The social and spatial implications of community action to enclose space: Guarded neighborhoods in...

Transcript of The social and spatial implications of community action to enclose space: Guarded neighborhoods in...

Cities 41 (2014) 30–37

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Cities

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate /c i t ies

The social and spatial implications of community action to enclosespace: Guarded neighbourhoods in Selangor, Malaysia

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.05.0030264-2751/� 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +60 3 79677620.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (P.A. Tedong), [email protected]

(J.L. Grant), [email protected] (Wan Nor Azriyati Wan Abd Aziz).

Peter Aning Tedong a,⇑, Jill L. Grant b, Wan Nor Azriyati Wan Abd Aziz a

a Department of Estate Management, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysiab School of Planning, Dalhousie University, Box 15000, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 4R2, Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t

Article history:Received 13 January 2014Received in revised form 25 March 2014Accepted 4 May 2014

Keywords:Class segregationFragmentation of public spaceGuarded neighbourhoodsGated communitiesMalaysia

The article examines the social and spatial implications of guarded neighbourhoods: resident-generatedenclosed areas in urban Malaysia. Neoliberal government practices provide a regulatory context withinwhich residents organise associations, levy fees, erect barricades, and hire guards to control formerlypublic streets and spaces. Citizen action to create guarded neighbourhoods concretise emerging classboundaries and reinforce social segregation within cities already noted for having significant ethnic dis-parities. Guarded neighbourhoods in Malaysia simultaneously reflect social exclusion—of non-residents,lower classes, migrants, and ethnic ‘others’—and cohesive social action of the politically and economicallypowerful to produce neighbourhood identity and community coherence through enclosure.

� 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Gating, enclosing, or privatising residential areas has becomeincreasingly common throughout the world (Atkinson & Blandy,2006; Glasze, Webster, & Frantz, 2006). Some authors see such pro-cesses as reflecting growing social polarisation (Marcuse & vanKempen, 2000, 2002) while others describe enclosure as a by-product of neoliberal urbanisation, in a time when states havereduced their regulatory role (Genis, 2007; Hackworth, 2007;Harvey, 2005). Whatever the factors producing them, enclosed res-idential environments universally generate social and spatialimplications for the cities that have them.

Malaysia has two types of enclosed developments (Tedonget al., in press-a): developers market gated communities inupscale suburban areas, while residents in older districts erecttheir own barricades to create guarded neighbourhoods. In thisarticle we examine the social and spatial implications of theguarded neighbourhoods, which are increasing rapidly in Malay-sia’s largest urban region. Guarded neighbourhoods are self-organised residential enclosures produced through residents’actions and investments in older urban districts. Residents havebanded together to create associations with the mandate ofcontrolling space in ways that control and potentially exclude

non-residents. National government decisions to roll back hous-ing programs generated a context within which residents turnedincreasingly to private markets to address housing needs(Tedong et al, in press-b); at the same time government initia-tives to roll out guidelines to govern enclosure of urban spaceframed specific types of market responses to fears of crimeand urban growth (Tedong et al., in press-a). The emergence ofguarded neighbourhoods in Malaysia reflects the simultaneousoperation of what Swyngedouw (1997) called global, local, andregional processes. Within a global context of neoliberalismand a state seeking to use its influence in the region to improvethe situation for ethnic Malays, the Malaysian government cre-ated conditions that encouraged local citizen action groups toself-organise to control urban territories. That process hasinscribed class on top of ethnic, racial, and religious differentia-tion in the city. As a consequence, Malaysian urban space hasbecome fragmented: that is, less socially and spatially permeableand accessible.

We begin by briefly reviewing the literature on the productionof gated and private communities to consider how enclosure con-tributes to social and spatial fragmentation. We then turn to dis-cuss a case study of Selangor state, near Kuala Lumpur inMalaysia, where guarded neighbourhoods are proliferating. Weargue that examining enclosure practices in urban Malaysia pro-vides an opportunity to explore ‘actually existing neoliberalism’(Brenner & Theodore, 2002) at work facilitating the social pro-cesses of spatial fragmentation.

1 British colonialism began in Peninsula Malaya in 1874. In 1963, Peninsula Malayabecame the independent Federation of Malaysia: Singapore seceded in 1965.

P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37 31

The production of enclosed residential neighbourhoods

Although enclosed and fortified settlements have a storied his-tory (Bagaeen & Uduku, 2010), contemporary gated communitiesbegan to emerge in large numbers as states adopted the politicalphilosophy of neoliberalism—that is, the notion that the state shouldreduce its role to allow the market to operate more efficiently andeffectively. Enclosure became common in the United States(Blakely & Snyder, 1997), Latin America (Caldeira, 2000; Thibert &Osorio, 2013), and parts of the Middle East (Glasze, 2006a, 2006b;Güzey, 2014) during the 1980s, and in Eastern Europe (Kovács &Heged}us, 2014; Smigiel, 2013) and China (Miao, 2003; Pow, 2007)after the fall of the Iron Curtain. As enclosed communities havebecome more common in urban development, scholars havebecome increasingly interested in documenting the processes pro-ducing them and the social and spatial implications they generate.

The urban processes that accompanied neoliberal economicrestructuring during and since the 1980s expanded the role of mar-ket forces in the housing and real estate sectors, privatised urbanand social services, and increased the role of elites in shaping land-scapes (Genis, 2007; Harvey, 2005). Partnerships between the stateand private sector often privatised and commercialised publicspaces and institutions (Hackworth, 2007), undermining accessto the public realm. In some countries, such as the United States,private communities became the norm for new developments(Kohn, 2004; McKenzie, 1994). Wood, McGrath, and Young(2012) argued that neoliberalism increased inequality in citiesand created new forms of exclusion. The results produced unevengeographies of urban development (Walks, 2009, p. 346).

Increasing isolation, boundaries, and separation between socialgroups characterises contemporary urban environment (Walks,2006). Hodkinson (2012, p. 505) described urban enclosure asthe ‘modus operandi of neoliberal urbanism’ as it privatises spaces,destroys use values, and seeks to displace and exclude the urbanpoor from parts of the city. Making space private allows authoritiesto use physical and social technologies to control access(Bottomley & Moore, 2007). Spatial ruptures generated by neolib-eral urbanism may be visible (as in walls and gates) or ephemeral(as in policing and access policies). The Malaysia case will illustratesome ways in which state policies and local history influence howneoliberalism manifests in particular locales.

Several agents can generate urban enclosure. In some situationsgovernments have adopted policies that encourage or requireenclosure. For instance, in China (Miao, 2003; Pow, 2007) and Sin-gapore (Pow, 2009) the state has used enclosure as a strategy forcompliant management and social control. McKenzie (2005) notedthat some U.S. jurisdictions effectively require private communi-ties by insisting on self-management of quasi-public elementssuch as streets and vegetation. Government deregulation oftenallows private development markets greater opportunities in pro-ducing housing. Gating offers a niche market for developers, andhas become the dominant practice in some countries. Changes tolegislation to permit condominium or strata ownership facilitatedthe rise of private communities in the 1980s in the U.S., Canada,and Europe (Kohn, 2004; McKenzie, 1994). Homeowners’, resi-dents’, and condominium associations have provided mechanismsfor resident initiatives to enclose and control space (Nelson, 2005).Neighbourhood actions to enclose older districts are common inplaces such as South Africa where crime rates are high and author-ities accept such community action (Landman, 2006), but rare else-where. Malaysia thus offers an uncommon example where residentagency produces enclosure.

Enclosures differentiate space for those inside from those out-side. By definition, barriers imply a level of social segregationand spatial fragmentation. In the neoliberal city, those inside thewalls are more commonly affluent than those outside: they use

enclosure to exclude others. In many cases, gated communitiesprivilege middle-class lifestyles and conspicuous consumption(Pow, 2009). Gated communities are often blamed for exacerbatingresidential and social segregation (Blakely & Snyder, 1997;Caldeira, 2000), although they may enable mix by providingsecurity for higher income residents living near lower incomeneighbours (Clement & Grant, 2012; LeGoix, 2005; Manzi &Smith-Bowers, 2005). The nature of social fragmentation—who isinside, and who outside—varies from context to context.

The spatial implications of enclosure on mobility and accessibil-ity in the city vary depending on the scale of enclosure and man-agement policies around entry. Large gated areas and robustmechanisms of enclosure and policing limit access, fragment space,and disrupt urban mobility (Grant & Curran, 2007). Enclosures thatreduce access to public goods and amenities, such as beaches orparks, are likely to prove socially as well as spatially disruptive(Clement & Grant, 2012; Grant & Rosen, 2009). Assessing thenature of restrictions provides insight into the extent to whichenclosure fragments the city.

Spatial planning and urban development in many regionsaddress the needs of those benefiting from the ‘neoliberal turn’(Tasan-Kok, 2012). In Southeast Asia, enclosure provides privacyand exclusivity for emerging elites (Leisch, 2002; Huong & Sajor,2010). Like other nations in the region, Malaysia reveals the influ-ence of neoliberal urbanism and globalisation, and has seen therise of new elites (Bunnell & Nah, 2004; Bunnell & Coe, 2005). Facil-itated by the liberalising policies of the state, enclosure is creatinga new landscape of control in contemporary Malaysia (Tedonget al., in press-b). Guarded neighbourhoods—with enclosure pro-duced by residents on public streets—illustrate the political effortsof urban middle classes to wrest control of spaces in the city.Within the context of Malaysia’s already racially-inflected socialdivisions (Gomez, 2004; King, 2008) enclosure adds social and spa-tial fragmentation based on class.

Locally contingent histories and cultural processes produceunique expressions of neoliberal urbanism (Grant & Rosen, 2009;Peck & Tickell, 2002). As we try to understand the changes in urbanstructures and processes wrought by contemporary economic andpolitical conditions exploring diverse circumstances and responsesproves informative. In the sections that follow we consider some ofthe social and spatial implications of guarded neighbourhoods inSelangor state in urban Malaysia. We argue that resident actionsto barricade streets increase social and spatial fragmentation. Casestudies of practice, such as that documented here, enhance under-standing of the processes generating increasingly divided cities.

Malaysian urbanism: a legacy of polarisation

The unequal geographical distribution of indigenous, ethnic,and migrant groups characterises Malaysian urbanism (Gomez,2004). Malaya society was racially segregated during British colo-nial rule1: ethnic communities of Malays, Chinese, Indians, andEuropeans were physically and socially segregated (Hirschman,1975, 1986; Khader, 2012). The rubber and tin industries, whichthrived from the late 1800s to the early 1920s, responded to labourshortages by importing migrant labour from India and China (Chin,2000; Tajuddin, 2012). By 1931, migrant groups outnumbered indig-enous Malays (Hirschman, 1975), but inter-ethnic social interactionsproved rare (Tajuddin, 2012). Colonialism produced a demographi-cally distinct and socially segregated landscape. Europeans, Chinese,and Indians lived in urban areas, while impoverished Malays occu-pied rural regions (Haque, 2003; Stark, 2006; Chakravarty &

32 P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37

Roslan, 2005). Socio-spatial fragmentation thus is not new in Malay-sia, although the character of urban fragmentation has changedsomewhat in the neoliberal era.

In the socioeconomic structure of Malaysia before indepen-dence, colonial practices generated ethnic and racial divisions(Hirschman, 1986; Masron, Yaakob, Ayob, & Mokhtar, 2012). Evenin towns where inter-ethnic contact was possible, residential areas,market places, and recreational spaces were typically segregatedalong ethnic lines (Hirschman, 1986; King, 2008). Colonial educa-tion policy reinforced ethnic segregation: English schools for thechildren of Malay and European elites, and vernacular schools forthe Malay peasantry and migrant communities (Chin, 2000). Thecolonial socio-spatial ethnic divide continues to have significantimpacts (Bae-Gyoon & Lepawsky, 2012). While in some senseMalaysia was a multi-ethnic society, in practice patterns ofinequality and ethnic difference were stark (Bunnell & Coe, 2005;Haque, 2003). At independence, the state inherited deeplyentrenched inequality across ethnic groups and regions (Jomo,1986; Jomo & Chang, 2008). Inter-ethnic tensions erupted in vio-lence in 1969, resulting in the deaths of many ethnic Chinese inurban areas. Continued immigration to provide low-wage labourfor industrial and service industries has fuelled security fears(Kassim, 1997). Inequality and ethnic tensions remain a majorchallenge in contemporary Malaysia (Hill, Yean, & Zin, 2012; Pak,2010), and provide the social context within which the neoliberalturn further fragments urban environments.

2 We employed purposive sampling of 29 respondents. Interviews lasted 60–0 min: some were recorded and transcribed for analysis, while others relied on noteking.

Neoliberal Malaysia

In recent decades Malaysia emerged as a neoliberal develop-mental state. After the 1969 riots, Malaysia’s political economyapproach increasingly reflected laissez faire policies, with someimport-substituting industrialisation and agricultural diversifica-tion (Gomez & Jomo, 1997; Jomo & Chang, 2008). The NewEconomic Policy (NEP) in 1970 restructured Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society to favour ethnic Malays (Stubbs, 1977). The NEPlegitimised government intervention for interethnic redistributionand rapid urbanisation (Jomo & Wong, 2008). In the early l980s,the Malaysian government began to liberalise regulations(Bae-Gyoon & Lepawsky, 2012). Influenced by neoliberal discourse,Prime Minister Mahathir’s regime (1981–2003) shifted from inter-ethnic redistribution to industrial modernisation and export pro-motion (Jomo & Chang, 2008; Lee, 1995). The state encouragedprivatisation and introduced tariff reductions and financial liberal-isation to attract flows of transnational capital (Chin, 2000). Thegovernment thus employed a regional development approach as acatalyst to create a post-industrial and post-racial society(Bae-Gyoon & Lepawsky, 2012). What Khoo (1995) called ‘marketnationalism’ replaced ethnic communitarism.

By the 1990s mass rural-to-urban migration resulted in a grow-ing Malay middle class in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor states(Abdul-Rahman, 1996, 2002), accompanied by high demand forsuburban housing (Thibert & Osorio, 2013). The government’s freemarket policy in housing privileged Malay ethnic and middle-classgroups. As the private market became more dominant, affluentpeople could meet their demands for housing, but the governmentignored the need for low cost housing for poor people. Economicinequality alongside uneasy inter-ethnic relations leaves peoplefeeling vulnerable (Chakravarty & Roslan, 2005). As a consequence,fear of crime and class segregation has grown, and has become thedominant motivation for enclosing communities (Tedong et al., inpress-b).

Malaysia has a long history of social and spatial fragmentation:first as a product of colonial political and economic choices, andrecently exacerbated by the economic effects of neoliberal

urbanism. In the next section, we examine the character of enclo-sure in Selangor state, surrounding the capital city of Kuala Lum-pur. We focus on how middle-class residents in older urbanneighbourhoods are actively transforming their areas to enforcesocial and spatial segregation. As residential groups organise toerect barricades and hire guards to protect their neighbourhoodsthey enhance the fragmentation of an already socially and spatiallydivided society.

Guarded neighbourhoods in Selangor state

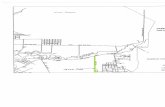

Since the 1980s, as the national government reduced its role inhousing construction, private developers increasingly builtenclosed residential communities in the fringe around the nationalcapital (Hanif, Abdul-Aziz, & Tedong, 2012). Selangor is a largelyurbanised state surrounding the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur,Putrajaya, and Cyberjaya. Rosly (2011) found 515 enclosed com-munities in Malaysia, with the highest concentration (407 guardedneighbourhoods) in Selangor (see Fig. 1). As developers built gatedenclaves in the urban fringe, groups in older residential neighbour-hoods began organising to close off their streets and hire guards toprivatise older urban areas (Tedong et al., in press-a). These self-initiated guarded neighbourhoods are proliferating rapidly andaffecting the social and spatial character of urban Malaysia.Recognising the need to regulate enclosure in some ways, nationalauthorities issued guidelines in 2010 (Tedong et al., in press-b): theguidelines limited the size of enclosures to 10 ha, specified wherethey could occur, and identified a process whereby residents couldrequest to barricade their streets.

Between 2011 and 2013 we conducted field work on guardedneighbourhoods in Selangor state. We began by analysing the spa-tial distribution and characteristics of guarded neighbourhoods toconstruct an inventory. Then we conducted in-depth interviews2

with representatives of residents’ associations, residents of guardedneighbourhoods, residents of open neighbourhoods, federal andstate government officials, and urban planners of four Selangor localauthorities to gain insights into the process of producing enclosure,the implications of barricades, and attitudes about private communi-ties. Observations of the guarded neighbourhoods and thematicanalysis of interview results revealed some socio-spatial implica-tions of guarded neighbourhood developments. The sections whichfollow summarise the findings. In particular, we show the ways inwhich respondents talked about the social and spatial implicationsof enclosed communities.

Fragmented urban landscapes

Spatial fragmentation and social segregation are not new toSelangor state, but the character of urban patterns is changingand significant implications are arising as enclosed communitiesbecome commonplace. Although some districts predominantlyaccommodate one ethnic group or another, many urban neigh-bourhoods in Selangor have a mix of Malays, Chinese, Indiansand other ethnic groups. In older neighbourhoods, traditionalgeographies based on ethnic and religious affiliation are beingoverlaid with spatial patterns and social differences based on class,housing type, tenure, and location.

Observations revealed that guarded neighbourhoods typicallyappear alongside main roads, with barricades closing smaller pub-lic roads that lead into the communities (Fig. 2). Housing in theenclosed area is usually two or more decades old. In one of the

9ta

Fig. 1. Distribution of guarded neighbourhoods in Selangor.

P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37 33

local authorities we surveyed, documents provided by staff and ourfieldwork identified 98 guarded neighbourhoods: most includedone or more public spaces such as playground areas (Fig. 3).

Guarded neighbourhoods fragment urban street patterns whenbarricades close public streets (Fig. 4). They make the city less per-meable and accessible. Residents’ associations that choose toenclose their areas usually erect entry points, often with make-shift barricades and guard houses. Our observations indicated thatmany guarded neighbourhoods enclose public spaces, such asparks or kindergartens, or community facilities, such as Muslimprayer houses. Thus they reflect the global trend that Webster(2002) identified of privatising public goods. Not only do barriersprevent easy access through public streets by cars, they limitaccess of non-residents to resources and services that the stateor other community agencies pay for and maintain. A resident ofan open neighbourhood we interviewed complained:

We are not allowed the use of the open fields and children’spark available within the area. Even if we are allowed to usethem, the security guards will insist on taking down our partic-ulars and ask me to surrender my [driver’s] licence or nationalidentification card [passport].

Enclosure seeks to ensure the orderly flow of human and motor-ised traffic in and out of the guarded neighbourhood, regulatingresidents and visitors to produce local safety and harmony. Some-times the closure of public roads has had tragic results, however.For instance, the ‘Kepong tragedy’ of 2011 saw a woman and herdaughter die in a fire that gutted their home in a gated residentialarea where the security barrier delayed entry for fire crews (Henry& Lim, 2011). An urban planner with the local authority acknowl-edged the challenge:

We are dealing with an ad-hoc planning approval (two years,renewable) of older areas that intend to secure communitiesby enclosing public roads. If something happens in the future– such as fire – fire engines and ambulances will have a hardtime getting through as public roads are closed by theresidents.

State government staff discussed the difficulty of creating con-nected communities when residents close public roads. The closureof public roads transforms the morphological structure of publicspaces and disturbs traffic networks. Barriers routinely force longer

Fig. 2. Enclosure in a sample guarded neighbourhood.

Fig. 3. Public playground inside guarded neighbourhood.Fig. 4. Closed public road in a guarded neighbourhood.

34 P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37

trips and alternative routes, concentrating traffic on open roads.Nearby residents of open neighbourhoods resented the inconve-nience, as one explained.

In order to send my children to the school situated just next tomy neighbourhood, I had to detour using the main road,although by right I should be able to use a short cut throughthe guarded neighbourhood.

We found guarded neighbourhoods segregated according tohousing types. Observations showed that residents’ associationsgenerally enclosed residential units that were relatively homoge-neous in type, tenure, and value (although often mixed in ethnic-ity). For instance, units in an enclosed community may be acluster of two-storey houses. One local authority staff personinterviewed acknowledged the pattern: ‘I have received guardedneighbourhood applications from residents’ associations . . . for

separation between, for example, double-storey houses and sin-gle-storey houses or vice-versa’. Boundaries contain homogeneityin housing value and form.

The cost of erecting barricades and hiring guards means thatenclosure has primarily occurred in middle-class neighbourhoods.A local authority staff person explained:

I would say that class segregation is happening in residentialdevelopment in Malaysia . . . These people [within the enclo-sure] can be considered urban elites. They are willing to pay amaintenance fee to establish enclosure on public roads byputting up physical barriers and hiring security guards.

As Abdul-Rahman (1996) noted, income inequalities and classstratification have been increasing in urban areas in Malaysia. Enclo-sure spatially marks higher social class. Most housing in the guardedneighbourhoods was owner-occupied by middle-income house-holds. The more affluent the area, the more robust the surveillancetechnologies: private security guards, CCTV, boom gates, and wall/

P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37 35

fences. As Low (2003, p. 89) argued, enclosure mechanisms offer a‘psychological buffer’ between insiders and outsiders, and reinforceunderstandings of difference. One resident of an open neighbour-hood highlighted the role of class in decisions about enclosure.

The guarded neighbourhood broke social interaction by closingthe public road and promoting segregation between outsidersand the community inside. I also believe that if economic back-ground was taken as the measure to define social distinction,this could be mean that only middle and upper class groupscan afford to live in guarded neighbourhood developments.

While the product of enclosure excludes non-residents, the pro-cess of enclosing may reflect the building of social capital within anarea. Establishing enclosure developments in older districtsrequires collective action from residents: the Selangor state gov-ernment requires agreement of 80% of local residents to permitenclosure. Organising to achieve such targets is no mean feat. Localinitiatives have been supported by government programs toenhance community development and security, such as giving fis-cal incentives to citizen groups for neighbourhood patrols (Tedonget al., in press-b).3 The residents of guarded neighbourhoods oftenexplained their actions by citing the risk of crime and the need toprotect and differentiate themselves from dangerous outsiders,especially illegal migrants.

In the mixed city, enclosure developments provide middle-classresidents with a sense of security and control while they live nearless affluent neighbours. Gates and guards offer more than justphysical barriers to define neighbourhood boundaries; they consti-tute symbolic markers to reinforce the elite status of inhabitants.Ubiquitous signage—‘Stop for security check’, ‘Visitors kindly regis-ter’—reminds outsiders of their secondary status. Access requirespermission from uniformed guards who often demand temporarysurrender of state-issued identity documents. In controlling accessto the spaces around their homes the residents of guarded neigh-bourhoods employ the power of private security services but alsorely on the state to sanction enclosure and to provide outsiderswith documents that guards can hold to guarantee compliantbehaviour.

Residents inside guarded neighbourhoods explained that theysought exclusive control over public spaces: what Hou (2010)described as expressing power and political control in space. Resi-dents appreciated enhanced privacy, exclusivity, and what Low(2003) called the ‘niceness’ created by enclosure. One residentexplained:

I wasn’t keen in the beginning, but it’s quite good, and the mostimportant thing is that my life has more privacy than before . . .

Our neighbourhood has become more prestigious . . . Outsidersare not allowed to enter our neighbourhood area without per-mission from security guards . . . You need to understand, I paidthe service fees to the resident association to better maintainthe area. Why should I allow strangers to enter our neighbour-hood and enjoy the public goods inside our community?

Those inhabiting guarded neighbourhoods described generallygood relationships within the enclosure. Some government staffmembers we interviewed lived in guarded neighbourhoods: oneurban planner said she had a good network of friends among resi-dents, but not with outsiders. Some other local authority staff,however, worried that guarded neighbourhoods could lead tosocial isolation, segregation, and fragmentation. One fretted aboutthe development of ‘private army communities’ in older residentialareas of Selangor.

3 For instance, under the Malaysian Budget 2013 the federal government allocatedUSD 1.3 million to finance neighbourhood watch activities (Najib, 2012).

A local authority worker noted that although guidelines governspatial design, traffic implications, size of development, perimeterfencing, and general planning control they fail to consider thesocio-spatial implications of enclosure for the wider society.

The current guidelines aren’t great because we don’t really con-sider the social implications. It is obvious that the guidelinesallowed neighbourhood areas to be divided into smaller parcels.This will create neighbourhood fragmentation based on types,tenure, and social class by restricting outsiders from entering.

Although the Malaysian state has facilitated enclosure by pro-viding guidelines, establishing approval processes, and continuingto provide upkeep on privatised public spaces (Tedong et al., inpress-b), some staff members of local authorities in Selangorexplicitly acknowledged negative social and spatial implicationsof guarded and gated neighbourhoods. One said,

Guarded neighbourhoods draw a line between lower, middle,and upper classes, and I am amazed nobody has condemned ityet as a serious factor of social segregation in residential areas.

Cohesion and fragmentation

After independence the Malaysian state promoted social inte-gration and the advancement of ethnic Malays through its NewEconomic Program. Other ethnic groups consequently becameincreasingly politically marginalised and security-conscious(Gomez, 2004). As a new middle class emerged in the early1980s, the economic transition from a state-led market to a mar-ket-led state facilitated the production of new kinds of enclosedcommunities in sub/urban areas. In recent development on theurban fringes private developers have taken advantage of whatThibert and Osirio (2013, p. 13) called the ‘internationalization ofconsumer tastes’ by creating upscale gated communities withwonderful amenities and luxurious lifestyles. Within older urbanneighbourhoods in Selangor, middle and upper income residentspiggybacked on government policies and urban fears to transformthe open but ethnic-inflected Malaysian city into increasingly spa-tially fragmented and bounded class-segregated spaces: guardedneighbourhoods. We have argued that such transformationoccurred within neoliberal conditions, as government facilitatedprivatisation and regulated resident and market actions to controlspace. The character of social and spatial fragmentation reflects theunique legacy of Malaysian society, history, and politics with itslingering racism and fear of others. The processes producingguarded neighbourhoods simultaneously bolster neighbourhoodin-class cohesion while increasing urban fragmentation. The resultis a complex, multicultural, compartmentalised city, with poor andaffluent groups spatially proximate yet socially distanced.

Guarded neighbourhoods reveal the complicity of the state inprivatising public spaces and governance functions. Enclosedenclaves break the urban fabric into smaller physical pieces thatenable localised community control while enlarging the grain sizeof urban blocks in the city’s transportation structure. By closingpublic streets and containing public spaces such as parks or com-mon amenities, enclosures change the relationship of non-residents to community spaces as well as to other residents.Guarded neighbourhoods in Malaysia simultaneously reflectsocial exclusion—of non-residents, lower classes, foreigners and‘others’—and cohesive social action of the politically powerful toproduce neighbourhood identity and community coherence. Theyreveal the way that rising elites shape the city as they are influ-enced by cultural history and empowered by changing socio-economic circumstances in a situation of actually existingneoliberalism.

36 P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37

Areas (such as streets) which had been public become redefinedas private as users of the (public) facilities now enclosed are rede-fined as potentially dangerous persons requiring surveillance andcontrol. The reality that guards feel comfortable asking for stateidentification from potential visitors appears to confer state per-mission for enclosure’s socio-spatial control.

With its empirical focus on enclosed communities in olderareas, our study illustrates neoliberal urban practice in fragment-ing cities. The state and private corporations are not the only activeagents transforming urban spaces. In Malaysia residents aresocially engaged in reconstituting public spaces as private as theysuperimpose class dynamics over efforts to manage ethnic differ-ences. The result is an increasingly divided city with more ‘no go’zones each year.

Acknowledgements

Funding from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia (SLAB/SLAI Unit), University of Malaya, and Bright Spark UM helped tosupport this research. The School of Planning of Dalhousie Univer-sity, Halifax, Canada provided a valuable opportunity for collabora-tion on the work. The authors thank the research participants forgiving generously of their time.

References

Abdul-Rahman, E. (1996). Social transformation, the state and the middle class inpost-independence Malaysia. Southeast Asian Studies, 34(3), 56–79.

Abdul-Rahman, E. (2002). State-led modernization and the new middle class inMalaysia. Fifth Avenue, NY: Palgrave.

Atkinson, R., & Blandy, S. (Eds.). (2006). Gated communities. London: Routledge.Bae-Gyoon, P., & Lepawsky, J. (2012). Spatially selective liberalization in South

Korea and Malaysia: Neoliberalization in Asian developmental states. In B.Gyoon, R. Chill, & A. Saito (Eds.), Locating neoliberalism in East Asia:Neoliberalizing spaces in developmental states. West Sussex, UK: BlackwellPublishing Ltd.

Bagaeen, S., & Uduku, O. (2010). Gated communities: Social sustainability incontemporary and historical gated developments. London: Earthscan.

Blakely, E. J., & Snyder, M. G. (1997). Fortress America: Gated communities in theUnited States. Washington: Brookings Institution and the Lincoln Institute ofLand Policy.

Bottomley, A., & Moore, N. (2007). From walls to membranes: Fortress polis and thegovernance of urban public space in 21st century Britain. Law and Critique,18(2), 171–206.

Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2002). Cities and the geographies of ‘actually existingneoliberalism’. Antipode, 34(3), 349–379.

Bunnell, T., & Coe, N. M. (2005). Re-fragmenting the ‘political’: Globalization,governmentality and Malaysia’s Multimedia Super Corridor. Political Geography,24(7), 831–849.

Bunnell, T., & Nah, A. M. (2004). Counter-global cases for place: Contestingdisplacement in Globalising Kuala Lumpur Metropolitan Area. Urban Studies,41(12), 2447–2467.

Caldeira, T. P. R. (2000). City of walls: Crime, segregation and citizenship in Sao Paolo.Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chakravarty, S., & Roslan, A. H. (2005). Ethnic nationalism and income distributionin Malaysia. The European Journal of Development Research, 17(2), 270–288.

Chin, C. B. N. (2000). The state of the ‘state’ in globalization: Social order andeconomic restructuring in Malaysia. Third World Quarterly, 21(6), 1035–1057.

Clement, R., & Grant, J. L. (2012). Enclosing paradise: The design of gatedcommunities in Barbados. Journal of Urban Design, 17(1), 43–60.

Genis, S. (2007). Producing elite localities: The rise of gated communities inIstanbul. Urban Studies, 44(4), 771–798.

Glasze, G. (2006b). Segregation and seclusion: The case of compounds for westernexpatriates in Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal, 66(1–2), 83–88.

Glasze, G. (2006a). The spread of private guarded neighbourhoods in Lebanon andthe significance of a historically and geographically specific governmentality. InG. Glasze et al. (Eds.), Private cities (pp. 127–141). Oxford: Routledge.

Glasze, G., Webster, C., & Frantz, K. (Eds.). (2006). Private cities: Global and localperspectives. Oxford: Routledge.

Gomez, E. T. (Ed.). (2004). The state of Malaysia: Ethnicity, equity and reform.Malaysian studies series. New York: Routledge, Curzon.

Gomez, E., & Jomo, K. (1997). Malaysia’s political economy: Politics, patronage andprofits. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Grant, J., & Curran, A. (2007). Privatised suburbia: The planning implications ofprivate roads. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 34(4), 740–754.

Grant, J. L., & Rosen, G. (2009). Armed compounds and broken arms: The culturalproduction of gated communities. Annals of the Association of AmericanGeographers, 99(3), 575–589.

Güzey, Ö. (2014). Neoliberal urbanism restructuring the city of Ankara: Gatedcommunities as a new life style in a suburban settlement. Cities, 36, 93–106.

Hackworth, J. R. (2007). The neoliberal city: Governance, ideology, and development inAmerican urbanism. New York: Cornell University Press.

Hanif, N. R., Abdul-Aziz, W. N., & Tedong, P. A. (2012). Gated and guardedcommunity in Malaysia: Role of the state and civil society. Paper presented at theplanning law and property rights conference, United Kingdom. <http://www.plpr-association.org/index.php/papers-publications> Accessed 10.05.13.

Haque, M. S. (2003). The role of the state in managing ethnic tensions in Malaysia: Acritical discourse. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(3), 240–266.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University PressInc.

Henry, E. R., & Lim, C. Y. (2011). Some neighbourhoods want barriers removed. TheStar. <http://www.thestar.com.my/story.aspx?sec=central&file=%2f2011%2f3%2f3%2fcentral%2f8173811> Accessed 14.10.13.

Hill, H., Yean, T. S., & Zin, R. H. M. (2012). Malaysia: A success story stuck in themiddle? The World Economy, 35(12), 1687–1711.

Hirschman, C. (1975). Ethnic and social stratification in Peninsular Malaysia.Washington: American Sociological Association.

Hirschman, C. (1986). The making of race in colonial Malaya: Political economy andracial ideology. Sociological Forum, 1(2), 330–361.

Hodkinson, S. (2012). The new urban enclosures. City, 16(5), 500–518.Hou, J. (Ed.). (2010). Insurgent public space: Guerilla urbanism and the remaking of

contemporary cities. New York: Routledge.Huong, L. T. T., & Sajor, E. E. (2010). Privatization, democratic reforms, and micro-

governance change in a transition economy: Condominium homeownerassociations in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Cities, 27(1), 20–30.

Jomo, K. S. (1986). A question of class: Capital, the state, and uneven development inMalaya. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Jomo, K. S., & Chang, Y. T. (2008). The political economy of post colonialtransformation. In K. S. Jomo & S. N. Wong (Eds.). Law, institutions andMalaysian economic development. Singapore: NUS Press.

Jomo, K. S., & Wong, S. N. (2008). Law, Institutions and Malaysian EconomicDevelopment. Singapore: NUS Press.

Kassim, A. (1997). Illegal alien labour in Malaysia: Its influx, utilization, andramifications. Indonesia and the Malay World, 25(71), 50–81.

Khader, F. (2012). The Malaysian experience in developing national identity,multicultural tolerance and understanding through teaching curricula: Lessonslearned and possible applications in the Jordanian context. International Journalof Humanities and Social Science, 2(1), 270–288.

Khoo, B. T. (1995). Paradoxes of Mahathirism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.King, R. (2008). Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya: Negotiating urban space in Malaysia.

Singapore: NUS Press.Kohn, M. (2004). Brave new neighborhoods: The privatization of public space. New

York: Routledge.Kovács, Z., & Heged}us, G. (2014). Gated communities as new forms of segregation in

post-socialist Budapest. Cities, 36(n/a), 200–209.Landman, K. (2006). Privatizing public space in post-apartheid South African cities

through neighbourhood enclosures. GeoJournal, 66, 133–146.Lee, B. T. (1995). Challenges of super induced development: The mega-urban region

of Kuala Lumpur-Klang Valley. In T. G. McGee & I. M. Robinson (Eds.), The mega-urban regions of Southeast Asia. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

LeGoix, R. (2005). Gated communities: Sprawl and social segregation in SouthernCalifornia. Housing Studies, 20(2), 323–343.

Leisch, H. (2002). Gated communities in Indonesia. Cities, 19(5), 341–350.Low, S. (2003). Behind the gates: Life, security and the pursuit of happiness in fortress

America. New York: Routledge.Manzi, T., & Smith-Bowers, B. (2005). Gated communities as club goods:

Segregation or social cohesion? Housing Studies, 20(2), 345–359.Marcuse, P., & van Kempen, R. (Eds.). (2000). Globalizing cities: A new spatial order?

Oxford: Blackwell.Marcuse, P., & van Kempen, R. (Eds.). (2002). Of states and cities: The partitioning of

urban space. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Masron, T., Yaakob, U., Ayob, N. M., & Mokhtar, A. S. (2012). Population and spatial

distribution of urbanisation in Peninsular Malaysia 1957–2000. Malaysia Journalof Society and Space, 8(2), 20–29.

McKenzie, E. (1994). Privatopia: Homeowner associations and the rise of residentialprivate government. New Haven: Yale University Press.

McKenzie, E. (2005). Constructing the Pomerium in Las Vegas: A case study ofemerging trends in American gated communities. Housing Studies, 20(2),187–203.

Miao, P. (2003). Deserted streets in a jammed town: The gated community inChinese cities and its solution. Journal of Urban Design, 8(1), 45–66.

Najib, M. A. R. (2012). Prospering the nation, enhancing well-being of the Rakyat: Apromise fulfilled. The 2013 budget speech presented at the Dewan Rakyat. <http://www.kabinet.gov.my/images/stories/pdf/20120928_budget_speech_2013.pdf>Accessed 25.01.14.

Nelson, R. (2005). Private neighborhoods and the transformation of local government.Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute Press.

Pak, J. (2010). Malaysia struggles for harmony as tensions bubble. BBC Online.20 February 2010. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/8524353.stm> Accessed 27.12.13.

Peck, J., & Tickell, A. (2002). Neoliberalizing space. Antipode, 34(3), 380–404.Pow, C.-P. (2007). Securing the ‘civilized’ enclaves: Gated communities and the

moral geographies of exclusion in (post-)socialist Shanghai. Urban Studies,44(8), 1539–1558.

P.A. Tedong et al. / Cities 41 (2014) 30–37 37

Pow, C.-P. (2009). Neoliberalism and the aestheticization of new middle-classlandscapes. Antipode, 41(2), 371–390.

Rosly, D. (2011). Planning guideline for gated community and guardedneighbourhood. Paper presented at the national conference land matters andupdates on latest law regulating the property industry, Putrajaya.

Smigiel, C. (2013). The production of segregated urban landscapes: A criticalanalysis of gated communities in Sofia. Cities, 35(n/a), 125–135.

Stark, J. (2006). Indian Muslims in Malaysia: Images of shifting identities in themulti-ethnic state. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 26(3), 383–398.

Stubbs, R. (1977). Peninsular Malaysia: The ‘new emergency’. Pacific Affairs, 50(2),249–262.

Swyngedouw, E. (1997). Neither global nor local: ‘Glocalization’ and the politics ofscale. In K. R. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of globalization: Reasserting the power of the local(pp. 137–166). London: Guilford Press.

Tajuddin, A. (2012). Malaysia in the world economy (1824–2011): Capitalism, ethnicdivisions, and ‘managed’ democracy. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books.

Tasan-Kok, T. (2012). Introduction: Contradictions of neoliberal planning. In T.Tasan-Kok & G. Baeten (Eds.), Contradictions of neoliberal planning: Cities, policiesand politics. New York: Springer Science.

Tedong, P. A., Grant, J. L., Abdul-Aziz, W. N. A. W., Hanif, N. R., & Ahmad, F. (in press-a).Guarding the neighbourhood: The new landscape of control in Malaysia, HousingStudies.

Tedong, P. A., Grant, J. L., & Abdul-Aziz, W. N. A. W. (in press-b). Governing enclosure:The role of governance in producing gated communities and guardedneighbourhoods in Malaysia, International Journal Urban and Regional Research.

Thibert, J., & Osorio, G. A. (2013). Urban segregation and metropolitics in LatinAmerica: The case of Bogotá, Colombia. International Journal of Urban andRegional Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12021.

Walks, R. A. (2006). Aestheticization and the cultural contradictions of neoliberal(sub)urbanism. Cultural Geographies, 13(3), 466–475.

Walks, R. A. (2009). The urban in fragile, uncertain, neoliberal times: Towards newgeographies of social justice? Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien,53(3), 345–356.

Webster, C. (2002). Property rights and the public realm: Gates, green belts, andgemeinschaft. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 29(3), 397–412.

Wood, P., McGrath, S., & Young, J. (2012). The emotional city: Refugee settlementand neoliberal urbanism in Calgary. Journal of International Migration andIntegration, 13(1), 21–37.