“Relations between East and West in the Lordship of Athens and Thebes after 1204. Archaeological...

Transcript of “Relations between East and West in the Lordship of Athens and Thebes after 1204. Archaeological...

Ar

ch

aeo

log

y a

nd

th

e C

ru

sad

es

Archaeologyand the

Crusades

Pierides Foundation

EDITED BY

Peter Edburyand

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti

ISBN 9963-9071-2-1

In the last few years archaeology has shed much light on the impact of the crusades on the lands around the eastern Mediterranean. These papers, by leading scholars working in this field and highlighting re-cent scholarship, were presented at a roudtable held in Nicosia in Feb-ruary 2005.

Editors: Peter Edbury, Professor of Medieval History, Cardiff University Sophia Kalopissi-Verti, Professor of Byzantine Archaeology,

University of Athens.

V

������������ ���������� ���

������ ��������������� ��������������������������������

� ��� ���������� ����

�� � �!����"���!����#$�����

����

Pierides Foundation

Athens

VI

© Copyright Pierides Foundation and the authors 2007 ISBN 9963-9071-2-1 From cover images: Large: Detail from St Mary of the Castle: St Lucia. Mid-14th century, Rhodes. Small: Portable icon, with the Virgin and Child, dedicated by Knight Hospitaller Jacques Gâtineau. Early 16th century, Church of Ephtagonia, Cyprus. This book is distributed by Oxbow Books, Park End Place, Oxford OX1 1HN (Phone: 01865-24249; Fax: 01865-794449) and The David Brown Book Company PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA (Phone:860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468) and via the website www.oxbowbooks.com Printed in Greece by Scriptsoft, Athens

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec-tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

VII

The proceedings of the Round Table “Archaeology and the Crusades” and the Public Lecture “Crusades and their Critics” are published within the framework of the project “Crossings: Movements of People and Movement of Cultures: Changes in the Mediterranean from Ancient to Modern Times”, which is sup-ported by the European Union Framework Programme, Culture 2000.

Leader: Pierides Foundation - Cyprus Co-organisers: Foundation of the Hellenic World – Greece, Superintendence of Cultural Heritage – Malta, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche –��������������� Recherches en Arts, Images et Formes, Université de Picardie Jules Verne – France

Organised by:

With the support of:

Culture 2000

IX

�%����� �

Addresses........................................................................................................ XI

Foreword.................................................................................................... XV

List of Abbreviations ................................................................................. XVII

Relations between East and West in the Lordship of Athens and Thebes after 1204: Archaeological and Artistic Evidence Sophia Kalopissi-Verti.......................................................................... 1

Archaeology on Rhodes and the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem Anna-Maria Kasdagli, Angeliki Katsioti and Maria Michaelidou ....... 35

The Crusaders, Sugar Mills and Sugar Production in Medieval Cyprus Marina Solomidou-Ieronymidou .......................................................... 63

Perspectives on Visual Culture in Early Lusignan Cyprus: Balancing Art and Archaeology Annemarie Weyl Carr ........................................................................... 83

The Churches of Crusader Acre: Destruction and Detection Denys Pringle ....................................................................................... 111

Coin circulation in the villeneuves of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: The Cases of Parva Mahumeria and Bethgibelin Robert Kool .......................................................................................... 133

The�� ��������������� Balázs Major ........................................................................................ 157

Concluding Remarks Nicholas Coureas ................................................................................. 173

Appendix

The Crusades and their Critics Peter Edbury......................................................................................... 179

List of Contributors.................................................................................... 195

Index .......................................................................................................... 197

XI

�&&�� �

��&�'������()������ ��������� ���������������� ������� ������

The organization of the Round Table Archaeology and the Cru-sades as well as the public lecture entitled ‘The Crusades and their Critics’ fell within the framework of the organization of the historical and archaeological exhibition Crusades: Myth and Realities in Nicosia in 2005. All three events were part of the project Crossings: Move-ments of People and Movement of Cultures: Changes in the Mediter-ranean from Ancient to Modern Times funded by the European Union framework programme Culture 2000.

At the Round Table scholars from EU and non-EU countries gath-ered to examine recent archaeological investigations relating to the crusades to the Mediterranean between the twelfth and the fifteenth centuries. The public lecture presented a clear picture of the crusading movement in an understandable and popular way. The publication of the lecture and the papers presented at the Round Table in one volume will provide the reader with a book on one of the most fascinating and important episodes in European history and our common European background.

I wish to thank both the editors, Professor Peter Edbury and Profes-sor Sophia Kalopissi-Verti, as well as the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Cyprus, the Bank of Cyprus and the Cyprus Tourism Organization for their support.

XIII

�������������� ������� ��

�������������������� ������������������������������

Crossings: Movements of People and Movement of Cultures: Changes in the Mediterranean from Ancient to Modern Times is a three-year project funded by the European Union framework pro-gramme Culture 2000. The project started in 2004 with the organiza-tion of the historical and archaeological exhibition ‘Crusades: Myth and Realities’ with educational programmes in all four countries that hosted the exhibition (Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Malta), a public lec-ture on ‘Crusades and their Critics’ and a Round Table on ‘Archae-ology and the Crusades’. Then it continued with the organization of the Mediterranean Crossroads Conference in Athens, May 2005 and it reached its final stage of activities with the organization of the con-temporary art exhibition ‘Crossings’ in Malta, June 2006. These activi-ties aimed and achieved, to a great extent, the objective set out in the proposal of the project, which was the establishment, promotion, and maintenance of a cultural dialogue and the advancement of mutual knowledge and understanding of the cultural diversity and common heritage of Mediterranean peoples.

From the very beginning, the project events were conceived to be both academic and seriously popular in appeal. The focus of the Round Table was on recent archaeological discoveries that shed light on movements of people, the transmission of culture and of the interaction of art at the time of the Crusades. Eleven scholars from various univer-sities from EU and non-EU countries (including the USA) participated in the Round Table providing a complete picture of traditional and re-cent approaches on Crusades ideology and economy, religion, impact on art, settlement patterns and external influences on East and West. The public lecture, that was organized in parallel with the Round Ta-ble, presented a general overview of the crusading movement and the lands conquered by the crusaders.

XIV

The publication of the proceedings of the Round Table and the pub-lic lecture in one volume aims to demonstrate to an academic as well as to a wider public how elements of culture were transmitted from the East to the West and vice versa, and what changes in material culture occur as a result of this interaction.

I wish to thank all contributors to this volume as well as Dr Sophia Antoniadou for logistical and practical support. The Round Table, the public lecture and the proceedings of this volume were made possible with the financial support of the European Union framework pro-gramme Culture 2000.

XV

�%��.%�&�

On Tuesday 1 February 2005 there took place at the Casteliotissa in Nicosia a Round Table entitled Archaeology and the Crusades. It was timed to coincide with the exhibition Crusades: Myth and Realities which was then on display at the Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre before being taken to Greece, Italy and Malta later in that year. Both the Round Table and the exhibition were organized within the framework of the programme Crossings: Movements of People and Movement of Cultures - changes in the Mediterranean from Ancient to Modern Times, a project that had been initiated by the Pierides Foundation and supported by the European Union’s Culture 2000 programme.

The emphasis at the Round Table was on how recent archaeological work has shed light on the impact of the crusades on the lands around the eastern Mediterranean. There is no doubting the importance of the work currently in progress, and it is to be hoped that the papers, besides describing what has been achieved, will show the way ahead for simi-lar investigations elsewhere. This volume contains the seven papers given on that occasion, together with Dr Nicholas Coureas’s summing up of the day’s proceedings. Although not at all on the subject of the Round Table, the text of public lecture given at the Casteliotissa the previous evening by Professor Peter Edbury is also included.

It falls to the editors on their own behalf and on behalf of the other contributors to this volume to thank the many people who made the Round Table and its publication possible, not least Mr. Demetris Z. Pierides, the president of the Pierides Foundation and his staff, men-tioning in particular Mr. Yiannis Toumazis, the director of the Pierides Foundation and Project Manager, Dr Sophia Antoniadou and Mrs. Ma-rika Ioannou who undertook the organization of the round table.

Peter Edbury Sophia Kalopissi-Verti

XVII

�//��$0��0%� �

������������ ����������� �������������

���.B� .M�.��. ������� B� ������� M������� ��� ������

���.����. ������������ �������

���.’E�. ����������� ��������

����.��.���.��.��. ������� ��� �������� �� ����������� ��������� ������

����.X���.���.��. ������� ��� X��������� ’A����������� ���������

’E�.��.B����.M��. ’E������� ��������� B������� M������

’E�.���.B� .��. ’E������� ��������� B� ������� �������

N��� ���. N��� ������������

����.’A��.���. ��������������������������������������������

AA Archäologischer Anzeiger

AJA American Journal of Archaeology

ANSMN American Numismatic Society, Museum Notes

ArtB Art Bulletin

BAR British Archaeological Reports

BB Le Cartulaire du Chapitre du Saint-Sepulchre de Jérusalem, ed. G. Bresc-Bautier (Paris, 1984)

BCH Bulletin de correspondance hellénique

BMGS Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies

BSA Annual of the British School at Athens

BSl Byzantinoslavica

ByzF Byzantinische Forschungen

CahArch Cahiers archéologiques

CorsiRav Corsi di cultura sull’arte ravennate e bizantina

CRAI Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

XVIII

DOP Dumbarton Oaks Papers

IEJ Israel Exploration Journal

IstMitt Istanbuler Mitteilungen

JDAI Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts

JHS Journal of Hellenic Studies

JMedHist Journal of Medieval History

JÖB Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik

MonPiot Monuments et Mémoires publiés par l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres: Fondation Eugène Piot

NC Numismatic Chronicle

PL Patrologiae cursus completus, Series latina, ed. J.-P. Migne, 221 vols. (Paris 1844-80)

RDAC Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus

REB Revue des études byzantines

StMed Studi Medievali

StVen Studi Veneziani

TIB Tabula Imperii Byzantini, ed. H. Hunger (Vienna 1976 -)

ZDPV Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins

Relations between East and West 1

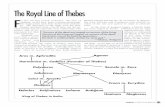

Relations between East and West in the Lordship of Athens and Thebes after 1204:

Archaeological and Artistic Evidence

��������������� ����

Abstract

This article focuses on the archaeological evidence for the Latin lords and Greek population in the Lordship of Athens and Thebes during the rule of the de la Roche family (1205-1311). The Latin fortifications on the Acropolis of Athens and the Kadmeia at Thebes, the towers and dwellings of the Frankish lords in the countryside and the few Byzantine churches and monasteries converted to Latin use are examined in conjunction with the clusters of houses for the local popula-tion and the numerous Greek Orthodox churches constructed and painted in this period. These remains bear witness to the separate co-existence of a Latin minor-ity of feudal lords and religious orders and a numerous Greek, mainly agrarian population. However, the fact that a Latin lord was buried in a Byzantine monas-tic church, the inclusion of portraits of western monks in the programme of the narthex of another Byzantine church, as well as sepulchral monuments in Athens showing a hybrid art point to a relationship between the two cultures evidently restricted on a high social and intellectual level.

Divergent themes of differentiation or fusion, confrontation or ac-

culturation are fundamental to this paper. What was the impact on mainland Greece of the encounter of two worlds when East met West in 1204, and how did the Byzantines and crusaders co-exist? Is there a clear distinction between conquerors and the conquered in habitation, religious practice, church construction, burial customs, sculpture and painting? This paper will examine these issues on the basis of the available archaeological and artistic evidence, focusing on the lordship of Athens and Thebes during the rule of the de la Roche family (1205-1311).

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 2

Figure 1. Athens. Plan of the Acropolis, ca. 1300. 1. Gates of the Rizokastron. 2. Enclosing wall and guardhouse of the entrance. 3. Gate and tower. 4. Gate at the second bastion. 5. Parthenon. 6. Erechtheion. 7. Cisterns. 8. Donjon. 9. Ruler’s residence. After T. Tanoulas, T�� ���������� ���� ���������

��������������������������Athens, 1997), drawing 62.

����������������� �&1�������

The Latin rulers occupied the Acropolis at Athens and the Kadmeia at Thebes and reinforced the existing system of fortifications. An en-ceinte, known as the Rizokastron, was built at the foot of the Acropolis (Fig. 1). Construction of this ring wall was once assigned to the elev-enth century.1 However, excavations conducted in 1985 on the south-ern slope of the Acropolis revealed a subterranean storage pithos be-neath the foundations of the Rizokastron. The ceramic finds in this pithos belong to the twelfth and the early years of the thirteenth cen-

1 I. Travlos, ���������������������� � (Athens, 1960), 156-62.

Relations between East and West 3

tury, thereby providing a clear terminus post quem for the construction of the Rizokastron shortly before the mid thirteenth century.2

Other defensive constructions include a bastion to protect the Klep-sydra spring on the northwestern slope of the Acropolis rock (ca. 1250)3 and a wall to protect the entrance gate. As Tasos Tanoulas has recently pointed out, the fortifications of the Athenian Acropolis shared certain features with the crusader castles of the Middle East, such as the concentric rings of fortified walls, the massive donjon and the successive bastions to protect the gate.4 In addition, the north wing of the Propylaea, where the Greek metropolitans resided in the twelfth century, was turned into a fortified residence for the ruler at the time of the de la Roche dukes. It comprised a cross-vaulted hall on the first floor, the private apartments of the ruler on the second floor, a single-aisled chapel and the donjon.5

In Thebes, Nicholas II de St Omer, one of the wealthiest and most prominent lords in Greece, lord of half of Thebes (1258-1294) and bailli of Achaia (1287-1289), constructed a castle including a palace on the Kadmeia in 1287. In 1311 both the castle and the palace were seized by the Catalans, who then demolished them in 1331.6 It has been

2 E. Makri, K. Tsakos and A. Babylopoulou-Charitonidou, ���� ������������

���������� ������������������������������������ �������������X�������.��� 14 (1987-1988): 329-63.

3 A. Parsons, “Klepsydra and the Paved Court of Pythion,” Hesperia 12 (1943): 251. 4 T. Tanoulas, “H ������� ��� A������� A����� �� ��� ���� �������� ��

�������� � �� ������ �� ��������� ��� M��� A��� � ��� �� K����,” in ����� ��� � �������� K���������� ���������, Nicosia 1996 (�icosia, 2001), 2: 13-83, with previous bibliography p. 15 n. 21; id., “The Athenian Acropolis as a cas-tle under Latin rule (1204-1458): Military and building technology,” in T��������� �� ��������������� E����, H������ 8 ����������� 1997, ��������� B�������� (Athens, 2000), 96-122; cf. id., ������������������� ���� �������� ��� �� M�������(Athens, 1997), 2 vols. and id., “The Propylaea and the western access of the Acropolis,” in R. Economakis (ed.), Acropolis Restoration. The CCAM Inter-ventions (London, 1994), 52-67.

5 Tanoulas, ������������, 291-309. 6 W. Miller, Essays on the Latin Orient (Cambridge, 1921, reprint Amsterdam,

1964), 76-77; P. Lock, The Franks in the Aegean, 1204-1500 (London and New York, 1995), 78-79, 94, 96, 102.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 4

Figure 2. Thebes. ‘Tower of St Omer’. Photo: courtesy of Ch. Koilakou.

convincingly argued by Charis Koilakou that a rectangular tower next to the Archaeological Museum, called the ‘Tower of St Omer’ and be-lieved to be part of his castle, was built rather earlier in the thirteenth century (Fig. 2).7 There are existing remains of a second tower, while a third was partially preserved until 1904. A destroyed monumental building which was uncovered at the centre of the Kadmeia has been identified as the palace of St Omer lords.8 According to the Chronicle of the Morea,9 Nicholas II de St Omer had built a palace large enough

7 J. Koder and F. Hild, Hellas und Thessalia (TIB 1) (Vienna, 1976), 270; S.

Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes (Princeton, N. J., 1985), 161; for the redat-ing Ch. Koilakou��������������������� �����������in�������� ��� ������������� ������� ������������������������������ (forthcoming). I wish to thank Charis Koilakou for showing me her unpublished manuscript and for her help with regard to slides and useful information.

8 Symeomoglou, The Topography of Thebes, 161-64, 229; Koilakou�� ������������������� �����������

9 ���X������ ���������, ed. P. Kalonaros (Athens, 1940), vv. 8080-92; H. Lurier, Crusaders as Conquerors: The Chronicle of Morea (New York, 1964), 298.

Relations between East and West 5

to house a king and had it decorated with frescoes that depicted the conquest of the Holy Land by the warriors of the First Crusade, thereby celebrating the crusading tradition.

Of special interest are the Frankish paintings preserved in the gate of the castle of Akronauplia, which belonged to the duchy of Athens at the time. Wulf Schaefer, who uncovered and published the frescoes, assigned them on the basis of the depicted coat of arms to Hugh de Brienne, husband of the widow of the duke of Athens, William de la Roche, and bailli of Athens (1291-1294), and he dated it to the year 1290/91.10 The depiction of saints, who represent the ideal of the war-rior (St George), the pilgrim (St James of Compostela and St Christo-pher) and the monk (St Anthony), conveys a clear message of crusader ideology. On the other hand, subjects common to both Frankish and Byzantine iconography, such as Christ in Glory and St George, indi-cate a fusion of eastern and western characteristics and a trend towards cultural osmosis.

The numerous towers constructed in central Greece mainly in the thirteenth and early fourteenth century were, as Peter Lock has con-vincingly argued, the residences of the minor Frankish feudal nobil-ity.11 Over twenty-five dwellings of Frankish vassals of the de la Roches have been thus located in Boeotia and Attica (Fig. 3). In addition, the Boeotia project, an archaeological field survey co-directed by John Bintliff and Anthony Snodgrass, was able to investigate the domestic

10 W. Schaefer, “Neue Untersuchungen über die Baugeschichte Nauplias im Mittel-

alter,” AA 76 (1961): 156-214; D.I. Pallas, �������������� ����� in Byzantium and Europe. First International Byzantine Conference. Delphi, 20-24 July 1985 (Athens, 1987), 32-34; S. Gerstel, “Art and Identity in the Medieval Morea,” in A. Laiou and R.P. Mottahedeh (eds.), The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World (Washington, D. C., 2000), 265-68; cf. S. Kalopissi-Verti, “The Impact of the Fourth Crusade on Monumental Painting of the Peloponnese and Eastern Central Greece up to the End of the Thirteenth Century,” in International Congress. The Fourth Cru-sade and its Consequences, Athens 9-12 March 2004 (forthcoming). In a very recent study M. Hirschbichler, “The Crusader Paintings in the Frankish Gate at Nauplion, Greece: A Historical Construct in the Latin Principality of the Morea,” Gesta 44/1 (2005): 13-30, dates the frescoes to between 1291 and 1311 on the basis of her identi-fication of the coats of arms which partly differs from that proposed by Schaefer.

11 P. Lock, “The Frankish Towers of Central Greece,” BSA 81 (1986): 101-23.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 6

Figure 3. Attica. Vravrona. Frankish tower. Photo: after H. Gini-Tsofopoulou, in ������������������������������������������������� (Athens, 2001), p. 182.

Relations between East and West 7

structure around one such tower in central Boeotia, when the level of Lake Hylike fell due to droughts in 1989 and 1990.12 Moreover, a Frankish rural dwelling of the thirteenth century that included a square tower has been excavated near Spata in Attica.13

While the residences of the rulers and the feudal lords are quite dis-tinct, is there any evidence for the settlements of the considerable local population? It is assumed that it was mainly the local Greek population that inhabited the many villages, hamlets and small rural sites, which flourished during the thirteenth century and which have been located by the Boeotia project.14 Systematic excavations in the early 1990s uncovered the remains of a late medieval village at Panakton on the borders between Attica and Boeotia. The domestic structures, a church, and the burials that surrounded it as well as small finds, such as ceramics, coins and agricultural tools, have recently been pub-lished.15 Although the excavated village has been dated to the four-teenth and fifteenth centuries, thus going beyond the chronological limits of this paper, it nevertheless offers a picture of life in a rural set-tlement at the time of Latin rule.

The dense habitation of the countryside is further attested by a letter written on 13 February 1209 in which Pope Innocent III confirmed to Bérard, Latin archbishop of Athens, the rights and properties of his archbishopric.16 The approximately forty villages (casalia) listed -

12 J. Bintliff, “The Frankish countryside in central Greece: The evidence from ar-

chaeological survey,” in P. Lock and G.D.R. Sanders (eds.), The Archaeology of Me-dieval Greece (Oxford, 1996), 6.

13 Its destruction at the end of the 13th / beginning of the 14th c. may be con-nected, on the basis of numismatic evidence, with the conquest of Athens by the Cata-lans in 1311. H. Gini-Tsofopoulou�� ���� � ������� ��� �� � ��������� ����������� ������ ��� �� � ����� ���� ������������ in� ���������� ������� ����

���������� �� ��������� ������ (Athens, 2001), 183. Other towers are pre-served in Vravrona and Daglas, cf. the toponym � ���������� ibid., 173-74, figs. 8-9, 182-85, figs. 1-2.

14 Bintliff, “The Frankish countryside,” 1-18. The Boeotia project focused its in-vestigation in SW Boeotia.

15 S.E.J. Gerstel, M. Munn et al., “A late medieval settlement at Panakton,” Hes-peria 72 (2003): 147-234.

16 PL 215: 1559-62; J. Koder, “Der Schutzbrief des Papstes Innozenz III. für die

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 8

twenty-five of which belonged to the archbishopric and roughly fifteen to the suffragan bishoprics - reveal a significant number of Greek set-tlements at the beginning of the thirteenth century, not all of which are identifiable; these settlements probably continued to exist at least until the time of the Catalan invasion.

Remains of houses from the Frankish period, and especially from the time of the de la Roche rulers, have been excavated in Thebes, both within and to the east of the Kadmeia.17 Excavations in Athens on the southern slope of the Acropolis rock, in the Ancient Agora and at the Olympieion18 have unearthed late-Byzantine houses, densely built, and overlying earlier dwellings, thus confirming the uninterrupted habita-tion of the same sites since the early Christian period. Inexpensive ma-terials, such as rubble, mortar and mud bricks for the upper parts of the wall, had been used for their construction. The floors were usually made of packed earth. In some cases there are indications of the exis-tence of a second floor.19 Numerous wells for the supply of water to the houses have been found in Athens, whereas in Thebes they are rare

Kirche Athens,” JÖB 26 (1977): 129-41.

17 Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes, 168, fig. 4,1; P. Armstrong, “Byzan-tine Thebes: excavations on the Kadmeia, 1980,” BSA 88 (1993): 295-335. For me-dieval Thebes, mostly relating to the Byzantine period, see also the article of A. Louvi-Kizi, “Thebes,” in A. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium. From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century (Washington, D. C., 2003) 2: 637-38.

18 I. Meliades���� ������� ��������������������������!.��. (1957): 23-4; A. Babylopoulou-Charitonidou, ��������� �������� ���� �� �� ����������� �� �� ����� �� �� � � ������� � ����� ��� ��������, 1955-1960,” ��!�����. 37 (1982) A: 127-32; T. Leslie Shear, “The Campaign of 1937,” Hesperia 7 (1938): 311-62; K.M. Setton, “The Archaeology of Medieval Athens,” in id., Athens in the Middle Ages (London, 1975) 1: 227-58; id., Catalan Domination of Athens (1311-1388) (London, 1975); I. Travlos, �� ���������� �� ��� ���� ��������� �����������!���� (1949): 42-49.

19 A big complex of 28-30, partly two-storey rooms grouped around a court was uncovered at the NW side of the Ancient Agora. It was erected, according to the coins found, at about the end of the 12th c. and abandoned probably before the Catalan inva-sion. It has been variously interpreted as shops, modest houses, one rich residence or as a building to house the monks and visitors of the church of St George (Theseion). T. Leslie Shear, “The Campaign of 1933,” Hesperia 4 (1935): 315; Setton, “The Ar-chaeology of Medieval Athens,” 245-48.

Relations between East and West 9

because natural water sources were abundant. Characteristic of dwell-ings both in the town and in the countryside are the storage pithoi, ei-ther built under the ground floor and plastered inside, used for storing cereals or water, or in the form of smaller jars made of clay, often cov-ered with thick sherds for greater strength, used for storing oil, wine and other goods.20

���������-����

At the very beginning of the thirteenth century, the Parthenon - the metropolitan church of the Byzantine archbishopric of Athens dedi-cated to the Panagia Atheniotissa - was turned into a Latin cathedral. The significant restoration works still in progress on the Acropolis have led to an important conclusion: the tower with the internal wind-ing staircase at the southwestern end of the Parthenon, previously thought to have been erected in the middle Byzantine period, was ac-tually built in the thirteenth century.21 This re-dating has in turn meant the re-dating of the paintings executed directly on the marble blocks of its north wall, which depict sinners in Hell as part of the scene of the Last Judgement.22 Since other painted fragments (the Virgin flanked by angels under an arch) on the east wall of the exonarthex of the Christian Parthenon, also belong to the same composition, the whole scene of the Last Judgement should be re-dated to the thirteenth century. Conse-quently, these paintings are evidently specimens of Frankish art in the converted Latin cathedral, where, in addition, earlier middle Byzantine paintings in the esonarthex were preserved as part of the decoration of the

20 For a description of the two types of pithoi Babylopoulou-Charitonidou,

������������������ 130-32; cf. Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes, 168; Louvi-Kizi, “Thebes,” 634.

21 A. Xyngopoulos, “������������������������������������������(1960): 1-16; M. Korres, �������������������������������������������������� (Athens, 1994), 162-99; id., “Recent discoveries on the Acropolis,” in E. Economakis (ed.), Acropolis Restoration. The CCAM Interventions (London, 1994), 177.

22 ��������� ��������������������������������������������� (1920): 36-53; id., “�������������������� ������� (1960): 12-13; A. Cutler, “The Christian Wall Paintings in the Parthenon. Interpreting a Lost Monument,” �������������������

17 (1993-1994): 171-80.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 10

Latin church.23 Further evidence for the Latin presence is provided by a monumental Gothic inscription on the east wall of the outer narthex, which has not been studied to date, and by several early fifteenth-century Latin inscriptions on the columns, mostly epitaphs of clerics.24

Another very important example of the transformation of an Ortho-dox church into one following the Latin rite is the katholikon of the Daphni Monastery.25 It was ceded by the de la Roches to the Cistercian monks of the abbey of Bellevaux, who rebuilt the twelfth-century ex-onarthex, partly demolished by earthquakes, and replaced the round arches of the facade by pointed ones (Fig. 4). The Cistercians also trans-formed the crypt under the inner narthex into a funerary chapel for the de la Roche dukes and their families. Guy I (d. 1263), Guy II (d. 1308) and Walter de Brienne (d. 1311) were buried in the crypt. The names of a few of the Latin abbots of the thirteenth century are known, and the seal of an unidentified Cistercian abbot has also been found.26

In Thebes the church of Hagia Photeine, the katholikon of a monas-tery outside the walls, was ceded to the Knights Templar and renamed Santa Lucia.27 There is, however, no archaeological evidence for its

23 The Last Judgement on the east wall of the outer narthex covered an earlier

layer of paintings, Xyngopoulos, “���������������������� -15, fig. 10. 24 Korres, ������������, 152, fig. 18; A.K. Orlandos and A. Branouses, T�

������������������ � � (Athens, 1973), 177-80, nos. 223-26. On the alterations of the church of St George (Theseion) in the 13th c., A. Frantz, “From Paganism to Christianity in the Temples of Athens,” DOP 19 (1965): 202-05.

25 On the monastery, G. Millet, Le monastère de Daphni, Histoire, Architecture, Mosaiques (Paris, 1899); A.K. Orlandos, ������� �������� � �� � � � ���� ��������!���"�� ����� ���������� 69-73; Ch. B�uras, “The Daphni Monastic Complex Reconsidered,” in I. �ev�enko and I. Hutter (eds.), Studies in Honour of Cyril Mango presented on April 14, 1998 (Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1998), 1-14. On the exonarthex E.G. Stikas, ��������� ���� ������������ ���� � � ������� �������������� ��� �� �� ��� �������������������!���. 3 (1962-1963): 25-43; B. Kitsiki Panagopoulos, Cistercian and Mendicant Monasteries in Medieval Greece (Chicago and London, 1979), 56-62.

26 Millet, Le monastère de Daphni, 38, 40; A.K. Orlandos���!��������������������� ��������!������ 9 (1924-25): 192.

27 The church, now restored, has a free-cross plan and can be dated to the 12th c., Ch. Bouras and L. Bouras���������� � ��������������� ������ � (Athens, 2002), 149-51. In earlier bibliography the church has been dated to the 10th c., A.K. Orlandos����������

Relations between East and West 11

Figure 4. The Monastery of Daphni. View of the narthex as rebuilt by the Cistercians. Photo: after E. Stikas, «����������� ���������� ��� ���������� ��� ����������������������������������������� 3 (1962-1963): pl. 1.2.

conversion into a Latin church. Furthermore, the church of Panagia Lontzia (from loggia) was used as the cathedral church of the Latins. Today, completely restored and used as the metropolitan church of Thebes, it preserves only two western-styled seated lions on the base of the episcopal throne that recall its Frankish period.28 In addition, a pair of iron tongs / seal with long grips used to bake and stamp the

!��� �� �� ����� �����!���"�� ����� � (1939-40): 144-47; Koder-Hild, Hellas und Thessalia (as note 7 above), 240; Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes, 167, 281. On a church in Thebes with a phase of paintings that can be dated to about the end of the 13th / beginning of the 14th c., see Ch. Koilakou, ���� �� ������������� �� ���������������������� in V. Aravantinos (ed.), #������ ��� ������������� ������� �$ ��������

��������������������.�������������� (Athens, 2000), 1: 1021-24. 28 Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes, 296.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 12

Figure 5. Athens. Byzantine and Christian Museum. Iron tongs / seal for stamping the Host. From Thebes. Photo: courstesy of Ch. Koilakou.

Host (Fig. 5) and a small pair of bronze tongs, probably used to dis-pense the Host to the congregation, which were recently unearthed by Charis Koilakou near the cathedral, are unique finds testifying to the practice of the Latin rite in Thebes.29

Of special interest is the church founded by the knight Anthony le Flamenc in Boeotian Karditsa, the ancient Akraiphnion,30 which is where his landed property probably lay. What is significant is that a Latin lord commissioned the construction of a church following a Byzantine architectural type (a cross-in-square church of the complex four-columned type) using local craftsmen and building techniques. The church, which was meant to house the lord’s tomb, was dedicated

29 Ch. Koilakou�� ����� ������������������� �� �����������������

in ��!���������� ���� ���� �����! ��� � ������������ � ����� ��� ��"� �� ����! ������������� � (Athens, 2004), 234-37.

30 On the inscription, W. Miller, “The Frankish Inscription at Karditza,” JHS 29 (1909): 198-201 and reprinted in id., Essays in the Latin Orient (Cambridge, 1921), 132-34; id��� ������������ �������� ��� � � ������� ���"�������������� 20 (1926): 380. On the church, P. Lazarides� ��!�����. 19 (1964) B2: 208-10; 21 (1966) B1: 211-13; 22 (1967) B1: 259; Ch. Koilakou����!�����. 42 (1987) B1: 116-17.

Relations between East and West 13

to St George, a saint highly venerated both by the Byzantines and the crusaders. The church served as the katholikon of a monastery, which, as testified by the inscription, was inhabited by Greek monks.31

Several toponyms and names of churches, such as �������� ����, ������������� etc., reflect the Frankish use of churches, especially in Attica, but there is no corroborative archaeological evidence for it.32

Four abbeys (abbatias) and 17 monasteries (monasteria) are re-corded in Pope Innocent III’s letter of 1209 as being under the jurisdic-tion of the Latin archbishop of Athens.33 Only some of them have been identified. The fact that these monasteries are listed in the letter does not necessarily mean that they were compelled to follow the Latin rite. There is evidence, on the contrary, that Greek monastic communities were allowed to function under the papal auspices, as for example in the case of the monastery of Hosios Meletios, to which all the privi-leges of a Greek-rite monastery were confirmed by Pope Honorius III in 1218 and Gregory IX in 1236.34 Furthermore, three inscriptions pro-vide evidence for the activity of Greek monks belonging to the Monas-tery of Hagios Ioannes Kynegos ton Philosophon in Attica during the thirteenth century.35

31 There is evidence that Venetian landlords in Crete sponsored Orthodox

churches in the villages that belonged to them, Ch. Maltezou�� ���� � ���������� ���� �����"��������� ������ � �����������������!.��. 21 (2000): 14.

32 On Frangokklesia at Chalandri and Penteli and on Frangomonastero at Kaisa-riane, A. Orlandos, ����� ��� ��� ������� ��� �� ����� (Athens, 1933), 3: 177, 194; R. Janin, Les églises et les monastères des grands centres byzantins (Paris, 1975), 338; Koder and Hild, Hellas und Thessalia (as note 7 above), 240. On recent excavations at Frangokklesia, Chalandri, ������������� ��������������� �������

������������������������������������������� ������������������������! ������� �"-#$� ����������� #$$%�� #$� On Frangokklesia in Salamis, D.I. Pallas������ � ���� ������ ������������!.��. (1987): 39-40; cf. Gini-Tsofopoulou, ����� ������” (as note 13 above), 184: �������!��������!���� etc.

33 PL 215, 1559-62; Janin, Les églises, 324-27, 298ff.; Koder, “Der Schutzbrief,” (as note 16 above), 130-32, 140-41 (with previous bibliography).

34���&��� utu, Acta Honorii III et Gregorii IX (Città del Vaticano, 1950), 66ff. (nos.

42, 43), 291 (no. 216); cf. A.K. Orlandos, “� �� ��� ����� M� ����� ��� �� ���� ����� �����,” ���.B� .M�.��. 5 (1939-40): 34-118, esp. 41; Koder and Hild, Hel-las und Thessalia, 217-18; Lock, The Franks in the Aegean (as note 6 above), 226-27.

35 Orlandos, E���������, 170-75; Janin, Les églises, 332; Koder and Hild, Hellas

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 14

Figure 6. Athens. Byzantine and Christian Museum. Dome of Spelia Penteles: Proph-ets. Photo: R. Andreadi, Photographic Archive of the Benaki Museum.

In addition, a large number of Greek Orthodox painted churches dating to the thirteenth century still survives in Boeotia and especially in Attica. A stylistic unity within groups of paintings attributed to the first half of that century allows the activity of workshops serving the needs of the lo-cal population both in town and in the countryside to be traced.36

Inscriptions date two of the churches displaying a common group of paintings characterised by simplicity, linearity and stylisation: St Peter at Kalyvia Kouvara is dated to 1232/33 and Spelia Penteles (Fig. 6) to

und Thessalia, 186-97; M. Sklavou-Mavr�idi, ����� ��� B� ������� M������ A����� (Athens, 1999), nos. 257, 284.

36 On local workshops, M. Panayotidi, “Village Painting and the Question of Lo-cal ‘Workshops’,” in J. Lefort, C. Morrisson and J.-P. Sodini (eds.), Les villages dans l’Empire byzantin (IVe - XVe si�������� !�"��#$$��������#�#��%"&��#$�� For a thorough discussion of Greek and Latin mural paintings in the Lordship of Athens, see M. Hirschbichler, “Monuments of a Syncretic Society: Wall Painting in the Latin Lordship of Athens (1204-1311)” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, Col-lege Park, 2005); cf. Kalopissi-Verti, “The Impact” (as note 10 above).

Relations between East and West 15

1233/34.37 The more important of the two churches is that of St Peter, not only because it preserves its iconographical programme almost in-tact, both in the nave and in the narthex, but also because it was spon-sored by a significant figure in the Greek ecclesiastical hierarchy, Bishop Ignatios, proedros of the bishopric of the islands of Thermiai (Kythnos) and Kea. The dedication to SS. Peter and Paul, the emphasis given to their portraits in several scenes, as well as the equal mention of both in the dedicatory inscription stress the equivalent significance accorded the two saints, who represent the Latin and the Orthodox Church respectively. Moreover, the effigy of Michael Choniates (d. ca. 1222) (Fig. 7), portrayed in both these churches some ten years after his death, reveals the sponsors’ intention to pay special honour to the last Orthodox metropolitan of Athens before the Frankish conquest.

The same workshop is represented in churches found within Ath-ens. The figures preserved in the church of St Marina (first layer) share stylistic features with the paintings in St Peter’s church at Kalyvia Kouvara in the rendering of the eyes, the contours of the face, the line-arity of the hair.38 The same linear rendering is encountered in another Athenian church, St John the Theologian in the Plaka quarter, the iconographical programme of which is the only one within this group of churches that reveals a divergence from the standard iconographical layout of an Orthodox church.39 The most important deviation consists in the representation of St George on horseback in the vault of the bema

37 N. Coumbaraki-Pansélinou, Saint-Pierre de Kalyvia-Kouvara et la chapelle de

la Vierge de Mérenta. Deux monuments du XIIIe siècle en Attique (Thessalonike, 1976); ead., “����� ������ K� ���� K������ A������,” ����.X���.���.��. 14 (1987-1988): 173-88; D. Mouriki, “O� �������� ����������� ��� ��� ��� ��� ���� ��,” ����.X���.���.��. 7 (1973-1974): 79-119.

38 Ch. Koilakou, ���.����. 36 (1981) B1: 79-80; 37 (1982) B1: 75; 39 (1984) B1: 63; 41 (1986) B1: 22-23; N. Chatzidaki, “������� ��� ����������� ���� �������� ��� ����������� ��� ����� ��� A����,” in Ch. Bouras, M. Sakel-lariou et al. (eds.), �������� ���� ����K�����E����� ����������� ��������� ��X. - � � ��X.) (Athens, 2000), 252-54; N. Panselinou, B� ������� A���� (Athens, 2004), 61, pls. 26-27.

39 H. Kounoupiotou-Manolessou�� ������ ��� ������������������� ������������!�� ���. 8 (1975): 140-51; Chatzidaki, �#���"��������������������� 250-52; Panselinou, ��"� �� ��� �, 60-61, pls. 24-25.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 16

Figure 7. Attica. Kalyvia Kouvara. Church of St Peter. Sanctuary: Michael Choni-ates. Photo: author.

and on the north wall of the prothesis. The depiction of warrior saints in the sanctuary is not unknown in churches in Greece under Frankish occupation, and it reflects the significance of the cult of military saints during periods of conflict. The military saint on

Relations between East and West 17

horseback in the church of St John the Theologian has parallels with crusader icons.40

Shortly before the mid-thirteenth century an Athenian painter, John, is mentioned in the dedicatory inscription of the church of Hagia Triada at Kranidi in the Argolid (1244), which at that time belonged to the de la Roche lords of Athens. Not without pride, the place of his origin is mentioned in the inscription:� ��� ������������ � , from the great city of Athens. On stylistic grounds the same painter is attested to have worked in the church of St John Kalyvitis at Psachna on the island of Euboea (1245),41 thus revealing the workshop’s range of activity.

The second half of the thirteenth century is very rich in painted churches both in Boeotia and in Attica.42 Most of the frescoes repre-sent a provincial tendency in which retrospective and modern stylistic features are combined. The assimilation of the progressive characteris-tics range from a relatively high degree, as seen in the wall paintings in the crypt of St Nicholas at Kampia in Boeotia, to a lesser one shown in murals of a more naive character, such as the frescoes in the church of the Taxiarches in Markopoulo, both dated to around the end of the thir-

40 Mounted warrior saints occur in the sanctuary of two 13th-century churches on

the island of Naxos, see A. Mitsani, ���� ��������������������������"��������� ���� ��� �����������������!���� 21 (2000): 97-98. On the representation of equestrian saints in the 13th c., Gerstel, “Art and Identity,” (as note 10 above), 269-73. On parallels with crusader icons, K. Weitzmann, “Icon Painting in the Crusader King-dom,” DOP 20 (1966): 67-74, figs. 46, 48-50; L.-A. Hunt, “A woman’s prayer to St. Sergios in Latin Syria: Interpreting a Thirteenth-Century Icon at Mount Sinai,” BMGS 15 (1991): 96-145, reprinted in ead., Byzantium, Eastern Christendom and Islam. Art at the Crossroads of the Medieval Mediterranean, vol. 2 (London, 2000), no. XIV.

41 S. Kalopissi-Verti, Die Kirche der Hagia Triada bei Kranidi in der Argolis (1244) (Munich, 1975); M. Emmanuel, “Die Fresken der Kirche des Hosios Ioannes Kalybites auf Euboia,” BSl 52 (1991): 136-44 (with previous bibliography).

42 On the painted churches in Greece in the second half of the 13th c., S. Kalopis-si-Verti, “Tendenze stilistiche della pittura monumentale in Grecia durante il XIII secolo,” CorsiRav XIII (1984): 232-51; ead., ���������� �������������������������$$���� ����"�������� ����������������in����� �� ���� ��� ��

���������! ���� (Athens, 1999), 63-90.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 18

teenth century.43 In this last category Omorphi Ekklesia in Aigina should be mentioned, dated to 1289, where certain iconographical fea-tures have been recently associated with crusader art.44

By far the most distinguished monument from the turn of the four-teenth century is the monastic church of Omorphi Ekklesia at Galatsi in Athens.45 From the architectural point of view, the church follows the Byzantine cross-in-square type (distyle-type) and Byzantine build-ing techniques, with the exception of the ribbed cross-vaults of the chapel, a typical feature of Gothic architecture. The entire building, including nave, chapel and narthex, earlier thought to belong to the twelfth century, has been recently redated to the late thirteenth cen-tury.46 The iconographical layout of the main church lays emphasis on the Christological cycle in accordance with the Orthodox church pro-gramme, whereas figures of monastic and military saints prevail in the lower zone. Peter, depicted as a central figure in the scene of the Transfiguration, deviating from his standard position at the lower left-hand corner, has been interpreted as a move towards the Latin Church which is, however, compensated by the equal emphasis on Peter and Paul who are represented facing each other on the north and south walls respectively (Fig. 8).47

43 M. Panayotidi�� ���� ����������� ��� ������ ���������� ��������� ����

����������������� in Actes du XVe Congrès International d’Etudes Byzantines, Athènes 1976, II, Art et Archéologie (Athens, 1981), 597-622; M. Aspra-Vardavaki������ ���� �� �� ����������� ���� �� ������ ��� ����������� ��������������!�����' (1975-1976): 199-227.

44 G. Sotiriou, ��������������������( �� ������������"���. 2 (1925): 243-76; V. Foskolou, ���$������������������ �(��� ����(unpublished Ph.D. disserta-tion, University of Athens, 2000); Ch. Pennas, ����"� �� ����� � (Athens, 2004), 20-28.

45 A. Vassilaki-Karakatsani��� ����!����%�����������%�������������� �

�� � (Athens, 1971). 46 S. Mamaloukos, “Architectural Trends in Central Greece around the Year

1300,” in International Scientific Forum Banjska Monastery and King Milutin Era, Banjska – Kosovska Mitrovica 22-25 September 2005 (forthcoming).

47 Vassilaki-Karakatsani��� ����!����%�����������%����������, 32, 38-40.

Relations between East and West 19

Figure 8. Athens. Omorphi Ekklesia at Galatsi. Naos: SS. Peter and Paul. Photo: after A. Vasilaki-Karakatsani, O � ������������� ���� ����������������

��� ��������Athens, 1971), pl. 16.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 20

Of special interest is the iconography of the narthex. Here, besides the Cistercian monk depicted on the eastern blind arch of the north compartment48 three further figures were recently uncovered on the west wall on either side of the west door and on the south jamb of the east door leading to the naos (Figs. 9, 10).49 Although seriously dam-aged, tonsure, garbs and the gospel book in their hands leave no doubt that they are Latin monastic saints who for the moment cannot be iden-tified.50 The depiction of Latin saints in an Orthodox church is rare. Isolated figures of western saints - St Francis and St Bartholomew - are incorporated into the programme of Orthodox churches in Ve-netian-ruled Crete.51 However, the inclusion of several western saints in an Orthodox church in the Frankish-held areas of Greece is thus far unique52 and indicates a measure of accommodation with the Latin Church.

In the south chapel three scenes - the Anapeson, Last Supper and Abraham’s Hospitality - allude to the Eucharist, whereas the composi-tion of the Commissioning of the Apostles and the full-length figures of the apostles holding the Gospel emphasize their missionary role.53 Evangelical preaching and the mystery of the Eucharist combined will lead to salvation. Is the context of the programme in this chapel

48 Ibid., 17-18. 49 I wish to thank Charis Koilakou for the permission to publish the photos and for

facilitating the study of the monument. 50 The serious damage, especially on the faces, may point to a damnatio memoriae

at a later time. 51 K. Lassithiotakis, ��� ����� !��������� ��� ������� ���� �� �������� in�

������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� 1976 (Ath-ens, 1981), 2: 146-54; M. Vassilakis-Mavrakakis, “Western Influences on the Four-teenth Century Art of Crete,” in XVI. Internationaler Byzantinistenkongress, Wien 1981, Akten, II. Teil, 5. Bd. = JÖB 32/5 (1982): 301-11.

52 Cf. a Sinai icon with the Deesis on the top and five saints in the lower zone (an Orthodox prelate and four monks in Western garment) which was recently attributed to a Cypriot workshop of the fourteenth century, A. Drandaki, in Pilgrimage to Sinai, exhibition catalogue, Benaki Museum 20 July - 26 September (Athens, 2004), 41 and no. 27 (J. Cotsonis).

53 Vassilaki-Karakatsani, � � ���!����%��� ��� �����%����������, 60-61, 65-68.

Relations between East and West 21

Figure 9. Athens. Omorphi Ekklesia at Galatsi. Narthex, west wall: Latin monk. Photo: courtesy of Ch. Koilakou.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 22

Figure 10. Athens. Omorphi Ekklesia at Galatsi. Narthex, west wall: Latin monk. Photo: courtesy of Ch. Koilakou.

Relations between East and West 23

an Orthodox equivalent to the missionary ideology of the western reli-gious orders, especially of the Mendicants who during the thirteenth century founded convents in Constantinople, the Near East and the Latin-ruled Greek provinces of Byzantium?54 Or could the sophisti-cated programme of the chapel accentuating evangelical preaching in combination with the inclusion of western monks in the narthex reflect a sympathy towards the precepts of the Dominicans or Franciscans whose preaching is known to have influenced scholarly circles in Byzantium in the thirteenth century and more especially in the four-teenth and fifteenth centuries?55 The profile and identity of the un-known erudite patron(s), who were well aware of the theological con-troversies of their time and wished to follow a policy of rapprochement with the Latin Church by including western monks of different orders in the narthex, as well as the chronological relation between fresco decoration of the main church, the chapel and the narthex are issues that need further investigation. Additionally, it should be noted that in keeping with the sophisticated programme, the high stylistic quality of the frescoes conforms to the modern tendencies of the great artistic centres of Byzantium.

54 On the history of the Mendicant orders, A. Hinnebusch, The History of the Do-

minican Order, 2 vols. (New York, 1973); id., The Dominicans: A Short History (Dublin, 1985); J.R.H. Moorman, A History of the Franciscan Order from its Origins to the Year 1517 (Oxford, 1968, reprint Chicago, 1988); C. Maier, Preaching the Crusades: Mendicant Friars and the Cross in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge, 1994); on their activities in the East, C.H. Lawrence, The Friars (London and New York, 1994), 65-88; Lock, The Franks in the Aegean, 230-33; C. Delacroix-Besnier, Les Dominicains et la chrétienté grecque aux XIVe et XVe siècles (Rome, 1997); A. Derbes and A. Neff, “Italy, the Mendicant Orders, and the Byzantine Sphere,” in H.C. Evans (ed.), Byzantium. Faith and Power (1261-1557), exhibition catalogue, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 2004), 449-61.

55 R.-J. Loenertz. “Les dominicains byzantins Théodore et André Chrysobergès et les négotiations pour l’union des églises grecque et latine de 1415 à 1430,” reprinted in Byzantina et Francograeca (Rome, 1978), 77-130; M.-H. Congourdeau, “Frère Simon le Constantinopolitain, O.P. (1235?-1325?),” REB 45 (1987): 165-74; ead., “Note sur les Dominicains de Constantinople au début du 14e siècle,” REB 45 (1987): 175-81; Delacroix-Besnier, Les Dominicains, 185-200. On the activities of the Do-minicans in Southern Greece, Delacroix-Besnier, Les Dominicains, 5-7, 41, 445 and passim.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 24

Figure 11. Monastery of Daphni. Sarcophagus of Guy II de la Roche (?), detail. Photo: courtesy of H. Gini-Tsofopoulou.

/�����������'��

The Frankish tombs that have been preserved belong to the upper class. The de la Roche dukes and their families used, or rather re-used, ancient sarcophagi as attested in Daphni, which they had chosen as their burial place. Most interesting, as Eric Ivison has observed, is a sarcophagus from the crypt, made of Hymettian marble, and with a relief decoration on one of its long sides, which has been associated with Guy II who was buried there in 1308 (Fig. 11).56 A Latin cross on steps under a round arch supported by two columns repeats a wide

56 W. Miller, The Latins in the Levant (London, 1908), 219; E.A. Ivison, “Latin

tomb monuments in the Levant 1204-1450,” in P. Lock and G.D.R. Sanders (eds.), The Archaeology in Medieval Greece (Oxford, 1996), 93, pl. 5. I wish to thank Eleni Gini Tsofopoulou for kindly providing me with a picture of the sarcophagus.

Relations between East and West 25

Figure 12. Athens. Byzantine and Christian Museum. Marble arch of a funerary monument. From the Acropolis. Photo: after M. Sklavou-Mavroidi, ������������ ���������������������������������������������

spread Byzantine theme. However, the two fleurs-de-lis - a typical French motif - between the cross arms on top, and the two confronted serpents below relate the sarcophagus decoration to western art.57

A marble Gothic trilobe arch surmounted by a larger pointed arch found on the Acropolis was probably the face of a tomb-niche, which included a sarcophagus.58 The deceased couple is represented on the outer arch (Fig. 12). The main inscription in Latin, the figure of the deceased man in western garb and gesture as well as the fact that the

57 For the use of the motif in French art but also on early Palaiologan coins see G.

Kiourtzian, “Un nouveau diptyche en ivoire de style byzantin,” Mélanges d’Antiquité tardive. Studiola in honorem Noël Duval 5 (2004): 233-44, esp. 242.

58 A. Xyngopoulos, �!��������� �� ��������� ���� �������!��%� (1931): 84-85, 87-90; A. Grabar, Sculptures byzantines du Moyen-Age II (XIe-XIVe siècle) (Paris, 1976), no. 127; Ivison, “Latin tomb monuments,” 93; Sklavou-Mavroidi��#����� (as note 35 above), no. 266.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 26

Figure 13. Athens. Byzantine and Christian Museum. Marble arch of a ciborium. From the Theseion Collection. Photo: after M. Sklavou-Mavroidi, ������������ ���������������������������������������������

arch was found on the Acropolis lead to the assumption that the tomb belonged to a Frankish noble. There are two interesting points with regard to this arch. First, besides the main inscription in Latin referring to the deceased (hic jace[nt…]), there are Greek letters reading [�'�����������(�' = of the ciborium. Second, analogous - western - stylistic features are encountered on three relief round arches belonging to a ciborium which once covered a sarcophagus (Fig. 13).59 Although the iconography of these reliefs is Byzantine60 - Nativity, prophets, De-scent into Hell - and the inscriptions are all in Greek, the style cannot be compared to Byzantine Palaiologan works. It has been convincingly

59 Xyngopoulos, �!��������� �� �� ������� 70-81; Grabar, Sculptures, no.

126; A. Liveri, Die byzantinischen Steinreliefs des 13. und 14. Jahrhunderts im grie-chischen Raum (Athens, 1996), nos. 41-43; Sklavou-Mavroidi, #�����, nos. 263-265. Arches with relief figures are not unknown in Palaiologan sepulchral monuments of Constantinople, Grabar, Sculptures, nos. 129, 133.

60 On the basis of the inscriptions the sculptured arches are considered as one of the earliest iconographical examples of the Christmas sticheron, Xyngopoulos, �!��������� �� ��������� 76; Grabar, Sculptures, 124-25. On the iconography of this subject, Ch. Stephan, Ein byzantinisches Bildensemble. Die Mosaiken und Fres-ken der Apostelkirche zu Thessaloniki (Baden-Baden, 1986), 227-31.

Relations between East and West 27

connected with the relief decoration of the church of the Paregoretissa in Arta, which in turn has been related to early thirteenth-century Apulian works.61 Linda Safran has, furthermore, plausibly linked the Paregoretissa reliefs with the church first built by Michael II (ca. 1230-1267) which was later incorporated into the building constructed by the despot Nikephoros I between 1294 and 1296.62 Thus a dating of both the reliefs at Arta and the arches of Athens to the mid-thirteenth century, or shortly before, seems reasonable.

There are other examples of this thirteenth-century hybrid relief art related to sepulchral monuments, such as the arch of an arcosolium with motifs borrowed from both traditions, Byzantine (birds) and Latin (fleurs-de-lis, bunches of tendrils) now in the Byzantine Museum at Athens.63

It is therefore clear that around the mid-thirteenth century there was a workshop in Athens producing sculpture in western style using mainly Byzantine but also western European iconography. The ethnic-ity of the craftsmen, whether Frankish or Greek, remains an open is-sue. The clientele, if we judge from the form of the funerary monu-ments and the inscriptions in Latin and in Greek, could have been both Franks and Byzantines, who seem to have shared the same icono-graphical motifs, stylistic features and burial customs. An artistic and cultural fusion of the two ethnicities on an upper class level is thus re-vealed as early as around the mid-thirteenth century. It should be

61 On the sculptures of Arta A.K. Orlandos, �������� ������ ��� �����

(Athens, 1963), 78-93 (Orlandos attributed the sculptures to Italian craftsmen, ibid., 93). On the connection of the sculptures of Athens with those of Arta, Ivison, “Latin tomb monuments,” 93; Liveri, Die byzantinischen Steinreliefs, 34. On the assignment of the sculptures of Arta to an Apulian workshop, L. Safran, “Exploring Artistic Links Between Epiros and Apulia in the Thirteenth Century: The Problem of Sculp-ture and Wall Painting,” in ������������� ������������������������������������������&������ �!���'�� 1990 (Arta, 1992), 455-74.

62 Safran, “Exploring Artistic Links,” 459; cf. L. Theis, “Die Architektur der Kirche der Panagia Paregoretissa,” in� ��������� ���� ��� ���������� ���� ������������� ��� �������� 475-93; ead., Die Architektur der Kirche der Panagia Paregoretissa in Arta / Epirus (Amsterdam, 1990).

63 Liveri, Die byzantinischen Steinreliefs, no. 45; Sklavou-Mavroidi, #�����, no. 292.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 28

noted, however, that alongside this hybrid art there was also the pro-duction of sculptural works in a purely Byzantine style, which contin-ued the middle-Byzantine tradition,64 as well as purely western pieces, such as the architectural members of porous stone found on the Acropolis, the small marble statues of the Virgin in the Byzantine Mu-seum and others.65

Even more striking is the example of the funerary monument of the knight Anthony le Flamenc who was buried in the katholikon of the Greek monastery of St George at Akraiphnion.66 The decoration of the arch (Fig. 14) with eschatological motifs, inspired by a Byzantine Last Judgement scene, followed a very widespread provincial stylistic trend in central and southern Greece around 1300. If the previous examples of the mid-thirteenth-century funerary monuments show an amalgama-tion of the two cultures, the case of this knight in Akraiphnion in 1311 points to an acculturation of the Latin patron to the Byzantine cultural milieu.

��������� ������'�

A good number of hoards67 deposited in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries as well as stray finds, mainly from Athens and Thebes,68 have produced hundreds of coins. Besides the petty currency (Frankish coppers) there are imported coins such as French deniers tournois

64 Sklavou-Mauroidi, #�����, nos. 285-91, 293. 65 Tanoulas������������������� �%���(�������� 23-33, figs. 22-50; “The

Athenian Acropolis,�� (both as note 4 above), 110, figs. 19-26; Sklavou-Mavroidi, #�����, nos. 276, 297, 300-01.

66 Above n. 30. 67 D.M. Metcalf, “Frankish petty currency from the Areopagus at Athens,” Hes-

peria 34 (1965): 203-23 (200 bronze coins of Guy I, ca. 1250-58); M. Galani-Krikou���!����������������������)�����*�����!������ 31 (1976) A: 325-50; ead., in D.I. Pallas, ����� ����������� �������������!���� 1987: 41-43.

68 M. Thompson, “Coins from the Roman through the Venetian period,” The Athenian Agora 2 (Princeton, N. J., 1954); P. Lazarides����!�������##� ����*� B1: 149-52; M. Galani-Krikou�� ������� �$���+��� � ����� ����������� ������������ �� ������ ����"��������������������*�� 113-37, esp. 126-37; ������ ��� ��������� ����� ���������������������������������������� ��������������� 12 (1998): 141-70, esp. 161-62.

Relations between East and West 29

Figure 14. Boeotia. Karditsa (Akraiphnion). Soffit of arch of the arcosolium of the knight Anthony le Flamenc: Angel. Photo: courtesy of Ch. Koilakou.

and Venetian grossi as well as local copies of the French deniers tour-nois, minted by the de la Roche dukes in Thebes, the princes of Achaia in Glarenza and others, and all these offer precious testimony concern-ing the circulation of coinage in the duchy.69

69 D.M. Metcalf, “The currency of Deniers Tournois in Frankish Greece,” BSA 55

(1960): 38-59; id., Coinage of the Crusades and the Latin East in the Ashmolean

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 30

Metallic objects, a basin for melting metals and other items found in a rescue excavation within the Kadmeia indicate the existence of a workshop producing metal wares.70 Among the finds, certain objects intended for Latin ecclesiastical use as mentioned above (pp. 11-12) and their close proximity to the metropolitan church of the Franks (Panagia Lontzia) indicate that this workshop was in operation during the Frankish domination.

As known from the sources, silk textiles continued to be manufac-tured in Thebes during Latin rule, although the very costly genuine murex purple dye, destined for the Byzantine emperors before 1204, ceased to be used and was replaced by cheaper colorants. Silk fabrics were now used by the local Frankish nobility and exported to Western Europe. Entrepreneurship and trade passed, as David Jacoby has pointed out, from the Greek archontes to the Venetians and Genoese.71 Archaeological investigations have brought to light a workshop for dyeing and manufacturing silk textiles west of the Kadmeia, close to a water supply in a place still called E�������, indicating that Jews were involved in silk manufacture. The workshop was in use from the be-

Museum Oxford (London, 1995), 240-86; M. Galani-Krikou, ��������� ��� � ������������ � ���� �grossi� ,&'� �� ,�'�������� � ���"���� ������ �������� � ��������������!�� ���� 21 (1988): 163-84. Most of the Athenian coins are from the reigns of William (1280-87) and Guy II (1287-1308) de la Roche, Metcalf, “The cur-rency of Deniers Tournois,” 53. I wish to thank Dr. Galani-Krikou for her help in bibliography and photographic material. On coinage in the Byzantine world after 1204 see recently C. Morrisson et P. Papadopoulou, “L’éclatement du monnayage dans le monde byzantin après 1204: apparence ou réalité?” Revue Française d’héraldique et de sigillographie 73-75 (2003-2005): 135-43 [1204 la quatrième croisade: de Blois à Constantinople et éclats d’empires, catalogue d’expositions sous la direction d’Jnès Villela-Petit].

70 Koilakou, ����� ���������������� 231-37. 71 D. Jacoby, “The Production of Silk Textiles in Latin Greece,” in ��! �� �����

�������� ��������� �� �������� ��������� �� (����������� � #� ������

������� ��� (Athens, 2000), 23-27; cf. id., “Silk in Western Byzantium before the Fourth crusade,” BZ 84/85 (1991-1992): 452-500, reprinted in id., Trade, commodi-ties and shipping in the Medieval Mediterranean (Aldershot, 1997), no. VII. For a discussion of economy in Latin Romania, see recently D. Jacoby, “Changing Eco-nomic Patterns in Latin Romania: The Impact of the West, ” in Laiou and Mottahedeh (eds.), The Crusades (as note 10 above), 197-233.

Relations between East and West 31

ginning of the eleventh to the end of the fourteenth century and reached its peak, according to the archaeological evidence, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.72

The ceramic finds have shown the impact of imports of fine ware from Italy as well as from other parts of Greece. At the same time local late-Byzantine pottery continued to be produced.73 Discarded and badly-fired pottery sherds as well as tripod stilts point to the existence of pottery workshops both in Athens - in the Roman Agora and on the south slope of the Acropolis74 - and in Thebes.75 However, no pottery kilns have been found.

To sum up, the Latin rulers lived in the two important strongholds of the Kadmeia in Thebes and the Acropolis in Athens, where they im-proved the fortifications and built their own residences. The lower feu-dal nobility lived scattered in the countryside where they erected tow-ers. The Latins turned the cathedrals, and certain other Orthodox churches and monasteries, into Latin-rite churches by effecting minor changes and accepting the Byzantine painted decoration, as at Daphni.

The Byzantine population continued to live in pre-existing or newly built houses in the towns and villages. They continued to worship in the existing churches and monasteries and constructed new ones. The large number of newly built and painted churches points to a prosperous

72 Koilakou, “���� ���������������� 226-29. 73 P. Armstrong, “Byzantine Thebes: Excavations at the Kadmeia, 1980,” BSA 88

(1993): 295-335; J. Vroom, After Antiquity. Ceramics and Society in the Aegean from the 7th to the 20th century A.C. A Case Study from Boeotia, Central Greece (Leiden, 2003), 64-69, 164-69; Ch. Koilakou����������������������������������������������” in ������������������������������������������-�������������� 2005 (unpublished).

74 Ph.D. Stavropoulos, “������� P������� A�������� ��������� 13 (1930-1931), Parartima: 3-5; A.K. Orlandos, “X��������� ������� ��� �������� ��� ������������ ���� P����������������������� 1964, Parartima: 16; P.G. Kalligas, ��������� 18 (1963) B1: 171. For pottery and other workshops in Middle-Byzantine Athens (soap works, tanneries, murex dyes), M. Kazanaki-Lappa, “Medieval Ath-ens,” in A. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium. From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century (Washington D. C., 2003), 2: 643-45.

75 Koilakou, ����� ���������������� 238.

Sophia Kalopissi-Verti 32

Figure 15. Attica. Kalyvia Kouvara. Church of St Peter: St Tryphon. Photo: author.

Relations between East and West 33

and active population, and at the same time it reveals a policy of reli-gious tolerance by the Frankish rulers. The numerous villages and hamlets and the great number of big storage pithoi uncovered in towns and in many locations in the countryside indicate a flourishing agrarian economy. This peasant society is also reflected in art, as for example in the depiction in the church of St George at Kalyvia Kouvara of the punishments in Hell for those who plough and harvest the fields of their neighbours,76 or in the predilection to represent saints considered as protectors of sheep, as in the church of St Peter at Kalyvia Kouvara (Fig. 15)77 In ecclesiastical art, from the iconographical and stylistic perspectives, the overwhelming majority of the Byzantines - with very few exceptions such as the patron of Omorphi Ekklesis at Galatsi, Athens - faithfully adhered to their religious and cultural traditions with minimal western influences.

Osmosis between Franks and Byzantines has been noted with re-gard to burial practices and taste in sculptural works. Although sam-ples of purely western art, especially in sculpture, have come to light, there are cases of Frankish patrons who seem to have been culturally assimilated and to have preferred Byzantine patterns of architecture and painting, as evident in Akraiphnion.

76 Mouriki, “An Unusual Representation,” 150, 161-64, pls. 89-90; S. Gerstel,

“The Sins of the Farmer: Illustrating Village Life (and Death) in Medieval Byzan-tium,” in I. Contreni and S. Casciani (eds.), World, Image, Number, Communication in the Middle Ages (Florence, 2002), 205-17.

77 Coumbaraki-Pansélinou, Saint-Pierre, 102-03, pls. 50, 52.

![Ο ελληνισμός μετά την άλωση του 1204 [The Greeks after the fall of Constantinople in 1204], in: Η Τέταρτη Σταυροφορία και ο ελληνικός](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/631a9bd9b41f9c8c6e0a4617/o-ellinismos-met-tin-losi-tou-1204-the-greeks-after.jpg)