Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site, A Southeastern Utah Great House

Transcript of Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site, A Southeastern Utah Great House

INSTRUCTIONS FOR AUTHORS

Kiva publishes high-quality synthetic and data-oriented articles concerning all aspects of the human occupation of the Southwest (broadly defined). Papers may relate to any aspect of Anthropology; Archaeology; History, and Ethnology in the prehistoric or historic southwestern United States or northern Mexico. Papers should be previously unpublished, contain fewer than 9000 words, and conform to American Antiquity and Kiva style. Longer submissions and guest-edited "theme issues" will be considered for publication after preliminary consultation with the Editor. The journal also contains book reviews and book notes on recent academic and contract-related publications. All manuscripts are reviewed by scholars familiar with the subject matter. The Editor reserves the right to evaluate manuscripts (with or without peer review) for appropriate subject matter, quality, length, and compliance with· style guides. Manuscripts may be returned to authors if they fail to meet expectations or conform to the guidelines. The Editor has final responsibility for all decisions regarding manuscripts. Published papers become the copyright of Kiva and the Society.

MANUSCRIPTS. Manuscripts must be typed, double-spaced, on one side of 81h x 11 inch bond paper. An original and two copies must be submitted, each accompanied by photocopies of all illustrations. Manuscripts should be paginated consecutively beginning with the title page. Content of the paper should be indicated by appropriate headings and subheadings. A brief abstract (in both English and Spanish) of 100 to 150 words must accompany the paper. If this is not possible, we will translate the abstract for a small fee. The listing of references should include only those cited in the text. Accepted manuscripts must have their text made available in electronic format as word-processed, Windows-based files. Delivery may be by disk, 100 MB zip disk, CDROM, or via email attachment. Do not send electronically formatted manuscripts until requested.

TABLES, FIGURES, AND ILLUSTRATIONS. Kiva printed pages are 6 x 9 inches with 1/2 inch border on all sides. Authors should scale photographs and line art to a 5:8 ratio. Line drawings should be drawn in black ink no larger than 9 x 12 inches and be suitable for 50% reduction. All figures and tables must be cited in the text, be numbered consecutively, and have descriptive titles. Each figure should be labeled on the back with the author's name and the figure number. The space used by photographs, line art, and tables is included in the page allowance for manuscript length. Authors are requested to keep all original illustrations until these materials are requested by the Editor. Kiva is not responsible for lost or damaged artwork. Authors are responsible for obtaining permission from copyright holders for reproducing illustrations, maps, tables, figures, or lengthy quotations previously published elsewhere.

GALLEY PROOFS AND OFFPRINTS. Galley proofs only will be sent to authors. Proofs should be read, corrected, and returned to the Editor within 48 hours of receipt. Minor alterations of the text in galley proofs are permitted, but major alterations will be charged to the author. The author( s) of each article will receive 2 complimentary copies of the Kiva issue in which the paper appears and permission to photocopy a fixed number of additional copies of the article for circulation to professional colleagues. In the event that there are two or more authors of an article, each co-author will receive one complimentary issue. ·

STYLE. Manuscripts should be prepared according to the Style Guide for American Antiquity (57(4):749-770, or http://www.saa.org/publications/StyleGuide/styframe.htrnl), and to The Chicago Manual of Style (14th ed., University of Chicago Press, 1993). Manuscripts submitted in an inappropriate style will be returned.

BOOK REVIEWS: Books for review on topics of interest to subscribers of the journal should be sent to the Editor, address below. Those interested in reviewing books for the journal should contact the editor prior to submitting a review.

CORRESPONDENCE. Correspondence concerning manuscripts should be addressed to the Editor of Kiva, Ron Towner, Arizona State Museum, P.O. Box 210026, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0026. E-mail address: [email protected]

SURFACE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE RED KNOBS SITE, A SOUTHEASTERN UTAH GREAT HOUSE

James R. Allison

ABSTRACT Red Knobs is a large Anasazi site in southeastern Utah. It was a community center

twice-first around AD. 900, then again in the early to mid-llOOs. The later occu

pation incorporated some of the architectural symbolism associated with Cha

coan great houses, including a great kiva and a prehistoric road. Other

characteristics, including having been built on top of an earlier community cen

ter, seem symbolic but are not dearly Chacoan. Also, ceramics suggest substantial

local production with economic ties strongest to the southwest rather than the

southeast toward Chaco or Aztec. It appears that connections to Chaco, if any;

were relatively indirect. Other southeastern Utah great houses are highly variable,

but share both the Chacoan architectural symbolism and the tendency to be

located on the ruins of large, late Pueblo I villages. This suggests attempts to evoke

connections both to the large, distant Chacoan centers and to local precursors.

RESUMEN

Red Knobs (Mesitas Rojas) es un gran pueblo Anasazi en el sureste de Utah. Pue un cen

tro de comunidad dos veces-La primera vez, approximadamente 900 d.C, y la otra vez

durante el siglo doce. La gente que vivfa durante los afios 1100 d. C. incorporaron sim

bolismo arquitect6nico asociado con las casas grandes de Chaco, incluso un gran kiva y

un camino prehist6rico. Otras caraterfsticas, incluso la construcci6n encima de un centro

de communidad anterior, se parece simb6lico pero no son Chaquefio. Tambien, los

cerdmicos indican substancial producci6n local, con conexi6nes hasta el suroeste, y no al

sureste y Chaco o Aztec. Se parece que los conexi6nes con Chaco, si existiearon, fueron

indirectos. Otros casas grandes del sureste de Utah son muy variable, pero comparte el simbolismo arquitect6nico de Chaco y la inclinaci6n de encontrarse en ruinas de un gran

aldea de Pueblo I. Esto sugiere tentativas de evocar las conexi6nes ambas a los centros grandes, distantes de Chaco y a los precursores locales.

KIVA: The Journal of Southwestern Archaeology and History, Vol. 69, No. 4, (Summer 2004), pp. 339-360. Copyright © 2004 Arizona Historical and Archaeological Society. All rights reserved.

339

340 James R. Allison

R ed Knobs ( 42SA259) is one of the largestAnasazi sites in southeastern Utah. It has a great kiva associated with nine roomblocks, several of

which are potentially small great houses. Despite its size and potential importance to understandings of Anasazi prehistory in southeastern Utah and beyond, it is little lmown. The main purpose of this article is to describe the surface archaeology of the site1 , focusing mainly on the late-Chacoan era occupation. The Red Knobs site, however, like other great houses on the fringes of the Chacoan system, has some non-Chacoan characteristics. These include the small possible great houses, and its location on the ruins of a large earlier village that dates to around A.D. 900. It also lacks evidence of strong economic ties to Chaco. These characteristics, along with those of other nearby great house sites, demonstrate that southeastern Utah great houses varied in many details, including size and the degree to which they display the architectural symbolism associated with great houses in the San Juan Basin. Thus, an important subtext to this article, only discussed explicitly at the end, is what the unique aspects of the site, and those of nearby great houses, may imply about the roles these sites played in local and regional socioeconomic systems.

Red Knobs is located in Cottonwood Wash, 15 km west of the town of Blanding and near several great house sites that have recently been described: the Cottonwood Falls great house (Mahoney 2000), also in Cottonwood Wash, about 10 km downstream from Red Knobs; the Bluff great house (Jalbert and

\i \ ~ ·~'?:>,._ \ '%,

•Monticello 1 '·\_ i 'ii \ -:z. l~ontezuma:village 'll..

Red Knobs.I. .. ~ Edge of the c_edars ~ A 1 H 11 , \'='" ._Blanding ; _,./~f-Jedlel;'/ • nse ~a

Owen Arch ' •.cottonwood Falls·,· _,..... ,' .! •Lowry • Canyonl. -...

•Black Mesa ·,./ • / Comb Wash•! 1 •; •Yellow Jacket

( i l. > ,. •Albert Porter \...• , j \..N.~.C?:!'. Patterson Dolores

f I : ? I : I .J C ( _.J / / • asa Negra i \ ,..-· •Cortez

Bluff Great House Bluff ( McElmo Creek

/ •Yucca House

MapAreaffi t •Modern Town N •Great House Site , __ _

o kilometers 25

Mesa Verde

New Mexico

Figure 1. Map of the Mesa Verde region showing the location of Red Knobs, other locations mentioned in the text, and selected sites with great houses.

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 341

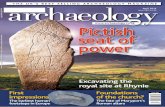

Cameron 2000) at the mouth of Cottonwood Wash, about 40 km downstream; and Edge of the Cedars (Hurst 2000) located 15 km to the east (Figure 1). Red Knobs was occupied intensively during two distinct time periods: first around A.D. 900, then again in the 1100s. Architectural features from the later occupation include a large great kiva, a short segment of a prehistoric road, and nine distinct rubble mounds located around and on top of two red-sandstone "lmobs" (Figure 2). These lmobs are flat-topped remnants ofEntrada sandstone about 8-10 m high. There is additional rubble on the slope around the lmobs; some of this comes from the structures on top of the lmobs, but there probably are also rooms dating to the later occupation in the rubble surrounding the lmobs.

Red Knobs has been lmown to archaeologists since at least 1956, when James Gunnerson filled out a one page site form after what was apparently a cursory visit-judging by the description on the form, he probably only saw the eastern end of the site. The first mention of the site in the archaeological literature was by Hurst (1992), who described it then as a possible great house site. Varien et al. (1996) included it in their summary oflarge Mesa Verde region sites. It appears there and in Varien (1999) as a community center with more than 200 structures that dates to the post-Chacoan period, after A.D. 1150. Those estimates of site size and dating were based on brief walkovers of the site; they are not unreasonable, but the site was probably not quite that large. Also, despite the

Figure 2. View of Red Knobs (42SA 259), facing northeast from about 600 m away.

.

'

1\ : 1, !/

/

342 James R. Allison

multi-roomblock layout, which is more typical ofa post-1150 community center, ceramics indicate that much of the construction and occupation of the later village occurred prior to A.D. 1150.

Red Knobs is dearly a great house site, at least by some definitions, although it has a number of ambiguous characteristics and, like other nearby great house sites (Hurst 2000; Jalbert and Cameron 2000; Mahoney 2000), it has a strongly local character. The site incorporates some of the architectural symbolism associated with Chaco, but the ceramics show little evidence of trade from the San Juan Basin. Also, the location on top of the earlier village may have been a deliberate symbolic act expressing a connection with local ancestral populations.

THE A.D. 11 OOS VILLAGE

Site Size and Layout

The later village at Red Knobs includes nine distinct rubble mounds (Figure 3). There is a mound on top of each of the sandstone knobs (Figures 4-5); the others extend from just north of the eastern knob west-southwest for almost 300 m. The great kiva is about 50 m southwest of the westernmost rubble mound, adj a-

D Rubble Mound ~ • Kiva Depression / Steep Drop-Off c::) Probable Rubble -O meters 50

Wall Alignment 5

Q Western Knob

c{!} 1

8 Great Kiva e ~o ~

Figure 3. Map of Red Knobs (42SA259).

4 10 G.\o ~

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 343

Figure 4. East-facing view of the eastern knob, taken from on top of the western knob.

Figure 5. West-facing view of the western knob, taken from on top of the eastern knob.

344 James R. Allison

cent to what appears to be a short segment of a prehistoric road. The kiva depression is about 24 m in diameter, and 1.15 m deep, while the road segment is about 1 m deep and widens from about 8 m to almost 20 m as it approaches the great kiva. The road can only be followed for about 40 m from the great kiva before it disappears on the eroded slope southwest of the site, but it probably ties into a lmown prehistoric road that has been traced to a saddle at the top of the slope, about 1 km southwest of the site (Severance 1999). There is also a swale along the west side of the western Imob that may be another short road segment, possibly with an artificial berm lining its western side, although it is also possible that this is a natural feature.

Fifteen small kiva depressions are evident on the site. The smallest of the rubble mounds has no associated depression, but the others have from one to three kiva depressions each. Other rooms are more difficult to discern from the surface evidence (only a few wall alignments are visible), so their number has to be estimated. According to one convention developed for similar sites (Varien et al. 1996:89), multiplying the number ofkiva depressions by six gives a conservative estimate of the number of surface rooms present. In the case of Red Knobs, this would give an estimate of 90 surface rooms; with the kivas that would make about 105 total rooms in the rubble mounds. This is probably too conservative an estimate. Considering the size and possible configuration of rooms within each rubble mound, I developed various estimates ranging from about 90 to 175 surface rooms in the rubble mounds, but am most comfortable with an estimate of 115 (Table 1 ). The wide range of estimates results from a number of ambiguities about the sizes of rooms, whether kivas in two of the mounds are blocked in by rooms or just single walls on their south sides, and whether parts of some of the mounds are multistory or simply tall single-story structures.

In addition to the rooms in definable rubble mounds, there are almost certainly rooms in the rubble around the bases of the Imobs, although it is difficult to determine how much of this rubble has fallen from above and how much represents the locations of other rooms. Both lmobs are surrounded by rubble, and there could be a large number of rooms hidden there. There is an especially large amount of rubble on the south side of the eastern lmob, which clearly includes some rooms, although the nature of the rubble and associated ceramics suggest that most of the rooms there belong to the earlier occupation. Estimating room numbers for the amorphous rubble around the lmobs is even more difficult than for the mounds, but 20-30 rooms is probably a reasonable estimate of the actual number of rooms there.

To summarize, it is difficult to say exactly how many rooms there are on the site from the surface evidence. Estimates using a variety of plausible assumptions range from a minimum of 105 to a maximum of more than 240, but most likely the A.D. 1100s village comprised about 150 rooms, including the kivas.

+..l c Q) c g_ E 8 Ill 0 0 ..... ..... ci <( Q)

.s:: -,__

.8 ~ 1ii E

~ -c :J 0 (.)

E 8 a: ....:

0 ~ 0 0 0 ~ 0 0 0

0 0 0

00 I

0 0 0 0

0 0 l""""I Cf') Lt) \D ('()

I I I I I \OOOC'flrnN .....

0 .....

ll"l N

I 0

0

0

0 .....

ll"l N

I 0

0

0 00

~ ('() I

0 0

N ll"l O'\ N .-<

I I 00 0

O'\

/

346 James R. Allison

Where Is the Great House?

One problem with considering Red Knobs to be a great house site is the multiroomblock layout. Some nearby great house sites, such as Cottonwood Falls and Bluff (Jalbert and Cameron 2000; Mahoney 2000), are relatively unproblematic; they contain a single large roomblock with at least some typical great house characteristics such as blocked-in kivas. Another nearby great house site, Edge of the Cedars, has a multi-roomblock layout like Red Knobs, but there it is clear from excavation data that the roomblock adjacent to the great kiva has typical great house features including blocked-in, above-grade kivas and banded core-andveneer masonry. It is also clearly distinct from the surrounding structures. At Red Knobs, five of the nine roomblocks are small unit pueblo-like structures. The other four buildings, however, are all distinct in some way, and each could have been a small great house. All four of these structures are larger than the apparent great house at Edge of the Cedars, and are within the size range of the smaller great houses illustrated by Lekson (1991 ), but they are much smaller than the nearby great houses at Bluff and Cottonwood Falls.

Two of these larger structures are on top of the sandstone knobs. The structure on the eastern knob measures about 29 by 22 m, and has two kiva depressions surrounded by rubble. The building on the western knob is slightly larger, measuring about 31 x 22 m, and encloses three kiva depressions. Because

Figure 6. Holes ground into the sandstone bedrock on the western knob.

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 347

there is little soil deposition, all of the kivas on the knobs were probably built at least partially above grade. Around the edge of both knobs there are a number of small holes pecked into the sandstone (Figure 6). Although the arrangement of the holes is not continuous, most of them appear to be post sockets for palisades that partially or completely surrounded each of the knobs. A room on the western knob was vandalized in the late 1990s, providing the only glimpse thus far of intact masonry on the site (Figure 7). The exposed wall has masonry that is somewhat banded, but it is not clear whether the wall had core-andveneer construction. Arguing against interpreting either of these structures as a great house is the moderate height of the rubble, which suggests they were, for the most part, single-story buildings. The western knob, however, has some rubble high enough to suggest parts of it were two stories high. Even if these buildings prove not to be great houses in the usual sense, they are clearly differentiated from the others on the site by their prominent locations 8-10 m above the other buildings.

The other two structures that could be great houses are located next to each other southwest of the western knob (Roomblocks 1 and 2 on Figure 3). Roomblock 2 is the largest in area, measuring 34 by 23 m, whereas Roomblock 1 is about 28 by 23 m. Roomblock 2 has three kiva depressions that are built above grade and blocked in by what appears to be a single wall on their south (downslope) side. Similarly, Roomblock 1 has two kivas, clearly built above grade. There

Figure 7. Masonry exposed in vandalized room on the western knob.

/

348 James R. Allison

is more rubble south of the Roomblock 1 depressions, so there may have been rooms rather than just a single wall south of the kivas there. On both of these structures, the rubble rises higher to the north above the kiva depressions, although this effect is in part due to the slope.

Roomblock 1 is north of Roomblock 2, and sits at the top of the slope above it. When approached from the south or southwest (i.e., from the direction of the great kiva), the Roomblock 1 rubble mound rises dramatically, and it appears to be a taller and more impressive building than Roomblock 2. For these reasons, Roomblock 1 is probably the most likely candidate for the great house, if there is only one such building on the site.

When viewed from the north side, however, the Roomblock 1 rubble is quite low, less than 1 m high; the builders used the slope to make the structure appear more impressive. The Cottonwood Falls great house uses a similar technique on a larger scale. There too, the rubble mound rises dramatically when approached from the southern, downslope side that faces the great kiva, but it is much less impressive from the north side.

At Red Knobs, there are four structures that could be interpreted as small great houses. Any one of them would probably be recognized on surface evidence alone as a candidate for a small great house, if it were the only roomblock associated with the great kiva and road. With four such structures, however, none of them stands out as much as they would if the other rubble mounds on the site were all unit pueblo-like buildings. Of the four, Roomblock 1 appears the most like other structures that have been interpreted as great houses. The structures on the knobs seem less likely to be great houses in the usual sense, but they stand out because of their location, and they certainly do not look like ordinary residences.

Ceramic Dating

The ceramic collections from Red Knobs include a mixture of types from the early and late occupations, including types that date from the Basketmaker III through Pueblo III periods (Breternitz et al. 1974; Wilson and Blinman 1995, 1999). From the ceramic types present, it might be argued that the site was occupied continuously from at least the A.D. 700s into the early 1200s; it may in fact have had some occupation throughout this time, but careful consideration of the ceramic frequencies suggests that most use of the site occurred in two distinct periods. The first was around A.D. 900 in the terminal Pueblo I or very early Pueblo II period, the second in the late Pueblo II and/or early Pueblo III period. The site probably was not occupied, or only very lightly used, from about A.D. 950 to A.D. 1050 or 1100.

Most of the ceramics can be segregated into early types, which date before about A.D. 950, and late types that probably date after about A.D. 1050 (Table 2). Only two of the formal types present, Mancos Corrugated and Deadmans

Table 2. Ceramic Totals from the 1990 Surface Collections.

Count Percent of Total

Early Ceramics Mesa Verde Tradition Gray Ware

Chapin Gray 30 0.7 Moccasin Gray 51 1.1 Mancos Gray 196 4.4 Unclassified Plain Gray 1378 31.2

Mesa Verde Tradition White Ware Chapin Black-on-white 1 0.0 White Mesa Black-on-white 27 0.6

San Juan Red Ware Abajo Red-on-orange 48 1.1 Bluff Black-on-orange 79 1.8 Unslipped San Juan Red Ware 77 1.7

Subtotal Early Ceramics 1887 42.7

Late Ceramics Mesa Verde Tradition Gray Ware

Dolores Corrugated 29 0.7 Mesa Verde Corrugated 7 0.2 Unclassified Corrugated 1100 24.9

Mesa Verde Tradition White Ware Mancos Black-on-white 205 4.6 McElmo Black-on-white 115 2.6 Mesa Verde Black-on-white 12 0.3 Unclassified Pueblo II white ware 365 8.3 Unclassified Pueblo III white ware 631 14.3

Tusayan White Ware Sosi Black-on-white 0.0 Dogoszhi Black-oh-white 1 0.0

Tsegi Orange Ware Medicine Black-on-red 1 0.0 Tusayan Black-on-red 3 0.1 Polychromes 3 0.1 Unclassified Tsegi Orange Ware 5 0.1

Subtotal Late Ceramics 2478 56.0

Other Ceramics Mesa Verde Tradition Gray Ware

Mancos Corrugated 10 0.2 Mesa Verde Tradition White Ware

Unclassified White Ware 10 0.2 San Juan Red Ware

Deadmans Black-on-red 15 0.3 Slipped San Juan Red Ware 15 0.3

Other or Unknown Unidentified Gray Ware 2 0.0 Unclassified Red Ware 5 0.1 Unidentified 1 0.0

Subtotal Other Ceramics 58 1.3

Total 4423

Percent Dark Paste

40 51 31 50

42

14 29 11

65 77 83 67 78

44

20

70

50

100

19

43

350 James R. Allison

Black-on-red, were common between A.D. 950 and 1050, and both were made and used over a long enough period of time that they possibly could date to either major occupation. About 56 percent of the more than 4,000 potsherds collected from the site can be attributed to the late occupation, whereas about 43 percent are dearly from the early occupation.

The white wares from the later occupation include large numbers of Pueblo II and Pueblo III white ware sherds, many of which cannot be assigned to a specific type. When the Pueblo II white ware can be identified to type, it is almost always Mancos Black-on-white, which dates from about A.D. 1000 to 1150; the classifiable Pueblo III white ware is mostly McElmo Black-on-white, most common in the A.D. 1100s. The combination of Mancos and McElmo, along with the presence ofTsegi Orange Ware and the fact that Dolores Corrugated is the most common formal gray ware type, suggests that the bulk of the late ceramic assemblage at Red Knobs dates between A.D. 1100 and 1180 (Wilson and Blinman 1995, 1999); the late ceramics give a mean ceramic date of A.D. 1148.

Although the later occupation at Red Knobs clearly peaks in the early-middle 1100s, it is more difficult to determine when the occupation began and ended. The complete lack of Cortez Black-on-white, however, which is rare in the western part of the Mesa Verde region but should occur in small quantities on sites from the early eleventh century, suggests that the intensive late occupation probably did not begin much before A.D. 1050. The presence of a dozen Mesa Verde Black-on-white sherds indicates that there was some use of the site after A.D. 1180, but probably not much. In any case, the abundance of Mancos Blackon-white indicates a substantial occupation during the latter part of the Chacoan era, prior to aboutA.D. 1140.

The early occupation appears to date primarily to the late 800s or early 900s. The dearest indication of this is the relative abundance of the two neckbanded gray ware types: Moccasin Gray and Mancos Gray. Wilson and Blinman ( 19 9 9) suggest that Moccasin Gray should be the dominant gray ware type in the A.D. 880-910 (930) period, with Mancos Gray presumably becoming more common during the early part of their A.D. 910 (930) - 980 period before being replaced by corrugated gray wares by the end of that period. The parenthetical (930) in the period endpoints reflects the scarcity of dated ceramic assemblages from the Mesa Verde region that date between the late 800s abandonment of the large villages in southwest Colorado's Dolores River Valley and about A.D. 1000; many details of ceramic change in this period are unknown. The predominance of Mancos Gray over Moccasin Gray at Red Knobs, however, suggests that the bulk of the early occupation postdates the abandonment of the Dolores area villages. The early Red Knobs assemblage yields a mean ceramic date of A.D. 905; the peak of the early occupation may actually have been a decade or so earlier or

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 351

Table 3. Mean Ceramic Dates Calculated for Different Areas of the Site.

Associated Roomblock Early Ceramic Date Late Ceramic Date

Roomblock 1 900 (888-912) 1148 (1138-1158)

Roomblock2 915 (905-925) 1152 (1147-1157)

Eastern Knob 900 (897-904) 1148 (1143-1153)

Roomblock4 912 (900-921) 1149 (1139-1160)

Roomblock5 913 (907-918) 1152 (1139-:1164)

Western Knob 912 (908-916) 1136 (1128-1143)

Roomblocks 7-8 900 (882-917) 1138 (1130-1146)

Roomblock 10 910 (896-925) 1162 (1146-1177)

Note:The ranges in parentheses represent 95-percent confidence intervals derived from a Monte Carlo simulation that estimates the effects of sampling error on the mean ceramic dates2 •

later than that, but the presence of Abajo Red-on-orange suggests at least some use of the site as early as about A.D. 825.

The content of both the early and late ceramic assemblages is relatively consistent across the site, although the relative abundance of early and late ceramics varies somewhat. Table 3 shows mean ceramic dates calculated separately for the early and late types, with the ceramic collection units grouped with the nearest rubble mound. The early dates range from A.D. 900 to 915, while the late dates vary a bit more, from A.D. 1136 for the collection units south of the western knob, to 1162 near the small rubble mound designated as Roomblock 10. Except for the collection units near the two small rubble mounds (Roomblocks 7 and 8) at the west end of the site, however, all the other areas yielded dates between AD. 1148 and 1152. This could mean that the building on the western knob, along with the two small mounds to the west, were the first structures built when the site was reoccupied, while the small kiva-less Roomblock 10 was built late in the occupation. In any case, the ceramic surface collections indicate that the site was intensively occupied during the latter part of the Chacoan era, in the early-mid 1100s. It may have continued to be occupied until about A.D. 1200, or the small amount of Mesa Verde Black-on-white may be from a later small-scale reoccupation of the site.

The Dispersed Community

Great house sites are almost always surrounded by smaller, contemporaneous unit pueblo habitations, and Red Knobs is no exception. No systematic survey has been conducted around Red Knobs, but a brief reconnaissance in 1990

352 James R. Allison

~.

\ .. \ \ \

\ \~ ·. ~

\ 9> \~

. 0 -·· \ °" ---~-----·· -··-··-·· ·., L.. .,,_... .... ,,,,..,. """'·· ....... .-.-~ ... ~ '··~ \

\

t ~ - - -O meters 250

Contour interval 25 m

\ \ \ \ \ \ \

\

Figure 8. Map of the area around Red Knobs showing the locations of sites found during the reconnaissance that are contemporary with the AD. 11 OOs village.

recorded six sites that appear to have late Pueblo II/early Pueblo III occupations contemporaneous with the later village at Red Knobs (Figure 8). These sites all have small rubble mounds; Site 2 has two small mounds with two kivas each, two other sites lack kiva depressions, the others each have one or two kivas.

Local and Nonlocal Influences at Red Knobs

There is little at Red Knobs to suggest direct Chacoan influence, at least in the surface archaeology. The great kiva, road, and possible great house could be taken as indicators of Chacoan influence, but whether they are interpreted that

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 353

way is largely a matter of definition, as roads, great kivas and great houses are found throughout much of the Anasazi world.

The only non local ceramics identified in the surface collections were a few sherds of Tusayan White Ware and Tsegi Orange Ware, indicating trade to the southwest rather than the southeast. The ceramics were sorted using macroscopic traits; microscopic examination of inclusions is more reliable for distinguishing Chacoan ceramics from similar Mesa Verde types, and it is likely that Cibola Gray Ware (or Tusayan Gray Ware for that matter) was not recognized if it was present. Cibola White Ware could also have been missed, although white wares are more easily distinguished macroscopically. If much Cibola White Ware was present, it is likely that at least some would have been recognized. The only indication of ceramic trade with areas to the southeast is one sherd of Wingate Polychrome found near the western knob when the site was revisited in 2001.

In contrast to the near lack of obvious non local pottery, a large proportion of the potsherds are distinctly local. About 56 percent of the late sherds, and 73 percent of the white wares from the late occupation, are dark-paste varieties of traditional Mesa Verde types (Table 2). Dark-paste sherds are common on sites in the western Mesa Verde region (Allison 1991; Severance 2003), and are probably made with high-iron, Chinle formation days that are exposed in the Monument Upwarp west of Cottonwood Wash (Allison 1991). Red Knobs is neartheedge of the Monument Upwarp, and potters living there probably had access to the darkpaste days as well as lighter-firing days. The dark-paste ceramics at Red Knobs could represent on-site production, trade with people living a short distance to the west, or both.

One other aspect of the later village at Red Knobs that seems distinctly local is its location on the earlier village. In the western Mesa Verde region, late Pueblo II and Pueblo III sites seem often to have been systematically placed on the ruins oflarge, late Pueblo I sites. This pattern has sometimes been interpreted as evidence that these locations were particularly favorable for some environmental reason. That may be true in some cases, but in others there is no particular advantage to locating on top of an earlier site, and doing so would usually be inconvenient because of the debris that would be underfoot. The superposing of sites may often have been a deliberate, symbolic act. In most cases, as at Red Knobs, these late Pueblo I villages were large. The ruins of the earlier villages may have evoked a period of past glory, or served as symbols of land ownership (Varien 1999:210-211; Varien et al. 1996:103), and control over the former village locations may have strengthened claims over the land surrounding it.

The late Pueblo I occupation at Red Knobs is largely obscured by the later village, but there is a large arc of low rubble near the eastern end of the site that appears to be the remains of an earthen building. Other slab-lined architectural features are apparent south of the eastern knob, and the distribution of early

354

D Rubble Mound

/ Steep Drop-Off

c::, Probable Rubble

'-' Wall Alignment

James R. Allison

Density of Early Sherds o 0-21 m2

e 2-8 / m2

• >8 / m2

o Cera:ic :011::ion Unit ~I O meters 50

Great Kiva -~o Figure 9. Map of Red Knobs showing the locations of the ceramic collection units, and the density of early ceramics within them.

ceramics (Figure 9) suggests that there were probably early structures against the south sides of both knobs. The large early roomblock north and east of the eastern knob, which is not covered by later material, is difficult to interpret in places, but it includes at least 100 linear meters of rubble, and probably more like 200 linear meters. Using the formula proposed by Wilshusen and Blinman (1992:257), that amount of rubble would suggest 14 to 27 households-about 75 to 150 people-for the most visible early structure, and it was dearly not the only early structure on the site.

The early coffi'munity also apparently included more than just the site now defined as Red Knobs. One of the late Pueblo II/early Pueblo III unit pueblos found during the reconnaissance is on top of a large late Pueblo I site that appears to be contemporary with the early occupation at Red Knobs (Site 4 on Figure 8). That site is about 200 m north of Red Knobs, and includes what appears to be a 75 m long retaining wall, more than 100 linear meters of rubble (though some of it belongs to the small, late reoccupation), and a rectangular feature, about 10 x 18 m, that was outlined by a low stone wall. This feature appears to be some kind of public architecture; it is about 75 m west of the rest of the site with no associated surface artifacts, so it is not dear whether it is contemporary with the main part of the site.

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 355

When the later village was established at Red Knobs, the ruins of the earlier occupations at Red Knobs and Site 4 would have been the most prominent features of the cultural landscape. By the late eleventh or early twelfth century; the earlier community had been abandoned for a century or more, and there is no indication of sites in the immediate vicinity that date to the period between the two main Red Knobs occupations. The reoccupation of Red Knobs apparently coincided with the reoccupation of a larger area around it, and under these circumstances it may have been important to strengthen claims to the land through symbolic links to the most prominent of its former inhabitants.

In the case of Red Knobs, the choice to locate on top of the earlier ruins may have been influenced by the location near Cottonwood Wash and by the presence of a small seep in the drainage between Red Knobs and Site 4; the location probably really is the best spot in the immediate vicinity to put a village. There are other cases of superimposed occupations, however, where the location seems to offer no particular advantage. For example, early Pueblo III sites on Little Baullie Mesa, about 10 km southwest of Red Knobs, seem to have been systematically located on the most substantial late Pueblo I sites whenever possible, despite a mesa-top setting that provided abundant alternative locations that were at least as advantageous as the locations that were chosen3 •

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Red Knobs was quite a large site for southeastern Utah. The later occupation probably included about 150 rooms, 15 of which were small kivas; a great kiva and a road were also present. Ceramics indicate substantial occupation in the early 1100s, toward the end of the Chacoan era and somewhat earlier than previously thought. By many definitions Red Knobs easily qualifies as a great house site; for instance, when viewed in light of Lekson's (1991) big bump/small bump dichotomy, Red Knobs is a very big bump surrounded by much smaller bumps. By other definitions, (e.g., Kincaid et al. 1983:9.17) its status as a great house site is more equivocal and cannot be definitively determined from surface evidence.

One problem with defining Red Knobs as a great house site, however, is that no single roomblock can be definitively identified from surface evidence as the great house. Roomblock 1 is probably the best candidate, but there may be more than one building with great house characteristics at the site. If in fact there are multiple small great houses, it might suggest that the Red Knobs community was less integrated than other neighboring communities, and there may have been an unusual degree of competition among lineages or individuals for preeminence. The possible great house structures may also have been occupied sequentially, although the surface ceramics provide little evidence for sequential occupation.

356 James R. Allison

Even if Red Knobs is a great house site, it is not clear that it is Chacoan in any meaningful way. The great kiva and road, and the possible great houses, may be a form of symbolic entrainment evoking connections to the distant center at Chaco Canyon, but there is little evidence for direct links with Chaco. Several aspects of the site are distinctly non-Chacoan, including the small size of the possible great houses. Furthermore, the Chacoesque elements of the site are balanced by what appears to be deliberate superposing on the earlier village, indicating a strong concern to make and express connections with the distinctly local past.

Red Knobs is on the very edge of the distribution of great houses in the northern Southwest, and it is far (about 230 km) from the much more elaborate great houses at Chaco Canyon. It was not isolated, however. At least eight other great houses are found in the part of southeastern Utah north of the San Juan River and west of Blanding, along with several isolated great kivas and a series of roads that appear to have linked many of these "Chacoan" features (Hurst and Till 2002; Till 2001; Till and Hurst 2002). Published descriptions are available for only three of these great houses (Hurst 2000; Jalbert and Cameron 2000; Mahoney 2000), and only the Bluff great house has seen the sustained, detailed research needed to really understand it. A few things are clear about this cluster of great houses, however. Despite the evidence that they were integrated by a road system, they are highly variable in size, layout, and the degree to which they exhibit obvious "Chacoan" characteristics. Hurst and Till (2002:7) suggest that "individuality [among the southeastern Utah great houses] is so evident that it appears to have been consciously strived for." In any case, the observed variability implies that this great house cluster more likely comprised a network ofloosely linked community centers than a tightly linked, hierarchical system, although the pronounced differences in size may indicate that some community centers were more central than others.

Of the southeast Utah great houses, Cottonwood Falls is by far the largest, while Bluff appears_ to have the most (or just the best documented?) "Chacoan" architectural characteristics, including core-and-veneer walls in the great house, and berms surrounding it. The much smaller great house at Edge of the Cedars also has core-and-veneer masonry, and one of the blocked-in kivas has Chacostyle floor features. None of the southeast Utah great houses evinces strong economic ties to the San Juan Basin, however; ceramics, for example, always appear to be primarily local with most of the obvious non local pottery originating in the Kayenta region. Still, copper bells found at Edge of the Cedars suggest that at least some of the inhabitants of these great houses participated in elite trading networks stretching as far as northern Mexico, which likely passed through Chaco Canyon.

Despite much variability in the characteristics of the southeast Utah great

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 357

houses, Red Knobs, Arch Canyon, Bluff, Cottonwood Falls, and Edge of the Cedars (at least) all appear to have been located atop substantial late Pueblo I sites. As argued above, the late Pueblo I villages were the largest sites in the region prior to the establishment of the great houses themselves. The ruins of these early villages would have been the most visible aspects of the cultural landscape at the time the great houses were established, and the most obvious links to the past inhabitants of the area. Thus, regardless of the extent of their actual ties to Chaco or to the prior inhabitants of the southeastern Utah, Red Knobs and other nearby great houses can be understood, in part, as symbolic expressions of two ideas. Connections to the large, distant great houses in the San Juan Basin would have been evoked by aspects of architecture and site layout that mimic (however imperfectly) Chacoan traits. At the same time, locating the great houses on the earlier ruins asserted ties (whether real or imagined) to the prior inhabitants of the local area.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article benefitted from the advice and efforts of numerous people. The bulk of the field work at Red Knobs was completed in 1990 and 1991 as part of a volunteer program sponsored by the Sierra Club's Native American Sites Committee, under the direction of Harvard Ayers of Appalachian State University. The program was a cooperative effort among the Sierra Club, the Manti-La Sal National Forest, and the Bureau of Land Management to better document sites in southeastern Utah that were impacted or threatened by looting. Dale Davidson provided oversight and support for the BLM portion of this effort, which included the mapping of Red Knobs and the reconnaissance survey around it. Numerous Sierra Club volunteers participated in this effort; it is not possible to name them all, but the project could not have been completed without them. Edge of the Cedars State Park in Blanding, Utah, provided space for the ceramic analysis in the summer of 1990, and Winston Hurst, who was then curator at Edge of the Cedars, provided invaluable advice as the analysis proceeded. Ten years later, Winston's inquiries about the location of the original site map prompted me to unearth it from my basement so it could be properly curated, and got me thinking about the site again. Winston also accompanied me and my son Christopher on a one-day site revisit in 2001 during which much was accomplished. The original version of this paper was presented at the 2002 SAA meetings in a symposium organized by Mark Varien. This final version benefitted from written comments on earlier drafts from Andrew Duff, Catherine Cameron, Winston Hurst, Owen Severance, and Ronald Towner, although I retain responsibility for any errors or omissions. John Baxter and Meradeth Snow translated the abstract into Spanish.

358 James R. Allison

NOTES

1. Most of the Red Knobs data was collected in the early 1990s under an agreement between the BLM and the Sierra Club's Native American Sites Committee. In 1990 a team of Sierr~ c;;~ub volunteers l_ed by Harvard Ayers of Appalachian State University. produced an m1ual map of the site and made ceramic surface collections from 4 7 collection units scattered across the midden areas of the site. I classified the collected ceramics in 1990 and returned to the site in 1991 with another group of Sierra Club volunteers to refine the map. This early-1990s information was supplemented in the summer of 2001 when Winston Hurst and I visited the site and did additional documentation.

2. Mean ceramic dates for the late occupation were calculated using five formal types. The types used and the mean dates associated with them are: Dolores Corrugated, A.D. 1175; Mesa Verde Corrugated, A.D. 1200; Mancos Black-on-white, A.D. 1090; McElmo Black-on-white, A.D. 1188; and Mesa Verde Black-on-white, A.D. 1240. In ~ddition, Pu~blo II an? Pueblo III white ware that could not be classified to a speciflC type was mcluded m the calculations, assuming a mean date of A.D. 1090 for Pueblo II white ware and A.D. 1188 for Pueblo III white ware.

Fo_r the earl~ occupation, mean ceramic dates were calculated using five types: Moccasm Gray, with a mean date of A.D. 863; Mancos Gray, with a mean.date of A.D. 925; Bluff Black-on-red, with a mean date of A.D. 890; Piedra Black-on-white, with a mean date of A.D. 888; and White Mesa Black-on-white, also with a mean date of A.D. 888.

A simple Monte Carlo simulation was used to estimate the potential error in the calculated mea? ceramic dates that would be expected due to sampling error. The 95 % confidence mtervals suggested by the simulation are included in Table 3. These ranges are generally quite short, suggesting that the observed mean ceramic dates are not strongly affected by sampling error. Other factors can affect the accuracy of the dates, however, notably decisions about which types to include in the calculations and what date to assign to each of the types.

3. The Little Baullie Mesa Survey was completed in 1998 by Baseline Data, Inc., under my supeivision. It was funded by the Bureau of Land Management in association with efforts to reduce the fire danger and improve elk habitat on the mesa. More than 100 sites were recorded, five of which are late Pueblo I hamlets or small villages with ceramic assemblages very similar to the early assemblage from Red Knobs. After the late Pueblo I sites were abandoned, the mesa was only lightly occupied until late Pueblo II ~mes. One of the large Pueblo I sites was reoccupied in the late 1000s, when a senes of small structural sites, probably field houses, was built on the mesa. Thirteen relatively more substantial unit pueblos appear to date to the early-mid 1100s, with ceramic assemblages much like the late assemblage from Red Knobs. Four of these are on top of the large Pueblo I sites that had not been reoccupied earlier. F~rthermor~, only five of the thirteen sites recorded from the early to mid-llOOs have kiva depress10ns, three of which are on the reoccupied sites. A chi-square test suggests that the greater proportion of sites with kivas on the reoccupied sites is unlikely to be due to sampling error alone ( chi2 = 4.26, p = .039). Thus, not only was each of the large Pueblo I sites reoccupied in the late eleventh or early twelfth century, the most substantial late sites (those with kivas) seem to have been preferentially located on the large earlier sites, which would have been the most noticeable features of the cultural landscape in the 1100s.

Surface Archaeology of the Red Knobs Site 359

REFERENCES CITED

Allison, James R. 1991 Dark Firing Ceramics from Southern Utah. Unpublished manuscript in possession of

author. Breternitz, David A., Arthur H. Rohn, Jr., and Elizabeth A. Morris

1974 Prehistoric Ceramics of the Mesa Verde Region. Museum of Northern Arizona Ceramic Series No. 5. Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, Flagstaff.

Hurst, Winston B. 1992 Previous Archaeological Research and Regional Prehistory. In Cultural Resource Inven

tory and Evaluative Testing along SR-262, Utah-Colorado State Line w Montezuma Creek, Navajo Nation Lands, San Juan County, Utah, by Mark C. Bond, William E. Davis, Winston B. Hurst, and Deborah A. Westfall, pp. 11-75. Abaja Archaeology, Bluff, Utah.

2000 Chaco Outlier or Backwoods Pretender? A Provincial Great House at Edge of the Cedars Ruin, Utah. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pp. 63-78.Anthropological Papers No. 64. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Hurst, Winston B., and Jonathan D. Till 2002 Some Observations Regarding the "Chaco Phenomenon" in the Northwestern San

Juan Provinces. Paper presented at the 67"' Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Denver, Colorado.

Jalbert, Joseph Peter, and Catherine Cameron 2000 Chacoan and Local Influences in Three Great House Communities in the Northern

San Juan Region. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pp. 79-90. Anthropological Papers No. 64. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Kincaid, Chris, John R. Stein, and Daisy F. Levine 1983 Road Verification Summary. In Chaco Roads Project, Phase I: A Reappraisal of Prehistoric

Roads in the San Juan Basin, edited by Chris Kincaid, pp. 9.1-9.78. USDI Bureau of Land Management, New Mexico State Office, Albuquerque.

Lekson, Stephen H. 1991 Settlement Pattern and the Chaco Region. In Chaco and Hohokam, edited by Patricia L.

Crown and W. James Judge, pp. 31-55. School of American Research, Santa Fe. Mahoney, Nancy M.

2000 Redefining the Scale of Chacoan Communities. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pp. 19-27. Anthropological Papers No. 64. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Severance, Owen 1999 Prehistoric Roads in Southeastern Utah. In La Frontera: Papers in Honor of Patrick H.

Beckett, edited by Meliha S. Duran and David T. Kirkpatrick, pp. 185-195. Archaeological Society of New Mexico Papers No. 25. Albuquerque.

2003 Cultural Dynamics in Southeastern Utah: Basketmaker III through Pueblo I. In Climbing the Rocks: Papers in Honor of Helen and Jay Crotty, edited by Regge N. Wiseman, pp. 189-203. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico No. 29. Albuquerque.

Till, Jonathan D. 2001 Chacoan Roads and Road-Associated Sites in the Lower San Juan Region: Assessing

the Role of Chacoan Influences in the Northwestern Periphery. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, University of Colorado, Boulder.

Till, Jonathan D., and Winston B. Hurst 2002 Trail of the Ancients: A Network of Ancient Roads and Great Houses in Southeastern

Utah. Paper presented at the 67m Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Denver, Colorado.

Varien, Mark D. 1999 Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. The University of

Arizona Press, Tucson.