Sunshine on Leith case study

Transcript of Sunshine on Leith case study

Sunshine on Leith case study

When Sunshine on Leith starts, after the production company logos have faded away, we are presented with a long shot of trucks driving down a dirt track road. The sun is setting and a helicopter flies overhead. Tense music plays and the camera cuts to show us the interior of one of the trucks. Soldiers are sat on benches facing each other, they are kitted out in full gear. As we absorb the scene one of the soldiers starts to sing: ‘It could be tomorrow or it could be today / When thesky takes the soul / The earth takes the clay / It could be tomorrow or it could be today / When the sky takes the soul / The earth takes the clay’ (Charlie Reid and Craig Reid, 1990).The insistence in the singer’s voice and the emphatic way he stares at his fellow soldiers makes us aware of the urgency ofthe situation that they are in. This is highlighted when the other soldiers join in and the cinema for a moment is filled with the persistent voices of the men before us. The soldier who began the singing carries on as the others bring their parts to an end: ‘I sometimes wonder, why I pray / When my spirit just drives away / With a faith and a bit of luck / Anda half tonne bomb in the back of the truck’ (Charlie Reid and Craig Reid, 1990). The camera cuts back to the long shot of the convoy as the trucks come to a halt, it becomes clear thatthere is a problem with the lead truck and as the situation isbeing resolved the camera cuts back to the inside of the truckas another soldier starts to sing: ‘If it’s tomorrow or if it’s today / I don’t say it will be, I just say it may / When I’m on my knees to the gates I’ll stumble / And plead my case in a style that’s humble’ (Charlie Reid and Craig Reid, 1990).The trucks start to move and all the soldiers smile with relief and start to sing the chorus again: ‘It could be tomorrow, it could be today / When the sky takes the soul / The earth takes the clay’ (Charlie Reid and Craig Reid, 1990).The second time they begin to sing the chorus they do not makeit to the second line, on the word ‘today’ there is a bang andthe screen goes white. As we watch we are aware we are watching soldiers who are in a war zone, otherwise they would not be so well kitted out, when the lead truck stops the worried looks on the soldiers faces builds the tension further. As an outside spectator I was also aware that something was going to happen as the film is called Sunshine on

Leith and the opening scene clearly is not taking place in the Scottish capital Edinburgh. Something, therefore, has to happen to move the action from, what I assumed to be Afghanistan, to Scotland. When the bomb explodes and the screen goes white the next thing we see is a long shot of Edinburgh and the lettering on the screen informs us that thisis ‘6 months later’ (Dexter Fletcher, Sunshine on Leith, 2013). After the opening which draws us in with its ambiguous settingand serious subject matter we are where we were informed we would be when we bought the cinema ticket, Leith, and the filmcan continue having grabbed our attention with its opening scene.

However, I am getting ahead of myself. The experience of cinema does not begin as the production companies logos fade away so where exactly does the experience of cinema begin? In the foyer as we purchase our tickets? As the lights dim and the adverts and trailers start? As soon as we sit in our seats? To speak about the experience of cinema it is necessaryto define what exactly goes into this experience. During this case study I will be speaking of myself as the spectator as I cannot assume what other members of the audience felt or experienced when they watched Sunshine on Leith. For me the cinematic experience has different starting points, the first begins as soon as you take your seat. Going to the cinema is about participating in a visual medium and the way the seats are laid out encourages this whether there is anything playingon the screen at the front or not. I always buy seats in the back row as they give me more leg room but they also allow me to watch the other members of the audience and to eavesdrop oninteresting sounding conversations. How much I do this became apparent before Sunshine on Leith started because I was sat at theback on my own. That was the first thing I notice, just how odd a feeling it is to be sat in a cinema on your own. I do not mean with no one else in the room but with no one else having gone to see the film with you. For me cinema is a social experience, you talk to the people you are with before the film starts, you discuss it as you leave and you try and remember what trailers were played before the film in case anywere films you might want to go and see together at another time. If being sat on my own felt odd then being sat with a pen and a pad of paper felt wrong. I go to the cinema to watchfilms, I move as little as possible so as to not distract

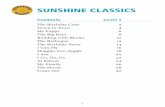

others, I would rather not eat during the showing due to the rustling the bags of sweets make and I definitely do not talk during the film (see Wittertainment’s Code of Conduct, image A). According to Judith Mayne spectatorship ‘involves the actsof looking and hearing inasmuch as the patterns of everyday life are dramatized, foregrounded, displaced, or otherwise inflected by the cinema’ (1993: 31). However, what she does not address is how we are not just looking and hearing the film being played before us, there are other audience members who distract us from the action on the screen and we can hear and see them equally. Mayne goes on to state that experiencingfilms in the cinema involves a ‘unique and specific combination of individual fantasy and social ritual’ (1993: 66). The individual enters the cinema space to be immersed into the film they are watching whilst at the same time conforming to the ritual of going to the cinema: queuing for tickets, buying tickets, getting the tickets torn by an usher,finding their seats, turning mobile phones off, not speaking until the end of the film etc. Being sat on my own in the cinema was not part of my cinema going ritual and it was not an experience I was relishing; then I heard a woman say to herdaughter ‘I wish they would play some music’, until she said that I had not noticed that the CD that usually played roughlyten minutes before a film starts at the Vue in Lancaster had not been switched on. The comment was quite funny as we were all here to see Sunshine on Leith which has been jokingly dubbed ‘The Proclaimers Musical’ by Mark Kermode and Simon Mayo on their Friday film review show. We were about to watch and listen to over an hour and a half of a musical set to songs byThe Proclaimers and here was a member of the audience bemoaning the fact that the cinema was silent before anything had even begun. I understand why she said it though, a film according to Sobchack ‘makes itself sensuously and sensibly manifest as the expression of experience by experience. A filmis an act of seeing that makes itself seen, an act of hearing that makes itself heard, an act of physical and reflective movement that makes itself reflexively felt and understood’ (1995: 37). When we enter a cinema knowing that all of these experiences are waiting for us if there is silence it is a surprise as we know that there is supposed to be both sound and image, if there is nothing to see or hear it is worth commenting on.

The second stage of cinema experience begins for me when the lights dim and adverts and trailers are played before the feature film. Watching the trailers of upcoming films is part of the experience as I look forward to seeing what will be released in cinemas at a later date. They tie in to the viewing experience for me as spectatorship is not solely aboutwatching the film you go to the cinema to see it is ‘also the ways one takes pleasure in the experience, or not; the means by which watching movies becomes a passion, or a leisure-time activity like any other’ (Mayne, 1993: 1). As I mentioned before the cinematic experience has certain rituals and sitting through adverts and trailers is one of them. Before Sunshine on Leith the adverts consisted of ones that I had alreadyseen on television, they were for products like mouthwash, WiFi, frozen food and ITV. Having seen all these adverts before and the fact that they run for about ten minutes beforethe trailers start had the result that I eventually switched off and stopped paying attention to what was on the screen. When the trailers eventually started I was grateful that the monotony of the adverts had ended and I paid closer attention to the trailers. As cinemas cannot show trailers of a different rating to the film that will eventually be shown allthe trailers had a PG rating and were for predominantly happy and uplifting looking films. They also seemed to centre round music in some way or other; Saving Mr Banks is based on Walt Disney trying to get the rights for the Mary Poppins books and One Chance is a film based on the life of Britain’s Got Talent winner Paul Potts. The cinema, as a business, knew that the audience had come to see Sunshine on Leith and so they were targeting us with films that were a similar genre to the one that we were going to be watching to encourage us to come and see these films in the future.

Jumping ahead to what I think of as the fourth stage of cinema experience and spectatorship which can be defined as ‘not just the relationship that occurs between the viewer and the screen, but also and especially how that relationship lives on once the spectator leaves the theatre’ (Mayne, 1993: 2-3). When the film had ended and I got up to leave I could not move out of the aisle because a woman was stood at the endwith her eyes fixated on the screen and was singing along to the song that was playing over the closing credits. I felt like I could not interrupt her and so just waited until

eventually her daughter got bored and asked if they could leave. I have never sung along to a musical whilst at the cinema but what I always do is head back home, turn on my computer, open iTunes and download my favourite songs from thesoundtrack so that the experience of watching the film and enjoying the music can carry on even when I am no longer in the cinema. I do this especially with musicals, though occasionally with film soundtracks, as at the end of a musical‘only entertainment remains, reality having been obliterated by the force of the film itself’ (Feuer, 1993: 71). I agree with the review in Empire Magazine, written by Ian Freer, who stated that when Sunshine on Leith ‘moves away from its musical numbers, the film feels less certain, falling into soap-opera shenanigans around rejected marriage proposals, long-lost daughters and plot-changing heart attacks’ (www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?FID=138317). Yet, even though the story was not of the highest standard themusic had an energy that made the overall film more affecting than if there had been no music at all. I have mentioned affect before and I will outline what I mean by that term now.Wissinger states that affect ‘precedes emotions; affect is notconscious, but it has a dynamism, a sociality or social productivity’ (2007: 232). When I speak of affect I am talkingof an emotional response that hits us whilst we are watching the film, it is immediate and insistent in the way that it connects us to the film we are viewing. It can also be seen asa social experience as it ‘constitutes a contagious energy, anenergy that can be whipped up or dampened in the course of interaction’ (Wissinger, 2007: 232). This is why musicals are so appropriate to analyse as they are created to deliberately stir up emotions in the audience, if you leave the cinema after viewing a musical feeling nothing at all the film has not done its job. A question remains with regards to affect, can it be analysed after the event has taken place? Can we write about it in hindsight or is it a fundamentally singular occurrence? Is this why I buy the songs after seeing the film,to try to recreate an experience that cannot be recaptured? According to Borch-Jacobsen affect eludes recollection as it is ‘always perceived in the present’ (1993: 58). When it comesto analysing musicals why look at affect at all if it is so intangible?

The reason to focus on the affective importance of films when they are viewed in a cinema is because traditional textual analysis that focuses on the formal and technical aspects gives priority to the film that is being analysed and ignores the complexity of the cinematic institution. Accordingto Annette Kuhn when exploring the cinema-consumer relationship film studies concerns itself with a ‘spectator addressed or constructed by the film text – the “spectator-in-the-text”. The film text remains central, then, and the question at issue is how a film “speaks to” its spectators, how the meanings implicit in its textual operations may be brought to light’ (2002: 4). However, this has nothing to do with how a person watching a film in a cinematic environment might respond to both their surroundings as well as the film itself. Going back to the third stage of cinema experience now, for me it lies in watching the film and understanding howI use my cultural knowledge to decode the film and to get moreenjoyment from it. This can be done by looking at the signs within the film and how we gain meaning from them which creates an affective response within us. Mulvey outlines how the audience reacts when they have decoded something that is on the screen: ‘This reaction marks the gap between the unselfconscious “I see” and the self-consciousness of “I see!” The audience reacts as it might to gags or jokes, for which decoding is not only essential to the very process of understanding but also involves a similar moment of detachment, a moment, that is, of self-conscious deciphering’ (2005: 149). It is during this moment of deciphering that I find the most affective during the cinematic experience as it makes me aware of what I am watching rather than letting the multitude of signs wash over me. Usually when signs are spokenof in relation to films it is the technical aspects that are being spoken of, the ‘basic figures of the semiotics of the cinema [are the] – montage, camera movements, scale of the shots, relationship between image and speech, sequences, and other large syntagmatic units’ (Metz, 1974: 94). This form of analysis breaks the film up into a set of components that can be analysed individually. Bignell extends this semiotic analysis of the cinema to include the experience of cinema-going itself. He states that the ‘whole experience is designedto feel secure, ordered, safe and comfortable, an evening out of which the film is a major but by no means the only part’

(1997: 179). How I will be analysing the signs in Sunshine on Leith is by understanding that:

Any film sequence can be analysed to discover the relationship between signs in the sequence, and the way that the signs from different signifying systems (image, sound) are combined together by means of codesto generate meanings. The meanings of films are generated as much by the connotations constructed by the use of cinematic codes as by the cultural meaningsof what the camera sees. Cinema uses codes and conventions of representation which are shared by bothfilm-makers and audiences, so that the audience actively constructs meaning by reference to codes (Bignell, 1997: 187)

Throughout Sunshine on Leith there are examples of signs that can be read using these codes and in particular I will focus on viewing them through the academic lens of Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce. Saussure developed a formof semiotics that ‘defined the linguistic sign as a two-sided entity, a dyad’ (Cobley and Jansz, 2004: 10) where one side consisted of the signifier which was the material aspect of a sign and the other side was the signified which is the mental concept that is produced by the signifier (Cobley and Jansz, 2004: 10). After the very beginning of Sunshine on Leith, just after the bomb has exploded and the screen has faded to white,we are shown a long shot of the city of Edinburgh, two soldiers are walking down a road talking to each other and thecaption over the screen reads ‘six months later’ (Sunshine on Leith, 2013). As we watch the two soldiers break into the song ‘On My Way’, the lyrics include the lines ‘I am on my way frommisery to happiness today’. This is an example of the dyadic sign as it is a very literal form of sign. We have seen the two soldiers at war, we have seen the bomb go off and now we can see that they are in a sunny city with smiles on their faces. They are literally on their way from misery to happiness, this is emphasised by the fact that the section at the start inside the army trucks was dimly lit whereas in contrast the scenes in Edinburgh are full of light as they dance down the street. According to Daniel Chandler semiotics involves not just the study of everyday speech but of

‘anything which “stands for” something else’, signs can take the form of ‘words, images, sounds, gestures and objects’ (2002: 2). So when we see Davy (George MacKay) putting a napkin on his head during the song ‘Let’s Get Married’ and walking down an aisle of people with Ally (Kevin Guthrie) we can deduce that he is playing the role of the woman (see imageB). We know that traditionally women wear veils when getting married and the way he has tied the napkin around his head is also reminiscent of an old fashioned bonnet that women used towear. This is part of Saussure’s dyadic theory as we see the napkin and it brings to mind the notion of a woman walking down the aisle at a wedding. This is because one half of the sign is ‘not a material sound, a purely physical thing, but the psychological imprint of the sound, the impression that itmakes on our senses’ (de Saussure, 1966: 66). In this example hearing a sound sound is replaced by looking at the physical object, the napkin on Davy’s head.

Another way of looking at signs in relation to films is through the theory of Peirce who went one stage further than Saussure and developed a triadic form of semiotics, there is the ‘sign, thing signified, [and the] cognition produced in the mind’ (Peirce, 1991: 183). The sign is also called the representamen, the thing signified is the object and the cognition produced in the mind is the interpretant (Peirce, 1940: 99-100). So when we see Rab (Peter Mullan) frowning over a letter and a photo thathe has received along with an invitation to a funeral we understand that the representamen is his physically frowning face, the object is the letter that is causing him to frown and the interpretant is us deducing that the contents of the letter are distressing and upsetting enough to cause him to frown and look sad. Our guess is confirmed later on when we find out that the woman whose funeral it was had had an affairwith Rab just after he married Jean (Jane Horrocks) which resulted in a daughter that he never knew about. This is one of the main storylines in the film and the one which causes the most tension and angst with the characters, eventually resulting in Rab having a heart attack. Another example of this kind of sign is when Davy and Ally are talking to each other about going out to the pub that night, Ally teases Davy by saying that Davy’s sister wants him to meet a friend of hers to see if they hit it off and can end up going out together. Davy asks Ally what is wrong with her, Ally states

‘She’s English’, a look of incredulity and disgust goes over Davy’s face before he exclaims ‘English?!’. We see his face, we hear what he says but it takes the third level of the sign for us to comprehend the Scottish dislike for the English, this reading relies on our cultural knowledge. In an interviewwith Joyce Savage she states:

‘It’s definitely a one way thing the Scottish hating the English ‘coz the English couldn’t really give two hoots about the Scottish. You know they don’t like them or hate them or worry about them at all. They’re just other people. In Scotland it’s quite inbred that you don’t like the English. You’re sort of brought up not through anything anyone says but that’s just part of the whole culture (McCarthy, 2005: 177)

Watching this scene from Sunshine on Leith I was aware of the Scottish “hatred” of the English without being to state why I knew of it. The knowledge of it has been something that I havegrown up with and been made aware of from throw away comments by family and friends. It is a taken for granted aspect of therelationship between the English and the Scots and is brought more to the fore this year with the Scottish referendum comingup in 2014 where Scotland will vote either yes or no to becomeand independent country (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-21828424). A serious topic is covered in Sunshine on Leith in one humorous line, yet it is stillcovered. Dexter Fletcher could have chosen to ignore the topiccompletely and because the line is delivered with humour as a member of the audience I laughed and thought nothing of it which reflects just how musicals place ‘shimmering glass doors[...] between themselves and any form of intellectual inquiry’(Feuer, 1993: ix). In order to discuss musicals we need to seethrough the glass doors and, in the case of this thesis, use them to discuss whether or not affect can be seen to work outside the world of the cinema or if it is confined to a single specific environment (change last sentence).

Image A, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00lvdrjImage B, Still taken from Sunshine on Leith (2013)

Dexter Fletcher

Word Count: 3,924

Bibliography:

Bignell, Jonathan (1997) Media Semiotics: An Introduction, Manchester:Manchester University Press

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel (1993) The emotional tie: psychoanalysis, mimesis and affect, Stanford: Stanford University Press

Chandler, Daniel (2002) The Basics: Semiotics, New York: Routledge

Cobley, Paul and Jansz, Litza (2004) Introducing Semiotics, Cambridge: Icon Books Ltd

de Saussure, Ferdinand (1966) Course in General Linguistics, translated by Wade Baskin, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company

Dyer, Richard (1981) ‘Entertainment and Utopia’ in Rick Altman(ed.) Genre: The Musical: A Reader (pp. 175-188) London: Routledge &Kegan Paul

Feuer, Jane (1993) The Hollywood Musical, London: The MacMillan Press LTD

Kuhn, Annette (2002) An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory, London: I.B. Tauris Publishers

Mayne, Judith (1993) Cinema and spectatorship, London: Routledge

McCarthy, Angela (2005) ‘National Identities and Twentieth-Century Scottish Migrants in England’ in William L. Miller (ed) Anglo-Scottish Relations: from 1900 to Devlolution and beyond (pp. 171-183) Oxford: Oxford University Press

Metz, Christian (1974) Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema, translated by Michael Taylor, New York: Oxford University Press

Mulvey, Laura (2005) Death 24 x a second: stillness and the moving image, London: Reaktion

Peirce, Charles Sanders (1991) Peirce on Signs, edited by James Hoopes, London: University of North Carolina Press

Peirce, Charles Sanders (1940) The Philosophy of Peirce: Selected Writings, edited by Justus Buchler, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Reid, Charlie and Reid, Craig (1990) ‘Sky Takes the Soul’ fromthe album This is the Story

Sobchack, Vivian (1995) ‘Phenomenology and the film experience’ in Linda Williams (ed) Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, p. 36-59

Sunshine on Leith (2013) Dexter Fletcher, UK

Wissinger, Elizabeth (2007) ‘Always on display: affective production in the modelling industry’ in Patricia Ticineto Clough with Jean Halley (eds) The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social (pp. 231-261) Durham: Duke University Press