Seeing Like a Research Project: Producing “High-Quality Data” in AIDS Research in Malawi

Transcript of Seeing Like a Research Project: Producing “High-Quality Data” in AIDS Research in Malawi

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania]On: 28 September 2012, At: 16:33Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Medical Anthropology: Cross-CulturalStudies in Health and IllnessPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gmea20

Seeing Like a Research Project:Producing “High-Quality Data” in AIDSResearch in MalawiCrystal Biruk aa Brown University Pembroke Center, Providence, Rhode Island, USA

Accepted author version posted online: 07 Nov 2011.Version ofrecord first published: 02 Jul 2012.

To cite this article: Crystal Biruk (2012): Seeing Like a Research Project: Producing “High-QualityData” in AIDS Research in Malawi, Medical Anthropology: Cross-Cultural Studies in Health and Illness,31:4, 347-366

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.631960

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Seeing Like a Research Project: Producing ‘‘High-QualityData’’ in AIDS Research in Malawi

Crystal Biruk

Brown University Pembroke Center, Providence, Rhode Island, USA

Numbers are the primary way that we know about AIDS in Africa, yet their power and utility often

obscure the conditions of their production. I show that quantification is very much a sociocultural

process by focusing on everyday realities of making AIDS-related numbers in Malawi. ‘‘Seeing like

a research project’’ implies systematically transforming social reality into data points and managing

uncertainties inherent in numbers. Drawing on 20 months of participant observation with survey

research projects (2005, 2007–2008), I demonstrate how standards govern data collection to protect

and reproduce demographers’ shared expectations of ‘‘high-quality data.’’ Data are expected to be

‘‘clean,’’ accurate and precise, data collection efficient and timely, and data collected from

sufficiently large, pure, and representative samples. I employ ethnographic analysis to show that

each of these expectations not only guides survey research fieldwork but also produces categories,

identities, and practices that reinforce and challenge these standardizing values.

Keywords AIDS, data, enumeration, knowledge production, Malawi

Numbers are the primary way that we know about AIDS in Africa. Claims such as ‘‘11.9 percent

of Malawians are infected with HIV’’ or ‘‘1.6 percent of the total adult population of Malawi is

infected with HIV each year’’ (UNAIDS 2008; UNGASS 2010) are numerical generalizations

that assume congruence with social reality. Enfolded into these numbers are data collected in

a systematic and standardized way from a distant local population. These data are enlisted into

knowledge claims about the AIDS epidemic that transform a complicated geographic place into

a manageable and mobile form that can circulate globally, sending an efficient abstraction of

‘‘Malawi’’ from the field to a university office to reports for the Malawi National AIDS

Commission. From there, data appear in refereed publications for an international audience,

and ultimately, manifest in UNAIDS compilations of data from Malawi. A nation’s or even a

village’s complexity and dynamism can never be wholly captured by researchers, of course:

much potential information must be ignored or excised when people or places become data

points. But individuals can be surveyed, interviewed, counted, and HIV-tested in order to

CRYSTAL BIRUK is a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University’s Pembroke Center, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Her book manuscript in progress, The Marketplace of Expertise: Producing AIDS Knowledge in Malawi, explores the

politics of knowledge production in international AIDS research in Malawi. Her research interests encompass post-

colonial technoscience, nonknowledge, global health, humanitarianism, transnational queer identities, and the affective

and ethical politics of intervention.

Address correspondence to Crystal Biruk, Brown University Pembroke Center, Box 1958, 172 Meeting St.,

Providence, RI 02912, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

Medical Anthropology, 31: 347–366

Copyright # 2012 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0145-9740 print/1545-5882 online

DOI: 10.1080/01459740.2011.631960

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

generate numbers that are taken as authoritative representations of women and men grappling

with the AIDS epidemic. The power and utility of numbers related to the AIDS epidemic in

sub-Saharan Africa often obscure the nature of their production.

In this article, I focus on the everyday realities of making AIDS-related numbers in Malawi,

illustrating that quantification is very much a sociocultural process (Lampland and Star 2009;

Guyer et al. 2010). Borrowing from James Scott’s (1998) Seeing Like a State, I illustrate how

research projects, like states, simplify people and practices and employ technical tools to trans-

form social reality into information or data points. I show that transformation of rural Malawian

social realities into numbers is governed by standards that take form and are reinforced by every-

day research practices. While many suggest that the knowledge produced by AIDS research pro-

jects misses out on or misrepresents important aspects of sub-Saharan African social reality, I

argue that research projects see exactly what they intend to see; standards of ‘‘high-quality data’’govern data collection, make stability and fixity in representation possible, and work effectively

to manage uncertainty (Lampland 2010:31). Drawing on 20 months of participant observation of

demographic survey research projects working in Malawi (2005, 2007–2008), I move beyond the

assumption that numbers are simply collected from research participants in research projects, and

show that numbers are the products of complex and messy negotiations, exchanges, and relations.

My discussion is based on interviews with project staff and analysis of the tools and instru-

ments utilized by these projects. I demonstrate how standards govern data collection to protect

and reproduce expectations of high-quality data shared by social demographers and audiences

for the knowledge they produce. The data are expected to be ‘‘clean,’’ accurate and precise, data

collection efficient and timely, and data collected from sufficiently large, pure, and representa-

tive samples. I employ ethnographic analysis to show that while these expectations guide survey

research data collection activities, they also produce categories, identities, and practices that

reinforce and challenge these standardizing values.

First, I draw on participant observation of survey design meetings, translation sessions, and

implementation of survey questions to show how accuracy and precision of data collected from

rural households is ensured through practices that anticipate audiences for survey questions.

Second, in order to ethnographically explore the virtue of timeliness and timely data, I illustrate

how the mandate to ‘‘keep time’’ in the field manifests in the gestures, comportment, habits, and

interactions of fieldworkers and research subjects. Next, I show how an expectation of sufficient

sample size, representativeness, and sample purity relies on particular orientations to research

subjects and the adoption of a ‘‘good fieldworker’’ identity by interviewers. Finally, I suggest

that maps, photographs, data entry procedures, and other technical objects help to maintain sam-

ple purity by ‘‘watching over’’ longitudinal samples. I conclude by arguing that the enumerative

practices of demographic AIDS survey research in Malawi effectively manage, rather than eradi-

cate, the uncertainty and contingency inherent in numerical knowledge about the epidemic.

ETHNOGRAPHIC CONTEXT

Malawi is a small, landlocked sub-Saharan African country with a population of 15.4 million

(National Statistics Office [NSO] 2008). Eighty-five percent of its mostly rural population

engages in small-scale farming and depends heavily on rain-fed agriculture to grow maize to

prepare the staple food dish, nsima (World Bank 2009). Malawi is one of the poorest countries in

348 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

the world, with high rates of unemployment and failed structural adjustment programs (SAPs)

instituted by the World Bank and IMF since 1981. Malawi also has high prevalence rates of HIV,

hovering around 11 percent, making it the ninth most infected nation globally (UNAIDS 2009).

The demographic survey research projects described here are situated within a massive infra-

structure of knowledge production, prevention, treatment, and containment that takes AIDS

(amid other health and social problems) in Malawi as a central concern (Sridhar and Batniji

2008; Rottenburg 2009; Morfit 2011). The common vernacular terms for this disease—edzi (avariant on the Anglophone AIDS) and matenda a boma (the government disease)—hint at the

widely shared conception of AIDS as an object of interest for foreign and national experts.

Malawians commonly view their country as ‘‘research saturated’’ or ‘‘over-researched,’’ parti-cularly because of the effect of AIDS research.1

While many surveys do not claim that their findings represent a larger national reality, nor do

they seek to intervene directly into social problems, the numbers that they generate can become

the foundation for proposals to fund interventions pertinent to HIV risk. Relationships among

governments, universities, and NGOs effectively sanction the continual collection of data and

marry research to an optimistic vision for the Malawian nation. The tight link between research-

ers and government, via ‘‘policy-relevant research,’’ has a long legacy; upon conferring degrees

to the first graduates of the University of Malawi, former president Kamuzu Banda stated:

‘‘Malawi has no time for ivory tower speculation . . . [we] need the commitment of [the] academ-

ic elite to the solution of practical problems’’ (quoted in Joffe 1973:517).

METHODS

In Malawi, I spent time with four international AIDS survey research projects working in the

south and center of the country. In this article, I draw primarily on my participant observation

of two longitudinal projects that administered household-level surveys and conducted HIV tests

to samples of 1200 and 4000 rural Malawians over periods of two to three months. In line with

Malawi research guidelines, the foreign researchers leading these projects collaborated with

Malawian researchers at the University of Malawi. Fieldwork teams were comprised of

American and European researchers (intermittently) and graduate students, and locally hired

Malawian supervisors, interviewers, and data entry teams. Both projects studied issues related

to the AIDS epidemic: the role of social networks in responses to AIDS in rural Malawi and

HIV risk factors associated with adolescent development and marriage behavior. These projects

rented buildings located near the villages in the study settings that served as fieldwork offices.

Fieldwork teams left the office early in the mornings (around 6 a.m.) to collect data and returned

by nightfall. I participated in all aspects of fieldwork: trainings for project staff, survey design

meetings, hiring of interviewers, everyday fieldwork practices, evening social events, checking

surveys, mapping exercises, and data entry. Next, I draw specifically on my participant obser-

vation when ‘‘fieldwork’’ was being undertaken.

SOCIAL DEMOGRAPHY AND FIELDWORK

The two projects discussed here are best described as demographic projects. Beginning in the

1940s, demography’s major concerns have been with fertility and population growth. These

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 349

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

interests shifted to encompass migration, marriage, and social mobility in the 1950s. More

recently, demographers have taken primary interest in health, particularly global health, and

in this context, there are increasing numbers of demographic survey projects on AIDS in

sub-Saharan Africa. While pre-1960s demographic research relied on aggregate data from vital

registration systems, postwar concerns with population growth and the advent of the computer

shifted demographers’ object of study from aggregate data to individual-level data collected

through ‘‘question and answer’’ surveys in developing world contexts (Cleland 1996). Many

suggest that postwar demography has become increasingly ‘‘social’’ and moved toward identi-

fication with the social sciences and to use mixed methods (Caldwell 1996:309).

Administering individual-level surveys in rural Africa necessitates that demography move out

of the office and into villages. Like anthropologists, demographers term this period away from

the office or home ‘‘fieldwork’’ and refer to sample villages as ‘‘the field.’’ Principal investiga-tors, Malawian collaborators, and Malawian research assistants viewed the field as a place both

distant from and incommensurable with their own positionality. During everyday data collection,

the field and office became signifiers taken up and absorbed into subjectivities, social relations,

and practices. Through everyday linguistic and performative place-making practices (Gupta and

Ferguson 1992, 1997)—ways in which culture, power, and place intertwine and are assumed by

categories of person—research project members reproduced the spatial and temporal autonomy

of the field and office.

Researchers, for example, often discussed the challenges of preparing to travel to a place

(even for a few days) that was foreign and mostly unknown to them, and spoke about ‘‘beingaway from number-crunching [in the office]’’ (personal communication, American demo-

grapher). Malawian interviewers and supervisors charged with collecting data in the field,

too, distanced themselves from the villagers and sites of fieldwork. At one project’s training

for Malawian fieldworkers I attended in May 2008, a Malawian supervisor advised the new pro-

ject employees regarding proper comportment, behavior, and dress codes ‘‘in the villages’’:

How do we dress for the field? We put on a chitenje [colorful, wrappable fabric worn by women].

We can’t wear what we wear in the city; you have to suit the environment. . . . Strong perfume can

make the respondent [research participant] uncomfortable and you can’t be wearing those jeans that

have 50 CENT [the rapper] written on them or that Kangol hat [pointing to trainee].

Learning to be a good fieldworker and to see like a research project means learning to distance

oneself from the field through a certain ‘‘performative competence’’ (Ferguson 1999): ‘‘Culturalstyle implies a capability to deploy signs in a way that positions the actor in relation to social

categories’’ (96). The guidelines for dress and behavior were taken up in the field. As we drew

nearer to sample villages in project vans at the start of fieldwork each day, the women in the van

tied headscarves or bandanas around their heads and knotted chitenje fabric around their waists.

At the end of the day, the women sighed with relief, unwrapped their heads, and took off their

now dusty zitenje (plural form of chitenje) as the vans sped back to the office. In the remainder

of this article, I use the terms ‘‘field’’ and ‘‘fieldwork’’ in my informants’ sense—field to describe

the geographic sites (sample villages) from which survey data are collected, and fieldwork to

refer to the everyday work of finding and interviewing Malawians in project samples.

The projects described here fit into the larger apparatus of global health (Koplan et al. 2009).

First, in their focus on the AIDS epidemic, they center their inquiries on a pressing health issue

350 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

that transcends national boundaries. The statistical and other data these projects collect are useful

to government and other actors who stage population-level prevention efforts and may also

inform clinical care of individuals. Researchers were driven not only by academic ambitions

but also by genuine interest in reducing health inequalities and mitigating the pernicious effects

of HIV on local kin networks, livelihoods, and mortality. Yet, some suggest that the continent’s

latest export is information for university-based and other researchers (Janes and Corbett

2009:176). Because AIDS research plays out on terrain marked by inequality, some argue that

research—even if not obviously economic—nonetheless functions as global exploitation

(Riedmann 1993; Petryna 2009).

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT

Since the colonial era, Africa has occupied a place in global geography as a ‘‘living laboratory’’for various improvement projects on health, hygiene, agricultural practices, and education

(Vaughan 1991; Schumaker 2001; Tilley 2011), and research in Africa has long been entwined

with or in the service of imperial, national, and international governing projects. Such projects

depend fundamentally on enumerative techniques that produce statistics to accurately represent

social realities, whether in the form of average acres of farm land planted with tobacco or the

prevalence of TB or AIDS in a population of interest. These numbers convert or transform

real-time snapshots of social reality captured through surveys, rapid HIV tests, or other technol-

ogies of measurement into accessible numerical knowledge that frames interventions or policies

to improve social problems.

In Seeing Like a State, Scott (1998) uses the invention of scientific forestry in the late eight-

eenth century as a metaphor for forms of knowledge and manipulation characteristic of powerful

institutions with narrowly defined interests. The eighteenth century state, in its sole interest in a

single number—the annual revenue yield of timber—‘‘missed’’ or was blind to flora and fauna

holding no potential for state revenue or holding a certain ‘‘use value’’ not convertible to fiscal

receipts (Scott 1998:11–12). In its application of management techniques such as clearing under-

brush, planting trees in neat rows, and mapping, the state created a sort of forest laboratory that

was easily manipulated experimentally and understandable from a centralized office location.

The ability of a state to govern, optimize, and manage its natural or human resources relies

on ‘‘seeing’’; this optic practice, for Scott, centers on the analytics of legibility, simplification,

and magnification.

As the natural world is too unwieldy in its ‘‘raw’’ form for administrative manipulation, so too

the social patterns of human interactions that may be of interest to the state are ‘‘bureaucraticallyindigestible’’ in raw form (Scott 1998:22). The modern state’s interest lies in optimizing the pro-

ductivity of human and natural resources, motivating interventions into health, reproduction,

sanitation, education, and farming (Scott 1998:52). These endeavors to improve the human con-

dition depend on bracketing contingency and standardizing their subjects, and they utilize what

Scott calls the ‘‘instruments of statecraft:’’ censuses, maps, identification cards, statistical

bureaus, schools, and mass media (343). These tools collect and organize information in the

forms of tables, maps, and other measurements that enable the state to ‘‘see’’ its population

and the slice of social reality of interest (mortality rates, geographic distribution of population,

and so on).

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 351

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

Today, the state is one among many actors or systems of organization in Africa and globally.

Territories and populations are socially and spatially regulated—‘‘seen’’—in new ways by

diverse, multiply interested actors and institutions. James Ferguson (2005), in his critique of

Scott’s preoccupation with the homogenizing logics that characterize the state, highlights the

importance of recent shifts that have reconfigured national terrains: globalization, international

civil society, transnational moral accountability, global health, and human rights regimes are

especially important forces in considering the terrain of Africa. The research projects described

here operate simultaneously in collaboration with and outside the Malawian state; their logics,

objectives, and infrastructures are situated within and also exceed national borders.

Much as legibility, simplification, and magnification are necessary to the state’s ability to see

its subjects, so too they are cornerstones of the research project’s ability to see and accurately

represent its subjects. Next, I take interest in the power of technical tools—in this case, maps,

HIV tests, surveys, and so on—both to note social facts and to transform them into data. I illus-

trate that even as research projects have the capacity to transform social reality into information,

research participants enmeshed in this social reality act to modify, subvert, block, and overturn

research tools and techniques and the categories they impose on research subjects. Finally, I

reflect on Scott’s emphasis on homogeneity, uniformity, and standardization, and the usefulness

of this approach in considering the rules and scripts that govern the collection of data by research

projects during fieldwork. Together, these elements—legibility, the tools of transformation, and

standardization—are central to the ability of researchers to collect high-quality data that aspires

to accurately represent social realities in Malawi. For these reasons, I suggest that seeing like a

research project entails similar preoccupations and gestures to ‘‘seeing like a state.’’

MAKING HIGH-QUALITY DATA IN THE FIELD

Underlying the ability of research projects to see the AIDS epidemic and to measure its effects

on a population is the transformation of complexity into simplicity. Stories become marks in a

survey box, people become data points, and households become dots on a map. The transform-

ation of information collected from individuals during survey fieldwork into numerical data, of

course, implicates sites outside the field—the office, databases, and policy or research confer-

ences, for example (Biruk 2011). In this essay, however, I am most interested in how everyday

fieldwork practices—the interactions between interviewers and research participants, mapping of

rural field sites, moral economies of exchange as they manifest in the day-to-day of research

fieldwork, and the standardized implementation of tools of enumeration or measurement—anticipate the criteria by which statistical claims about rural Malawi will be deemed authoritative

or not. How does the definition of high-quality data shared by social demographic researchers

manifest in the behaviors, practices, and interactions of the various actors that comprise the lar-

ger research project? How might these standards intersect with the messiness of fieldwork and

come to bear on numbers themselves? I suggest that numbers are not merely recorded onto

survey pages and copied into databases; rather, they are produced and negotiated within social

encounters and exchanges.

While standards of high-quality data are shared and reproduced by the epistemologies and

investments of an epistemic community of social demographers, the demographers are not direct

participants in everyday survey research fieldwork. Fieldwork primarily implicates Malawian

352 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

research assistants and rural Malawian research participants, and so collecting high-quality data

necessarily entails reproducing standards and expectations through the inculcation of habits and

scripts performed by both research assistants and research participants. Thus, seeing like a

research project (and not just a researcher) necessitates standardization of habits, scripts, prac-

tices, and social interactions across thousands of social encounters in the field.

In charting the emergence of objectivity in scientific communities in the mid-nineteenth cen-

tury sciences, Daston and Galison (2007) ask how norms of knowledge production connect with

on-the-ground scientific conduct (27). They suggest that these norms are epistemic virtues: ways

of seeing and representing the world that are internalized and enforced by appeal to shared ethi-

cal values. Instead of presuming objectivity to be an abstract, timeless, and monolithic concept,

they suggest that ‘‘scientific objectivity resolves into the gestures, techniques, habits, and tem-

perament ingrained by training and daily repetition’’ (52). Objectivity is an amalgam of situated

practices that seek to minimize errors that lead to a false representation of nature. Similarly,

demographers’ shared expectations around high-quality data anticipate and take precautions

against errors—especially during data collection and fieldwork—that might produce inaccurate

numerical representations of Malawian social practices and realities. This imperative resolves

into a set of epistemic virtues that guide everyday data collection: precision, accuracy, timeli-

ness, sample size and sample purity, reduction of human error, and clean data. In what follows,

I explore how these main epistemic virtues standardize the collection of numerical data and

manifest in specific forms of social exchange, practice, and relationships in the field.

ENSURING ACCURACY AND PRECISION

Data must be accurate and precise if it is to serve as evidence for knowledge claims that can

become the foundation of AIDS policy. Accuracy dictates that data must be as true a represen-

tation of reality, of an individual, or a phenomenon as possible. Precision mandates that data and

findings resulting from it must be replicable—obtainable in the same form again and again. To

ensure replicability in the future—in demographic parlance, over longitudinal time—research

projects must ensure that fieldwork teams collect numbers in standardized manners. Next, I illus-

trate how survey questions are designed and how questions are ‘‘translated’’ to ensure that they

elicit the most accurate responses.

Translating the Survey

In addition to concerning themselves with the challenges of translating a survey from English

into local languages (Chichewa, Yao, Tumbuka), demographers were also preoccupied with

issues of cultural translation. If a respondent does not truly understand a given question or what

it seeks to capture, his or her response is not valid and becomes ‘‘bad’’ data. Projects attempted

to increase local understanding of potentially difficult survey questions by utilizing exercises to

translate complicated concepts into simplified forms. To ensure clarity of meaning and trans-

lation of intent in relation to probability, for instance, one project implemented what became

known as nyembanyemba (the beans) among research staff and research participants.

Nyembanyemba aimed to make the concept of probability accessible and understandable to rural

Malawians,2 by asking respondents to place a certain number of beans in a dish to estimate how

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 353

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

likely it was that they would, for instance, go to the market in the next two weeks, experience s

food shortage, or contract HIV=AIDS (one bean if it was unlikely to happen, ten beans if it was

certain to happen; see Figure 1). Although these numerically grounded elicitation methods had

been tested and verified in academic journals and at international conferences, the villagers’

responses to the exercise were, on the whole, negative. One female research participant in

2008 summed up the generalized discomfort with the beans exercise: ‘‘If you want to play,

go over there with the children!’’ Research participants tended to view this exercise as infantiliz-

ing. How did this tool meant to increase the accuracy of data collected from research participants

translate into the field? I provide an ethnographic vignette to highlight the negotiation involved

in nyembanyemba.

Over the course of a few weeks during fieldwork, the beans were an important topic of

negotiation between actors who occupied different levels of the research project. Fieldwork

supervisors,3 in their role as employees to the project and managers of the interviewers who were

implementing the exercise, had to negotiate carefully a small space between the researchers’

mandating of the exercise, their own views about the beans, and the incessant complaints from

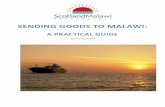

FIGURE 1 Sample questions from the ‘‘Beans’’ (expectations) section of the 2008 survey implemented by a case study

project. Questions appear in Chichewa (bold) and English (italics).

354 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

fieldworkers that the beans exercise was too time-consuming. On a daily basis, fieldworkers

opined that the beans were a waste of time and silly and that respondents grew bored and did

not understand nyembanyemba. In general, supervisors told their charges to stop complaining

and encouraged them to ‘‘improve your attitudes—the bad morale among your villagers

[research participants] is coming from you! They can tell you think nyembanyemba is chabe[worthless] and this allows them to protest.’’ However, at the nightly meetings with US research-

ers, the supervisors in turn suggested to the Americans that the beans exercise was a misfit with

‘‘Malawian culture’’—it was difficult for Malawians to understand. Statements such as this point

to the irony of a ‘‘culturally relevant’’ tool for measuring probability being classified as

‘‘outside’’ or irrelevant from a vantage point within a culture.4

My field notes written about interviews where nyembanyemba was implemented highlight

the everyday sorts of negotiations that took place. In June 2008, Tapika (all names are pseudo-

nyms), a 24-year-old woman, was interviewing a 35-year-old man in a village in central Malawi.

The pair sat behind the respondent’s house on a mat he had set out on the ground, and the

survey–interview proceeded smoothly until they arrived at the beans exercise. Although he

was at first reluctant to engage in this section of the survey (‘‘I really should do this? [move

the beans around] Can’t I just answer the questions?’’), he quickly became a willing participant.

After Tapika provided him with instructions, he eagerly proclaimed: ‘‘So, if you ask me how

likely it is that it will rain today, I should say, maybe two beans, because look [pointing to

the clear sky], it’s just not!’’ I read this energetic enthusiasm as a performance of his knowledge

of probability and his ability to clearly grasp the instructions (partially influenced by my pres-

ence). Halfway through the long section, however, he grew tired of the beans and started to

respond by mentioning numbers without manipulating the beans and the dish in front of him.

At this point, Tapika grew frustrated, and she proceeded to physically pick up the number of

beans the respondent said each time, and place them into the dish—as if to say: Look, you have

to continue to do this. Her counterpart grew increasingly annoyed, and the defeated Tapika

finished the section without requiring him to use the beans.

The interview encounter and the numerical data collected are therefore sites of negotiation,

where numbers recorded on a survey page are hardly the only determiner of what or who

‘‘counts.’’ In this example, the respondent made known his own reasonableness by making an

effort to follow instructions and go along with something he initially found unappealing. His

later disinterest in the exercise marked his effort to disengage from a dynamic where the inter-

viewer asserted her status by requiring him to ‘‘play’’ with the beans. Tapika, as a young woman

interviewing an older and traditional village man, had to negotiate this relationship carefully, and

I believe she also felt compelled to perform the scripts of the beans that she had learned in train-

ing. In this case, Tapika’s desire to be identified as a ‘‘good fieldworker’’ trying to convince a

‘‘difficult research subject’’ to participate in the beans exercise illustrates her absorption of the

project’s preoccupation with collecting accurate and precise data.

As an internationally validated tool for collecting information about probabilities from devel-

oping world respondents, nyembanyemba’s translational function promised to make an abstract

concept lucid and accessible to respondents who must understand it in order to answer questions

accurately. Exercises such as this permit respondents to externalize their thoughts and thus allow

research assistants to determine whether their respondent comprehends the question. However,

as this section has shown, the bean exercise and its associated tactile aspects made it difficult for

research assistants to implement nyembanyemba precisely across different interview encounters.

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 355

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

Whereas monitoring handwriting or pointing out empty spaces on a survey page is easy,

determining whether each interviewer implements the beans exercise in the same way every time

or gauging the divergent levels of fatigue and frustration likely to be manifested across respondents

is close to impossible. Regardless, as a culturally relevant, internationally accepted, and scientifi-

cally validated translational tool, the beans convincingly perform enhanced accuracy and precision

in data collection. The number of beans captured on a survey page by the interviewer is an effective

proxy for complicated social realities and covers over the social aspects inherent in the production

of these numbers that serve as the foundation for numerical claims about the epidemic.

TIMELINESS AND TIMELY DATA

International AIDS research projects and the larger global health system rely on the rapid circu-

lation of data and its representations so that actors may effectively intervene into a pressing

health crisis. However, the imperative of the research project to ‘‘keep time’’ often comes into

friction with other interlocking temporalities: village time, weather delays, the erratic and uneven

temporal projects of fieldworkers themselves, and even the time and schedules of other projects

working in the same village(s). Nonetheless, the imperative to collect data, not only of high qual-

ity but also timely, serves to standardize everyday fieldwork practices. In this section, I illustrate

how these standards translate into the fieldwork context, and how interviewers negotiate these

standards as they stand at temporal crossroads. I show how an interview encounter is a site

of multiple interests that are negotiated as a survey–interview flows forward, making numbers

collected during the interview social artifacts.

In July 2008, I accompanied Janet, a 26-year-old female interviewer, to her meeting with a

39-year-old woman called Namoyo. When we arrived, Namoyo and her mother were shelling

maize. Before getting down to business, the four of us sat quietly together, each working at

the maize. At first the potential interviewee was put off by the prospect of a long interview,

but as the conversation progressed, she grew more open to the idea. When Janet mentioned that

she was from a nearby village, the woman grew excited: ‘‘How nice! I’m so glad you’re working

for them [the research project]; usually the people who come to chat with us are from Lilongwe

and Blantyre [the administrative capital and commercial capital, respectively].’’ Maintaining our

place on the verandah and continuing to shell maize as a group, we began the questionnaire.

Every so often, children, goats, and chickens darted across a walking path nearby, briefly

disrupting the flow of the survey questions.

Janet introduced the survey as an informal ‘‘chat’’ ‘‘Naphiri [the author’s Chewa name] and I

are just here to have a chat with you! We will just chat . . . let’s chat!’’ In both English and

Chichewa (kucheza), ‘‘to chat’’ implies to speak in an informal, nonlinear, undirected and non-

temporally bounded manner—to free form a conversation. But as soon as Janet brought out the

survey and her pen, it became evident that this chat would follow the order of the questions

written on the survey pages. The first portion of the chat involved Namoyo verbally filling in

the household roster. This was on the first page of the survey, and comprised a table with fifteen

columns and ten rows. After asking Namoyo to list each member of her family who live in her

household, Janet wrote the names one by one into the blank rows. Once all the names were

recorded on the sheet, she asked a series of questions about each household member: ‘‘Howold is X? What is X’s relationship to you? Is X’s mother alive? In what year did X move here?

356 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

What is the highest level of schooling X went to? Is X married? Is X ill?’’ Many of the answers

provided by Namoyo had to be ‘‘coded’’ by Janet with a relevant number (for level of schooling,

Standard 1:0; Standard 2:1; Standard 3:2). In cases where she did not recall the codes, this invol-

ved Janet pausing while she leafed through an accessory packet of survey codes in order to

locate the proper code to be supplied.

A month earlier, Janet had attended a training in which project interviewers had been taught

to maintain good penmanship and be careful and consistent in filling out project surveys. As

Namoyo delivered her responses to the survey questions, Janet took care to record the responses

neatly; she even used a ruler as a straight line beneath the letters she wrote. Her efforts to adhere

to the rules governing interviewing meant that it took Janet a significant amount of time to rec-

ord the information. The chat was marked by long periods of silence and awkwardness as Janet

monitored her own penmanship to ensure she was seen as a good interviewer, not only by me but

by the researchers and data entry clerks who would see the survey later. Despite the ‘‘roadmap’’provided by the survey from beginning to end, the chats were certainly not linear—in this

instance, Namoyo could not recall the names of her parents-in-law when initially asked by Janet;

later, during another section of the survey, she suddenly recalled them, interrupting the flow of

the interview session and prompting Janet to flip back a few pages to enter the information. Like

the rhythmic shelling of maize, the survey’s chronology served as a mere backdrop against

which the interaction meandered.

The interview encounter was a negotiated space of flows and stoppages of information, a

social field in and of itself. As in many cases, the interview between Janet and Namoyo was

marked by the interlocutors’ mutual testing the waters. Early on, Namoyo commonly responded

to questions with an ‘‘I don’t know’’ or other simple answer. When Janet asked her about the

amount of money she loaned to others in the past year, she claimed: ‘‘none.’’ Janet looked at

her dubiously, laughed, and asked ‘‘Not even five kwacha [about US $0.04 at the time]?’’ Thewoman laughed, and then agreed that she had, indeed, loaned friends, neighbors, and family

members money in the past year. Later, Janet had to return to this box on the survey again when

it turned out that Namoyo could remember the amounts she donated to individuals she listed by

name. Similarly, Namoyo claimed she could not remember the ages of her own children.5 When

Janet pressed her, she could. Finally, over the course of a series of questions that covered wealth

indices, Namoyo grew frustrated and visibly annoyed at having to provide verbal responses to

questions that she felt were self-evident to Janet. As a good interviewer who had been taught

never to miss a question, Janet meticulously enunciated each question: Does your household

own: a TV? Solar panels? Does your household have a metal roof? Namoyo laughed in the face

of questions such as these: Janet could easily see that she possessed none of these items—she was

poor! Yet, when Namoyo laughed, Janet still pressed her to verbalize her actual response: ‘‘No.’’Like Namoyo, many respondents were ambivalent about the interview encounter. Often, this

aligned with the interviewers’ own ambivalence (May 2008). Janet’s affect in response

to Namoyo’s sighs of frustration showed that these questions were not her own; she was the

mouthpiece for the project. Namoyo, picking up on her disinterest in this matter, made repeated

stabs at taking control of the interview encounter by being selective about which questions she

answered, by providing inconclusive or vague responses, or by feigning nonknowledge before

finding an answer. These efforts tested the contours of the interview as a social space: How

invested was Janet in securing answers to each of the questions? How much could Namoyo

reveal? Was Janet able to detect when Namoyo provided ‘‘bad’’ information? Namoyo relished

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 357

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

the chance to talk to Janet and me; as outsiders, we were an invaluable source of information.

Namoyo asked us how things were in other districts to which we had traveled, whether we had

any children, and so on. Again, the linear form of the survey was disrupted and made to meander

when it was inserted into the social relations and space of the interview encounter. The standards

and guidelines for collection of ‘‘good numbers’’ that interviewers learned in training sessions

became embodied during the interview session. The imperative to write neatly and to be meticu-

lous appeared in the field as awkward silences, with goats bleating in the background and infor-

mal conversation filling the gaps. The mandate to ‘‘ask every question’’ became the site of a

negotiation, with both interviewer and interviewee trying to gain a foothold to express and

secure her interests. The command to leave no blanks on the survey prompted push and pull

exchanges between Janet and Namoyo, with the former probing for information and the latter

recalcitrant about providing it. The chronological time presumed by the numbered pages of a

survey and the project’s emphasis on efficiency and timeliness were enacted by Janet’s meticu-

lous administration of the survey, but came into friction with both her desire to be a good inter-

viewer (which often involved slowing down to record data well) and her circuitous and slow

time encounter with Namoyo.

SAMPLE SIZE AND SAMPLE PURITY

Next, I consider how numbers are made by focusing on how demographers’ concerns with sam-

ple size and sample purity structure and inform the everyday processes of sampling. How do

field teams ensure that as many sample respondents as possible are reached and ‘‘counted’’?How do projects ensure that the correct respondents are interviewed, and how is the sample’s

purity protected?

Sampling as ‘‘Seeing’’

Sampling is one enumerative technology that effectively and efficiently decontextualizes data

from its immediate context. It is invariably done in the office, usually when the research proposal

is written and well before any fieldwork occurs (and sometimes before foreign members of the

research team have set foot in Malawi). Samples are efficient: it takes far less time and money to

interview 5000 Malawians than 15 million Malawians. But for the few to represent the many, the

sample must be carefully selected (typically, randomly), and close to everyone in the sample

must be interviewed. Only then will it be considered authoritative in the social science research

community, only then can the results of the analysis of data be deemed representative of the

larger population. The projects described here employed random sampling, with their samples

drawn from populations smaller than the nation but larger than a village: usually sample house-

holds were located within administrative areas or geographic blocks of space identified as enu-

meration areas (EAs) by the National Census, facilitating the uptake of project data by national

development agendas.

Beyond bounding a sample from a larger population in the office, maintaining sample

purity and size implies many maneuvers by the fieldwork teams during data collection. These

maneuvers are unscripted, always evolving, and responsive to contextual and unpredictable

conditions—both environmental and social. Sample purity necessitates quarantining sampled

358 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

individuals and creating defenses against infiltration of the sample by nonsampled individuals,

delays in reaching all the sampled individuals, and respondents’ refusals to be interviewed. The

fieldwork teams often had to fill in gaps with ‘‘leg work,’’ adaptations, or real-time modifica-

tions. Working on a longitudinal project implies two things: (1) interviewers and supervisors

are likely to be retained from year to year; and (2) these fieldworkers interview the same respon-

dents from year to year. In this way, although demographic field research comprises ephemeral

and short-lived intimacies between strangers (interviewer and interviewee), these are intimacies

constructed from the stuff of historical and anticipated encounters. These intimacies that stretch

across field seasons necessitate that certain strategies be employed to ensure that good relation-

ships are maintained and reproduced between not only the project and the community but also

between the interviewer and his or her subjects (and potential future subjects). How does the

project-level mandate to treat ‘‘the sample’’ (people) with respect manifest in the everyday inter-

actions between fieldworkers and villagers? Moreover, how do these interactions serve to

enhance or erode sample purity?

For demographic research, a pure sample refers to a sample in which as many of the listed

respondents are surveyed and=or HIV-tested as possible. It also means that measures must be

taken to prevent project staff members from interviewing the wrong people and to discourage

respondents from refusing to be interviewed or hiding from interviewers. The official project-

sanctioned tools for this purpose comprised photographs of respondents to verify identity, hand

drawn maps that direct an interviewer to his assigned household, and some limited identifying

data collected from the respondent in past years. However, fieldworkers soon developed more

effective tactics for preserving sample purity. These were: establishing social, business, or lei-

sure relationships with those in the sample; repaying villagers promptly for property broken

or affected during fieldwork; and drawing their own maps (with the help of local people) when

the official one failed or was invalidated by environmental conditions or terrain.

In order to maintain sample purity and to collect good data, a research project must maintain

good relations with the community. In addition to being transparent and clear about research pro-

tocols and logistics (how long a project will be in the area, what information the project needs,

how the information will be used) and going through the proper channels before speaking to

respondents (a project first presents itself to the district office and police station and, from there,

to Traditional Authorities [TAs], chiefs, and sub-TAs), projects also maintain good community

relations through more mundane practices. Research teams view the field not as a social context

frozen in present time and space but as an always evolving and dynamic place whose contours

stretch across time. Actions in the present are geared toward preserving and reproducing positive

relations between the project and the community. While the researchers perhaps have the great-

est interest in maintaining these good relations, the research assistants, as current and future

employees of research projects who return again and again to the same locales, also have a

vested interest in ensuring that their future work will be as easy and painless as possible.

One rainy day during fieldwork, a project Landrover was slowed down by grasses as tall as

humans. The vehicle swam through the reedy green impediments like a barge caught in mud,

often getting mired in wet ground hidden beneath the grasses. The day was frustrating and mor-

ale was low; the absence of the road that was apparent during the dry season made the work of

finding the sample households close to impossible. Suddenly, the SUV struck something hard.

Out of nowhere, a young man emerged, yelling that we had run over his family’s clay pot filled

with the day’s relish (ndiwo).6 The supervisors got out of the car, apologizing to the man. He

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 359

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

accepted the apology but suggested that the project owed him compensation for the breakage.

After a few minutes of whispering among themselves, one supervisor went to the man and

offered him 600 kwacha (about US $3.50 at the time). The man received it graciously. The

supervisor later explained the story to the researchers and was compensated for using his own

money to cover the costs of the broken pot.

This incident indicates how project staff—external to formalized codes for ‘‘respecting the

sample’’—protect good relations between themselves and their research subjects and, in the pro-

cess, ensure sample purity. Later that evening, the supervisors suggested the gesture was one of

good faith; the exchange of money for the broken pot performed and reinforced the project’s

commitment to fair and positive relations with its subjects and its adherence to the dictum

‘‘do no harm.’’ Giving the money, they said, ensured that this man would not go back to his

household and village with bad feelings for the project that could influence whether he or his

family and friends welcomed the project in the future or participated in the survey. A simple

and seemingly minor good faith exchange (the broken pot was technically nobody’s fault), in

this instance, served an important role in ensuring future sample purity and retention. Further,

this exchange provided an instructional model for the other research assistants who witnessed it.

In order to preserve sample purity, research project employees must also be able to identify

and isolate sample respondents of interest from the background and ‘‘noise’’ of environmental

and social complexity. In other words, research assistants must interview the right people. Maps

were an important tool that served to make complex and unknown social and geographic terrains

in the field more manageable and visible. Maps, however, were not stable and permanent texts,

but rather, dynamic works-in-progress. When teams first arrived in a district (especially if they

had not previously worked there), they headed to the NSO or district office in order to collect

recent maps of the human and physical landscape that would be their home for the next few

months. However, the maps did not always tell all; although they determined physical impedi-

ments that might block the project from accessing certain districts (such as rivers, mountains, or

the lack of a tarmacked road), mapping a potential fieldwork area necessitated local knowledge

of the social terrain.

Case study projects created maps that were accumulative condensations of archived project–

knowledge. These maps were hand drawn on sheets of paper and part of the toolkit of objects

carried by each interviewer. At the top of each was a blank space where the household number

could be listed (household numbers were often chalked on to the top of the house in question)

and a box for comments to be written by the interviewers. These comment boxes contained

handwritten information meant to direct future interviewers to the household. For example:

‘‘The household is behind a small thicket of trees just off the dirt path running behind the train-

ing center. It is a sundried mud hut and there is a waterhole out back.’’ In addition to these

instructions, the maps contained pictorial and symbolic representations to help show the way:

miniature trees, churches, kiosks, vegetable stands, rivers, roads, and paths marked with arrows

pointing in the right direction. Of course, project maps were necessarily imperfect and perpetu-

ally inaccurate—from one year to the next, a vegetable seller may relocate or a tree may be felled

by lightning or human hands or a water hole may run dry. In this way, each crop of interviewers

was instructed to correct or improve the maps as needed. Using a pen or pencil, they drew over,

crossed out, and refined the maps.

These maps were invaluable tools in locating sample households, especially remote or far-off

homes. However, once interviewers arrived at a household, there were still unknowns. In some

360 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

cases, families had moved away to an unknown location, leaving the house empty or filled with

a new family. Even those households that retain their original inhabitants can be ‘‘mis-read.’’The maps that help interviewers find sample households are complemented by photos meant

to enable the research assistants to determine with certainty the identity of an assigned respon-

dent. Increasingly, each respondent in the sample is photographed with a digital camera.7 The

photo is then printed out in the field office (usually in color) and attached to the clipboard of

the interviewer assigned to visit that particular respondent that day. Yet, this did not solve the

problem of names. After all, relatives who wished to pretend to be someone else (in order to

receive the gift of soap given by projects to participants, for instance) could meet the two main

criteria for identification, even if they were not the respondent: they both resembled and pos-

sessed the same surname as the respondent. Thus, adhering to the epistemic virtues of sufficient

sample size and sample purity involves not only the enumerative tools provided by projects but

also tactical efforts on the part of research assistants in everyday practice—creating ‘‘living’’maps of households, ensuring good relations between project and participants, and identifying

‘‘fake’’ respondents.

MANAGING UNCERTAINY

The mechanisms of seeing rely on capturing slices of rural Malawian society and their trans-

formation into numbers. I have shown that these processes are highly standardized and forma-

lized in their aspiration to align with major epistemic virtues shared by social demographers,

who are concerned with collecting and circulating high-quality data. Expectations of ‘‘good’’numbers produced by demographic survey researchers cultivate new roles, forge new social rela-

tionships, engender negotiation, and influence everyday practices, habits, and interactions. Yet,

even as these virtues permit seeing, they also create blind spots. Each of the epistemic virtues I

have described in this article has an underbelly; seeing is also not-seeing. I have not pointed out

the shortcomings of knowledge produced by research projects but rather elaborated how

epistemological commitments and values both enable and constrain the transformation of rural

Malawian society into numbers. How is uncertainty simultaneously acknowledged and effec-

tively managed by producers and consumers of AIDS knowledge?

Seeing and the Self

Managing uncertainty entails managing the people and processes that produce high-quality data.

Just as the scientific seeing cultures described by Daston and Galison (2007) internalize and

enforce these virtues by appeal to ethical values (40), social demographers adhere to a unique

set of epistemic virtues that serve as a measuring stick for evidence and knowledge claims made

by members of this knowledge community. High-quality data are accessible only through replic-

able collection methods, through standardized guidelines that seek to tame the potentially unruly

or unscripted practices of research assistants, through ‘‘large enough’’ sample sizes, and through

highly scheduled and time-sensitive everyday fieldwork plans. Each of these helps to ensure the

power, statistical significance, ethical collection, and certainty of knowledge about AIDS not by

autonomous individuals, but by the variety of actors and practices that comprise the research

project as a particular ‘‘knowledge space’’ (Turnbull 2000:4).

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 361

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

A corpus of gestures, techniques, habits, and temperaments ingrained by training and daily

repetition and adopted by researchers and their employees are a precondition for the production

of knowledge. They enable the research project to operate smoothly and to see the parts of social

reality that count, while disregarding those that are not; they give numbers the appearance of

certainty and coherence. Numbers and selves—even as governed by standards of production

and extensive trainings—are always in flux, mutually constitutive and dynamic against a

backdrop of social reality and relations.

Provisional, ‘‘Good Enough’’ Numbers

What falls out of sight of research projects? In discussing what he considers as a paradigm of the

government of living beings and an archaeological form of biopolitics—pastoral power—Foucault (1978=2007) suggests that the shepherd is in charge not of individuals but of a herd

(25–136). This pastoral orientation to the herd is characteristic also of the researcher’s orien-

tation to the sample. As I have illustrated, the project’s main priority and concern—in the field

and in the office—is with the sample. Although the project on some level ‘‘knows’’ each of its

individual subjects (via the face-to-face interview encounters between research assistants and

participants), much as Foucault suggests the pastor or the shepherd know the individual mem-

bers of his flock of souls or sheep, its imperative is the transformation of each of these encoun-

ters into data. Individuals and context fall out of sight as the sample becomes visible, just as

Scott’s (1998) modern state loses sight of the trees in seeing the forest (46–47).

While critiques of AIDS policy and research in sub-Saharan Africa presume that researchers

are overlooking something or that research practices are inadequate, I argue that researchers do

not miss anything; they see exactly what they intend to see and their data make stability and

fixity in representation possible (Lampland 2010). Even as they employ methods, objects, and

techniques that serve as a lens into and a receptacle for the ‘‘social,’’ the researchers’ gaze is

trained on that portion of reality bounded by shared epistemic virtues. More importantly, AIDS

research already focuses its gaze on AIDS, developing tools that seek to capture a specific aspect

of reality—of people and places who are infected with or affected by HIV.

AIDS research is often taken as uncritically good and the investment in its forms or products

often distracts attention from the processes that produce the forms. The practices I have dis-

cussed here—survey design and translation, sampling, a questionnaire with short answers for

huge questions or large aspects of life, mapping and photographing households in the sample,

and imagining the field and office as different—serve to transform people into numbers, house-

holds into dots on a map, and voices into disembodied data. Even as they produce blind spots,

they cover them over by framing them as outside the scope of research’s interests. Uncertainties

and everyday social interactions and practices stand behind and are obscured by numerical

claims about the epidemic. We might consider these numbers as provisional; the uncertainties

they contain are accepted, first, because numbers are instrumental tools and, second, because

their provisional status is always already acknowledged by those who produce them (Lampland

2010).

Central to this transformation of information into data is the office’s position outside the

space and time of the field and its imagination as a neutral, sanitized space; elsewhere I suggest

that a certain anachronism (Fabian 1983) between the field and the office is reproduced through

362 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

discourse that foregrounds temporal incongruities between these sites—the quick time of the

office and slow time of the villages, and so on (Biruk 2011). Michael Lynch (1988) discusses

a similar transformation when he shows how lab practices reduce an animal into an ‘‘abstractedversion of a laboratory rat—a set of contingent material and literary products of laboratory

work’’ (272). Lynch elaborates to show that the laboratory rat is a cultural object ‘‘held steady

by a community of practitioners’’ (279) as it is ‘‘rendered’’ through mechanized and mechanical

actions into data. I have shown that international AIDS survey research relies on similar trans-

formations and that numbers are social artifacts that are ‘‘held steady’’ by shared epistemic vir-

tues. Numbers that depict the scope of the AIDS epidemic in Malawi are not simply data

collected from research participants; rather, they are the provisional products of negotiations

within and across thousands of social encounters in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deepest gratitude to the researchers who allowed me to participate in their fieldwork adven-

tures; to the field teams who permitted me to follow along in the field; to those in the ministry of

health, NGOs, CBOs, and National AIDS Commission who answered my questions; and to the

villagers in Zomba, Mchinji, Salima, and Blantyre who indulged my conversations. Grateful

thanks to my wonderful research assistants and key informants Andy and Enalla Mguntha,

Augustine Harawa, Evans Mwanyatimu, Sydney Lungu, Joel Phiri, and Tasneem (Thoko) Ninje

(and many others); and to the Centre for Social Research and Chancellor College of the Univer-

sity of Malawi (especially Alister Munthali and Pierson Ntata). I thank Susan Watkins, Sandra

Barnes, Michelle Poulin, Adriana Petryna, Teri Lindgren, Fran Barg, Marian Burchardt, and my

colleagues in this special issue for comments on earlier versions. Financial support for research

and writing came from Social Science Research Council (SSRC), Wenner-Gren Foundation for

Anthropological Research, National Science Foundation (NSF), School for Advanced Research

(SAR), and University of Pennsylvania.

NOTES

1. When AIDS first arrived in Malawi, many considered its symptoms manifestations of tsempho or kanyera, exist-

ing sexual diseases caused by transgression of boundaries or breaking of taboos. Other initial names for the disease

included magawagawa (that which is shared), chiwerewere (promiscuity), kachilombo koyambitsa a matenda a edzi(a small beast that brings AIDS), or, simply, kachilombo (the small beast; Moto 2004; Lwanda 2005; author’s field notes;

2007–2008).

2. In developing world settings especially, it is felt that simply asking respondents for a probability or percent chance

is too abstract, and that visual aids are needed to help them express probabilistic concepts. This commonly involves

asking respondents to allocate stones, balls, beans, or sticks into a number of bins. See Delavande and colleagues

(2010) for a critical review of methods for measuring subjective expectations in developing countries.

3. Fieldwork supervisors comprised college-educated Malawians. Each supervisor oversaw a ‘‘cell’’ of eight to ten

fieldworkers on a daily basis; they documented their field team’s progress, assessed performance of interviewers, checked

interviewers’ completed surveys, and determined the agenda for the day. Most supervisors were in their twenties or early

thirties. They relied on itinerant work with research projects for their livelihoods and self-described themselves as ‘‘living

project to project.’’

4. One possible motivation behind statements about ‘‘culture’’ such as this that supervisors made was to do away

with the beans exercise to make data collection easier and more streamlined.

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 363

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

5. In these cases, we might view Namoyo’s responses as lies. Bleek (1987), in considering his experience with lying

informants in Ghana, views the lies research informants tell—following Salamone (1977)—as a meaningful form of

communication and not its negation (314).

6. Relish or ndiwo is what is typically eaten with the staple maize porridge called nsima.Most often, relish comprises

greens.

7. While some respondents refused to have their photo taken, most were cooperative. The taking of the ‘‘snap’’ (as

photos were commonly called in Malawi) was a quick and simple affair. The respondent in each case held up a piece of

paper on which was written, in thick black marker, their personal identification number. This gave the photo a certain

posterity—in future years, even if the respondent’s appearance changed, their number remained the same—it was

uniquely theirs in the way a hairstyle, shirt, or body type cannot be. The photographs produced some unexpected out-

comes. Gradually, villagers became aware of the ‘‘snaps’’; interviewers often showed them around to garner local help

in locating respondents and respondents themselves noticed them on the clipboards. Soon enough, project participants

began asking whether they could keep their photographs. After some discussion between the supervisors, it was decided

this was an agreeable arrangement. The photos took on a dual role: as a technical device through which researchers could

better see and as an unscripted and unintended gift that villagers appreciated more than the soap that acted as formal

compensation for research participation.

REFERENCES

Biruk, C.

2011 The production and circulation of AIDS knowledge in Malawi. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology,

University of Pennsylvania.

Bleek, W.

1987 Lying informants: A fieldwork experience from Ghana. Population and Development Review 13(2):314–322.

Caldwell, J.

1996 Demography and social science. Population Studies 50:309–316.

Cleland, J.

1996 Demographic data collection in less developed countries, 1946–1996. Population Studies 50(3):433–450.

Daston, L. and P. Galison.

2007 Objectivity. New York: Zone Books.

Delavande, A., X. Gine, and D. McKenzie.

2010 Measuring subjective expectations in developing countries: A critical review of new evidence. Journal of

Development Economics 94:151–163.

Fabian, J.

1983 Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ferguson, J.

1999 Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meaning of Urban Life on the Zambian Copper Belt. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

———.

2005 Seeing like an oil company: Space, security, and global capital in neoliberal Africa. American Anthropologist

107(3):377–382.

Foucault, M.

1978 Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France, 1977—78. New York: Picador.

Government of Malawi

2003 National HIV=AIDS Policy: A Call to Renewed Action. Lilongwe, Malawi: Author.

Gupta, A. and J. Ferguson

1992 Beyond ‘‘culture’’: Space, identity and the politics of difference. Cultural Anthropology 7(1):6–23.

———.

1997 Culture, power, place: Ethnography at the end of an era. In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical

Anthropology. A. Gupta and J. Ferguson, eds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Guyer, J., N. Khan, J. Obarrio, C. Bledsoe, J. Chu, S. Diagne, and K. Hartet al.

2010 Introduction: Number as inventive frontier. Anthropological Theory 10:36–61.

364 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

Janes, C. and K. Corbett

2009 Anthropology and global health. Annual Review of Anthropology 38:167–183.

Joffe, S.

1973 Political culture and communication in Malawi: The hortatory regime of Kamuzu Banda. PhD dissertation,

Boston University.

Koplan, J., T. Bond, M. Merson, K. Reddy, M. Rodriguez, N. Sewankambo, and J. Wasserheit

2009 Toward a common definition of global health. The Lancet 373:1933–1935.

Lampland, M.

2010 False numbers as formalizing practices. Social Studies of Science 40:377–404.

Lampland, M. and S. Star

2009 Standards and their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying, and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lwanda, J.

2005 Politics, Culture, and Medicine in Malawi: Historical Continuities and Ruptures with Special Reference to

HIV=AIDS. Zomba, Malawi: Kachere.

Lynch, M.

1988 Sacrifice and the transformation of the animal body into a scientific object: Laboratory culture and ritual

practice in the neurosciences. Social Studies of Science 18(2):265–289.

May, M.

2008 ‘‘I didn’t write the questions!:’’ Negotiating telephone-survey questions on birth timing. Demographic Research

18(18):499–530.

Morfit, N.

2011 ‘‘AIDS is Money’’: How donor priorities reconfigure local realities. World Development 39(1):64–76.

Moto, F.

2004 Towards a study of the lexicon of sex and HIV=AIDS. Nordic Journal of African Studies 13(3):343–362.

National Statistics Office

2008 Malawi National Census. Zomba, Malawi: Author.

Petryna, A.

2009 When Experiments Travel: Clinical Trials and the Search for Human Subjects. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Riedmann, A.

1993 Science that Colonizes: A Critique of Fertility Studies in Africa. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rottenburg, R.

2009 Social and public experiments and new figurations of science and politics in postcolonial Africa. Postcolonial

Studies 12(4):423–440.

Salamone, F.

1977 The methodological significance of the lying informant. Anthropological Quarterly 50(3):117–124.

Schumaker, L.

2001 Africanizing Anthropology: Fieldwork, Networks, and the Making of Cultural Knowledge in Central Africa.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Scott, J.

1998 Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Sridhar, D. and R. Batniji

2008 Misfinancing global health: The case for transparency in disbursements and decision-making. Lancet 372:185–191.

Tilley, H.

2011 Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870–1950.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Turnbull, D.

2000 Masons, Tricksters, and Cartographers. London: Gordon and Breach.

UNAIDS

2008 Epidemiological fact sheet on HIV and AIDS, update: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva:

UNAIDS.

SEEING LIKE A RESEARCH PROJECT 365

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12

———.

2009 Malawi: 2009 AIDS epidemic update. Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNGASS.

2010 Malawi: UNGASS country progress report. Malawi: Government of Malawi.

Vaughan, M.

1991 Curing Their Ills: Colonial Power and African Illness. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

World Bank

2009 Seizing Opportunities for Growth Through Regional Integration and Trade: Malawi Country Economic

Memorandum. Washington, DC: World Bank.

366 C. BIRUK

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f Pe

nnsy

lvan

ia]

at 1

6:33

28

Sept

embe

r 20

12