factors affecting the satisfaction of bangladeshi medical tourists

Landscapes of desire: tourists, touts and sexual encounters at the World Heritage site of Thebes.

Transcript of Landscapes of desire: tourists, touts and sexual encounters at the World Heritage site of Thebes.

1 23

ArchaeologiesJournal of the World ArchaeologicalCongress ISSN 1555-8622Volume 9Number 3 Arch (2013) 9:398-426DOI 10.1007/s11759-013-9242-3

Landscapes of Desire: Tourists, Touts andSexual Encounters at the World HeritageSite of Thebes

Claudia Näser

Landscapes of Desire: Tourists, Touts and

Sexual Encounters at the World Heritage Site

of Thebes

Claudia Naser, Department of Egyptology and Northeast African

Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Humboldt-Universitat zu

Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany

E-mail: [email protected]

ABSTRACT________________________________________________________________

Cultural tourism capitalises on archaeological sites with World Heritage

status on a global scale. The encounters of visitors from all over the world

with local residents and other stakeholder groups, like local and

international entrepreneurs, set off complex processes of interaction in

which the physical and social space of the heritage site is negotiated,

shaped and consumed. In a case study from Luxor/Egypt, this paper

investigates a particular facet of these interactions, namely sexual

encounters between tourists and members of the local community. It

delineates the economic and social conditions of this phenomenon and

discusses the role it takes in the production, perception and use of the

World Heritage site of Thebes.________________________________________________________________

Resume: Partout dans le monde, le tourisme culturel capitalise sur les sites

archeologiques inscrits au patrimoine mondial. La rencontre des visiteurs

venus du monde entier avec les residents locaux et d’autres parties

prenantes, comme les entrepreneurs locaux et internationaux, genere des

processus d’interaction complexes au cours desquels l’espace physique et

social du site patrimonial se negocie, se modele et se consomme. Au travers

d’une etude du cas de Louxor, en Egypte, cet article se concentre sur une

facette particuliere de ces interactions : les relations sexuelles entre touristes

et membres de la communaute locale. Il decrit les conditions economiques

et sociales de ce phenomene, et discute de son role dans le

developpement, la perception et l’usage du site du patrimoine mondial de

Thebes.________________________________________________________________

Resumen: El turismo cultural saca provecho de los sitios arqueologicos con

estatus de Patrimonio de la Humanidad a escala global. Los encuentros de

los visitantes de todo el mundo con residentes locales y otros grupos de

RESEARCH

ARCHAEOLOGIES

Volume9Number

3December2013

398 © 2013 World Archaeological Congress

Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress (© 2013)

DOI 10.1007/s11759-013-9242-3

partes interesadas, como los emprendedores locales e internacionales,

activan procesos de interaccion complejos en los que el espacio fısico y

social del emplazamiento patrimonial es negociado, formado y consumido.

En un estudio de caso de Luxor (Egipto), el presente documento investiga

una faceta particular de estas interacciones, a saber, los encuentros sexuales

entre turistas y miembros de la comunidad local. Delinea las condiciones

economicas y sociales de este fenomeno y analiza el papel que desempena

en la produccion, percepcion y uso del emplazamiento Patrimonio de la

Humanidad de Tebas._______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

KEY WORDS

World Heritage, Tourist–local sexual encounters, Enclaving, Luxor (Egypt)_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Archaeological heritage spaces attract the interest and involvement of a

wide range of individuals and groups of stakeholders. Their interplay sets

off multiple processes of voicing, negotiating, mixing and interlinking cul-tural concepts and practices. These concepts and practices in turn shape

the trajectory of the archaeological heritage space. It was this intricate web

of interactions and the consequences they have for the production of the

physical and social space of the Theban Necropolis which I wanted to

explore when I embarked on the project ‘Archaeotopia’ in 2010.1

History has its own pace, and the 25th January 2011 revolution and its

aftermath not only interrupted fieldwork but also drastically changed con-

ditions at the study site. Questions about Egypt’s future and how develop-ments would impact local stakeholders’ lives came to the fore. While these

concerns, particularly with regard to the disruption of tourist flows, gov-

erned conversations on the ground, some things—at least superficially—

stayed the same. Among these were the general patterns of how local stake-

holders interacted with tourists and how these interactions shaped the per-

ception and the production of the site’s social and physical space. Setting

out to work on this subject, I was immediately drawn into a whirl of iden-

tifications and interactions myself, in which I occupied a marked positiondue to my gender, ethnicity and presumed economic status. As a ‘Western’

woman visiting Egypt, I was a target in one of the most prominent socio-

economic strategies of Egyptian men of the younger generation: namely,

getting involved in a sexual relationship with a ‘Western’ partner. While

walking on the streets of Luxor and through the foothills of the Theban

Landscapes of Desire 399

Necropolis, I was not allowed to escape this role even for a moment. Ini-

tially, I turned this experience into an object of investigation out of pure

self-preservation: taking this perspective allowed me to distance myself

from what happened to me, and it enabled me to twist some unpleasant

encounters into unthreatening, open and cheerful communicative situa-tions. Later, I realised that the phenomenon merged several aspects of my

own research interests and some issues which were repeatedly brought up

by my interview partners in the course of our conversations. Thus, I came

to study tourist–local sexual encounters and their repercussions on the

World Heritage site of Thebes.

I want to underline that while I have singled out this topic, it must nei-

ther be seen in isolation nor understood as a simple reproduction of super-

ordinate power relations characterising foreigner–local relationships inLuxor and wider Egypt. Of course, the phenomenon brings to attention all

of the problems inherent in our ‘Western’ appropriations of Egypt, ancient

and modern, in that they are ‘the result of exploitive and colonial histories,

and […] remain saturated with exploitive and colonial resonances’ (Kulick

1995:24, note 1). But—as will be argued throughout this paper—neither

do the repercussions of these histories determine foreigner–local sexual

relationships ‘in any simplistic or straightforward way’ (Donnan and

Magowan 2010:111; Kulick 1995:24, note 1), nor must these relationshipsbe reduced to representing those histories and the past and recent power

imbalances arising from them.

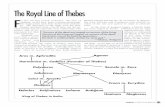

The World Heritage Site of Thebes

Luxor with its archaeological attractions was inscribed in the World Heritage

List with the official designation ‘Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis’ in 1979(http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/87). The chosen toponym ‘Thebes’ comes

from , which was the Ancient Greek name of a city that in Ancient Egyptian

was called Waset. The remains of this city lie under parts of the modern town

of Luxor, رصقألا , on the east bank of the Nile, approximately 500 km south of

Cairo. Its most prominent heritage sites are the Karnak and Luxor temples,

close to the Nile and connected by a 2.5-km-long corniche. The ‘Necropolis’

is an area of extensive burial grounds stretching over several kilometres on

the west bank of the Nile, opposite present-day Luxor. Its most prominentfeature is the Valley of the Kings, situated far away from the cultivation zone

in a wadi amid the desert mountains (Figure 1). Further attractions on the

west bank are the Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir al-Bahari, several New King-

dom mortuary temples along the edge of the cultivation zone and the so-

called ‘Tombs of the Nobles’, ie. the non-royal elite necropolis in the foothills

of the terminal desert escarpment. Since the 19th century and until very

400 CLAUDIA NASER

recently, the area of the ‘Tombs of the Nobles’ had been co-occupied by vari-

ous hamlets, usually subsumed under the name of the central village, al-Qur-

na (Tully and Hanna, this volume; van der Spek 2011). A series of relocation

acts between late 2006 and 2009 spelt the end to these agglomerations, with

the inhabitants being moved to purpose-built new villages outside the heri-tage zone and all but one of their old villages being destroyed.2 These reset-

tlements have received a wide critique (Tully and Hanna, this volume with

further references; van der Spek 2011). Already, in its 2007 report, the ICO-

MOS had commented disparagingly on the process: ‘As a result, little atten-

tion has been given as to how best to maintain the complex set of historic

layers which underlie the Thebes inscription on the List, and that indeed

many significant parts of the site are being needlessly discarded. […] In par-

ticular, the loss of Gurnah, whose residents have provided the bulk of theexcavation effort at Thebes from the 19th century forward, would involve

loss of a place of great importance within the original nomination’ (http://

whc.unesco.org/en/soc/1095). In the 2013 ‘State of Conservation’ report, pre-

pared by the UNESCO Secretariat and the advisory bodies to the World Her-

itage Committee, ‘demolitions in the villages of Gurna on the West Bank of

the Nile and transfer of the population’ are again quoted among the threats

to the site without further comment (http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/1892).

Figure 1. Information board with map of the main tourist attractions of Western

Thebes; in the background, the partly destroyed village of Qurnet Murai (photo Clau-

dia Naser, 2010)

Landscapes of Desire 401

As a major move in the attempt to re-design Western Thebes as an

‘open-air museum’, reserved for international tourists and ancient monu-

ments, these measures indeed had dramatic consequences for the face and

the space of the heritage site.3 What had been a lived-in environment is

now reduced to a deeply scarred and fragmented space which prioritisesremains of the Pharaonic past over all others at the expense of physically

removing testimonies of subsequent date, primarily those of the (sub)

recent past and the present. As a result, the Pharaonic component of the

site has been separated from all its later contexts and stripped of its mean-

ingful associations and links to the present. Physical and conceptual segre-

gation has thus been achieved to a terminal level, being irreversibly

inscribed onto the landscape. The places which had been occupied by the

houses of the villages are now open wounds, which cannot possibly beclosed, as there is no ‘ancient’ substance or meaning to fill them (cf. Weeks

in van der Spek 2011:XIX).

One of the negative consequences of the destruction of Qurna, raised by

the former inhabitants of the village itself, is that with their relocation they

lost easy access to the tourists to whom they sell souvenirs, tea and their

services as guides when visitors come to see the tombs (eg. van der Spek

2011:322–324, 343–345). This claim is at the centre of the rhetoric with

which the local population ties itself to the heritage site of Thebes. How-ever one does rate this argument, it is true that the Qurnawis not only

have to cope with the loss of their homes and the physical distance

between their new villages and their old workplaces but they must also

absorb the irrevocable loss of cultural capital that came from their unique

connection with the heritage space of ‘Ancient Thebes’ (cf. van der Spek

2011:343–345).

The Informal Employment Sector

Despite recent developments and all attempts to segregate tourists and local

communities, Luxor and the Theban Necropolis continue to be arenas for

multiple interactions between locals and visitors of all sorts. Informal

guides and vendors are an important group of actors in this context. These

are mostly younger men, between their late teens and mid-thirties, who

work in the environs of the heritage sights and in the streets frequented bytourists, selling souvenirs, advertising transportation, such as rides on a

caleche or a felucca, or offering their services as guides. The content and

boundaries of their businesses are fluid, which makes it difficult to give

them a proper name. Gamblin (2007:223–225) speaks of ‘khaltiya’, a term

which is, however, not commonly used. Many tourists call them ‘touts’. I

will stick to ‘informal guides and vendors’ on the understanding that I use

402 CLAUDIA NASER

this designation in the widest sense, encompassing the advertising and sell-

ing of all goods and services one can possibly think of. Investigating the

activities of the informal guides and vendors in the streets of Luxor is a

challenge. As Karl Anthony Schmid (2008) has noted, ethnographic stan-

dard procedures of data gathering are of limited use. Observation of, orparticipation in, concrete interaction situations is delicate, as it may curtail

the flow and in turn the success of the transaction. Schmid (2008:119)

underlines that ‘it is important to recognize that there are strong interests

at play in each relationship and that the ethnographer cannot insert him-

self or herself unobtrusively into the midst of these relationships’, especially

when transactions are of a sensitive nature or when timing is crucial to

forge a contact and establish further dealings. Likewise, the guides and ven-

dors will not, for example, readily disclose their earning capacities, lestthese data should reach the police or other representatives of the State.

Also, when earnings are low and supplemented by other sources of income,

a disclosure of such data might weaken the above-quoted argument that

access to tourists is their primary or sole basis of existence. Despite these

challenges, the informal guides and vendors have formed the subject of

several studies in recent years (Gamblin 2006, 2007; Schmid 2008; van der

Spek 2011). Embedded in larger-scale analyses of the dynamics of the

World Heritage site of Luxor and its prime stakeholders, investigationscentred on the demographic profile of the guides and the socio-economic

parameters of their business. In unison, the authors highlighted the mar-

ginal position and the difficult economic circumstances of this occupa-

tional group. The involved men and boys—seemingly, there are no women

in these roles—are locals from Luxor town and the west bank villages.

Most of them have a low level of formal education and depend totally or

at least in larger part on the informal labour market for their income.

Their workplace is the public space of the heritage site, and their strategiesare adapted to the specifics of this environment and the movements of

their potential clientele through it. Recent statistics are missing, but in

2009/10, Luxor’s archaeological sites were visited by over eight thousand

persons a day on average (Weeks in van der Spek 2011:XVII). In pursuit

of them, hundreds of guides and vendors roam the Corniche—the avenue

bordering the Nile which links the city’s major tourist attractions on the

east bank. On the west bank, sights are more dispersed (see Figure 1). The

Valley of the Kings is approached by a 3-km-long tarmac road leadingthrough a lonely desert wadi away from the cultivation. The other main

attractions stretch along a route of roughly 3.5 km which skirts the desert

edge. Package tourists traverse these distances by coach or minibus; back-

packers and other independent travellers may take a taxi, a bike or, more

rarely, hire a donkey, or even walk. Informal guides and vendors are

banned from the Valley of the Kings and the other major sights of the

Landscapes of Desire 403

Theban Necropolis. Instead, they concentrate on the minor sites and their

environs, to which access is less strictly regulated, giving them betterchances to approach potential clients, follow them around and strike a deal

(Figure 2).

When moving as a foreigner in these areas, or indeed in any other pub-

lic space in Luxor, one is inevitably faced with a constant flow of proposi-

tions by young men—many but by far not all of them informal guides.

These encounters constitute a primary experience of tourists in Luxor, and

they are eloquently described on many traveller sites and blogs.4 While

some visitors enjoy these contacts, many feel pestered. It is not withoutreason that Luxor has acquired the reputation of being the ‘hassle capital

of Egypt’ (Schmid 2008:107). Often, the approaches include more or less

explicitly phrased sexual offers. Given my clearly visible identities as female

and ‘Western’, I frequently found myself in this situation when venturing

into a public space. I usually tried to answer politely phrased propositions

and enquiries by stating that I was not a tourist, but an archaeologist

working in Luxor and as such not interested in the offers. I had used this

explanation many times when I first explored the Theban Necropolis formy PhD research in the late 1990s. Back then, many guides and vendors

would react to my statement by instantly switching the tone of the conver-

sation. After ascertaining my nationality, they would enquire about Ger-

man colleagues they knew, issue greetings or tell me who in their family

Figure 2. Tourists moving between the partly destroyed houses of the village of

Qurna on their way from the car park to the ‘Tombs of the Nobles’, with local guides

and vendors pursuing them (photo Claudia Naser, 2010)

404 CLAUDIA NASER

worked with the German archaeologists. By this, the guides would

acknowledge that we were part of a common social network which was

separate from tourist to local interactions, and this would preclude further

business-oriented approaches from their side, if I did not invite them. The

social control apparent in these earlier exchanges has clearly diminishedover the last 10 years. During my visits in 2010 and 2012, my explications

would only rarely trigger this switch in the conversation, more often they

would go unacknowledged, and on occasion they would evoke plainly hos-

tile reactions. In a rather wild rhetorical twist, some guides would ask why

I refused to talk to them and accuse me of being racist.5 To me, this reac-

tion at first seemed paradoxical, as insulting a potential client would cer-

tainly not further business. In hindsight, I understand these responses as

unchannelled outlets of frustration and attempts to reverse the power rela-tions which had become unacceptable for the guides upon my rejection

(cf. Schmid 2008:116–117). However, I also experienced other reactions,

which allowed me and the guides to part on friendly terms, with them

‘melting away’ in order to reappear at some distance pursuing the next

potential client a few minutes later.

When analysing the contact situations and the interactions in which I

participated during my fieldwork, which I observed or which were reported

to me by interview partners, two further observations struck me. The firstconcerns an element of ambiguity inherent in many of these encounters.

Often, guides would not set out with a specific offer, but with more gen-

eral enquiries relating to the nationality of the addressed, his or her name,

his or her impression of Egypt, etc. In this initial phase, it was often not

apparent what was actually offered or sought: services as a guide, a felucca

ride or a sexual relationship. I perceive this ambiguity as a deliberate strat-

egy on the part of the guides who try to first engage the potential client in

a communication, before deciding towards which end the dealings can bemost successfully developed, ie. what could be sold or which other benefits

could be gained. Ultimately, one result may lead to the other. The second

aspect is related to this ambiguity: like several interview partners, I felt that

a sexualised component resonated in many of these encounters. This sub-

text permeates the interactions between local men and ‘Western’ visitors,

male and female, in the heritage space of Luxor and Thebes, in very much

the same way as it does in tourist centres in Gambia, Kenya or some of

the countries in the Caribbean (see, eg. Donnan and Magowan 2010:93–127; Egger 2008; Herold et al. 2001; Kleiber and Wilke 1995; Pruitt and La-

Font 1995). As Deborah Pruitt and Suzanne LaFont (1995:426), quoting

Ben Henry, have remarked regarding Jamaica, the frequency with which

foreign women get involved with local men has led to ‘the sexualization of

routine encounters’ between the two groups. Today, it is impossible to tra-

verse the public space of Luxor without being frequently approached by

Landscapes of Desire 405

Egyptian men as a gendered and racialised individual, namely a non-Egyp-

tian, non-local woman. Perceptions of space and decisions on personal

movements are dictated by this experience. For example, I would avoid

some places like the Corniche, where I knew that guides clustered, or I

would try to cover these areas quickly. I would also try to circumnavigateapproaching guides in the hope that they might divert their attention to

other visitors. After sunset, male colleagues would usually offer to accom-

pany me when I wanted or needed to be out, and I would have to decide

whether I wanted to accept this offer or risk unpleasant encounters by

going alone.

Tourist–Local Sexual Encounters in Egypt and Beyond:More Than Putting a Name to Them

Sexual relationships between ‘Western’ tourists and members of their host

societies have been studied extensively in many destinations of the global

South. Particularly when involving ‘Western’ women, the phenomenon is

highly debated with regard to its conceptualisation, valuation and termi-

nology (Jeffreys 2003). What this interaction is called depends primarily on

how the intentions of the two partners and the power relations betweenthem are perceived and judged by the researcher. The central question is

whether—and to what degree—the women and the men involved in these

relationships are understood as perpetrators, victims or empowered agents.

The views on these points also determine whether such encounters are sub-

sumed under the heading of prostitution and aligned with male sex tour-

ism (eg. Sanchez Taylor 2006). In an effort to distance herself from this

categorising perspective, Jessica Jacobs (2010) in her study on Sinai speaks

of ‘ethnosexual encounters’, ‘romantic “sex tourism”’ and ‘romance tour-ism’. The latter term was coined in an influential paper by Deborah Pruitt

and Suzanne LaFont (1995) who analysed similar relationships in Jamaica.

Subsequently, their conceptualisation has been critiqued in relation to sev-

eral points (eg. Herold et al. 2001:979–980; O’Connell Davidson 1998:180–

188; Sanchez Taylor 2006). In a powerful rhetoric against belittling the

exploitive character of these relationships by emphasising their ‘romantic’

component, Jacqueline Sanchez Taylor (2006) has coined the term ‘tourist-

local sexual-economic exchange’. Beyond the academic debate, a numberof colloquial designations for such encounters and their agents have

emerged in different regional contexts. In other parts of northern Africa,

particularly in Tunisia, the term ‘bezness’ is widely used, having come to

prominence after the eponymously titled movie by Nouri Bouzid.6 In the

Middle East, such relationships and the involved partners are often referred

to as MMD—‘My Mohammed is different’—a topical statement which

406 CLAUDIA NASER

involved women make about their partners when confronted with the

potential risks and drawbacks of their relationships.7 While the term may

originally have held somewhat different connotations,8 its current use in

Egyptian contexts embraces all of the dimensions of ‘sexual-economic

exchanges’ surveyed in the following discussion.Tourist–local sexual encounters in Egypt have so far received little atten-

tion in the global discussion of the subject. Still, they are an integral com-

ponent of the local tourist world, as the studies of the beach-and-desert

holiday destinations on Sinai by Mustafa Abdalla (2007) and Jessica Jacobs

(2010) have shown. Both authors’ extensive qualitative analyses delineate

the specific conditions of the local version of this phenomenon. Quantita-

tive data, however, are hard to come by. Abdalla (2007:81) maintains that

tourist–local sexual encounters ‘can be observed on a large scale and arepracticed extensively’ in Dahab. He holds ‘global trends, economic hard-

ships in addition to social problems in Egypt’ liable for their emergence

and spread (Abdalla 2007:79). While he identifies ‘underprivileged young

men’ as the main actors of this practice (Abdalla 2007:passim, esp. 79),

Jacobs (2010:passim, esp. 76–77, 112–116) asserts that many of her inter-

viewees have a middle class background. This is in accordance with the

education level which Abdalla indicates for the men he talked to. Both, Ab-

dalla and Jacobs, not only highlight the economic benefits the men derivefrom their relationships but they also underline that these benefits are not

the sole motivation to enter into these encounters. Due to economic prob-

lems and the impossibility to meet the financial requirements connected

with marriage, young people in Egypt marry later than ever before (Abdalla

2007:37–38; El Feki 2013:36–42; Hoodfar 1997:266–267). Men enter matri-

mony at the age of twenty-nine on average (El Feki 2013:35). Encounters

with ‘Western’ women present the rare chance for an active sex life outside

marriage, which is still almost impossible to have in intra-Egyptian rela-tionships. In fact, Abdalla (2007:39) sees the relief of ‘sexual frustration’

which arises from the ‘complications of marriage’ as the main reason for

what he calls the ‘Dahab phenomenon’. Finally, relationships with ‘Wes-

tern’ women are also considered a quick route to modernity—as the Egyp-

tian agents perceive it—and as a resource for enlarging their cultural

capital. In this context, it must be noted that the tourism-connected flows

of people to Sinai and the Red Sea differ from those in the Nile Valley in

that not only visitors but also most of the personnel working in the tour-ism industry at the beach resorts are not ‘local’ to the area. Many of these

workers have come from the Nile Valley—often equally attracted by the

labour chances and the ‘spirit’ of the place, which includes the promise of

becoming part of its highly specific ‘modern’ setup and its tourist–‘local’

interactions (Abdalla 2007; Jacobs 2010:80–95, 121–122).

Landscapes of Desire 407

While tourist–local sexual relationships have been acknowledged as an

important aspect of the tourist landscape of the Egyptian beach resorts on

Sinai and at the Red Sea coast, their existence at the World Heritage site of

Luxor has hardly ever been noted, let alone been included in the analysis

of the site’s social dynamics. In their 2010 book on ‘Tourism, Performanceand the Everyday’, the case studies which range from package tourist set-

tings at Red Sea resorts to sightseeing trips to Cairo, Michael Haldrup and

Jonas Larsen (2010) stress the experiential, performative and embodied

aspects of tourist travel. The dimensions of gender and sexuality, let alone

sexualised bodies and practiced sex, do not feature in their volume. Like-

wise, Schmid (2008), who investigated the working conditions of Luxor’s

informal guides, does not even mention that establishing sexual relation-

ships with tourists is one of their main economic strategies. TimothyMitchell (2002:197), who did fieldwork in Qurna in the 1990s, reiterated

the stereotyped version of the phenomenon, stating that ‘a few dozen

young men did better by finding a foreign tourist to marry—usually a

much older woman, who might visit each winter for a few weeks and with

luck was wealthy enough to set the husband up in business’. In his magis-

terial work on the Qurnawi community, Kees van der Spek (2011:278, 358)

noted in passing that ‘financial support obtained from intimate relations

with westerners is not uncommon’ and that ‘marriage between young Qur-nawi men and middle-aged European women […] may offer an economic

base for some’. Only Sandrine Gamblin maintains that for local youths

who work as informal guides and vendors, ‘la rencontre touristique et le

mariage avec une etrangere, pour les plus demunis, sont les seules voies

operatoires de promotion individuelle et economique qui leur sont access-

ibles’ (Gamblin 2006:93) and that these constellations constitute ‘une res-

source premiere d’enrichissement economique et symbolique pour des

individus qui se situent aux marges sociales et ne possedent ni biens, niterres, ni capital educatif negociable sur un marche egyptien du travail deja

satures de diplomes au chomage et declasses’ (Gamblin 2007:243).

Gamblin’s observations are in accordance with studies on the economic

situation of Egyptian youths and young adults. High unemployment rates,

few job opportunities and low wages in the formal labour market make it

difficult for young people—of varying education levels alike—to earn a liv-

ing and build a life (eg. Abdalla 2007:31–34; Muller-Mahn 2001:229–233;

Schielke 2008, 2009). And while they cannot fulfil even their more modestaspirations, the global media fuel visions of a life replete with all kinds of

personal freedoms and commodities. The magnitude of the ensuing dis-

crepancy is illustrated in the 2010 documentary ‘Messages from Paradise’.9

Its producer, anthropologist Samuli Schielke, who worked with young men

in rural areas of Lower Egypt, writes: ‘The increasing connectedness of

the village with global media and migration flows offers imaginaries and

408 CLAUDIA NASER

prospects of a different, more exciting life, of material wealth and of self-

realisation. Village life becomes measured against expectations that by far

exceed anything the countryside or the nearby cities have to offer’ (Schielke

2008:258). A sense of ‘emptiness’, the ‘lack of prospects’ and the ‘desperate

urge to migrate’ are topics discussed daily among the young men (Schielke2008:260, 2009:173). Migration, Schielke (2009:173) concludes, is seen as

‘the grand paradigmatic strategy of escape and success’. While the young

men in the Delta village of Nazlat al-Rayyis derive their hopes, fantasies

and aspirations from TV10 and the internet, as well as from the tales of

those who have migrated, people in Luxor live with the physical manifesta-

tions of these imageries on a daily basis. A small stream of the ‘global flows

of mediated images, styles, goods’ (Schielke 2009:172) constantly passes

through their lives and leaves its marks on the cultural space in which theygrow up, live and work. The resort hotels, the cruise ships, the coaches, the

tourists themselves with their conspicuous dress styles, their equipment

and their habitus—all this is omnipresent and as much part of the every-

day experience of Luxor’s inhabitants as distinctly set apart from it. The

perception of these ‘snippets’ of ‘Western’ life converges with more general

conjectures about ‘Western’ culture, economic affluence and moral consti-

tution—forming the basis of knowledge upon which the residents of Luxor

and Qurna interact with tourists and other visitors.

Tourist–Local Sexual Encounters in Luxor

The material for the present study was collected from a variety of

sources.11 Non-participant and participant observation in Luxor, ie. watch-

ing locals and tourists interact and interacting with them myself, were basic

constituents of the research.12 Initially, I had expected that communicativesituations might arise from this in which I could either conduct interviews

or arrange for later meetings. But, it showed that tourist routines would

not easily allow for this. Thus, in order to identify potential interview part-

ners, I talked to people of my acquaintance who had recently visited Luxor

and to those to which they in turn referred me on to.13 This proved to be

an effective method. Unexpectedly, all persons I approached were happy to

discuss the subject, whether or not they had experienced any sexual

encounters in Luxor. They wanted to relate their experiences and werekeen to learn how a scientific analysis of tourist–local sexual encounters

might look. It was clear from the beginning that connecting with local

guides and vendors would be difficult in the limited time available and that

intruding into their workplaces and business activities—both when they

approached me or other tourists—was delicate (cf. Schmid 2008:109–110,

118–119; van der Spek 2011:356–359). Interestingly, whenever a relaxed

Landscapes of Desire 409

conversational situation developed, my Egyptian interview partners also

talked to me freely. They wanted to trade knowledge and asked for infor-

mation and my opinion on things they thought might make their interac-

tions with tourists more successful (cf. Schmid 2008:113). Another

important data source was the internet, where, in particular, the involved‘Western’ women exchange experiences and consult and console each

other. Finally, I used novels and autobiographical writings in which fanta-

sies and perceptions of sexual encounters in the environs of the World

Heritage site of Thebes are produced and reproduced. Although the result-

ing picture is very much a pastiche, it offers insights into the issue of how

tourist–local sexual relationships reside in the wider social contexts of Lux-

or and the World Heritage site of Thebes, how the worlds of the partici-

pating partners converge—or not—and what repercussions this has on theproduction, appropriation and consumption of the heritage space itself.

What soon became apparent during my fieldwork in Luxor was that

despite the openness with which the subject was discussed by involved par-

ties and the wider public, it is still a sensitive topic. It transgresses domi-

nant social practice and officially propagated concepts of morality in

several respects. Of prime concern in this regard is the questionable status

of extramarital relationships in Egyptian society. Though not actually pro-

hibited by law—unless one of the partners is married, in which case itwould come down to adultery—sexual encounters prior to, or outside of,

wedlock are still considered as irregular and undesirable. Whenever they

occur in an Egyptian-only context, they would be kept secret and trans-

formed into a socially and legally sanctioned status, ie. matrimony at the

earliest possible moment (cf. El Feki 2013). The ensuing moral climate has

direct repercussions on how tourist–local relationships are conducted and

how the involved partners make use of and shape public and private

spaces. Firstly, such relationships are hardly ever expressed openly, eg.mixed couples rarely go sightseeing together. It is almost only shopping

areas and privately run restaurants and discos outside the resort hotels that

provide ‘informal’ public spaces which are accessible for and used by

mixed couples. Moreover, unmarried Egyptian–non-Egyptian couples can-

not usually book a hotel room together. Even renting a holiday flat from

private owners is problematic. As one homepage states: ‘Only guests regis-

tered at the flats can stay or use the facilities and because of police restric-

tions we are unable to offer accommodation to mixed Egyptian/non-Egyptian couples’14—a restriction which is clearly directed at tourist–local

relationships (cf. Abdalla 2007:41). Thus, partners in such relationships

constantly face the problem of arranging a private space. Thus, the prover-

bial ‘sex in the felucca’ (see seventh paragraph in this section) may not

only be a display of promiscuity but can also be put down to a lack of

alternatives.

410 CLAUDIA NASER

The attempt to circumnavigate these difficulties has contributed to the

rise of a practice which has been making headlines in recent years: the so-

called urfi marriages. Urfi is a form of informal common-law marriage, the

administrative proceedings of which consist of the two partners signing a

document in front of a lawyer or a cleric, sometimes in the presence oftwo witnesses. Urfi marriages are not legally binding and can be as easily

concluded as they can be dissolved by one or both partners at any stage. In

recent years, they have become increasingly popular among young Egyptian

couples who cannot afford an official marriage (El Feki 2013:44–46). But,

they are also common in foreigner–Egyptian relationships (Abdalla

2007:40–42). Indeed, a search for the keywords ‘urfi’/‘orfi’ and ‘Egypt’/

‘Luxor’ on the internet gives numerous hits on websites and online fora

which deal with the questions ‘Western’ women have regarding this kindof marriage, its legal status and its potential consequences.15 A study

quoted in this context states that over 17,000 marriages between young

Egyptian men and older foreign women were registered in 2010 compared

to just 551 in 2005.16 I have not been able to procure a copy of this study,

which was undertaken by the Research Department on Human Trafficking

in the Ministry of Family and Population in Cairo. Thus, I could not

ascertain whether it pertains to ‘official’ civil marriages only, which have to

be contracted at the Shahr’ al Aqari in Cairo or Alexandria when theyinvolve a foreign partner, or whether it also includes urfi marriages. Either

way, the figures quoted indicate a dramatic increase in foreigner–local mar-

riages and show that such partnerships have become a widespread phe-

nomenon over the past decade.

A survey of relevant internet fora provides an insight into the personal

stories behind these figures. Some contributions capture the bliss,17 others

discuss the practicalities and the challenges of living with an Egyptian part-

ner,18 while again others express the doubts, frustrations and disenchant-ment of the women involved.19 One of the most frequently visited sites is

www.1001geschichte.de with 3,000 users daily according its operators, who

claim it to be Europe’s largest platform to fight ‘bezness’. The site features

a forum on Egypt and a blacklist where disillusioned women can report

the name and the workplace of their (former) lovers and, vice versa, seek

information about individual men. Similar services are also offered by sev-

eral other websites.20.

The majority of the ‘Western’ women involved in relationships withEgyptian men perceive these encounters in a discourse of romance and the

exotic (cf. Jacobs 2010, 2012). Their segregation from both the tourist and

the Egyptian everyday social cosmos (see sixth and seventh paragraph in

this section) encourages a freely selectable anchoring in space and time. As

Jacobs (2010, 2012) in her study on Sinai has argued, the male subjects are

‘othered’ and constructed under reference to the holiday attractions chosen

Landscapes of Desire 411

by the women—in the case of Sinai, the wilderness of the desert and the

Bedouin culture of its inhabitants. In part, the same can be argued for

Luxor. Here, the Pharaonic heritage comes into play: temples, tombs and

the ‘exotic’ men—may they wear galabiya or jeans—can converge into a

single image of the ‘Other’. American travel writer Jeannette Belliveau(2006:2, 291) speaks of ‘a man of colour, who looked as exotic as a pha-

raoh’ and ‘this ancient region’, when referring to the Middle East and

North Africa. Such fantasies use the material inventory and the narratives

of the archaeological heritage sites in a way which perpetuates ‘the binary

stereotypes first explored by nineteenth and twentieth century women trav-

ellers that construct the “local” man as anti-modern other’ (Jacobs

2012:148). In general, such imageries are still strong and employed by all

parties, when they conform to the expectations of the involved actors. Forexample, local guards at the major sights of Luxor and Thebes all wear tra-

ditional galabiya. I could not ascertain whether this is done by command

or if it follows a tacit rule among this occupational group, but either way

the flaring robes add a picturesque note to many tourist photographs (Fig-

ure 3). This earns their wearers additional bakshish (Figure 4) and at the

same time feeds a vision of the exotic ‘Other’ which weaves the Pharaonic

past and Islamic tradition into an image in which ‘culture and place lock

together in a timeless communion’ (Beezer 1993:127).

Figure 3. A female tourist posing for a photograph with two guards at the Temple

of Hatshepsut, Western Thebes (photo Claudia Naser, 2010)

412 CLAUDIA NASER

Another—seemingly opposite—way in which ‘Western’ women makesense of their relationships with Egyptian men is illustrated in several auto-

biographical writings (eg. Ismail [ed.] 2012) and works of fiction such as

‘Love in Luxor’ by Gill Harvey (2005). The latter tells the story of a teenage

romance between Jen and Ali. The physical setting of Luxor figures only

marginally in the narrative, coming up mainly in connection with Jen’s

dutifully undertaken excursions to the major heritage sites and the couple’s

unsuccessful search for a private space allowing them to advance their inti-

macy. What the story highlights instead is Ali’s role as a ‘cultural broker’who grants Jen access to what she perceives as the ‘real’ Egypt, complete

with tea, galabiya and a visit to a wedding in one of the villages on the west

bank. How well this image goes down with the target audience becomes

clear from one of the comments on a rating website: ‘The first book that

made me want to travel somewhere exotic. I loved this book so much when

I was 13.’21 In this context, the topic of the ‘Other’ not only includes the

male subject—looks, language and clothing—but also the cultural experi-

ence he offers. This role of the local partner as a ‘cultural broker’ has beencited by several researchers as a typical element of relationships between

Figure 4. The two guards in Figure 3 requesting bakshish from the woman’s com-

panion after he took their picture (photo Claudia Naser, 2010)

Landscapes of Desire 413

foreign women and local men also in other destinations of the global south

(eg. Pruitt and LaFont 1995; Dahles and Bras 1999). In the case of Luxor,

the involved women usually define the world of ‘modern’ Egypt to which

the local partner gives privileged access in a pronounced juxtaposition with

the Pharaonic past manifest in the attractions of the World Heritage site. Asa rule, they name their fascination with ancient Egypt as the original reason

for visiting Luxor and describe their interest in ‘modern’ Egypt as a later

addition which developed through their involvement with an Egyptian part-

ner or was advanced by it. The intimacy of the sexual relationship is cou-

pled with an intimacy with the culture, which could otherwise not be

obtained so quickly and easily. While ancient Egypt is accessible to every

visitor, the acquaintance with ‘modern’ Egypt is something not usually

achieved by package tourists. This view transposes the master narrative ofthe World Heritage site, with its focus on the Pharaonic past, into the realm

of personal experience in a very peculiar way: countering the exclusion of

‘modern’ Egypt, and all its pasts except the Pharaonic, from the heritage

rhetoric, the involved women make the conquest of the missing component

their private endeavour. Paradoxically, they thereby take up the dominant

heritage discourse in one seminal aspect, namely in opposing the two

worlds, ‘ancient’ and ‘modern’, thus tacitly contributing to the on-going

reproduction and naturalisation of this categorical differentiation.It will depend on the individual disposition and perspective of the involved

women as to how much of what they discern as the ‘real’ modern Egypt are ide-

alisations which also reside in the realm of the exotic and the ‘Other’ (cf. Jacobs

2010, 2012). Many narratives reiterate orientalist fantasies: They are about tea,

traditional clothing and intact patriarchically organised family life, and not

about social tensions and the existential problems discussed by the youths who

appear in Samuli Schielke’s interviews (see fourth paragraph in section “Tour-

ist–Local Sexual Encounters in Egypt and Beyond: More Than Putting a Nameto Them”). Again, these images are used and reproduced by all involved parties,

and new ones can be added which play on relevant themes and conform to the

overall expectations of the partners. As Pruitt and LaFont (1995:422) stated

regarding Jamaica, ‘by elaborating on features of their gender repertoire, men

articulate the women’s tourists’ idealizations of local culture and masculinity,

transforming their identity in order to appeal to the women and capitalize on

the tourism trade’. One such image, or role, is that of the felucca captain—a

character who appears in Gill Harvey’s (2005) ‘Love in Luxor’ as well as in manynarratives of ‘Western’ visitors to Luxor.22 The place which this particular role

takes in the public perception of tourist–local sexual encounters is aptly illus-

trated by the bar menu sign in the King’s Head Pub, a privately run pub in Lux-

or. It offers ‘Sex in a Felucca’ as cocktail of the week, while the drinks menu

adds ‘Sunburnt Russian’23, ‘Bloody Hassle’ and ‘Egyptian Husband’.24 Ironically,

the latter drink is known as ‘Gale Warning’ elsewhere.

414 CLAUDIA NASER

While many, though certainly not all, ‘Western’ women involved in for-

eigner–local sexual encounters make sense of their relationships through the dis-

courses of ‘romance’ and ‘otherness’, the Egyptian men construct them in a

framework of social and economic aspirations (cf. Abdalla 2007; Jacobs 2010).

Their interests centre on the improvement of their socio-economic situation,their sex life and their cultural capital (see third paragraph in section “The Infor-

mal Employment Sector” and also first three paragraphs in section “Tourist–

Local Sexual Encounters in Egypt and Beyond: More Than Putting a Name to

Them”). To which end a sexual encounter may lead is often not foreseeable in

its incipient phases. Thus, the attitude of the men can best be described as ‘gen-

eralised’ or ‘open-ended’ (cf. Dahles and Bras 1999:286–287; Oppermann

1998:13–15). They take their chances as they come, thus creating the constant

flow of propositions, offers and advances which accompany the tourists whenthey walk in the streets of Luxor and through the hills of the Theban Necropolis.

One central question in the wider discussions of tourist–local sexual

encounters is to which degree they are economic, ie. which financial or

otherwise commodified benefits the involved men derive from them. In

Egypt, as in other destinations of the global south, the spectrum is wide and

most women would not understand their contributions as a ‘payment’ for

sexual services (cf., eg. Sanchez Taylor 2001:754, 757). Should these encoun-

ters still be subsumed under the heading of sex tourism or regarded as ‘sex-ual-economic exchanges’ as Sanchez Taylor (2006; see first paragraph in the

section “Tourist–Local Sexual Encounters in Egypt and Beyond: More Than

Putting a Name to Them”) has proposed? What about those relationships in

which no financial transactions have (yet) taken place? Several observations

may aid us come to terms with these questions. First and foremost, one

must be clear about the fact that socio-economic inequalities are the prere-

quisite for many of these relationships to develop—if it was not for these

imbalances and the restrictive moral climate concerning intra-societal sexualencounters, most Egyptian men would not be attracted to enter into them.

It is the socio-economic asymmetries and the wildly diverging capacities to

render accessible further economic resources which are at the heart of trajec-

tories where ‘increasing numbers of young men routinely view a relationship

with a foreign woman as a meaningful opportunity for them to capture (the

love and) money they desire’ (Pruitt and LaFont 1995:428). There are two

points which need to be considered in this arrangement: the first is that

these encounters have become a regular economic strategy for one group ofactors, ie. the involved men, the second is that the other group of actors, ie.

the ‘Western’ women, systematically take ‘advantage of an imbalance of

power to obtain a sexual advantage that would otherwise have been denied

them’ (Sanchez Taylor 2006:52). When these conditions are met, MMD rela-

tionships constitute sexual–economic exchanges, even if they are not per-

ceived in this light on an individual level.

Landscapes of Desire 415

One of the reasons why most involved women will not view their com-

mitment within these parameters is that the scope and the timing of the

exchanged services differ widely. This allows the women to label their eco-

nomic contributions as negligible, as lending a helping hand or as building a

basis which is needed to conduct their relationship, for example by establish-ing a business to support both of them in Egypt or by bringing her partner

to Europe. Such ‘romantic’ readings are balanced by a view from the other

side. In 2012, expat interview partners in Luxor reported on rumours about

an MMD training school, where young men are taught how to best extract

the aspired benefits from their ‘Western’ partners, learning for example how

to build trust, issue the right compliments and successfully time their finan-

cial requests. Whether or not such a ‘school’ exists, it is conspicuous that the

economic trajectories of MMD relationships display a pattern of repetitionwhich hints at the recurrent use of a specific tactic on the part of the

involved men. In what I would call a ‘delayed return’ strategy, the Egyptian

partners will not issue straight requests for money at the outset of the rela-

tionship. Instead, they will pay their own expenses and only after a relation-

ship is established talk about a sick relative or another social hardship. At

this point, they will refuse to take financial support, or, if they accept it, duly

pay it back. By and by, bigger problems calling for larger sums will be

needed, which the men will again return. This continues until 1 day theyreceive a really substantial amount—to purchase a car, a house or land—and

this will not be paid back; a climax which also often signals the end of the

relationship. In the absence of quantitative data, it is hard to estimate the

ubiquity and the magnitude of such transactions and the impact they have

on the local economy and the livelihoods of individual men. Nonetheless,

such stories abound and they are clearly attractive enough to make many

members of Luxor’s male population attempt a similar career.

My Encounter with Ahmed

During my stay in 2010, I paid a visit to one of the minor tourist attractions

at Western Thebes.25 Of course, I was approached by the ghafir, ie. the guard

who offered to explain things to me. I rejected and told him that I was a pro-

fessional, familiar with the site and acquainted with some archaeologists who

had worked there. Thereupon, the ghafir let me explore, but returned afterseveral minutes with the offer of tea. As I had constructed a social connection

between us through my reference to common acquaintances, I felt obliged to

accept. As we sat down and talked, it took Ahmed only a few minutes to ask

me if I wanted to have sex with him. I turned this suggestion down, but con-

tinued the conversation despite the awkwardness I felt for a moment or two.

I told Ahmed that I was working on the phenomenon of tourist–local sexual

416 CLAUDIA NASER

encounters in Thebes and that I was interested to learn how he had come to

approach me that bluntly. Upon that, he told me that his wife was pregnant

and in bad health, thus not able to have sex, and that he was looking for

another partner to relieve his abstinence. I asked him how he had formed the

opinion that I might consent, as I had—prior to his offer—made it clear thatI was in Luxor as a professional and not on vacation with the potential objec-

tive to acquire a lover. I also enquired as to whether he thought that

approaching me might be bad for his career, as I might complain to his supe-

riors. To this, he replied that ‘his’ site did not attract many visitors and that

he did not judge himself to have the optimum disposition for success due to

his age and his looks. Thus, he had to take every chance he could get. Contin-

uing along this line of thought, he told me that according to his experience,

‘Western’ women preferred younger men and particularly cared for goodteeth and a generally good state of health and hygiene—an observation which

he wanted to have confirmed and explained by me.26 Our conversation then

developed into him trying to acquire knowledge which would allow him to

better classify ‘Western’ women according to their nationality, which he

thought determined whether they would generally be willing to enter into a

relationship with an Egyptian and what kind of men they preferred. After the

end of our talk, we parted amiably.

Apart from initial disgust, which dissolved during our progressivelyfriendly conversation, my main reaction to this encounter was utter amaze-

ment. Ahmed had named sexual desire as his prime motive for seeking out

‘Western’ women and to satisfy this he even risked his employment. Work-

ing as a guard provided him with a stable income, of which many Qurna-

wis could only dream. Economic need was not the driving force behind his

proposition, though he may have kept an open mind on possible develop-

ments in this regard. My encounter with Ahmed shows that while there is

certainly the recurring constellation of elder women taking on younger lov-ers who enter such relationships for economic benefit, alternative agendas

and projections must not be dismissed. Simultaneously, Ahmed’s aspira-

tions were shaped by the manifestations of tourist–local sexual encounters

in his social environment—from witnessing them, he had formed his own

conclusions and expectations. In order to make sense of these diverging

dimensions, it may be useful to differentiate between the individual

encounter and tourist–local sexual relationships as a social institution. As

argued above, as a social institution, such relationships are rooted in theeconomic imbalances between ‘Western’ tourists and most members of the

local populations in destinations of the global south. As individual prac-

tices, they incorporate many other influences, such as the moral concepts

held by both partners, individual aspirations, ideas about love, sex and

consumption and many other things. Thereby, individual practices are con-

structed within the framework of the social institution—to paraphrase

Landscapes of Desire 417

Ahmed: he does it because everyone does it. The straightforward proposi-

tion of sex to an unknown woman is only possible because tourist–local

sexual relationships are an omnipresent phenomenon in the social world of

the Theban Necropolis; they have become ‘normalised’ and from a certain

perspective constitute ‘regular’ social behaviour. Vice versa, individualpractices and perceptions reproduce and reshape tourist–local sexual

encounters as a social institution. This aspect has been highlighted by one

‘Western’ repeat visitor, who suggested that rapidly growing media con-

sumption and increased access to pornography on the internet shape per-

sonal visions, which lead many men to believe that they could experience

freer and more exiting sex with ‘Western’ women than with Egyptian part-

ners (cf. El Feki 2013:31, 68–69). This development may have added to the

trend for increasingly blunt requests for sexual contact, of which the inter-viewee reported several instances which were similar to my experience with

Ahmed. Indeed, pornographic internet sites featured prominently among

the one hundred most frequently visited websites in Egypt in 2012.27

Moving Through the World Heritage Site of Thebes

The encounter with Ahmed left a deep impression on me and lastinglydetermined my memories of the site in question. It also influenced my atti-

tude towards further encounters with Egyptian men at the peripheries of

tourist sights. I became more aloof and adverse—like many other visitors

to Luxor and the World Heritage site of Thebes.28 When tourists’ minds

are set on visiting archaeological attractions, commercial and sexual propo-

sitions from local entrepreneurs can easily be regarded as distracting and

disturbing. Still, there is a constant flow of such offers. They form an inte-

gral part of tourists’ experiences in Luxor and as such become incorporatedinto visitation routines. Quickly, tourists learn that moving through the

public space of Luxor, particularly at the peripheries of tourist sights,

means being approached—irrespective of whether one is in a group or sin-

gle, a man or a woman, clearly set on one’s target or walking leisurely. The

strategies visitors employ to deal with these approaches are as stereotypical

as the tactics of the guides themselves. Taking advice from their guide

books, from fellow travellers or their official guides, generally tourists will

give stereotyped answers or will not respond at all, hurrying past the ven-dors. Only when they are genuinely interested in one of the offers, or when

the guide is particularly skilled, they will pause and talk. Still, in most

encounters, there is an element of uneasiness on the side of the tourists,

which arises from their uncertainty as to how the interaction should be

rated and whether they are ‘pulled over the barrel’ (cf. Schmid 2008:115).

The informal setting, the fleeting nature of the transactions and the

418 CLAUDIA NASER

strategy of ambivalence employed by the guides all add to the discomfort

inherent in these situations.

Tourists also learn quickly which spaces are free from these strenuous

encounters: the hotels and the heritage sights, to which the informal guides

and vendors have no access. From the perspective of tourism studies, thesespaces are called ‘enclaves’ (eg. Schmid 2008). They provide the tourists

with an environment which is constructed specifically for their needs and

removed from the everyday social reality of the host country. In these

‘enclaves’, contact between local residents and tourists is narrowed down

and limited to specific constellations, in which locals most frequently

appear as service personnel (for Luxor cf. Gamblin 2007:203–208). Mitchell

(2002:197) described this kind of ‘enclaving’ as the typical pattern of tour-

ist development in regions outside Europe and North America since the1980s and as ‘required by the increasing disparity between the wealth of

the tourists and the poverty of those whose countries they visited’. At the

World Heritage site of Luxor, the consequences of this process manifest in

several dimensions. They have left their marks on the physical landscape of

the heritage site, and they have divided its social space into two spheres: a

public one, to which everybody has access and which constitutes the arena

of unregulated tourist–local interactions, and a ‘semi-public’, ‘enclaved’

one into which tourists can withdraw in order to avoid contact with localresidents. While the public sphere is connected to the social reality of

today’s Egypt in that it is part of this reality and presents certain facets of

‘real life’ to tourists, the ‘enclaved’ spaces are very much secluded and

removed from this reality. In recent years, the separation of these two

spaces has been increasingly reinforced by physical interventions, which

have resulted in purpose-built access zones, walls, fences and the ‘cleansing’

of the hamlets of Qurna (Tully and Hanna, this volume, van der Spek

2011:333).The growing tensions arising from this situation were made clear in a

2012 news item which reported that ‘a number of travel agencies [were]

threatening to suspend their daily flights to […] Luxor due to what they

say are recurring incidents of tourists being harassed’29. Representatives of

these travel agencies and tour operators spoke of ‘indecent insults’ and

aggressive undertones, and it was stated that ‘the complaints blame in par-

ticular street vendors at Luxor’s temples and archaeological sites, specifi-

cally in the city’s West Bank area’. This example illustrates the viciouscircle which characterises current tourism development in Egypt. Myriad

affluent foreign visitors enter a host society which is riddled with severe

economic and social problems. Over many years, participation in the riches

of the tourists has developed into a key economic strategy for a specific

social group, namely younger men seeking formal or informal employment

in the tourism sector and at the peripheries of tourist flows. They see this

Landscapes of Desire 419

engagement as the ‘royal road’ out of their structurally disadvantaged

socio-economic position and as a chance to fulfil their personal aspirations

to a degree otherwise unobtainable. As the ‘enclaving’ of tourism is pur-

sued by tour operators and political decision makers alike, the interaction

spaces for this ‘professional’ group become more and more confined. Ontop of this issue, declining tourism figures in the aftermath of the 25th

January 2011 revolution have further lowered the number of potential cus-

tomers.30 As a result, competition gets fiercer and local entrepreneurs take

their chances whenever they can and in whatever shape they make take.

The more disadvantageous this mixture gets, the more frustration and

aggression comes into play and may lead to interaction scenarios which

one would judge as clearly counterproductive to striking a deal. Business

propositions turn into hassle and frustrations about bad business—in com-bination with unsettling wider social conditions—find an outlet in plain

harassment.31 From the perspective of those stakeholders who benefit most

from international tourism, ie. the international tour operators and the

Egyptian state and its various institutions, this forms a valid reason to fur-

ther accelerate the segregation between visitors and local residents and

speed up the processes of ‘enclaving’.

In this context, the sexual encounters between tourists and local resi-

dents take on a curious position. They undermine the efforts of thosestakeholders who want to construct a ‘clean’ site with an exclusive focus

on heritage tourism. They also negate the emphatically issued condemna-

tion of extramarital sex, which still permeates mainstream Egyptian society,

cultivating strategies of avoidance and ambiguity, like the urfi marriages,

which barely conceal the irreconcilability of these relationships with wider

social norms (Abdalla 2007; El Feki 2013). At first glance, these contradic-

tions and their seemingly individual solutions seem to remove these

encounters from connotations of blatant ‘sex tourism’, instead easing theirperception towards discourses of ‘romance’ and ‘true love’. But, these indi-

viduating tendencies only gloss over the fact that as a social institution,

these relationships are still firmly rooted in an economic context. The part-

ners in these encounters usually possess ‘radically unequal access to

resources, and it is the negotiation of these within the context of their ero-

tic engagements’, identified as ‘a feature of an emerging global sexscape’ by

Hastings Donnan and Fiona Magowan (2010:111–112), that brings socio-

political and economic issues to the fore. In this context, it must not beoverlooked that encounters between ‘Western’ female tourists and Egyptian

men are but one version of tourist–local sexual relationships in Luxor. The

place is well known for its homosexual exchanges. On various occasions,

interview partners also hinted at more problematic forms of sex tourism,

including the pursuit of unsafe sex by HIV-positive ‘Western’ gay men and

organised child prostitution. As no data exist on these phenomena,32 it is

420 CLAUDIA NASER

currently impossible to paint a representative picture of sexual–economic

exchanges in Luxor.

I have stated from the outset that I do not deem it legitimate to parallel

personal relationships and superordinate relations of power ‘in any simplis-

tic or straightforward way’ (Kulick 1995:24, note 1). While the tourist–localsexual encounters explored in this paper could simply be dismissed as a

facet of globalisation, one should acknowledge that they also have a very

personal side. They can involve strong emotional, existential and economic

interests and thus be of major concern to their participants. This not only

applies to the ‘Western’ women entering in these relationships but also to

the Egyptian men who try to make a living from them or pursue sexual

fulfilment, while constantly juggling their aspirations and potential failure

within dominant socio-religious value systems (Abdalla 2007). Simulta-neously, I agree with Donnan and Magowan (2010:116) in their point that

there is a ‘dialectic between personal intimacy and the global flows and

interconnections that both featured in the colonial past and pervade the

increasingly mobile present’. I would argue that the structural inequalities

upon which these flows are based, and the tensions which arise from them,

put human existence and experience in a precarious and ambivalent posi-

tion. In this context, personal fulfilment can only be achieved at a high

cost and remains itself precarious, unstable and ambivalent—a fact whichholds equally true for all involved actors: the visitors pursuing the Phara-

onic past on the path of cultural tourism, the ‘Western’ women who get

involved in tourist–local sexual relationships and the Egyptian men who

chase after a different life through these encounters.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper was undertaken within the framework

of the Berlin Cluster of Excellence TOPOI, whose support is gratefully

acknowledged. I thank Gemma Tully for making me aware of the term

MMD as well as for commenting on an earlier version of this paper.

Notes

1. See http://www.topoi.org/project/topoi-1-72/ (all websites referred

to in this paper were last accessed on 07/10/2013).

2. For a discussion of previous relocation attempts and the objectives

connected with them, see Mitchell 2002.

3. The buzzword of the ‘open-air museum’ was coined in the master-

plan ‘Luxor 2030’ which was developed and inaugurated under

Landscapes of Desire 421

former Luxor governor Samir Farag. See http://www.samirfarag.

com/ for a copy of the plan and a list of the implemented mea-

sures.

4. See, eg. http://www.escapeartistes.com/2012/04/16/an-open-letter-to-

the-touts-of-egypt/, http://lauratraveler.net/2011/10/a-long-overdue-update-from-luxor/, http://www.traveldudes.org/travel-tips/luxor-also-

known-hassle-capital-egypt/2962, http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/

Africa/Egypt/Muhafazat_Qina/Luxor-2008656/Warnings_or_Dangers-

Luxor-Harrassment-BR-1.html or http://www.tripadvisor.com.au/Show

UserReviews-g294205-d321166-r122513073-Valley_of_the_Kings-Luxor

_Nile_River_Valley.html.

5. The same pattern has been described in some of the travel logs and

blogs quoted in note 5.6. ‘Bezness’, Nouri Bouzid, France, Tunisia, Germany, 1992.

7. See, eg. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1294752/Why-does-

middle-aged-woman-think-HER-holiday-seducer-real-deal.html and

http://simplyleanne.blogspot.de/2012/01/letters-from-egypt-my-moha

med-is.html.

8. The earliest mention of MMD I could trace is by blogger LizzieD

on http://lizzied.blogspot.de/2005_09_01_archive.html from 2005.

9. ‘Messages from Paradise #1. Egypt: Austria. About the PermanentLonging for Elsewhere’, Samuli Schielke and Daniela Swarowsky,

Austria and the Netherlands, 2010.

10. For an analysis of the lifestyles transported in/by Egyptian TV, see

Abu-Lughod 2005:193–226.

11. Fieldwork in Luxor was carried out in February 2010 and February

2012, with 1 week spent there each time. Interviews were conducted

in Luxor, London and Berlin between 2010 and 2013.

12. Non-participant observation has been defined as a ‘relatively unob-trusive qualitative research strategy’, suitable when interest lies ‘less

in the subjectively experienced dimensions of social action and more

in reified patterns that emerge from such action’; it is thus particu-

larly suitable when studying how people use public space (Williams

2008:561).

13. For an evaluation of this recruiting strategy, see Liamputtong

(2007:48–49).

14. See http://www.flatsinluxor.co.uk/about-flats-in-luxor/terms-and-conditions/.

15. See, eg. http://orfi-wives-egypt.blogspot.de/2011/09/what-is-orfi-marriage.

html, http://www.egyptsearch.com/forums/Forum2/HTML/004660.html

and http://forum.1001geschichte.de/viewtopic.php?f=4&t=3504.

16. See http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2011/01/21/134435.html.

422 CLAUDIA NASER

17. See, eg. http://oneheartinegypt.blogspot.de/2011/08/falling-for-love.

html and http://arabiclove.aktivforum.org/.

18. See, eg. http://www.luxor4u.com/forum/viewforum.php?f=6 and http://

www.zickes-aegypten.com/wbb2/board255-liebe-beziehungen-und-

familie-in-%C3%A4gypten-mit-%C3%A4gyptern/.19. See, eg. http://www.againstbezness.ch/ and http://www.egyptsearch.

com/forums/ultimatebb.cgi?ubb=forum;f=3.

20. See, eg. http://www.dezy-house.ru/ and http://kunstkamera.net/

21. http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/8050657-love-in-luxor.

22. Cf., eg. https://de-de.facebook.com/pages/The-Felucca-Captains/135

812526475990, http://patryantravels.wordpress.com/2013/02/05/the-

felucca-fantasy-ride/ and http://pyramidqueen.wordpress.com/2013/

04/23/island-3some/.23. The percentage of tourists from Eastern Europe has gone up expo-

nentially in/over the last few years; cf. http://www.capmas.gov.eg/

pepo/364_e.pdf. Scantily clad female Russian visitors sporting a

heavy sunburn have become a frequent sight in the major attrac-

tions of Luxor and Thebes.

24. See http://kingsheadluxor.com/main/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/n42

503390632_1488199_53923.jpg and http://kingsheadluxor.com/main/?

page_id=7. Cf. Gamblin 2006:passim, esp. 87 on the pub and itsfounder.

25. The location of the incident has been obscured and the name of the

man has been changed in order to retain his anonymity.

26. For a similar ‘trading of knowledge’, see Schmid (2008:114).

27. See http://english.alarabiya.net/articles/2012/11/13/249405.html. The

quoted statistics had been taken prior to the renewed request for a

ban on pornographic websites in Egypt, which had first been issued

in 2009; see http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContentPrint/1/0/57471/Egypt/0/Egypts-prosecutorgeneral-orders-ban-on-porn-websit.

aspx.

28. See note 5, above, for some voices in this regard.

29. http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/citing-harassment-compla

ints-travel-agencies-threaten-suspend-luxor-flights.

30. The number of international tourist arrivals to Egypt has dropped

from 14.7 million to 11.5 million from 2010 to 2012; see http://www.

capmas.gov.eg/pepo/364_e.pdf.31. This development can be linked to a general increase in sexual

harassment also in intra-Egyptian contexts, which has been wit-

nessed in recent years, especially since the 25th January 2011 revolu-

tion; see, eg. Schielke 2009, El Feki 2013:125–128, http://harassmap.

org or http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bjjqbP7adj8&list=PLOy47

XMO3lTgPoqYgBPdLX22vf58CaqXZ.

Landscapes of Desire 423

32. See only http://www.refworld.org/docid/4fe30cce2d.html for the

‘2012 Trafficking in Persons Report—Egypt’ by the United States

Department of State.

References

Abdalla, M.

2007. Beach Politics. Gender and Sexuality in Dahab. Cairo Papers in Social

Science, vol. 27, no. 4. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo,

New York.

Abu-Lughod, L.

2005. Dramas of Nationhood. The Politics of Television in Egypt. The University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, London.

Belliveau, J.

2006. Romance on the Road: Traveling Women Who Love Foreign Men. Beau

Monde Press, Baltimore.

Beezer, A.

1993. Women and ‘Adventure Travel’ Tourism. New Formations: Post-Colonial

Insecurities 21:119–130.

Dahles, H., and K. Bras

1999. Entrepreneurs in Romance. Tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism

Research 26(2):267–293.

Donnan, H., and F. Magowan

2010. The Anthropology of Sex. Berg Publishers, Oxford, New York.

Egger, I.

2008. Following the Tourists—Durch Reisende zum Reisenden. Tourismus als

moglicher Ausloser kontinentaler und interkontinentaler Migration am Bei-

spiel the Gambia. Diplomarbeit Universitat Wien.

Feki, S. El

2013. Sex and the Citadel. Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World. Chatto &

Windus, London.

Gamblin, S.

2006. Trois experiences egyptiennes de la rencontre touristique. Autrepart

40:81–94.

2007. Tourisme International, Etat et societes locales en Egypte: Louxor, un haut

lieu dispute. Doctorat de science politique, Institut d’Etudes Politiques de

Paris, Paris.

424 CLAUDIA NASER

Haldrup, M., and J. Larsen

2010. Tourism, Performance and the Everyday: Consuming the Orient. Routledge,

London, New York.

Harvey, G.

2005. Love in Luxor. Piccadilly Press, London.

Herold, E., R. Garcia, and T. DeMoya

2001. Female Tourists and Beach Boys. Romance or Sex Tourism?. Annals of

Tourism Research 28(4):978–997.

Hoodfar, H.

1997. Between Marriage and the Market. Intimate Politics and Survival in Cairo.

University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford.

Ismail, A. (editor)

2012. “Mein Agypter ist anders!” Besondere Paare von heute. Engelsdorfer Verlag,

Leipzig.

Jacobs, J.

2010. Sex, Tourism and the Postcolonial Encounter: Landscapes of Longing in

Egypt, New Directions in Tourism Analysis. Ashgate, Farnham, Burlington.

2012. Queens of the Desert: Colonial Nostalgia and the Ethnosexual Encounter.