The Broad Hall of the Two Maats. Spell BD 125 in Karakhamun’s Main Burial Chamber

Transcript of The Broad Hall of the Two Maats. Spell BD 125 in Karakhamun’s Main Burial Chamber

Thebes in the First Millennium BC,

Edited by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka and Kenneth Griffin

This book first published 2014

Cambridge Scholars Publishing

12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright © 2014 by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka, Kenneth Griffin and contributors

All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN (10): 1-4438-5404-2, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5404-7

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword …………………………………………………………………xi Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………...xv Part A: Historical Background Chapter One ……………………………………………………………....3 The Coming of the Kushites and the Identity of Osorkon IV Aidan Dodson Part B: Royal Burials: Thebes and Abydos Chapter Two ……………………………………………………………..15 Royal Burials at Thebes during the First Millennium BC David A. Aston Chapter Three …………………………………………………………....61 Kushites at Abydos: The Royal Family and Beyond Anthony Leahy Part C: Elite Tombs of the Theban Necropolis

Section 1: Preservation and Development of the Theban Necropolis

Chapter Four ………..………………………………………………….101 Lost Tombs of Qurna: Development and Preservation of the Middle Area of the Theban Necropolis Ramadan Ahmed Ali Chapter Five ……………………………………………………………111 New Tombs of the North Asasif Fathy Yaseen Abd el Karim

vi Table of Contents

Section 2: Archaeology and Conservation Chapter Six ……………………………………………………………..121 Kushite Tombs of the South Asasif Necropolis: Conservation, Reconstruction, and Research Elena Pischikova Chapter Seven ………………………………………………………….161 Reconstruction and Conservation of the Tomb of Karakhamun (TT 223) Abdelrazk Mohamed Ali Chapter Eight …………………………………………………………..173 The Forgotten Tomb of Ramose (TT 132) Christian Greco Chapter Nine …………………………………………………………...201 The Tomb of Montuemhat (TT 34) in the Theban Necropolis: A New Approach Louise Gestermann and Farouk Gomaà Chapter Ten ………………………………………………………….....205 The “Funeral Palace” of Padiamenope (TT 33): Tomb, Place of Pilgrimage, and Library. Current research Claude Traunecker Chapter Eleven …………………………………………………………235 Kushite and Saite Period Burials on el-Khokha Gábor Schreiber

Section 3: Religious Texts: Tradition and Innovation Chapter Twelve ………………………………………………………...251 The Book of the Dead from the Western Wall of the Second Pillared Hall in the Tomb of Karakhamun (TT 223) Kenneth Griffin Chapter Thirteen ……………………………………………………….269 The Broad Hall of the Two Maats: Spell BD 125 in Karakhamun’s Main Burial Chamber Miguel Angel Molinero Polo

Table of Contents vii

Chapter Fourteen ……………………………………………………….295 Report on the Work on the Fragments of the “Stundenritual” (Ritual of the Hours of the Day) in TT 223 Erhart Graefe Chapter Fifteen …………………………………………………...…….307 The Amduat and the Book of the Gates in the Tomb of Padiamenope (TT 33): A Work in Progress Isabelle Régen Section 4: Interconnections, Transmission of Patterns and Concepts, and Archaism: Thebes and Beyond Chapter Sixteen ………………………………………………...………323 Between South and North Asasif: The Tomb of Harwa (TT 37) as a “Transitional Monument” Silvia Einaudi Chapter Seventeen ………………………………………………...……343 The So-called “Lichthof” Once More: On the Transmission of Concepts between Tomb and Temple Filip Coppens Chapter Eighteen ……………………………………...………………..357 Some Observations about the Representation of the Neck-sash in Twenty-sixth Dynasty Thebes Aleksandra Hallmann Chapter Nineteen ……………………………………………………….379 All in the Detail: Some Further Observations on “Archaism” and Style in Libyan-Kushite-Saite Egypt Robert G. Morkot Chapter Twenty …………………………………………...……………397 Usurpation and the Erasure of Names during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty Carola Koch

viii Table of Contents Part D: Burial Assemblages and Other Finds in Elite Tombs

Section 1: Coffins Chapter Twenty-one ………………………………………...………….419 The Significance of a Ritual Scene on the Floor Board of Some Coffin Cases in the Twenty-first Dynasty Eltayeb Abbas Chapter Twenty-two …………………………………………….……..439 The Inner Coffin of Tameramun: A Unique Masterpiece of Kushite Iconography from Thebes Simone Musso and Simone Petacchi Chapter Twenty-three ……………………………………………….…453 Sokar-Osiris and the Goddesses: Some Twenty-fifth–Twenty-sixth Dynasty Coffins from Thebes Cynthia May Sheikholeslami Chapter Twenty-four …………………………………………………...483 The Vatican Coffin Project Alessia Amenta

Section 2: Other Finds Chapter Twenty-five ……………………………………………...……503 Kushite Pottery from the Tomb of Karakhamun: Towards a Reconstruc-tion of the Use of Pottery in Twenty-fifth Dynasty Temple Tombs Julia Budka Chapter Twenty-six ……………………………………………….……521 A Collection of Cows: Brief Remarks on the Faunal Material from the South Asasif Conservation Project Salima Ikram Chapter Twenty-seven …………………………………………………529 Three Burial Assemblages of the Saite Period from Saqqara Kate Gosford

Table of Contents ix

Part E: Karnak Chapter Twenty-eight ………………………………………….………549 A Major Development Project of the Northern Area of the Amun-Re Precinct at Karnak during the Reign of Shabaqo Nadia Licitra, Christophe Thiers, and Pierre Zignani Chapter Twenty-nine …………………………………………………...565 The Quarter of the Divine Adoratrices at Karnak (Naga Malgata) during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty: Some Hitherto Unpublished Epigraphic Material Laurent Coulon Chapter Thirty …………………………………………………….……587 Offering Magazines on the Southern Bank of the Sacred Lake in Karnak: The Oriental Complex of the Twenty-fifth–Twenty-sixth Dynasty Aurélia Masson Chapter Thirty-one ………………………………………………..……603 Ceramic Production in the Theban Area from the Late Period: New Discoveries in Karnak Stéphanie Boulet and Catherine Defernez Chapter Thirty-two ……………………………………………..………625 Applications of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) in the Study of Temple Graffiti Elizabeth Frood and Kathryn Howley Abbreviations …………………………………………………………..639 Contributors ……………………………………………………………645 Indices …………….……………………………………………..……..647

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

THE BROAD HALL OF THE TWO MAATS: SPELL BD 125 IN KARAKHAMUN’S

MAIN BURIAL CHAMBER

MIGUEL ÁNGEL MOLINERO POLO*

Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife

Abstract: The walls of the main burial chamber of Karakhamun’s tomb were covered with the vignette of spell 125 of the Book of Going Forth in Daylight. This consists of the deceased entering the Hall of the Two Maats and facing the 42 judges, in addition to a scene of the weighing of the heart. A part of the texts com-posing the spell were also copied: in columns beside the deities (the declaration of innocence, BD 125B) and in a horizontal line topping the images (beginning of BD 125C). Their content is compared with earlier and later documents to place it in a diachronic evolution of the spell while the symbolic meaning of the represen-tation is analysed in relation to its location. A complex path that runs through the vestibule, courtyard, first and second pillared halls, descending staircase of two flights, two chambers, and shaft, was prepared for the journey of the body of Karakhamun to its final rest-ing place. The space was carved 20m below ground level. It features a rectangular plan of 4.54 x 3.19m with a height of 2.15m. In contrast to the main chambers in the majority of Late Period Theban tombs, it has a flat rather than a vaulted ceiling. Additionally, a large coffin pit was excavated into the bedrock. Eigner provided the first known and very brief descrip-tion of this space and its decoration. His only comments on the walls were “ebenfalls verschiedene Gottheiten”.1

The main burial chamber of TT 223 was rediscovered at the end of the 2010 season by the South Asasif Conservation Project (SACP). It was completely filled with debris up to 1.50m, scarcely leaving space to creep inside and to recognise the beauty of the astronomical representations on * The author thanks John Billman, member of the SACP, for his careful reading of this text and checking the written English. 1 Eigner 1984, 42.

270 Chapter Thirteen the ceiling and some remaining figures on the walls. The excavation of the chamber was undertaken during the 2011 season. Numerous fragments of painted limestone and plaster were discovered during the clearance. In total, almost 6,000 were recovered, varying in size from 1cm to 1m. While some of them can be attributed to the funerary equipment, the majority were once part of the ceiling and walls of the chamber. The fragments are stored in the tomb of Irtieru (TT 390), where they are displayed to allow identification and grouping by assumed provenance. From here, they are returned to their original location once it has been determined.

Conservation treatment was performed immediately after excavation with the fixing of some large pieces and consolidation of every chip that was loose. The majority of the reconstruction work was undertaken during the 2012 season and will be continued in future years. As an example of the labour expended, it can be noted that columns N10 to N13 (fig. 13-1) have been reconstructed from almost 40 fragments of varying sizes. Simi-lar treatment has been undertaken for the other 38 columns and the rest of the scenes. The effort involved and the difficulties that the team overcame in order to retrieve the lintel of the entrance—broken into more than 10 pieces—must be highlighted (fig. 13-2). During the first restoration sea-son, around 400 fragments had either been reinstalled or their original locations within the chamber had been identified and are currently await-ing installation once the walls have been prepared to receive them.2 This recovery work has allowed for the identification of the decorative pro-gramme. The decoration of the chamber, which is painted on the layer of plaster extended over the bedrock, is composed of (from bottom to top) the following:

a) A lower frieze comprising three broad bands with alternating solid yellow, red, and yellow colours, separated by black lines.

b) The vignette of Spell 125 of the Book of Going Forth in Daylight (BD), extending over the four walls of the chamber from west to east and organised through three distinct elements:

– Two images of Karakhamun, one on each side of the entrance, with his back to the opening. He raises his arms in adoration before the judges of the Hereafter. He dons a black wig, a white sash, and an elegant long kilt, clearly a dress for a special occasion.

2 The work of the conservation team of the South Asasif Conservation Project has to be highlighted; in the burial chamber, the tasks are directed by Abdelrazk Mohamed Ali and are developed with incredible ability, visual memory, and understanding by Said Ali Hassan, Mahmud Tayb Mahmud (Abdelhady), and Taib Said Mohamed.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 271

– 42 gods, divided into two groups of 21, expanding from the west wall to the east, all looking towards the entrance of the chamber. An iden-tical number of columns, one in front of each deity, reproduce the words addressed to them by Karakhamun. Each deity wears a black wig, black beard, and yellow collar. Furthermore, the figures alternate between hav-ing a green face and red body, or a red face with a green body. The invoca-tions (BD 125B) are written with black ink in cursive hieroglyphs over a yellow background surrounded by blue lines.

– The scene of the weighing of the heart, located in the middle of the east wall, concludes the vignette.

c) A horizontal line over the images and texts of the vignette on the four walls, in the same colours as the columns of the invocation to the judges. It contains the first part of BD 125C, a salutation to the gods of the Broad Hall of the Two Maats, i.e., to the deities supervising the negative confession and the judgement of the deceased.

d) A multi-coloured painted cavetto in two different registers topping the walls.

e) The ceiling, covered by the rather well preserved astronomical panel.3

Fig. 13-1: A part of north wall with reconstructed columns N10 to N13

(author’s photo).

3 Molinero Polo forthcoming.

272 Chapter Thirteen

Fig. 13-2: Lintel after reinstallation (author’s photo).

The Texts of the Vignette Over the adoring figures of Karakhamun, on both sides of the entrance, a very short legend identifies the tomb owner. His long list of titles and epithets is here reduced to a single one (fig. 13-3), ao HAt, “the one who en-ters”. In fact, five more appearances of it have been recognised in the burial chamber, four in the horizontal text and one more in blocks to be placed in the eastern wall’s scene. It must be an abbreviation of the title spelled fully as ao(w) Xr HAt pr(w) Xr pH. Both forms, the short and the extended one, are frequently attested in the inscriptions of the tomb’s first underground level; but they are never copied together: where one is used the other is not present. What is notable is that this title—in its abbreviated form—is the only one that appears within the burial chamber. This being a particularly relevant space, it might have been expected to find a more complete list of the functions and honorary titles accumulated by the pro-prietor during his life. For this reason, it is evident that Karakhamun identified himself with the meaning of this title. But its precise social value is unknown;4 Naunton considers that its short version may have meant a variety of different things according to context. It is possibly this kind of polysemy that made interesting its use in the tomb and, in particular, in the burial chamber.

4 Contrary to its usual translation (for example, PM I/12, 324: First ao-priest), Naunton (forthcoming) considers that it was not exclusively a priestly title.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 273

Figure 13-3: Karakhamun’s name over the twin figures on west wall.

The invocation to the 42 deities comprises the second part of the spell,

the so-called BD 125B. During the 2012 season, enough fragments had been recovered to make it possible to read nearly two thirds of the texts (figs. 13-4–5). The north wall is better preserved than the southern one and thus its reconstruction has achieved more accurate results. Only a single column (SE1) is completely lost and it cannot be known with certainty which deity and negative action were listed. Nevertheless, suggestions about its content can be assumed based on a comparison with typo-logically similar documents.5

Each invocation consists of three elements: the name of a male divin-ity, his place of origin (part “a” of the invocation), and the negative action over which he presides and what the deceased affirms to have never com-mitted (part “b”). In the reconstruction process it has been very helpful that each of these three elements begins and finishes with fixed signs: the vocative j and A40 for the name, pr m and, frequently, O49 for the prove-nance, and the negative n[n] and the personal pronoun for the third ele-ment. This has helped placing some of the fragments on the walls in addi-tion to identifying diagnostic pieces. In fact, the whole of BD 125B was usually presented in tabular form on papyri6 and while this is not exactly the case in TT 223—since the figures of the gods alternate with the col-umns of texts—the hieroglyphs create a form of visual litany that parallels the rhythm and intonation when the spell was uttered.

The condition of the burial chamber walls is good enough to recognise, with a few exceptions, the god invoked in each column and the declaration of innocence for which he supervises. However, the texts are still rather incomplete thus preventing, at least for the moment, a thorough analysis of the spell. Further reconstruction will allow for the incorporation of more fragments and signs, thus providing a firmer basis for broader studies on the language and textual transmission.

5 Following the order of other documents, they are possibly 18a and 17b, both absent in the preserved columns from TT 223. 6 Munro 1987, 204. She studies 42 New Kingdom documents with this spell (see Munro 1987, 266‒267, Liste 25). From them, only five are written as a continuous text, without any kind of graphic organisation (Typ A) and all correspond to the first part of Eighteenth Dynasty; the other 37 are structured in the form of lists inserted in a block (Typ B).

274 Chapter Thirteen

SE 2

SE 1

S 17

S 16

S 15

S 14

S 13

S 12

S 11

S 10

S 9

S 8

S 7

S 6

S 5

S 4

S 3

S 2

S 1

SW2

SW1

Fig. 13-4: Southwest, south and southeast text, first half of BD 125B.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 275

NE 2

NE 1

N

17

N

16

N

15

N

14

N

13

N

12

N

11

N

10

N 9

N 8

N 7

N 6

N 5

N 4

N 3

N 2

N 1

NW

2

NW

1

Fig 13-5: Northwest, north and northeast texts, second half of BD 125B.

276 Chapter Thirteen

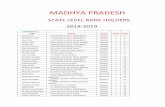

Given this situation, in which the order of the invocations is secure while there are still many gaps in their precise wording, the aim of this paper is threefold: to identify the model of the invocations that was fol-lowed during the creation of the copy transferred to the walls of the cham-ber; to place this model—and the one for the horizontal text—in a dia-chronic evolution; and to present some observations on the comparison of the burial chamber’s texts with those of other documents. These observa-tions could be understood as an approach—with the limitations imposed by the fact that it is centred on a unique and incomplete spell—to the question of the relationship of the texts from TT 223 to those of the Third Intermediate Period and of the Late Period. The sequence of invocations have been analysed in 30 documents.7 Given the high percentage of those known to contain the text of BD 125B,8 the conclusions presented here cannot be understood as valid for the general evolution of BD 125, since only a small part of its preserved copies are analysed. The objective pur-sued in this paper is to understand the version used in TT 223, for which these 30 examples could be considered, at least, as representative.

A sequence of invocations documented in several New Kingdom pa-pyri has been taken as “type”. This order has been identified in several copies (pL6, pC2, pL1)9 and it was, indeed, used by Lapp10 to organise his synoptic edition of this section of the spell. Some examples show small deviations from this pattern: a change in the order that affects only a lim-ited number of invocations (see KV 9 as an example in Table 13-1); dis-placement of a confession to the nearest column corresponding, in fact, to a different deity to the original one (see pC4).11 These changes could in-

7 The twenty-two New Kingdom documents presented by Lapp (2008) in his synoptic edition, to which eight of a later date—see corresponding columns in Table 13-1—must be added, including the text from TT 223. For codes used in this paper, see Table 13-2. Those of New Kingdom documents are the same as those used by Lapp 2008, XIII–XXIV. 8 470 objects include at least a part of BD 125, following the list in the Totenbuch-projekt of the University of Bonn: <http://totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/spruch/125> [accessed 15/09/2013]. 9 pL6 is highlighted with an arrow in Table 13-2 while the second arrow in the table corresponds to a Third Intermediate Period papyrus with the same organisation of gods and confessions. 10 Lapp 2008: 64–171. 11 Munro states that in texts presented in tabular form, such as the divinisation of the deceased’s body members of BD 42, this confusion is very common. She explains these irregularities through the difficulties experimented by the scribes when copying from the master copy, in which the text would be written in continuous form, to the table structure. Munro 1988, 170‒171.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 277 volve the occurrence of a new type if they were found in more than one copy. However, since the analysed instances are unique cases—at least in the 30 documents used in this paper—other explanations could be pre-sented: the variation may simply be due to scribal oversight (in pC3 invo-cation 36 is missing), to a specific desire, either from the scribe or the commander of the new document, to make some transformation in respect to the master copy, or caused by some unintended problem related to the process of conservation in archive or transmission.

Table 13-1: Sequence of BD 125B invocations in TT 223 and other documents.

278 Chapter Thirteen

– The oldest copy on which it has been identified is pL2 (pNuu) of the Eighteenth Dynasty.12 It is the only one with that sequence from the New Kingdom among those that have been studied, which would indicate a low percentage rate of usage of this pattern of invocations at this time.

– In the Third Intermediate Period, two papyri exhibit the same order-ing as pL2 (pNuu): one of the two versions of BD 125B of pNesi-tanebtasheri—the one written inside a shrine—and the tomb of Sheshonq III (North Royal Tomb V). It is interesting to note that a single master copy, probably in a Theban archive, was used for pNesitanebtasheri and some BD spells copied in the NRT I, belonging to Osorkon II.13 Further-more, BD 125 from the NRT I differs from the one used for NRT V where a new updated version was copied. A continued contact between the Tanite priests and Thebes could thus be assumed.

– The four documents studied dating from Twenty-fifth Dynasty on-wards show a unique sequence of invocations, similar to the one featured in TT 223. In none of the examples derived from this model is the order of the deities and negative declarations exactly alike. Each document displays some examples of confessions having been copied under the divinity next to its usual one and every case is different to the other. Despite these variations, an identical model can be recognised, underlying these changes. It is interesting that the division of invocations from the walls of Karakhamun’s burial chamber corresponds directly with the two registers in pIuefankh (pT101). Those of the south wall correspond with the upper group and those of the northern wall with the lower one.14

Following the first season of relocating fragments on the walls of bur-ial chamber it has been possible to obtain some information with regard to the textual version used within the tomb. Its invocations have been com-pared with the texts of the 30 documents mentioned above to detect varia-tions that provide clues about the diachronic evolution of the spell in rela-tion with the copy found in TT 223.

The first conclusion is that the transmission of the sequence of invoca-tions is relatively independent to its spelling. pNuu (pL2), the earliest copy on which TT 223’s organisation is identified, shows a textual version characteristic of the New Kingdom that differs from the version of the Saite recension, although this papyrus shares with late examples an identi-cal succession of deities and confessions. A notable example is the invo- 12 The text and numbering of the columns can be seen in Lapp 2008, 64‒171. See <http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/ search.aspx> BM EA 10477, sheet 23 [accessed 15/09/2013]. 13 Roulin 1998, 260. 14 Lepsius 1842, pl. XLVII.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 279 cation 15, in which the New Kingdom documents use, in some cases, the verb awA and in others awn. While pNuu uses the former, the latter appears in NRT V and thereafter. By contrast, from all the New Kingdom docu-ments collected by Lapp, pNuu is the only one that gives the epithet of nb to the god of invocation 22a, an epithet that is repeated by copies with identical invocation sequences from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty onwards.

Two royal tombs testify to some modifications of the spell during the Twentieth Dynasty, which influenced later versions. These latter copies re-flect the changes, but instead of reproducing them literally, they further develop their content. Meaningful examples are the negative declarations 40b, 41b, and 42b (figs. 13-6–7), which will be treated more extensively below.

One of the most notable conclusions of this transmission study is ob-tained from a comparison of the late texts with NRT V at Tanis, the tomb of Sheshonq III, from the Twenty-second Dynasty. The changes taking place in five Tanite invocations are kept in the model reproduced in later documents. This model is thus converted into the textual version for these invocations used by the Saite recension.

– Confession 5b (S3 in TT 223) is finished by m grg from this tomb onwards.

– The deity invoked in 26a (S9 in TT 223) received different names in New Kingdom copies: bAsty, jnbty, mxy, nwbty. From NRT V it stabilises around the verb smA, incorporated as the first part of the name.

– Confession 32b (N9 in TT 223) was originally n ja=j nTr, “I have not washed a god”, before becoming n jHw nTr, “of the divine cattle”.

– Confession 34b (N11 in TT 223) was n jr=j bjn “I have not done evil” during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties before changing to n jr=j mnw “I have not done wrong” in the documents from the Twentieth Dynasty onwards. In NRT V, a mixture of both versions is used: n[n] jr=j mnw bjn.

– Confession 35b (N12 in TT 223), n[n] jr=j Sntw r nsw “I have not committed revile against the king” is modified and enlarged during the Twenty-second Dynasty to nn Snty=j Hr nsw nn Snty=j Hr jt=j “I have not reviled the king, I have not reviled my father”.

Unfortunately, from column 35, the text of the tomb of Sheshonq III is lost so it cannot be determined which version was used in the writing of the last four invocations. These are especially significant since they also show a text in the Saite recension different to the one of New Kingdom.

Five invocations from TT 223 show a new version with respect to ear-lier copies that will become the norm for late documents. However, four of these summonses are lost in NRT V and therefore it cannot be known if

280 Chapter Thirteen they were already fixed when this tomb was carved. In consequence, it is not possible to state that they were innovations created during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, although in the set of texts studied for this paper, they are documented for the first time in it. Given the degree of transformation to the declarations of innocence detected in the tomb of Sheshonq III, it would not be impossible that these changes were also a product of the Theban priests of the Third Intermediate Period. These four modifications are:

– The spelling of jHw in confession 13b (S15). – The deity of the invocation 22a (N2), who is named nb zxm with a

rounded sign as determinative. – The texts of confessions 40b and 42b, both of them will be discussed

in the next paragraph. The only sure innovation of TT 223 is confession 16b (SE1), built in

early documents around the verb smtmt, to spy, NRT V included, and around the verbs sSm and sSmty from TT 223.

This list of modifications represents a permanent rewriting of BD 125B, a situation common to other Egyptian funerary texts. Moreover, some few cases have been found where Karakhamun’s burial chamber shows a text in consonance with early copies but different to those of Saite or later date. In the confession 25b (column N7 of TT23) Xnnw, turmoil, is written with , while in the later papyri it appears consistently as xnnw ( ), probably displaying a phonetic transformation.

Special mention must be made of the last four declarations of inno-cence, as they each show a deep continuing editorial process (figs. 13-6–7). After the minor transformations documented in the Twentieth Dynasty (KV 2), further changes are introduced in TT 223 and then the text is re-written again for later documents. None of these sentences are preserved in NRT V so it cannot be determined how they were spelled at its time. However, in two cases, the presence of signs that make sense in view of the late spellings raises the possibility that their texts were already known during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty:

– The final wAh in confession 40b (N17 in TT 223), is paralleled in pK101, pIahtesnakht.

– The k in confession 42b (NE2 in TT 223) cannot be understood as a suffix pronoun but recovers its meaning if it is understood as an abbrevi-ated way of writing ky Dd, which can be read several times in pT101, pIuefankh.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 281

Declaration of Innocence 39 Declaration of Innocence 40

pL6 pL2 KV2 TT 223 pK101 pT101 pL6 pL2 KV2 TT

223 pK101 pT101

Fig. 13-6: Text of the last four declarations of innocence in several New Kingdom and Late Period documents.

282 Chapter Thirteen

Declaration of Innocence 41 Declaration of Innocence 42

pL6 pL2 KV2 TT 223 pK101 pT101 pL6 pL2 KV2 TT

223 pK101 pT101

Fig. 13-7: Text of the last four declarations of innocence in several New Kingdom and Late Period documents.

If this suggestion were accepted, the reason for the incomplete writing

of these declarations on the walls of Karakhamun’s burial chamber would be the lack of space. Late versions of the declarations are longer than pre-vious ones and it could be that the artists of TT 223 chose not to reduce the size of the hieroglyphic signs even at the cost of severing the text.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 283

The horizontal line expands over the four walls, uniting both scenes: the invocation to the judges and the weighing of the heart (fig. 13-8). The text, called BD 125C, is less well preserved than the invocations to the judges, since bedrock pressure from above resulted in damage to the upper part of the walls. W/S/E

W/N/E

Fig. 13-8: Horizontal text with the beginning of BD 125C. The part of the spell copied on the walls reproduces two salutations to

the gods of the Hereafter. Each one extends symmetrically from the central axis of the lintel towards the two lateral walls and finishes with identical symmetry over the judgement scene. This desire to keep the axial disposi-

284 Chapter Thirteen tion led the artists to play with the names of the tomb owner that were included in the text. One is at the end of each lateral wall where the text requires a name or pronoun—they are not exactly at identical positions because of the different length of each sentence—and two more are on the east wall, at both sides of the central axis. Only scarce traces of its signs have been identified thus far but this is sufficient to determine that Karak-hamun was mentioned with the same title as that given beside the en-trance.

Originally the second salutation was longer than the first one. In the chamber, the southern (first one in papyri) is copied completely while the northern one is cut short when the available space was exhausted. The whole text is written very irregularly and while it is not an abbreviated version, some signs have been omitted in order to copy as much of the text as possible.

Some chronological references can be distinguished despite multiple lacunae and mutilated orthography:

– nTrw jmjw wsxt mAaty, at the beginning of the second salutation, dif-fers from the versions dating to the early New Kingdom (where nTrw is usually missing) as well as from those of the royal tombs of the Twentieth Dynasty (where it is spelled nTrw jpw jmjw wsxt nt mAaty).

– The ending of statives, with which the first salutation begins, is written systematically in the examples of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties, but not in those of Twentieth Dynasty or in TT 223 where it is only written with a stroke.

– nsw jmj hAw=f at the end of the first salutation and anx=f [m mAat] at the end of the second one (both in east wall of TT 223) appear from the Twentieth Dynasty onwards.

– Perhaps another reference could be added: the writing of sar (first salutation, south wall) with differs from that in documents of Twentieth Dynasty (with ) and is similar to the spelling in later copies. But the alternation s and z is a weak argument because of possible individual us-ages of these signs by the scribes. Nevertheless, it must be said that there is a certain consistency in the use of both signs in TT 223 in respect to the most common orthographies.

Karakhamun’s horizontal line, therefore, includes readings that are present in Twentieth Dynasty documents. However, it does not derive from the same master copy from the texts of the royal tombs of this date, from which it shows some differences.

The comparison with Late and Ptolemaic papyri is not rewarding, BD 125C being absent from many examples. In pQeqa it appears in such a brief version that is unrecognisable. Likewise, in pIuefankh, the first salu-

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 285 tation, the southern one in Karakhamun, is omitted, while the second one appears in a thorough copy and, from this point of view, exceeds the ab-breviated spelling of TT 223.

Fig. 13-9: Palaeography: examples of two different handwritings.

A palaeographic analysis of the texts on the walls,15 necessarily partial

since the reconstruction has not been finished, indicates that at least two artists were responsible for the copy. This can be determined by the dis-tinct forms of the signs (fig. 13-9). As for the distribution of working space between them, it was made in a different way to that proposed for Deir el-Medina’s artists, for which a division in two groups is proposed, each one working in a different side, left or right.16 The size of the tombs they decorated required a number of painters and, seemingly, a working method different from that of the relatively small chamber of Karakhamun.

The Weighting of the Heart Scene The main problem with the scene of the judgement of the deceased is its bad state of preservation. Fortunately, either in situ on the wall or as small

15 This work is developed in collaboration with Desirée Domínguez Carmona, from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 16 Grandet 2002, 44.

286 Chapter Thirteen fragments found in the debris, diagnostic elements have been identified allowing for the reconstruction of the composition of the vignette.

The process of virtual reconstruction began with the three written leg-ends (fig. 13-10). The one to the right of Osiris has been completed on the wall while the two others have been partly reconstructed in sand boxes. The placement is determined, in Thoth’s identification, from a fragment of the scale that is preserved on one of the blocks. As for the horizontal text of four lines, since it requires a minimum length (0.48m are preserved and the legend was broader), and the scale had to be placed more or less in the centre of the scene, the only available space is on the southern half of the wall. The texts are, respectively, the standard epithets of Osiris, Thoth, and the words spoken by the deceased in his justification. In the reconstruction of the scene presented here (fig. 13-11), all elements drawn are documented and they have been completed using near chronological par-allels and belonging to vignettes of the same typology.

To the right of Osiris Over Thoth Over the deceased

Fig. 13-10: Texts of weighting of the heart scene. For the typology of vignette it is important to highlight several points.

There is the absence of figures behind Osiris while Ammit is sitting (and not walking or standing) over a square shrine. Thoth is the next figure, as can be determined by the legend. He is followed by a large crook, which therefore implies that the deceased was depicted as a naked child sitting atop. Anubis was the first deity under the scales, since the ears have been preserved under the needle with the heart shape. This, therefore, means that Horus occupied the second position beneath the scales. Lastly, two feet of different colour and size, one red and another one green, indicate with certainty the position of two further figures. The first one is Karakhamun since he has to be in the scene and there is no other place for

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 287 him. Additionally, the horizontal text and the red colour of the feet con-firm this position. The second figure is Maat as it can be deduced from the position of the green feet and the fact that there is only room for one god-dess and not for a second, as is the case with other vignettes. All these elements determine that the vignette represents type E/I/a of Seeber’s classification.17 It cannot be said with complete certainty as to which of its three variants the scene corresponds, particularly as the diagnostic feature, the gesture of the deceased, has not yet been identified in the tomb of Karakhamun.18 By contrast, it can be determined that Maat should be embracing, or protecting Karakhamun, since this gesture is part of the common iconography of the model.

It has to be added that in this type of vignette, Shai, Renenutet, and Meskhenet, as well as the children of Horus, are commonly included and therefore they should be expected in TT 223. The blank spaces between the legends, for which nothing is for the moment preserved or at least identified, could be a possible place for them.

The presence of type E is meaningful chronologically. It is first docu-mented in Tanis, in the tomb of Sheshonq III. At this time, the master copy underwent subsequent variations and the number of deities and their order were changed afterwards. Karakhamun’s vignette would be one of the oldest known documents of subtype E/I/a. Another similarity between TT 223 and Sheshonq III’s tomb is the placement of this spell in the burial chamber, since in previous and later royal and private tombs it is com-monly included in the antechamber.19

17 Seeber 1976, 242. The position of the feet of the goddess excludes the possibility that she is in front of Karakhamun facing him and, therefore, it cannot correspond to the type E/I/b in any of its three variants or to type E/II because there is no space for a second figure of Maat. 18 E/I/a/2, with the deceased, in a gesture of salutation, is only documented in the Ptolemaic Period although this is not an argument to exclude this subtype. E/I/a/3, with the justified deceased in adoration, is first documented in the tomb of Sheshonq III at Tanis where the additional presence of several figures not present in TT 223 also reduces the possibility of this model. For these reasons, the reconstruction proposed in figure 10 presents Karakhamun in gesture of justification, in correspondence with type E/I/a/1, which is moreover well attested during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. This image should be taken as a suggestion only without excluding other possibilities. 19 New Kingdom. From 55 Theban tombs with BD 125 collect by Saleh (1984, 71), only (TT 82 and TT 156) have the text in the burial chamber. In this number, the tombs of Deir el-Medina have not been retained, since they do not contain an antechamber and therefore, the decoration is always in the burial chamber or in the chapel on the surface.

288 Chapter Thirteen

Drawing: Daniel M. Méndez-Rodríguez Fig. 13-11: Reconstruction of east wall with weighting of the heart scene

(© Daniel M. Méndez-Rodríguez). To conclude, an absent element that should also be expected must be

considered, that is to say, the hall where the scene should take place. In the reconstruction of the vignette there is no space for columns or other archi-tectural elements. Until the creation of this vignette-type, the image of a building was usually represented to protect the text of the negative confes-sion. In type E, the 42 judges and the weighing of the heart are usually positioned under the same roof. This roof is also somehow present in TT 223, through the cavetto that tops the four walls, thus acquiring a symbolic meaning that is probably not recognised at first view. Since the cavetto is, at the same time, the cornice of the walls of the burial chamber, this room seems to become the Broad Hall of the Two Maats, as it is called in the horizontal text itself. Some Additional Final Interpretations “Come thou, enter, through this gate of (this) broad hall of the Two Truths, for thou knowest us”.20 The two figures of Karakhamun, represented just

Late Period. Beside TT 223, BD 125 is documented in Padiamenope, Mutirdis, Padihorresnet, and Sheshonq (Einaudi 2012, 34). It is copied in a different wall in each tomb and only in Karakhamun it is placed in the burial chamber (Einaudi 2012, 21‒27). 20 Allen 1974, 100.

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 289 after having crossed the threshold of the burial chamber, are a visual re-production of these words. The concepts of transit and qualification,21 frequent in Egyptian funerary liturgies and essential for the deceased to reach salvation, are figuratively embodied here. The concept of transit through the location of the images right after a winding way that guides down to the chamber, a route described in the opening paragraph of this chapter; this path can be understood as the architectonical equivalent of the mythical doors and passages, often guarded by menacing deities, that make part of funerary compositions (for example, BD 144–147). The second, qualification, through the location of the two figures right after the crossing of the door, visualising the words that open this paragraph; these words make part of a dialogue reproduced in BD 125C (the beginning is written in the horizontal line) in which the deceased has to show his knowledge about himself, funerary rituals, and the gate through which he has to pass. This knowledge is imperative in order to gain admittance to the tribunal of the Hereafter, represented on the nearby walls, and Karakhamun is obviously depicted after having succeeded in passing these tests.

Grieshammer identified the similarity between the different categories in which the sins mentioned in BD 125B and those listed in Late Period temple doorways could be organised.22 Assmann qualified them as “admit-tance liturgies” suggesting that priests probably had to recite them when entering the pure space of the sanctuary, just as the deceased had to give assurance of his cleanness upon entering the sacred sphere of the Hereaf-ter.23 Moreover, these liturgies could have been part of a ritual of initiation that priests had to pass in order to reach their position, and which they had to continue reciting every day upon coming into the temple to hold their office. These liturgies would have become a model on which had been built the conceptions about the need for the deceased to suffer a transfor-mation that gives him access to the underworld; nevertheless it leaves open a chronological problem, since the priestly vows are documented in much later documents than the declarations of innocence, as shown in BD 125B, that was already established at the beginning of the New Kingdom. In turn, Gee has shown that only the categories of priests who had passed through the initiation ritual could take part in one of the activities explic-itly mentioned in the daily ritual and on the walls of some temples: mAA nTr, to see the god.24 This is also the reward for the deceased having passed 21 Assmann 1989, 146–152. 22 Grieshammer 1974, 22–24. 23 Assmann 1989, 151. 24 Gee 2004, 100.

290 Chapter Thirteen safely through the judges of the Hereafter: to arrive at the place where the scale is, the last obstacle before seeing Osiris. It is probably not out of place to wonder if there is any relationship between the position of the priest who enters to the vicinity of the god and the only title of Karakhamun mentioned in the chamber, for which a certain ambiguity or polysemy have been stated. From the long list of titles known from the inscriptions of both Pillared Halls of the tomb, the only one included in the burial chamber is ao HAt, “the one who enters first/towards the front”.

Egyptian funerary beliefs emphasised the importance of keeping per-sonal identity, reception of foodstuff, and justification, for survival in the Afterlife, three concepts narrowly intertwined. Individuality in life was the result of social recognition. Following the principles of operation of state run economy, eating and drinking, as a result of redistribution, are materi-alisations of social integration. In turn, social integration in life represents the prerequisite for eternal nourishment in the Hereafter. Moreover, eternal survival among the entourage of the Beyond depended also on justifica-tion, i.e., on the victory against any opposition. Judges, Ammit, the very heart on the scale in the judgement scene acted as metaphors of all poten-tial enemies. From the development of the figure of Osiris, at the end of the Old Kingdom, these three concepts were under the protection of this god, and they will be even more dependent on him when his figure gains further importance from the Twenty-second Dynasty onwards. The omnipresence of Osiris at Thebes is witnessed by the numerous chapels devoted to various forms of the god erected in Karnak by the Divine Adoratrices of the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasties.25 This situation is also reflected in Karakhamun’s tomb. The textual and iconographical program of several chambers emphasise that it is the proximity to the god that grants eternal sustenance and justification, both of which are necessary to assure personal individuality. The Second Pillared Hall reliefs, with the occurrence of several offering lists, highlight the submission of foodstuff to the god and its reversion to the tomb owner. The iconographical message on the walls of the burial chamber focuses on overcoming impediments in order to gain salvation; a personal salvation since, as it has to be remembered, the name of Karakhamun is written at least seven times in its walls.

25 See, for example, Coulon’s paper in this volume.

292 Chapter Thirteen Bibliography Allen, Thomas G. 1974. The Book of the Dead, or, Going Forth by Day.

Ideas of the Ancient Egyptians Concerning the Hereafter as Expressed in Their Own Terms. SAOC 37. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the Uni-versity of Chicago.

Assmann, Jan. 1989. “Death and Initiation in the Funerary Religion of Ancient Egypt.” In Religion and Philosophy in Ancient Egypt, ed. William Kelly Simpson, 135‒159. YES 3. New Haven: Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Graduate School.

Budge, E. A. Wallis. 1912. The Greenfield Papyrus in the British Museum. The Funerary Papyrus of Princess Nesitanebtáshru, Daughter of Painetchem II and Nesi-Khensu, and Priestess of Amen-Rā at Thebes, about B.C. 970. London: The British Museum.

Eigner, Diethelm. 1984. Die monumentalen Grabbauten der Spätzeit in der thebanischen Nekropole. UZK 6; DÖAWW 8. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Einaudi, Silvia. 2012. “Le Livre des morts dans les tombes monumentales tardives de l’Assassif.” BSFE 183: 14‒36.

Falck, Martin von. 2006. Das Totenbuch der Qeqa aus der Ptolemäerzeit (pBerlin P. 3003). Handschriften des Altägyptischen Totenbuches 8. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Gee, John. 2004. “Prophets, Initiation and the Egyptian Temple.” JSSEA 31: 97‒107.

Grandet, Pierre. 2002. “La communauté d’artisans de Deir el-Medineh sous les Ramses.” In Les artistes de Pharaon. Deir el-Médineh et la Vallée des Rois, ed. Guillemette Andreu, 43‒47. Paris; Turnhout: RMN; Brepols.

Grieshammer, Reinhard. 1974. “Zum ‘Sitz im Leben’ des negativen Sün-denbekenntnisses.” In XVIII. Deutscher Orientalistentag vom 1. bis 5. Oktober 1972 in Lübeck. Vorträge, ed. Wolfgang Voigt, 19–25. Supp-lement ZDMG 2. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Lapp, Günther. 2008. Totenbuch Spruch 125. Totenbuchtexte. Synoptische Textausgabe nach Quellen des Neuen Reiches 3. Basel: Orientverlag.

Lepsius, Richard. 1842. Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter nach dem hierogly-phischen Papyrus in Turin. Leipzig: Wigand.

Molinero Polo, Miguel Ángel. Forthcoming. “A Bright Night Sky over Karakhamun: The Astronomical Ceiling of the Main Burial Chamber in TT 223.” In Tombs of the South Asasif Necropolis: Thebes, Ka-rakhamun (TT 223), and Karabasken (TT 391) in the Twenty-Fifth

The Broad Hall of the Two Maats 293

Dynasty, ed. Elena Pischikova. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Montet, Pierre. 1947. La nécropole royale de Tanis. Tome premier. Les constructions et le tombeau d’Osorkon II à Tanis. Paris: [s.n.].

———. 1960. Les constructions et le tombeau de Chéchanq III à Tanis. Paris: [s.n.].

Munro, Irmtraut. 1988. Untersuchungen zu den Totenbuch-Papyri der 18. Dynastie: Kriterien ihrer Datierung. StudEgypt. London: Kegan Paul International.

———. 2001. Das Totenbuch des Pa-en-nesti-taui aus der Regierungszeit des Amenemope (pLondon BM 10064). Handschriften des Altägypt-ischen Totenbuches 7. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Naunton, Christopher. Forthcoming. “Titles of Karakhamun and the Kushite Administration of Thebes.” In Tombs of the South Asasif Ne-cropolis: Thebes, Karakhamun (TT 223), and Karabasken (TT 391) in the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, ed. Elena Pischikova. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Roulin, Gilles. 1998. “Les Tombes royales de Tanis: analyse du pro-gramme décoratif.” In Tanis. Travaux récents sur le Tell Sân El-Hagar 1 Mission Française des fouilles de Tanis 1987–1997, eds. Philippe Brissaud, and Christine Zivie-Coche, 193‒276. Paris: Noêsis.

Saleh, Mohamed. 1984. Das Totenbuch in den thebanischen Be-amtengräbern des Neuen Reiches: Texte und Vignetten. AV 46. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

Seeber, Christine. 1976. Untersuchungen zur Darstellung des Toten-gerichts im Alten Agypten. MÄS 35. München; Berlin: Deutscher Ku-nstverlag.

Verhoeven, Ursula. 1993. Das saitische Totenbuch der Iahtesnacht: P. Colon. Aeg. 10207. PTA 41, 1‒3. Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt Verlag GMBH.