The Emperor's New Body

Transcript of The Emperor's New Body

S E C R E T SOF THE

F A L L E NP A G O D A

THE FAMEN TEMPLEAND TANG COURT

CULTURE

Eugene Y. Wang

Tansen Sen

Wang Shen

Alan Chong

Kan Shuyi

Pedro Moura Carvalho

Libby Lai-Pik Chan

Conan Cheong

ASIAN C I V I L I S A T I O N S M U S E U M

The Emperor's New BodyE U G E N E Y . W A N G

since its discovery in 1987, die Famen Temple crypt and its acclaimed

Buddha's finger bone relic have fuelled public curiosity and scholarly

interest. A curious mixture of fact, claim, and leap of faith drives

this interest. No scientific testing has been done on the "genuine"

finger bone, presumably to respect religious decorum and sensitivity.

Meanwhile, the claim of the singular, "genuine" finger bone versus the three

other simulated finger bone relics, all found in the crypt, remains an article

of faith.1 To the public, the mystique of the relics trumps any interest in the

richly decorated reliquaries that housed them. While this is to be expected,

it is regrettable that the scholarly community has not done nearly enough to

convey to the public the significance of the reliquaries. Moreover, detailed

explications of the Esoteric Buddhist imagery in the Famen Temple crypt

have kept general readers at bay, intellectual curiosity notwithstanding. The

prevalent tenor of scholarly study has largely treated the reliquaries as visual

illustrations of arcane Esoteric Buddhist doctrine.2 Most explanations of the

Famen Temple crypt fail to be ultimately satisfying mainly because things do

not add up in these proposed schemes. The truth of the matter is that the

decorative patterns on these reliquaries and their disposition in the crypt are

a kind of medley—a mixture of several systems and impulses. For example,

both Esoteric and non-Esoteric Buddhist elements are present. None of the

existing Buddhist doctrinal systems explains the governing principle of the

Famen Temple crypt.

So, where does this leave us? We need, first of all, to be clear about

the goal of the relic-centred programme—what was the arrangement of

specific objects designed to accomplish? It had nothing to do with educating

a Tang audience about Buddhist doctrine, through lining up the reliquaries as

Detail of Cat. 20 though they were exhibition pieces. Abundant evidence in die crypt suggests

51

that the relic enshrinement of 874 was a singular feat of engineering, in both

political and biotechnological senses. It was also a feat of artistic engineering,

as evident in the artful manipulation of artefacts. Politically, the transportation

of the relic (a process known as translation) from the Famen Temple to the

palace at Chang'an was carefully staged as part of an imperial succession

drama. Biotechnologically, it was a remarkable instance of a meticulously

programmed regimen hoping to symbolically transform the dying

emperor's body into a new state of being. The body politic and the bodily

transformation were therefore central to this relic-enshrinement scenario.

In the final year of his life, Emperor Yizong (833—873) decreed that the

Buddha relic found at the Famen Temple be brought to the capital Chang'an.

This was a controversial decision which met with strong objections from

court officials. There were numerous reasons underlying their opposition.

The cult of the Buddha relic had never sat well with the scholar-officials

of the court, who tended to regard the practice as mindless and expensive

hype. On the other hand, the eunuchs, whose political clout had increased

exponentially in the ninth century, were staunch supporters for the practice.

The tendency of the eunuchs to use relic translation as political engineering

deepened the court officials' suspicions. But the emperor had the final say:

"if I could see [the relic], I would die without regret!"3 This turned out to be

an ominous statement.

The translation of the relic from Famen Temple to the palace at

Chang'an was the last of six imperially sponsored ceremonial events in the

Tang dynasty (see Chronology p. 25-). The mass hysteria surrounding each of

the processions is well documented. Some frenzied spectators even mutilated

their bodies in the passionate excitement. Why did the relic translation arouse

so much passion?

The Buddhist cult of relics is patently ironic. It contradicts the core

teaching of renouncing the body in search of nirvana—the permanent

delivery from suffering rooted in the body-created desire. Relics, on the other

hand, provided a physical link to the presence of Buddha for the Chinese

community. Some aspects of the Chinese relic cult are particularly notable.

One is the changing disposition of, or properties attributed to, relics. In

early accounts, relics are indeterminate in physical attributes.They oscillate

between sheer optical phenomena hard to pin down, and hard crystalline

things of wonder that withstand repeated hammering. As time went on, the

perceived materiality took on more distinct decipherable properties, to the

extent that Buddha relics were identified as distinct body parts. The Famen

Temple relics therefore emerged as finger bones.

5 2 T H E E M P E R O R ' S N E W B O D Y

Another reorientation is the periodic display and veneration of the

relic. The mystique of the Famen Temple finger bones derives in part from

the lore of the regular opening of the pagoda crypt every thirty years. This

predictable cycle is analogous to a planet's periodic appearance in the sky.

This was a fiction that Tang monks had created. However, once it took shape,

the lore acquired an objective veneer. The periodic reopening of the crypt

lent an aura of both rarity and inevitability to the occasion. It was as if some

immutable natural law ran its course and dictated its own rhythm governing

human affairs. The scheme created a symbolic transcendent authority that

struck awe in the heart even of the emperors and empresses. The mythic

periodicity gave leverage to monks and other Buddhist associates in the body

politic to work the clock, so to speak.

One confounding fact is that the approximate thirty-year cycle of the

relic ceremony coincided with the death of the emperors involved. Nearly

every time the relic was brought to the imperial palace, the sponsoring ruler

died shortly afterwards. The frail Empress Wu Zetian brought the relic to the

palace in 704 and died the following year; in 710, two years after the re-

enshrinement, Emperor Zhongzong was poisoned by Empress Wei. Two years

after the relic translation in 760, Emperor Suzong died. In 819, the relic was

again brought to the palace and the following year Emperor Xianzong died.

And Emperor Yizong died in 873 while the relic was in the palace.

The parade of the relics to and from the capital city was often

tantamount to a rehearsal of a state funeral. Some explanation for this comes

from the fact that sickly emperors tended to seek all the more eagerly the

miraculous cure and therapeutic efficacies associated with relics. These

coincidences also suggest the darker possibilities of behind-the-scenes palace

coups or engineered successions stage-managed by die eunuchs of the

inner palace.

While the relic translations of several Tang emperors left their traces

in the Famen Temple crypt, the last one staged by Emperor Yizong, or rather,

by his inner-court eunuchs, accounts for the disposition of the artefacts

as discovered in 1987. The nine hundred or so objects left in the crypt

were given in someone's name. Moreover, the placement of objects in the

innermost chamber shows a clear design concept, unmistakably pointing to

the careful engineering by Yizong's handlers.

E U C E N E Y . W A N C 5 3

Who were these people? Current accounts regard Emperor Yizong as

the ultimate force powering the events and circumstances surrounding the

last relic ceremony. However, careful analysis of the crypt's inventory tablet

goes at least some way toward undermining this view. Here is the breakdown

of objects by donor:

Gifts from the Chongzhen Monastery (that is, from Famen Temple):

7 items

Gifts from Emperor Yizong after the relic reached the Inner Palace:

122 items (including the eight caskets)

Gifts newly given by Emperor Xizong (upon the return of the relic to

the monastery): 754 items

Gifts from Empress Dowager Hui'an (Yizong's consort and Xizong's

mother) and Lady Zhaoyi, and from Lady Jinguo: 7 items

Gifts from various "heads" (eunuchs, monks, and nuns): 9 items

Gifts from Zhihuilun of the Daxingshan monastery: a items4

The most striking thing about this litany of gift-giving is how utterly

improbable it is. To begin with, Empress Dowager Hui'an (d. 866) had died

years ago, and this was a widely known fact. How could she have "given"

anything at all? The gifts were apparently presented in her name. The majority

of the gifts were presented by Emperor Xizong (862-888), who was merely

a twelve-year-old at the time of his succession to the throne. The Emperor

Yizong's fifth son, he was not supposed to inherit the throne, as his four

older brothers were apparently ready and more legitimate to succeed.

Moreover, the imperial hereditary system should have lined up the eldest son,

the heir apparent, to succeed the dying emperor. Installing a twelve-year-old

and leapfrogging four older princes bears the indelible imprint of political

engineering by the eunuchs. They undoubtedly wanted to wield power by

controlling the young emperor. The youngster was their best bet and the

easiest puppet to manipulate. We may conclude that the eunuchs were the

real agency behind the 7^4 items given in Xizong's name. The timeline is

correct: these were given after the relic had been returned to Famen Temple.

The most astounding items were the 122 objects given by Emperor

Yizong after the Famensi finger bone relic (or relics) had reached the

5 4 T H E E M P E R O R S N E W B O D Y

The eightfold reliquary from therear chamber of the Farnen Templecrypt. Famen Temple Museum

inner palace. Most prominent among these was the set of eight nesting

caskets enshrining one of the Buddha's finger bones (fig. 2). The decorative

programme, as has been demonstrated elsewhere, maps out the entire

process of the emperor's bodily transformation into a postmortem and post-

human condition.1 How can that be? There is no way the all-powerful—or

was he?—emperor would have allowed the design of the decorative

programme to be about his own death. Even if he were in full control, the

relic enshrinement would have been in part a symbolic regimen to cure

his worsening illness. We are left to ponder a darker and murkier scenario.

The emperor was sick and his death was expected. The relic was in the

inner palace. A scheme was laid out for a succession plan. The decision was

made that a teenage prince should succeed the throne, rather than his adult

brothers. These behind-the-scenes maneuvers are largely absent in the extant

historical texts, and there is no way of knowing what exactly happened.

The eightfold set of nesting caskets lays out the scheme. Simply put, the

reliquary set is, inadvertently, the most revealing visual documentation of

a programmed throne succession scheme in Chinese history. However, it

is veiled in a visual language heavily dependent on codes derived from the

Buddhist symbolic idiom.

Deciphering this idiom is key to understanding the reliquary sets and,

by extension, the layout of artefacts in the crypt. Some roadblocks need to

be cleared to navigate this complex system. As mentioned earlier, scholars

have largely subscribed to the premise that the reliquaries are derived from

Esoteric Buddhist doctrine. However, this premise does not work. Luo Zhao,

E U G E N E Y . W A N G 55

one of the few dissenting voices, long ago pointed to an obvious fact that

most scholars choose not to deal with: the two sets of reliquaries in the rear

chamber are medleys of Esoteric and non-Esoteric iconographic systems.6

Just because the two sets of codes are mixed does not mean they cannot

work together. They can, but not as a purely Esoteric system. We need to bear

in mind that the programme resulting from this mixture of codes served

a purpose that did not solely illustrate doctrine of either of the Buddhist

systems. Streamlining a bodily transformation is the key agenda underlying

the two reliquary sets in the rear chamber.

Why are we so fixated on the rear chamber? Indeed, the crypt

consisted of more than just this innermost space. In fact, in this three-

chamber catacomb, all three spaces contained a reliquary structure. Each

enshrined a Buddha relic—albeit the "simulation" finger bones as opposed

to the supposedly real one uncovered from the compartment below the

rear chamber. The reliquaries from the first two rooms are products of

earlier times. The painted marble reliquary stupa from the first room (the

"Ashoka Stupa", fig. p. 13) shows considerable signs of wear and seems to

have been restored at the time of the last enshrinement in 874, and was

thus already of considerable age. The large marble reliquary from the middle

chamber (fig. p. 13) dates from around 708 and bears the name of the monk

Fazang (643-712). It is difficult to reconstruct the original positions and

programmatic roles of these two earlier reliquaries; the last relic translation

of 874 may have displaced or rearranged the earlier objects to the extent that

their original intent cannot be surmised with certainty. The rear chamber

is altogether a different story. Its arrangement had a discernible pattern that

is still intelligible. Even though the enshrinement plan incorporated some

earlier artefacts—for example, the miniature crystal coffin in the fivefold

reliquary set—the assemblage bore the indelible fingerprint of the 784 relic

translation, and the design of its programme can thus be deduced.

Once again, some conceptual roadblocks need to be cleared before

we proceed to reverse-engineer the reliquary enshrinement programme.

The bulk of current thinking on Famen Temple hinges on the Esoteric

Buddhist elements, in particular, some unmistakable mandala iconography.

It is thus assumed that liturgical activities must have taken place there, since

the mandala is known to fulfill Buddhist ritual functions. Worse still, these

artefacts are assumed to be meaningful or intelligible only in relation to those

presumed mandala-derived ritual performances. In fact, nothing could be

wider of the mark. As Luo Zhao rightly pointed out two decades ago, the rear

chamber hardly allows an average person to stand erect, let alone facilitate

liturgical functions.' In refuting the rear-chamber-as-mandala premise,

5 6 T H E E M P E R O R ' S N E W B O D Y

The fivefold reliquary from the hiddencompartment beneath the back wallof the rear chamber (the third casketmade of sandalwood is not shown).Famen Temple Museum

however, Luo was trapped: either the rear chamber is a mandala arena hosting

perfection-of-body rituals, or it is not a mandala arena, since it cannot

physically accommodate ritual performance, and because the assemblage of

artefacts here contained pieces decidedly unrelated to mandala iconography.

This either/or quagmire stems from the widely shared but misguided

assumption that the functionality of these artefacts was tied only to human-

performed rituals; and if rituals were involved, they were conceived only

in a doctrinally correct framework in view of the relic enshrinement. The

indelible imprint of the historical circumstances on the artefacts strongly

suggests an ad hoc approach. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that a

symbolic staging, at a miniaturized level, of the postmortem process of bodily

transformation was the real agenda. The mandala, itself a heightened symbolic

form of enabling bodily dissolution and symbolic merging with Buddhahood,

was pressed into service as part of this process. Indeed, mandalas were

present in the Famen Temple crypt, but they were there to serve the simulated

or modelled process of bodily transformation, not the other way round. And

the artefacts in the crypt "performed" this ritual.

There were two reliquary sets in the rear chamber. The eightfold set

was centred on the back wall of the chamber. The fivefold set (fig. 3) was

interred in a so-called "secret niche", that is, a compartment underneath the

floor (see fig. p. 16). At first, this appears puzzling. The chamber itself was

already part of the underground catacomb. Why should the subterranean

chamber contain further division between aboveground and underground

spaces? This division is in fact crucial to the symbolic division of labours

E U G E N E V . W A N G 5 7

assigned to the artefacts. Consider the eightfold reliquary set on the floor

(fig. 2). The nesting boxes, as will be shown, formed a succession of fictive

spaces. The succession implies an outside-in movement, culminating in a

gold container shaped in the form of a stupa-tower. The fivefold reliquary

placed underneath the floor likewise formed a succession of symbolic

spaces, suggesting an outside-in movement (fig. 3). Its innermost container

is a miniature jade coffin holding the so-called "genuine" finger bone relic

(Cat. 2i).The contrast of the two distinct endpoints is striking. The logical

cogency is compelling. The stupa-tower of the aboveground set points upward

or heavenward. The coffin is expected to be underground, or, in medieval

Chinese parlance, in the realm of the Yellow Spring.

This two-tiered arrangement itself indicates an unmistakable burial

scenario, albeit on a scale of symbolic simulation. The source codes of

this symbolic burial draw heavily on Buddhist symbolic systems. This fact

often predisposes us toward seeing the whole setup primarily as a Buddhist

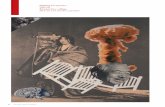

4 programme. However, nowhere in the Tang Buddhist ritual canon do we everWooden figures (front and back views) r n . . n. r n , , ^ .placed next to the crystal coffin in the find instructions regarding ways of mixing a mandala and a coffin into a singlesandaiwood casket. From the fivefold programme. If we accept the premise that engineering and modelling thereliquary in the hidden compartment

postmortem bodily transformation is the central storyline here, things start to

add-up or fall into place. In fact, prescribing the proper way of caring for the

dead, the seventh-century Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia Treasure Trove of the

Dharma World is explicit about the binary nature of postmortem condition.

Its compiler, a monk named Daoshi, draws on received classical Chinese texts

of the pre-Buddhist era. An individual person's postmortem condition is

thus divided into two entities, heading respectively to heaven and earth. The

ethereal intelligent breath (him z$|) flies in space, while its earthly counterpart,

the animal breath (po ftt), is stuck with the corpse to be buried underground.8

The two-tiered division appears to be the governing principle in the Famensi

rear chamber. The eightfold set guides the ethereal spirit in its aerial flight; the

fivefold set takes care of the body in its subterranean environs.

A crucial piece of evidence bolsters this hypothesis. The third container

of the subterranean fivefold reliquary is a sandaiwood case that holds the

crystal coffin which in turn contains the jade coffin. This sandaiwood

box contained a most intriguing scene: ten miniature figures carved of

wood—merely 3 to 4 centimetres or so in height—attend the crystal coffin.

While at least four of them are apparently bodhisattvas and heavenly guardians,

others are lay figurines decidedly unrelated to Buddhist iconographic schemes

(fig. 4). Virtually unprecedented in the entire history of Buddhist reliquary

enshrinements, these lay figurines are an embarrassment to scholars trying

to subsume everything under the mandala program of the fivefold reliquary.

5 8 T H E E M P E R O R ' S N E W B O D Y

Fragment of the sandalwood casket in theeightfold reliquary: screen and cartouche.Famen Temple Museum

Fragment of the sandalwood casket inthe eightfold reliquary: regal figure.Famen Temple Museum

As they cannot explain these figures, nearly all the studies of the Famen

Temple cache choose not to deal with them.9 Deliberately distinct from the

mimetically modeled bodhisattvas and heavenly guardians, these figures are

minimally carved cylindrical blocks of wood. To students of traditional Chinese

funerary art, however, these figurines are entirely familiar. They belong to

the tradition of tomb figurines that populate burial spaces in order to replace

live human sacrifices. Their un-mimetic and geometric appearance was

intended to convey their status as "spiritual articles" so as to reinforce their

subterraneous identities. These lay figurines reinforce the situational logic of

the subterraneous fivefold reliquary. They decidedly evoke a funerary burial.

The theory of the dual division alone, however, does not explain

all aspects of the two reliquary sets. We need to observe how the design

creatively appropriates Buddhist iconographic conventions for its purpose.

The eightfold set of nesting boxes apparently spell out a sequence of changing

states. The question is whether the sequence proceeds from outside in or

inside out. The inventory stele lists the set of eight boxes by naming the

innermost box as the "first fold," and pushes outward.10 There is no reason

to believe that the inventory's matter-of-fact enumerative disposition has

any close connection to the iconographic programming. Recent exhibition

catalogues rightly reverse the order by counting the boxes from outside in."

This orientation harmonizes with the force of the decorative programme.

E U G E N E Y , W A N C 5 9

The set begins with a sandalwood box, now extant only in fragments.

The pictorial content can still be inferred by a few surviving pieces. One

fragment was originally the section above a presiding Amitabha Buddha

of die Western Paradise (fig. 5), as it shows a screen in front of which the

Amitabha Buddha would be installed, a halo, and a cartouche that reads:

"Amitabha of the Western Land of Bliss." Another piece of the box shows a

haloed and crowned regal figure in Chinese courtly robe holding some kind

of offering plate, accompanied by what appear to be a royal consort and a

junior (fig. 6). The regal figure is very likely Emperor Yizong, escorted by

his consort and the fifth son, soon to succeed him as Emperor Xizong. The

historical circumstances surrounding die relic enshrinement of 874 support

this conjecture.

Planning for the relic translation started in 871. However, the official

ceremony of welcoming the relics into the capital city did not take place until

two years later, when in the fourth month of 873, the relics were welcomed

into the imperial palace.12 In the seventh month of die same year, the emperor

died. His successor, Xizong, was enthroned "right in front of the coffin." Five

months later, the relics were returned to the Famen Temple crypt, which

remained sealed for a millennium.

The symbiosis of the relic re-enshrinement ceremonies and Emperor

Yizong's birthday/death is striking. It highlights the elusiveness and elasticity

of the term "True Body," a period term for the Buddha's relics. The relic

re-enshrinement, tied to the emperor's health and death, made plain the

conflation of the bodies of the Buddha and the dying emperor. This is almost

explicit in the stele composed by the prominent monk Sengche of the Anguo

Monastery,'3 and placed along widi the inventory stele at the front door of the

front chamber in 874.'4 The text traces the history of relic translations under

Tang imperial patronage. In particular, it documents the entire process of

the final welcoming of the relic into die capital and its return to the Famen

Temple. Sengche's narration is revealing. It abruptly shifts from the emperor's

ebullience over the relic's arrival to his death. After gushing over the

emperor's excitement roused by the sight of the relic, the text careens to the

sobering matter of the emperor's death in tactful phrases couched in ethereal

terms: "Suddenly growing tired of the worldly affairs, [die emperor] was bent

for transcending the Ten Regions. He departed for good, heading toward the

Nine Lotuses; stepping on the Five Clouds, he will never return. The Dragon

Chart has been bequeathed to the Bright Ruler, and the Phoenix Pedigree will

be continued by the filial branch." 'J

Having narrated both the welcoming of the relic and the emperor's

death, the author then described the return of die "True Body" to Famen

6 0 T H E E M P E R O R S N E W B O D Y

Vaisravana riding across the waters,mid-10th century. Painting from cave 17,Mogao, near Dunhuang, 61.8 x 57.4 cm.British Museum, London

Front face of fig. 9: Heavenly Kingof the North

Temple. At this juncture, it is no longer possible to distinguish between the

ritual lamentation over Shakyamuni's entry into nirvana and the mourning

for the deceased emperor: "The cloud sprinkled flowers from the Treasure

Realms, which were teardrops sprayed from the celestial river." As the relic

was interred in the crypt, it struck Sengche that "the imperial family's

bountiful blessedness is boundless, and Virtuous Seed [embodied in the relic]

that had endured extensive kalpus [cycles of creation and destruction] defies

decay." The votive text ends in the vein of a funerary memorial:

The whole Dhyana River is drenched in tears, the Bodhi Trees are

shivering with sadness ... The temple chimes reverberate in sync.

At the thought that the golden gate is to be closed forever, [one is]

overwhelmed by ten thousand kinds of pathos. Knowing the Excellent

Body will last for eternity, [one is able to] take some consolation.

The Meeting with [Maitreya and] the Three Groups under the Dragon

Flower Trees gathers all those who are there to see the Buddha; the

[Pure Land of] fragrant Nine Lotuses greets those who transcend life

and death.'6

It is hard to imagine any sensible reader of this text still holding on to

the strict equation of the "True Body" and the Buddha relic. The description

is a perfect caption for the outermost sandalwood box. Here is the emperor

heading to Amitabha's Pure Land. The cast of characters is a careful

assemblage: there is his consort, probably Empress Hui'an, already dead;

and his son, soon to be installed as his successor Emperor Xizong. The key

dynamic is the father-son relationship, which continues onto the next casket.

On the gilded silver casket (fig. 9), the relief compositions on the four

faces make sense only in relation to set iconographic conventions. The Four

Heavenly Kings, respectively, occupy the four faces. Their presence suggests

a particular altitude. The Four Heavenly Kings occupy the upper level of

the Realm of Desire, the lowest of three realms that comprise the Buddhist

cosmos. This means that the imaginary flight to the upper level starts with

this fourfold cast poised at the border. They thus shoulder the border-crossing

task. Vaisravana, the Northern Heavenly King, is singled out for the symbolic

border-crossing mission, since north is associated with winter, water, cold,

and death in the traditional Chinese cosmological scheme. Ninth-century

pictorial conventions typically feature Vaisravana holding a human-palm-sized

stupa-tower across the oceanic boundary and ascending to a higher plateau

(% 7).

E U G E N E Y . W A N G 61

LEFT TO R I G H T , FROM TOP

9Front face of gilded silver casket,from the eightfold reliquary in therear chamber, by 874. Gilded silver,height 23.5 cm. Famen Temple Museum

10Side of fig. 9: Heavenly King of the East

Side of fig. 9: Heavenly King of the West

12Back face of fig. 9: Heavenly King ofthe South

The iconographic twist here is suggestive. Technically, the miniature

stupa-tower is a reliquary. This is confirmed by the presence of the batman-

like demon in such reliquary scenes. This figure is given to stealing the

Buddha's relic. The archer inVaisravana's entourage makes sure that the relic

thief is kept away from the relic. Here is a twist. The miniature reliquary

contains a whole body instead of a body part. The bodily form amounts to the

imagined postmortem humanoid spirit.'7

The front-face relief on the gilded silver casket recapitulates these

elements (fig. 8). The archer takes aim at the fleeing batman-like relic stealer.

Vaisravana holds the stupa-tower reliquary on his left hand. To reinforce

the point that this is a relic-centred scene, the composition includes a few

other features. Two cherubic figures in the lower corners hover over jars and

present relic-like jewels to Vaisravana. This is derived from the Division-of-

Relics convention current in Tang times. Relics are typically contained in a jar

and then distributed among the delegates who claim their equal share of the

relics (see discussion in Cat. 63).

The relief here makes its point through its heavy-handed variation

from the two conventions sketched above. One convention involves the relic-

escorting Vaisravana crossing the boundary from one realm to another. The

other is the division of relics among neighbour-state delegates. These two

conventions normally do not mix, but the casket conflates them. Moreover,

the Northern Heavenly King monopolizes the relic to the exclusion of

others. Equal and fair distribution of relics is out of the question here. Unlike

other images of the Four Heavenly Kings, here the primacy of the Northern

Heavenly King is total and uncompromising. He and his entourage occupy the

privileged front of the casket, and the assembly is presented symmetrically

with a frontal view. The other three Heavenly Kings are presented in a three-

quarter view, facing left, reduced to subservient status.

The real protagonist central to our storyline is not the seemingly

commanding Northern Heavenly King, but the figure in Chinese-style robes

standing to his left. Each of the four assemblies on the casket features a lay

ruler in foreign-style garment. Here is a curious fact. The sartorial styles

of the lay rulers associated with the west, south, and east are all of foreign

kings (figs. 10, n, 12). Since they are part of the entourages of the left-

facing Heavenly Kings, they are apparently of lower status, yet they all appear

taller in stature than their Chinese counterpart on the front. Moreover,

each of them has a female consort. The Chinese ruler does not. There is

no way that the design would downplay the Chinese ruler's importance in

this constructed universe. It turns out size matters in this context, not in

terms of importance, but in registering the circumstances of the moment.

6 2 T H E E M P E R O R S N E W B O D Y

When Xizong was installed as emperor, he was only twelve and still unwed.

This explains his shorter stature on the front-face relief and the absence

of a consort. Moreover, he displays a jewel-like object on his right hand,

apparently a reference to the Buddha relic. Jewels were habitually perceived

as relics. Given the Division-of-Relics convention, the relief suggests the

young emperor's monopoly of the "True Body." This is as the memorial

tablet would have it: "The Dragon Chart has been bequeathed to the Bright

Ruler, and the Phoenix Pedigree will be continued by the filial branch." '8 The

relief is essentially about the succession of 873. The elusive high-order "True

Body" links the dead Emperor Yizong and newly installed Emperor Xizong.

Meanwhile, the old body needs to go through its postmortem motions. The

stupa-tower-holding Northern Heavenly King makes sure that the "body" is

transported to the other realm.

This scenario may draw on a much-circulated sutra. The text recalls

Buddha Amitabha's life coming to an "end." Even he entered nirvana.'9 It

also presents two "young boys" named Baoyi and Baoshang. They blithely

announce, in Gatha, that "the dharma of the past has been extinguished;

and that of the future is yet to come," and that everything in this world of

delusions and emptiness amounts to an improvised "fictive device."20 All this

resonates well with the situation of the twelve-year-old soon to be installed

as Emperor Xizong. It may also explain why the outermost casket features the

crowned figure—Amitabha in the sutra and Emperor Yizong in real life—in

the Western "Land of Bliss." Inhabitants of that distant land are said to look at

our world as if they view the "dmalaka fruit in their hand." They see the Four

Heavenly Kings in the assembly of Shakyamuni Buddha, a scene depicted in

the next casket in line.

The key concept that governs the design of the overall scheme of the

casket sets is the Wish-Granting Jewel. The balls presented by the two boys

could be visual iterations of this jewel. The jewel-themed design becomes

more salient when the programme progresses to the fifth casket. For now,

suffice it to say that the Wish-Granting Jewel is the organizing concept

governing disparate relic-related imaginary scenarios featured on the caskets.

It is derived from the notion of pdramita, a Sanskrit term meaning at once

"crossing over to the other shore" and "perfection." 2I While Indian texts

hesitate between these two senses, the Chinese embraced both. Accordingly,

the "Wish-Granting Jewel" is an illustrative visual trope to encompass these

two senses. The sense of "perfection" means that no physical object can fully

capture the all-encompassing quality of the Wish-Granting Jewel. A human-

engineered composite simulation is a second best solution, mixing "Buddha

relic, gold, silver, Aloe wood, white sandalwood, purple sandalwood, fragrant

6 4 T H E E M P E R O R ' S N E W B O D Y

peachwood ... lacquer."22To the extent that it is a conceptual object, physical

objects — seashore pebbles, etc.—may serve as surrogates. The sense of

"crossing over to the other shore," on the other hand, evokes a range of

domains, in particular, the distant Buddhaland of bliss. The optical property

of the magical jewel means unlimited freedom in displaying visionary vistas

encompassing the subterraneous depth to die "dragon palace in the sky."

The encasement design, therefore, gives form to these realms and

processes. It encompasses "dragon palaces" both in the deep sea and in the

sky. The two sets of caskets suggesting, respectively, the "below" and "above",

are in sync with this scheme. Meanwhile, the design also encompasses myriad

material realms and textures: "First, the refined-iron colour; then, the gold

and red-hued white of silver." According to the scriptural design scenario, the

multilayered encasement of the Wish-Granting Jewel amounts to as many as

one-hundred-eighteen-fold textures and realms, signifying "nine surrounding

mountains and seas within the circling Iron Mountains".23 This explains why

the unadorned silver casket in the eightfold casket set is strikingly different

from all the adorned boxes in the series (fig. 2). It evokes the Iron Mountains

that enclose the Buddhist cosmos, marking the boundary that sets the inner

and outer realms.

This design scheme sets the stage for the "crossing over to the other

shore." More specifically, it comes down to a set of transformations. There is,

according to scriptural plans, a more literal scenario of boundary-crossing.

The fourth casket is a notable stage of this scenario. The reliefs on the two

sides of the casket (figs. 13, 14) feature the elephant-riding Samantabhadra

and lion-riding Manjushri, ready to meet on the front face. Their appearance

typically signals the arrival of delegations from the Buddhaland to fetch and

escort the deceased's spirit to the Buddhaland. The pair thus commonly

appears on walls flanking the entrance to a Buddhist inner sanctuary, thereby

signalling the transportation of the earthbound beings into a higher realm.

Here they escort Emperor Yizong's postmortem spirit, recognizable through

his crown and imperial robe, on the way to the Buddha's assembly. The

Buddha occupying the casket's front face is probably Shakyamuni, preaching

before passing into nirvana (fig. 15). The temporal framework therefore is set

in the present kalpa (a cycle of creation and destruction of the universe). The

Buddha assembly on the rear side of die casket signals the future (fig. i6).The

Buddha's tall topknot and regal robe identify him as Maitreya in front of the

Dragon-Flower trees and the palatial structure evoking theTushita Heaven.24

The casket thus suggests a front-to-back, or present-to-future, movement.

Emperor Yizong's footsteps can be followed through this nesting set

of virtual galleries. The next in line, the fifth casket, is a crucial stage in this

E U C E N E Y . W A N C 6 5

LEFT TO R I G H T , FROM TOP

13

Side of the fourth casket of theeightfold reliquary, by 874. Gildedsilver, height 16.2 cm. Famen TempleMuseum

14

Side of the fourth casket of theeightfold reliquary

15Front face of the fourth casket of theeightfold reliquary

16

Back face of the fourth casket of theeightfold reliquary

modelled process of postmortem transformation. It is the last casket with

figural motifs in the outside-in series. That the termination of the figuration

coincides with the disappearance of Emperor Yizong's avatar is notable.

Indeed, previous caskets' reiterations of the emperor raise the expectation

of more recapitulations to come. But the run stops here, and the imperial

figure is no longer present. Or so it seems. In fact, it is precisely at this

juncture that our central storyline—Emperor Yizong's postmortem bodily

transformation —reaches its climactic moment.

Again, the Wish-Granting Jewel remains the organizing concept.

The front face suggestively features a Wish-Granting Jewel Sound-Observer.

On the opposite end is Mahavairocana. The two faces spell out two states

compromising the ritual process ordered by the Wish-Granting Jewel, namely,

bodily transformation. Through ritual performance, the subject—whether

it is the Shakyamuni Buddha, a bodhisattva, a devotee, or the postmortem

being—mutates into a different state, shedding his individual, earthbound

body and symbolically merging with the vast domain of Vairocana, or the

Great Sun Buddha. For the living person going through this ritual, the change

is one of symbolic initiation or ordination. For the postmortem spirit, as

in the case of the Emperor Yizong, it means symbolic dissolution of bodily

self and entrance into the Buddha world. To provide testimonial to the

success of this ritual transformation, other Buddhas present to witness the

transformation are said to emanate rays of light. The two side faces of the

casket precisely depict this scenario.

What happens, then, after one leaves the body behind? Buddhist

scenarios posit a heightened state of arrival at the "lotus dais" of the Western

Land of Bliss. Bejewelled floral designs are typical devices evoking this beryl,

or lapis lazuli, domain. The sixth and seventh casket designs register thisl ' o o

exalted state of affairs. The innermost container, in the shape of a stupa-tower,

allegedly enshrines a Buddha finger bone relic. It signals this state as in an

aerial height, in opposition to the coffin-centred relic enshrinement under

the rear chamber floor.

The two sets of caskets are inextricably related. In general doctrinal

terms of Buddhist practice, meditation goes hand in hand with the change

in the meditator's bodily state. Shedding one's mortal body and fusing with

Mahavairocana's domain is in sync with acquiring a vision. The arrival at

the "lotus dais" high up there is a prerequisite condition. Having attained a

liberated state, one looks down from that vantage point on the earthly domain

below. The abandoning of the mortal body, a disembodied meditative stance,

results in the "permanent diamond-like samadhi", or adamantine absorption.

The adamantine stance corresponds to the hardened state of the diamond

world below.25

E U G E N E Y . W A N C 67

17Kneeling bodhisattva holding a tray forthe display of the relic, dated 871.Gilded silver and pearls, height 38.5 cm.Famen Temple Museum

In view of the particular historical circumstances, this esoteric above/

below scheme amounts to no more than a more exalted way of explaining

what essentially is a burial situation, albeit a symbolic one. It could be another

way of framing the traditional Chinese conception of binary postmortem

condition. The disembodied intelligent spirit (hun) flies high; and the bodily

remains (po) stays underground. Two casket sets thereby accommodate both.

Other objects in the rear chamber are largely accessory pieces to the

central ritual drama the two casket sets embody. The four identical arghya

pitchers (Cat. 19) placed in the four corners of the rear chamber are props

used in the abhisheku ritual, a ceremonial consecration involving sprinkling

water on a person to confer a changed status. Derived from an Indian

practice of baptism, abhisheka was an Esoteric Buddhist rite of initiation which

gained currency in China in the eighth century. Through the ritual, a person

undergoes initiation, symbolically transcends his parents-begotten body,

and merges with the Mahavairocana. The standard account often posits a

bodhisattva going through stages culminating in "becoming" a Buddha body.

The decoration of the fifth casket stages this process. The pitchers are part of

this symbolic regimen.

One thing becomes clear from the above. Mapping a progression into

a series of gallery-like spaces from outside in, the two reliquary casket sets

in fact spell out a succession of changing bodily states. A statue made in 871,

on the occasion of Emperor Yizong's thirty-ninth birthday, says much about

this body/space conflation (fig. 17).26 This work consists of a three-tiered

base supporting a half-kneeling figure holding a plate. The votive inscription

on the plate states, in essence, that the bodhisattva statue presenting the True

Body (that is, the Buddha relic) was made for the emperor on his birthday.

The sculpture is inscribed with the wish that "His Highness Lives for Ten

Thousand Springs, and that Ten Thousand Leaves blossom from His Pedigree

Tree. The barbarians of the eight quarters submit themselves to his rule, and

the Four Seas remain calm."

The sculpture was a fitting gift for Yizong's birthday. The figure derives

from Lakshmi, the life-giving Indian mother-goddess of fortune and beauty.

The elaborate coiffure suggests femininity.27 Two notable attributes establish

her identity. The interior surface of the base features the oceanic domain

teeming with swirling dragons, and the figure holds a lotus-leaf-shaped

plate.28 These traits recall Lakshmi's coming into being: she once sprang from

the sea holding a lotus in hand.

The design on the three-tiered stand further develops the themes

of life-giving and growth. Modelled after Mount Sumeru, the axis mundi of

the Buddhist cosmos, the surface of the stand is covered with flame or lotus

T H E E M P E R O R S N E W B O D Y

18

Figure of Mahavairocana3 placed atop theeightfold reliquary in the rear chamber;by 874. Partly gilded silver, height 15 cm.Famen Temple Museum

petal frames, featuring constituent figures of Mahavairocana's vast domain

(that is, luminous kings and a variety of bodhisattvas). The design suggests

mandala compositions.19 The mandala, however, was not there to illustrate

Esoteric doctrine. Rather, the spatial form maps evolving bodily states. The

Indie Siddham-script syllables arranged circularly and inscribed on top of the

three-tiered stand begin with the primary formula of the True Word: a, vam,

ram, ham, kharn.30 The five syllables correspond to five elements (earth, water,

fire, wind, and air) that comprise the substance of Mahavairocana. Following

the traditional Chinese disposition to correlate natural elements with body

parts, Tang monks accordingly matched these Indie letters — and their range

of references—to the five organs. A was thus made to stand for liver, yam for

lung, ram for heart, ham for kidney, kham for spleen (or stomach).3' The same

body/space correlation scheme also allowed Tang monks to conceptualize

Mahavairocana's cosmos by way of the human body. The mandala structured

around the fivefold formula thus became a neatly ordered corporeal schema.

Likewise, the Buddhist striving for the three kinds of "consummation" (siddhi)

conveniently lends itself to a three-tiered mapping of the human body in a

Chinese apocryphal Buddhist sutra.31 This body/space modelling apparently

informs the design of the relic-holding statue. The artefact was a physical

prayer for the -well-being of the emperor's ailing body.

Contrary to these hopes, EmperorYizong did not last long. It is all

too revealing that the wistful statue made for the emperor's birthday was left

outside the door to the rear chamber. This decision presumably stems from

some kind of awareness of the irony it engendered. In its stead, another statue

(fig. 18) was made and pointedly placed on top of the eightfold reliquary

casket. The gilded figure of Mahavairocana sits atop a three-tiered stand,

much like its counterpart outside the rear chamber (fig. 17). Keeping in mind

the body/space correlation, it is not too hard to sense what it is all about.

Emperor Yizong has left behind his parents-begotten body, a state signified

by the mother-goddess-inspired statue left outside the rear chamber. His

disembodied spirit has merged into Mahavairocana's vast cosmos that spans

heaven and earth, which the eightfold and fivefold casket series respectively

signal. If Mahavairocana does have a "body," it is pure space. The Tang

mourners could thus take some consolation, knowing that "Excellent Body

will last for eternity."33

E U G E N E Y . W A N C

Objects found in the rear chamber of

the Famen Temple crypt (upper layer)

From the top:

040, 084: Arghya water pitchers (Cat. 19)111, 110: Guardian figures

030: Bodhisattva atop the eightfold reliquary043: Basin with mandarin ducks (Cat. 12)

001: Bottle (Cat. 3)

075: Incense burner with stand (Cat. 16)

089: Hand warmer (Cat. 13)

069: Soup bowl (Cat. 5)

074: Box with lions (Cat. 4)

70 C A T A L O G U E , P A R T 1

25cm

Objects found in the rear chamber of

the Famen Temple crypt (lower layer)

From the top:

011-1-8: Eightfold reliquary casket

077: Basket with flying geese (Cat. 8)

076: Turtle-shaped container (Cat. 9)

095, 096: Tea grinder (Cat. 7)

017, 083:Arghya water pitchers (Cat. 19)

T H E F A M E N T E M P L E C R Y P T 7 1