Smith, D.M. (2013) Mainland Greece (Prehistoric). Archaeological Reports 59, 22-34.

Transcript of Smith, D.M. (2013) Mainland Greece (Prehistoric). Archaeological Reports 59, 22-34.

ARCHAEOLOGY IN GREECE 2012–2013

edited by Zosia Archibald

INTRODUCTION by Catherine Morgan

THE WORK OF THE BRITISH SCHOOLAT ATHENS, 2012–2013by Catherine Morgan

OVERVIEW: A CLOSER LOOK AT THE‘REMARKABLE DECADE’by Zosia Archibald

AN OVERVIEW OF RECENTRESEARCH IN MAINLAND GREECEby Zosia Archibald

MAINLAND GREECE (PREHISTORIC)by David Smith

THESSALY (PREHISTORIC TO ROMAN)by Maria Stamatopoulou

CRETE (PREHISTORIC) by John Bennet

CRETE (IRON AGE TO HELLENISTIC)by Matthew Haysom

THE AEGEAN ISLANDS(PREHISTORIC TO ROMAN)by Zosia Archibald

ARCHAIC SANCTUARIES OF THECYCLADES: RESEARCH OF THELAST DECADEby Alexander Mazarakis Ainian

RELIGION AND CULTURE IN LATEANTIQUE GREECEby Rebecca Sweetman

FURTHER BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX OF SITES

ABBREVIATIONS

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPORTSfor 2012 2013

CONTENTS

1

3

11

12

22

35

56

68

76

96

103

113

114

119

1

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0570608413000021Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Liverpool Library, on 16 Feb 2018 at 11:01:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

Archaeological Reports is published by the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies(www.hellenicsociety.org.uk) and the British School at Athens (www.bsa.ac.uk) for theirsubscribers. ‘Archaeology in Greece’, the only annual review of archaeological work inGreece published in English, is based upon Archaeology in Greece Online, a rolling serviceof reports compiled by the Directors of the British School at Athens and the École françaised’Athènes, freely available at chronique.efa.gr.

Executive EditorRichella Doyle

Production EditorGina Coulthard

COPYING

This journal is registered with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive,Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Organizations in the USA who are registered with C.C.C. maytherefore copy material (beyond the limits permitted by sections 107 and 108 of U.S.Copyright law) subject to payment to C.C.C. of the per-copy fee of $15. This consent doesnot extend to multiple copying for promotional or commercial purposes. Code 0570-6084/2013. ISI Tear Sheet Service, 3501 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA isauthorized to supply single copies of separate articles for private use only. Organizationsauthorized by the Copyright Licensing Agency may also copy material subject to the usualconditions. For all other use, permission should be sought from the Cambridge or from theNorth American Branch of Cambridge University Press.

This journal is included in the Cambridge Journals Online service which can be found atjournals.cambridge.org.

Cover illustration: Messene: orthostate block with a relief of a lion. © ASA.

This journal issue has been printed on FSC-certified paper and cover board. FSC is anindependent, non-governmental, not-for-profit organization established to promote theresponsible management of the world’s forests. Please see www.fsc.org for information.

Printed in the United Kingdom at Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow

© Authors, the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies and the British School atAthens 2013

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0570608413000021Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Liverpool Library, on 16 Feb 2018 at 11:01:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

DAVID SMITH22

28. Olympia, Sanctuary of Zeus: Archaic gorgoneionshield device. © DAI.

29. Olympia, Sanctuary of Zeus: decorative furniturecover. © DAI.

the Late Antique period) and beneath a packing layer filledwith Classical and Hellenistic sherds, and a further ashdeposit, the excavators came across a red coloured floor,first encountered in 2011 (the floor of a potter’s kiln?). Avariety of metal artefacts was discovered mainly ironobjects, together with some sheet bronze, including anArchaic Gorgoneion shield device (Fig. 28), furniture(Fig. 29) and utensils. The northeast corner of thegymnasium (excavated in 1880 and 1936, and subsequently buried) and the passage between the east and northstoas were cleaned, in cooperation with the 7th EPCA, inpreparation for the planned excavation of the gymnasium.

ReferencesLang, M. (1990) Agora XXV, Ostraka (Princeton)Seltman, C. (1924) Athens: Its History and Coinage before

the Persian Invasion (Cambridge)

MAINLAND GREECE (PREHISTORIC)David SmithSchool of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology,University of Liverpool

IntroductionThe absence of the prehistoric Peloponnese and centralGreece from last year’s new format Archaeology inGreece has provided a slightly larger volume of data forthis year’s report than might otherwise have beenexpected, although the ongoing financial difficultiesfaced by Greece and the recent uncertainty over thestatus of the Archaeological Service itself continue tohave a substantial impact on archaeological research andits dissemination through traditional channels; a problemwhich e publication and webcasting is going some waytoward addressing. In light of this, the decennial volumeof the former Ministry of Culture and Tourism (www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes), the appearance of which was notedin last year’s AG, represents a welcome summary ofexcavation undertaken by the service between 2000 and2010 to add to the newly published volume of ADeltcovering the Peloponnese. Some of this work has previously been reported in AG, although this is certainly nottrue of all.

Several other publications have appeared since 2011which offer new data or new perspectives on theprehistory of the Greek mainland, several of which arediscussed below. Of particular note are two volumeswhich will go some considerable way toward furtheringour understanding of the Early Bronze Age in southernGreece: Daniel Pullen’s The Early Bronze Age Village onTsoungiza Hill (2011) and Elizabeth Banks’ TheArchitecture, Settlement and Stratigraphy of Lerna IV(2013), the companion piece to Jeremy Rutter’s 1995volume detailing the pottery from the Early Helladic IIIsettlement. Banks’ volume, unfortunately, has appearedtoo late to be properly incorporated into this year’s AG.Elsewhere, excavations by the late Spyridon Iakovides(ASA) in the Southwestern Quarter at Mycenae have beenpublished (Iakovides [2013]), while the results of the 1986excavations at Chaeronea have also been presented(Tzavella Evjen 2012), accompanied by a synthesis ofdata from the early investigations of Georgios Soteriades.

The Early Bronze Age also forms the focus of tworecent conference publications. Helike IV. Ancient Helikeand Aigialeia. Protohelladika. The Southern and CentralGreek Mainland (Katsonopoulou [2011a]) includes 18papers delivered at Nikolaiika in Achaea in September2007. Many of the contributions collected here are, as onemight expect, concerned with the site of Helike itself,although the adoption of a wider geographical scopepermits discussion of recent work undertaken at sitesacross the mainland, as well as at Kolonna, on Aegina, andat several sites on Poros. A much more restrictedgeographical focus is evident in the published proceedingsof the round table Early Helladic Laconia held at theNetherlands Institute at Athens in January 2010, which hasappeared as a special edition of Pharos, the Journal of theNetherlands Institute at Athens (volume 18.1[2011 2012]), under the editorship of Christopher Meeand Mieke Prent. Contributions here include new EarlyHelladic material from Kouphovouno, Geraki andPavlopetri, as well as discussion of broader regional developments in the Eurotas valley and the Helos plain.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0570608413000070Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Liverpool Library, on 16 Feb 2018 at 11:00:21, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

ARCHAEOLOGY IN GREECE 2012–2013 23

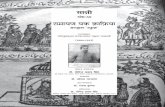

Map 2. Prehistoric mainland Greece. 1. Dikili Tash; 2. Styra; 3. Tsepi; 4. Glyphada; 5. Karatzandagli; 6. Thebes;7. Kastaniotissa; 8. Nera; 9. Bay of Koilada/Franchthi; 10. lria; 11. Atalanti; 12. Midea; 13. Tiryns; 14. Nauplion;15. Velestino (ancient Pherae); 16. Palioskala; 17. Argos; 18. Mycenae; 19. Lerna; 20. Magoula Zerelia; 21. Tsoungiza;22. Lakonis I Cave; 23. Damasta; 24. Menelaion; 25. Agios Vasileios; 26. Kirrha; 27. Sparta; 28. Kastro Lamia; 29. Derveni;30. Agios Georgios, Pleistos valley; 31. Xagounaki; 32. Alepotrypa Cave; 33. Phrantzis; 34. Pharsala, Vasilis; 35. KalamakiaCave; 36. Lygaria; 37. Aigeira; 38. Kompotades; 39. Kassaneva; 40. Amouri; 41. Vlachos; 42. Ambelokipi; 43. Lianokladhi;44. Neo Monastiri; 45. Koutroulou Magoula; 46. Paralia Tolophonos; 47. Astritsa; 48. Helike; 49. DiasergianiStroggylorachi; 50. Antikalamos; 51. Prodromos; 52. Vragiannika; 53. Ayiopigi; 54. Mitopoli; 55. Nafpaktos; 56. LakePlastiras; 57. Trypes; 58. Diasella; 59. Mavropigi Phyllotsairi; 60. Iklaina; 61. Pylos; 62. Theopetra Cave; 63. Romanou;64. Stravokephalo; 65. Mageira; 66. Kafkania; 67. Makrisia; 68. Kalamaki Elaiochori; 69. Lappa; 70. Teichos Dymaion;71. Elis; 72. Triantaphyllia; 73. Haliakmon river; 74. Kechrinia Valtou; 75. Vartholomio Katsiveri; 76. Kouvaras Phyteion;77. Inner Ionian Sea Archipelago; 78. Tzannata; 79. Loutsa.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0570608413000070Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Liverpool Library, on 16 Feb 2018 at 11:00:21, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

DAVID SMITH24

The emergent regional histories of those areas, likeAchaea and Lakonia, which have traditionally beenconsidered peripheral to developments in the ArgolidCorinthia, are a major element of current research on theprehistoric mainland, as borne out in the reports discussedbelow. Equally apparent in this year’s report is theincreasing volume of evidence for communication andinterconnectivity between sites throughout the mainlandand beyond during the prehistoric period. The geographicalextent of these networks has been made clear by thedetailed study of ceramic data, notably from Kolonna andKythera, as well as from Thessaly and central Greece, whiletheir role in the formation and maintenance of social andeconomic practices has been discussed in several recentpublications, among them Carl Knappett’s An Archaeologyof Interaction (2009), Ann Brysbaert’s Tracing PrehistoricSocial Networks through Technology: A DiachronicPerspective on the Aegean (2011) and Thomas Tartaron’sMaritime Networks in the Mycenaean World (2013).

Palaeolithic and MesolithicThe Mani peninsula continues to provide compellingevidence of Palaeolithic activity in the southern mainland.A decade of excavation in the Lakonis I Cave (ID2558),at the eastern end of the Selinitsa valley, has revealed asequence which spans the Middle to Early UpperPalaeolithic. The recovery of a Neanderthal left lowerthird molar from a transitional layer, characterized by atechnologically mixed lithic assemblage and dated to theInitial Upper Palaeolithic (Panagopoulou et al.[2002 2004]; Elefanti et al. [2009]), is an importantaddition to the ongoing debate concerning the degree ofinteraction between Neanderthal and anatomically modernhuman groups in Europe. Mobility over a range of at least20km is suggested by strontium isotope analysis, whichindicates that this individual may have lived in an inlandenvironment as a child (ca. seven to nine years old), beforemoving to the coast (Richards et al. [2008], although seecomments by Nowell and Horstwood [2009]). A possibleflint source for the tools from the cave has been identifiedsome 15km from the site (ID1488).

To this discussion can now be added the MiddlePalaeolithic site at Kalamakia Cave (Harvati et al. [2013])excavated by the EPSNE and the Musée national d’Histoirenaturelle, Paris. Located on the coast, ca. 2km north of thewell known Apidima Cave, Kalamakia has yielded teeth,a cranial fragment and other post cranial elements from atleast six adults and two sub adults, all of whom have beenidentified as Neanderthal, as well as a Mousterian lithicassemblage. It is possible that the caves at Kalamakia andLakonis were utilized by the same groups.

A disturbed burial in a pit has been identified withinUpper Palaeolithic fill at Theopetra Cave (ID3084).Oriented east west, the pit contained ash and charcoal,although the bones themselves were unburned. Theseremains, which probably belong to an adult, are located intrench K11, immediately adjacent to trench I10 where aseverely damaged Upper Palaeolithic skeleton wasrecovered within a pit during earlier excavations(Stravopodi et al. [1999] 271 74). The spatial relationshipand evident similarity between these two burials may wellindicate the observance of specific Upper Palaeolithicburial practices at the cave, of which the only otherexample is a possible Aurignacian female burial fromApidima Cave Gamma.

Some 60km to the south, across the plain of Trikala,surface survey on the shores of the artificial Lake Plastiras(ID3091) has identified Levallois tools and flakes of theMiddle Palaeolithic period, exposed by fluctuations in thewater level. Analysis of this assemblage has identifiedsimilarities with contemporary material from Theopetra(Apostolikas and Kyparissi Apostolika [2008] 36). Middleand Upper Palaeolithic tools and a significant Pleistocenefaunal assemblage are also reported from surface surveyalong the terraces of the Haliakmon river (ID3090), whilean assemblage of blades, flakes and cores was recovered atLoutsa in the lower Acheron river valley (ID3153), anarea known to have been heavily exploited throughout thePalaeolithic period.

To the south, the Inner Ionian Sea ArchipelagoSurvey (ID2620) has identified activity in the island groupfrom the Middle Palaeolithic onward, complimentingpublished Middle Palaeolithic data from Lefkada,Kephallonia and Zakynthos. The relationship betweenactivity on the larger islands, the inner archipelago(Meganisi, Thileia, Kythros, Tsokari, Petalou,Nisopoula, Phormikoula, Atokos and Arkoudi) (Fig.30) and Aitoloakarnania remains unclear, as does theinsularity of each of these smaller islands at various pointsduring the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. Bathymetrysuggests that Kephallonia and Zakynthos were isolatedfrom the mainland as early as the Middle Palaeolithic andrecent work has again raised questions over the potentialrole of the larger islands in the development of seafaringin the Aegean (Ferentinos et al. [2012]). Some of theMesolithic material from the survey has recently appearedin print (Galanidou [2011]).

NeolithicA programme of coring through the tell at Dikili Tashhas yielded a series of C14 dates which places thefoundation of the settlement between 6400 and 6200 BC(Lespez et al. [2013]), while at Mavropigi-Phyllotsairi(cf. AR 58 [2011 2012] 105) AMS and radiometricdating of charcoal, carbonized seeds and human bonesuggests uninterrupted occupation from 6590/64506200/6010 BC (Karamitrou Mentessidi et al. [2013]).Early Neolithic remains are also reported from rescueexcavations in northern Greece at Ayiopigi, a lowmagoula some 5km south of Kokkinos (www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes: 162) and in the area of Lake Karla atVelestino (ancient Pherae) (www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes:154), while excavations carried out on the school site atProdromos, a known Early Neolithic settlement, haverevealed remains of the Final Neolithic period (ID1358;www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes: 165).

Last year saw the conclusion of an eight year researchproject (2005 2012) undertaken at Magoula Zerelia andKaratzandagli and environs by the University ofThessaly and the 13th EPCA, intended to clarify therelationship between the two sites. Karatzandagli wasoccupied from the Early Neolithic, although the two sitesare contemporary during the Middle Neolithic, when theywere separated by a distance of only ca. 800m, close evenfor the very dense settlement patterns of NeolithicThessaly (ID226; www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes: 154). Apreviously unknown Middle Neolithic settlement hascome to light during work on the Volos ring road close toKazanaki. Excavated remains include domestic structureswith hearths and food preparation areas, as well as pottery,

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0570608413000070Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Liverpool Library, on 16 Feb 2018 at 11:00:21, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at