Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijgo

AVERTING MATERNAL DEATH AND DISABILITY

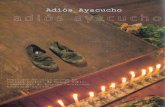

Strengthening emergency obstetric carein Ayacucho, Peru

M. Kayongo a,*, E. Esquiche b, M.R. Luna b, G. Frias b,L. Vega-Centeno b, P. Bailey c

a CARE, Atlanta, GA, USAb CARE, Ayacucho, Peruc Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

Received 9 May 2005; accepted 2 December 2005

0020-7292/$ - see front matter D 200All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.12.005

Abbreviations: DIRESA, Direccion RMaternal Emergencies; GoP, GovernmeAyacucho.4 Corresponding author. Fax: +1 404

E-mail address: [email protected]

KEYWORDSMaternal mortality;Emergency obstetriccare;Facility interventions;Latin America;CARE

Abstract

Objective: With support from the Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AMDD)Program, CARE began the FEMME Project in 2000 to increase access and utilization ofemergency obstetric care (EmOC) services for the approximately 48,000 pregnantwomen in the northern provinces of Ayacucho. Methods: The project targeted 5facilities with a comprehensive package of interventions designed to improvecapacity to provide quality EmOC services and to promote a human rights approachin health care. Key program activities included improvements in infrastructure,human resources capacity development, development of service standards andprotocols, quality improvement activities, and promoting a rights-based approach tohealth. Results: By the end of the project, northern Ayacucho had 6 functioningEmOC facilities: 3 comprehensive (including a non-FEMME project facility) and 3basic. This exceeds the UN minimum recommendation of 5 EmOC facilities per500,000 population. Other changes in the UN process indicators indicate anincrease in quality and utilization of EmOC services. Met need for EmOC

International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2006) 92, 299—307

5 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd.

egional de Salud (MoH at the regional level); FEMME, Foundations to Enhance Management ofnt of Peru; IMP, Instituto Materno Perinatal; MoH, Ministry of Health; RHA, Regional Hospital of

589 2624.g (M. Kayongo).

M. Kayongo et al.300

increased significantly from 30% in 2000 to a high of 84% in 2004. Case fatalityrates declined and the number of maternal deaths in the entire regiondeclined. Conclusion: CARE’s work in Ayacucho made an impact on policies andprograms related to EmOC throughout the region. Within CARE, projectexperiences have supported maternal health programs particularly in the LatinAmerican/Caribbean region.D 2005 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Published by ElsevierIreland Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction and background

CARE’s maternal health program in Peru is set in thenorthern region of Ayacucho situated in the sierra atelevations from 2500 to 4000 m. This mountainous,isolated and rural region is located southeast of Limaand northwest of Machu Picchu. The geography ofnorthern Ayacucho is diverse and includes the AndesMountains, jungle, and high plateaus. The projectarea consists of the provinces of Huamanga, Huanta,La Mar, Cangallo, Vilcashuaman, Victor Fajardo, andSucre. These provinces are economically linked tothe capital in Huamanga province.

Ayacucho has a young population. Forty-twopercent of its estimated 562,489 people (2003)are b15 years old and 5% are N65. Languagesspoken include Spanish and indigenous Quechua.There are large disparities in education for men andwomen with literacy rates of 82% and 54%, respec-tively. Approximately 65% of the population lives inpoverty with an average monthly income of US$40,about half the national average.

Ayacucho is ranked 20th among the 24 Peruvianregions on health indicators. The crude mortalityand birthrates are 10.7 and 22 per 1000 population,respectively, while the fertility rate is 4.4 and lifeexpectancy is 61.9 years. There are 4.3 physiciansand 5.7 nurses per 10,000 persons, and 3.7 ob-gynprofessionals per 10,000 women of reproductiveage [1]. In 2000 the infant mortality rate was 69 per1000 live births and the maternal mortality ratiowas 560 per 100,000 live births. Ayacucho was theregion with the third highest maternal mortality inPeru [2]. Major direct causes of institutionalmaternal deaths include hemorrhage, pre-eclamp-sia/eclampsia, and infection.

In 1996, the Government of Peru (GoP) initiatedhealth sector reform: services were structured in asystem of networks and administration was sharedwith locally elected committees called Local Com-munity Health Administration. In the region ofAyacucho the Ministry of Health (MoH) administersa network of 8 hospitals, 44 health centers, and 308health posts. The Regional Hospital of Ayacucho(RHA) is the referral hospital for northern Ayacucho

while the DIRESA (Direccion Regional de Salud-MoHat the regional level) serves as the Regional HealthDepartment of the national MoH system.

In Ayacucho, the ratio of hospital beds to 100,000inhabitants is 8.2 compared to 143.3 for Peru as awhole [1]. Nonetheless, health facilities in the regionhave received significant inputs during the past 6years (1998—2004) from 2 national bi-laterallyfunded projects. Project 2000 was a USAID-sponsoredmaternal and child health project that focused onimproving the quality of existing health care facili-ties and increasing their use. The GoP Basic Healthfor All Program has been instrumental in organizinghealth services into a more efficient micro-networksystem, expanding hours of operation to 12 or 24 h,increasing the number of staff at all health facilities,and instituting performance based evaluation.

In spite of this support, community use of healthservices, particularly obstetric care, was not uni-versal. In Ayacucho, it was estimated that 58% ofbirths occurred in health care establishments whileprenatal care coverage (N1 visit with a skilledattendant) was 81% [3]. Factors that limited theuse of maternal health services include the poorquality and inefficiency of the services, especiallyat addressing obstetric emergencies. While healthproviders received little support and suffered frompoor management systems they, in turn, gave littleattention to clients’ needs and show little respectfor local cultures. The factors led to women’sreluctance to use the services [4].

1.1. Objectives and design

With support from AMDD, CARE initiated the FEMME(Foundations to Enhance Management of MaternalEmergencies) Project in 2000 and sought to increaseaccess, availability and utilization of emergencyobstetric care (EmOC) services for approximately48,000 pregnant women in the northern provincesof Ayacucho. FEMME did not create new facilitiesbut addressed availability by upgrading existingfacilities into functional units that could provideeither comprehensive or basic EmOC services. Theproject targeted 5 facilities: the RHA, 2 smaller

Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru 301

hospitals at San Francisco and Cangallo, and healthcenters at Vilcashuaman and Tambo. Sites werechosen based on their geographic location. SanFrancisco is located in the jungle on the borderwith the region of Cusco and also provides criticalservices to cusquenos. In 2000, San Franciscoprovided erratic obstetric surgery and occasionalblood transfusions without the security of a bloodbank. Cangallo served a more administrative rolefor the DIRESA than it did a patient care center forneighboring smaller facilities; women who sus-pected an obstetric emergency traveled directlyto RHA several hours away. The two health centershad strong ties with their rural communities,increasing our motivation to invest in them.

2. Methods

As with other projects supported under the CARE/AMDD collaboration, overall project design andimplementation was guided by the bImplementationStages FrameworkQ that emphasizes the following askey building blocks for the establishment of EmOCservices [5]:

! improvements in infrastructure and facility set-up;

! data collection and information systems;! staff development and placement, quality im-provement and supervision.

In addition to these building blocks, the projectaddressed the referral and communication systemand the mobilization of civil society.

2.1. Infrastructure improvements andfacility set-up

Facility set-up, including adequate infrastructure,equipment and supplies, is crucial to the provision ofquality EmOC services. Due to Peru’s relatively highlevel of socio-economic development, the infra-structure improvements were less significant thanthose undertaken for CARE’s work in Africa. Recon-struction efforts focused on the specific needs of thevarious health facilities. The RHA received supportfor minor renovations, for example, placement ofelbow taps for sinks outside the operating room andsmall modifications to the obstetric wards, creatinga more efficient working environment for providersand more privacy for patients. Hospital staff alsorequested an intermediate intensive care unit forcritically ill women undergoing treatment for ob-stetric complications. This renovation was co-fi-

nanced by the hospital and FEMME. The project alsointervened with the MoH to provide emergencydrugs such as magnesium sulfate, antihypertensivesand other basic equipment and supplies.

Other facilities carried out renovations too.These involved reconstruction of ramps and entry-ways at the emergency entrances for the twohealth centers. In Vilcashuaman and San Francisco,renovations included providing separate rooms forgeneral and obstetric emergency admissions alongwith aesthetic improvements to the in-patient andemergency receiving areas. The health centers alsocreated a separate space for radio communicationthat facilitates the referral system.

2.2. Data collection and information systems

One of the most important interventions at thefacility level was the development of a moreefficient and systematic mechanism for record-keeping and data collection. Before the FEMMEProject, health facilities used approximately 20different registers for obstetric patients. Theproject team assisted the EmOC centers to stan-dardize and streamline patient registers for theentry and tabulation of key maternal and newborndata. The goal was to get health personnel in thehabit of monitoring the availability and use ofEmOC and to make decisions for improving thequality of services. There are now only 3 registersfor collecting information on emergency treat-ment, prenatal care, and delivery. These registriesare now used throughout the region. To facilitatedata analysis, information on obstetric complica-tions was added to the registers and the analysis ofmaternal deaths was refined by separating indi-rectly from direct causes. These data also wereused to support project monitoring every 6 monthsusing the UN process indicators.

2.3. Staff development and placement

FEMME’s interventions were also designed to im-prove the technical capacity of staff at the 5facilities through advanced clinical training inemergency obstetric interventions and use ofstandardized protocols. From 2001—2002, 42 physi-cians, midwives and nurses participated in anintensive 2-week training program at the MaternalPerinatal Institute (IMP or Instituto Materno Peri-natal) in Lima, with financial support from FEMME.

2.3.1. TrainingA high turnover rate of trained personnel was andremains a major challenge for the health system in

M. Kayongo et al.302

Ayacucho. Because training in Lima is costly, theproject worked with the IMP and the DIRESA todevelop a regional training centre at RHA, whichwas accredited by the IMP in 2003. The specialistswho originally trained in Lima enthusiasticallysupported an on-going clinical training programfor physicians, nurses, midwives, and more recentlyfor technicians and anesthetists. Training sessionsare for 15 days with on-call duty. After an analysisof the causes of maternal death, the treatment andprevention of postpartum hemorrhage receivedspecial emphasis in the trainings. Checklists areused to monitor performance and competency.Trainees produce a work plan that is implementedwhen they return to their place of work. Trainingincludes subsequent supportive supervision to en-sure actual service delivery at all facilities accord-ing to international standards and guidelines.Between 2002 and 2003 PARSALUD (an InternationalDevelopment Bank funded project that supportshealth reform in Peru) invested heavily in thetraining of providers and staff from the DIRESA. Atotal of 204 professionals were trained (59 physi-cians, 93 midwives and 52 nurses).

As a result of these interventions, RHA staff hasbecome increasingly motivated and enthusiasticabout their improved capacity to respond to obstetricemergencies. Two physicians are on call 24 h a day toassure adequate and prompt emergency response.New procedures such as vacuum extraction (and thenecessary equipment) have been re-introduced tosupport the management of prolonged/obstructedlabor. Other achievements include teachingmidwivesat the RHA and throughout the region new practicessuch as activemanagement of the third stage of labor.

Another benefit of the training has been theimproved relationships between staff at RHA andperipheral health centers. Many of the professio-nals who make referrals to RHA or who accompanyreferrals are people who have trained at RHA. Thepersonal familiarity from both sides has led to amore agile and positive referral system. Althoughthe evidence is only anecdotal, a receptive envi-ronment has replaced one that was sometimeshostile.

2.3.2. Staff placementPlacement of trained staff was coordinated withthe DIRESA to ensure a wide distribution oftechnical capability to resolve obstetric emergen-cies. Staffing was a particular challenge at thehospitals of San Francisco and Cangallo. At SanFrancisco the availability of a surgeon and ananesthetist was erratic for several years. Thecombination of a determined hospital medicaldirector and the DIRESA enabled the hiring of more

permanent staff. Infrastructure rebuilding at Can-gallo led to the staffing of specialists there too. Bythe end of the project, both facilities were staffedwith specialists and the capacity for obstetricsurgery had increased.

2.3.3. Development of protocols and standardsfor careIn addition to imparting clinical skills, the trainingstrongly emphasized adherence to evidence-basedcare. FEMME and the DIRESA sponsored the devel-opment, design and publication of protocols titledbGuidelines for the Management of ObstetricEmergenciesQ (Guıa de Atencion de EmergenciasObstetricas) [6]. Using a participatory approach,FEMME brought together providers from the healthfacilities in Ayacucho, the RHA, and national levelstaff from IMP to develop the EmOC Protocols. Thedevelopment of the protocols was based on 3criteria: (1) they were evidence based; (2) theyspecified the competencies/ functions by cadre ofstaff and level of facility; and (3) they outlined thestep-by-step process in the management of obstet-ric problems.

The protocols were designed following a reviewof national and international standards and guide-lines. Thereafter a validation process was under-taken during which the guidelines were assessed indifferent facilities for acceptability. With the thirdedition, the regional government passed a law thatrecognizes these as the official EmOC protocols,and promotes EmOC as a critical component of anysafe motherhood intervention in the region. Afourth edition includes a section on evidence basedantenatal care (a combined effort between pedi-atrics and the ob-gyn department) and the essen-tial steps of normal delivery.

Today, the Guidelines are used throughout theregion and are increasingly shared with otherregional DIRESAs. The IMP trainers also continueto use the Guidelines in their training in EmOC. Thesuccess of these protocols has motivated thedevelopment of a parallel series for newborn care.

2.4. Improving quality and externalsupervision

2.4.1. Quality improvement approachesIn addition to clinical training and the developmentof protocols, quality of care was enhanced throughthe use of Criterion-Based Audits (CBA), a qualityimprovement approach that compares clinical andmanagement practices with set standards andcriteria [7,8]. The Guidelines are the technicalreference from which to draw the criteria. Audit

Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru 303

empowers health workers to address locally iden-tified problems utilizing a step-by-step process tofind appropriate solutions and improve practice.Case reviews of near misses and maternal deathsare now performed regularly as a learning tool forstaff at rural health centers and the RHA.

2.4.2. Supportive supervisionExternal supportive supervision and on-site qualityimprovement processes were used to enhanceefficient service delivery. Project staff conductedmonthly supervisory visits to the health facilities.Each visit typically included an inspection of thefacility with a checklist to assess facility readiness,a staff meeting to prepare monthly managementwork plans, and a discussion of case managementprocedures. Supervisory visits often included atraining component on topics such as infectionprevention, thereby contributing to capacity build-ing among staff and an increased commitment toquality service delivery. The IMP provided signifi-cant supportive supervision to RHA staff, whosubsequently have assumed greater supervisoryresponsibility locally. Today RHA staff performsthe role of tutor to individual facilities throughoutthe region. This participatory mode of supervisionserved to improve supervisor—employee relation-ships, build trust, and support problem solving.

Staff visits from AMDD and CARE (Lima andAtlanta) encouraged the EmOC facilities to updateskills and procedures, improve the client—providerrelationships and quality of care based on a humanrights approach.

2.4.3. Promoting human rights approachIn addition to these interventions, the project useda rights-based framework to support qualityimprovements and increased access to services.The project worked with staff to address keybarriers that women in the community had identi-fied as limiting their use of existing care. At thefacility level, this involved various initiatives, suchas the specific effort to provide non-discriminatoryservices to local cultures (i.e. the indigenouspeople). At the RHA and 2 of the health centers,new signs were designed and put in place to provideaccurate information on health services. This wasalso done in the local language to address the needsof the non-Spanish speaking members of thepopulation. In the health center of Vilcashuaman,a community survey found that women preferredvertical to horizontal birthing positions. The healthteam then designed birthing chairs which enabledwomen to adopt different positions. They encour-aged family members to accompany women duringchildbirth in a manner similar to traditional home

births. Other facilities have now acquired birthingchairs. Nearly all the facilities redesigned theirlabor and delivery wards and placed curtains toensure privacy for women throughout the processof childbirth. At RHA in response to women’scomplaints about no food or cold food after hours,they bought a microwave oven. Women’s namesappear at each bedside and staff refers to womenby their names instead of their bed numbers.

These innovations make the services more cli-ent-centered and acceptable. Ongoing communityinterventions on human rights have empowered thecommunity to demand that the health system beaccountable to the people it serves.

2.5. Referral and counter-referral system

Although not directly instigated by FEMME, anotherinitiative that strengthened the health system wasthe referral and counter-referral mechanism toensure continuity of care for women. The systemwas established in January 2003 as a joint effortamong the DIRESA, the RHA and the Assistance toDispersed Communities Project (Proyecto de Aten-cion a Comunidades Dispersas or PAC). The Dutch-funded PAC collaborated with the MoH to improveservice provision in rural areas of Peru. The referralsystem includes procedures and policies for com-munication between health centers and the RHA toprepare for the arrival of an urgent case, ensuretransportation and clinical stabilization of patients,accompaniment during referral, and follow-up ofeach case. At the RHA, attendants are encouragedto stay at the hospital with the referred patientsand this professional courtesy has improved com-pliance with the referral system.

The system has functioned for almost 2 yearsnow, and FEMME, together with RHA staff, launcheda contest for the most dramatic and best docu-mented referral process. Another competition isplanned for 2005. This initiative complemented thegoals of the project by publicizing cases wherehealth personnel and the community worked suc-cessfully to save a woman’s life. The publicrecognition of the winning facilities has personallymotivated staff and is in stark contrast to thepunitive environment of only 5 years ago.

2.6. Community and civil societyinvolvement

The FEMME Project worked with community groupsto form local committees that complemented workat the 5 facilities. The main purpose of thesecommittees was to enlist community participation

M. Kayongo et al.304

and involvement in addressing maternal mortality,especially in overcoming many of the barriersexperienced during Delays I and II (making thedecision to seek medical attention and actuallyreaching that care) [9].

The committees in the rural areas includepersonnel from each health facility and represen-tatives from local NGOs, political authorities andwomen’s groups. They are responsible for review-ing maternal deaths, mobilizing local actors toprevent deaths, and they help families understandthe need for modern medical care in the event ofan emergency. Joint planning to arrange transportto the referral hospital is done in coordination withlocal authorities and families. In some cases,committees have worked with the police and themilitary to provide emergency transport.

At the regional level a Multi-Sectoral Committeefor the Reduction of Maternal Mortality was formedin December 2002. Their first action was to launcha contingency plan with support of the DIRESA toensure that all hospitals, health centers and postshave staff capable of providing EmOC during theholiday season and vacation periods rather thanleave health centers with only auxiliary health staffto cover emergencies.

The membership of the regional Multi-SectoralCommittee is diverse and includes representa-tives from the University of Ayacucho, its Schoolof Nursing and Midwifery, the police and armedforces, municipal officials, regional governmentofficials and various civil society organizations.Members have created task forces to managedifferent activities of the committee. CAREserves as the secretariat to the committee,which has facilitated organization and helped toconsolidate the committee into a solid regionalorganization.

2.7. Partnerships

CARE’s most important partners in the FEMMEProject have been the IMP in Lima, the AyacuchoDIRESA and the Regional Hospital. The Institute isthe policymaking and normative body for maternaland perinatal health in Peru. There are 3 mainways in which the participation of the Institutewas crucial: (1) technical assistance for the designof the Guidelines for the Management of ObstetricEmergencies, (2) training, and (3) supervision ofthe training programs and services in general. TheRHA training programs have also benefited the IMPin their desire to establish regional trainingcenters. Ayacucho has been their first regionalcenter.

The close relationship between the DIRESA andCARE has enhanced the institutional acceptabilityof FEMME activities and innovations. The partici-pation of DIRESA personnel in all aspects of theproject and the allocation of material resources hasincreased the sustainability of the FEMME activi-ties. The project model has now been transferredto the south of the region and has influenced howother donors spend their resources.

The RHA is an essential partner because of itsrole as the regional referral hospital, a trainingcenter, and for its new role in supervising andmentoring staff at the basic and non-EmOC facili-ties. The School of Nursing and Midwifery at theUniversity of Ayacucho has approached CARE forassistance to improve the curriculum for nurses andmidwifes. CARE has supported the university toinclude life saving skills as an essential componentof their midwifery curriculum. Both the RHA andthe School of Nursing have also provided leadershipand support for the activities of the Multi-SectoralCommittee on Maternal Mortality.

CARE played the role of broker in bringingdifferent partners together to work towards reduc-ing maternal deaths in the region. Prior to FEMME,these institutions rarely collaborated with eachother, and certainly did not strategize together toreach a common objective. Several synergies aroseout of the partnerships as changes were made fromthe bottom up and then formalized in regionalpolicies and procedures. The most dramatic exam-ple is the development of the Guidelines for theManagement of Obstetric Emergencies. Each part-ner made a contribution: FEMME organized meet-ings and workshops, arranged for the participationof expert consultants and facilitated communica-tion; professional health staff provided the officialapproval of the guidelines and distributed them toall health facilities in the region.

FEMME also became a resource for program-matic changes within CARE itself as well as aresource for other CARE offices outside the region.Within CARE the FEMME experiences have beenshared with other maternal health programs, andfield visits have been organized for staff fromCARE projects in Nicaragua, Guatemala, Bolivia,and with representatives from the University ofCuenca, Ecuador.

3. Results

This section highlights the changes in the availabil-ity and utilization of obstetric services during thelifetime of the project using data collected fromthe biannual monitoring system.

0%10%20%30%40%50%60%70%80%90%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004Year

Ind

icat

or

Proportion of all births in project facilities

Met Need for EmOC

Cesarean rate

Figure 1 UN process indicators: Trend data over 4years, Ayacucho, Peru.

Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru 305

3.1. Availability of EmOC services

The UN process indicators recommend a minimumof one comprehensive EmOC facility and 4 basicEmOC facilities per 500,000 inhabitants [10]. Thebaseline facility survey of 2000 covered 31institutions. Comprehensive EmOC was availableat the RHA and basic care at two hospitals, bothof which could perform obstetric surgery (if onlysporadically in the case of San Francisco), butneither had a blood bank. Thus, the population of500,000 had access to 3 EmOC facilities ratherthan the recommended 5.

In addition to the RHA, the project targeted SanFrancisco to become a fully functioning compre-hensive EmOC unit. By 2004 San Francisco had a

Table 1 Emergency obstetric care services: availability a

Baseline (Year 1) 2001 (Y

Population 527,463 536,430Expected number of deliveriesa

(Live Births) 11,604 11,801Expected numberof complications

1741 1770

Actual data for five project facilitiesb

Total number ofdeliveries

3002 2868

Total number ofcomplications

530 596

Number of cesareansections

450 597

Maternal deaths 9 10

Process indicators for five project facilitiesc

Proportion of all births inproject EmOC facilities

25.9% 24

Met need for EmOC 30.4% 33C/Section rate 3.9% 5Case fatality rate 1.7% 1a Crude birth rate is 22 per 1000 (Peru DHS 2000) and the populab Data presented for only the five facilities supported by CARETsc Process indicators calculated for the five facilities supported

Vilcashuaman and Tambo Health Centers.

full-time surgeon, a nurse anesthetist and a bloodbank. By 2005 Cangallo hospital provided someobstetric surgery and Vilcashuaman and Tamboprovided basic care. But neither provided assistedvaginal delivery, only RHA performed an occasionalvacuum extraction. Thus, by the end of theproject, northern Ayacucho had 6 functioningEmOC facilities (including one non-project facility):3 comprehensive and 3 basic, more than achievingthe recommended minimum.

3.2. Quality and use of EmOC services

Fig. 1 shows the changes in the other 4 UNindicators that reflect utilization and quality ofEmOC services based on the 5 project facilities.The data show an increase in met need for EmOC,from 30% in Year 1 to 84% in Year 5. The overallincrease in met need is a promising sign, as thisimplies that more women in need of emergencycare are seeking and receiving this service. Whileno changes were observed in the proportion ofbirths in EmOC facilities, a small increase incesarean section rate from 4% in year 1 to 6% inyear 5 was detected. This corresponds with theincrease in the numbers of complications man-aged. There has been a progressive decline in thecase fatality rate (CFR) from 1.7% to 0.1%, whichis in keeping with the UN recommendation of lessthan 1%. The decreases in CFR also suggest an

nd utilization in Ayacucho, Peru

ear 2) 2002 (Year 3) 2003 (Year 4) 2004 (Year 5)

545,549 554,824 564,256

12,002 12,206 12,4141800 1831 1862

2818 3099 3119

922 830 1562

651 459 750

5 4 2

.3% 23.5% 25.4% 25.1%

.7% 51.2% 45.3% 83.9%

.1% 5.4% 3.8% 6.0%

.7% 0.5% 0.5% 0.1%

tion growth rate is 1.7%.FEMME project.by the project—Huamanga (RHA), San Francisco, Cangallo,

28

3

20

1

17

2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2000 2002 2004

Direct Indirect

Figure 2 Ayacucho region: Number of maternal deathsby direct and indirect causes, by year.

M. Kayongo et al.306

increase in the quality of care at the facilities(Table 1).

Fig. 2 shows progress in the reduction ofmaternal mortality for the entire region of Ayacu-cho (including facilities not supported by theproject). It shows a dramatic decrease in thenumber of maternal deaths due to direct causesbetween 2000 and 2004. Deaths due to indirectcauses have not changed significantly during thistime period.

4. Discussion

FEMME interventions have contributed to reducingmaternal mortality throughout Ayacucho. Earlierprograms are likely to have contributed too such asthe Health Sector Reform Project, Project 2000,and the establishment of a Maternal InsuranceProgram by the GoP in 2000. Previous programinterventions in the area had resulted in a largeincrease in the number of health facilities but theseservices lacked adequate capacity and quality toaddress obstetric complications. Often they wereunresponsive to the specific cultural needs of thewomen served which limited the utilization ofthese services.

FEMME was designed to reduce the high levelof maternal mortality in the rural region ofAyacucho. The main interventions were to buildthe functional capacity of existing facilities toprovide quality EmOC services adapted to thelocal needs, and to promote a human rightsapproach to health service delivery. Progress hasbeen made in increasing the availability, qualityand utilization of EmOC services. Emergencyobstetric care is offered 24 h a day, 7 days aweek, at all targeted facilities for a population ofapproximately 48,000 pregnant women. The indi-cator for use of obstetric services by women mostin need of emergency services (met need)increased significantly from 30% in Year 1 to

84% in Year 5 and the number of maternal deathsdecreased in the entire region of Ayacucho.Although we cannot provide direct evidence forthis, we believe that the interventions at theproject sites, especially at the main referralhospital, made a significant contribution.

5. Conclusions

CARE’s work in the Ayacucho region of Peruprovides some useful lessons for programs workingto improve maternal survival. The scientificevidence is very clear on what is required to savewomen’s lives, and the technology has beenavailable for decades. Yet it can be challengingto apply this knowledge to result in improvedhealth outcomes for women. Access to qualityEmOC is critical to saving women’s lives andmaking this care available requires functionaland organized service delivery systems. Increasedfunding and support are required to address thewide array of challenges faced by many healthsystems. CARE supported the implementation of acomprehensive package of interventions thatincluded building staff capacity and competence,strengthening management systems, promotinghuman rights in health care delivery and devel-oping partnerships and policies that promoteEmOC.

Besides financial resources, greater collabora-tion between donors, civil society and governmentsis critical. CARE worked to bring key partnerstogether in this effort: the Ayacucho HealthDepartment, the Regional Hospital of Ayacuchoand the National Maternal-Perinatal Institute.These factors contributed to the accomplishments,and the enhanced partnership will facilitate thesustainability of program interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding and technical support for this project wasprovided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundationthrough the AMDD program at Columbia University.We would like to extend our thanks and appreci-ation to the staff of the Regional Hospital ofAyacucho and the dedicated physicians, nurses andmidwives of the facilities at Tambo, San Francisco,Cangallo and Vilcashuaman for their enthusiasmand commitment to improving health care for thewomen in Ayacucho. Special thanks are extendedto the staff and colleagues at the InstitutoMaterno Perinatal in Lima for the continued

Strengthening emergency obstetric care in Ayacucho, Peru 307

technical support and encouragement they pro-vided to the project staff. We would also like tothank the Regional Ministry of Health (DIRESA) inAyacucho that has become a great partner andsupporter of CARE’s work in the region. Finally wethank the AMDD staff for the editorial supportprovided for this paper.

References

[1] UNDP. Human development report. New York7 UNDP; 1999.[2] Health System Country Profiles. Pan American Health

Organization. 1999. Retrieved from http://www.lachsr.org/documents/healthsystemprofileofperu.

[3] Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica e Informatica. EncuestaDemografica y de Salud Familiar 2000 Peru. INEI, DHS,Macro, USAID, UNICEF. Lima, Peru 2001.

[4] Leslie J, Gupta GR. Utilization of formal services formaternal nutrition and health care. Washington (DC)7

International Center for Research on Women; 1989,February.

[5] Gill Z, Bailey P, Waxman R, Smith JB. A tool for assessingdreadinessT in emergency obstetric care: the room by roomdwalk-throughT. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;89:191–9.

[6] Guıa De Atencion De Emergencias Obstetricas. GobiernoRegional de Ayacucho, Ministerio de Salud, DireccionRegional de Salud, CARE, Instituto Materno Perinatal;2002.

[7] World Health Organization. Beyond the numbers, reviewingmaternal deaths and complications to make pregnancysafer. Geneva7 WHO; 2004.

[8] Averting Maternal Death and Disability Program. AMDDImproving emergency obstetric care through criterion-based audit. New York7 AMDD, Columbia University;2002.

[9] Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality incontext. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110.

[10] UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA. Guidelines for monitoring theavailability and use of obstetric services. New York7UNICEF; 1997.