Landbauforschung vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Landbauforschung vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research

4,41LBF_Vol. 61 4_U4 LBF_Vol. 61 4_U1

LandbauforschungvTI Agriculture andForestry Research

Vol.61 No. 4 12.2011

Preis /Price 8 €

ISSN 0458-6859

LandbauforschungvTI Agriculture andForestry Research

Vol.61 No. 4 12.2011

4,41LBF_Vol. 61 4_U2 LBF_Vol. 61 4_U3

Gutachtergremium Editorial Board

PD Dr. Martin Banse, Institut für Marktanalyse und Agrarhandelspolitik, vTIDr. Jürgen Bender, Institut für Biodiversität, vTIDr. Jutta Berk, Institut für Tierschutz und Tierhaltung, FLIDr. Herwart Böhm, Institut für Ökologischen Landbau, vTIProf. Dr. Andreas Bolte, Institut für Waldökologie und Waldinventuren, vTIDr. Ulrich Dämmgen, Institut für Agrarrelevante Klimaforschung, vTIPD Dr. Sven Dänicke, Institut für Tierernährung, FLIDr. habil. Bernd Degen, Institut für Forstgenetik, vTIPD Dr. Matthias Dieter, Institut für Ökonomie der Forst und Holzwirtschaft, vTIPD Dr. habil. Bettina EichlerLöbermann, Universität RostockDr. Peter Elsasser, Institut für Ökonomie der Forst und Holzwirtschaft, vTIProf. Dr. Andreas Fangmeier, Universität HohenheimPD Dr. Matthias Fladung, Institut für Forstgenetik, vTIProf. Dr. Heinz Flessa, Institut für Agrarrelevante Klimaforschung, vTIProf. Dr. Ulrike GrabskiKieron, Universität MünsterProf. Dr. JörgMichael Greef, Institut für Pflanzenbau und Bodenkunde, JKIProf. Dr. Konrad Hagedorn, HumboldtUniversität BerlinPD Dr. Ingrid Halle, Institut für Tierernährung, FLIDr. Silvia Haneklaus, Institut für Pflanzenbau und Bodenkunde, JKIProf. Dr. Eberhard Hartung, Universität KielProf. Dr. Roland Herrmann, Universität GießenProf. Dr. habil. Pierre Ibisch, Hochschule für nachhaltige Entwicklung, HNEEDipl. Ing.Agr. Robert Kaufmann, Forschungsanstalt Agroscope ReckenholzTänikon ART, SchweizDr. Jörg Kleinschmit, Nordwestdeutsche Forstliche VersuchsanstaltProf. Dr. Luit de Kok, Universität Groningen, NiederlandeProf. Dr. Uwe LataczLohmann, Universität KielDr. Oliver von Ledebur, Institut für Marktanalyse und Agrarhandelspolitik, vTIProf. Dr. Bernd Linke, Institut für Agrartechnik Bornim e.V.Dipl. Met. FranzJosef Löpmeier, Agrarmeteorologische Forschung des Deutschen WetterdienstesProf. Dr. Udo Mantau, Universität HamburgProf. Dr. Axel Munack, Institut für Agrartechnologie und Biosystemtechnik, vTIDr. Hiltrud Nieberg, Institut für Betriebswirtschaft, vTIDr. Rainer Oppermann, Institut für Ökologischen Landbau, vTIProf. Dr. Herbert Oberbeck, TU BraunschweigDr. Jürgen Puls, Institut für Holztechnologie und Holzbiologie, vTIProf. Dr. Gerold Rahmann, Institut für Ökologischen Landbau, vTIProf. Dr. Detlef Rath, Institut für Nutztiergenetik, FLIDr. Thomas Schneider, Institut für Weltforstwirtschaft, vTIProf. Dr. Dr. habil. Dr. h.c. Ewald Schnug, Institut für Pflanzenbau und Bodenkunde, JKIDr. Lars Schrader, Institut für Tierschutz und Tierhaltung, FLIProf. Dr. Andreas Susenbeth, Universität KielProf. Dr. Friedhelm Taube, Universität KielProf. Dr. KlausDieter Vorlop, Institut für Agrartechnologie und Biosystemtechnik, vTIProf. Dr. Dr. habil. Drs. h.c. Gerd Wegener, TU MünchenProf. Dr. HansJoachim Weigel, Institut für Biodiversität, vTIProf. Dr. Peter Weingarten, Institut für Ländliche Räume, vTIDr. Nicole Wellbrock, Institut für Waldökologie und Waldinventuren, vTI

Landbauforschung

Landbauforschung (vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research) ist ein wissenschaftliches Publikations organ des Johann Heinrich von ThünenInstituts (vTI), Bundesforschungsinstitut für Ländliche Räume, Wald und Fischerei. Die Zeitschrift wird vom vTI heraus gegeben und erscheint vierteljährlich. Die Sprache der Beiträge ist deutsch und englisch. Sonderhefte erscheinen nach Bedarf.

In der Zeitschrift werden Forschungsergebnisse aus der Ressortforschung des BMELV mit Bezug zur Land und Forstwirtschaft und den ländlichen Räumen veröffentlicht, einschließlich Forschungs ergebnissen aus Kooperationsprojekten, an denen das vTI beteiligt ist.

Die Landbauforschung ist eine multidisziplinär ausgerichtete Zeitschrift, die die verschiedenen Facetten der Agrar und Forstwissenschaften einschließt und besonderes Augenmerk auf deren interdisziplinäre Verknüpfung legt.

Englischsprachige Beiträge sind erwünscht, damit die Forschungsergebnisse einem möglichst breiten wissenschaftlichen Diskurs zugeführt werden können.

Für den Inhalt der Beiträge sind die Autoren ver antwortlich. Eine Haftungsübernahme durch die Redaktion erfolgt nicht.

Mit der Einsendung von Manuskripten geben die Verfasser ihre Einwilligung zur Veröffentlichung. Die von den Autoren zu beachtenden Richtlinien zur Einreichung der Beiträge sind unter www.vti.bund.de oder bei der Geschäftsführung erhältlich. Das exklusive Urheber und Verwertungsrecht für angenommene Manuskripte liegt beim vTI. Es darf kein Teil des Inhalts ohne schriftliche Genehmigung der Geschäftsführung in irgendeiner Form vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden.

Indexiert in: CAB International, Science Citation Index Expanded, Current Contents Agriculture, Biology & Environmental Sciences

Herausgeber

Johann Heinrich von ThünenInstitut (vTI)

Gutachtergremium

Siehe 3. Umschlagseite

Schriftleitung

Prof. Dr. Folkhard Isermeyer

Geschäftsführung

Dr. Matthias Rütze Tel. 040 . 739 62 247 Leuschnerstraße 91 21031 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] www.vti.bund.de

ISSN 04586859

Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research

Landbauforschung (vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research) is a scientific journal of the Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute (vTI), Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries. The journal is published quarterly by the vTI. The articles appear in either German or English. Special issues are published as required.

The journal publishes research results under the auspices of the German Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (BMELV). Articles bear relevance to agriculture and forestry, as well as to rural areas, and include research results from cooperative projects involving the vTI.

vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research is a multidis ciplinary journal, encompassing the various facets of this field of research and placing a particular emphasis on interdisciplinary linkages.

English language contributions are desired so that the research results can achieve as broad a scientific discourse as possible.

The authors are responsible for the content of their papers. The publishers cannot assume responsibility for the accuracy of articles published.

With the submission of a manuscript, the author grants his or her permission for publication. Authors are requested to follow the guidelines for submission found at www.vti.bund.de or available from the management. The vTI retains exclusive copy and usage rights for accepted manuscripts. No portion of the content may be duplicated or distributed in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

Indexed in: CAB International, Science Citation Index Expanded, Current Contents Agriculture, Biology & Environmen

tal Sciences

Publisher Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute (vTI)

Editorial Board Directors of vTIInstitutes

Editor in Chief Prof. Dr. Folkhard Isermeyer

Managing Editor Dr. Matthias Rütze Phone + 49 40 . 739 62 247 Leuschnerstraße 91 21031 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] www.vti.bund.de

ISSN 0458 – 6859

All rights reserved.

iLandbauforschungvTI Agriculture and Forestry ResearchVol. 61 No. 4 12.2011

JochenSchmitzandOlivervonLedebur

Volatility transmission on international futures markets during the 2007/08 price surgeVolatilitätsübertragungaufinternationalenTerminmärktenwährenddes2007/08Preisschubs

273

AnjaSchwalmundHeikoGeorg

Elektronische Tierkennzeichnung – ISO-Standards und aktuelle Situation in DeutschlandElectronicanimalidentification–ISO-standardsandcurrentsituationinGermany

283

GraciaUde,HeikoGeorg,SophiaBenderundAnjaSchwalm

Eignung von Thermo-Injektaten zur elektronischen Tierkennzeichnung und Körpertemperaturerfassung bei ZiegenResearchingoatswithbio-thermo-transpondersforelectronicidentificationandbodycoretemperaturelogging

289

IngridHalle,MartinaHenning,andPeterKöhler

Influence of vitamin B12 and Cobalt on growth of broiler chickens and Pekin ducksEinflussvonVitaminB12undKobaltaufdasWachstumvonBroilerundPekingente

299

KerstinBarth,KarenAulrich,HelgeChristianeHaufe,UteMüller,DagmarSchaub,andFranzSchulz

Metabolic status in early lactating dairy cows of two breeds kept under conditions of organic farming – a case study StoffwechselstatusvonzweiRasseninderFrühlaktationunterBedingungendesökologischenLandbaus–eineFallstudie

307

ChristineBrandt,ChristianeBalko,andBettinaEichler-Löbermann

Interactive effects of soil water content and phytin supply on phosphorus nutrition of different crops species WechselseitigerEinflussvonWassergehaltdesBodensundPhytin-ZufuhraufdiePhosphor-ErnährungverschiedenerFruchtarten

317

UlrichDämmgen,WilfriedBrade,JoachimSchulz,HeinrichKleineKlausing,NicholasJ.Hutchings,Hans-DieterHaenel,

andClausRösemann

The effect of feed composition and feeding strategies on excretion rates in German pig productionDerEinflussvonFutterzusammensetzungundFütterungsstrategienaufdieAusscheidungsrateninderdeutschenSchweineproduktion

327

JörgBurgstaler,DennyWiedow,FraukeGodlinskiundNorbertKanswohl

Einsatz von Natriumhydrogencarbonat in landwirtschaftlichen BiogasanlagenApplicationofsodiumbicarbonateinagriculturalbiogasplants

343

GeerdA.Smidt,AndreaKoschinsky,LeandroMacchadodeCarvalho,JoséMonserrat,andEwaldSchnug

Heavy metal concentrations in soils in the vicinity of a fertilizer factory in Southern BrazilSchwermetallgehalteinBödenimUmfeldeinerDüngerfabrikinSüdbrasilien

353

JoachimSpilke

Information zum „Leitfaden zur Einordnung, Planung, Durchführung und Auswertung von Versuchen unter Produktionsbedingungen (On-Farm-Experimente)“

365

J. Schmitz and O. v. Ledebur / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)273-282 273

Volatility transmission on international futures markets during the 2007/08 price surge

JochenSchmitz*andOlivervonLedebur*1

*1 JohannHeinrichvonThünen-Institut(vTI),InstituteforMarketAnalysisandAgriculturalTradePolicy,Bundesallee50,38116Braunschweig,GermanyE-mail:[email protected]

Abstract

Thestudyisacontributiontothedebateonthecom-moditypricespike in2007to2008andtherelationshipamong commodity futuresmarkets. The transmissionofprice volatilitybetween futuresmarkets is analysed. Thebackgroundquestioniswhether,andtowhatextent,thevolatilityofagriculturalfuturesatdifferentmarketplaceswastransferredduringthepricechangesof2008.Thevol-atilityofmaizefuturesatdifferentexchangesismodelledasamultivariateGARCH-process.Bydoingso,interactionsbetweenmarketsindifferentvenuesareincorporated.Es-timationresultsarediscussedagainstthebackgroundofthedevelopmentsinagriculturalandbiofuelpolicy.

Keywords: commodity futures, corn, time series, price volatility transmission, multivariate GARCH.

Zusammenfassung

Volatilitätsübertragung auf internationalen Termin-märkten während des 2007/08 Preisschubs

Diese Studie liefert ein Beitrag zur Debatte über denPreisanstieg auf den Rohstoffmärkten in 2007 bis 2008sowiedemVerständnisderBeziehungenzwischenWaren-terminmärkten.DieÜbertragungvonPreisschwankungenzwischenWarenterminmärktenwirdanalysiert.DieKern-frage ist,obund inwelchemUmfang,dieVolatilitätderAgrar-Futures auf verschiedenen Marktplätzen währendderPreisänderungendesJahres2008übertragenwurde.DieVolatilitätdesMais-FuturesanverschiedenenBörsenwirdalseinmultivariaterGARCH-Prozessmodelliert.Da-durch sind die Wechselwirkungen zwischen den Märk-ten an verschiedenen Börsenplätzen aufgenommen. DieErgebnisse der Schätzungwerden vor dem HintergrundderEntwicklungenderAgrarpolitikundderBiokraftstoff-Politikdiskutiert.

Keywords: Warenterminkontrakte, Mais, Zeitreihenana-lyse, Volatilitätsübertragung, multivariates GARCH

274

1 Introduction

Inthepastcoupleofyearsmajorchangescouldbeob-servedontheagriculturalmarkets.Withinashortperiodof time, theprice levelofagricultural rawmaterials rosewithseriousconsequencesfortheentireagriculturalsec-tor.TheFAO,theEUCommission, IFPRI,theWorldBankandotherorganisationspointpricedynamicsontheagri-culturalmarketsasthedrivingcauseofincreasesofboththepricelevelandpricevolatility,(EC,2008a;EC,2008b:6ff;FoodandOrganisation,2008:55to57;Roblesetal.,2009;CaveroandGalian,2008;Rabobank,2008:8ff).

0

2000

M1

2005

M1

2001

M1

2006

M1

2002

M1

2007

M1

2003

M1

2008

M1

2004

M1

2009

M1

2000

M7

2005

M7

2001

M7

2006

M7

2002

M7

2007

M7

2003

M7

2008

M7

2004

M7

2009

M7

2005 Index

= 1

00

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

Commodity food price index

Crude oil price index

Fertilizers index

Source: Own calculations based on IMF (2009) and World Bank (2009).

Figure1:

Monthly price index for fertilizer, crude oil and food (Index2005=100,2000to2008)

50

100

150

200

250

300Corn

Soy beans

Wheat

Food price index

Beef

Pork

2005 Index

= 1

00

2000

M1

2005

M1

2001

M1

2006

M1

2002

M1

2007

M1

2003

M1

2008

M1

2004

M1

2009

M1

2000

M7

2005

M7

2001

M7

2006

M7

2002

M7

2007

M7

2003

M7

2008

M7

2004

M7

2009

M7

Source: Own calculations based on IMF (2009) and World Bank (2009).

Figure2:

Monthlypriceindexforfoodagriculturalproducts(Index2005=100,2000to2008)

Thepricechangesontheagriculturalmarketstookplaceinthecourseofageneralincreaseinrawmaterialsprices(seeFigure1andFigure2).A series of factors had an impact on the agricultural

marketsduringtheperiodofpriceincrease.Amongthese,structural changes in global demand and repeated sup-plyshortages in importantproducingregionsduringthefirstdecadeofthecentury.Thisledtocontinuousglobalstock reductionswhich supported the observed positivepricedevelopment.Otherfactorswerementionedwhichinfluenced the agricultural market volatility in the pastyears.Amongthesewerechangesinthemarketandtradepolicyinmanycountries.Thereductionofexportablesur-plusesintheEUoccurredatessentiallythesamepointintimeastheworld’smarketsupplysituationonthecerealsmarketwasmostconstrained.Throughthe implementa-tionofmeasuresthatburdenexportsatthistime,severaltraditionalgrainexportingcountriespreventedarelaxingoftheworldmarketsituation.Withthesemeasurestheyevenincreasedtheexistingscarcity,andconsequentlythesupplyinsecurity,andultimatelythemarketvolatility.Also“new”market interventions, such as the additional de-mandofagriculturalrawmaterialsforfueluseasaconse-quenceofthepromotionofbioenergyleadtoanincreaseofinsecurityrelatedtomarketsupply.Finally,theincreaseof uninformed and speculative investors on the futuresmarketsmust also bementioned.Manymarket observ-ers argued they influenced the price level and volatilityonthefuturesmarketsaswellasthephysicalmarkets.Inthelivelydebateonthistopic,neitheraconsensusontheleveloftheinfluenceofpolicyinstrumentsintheareasofrenewableenergyprovidersontheprice levelofagricul-turalmarkets,noranclearcausalinteractionbetweentheincreasedactivitiesofspeculativeinvestorsonthefuturesmarkets, have yet been found (FAO, 2007: 48; Gilbert,2009; Rabobank, 2008: 9; Tangermann, 2011; USDA,2008:20).Thispaperanalyzestheinterrelationshipoffuturesmar-

ketsofagriculturalrawmaterials. Inparticularthetrans-mission of price volatility betweenmarketswill be con-sidered.Thecornmarketwaschosenas thekeymarketfor thisanalysis.Thisproductplaysacentral roleworld-wideforthe livestockproductionbutalso intheareaofsubstitutionoffossil fuelswithbio-fuelsfromrenewableresources.Theemphasisof theapproachof substitutingfossil fuelswith renewable agricultural rawmaterials asimplementedintheUnitedStatesisbasedontheuseofethanolfromcornstarch.TheChicagofuturesmarkettakesanexposedposition

in world trade with agricultural raw materials. A largepart ofworldwide futures tradewith corn is realized attheChicagoBoardof Trade (CBOT) since theUSA is byfarthelargestcornproducerandexporteratgloballevel.

J. Schmitz and O. v. Ledebur / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)273-282 275

ContractpricesachievedattheCBOTinthecourseofthefutures tradinghaveawide reachingsignal function forglobal cornmarkets. Inaddition to this exchange, therearetwootherexchangesofinterest.ThesearetheFuturesExchangeinSãoPaulo(BolsaMercantiledeFuturos,BMF,here denominated BRAZ) in Brazil and the Paris-basedExchange, theMarche a Terme d’Instruments Financiers(MATIF).TheBrazilianagriculturalmarketsarecharacter-izedbynotable largeexport surplusgrowth rates.SincetheBrazilianmacroeconomic stabilization succeeded the1990’s,tradeattheBMFhasincreased,andcurrentlytheexchangeassumes the roleof regional referencemarketfor some commodities. The French exchange takes therole of leading market with regard to cereals marketswithintheEuropeanUnion.Inthecontextofgloballyincreasinglyinterrelatedagri-

cultural and financial markets, the question emergeswhether and towhat extent futures price volatilitywascarriedoverbetweeninternationaltradingcentresduringthedrasticpricechangesof2008.Thisquestionhasonlybeendealtwithapproximately intheagriculturalecono-mic scientific literature (Baffes, 2007; EC, 2008a; EC,2008b;GarciaandLeuthold,2004).Untilnow,studiesonthevolatilityofagriculturalmar-

ket prices have mainly concentrated methodically on aunivariate approach.At theheartof thepast analysis isamodellingofvolatilityasaGARCH(GeneralizedAuto-regressiveConditionalHeteroscedasticity) Process,whichwas supplementedwith exogenous factors. Factors thathavebeenidentifiedaregovernmentprogramsfortheUSfuturesandcashwheatmarkets(CrainandLee,1996)orinventoriesandtradingvolumefortheUScornandwheatfuturesmarkets (Goodwin and Schnepf, 2000). Regard-ingthevariabilityinfuturesmarkets,abetterunderstand-ingofthefactorsthataffectpricechangesandvolatilityisneeded(GoodwinandSchnepf,2000;Boudoukhetal.,2003).Against this methodological background, interactions

betweenfuturesmarketsatdifferenttradingcentreswereexcluded. In lightof the jointprice increaseacrosscom-moditymarkets,thequestionemergesofhowadequateanisolatedconsiderationofasinglemarketis.Forthisrea-sonwetakeadifferentapproachinthisstudy.Itappearsto be necessary to illustrate the relevantmarkets simul-taneouslyandtodocumenttheirinterdependencies.Inor-dertoachievethisfortheglobalcornmarket,weillustratethe markets in a multivariate heteroscedasticity model.ThemodellingapproachofaBEKKModel1

1 BEKKmodelsarenamedafterBaba,Engle,KraftundKroner.

isusefulforthispurpose. A positive definite covariancematrix Ht (EngleandKroner,1995)duetothemodelset-upletthismodel

appeartobesuitedforthisanalysis.Thisarticleisdividedinto the following areas. The next section introduces indetailthemethodsoftheBEKKmodel.Section3presentsthedatausedandtheestimatedresults.Adiscussionontheresultsclosesthissection.Thefinalsectionconcludeswithadiscussionofpossiblefutureresearch.

2 Model

GARCHmodelsserveasthebackboneofvolatilitymo-delling.Throughtheapproachby(Engle,1982),itispos-sibletomodelthe(unobserved)secondmoment.There-sultingvarianceisdependentontheamountofcurrentlyavailable information. ThewholeGARCHmodel can becharacterizedby4equations.Thefirstpartdescribesthemean equation and illustrates the first moment of theprocess(Equation(1)).Inthisspecificationonlyalongtermtrend component μ is assumed. Daily percentage pricechanges(Pricereturns)areusedforestimation.Thosere-turnsarebestcharacterizedbyalongtermtrendcompo-nent.Thesecondpartdescribesthevarianceequation.Itserves

asthesecondmomentoftheprocess(Equation(4)).Theknowninformationset isgeneratedfromthereturnsuptothetimepointt-1.FurthermodelcharacterizationsareneededtofullydescribetheGARCHmodel.Equation(2)servesasalinkbetweenEquation(1)andEquation(4).Itstates that the secondmoment is driven by conditionalheteroscedasticity.Equation(3)declaresthedistributionoftheinnovationoftheprocessasanormaldistribution.Thereturnsarecalculatedasrt=log(Ft/Ft−1).Thefutures

priceatthatpointintimeiscalledFt,andrtdescribestheillustratedreturnsattimepointt:

rt P �H t (1)

ttt H (2) tt �H (3)

Theresultingvarianceofrtyieldsthegeneralizationofthemodel by (Bollerslev, 1986). It permits the inclusionofpastvariancesinadditiontotheconsiderationofpastinnovations.This leads to thegeneralunivariateGARCH(p,q)model:

ttttt ��� ������ EEHDHDD � (4)

Thepastinnovations D H t� � �D H�

t� arecalledtheARCH-termswhilethepastvariances E t� � � E t� � arecalledtheGARCH-terms.ThetransferintoamultivariateGARCHmodeltakesplace

withageneralizationoftheresultingvariancematrixHt.

� �

276

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§ t (5)

EachelementofHtdependsonpdelayedvaluesofthesquared H , the cross product oft H andonq delayedtvalues of the elements from Ht. We did not make useof thepossibility todrawexogenous factors into the re-sultingvarianceequation.Ingeneral,amultivariateGARCH(1,1)modelwithoutexogenousfactorscanbepresentedasfollowsasaBEKKmodel(EngleandKroner,1995).Forreasonsofclarity time indicatorsarenot included in thepresentation.Amodelwiththetimedelayofonlyonelag(t-1)wasmodelled.

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§

�¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§

¸¸¸

¹

·

¨¨¨

©

§�

t

HHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

(6)

Throughthemodelconstructionviathequadraticformitispossibletopositivelydefinetheresultingvariance-co-variancematrixHt.Thisensuresthatallvariancesandco-variancesarealwayspositive.Incompactform,theaboveequationcanalsobewritteninthismanner:

tttt ��� �� HH (7)

Thematrices , 0and possessthedimension(n×n).

0 is a (lower) triangularmatrix. In themodel assumedhere,we are dealingwith thematrices and on di-agonalmatrices.Ageneralizationofthemodelispossible.Further interactionscouldbeimplemented,butthenthematrices and arenotdiagonalanymoreandresultsinamuchmorecomplexmatrixHt.Apartfromtheachievementofapositivedefinitematrix

Ht,thereisanotheradvantageoftheBEKKspecification.DuetothediagonalBEKKmodelassumedhere,acheckingofthestationarynatureoftheprocessisdeterminedsolelythroughthediagonalelementsofmatrices and .Thedi-agonalBEKKmodelisstationaryif ¦

� � �(EngleandKroner,1995,p.133). Inaccordancewiththequestionsstatedintheintroduction,threetradingcentres(exchanges)werestudied(n=3).Theaccordingvarianceandcovarianceequationsareasfollows:

�� H (8)

�� HH (9)

�� HH

(10)

�� H

�� H

(11)

�� HH (12)

(13)

TheindexesusedrecedetothenotationusedinEqua-tions(5)and(6).ThematrixHtcontainsredundantexpres-sions.Forthesakeofaclearandcomprehensibleanalysis,

nodistinctionismadebetween 21/ 12, 31/ 13

or 32/ 23.Sothe influencefromCommodityMarket1(inourlatermodelimplementationCBOT)onCommodityMarket2(inourlateranalysisMATIF)isthesameandviceversa.Thesameholdsforallotherpossiblemarketinter-actions. This analysis should revealwhetherthere is any relationship between marketsatthatperiodoftime. Itshouldnotanswerwhichmarket influences the othermarkets

most. The empirically estimated BEKK-GARCH model isthusbasedonamultivariateversionofEquation (1)andEquations(8)to(13)(derivedfromEquation(6)).

3 Data and results

Theinteractionsofvolatilitiesbetweenthetradedpricequotations on the commodity exchanges in the USA(CBOT), Brazil (BRAZ) and Europe/France (MATIF) werestudied.Thetopicofthisanalysisisrelatedtopricequota-tionswhichranoutinMarch2008,andwasdealtwithonallthreeexchangeswiththesamerunningtime.Exchangequotationsfrom27.March2007to5.March2008wereavailable.TheCentralMarketandPriceReportingAgency(ZentraleMarkt- und Preisberichtsstelle – ZMP) providedthedataasacourtesy.Pricequotationsaregiven inUS-Dollars.Eachfuturescontractisbasedonadifferentcornquantity. In Europe one contract stands for 50 tons ofcorn.InBrazil,450unitsof60kilogrambagsaretradedby one contract. This is equivalent to 27 tonnes. In theUnitedStates,theunitpercontractis5000bushels.Thisisequivalentto127tonnes(1bushelofcornisequalto25.4kilogram).Thisdifferentunitofmeasurementexplainstheobservedpricelevelsperunitofweightonthesemarkets.Duetoholidays,etc.,onsomedays,pricenotationswerenotavailableforallthreemarkets.Thusallexchangequo-tationsweredeletedfor thesedays.Overallat thestart,245 exchange quotationswere available. After the vali-

J. Schmitz and O. v. Ledebur / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)273-282 277

dation, 226 observations remained for the estimates. IntheframeworkofaGARCHestimate,this is justasmallsample.AttheMATIFandBRAZtradingcentres,theap-propriatefutureswerenotplacedandtradedearlier.Thus,only thementioned 245 daily notations were available.This isduetothedifferentdefinitionofthecontractsatthefutureexchanges.Thetimedevelopmentofpricesperunitofweightfor

cornbetween27.March2007and5.March2008ispre-sentedinthefollowingFigure3.Thevalueofonefuturescontractconsistsofthepriceperunitofweightmultipliedwiththecorrespondingunitoftrading.OnecanrecognizeacontinualpriceincreaseontheChicagoexchange.ThisincreasebeganinOctober2007.Acomparablystrongandpermanentpriceincreasecannotbeobservedfortheother

exchanges. Consequently, this price development alsoaffectsthereturns,thelogarithmicdifferenceofthepricelevel,oftheprocess.AccordingtoFigure3,theprocessesshowaveryclear

non-stationarybehaviour.Stationarityoftimeseriesdatacan be tested by Unit-Root tests. The validation of sta-tionarity will be conducted by the Augmented-Dickey-Fuller-Test (ADF-test). For this test the null hypothesis isnon-stationarity.Resultsaregiven inTable1.Theresultsclearlyendorsethenon-stationarybehaviouroftheseries.Sincetheestimationofthemodelusingpricelevelsisnotindicated,stationaryvariablesaretobeused.The correspondent returns are significantly stationary at

the1percentlevelandaresuitedformodelling(seeFigure4).

200

250

300

350

400

MATIF

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

BRAZ CBOT

8

10

12

14

16

18

3

US

$ p

er

bush

el

4

5

6

Source: ZMP (2009).

US

$ p

er

60 k

g

US

$ p

er

ton

Figure3:

CornpricespertoninFrance(MATIF),per60kginBrazil(BolsaMercantiledeFuturos,BRAZ)andperbushelintheUSA(CBOT)

-0.08

-0.06

-0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

MATIF

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

27.03

.07

27.04.0

7

27.05

.07

27.06.0

7

27.07

.07

27.08

.07

27.09.0

7

27.10

.07

27.11.0

7

27.12

.07

27.01.0

8

BRAZ CBOT

-0.08

-0.10

-0.06

-0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

-0.06

-0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

Source: Own calculations based on ZMP (2009).

Figure4:

CornpricesreturnsinFrance(MATIF),inBrazil(BolsaMercantiledeFuturos,BRAZ)andintheUSA(CBOT)

278

Table1:

Unit-roottestsforpricelevelandreturns

MATIF BRAZ CBOT

Future Return Future Return Future Return

Observations 224 223 224 223 224 223

ADF-Test 1.200 -12.9035 1.2520 -13.0326 1.400 -14.3167

(0.9411) (0.0000) (0.9464) (0.0000) (0.9594) (0.0000)

Prob.Valueinparenthesis(Prob.value)

Source:Owncalculations.

Table2containsasummaryofthedataforthereturnsofthecornprices.MostclearlyevidentaretheresultsoftheJarque-BerastatisticsinTable2.Accordingtothesevaluestheassumptionofnormaldistributiononthebasisof5%levelcannotbe rejectedfor theCBOTdata.Thisfindingisincontrasttothestylizedfactsoffinancemarketdata.Thismarketdatareactioncanbeinterpretedasaninflu-enceofthepoliticalinstitutionalframeworkatthatperiodoftime. Inanormalmarketsituationoneshouldexpectonepriceforoneproductondifferentmarkets(inabsenceoftransportcost,etc.).Theclassiceconomic“Lawofoneprice”principlewasnotvalidinthistimeperiod.

Table2:

Summaryofreturnsfortheselectedexchanges(27.March2007to5.March2008)

MATIF BRAZ CBOT

Mean 0.0020 0.0020 0.0014

Median 0.0026 0.0022 0.0012

Max 0.0645 0.0701 0.0457

Min -0.0657 -0.0788 -0.0537

Std.deviation 0.0167 0.0182 0.0185

Skewness -0.2844 -0.0094 -0.2595

Kurtosis 5.0355 5.4022 3.2843

Jarque-Bera 41.6920 53.8667 3.2682

Prob.value 0.0000 0.0000 0.1952

Source:Owncalculations.

Thereasonsforsuchsurprisingresultscouldhavetheirorigininthepoliticalinstitutionalframeworkconditions.Herechangesinframeworkconditionsapplyforthecornmarket,particularlyintheUSA,wherethecornethanolindustryexpansionishighlysubsidized.Themassivelyextendedproductionofethanolonthebasisofcornstarch,inducedbytheUSethanolpolicy,re-quiresaccordingamountsofrawmaterials. IntheUSA,cornandsoyproductioncompeteforland.Alreadyinthepreviousperiod(October2006toMay2007),onecouldobserveasi-multaneous price increase for both products on the futuresexchangesandalsoonthephysicalmarkets,whichwasinter-

pretedasanexpressionofdemandpressureevidentthroughthecompetitionforlandduringthesowingperiod(Theis,2007:48to49).Thetimeperiodconsideredherecomeswithafurtherincreaseinthepriceofcrudeoil,whichdrovetheethanolboomfurther.Againstthebackgroundofthispricedevelopment,thepricecompetitivenessofthebiogenicfuelasasubstituteforfos-silfuelincreased(seeFigure5).Inlightoftheexpectedfurtherdemand,increasinglyhigherpriceswereofferedforcorncon-tractsontheChicagoexchangeinordertosecurethesupplyofcornforprocessingandfeeding.

22 140

12020

100

‘00

0 b

arr

els

18

8016

60

14 US

$ b

arr

el

40

12 20

10 0J F M A M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J A S O N D

07070707 0707070707070707 08080808080808080808 0808

US ethanol production

Crude oil price (US$/barrel)

Source: Renewable Fuel Association (2009) and IMF (2009).

Figure5:

US ethanol production and crude oil price development, January2007toDecember2008.

The increase of corn price at the CBOT during the timeperiodOctober2007toMarch2008coincidesalsowithade-valuationoftheUSDollaragainsttheBrazilianReal(Figure6).Thisexchangeratedevelopmentleadstoarelativepriceadvan-tageoftheUSpricedproduct,whichfinallymayhaveledtoanincreaseinforeigndemandforUScorn.Thisappliesparticularlyagainstthebackgroundofthetensesupplysituationoffeed-ingstuffin2007/08.IntheEuropeanUnionwheathasbeensubstitutedbycornandcornhasbeenincreasinglyimported.Due togeneticallymodifiedcorn,ArgentineancorndidnotobtainaccesstotheEuropeanmarketsatthistime.ThisledtoanincreaseddemandforBraziliancorn.Accordingtoextreme-lyhighworldmarketprices,Braziliancorncouldbetransported

J. Schmitz and O. v. Ledebur / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)273-282 279

totheEUmarketwithoutanytariffburden2

2 ThecalculationoftariffratesforcornbytheEUCommissionisbasedonFOBpricesoftheUSgoodsattheGulfofMexico,transportcoststoRotterdamandtheadministratedinterventionprice(CAPMonitor,2009).This linktotheUScornmarkethasbeenliftedundertheprevalentmarketconditions

.Thesefactorsto-getherleadtoasignificantpriceincrease,seeFigure3.

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2

2.2

2.4

2.6

J

07

F

07

M

07

A

07

M

07

J

07

J

07

A

07

S

07

O

07

N

07

D

07

J

08

F

08

M

08

A

08

M

08

J

08

J

08

A

08

S

08

O

08

N

08

D

08

BRR per US$

Source: (MAPA – Ministério da Agricultura; Pecuaria e Abastecimento, 2009).

Figure6:

ExchangeratedevelopmentBrazilianRealtoUSDollar,January2007toDecember2008.

An impact of an increasing European demand on UScornprices canbe excludedbecause corn imports fromtheUSAhavenottakenplacesincetheendofthe1990s

due to consumer preferences and existing regulationsin the area of consumer protection. The EU Frameworkregulationsongeneticallymodifiedorganisms(GMOs)arecontinuallybeingexpandedandupdated.Aseriesoflegalregulation existwith the clear goal of protecting publichealthandtheenvironment.AnimportantbranchoftheEU laws on GMOs deal with the release of geneticallymodified organisms into the environment. In 2002, anauthorizationprocedurewasintroduceddealingwiththereleaseofGMOsoranytypeofproductmadefromGMOs.Theprohibition,orrather,thenon-authorizationofsomeso-calledBtCornvarietiesledtoanactualendoftheUSexportsintotheEU(Wirtschaftswoche,2005),ascanbeseeninFigure7.

0

Mio

. t

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

9000

198

1

198

2

1983

198

4

1985

198

6

198

7

1988

198

9

199

0

1991

199

2

199

3

1994

199

5

1996

199

7

199

8

1999

200

0

200

1

2002

200

3

2004

2005

200

6

Other extra-EU imports

USA

Canada

So. African Cust. Union

Serbia

Ukraine

Brazil

Argentina

EU -12

EU -10

EU -15

EU -25

Source: Own calculations based on COMTRADE (2009).

Figure7:

DevelopmentofCornImportsfromNonEC/EUMemberStatesintonnes,1981to2006

ThepoliticallyinducedmarketdevelopmentintheUSAledtoasolidifyingofexpectationsforincreasingcornpric-es,whichended,amongotherthings,infewerpricede-viations.ThismayhaveledtothefactthatforthefuturespriceattheChicagoExchange,theassumptionofnormaldistributionofreturnscouldnotberejected.Additionally, the prevailing corn price level in the ob-

servedperiodwassohighthatthevariabletariffsystem

280

oftheEUforcornwasdefactoinactive.ThissystembasesuponaseriesofpricesthatendwiththeentrypriceforimportedcornattheportofRotterdamandallowstheEu-ropeanCommissiontosetandpublishtheimporttariffintheOfficialJournaloftheEuropeanUnioninatwo-weekrhythm. Figure 8 illustrates how, due to a highmarketpricelevel,theresultingimporttariffresultsinzero.

0

€/t

50

100

150

200

250

300

01.1

0.05

01.12

.05

01.02

.06

01.0

4.06

01.0

6.06

01.08

.06

01.10

.06

01.1

2.06

01.0

2.07

01.04

.07

01.06

.07

01.0

8.07

01.10

.07

01.1

2.07

01.0

2.08

01.0

4.08

01.0

6.08

01.0

8.08

01.1

0.08

01.12

.08

01.02

.09

01.0

4.09

01.0

6.09

01.08

.09

01.10

.09

01.1

2.09

Corn Chicago

Corn - fob Gulf

Corn - cif Rotterdam

1,55*EU-intervention price

Tariff rate for corn

Source: Own calculations based on EU Commission Regulations (several issues).

Figure8:

Development of EUCorn Imports Tariff,October 2005 toOctober2009

Regarding the variance and covariance equations de-scribedinSection2,theinterdependenceofthemarketscannowbechecked.Particularlythecovarianceequationsprovideinsightintotheinteractionsofthemarkets.Fromtheestimatedparametersgiven inTable3 the followingcanbeseen:Inorder tobetter comprehend the resultsweaddress

theEquations(8), (11)and(13).Equation(8) isthevari-ance Equation for CBOT, Equation (11) for MATIF andEquation(13)forBRAZ.Parameters 11,andc01fortheCBOTMarketareallnot

statisticallysignificantatthefivepercentlevel.Thismeansthat the according variance equation is partially valid(Equation(8)).ThereturnsattheChicagoFuturesMarketwerenotmarkedbyconditionalheteroscedasticityinthetimeperiodconsidered.TheconditionalvarianceofCBOTpricesischaracterisedonlybyitsownlaggedvariance.Asparameter 11isinsignificant,informationshocksarenotaccountedfor.Thisfindingagainhighlightsthepeculiarityofthisexchangeatthistime.ThisisanimportantresultsinceEquations(9)and(10)

illustrate thespill-overeffectsof theChicagoMarketonMATIFandBrazil and theARCH-termsof this equations

describedbyparameters( 11 22)and( 11 33)arenull.Thusin the time period considered, no spill-over of price orinformation shocks fromChicago (e.g., updatedharvestforecast in theUSA) took place on the development ofprices at marketplaces MATIF and Brazil. NeverthelessCBOTisofsuchimportancethattheothermarketsconsid-eredareinfluencedviathecovarianceastheGARCH-termisdescribedbytheparameters(b11b22)and(b11b33)whicharedifferentfromzero.TheseresultsmeanthatonlythelaggedconditionalvarianceofCBOTinfluencesthecovari-ance.Thepolitically inducedmarketdevelopment in theUSAcausedapartialdecouplingof theUSmarket fromtheothermarketsanalysedhere.Duetothesignificanceof the Futuresexchange inChicago (it is theglobal keymarket),anoticeableinfluenceoftheothermarketplacescameonlyviathecovariance.

Table3:

EstimatedparametersoftheBEKKmodel

Coefficient Prob.value

µ1 0.0012 0.2850

µ2 0.0024 0.0475

µ3 0.0026 0.0210

c01 0.0026 0.6539

c02 0.0018 0.5760

c03 0.0037 0.5903

c04 0.0047 0.0093

c05 -0.0005 0.9102

c06 0.0000 1.0000

11 -0.0700 0.4179

22 0.2332 0.0002

33 0.4709 0.0000

b11 0.9855 0.0000

b22 0.9216 0.0000

b33 0.8745 0.0000

Source:owncalculations.

IncontrasttothecommodityexchangeinChicago,es-timationresultsshowthatclearinteractionsexistbetweenMATIFandBrazil.Thiscanbeseenduetothesignificantparameter values 22, 33, b22 and b33, which appear inEquation(12).Thusatleastanindirect(viathecovariance)influencecouldbeidentifiedforbothmarkets.Herebothcomponentsof thecovarianceequationare relevant. In-formation shocks that occur on one of the twomarketplaces impact the volatilityof theother. The laggedde-velopmentofthevarianceoftheothermarketalonedoesnotdetermineitsfuturedevelopment.Eachvarianceequationshowsalsothespecialsituation

during the time period studied.AGARCH (1,1) process

J. Schmitz and O. v. Ledebur / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)273-282 281

couldbeidentifiedforeachofthetradingcentresinEu-ropeandBrazil,.This isnot thecase for theUSmarket.Major cornmarkets prices arenot always tied together,northereforevolatility.Transmissionsofvolatilityimpulsesaredisruptedwith relation toCBOT.This revisionof thevolatilitymarketcharacteristicswasone intentionof thisstudy.ItwasshownthattheUScornmarketwasdecou-pledfromothercornmarkets. Internationalcorntradersthereforecannotrelyonapermanentlystablerelationshipbetweenthesemarkets.Sotheremightbetradingoppor-tunities.Also(international)hedgingofcornpositionsgetscomplicatedinsuchtimeperiods.This resultmust be seen in the context of the above-

described political framework conditions. The de factoimport ban on genetic corn into Europe, aswell as thesimultaneousethanolboom,ledtostronglychangedpricedevelopmentoffuturesattheChicagoFuturesExchange.ThisresultedinadecouplingofthepricedevelopmentandvolatilitytransmissionatthecommodityexchangesinEu-ropeandBrazil.Thisdecouplingwasultimatelymeasuredandconfirmedbythemodel.Thedrivingfactorsbehindthiscannotbeanalysedwiththismethodologyapproach.NoclearidentificationbetweentheGMObanandtheUSbiofuelpoliticscanbesetas themain factor.Themajorobstacleinresolvingthisliesinthedifferenttimefrequen-cyofavailabledata.Thisstudywascarriedoutwithdailydata.DecisionsregardingGMObanorbiofuelpoliticsaremadeonayearlyorlessfrequentbasis.Adding(daily)ex-planatorydata,basedonlowfrequentdecisions,inmod-elsfordailyvolatilityisanunresolvedtask.

4 Perspectives

Themultivariate analysis framework used here contrib-utestoabetterunderstandingofpricevolatilityonthefu-turesexchangesasaninteractionofmanymutuallyaffectedtradingcentres.Itcouldsuccessfullybeshownthatthevola-tilityoffuturespricesatdifferentmarketplacesdoimpacteachother.Inparticulartheanalysisresultsshowthatinter-actionsexistedamongfuturesmarketsfortheconsideredtimeperiod.Price formation (price levelandvolatility)areinterrelatedatdifferentcommodityexchanges.Thisspecificanalysisshowedthatthelinkageamongexchangesatdif-ferentmarketplacesmightbeaffectedbypoliciesasinthecaseofthesupportforcornethanolintheUSAduringtheobservedperiod.Henceanadditionalbuildingblockintheexplanationofthevolatilitycouldbeidentified.Theinter-marketrelationshipsshouldnotbedisregard-

ed.Thosevolatilityspill-overeffectsplayasignificantroleinexplainingvolatilitypatternsondifferentmarkets.ThisworkextendedtheexistingresearchofCrainand

Lee,1996;GoodwinandSchnepf,2000;Boudoukhetal.,2003,throughamultivariateanalysis.

Nevertheless, not all aspects of the determinants ofpricevolatilityareclearandfullyidentified.Futureresearchshouldalsoanalysewhetherornottheinteractionsidenti-fiedherearetimeindependent,andifnot,whichfactorsof influenceplay a role. Thisholds inparticular true fortheanalysisofthemarketsduringandaftertheturnsinthecrudeproductsmarketsasaconsequenceofglobalfi-nancemarketcrises.Anothertopicistheexpansionofthecurrent analytical framework to identify interactions be-tweenpriceformationofagriculturalandnon-agriculturalrawproducts.

References

BaffesJ(2007)Oilspillsonothercommodities.ResourPolicy32(3):91-148BollerslevT(1986)Generalizedautoregressiveconditionalheteroscedasticity.J

Econometrics31:307-327BoudoukhJ,RichardsonM,ShenY,WhitelawRF(2003)Doassetpricesreflect

fundamentals?FreshlysqueezedevidencefromtheOJmarket.NBERWor-kingPaper9515

CAPMonitor(2009)Cereals.TunbridgeWells:AgraInformaCaveroT,GalianC(2008)Double-edgedprices: lessonsfromthefoodprice

crisis;10actionsdevelopingcountriesshouldtake.Oxford:OxfamIntera-tional,46p,OxfamBriefingPaper

Crain SJ, Lee JH (1996) Volatility inwheat spot and futuresmarkets, 1950-1993: government farm programs, seasonality, and causality. J Finance51:325-343

EngleR(1982)AutoregressiveconditionalheteroscedasticitywithestimatesofthevarianceofUKinflation.Econometrica50:987-1008

EngleR,KronerK(1995)MultivariatesimultaneousgeneralizedARCH.EconomTheory11:122-150

EC (several issues)Commission regulationfixing the importduties in thece-reals sector [online]. To be found at <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/JOIndex.do?ihmlang=en>[quoted14.11.2011]

EC(2008a)Highpricesonagriculturalcommoditymarkets:situationandpro-spects;areviewofcausesofhighpricesandoutlookforworldagriculturalmarkets[online].Tobefoundat<http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/analysis/tradepol/worldmarkets/high_prices_en.pdf>[quoted11.11.2011]

EC(2008b)NovemberupdateonrecentagriculturalcommodityandfoodpricedevelopmentsintheEU[online].Tobefoundat<http://ec.europa.eu/agri-culture/analysis/markets/food11_2008_en.pdf>[quoted23.11.2011]

FAO (2008) Food outlook : global market analysis ; may issue [online]. Tobe found at <http://www.fao.org/giews/english/fo/index.htm> [quoted10.11.2011]

FAO (2008b) Crop prospects and food situation ; july issue [online]. To befound at <http://www.fao.org/giews/english/cpfs/index.htm> [quoted10.11.2011]

FAO (2007) Foodoutlook :november issue [online]. Tobe foundat<http://www.fao.org/giews/english/fo/index.htm>[quoted10.11.2011]

GarciaP,LeutholdRM(2004)Aselectedreviewofagriculturalcommodityfu-turesandoptionsmarkets.EurRevAgricEcon31(3):235-272

GilbertCL (2010)Speculative influencesoncommodity futuresprices2006–2008.Geneva:UNCTAD,33p,UNCTADdiscusspap197

GoodwinBK,SchnepfR(2000)Determinantsofendogenouspriceriskincornandwheatfuturesmarkets.JFuturesMarkets20:753-774

IMF(2009)Primarycommodityprices[online].Tobefoundat<http://www.imf.org/external/np/res/commod/index.aspx>[quoted11.11.2011]

MinistériodaAgricultura,PecuariaeAbastecimento(2009)Estatisticas[online].Tobefoundat<http://www.agricultura.gov.br/portal/page/portal/Internet-MAPA/pagina-inicial/vegetal/estatisticas>[quoted23.11.2011]

282

RABOBANK (2008) Down to earth : finding new balances in agriculturalcommodity markets [online]. To be found at <http://overons.rabobank.com/content/images/Visieop2009-THEMA_tcm64-79411.pdf> [quoted11.11.2011]

RenewableFuelsAssociation(2009)MonthlyU.S.fuelethanolproduction/de-mand[online].Tobefoundat<http://www.ethanolrfa.org/pages/statistics>[quoted11.11.2011]

RoblesM,ToreroM,vonBraunJ(2009)Whenspeculationmatters.Washing-ton:IFPRI,IFPRIIssueBriefs57

TangermannS(2011)Policysolutionstoagriculturalmarketvolatility:asyn-thesis[online].Tobefoundat<http://ictsd.org/downloads/2011/06/tanger-mann-price-volatility-and-policy-options.pdf>[quoted14.11.2011]

TheisR(2007)StehteineneueKursrallyebevor?DLG-Mitteilungen11:48-49USDA (2008) Global agricultural supply and demand : factors contributing

totherecent increase in foodcommodityprices [online].Tobefoundat<http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/WRS0801/>[quoted14.11.2011]

WorldBank(2009)Commoditymarketsreview.Tobefoundat<http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/EXTDECPROSPECTS/0,,contentMDK:21574907~menuPK:7859231~pagePK:64165401~piPK:64165026~theSitePK:476883,00.htm>[quoted14.11.2011]

Wirtschaftswoche (2005) EU-Auflagen stoppen Import von US-Futtermitteln[online].Tobefoundat<http://www.wiwo.de/politik/eu-auflagen-stoppen-import-von-us-futtermitteln-97822/>[quoted14.11.2011]

A. Schwalm und H. Georg / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)283-288 283

Elektronische Tierkennzeichnung – ISO-Standards und aktuelle Situation in Deutschland

AnjaSchwalm*undHeikoGeorg*

* JohannHeinrichvonThünen-Institut(vTI), InstitutfürÖkologischenLand-bau,Trenthorst32,23847Westerau,E-mail:[email protected]

Zusammenfassung

DieelektronischeTierkennzeichnunghatindenletztenJahrenweiterdeutlichanBedeutunggewonnen.SiewirdinzwischenweltweitbeivielenverschiedenenTierartenso-wohlimNutztieralsauchimHeim-undHobbytierbereicheingesetzt.AuchwerdeninimmermehrLändernweltweitobligate

elektronische Tierkennzeichnungen bei einzelnen Tierar-teneingeführt,umdieVorteiledieserArtderKennzeich-nungnutzenzukönnen.BeiRindernsinddiesz.B.Kana-da,Australien,Uruguay,BotswanaundDänemark.Schafe,ZiegenundEquidenmüssenz.B. inderEUelektronischgekennzeichnetsein.AuchimHeimtiersektorsindteilwei-seelektronischeKennzeichnungenPflicht.Hundemüssenab2012z.B.beiGrenzübertritteninderEUelektronischgekennzeichnet sein. In Österreich, der Schweiz und ineinigendeutschenBundesländernbestehteinegenerelleChippflichtfürHunde.Um im Rahmen des globalen Handels eine optimale

NutzungdieserArtderKennzeichnunggewährleistenzukönnen,istesessentiell,internationaleStandardsdiesbe-züglichzuentwickeln.Die InternationalOrganizationforStandardization (ISO) ist die Internationale OrganisationfürNormung.Sieentwickeltundveröffentlichtinternatio-naleStandardsauchimZusammenhangmitelektronischerTierkennzeichnung.DieserArtikelgibteineÜbersichtüberISO-StandardsimZusammenhangmitderelektronischenKennzeichnung von Tieren, gegliedert in die AbschnitteNormung zur Tiererkennung, Standards zu AdvancedTranspondernundNormungimZusammenhangmitTest-verfahren für die elektronsiche Tierkennzeichnung. Zu-gleichwirdeinÜberblicküberdie aktuelle SituationderISO-konformenTierkennzeichnunginDeutschlanddarge-stellt.

Schlüsselwörter: Elektronische Tierkennzeichnung, ISO-Standards, Deutschland

Abstract

Electronic animal identification – ISO-standards and current situation in Germany

Theelectronicidentificationofanimals(eID)hasgainedinimportanceoverthelastyears.Itisusedworldwideinawiderangeofspeciesincludingproductivelifestock,pets,zooanimals,endangeredspeciesandwildlife.Itisbecom-ingincreasinglyimportantasanobligatoryofficialanimalidentificationinmoreandmorecountriesbecauseoftheassociatedbenefitsresultingofthisformofanimalidenti-fication.IncattleeIDisobligatoryforexampleinCanada,Australia,Uruguay,BotswanaandDenmark.Sheep,goatsandequinehavetobeelectronicallyidentifiedindieEU.There are obligatory eIDs also in the pet sector. For ex-amplepetshavetobechippedwhentheytravelintheEU(starting2012). InAustria,Switzerlandandinsomefed-eralstatesofGermanychippingisobligatoryforalldogs.In the light of global trade it is necessary to optimize

theuseofeIDworldwide;therefore,itisessentialtohaveinternationalstandardsconcerningeIDofanimals.ISO(In-ternational Organization for Standardization) is a globalnetwork thatdevelopsandpublishes International Stan-dards.Thisarticlegivesa summaryof the statusquo in ISO-

standards concerning electronic animal identification(standardsforanimalRFID,standardsforadvancedanimalRFID,testproceduresforanimalRFID).RFIDisanacronymforradiofrequencyidentification.AdditionallyanoverviewofthecurrentsituationofelectronicanimalidentificationinGermanyisprovided.

Keywords: electronic animal identification, ISO-standards, Germany

284

Einleitung

Nachdem im IDEA-Projekt (IDEA-Studie, 2001) dieDurchführbarkeit der elektronischenKennzeichnung vonWiederkäuernbestätigtwurde, istdieelektronischeTier-kennzeichnung(eTK)indenletztenJahrenzueineminte-gralenBestandteilderKennzeichnungvonTierengewor-den.SiefindetsowohlimNutztiersektor(insbesonderebeiPferd,Schaf,ZiegeundRind)alsauch imHeimtiersektor(Hund,Katze,Frettchen)Anwendung.Immermehr Länder weltweit führen obligate elektro-

nische Tierkennzeichnungen für einzelne Tierarten ein,um die Vorteile der elektronischen Form der Tierkenn-zeichnungnutzenzukönnen.InvielenweiterenLändernistzumindesteinefreiwilligeelektronischeTierkennzeich-nungmöglich.Eine obligate elektronische Kennzeichnung nach ISO

11784und ISO11785vonRinderngibteszurzeitunteranderem inKanada,Australien,Uruguay,BotswanaundDänemark.SehrvieleLänderunterstützenzumindesteinefreiwillige eTK bei Rindern u.a. Argentinien, EU, Japan,Südkorea, Brasilien, Mexiko, Neuseeland, USA (Greene,2010;CanadianCattleIdentificationAgency,2011;FCEC,2009,EuropäischenUnion,2011;Hansen,2010).DieEuropäischenKommissionprüftzurZeitdieEinfüh-

rung einer offiziellen elektronischenKennzeichnung vonRinderninEuropa(EuropäischenUnion,2011).InderEUistdieeTKvonSchaf,ZiegeundPferdPflicht

(VO(EG)21/2004;VO(EG)504/2008)undauchHunde,Katzen und Frettchenmüssen ab 2011 elektronisch ge-kennzeichnet sein, wenn sie innerhalb der EU verreisen(VO(EG)998/2003). InsbesonderefürHundefordernin-zwischenvieleLänderweltweiteineelektronischeKenn-zeichnungbeiderEinreise(z.B.Japan,Australien,Singa-pur,Neuseeland,etc.)(Agri-Food&VeterinaryAuthorityofSingapore,2011;AnimalQuarantineServiceJapan,2011;Australian Government – Australian Quarantine and In-spectionService,2011;ENZ,2011).

Normung

Der Welthandel mit Tieren und tierischen Produktenspielt eine immer größere Rolle in der Weltwirtschaft.AuchderHandelmitlebendenTierenisthierbeinichtzuvernachlässigen.ImJahr2010wurdenzumBeispielaus33Ländern lebende TierenachDeutschland importiert undin59Länderexportiert(StatistischesBundesamtDeutsch-land–Destatis,2011).EineNormungderelektronischenTierkennzeichnung ist somit international zwingend er-forderlich, um ein sicheres Auslesen der Daten an allenBedarfsstellenzugewährleisten,insbesondereimHinblickaufeineRückverfolgbarkeit imSinnederTierseuchenbe-kämpfungundderöffentlichenGesundheit.

EinefehlendeNormungkannauchbeiHeimtierenun-ter Umständen zu schwerwiegenden Folgen führen, dadieErkennungder tierindividuellenNummernicht sichergegeben ist. IndenUSAwurdez.B.einHund ineinemTierheim eingeschläfert, da der implantierte Mikrochip(ISOkonform)mitdenverwendetenLesegerätendesTier-heimesnichtablesbarwar(Nolen,2004).DieISO(InternationalOrganizationforStandardization)

istdieInternationaleOrganisationfürNormung.Sieent-wickeltundveröffentlichtinternationaleStandardsundisteinNetzwerknationalerStandardorganisationenaus161LändernmiteinerZentraleinGenf.JedesMitgliedvertrittein Land,wobeidasDeutsche Institut fürNormunge.V.(DIN)fürDeutschlandMitgliedderISOist.DieISOistkeineRegierungsorganisation. Eine ISO-Norm ist grundsätzlichfreiwilligundkeinGesetz,kannaber vonder jeweiligenRegierungzueinemerklärtwerden(ISO,2011).

ISO – Standards im Zusammenhang mit Tierkenn-zeichnung

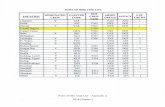

Es gibt mittlerweile einige ISO-Standards, die im Zu-sammenhangmit der elektronischen Tierkennzeichnungzu nennen sind. Ein Überblick der Standards ist in Ta-belle 1dargestellt. Bei einigender Standardswurden inden letzten JahrenÄnderungen eingefügt, bzw. kameszurEntwicklungneuerStandards. Einigewurdenwiederverworfenundanderewiederumbefinden sichnoch imEntwurf-Stadium (Tabelle 1). Daraus lässt sich ableiten,dass die elektronische Tierkennzeichnung auch auf ISO-Standard-EbeneeinensehraktuellenPlatzeinnimmtundauchhierdieaktuellenEntwicklungen/Veränderungen/Be-dürfnissemiteinbezogenwerden.DieISO-StandardszurTieridentifikation(ISO11784,ISO

11785, ISO14223-1..3)erlaubeneinenweltweitenHan-delmitTierenundermöglichendenAustauschvonInfor-mationenimSinnederTierkennzeichnung.Die Standards gelten für alle Tierarten, nicht nur für

Nutztiere sondern auch für Heimtiere, Zootiere, gefähr-deteSpezies,WildtiereundFische(FECE,2009).

A. Schwalm und H. Georg / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)283-288 285

Tabelle1:

Übersicht der ISO-Standards im Zusammenhangmit elektronischerTierkennzeichnung(www.iso.org)

ISO–Standard/Amendment Ausgabe-datum

ISO 11784:1996 1996-08

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Codestructure

ISO11784:1996AMD1:2004 2004-11

ISO11784:1996AMD2:2010 2010-06

ISO 3166-1 2006-11

Codesfortherepresentationofnamesofcountriesandtheirsubdivisions–Part1:Countrycodes

ISO3166-1:2006/Cor1:2007 2007-07

ISO 11785 1996-10

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Technicalconcept

ISO11785:1996TechnicalCorrigendum1 2008-12

ISO/IEC 14223-1 2011-03

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Advancedtrans-pondersPart1:Airinterface

ISO/IEC 14223-2 2010-08

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Advancedtrans-pondersPart2:Codeandcommandstructure

ISO/IEC 14223-3 Deleted2011-03

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Advancedtrans-pondersPart3:Applications

Norm ISO 24631-1 2009-09

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Teil1:BeurteilungderÜbereinstimmungderRFID-TranspondermitISO11784undISO11785(einschließlichderGewährungundAnwendungeinesHersteller-Codes).

Norm ISO 24631-2 2009-09

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Teil2:Beurtei-lungderÜbereinstimmungderRFID-Sender/EmpfängermitISO11784undISO11785.

Norm ISO 24631-3 2009-09

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Teil3:Beurtei-lungderLeistungderRFID-TranspondernachISO11784undISO11785

Norm ISO 24631-4 2009-09

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Teil4:Beurtei-lungderLeistungderRFID-Sender/EmpfängernachISO11784undISO11785.

ISO/WD 24631-5(underdevelopment) --

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–RFIDtrans-ceivers–Part5:ProcedurefortestingthecapabilityofreadingISO11784andISO11785transponders

Norm-EntwurfISO/DIS 24631-6 2010-04

Radiofrequencyidentificationofanimals–Part6:Represen-tationofanimalidentificationinformation(visualdisplay/datatransfer)

Standards zur RFID von Tieren

DieStrukturdesRFID-DatenwortesfürTierewirdimISO-Standard17784spezifiziert(sieheTabelle2).Durch den hier erwähnten ISO-Standard 3166-1 wird

jedem Land unter anderem ein dreistelliger Zifferncodezugeteilt(000-899).FürDeutschlandistdasz.B.dieZah-lenkombination276.Die Vergabe der Transpondernummern mit Länder-

codenach ISO3166unddieGewährleistungvonderenEinzigartigkeit liegen in nationaler Verantwortung. Gibtes in einem Land keine nationale zentrale Vergabe derNummern,solltestattdesseneinHerstellercode(900-998)verwendet werden (ICAR, 2011a). Diese Herstellercodeswerden nach ISO 24631-1 von der ICAR (InternationalCommittee for Animal Recording) vergeben. Eine Listeder aktuell vergebenen Herstellercodes ist auf ICAR.orgeinsehbar(ICAR,2011b).DieHerstellerunterzeichnenei-nenCodeofconduct,indemsiesichverpflichtengewisseVorgabenzurNutzungeinesHerstellercodeseinzuhalten(ICAR,2011a).

Tabelle2:

RFID-DatenwortfürTierenachISO11784

Bit-Nr. AnzahlZiffern

Information Beschreibung

1 1Flaganimal/nonanimalapplication

„1“fürTiere

2-4 1 RetaggingcounterNachkennzeichnung„0-7“

5-9 2 UserInformationfieldz.B.„04“SchafundZiege

10-14 2 reservedleerfürzukünftigeVerwendung

15 1Flagindicatingadvancedtrans-ponder

„1“advancedtrans-ponder

16 1 Flagindicatingdatablock „1“Datensatz

17-26 4ISO3166-1numericcountrycode

„0+Ländercode“

27-64 12 NationalerIdentifikationscode

DerISO-Standard11785spezifiziertdieAktivierungunddenDatentransferderÜbertragung.ErdefiniertdieÜber-tragungsverfahren für die Transponderdaten (HDX, FDX)undbeschreibtdieAnforderungenanLesegerätezurAkti-vierungdesTransponders(z.B.Arbeitsfrequenz(134±1,8kHz), Aktivierungsfeld, Verfahren zur SynchronisationmehrererLesegeräteetc.).

286

Standards zu Advanced Transpondern

DerISO-Standard14223isteinedirekteErweiterungzudenISO-Standards11784und11785.WährendTranspon-dernach ISO11785 lediglicheinenfestprogrammiertenIdentifikationscodeausgeben,bestehtbeidenAdvancedTranspondern dieMöglichkeit, einen größeren Speicher-bereich zu verwalten.Dieser kanngelesen,geschrieben,gegen erneutes Überschreiben geschützt ((lockmemoryblock)oderdurcheinPasswortgeblocktwerden(Finken-zeller,2008;FCEC,2009)DerAdvancedTransponder istvollabwärtskompatibelzu ISO11784/85.Diesbedeutet,dass sowohl die Identifikationsnummer eines jeden Ad-vancedTranspondersvoneinemeinfachenISO11785Le-segerätausgelesenwerdenkann,alsauch,dassISO11785Transponder von jedem Advanced Lesegerät akzeptiertwerden(Finkenzeller,2008).BeimAdvancedTransponderistbit15des ISO11784Datenrahmensauf„1“gesetzt(sieheauchTab.2)umihnalsAdvancedTransponderzukennzeichnen. Bit 16 des Datenrahmens (ISO 1175) istebenso auf „1“ gesetzt und zeigt an, dass zusätzlicheDatenvorhandensind (sieheauchTab.2).BefindensichmehrereAdvancedTransponder imAnsprechbereichdesReaderswirdeineAntikollisionsprozedurgestartet.DieserAntikollisionsmechanismus benötigt Zeit, so dass dieseMethodebeidynamischenLeseprozessen(z.B.eineGrup-pesichschnellbewegenderkleinerTiere)eventuellnichtsoeinsatzfähigist(FCEC,2009).Zurzeit ist der Advanced Transponder kommerziell für

dieTierkennzeichnungnochnichterhältlich.EinemöglicheVerwendungdesDatenspeicherswärez.B.dieSpeiche-rungvonBehandlungsdaten.Dies ist insbesonderebeimPferd interessant, da hier z. B. eine Verwendung als le-bensmittellieferndesTierausgeschlossenwerdenkönnte.

Standards zu Testverfahren von RFID

EssindverschiedeneRFIDProdukteaufdemMarkt.FürdenNutzeristesschwierigherauszufindenwelchesRFIDseinen Bedürfnissen am Besten entspricht. Aus diesemGrundwurdenStandardsentwickelt,mitdenenRFIDge-testetwerdenkönnen(ISO24631-1…4,sieheTabelle1).Zwei verschiedene Gruppen von Testprozeduren sind

verfügbar:- TestszurÜbereinstimmungmitISO11784und11785vonTranspondernundLesegeräten,inklusivederVer-gabederHerstellercodes(sieheoben).

- Tests zur Leistungder zu ISO11784und ISO11785konformenProdukte

DieRFID-DatenkönneninverschiedenenFormatendar-gestelltwerden.Dies kannunterUmständen zu Fehlernbei der InterpretationderNummern führen.Daherwird

zurzeiteinISO-StandardfürdieDarstellungderTieridenti-fikationsinformationentwickelt(ISO24631-6,sieheTabel-le1)(FECE,2009).ISO entwickelt internationale Standards, führt jedoch

selbst keine Tests zur Übereinstimmung mit den ISO-Standards durch. Um eine effektive Nutzung der Stan-dardszugewährleistenbestimmtdieISOeinekompetenteStelle,diebeiBedarfdieseAufgabenübernimmt.ImFallder Standards, die die Tierkennzeichnung betreffen, istdies das International Committee on Animal Recording(ICAR).Die ICAR istunteranderemdafür verantwortlichTestergebnisseaufihrerWebsitezuveröffentlichen(ICAR,2011c;FECE,2009).

ISO-konforme Tierkennzeichnung in Deutschland

Für die „offizielle“ elektronische Kennzeichnung (VO(EG) Nr. 504/2008; VO (EG) Nr. 933/2008; VO (EG) Nr.21/2004)stehenjenachTierartalsTransponderartendieelektronische Ohrmarke mit integriertem Transponder,derBolus,derimVormagenvonWiederkäuernverbleibt,das Injektat, das subkutan oder intramuskulär injiziertwird, und ein elektronisches Fesselband zur Verfügung(Schwalmetal.,2009).

Schaf/Ziege

Die EG-Verordnungen (EG) Nr. 21/2004, VO (EG) Nr.759/2009undVO(EU)Nr.506/2010wurdenmitderVieh-verkehrsverordnung (ViehVerkV) vom 03. März 2010 innationalesRechtumgesetzt.DanachsindSchafeundZie-geninderEUundsomitauchinDeutschlandelektronischzukennzeichnen.EsbesteheneinigeAusnahmenvonderelektronischenKennzeichnungspflichtz.B.beidensoge-nanntenSchlachtlämmern.InDeutschlandliegtdieDurch-führungderVerordnungunddieVergabederNummernbeidenjeweiligenBundesländern.Darausergibtsichauchdie Situation, dass je nach Bundesland unterschiedlicheOhrmarkenvariantenzuerhaltensindund innureinigenBundesländern auch ein Bolus zur elektronischen Kenn-zeichnungvonSchafenundZiegen zurVerfügung steht(Schwalmetal.,2010a).

Rind

InDeutschland istnachderVVVOdieKennzeichnungmit zwei Sicht-Ohrmarken verpflichtend (Grundlage: VO(EG) Nr. 1760/2000). Nach der Viehverkehrsverordnungvom03.März2010kanneinedieserOhrmarkenelektro-nischausgeführtsein(mitGenehmigung),d.h.esbestehteinezunächstfreiwilligeEinführungdereTK.DieEinfüh-rungdereTKobliegtauchhierdeneinzelnenBundeslän-dern.

A. Schwalm und H. Georg / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)283-288 287

EineobligateelektronischeKennzeichnungvonRindernistineinigenLändernbereitsimEinsatz(z.B.Kanada,Aus-tralien,Uruguay,Dänemarks.o.).AuchinderEUwirddieEinführung einer elektronischenKennzeichnungbei Rin-derngeprüft(EuropäischenUnion,2011a–Tieridentifika-tion–bovine).

Hund/Katze

EinelektronischesKennzeichen(Transponder)istalsKenn-zeichnungbeiHeimtieren(Hund,Katze,Frettchen)zugelas-senundwirdab2012obligatorischbeiReiseninnerhalbderEUgefordert(VO(EG)Nr.998/2003).EsgibtinDeutschlandkeine generelle Pflicht zur elektronischen KennzeichnungvonHunden.Esgibt jedoch in jedemBundeslandgeson-derte„Hundeverordnungen“,dadieGefahrenabwehrbeiden Ländern liegt.Dabei ergeben sichmitunter sehr ver-schiedeneVorschriftenundRegelungenauchimBezugaufdie Kennzeichnungspflicht bei Hunden (Schwalm et al.,2010b).SosindineinigenBundesländernalleHundeelek-tronischzukennzeichnen(z.B.Sachsen-Anhalt),ineinigennurbestimmteHunde(z.B.Schleswig-Holstein)undineini-genisteineelektronischeKennzeichnungnurauffreiwilli-gerBasiseingeführt(z.B.Bayern)(Schwalmetal.,2010b).

Equiden

DieEG-VerordnungVO(EG)Nr.504/2008wurdemitderViehverkehrsverordnungvom03.März2010innationalesRechtüberführt.Danachsindab09.Juni2009geboreneEinhufermittelsMikrochipelektronischzukennzeichnen.

Schlussbetrachtung

Eineweltweite Normung der elektronischen Tierkenn-zeichnungistwichtigundsinnvoll,damitdieVorteilederelektronischenTierkennzeichnunganallenBedarfsstellengenutzt werden können. Auch können Synergieeffektez. B. bei der Verwendung der elektronischen Tierkenn-zeichnunginderVerfahrenstechnikoderdereinzeltierspe-zifischenÜberwachungnurgenutztwerden,wenndieseaucherkanntwerdenkönnen.An erster Stelle muss jedoch die Gewährleistung der

Einzigartigkeit der Tiernummer stehen. Dies kann nurüberDatenbankenerfolgen,indenendieausgegebenenNummerncodesgespeichertwerden.ImFalleeinerKenn-zeichnungmitLändercodenachISO3166obliegtdieVer-waltungdieserDatenbankunddieVergabederjeweiligenNummerndemjeweiligenLand. Istdiesnichtgewährlei-stetsollteeineKennzeichnungnurmitHerstellercodeer-folgen. IndiesemFalle liegtdieVerantwortungüberdieVergabeundAufzeichnungderNummernbeidemjewei-ligenHersteller(ICAR,2011a).

Mindestens ebensowichtigwie die einheitlicheKenn-zeichnung ist die Einrichtung zentralerDatenbanken fürTiere,indenenHalterinformationen,Tierbewegungenetcerfasstwerden.Nur so kann die Rückverfolgbarkeit vonTierenundFleisch,wievonderEUgefordert,gewährleis-tetwerden.

Literatur

Agri-Food&VeterinaryAuthorityofSingapore(2009)Veterinaryconditionsfortheimportationofdogs/cats[online].Zufindenin<http://www.ava.gov.sg/NR/rdonlyres/A6301E5F-8CE5-4ED4-A447-A2C3EF6216D6/12300/DOG-CAT311w_feeattd4.doc>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

AnimalQuarantineServiceJapan(2011)Guidetoimportingdogs,catandoth-eranimalssubjecttoanimalquarantinefromdesignatedregionsintoJapan[online].Zufinden in<http://www.maff.go.jp/aqs/english/animal/dog/pdf/guidefree-e20110430.pdf>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

AustralianGovernment/AustralianQuarantineandInspectionService(2011)Bringingcatsanddogs(andotherpets)toAustralia[online].Zufindenin<http://www.daff.gov.au/aqis/cat-dogs>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

CanadianCattle IdentificationAgency (2011)TheCanadiancattle Identifica-tionProgram[online].Zufinden in<http://www.canadaid.com/about_us/about_us.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ENZ(2011)MovingpetstoNewZealand[online].Zufindenin<http://www.emigratenz.org/moving-pets-to-new-zealand.html>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion (2007)Verordnung (EG)Nr.1760/2000desEuropäischenParlamentsunddesRatesvom17.Juli2000zurEinführungeinesSystemszurKennzeichnungundRegistrierungvonRindernundüberdieEtikettie-rungvonRindfleischundRindfleischerzeugnissensowiezurAufhebungderVerordnung(EG)Nr.820/97desRates[online].Zufindenin<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2000R1760:20070101:DE:PDF>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

Europäische Union (2008) Verordnung (EG) Nr. 504/2008 der Kommissionvom6.Juni2008zurUmsetzungderRichtlinien90/426/EWGund90/427/EWGdes Rates in Bezug aufMethoden zur Identifizierung von Equiden[online]. Zu finden in <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32008R0504:EN:NOT>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion(2008)Verordnung(EG)Nr.933/2008derKommissionvom23.September2008zurÄnderungdesAnhangsderVerordnung(EG)Nr.21/2004desRatesinBezugaufdieKennzeichnungderTiereunddenIn-haltderBegleitdokumente[online].Zufindenin<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:256:0005:0011:DE:PDF> [zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion(2008)Verordung(EG)Nr.998/2003desEuropäischenPar-lamentsunddesRatesvom26.Mai2003überdieVeterinärbedingungenfürdieVerbringungvonHeimtierenzuanderenalsHandelszweckenundzurÄnderung der Richtlinie 92/65/EWGdes Rates [online]. Zu finden in<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2003R0998:20081122:DE:PDF>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

Europäische Union (2009) Verordnung (EG) Nr. 759/2009 der Kommissionvom19.August2009zurÄnderungdesAnhangsderVerordnung(EG)Nr.21/2004desRateszurEinführungeinesSystemszurKennzeichnungundRegistrierungvonSchafenundZiegen[online].Zufindenin<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:215:0003:0004:DE:PDF>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion(2009)Verordung(EG)Nr.21/2004desRatesvom17.De-zember2003zurEinführungeinesSystemszurKennzeichnungundRegis-trierungvonSchafenundZiegenundzurÄnderungderVerordnung(EG)Nr.1782/2003 sowiederRichtlinien92/102/EWGund64/432/EWG [on-line].Zufindenin<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2004R0021:20090909:DE:PDF>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion(2010)Verordnung(EU)Nr.506/2010derKommissionvom14.Juni2010zurÄnderungdesAnhangsderVerordnung(EG)Nr.21/2004desRateshinsichtlichinZoosgehaltenerSchafeundZiegen[online].Zufin-

288

denin<http://eur-lex.europa.eu/Notice.do?checktexts=checkbox&val=517642%3Acs&pos=1&page=1&lang=en&pgs=10&nbl=1&list=517642%3Acs&hwords=506%252F2010%257E&action=GO&visu=%23texte> [zitiertam10.10.2011]

EuropäischeUnion(2011)Electronicidentificationofbovineanimals.[online].Zu finden in <http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/identification/bovine/elec_id_bovine_en.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

FoodChainEvaluationConsortium(FCEC)(2009)Studyontheintroductionofelectronicidentification(EID)asofficialmethodtoidentifybovineanimalswithin the European Union. [online]. Zu finden in <http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/identification/bovine/docs/EID_Bovine_Final_Report_en.pdf>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

Finkenzeller K (2008) RFID-Handbuch : Grundlagen und praktische Anwen-dungenvonTranspondern,kontaktlosenChipkartenundNFC.München:Hanser,528p

GreeneJL(2010)Animalidentificationandtraceability:overviewandissues.[online]. Zu finden in <www.nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/crs/R40832.pdf>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

HansenOK(2010) Introductionofmandatoryelectronic identificationofcat-tle in Denmark [online]. Zu finden in <http://www.icar.org/Documents/Riga_2010/index.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ICAR (2011a) Code of conduct [online]. Zu finden in <http://www.icar.org/pages/manifacturer_code_of_conduct.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ICAR(2011b)Manufacturercodes[online].Zufindenin<http://www.service-icar.com/manufacturer_codes/Manufacturers_DB/manufacturer_codes_main.asp>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ICAR (2011c) Duties [online]. Zu finden in <http://www.icar.org/pages/Sub_Committees/sc_animal_identification.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

IDEA-Project [online]. Zu finden in <http://idea.jrc.it/pages%20idea/final%20report.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ISO(2011)ISOaboutISO[online].Zufindenin<http://www.iso.org/iso/about.htm>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ISO(2011)ISOinbrief.[online].Zufindenin<http://www.iso.org/iso/pressre-lease.htm?refid=Ref1425>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

NolenRS(2004)Pet`sdeathrekindleselectronicIDdebate[online].Zufindenin <http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jul04/040701a.asp> [zitiert am10.10.2011]

SchwalmA,GeorgH,UdeG (2009)ElektronischeTierkennzeichnung.Land-bauforsch54(4):279-286

SchwalmA,GeorgH,UdeG(2010a)ElektronischeTierkennzeichnung:StatusquoinDeutschlandseitJanuar2010.Schafzucht10:1-3

SchwalmA,GeorgH,UdeG(2010b)GesetzlicheRegelungenzurKennzeich-nungvonHundeninDeutschland.Kleintiermed13(9/10):262-266

StatistischesBundesamtDeutschland–Destatis(2011)AltlasderAussenhan-delsstatistik[online].Zufindenin<http://ims.destatis.de/aussenhandel/Def-ault.aspx>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

ViehVerkV (2010) BekanntmachungderNeufassungderViehverkehrsverord-nungvom03.März2010[online].Zufindenin<http://www2.bgbl.de/Xa-ver/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGB>[zitiertam10.10.2011]

G. Ude, H. Georg, S. Bender, A. Schwalm / Landbauforschung - vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research 4 2011 (61)289-298 289

Eignung von Thermo-Injektaten zur elektronischen Tierkennzeichnung und Körpertemperaturerfassung bei Ziegen

GraciaUde*,HeikoGeorg*,SophiaBender*undAnjaSchwalm*

* JohannHeinrichvonThünen-Institut(vTI), InstitutfürÖkologischenLand-bau,Trenthorst32,23847Westerau,E-mail:[email protected]

Zusammenfassung

Die Erfassung der Körpertemperatur eignet sich zurFrüherkennungvonKrankheiten,diemiteinerÄnderungderKörpertemperatureinhergehen.BislangwirddieKör-pertemperaturzumeistrektalerfasst,wobeiderBedarfanautomatischen und kontinuierlich messenden SystemenalsManagementhilfeimmergrößerwird.ZieldieserStudiewardieÜberprüfung,obsichbeiZiegenzweiunterschied-licheApplikationsorte(OhrgrundundSchwanzfalte)alsIn-jektionsortundfüreinesubkutaneKörpertemperaturmes-sungeignen.Die subkutanenTemperaturenwurdenmitzwei unterschiedlichen Systemen erfasst. Parallel wurdedie Körpertemperatur rektal gemessen. In AbhängigkeitvonderAußentemperaturwarendieDifferenzenzwischenrektaler und subkutaner Temperatur unterschiedlich.DieAblagetiefederTransponderwarzuniedrig.DasOhreig-netsichnichtalsApplikationsortbeiZiegen.

Schlüsselwörter: Ziegen, Rektaltemperatur, subkutane Körpertemperatur, Injektat, Ökologischer Landbau, Preci-sion organic dairy farming, elektronische Tierkennzeich-nung

Summary

Research in goats with bio-thermo-transponders for electronic identification and body core temperature logging

Themeasurementofbodycoretemperatureisahelpfultoolfortheearlyrecognitionofdiseases ingoats.Uptonow,temperaturemeasurementisalmostdonemanuallymeasuringrectaltemperature.Nevertheless,thereisanin-creasingdemandonautomaticandcontinuouslymeasur-ingdevices.Theobjectiveofourstudywastheevaluationofinject-

able transponders with temperature sensing option ingoats.Inthestudyinjectabletransponderswithtempera-turesensorweretestedintengoatsattheskinfoldoftailandatasecondapplicationpointatthebaseoftheleftear.Thetemperaturesofthetransponderswererecordedusingtwodifferentmeasurementsystems.Therectaltem-peraturewasmeasuredsimultaneously.Independenceofseasons thedifferencesbetween rectal temperatureandsubcutaneous temperaturewere different. The depth oftheinjectabletransponderwastoolow.Theearisnotsuit-ableastransponderlocationforgoats.

Keywords: goat, rectal temperature, subcutaneous tem-perature, injectable transponder organic farming, preci-sion organic dairy farming, electronic identification

290

1 Einleitung

Die elektronische Einzeltierkennzeichnung bestimmterTierarteninnerhalbderEUundauchinanderenLänderngewährleisteteineschnelleRückverfolgbarkeitundleistetdamiteinenBeitragzurLebensmittelsicherheit (Georgetal.,2008).InDeutschlandwurdedieelektronischeEinzeltierkenn-

zeichnunginderViehVerkV,dieseitdem9.März2010inKraftgetreten ist, fürSchafeundZiegenumgesetzt.AlselektronischeKennzeichen fürSchafeundZiegengeltenOhrmarkenmitintegriertemTransponder,Bolus-Transpon-derundFußfesseltransponder(nurbeiTieren,dienichtfürdeninnergemeinschaftlichenHandelbestimmtsind).Injektatewerdenseit2009nachEU-RechtbeiderPfer-

dekennzeichnung eingesetzt, ansonsten werden sie beilebensmittelliefernden Tieren aufgrund der ProblematikbeiderRückgewinnungaufdemSchlachthofsehrkritischbewertet(Schwalmetal.,2010;Klindtworth,2007).Die kritischeMeinung zurNutzung von Injektaten zur

elektronischenKennzeichnungkönntedurch verbesserteMaßnahmenbeiderRückgewinnungunddurchdieVer-wendungintegrierterSensoren(z.B.Temperaturmessung),dieeinenZusatznutzenbedeutenwürden,gesteigertwer-den(Klindtworth,2007).

2 Literatur

ErsteProjektezurelektronischenTierkennzeichnungmitInjektaten begannen 1993/94 im Mittelmeerraum (Spa-nien, Portugal und Italien)mit insgesamt5000Schafen,3000Rindernund2000Ziegen,denenanverschiedenenInjektionsorten 32mm x 3,8mmgroße Injektate appli-ziertwurden.DazugehörtedasFEOGAProjekt(Cajaetal.,1994).ImRahmendesFEOGAProjektsinjiziertenFonsecaetal.(1994a)bei90Ziegen32mmx3,8mmgroßeInjek-tateamOhrgrund,derAchselhöhle,derLeistenbeugeso-wiedemSchwanz.DieLesbarkeitlagnachdreiMonatenbei93%amOhrgrund,100%anderAchselhöhle,98%inderLeistenbeugeund89%amSchwanz.DieVerlusteunddiebeschädigtenInjektatewarenimOhrgrund(2In-jektatebzw.6%)undimSchwanz(4Injektatebzw.7%)amhöchsten.Bei1362ausgewachsenenZiegenmitdem-selben Injektat, das in dieAchselhöhle appliziertwurde,warennachca.einemJahrnoch98%derInjektatelesbar(Fonseca,1994b).EsgabnurgeringeDifferenzeninBe-zugaufeinengeübtenoderungeübtenApplikator(Cajaetal.,1997).In Deutschland wurden spezielle Untersuchungen zur

elektronischenTierkennzeichnungbeiSchafenundZiegenaußerhalbdesIDEA-Projektsu.a.andersächsischenLehr-undVersuchsanstalt inKöllitschdurchgeführt(Wehlitzetal.,2006).EswurdendabeiInjektatederGröße23mmx

4mmverwendet.50InjektatewurdenimAltervon2bis5MonatenindieAfter-Schwanzfalteappliziert.DieVerlustebetrugen2%.AusderselbenApplikationbeiSchafläm-mern,dieindenerstenLebenstagenerfolgte,resultiertenVerlustevon24,1%.IneinemTestvonSimon(2006)mit120Ziegenaufzwei

Betrieben wurden die laktierenden Ziegen in der After-Schwanzfalte mit Injektaten gekennzeichnet. Die After-schwanzfalteistaucheinegutePositionbeiderMilchleis-tungsprüfungimMelkstand.DieVerlustratewarmitdreivon120Injektatengering.Bisher sindnurwenigeProjektemitBio-Thermo-Injek-

taten,dienebendertierindividuellenelektronischenKenn-zeichnung auch die Körpertemperatur erfassen können,durchgeführtworden.Goodwin(1998)hatbei30Ziegen,18Pferdenund35

SchafendieKörpertemperaturmiteinemInfrarotthermo-meterimOhr,subkutanüberMikrochip,appliziert indieAchselhöhle, und rektal mit digitalem Thermometer er-fasst.BeidenZiegenwarendierektalenundsubkutanenTemperaturen signifikanthöher alsdie Infrarot-Tempera-turen,wobeidierektalenundsubkutanenTemperaturensichmit einerDifferenz von0,2 °Cnicht signifikantun-terschieden.Die subkutaneKörpertemperatur zeigte diehöherenWerte.BeidenPferdenundSchafenwarendierektalenTempe-

raturensignifikanthöheralsdiesubkutaneKörpertempe-ratur.BeidenPferdenbetrugdieDifferenzdurchschnittlich1,6°C,beidenSchafen3,5°C.EineUntersuchungvonKamannetal. (1999)beschäf-

tigtesichmit15Kälbern.DieInjektatewurdenunterdemSkutulum,d.h.subkutanunterdemDreiecksknorpelamOhransatz, injiziert. Die Korrelation zwischen rektal undSkutulumbetrugr=0,82.AbderzweitenbiszurzehntenVersuchswochewardiesubkutaneTemperaturumdurch-schnittlich1,0 °Cniedriger als die rektaleKörpertempe-ratur.IneinerUntersuchungvonUdeetal.(2010)mitzwölf