengthening of national forestry institute.Other reforms call for revision of forest industry licensingprocedures; improved incentives for planting multipur-pose tree farms; and support to local management of com-munity forest lands.

Institutional reforms include: charging the Ministry ofLands and Natural Resources to formulate a national forestpolicy; incorporation of the Forestry Commission intoMLNR. Revision of timber concessionary system to includereorganization of forest lands into concessionary units(minimum size = 10,000 ha); increasing forest revenuesfrom increased (4X) concessionary fees, and taxing of fuel-wood and charcoal; granting of tree user rights to farmersand communities; improvement of bush burning regula-tions at local level.

Reforms to the Forest Ordinance to incorporate peoplesneeds, integration of various land use activities, establish-ment of alternative institutions (e.g. village forest reserves,silvopastoral areas), and establishment of minimum stan-dards for forest management. Other recommendations in-clude: restructuring of forest administration; establish-ment of a Forest Industry Board; increased royalty fees forplantation and non-plantation wood harvesting; and stric-ter enforcement of revenue collection.

Recommendations include: need to emphasizemultiple use management of protected areaswithin context of regional development plans.

Recommendation for initiating a long termeffort to control population growth, and con-sultation with Wildlife Department in all de-velopment projects with major land useimpacts.

Recommendations include: drafting of a com-prehensive Land Tenure Act; amending theLand Ordinance to facilitate popular participa-tion and address tenure problems; energy sec-tor reforms; establishment of a Wildlife Plan-ning Unit to formulate policies andmanagement plans.

Virtually a complete overhaul of forestry policy and insti-tutions is proposed, including: development of a new For-estry Act; creation of national and regional forestry boardsas well as a new Forest Service; preparation of policystatement concerning sustained yield management; reviewof forest revenue and forest industry policies; declarationof a World Heritage Site.

Devolution of government control of forest lands, target-ing local women's groups, with increased incentives forprivate leasehold and farm forestry; reorientation of For-est Department toward advisory and extension role; liftingand relaxing of restrictions on trade, marketing, and im-ports of forest products; raising the limit on private land-holdings in forest production.

Proposes creation of a Landowner Centerdirected by a board comprising government,NGO, educational institutions and landownerrepresentation. The Center is to promote land-owner awareness, skills development, and par-ticipation in land use planning. Developmentof a national conservation strategy.

Establishment of an inter-ministry authority tocoordinate decision-making among sectorsthat utilize natural resources. Comprehensiveanalysis and reforms of land use legislation;creation of environmental legislation withinthe National Conservation Strategy. Proposesstrategy for pasture and livestock managementto integrate the National Agriculture Plan withthe Forestry Master Plan.

17

Table 6. Continued

Within Forestry Sector Outside Forestry Sector

LATIN AMERICA

Bolivia Establishment of planning bodies within regional forestrydepartments under national coordinating unit (CDF); ex-pansion and consolidation of natural areas, especially incolonization zones; creation of subsidies for rural poor tocarry out agroforestry, community forestry and non-timber (goma & castafia) extractive activities.

Colombia Reform timber concessions, permit issuance, and sawmillregulations; issue credit incentives to attract private sectorinvestment in plantation forestry; and installation of com-mercial grading and quality control for sawnwoodproduction.

Dominican Complete restructuring of government institutions andRepublic policies of the forestry sector; consolidation of public

agencies (both inside and outside the forestry sector) intoa national coordinating body. Radical reforms of nationalforestry department (DGF) responsibilities and operatingprocedures in line with "new forest policy."

Honduras Institutional reform, debt-restructuring, and budget re-allocations within national forestry agencies, with decen-tralized control; privatization of public forestry corpora-tions; classification of public forest lands into areas offorest patrimony lands (with inalienable rights), integratedmanagement units and timber concessions; devolution offorest concessionary system; establishment of contractswith local communities to develop forest resources; estab-lishment of fiscal incentives for industrial forestplantations.

Panama Regulations are proposed for laws governing the use offorest, soil conservation and water resources including:management plan requirements; extended concessionaryagreements defined by rotation length; reforestation subsi-dies; issuing public bonds for industrial expansion intoselected areas of natural forest.

Peru Decentralization of forestry department into regionalunits, supported by a central office (DGFF) with increasedpolitical status, in charge of national coordination. Pro-posed reforms of timber concessions regarding access andlength of contracts defined by rotation length to doublenational timber harvest. Expansion of national system ofConservation Units, promoting nature tourism as principaleconomic activity.

Support for land use planning in areas desig-nated for colonization schemes (by producinga national map of forest cover and land use, tobe monitored by a Geographic InformationSystem).

Proposes development of a Renewable NaturalResources Code; recommends a planning andaction program for promoting wood-basedenergy. Also, a number of measures are sug-gested for enhancing environmental educa-tion, both formal and non-formal.

Reform national income accounting to reflecteconomic growth and social welfare benefitsderived from environmental services and non-timber forest resources. Development of a na-tional watershed management plan.

Creation of "Permanent Commission for theProtection of Natural Resources and the En-vironment" among key government agencies.

Energy sector recommendations for dendro-energy (wood gasification) plants to generateelectricity in rural areas. Creation of environ-mental education program for public schoolsystem. New laws and corresponding institu-tional reforms include: a national system ofprotected areas (parks and reserves); wildliferegulations; and creation of a technical com-mission on natural resources.

National environmental education program(both formal and non-formal), focusing on ru-ral areas. In the Amazon region, the Plan callsfor: establishment of "agroforestry settle-ments" for shifting cultivators to relieve pres-sures on Amazonian forests; and petroleumsubstitution with wood energy from industrialwaste.

18

ning, successfully opening a dialogue between anumber of sectors which had not previously beenconsidered in forest resource planning."3° TheJamaica TFAP highlights the need to implement a na-tional land use strategy and to resolve land-tenureproblems. The Jamaican Plan also recommends thatenvironmental impact statements be required beforeany major changes in land use can be made. TheTanzanian TFAP was developed in part "as an instru-ment for improving inter-agency coordination andpolicy integration as well as serving to organizedonor-funded activities."31 In the Dominican Repub-lic, the TFAP planning process helped to catalyze thedevelopment of a "tree tenure" certificate to conferownership and harvesting rights to tree planters.

In the preliminary workshops and discussionswith NGOs involved in Ecuador's TFAP exercise, thelegal framework and policies that invite deforesta-tion, the influence of agricultural and energy-devel-opment policies on forests, and the need for moreattention to the needs of indigenous peoples wereraised as important issues. But these concerns arenot reflected in the official TFAP reports prepared todate. (See appendix on Ecuador TFAP.)

At least a few national TFAPs call high produc-tion goals into question. The TFAP for Papua NewGuinea recommends reducing industrial wood-production targets in view of the difficulty that theforestry administration has had managing currentlevels of logging and timber extraction. The TFAPplanning process in Zaire also raised questions aboutgovernment policy on the rapid expansion of indus-trial wood production and recommended a lowerand more realistic production target. In SierraLeone's TFAP, a relatively low level of logging by

the Forestry Industries Sierra Leone Ltd. was recom-mended until the data from a proposed forest inven-tory are available to help determine the level of asustainable annual cut; a revised and more realisticscale of timber royalties is also to be introducedthere.

kk

Clearly, a number of pre-liminary attempts havebeen made to addresspolicy and institutionalissues in national TFAPs.But a great deal of scoperemains for further analy-sis and more ambitiousproposals.

99

Clearly, a number of preliminary attempts havebeen made to address policy and institutional issuesin national TFAPs. But a great deal of scope remainsfor further analysis and more ambitious proposalsaimed at policy reforms and other actions essentialto controlling deforestation and promoting the sus-tainable development of forest land.32 More could bedone to insure that needed policy reforms are seri-ously reviewed as a part of all national TFAPs. Andthe actual enactment of such reforms needs to be en-couraged and progress in these areas closely moni-tored during the implementation of national TFAPs.

19

V. ASSESSMENT OF THE SUCCESS OF THE TFAP

These various measures and indicators of theresults of national TFAPs are revealing, but alonethey tell only part of the story. Also needed is a com-parison of the basic goals and principles of the planto its results. Ideally, such an evaluation should takeaccount of the success of both the planning processand the plan's anticipated benefits and long-termimpacts.

BASIC GOALS AND PRINCIPLES OFTHE TFAP

A number of criteria for the evaluation of theTFAP can be derived from the accumulated literatureon the plan. For example, at the May 1989 meetingof the Forestry Advisors Group, the FAO Coordinat-ing Unit for the plan presented a note on the "BasicPrinciples of the TFAP" (see Appendix 3). This notewas prepared in order to more widely publicize thegoals of the TFAP, to provide more explicit guidancefor its missions, and to suggest appropriate indica-tors for measuring the plan's results.33 FAO's notereaffirms that the plan's basic goals are to improvepeople's welfare and to conserve tropical forests.Specifically, FAO identifies the basic TFAP objectivesas "rural development (food security, alleviation ofpoverty, equity and self-reliance), and sustainabilityof development (ecological harmony, renewabilityof resources, conservation of genetic resources)." Inaddition, it has outlined ten "basic principles" that"characterize the TFAP strategy in reaching its ulti-mate objective of conservation and development oftropical forest resources."34

Unfortunately, FAO's Coordinating Unit hasn'tyet collected, analyzed, and released all the informa-tion needed to conduct such a systematic and com-prehensive review, but useful generalizations can bemade. These generalizations are grouped accordingto the suggested criteria for evaluating the TFAPplanning process, as it is still too early to judge thelong term results of the TFAP. (See Box.)

IMPROVED INFORMATION ANDANALYSIS?

Many national TFAPs do represent a step for-ward for forestry planning insofar as they direct in-creased attention to both production and conserva-

tion, and to both rural community forestry andforest industries. But the integration of the nationalTFAP into national development plans in most coun-tries is incomplete.

kk

Most national plans, basedmainly on forestry sectorreviews, simply justify in-creased investment in theforestry sector—a focustoo narrow to adequatelyassess the root causes ofdeforestation, much less toaffect them significantly.

Most national plans, based mainly on forestrysector reviews, simply justify increased investmentin the forestry sector—a focus too narrow to ade-quately assess the root causes of deforestation, muchless to affect them significantly. Many plans recycleofficial data and viewpoints on demographics,deforestation and reforestation rates, and the sus-tainability of traditional agricultural practices ratherthan correcting or questioning them.

Such critical topics as land tenure, concentra-tion of land holdings, the value of traditional uses ofthe forest and the extent of community manage-ment, and the relationship between agriculturalpractices and deforestation have not been adequate-ly reviewed in many national TFAPs. Such key con-siderations as the demographics of forest-dwellingpeople and the impact of proposed actions on in-digenous peoples have been totally neglected in vir-tually every TFAP. Moreover, the national TFAPshave not generated much new data on the availabili-ty of fuelwood or many proposals for increasing sup-ply or decreasing demand of fuelwood on a scalecommensurate with the problem.

Many national TFAPs propose substantial invest-ments in industrial wood production. In most coun-tries, more attention is accorded to forest invento-ries than to on-the-ground management, and the

21

Criteria for a SuccessfulTFAP Planning Process

Evaluation Criteria—Longer TermResults of the TFAP

Improved Information and Analysis

1. Has the TFAP produced more accurate and compre-hensive information about the extent and conditionof forest resources, the economic and environmen-tal costs of their destruction or misuse, and the link-ages between forestry and other sectors?

2. Has the TFAP provided a good analysis of existinginstitutional capabilities, including the analytical,management program implementation and trainingcapacities related to the TFAP goals?

3. Has the TFAP analysis adequately reviewed existingpolicies and programs, across a broad range of sec-tors, that influence forest land use andmanagement?

4. Has the TFAP adequately identified destructive orcounterproductive and inefficient policies, pro-grams, and investments by government, aid agen-cies or the private sector, which need to be stoppedor eliminated to protect and conserve forests?

Enhanced Participation and Political Commitment

5. Has the TFAP planning process provided for the fullparticipation of a broad range of interest groups, in-cluding major government agencies, the private sec-tor, academic and research institutions, and repre-sentatives of NGOs and local communities? And hasit given these groups easy access to alldocumentation?

6. Has the TFAP planning process led to a consensusby all interested parties on the long term strategyand immediate priority actions (including policy re-form, institutional changes, and a reallocation of in-vestment and new investment) needed to achievethe plan's goals?

7. Has the TFAP process stimulated increased politicalcommitment to address deforestation issues and awillingness to undertake the policy reforms, institu-tional changes, and mobilization of human andfinancial resources at the national level?

Greater Cooperation and Accelerated Action

8. Has the TFAP planning process helped increase in-ternational cooperation and coordinated action toaddress the problems and challenges of sustainabledevelopment and conservation of forest lands?