Conversion-testimonies.pdf - The University of Manchester ...

'The Organization of Giving and Ethnic Elites: Voluntary Organizations among Manchester Pakistanis

Transcript of 'The Organization of Giving and Ethnic Elites: Voluntary Organizations among Manchester Pakistanis

This article was downloaded by: [Professor Pnina Werbner]On: 28 July 2015, At: 05:55Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG

Ethnic and Racial StudiesPublication details, including instructions forauthors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20

The organization of givingand ethnic elites: Voluntaryassociations amongstManchester PakistanisPnina Werbner aa University of ManchesterPublished online: 13 Sep 1985.

To cite this article: Pnina Werbner (1985) The organization of giving and ethnicelites: Voluntary associations amongst Manchester Pakistanis , Ethnic and RacialStudies, 8:3, 368-388, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.1985.9993492

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1985.9993492

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of allthe information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on ourplatform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensorsmake no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy,completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views ofthe authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis.The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should beindependently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor andFrancis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings,demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, inrelation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private studypurposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of accessand use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnicelites: voluntary associations amongstManchester Pakistanis*

Pnina WerbnerUniversity of Manchester

Immigrant elites, to be worthy of this distinction, must gain the esteem oftheir fellows through current, and continuing, public action. They can rarelyrely on credentials of birth or family status. The demand for current proofof dedication and legitimacy stems from a commonly held view amongstimmigrants that, since they shared an early period of poverty and hardship,they are essentially equals (cf. P. Werbner, 1980b: 47-8). Hence, none maybe automatically elevated above their fellows. In this paper I discuss thelegitimating processes of an immigrant elite. Charitable giving, and the organ-ization of charitable donations, is singled out as a major means of accumulatinghonour and prestige. In some immigrant groups, I argue, such charitablegiving takes an agonistic form, as community leaders vie with one anotherin generosity, attempting to exceed their rivals' donations.1 Power strugglesthus take a peculiar form in these immigrant groups.2

Elite formation in immigrant groups is related to more general processesof change and growth. Economically, a community may gain a foothold in aparticular niche, and then expand into other economic fields (cf. P. Werbner,1980a, and 1984). Residentially, it may occupy a 'ghetto' area, and thenbegin to fan out from it (cf. P. Werbner, 1979b). These two processes may beregarded as forms of gradual encroachment. At the same time, the intimateand detailed cultural knowledge of first-generation migrants is replaced bythe partial knowledge of their children, with only a small cadre of religiousand cultural experts sustaining a comprehensive acquaintance with thegroup's 'original' culture.3 Socially, some immigrants may remain embeddedin close-knit networks whilst others come to have more tenuous links withtheir fellows. Hence, economic and social or residential immigrant 'cores'may form, with other immigrants on the 'periphery' of them.

In this changing context, it is necessary to understand organizationalprocesses from both a symbolic and a structural point of view. Symbolically,I stress a contrast between 'particularistic' and 'universalistic' symbols, whichpermeate different immigrant associations. Structurally, there is a basiccontrast between 'hierarchical' and 'non-hierarchical' organizations, theformer being the locus of elite competition. There is, in addition, a general

Ethnic and Racial Studies Volume 8 Number 3 July 1985© R.K.P. 1985 0141-9870/85/0803-0368 $1.50/1

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 369

process of organizational development: associations tend to become moreformalized and routinized, and then to federate across communities, AS theyfederate, they may become more hierarchical and 'professionalized' (cf.Miller, 1950: 220-3;Higham, 1978: 11-12).

The locus of competition may thus shift from one organization to another,and from the local to the national scene. In all this, the context of the stateis important: state agencies and para-agencies intervene in the processes ofimmigrant elite formation, both financially and in their choice of 'ethnicbrokers'. Moreover, the political power of an ethnic group must be seen interms of its ability to influence the state in various areas of political action.

I begin with a general discussion of the moral and symbolic implicationsof charitable 'giving' and, more generally, of contributions to ethnic associ-ations, based on my research amongst Pakistanis in Manchester. This is thenseen in the context of hierarchical and non-hierarchical ethnic associations.I then discuss a further contrast between associations stressing 'universalistic'or 'particularistic' symbols and values. Finally, a model of process and changein immigrant groups is put forth and the question raised: what constitutespolitical power in ethnic groups? Immigrants who settle in plural societiestend to be regarded, very rapidly, as just another 'ethnic' group, and through-out the paper the two terms are used interchangeably. It is, however, necessaryto specify at the start that the processes I analyse tend to occur in migrantgroups settled in plural, and primarily urban, societies.4

I. The morality of giving

The obligation of elites to make large-scale, generous and, indeed, extravagantcontributions to common causes has, perhaps, received less attention thenother forms of agonistic exchange. Yet such donations, made for culturallydefined communal ends, constitute highly potent symbolic acts. When madecompetitively, they encode differentiation and hierarchy, and serve to increaseindividual power and influence. Through such public generosity, members ofan elite establish their credentials as men of high status, and attempt tolegitimize their claims to positions of leadership.

Dominant strata within the immigrant community claim positions ofleadership through their activities in certain key ethnic associations. Theseprovide the central arenas in which communal and charitable contributionsassume a competitive, agonistic form. In other ethnic associations equalcontributions are fixed jointly by members, with an important shift in theirsignificance: being equal and balanced, they encode, symbolically, relationsof equality rather than of hierarchy.

Whether balanced or competitive, giving, it seems, always occurs withinrecognized limits of trust. The category encompassing donors and recipientsis, from this perspective, also conceived to be a 'moral community'. Throughhis donations an individual expresses membership in a circle composed ofmutually trusting others.5 Moreover, contributions made in different contextssignify an individual's identification with a progressively widening series of

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

370 Pnina Werbner

social groups — from a circle of known intimates, to the whole urban ethniccommunity including many unknown persons, and then further to the ethnicgroup as a whole, encompassing even those resident in a diaspora, as well asin the country or region of origin.

Thus, a Pakistani immigrant in Manchester donates towards the burial ofa friend or kinsman within a circle of intimates; he donates towards thebuilding of the local mosque, thus symbolically asserting his membershipin the local community; he contributes towards Pakistan national disasterappeals, thus expressing his identification with the people of Pakistan; andhe contributes to the 'poor', usually through the mosque, thus establishinghis membership in the brotherhood of Muslims. Indeed, he may even contri-bute across religions, thus expressing his view of himself as a member ofa common humanity.

Causes vary in the scope of their appeal: some are permeated with religiousideas and construed to be redemptive and linked to the achievement of grace,and the gaining of merit. They are, in Mauss's words, gifts 'made to men inthe sight of gods' (1966: 12). They appear to be associated with axiomaticand unquestionable imperatives. Perhaps for this reason causes such as thebuilding of a mosque become the inspiration of elite largesse. Welfare, thesurvival of the group through the provision of medical, educational and socialwelfare facilities, is often defined as another such religiously sanctionedcause, with a consequent emergence of powerful ethnic mutual help andwelfare associations.6

Amongst Pakistanis, as amongst many groups of labour migrants (cf. n. 6),regional or national causes are also perceived as being entitled axiomaticallyto unquestioning support, mobilizing even the irreligious, the sceptical andthe atheistic. Migrants are constantly called upon to raise charitable fundsfor their countries or areas of origin which are underdeveloped, and torn bywars or natural catastrophes. Frequent calamities become occasions for fund-raising drives. The banner of nationalism (or sometimes regionalism, as in thecase of African labour migrants), if imbued with religious imperatives regard-ing welfare and survival, is probably the most compelling cause for charitablefunding that immigrants recognize. In some groups the mobilization for suchcauses proves a testing ground for the group's elite; it sorts, elevates anddistinguishes the dedicated, the organizers, the prominent benefactors, andtheir supporters, from the nobodies, the impotents and the marginals (cf.Miller, 1950). In other groups, as amongst Pakistanis, procedures are stillsomewhat ad hoc and spontaneous, as I show below.

Not all communal causes invoke extensive support. Many voluntaryorganizations are formed for specific causes which are supported only bysmall groups of migrants. The plural interests and different groupings withinthe migrant community are expressed in a myriad of voluntary associations,each espousing different causes and interests. Thus, Pakistanis in Manchesterare active in a large number of dissimilar associations. Some of these areeasily recognizable as specifically 'ethnic': they bear self-consciously ethniclabels, they promote Pakistani causes, they are formally constituted on an

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 371

exclusive basis. Yet the interests they represent differ; indeed, sometimesthey conflict or compete with one another (as, for example, in the case ofpolitical parties). Other associations, by contrast, though largely or entirelyPakistani in membership, are somewhat less recognizable, and may even beorganized on an informal or ad hoc basis. Similarly, there is a great variationin the extent to which associations emphasize distinctive values as againstsymbols thought to be widely shared with the host society.

Given the various interests of Pakistanis, their diverse backgrounds andtheir different career patterns as labour migrants, it would be a gross mistaketo analyse as the Pakistani associations merely the most visible ones. A com-prehensive view is essential in order to appreciate the way associations struc-ture and codify relations within the community. Following a model put forthby Thomas and Znaniecki in their study of the Polish-American communityin Chicago (Thomas and Znaniecki, 1958, II: 1575), I distinguish three majortypes of associations by reference to their modes of recruitment and scale ofoperation: (i) 'local' associations devoted to specific goals and composed ofintimate circles of friends and associates within a wider urban ethnic com-munity; (ii) the 'territorial' association which serves as a central focus for thewhole urban ethnic community (such as the parish); (iii) 'super-territorial',federated, hierarchical associations, uniting together local associations from alarge number of different urban ethnic communities.

Two of Thomas and Znaniecki's hypotheses concern the genesis anddevelopment of ethnic voluntary associations. First, they argue that anethnic community goes through different phases in its development ofvoluntary associations, from local and territorial associations in the initialphase to super-territorial ones at a later phase. The latter develop only afterthe territorial organization of the community is fully established, togetherwith a myriad of local associations which are variously connected to it —some supporting, some opposing, and some independent of it.

The second hypothesis states that federated associations are always com-posed of local associations from different urban localities, which sharesimilar ideologies or purposes. Pakistanis thus have super-territorial organiza-tions uniting welfare associations, religious organizations or political partieson a national basis.

The value of Thomas and Znaniecki's model lies in the relation it sets upbetween associational type and social scale, thus allowing for a better under-standing of the way ethnic activities, and ethnic representation, occur. Itwill be shown, for example, that associations claiming to represent thecommunity as a whole are typically based on a narrow range of recruitment,primarily from within a self-appointed elite. The model thus enables us toanalyse the way ethnic groups, and particularly ethnic elites, can operateeffectively within a community which, in Glazer's terms, 'is an amorphousentity. It is not defined in law, . . . its "leadership" is not defined formally orpublically' (Glazer, 1978: 19). Moreover, the model allows for cross-culturalcomparisons: in East Africa, for example, where ethnic voluntary associationsare based on an ideology of extended patrilineages, the three associational

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

372 Pnina Werbner

levels are integrated into an extremely powerful super-territorial organizationwhilst still retaining separate functions at the different levels (cf. Parkin,1969 and 1978).

My comparison between 'hierarchical' and 'non-hierarchical' organizationscontrasts two modes of accumulating 'symbolic capital' (cf. Bourdieu, 1977,esp. 177-83). In hierarchical associations, the symbolic capital of the group isincreased through the competitive accumulation of symbolic capital byindividual members. In non-hierarchical associations, where contributions arefixed and equal, the symbolic capital of the group, as a brotherhood ofequals, is transcendent, and allows for no individual competitiveness. Thenature of group solidarity thus differs in the two types of association. Com-mon to both is the fact that group organizers become focal accumulatorsof symbolic capital.

I use the notion of 'symbolic capital' advisedly, for Pakistanis makeexplicit references to the moral and symbolic connotations of voluntarycontributions. Indeed, the underlying Islamic ethos of 'giving' in the form ofsadqa (alms), sacrifice and zakat which I discuss elsewhere (Werbner, 1979a:79-112) combines here with notions of noblesse oblige typifying the pervasivehierarchical relations of Pakistanis, like those of others originating from theIndian sub-continent.

Thus, while the organization of giving as presented here is an analyticconstruct, the symbolic and moral meanings which I analyse are based oninformants' statements. Hence part of the presentation is an attempt toindicate what forms of giving are seen to be highly valued. I discuss, in thiscontext, why it is that contributions to rotating credit associations lack themoral and symbolic connotations attached to contributions made to burialsocieties, despite the apparent procedural similarities. Informants' statementsalso explain the connection between contributions made to the home countryand to burial collections.

II. Surpassing a rival: big men and donors

I turn first to a discussion of the South Pakistani community's territorialorganization — the mosque. This is the central forum in which the elitecompetes to legitimize its status.

In 1978, Pakistanis were engaged in a £250,000 building project, of which£200,000 had already been raised. The pace of fund-raising, which hadincreased dramatically since 1971, was held back only by delays in theconstruction process. Funds were raised during Friday meetings at themosque and on religious festivals. In addition, a number of key persons alsoconvened small gatherings of businessmen to appeal for funds, or visited thempersonally. The chairman of the Mosque Committee assured me that fund-raising for the mosque had been unexpectedly easy, and there had never beenany trouble raising the sums required.

Intense rivalry characterized contributions for the mosque project, increas-ing the level of sums donated by elite members. Challengers of the current

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 373

committee, demanding that much delayed elections to the committee beheld, were crushed under the weight of promised donations made by membersof the ruling faction. Would they, it was asked, be willing to guarantee thecompletion of the building project? Would they sign a note to that effect?

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the large donors and professionals who mannedthe Committee and did most of the fund-raising were accused of denying the'working classes' their constitutional rights. Thus, the chairman reported of acomplaint made to him: 'After the meeting someone came to me and askedme - but who are the representatives of the working classes? I had no answerso I told him to come along to the next meeting.'

The issue of the control of the Committee was often presented in such'class' terms by informants. This categorization obscured the very recent riseof the 'upper' class, mainly successful traders in the garment industry (cf.Werbner, 1980a and 1984). Thus from the chairman of a recently foundedwelfare association: The wholesalers think they are the top and can lookdown on the working class. But most of them are uneducated. They areactually the working class.'

The process of elite formation within a recently arrived immigrant groupcan thus be very rapid: early arrivals, somewhat better established than theirfellow migrants, are the first to take control of community institutions.Significantly, they compete with one another whilst presenting a unitedfront against external challengers.

In self-interested terms, charitable benefaction can be seen as a strategyin seeking personal influence and prestige, by surpassing a rival in generosityand thus, in Levi-Strauss's words, 'taking from him privileges, titles, rank,authority, and prestige' (Levi-Strauss, 1957: 85). Undoubtedly, wealthyPakistanis were not to be outdone by business competitors or mere employees.They were, moreover, seeking 'to earn the social approval of their peers'(Blau, 1964: 109).

There was, however, also a sense of noblesse oblige, a self-accrediting ofelite status. Their donations were 'a symbolic token of their responsibility,and hence of their basic credentials for power and leadership in the group'(Gouldner, 1973: 278). In Blau's words, through such benefaction theyestablished 'a claim to moral righteousness and superiority' (op. cit.: 260).The threat to this 'claim to moral righteousness' came from the religiousleaders, poor but with godliness on their side. The two elites, business-cum-professional and religious, together dominated the community. While appar-ently at loggerheads, they serviced each other's needs in a symbiotic fashion.On the whole, open encounters were avoided (cf. also Scott, 1972), and fewmigrants were prepared to participate in such confrontations. The politics ofdelay, procrastination and 'blind probes' were more common (cf. R. Werbner,1977a). Cross-cutting ties between members of the elite were too extensiveand final splits too costly. Divisive issues were often relegated to the level ofpersonalities (a divide between two Islamic schools, Deoband and Brailwi,did, however, cause a major public confrontation in 1984, splitting the eliteand excluding central figures from the mosque).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

374 Pnina Werbner

It must be stressed that there are no donors and recipients in the contextof mosque fund-raising. All are givers. Often, indeed, it is the active fund-raisers, rather than the largest donors, who are regarded as the most praise-worthy and influential.

Although all are givers, donations are seen in relative terms, and this iswhat makes them markers of hierarchy. For a factory worker, the donationof the 'big man' within his circle is impressive: 'I met Choudhry at themosque on Eid, and he asked me how much I had contributed to the buildingfund. He himself had contributed £100.1 told him I had contributed just £2.I am only a poor man I said.'

An ethnic elite will emerge only when the majority of the large contribu-tors are also linked socially and economically. In the case study presentedhere, it is Pakistani business competitors and credit extenders who competethrough vast donations in the religious context, and through overwhelmingmutual hospitality in the domestic-ritual and ceremonial context (cf. P.Werbner, n.d. and 1981). They form close-knit networks; their relationshipstend to be multiplex even in the urban context; there is a measure of con-sensus amongst them regarding the relative statuses of various individualswithin their circle (on this detailed knowledge within the ethnic elite, cf.Miller, 1950: 212). All these characteristics, seen together, make it possibleto label this group — analytically — an 'elite'. This is not to say that ethnic'leaders' all belong to this circle. On the contrary, many do not. The impor-tance of a leader within the group is, however, significantly influenced by thecollective opinion of the elite — a dangerous opponent may be respected, afalse 'pretender' dismissed as insignificant.

The territorial organization need not be the central arena for elite com-petition, especially when members of the elite are not observant. Welfareassociations may take over from religious organizations, and the centraldrama of elite competition through giving may shift to these, or to thenational scene. Whatever the case may be, certain communal ethnic institu-tions tend to emerge as arenas where relations of hierarchy and dominanceare codified and publically established. Other associations, by contrast, arebased on the equal sharing of expenses between office holders and activemembers. I examine this type of association next. Once again, I draw on myPakistani case material.

III. Local associations — sharing amongst equals

Perhaps the classic instance of an association based on balanced sharingbetween equals is the rotating credit association, widely found throughoutthe world; such associations are characterized by equal contributions whichbring equal returns to all association members. In Manchester Pakistanis runmany rotating credit societies, known as kommittis, and they are particularlypopular amongst working women (usually machinists in the garment industry)and self-employed migrants. Each is usually run by a highly respected and

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 375

reputable member of the community who announces that she or he is startinga kommitti and invites other (selected) people to join it. Procedures "arysomewhat, but usually the organizer is entitled to the first week's collectivecontributions. The order of payment is then decided through a lottery inwhich names are placed in a hat and picked out by a child. However, membersof a kommitti usually agree to allow a few members in urgent need of moneyto take their share out of turn. Kommittis thus allow for some considerationof pressing needs, even though members do not necessarily know all theother members of the kommitti except by name or reputation. Their mainlink is to the organizer, either directly, or indirectly via an intermediary whocollects money from a number of people and then passes it on to the organizer.The pot in these associations varies, usually, from about £300 to £1,000 in£5 to £25 weekly payments.

The associations depend for their successful operation on mutual trustand the traceability of members: they are an extremely useful means ofsaving for migrants starting new business ventures, going on trips to Pakistan,holding a large wedding or simply wishing to save for unforeseen contingencies(cf. Light, 1972: 58-9). Migrants claim that otherwise they would be unlikelyto save, that the association compels them to save, but there is also the addedadvantage that if they are lucky they can get the money they need quickly.However, whilst kommittis of this type are useful ways of saving, they are notassociated with the creation of moral bonds. They are too practical, with thegiving and taking completely balanced. Their significance is entirely differentfrom that of the other institutionalized form of mutual aid prevalent amongstlow-income groups, which bases itself on unbalanced, charitable donation tothose in need.

Until about 1978 mutual aid was based in workplaces such as factorieswhich united Pakistani workers in pooling and mutual aid. The most commontype of local association prevalent in the community, although completelyinformal, was the factory 'set'. When a fellow worker died, factory workersmade a collection known as chanda to help his family with burial costs, andoften with the repatriation of his body to Pakistan. Even before 1978 collec-tions sometimes exceeded £500 (the cost of repatriation), especially if thedeceased had no large family in Britain to share the heavy financial burden.Chanda was sometimes also collected for bereaved families by neighboursor men of local reputation in the central residential cluster where manyPakistanis live.

At that time, the focus of mutual aid was in factory and neighbourhoodfriends, and Pakistanis who lost their jobs also lost their social club, theirinsurance in case of emergencies and their meeting place for making newfriends. The implications of chanda were not merely financial — migrantscould often afford to repatriate bodies with the help of loans from relatives— but moral as well. The donation proved the migrants' willingness to supportone another in any unforeseen and unforeseeable disasters. The reliance wason support from within the community, predictable support, in case thesocial services offered by the host society ceased to be available. Furthermore,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

376 Pnina Werbner

the implications of the donation were that social and emotional support willalso be forthcoming for the widow and her children.

The morality of giving for chanda, however paltry the sum, was stressedby one Pakistani worker, who also commented that such a value was absent,in his experience, from the system of values of the host society. The alterna-tive moral order Pakistanis adhered to was thus seen to be of superior worthand, moreover, of greater universality and humanity than that of the hostsociety, despite the hosts' dominance and evident economic and politicalsuperiority. He told me:

'About four years ago a man died in an accident and we collected money.We only collected from the Pakistani workers — about one or two poundseach. Even giving a penny is something [i.e. it is a moral duty]. There wereabout 30 to 35 Pakistani workers. Only one Englishman gave something— Derek. The same Derek died later of cancer. I went to visit him in thehospital and his wife told me he was saying he worried about his son. Soafter his death I collected money in the factory for him. The Englishworkers gave 5p or lOp, and the Pakistanis more. I also collected fromthe management and then I gave all the money to the management topass on to the family.'

It is highly significant that the same set of workers also collected donationsfor the various war and disaster funds announced by the Pakistani govern-ment. In one Manchester factory in 1975, £1,600 was collected for an earth-quake fund from workers on all shifts. The money from these funds is usuallytransferred to the Pakistani embassy, or to a special Pakistani bank accountannounced via the embassy. Ultimately, the Urdu newspapers publish a list ofdonors and factories and the amounts which they contributed. For the 1975earthquake fund, for example, over £350,000 was collected in the whole ofBritain. In the factory mentioned, I was told that each worker gave £5 a weekfor up to ten weeks. For the war funds announced in 1965 and 1971, someworkers gave all their wages for two to five weeks. In 1971 all the workersgave a whole week's pay in the first week. The sums to be donated aredecided on collectively, and workers feel morally compelled to comply withthe decision taken.

Burial collections and contributions to the home country, both expressiveof moral bonds, are explicitly linked: a factory worker explained that he hadto contribute to disaster collections, as otherwise workers would not collectchanda for him if he died suddenly. Hence a continued commitment toPakistan, expressed through charitable contributions, is seen as a prerequisitefor continued moral relations, in a brotherhood which accepts the responsib-ility for providing a person with a desired form of burial, and for taking careof his family in a strange country.

Continued loyalty to the home country has been shown to persist in someethnic groups even among second- and third-generation descendants ofmigrants. For these descendants the home country often becomes a focus ofmore permanent and long-term 'progressive' welfare goals. Among Pakistanis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 377

in Manchester, however, contacts with the home country were still personal.Their contributions were made, not so much to 'progressive' goals (schools,hospitals and suchlike), but at times of natural disaster or war. The organiza-tions they maintained were therefore intermittent and informal. They cameinto being spontaneously as the need arose. The factory and neighbourhood'sets' were close-knit, with members who shared the same premises regardingthe expected performance on different occasions; they acted in unison whenthe need arose.

This spontaneous, ad hoc type of arrangement underwent a radical changearound 1978 with the founding, in Manchester, of formal burial societies knownas 'Death Associations' or, colloquially, like the rotating credit societies, as'kommittis'. Death associations are formally constituted and have five electedofficers: a chairman, a secretary, a treasurer, a person responsible for the reli-gious arrangements surrounding the death (e.g. the preparation of the body),and a person responsible for the travel arrangements surrounding the transport-ation of the dead person's body to Pakistan. The organization has a separatebank account and funds can only be withdrawn with the authorization of threesignatories. It holds, I am told, regular meetings. The association functions asfollows. A collection is made in advance of a death, with each member of theassociation making an equal contribution which is fixed collectively. It costsabout £500 to send a body to Pakistan with an accompanying person. If adeath occurs, the burial fund is handed over and a new collection is made.There is thus always sufficient money in the fund to provide for suddenburial and travel arrangements.

The association I know of, the W.R. Death Association, was foundedin 1978 with around 20 members, all from the Jhellum area. Each memberat that time contributed £25 to the burial fund. The society has grown overthe past five years and now has 100 members, each contributing £5 to thefund. The money is collected from every working person and the contributorsrepresent whole families. My informant told me that while membership islimited to Manchester, it is not necessarily regionally exclusive. However,the W.R. Death Association had, he told me, recruited all its members fromJhellum. The association was founded by a 'man of reputation' who used tocollect chanda from Jhellum families when a person died. My informant saidthat 'it became too difficult, collecting chanda in people's houses. When oneknocked on the door they would complain, say they were eating or busy, soinstead we founded the association.' There were 'many many' such associa-tions all over Manchester, he claimed (cf. n. 8).

The founding of formal burial societies represents a predictable develop-ment: ethnic associations tend to become more formalized and routinizedover time (cf. Higham, 1978). The radical implications of this formalizationwill, however, emerge more clearly in the course of the following discussion.Suffice it to say here that, unlike other Pakistani formal associations whichwere run by the elite, these burial societies are formed at the grass-rootslevel, catching up persons who are otherwise not involved in voluntaryassociations. They thus create an organizational infrastructure which is

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

378 Pnina Werbner

entirely independent of elite largesse or of religious control. It is also indepen-dent of the state, as my informant was at pains to stress. Moreover, it tendsto provide a comprehensive organizational framework which is regionallybased, and this has potential for further growth and federation. Indeed, thesigns that this is about to occur are already there: my informant told methat the current size of his association was too large and they were thereforehoping to split it — initially into two associations with 50 members in each.Later, perhaps, they might divide into associations of 25 members. The largesize of the association made the collection of contributions cumbersomeand complex.

IV. Class and association

The management of associational size is thus a strategic problem for migrants:most local associations appear to achieve some optimum size; beyond thissize, they may split. This stems from the fact that much voluntary activityat the local level is underpinned by sociability, and arises from the need toovercome residential dispersal, and to join with others of like background.

Local associations thus tend to be based on class, region, age, sex andcommon interests, and differ fundamentally, in this respect, from territorialorganizations which encompass persons from a widespread geographicalcatchment area, from opposing classes, and having clashing interests.

What tends to occur in local associations is a simultaneous differentiationby class, region and interest. This is possible because the geographical area orregion of recruitment for local associations expands as the class pyramidnarrows. In other words, working-class migrants, who form the majority inthe community, organize on a narrow geographical base, mainly for purposesof mutual aid (forming, for example, burial societies), whilst elite migrants,far fewer in number, join other elite migrants, from amuchwidergeographicalcatchment area, in separate associations. Usually these have more global aims as-sociated with the culture, religion, politics and welfare of the group as a whole.

Although the aims are global, the size and mobilizing potential of theassociations is usually restricted. Such associations are, at the local level,no different in their membership size from other local associations, eventhough here the membership is drawn from a relatively small elite group.

Most fundamental to an understanding of the organizational power ofethnic groups is, therefore, the ways in which this power is mobilized andexercised. Two key factors must be accounted for here:

1. The mobilizing potential of ethnic associations — the level at whichthey are able to recruit funds and supporters.

2. The perimeters of the social field commanded by the ethnic group —what diverse resources and key areas of activity (economic, political,educational, etc.) can be influenced through the direct personal contactsof its members. I turn first to a more general discussion of the mobiliz-ing potential of ethnic groups.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 379

V. The mobilizing potential of voluntary associations

I have argued that different voluntary associations within an ethnic groupvary in their mobilizing potential. Hence the mosque, we saw, was the peakof the Pakistani community's organizational achievements: it has elicitedboth extensive largesse and a great deal of voluntary activity on the partof the local elite and has, as well, widespread support outside this elite.Consequently, leadership of the Mosque Association is hotly contested, andleaders have to prove their worth publicly. The achievement of office is there-fore a prize, conferring respect and public kudos on current holders.

The organizational power of different ethnic groups may also vary markedly.Thus it may be argued that this power increases in relation to an ethnicgroup's ability to enlist funding and personal support (a) across class divisionsand (b) at a supra-local, rather than merely local, level. Evidence of theability shown by some ethnic groups to build up powerful super-territorialorganizations may be found in the literature on Jewish and East Europeanethnic associations in the United States, or the Luo, Ismaili or Ibo organizationsfostered in East and West Africa.9

From an organizational perspective, a dichotomous contrast between'leaders from the periphery' and the 'centre' (Lewin, 1950), or 'traditional'and 'formal' leaders (Anwar, 1979: 174, 183; Aurora, 1970: 97, 102) isinadequate:10 the power and legitimacy of ethnic leaders relates, mostfundmentally, not to their personal attributes or status but to the organizingpotential of the associations they run. Since leaders require funding, voluntarysupport, an organizational infrastructure and agreed ends in order to beeffective, what distinguishes outstanding leaders is the organizational basethey build up.

Within organizations it is, however, pertinent to analyse the power basesof individual office holders. Miller has argued that an important distinctionbetween leaders relates to their power, on the one hand, and their prominence,either within the community or beyond it, in the host society, on the other(Miller, 1950; cf. Figure 3). While I cannot, because of lack of space, detailthe characteristics of individual leaders, it does appear that some are recruitedbecause of their prominence or professional qualifications whereas othersrely on support groups. Defining such support groups categorically is not,however, an easy matter. In attempting to fathom the politics of the mosque,for example, one is struck by the apparent ambiguity of the issues underlyingfactional confrontations. This stems, I think, from the different bases ofsupport leaders rely upon, which range from shared ideological commitmentsto kinship ties, personal obligations or social connections. Support groupsare thus 'action sets' (cf. Mayer, 1966, on Indian politics). In this contextit is therefore spurious to distinguish 'traditional' from 'modern' or 'formal'leaders, since all rely to some extent on 'traditional' ties.11

More important is the fact that beyond the mosque, the mobilizing powerof Pakistani associations is more limited.. A myriad of cultural, religious andpolitical associations are run mainly by the local religious or secularly educatedelite, who usually fund them without enlisting any further support from

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

380 Pnina Werbner

within the wider community. While some are supported by outside agencies,their organizational infrastructure reflects their low mobilizing potential,apart from sporadic meetings, particularly of the cultural societies.12 Theelitist tendency is apparent also at the trans-local level; the local associationsare united in umbrella organizations but these too are limited in the scope oftheir activities.

Particularly striking is the restricted mobilizing potential of Pakistaniwelfare associations or societies, for, after all, these claim to represent 'thePakistani community'. They too are funded and run by small cliques fromwithin the elite. Their activities are aimed at political representatives of thehost society, and they make little attempt to fund-raise for communal projects,or to mobilize large numbers of people from within the community forpublic demonstrations or other voluntary activities.

Such associations are united at the trans-local level by an umbrella organ-ization, SCOPO (the Standing Conference of Pakistani Organizations), whichis likewise elitist and limited in the scope of its activities. I have demonstratedthat even collections for Pakistani disaster appeals were not handled throughthe welfare associations, but relied primarily on the spontaneous response ofmigrants at the local and factory level. The donated funds were channelledto the Pakistani embassy via a bank account especially set up for this purposein the various Pakistani banks. The state of Pakistan in effect pre-empted theneed for co-ordinated action. As a result, welfare associations have certainlynot replaced territorial organizations as the focus of elite competition. Officeholders in these associations lack the legitimacy and public recognitionaccorded those in the territorial organization of the community. Nevertheless,they play a crucial representative role in the style and etiquette they adoptand the symbolic values they stress.

VI. The social field — symbolic orientations

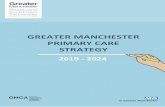

We have already seen that associations may be placed along an organizationalaxis, according to whether they establish relations of hierarchy or equality.In similar vein, associations may also be placed along a symbolic axis accord-ing to whether they serve to draw exclusive group boundaries or to assert aninclusive shared culture uniting the immigrant group with its hosts.13 Whereasthe cultural and religious associations run by the elite are manifestly inward-looking, seeking to sustain migrants' cultural heritage in a strange country,welfare associations run by the same elite tend, in promoting relations withthe host community, to assert universalistic values.14 In Figure 2 I set out thebasic organizational model I am proposing.

Seen together, the various associations constitute a wider field of powerand influence. Within this field the two symbolic orientations are bothmanifest, demonstrating a fundamental tendency in mobile ethnic groupswho start from an initial position of disadvantage and underprivilege. In suchcases, I argue, 'political ethnicity' is two-faceted, it has a dual orientation. Itinvolves, as Cohen has argued,1S a tendency to foster particularistic cultural

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 381

Figure I.Ethnic associational types

ORGANIZATIONHierarchical

Boundary-crossing orbridging associations

(a) run by the elite(b) highly federated, super-

territorial 'welfare'associations, whichbecome a focus of elitelargesse

SYMBOLIC Unjyersal^EMPHASIS Tncjusjve

(a) 'Joint'bridgingassociations ('AllBlack', 'Anti-NaziLeague', etc.)

(a) Territorial organizations(mosques, schools, etc.)

(b) Boundary-marking local/federalassociations (cultural,religious, etc.) run by the elite

^ ParticularisticExclusive

(a) Mutual aid and burial societies(b) rotating credit associations(c) sports and youth associations

Equality-marking

symbols, excluding outsiders, defining group boundaries and protectingperceived group assets; but it also, I would argue, involves simultaneouslythe tendency to emphasize universalistic, inclusive symbols16 shared with thehost society, and on this basis to demand equal rights and seek to gain a foot-hold in economic or political domains hitherto beyond group members'reach. Thus, despite their low mobilizing potential, Pakistani gatekeeperassociations fulfil an important role, seen in terms of the symbolic stressthey represent. In cases where such associations build up organizationalpower, they usually displace territorial organizations as a focus of elitecompetition (cf. Figure 2). This often occurs at a later developmental phase.

The dual symbolic orientation has to be understood in processual terms.Thus, Pakistanis in Manchester, initially poorly paid wage labourers with noproperty or local investments, have successfully expanded into a niche inthe garment industry, and are consolidating their position within it (cf.P. Werbner, 1984). With the capture of the niche has come an increase inthe confidence and overall wealth of the community, viewed as a whole.Yet the community's concentration primarily within a single niche makes ithighly vulnerable to market fluctuations. The collapse of the niche wouldundermine a position achieved over a period of some thirty years. In consider-ing 'political ethnicity', this paradoxical feature of niche occupation shouldbe recognized: the strength of a group, deriving from the command of aniche, also spells its vulnerability.

Few ethnic groups are totally concentrated within single niches. There is acontinuous process of mobility into a variety of occupations and economicfields. This tendency towards predatory expansion often involves 'pioneers'who continue to retain links to those within the niche. Pakistanis, for example,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

382 Pnina Werbner

Figure 2. Leadership styles

MOBILIZING POTENTIAL

High

(consultative)

EFFECTIVEMEDIATORS'REFORMERS'**

SYMBOLICSTRESS

UniversalInclusive

(Negotiation

Accommodation)^

GATEKEEPER/REPRESENTATION'EMBLEMATIC'"

ORGANIZERS OF PUBLIC PROTESTDEMONSTRATIONS ORFESTIVALS/CARNIVALS

[(Demand

I Protest) * " Exclusive

PROTEST RHETORIC

(non-consultative)

(may lack prominence, legitimation or prestige)*

Low

Figure 3. Leadership types*

POWER+

PROMINENCE +

CentralCommunityLeaders++

HonorarypositionsBrokers(with host soc.)+ —

The 'power berthe throne'+ —

'Pretenders'

•Based on Miller (1950)."Based on Huggins (1978).

"•Based on Myrdal (1944).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 383

run many businesses outside the garment industry, and are increasinglyentering into professional occupations.

The process of expansion and consolidation is associated with the processof elite formation in ethnic groups. The pioneers and consolidators, moresuccessful than their fellows, and linked together in close-knit networks,tend to assume positions of leadership and to emerge as a recognizable elite.They seek to legitimize their position and gain further prominence by activelybuilding community institutions and through undertaking a lion's share ofthe 'giving' needed to build community projects. As differentiation within theethnic group increases, different elites may emerge, and the projects theyfoster may vary from mosques to sports clubs.

Economic success and a mastery of the host culture do not, in otherwords, spell a necessary attenuation of either public or private displays ofethnic uniqueness. On the contrary, diacritical symbolic behaviour, both inthe form of enhanced ritual and religious practices, and of internal politicaland financial mobilization, is revived and recreated at a time when membersof an ethnic group begin to compete successfully in the economic, profes-sional, and political arenas of the wider society — in other words, when anelite begins to emerge.

Hence, increasing ability to master the wider culture in some contextsgenerates a renewed emphasis on the group's parochial culture, as membersof the elite compete with one another, both in the domestic and the politicalcontexts, through prodigious symbolic exchanges. Both weddings and mosquesgrow, accordingly, in size and sumptiousness (cf. Werbner, n.d.).17

Seen ahistorically, different loci of value, or 'centres', emerge within theethnic group:18 there is, first and foremost, the 'centre out there' — thecountry of origin which encapsulates all the cultural vitality of the group.Locally, there are loci of economic value, such as the 'rag trade', tying personstogether in diverse economic relations; there is also a residential core, a'ghetto' area; there is a commercial centre; and there are cadres of religiousor cultural experts who continue to sustain cultural and religious institutions.Outside these 'centres' is a constantly evolving 'periphery'.

The argument may be seen, perhaps, as a natural development of Cohen'shypothesis regarding 'political ethnicity' (cf. Cohen, 1969, 1974a, 1974b,1981), but as it applies to initially underprivileged minorities with noeconomic or political assets to protect. Cohen argues that alternative, 'covert',non-political forms of organization, based on ritual or kinship ties, are utilizedto protect ethnic achievements where overt political organization would beunacceptable. In societies which permit open political organization by variousinterest groups, however, groups may organize themselves overtly for politicalpurposes, as well as parading their separate cultural identity in festivals,rallies and other public forms of expression. Here particularistic culturalactivities, as I have shown, complement actual political organization.19

The political 'power' of an ethnic group must then be measured in termsof its ability to influence the political and legal system, in order to protector enhance the status of group members, to affect foreign policy towards

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

384 Pnina Werbner

the home country, and to control jobs and patronage in the economy.The most politically powerful groups, I would argue, are those who

succeed in sustaining a vital link between "cultural' centre and 'entrepre-neurial' periphery. The reasons for this are obvious: the centre providesan institutional framework and a moral underpinning of group activity. Thewider occupational diversity at the periphery provides flexibility, influencein such diverse fields as banking, big business, the media, or educationalinstitutions, as well as in political parties proper; these may all increase thepolitical effectiveness of the group. This is only so, however, as long asentrepreneurs on the periphery continue to retain viable links to the centre,and to compete for status within particularistic cultural organizations.

Thus, it may be argued that symbolic manipulation in ethnic groupsrelates to the centre-periphery structure of the group. The most successfulmanipulators are entrepreneurs in the widest sense of the word, often at theperiphery. By enmeshing themselves in agonistic exchange with fellow entre-preneurs, they nevertheless remain tied to the group centre, even whentheir actual cultural knowledge is superficial, and their participation in groupaffairs sporadic and partial.

For persons on the periphery the problem is one of establishing theirethnic identity. They do so through continued links to the centre, links whichmay be confined solely to 'giving' for ethnic causes or to the rare attendanceat religious festivals. But even these minor acts establish a claim to a commonestate, and are a basis for the building up of trust with other entrepreneurs -who may be equally peripherally involved in ethnic cultural activities. Thenetwork of relations which these tenuous links imply can nevertheless bemobilized, when the need arises, by active members of the elite. In this wayeven marginal members of an ethnic group may contribute to the political'power' of the group.

VII. Conclusion

Much debate on the nature of ethnicity has been characterized by a grossbinarism, and an oversimplification of the notion of 'interest'. The stress onboundaries, the definition of the group, has shifted attention away from afield approach, which views the group as a differentiated field of socialrelations, having several foci or centres, and characterized by a distributionof different interests. The 'monolithic interest' approach, as defining ethnicboundaries, is based on a circular assumption: quite often, the only unifiedinterest which members of a stratified and differentiated ethnic group share isthe interest in the protection or advancement of their status, irrespective oftheir class or occupational position. But this begs the question of who maybe classed as a group member.20

I haver tried instead to analyse certain generative processes in ethnicgroups; in particular, I have examined the agonistic exchange of symbolicgoods and labour which inspire much ethnic public activity and appear, as Idemonstrate, to structure the organization of the group. Fundamental moralideas draw an ethnic elite into public action. In Bourdieu's words, 'Above all,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 385

wealth implies duties' (1977: 180). As members of an ethnic group prosper,they build large edifices which set them, and the group, apart.

Notes

*The fieldwork on which this paper is based was conducted in the Manchester Pakistanicommunity during 1975-8, with the support of a grant from the Social Science ResearchCouncil, UK, and some further data was also collected during the following five years.Earlier versions of the paper were presented to the International Sociology Conference,Uppsala, 1978, for the section on Trans-national Voluntary Organizations, and to thedepartment of Sociology at Manchester's departmental seminar. I wish to thank theorganizers and participants in these events for their comments, and, in particular, PeterWorsley and Hamza Alavi. I am indebted also to Emanuel Marx of Tel Aviv Universityfor his helpful suggestions, and to Richard P. Werbner for his incisive comments on anearlier draft of the paper.1. Mauss argues about the gift that 'the agonistic character of the presentation ispronounced. Essentially usurious and extravagant, it is above all a struggle betweennobles to determine their position in the hierarchy to the ultimate benefit, if they aresuccessful, of their own clans' (Mauss, 1966: 4-5). On agonistic exchange cf. alsoStrathem (1971: 1-2).2. Usually, I would surmise, such competitive 'giving' occurs in societies where acultural form of reciprocal agonistic exchange prevails, as expressed in large-scale feastingand gift exchanges amongst Pakistanis in Manchester and in Pakistan (cf. P. Werbner1979a, ch. IV).3. Gumperz et al. (1982) talk of the 'new' ethnicity which 'depends less upon geo-graphic promixity and shared occupations and more upon the highlighting of key differ-ences separating one group from another' (p. 5). These key diacritica replace comprehen-sive cultural knowledge, which becomes the domain of experts.4. This includes, I would argue, processes occurring in the towns of modern developingnations in Africa and Asia. It is perhaps worth mentioning, however, that certain typesof overt political action by ethnic groups are permissible only in democratic societies,or in societies explicitly based on communalistic politics.5. 'Trust' implies a long-term relationship and a willingness to defer the return ofdebts (cf. Blau, 1964). It also implies a somewhat diffuse notion of exchange.6. Notably amongst Jews and other European immigrant groups in the United States(cf. Higham, 1978), amongst African labour migrants such as Ibo or Luo (cf. Morrill,1967; Parkin, 1969, 1978; Oginga Odinga, 1967), etc. These same organizations oftenespouse regional or national causes as well.7. I was told that such associations were common in Pakistan, especially amongstmembers of the lower castes.8. I was unable to study these associations, since they emerged after the completionof my research, and I have information regarding only one association. There is clearlya need for further research on such associations. It might be worth mentioning, in thiscontext, that neither the collection of chanda nor the operation of kommittis has beendiscussed so far, to my knowledge, in the growing literature on Pakistanis in Britain.9. On Jews cf. Miller (1950), Glazer (1978);on East Europeans cf. Barton (1978);onLuo in East Africa cf. Parkin (1969, 1978), Ross (1975), Oginga Odinga (1967); onIsmailis in East Africa cf. Hallam (unpublished manuscript); on Ibo in West Africa cf.Morrill (1967).10. Lewin argued, it will be recalled, that ethnic groups are often represented bymobile, successful members of the group who have distinguished themselves, but whoaspire primarily towards acceptance by the host society, adopt its viewpoint, and aretherefore ashamed of the group they represent and its 'peculiar' customs (Lewin, 1950).They agree to assume positions of leadership 'partly as a substitute for gaining status inthe majority, partly because such leadership makes it possible for them to have and

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

386 Pnina Werbner

maintain additional contact with the majority' (ibid.: 193).11. A central concern running through analyses of ethnic leadership has been (a) thedegree to which leaders are embedded within specifically 'ethnic' networks or rely ontheir contacts and knowledge of the host society, and (b) the extent to which theirleadership is based on an appeal to particularistic values (such as kinship), or on con-temporary achievements (such as the achievement of wealth, political office or profes-sional prominence). Thus Anwar contrasts 'integrationists' and 'segregationists' (op. cit.,173), Aurora, 'instrumental' and 'model' leaders (op. cit., 102-4), Helweg 'social worker'and 'broker' (1979: 80-2). Similar types of distinctions have been made, outside Britain,by Eisenstadt (1954: 193-5), and Huggins (1979: 96-7), who makes an importantdistinction between 'emblematic' and 'reformist' leaders, the former being persons whohad 'attained prominence and respect, often by remarkable personal achievement, whoseprincipal concern was not reform but the effective manipulation of the system' (96),while the latter believed that 'significant reform . . . was only likely to come as a resultof organized political pressure' (105). Miller, as mentioned, in an important article onleadership, (1950) argues that the central distinguishing features of leadership relate totwo main dimensions: power and prominence (1950: 201-9). He analyses processes oflegitimation and the achievement of prestige in terms of these two dimensions of leadership.12. One of the cultural societies received a large grant for the construction of a com-munity centre from urban aid. In a forthcoming article I discuss in greater detail therelation between state aid and ethnic leadership.13. Gunnar Myrdal, in his classic study of the black American community (1944)first made the contrast between 'protest' and 'accommodation' as two styles of ethnicleadership (Vol. II: 779). Beetham (1970) has an illuminating discussion of the twostyles of political ethnicity. A battle in the transport industry over Sikhs' rights to wearturbans at work was conducted in Manchester and in Wolverhampton. The skillful useof British democratic procedures along with an emphasis on shared values (e.g. jointservice in the British army) proved, in Manchester, far more conducive to race relationsthan an empalisis on distinctive, communal values in Wolverhampton. See also Desai'ssuggestive discussion of early Indian voluntary associations in the Midlands (1963:88-107).14. The situational manipulation of ethnic categories and identities has been extensivelydiscussed in the literature on ethnicity, from the seminal work of Mitchell (1956) tomore recent studies (cf. Handelman, 1977).15. Cohen (1969, 1974a, 1981) has argued that groups will revive and reinvent theirparticularistic culture in defence of interests threatened by outsiders. He calls thisprocess 'political ethnicity'. I am proposing that as their mastery of the dominantculture increases, and as they achieve greater economic prosperity, immigrants tend torevive, revitalize and reinvent their particularistic culture. In other words, not only theoutside threat to entrenched interests, but also internal processes of mobility are accom-panied by a revitalization of exclusive symbols.16. I am indebted for this distinction to the discussion of Turner (1974) and RichardP. Werbner (1977b) on regional cults, where a similar duality of emphasis pervades cultorganization.17. Pakistani entrepreneurs, who were the central founders of community institutionsand organizations, were also more likely to hold domestic ritual and ceremonial eventsthan more conservative non-entrepreneurs (cf. P. Werbner 1981).18. I define a 'centre' or 'core' as having two main features: (a) it is a locus of value(economic, cultural, etc.), (b) the value is maintained by persons connected by close-knit networks to one another.19. 'Political ethnicity' thus combines public (and even aggressive) expression of thegroup's separate culture in some contexts, with a similarly overt mastery and participa-tion in the culture of the host society in other contexts. Moreover, 'political ethnicity'is more effective when this mastery includes the achievement of coveted political,economic and professional positions in the wider society, whether or not the group

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

The organization of giving and ethnic elites 387

also occupies a specific economic niche. I do not deal here with political 'machines'and ethnic voting which exemplify this tendency in its most extreme form (cf. Glazerand Moynihan, 1963).20. In an excellent article on this subject, Hannerz (1974) analyses ethnic interest indifferentiated and stratified ethnic groups, and the ethnic strategies employed wheresocial mobility threatens to undermine group solidarity. Essentially, he argues, urbanethnicity should be viewed in a 'diachronic perspective' (p. 72). My analysis here shows,I feel, that there are many parallels to be drawn between the immigrant experiencein Britain and the United States. A review of the debate on class and ethnicity can befound in Ross (1973: 56-73).

References

ANWAR, MUHAMMAD 1979 The Myth of Return: Pakistanis in Britain, London,Heinemann.AURORA, G.S. 1967 The New Frontiersmen, Bombay, Popular Prakashan.BARTON, JOSEF J. 1978 'Eastern and Southern Europeans', in John Higham (ed.),Ethnic Leadership in America, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press,150-75.BEETHAM, DAVID 1970 Transport and Turbans, Oxford, Oxford University Press.BLAU, PETER M. 1964 Exchange and Power in Social Life, New York and London,John Wiley & Sons.BOURDIEU, PIERRE 1977 (French 1972) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge,Cambridge University Press.COHEN, ABNER 1969 Custom and Politics in Urban Africa, London, Routledge &Kegan Paul.COHEN, ABNER 1974a 'Introduction' in Abner Gohen (ed.), Urban Ethnicity, ASAMonographs 12, London, Tavistock Publications, ix-xxiv.COHEN, ABNER 1974b Two Dimensional Man, University of California Press.COHEN, ABNER 1981 The Politics of Elite Culture, Berkeley, University of CaliforniaPress.DESAI, R. 1963 Indian Immigrants in Britain, Oxford University Press for the Instituteof Race Relations.EISENSTADT, S.N. 1954 The Absorption of Immigrants, London, Routledge & KeganPaul.GLAZER, NATHAN 1978 'The Jews', in John Higham (ed.), Ethnic Leadership inAmerica, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 19-35.GLAZER, NATHAN, and DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN 1963 Beyond the MeltingPot, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.GOULDNER, ALVIN W. 1973 For Sociology: Renewal and Critique in SociologyToday, London, Allen Lane.GUMPERZ, JOHN J. and JENNY COOK-GUMPERZ 1982 'Introduction: Languageand Communication of Social Identity', in John J. Gumperz (ed.), Language and SocialIdentity, Studies in International Sociolinguistics 2, Cambridge, Cambridge UniversityPress, 1-21HANDELMAN, DON 1977 'The Organization of Ethnicity', Ethnic Groups, Vol. 1, 3,187-200.HANNERZ, ULF 1974 'Ethnicity and Opportunity in Urban America', in Abner Cohen(ed.), Urban Ethnicity, ASA Monograph 12, London, Tavistock Publications, 37-76.HELWEG, A.N. 1979 Sikhs in England: The Development of a Migrant Community,Delhi, Oxford University Press.HIGHAM, JOHN 1978 'Introduction' in John Higham (ed.), Ethnic Leadership inAmerica, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1-18.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015

388 Pnina Werbner

HUGGINS, N.I. 1978 'Afro-Americans', in John Highham (ed.), Ethnic Leadership inAmerica, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press.LEVI-STRAUSS, CLAUDE 1957 'The Principle of Reciprocity', in Lewis A. Coserand Bernard Rosenberg (eds), Sociological Theory, Macmillan.LEWIN, KURT 1950 'The Problem of Minority Leadership', in Alvin W. Gouldner (ed.),Studies in Leadership: Leadership and Democratic Action, New York, 192-7 (reprintedfrom Resolving Social Conflicts by Kurt Lewin, Harper & Brothers, 1948).LIGHT, IVAN 1972 Ethnic Enterprise in America, Los Angeles, University of CaliforniaPress.MAUSS, MARCEL 1966 The Gift, translated by Ian Cunnison, London, Cohen & West.MAYER, ADRIAN 1966 'The Significance of Quasi Groups in Complex Societies', inM. Banton (ed.), The Social Anthropology of Complex Societies, ASA Monographs 4,London, Tavistock Publications.MILLER, NORMAN 1950 'The Jewish Leadership of Lakeport', in Alvin W. Gouldner(ed.), Studes in Leadership: Leadership and Democratic Action, New York, 195-227.MITCHELL, CLYDE 1956 'The Kalela Dance', Rhodes-Livingstone Journal, 27, Man-chester University Press for the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute.MORRILL, W.T. 1967 'Immigrants and Associations: the Ibo in Twentieth CenturyCalabar', in L.A. Fallers (ed.), Immigrants and Associations, The Hague, Mouton.MYRDAL, GUNNAR 1944 An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and ModernDemocracy, New York.OGINGA, ODINGA 1967 Not Yet Uhuru, London, Heinemann.PARKIN, DAVID 1969 Neighbours and Nationals in an African City Ward, London,Routledge & Kegan Paul.PARKIN, DAVID 1978 The Cultural Definition of Political Response, London,Academic Press.ROSS, MARC HOWARD 1975 Grass Roots in an African City, Cambridge, Mass., MITPress.SCOTT, DUNCAN 1972 Immigrant Politics, PhD thesis, Bristol University.THOMAS, WILLIAM I., and F. ZNZNIECKI 1958 The Polish Community in America,Vol. II, New Dover Edition, Dover Publications Inc.TURNER, VICTOR 1974 Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in HumanSociety, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.WERBNER, PNINA 1979a Ritual and Social Networks: A Study of Pakistani Immigrantsin Manchester, PhD Thesis, Manchester University.WERBNER, PNINA 1979b 'Avoiding the Ghetto: Pakistani Migrants and SettlementShifts in Manchester', New Community, VII, 3, 376-89.WERBNER, PNINA 1980a 'From Rags to Riches: Manchester Pakistanis in the TextileTrade', New Community, VIII, 1 and 2, 84-95.WERBNER, PNINA 1980b 'Rich Man Poor Man or a Community of Suffering: HeroicMotifs in Manchester Pakistani Life Histories', Oral History, 8, 7, 43-8.WERBNER, PNINA 1981 'Manchester Pakistanis: Life Styles, Ritual and the Making ofSocial Distinctions', New Community, IX, 2, 216-29. Reprinted in The New Sociologyof Modern Britain, ed. Eric Butterworth and David Weir, Fontana (1984).WERBNER, PNINA 1984 'Business on Trust: Pakistani Entrepreneurship in the Man-chester Garment Trade' in R. Ward and R. Jenkins (eds), Ethnic Communities in Business:Strategies for Economic Survival, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 166-88.WERBNER, RICHARD P. 1977a 'Small Man Politics and the Rule of Law: CentrePeriphery Relations in East Central Botswana', Journal of African Law, 21, 1, 24-39.WERBNER, RICHARD P. 1977b 'Introduction' in Richard P. Werbner (ed.), RegionalCults, ASA Monographs 16, London, Academic Press, ix-xxxvii.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Prof

esso

r Pn

ina

Wer

bner

] at

05:

55 2

8 Ju

ly 2

015