Research Article Utility of the Mini-Cog for Detection of ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Research Article Utility of the Mini-Cog for Detection of ...

Hindawi Publishing CorporationInternational Journal of Alzheimer’s DiseaseVolume 2013, Article ID 285462, 7 pageshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/285462

Research ArticleUtility of the Mini-Cog for Detection of Cognitive Impairment inPrimary Care: Data from Two Spanish Studies

Cristóbal Carnero-Pardo,1,2 Isabel Cruz-Orduña,3 Beatriz Espejo-Martínez,4

Carolina Martos-Aparicio,1 Samuel López-Alcalde,1 and Javier Olazarán5,6

1 Neurology Service, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital, Granada, Spain2 FIDYAN Neurocenter, Granada, Spain3 Neurology Service, Infanta Leonor Hospital, Madrid, Spain4Neurology Service, La Mancha Centro Hospital, Alcazar de San Juan, Spain5Hermanos Sangro Specialties Clinic, Neurology Service, Gregorio Maranon General University Hospital, Madrid, Spain6Alzheimer Disease Research Unit, Alzheimer Center Reina Sofia Foundation-CIEN Foundation, Carlos III Institute of Health,Madrid, Spain

Correspondence should be addressed to Cristobal Carnero-Pardo; [email protected]

Received 29 April 2013; Revised 16 July 2013; Accepted 19 July 2013

Academic Editor: Jesus Avila

Copyright © 2013 Cristobal Carnero-Pardo et al.This is an open access article distributed under theCreativeCommonsAttributionLicense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in anymedium, provided the originalwork is properly cited.

Objectives. To study the utility of the Mini-Cog test for detection of patients with cognitive impairment (CI) in primary care(PC). Methods. We pooled data from two phase III studies conducted in Spain. Patients with complaints or suspicion of CIwere consecutively recruited by PC physicians. The cognitive diagnosis was performed by an expert neurologist, after formalneuropsychological evaluation. TheMini-Cog score was calculated post hoc, and its diagnostic utility was evaluated and comparedwith the utility of the Mini-Mental State (MMS), the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), and the sum of the MMS and the CDT(MMS + CDT) using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The best cut points were obtained on thebasis of diagnostic accuracy (DA) and kappa index. Results. A total sample of 307 subjects (176 CI) was analyzed. The Mini-Cogdisplayed an AUC (±SE) of 0.78±0.02, which was significantly inferior to the AUC of the CDT (0.84±0.02), theMMS (0.84±0.02),and theMMS+CDT (0.86±0.02).The best cut point of the Mini-Cog was 1/2 (sensitivity 0.60, specificity 0.90, DA 0.73, and kappaindex 0.48 ± 0.05). Conclusions. The utility of the Mini-Cog for detection of CI in PC was very modest, clearly inferior to the MMSor the CDT. These results do not permit recommendation of the Mini-Cog in PC.

1. Introduction

The aging of the population has come along with an increasein the incidence of cognitive impairment (CI) [1], a clinicalsyndrome that, in about one-third of the patients, precedesdementia [2]. An early detection of CI could produce benefitsat different levels, including early dementia diagnosis, accessto treatments, and delay or even reversion of cognitivedeterioration [3–5].

Primary care (PC) presents optimal characteristics ofaccessibility and continuity of care, which are essential forearly detection and management of CI [6]. In this vein,the focus of the PC physicians should be the detection of

CI, rather than dementia. A separation of mild cognitiveimpairment (MCI) and dementia would not only be difficultor arbitrary in many instances but would also lead to missingopportunities for treatment and research [7].

The detection of CI requires a proactive attitude and theuse of cognitive tests. In PC, cognitive tests need to be briefand easy to administer and interpret. In addition, these testsshould have been specifically validated in the PC setting,with an adequate control of the potential influence of age,education, and other social variables [8]. Albeit not simple,rather long, and very influenced by education, the Mini-Mental State (MMS) [9] is still themost used cognitive test. Asadditional limitations, theMMS displayedmodest diagnostic

2 International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease

utility for detection of CI in PC [10, 11] and was recentlyprotected by copyright [12].

TheMini-Cog is a very simple and brief cognitive test thatcomprises a three-item verbal memory task and a simplifiedevaluation of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT). According totheir authors, the Mini-Cog is not influenced by education[13]. Indeed, in a population-based study, this test was aseffective as a formal neuropsychological battery for detectingdementia [14]. The Mini-Cog was also well accepted by thepatients [15], displayed good correlation with the MMS [16],andwas recently recommended in some consensus guidelinesand reviews [17–20]. However, there are very few studiesaddressing the yield of the Mini-Cog for detection of CI (i.e.,both MCI and dementia), which displayed conflicting results[21, 22].

The objective of the present study was to evaluate thediagnostic utility of the Mini-Cog for detection of CI inpatients who presented with complaints or suspicion ofcognitive deterioration in PC.

2. Methods

We analyzed data from two phase III studies of evaluationof diagnostic instruments [23] that were conducted in twodifferent cities of Spain (i.e., Madrid and Granada). Thestudy of Madrid was conducted in the Hermanos Sangrohealth center (Health District 1, Autonomous Communityof Madrid, urban area), and the study of Granada was con-ducted in the Almanjayar/Cartuja, the Caserıa de Montijo,and the Salvador Caballero health centers (Health DistrictGranada Norte, Autonomous Community of Andalucıa,urban area). The methods of these studies were describedin detail elsewhere [24, 25]. In the two studies, patients andcaregivers were informed of the procedures and purposeof the studies and gave their consent to participate. Otheressential common characteristics of the two studies were asfollows.

2.1. Setting. The recruitment of patients and the adminis-tration of the screening instruments were performed in PC,whereas the formal neuropsychological evaluation and thefinal diagnosis (gold standard) were performed in specializedcare (SC), which replicates the standards of clinical practice.

2.2. Recruitment. The patients were prospectively and con-secutively recruited by the PC physicians. All the subjectswho presented with complaints or suspicious (either byinformant or by family physician) regarding cognitive dys-function or cognitive deteriorationwere invited to participatein the study. Patients with a former diagnosis of CI were notincluded.

2.3. Screening Instruments. A validated Spanish version ofthe MMS was utilized, with the modification of ignoring thepossibility of spelling world backwards [26]. The CDT wasscored from 0 to 7 [27]; in one of the sites (Granada), therequested time was “ten past eleven,” whereas in the other site(Madrid) the requested time was “twenty to four.” Otherwise,

the instructions for the clock drawing test in the two siteswere alike (i.e., “please, draw a big round clock, put all thenumbers on it, and display the hands on (requested time)”).The score of the Mini-Cog was obtained post-hoc, for thepurpose of the present investigation. One point was givenfor every recalled word from the MMS delayed recall task,and two additional points were given if the clock fulfilledthe following conditions: (a) all the numbers from 1 to 12were included and there was no repeated number, (b) all thenumbers were in the right order and direction, and (c) thehands unequivocally displayed the requested time.Hence, thescore of the Mini-Cog varied from 0 to 5 [21].

2.4. Cognitive Diagnosis (Gold Standard). Mild cognitiveimpairment (MCI) was diagnosed on the basis of the follow-ing criteria: (a) an abnormal performance was documentedin at least one neuropsychological test; (b) that abnormalperformance was deemed to be of clinical relevance (i.e.,not due to low premorbid level, lack of motivation, etc.),and (c) dementia criteria were not fulfilled. The diagnosisof dementia was made according to the 4th edition, textrevised, of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of MentalDisorders (DSM-IV-TR) [28]. The cognitive diagnosis wasperformed by two senior neurologists with expertise incognitive and behavioural neurology (CC, JO) after medicalvisit, neurological exam,mental status exam, and formal neu-ropsychological evaluation, which included tests of memory,attention/executive functions, language, and visual-spatialabilities [24, 25]. Throughout the study, laboratory deter-minations and other ancillary tests (e.g., cranial computedtomography scan) were performed as the clinical situationindicated.

2.5. Independence of the Cognitive Diagnosis. The results ofthe screening instruments were not utilized for the cognitivediagnosis in the original studies. However, for the presentinvestigation, the CDT, which was a screening instrumentin the study of Granada but was included in the formalneuropsychological evaluation in the study of Madrid, wasanalyzed as a screening instrument.

2.6. Double Blinding. The screening instruments wereadministered before the neuropsychological and neurologicalexams were conducted, in different settings (PC versus SC)and by different professionals. The neurologists, whoperformed the cognitive diagnosis, were blind to the resultsof the screening instruments with the exception of theCDT in the study of Madrid, as mentioned in the previousparagraph.

2.7. Reference Bias. Complete verification was conducted;that is, all the recruited patients received the same neu-ropsychological and neurological assessment and all of themreceived a final cognitive diagnosis, independently of theresults in the screening instruments [29].

There were some differences between the two studiesregarding age and period of inclusion. In the study ofMadrid,only ≥50 year old patients were recruited, and the period of

International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 3

inclusion ran from April 1, 2000 to October 31, 2002 (i.e., 31months). There was no age limit in the study of Granada andthe period of inclusion of that study ran from February 1,2008 to January 31, 2009 (i.e., 1 year). The study of Granadawas approved by the Hospital Virgen de las Nieves EthicsCommittee, and participants signed informed consent. Inthe study of Madrid, only verbal consent was required frompatients and caregivers/informants.

Statistical Analysis. Bivariate comparisons between quantita-tive variables were performed using Student’s 𝑡-test, whereasqualitative variables were compared using chi-square andFisher exact tests. A potential influence of site was specificallyaddressed by means of two-factor (site [Granada versusMadrid] × cognitive diagnosis [CI versus no CI]) analysisof covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for age (years), sex (manversus woman), and education (no or incomplete primaryeducation versus primary or higher education).

The diagnostic utility of the Mini-Cog, the CDT, theMMS, and the sum of theMMS and the CDT scores (MMS +CDT) was evaluated and compared for detection of CI(MCI or dementia) using receiver operating characteristic(ROC) curves. Differences between the areas under thecurve (AUC) were analyzed using the Hanley and McNeilcorrection to compare diagnostic tests in the same sample[30]. In addition, the sensitivity (Sn), the specificity (Sp), thepositive likelihood ratio (LR+), the diagnostic accuracy (DA)(proportion of patients correctly classified), and the kappaindex of diagnostic concordance were obtained for all the cutpoints in all the tests. The best cut point was chosen for eachtest on the basis of maximization of DA and kappa index.

The interrater reliability of theMini-Cogwas evaluated ina subsample of 50 subjects (first 25 subjects included in eachsite). Four evaluators that were blind to one another and toall other study variables scored the clocks and the three-itemrecall tasks of those subjects, and the intra-class correlationcoefficient (ICC) was calculated.

All the statistical tests were two tailed, and a level of𝑃 < 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance. Statisticalanalyses were performed using the SPSS 15.01 and MedCalc12.3 software.

3. Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the totalsample and of the two original samples are presented inTable 1. Overall, there was predominance of female sex(72.0%), and the educational achievement was low (50.8%of the participants had not complete primary education).The frequency of illiteracy was particularly high in theparticipants from Granada (14.1% versus 4.8%, 𝑃 ≤ 0.009).Patients fromGranada also presentedwith a higher frequencyof dementia (34.5% versus 9.1, 𝑃 ≤ 0.001) and obtained lowerscores in all the cognitive tests (Table 1).

As it was expected, the subjects with MCI or dementiawere older than the subjects with normal cognition (NC).Thesubjects with CI had also less educational achievement andscored lower in all the cognitive tests (Table 2). There wereno sex differences across the different cognitive diagnoses.

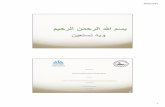

Figure 1 represents the distribution of the Mini-Cog score inthe two study groups.

The score of theMini-Cog was significantly influenced byage (𝑃 ≤ 0.001) and education (𝑃 ≤ 0.002) but not by sex(𝑃 = 0.99) or study site (𝑃 = 0.18). A total of 16 participantsbelonging to the sample of Granada (11.3% of patients fromGranada, 5.2% of the total sample, and 11 of them illiterates)did not even try to draw the clock, in which case a zero scorewas given.

Thediagnostic yield of theMini-Cogwas inferior (AUC ±SE 0.78 ± 0.02), compared to that of the MMS (0.84 ± 0.02,𝑃 ≤ 0.001), the CDT (0.84 ± 0.02, 𝑃 ≤ 0.001), and theMMS + CDT (0.86 ± 0.02, 𝑃 ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2). The bestcut point of the Mini-Cog was 1/2, with Sn 0.60 (confidenceinterval (CI) 95% 0.53–0.67), Sp 0.90 (CI 95% 0.84–0.95),LR+ 6.1 (CI 95% 3.6–0.3), DA 0.73, and kappa index 0.48 ±0.05). The usually recommended cut point of the Mini-Cogof 2/3 displayed an inferior utility, with Sn 0.78 (CI 95% 0.71–0.84), Sp 0.59 (CI 95% 0.51–0.68), DA 0.70, and kappa index0.38 ± 0.04 (Table 3). Using a cut point of 22/23, the MMShad similar Sn (0.76, CI 95% 0.68–0.82), but better Sp (0.76,CI 95% 0.68–0.83) and DA (0.76). As for the CDT, a cut pointof 5/6 achieved similar results to those of the MMS, with Sn0.76 (CI 95% 0.68–0.82), Sp 0.78 (CI 95% 0.70–0.85), and DAof 0.76. The MMS + CDT was slightly, but not significantly,superior to the MMS or the CDT alone (Table 4, Figure 2).

TheMini-Cog displayed an excellent interrater reliability,with an ICC (±SD) of 0.97 ± 0.01.

4. Discussion

We pooled data of two homogeneous studies to ascertain thevalue of the Mini-Cog for detection of CI (either MCI ordementia) in PC. The score of the Mini-Cog was obtainedpost-hoc, utilizing data from the MMS and the CDT. Thediagnostic utility obtained by the Mini-Cog was low, withan AUC (±SE) of 0.78 ± 0.02 and a percentage of correctlyclassified subjects of 70%, when the recommended cutoff of2/3 was applied [21]. A cut point of 1/2 obtained a slightlybetter yield (73% of cases correctly classified) on the basisof a good specificity (0.90 (CI 95% 0.84–0.95)) but a lowsensitivity (0.60 (0.53–0.67)), which was unacceptable for adetection test.

The diagnostic utility of the Mini-Cog was inferior tothat of the MMS, which was moderate (AUC 0.84 ± 0.02).When the best MMS cut point was applied (i.e., 22/23), thesensitivity and specificity were modest (0.76 (0.68–0.82)),and the percentage of cases correctly classified did not reach80% (DA 0.76) (Table 4). These modest results of the MMScoincide with other study conducted in PC [10] and withthe results from two systematic reviews [11, 18]. Albeit alsomodest, the results obtained by the CDT in the presentinvestigationwere superior to the results obtained in previousstudies [31] that led to disregard of the CDT for detection ofMCI [32]. A possible explanation for our better results withtheCDT is that this test was included, in one of the study sites,in the reference diagnosis. We also evaluated the diagnosticutility of the sumof scores of theMMS and theCDT, but there

4 International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total study sample and of the two original samples.

Total Madrid Granada 𝑃 value𝑛 307 165 142Female gender 221 (72.0) 118 (71.5) 103 (72.5) 0.90Age, years 72.0 ± 10.1 71.9 ± 8.9 72.1 ± 11.4 0.84Educational level<Primary 156 (50.8) 84 (50.9) 72 (50.7) 1.00≥Primary 151 (49.2) 81 (49.1) 70 (49.3)

Cognitive diagnosisNC 131 (42.7) 75 (45.5) 56 (39.4)

≤0.001MCI 112 (36.5) 75 (45.5) 37 (26.1)DEM 64 (20.8) 15 (9.1) 49 (34.5)

Mini-Cog 2.0 ± 1.7 2.4 ± 1.7 1.5 ± 1.5 ≤0.001MMS 21.3 ± 5.2 22.3 ± 4.5 19.9 ± 5.7 ≤0.001CDT 4.5 ± 2.5 5.0 ± 2.0 4.0 ± 2.8 ≤0.001MMS + CDT 25.7 ± 7.2 27.3 ± 6.0 23.9 ± 8.1 ≤0.001Data represent number of individuals (%) or mean ± SD. MMS: Mini-Mental State; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; DEM: dementia; NC: normal cognition; MCI:mild cognitive impairment.

Table 2: Demographic characteristics and test results by cognitive diagnosis.

NC CI MCI DEM 𝑃 value∗

𝑛 131 176 112 64Female gender 100 (76.3) 121 (68.8) 74 (66.1) 47 (73.4) 0.09Age, years 66.9 ± 10.4 75.8 ± 8.1 73.6 ± 8.1 79.6 ± 6.5 ≤0.001Educational level<Primary 48 (36.6) 108 (61.4) 63 (56.3) 45 (70.3)

≤0.001≥Primary 83 (63.4) 68 (38.6) 49 (43.8) 19 (29.7)

Mini-Cog 2.9 ± 1.3 1.2 ± 1.5 1.7 ± 1.7 0.4 ± 0.8 ≤0.001MMS 24.6 ± 3.0 18.7 ± 5.1 21.2 ± 4.0 14.2 ± 3.8 ≤0.001CDT 6.1 ± 1.3 3.3 ± 2.4 4.4 ± 2.0 1.4 ± 1.9 ≤0.001MMS + CDT 30.7 ± 3.7 22.0 ± 7.0 25.6 ± 5.2 15.8 ± 5.1 ≤0.001Data represent number of individuals (%) ormean± SD.MMS:Mini-Mental State; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; NC: normal cognition; CI: cognitive impairment(MCI or dementia); DEM: dementia; MCI: mild cognitive impairment.∗For the comparison between NC versus CI (MCI or dementia).

Table 3: Utility of the Mini-Cog for the detection of CI (MCI or dementia).

Cutoff Sn Sp LR+ DA 𝜅

≤0 0.53 (0.45–0.60) 0.94 (0.88–0.97) 8.6 (4.4–17.2) 0.70 0.43 ± 0.04

≤1 0.60 (0.53–0.67) 0.90 (0.84–0.95) 6.1 (3.6–10.3) 0.73 0.48 ± 0.05

≤2 0.78 (0.71–0.84) 0.59 (0.51–0.68) 1.9 (1.5–2.4) 0.70 0.38 ± 0.05

≤3 0.88 (0.82–0.92) 0.38 (0.30–0.47) 1.4 (1.2–1.6) 0.67 0.28 ± 0.05

≤4 0.96 (0.92–0.98) 0.14 (0.08–0.21) 1.1 (1.0–1.2) 0.61 0.11 ± 0.04

≤5 1.00 (0.98–1.00) 0.00 (0.00–0.03) 1.0 (1.0–1.0) 0.67 0.00 ± 0.00

DA: diagnostic accuracy (proportion of correct diagnoses); 𝜅: kappa index; LR+: positive likelihood ratio; Sn: sensibility; Sp: specificity.

Table 4: Utility of the screening tests for the detection of CI (MCI or dementia) using the best cut points.

Test Cutoff Sn Sp DA 𝜅

Mini-Cog 1/2 0.60 (0.53–0.67) 0.90 (0.84–0.95) 0.73 0.48 ± 0.05

MMS 22/23 0.76 (0.68–0.82) 0.76 (0.68–0.83) 0.76 0.51 ± 0.05

CDT 5/6 0.76 (0.68–0.82) 0.78 (0.70–0.85) 0.76 0.53 ± 0.05

MMS + CDT 25/26 0.65 (0.58–0.72) 0.93 (0.87–0.97) 0.77 0.56 ± 0.05

aROC: area under curve ROC; Sn: sensibility; Sp: specificity; DA: diagnostic accuracy (proportion of correct diagnoses); 𝜅: kappa index; MMS: Mini-MentalState; CDT: Clock Drawing Test.

International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 5

120

8

93

5

13

31

40

28

18 147

18

32

100

80

60

40

20

00 1 2 3 4 5

Mini-Cog

NCCI (MCI or dementia)

Freq

uenc

y

Figure 1: Frequency of Mini-Cog individual scores according tocognitive diagnosis. CI: cognitive impairment; MCI: mild cognitiveimpairment; NC: normal cognition.

was no significant gain, with a clear increase in testing time,when compared to the MMS or the CDT alone. That result isalso in agreement with a previous investigation [33].

In previous research, the Mini-Cog displayed good per-formance for detection of dementia, with figures that weresimilar [14] or even superior [34] to those obtained by theMMS or the CDT. To the authors’ knowledge, only twostudies had so far addressed the utility of the Mini-Cogfor detection of CI, with conflicting results. In a sampleof predominantly male old people, the results of the Mini-Cog were not satisfactory (AUC 0.64) [22], whereas, in astudy conducted in a sample of predominantly “unservedethnic minorities,” a diagnostic accuracy of 0.83 was reported[21]. The proportion of patients with dementia, that differeddramatically in those studies (3.3% dementia, 39.2% MCI inHolsinger’s study [22] versus 41.5% dementia, 21.3% MCI inBorson’s study [21]), could explain the reported differencesin the diagnostic yield of the Mini-Cog. Our results, ina sample of intermediate characteristics (20.8% dementia,36.5% MCI) (Table 1), were also intermediate in terms ofMini-Cog diagnostic utility (diagnostic accuracy 0.73, AUC0.78) (Table 3 and Figure 2). Clearly, all these data adviseagainst the use of theMini-Cog for detection of CI in settingswhere the suspected proportion of unrecognized dementia islow.

We found a significant influence of education in theMini-Cog performance, which was not in agreement withthe original validation study [13]. This discrepancy can beexplained in the light of the low educational achievement ofour sample (Table 1). In the original validation study, all theparticipants had completed at least six years of education,whereas in the present study, a proportion of 50.8% of the

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

00 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

Sens

ibili

tyMMS + CDT (0.86 ± 0.02)CDT (0.84 ± 0.02)

MMS (0.84 ± 0.02)Mini-Cog (0.78 ± 0.02)

1− specificity

Figure 2: ROC curves for detection of CI (MCI or dementia). Thearea (±SD) under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC)is indicated. MMS: Mini-Mental State; CDT: Clock Drawing Test;CI: cognitive impairment; MCI: mild cognitive impairment.

subjects had not complete primary school, which in Spainusually means less than eight years of formal education,and there was 9.1% of illiteracy (Table 1). There is strongevidence of the influence of education and literacy on CDTperformance [31, 35], and reasonably this should be the samewith the Mini-Cog. In fact, poor yield of the Mini-Cog waspreviously reported for dementia detection in a sample of loweducational level [36]. Overall, these data suggest a negativeinfluence of education on the Mini-Cog, restricted to themost inferior educational strata.

Our study had some limitations. First, the CDT was partof the reference diagnosis in one of the study sites, a limitationthat could have overvalued the utility of the Mini-Cog andtherefore would not essentially alter the study conclusions.Second, the score of the Mini-Cog was obtained post-hocfrom two different tests. This methodology was used byseveral researchers with exploratory purposes, including theoriginal descriptions of the Mini-Cog [13, 14] to ascertainthe validity of the test [34]. Certainly, the obtained resultsdiscourage future prospective studies of theMini-Cog.Third,the present results were derived from two slightly differentstudies. However, the results obtained by the Mini-Cog ineach of the individual studies were similar (data not shown),which strengthens the consistence and the external validityof the presented global results. As additional strength, thetwo pooled studies fulfilled the standards of high-qualityphase III diagnostic studies [37], a consecutive and systematicrecruitment was conducted, and there were virtually noexclusion criteria.

6 International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease

5. Conclusions

Simplicity and shortness in time are indeed characteristics ofthe Mini-Cog, which are necessary for use in PC. However,the Mini-Cog was not a valid choice in the studied sample,and this result, which was consistent with previous research,advise against the use of theMini-Cog, particularly in settingswhere the proportion of unrecognized dementia is low. Inthese settings, the use of tests that offer a wider range oftasks and score, yet maintaining acceptability and feasibility,seems more adequate [38]. In light of the relevance of thedetection of CI, more human and technical resources shouldbe implemented in PC.

Conflict of Interests

The authors do not have any direct financial relation withthe trademarks mentioned in the paper that might lead toa conflict of interests for any of the authors. Dr. Carnero-Pardo is the author of the Phototest and theEurotest, two briefcognitive tests under license of Creative Commons. The restof the authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The study of Granada was funded by the Agencia de Eval-uacion de Tecnologıas Sanitarias, Instituto de Salud CarlosIII (Expdte PI06/90034). The funding source had no rolein the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation,or writing of the report. The authors are grateful to all ofthe primary healthcare professionals who participated inthe study: Pedro Torrero, Esperanza Aparicio, Ana Sanz,Nieves Mula, Garbine Marzana, Dionisio Cabezon, Con-cepcion Begue, Samuel Lopez, Carolina Martos, EstrellaMora, Rosa Vılchez, Francisco Romo, Mª Jose Rodrıguez,Francisco Suarez, Felix Rodrıguez, Rafael Moya, ConcepcionLopez, Barbara Martınez, Isabel Valenzuela, Victoria Molina,Ana Mª Zamora, Jose Antonio Henares, Isabel Rodrıguez,Carmen Romero, Manuel Jimenez, Francisco Padilla, MiguelMelguizo, Ana Mª de los Rıos, Ascension Cano, ManuelAlonso, Jose LuisMartın, Jose Lopez, Ambrosio Esteva, Fran-cisca Dorador, Dolores Sanchez, Jose A. Lopez, Mª AngelesJurado, Yarmila Garcıa, Eduardo Fernandez, Consuelo Perez,Jose Antonio Castro, Araceli Zambrano, and Hassan Mah-moud.

References

[1] T. Luck, M. Luppa, S. Briel, and S. G. Riedel-Heller, “Incidenceof mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review,” Dementiaand Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 164–175,2010.

[2] A. J. Mitchell and M. Shiri-Feshki, “Rate of progression of mildcognitive impairment to dementia—meta-analysis of 41 robustinception cohort studies,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, vol.119, no. 4, pp. 252–265, 2009.

[3] R. T.Woods, E. Moniz-Cook, S. Iliffe et al., “Dementia: issues inearly recognition and intervention in primary care,” Journal ofthe Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 96, no. 7, pp. 320–324, 2003.

[4] D. L. Weimer and M. A. Sager, “Early identification andtreatment of Alzheimer’s disease: social and fiscal outcomes,”Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 215–226, 2009.

[5] T. Etgen, D. Sander, H. Bickel, and H. Forstl, “Mild cognitiveimpairment and dementia: the importance of modifiable riskfactors,” Deutsches Arzteblatt International, vol. 108, no. 44, pp.743–750, 2011.

[6] J. Olazaran, “Can dementia be diagnosed in primary care?”Atencion Primaria, vol. 43, no. 7, pp. 377–384, 2011.

[7] M. S. Rafii and D. Galasko, “Primary care screening for demen-tia and mild cognitive impairment,” Journal of the AmericanMedical Association, vol. 299, no. 10, p. 1132, 2008.

[8] H. Brodaty, L.-F. Low, L. Gibson, and K. Burns, “What is thebest dementia screening instrument for general practitioners touse?” The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 14, no.5, pp. 391–400, 2006.

[9] M. F. Folstein, S. E. Folstein, and P. R. McHugh, “’Mini mentalstate’. a practical method for grading the cognitive state ofpatients for the clinician,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol.12, no. 3, pp. 189–198, 1975.

[10] P. Pezzotti, S. Scalmana, A. Mastromattei, and D. Di Lallo, “Theaccuracy of theMMSE in detecting cognitive impairment whenadministered by general practitioners: a prospective obser-vational study,” BMC Family Practice, vol. 9, no. 29, 2008.

[11] A. J. Mitchell, “A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia andmildcognitive impairment,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 43,no. 4, pp. 411–431, 2009.

[12] J. C. Newman and R. Feldman, “Copyright and open access atthe bedside,”TheNew England Journal of Medicine, vol. 365, no.26, pp. 2447–2449, 2011.

[13] S. Borson, J. Scanlan, M. Brush, P. Vitaliano, and A. Dokmak,“The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementiascreening in multi-lingual elderly,” International Journal ofGeriatric Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 1021–1027, 2000.

[14] S. Borson, J. M. Scanlan, P. Chen, and M. Ganguli, “The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-basedsample,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 51, no.10, pp. 1451–1454, 2003.

[15] J. R. McCarten, P. Anderson, M. A. Kuskowski, S. E. McPher-son, and S. Borson, “Screening for cognitive impairment inan elderly veteran population: acceptability and results usingdifferent versions of the Mini-Cog,” Journal of the AmericanGeriatrics Society, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 309–313, 2011.

[16] G. Kamenski, T. Dorner, K. Lawrence et al., “Detection ofdementia in primary care: comparison of the original anda modified Mini-Cog assessment with the mini-mental stateexamination,” Mental Health in Family Medicine, vol. 6, no. 4,pp. 209–217, 2009.

[17] J. A. Lonie, K. M. Tierney, and K. P. Ebmeier, “Screening formild cognitive impairment: a systematic review,” InternationalJournal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 902–915, 2009.

[18] D. Kansagara and M. Freemam, Systematic Evidence Review ofthe Signs and Symptoms of Dementia and Brief Cognitive TestsAvailable in VA, VA-ESP Project #05-225, 2010.

[19] C. B. Cordell, S. Borson, M. Boustani et al., “Alzheimer’s asso-ciation recommendations for operationalizing the detection ofcognitive impairment during themedicare annual wellness visitin a primary care setting,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 9, no. 2,pp. 141–150, 2012.

International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 7

[20] A. Milne, A. Culverwell, R. Guss, J. Tuppen, and R. Whelton,“Screening for dementia in primary care: a review of the use,efficacy and quality of measures,” International Psychogeriatrics,vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 911–926, 2008.

[21] S. Borson, J. M. Scanlan, J. Watanabe, S.-P. Tu, and M. Lessig,“Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparisonof the Mini-Cog and mini-mental state examination in amultiethnic sample,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 871–874, 2005.

[22] T. Holsinger, B. L. Plassman, K. M. Stechuchak, J. R. Burke,C. J. Coffman, and J. W. Williams Jr., “Screening for cognitiveimpairment: comparing the performance of four instrumentsin primary care,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol.60, no. 6, pp. 1027–1036, 2012.

[23] D. L. Sackett and R. B. Haynes, “The architecture of diagnosticresearch,” British Medical Journal, vol. 324, no. 7336, pp. 539–541, 2002.

[24] C. Carnero-Pardo, B. Espejo-Martinez, S. Lopez-Alcalde et al.,“Effectiveness and costs of phototest in dementia and cognitiveimpairment screening,” BMC Neurology, vol. 11, no. 92, 2011.

[25] I. Cruz-Orduna, J. M. Bellon, P. Torrero et al., “Detecting MCIand dementia in primary care: efficiency of the MMS, the FAQand the IQCODE,” Family Practice, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 401–406,2012.

[26] R. Blesa, M. Pujol, M. Aguilar et al., “Clinical validity of the’mini-mental state’ for Spanish speaking communities,” Neuro-psychologia, vol. 39, no. 11, pp. 1150–1157, 2001.

[27] P. R. Solomon, A. Hirschoff, B. Kelly et al., “A 7 minute neu-rocognitive screening battery highly sensitive to Alzheimer’sdisease,” Archives of Neurology, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 349–355, 1998.

[28] American Psychiatry Association, Diagnostic and StatisticalManual ofMental Disorders, Text Revision, DSM-IV-TR, Amer-ican Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA, 4th edi-tion, 2000.

[29] P. M. Bossuyt, L. Irwig, J. Craig, and P. Glasziou, “Comparativeaccuracy: assessing new tests against existing diagnostic path-ways,” British Medical Journal, vol. 332, no. 7549, pp. 1089–1092,2006.

[30] J. A. Hanley and B. J. McNeil, “Amethod of comparing the areasunder receiver operating characteristic curves derived from thesame cases,” Radiology, vol. 148, no. 3, pp. 839–843, 1983.

[31] E. Pinto and R. Peters, “Literature review of the clock drawingtest as a tool for cognitive screening,” Dementia and GeriatricCognitive Disorders, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 201–213, 2009.

[32] L. Ehreke, M. Luppa, H.-H. Konig, and S. G. Riedel-Heller,“Is the clock drawing test a screening tool for the diagnosis ofmild cognitive impairment? A systematic review,” InternationalPsychogeriatrics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 56–63, 2010.

[33] J. Cacho, J. Benito-Leon, R. Garcıa-Garcıa, B. Fernandez-Calvo,J. L. Vicente-Villardon, and A. J. Mitchell, “Does the com-bination of the MMSE and clock drawing test (mini-clock)improve the detection of mild Alzheimer’s disease and mildcognitive impairment?” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 22,no. 3, pp. 889–896, 2010.

[34] M. Milian, A. M. Leiherr, G. Straten, S. Muller, T. Leyhe, andG. W. Eschweiler, “The Mini-Cog versus the mini-mental stateexamination and the clock drawing test in daily clinical practice:screening value in a German Memory Clinic,” InternationalPsychogeriatrics, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 766–774, 2012.

[35] H. Kim and J. Chey, “Effects of education, literacy, and dementiaon the clock drawing test performance,” Journal of the Interna-tional Neuropsychological Society, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 1138–1146,2010.

[36] R. A. Lourenco and S. T. Ribeiro Filho, “The accuracy of theMini-Cog in screening low-educated elderly for dementia,”Journal of the AmericanGeriatrics Society, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 376–377, 2006.

[37] P. F.Whiting, A.W. S. Rutjes, M. E.Westwood et al., “Quadas-2:a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracystudies,”Annals of InternalMedicine, vol. 155, no. 8, pp. 529–536,2011.

[38] C. Carnero-Pardo, B. Espejo-Martınez, S. Lopez-Alcalde etal., “Diagnostic accuracy, effectiveness and cost for cognitiveimpairment and dementia screening of three short cognitivetests applicable to illiterates,” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 11, ArticleID e27069, 2011.

Submit your manuscripts athttp://www.hindawi.com

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity

Hindawi Publishing Corporation http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013Hindawi Publishing Corporation http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

The Scientific World Journal

International Journal of

EndocrinologyHindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2013

ISRN Anesthesiology

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

OncologyJournal of

Volume 2013

PPARRe sea rch

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

OphthalmologyJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

ISRN Allergy

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

BioMed Research International

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

ObesityJournal of

ISRN Addiction

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine

ISRN AIDS

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Clinical &DevelopmentalImmunology

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

Volume 2013

Diabetes ResearchJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Volume 2013Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

ISRN Biomarkers

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2013

MEDIATORSINFLAMMATION

of