Regime Change and The Administration of Thebes During The Twenty-fifth Dynasty HISTORICAL...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Regime Change and The Administration of Thebes During The Twenty-fifth Dynasty HISTORICAL...

xxv

II Historical Background

II.1 The Twenty-first Dynasty

Towards the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, during the reign of Rameses IX, the High

Priest of Amun at Karnak, Amenhotep, was depicted in a relief at the same size as

the king, indicating a previously unprecedented equality of status between the two.1

During this time Egypt had suffered from repeated disturbances brought about by

groups of Libyans, declining economic conditions, and, consequently, strikes and

tomb robberies. After the very short reign of Ramesses X about whom almost

nothing is known, the situation continued into the reign of Ramesses XI and appears

to have worsened. At a certain point no later than his year 12, the Viceroy of Nubia,

Panehsy arrived in Thebes to restore order, however the economic situation made it

difficult for him to feed his troops leading him to assume the role of Overseer of the

Granaries which brought him into conflict with the High Priest Amenhotep. The

latter was at one point besieged in the temple complex of Medinet Habu by Panehsy

and appealed to the king for help. Panehsy began marching north, ransacked Hardai

in the 17th

Upper Egyptian nome, and perhaps reached further north but was

eventually pushed back to Nubia by an army of the king led probably by a general

named Payankh.2 Payankh subsequently took over the titles of Panehsy including

Viceroy of Nubia, and also that of Vizier, and became Chief Priest of Amun on the

death of Amenhotep. All the most important Upper Egyptian titles were thus

concentrated in a single individual and Payankh’s ‘coup’ brought about the

beginning of a new era known as wHm mswt meaning ‘repeating of births’,3 a

formula commonly used to signify the beginning of a new era,4 to which events in

Thebes would now be dated.

1 Van Dijk 2000, 301.

2 Van Dijk 2000, 308-9. The general was presumably the later successor of Amenhotep as chief priest

of Amun, however there is as yet not universal agreement as to whether this was Payankh or Herihor

(see below). 3 Scholars often refer to this as the period of ‘renaissance’ (see e.g. Kitchen 1986, 248). The term is

not used here however as ‘renaissance’ in the English language refers almost exclusively to the revival

in art and literature during the 14th

-16th

centuries AD. The meaning in the context of the late New

Kingdom is quite different; ‘rebirth’ is a more neutral term but the Egyptian ‘wehem mesut’ is

preferred here. 4 Grimal 1992, 292

xxvi

During this time, another key figure was to emerge: a Delta official named Smendes

who had taken control of the north, an equal of Payankh in the south.5 The line of

Twentieth Dynasty kings came to an end with the death of Ramesses XI in his

twenty-ninth year in approximately 1069 BC and thus Egypt was now divided

between Smendes, pharaoh of the new Twenty-first Dynasty line in the north, and the

Chief Priest of Amun in the South.

Payankh’s descendents held the office of chief priest of Amun for a further four

generations. Scholars had at one stage concluded that the Chief Priest Herihor was

the predecessor of Payankh, the office having then passed to Payankh and then

directly from Payankh to his son Pinudjem (I).6 However this has now been

challenged.7 The dated documents relating to these individuals suggest Herihor was

the predecessor of Payankh as does the fact that every other chief priest of Amun

thereafter to the beginning of the Twenty-second Dynasty was a descendant of

Payankh’s, however there are several reasons for concluding that the order of these

two individuals should be reversed:8

The titles of Payankh do not fit well with those of his successors whereas

Herihor’s do. Payankh’s are more detailed showing his rise through the

military ranks, and they are closer to those of Panehsy who was in charge of

Nubia from the beginning of the period of wHm mswt. Payankh’s titles refer

to a Pharaoh as in Ramesside times, whereas Herihor’s do not.

Payankh never assumed any royal attributes whereas Herihor and his

successors did.

Herihor and Pinudjem I were both builders in Thebes and Pinudjem

succeeded Herihor directly in decorating the temple of Khonsu.

In any case, by the commencement of the Twenty-first Dynasty a clear shift had

occurred in the way that Egypt was governed, the principal change being that the

country was now divided between the line of Smendes I in the north and the chief

priest of Amun and army commander in the south, the boundary of the two lands

5 Kitchen 1986, 250

6 Kitchen 1986, 252-3.

7 Jansen-Winkeln 1992, 22-37, and 2006c, 225, and refuted by Kitchen 2009, 192-4.

8 Jansen-Winkeln 2006c, 225.

xxvii

having been in the region of Herakleopolis and El-Hibeh. The two rulers were not set

against one another but mutually agreed on the division of territory between them. In

all but minor details there is agreement among scholars on the sequence of

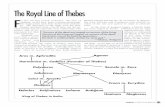

individuals who held power in the north and south, as illustrated in tables 0.1 and

0.2.

Table II.1. Tanite kings of the Twenty-first Dynasty. Kings whose names appear in

bold are well-attested in the archaeological evidence.

Monumental evidence Manetho Notes

Smendes (Nesbanebdjed) I Smendes (26 years) Father in law to HP

Pinudjem I

Neferkare Amenemnisu Nepherkeres (4 years)

Psusennes

(Pasebkhaemniut) I

Psusennes (41 years)

Amenemope Amenopthis (9 years)

Osorkon ‘the Elder’ Osochor (6 years)

Siamun Psinaches (9 years) Identification of Siamun /

Psinaches uncertain.

Psusennes (Pasebkhaemniut)

II

Psusennes (35 years) Almost certainly the

same individual as the

Theban chief priest of

Amun Psusennes

Table II.2. Theban Chief Priests of Amun during the Twenty-first Dynasty.

Individuals whose names appear in bold assumed royal attributes

Chief Priest of Amun

1 Panehsy

2 Payankh

3 Herihor

4 Pinudjem I

5 Masaharta

xxviii

6 Djedkhonsuiuefankh

7 Menkheperre

8 Smendes (Nesbanebdjed)

(II)

9 Pinudjem II

10 Psusennes

(Pasebkhaemniut)

On the surface the division of the country between a king in the north and a chief

priest and army commander in the south was maintained throughout the Twenty-first

Dynasty however the nature of the relationship between the two lines may have

altered significantly over time. Among the chief priests in Thebes all but Herihor

were part of the same family. In several cases the family background of the northern

kings in unclear but there were clearly connections between the two lines.

The Chief Priest of Amun Pinudjem I was married to Henttawy A, daughter of

Smendes I and sister of Amenemnisu; Psusennes I was son of Pinudjem I; the chief

priest Menkheperre, son of Pinudjem I, married Istemkheb C, daughter of Psusennes

I (i.e. he married his own niece); Maatkare B, daughter of Psusennes II, married

Osorkon I, the second king of the Twenty-second Dynasty.9 An alternative

reconstruction of the genealogy of the family of Payankh allows for the possibility

that Pinudjem I was nephew of Smendes I, and his senior living descendent after the

death of Amenemnisu, and that Pinudjem therefore claimed the throne in Tanis at

that point, ensuring that his own son, Psusennes (I) could then take the throne after

him.10

It has been noted that in the earlier part of the Dynasty, while Herihor,

Pinudjem I and Menkheperre were in power, the Lower Egyptian kings were hardly

represented in Thebes at all, but by contrast after the end Menkheperre’s rule, the

kings Amenemope, Siamun and Osochor were all documented in Thebes, while at

that time the chief priest Pinudjem II did not adopt any royal attributes.11

It seems

likely therefore that in the first half of the period the chief priests with royal

attributes dated by their own ‘reigns’ whereas after that the dates all relate to the

9 Kitchen 1986, 282.

10 Taylor 1998, 1154.

11 Jansen-Winkeln 2006c, 229.

xxix

reigns of Lower Egyptian kings, the implication being that Amenemope’s reign

might have signalled a change to the dating system and to the political structures.12

Events described in the so-called ‘Banishment stela’ may shed further light on this

transition. The text inscribed on the stela relates to a rebellion quelled by

Menkheperre. It has been suggested that the reigns of Amenemnisu and Psusennes I

overlapped slightly, and that this, combined with an amnesty declared by

Menkheperre represented an attempt by Pinudjem, who by this time, had handed the

role of chief priest to his sons, but retained power as a royal figure in Upper Egypt, to

stabilize the situation after the rebellion.13

One further potential connection between the Upper and Lower Egyptian lines is that

the chief priest Psusennes, may be one and the same as the northern king Psusennes

II who is now firmly established as having had an independent reign prior to the

accession of Sheshonq I.14

If the chief priest and king of this name are one and the

same individual it would seem there must have been some kind of agreement

between the two lines that Psusennes would succeed Siamun, and it would also have

united the important office in both Upper and Lower Egypt in the hands of a single

individual. There is no evidence of any chief priest having held office in Thebes after

this point and prior to the installation by Sheshonq I of his son Iuput, suggesting that

Egypt was truly united at this point and the transfer of the governance of the entire

country to Sheshonq I at the start of the Twenty-second Dynasty was peaceful.

This division of the country which characterised the Twenty-first Dynasty was “the

single most important element in Egypt’s political structure in the first millennium

BC”15

and is crucial to an understanding of the political situation in Egypt following

the New Kingdom. This situation was maintained for over a century before the

country was ostensibly reunited under Sheshonq I, founder of the Twenty-second

12

This remains a contentious issue. The possibility that events in Upper Egypt were dated by the

‘reigns’ of the Theban rulers was first proposed by Jansen Winkeln (1992) contrary to the previously

accepted view that all dates from the period related to the Lower Egyptian kings. Kitchen has since

strongly defended the latter position: Kitchen 2009, 191-2. 13

Lull 2009, 244-5. 14

Dodson 2009, 103. 15

Leahy 1990, 155.

xxx

Dynasty, which ruled from the north16

but was also recognised in Thebes. Leahy has

described the situation in the country as follows: in the Delta there was “a patchwork

of small units ruled by chiefs of the Meshwesh and Libu who exercised a varying

degree of autonomy vis-à-vis their royal ‘superiors’ at Bubastis and Tanis” while

“Beyond a general impression of Theban dominance, the internal situation in Upper

Egypt is less clear.”17

What does seem clear is that, unlike during the New Kingdom,

Egypt was not governed as a single unit from a single centre (i.e. Memphis as it had

been for most of Egyptian history).

The model of a divided country with Thebes and the south under the jurisdiction of

an individual as Chief Priest and commander of the armies was, to a certain extent,

retained but this time the northern pharaoh ensured he had overall control of the

country through a clear and deliberate policy of installing trusted family members to

high office in Thebes (see Chapter 3).

II.2 The Twenty-second Dynasty: the reigns of Sheshonq I to Osorkon II

Scholars are agreed in all but the finer details on the reconstruction and dating of the

first few reigns of the Twenty-second Dynasty, specifically that:

Sheshonq I acceded the throne as king ruling from Bubastis in approximately

943 BC;

After a minimum of X years he was succeeded by his son Osorkon I,18

who

ruled for a minimum of 33 years;19

The son of Osorkon I was then either succeeded by his son, Heqakheperre

Setepenre Sheshonq IIa,20

or installed him as a co-regent.21

16

At Bubastis, Tanis or Memphis: Sagrillo 2009, 350-4. 17

Leahy 1990, 155. 18

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 236. 19

Aston 2009, 6-7. 20

Aston 2009, 4-5, 21. The numbering of the kings named ‘Sheshonq’ here follows the resolution

agreed at a conference held in Leiden in October 2007: Broekman et al 2008, 9-10; Kaper 2008, 38-9;

Broekman et al 2009, 444-5. 21

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d.

xxxi

Sheshonq IIa was then succeeded either directly, or after one or two

additional short reigns, of Sheshonqs IIb and IIc,22

by Osorkon II whose

reigned lasted for a minimum of X years.

The northern kings’ control of the south was short-lived however.

From this point, up to the accession of Taharqo,23

penultimate ruler of Dynasty 25

there is still much discussion as to how the evidence should be interpreted. The Piye

Stela provides a snapshot of the political geography of Egypt at the moment of that

king’s invasion, and shows there to have been several kings ruling simultaneously.

Some of the individuals named in the text can be identified in the archaeological

record, however the evidence provides us with the names of more kings than can

easily be placed either in time or geographically. The question then is how many

lines of kings were there at any given point, to which line did each of the kings

attested belong, where was each line based and over what territory did it hold sway.

The Stela shows unambiguously that there were ‘kings’ ruling in Upper Egypt. For

how long, however, had the seat of kings Peftjauawybast at Herakleopolis and

Nimlot at Hermopolis been established, which, if any, of the other kings attested in

the archaeological record were part of lines based in these centres, and were there

other lines, not attested at the time of Piye to which other of the attested individuals

belong? Until recently the accepted view had been that the Upper Egyptian lines had

become established only a very short while before the invasion of Piye, and that

almost all other attested kings belonged either to the Twenty-second Dynasty line of

Sheshonq I and his successors (see above), or to the Twenty-third Dynasty, which,

according to Manetho, consisted of four kings: Patubates, Osorthon, Psammous and

Zet.24

Of the kings attested in the archaeological evidence from this period Kitchen

22

The majority view among specialists of the period is that the praenomina Tutkheperre (Sheshonq

IIb) and Maakheperre (Sheshonq IIc) do represent individual rulers distinct from any of the others

who bore then Sheshonq nomen, and that they should be placed, chronologically, between Osorkon I

and Takeloth I – see notes 12 and 13. Kitchen (2009, 172-3), however, believes Maakheperre and

Tutkheperre to have been nothing more than early praenomina of Hedjkheperre Sheshonq I (this

‘definitive’ prenomen being attested no earlier than his year 5), and that the kings Sheshonq IIb and

IIc should in fact be identified as one and the same as Sheshonq I. 23

There is general agreement that this point remains the earliest securely fixed absolute date in

Egyptian history: Spalinger 1973, 98. 24

Waddell 1940, 161-3.

xxxii

has sought either to identify them as the kings named by Manetho or to add them to

Manetho’s lists on the understanding the latter made mistakes or that the text has

come down to us in corrupted form. Both lines continued down to the time of Piye

and were represented on the stela by Osorkon of Bubastis (of the Twenty-second

Dynasty) and Iuput of Leontopolis (the Twenty-third Dynasty). This was the

reconstruction published in Kitchen’s masterpiece synthesis volume, The Third

Intermediate Period.25

However, a series of articles published from the 1980s

onwards cast doubt on this interpretation; these argued that several of the kings

attested archeologically, in some cases representing several members of a lineal

succession, did not form part of either of the two main Delta lines as they are attested

exclusively in Upper Egypt, and formed part of an independent line(s) which held

sway in Upper Egypt only, of which the Upper Egyptian rulers of the Piye stela may

also have been a part.

II.3 The independent, Upper Egyptian lines

Spencer and Spencer noted in 1986 that there was no evidence to link the kings of

Kitchen’s Twenty-third Dynasty with the Delta: their monuments came exclusively

from Upper Egypt and they were not recognised in Memphis, which lay between the

location of their monuments and their supposed base.26

Leahy expanded on this idea

this to provide a dramatically revised reconstruction of the lines of kings and the

location of the seat of power in each case. Following a hypothesis already put

forward by Priese27

and Baer28

independently, he proposed that the core of Kitchen’s

Twenty-third Dynasty were rulers of a Theban line, and that the remaining rulers

represented the successors of the Bubastite Twenty-second Dynasty rulers and not an

‘offshoot’ ruling contemporaneously with them.29

This is now the majority view

among specialists in the history of the period, however there remain scholars

committed to Kitchen’s interpretation including Kitchen himself, and there is still

considerable scope for revision of the detail of each interpretation. The main features

25

Kitchen 1986. 26

Spencer and Spencer 1986, 198-201. 27

Priese 1970, 20, n. 23. 28

Baer 1973, 11-12, 15-23. 29

Leahy 1990, 179.

xxxiii

of each of the two interpretations are summarised in the following tables (see tables

0.3 and 0.4).

II.4 Takeloth II

The origin, family connections and seat of power of Hedjkheperre Setepenre

Takeloth II Siese have been much discussed. In Kitchen’s reconstruction this

individual was part of the Bubastite Twenty-second Dynasty as the direct successor

to Osorkon II.30

Aston, however, noted that Takeloth II is only attested in Upper

Egypt, he has the epithet nTr Hq3 W3st, his family reveal no connections to Upper

Egypt, and genealogical evidence suggests he flourished a generation after the death

of Osorkon II.31

Kitchen’s counter-arguments have been summarised by Jansen-

Winkeln but rejected.32

The ‘Chronicle of Prince Osorkon’ provides an account of events which took place

over a thirty-year period in Upper Egypt, beginning in Takeloth’s eleventh year,

when his son, the eponymous Chief Priest of Amun, Osorkon (B) made a ceremonial

visit to Karnak.33

The text, supplemented by other sources, provides a detailed

account of the struggle for supremacy in Thebes between two rival factions, each

headed by a ‘king’ and their chosen Chief Priest of Amun. The upper hand seems to

have passed back and forth between the two factions on several occasions, but

ultimately it was Takeloth II’s line that would emerge triumphant,

The events described in the ‘Chronicle’ are dated by the reigns of Takeloth II and

Sheshonq III. If they ruled in succession as Kitchen proposes however there would

be a twenty-year gap in the narrative during which no events are described. However

if the two kings reigned not successively but concurrently there would be no such

gap – year 1 of Sheshonq III would be equivalent to year 4 of Takeloth II, and the

change would be explained by the trasfer of authority in Upper Egypt from the line

of Sheshonq III to that of Takeloth II. Furthermore, Prince Osorkon B of the

‘Chronicle’, son of Takeloth II has now been identified with king Usermaatre

30

Kitchen 1986, 107 31

Aston 1989, 139-53 32

Jansen Winkeln 2006b, 242-3. 33

Caminos 1958, 17

xxxiv

Setepenamun Osorkon III; the two were therefore part of the same line running

parallel to that of Sheshonq III, and not attested in the Delta.

The interpretation of the evidence for the political landscape of Egypt from the reign

of Osorkon II onwards is crucial as it raises a number of important issues concerning

the importance of Thebes and other regional centres particularly in Upper Egypt, the

situation at the time the Kushites became influential and beyond, and more generally

the administrative and governmental structure of the country in the centuries

following the New Kingdom.

II.5 The situation in the years leading up to the establishment of Kushite rule in

Upper Egypt

The Piye Stela shows that Piye was in charge at Thebes by the time of his campaign,

but at what point did the Kushites take control of the city, and what was the nature

and extent of this control and of their presence in Thebes?

Osorkon III ruled for 28 years and Takeloth III. At approximately the same time,

Osorkon installed a daughter Shepenwepet (I) as God’s Wife of Amun, a position

which had existed since the beginning of the New Kingdom but took on a new

significance from this time (see Chapter 3).

Usermaatre Setepenamun Osorkon III ruled for 28 years,34

oversaw the installation

of his daughter as God’s Wife of Amun, and consolidated his control of the south by

the appointment of a son, Takeloth, as Chief Priest. Takeloth would succeed his

father becoming king Usermaatre Setepenre Takeloth III after a brief co-regency

between the two, of 5 years. The situation following the reign of Takeloth III is less

clear. Several further Upper Egyptian kings are known: Rudamun, Hedjkheperre

Sheshonq VIa Siese, Peftjauawybast, Nimlot and Iny.35

At some point during or after the reign of Takeloth III the Kushites, under Kashta or

Piye, assumed control of Thebes. Up to this point, Upper Egypt, probably from

34

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 252. 35

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 253.

xxxv

Herakleopolis and perhaps further south, was controlled by Osorkon III and Takeloth

III. As the Kushites expanded their territory northwards however, the area formerly

controlled by Osorkon and Takeloth was reduced and those listed above who may

have succeeded Takeloth III were either based elsewhere (principally Hermopolis or

Herakleopolis) and/or were only pretenders to authority in Thebes, in opposition to

the Kushites. It is unclear therefore to what extent these individuals formed part of a

single line or indeed whether they bore any relation to one another at all. Rudamun

was a brother of Takeloth III, and Peftjauawybast a son-in-law of Rudamun.

However Rudamun is more closely connected with Hermopolis than any other

centre,36

Peftjauawybast was in charge of Herakleopolis at the time of Piye’s

campaign. Peftjauawybast was contemporary with Nimlot, ruler of Hermopolis at the

time of the campaign. In other words, individuals with connections to the line of

Osorkon III were to be found at both Herakleopolis and Hermopolis at the time of the

campaign, and neither was recognized at Thebes by this point, so the political

geography of the region had changed dramatically by this time.

The existence of Sheshonq VIa Siese was recognized recently by G. Broekman37

and

this individual is considered to have been a successor of Takeloth III, assuming the

throne from the latter either directly,38

or following Rudamun.39

Iny was clearly

attested at Thebes to a regnal year 540

but is thought by Aston to have reigned after

the campaign of Piye.41

The Piye stela narrative implies that Thebes was already within the control of the

Kushites by the time of Piye’s invasion. The events leading to this remain obscure

however and we are reliant on scraps of evidence for the processes involved.

The earliest known ruler in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty sequence is Alara, whose name

is mentioned in texts of later periods, once as the father of Tabiry, a wife of Piye.42

His name was written in a cartouche and he was given the epithet ‘son of Ra’

36

Perdu 2002, 169-70. 37

Broekman 2002, 163-78. 38

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 255. 39

Aston 2009, 24. 40

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 255. 41

Aston 2009, 19-20, 24-5. 42

Eide et al 1994, 41.

xxxvi

indicating that he was regarded as a traditional Egyptian king, although there is no

evidence that his influence was felt in Egypt itself. The presence of his successor

Kashta at Elephantine is, however, attested by a fragmentary dedication stela naming

him as the ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt, and ‘Lord of the Two Lands’.43

Furthermore, circumstantial evidence suggests that Thebes may have been brought

under Kushite control during his reign. In continuation of the tradition of establishing

family members in prominent positions, Osorkon III had established his daughter

Shepenwepet (I) as ‘God’s Wife of Amun,’ a position which took on new

significance at this point. The subsequent establishment of Kashta’s daughter

Amenirdis (I) as the heiress to Shepenwepet can only have occurred after the

Kushites had begun to exert some influence at Thebes and may even have marked

the moment of the transfer of authority, as it would almost a century later when

Nitocris, the daughter of Psamtek I, was adopted as heiress to the God’s Wife,

signaling the transfer of Theban allegiance to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty kings (see

Chapter 4). On the basis that in every other recorded instance the heiress to the God’s

Wife was installed by her father,44

it seems most likely that this occurred during

Kashta’s reign.45

Until recently, a double-dated inscription in the Wadi Gasus had been taken to

commemorate the transfer of power in Thebes from the line of Osorkon III to the

Kushites. The inscription gives the names of Shepenwepet I and Amunirdis I each of

which is accompanied by a date, year 19 in the case of the former, and 12 in the

latter. The 12th

year was thought to be that of the reign of Piye, and the 19th

that of a

king of Osorkon III’s line, which had been interpreted to mean that the inscription

commemorated the transfer of authority in Thebes to Piye in his year 12, several

years before his campaign.46

However, it has now been demonstrated that the

inscription is not the work of a single hand, and that the names and dates may have

43

Ritner 2009, 459-60. 44

Morkot 1999, 195-6. 45

The decoration on some blocks inscribed for Piye and discovered in the Mut enclosure at Karnak,

has been thought to represent the arrival of the Amunirdis in Thebes, in Piye’s year 5, to be installed

as heiress to the God’s Wife Shepenwepet. However some doubt has now been shed on this

interpretation. O. Perdu has convincingly shown that what had been read as a year date is in fact part

of a list of commodities relating to Nubian ochre; the interpretation that the scenes might show the

arrival of the princess is based only on their similarity with those of the adoption of Nitocris at the

beginning of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, which is not sufficient to be convincing. The question of

when the princess was installed in Thebes remains open therefore. Perdu 2010, 151-7. 46

Aston and Taylor 1989, 144.

xxxvii

been written at different times. It cannot therefore be used to fix the relative positions

of the reigns of any kings of this time.47

The region certainly seems to have been under the control of the Kushites by the time

of Piye’s invasion, since no ruler is mentioned in Thebes itself and it is likely that by

this time Osorkon III’s line may have been represented either by Peftjauawybast of

Herakleopolis or Nimlot of Hermopolis,48

but the nature of the relationship of the

Kushites to this and other local centres at this point remains unclear.

II.6 Fragmentation by the time of Piye’s conquest

In the final years of the Libyan Period it seems the Twenty-second Dynasty of

Manetho was succeeded directly, at Tanis and Bubastis, by his Twenty-third

Dynasty, of whom a Petubastis and Osorkon (IV) can be identified in the

archaeological and textual evidence. At this time Egypt, and particularly the Delta

had become fragmented, and Sais, in the western Delta, had become an important

centre. Its ruler, Tefnakht, also controlled a series of principalities in the western

Delta, and had taken charge of Memphis and begun to expand into Upper Egypt,

besieging the town of Herakleopolis and subduing those further south towards

Hermopolis. Hermopolis itself had by this point been brought under the control of

the Kushite king, Piye, whose base at this time was at Napata in Sudan. The

submission of Hermopolis to Tefnakht’s forces prompted Piye to take action. His

troops were able only to arrest Tefnakht’s progress and so Piye himself journeyed

north to join the battle. Hermopolis was reclaimed, and the Kushites then continued

north conquering a series of towns in the Nile Valley, and ultimately, after a bloody

battle, Memphis itself. From here Piye proceeded to the Delta where he received the

submission of various rulers and finally Tefnakht himself.

II.7 Piye Stela

The conquest of Egypt by Piye provides an anchor point. The text begins with a

report relayed to Piye, certainly residing south of Thebes at this point, probably in

47

Jurman 2006, 88-9. 48

Aston and Taylor 1989, 145.

xxxviii

Napata, that Tefnakht of Sais had taken control of the western Delta and Upper

Egypt as far south as Hermopolis, and was besieging Herakleopolis although he had

not yet been able to break through its defences. The text then contains a plea from

“these chiefs, counts and generals who were in their cities” who ask Piye if he has

been “silent so as to ignore Upper Egypt and the nomes of the residence”,49

implying

that they – presumably the governors of the towns already mentioned as having been

taken by Tefnakht – were at least aware that Piye might be able to liberate them, or

even possibly that he already had some responsibility to them.50

Piye then decides to

take action and calls on “the counts and generals who are in Egypt, the commander

Pawerem, and the commander Lamersekny, and every commander of His Majesty

who was in Egypt”, again implying that Piye already had a series of allies in the

country, to prepare to engage Tefnkaht’s forces, and dispatched an army, presumably

from somewhere south of Thebes as Piye is very careful to ensure that his troops stop

there to pay homage to Amun in Thebes on their way.51

Piye himself joined the army

in besieging Hermopolis which eventually surrendered, apparently acknowledging

him as the king of Lower Egypt (bity) at this point.52

Nimlot subsequently claims “I

am one of the kings servants who pays taxes to the treasury as daily offerings. Make

a reckoning of their taxes. I have provided far more than they”53

implying that he had

already(?) been paying taxes to Piye, as had others among the local rulers who had

subsequently joined Tefnakht. Piye subsequently sailed north to Memphis which he

took by force, and then proceeded to Heliopolis and on to the Delta where Tefnakht

armies were eventually forced to surrender.54

The names and titles of the various local rulers mentioned in the stela is summarised

in the following table:

Table II.3. List of rulers named in the Piye Stela text. References are taken from the

lunette (Ritner 2009, 467-8) and two sections in the main text: lines 17-20 (Ritner

2009, 479-80) and 114 (Ritner 2009, 488-9). The main titles are as follows:

49

Ritner 2009, 478. 50

An alternative interpretation of the text however suggests that it was only a single individual, the

army general (singular) who made the appeal to Piye: Goedicke 1998, 17-18. 51

Ritner 2009, 478-9. 52

Ritner 2009, 481, 491, n. 12. 53

Ritner 2009, 482. 54

Lines 123-4-: Ritner 2009, 489-90.

xxxix

Chief of the Ma wr n Ma

Great Chief of the Ma wr a3 n Ma

King nsw

Herditary Prince iry-pat

General imy-r mSa

Count H3ty-a

Name Title(s)

Location Lunette Lines 17-20 Line 114

Akanosh The Great Chief of

the Ma

X

Djedamuniuefankh The Great Chief of

the Ma,

X

Nimlot King X

Osorkon IV King, King Iuput

II,

X

Padiese The Hereditary

Prince

X

Pamai Count X

Patjenfy Count X

Peftjauawybast King X

Every plume

wearing chief who

was in Lower

Egypt

X

Bakennefy The army of the

hereditary prince

X

Djedamuniuefankh Great Chief of the

Ma, of

Mendes X

Nimlot King

X

Osorkon IV King who was in Bubastis and in the district of

Ranefer

X

Sheshonq Chief of the Ma of Busiris X

Tefnakht Great Chief of the West, the ruler of estates of

Lower Egypt, the prophet of

Neith, Lady of Sais, the

setem-priest of Ptah,

X

Akanosh Count in Sebennytos, in Iseopolis

(Behbeit el-Hagar) and

X

xl

Diospolis Inferior

Ankhhor His eldest son, the

General in

Hermopolis Parva X

Djedamuniuefankh Count in Mendes and the Granary of

Re

X

Djedkhiu Count in Khentnefer X

Horbes Count in the estate of Sakhmet, Lady

of Eset, and the estate of

Sakhmet, Lady of Rahesu

X

Iuput (II) King in Leontopolis (Tell Moqdam)

and Taan

X

Nakhthornashenu Count and Chief of

the Ma, in

Pergerer X

Nesnaiu Count and Chief of

the Ma, in

Hesebu X

Osorkon IV King in Bubastis and in the district of

Ranefer

X

Pabasa Count in Babylon (Old Cairo) and in

Atar el-Nabi

X

Padihorsomtus Prophet of Horus, Lord of Letopolis

(Ausim)

X

Pamai Count and chief of

the Ma, in

Busiris X

Patjenfy Count and Chief of

the Ma, in

Saft el-Henneh and in the

Granary of Memphis

X

Pentabekhnet Chief of the Ma X

Pentaweret Chief of the Ma X

The stela text is revealing in several ways. The inscription provides the names and

titles of various local rulers, and the areas they governed. Most had joined Tefnakht’s

alliance (willingly or otherwise), but one, Peftjauawybast of Herakleopolis, was loyal

to Piye throughout. The text also implies:

That those who were kings were ultimately treated as the equals of the other

rulers in submitting to Piye, although they were also singled out particularly

at the end of the narrative when they arrive to pay homage to Piye;

That Egypt at least as far north as Thebes was already under the control

(meaning?) of the Kushites at this point;

xli

That the Kushites had an ally as far north as Herakleopolis and may have

controlled the entire territory northwards to that point prior to Tefnakht’s

advance.

It also provides some indication of the motivations of the Kushites in establishing

themselves as overlords of Egypt. The repeated mention of the bounty carried off by

the Kushites from each locality is clear indication that this presented at least a fringe

benefit for Piye even if it was not the central reason for the campaign i.e. restoring

the tribute already paid by the various towns. Piye is not explicit in condemning the

claims of Nimlot et al to kingship indeed the composer of the text was careful to

ensure they were referred to as kings, and there is no mention of Piye having revoked

their royal status at any point. Indeed it has been suggested that certain of these

kings, especially, Nimlot and Peftjauawybast may even have been installed by the

Kushites;55

this seems not impossible and would certainly fit with Piye’s claim made

some years before the campaign in the text of the ‘sandstone stela’ from Gebel

Barkal in which he claims that

“The one to whom I say: ‘You are chief,’ he becomes chief. The whom

I say: ‘You are not chief,’ he does not become chief. Amon in Thebes

appointed me to be ruler in Egypt. The one [to whom] I say: ‘Appear

(as king),’ he appears. The] one to whom I say: ‘Do not appear,’ he

does not appear.”56

The stela also provides information as to what was important to Piye (or at least what

he should be seen to consider important) e.g. the observance of ritual at important

cult centres such as Thebes, Hermopolis, Memphis, Heliopolis and Athribis, the

proper treatment of horses, circumcision as an indicator of purity, abstention from

eating fish.

It should not necessarily be taken necessarily to indicate that:

The Kushites were from that point on established as rulers over all Egypt;

55

Morkot 2009, 20. 56

Ritner 2009, 463.

xlii

That claimants to the kingship ceased their claims;

That they and other local rulers were no longer able to operate independently,

without the approval of the Kushites;

That any lasting change with regard to political or administrative structures

had been effected;

It is crucial however for our interpretation of the archaeological and textual evidence,

particularly in exploding the idea that there ought only to be one king at a time. It

also suggests that Egypt was ‘fragmented’ at this time, but this idea is underpinned

by the assumption that at other times there was one ruler of the country and that all

other local governors etc. were equal and subservient to him, while at this point the

country was entirely divided into small units ruled at a local level. In reality at this

time and at others the situation was perhaps somewhere in between. The apparent

equality of the other rulers (with the exceptions of Peftjauawybast, Nimlot and

Tefnakht) as shown in the lunette of the stela and in the general treatment in the text

should perhaps be questioned: Tefnakht seems to have been pre-eminently

influential, if only by dint of military supremacy, but was not a ‘king’ at this point.

To what extent did the use by more than one individual of a particular title (king,

great chief) imply equality of influence etc.? Without the Piye stela we might still

conclude that there was a degree of fragmentation in Egypt, due to the number of

kings attested in the archaeological record (showing Manetho to have been aware of

the situation in part only, at best) and other sources such the ‘Chron of Prince Os’,

and Rassam text. We would be much less clear about the extent of the situation

however.

The stela provides a ‘snapshot’ of the situation at one particular moment, and that at

that time the political situation in the country was dramatically at odds with the

conventional picture of the nation united under pharaoh. The stela implies that this

situation was brought to an end by the invasion but this is not necessarily the case; it

also gives no information as to how long this had been the situation. The history of

Egypt in the period following the New Kingdom helps to explain how the events

described in the text came about.

xliii

II.8 The date of Piye’s campaign and events following it

Piye’s campaign is thought to have taken place in approximately his 20th

year.57

There is little evidence of any activity having been undertaken by Piye in Egypt

following the campaign and it has been assumed that he returned to Napata never to

set foot in Egypt again.58

The stela text makes it clear that Piye took away much

booty (‘the ships were loaded with silver, gold, copper, clothing and everything of

Lower Egypt, every product of Syria, every incense pellet of god’s land’59

), and

much of this may have been used in the embellishment of the Amun temple at

Napata where the stela was set up, and on which most of Piye’s energies would seem

to have been devoted in the remaining years of his reign. He was buried at El-Kurru.

Before proceeding to narrate the sequence of events following Piye’s campaign it is

necessary to establish a chronological framework. Piye’s highest attested regnal date

is year 24,60

however he it is likely that he reigned into a thirty-first year.

Tefnakht of Sais was not given the title of ‘king’ at the time of the campaign

according to the stela, but rather ‘Chief of the West, count and chief in Behbeit el-

Hagar (wr n Imnt H3ty-a wr m Ntr),61

however this same individual appears as a king

in his eighth regnal year on two stelae.62

If the stela text is correct in not giving the

royal title to Tefnakht, he must have become king only after Piye’s campaign.

Tefnakht appears to have been succeeded as king of Sais by Bakenrenef, whose

name appears on several stelae from the Serapeum with a regnal date of year 6. This

date relates to the burial of an Apis bull which is also commemorated by an

inscription dated to the second year of the reign of Shabaqo.

57

The main text begins with the date ‘Regnal year 21, first month of inundation’ (Ritner 2009, 477),

the first day of the new year, and it is assumed that the events described in the following lines

occurred shortly beforehand. 58

Morkot 2000, 198. 59

Ritner 2009, 490. 60

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 262. 61

Ritner 2009, 468, 478. 62

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 262, n. 193. The identification of king Shepses-Re Tefnakht with the

Tefnakht encountered by Piye has recently been challenged however: Perdu 2002, 1215-44; see also

Kahn 2009, 139-48.

xliv

On this basis Tefankht’s 8-year reign and the first five of Bakenrenef’s must be fitted

into the last years of the reign of Piye, following the campaign, giving Piye a

minimum reign length of 31 years, giving a period of approximately 11 years during

which Kushite presence in Egypt was minimal. Piye was succeeded by another son

of Kashta, Shabaqo, who engaged in a similar campaign against a group of Delta

kinglets to his predecessor, probably in his second year.

The assumption of royal titulary by Tefnkaht and Bakenrenef and the recognition of

the latter at Memphis demonstrates that in the relatively short period following

Piye’s triumphant return to Napata the dominance of Sais over the Delta and beyond,

to Memphis at least, was quickly restored. There is no evidence that Bakenrenef had

made any move into the territory beyond Memphis, e.g. to Herakleopolis, but

nonetheless, it is not surprising that Shabaqo moved quickly to restore Kushite

authority in the North of the country. No Egyptian account of this survives but

Manetho tells us that it was Shabaqo who, “taking Bocchoris (Bakenrenef) captive,

burned him alive…”,63

and a commemorative scarab now in Toronto records that

Shabaqo had “slain those who had rebelled against him in the South and the North,

and in every foreign country. The Sand-Dwellers who rebelled against him are fallen

down through fear of him, They come of themselves as prisoners.”64

The reference to

‘Sand-Dwellers’ may indicate a consolidation of security at Egypt’s borders in Sinai,

illustrating that Shabaqo’s influence extended right across northern Egypt, and this is

confirmed by donation stelae inscribed with his name from Pharbaithos, Bubastis and

Buto.65

II.9 Absolute Chronology

The sequence of Twenty-fifth dynasty rulers is as follows: Kashta, Piye, Shabaqo,

Shebitqo, Taharqo, Tantamani. The earliest fixed point in Egyptian history is agreed

to be 690 BC, the date of accession of Taharqo, whose reign ended in his twenty-

seventh year, in 664 BC.66

Shebitqo’s reign therefore came to an end in 690. The

63

Waddell 1940, 169. 64

Eide et al 1994, 124. 65

Eide et al 2004, 125. 66

Spalinger 1973, 98.

xlv

highest known regnal date for Shebitqo is 367

however his name appears in an

Assyrian inscription at Tang-I Var which appears to demonstrate that he was on the

throne as early as 706 BC, giving him a much longer reign than the highest date

would suggest and pushing back the reigns of his predecessors.68

The highest attested regnal date for Shabaqo is 14. On the basis that Shebitqo had

succeeded Shabaqo no later than 706, Shabaqo must have acceded the throne no later

than 719 BC.

For some time, scholars were agreed that 712 BC represented a terminus post quem

for the campaign undertaken by Shabaqo. In this year Yamani of Ashdod, (in Israel)

rebelling against Assyrian rule, contacted an Egyptian pharaoh for assistance.69

This

pharaoh sent no aid, Yamani was defeated and fled through Egypt arriving at the

border with Kush, and was eventually returned to the Assyrian King, by the king of

Kush. Shabaka’s invasion of Egypt (and removal of local kinglets) was thought to

have fallen between Yamani’s appeal, and his flight, as despite his appeal to an

Egyptian pharaoh, he apparently encountered none during his journey through

Egypt,70

supposedly because Shabaqo’s invasion had removed the last remaining

Delta kinglets who had continued to exercise authority even after the campaign of

Piye. Evidence for contact between Egypt and its neighbors in the years leading up to

712 suggest that Egyptian pharaohs were present but provide no evidence of the

Kushite overlords. In order to solve this problem several scholars have suggested that

Shebitqo may have ruled as a co-regent with Shabaqo, allowing for Shabaqo’s

accession to have fallen after Yamani’s appeal while accepting that Shebitqo was in

charge in Kush as early as a few years later. There is however no evidence for a co-

regency, and the continuing presence of rulers recognized by the Assyrians as

Egyptian kings later in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty71

suggests it is possible these kings

remained and were indeed in contact with Yamani.

67

Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 258 68

G. Frame, “The Inscription of Sargon II at Tang-I Var” Orientalia 68, (1999), 54. 69

D. B. Redford, “Sais and the Kushite Invasions of the Eighth Century B.C. “ JARCE 22 (1985), 6. 70

L. Depuydt disputes this: “The date of Piye’s campaign and the chronology of the Twenty-fifth

Dynasty”, JEA 79 (1993), 272. 71

Twenty local rulers who were established or confirmed in power by the Assyrian Emperor

Esarhaddon in 671, and reappointed by Ashurbanipal a few years later, are named in the Assyrian

records. Of these, six can be identified: Necho of Sais, Bakennefi of Athribis, Pakruru of Pispodu,

Sehetepibre Pedubast in Tanis, Nespamedu in Thinis and Montuemhat in Thebes: Leahy 1979, 31-9.

xlvi

In summary Shebitqo came to the throne no later than 706 BC and Shabaqo no later

than 719 BC. If Piye’s reign continued into his 31st year the campaign of year 20

would have taken place in approximately 731 BC.

II.10 Shabaqo

Shabaqo was a son of Kashta and brother to Amunirdis I.72

His defeat of Bakenrenef

seems to have had a more lasting effect than Piye’s defeat of Tefnakht: Bakenrenef is

the only king of the Twenty-fourth dynasty according to Manetho. Significantly,

rather than returning to Napata, Shabaqo may have established his residence at

Memphis73

allowing him more easily to retain control of the whole of Egypt: a series

of inscriptions mentioning his name and fragmentary evidence of minor buildings in

the area attests to his presence ,74

and the ‘Memphite Theology’ which was inscribed

on a block of stone now in the British Museum dating to the reign of Shabaqo and

emphasizes the importance of Memphis as ‘the balance of the two lands’,75

may be

taken as further indication of the importance of this location to the king at this time.

As well as the building at Memphis the new king’s reign also saw the beginning of a

programme of monumental renewal, embellishment and construction at several

Theban temples making the Kushite presence visible for the first time, and reviving

the image of the city’s monuments.

Shabaqo also seems to have been more involved in direct relations with international

contacts in the Near East, perhaps cause or effect of his establishment of a residence

in Memphis. According to Kahn in 720 his commander met the Assyrian forces in a

pitched battle at Raphiah and, according to Assyrian accounts, was defeated.76

II.11 Shebitqo

72

Morkot 2000, 205. 73

As is asserted in Morkot 2000, 205. 74

Jurman 2009, 122-3. 75

Morkot 2000, 217-8. 76

Kahn 2006, 251. As has been pointed out by Jansen-Winkeln however, the Nubian troops involved

may have been mercenaries and not in the service of the Kushite king: Jansen-Winkeln 2006d, 260,

n.174.

xlvii

In contrast to his predecessor, evidence for the activities of Shebitqo in Egypt is

sparse. Manetho asserted that he was a son of Shabaqo.77

On the basis of the theory

of brother succession which has been applied to the Kushite royal line, it has also

been suggested that he was a son of Piye and elder brother of Taharqo, but as has

recently been argued by Morkot78

and Kahn79

it seems more likely that in this case

Manetho was correct.

Very few inscriptions dating to Shebitqo’s reign are known. Karnak Nile Level text

no. 33 was inscribed in his year 3,80

the highest known, and he also built a chapel by

the sacred lake at Karnak81

and enlarged, with Amunirdis I, the chapel of Osiris

Heqa-Djet also at Karnak,82

and his name was inscribed on the southern exterior wall

of the Luxor temple.83

The head of a seated statue and unattributed block have also

been found at Memphis,84

which may also have been Shebitqo’s main residence.85

II.12 Taharqo

Shebitqo was succeeded by Taharqo, a son of Piye about whom we know more than

we do about any of the other Kushite kings. Kawa stela V tells us that Taharqa

“received the crown in Memphis”. His years 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 19, 21, 24 and 26 are

securely attested, and his names appears on monuments found throughout Egypt and

Nubia.86

By this point the Kushites were well established in Egypt. Monuments in the name of

Shabaqo particularly and also Shebitqo could be found throughout the country, and

the Libyan princess Shepenwepet I had been succeeded as God’s Wife of Amun by

77

Waddell 1940, 169. 78

Morkot 2000, 223-4. 79

Kahn 2005, 160. 80

Eide et al 1994, 128-9. 81

Ritner 2009, 501-5. 82

Leclant 1965, 47-54. 83

Leclant 1965, 139-40 84

PM II.ii, 837, 839. 85

Aston (2009, 24) states that Shebitqo chose Memphis as his capital late in his reign and Broekman

et al (2009, ix) that “During the 25th

Dynasty Shebitku and Taharqa made Memphis their seat of

residence, so there is no debate about that.” Though no evidence is provided in either case. 86

Dallibor 2005, 203-32.

xlviii

the Kushite princess Amunirdis I during the reign of Shebitqo at the latest.87

There

would be no significant external threat to the Kushite regime until the second half of

Taharqo’s reign (see below) and there is no evidence of any internal uprising of the

kind quelled by Piye and Shabaqo. The construction of the series of large private

tombs belonging to officials such as Karakhamun may also have begun by this

point,88

and would continue during the reign of Taharqo.

Piye had clearly not ousted any of the local rulers at the time of his campaign, instead

preferring to retain them as loyal vassals. It is reasonable to assume that Shabaqo

pursued a similar policy with the exception of his execution of the Saite ruler

Bakenrenef, and that similar measures had been taken from at least as early as the

rule of Piye onwards in Thebes. Our knowledge of the officials of the Theban region

in the period leading up to the Kushite conquest and thereafter is extensive and

discussed in more detail below. It is clear however that several key appointments

were made, in some cases disrupting the existing system in which many of the most

prominent offices were held successively by members of a small number of

prominent families. Although precise dates for the installation of these individuals

elude us, it is notable that in addition to the God’s Wife Amunirdis and her adoptive

heiress, the daughter of Piye, Shepenwepet II, the office of Chief Priest of Amun

would be given to a son of Shabaqo, Haremakhet, and that of Second Priest to a son

of Taharqo, Nesshutefnut.

The network of sanctuaries dedicated to Amun on both sides of the Nile in Thebes

was added to and renewed during the Kushite Period and probably reached a peak of

splendour during the reign of Taharqo. It was along the processional route leading to

the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri that the very largest private tombs of the

Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Dynasties were built, beginning with the tomb of

Harwa, construction of which was probably underway at the beginning of the reign

of Taharqo.

87

She appears as the living God’s Wife alongside representations of Shebitqo in the chapel of Osiris

Heqa-Djet at Karnak: Leclant 1965, 47-54, Ayad 2009a, 18. See also Ayad 2009b, 29-49. See also

Chapter 4. 88

Pischikova 2008, 187.

xlix

The second half of the reign of Taharqo saw Kushite rule significantly weakened by

the Assyrians. During the first two decades of the 7th

century BC Egypt and the

Assyrian Empire seem to have been at peace, but in 679 BC Sennacherib’s successor

Esarhaddon undertook a campaign in the south-western part of the empire to restore

Assyrian control of the Levantine region, eliminating Kushite influence there in the

process. In 677-6 BC Esarhaddon quelled a rebellion in the Levant after which his

grip on the region was secure, nonetheless the Assyrian Emperor seems to have felt

that the only way to prevent permanently the Kushites from reasserting themselves

was to invade Egypt and to drive them southwards away from the Egyptian border.

The Assyrians were defeated in a battle on Egyptian soil in 673 BC, but returned

more successfully in 671 BC when Memphis was sacked, Taharqo wounded and his

son and brothers captured. The Assyrians then quickly imposed a tribute and

appointed governors to rule as Assyrian vassals.89

After this point, Kushite influence was reduced. Assyrian texts suggest that Taharqo

was still perceived as being a threat by the Assyrians, and he is listed as one of three

main enemies to the west of the Empire, in late 671 BC / early 670 BC. However, it

seems that he had lost control of the Delta after the invasion of 671 BC, to Necho of

Sais, who ruled western Lower Egypt, and Sarruludari, who ruled the East.

Another text of 671-669 BC suggests that an Assyrian envoy, whom it was planned

would journey to Egypt, was faced with the threat of attack from Necho, Sarruludari

and/or the other vassals, suggesting that regardless of Taharqo’s relationship with the

vassals they were certainly not loyal to the Assyrians at this time. The situation in the

Delta was undoubtedly different to that in Thebes, but this is nonetheless interesting

for the light it sheds on the relationship of the Kushites to local rulers.

Esarhaddon died on his way to Egypt in 669 BC. The next Assyrian intervention in

Egypt took place in 668/7 BC, as a reaction to Taharqo’s reestablishment in Egypt.

The Assyrian forces defeated Taharqo at Kar Banite (the location of which has yet to

be identified), Taharqo fled from Memphis and the Assyrians then travelled upriver

to Thebes, but the sources do not record what happened there. A stela from Karnak

89

See n. 71.

l

records a victory of Taharqo’s in the Theban area, but does not state the enemy was

the Assyrians.90

During this invasion of 667 BC or immediately thereafter a rebellion

against the Assyrians was planned by Necho, Sarruludari and Paqrer. The conspiracy

was discovered and the rebellion quelled leading to the punishment of several Delta

rulers. For some reason Necho was reinstalled at Sais and his son NabuSezibanni,

commonly identified with Psamtek I, was given charge of Athribis. The Delta then

remained in the hands of the Assyrians but Taharqo never lost at Thebes and

continued to be recognised there until 665 BC.

Without more evidence for the precise dates at which the monuments of Taharqo, the

God’s Wives, and Montuemhat were constructed it is impossible to know whether

there was a clear trend away from building in the name of the king to initiatives of

others but we might speculate that the Assyrian recognition of Montuemhat signified

a shift in the balance of power at Thebes and perhaps more widely. Nonetheless that

Taharqo continued to be recognized in Thebes is not in doubt as is confirmed by a

sandstone stela commemorating the restoration of the enclosure wall of the Amun

complex at Karnak in his year 24.91

After this point Taharqo died and was replaced by Tanwetamani who, according to

the Dream Stela, marched northwards to reassert Kushite rule over the country. He

reconquered Memphis and shortly thereafter received the submission of the Delta

rulers, and killed the Assyrian ally Necho. Tanwetamani was ultimately defeated

however, either by Ashurbanipal or by Psamtek I. The Assyrians pursued him to

Thebes which they then sacked. Tanwetamani continued to be recognised at Thebes

beyond this point.92

However, Papyrus Rylands IX suggests that a non-royal

individual, Pediese, the ‘Master of Shipping,’ was in control of the region from

Psamtek’s year 4.93

90

Kahn 2006, 259, n. 52. 91

Spencer, P, ‘Digging Diary 2006-2007’ EA 31 (2007), 26. 92

See e.g. the date of year 9 on a genealogical inscription from the temple of Luxor: Vittmann 1983,

351. 93

Pressl 1998, 66.