THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF EL CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANGO, MÉXICO

Transcript of THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF EL CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANGO, MÉXICO

CHAYIER8

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITEOF EL CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO,

DURANGO, MÉXICO

Jaime Ganot R. andAlejandro A. Peschard F.

For almost fifteen years, the authors of this paper have carried out a sur-

face reconnaissance of a large part of the state of Durango, México, andparts of the neighboring states of Zacatecas, Coahuila, Sinaloa, Nayarit, andJalisco with the aim of finding and recording archaeological remains. Our

interest initially was directed toward the study of sites with rock paintings;

however, we found several sites with remains of Mesoamerican occupation

that were not reported previously in the archaeological literature. One of

these sites seemed particularly important, not only because of its large size,

but also for the richness of the archaeological material. This was the site of

El Cañón del Molino (Figure8.1).For manY years, peasants of small towns near the city of Guatimapé, in

the county of Canatlán, Durango, found stone structures while working in

their fields and orchards along the terraces of the Guatimapé River. Exca-

vating for buried treasure beneath these structures, they often found

human bones that were sometimes accompanied by pottery and other arti-facts. For years, these grave goods were collected by families in the villages

and put to practical use. For example, at Christmas time they would exca-vate for large ollas (funerary urns) to use aspiñatas to be at theposadas(Christmas festivities) of the town.

As members of the Society of Friends of the Museum of Durango, and re-cognizing the importance of the archaeological material found, we rescuedsome of the objects collected by the families of the region, and with the

CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANCO, MÉXIco 147

«;

10 State of Durango

••,es ••"'.• ,O> '"

Figure 8.1. Location of the Cañón del Molino site in the state oi Durango, México.

valuable help of Dr. J. Charles Kelley, we analyzed and classified the mate-

rials. This project allowed us to identify this site as one of several in which

the same cultural pattern is present. The others include the Navacoyán,

Schroeder, La Breña, Nicolas Romero, Valle Florido and Puerta de la Can-

tera, sites in the Guadiana Valley; Canatlán, Flores Magón and Cacaria in

the Canatlán Valley; Cerro de los Lobos near Guadalupe Victoria; Hervi-

deros near Santiago Papasquiaro; Tepehuanes and Santa Ana near El Zape.

All of these sites are located in central and northern Durango (Ganot et al.

1983;Ganot and Peschard1985, 1990: 401-416;Peschard and Ganot1990).We have proposed that this regio n was part of the great area of occupa-

tion of the Aztatlán Culture that included the states of Sinaloa, Nayarit,

Jalisco, and Michoacán (Ganot et al.1983;Ganot and Peschard1985; 1990:401-416). Also Kelley (1986: 81-104) has postulated that this area had im-

portant functions in the prehispanic trading routes of Mesoámerica, and

extending into the southwestern United States. Preliminary findings con-firm the importance of this site and we expect that formal studies will shednew light on the cultures of northern México, providing new perspectivesof cultural interactions there.

148 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARD F.

u IlED OF AMEFICA

I ANASAZI

2 HOHOKAM

3 MOGOLLON

4 CASAS GRANDES

5 JORA MAYRAN

6 CHALCHIHUITA

7 GUASAVE

8CULlACAN

9TACUICHAMONA

IOAZTATLAN

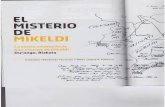

Figure 8.2.Main Post Classic culturesin the northwest 01México and southwestern United States.

HIsTORICAL BACKGROUND ----

The first historie reference to the existence of Indian towns in the Valley of

Guatimapé are found in the Spanish documents of the sixteen century.One of these, referring to the "Villa de Nombre de Dios," states:

It was one year ago[1562] that we were there, and that the church

for God was built, when our priest began looking for new land, thatis, the one called Friar Diego and the priest Friar Jacinto and theMexicanos, prompt to depart, they headed to Guatimapé in thegreat plain. The natives carne to meet them and they were com-forted by the principals (Barlow and George1943: 24 [1562]).

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXIco 149

In 1563, Baltazar de Obregón, the diarist of Francisco de !barra, stated

that in the expedition the conqueror made to Topia, !barra met the nativesof the Valley of Guatimapé. The text says that on arriving to the Valley of

Guatimapé, he had difficulties created by his field master, who had tried tosteal the corn kept in a barn, from the natives of a small town (Obregón

1924: 52 [1584]).This situation provoked a confrontation of great impor-

tance. In revenge, the Indians began to steal the expedition's cattle, thus

starting two fights that ended with the defeat of the Indians and the re-

covery of the stolen cattle. These events, which certainly took place in the

Cañón del Molino, were recorded in the narration described above and in

a rock painting found in a nearby cave. In this Cueva del Charco Azul were

depicted scenes of war between soldiers on horseback and armed natives(Lazalde et al.1983: 8-9).

In a paper on Francisco de Ibarra, J. Lloyd Mecham(1927: 118)points

out that in the Valley of Guatimapé an Indian woman was recruited by the

Spaniards because she knew the way that would lead conqueror to Topia,thereafter crossing the Sierra Madre Occidental to the coast of Sinaloa.

In the geographic description of the provinces of Nueva Galicia, Nueva

Vizcaya, and Nuevo León, written by the Bishop Don Alfonso de la Mota yEscobar described a site that corresponds to El Cañón del Molino and

other nearby Indian towns:

Going out then from La Sauceda, heading to the North two leagues

away, there is a small town of Chichimecs called Capinamíz. Seven

leagues ahead, there is another town of Chichimecs called

Texamen, almost uninhabited, that they name Las Bocas and Guati-

mapé; and they all have good health, good waters and mountains

(de la Mota y Escobar1940: 201 [1602-1605]).

During bis reconnaissance of the state of Durango, J. Alden Mason was

taken to the site of Cañón del Molino by the countrymen of the nearby

towns. Passing over the lower part of the region, Mason noted:

The next site observed, going northward, was at Guatimapé, on thewest side of Lake Santiaguillo about90 km north of Durango City.Here in the valley of the Canyon Molino are many house sites by apermanent strearn. These are mainly rectangular and outlined by

buried stones as at Antonio Amaro, often in terraces one above

and behind another. Some of these terraced sites are up to 9 x15m

in size. There are also some smaller round sites 2.5 to 3 m in dia-

meter made of larger boulders. There are the ruins of a rude rec-

150 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARD F.

tangular masonry structure about 7.2 x 4.2 m in size with walls built

of massive stones 60 cm, thick to a present height of about 1.5 m,but we could not certify it as being aboriginal. Parts of the site were

retained by stone walls. Manymanos and metateswere fou~d, so~esmall rude animal figures of lava, and a few potsherds, mcluding

one ladle handle of red-on-buff ware. Themeta tefragments found

indicated that they were trough shaped, without legs. Themanos

are of lava or granite, quasi-rectangular, and rather thin with one

or both faces convex (Mason 1971: 137).

It is possible that El Cañón del Molino was one of the places of mytho-

logical wealth that aroused the ambition of the Spanish conquerors and

resulted in the exploration and conquest of the north and west of Nueva

España.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT ----

The cultures represented at the site of El Cañón del Molino and other sites

of the region are: The Chalchihuites (from northwest Zacatecas and central

and southeast Durango), the Aztatlán (from Jalisco, Nayarit, Michoacán,and Sinaloa), the Loma San Gabriel (widely spread throughout the moun-

tains of the Sierra Madre Occidental and including the states of Chi-

huahua, Durango, Nayarit, and Jalisco), and the cultures of the Coahuila

Desert (Figure 8.2).

Chalchihuites Culture

In 1935, J. Alden Mason undertook an extensive surface archaeological re-

connaissance in Zacatecas and Durango, looking for sites or settlements of

hunters and gatherers of the Folsom horizon. Although he was unable to

locate these, he did report a number of sites with similar decorated cera-

mies, pottery spindle whorls, and other artifacts. On this basis, he proposedthe existence of a general culture for the area that he termed Chalchihuites(Mason 1971: 130-1459). Donald D. Brand's 1936 study of the ruins of El

Zape, in northern Durango supported Mason's proposed MesoamericanChalchihuites culture. Brand (1971: 47-49) also identified some archaeo-logical material as similar to that he had found in sites of the Aztatlán

Culture on the west coast ofSinaloa and Nayarit (Brand 1971: 47-49).

The most extensive studies of the Chalchihuites Culture are those ofKelley. In 1954, he undertook excavations at the Schroeder site in

Durango, and later at Cerro de Moctehuma, Cerro Pedregoso, Alta Vista,

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXIco 151

and other sites in Zacatecas, Kelley has established a ceramic classification

and has proposed a chronology, based on stratigraphy, a number of radio-carbon dates, and the analysis of great quantities of ceramic materials. TheChalchihuites is divided by Kelley in two branches: the Súchil branch,

located in the valley of the Río Colorado, Zacatecas, and on the drainage of

the Río Súchil, Durango; and the Guadiana branch in the Guadiana Valley

and elsewhere in central and northern Durango (Kelley 1966: 97-102;

1971: 778-798; 1985b:271-287; 1990:487-519).

Aztatlán Culture

The "Aztatlán" name was first used by Carl Sauer and Donald D. Brand to

designate a group of archaeological sites with common cultural. characteris-

tics that they had identified from a surface survey of the Pacific coast ofSinaloa and Nayarit. Chosen from the names of traditional Indian designa-

tions calledProvincias by the Spanish conquerors, Sauer and Brand con-sidered the Aztatlán occupation area as limited to the north by the Río

Culiacán, to the south by the Río Santiago, and to the west by the Pacific

Ocean. The scarped mountains of Sierra Madre Occidental was the natural

eastern limit of the culture (Sauer and Brand 1932: 4-6).The province of Aztatlán appears on several old post-conquest maps, in-

cluding the Abraham Ortelius of 1584; the Mapa Portulano de las Costas

Occidentales, 1587, by Juan Martínez; H. Iaillot's map of 1694; and on

America Septentrional by Sanson d'Abbeville, 1715. It is remarkable that

on these maps, the name Aztatlán is written in a different direction than

are other names, in such a way that it seems to be designating an area that

includes not only the Pacific coast, but also part of the highlands of thenorth of México (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática

[INEGI] 1982: 50-51, 54-55, 65, 190-191).Later, Isabel Kelly used the term "Aztatlán Complex" to designate

several place s that also had similar ceramic types in common, including thecharacteristic polychrome and incised Aztatlán type (Kelly 1938: 36; 1945:

118-121; 1948: 55-71). Gordon Ekholm reported a large quantity ofAztatlán pottery from Guasave, Sinaloa, and postulated that this site had a

principal occupation by this same culture. He found several vessels deco-

rated with motifs similar to some in Mesoamerican Codices and was thus

able to postulate a relationship between the Aztatlán culture and others

from central México, such as the Mixteca-Puebla. In addition to the

ceramic evidence, there were other archaeological materials from Guasave

that further widened the Aztatlán culture concept (Ekholm 1942: 125-129).

152 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARD F.

Subsequently, Aztatlán-type objects have beenreported from several

areas on the coast of Nayarit and Sinaloa and in the highlands of Jalisco

and Michoacán (Lister1949: 29, 98;Gifford 1959; Glassow 1967: 78, 82;Meighan 1968: 14-15, 63,Meighan 1976: 248-254;Scott 1974: 54;Mount-joy 1982: 267-268). In the Schroeder site, Kelley and Winters found

Guadiana Branch Chalchihuites ceramics associated with pottery, spindle

whorls, and copper bells similar to those described from the Pacific coast.

On this basis, they revised the chronological sequence of the Sinaloa

coastal cultures (Kelley and Winters1960: 547-561).In 1985,we reported the presence at El Cañón del Molino of archaeolog-

ical objects similar to those of the coast, and we proposed that this material

be used as a marker for a common culture that occupied a very large terri-

tory of the present states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Sinaloa, and Durango. The

Aztatlán culture appeared in the late Classic, was completely developed in

the Postclassic of the Mesoamerican chronology, and some sites were still

inhabited at the time of Spanish contact (Ganot et al.1983, Ganot and

Peschard 1985, 1990: 401-415;Peschard and Ganot1990). It is probable

that cultural interactions took place along the Río Lerma, a well-known oldIndian trading route between Aztatlán and the central México civilizations

of the Mixteca-Puebla and Mazapa and Coyotlatelco phases of the Tolteca

culture (Muller 1948: 50-54;Jiménez-Moreno 1975: 57).

Loma San Gabriel Culture

The Loma San Gabriel Culture was reported by Kelley in1956and studiedintensively thereafter by Michael S. Foster. It was initially defmed from type

site on hills surrounding the Río Florido near the town of San Gabriel,

Villa acampo, Durango. It has been described as marginal sub-Meso-

american and as a predecessor of the modern-day Tepehuanos and other

Indian groups of the Sierra Madre Occidental in the states of Chihuahua,

Durango, Zacatecas, and Nayarit. The material culture is simple, consisting

of ceramic and stone objects for daily usage. The ceramics are coarsely

elaborated and are of simple shapes, although some tripod vessels re-

sembling Chalchihuites types have been found (Kelley1956: 172-176;Foster 1978, 1985: 327-351).

SITE DESCRlPTION _

El Cañón del Molino is situated near the towns of Esfuerzos Unidos, ElMolino, and Guatimapé, in the county of Canatlán, Durango, approxi-

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXICO 153

,/. ~(

/

Figure 8.3. Topographic map 01 the Cañón del Molino archaeological area.

mately 8 km southeast of Lake Santiaguillo. It is on one of the mountains

of the Cordillera de los Zorrillos, which is the western limit of the Guati-

mapé Valley. Between these mountains and the lake, there are large areas

154 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARD F.

of farmland, which, together with fishing and hunting activities, havefurnished ample food to the populations that have settIed in this regio n

throughout the ages.The archaeological structures, which are built of masonry typical of the

Chalchihuites culture, are distributed in two different areas. The first issituated on the fluvial terrace northeast of the Río Guatimapé, extendingalong the canyon of El Molino, limited by the river and the mountain range

of Los Zorrillos (Figure 8.3A). The terrace slopes toward the river with a

level difference of about 60 m. The archaeological material extends over an

area approximately 4 km in length and about 250 m at the widest parto This

part of the terrace is divided transversely into four sections by intermittent

streams draining the high portions of the range. There are several springs

in the upper area (Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto [SPP]).

The structures found here are composed of terraces, platforms, patios,

mounds, and altars. The terraces conform to the slope of the terrain; they

are rectangular and are bound on the sides by lines of stone slabs placedvertically, and on the downhill side by retaining walls. Their floors are filled

in where necessary to level the surface and are topped with arranged

stones. On the terraces, and sometimes only above the flat surfaces, there

are rectangular platforms bounded by the same type of stone slabs just de-scribed. These platforms may occur as isolated structures or in groups of

four platforms arranged around a patio containing a central stone altar.

This part of the site has been partially destroyed by farming, cattIe, and by

the excavations made by people looking for treasure.

The second area of structures is situated on the top of a hill approxi-

mately 200 m above the river level (Figure 8.3B). This plateau is oval in

shape, about 325 m long and 200 m wide, and is surrounded by steep diffs,except on the northern side. Its longest axis has a north-south orientation

and its elevation above sea level is 2,100 m. The Guatimapé Valley can beseen from here.

The structures he re are well preserved and because of the location,

appear to be the ruins of a fortress. There are remains of stone walls, twoon the north, two on the south, and other small walls at different levels on

the southeastern side. The structures apparentIy are of two differentperiods. The older ones are on the southern end of the plateau and aref~rmed by large, coarsely made slabs set vertically in severallayers, formingcircles. The other structures have a setting similar to those described forthe lower terraces, although these are more complex. At the south there lie

groups of platforms and patios with altars in their interiors. There is also

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉX1co 155

f_~t·~:~.- ~-:,

• Monticle

DTerrace

Slab stone line50mts

Imprecise limitCAÑON DE EL MOLINO

ffiillJ Yard

~Altar

Constructions inthe tophill (scheme)

Figure 8.4. Hilltop construction at Cañón del Molino.

another type of patio in which there are only three surrounding platforms

with one open side. Above the platforms there are several stone mounds

that appear to be small shrines. The buildings are oriented with their major

axis 335 degrees north-northwest of magnetic north (Figure 8.4).

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION ----

In order to analyze the cultures involved in the Cañón del Molino settIe-

ment, we will first mention those artifacts from the site that are character-

istic of neighboring cultures, followed by a discussion of objects that have a

more extensive distribution.

Chalchihuites Culture

Numerous decorated and undecorated cerarnic pieces representative of the

Guadiana Branch of Chalchihuites Culture have been found at El Cañóndel Molino. Corresponding to the Las Joyas, Río Tunal, Calera, and Molino

phases, they date from A.D. 850 to about the time of Spanish contact

(Figure 8.5). In the Río Tunal and Calera material, AztatIán influence

resulted in the appearance of a new ceramic type, in which morphologic

156 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARDF.

Figure 8.5. Chalchihuites ceramics from El Cañón del Molino.

and decorative features are mixed; this is called El Molino Red-on-cream

(Figure 8.6). In contrast to the abundance of material from the Cuadiana

Branch, only a tripod and a few potsherds from the Alta Vista Phase of the

Suchil Branch were found (Peschard et al. 1986).

Loma San Gabriel Culture

Ceramic material is the most numerous manifestation of the Loma San

Cabriel Culture at Cañón del Molino. It is composed of monochrome

coarse pottery of simple shapes, although there are some pieces that

appear to be bad copies of Chachihuites ceramics, including basket-

handled bowls, vessels with coarse designs in red, and others with plaster

(Figure 8.7).

Aztatlán Culture

There is a great quantity of objects, particularly pottery, similar to thosealready described for the Aztatlán Culture. In fact, Aztatlán materials re-present the principal diagnostic traits for this site, including several pottery

types that have been identified along the Pacific coast.

Isabel Kelly described Aztatlán ware, red-rimmed vessels with externalred-on-brown decoration (Kelly 1938: 19; 1945: 27-29). Near the exteriorrim, vessels have a band painted in white with incised motifs (Figure 8.8a,

b). The most representative pieces of Cuasave Red-on-buff were describedby Cordon Ekholm from Guasave, Sinaloa, although this type is wide-

• CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXIco 157

Figure 8.6. El Molino Red-on-cream.

• ••• 1-

Figure 8. 7. Loma San Gabriel oessels.

spread in all Aztatlán sites. The hemispherical bowls have red rims and ex-

ternal red-on-buff designs, some similar to drawings in codices from central

Mesoamerica, such as figures of Xinecuilli and Xicalcoyuqui. A variation of

this pattern is one in which the decorated band is in white, making itresemble the Aztatlán types (Ekholm 1942: 46-49) (Figure 8.8c, d). The

Lolandis types has been described by Kelley from specimens found in the

158 GANOT R. ANO PFSCHARD F.

db

------~Figure 8.8. Aztatlán, Guasave and Lolandis ceramic types.

Durango sites, and similar specimens have been found over much of theWest Coast area. Lolandis vessels are mainly shallow bowls, red-rimmedwith interior decoration. Below the rim there is a band with different geo-

metric motifs; in the center of the bowl there usually are painted figures in

a quadrant pattern (Kelley and Winters 1960: 552-554) (Figure 8.8e).Funerary urns are another Aztatlán trait found at El Cañón del Molino.

These are ollas of various sizes, usually large. They are usually decorated in

monochrome, but may be bichrome red-on-buff; only one has been noted

with geometrical designs in red-on-cream. All of these jars have a hole

approximately 3 cm in diameter in the middle of the body. Burial in fune-

rary urns was a common practice of the cultures of West Mexico, but it has

not been described for the Chalchihuites Culture. According to thepeasants of the are a, this type of burial was only practiced for children(Figure 8.9).

A certain characteristic pottery spindle whorl is another Aztatlán trait.

These are of spherical shape, with well polished surfaces, buff or black in

color and usually decorated with engraved geometric designs filled with

white paint Brand (1971: 41). described these at El Zape, Durango, andcompared them with the ones from the coast of Sinaloa.

Other Areas

In addition to the above, there are examples of decorated pottery identifi-able with types described by Meighan from late phases at Amapa, Nayarit.These include Iguanas Polychrome, which gene rally are goblets with a

CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANGO, MÉXIco 159

Figure 8.9. Decorated lunerary urns.

wide, annular support and exterior decoration. The borders have a design

of squares of severa! colors, then a wide band of stepped scrolls, sometimes

with motifs similar to designs found in the codices. In the interior bottom,

there may be deep incisions inmolcajete form (Figure 8.10a). Tuxpan En-

graved is a usually black monochrome ware with exterior decoration of in-

cised geometrica! designs similar to those found on type 2C spindle whorls

in Meighan's Amapa classification (Figure 8.10b). Mangos Engraved vessels

have externa! bands of different colors bordered by incised lines. The most

common motifs are concentric circles and zigzag lines (Figure 8.10c). Santi-ago Red-on-orange vessels have externa! designs in red paint, usually hori-

zontal bands and rows of triangles with low peaks. On the vessel body are

severa! wide oblique lines that radiate toward the base (Meighan 1976:

plate 133, 165b, 155e, f, 166a) (Figure 8.10d).Culiacán Polychrome was described by Isabel Kelly from Culiacán,

Sina!oa. These are vessels with externa! decoration in white, red, brown,

and black. On the rim are three bands of rows of dots; the rest of the body

is decorated with stepped grecques (Kelley 1945: figure 19) (Figure 8.11).

There are severa! types of pottery pipes. Some have incised decoration

filled with white paint and are similar to those described from Tacui-

chamona, Sina!oa (Sauer Brand 1932: figure 14). Others have a platformbase with a globular bowl similar to those termedCocoyolitos from

Chametla, Sinaloa (Kelly 1938: figure 23). Other pipes have a long stem

160 GANOT R. AND PESCHARD F.

.o

Figure 8.10. Ceramic similar to types from Amapa.

u

,..

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXIco 161

Figure 8.11.Culiacán Polychrome vase.

and a bowl with either straight or outflaring rims. They are usually mono-

chrome black, red, or buff, with a finely polished surface like those

reported from Culiacán and Guasave (Kelly1945: figure 66; Ekholm 1942:figure 15) (Figure 8.12).

There are numerous copper objects from El Cañón del Molino, mainly

bells of different shapes and sizes. According to the classification of

Pendergast, modified by Castillo(1980: 55-58), they belong to types1,3, 7,8, 12, 20,and 36. Type 8 is a bell with a Tláloc effigy; it has been reported

widely from northwestem México and in the southwestem United States.

There is also a type similar to those described from the well of sacrifices atChichén Itzá (Morley1980: 435).

Other bells are similar to those of type36 as reported from Cojumatlán,Michoacán (Lister 1949: 70), and Tarascan types are also present (Kelly

1986: 91).There are also pendants in the shape of bats and turtles, a deco-rated pectoral in the shape of a half-moon, a seal, rings, bracelets, and

~eedles. Severa! chains have on their ends a figure that in the codices is

ldentified as "solar rays" (Figure8.13). We have not found reference to

these kinds of chains in the literature consulted, but we have identified asimilar object in a photograph of Schroeder site material. An ear spool is

162 GANOT R. AND PESCHARD F.

Figure 8.12. Ceramic pipes similar to Sinaloa sites.

similar to those found at Guasave, Sinaloa; Hervideros, Durango;

Texrnelincán, Guerrero; and in Topia, Durango (Ekholm 1942: 98-99;

Ganot and Peschard 1985).

From the rescued bone remains (Peschard 1983), there are 37 skulls ofwhich 34 have clear evidence of intentional cranial deformation of the

tabular erect type in the fronto-occipital and the plano-occipital areas

(Figure 8.14: a, b). The degree of deformation varíes from slightly de-

formed to those that show an advanced degree of deformation. A great

number of skulls have plagiocrania. One of the crania has dental mutilation

of the superior and inferior incisors of the type A-2 and A-3 in the classifi-

cation of Fastlich and Romero (1951: figure 1; Romero 1970: 50-67)

(Figure 8.15). In subsequent studies we will make a comparative analysis of

epigenetic features of the crania from Cañón del Molino and those ofPacific coastal sites, searching for biological affinity.

The practice of cranial deformation and dental mutilation was commonin the cultures of western México, especially in the states of Nayarít and

Sinaloa (Meighan 1976: 187-200; Ekholm 1942: 119-120; Kelly 1945: 187-

CAÑÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANCO, MÉXICO 163

Figure 8.13. Copper artifacts.

198), in the Mixteca-Puebla and Tolteca cultures from central México

(López et al. 1970: 143-152; Acosta 1976: 157), but it was not a common

practice of the Chalchihuites people. Intentional cranial deformation has

been reported from different parts of Durango State; from El Zape (Brooks1981: 1-12), near Pueblo Nuevo (Peschard 1970), and San Miguel del

Cantil (Ganot and Peschard 1985).

Other Material

There are other materials of a more general distribution that are usually

found in sites of the Aztatlán Culture and may also be found in sites of

other cultures.There are, for example, rectangular shaped reworked pottery sherds, 3 X

2 cm in size, that have been described in Mayan Culture as counterweights

for fishing nets. This function may have been possible in Cañón del Molino

due to the presence of nearby Lake Santiaguillo (Figure 8.16). There are

paint palettes and polishing stones made of a dark, dense stone. The

surface of one is very finely polished and has remains of red pigment on

164 GANOT R. AND PESCHARDF.

Figure 8.14 (top}. Two crania with intentional deformation.

Figure 8.15 (bottom). Mutilated Incisors.

WÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANCO, MÉXIco-

I --_1CLNT1ME ..T~oG

Figure 8.16. Rectilinear workedsherds.

165

both faces (Figure 8.17). Stone discoidals and lava rings were also found.Most of the metates recovered are large and rectangular, but there areothers of smaller size with legs and decoration. There are also many stone

molcajetes of different sizes, bases, and shapes; one is decorated with a

serpent head similar to a Hohokam motif. Pestles are cylindrical and some

are in animal effigy formo There are many 3/4-grooved axes and hammer-

~tones similar to those found throughout the north and west of México and

in the southwestern United States. A few specimens of animal effigy axeswere recovered.

A very remarkable figure of stone, finely manufactured, represents aseated human figure and resembles one reported by Kelley from an altar at

Cerro de Moctehuma, Zacatecas. According to Kelley, it may be a repre-sentation of the Mesoamerican Fire God (Kelley 1963: 12-13). Similarsculptures have been reported from other sites in West México (Figure

8.~8). Other sculptures represent stylized animal figures, one of which~Flgure 8.19) has decorative motifs similar to one from the Templo Mayorin Tenochtitlán (López-Portillo et al. 1981: 254), and from a figure of the

166 GANOT R. AND PESCHARD F.

Figure 8.17. Stone palettes.

Codice Laud (Kingsborough 1964: 399 lamina XLI).The predominant type of projectile point is a large triangular blade with

a flat or slightly concave base and with notches near the base. this type hasbeen identified from Amapa, Nayarit (Meighan 1976: 400) and from thesouthwestern United States. Another common type is a large triangular

point with flat or convex sides and a straight or slightly concave base.

These specimens may been hafted as knives and are similar to the ones

found in the Coahuila Desert, of the Jora-Mayran complex (Taylor 1966:

85-86) (Figure 8.20a). Three arrow points that seem to be older and pos-

sibly from the Archaic, were found as an offering in a burial, and it is pos-

sible that they were collected and reused (Figure 8.20b, e, d). Anothercommon type are triangular with two lateral notches and occasionally with

a basal notch; this type is widely found in the desert area of northern

México and the southwest United States.Other material from El Cañón del Molino includes shell bracelets,

pendants in various forms, incised pectorals, and beads; stone pendants inthe shape of birds, mammals, and snakes (Figure 8.21); polished stones ofvarious sizes and shapes; an effigy stone incensario (Figure 8.22); and boneartifacts such as awls.

(;AÑ"ÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANCO, MÉXICO 167

Figure 8.18.Anthropomorphic stonesculpturethat may represent the Mesoamerican fire God.

There is a strong similarity between the stone, shell, and bond materialfrom El Cañón del Molino and the Hohokam (Gladwin et al. 1975: 101-156; Haury 1978: 273-321).

RELATIONSHlPS AND INTER-REGIONAL COMMUNICATION _

The sites with Aztatlán culture situated inland in northern Durango and

~ast of the Sierra Madre can be grouped in four regions. The first one is in

C e Valle del Guadiana, where the Schroeder, Navacoyán, La Breña, and

fi erro de la Cantera sites, and the others previously cited are located· theirsr ~o are found near the shores of the Rio Tunal. Ceramics and other

matenal found by Dr. Kelley in the Schroeder site are similar to material

from the Pacific coast sites and were initially considered to be intrusive

from Chametla, Sinaloa (Kelley and Winters(1960: 547-561).This material

includes decorated ceramics, pipes, spindle whorls, copper artifacts, and

clay figurines, which are similar to objects reported from Amapa, Nayarit.

We have classified some ceramic pieces as Tuxpan, Botadero Incised, and

Ixcuintia Polychrome from the Cerritos Phase of Amapa (Ganot and

Peschard 1985). Based on these comparative analyses then, we think thatthe Guadiana valley had a close relationship with Amapa, Nayarit, andChametla, Sinaloa.

The second region is located in the valley of Guatimapé, where the main

sites are Cañón del Molino and Canatlán. In the latter site were found red-

168 GANOT R. AND PESCHARD F.

Figure 8.19. Zoomorphic stone eJfi?:J·

CAJ'iÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXIco- 169

Figure 8.20. Flaked stone knives and projectile points found as burial offerings.

Figure 8.21. Small stone ornaments.

170 GANOT R. AND PESCHARDF.

Figure 8.22. Stone incense burner.

on-buff plates of the Lolandis type from Chametla (Ganot and Peschard

1985).In this northem regíon, and Cañón del Molino in particular, the rela-

tionship was strongest with Guasave, Culiacán, and Tacuichamona, Sinaloa.

The third región includes Hervideros, near the city of Santiago Papa-

squiaro. Here, Guasave Red-on-buff, Culiacán Polychrorne, copper objects

and globular spindIe whorls have been reported (Mason1971: 137-138).The fourth regíon includes the sites of Tepehuanes and El Zape. Ixcuintla

Polychrome and Guasave Red-on-buff, as well as spindIe whorls, burial

urns, and copper bells, have been described from El Zape (Mason1971:138-140; Ganot and Peschard1985).

Donald D. Brand was the first to describe material from the coast in the

north of Durango and suggested contact between these cultures via the

courses of the rivers that cross the Sierra Madre Occidental. Kelley has

proposed that prehispanic trade routes existed between core Mesoamerica,the cultures of the Nayarit-Sinaloa area, and Durango (Kelley1974: 19-34).As possible routes of access to inland southeast Durango, we have pro-posed the rivers San Pedro del Mezquital and Acaponeta; both origínate inDurango and end at the Pacific Ocean in Nayarit.

The Tunal, La Sauceda, and Santiago Bayacora rivers form the Rio

CAÑÓN DEL MOLINO, DURANGO, MÉXIco- 171

Durango, which is the main tributary of the Rio San Pedro del Mezquital.As previously mentioned, the sites of Shroeder and Navacoyán are near the

Rio Tunal, and the site of Canatlán is near the Rio La Sauceda. Most of the

important sites of the Guadiana Valley are located near these rivers.Another archaeologícal site in proximity to the Rio San Pedro is Cerro

Bola, near the city of El Mezquital, some80 km south of Durango. There

we have found many decorated sherds of Otinapa, Nevería, and Madero

Engraved from the Calera and Tunal phases of the Guadiana Branch of the

Chalchihuites culture, as well as a vessel support with a painted serpent

that seems to be intrusive from the coastal cultures.

The Acaponeta River begins approximately50 km southwest of Durango,

on the plateau of Navios and Navajas, where there are obsidian mines and

prehispanic lithic workshops. Down the river near the town of PuebloNuevo, a skull with tabular oblique cranial deformation was found

(Peschard 1970). This river ends in the Marismas Nacionales, Nayarit,where the archaeological regíon of Aztatlán is located. Topographically,

this river seems to be more accessible as a route of communication with

the coast. At the end of the last century, for example, there existed a horse

road that joined the towns of Rosario, Sinaloa, and Acaponeta, Nayarit,with the city of Durango.

In the north of Durango, the routes of communication with the coast are

probably the courses of the San Lorenzo and Culiacán rivers, which have as

tributaries the Humaya and Tamazula rivers near the mountains of Topia.

On ancient maps there are descriptions of routes following the margins of

these rivers, joining the towns of Topia, Tamazula, Tepehuanes, and Santi-

ago Papasquiaro, Durango, with Culiacán, Sinaloa. These routes were used

by Francisco de Ibarra and the Jesuit missionaries during the conquest. In acave near the Rio San Lorenzo, Dr. Raúl Garza-Limón found two skulls

with intentional cranial deformation, probably of the tabular erect type.

Recently, in the town of Pinos, near the river of Valle de Topia, a tributary

of .the Humaya, several copper bells and an earspool similar to one de-

scnbed by Ekholm from Guasave, were found (Ganot and Peschard1985).North to El Cañón del Molino, the sites of Hervideros, Tepehuanes,

S~ta Ana, and el Zape are located, with evidence of Mesoamerican occu-

patIon. Recently we had the opportunity of analyzing some photographs ofglobul . dID ar spm e whorls found on a farm near Santa María del Oro,

Urango. From here to Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, there is a vast and

hoorly explored territory where no other sites similar to those reportedere have been described (Figure8.23).

172 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARDF.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ----

The archeological site of El Cañón del Molino is one of several irnportant

sites located in a very extensive and poorly studied area between what is

considered the northern limit of Mesoarnerica and the Southwest United

States. The analysis of the material enables us to state that it was an

important interaction center for the various cultures that were located here

contemporaneously; the Chalchihuites, the Aztatlán, the Loma San Gabriel,

and the ]ora-Mayran complex of the Coahuila Desert. Beyond this, it must

be seriously considered as a potential link to the cultures of the southwest-

ern United States, with communication routes extending from central

Mesoarnerica to the Pacific coast, and from there along the river courses

through the Sierra Madre Occidental to the plateau of northern Durango,

and to Casas Grandes, and to southwestern United States, following theplains east of the Sierra Madre Occidental.

A great number of features of the Aztatlán Culture are present in ElCañón del Molino and it is clear that settlers of this culture lived in this

part of Durango for a long period of time. We have noted that there areseveral other places with a similar pattern in Durango, which makes it clear

that settlers with this culture in fact lived here in the Post-Classic Period,

possibly until Spanish contacto This is the first site of Aztatlán culture

reported inland on the northern plateau of México. The effect on the

Chalchihuites pottery here was so great, in fact, that a new mixed red-on-

crearn type developed.

In association with Aztatlán and Chalchihuites pottery, there is a great

quantity of vessels somewhat similar to the latter, but roughly elaborated

and decorated. These have been identified as Loma San Gabriel, but we

doubt that they were actually manufactured by people with this culture or

by less skilled Chalchihuites craftsmen for the use of marginal groups.

Until now, the study of the cultures of western México, especially those

of the coast of Nayarit and Sinaloa, has been carried out by isolated inves-tigations of sites. Conclusions have been based almost exclusively on

cerarnics, differently designated at each site. This fact has made impossiblea comparison of these cultures, and in the future a systematic restudy andreclassification of all of this material will be necessary to identify local vari-

ations of each type or combinations thereof, in order to achieve an

adequate understanding of the cultures involved.

In El Cañón del Molino collections there are various objects with Gods

representations, such as cerarnic designs representing Tláloc, Huehueteotl,

C!J'IÓN DEL MOUNO, DURANGO, MÉXICO.:---

CHIHUAHUA

}___.i__

IIr,!

.-\ .'..•. ,,{.r·...·

NAYARIT

173

CAS

1. Nicolás Romero2. Valle Florido3. Puerta de la Cantera4. Shroeder5. Navacoyán6. La Breña7. Morcillo8. Cacaria9. Canatlán10. Flores Magón11. Cerro del Oso12. Antonio Amaro13. El Cañón del Molino14. Hervideros15. Tepehuanes16. El Zape17. Valle de Topia18. San Miguel del Cant iI19. Cerro Bola

Figure 8.23. Possible routes o/ exchange and interaction.

Quelzalcóatl, and others. Kelley has also described a pottery ware with re-

presentations of Gods from the Aztec pantheon. These data establish the

presence of a Mesoarnerican religious pattern at El Cañón del Molino, and

one that is also found to the north at Casas Grandes.

It is important to analyze the geographic distribution of the copper

material, which does not seem to come from the Tarascan area, except for

some bells. Its distribution seems to follow a route bordering the Pacificcoast from southern México and Central América to Cañón del Molino,

Casas Grandes, and the southwestern United States, and we consider these

174 GANOT R. ANO PESCHARD F.

objects as important trade material. The relationship with Casas Grandesand the South~est of the United States is based on the similarity between

~ome sto~e objects, copper, Chalchihuites-type spindle whorls, paired holesm vessel nms, effigy bowls, and probably some ceramic decorative motifs.

The cultural traits of cranial deforrnation in the tabular erect form and

dental mutilation also seem to be characteristic of late cultures from west

México, the Mixteca-Puebla and the Tolteca regions. Further studies of bio-

logical affinity will yield important information about the origin and move-

ments ofthe groups involved in the settlement ofWest and North México.

The fin~ngs described here demonstrate the wide mobility of groups ofMesoamencan culture from Central América to the southwestern United

States. Thus it is difficult at this time to establish territorial limits of the

cultures involved in the settlement of this region, including the north and

west of México, in the Post-Classic.

ACKNO~GMENTS--------

In such a large period of having been working in this paper, we have a large

number of people to whom we are very grateful, all of them have had animportant role in this final documento Rafael Betancourt and his family

and Alfonso Barraza, from Esfuerzos Unidos, Cuatímapé, who guided us

all over the región, Dr. J. Charles Kelley and his wife Ellen A. Kelley, Gloria

Fenner, and Georgina Violan te de Ganot, translated and edited thefinal

documento Lic. José Hugo Martínez Ortíz, Ex-Rector of the Universidad

Juaréz del Estado de Durango, Mr. Juan Leautaud C. and his wife Magda-

lena, and Mr. Eduardo León de la Peña and his wifeMaría Luisa, all of

them very interested in .the History of Durango, and whose valuable booksenriched this paper. We also thank Dr. Elías Humberto Avila R. for his

kind assistance in the final revision and correction of this work, as well as

Mrs. ~mma Saenz de Peschard for her assistance with the photographicmatenal.

Works CitedAcost.a..:J. R. 1976. Los Toltecas. InLos Señoriosy Estados Militaristas.Román

Pl~a~Chan coordinator. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e HistoriaMéxico, '

Barlow, R. H., and T. S. George, (translators) 1943.Nombre de Dios DurangoDocun:entos en Náhuatl Concernientes a su Fundaci6n.Edited by fue la Cas~de Tláloc. Sacramento, California.

175~ÓN DEL MoLINO, DURANCO, MÉXIco

~d D. 1971. Geography and Archaeology of Zape, Durango. InThe

BranN~rthMexican Frontier,edited by B. C. Hedrick.j. C. Kelley, and C. L.Rilley.Reprinted, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

ooks. S. T. and R. H. Brooks 1980.Cranial Deformation: PossibleEvidence ofBr pochteca Trading M~ts. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy

of Science 72(3). Spnngfie!d.Castillo T. N. 1980. Distribución Espacial de Objetos de Metal. Base de un

In~nto de Clasificación. InRutasde Intercambio en Mesoamérica y Norte deMéxico. XVI Mesa Redonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología,

Saltillo.Ekholm, G.R. 1942.Excavations at Guasave, Sinaloa; México.Anthropological

Papers of the American Museum ofNatural History, no. 38 New York.Fastlich, S. andj. Romero 1951. El Arte de las Mutilaciones Dentarias.

Enciclopedia Mexicana de Arte,vol. XIV. México.Foster, M. S. 1978. Loma San Gabrie!: A Prehistoric Culture of Northwest

México. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Colorado, Boulder.___ 1985. The Loma San Gabrie! Occupation of Zacatecas and Durango,

México. In Archaeolog;yof West and Northwest Mesoamerica,edited byMichae!S. Foster and Phil C. Weigand. Westview Press, Boulder.

Glassow, M. A. 1967. The Ceramics of Huistla, a West Mexican Site in TheMunicipality of Etzatlán, Jalisco.American Antiquity 32.

Gifford, E. W. 1950.Susface Archaeology of Ixtlán del Río, Nayarit.Universityof California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol.43, no.2, Berke!ey.

Ganot, R.J. A. Peschard F., andj. Lazalde F. 1983. Re!ación Prehispanicaentre las Culturas de! Noroeste de México y e! Sitio Arqueológico ElCañón del Molino, en el Estado de Durango. Paper presented at theXVIII Mesa Redonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, Taxco,México.

Ganot R.j., and A. Peschard F. 1985. La Cultura Aztatlán, Frontera de!Occidente y Norte de Mesoamérica en e! Post-Clásico. Paper presentedat the XIX Mesa Redonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología,Querétaro, México.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. (INEGI) 1982.Atlas Cartográjico Histórico.(INEGI), Secretaría de Programación y Pre-supuesto, México.

jimenez-Moreno W. 1975. Mesoamerica. InEnciclopedia de México,vol. 8.Impresora y Editora Mexicana, México.

Kel\ey,j. C. 1956. Settlement Patterns In North-Central México. InPre-h~t~ric Settlement Patterns in the New World,edited by Gordon R. Willey.Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, no. 23, New York.

--;: 1963. Northern Frontier of Mesoamerica. First Annual Report:ugust, 1961; August, 1962. Carbondale, Illinois.

~ ~966. Me~oamerica and the Southweste~ United States. InArchaeo-gical Frontiers and Extemal Connection,edited by Gordon F. Ekholm

and Cordon R. Willey. Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 4,

176 CANOT R ANDPESCHARDF. ~~~M~O~UN~O~,~D__URANG_O~,_M_IDa__ C_O 17_7CAJ'!ÓN D _::::.--

Antropología Física. InProyecto Cholula.Serie Investigaciones, vol. 19,

lacio Marquina coordinator, Instituto Nacional de Antropología egn . M'·Histona, eXlCO.

1971. Late Archaeological Sites in Durango, México From Chal---:hihuites to Zape. InThe North MexicanFrontier, edited by B. C. Hedrick,

J. C. Kelley, and C. L. Riley. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbon-

dale-Mecham,J. L. 1927.Francisco de [barra and Nueva Vizcaya.Duke University

Press. Durham.Meighan, C. W. 1976.The .Archaeologyo/ Amapa, l'!aya~t. Mon';lme~ta

Archaeologica: 2. The Institute of Archaeology, University of California,Los Angeles.

Meighan, C. W. and L.J. Foote 1968.~r:ations atoTizapán el Alto, Jalisco.Latín American Studies, vol. 11, University of California, Los Angeles.

Morley, S. C. 1980.La Civilizacion Maya. Fondo de Cultura Económica.México.

Mota y Escobar, A. de la 1940 [1602-1605].Descripción Geografica de losReinos de Nueva Galicia, Nueva Vizcaya y Nuevo León.Editorial PedroRobredo, México.

Mountjoy,J. B. 1982.Proyecto Tomatlán de Salvamento Arqueológico.ColecciónCientífica: Arqueología, 122. Centro Regional de Occidente, InstitutoNacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

Muller, E. F. 1948. Cerámica de la Cuenca del Rio Lenna. InEl Occidente deMéxico. Cuarta Reunión de Mesa Redonda sobre ProblemasAntropológicos de México y Centro América. México.

Obregón, B. D. 1924 [1584].Historia de los Descubrimientos Antiguos Modernosde la Nueva España,escrita por el Conquistador Baltazar de Obregón,Secretaría de Educación Pública. México.

Oliveras, J. 1976.Los Señoríos y Estados Militaristas,citing W. jiménezMoreno in chapter, Nayarit. Instituto Nacional de Antropología eHistoria, México.

Peschard, F. A. 1970. La Deformación Craneana Intencional en el Estado deDurango. Tesis Recepcional, Escuela de Medicina. Universidad juárezdel Estado de Durango. México.

- 1983. Restos Oseos del Cañón del Molino, Durango. Paper presentedat XVIII Mesa Redonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología,Taxco, México.

Peschard, F. A.,J. CanotR, andJ. Lazalde F. 1986.Influencias Externas en laCerámica Chalchihuita de la Rama Guadiana. Homenaje al DoctorJ CharlesKelley. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

Peschard, F. A. and J. CanotR 1990. El Postclásico Tardio en el Estado deDurango. In El Final del México Antiguo. Museo Nacional deAntropología, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

Rom~ro, J. 1970. Dental Mutilation, Trephination, and Cranial Deforma-non. In Handhook o/ Middle American Indians,T. Dale Stewart, editor,vol. 9.

Robert Wauchope, general editor. University ofTexas Press, Austin.

---- 1971. Archaeology of the Northern Frontier: Zacatecas and Durango.In Archaeologyo/Mesoamerica,part two, edited by Cordon F. Ekholn andIgnacio Bernal. Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 11, RobertWauchope, general editor. University ofTexas Press, Austin.

---- 1974. Speculations on the Culture History of NorthwesternMesoamerica. InThe Archaeologyo/ West México, edited by Betty Bell.West Mexican Society for Advanced Studies. Ajijic,Jalisco, México.

---- 1983. Hypothetical Functioning of the Major Postclassic Trade Systemof West and Northwest Mexico. Paper presented at the XVIII MesaRedonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología. Taxco. México.

-- 1985a. The Mobile Merchants of Molino. Paper presented at the XIXMesa Redonda de la Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología, Querétaro,México.

-- 1985b. The Chronology of Chalchihuites Culture. InArchaeologyo/West and Northwest Mesoamerica,edited by Michael S. Foster and Phil C.Weigand. WestviewPress, Boulder.

-- 1986. The Mobile Merchants of Molino. InRipples in the ChichimecSea,edited by Frances joan Mathien and Randall H. McCuire. Southernlllinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville.

-- 1990. The Early Post-Classic in Northern Zacatecas and Durango IXto XII Centuries. InMesoamerica y Norte de México siglo IX-XII,vol. 2.Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

-- 1990.El Postclasico Temprano en el Estado de Durango in Mesoamerica yNorte de México Siglo IX-XII, vol. 2. Instituto Nacional de Antropología eHistoria, México.

Kelley, J. C. and H. D. Winters 1960. A Revision of the ArchaeologicalSequence in Sinaloa Mexico.American Antiquity 25(4).

Kelly, 1. 1938.Excavations at Chametla, Sinaloa.Ibero-Americana: 14. Univer-sity ofCalifornia Press. Berkeley.

-- 1945.Excavations at Culiacan; Sinaloa.Ibero-Americana: 25. UniversityofCalifornia Press, Berkeley.

-- 1948. Ceramic Provinces of Northwest México. InEl Occidente deMéxico, Cuarta Reunión de Mesa Redonda sobre ProblemasAntropológicos de México y Centro América. Cuernavaca, Morelos,México.

Lazalde,J. F., A. Peschard F. and J. CanotR 1983. Arte Rupestre del Vallede Cuatimapé, Durango. Documentos Sobre Rocas, Manuscript,Durango.

Lister, R 1949.Excavations at Cojumatlán, Michoacén; México.University ofNew México Publications in Anthropology, no. 5, Albuquerque.

Lopez-~ortillo, J., M. Leon-Portilla, and E. Matos. 1981.El Templo Mayor.Editado por Bancómer, México.

Kingsborough, 1. 1964.Antiguedades de México.Códice Laud, vol. ill. Secre-taría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (SHCP), México.

López, A.S., Z. LagunasR, and C. Serrano S. 1970. Sección de

178 GANOT R. AND PESCHARD F.

Sauer, D.and D. Brand 1932.Aztatlán: Prehistoric Mexican Frontier on thePacific Coast. Ibero-Americana 5. University of California Press,Berkeley.

Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto (SPP) 1971.Carta topográfica 1:50000-SPP. México, D.F.

Scott, S. D. 1974. Archaeology and the Estuary: Researching Prehistory andPaleoecology in the Marismas Nacionales, Sinaloa and Nayarit, México.In The Archaeolog;y01 West México, edited by Betty Bell. Sociedad deEstudios Avanzados del Occidente de México, A.C. Ajijic,México.

Taylor, W. W. 1966. Archaic Cultures Adjacent to the Northeastern Fron-tiers of Mesoamérica. InArchaeological Frontiers and Extemal Connections,edited by Gordon F. Ekholm and Gordon R. Willey. Handbook ofMiddle American Indians, vol. 4, Robert Wauchope, general editor.University ofTexas Press, Austin.