Skeletal evidence of operations on cadavers from Sens (Yonne, France) at the end of the XVTH century

Transcript of Skeletal evidence of operations on cadavers from Sens (Yonne, France) at the end of the XVTH century

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 98:375-390 (1995)

Brief Communication: Skeletal Evidence of Operations on Cadavers From Sens (Yonne, France) at the End of the XVth Century

FREDERIQUE VALENTIN AND FRANCESCO d’ERRICO Institut de Paleontologie Humaine UMR 9948 du CNRS, 75013, Paris (FV), UMR 9933 du C.N.R.S., Institut du Quaternaire, 33405 Talence (Fd’E.), France; and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, CB2 3ER Cambridge, U.K. (Ed%.)

KEY WORDS Autopsy, SEM, Cutmarks, Sawmarks

History of Medicine, France, Skull, Embalmment,

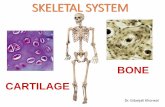

ABSTRACT Human remains giving direct evidence concerning the history of dissection practices are rare. Thirteen cranial fragments which bear evi- dence of having been purposely cut and sawn were discovered in a crypt during excavations undertaken in Sens (Yonne, France). Ceramics date these remains to the period from the end of the XIVth to the end of the XVIth centuries. Nine individuals are represented: one adolescent and eight adults of both sexes. The position of the cutmarks, which were produced by a long, sharp cutting tool, show that the scalp was completely removed from the skull. The sawing, which was done with a large-toothed saw, was both clockwise and counterclockwise in direction. The sawn surfaces reveal a deliberate attempt not to damage the brain. This procedure is compared to that of modern autopsies. The remains from Sens are also compared with several other sawn cranial fragments recently discovered in France and England. Three hypothe- ses are discussed: embalmment, autopsy, and anatomical studies. Analysis of these remains and historical documentation suggest embalmment and/or au- topsy as the probable purpose of the opening of the skull. o 1995 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

During the past few years, evidence of postmortem operations on human remains has been discovered at several archaeologi- cal sites in France and England dating from the XIVth to the XMth centuries. Most of these remains come from French sites (Al- duc-Lebagousse and Pilet-Lemiere, 1986, and personal communication; d’Errico and Valentin, 1987; Gagnaire and Lagrifolle, 1985; Depierre and Fizellier-Sauget, 1989; Lavergne, 1990; Waldron and Rogers, 1988).

Historical sources tell us that the first postmortems were performed in Bologna, probably in the middle of the XIIIth century, a s medicolegal procedures, to investigate deaths that had some forensic significance. None of these early autopsies seems to have been carried out for the purpose of studying

anatomy. Starting from the beginning of the XIVth century, dissection for anatomical studies, as opposed to autopsy investiga- tions, undoubtedly took place with increas- ing frequency, probably limited mainly by the scarcity of bodies. The Italian Mondino de Luzzi (1275-1326) and the French Henri de Mondeville (1260-1325) were among the first medieval anatomists involved in dissec- tions. Afterward, the practice of human dis- section spread quickly across Europe (Wick- ersheimer, 1926; Kevorkian, 1959).

Original anatomical observations using

Received September 2, 1994; accepted May 2, 1995. Address reprint requests to Dr. Francesco d’Errico, UMR 9933

du C.N.R.S., Institut du Quaternaire, Ave. des Facultes, 33405 Talence, France.

0 1995 WILEY-LISS, INC.

376 F. VALENTIN AND F. d’ERRICO

human subjects became possible only when the church relaxed its stand against autop- sying the dead (Singer, 1925). Pope Bonifacio VIII’s Papal Bull of 1299 had established a strong prohibition against dissection. Subse- quently Sixtus IV (pope, 1471-1484) allowed the opening of bodies conditional on the per- mission of ecclesiastical authority. This new attitude accelerated the development of the discipline of anatomy at the end of the XVth century. Even before this time, however, practical needs, including wound care and forensic medicine, must have opened up pos- sibilities for certain kinds of observation and allowed some anatomical probing. Before the XVth century there is in fact evidence of oc- casional dissection; from then onward the supply of cadavers for dissection, though limited, was fairly regular. The right granted to practitioners was confirmed by Clement VII (1523-1524).

Between the XIIIth and the XVIth centu- ries, the development of anatomy was largely a prerogative of the Bologna School. At the University of Bologna, dissection received of- ficial recognition in the Statutes of 1505; the same had previously been allowed in Padua in 1429. In France the most important medi- cal school was at Montpellier, where Guy de Chauliac (1300-1370), former student of Mondino de Luzzi in Bologna, taught anat- omy in the second half of the XIVth century. Public dissections were allowed at Montpel- lier in 1377 and in Paris in 1478.

Historical data about postmortem inter- vention on the body carried out in order to preserve it are rarer than those available on medical practices. Systematic treatises on embalmment began to be published in the middle of the XVIth century (Bellonius, 1553) and became common in the following century (Rivinus, 1655; Clauderi, 1679; Lan- zoni, 1693; Greenhill, 1705). Among the dif- ferent embalmment procedures there de- scribed, several include the opening of the skull by sawing.

The discovery of human remains bearing evidence of dissection allows a direct analy- sis of procedures. During excavations under- taken at Sens in 1985 an important quantity of osteological material was found in the crypt of the chapel of the former Franciscan (or Cordelier) convent (Depierre and Fizel-

lier-Sauget, 1989). Pottery found in associa- tion with the human remains suggest that human bones were probably left in the crypt between the end of the XIVth and the begin- ning of the XVIth century. Among these re- mains are several cranial fragments with traces of cutting and sawing. The aim of our study is to reconstruct the way in which these operations were carried out and to un- derstand their purpose.

MATERIALS AND METHODS The crypt of the Cordelier convent con-

tained the disarticulated remains of about 40 individuals of both sexes and different ages. Thirteen sawn cranial fragments were among these remains. They can be divided into two categories (Table 1) according to whether the sawmarks lie in (1) bones be- longing to the cranial vault, or (2) bones be- longing to the base of the skull. Among the thirteen remains, there are: two skull caps, three frontals of which one includes a part of the temporal, two left temporals, an occipital and the corresponding left and right tempo- rals, two fragments of occipitals, a fragment of a left parietal, a right parietal, and finally a fragment corresponding to a part of the left parietal and a part of the frontal. Taking into account the aspect of the surfaces and the coincidence of the sawing planes, it is possible to identify as belonging to the same individuals a skull cap and a frontal, in one case, and a frontal and a temporal, in an- other case. Thus, the minimum number of individuals is 9. Table 1 shows that adults of both sexes as well as one adolescent are represented. For the two skull caps (n. 2 and 111, the approximate age a t death is esti- mated by taking into account the degree of synostosis of the cranial sutures (Masset, 1982). The other remains are divided into adult and adolescent according to their mor- phology and the degree of synostosis of the sutures. The sex is estimated on criteria pro- posed by Ferembach (Ferembach et al., 1979). These remains do not exhibit evident pathological disorders nor evidence of nutri- tional stress (cribra orbitalia, porotic hyper- ostosis, enamel hypoplasia). The exocranial surfaces are well preserved. Certain pieces, however, show a detachment of superficial

TAB

LE 1

. C

hara

cter

istic

s ob

serv

ed o

n th

e 13

saw

n cr

ania

l fra

gmen

ts fr

om S

ens

(Yon

ne. F

ranc

e)

Cra

nial

C

rani

al

No.

B

ones

ba

sis

vaul

t A

ee

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11

12

Occ

ipita

l T

empo

rals

R

ight

par

ieta

l Sk

ull c

ap

Adu

lt

40-5

0

Lef

t tem

pora

l *

Fron

tal

Fron

tal:

ante

rior

par

t *

Rig

ht z

ygom

atic

Le

ft te

mpo

ral

* O

ccip

ital

Left

pari

etal

Fr

onta

l R

ight

par

ieta

l O

ccip

ital

Skul

l cap

*

Fron

tal:

ante

rior

par

t *

Rig

ht p

arie

tal

Rie

ht te

rnD

ora1

Adu

lt Im

mat

ure

Adu

lt

Imm

atur

e A

dult

Adu

lt

Adu

lt ? 40

-50

I *

Adu

lt

Sex

M -

F?

M?

F?

M? ? ? ? ? ? ? F? ? 7

Posi

tion

Cut

mar

ks

Saw

ing

mar

ks

Saw

ing

of t

race

s Sh

ort

Long

Fi

rst

cut p

oint

R

esta

rt p

oint

di

rect

iona

lity

Fig.

Occ

ipita

l T

empo

rals

R

ight

par

ieta

l Fr

onta

l Le

ft pa

riet

al

Occ

ipita

l L

eft t

empo

ral

Fron

tal

Fron

tal

Left

tem

pora

l O

ccip

ital

Left

pari

etal

Fr

onta

l R

ight

par

ieta

l O

ccip

ital

Fron

tal

Pari

etal

O

ccip

ital

Fron

tal

Rig

ht p

arie

tal

Rig

ht te

mpo

ral

Left

uari

etal

* * * * * * * * * * *

*

* C

ount

ercl

ockw

ise

* 9

* ? ?

C 1 o

c k w

i s e

*

Cou

nter

cloc

kwis

e C

lock

wis

e *

7 ? ?

Clo

ckw

ise ?

13

Lek

par

ieta

l *

Adu

lt 14

O

ccip

ital

Adu

lt - ...

4d

4a

4b

3b

3c

4h

4e

4g

4c

3c

3c

3a

4i

4f

*Sho

rt c

utm

arks

hav

e le

ss t

han

1 cm

of l

engt

h.

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS 379

bone chips and nearly all of the fragments have recent, postdepositional fractures. Two pieces are stained by copper chloride. No other deposits are visible on the exocranial or the endocranial surfaces. The location and orientation of the postmortem traces ob- served on the archeological material are shown on the drawing of each piece. The angle between the sawing plane and the Frankfurt Horizontal is measured.

An experimental autopsy was conducted at the Istituto di Medicina Legale of the Uni- versity of Turin. Its aim was an attempt to reproduce the location and morphology of the traces observed on the archaeological fragments. The body of a 20-year-old man, killed the day before the autopsy in a car accident, was used for this experience. The corpse had not been frozen nor submitted to preservative treatments. The handsaw used in sawing the skull was a hacksaw type with a bIade 1 cm wide and 30 cm long provided with triangularly shaped 1-mm-high teeth.

Several recent studies have demonstrated the importance of microscopic analysis in re- constructing postmortem interventions. In this domain, there have been several meth- odological innovations (Shipman, 1981; Rose, 1983; d’Errico et al., 1982). In studies of human bones, several scholars have at- tempted to interpret the postmortem treat- ment of the corpse as cannibalism (Villa et al., 1986a,b; White, 1992) or defleshing (LeMort and Duday, 1987; During and Nils- son, 1991; Olsen and Shipman, 1994). Our analysis of the cutmarks took into consider- ation our observations on the remains from the autopsy and the criteria established by Shipman (1981), Olsen (19881, Olsen and Shipman (19881, Bromage and Boyde (19841, and White (1992) for cutting produced by lithic and metal tools. The traces left on sawed bone vary depending on the size, set, and shape of the instrument’s blade and its teeth (Symes et al., 1988; Symes and Ber-

Fig. 1. Cutmarks and sawing start points. a: Detach- ment of superficial bone microsplinters produced by the passage ofthe knife blade. b: Fractures (arrows) indicate the direction of the movement of the tool (from left to right). c: Width of the sawing traces reveals the use of a saw with widely set teeth.

ryman, 1989). Observations done by us dur- ing the experimental autopsy suggest that it was possible, on the basis of the orienta- tion of the traces and of their sequence, to reconstruct the direction of the sawing as well as its starting point.

Both cutmarks and sawmarks were ob- served under a transmitted light microscope on nitrocellulosic varnish replicas and under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) on resin replicas. The bone surfaces were cleaned with acetone on a soft brush. The varnish replicas were taken according to the methods already described in the literature (d’Errico et al., 1982). The replicas were pho- tographed with a Leitz Aristophot I1 camera on Agfaortho Professional 25 ASA film. For the study under SEM (Rose, 1983; Bromage, 1985; d’Errico, 1988), rubber moulds were taken with Provil L (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany). The positive replicas, in RBS resin (TL2 Chimie 11230 Chalabre, France), were mounted on a stub, metal-coated under vacuum, and observed on a Cambridge Ster- oscan 250 microscope.

RESULTS Cutmarks

Cutmarks observed on the archaeological remains are thin and linear (Figs. la,b, 2a). They are frequently >1 cm in length. Under the SEM, the striae appear regular, straight, and deep. The edge ofthe striae are either dis- tinct or frayed. A detachment of the first la- mella is often observed (Fig. la). Microfrac- tures, visible on the edges of certain striae, indicate the direction of the movement of the cutting edge (Fig. lb), as described by Bro- mage and Boyde (1984). Cutmarks have been observed on the exocranial surfaces of all the studied remains (Figs. 3,4). Their frequency and their lengths vary from one to another (Table 1). In the naso-orbital region, the fron- tals possess long striae, either parallel or slightly oblique to the sawing surface. They are sometimes distant from it. (Fig. 3a,b). In one case (Fig. 3121, several oblique striae are seen a t the level of the glabella. On the skull caps, the frontal shows short striae placed laterally (Figs. 3c, 4a). Long striae are seenon the squamous portion of the temporal bone. They are close to the sawing plane and paral-

380 F. VALENTIN AND F. d'ERRICO

Fig. 2. a: Sawing start points (A) and cutmarks (B) on the temporal. b: Sawing traces, larger than cutmarks, are seen as groups of parallel striae.

lel to it. Their abundance indicates a repeated passage ofthe blade. On the skull cap, the pa- rietal has both long, thin striae as well as short, deep striae. They are located near the temporoparietal suture (Fig. 4b,c,h) and are particularly abundant 3-4 cm behind the co-

ronal suture. The occipital has several thin striae near asterion (Fig. 4d). In one case, sev- eral thin parallel striae are visible under the inferior nuchal line near the inion (Fig. 4a). No cutmarks were found on the endocranial surfaces.

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS

b

38 1

Fig. 3. Skull fragments discovered at Sens bearing cutmarks and sawing traces. Sketches on the right show the directions followed by sawing. Letters identify remains described in Table 1.

382 F. VALENTIN AND F. d'ERRICO

Fig. 4. Skull fragments discovered at Sens bearing cutmarks and sawing traces. Sketches on the right show the directions followed by sawing. Letters identify remains described in Table 1.

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS 383

Sawmarks The sawmarks a t the start points (i.e., the

initial sawing point on each skull) are gener- ally large, short, and deep. They appear as a network of striae of variable widths (Figs. lc, 2b). Their edges are often irregular. Un- der the SEM, they show a step section (Fig. lc). This can be the consequence of the move- ment of a saw with widely set teeth.

The sawn surfaces present a succession of striae fanning out, sometimes intersecting, oblique, or subparallel to the wall of the skull (Fig. 5a). The pressure exercised by the saw frequently produced the detachment of the endocranial superficial lamella (Fig. 5a). Two indications of the direction of the sawing are the continuous variation of the orienta- tion of the striae (Fig. 4b) and the oblitera- tion of a part of the anterior striae during a major change in the orientation of the saw. False starts in sawing are visible on some remains. They can be differentiated from the cutmarks on the basis of the width of the incision. Even when superficial their breadth is larger than that of a cutmark. All the fragments studied present sawed sur- faces. The sawing plane is always transver- sal (Fig. 6). Seen laterally, it intercepts the frontal between the supraorbital groove and the frontal eminence, the pterion region and the upper part of the squamous portion of the temporal bone, the asterion region, and the region below the inion. The slope of the sawing plane in relation to the Frankfurt Horizontal varies between 16" and 26". The skull of the adolescent has a more oblique sawing plane which joins the frontal emi- nence to the posterior of the basi-occipital and forms a n angle of 41" to the Frankfurt Horizontal.

The sawn surfaces are not uniform. Start points and restart points characterize nearly all the fragments studied. They are abun- dant on the occipital (Fig. 4d,e), present on the temporal, but rarely found on the frontal and the parietal. The traces observed on the sawn surfaces indicate the direction of the movement. The skulls were not all sawn in the same direction: three specimens, ob- served in norma verticalis, show a clockwise movement of sawing, while three others indi- cate a counterclockwise movement. The ini-

tial points of sawing are often difficult to determine. They are abundant, however, in the asterion region but are lacking on the frontal. In two cases, the internal table of the occipital is not totally sawn and the internal occipital protuberance is broken.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The process began by cutting the scalp

with a metal blade. The morphology of the striae suggests the use of a long and very sharp knife blade. The starting point cannot be precisely located, but the abundance of striae on the orbital fragments proves that the initial cut was on the frontal. The pur- pose of this procedure was to expose the ex- ternal surface of the skull by severing the skin from the aponeurosis and the epicranial muscles. The striae are therefore always found below the intended sawing plane. The length of the striae suggests continuous movements of the tool. This behavior was observed on all the pieces studied and dem- onstrates a standard practice. The cutting probably progressed from the frontal to- wards the temporal. The thin striae of the cutting are interrupted in the temporo-occip- ital region. This suggests that the scalp was pulled toward the back of the head. This practice is opposite that followed in modern autopsies, in which a n incision is made from one postauricular region to the other either crossing the occipital either vertically be- hind the vertex, i.e., posterior to the the coro- nal suture (Okasaki and Campbell, 1979; Knight, 1984). After the cutting of the skin, two practices could have been followed: the scalp could either have been completely de- tached, or it could have been folded over a t the level of the neck. The presence of striae under the inion, indicating the section of the occipital muscles, suggests the complete re- moval of the scalp. The practitioner then pro- ceeded to section the epicranial muscles and their aponeuroses leaving short, deep striae on the bone. The cutting of the temporal muscle probably began near the temporal lines progressing towards the parietal and the upper part of the squamous portion of the temporal bone. The autopsy undertaken a t the Istituto di Medicina Legale of Turin demonstrates that this manner of cutting

384 F. VALENTIN AND F. d’ERRICO

Fig. 5. Sawing surface. a: Detachment of superficial bone lamellae on the endocranial surface. b: Superposition of the saw marks shows the direction of movement of the saw, arrows indicate the most recent traces.

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS 385

Fig. 6. Orientation of the sawing planes (S) in relation to the Frankfurt Horizontal (F). The angle for the adolescent is greater (arrows) than those of the adults.

produces a large number of marks. Similar marks were observed on the remains from Sens. Afew short, deep striae on the occipital indicated the sectioning of the epicranial aponeurosis and the trapezius muscle and the complex of spinal muscles. The cutting of the muscles exposed the cranial vault in preparation for sawing the skull.

The sawing most likely began near asterion. At the start, the head was probably positioned on its side, either right or left. It was then turned progressively while sawing. The variability in the direction of the sawing is thus related to the position of the head at the beginning. In modern autopsies, the sawing begins on the frontal with the head resting on a support. The presence of saw traces near the sawing line are probably the result of false starts or slipping of the blade out of the main groove. The saw, as indicated by the width of the cut a t the start points, was large and had widely set teeth. This is also suggested by the fact that the only skull that can be reassembled shows a large gap between the fragments. The sawn surfaces show that the sawing was undertaken in

such a manner as to damage the brain as little as possible. This goal was obtained by regularly modifying the orientation of the saw during the work. The skull cap was not always removed by the use of a saw alone. The fracture of the internal occipital protu- berance indicates, as is frequent in modern autopsies, that the final detachment of the skull cap was produced by percussion or the action of a lever. The operations that fol- lowed are unknown, as they left no traces on the skull.

In conclusion, the skulls from Sens demon- strate a single method of cutting and sawing. This homogeneous approach pleads in fa- vour of a contemporaneity of the remains and even suggests that they could have been the work of a single practitioner or that of a single “school.”

There are certain differences between the remains found at Sens and those found a t other sites (Table 2). The remains from St. Laurent du Puy-en-Velay (Haute-Loire) (De- pierre and Fizellier-Sauget, 1989) show a larger variability in the orientation of the sawing plane. One of them, for example, has

TAB

LE 2

. Sa

wn

skul

ls d

isco

vere

d in F

ranc

e an

d En

glan

d'

Site

N

ame

Type

D

atin

g T

NF

MN

I A

ge

Sex

Ref

eren

ces

Arl

anc

(Puy

de

Dom

e), F

ranc

e Pr

iory

chu

rch

3 3

1 yo

ung

adul

t 1

mid

dle-

aged

1

old

adul

t M

iddl

e-ag

ed

Chi

ld

? ? ? M

?

Gag

nair

e an

d La

grifo

lle (

1985

) D

epie

rre

and

Fize

llier

-Sau

get

(198

9)

Wal

dron

and

Rog

ers

(198

8)

Dep

ierr

e an

d Fi

zelli

er-S

auge

t (1

989)

Aft

er X

th c

entu

ry

? 1

Bar

ton-

on-H

umm

er, E

ngla

nd

Cha

telo

y (A

llier

), Fr

ance

C

hilly

Maz

arin

(E

sson

ne),

Fr

ance

Che

rbou

rg (

Man

che)

, Fra

nce

Glo

uces

ter,

Eng

land

Je

rsey

, Eng

land

Pu

y-en

-Vel

ay (

Hau

te L

oire

), Fr

ance

Cem

eter

y (i

ndiv

idua

l bur

ial)

1

? ?

1

1

Chi

ld

Chi

ld

You

ng a

dult

Old

adu

lt

? ? M

F

Dep

ierr

e an

d Fi

zelli

er-S

auge

t (1

989)

Ald

uc L

ebag

ouss

e (1

986)

W

aldr

on a

nd R

oger

s (1

988)

W

aldr

on a

nd R

oger

s (1

988)

7 7

? ?

1

1

Chu

rch

Cem

eter

y C

emet

ery?

? X

VII

I-X

Mth

ce

ntur

ies

9

? ? 1

1

4 ad

ults

1

child

Adu

lts?

3 ad

ults

2

adul

ts

3 ad

ults

1

adol

esce

nt

? 7 D

epie

rre

and

Fize

llier

-Sau

get

(198

9)

Chu

rch

7 6

5

Stra

sbou

rg (

Als

ace)

, Fra

nce

Sens

(Yon

ne),

Fran

ce

Chu

rch

Cha

pel

End

XV

IIth

cen

tury

End

XIV

th-e

nd X

VIth

ce

ntur

y

6 13

3 9

? M

F ? ?

Lav

ergn

e (1

990)

dErr

ico

and

Val

entin

(19

87)

Dep

ierr

e an

d Fi

zelli

er-S

auge

t (1

989)

'TN

F: l

btal

num

ber

of f

ragm

ents

; MN

I: m

inim

um n

umbe

r of

ind

ivid

uals

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS 387

a sawing plane that passes well below the A and produces a small skull cap; a t the back, a discrepancy of 12 rnm is seen between the start and finish of the sawing. The prac- titioner was, thus, obliged to remove the skull cap by fracturing this zone. The re- sulting gap indicates that the saw pene- trated the brain deeply during the operation. This procedure is different from that at Sens, where the sawing always respected the brain, as far as possible. The sawing of the skulls from Arlanc (Puy de Dome), where the saw was moved tangentially to the cra- nium, is similar to that at Sens. Further- more, another skull, from St. Laurent du Puy-en-Velay, has a discontinuous groove lo- cated 5-20 mm above the sawing plane. This groove, due to its position, is difficult to in- terpret as a cutting of the scalp. It might constitute a marker used to facilitate the sawing. This procedure is unknown at Sens. On the other hand, the only skull from Puy- en-Velay for which cutting is mentioned, presents striae on the frontal. This observa- tion shows that, as a t Sens, the scalp was pulled towards the back of the head.

Since the reconstruction of the prac- titioner’s behavior does not reveal the reason for the opening of the skull, historical sources should be taken into account. Texts from the XIVth to the XVth centuries men- tion such postmortem procedures and justify them for three different reasons: em- balmment, autopsy, or anatomical studies. These three alternatives are discussed below.

Embalmment The practice of embalmment had spread

among the nobility during the second half of the XIVth century. This was the result of the tendency to display the corpses for a long period of lying in state. For example, “Guil- laume de Melun, Archbishop of Sens, is laid in state in the choir on a bed covered by a black pall, face and hands exposed” (BN na fr 7112, Testament of Guillaume de Melun, Archbishop of Sens, page 22). If the body itself was not exposed, then it was replaced by the most lifelike possible effigy.

The remains from Sens belong to a rela- tively large number of individuals, including

against the hypothesis of embalment since it is known that this treatment was particu- larly destined for the male nobility who pos- sessed titles or dignities; “the funerals of women (except when they held an indepen- dent function as did Anne de Bretagne), in- fants and younger brothers had reduced for- malities. It was the bearer of the name or the title, the holder of the family patrimony, who was especially honoured a t his last mo- ments” (Beaune, 1975).

All the sawn frontals from Sens present cutmarks above the superciliary ridge and below the hairline. This may indicate a lack of interest concerning the restitution of the body. It would have left, in effect, a rather visible mark and in the case of repositioning the scalp on the skull cap, the former would have left uncovered a large surface of bone due to the consequential retraction of the scalp. Even if the scalp was stitched, the evidence of the cutmarks would have been very visible. This manner of removing the scalp is not the only one possible. Access to the brain can be achieved without apparent damage to the face; for example, modern au- topsies expose the cranial vault either by pulling the scalp forward after sectioning the scalp on the occipital from one auricular re- gion to the other (generally following the hairline) or by cutting posterior to the coro- nal suture and retracting the scalp forward and backward (Gresham and Turner, 1979; Knight, 1984).

The retraction of the scalp in the frontal region, however, does not disprove the em- balmment hypothesis. This mark could have been hidden by a shroud or a headdress. In fact, nearly all descriptions of the ceremonial dress shown on the effigies of the nobility of this period mention a headdress: crowns, circlets, hats (Beaune, 1975; Lavergne, 1990). Since effigies imitated the dress of the embalmed corpse rather precisely, it is safe to assume that headdresses similar to those mentioned for the effigies could have been worn by the embalmed bodies. Besides defin- ing the social role of the deceased, this head- dress could also have hidden the damage caused by the opening of the skull.

For embalming purposes, it is simpler to saw the skull straight through without pre-

women and an adolescent. This could be used serving the brain, as is the case of one of the

388 F. VALENTIN AND F. d’ERRICO

skulls from Puy-en-Velay. In contrast, on all of the Sens remains the saw was always moved tangentially to the skull. The care taken in this operation indicates that the brain was purposely preserved. No historical document reveals an interest in not damag- ing the brain during embalming and it is known that embalmment was generally ac- companied by the immediate burial of the viscera and the heart which often took place a t another site (Beaune, 1975).

Finally, a number of drugs were used at the time to preserve the body after its treat- ment (Gannal, 1841). No macroscopic resi- dues of such products were observed on the studied remains. However, their presence cannot be dismissed without undertaking systematic chemical testing.

Autopsy The hypothesis of autopsy must be consid-

ered together with that of embalmment since no clear boundaries existed at the time be- tween these two practices. I t is known that during the embalmment the viscera were generally examined in order to identify the death causes (Gannal, 1841). However, post- mortems carried out with the sole purpose of establishing the reason of death were quite rare and usually reserved €or important per- sons in case a doubt remained as to the cause of death-for example, in the case of sus- pected poisoning. Since autopsy was a com- mon adjunct of embalmment and could not be distinguished from it by either the op- erating technique or the burial context, we conclude that autopsy should not be treated as a separate explanation and must be sub- sumed in the embalmment hypothesis.

Anatomical studies Even though i t was held in contempt by

popular opinion, the dissection of corpses during this time was tolerated even outside of medical schools (Huard and Grmek, 1966; Lind, 1975). No school of medicine is known in Sens during the XVth-XVIth centuries, but dissections for a scientific purpose could have been conducted at Sens in a private house. The presence in this town of reputed doctors, such as Jean d’Aillebout and Simon de Provencheres, is known. The former, who had been Henri IV’s private doctor a few

years before his death in 1582, had con- ducted the autopsy of Colombe Chatry (case of an ectopic pregnancy) in 1582. The latter, who died in 1617, had assisted at this au- topsy (Poree, 1920). Several texts and icono- graphic representations (Jean Cousin’s en- graving representing the autopsy of Colombe Chatry, 1582, in Monceaux, 1878) demon- strate the interest of medical circles in Sens in dissection of the human body. All the stud- ied remains from Sens show an interest in the conservation of the brain. This behavior is compatible with their interpretation as the result of anatomical dissections.

If this were the case, one might ask what was the scientific knowledge that anato- mists of that period hoped to acquire through the visual examination of the brain. During the period between the XIVth and the XVIth century, most anatomists accepted the Ga- lenic theory, originally proposed by Erasis- tratus, that the ventricles of the brain were filled with a mysterious substance called an- imal spirit. According to Galen, the animal spirit was formed in the ventricles of the brain by the vital spirit, carried into the blood, and changed in some occult way in which the rete mirabile vascular network a t the base of the brain was somehow involved. The animal spirit then coursed down the hol- low nerves, operated the muscles and con- veyed sensation. Despite his interest in hu- man dissection, Mondino de Luzzi in his book of 1316 still follows Galen’s theory on many points. It is during the XVth century, and especially from the beginning of the XVIth century, that new observations on the brain were carried out, with the result that some Galenic statements were refuted. For example, in his commentary on Mondino’s book, Berengar of Capri denied the Galenic doctrine of the existence of the rete mirabile in humans. A radical change in the knowl- edge of the anatomy of the human brain in- tervened with the work of Andreas Vesalius (1543). In the De Fabrica, the numerous il- lustrations of the brain seen from above are excellent. But Vesalius still included the rete mirabile, which could not have been the re- sult of observations of human dissection. From the functional point of view, Vesalius perpetuated Galen’s system; but his detailed descriptions created the conditions which al-

SKELETAL EVIDENCE OF OPERATIONS FROM SENS 389

lowed later anatomists to discard Galen’s theory. Were the Sens practitioners op- erating under the influence of a new interest for anatomical studies as promoted by Vesa- lius? It is to be hoped that more precise dat- ing of these remains and more extensive comparative collections of dissected remains from medieval and Renaissance times may enable us to answer this question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank G. Depierre for having en-

trusted us with the human remains used in this study and L. Saulnier Pernuit, Curator of the Museums of Sens, for her help. We also thank P. Villa, G. Giacobini and M. Grmek for the critical reading of the manu- script. L. Varetto helped us with S.E.M. and during the experimental autopsy. The work of one of the authors (F. d’E.) was supported by a Postdoctoral grant from the University of Turin and by C.N.R. Founds (C.N.R. 88.03672.15).

LITERATURE CITED Alduc-Lebagousse A, and Pilet-Lemiere J (1986) Les sep-

ultures d’enfants en edifices religieux: l’exemple du cimetiere de l’eglise Notre-Dame de Cherbourg (Man- che). In Actes des 2emes Journees Anthropologiques de Valbonne, pp. 61-68.

Beaune C (1975) Mourir noblement au Moyen Age. Actes du Colloque de la Societe des Historiens medievistes de i’enseignement superieur public. Strasbourg, pp. 125-143.

Bellonius P (1553) De mirabili operum antiquorum praestantia, medicato funere, feu cadavere condito, et medicamentis nonnulis servandi cadaveris sim obti- nentibus. Paris.

Bromage TG, and Boyde A (1984) Microscopic criteria for the determination of directionality of cutmarks on bone. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 65:359-366.

Bromage, TG (1985) Systematic inquiry in tests of nega- tive/positive replica combinations for SEM. J. Mi- crosc. 137:209-216.

Clauderi G (1679) Methodus balsamandi corpora hu- mana. Atlemburgi.

Depierre G, and Fizellier-Sauget B (1989) Ouverture volontaire de la boite crbnienne a la fin du moyen bge et aux temps modernes. Actes des 4emes Journees Anthropologiques. Paris: C.N.R.S., pp. 121-140.

d’Errico F (1988) The use of resin replicas for the study of lithic use-wear. In S.L. Olsen (ed.): Scanning Electron Microscopy in Archaeology. B.A.R. International Se- ries 452. pp. 155-167.

d’Errico F, and Valentin F (1987) Premiers temoignages archeologiques d‘autopsie en Bourgogne (fin XVIeme siecle). Etude microscopique et experiementale. In G. Giacobini (ed.): 2nd Human Paleontology Congress. Abstracts, p. 314.

d’Errico F, Giacobini G, Puech PF (1982) Varnish Rep- lica: a new method for the study of worked bone sur- faces. Ossa 9-10:29-51.

Diderot D, and d’Alembert J (1751) Encyclopedie ou dic- tionnaire raisonne des sciences et arts et des metiers. Paris: 35 vol.

During EM, and Nilsson L (1991) Mechanical surface analysis of bone: A case study of cut marks and enamel hypoplasia on a Neolithic cranium from Sweden. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 84:113-125.

Ferembach D, Schwidetzky I, and Stloukal M (1979) Recommendations pour la determination de l’bge et du sexe sur le squelette. Bull. SOC. Anthropol. Paris 6(13):745.

Gagnaire J, and Lagrifolle E (1985) La crypte de l’eglise Saint-Pierre d’Arlanc (Puy-de-DBme). In Chroniques historiques d’Ambert et de son arrondissement, pp. 20-23.

Gannal J N (1841) Histoire des embaumements et de la preparation des pieces d’anatomie normale, d’anato- mie pathologique et d’histoire naturelle suivi de pro- cedes nouveaux. Paris: Chez I’auteur.

Greenhill T (1705) The Art of Embalming. London. Gresham GA, and Turner AF (1979) Post-mortem proce-

dures. New York: Wolf Medical Publications, Ltd. Huard P, and Grmek M (1966) Mille ans de Chirurgie

en Occident. Paris: Roger Dacosta. Kevorkian J (1959) The Story of Dissection. New York

Philosophical Library. Knight B (1984) The Post-mortem Technicians Hand-

book: A Manual of Mortuary Practice. London: Black- well Scientific Publications.

Lanzoni J (1693) De balsamatione cadaverum. Ferrara. Lavergne J (1990)Vivre auMoyen Age. 30 ans d‘archeolo-

gie medievale en Alsace. Strasbourg: Les Musees de la ville de Strasbourg.

Le Mort F, and Duday H (1987) Traces de decharnement sur un humerus dysmorphique neolithique. Bull. Mem. SOC. Anthropol. Paris. 4(14):17-24.

Lind LR (1975) Studies in pre-Vesalian anatomy: Biogra- phy, translations documents. Philadelphia. Am. Philos. SOC. 6(104):6-47.

Masset, C (1982) Estimation de l’hge au deces par les sutures crhniennes. Doctoral thesis. Paris: University of Paris.

Monceaux H (1878) Une gravure de J. Cousin. L‘enfant petrifie, XVIeme siecle. Bull. SOC. Sci. Yonne 32: 131-132.

Olsen SL (1988) The identification of stone and metal tool marks on bone artifacts. In SL Olsen (ed.): Scan- ning Electron Microscopy in Archaeology. Oxford: B.A.R. Int. Series 452, pp. 337-360.

Olsen SL, and Shipman P (1988) Surface modification on bone: Trampling versus butchery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 15.535-553.

Olsen SL, and Shipman P (1994) Cut marks and peri- mortem treatment of skeletal remains on the North- ern Plains. In DW Owsley and RL Jantz (eds.): Skele- tal Biology in the Great Plains. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 377-387.

Okazaki H, and Campbell FLJ (1979) Nervous system. In Ludwig J (ed.): Current Methods of Autopsy Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, pp. 95-129.

390 F. VALENTIN AND F. d’ERRICO

Poree C (1920) Histoire des rues et des Maisons de Sens. Sens: Duchemin.

Poynter FLN (1958) The History and Philosophy of Knowledge of the Brain and Its Functions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rivinus A (1655) De balsamatione. Lips. Rose JJ (1983) A replication technique for scanning elec-

tron microscopy: Application for anthropologists. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 62t225-261.

Shipman P (1981) Applications of scanning electron mi- croscopy to taphonomic problems. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 376t357-386.

Singer C (1925) The Evolution of Anatomy. London: Kegan, Trench, Trubnerand.

Symes SA, and Berryman HE (1989) Dismemberment and mutilation: General sawtype determination from cut surfaces of bone. Presented a t the Forty-first An- nual Meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, Las Vegas, W.

Symes SA, Guilbeau MG, Falsetti AB, and Harlan CW

(1988) Saw marks on bone: Any way cut it. Presented a t the Fortieth Annual Meeting of the American Acad- emy of Forensic Sciences, San Diego.

Vesalius A (1543) De humani corporis fabrica. Base1 Nachdruck: Culture et Civilisation, Bruxelles, 1964.

Villa P, Bouville C, Courtin J, Helmer D, Mahieu E, Shipman P, Belluomini G, and Branca M (1986a) Can- nibalism in the Neolithic. Science 233:431-437.

Villa P, Courtin J, Helmer D, Shipman P, Bouville C, and Mahieu E (1986b): Un cas de cannibalisme au Neolithique. Boucherie et rejet des restes humains et animaux dans la grotte de Fontbregoua a Salernes War). Gallia Prehist. 29:143-171.

Waldron T, and Rogers J (1988) Iatrogenic paleopathol- ogy. J . Paleopathol. 1(3):117-129.

White T (1992) Prehistoric cannibalism a t Mancos 5MTUMR-2346. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univer- sity Press.

Wickersheimer E (1926) Anatomies de Mondino dei Luzzi et de Guido da Vigevano. Pans: Droz.