Rebounding Trauma: Representations, Polemic and Critique of Abraham’s Trial of Sacrificial...

Transcript of Rebounding Trauma: Representations, Polemic and Critique of Abraham’s Trial of Sacrificial...

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

1

Sacred Violence: Abraham and Isaac in Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling and Derrida’s

Gift of Death.

This essay explores Abraham’s trial of self, faith and the question of religious sacrificial

violence through the nexus of three texts: Genesis 22, S øren Kierkegaard’s Fear and

Trembling and Jacques Derrida’s Gift of Death. First, I establish the foundation for a critique

of the story which draws on the tradition of dramatic representations of the harrowing tale

as it has been rendered in Genesis 22. In foreshadowing the central concerns of the essay, I

pursue the traumatic trace of the terror of the story, negotiating modernity’s ‘enlightened’

critique of the text as well as other responses in its long history of reception. In the second

section, I confront the aporetics of the ‘teleological suspension of the ethical’ and other

paradoxes of the philosophical implications of Abraham’s test through a reading of

Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. Finally, I close with a discussion of Derrida’s Gift of Death

which extends and complicates the notions of responsibility and the relationship to the

Other.

I

Rebounding Trauma: Representations, Polemic and Critique of Abraham’s Trial of Sacrificial Violence

The reading, interpretation, and tradition of the sacrifice are themselves sites of bloody, holocaustic sacrifice. Isaac’s sacrifice continues every day. Countless machines of death wage a war that has no front.

Jacques Derrida, Gift of Death

That the foundational Biblical sacrifice of Isaac should be withheld by the staying hand of an

Angel is only partial assuagement of the essential terror of the act. The trauma of Abraham’s

trial and secret is passed on through the fulfilment of the Promise of the Covenant of God’s

chosen people, perpetuated and inherited as the figure of Abraham becomes enshrined as

Patriarch and Father of the Judaic, Christian and Islamic Faiths. The ordeal of faith,

obedience and latent sacrifice rebounds1 in outbreaks of terror and reawakens in later

generations the inherited fascination, fear and horror of sacrificial violence. The trace is to

be found in the Cave of the Patriarch’s massacre in Hebron in 1994 and in Muhammad

Atta’s final text before the attack on September 11th 2001.

As if spellbound by the shock of the dreadful impending slaughter, the dramatic

moment in which Abraham is stopped from carrying out the brutal act is the focus of many

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

2

artistic representations of Genesis 22, including Caravaggio’s The Sacrifice of Isaac (1603)

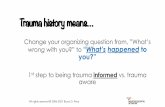

and Rembrandt’s The Angel Prevents the Sacrifice of Isaac (1635). In Caravaggio’s work (see

fig. 1) the three faces emerging from the chiaroscuro of a darkly illuminated and secluded

Mount Moriah are locked in a suspended moment of awful yet redemptive peripeteia. The

timely intervention of the angel points across to the ram and grabs Abraham’s hand which

brandishes the knife as he prepares to execute God’s commanded sacrifice. As deus ex

machina, the half figure of the Angel suggests not only swift appearance and an almost

cinematographic quality of sweeping motion, but emphasises the Divine transcendent

source of the rescue in which a “certain implied ‘outside’ or ‘beyond’ of the painting is

somehow required for its successful operation” (Fried 165).

Fig. 1 Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da . The Sacrifice of Isaac. 1603. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

The same abrupt moment of transition is rendered in Rembrandt’s version (see fig. 2). The

Angel, also portrayed dynamically, appears from the heavens with raised hand preventing

the offering. Like a deflected sword of Damocles rendered useless, the blade is dropped in

mid-air as if to intensify the immediacy of the interruption.

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

3

Fig. 2 Rembrandt, Harmensz van Rijn. The Angel Prevents the Sacrifice of Isaac. 1635. Hermitage, St.

Petersburg.

In both works the drama of the event is conveyed through the hands and the face. Both

artists render the human hand as cruel, forceful and tensed with vicious power. In contrast

to Abraham’s, Isaac’s bound hands are noticeably out of sight emphasising his passive status

as a defenceless victim. Caravaggio’s Abraham grips the knife whilst holding Isaac down with

his fingers digging into his son’s cheek; whilst Rembrandt’s Abraham smothers Isaac’s face in

a gesture which is both an act of violent suppression and an inability to acknowledge the

immensity of the monstrous act. In Caravaggio’s painting it is Isaac’s contorted face in a

breathless and soundless scream of agony and terror which is the haunting facial focus of

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

4

the painting; whereas Rembrandt concentrates on Abraham, who he depicts cruelly

awakened, overwhelmed by shock, guilt and humiliation in the sudden anagnorisis in which

he seems to have realised the dreadful nature of his task. If the face is the locus of the call

for recognition to care for the Other and this is embodied in a face to face recognition of the

Other’s infinite and unconditional demand for responsibility,2 then both paintings reflect the

powerful distortions of the ethical import of God’s commandment which demands a savage

effacement of Isaac’s pain. Thus, whilst portraying closely Isaac’s expressive features of

silent protest, Caravaggio overshadows the potential pity of fear with the authoritarian

figure of Abraham who dominates the picture and by virtue of a spatia l contiguity

juxtaposes the Ram as sacrificial substitute. For Rembrandt, the faceless face is just as

traumatic in its dehumanisation and the figure of the naked torso of Isaac is an exposed

vulnerable site of torture. Both Abraham figures, caught in media res, are torn between the

responsibility of familial sympathy and values, represented by Caravaggio through the sunlit

castle as distant oikos, and the shadowy, uncanny and sublime space of sacrifice on top of

an isolated and wooded Mount Moriah to which God directed Abraham.

Indeed the dramatic suspension in these scenes in which Abraham is caught

between his commanded course of action and the epiphany of salvation capture the tragic

nature and unique literary quality of the narrative in Genesis 22. In many respects the story

exhibits the hallmarks of an Aristotelian notion of tragedy – albeit the “worst” and most

“shocking” one of the most “morally repulsive character” in which the protagonist “knows

what [he] is doing but hold[s] off and [does]not perform the act” (Mleynek 108-109). The

Akedah is a paradoxical tragic familial bind without the culminating horrific murder or

sacrifice, yet in a fundamental way Abraham’s resolve to commit the deed still invokes tragic

terror and pity. Abraham’s “intentionality is itself sufficient to violate the taboo against

violence directed toward blood relations and sufficient as well to generate psychic if not

physical injury” (110). If anything the unresolved, withheld and uncompleted violence

remains as a perpetual threat and prevents catharsis. Thus, whilst the Covenant is fulfilled

and generations are engendered making Abraham the progenitor of a dynastic patrimony,

nevertheless, recessively, the obsession and terror seeds spiritual, ethical and philosophical

anguish.

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

5

Manifest in both these artistic depictions is the heightened ‘tyrannical’ or

‘autocratic’ realism in which Eric Auerbach’s has described the epic quality of biblical

storytelling which leaves many of the details of the narrative shrouded in obscurity and

mystery whilst pointing to the “overwhelming suspense [which] robs us of pure emotional

freedom, to turn our intellectual and spiritual powers [...] in one direction” (11). Emerging

from the depths and the darkness of the canvas, then, is the incomprehensible voice of God

manifest in the Angel and present in the flash of light illuminating, yet veiling, the secret,

inscrutable mystery of character and situation. The canvas/text “fraught with background”

fuses a heightened sense of “reality” manifest in the fleeting moment of psychological and

spiritual torment with the hidden resonance of an over-determined “second, concealed

meaning” invoking a universal-historical judgement (15). Thus, with so much resistant to

comprehension yet demanding engagement in which “[d]octrine and promise are

incarnate” and the knowledge of God as a “hidden God”, we are subject to and overcome by

the need for meaning and interpretation (15).

It is significant that Caravaggio and Rembrandt have chosen this suspenseful

moment in their rendering of Genesis 22. Faced with the inexplicable cruelty of God’s test,

the trauma and horror of God’s demand is allayed in a depiction of the moment of salvation.

The ‘traditional’ interpretation, seeking to ameliorate the moral implications of a God who

seems to have condoned and commanded child sacrifice, tends to place the emphasis on

the strength of Abraham’s faith and obedience to God, and, of course, God’s ultimate

control and intervention and blessing – once Abraham has proved his faith. In Levinas’s

ethical reading (contra Kierkegaard), this final movement of the narrative is the crescendo

of the entire story:

Abraham’s attentiveness to the voice that led him back to the ethical order, in

forbidding him to perform a human sacrifice, is the highest point in the drama. That

he obeyed the first voice is astonishing; that he had sufficient distance with respect

to that obedience to hear the second voice – that is the essential. (77)

The capacity of the story to shock and appal, however, has become part of an enlightened

modernity’s repudiation of a barbaric, vengeful and malevolent monotheistic God. To Kant,

whose grounding of ethical injunctions was in a rational categorical imperative, the story

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

6

was anathema. Kant casts doubt on the veracity of the voice of God entirely, and argues

that if the voice “commands [one] to do something contrary to the moral law”, then, “no

matter how majestic the apparition may be [one] must consider it an illusion” (Kant 115).

Clearly, Kant has the story of Abraham “butchering and burning his only son at God’s

command” in the forefront of his mind and in a footnote he explains,

Abraham should have replied to this supposedly divine voice: “That I ought not to kill

my good son is quite certain. But that you, this apparition, are God – of that I am not

certain, and never can be, not even is [sic] this voice rings down to me from (visible)

heaven.” (115)

More recently, the story, which seems to invoke a supreme terror justifying slaughter of

innocents or indicative of a long outworn creed of primitive rituals such as blood sacrifice, is

grist to the New Atheist mill:3

A modern moralist cannot help but wonder how a child could ever recover from such

psychological trauma. By the standards of modern morality, this disgraceful story is

an example simultaneously of child abuse, bullying in two asymmetrical power

relationships, and the first recorded use of the Nuremberg defence: ‘I was only

obeying orders.’ (Dawkins 242)

Such contemporary responses to the story, however, in their attack on the Old Testament

God-as-Stanley-Milgram and, particularly perversely, the dutiful Patriarch-as-Adolf-

Eichmann, inform a wider self-assured disavowal of religion and an attempt to locate and

appropriate critique in the realm of modern rational discourse which represents “man's

emergence from his self-imposed nonage” (Kant n.pag.). Furthermore, exacerbated by the

horrific acts of terror which understandably invoke extreme responses, the discourse

surrounding religion and violence is caught between the tempering reformist yearning for a

safe return to ‘pure’ religion and the strident secularist who calls to expunge society of

religion, fundamentalist or not. Abraham has become a potent and divisive figure in this

conflict: on the one hand, idealistically referred to as the Father of the monotheistic

religions of the Book and looked to as an all-embracing figure for inter-faith reconciliation;

on the other, as the epitome of total obedience to a divine sanction of brutal violence which

condones suicide and indiscriminate killing regardless of universal human values. As an

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

7

“easily identifiable agent”, Abraham has become the “symbol of subjective violence” who is

“the biblical equivalent of the suicide bomber” (Sherwood n.pag.). 4 In an effort to simplify

and rationalise the complex ‘aetiology’ of terrorist activity, this symbolic figure becomes a

popular means to focus anger and recrimination. The figure of Abraham gets embroiled in a

wider net of ideological conflicts and the elements of the story take on new resonances: as

the paradigm case of irrational Islamic religious fundamentalism opposed to Western

rationality, multicultural tolerance and peaceful coexistence.5 This polarised polemic is

transposed at the end of history into a new configuration of an old Cold War binary: the

“clash of civilisations” in which the “resurgence of parochial identities” i.e. rogue radical

Islamic states are at war against the “secular West” (Juergensmeyer qtd. in Cavanaugh 7-8).

The result of such ideological double speak is a hypocrisy which creates a dangerous

double standard between concepts of ‘good violence’ (rationalised use of calculated and

necessary means of force for the realisation of civilising secular ends) and ‘bad violence’

(indiscriminate evil acts of terror). Far from containing violence, the double bind produces

violence and exacerbates and further entrenches conflict. Thus, Sherwood’s contention is

that both these “incommensurable” and “naive” positions distance and displace violence to

the margins or to the “outside”, either in terms of fringe groups of religious fundamentalism

or in terms of the self-justified requirements of threatened secularism. In all this the

corollary of the ideological project is either to privatise belief removing it from the public

sphere or to “shed the old spectre of religion (conceived of as an archaic site of

submissiveness, passivity, heteronomy – therefore danger)” as this is the means, or “the

surest way of salvation, making safe” (Sherwood n.pag.). Apart from replicating overly

simplistic and even false, intransigent binary oppositions between categories with com plex

socio-political and historical realities, such generalisations obscure the hidden, secretive

collusion of ‘religious’ thinking within secular modernity. Thus, injunctions justifying

violence emanate from a new Mount Moriah invoking the metaphysical vertigo of the

sacred terror of ‘Democracy’ and ‘Freedom’. The discourse thereby deflects, distracts and

occludes the complex and entangled complicity of the secular state in acts of systemic or

structural violence.

What is exceptional in the stark opposition of the religious/secular and modernity’s

claim to sole prerogative of critique is the elision of the long history of internal debate

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

8

within religious traditions which have wrestled with problems of violence. Sherwood’s work

points to the continued presence of ambivalent and troubled responses to the Abraham

story in all three religions of the Book. That these responses are “impossible to map onto

modern understandings of religion and religious identity” suggests that far from subsuming

critique into a modern subjectivity which inevitably assumes a ‘separation’ or ‘distance’

from the Holy text and which itself becomes part of a self-constituting choice of religious

identification, religion has within it rigorous self-criticism (Sherwood n.pag.). As such,

“[c]ries of horror or recoil (an act of critique avant la letter) combine seamlessly with

fervent affirmation or embrace” (Sherwood n.pag.). Critique is not tied to the

overburdening machinations of political choices of religious identity but it is in fact “un-

bound”; acts of audacious, nuanced critique and interpretation re-bound throughout the

history of Biblical exegesis.

Instead of “being unequivocal scripts for actions” and simply condoning or passively

excusing sacrificial violence, Biblical scholars have problematised Genesis 22 in “giving rise

to multiply inflected acts of writing and performance for which the implications are legion”

(Sherwood n.pag.). Contradictions and inconsistencies abound at the level of the text itself.

Omri Boehm argues that “whatever the apparent clarity of this narrative, the formulation of

its style and composition is quite elusive” (2). He points to the evidence of interpolation and

redaction which in effect renders the stylistic and structural nature of the Angel’s second

speech suspect and inconsistent with the rest of the text. Suffice to say, without exploring

the intricacies of the debate, one may note that Boehm suggests an opening of an “inner-

biblical polemic” especially concentrated on the “issue of disobeying a manifestly illegal

order” (3). Boehm will ingeniously, and perhaps somewhat tendentiously, argue that the

first angelic intervention is timed to focus on Abraham’s obedience which in fact has never

been certain, whilst the second angelic speech corroborates and confirms an assumed

obedience with the blessings of a Chosen People’s lineage. Furthermore, in an even more

audacious, but for our purposes instructive rhetorical move, Boehm attempts to use these

inconsistencies in order to question our common assumption about Abraham’s obedience

and willingness to sacrifice Isaac. Using Auerbach’s observation of unexplained background,

Boehm cites other scholars who have perceived amidst the silence and darkness a possibility

to ‘redeem’ Abraham and, therefore, point to “confusions and hesitations which could

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

9

presage disobedience” (10). J. Miles claims that “Abraham resists even as he goes through

the motions of compliance”, and, but for the Angel’s interruption and the later redactions,

“we never learn whether he would actually gone through with the sacrifice” (qtd. in Boehm

10-11).

Many of these critical responses may seem counterintuitive, nevertheless, they

strike a chord with the image of Abraham as dissenter, daring and bravely protesting against

a wrathful God’s intention to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 18. 22-33. In contrast

to Kierkegaard’s reading of Abraham, Susan Neiman, in her book defending Enlightenment’s

Moral Clarity, valorises Abraham’s “resolute universalism” which expresses concern not only

for neighbours, but Sodom and Gomorrah’s unknown “innocents” who are “abstract and

nameless” and for whose lives Abraham is forthright enough to bargain (3-4). Thus, contrary

to Genesis 22, Abraham emerges as a moral hero who, despite having the “tone of a

merchant”, nonetheless has the “mind of a moralist” and is courageous enough to argue in

the face the Divine sanction and “instincts of self-preservation” – thereby presenting a

laudable and calculated case against the “criminal action [of] collateral damage” (Neiman 3).

Levinas highlights this aspect when he criticises Kierkegaard for ignoring the dialogue which

illustrates a life-affirming sense of responsibility towards the Other despite or in the face of

death:

Abraham is fully aware of his nothingness and mortality. [...] But death is powerless

over the finite life that receives a meaning from an infinite responsibility, a

fundamental diacony constituting the subjectivity of the subject, which is totally a

tension toward the other. (74, 77)

These are not isolated instances of attempts to rehabilitate and rationalise away a

potentially devastating prescription to sacrifice intrinsic human values at Divine command.

Sherwood’s study of Judaic Midrash’s conversations, variations and additions to the story,

the “dampening [and] muting of sacrifice in the Qur’an”, and the eschatological and/or

typological lines of Christian theodicy culminating in the fulfilment of the willing sacrifice of

Jesus Christ as Lamb of God, all reveal an ongoing and obsessive need to cope with the

“recoil” of the “major ethical wound” or rupture the sacrificial violence presents. In

qualifying sacrifice to ‘sacrifice’ such theological endeavours inform a self-conscious quest

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

10

to “bring the patriarchal out-law back within the law and to lower these extreme,

mountaintop events down to a safer, more human(e) place” (n.pag.).

Perhaps, one could offer a more ‘comedic’ anthropological and psychoanalytic

interpretation of the story, one which stresses the fact that the narrative was always written

après-coup and was integral to the genesis and self-mythology of an emergent yet

embattled group adopting a unique monotheistic God. Here, God the Father with the power

of the Symbolic Law (manifested in the prescription to kill or not to kill) and the Real

(manifest in the revelations and epiphanies) behind his injunction, uses or co-opts archaic,

yet widely prevalent practices of child-sacrifice in order to test Abraham.6 As a patriarch of a

tribe which was no different from many others still immersed in a zeitgeist which condoned

ritual killings, there could be no more fitting trial of faith to differentiate the group from

idolatrous Others. In a transformative process of sublation and substitutive oblation, a new

code is internalised and dramatically enacted in the narrative of Genesis 22. Thus, the fear

and awe of the numinous and traumatic closeness to death is retained, but repressed or

sublimated in a tie of subservience, guilt and responsibility which will be fulfilled in the

Covenant – essentially a new religious-ethical order which demands allegiance to the One

God and a reward of lineage and patrimony for the One Chosen People. This dynamic is akin

to the epochal movements in the history of responsibility described by Jan Patočka between

the orgiastic mystery incorporated by Platonism, and the latter subsequently repressed by

the Christian mysterium tremendum. In delineating this process almost as a law in an

economy of exchange, Jacques Derrida provides an explanation of the conversion which also

centres on sacrifice and secrecy:

The logic of this conservative rupture resembles the economy of a sacrifice that

keeps what it gives up. Sometimes it reminds one of the economy of sublation

[relève] or Aufhebung, and other times, less contradictory than it seems, of a logic of

repression that still retains what is denied, surpassed, buried. Repression doesn’t

destroy, it displaces something from one place to another within the system. (8)

In a further application of psychoanalytic terms, through a series of complex identifications

between Abraham simultaneously as father (to Isaac) and son (to God), the story enacts and

regulates the machinations of ambivalent parental feelings of love and hatred towards

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

11

offspring. In this vein, Vincent W. Wynne has argued that the story and its various

developments in rabbinical Midrash reflects a psychodynamic conflict between a

particularly narcissistic paternal God’s secondary investment of narcissistic libido as it is

internalised in an ideal image which in turn is donated to the child. The story represents a

revolt against such tyrannical representations emanating from Yahweh noted for harsh

retributive justice and jealous demands of loyalty. For Wynne, the point of this trial is for

‘bad’ idolatrous parental narcissism to be transcended. Thus, invoking the climax of

Caravaggio and Rembrandt paintings once again, the moment of anagnorisis is given a

different inflection of salvation. This time with the assumed insight of a psychoanalyst

peering into the depths of Abraham’s dark unconscious:

It is only in retrospect that Abraham recognizes that something has changed within

him – that his projected image of Isaac (in the instant that he raised the knife) has

been destroyed, which has the effect of liberating Isaac from the debt of the primary

narcissistic representation. (Wynne 773)

Whether one accepts the thrust of this psychoanalytic interpretation is a moot point, and

there are other more refined and complex transpositions into psychic models. Indeed there

are also other sophisticated anthropological critiques. For example in a feminist exposition,

Carol Delaney has focussed on the near sacrifice as an exclusive exchange between

Abraham and God without Sarah’s knowledge or consent and she highlights the pervasive

subsequent references to seed as essential to the establishment and perpetuation of the

patriarchal order.7 What is significant in any of these accounts, however, is the continued

desire to contain, domesticate and make sense of the rebounding terror inherent in the

potential sacrifice of Isaac. In this regard, the Abraham and Isaac story has shown to be

found at the “very nerve centre of Judaism and Christianity (and Islam)” (Goldin qtd. in

Sherwood n.pag.). Echoing Patočka’s and Derrida’s cryptological or mysto-genealogical

movement of history, the secret of sacred sacrificial violence is never effaced or destroyed;

the “new rise of orgiastic floodwaters” “recurs indefinitely” during moments of revolution,

crisis and conversion, including the space of “Aufklärung and of secularization” (Derrida 21).

The history of sacred initiation and sacrifice expressed in Abraham and Isaac’s trial

continues to present us with a rupture evoking the real threats of outbreaks of violence in

the name of political or religious martyrdom and sacrifice. Thus, there persists in the

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

12

reception of the story the continual attempt to suture the wound of extreme violence which

nonetheless remains open. Isaac’s scream echoes in the historicity of continual suffering

and torture.

II

Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith: Approaching the Limits of Ethics and the Religious

At this extremity stands Abraham. The last stage he loses sight of is infinite resignation. He really does go further and comes to faith

Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling

In the long history of recoil from Genesis 22, we witness attempts to resolve and dissolve

the threat of divinely sanctioned murder/sacrifice. In many of these critiques there is an

adherence to common sense certainty, an appeal to rationality and a system of human

ethical values which allows a denunciation, or at least an accommodation, of the act. Thus,

the invocation of a potential disruptive call to individual acts of justified violence is reigned

in through a multiplicity of ethical systems from Kantian duty (the divine voice of God

relocated into the internalised ‘ought’ of the universalised categorical imperative) to

Hegelian subsuming of the Moralität or individual morality under the Sittlichkeit as a wider,

and again universalised, ethical system grounded in institutionalised law of society and

state.8 Through his method of ‘indirect communication’ embodied in the pseudonym

Johannes de Silentio, 9 who is the purported author of the lyrical dialectic Fear and

Trembling, Søren Kierkegaard stands resolutely and absurdly at the extreme limits of ethical

thought which directly challenges established systems of philosophical enquiry. Indeed, in

critiquing the prevailing rational philosophical dispensation, Kierkegaard castigates the

denigration of the individual to the level of cheap mercantile exchange (Kierkegaard 41).

This informs Kierkegaard’s wider philosophical project to “rethink singularity and

responsibility to otherness, a concept lost in modernity’s preoccupation with objectivity and

possessive individualism” (Jegstrup 425). In problematising the tendency of modern thought

towards abstraction, totalisation and a reduction of human freedom, Kierkegaard will

attempt a dangerous and intriguing recuperation and resuscitation of Abraham as an ethical

hero and exemplar of an existential act of anguish and courageous faith.

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

13

For Johannes de Silentio, more than the elaborate Systems of philosophers such as

Hegel’s Absolute Idealism and World-Spirit, the figure of Abraham is infinitely impossible to

understand. It provokes sleeplessness, anguish, fear and trembling. Alluding to St. Paul’s

Letter to the Philippians (2.12) our spiritual fulfilment depends on our working out our

salvation without guidance, perplexed in fear and trembling in God’s terrifying absence.

Hence, emerging from the ‘fraught background’ or darkness of motivation and meaning,

Silentio ventures to imagine intimately the different possibilities open to Abraham. Using a

musical expression, in his ‘Attunement’ – several different expositions of the story in the

form of a sort of Ignatian Contemplation – Silentio is struck not only by “the finely wrought

fabric of imagination” but more viscerally by the “shudder of thought” (Kierkegaard 44). It is

with thinking at the limits of faith that we confront, in anguish, the abyss of the decision

without recourse to any conceptual System. The bodily paroxysms of thought suggest a

convulsion of horror evoked by an individual existential predicament which deconstructs

safe appeals to universal moral prescriptions. After trying to envisage various alternative

and lesser Abrahams, Johannes de Silentio expresses the deeply troubling and paradoxical

conundrum succinctly:

The ethical expression for what Abraham did is that he was willing to murder Isaac;

the religious expression is that he was willing to sacrifice Isaac; but in this

contradiction lies the very anguish that can indeed make one sleepless; and yet

without that anguish Abraham is not the one he is. (60)

At the heart of the dilemma is a definition of murder opposed to sacrifice which amounts to

a deadly semantic play of consequences threatening enshrined values of the social order.

The justification and/or condemnation of Abraham will depend on the recourse to

seemingly mutually opposed discourses (faith versus Law; individual versus universal; finite

versus infinite) neither of which can be resolved without anguish and horror. For Johannes

de Silentio this is not simply a rhetorical game of sophistry. It is a “two-edged sword,

bringing death and salvation” (61). In fact, as his paradoxical name would suggest, Silentio is

thoroughly ambivalent about language and speech: the public discourse of communication,

especially given the tremendous secret and essentially incommunicable nature of faith, is

articulated with potentially violent consequences. He envisages the real effect of a self-

congratulatory preacher’s sermon valorising Abraham’s sacrifice inspiring a “sinner” to

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

14

confront the truth of the sermon “like a cherub with flaming sword” (59). At every step, the

author reminds us of the gravity of the case before us. He is “virtually annihilated” and

“constantly repulsed” and “paralysed” and when faced with Abraham’s leap of faith he

shrinks in fear (62-3).

In three ‘Problemata’, Silentio goes on to explore and unravel a dizzying series of

contradictions and dilemmas. I will discuss two such instantiations – the knights of

resignation and faith, and the ‘teleological suspension of the ethical’ – in order to show how

Kierkegaard uses the story of Abraham and Isaac to construct an existential approach to

ethics which relies not on abstract reason, but the painful negotiation of a relationship of

responsibility and care for the Other. Ultimately, this is grounded in the immensely

unfathomable “dialectic of faith [which is] the most refined and most remarkable of all

dialectics” before which Johannes de Silentio stops amazed in his attempts to conceptualise

and understand (66).

The first of these formulations works to suggest that Abraham is a ‘Knight of Faith’.

This is made manifest through his obedience to heed the call of God and in his willingness to

sacrifice Isaac, whilst being able to remain with an absurd faith and hope, knowing that he

would receive Isaac back in this life. What makes Abraham distinctive is not simply “infinite

resignation” to the task (66). He is not like any other tragic hero who, confronted with the

dilemma of opposed moral demands and contradictory outcomes, relinquishes freedom to

Fates and a universal tragic order, or submits to the self-abnegation of his finite desires and

attachments sublimating them into an image of transcendental heavenly reward. Rather,

Abraham retains his hopes for earthly fulfilment which are strengthened and remain

resolute despite giving up and ‘losing’ Isaac. Here Kierkegaard is suggesting that the knight

of faith makes a double movement: he gives up claims to the precious entity (whether it is

Abraham’s paternal claims to his beloved son or the example of the lover for his beloved)

and yet at the same time, in the same moment, knows and believes that he receives it back.

Two implications are important. First, this is no philosophy of asceticism or a denial

of finite, transitory joys. Kierkegaard shows that the knight of resignation, though

praiseworthy, acts solely by will, discipline and effort to renounce the finite and set his eyes

on the infinite to the detriment of the finite world. This is easily understandable and

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

15

conceivable. It relies on individual reserves of “strength and energy and freedom of spirit”

(76). It is a “purely philosophical movement” – that means it is rational and driven by power

of the will. However, in his movement of paradoxical faith which demands “on the strength

of the absurd to get everything, to get one’s desire, whole, in full”, the knight of faith has

“more-than-human powers” which confounds conceptual understanding and “dumbfounds”

Silentio making his “brain reel” (76). Thus, in a koan-like doubling, the knight of faith

possesses the secret of kenosis through which he is open to the return of the gift aided by

grace and the absurd power of faith. With no bad faith or malcontent,10 the knight of faith’s

“care for the finite, and ability to dwell in […] the temporal, the immanent, is in no way

diminished” (Lippitt 48, 49). This means that the knight of faith retains a sense of joy amidst

devastation:

He drains in infinite resignation the deep sorrow of existence, he knows the bliss of

infinity, he has felt the pain of renouncing everything, whatever is most precious in

the world, and yet to him finitude tastes just as good as to one who has never known

anything higher, for his remaining in the finite bore no trace of a stunted, anxious

training, and still he has this sense of being secure to take pleasure in it, as though it

were the most certain thing of all. [...] He resigned everything infinitely, and then

took everything back on the strength of the absurd. He is continually making the

movement of infinity, but he makes it with such accuracy and poise that he is

continually getting finitude out of it. (Kierkegaard 69-70)

Second, as a consequence of this glorification of the knight of faith, Kierkegaard values the

individual (particular, subjective) infinitely more than the universal (general, objective). Yet

in the terms of the absurd dialectic, the recognition of an “eternal consciousness” gives the

particular its value – without this there would be despair (49). Embedded in this paradox is

an ethical position which amounts to the refusal to adhere to abstracting or generalising

principles in ethical decisions which do not fully embrace the truth of the unique, finite

particularity of the situation or self. One manifestation of this aspect is Kierkegaard’s

repeated critical emphasis on the notion of calculation – and elsewhere motifs of

bourgeoisie philistinism and economic trade of ideas. In this instance, what marks Abraham

out as a knight of faith is a Keatsian negative capability: he “believed on the strength of the

absurd, for all human calculation had long been suspended” (65). Abraham’s refusal to

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

16

“calculate” represents an anti-utilitarian and an anti-Systematic core to the ethical. In any

ethical decision, especially the most grave, Kierkegaard refuses to reify and enchain the

demands of the infinite. From a rational perspective, with a view towards codes and rules,

this is a supremely vexing disregard for an evaluation of an ethical decision based on

quantifying ends and means in a projection of suitable outcomes aligned with communal

interests. For the knight of faith, the truly courageous, superlative act is in the values of

trust and faith in that inexplicable absurd voice of the Other. Thus, the knight of faith places

the self in a relationship akin to Martin Buber’s I to Thou. Or as Sylvia Crocker suggests, in

his abeyance to the “Infinite and Absolute Person”, the knight of faith “suspends the

working of his will and his natural human tendency to ‘run forward in thought,’” and

thereby finds greatness in the movement towards equanimity and trust in the unknown

determination of God (127-128).

To the commonsense view this illogical absurd faith might be construed as

mystification and a treacherous of abrogation one’s ethical duty. However, it is significant to

note that in his dialectic Kierkegaard is certainly not constructing an ethical edifice to be

systematised and adhered to as an absolute law. Rather, the perplexing implications of

Abraham as a knight of faith are meant to unsettle – even terrorise – established, ossified

rational prescriptions to general and universal truth. Essentially, the text acts as a

corrective11 and a “sceptical, ironical, relativizing attack” on “dogma” (Mooney 100). In

attempting to untie the Gordian knot of the “bold, perverse Kierkegaardian penchant for

paradox”, Edward F. Mooney argues that Fear and Trembling is a lesson in rationalistic

hubris, especially targeted at know-it-all “reasonable, commonsensical, respectable middle-

class inhabitant[s] of Danish Christendom” (100). In this regard, the adherence to faith is

“polemical” in that it

works to counterbalance an easy rationalistic optimism, the idea that by calculation

of benefits and burdens one can arrive at the decision to opt for faith; the idea that

reality can be captured without remainder by some essentially simple conceptual

scheme, with no dark spots before which reason must confess its ignorance [...].

(Mooney 109)

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

17

As if embodying T. S. Eliot’s dictum – “Teach us to care and not to care” (Eliot, ‘Ash

Wednesday’) – Mooney’s argument is that the underlying story concerns “care and

relationship” (101). The greatness of Abraham’s movement lies in his relinquishment of

“proprietary claim [over Isaac] and selfless concern” (107). In putting forward this view,

Mooney is arguing that Kierkegaard’s apparent irrationalism is a matter of appearance from

a position outside faith and as long as he sticks to this John Lippitt remains in sympathy with

the interpretation. Lippitt, however, has contested Mooney’s reading by showing that a

“complex test of care” really does not apply to Abraham’s case (58-59). Certainly this is most

true if we consider Isaac’s point of view: how plausible is Abraham’s selfless care when he is

staring at a glinting knife? Far from a relinquishment of ownership, is not the action of

murder/sacrifice the ultimate claim to ownership over someone’s life and death? Clearly,

Kierkegaard’s text exposes a much more visceral and unsettling dimension to our existential

predicament.

Arguably, the second of the formulations which I would like to discuss –

Kierkegaard’s suspension of the ethical – is also not as easy to explain in terms of an ethic of

care, proprietary rights and selfless concern because it seems to sweep away all appeals to

‘ethics’ and places the locus of the decision in a realm of adherence to an absolute Other

outside the ethical sphere. Pushed to its most extreme limits, the case of Abraham and Isaac

is an exploration of the shadowy liminal possibilities of action beyond ethical discourse.

Kierkegaard locates the heart of this “monstrous paradox” which “no thought can grasp

because faith begins precisely where thinking leaves off” (82) in a terrifying formulation:

For faith is just this paradox, that the single individual is higher that the universal is

justified before the latter, not as subordinate but superior, though in such a way, be

it noted, that it is the single individual who, having been subordinate to the universal

as the particular, now by means of the universal becomes that individual who, as the

particular, stands in an absolute relation to the absolute. (84-85)

This is not just terrifying because of its dialectical complexity, but because it seems to

amount to a suspension of principles grounded in human community and ultimately their

being overridden and rendered subordinate to an excessive command. Thus, in an ‘immoral’

reading of the formulation, Kierkegaard seems to be advocating an unquestionable super -

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

18

ethical obligation to divine command: Abraham must obey God’s command over and above

any other value. Terry Eagleton describes the positions as follows:

The figure of faith like Abraham by-passes the mediation of the ethical, in which all

particulars are indifferently interchangeable, and establishes instead a direct

relationship with the absolute which pitches him beyond the frontiers of ethical

discourse or rational comprehension. [...] It is the ruin of any rational politics.

Individuality is the claim of infinity upon the finite, the mind-shaking mystery that

God has fashioned this irreplaceably specific self from all eternity, that all eternity is

at stake in one’s sheer irreducible self-identity. (45)

This view would complement Levinas’s critique. Kierkegaard misplaces the locus of the

ethical through a conflation of it with the universal or general dictates of socially normative

ethical discourse. One must, however, be careful in answering Kierkegaard’s question as to

“whether there is any ‘higher’ court of appeal than the ethical [...] or an individual’s

responsibilities to a ‘universal’ requirement” with an unqualified affirmation of irrationalism

(Lippitt 89). The complexity of the dialectic demands that there is a relation to the universal,

but that it is not the sole relation. Any ethical system (especially Kantian or Hegelian) which

justifies itself by the subordination or domination of the individual particular into an

abstraction or objectification of identity in a relationship of equivalence (hence the

antipathy towards monetary infiltration in ethical bargaining and calculating) is regarded as

wrongly subsuming telos into the sphere of ethics. Kierkegaard, in portraying Silentio’s

Abraham as an exceptional figure with a sublime unmediated relationship to the absolute,

attempts to reconstruct a position outside the ethical which determines itself not in

absolutist and tyrannical conceptual terms or in a disclosed public discourse of language but

in faith and the intrinsic, uncontested value of the particular. Abraham’s exceptional

position is such that it “cannot be mediated, for all mediation occurs precisely by virtue of

the universal; it remains in all eternity a paradox, inaccessible to thought” (Kierkegaard 89).

The adherence to an inarticulable relationship with God and an “act of purely

personal virtue” which is a proof of faith, demands that he ‘oversteps the ethical’ and enters

into a relation with a higher telos (88). Here Kierkegaard, treads the fine line between the

dilemma of an ethical condemnation of a sociopathic act and a demand for the sanctity of a

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

19

deeply private and inexpressible relation to an absolute. One (safe?) reading of this bold and

unsettling paradox is that Kierkegaard is attempting not to justify acts of heinous terror, but

to insist on an origin for values which does not reside in the self-constructed human finite

ethical; he seeks a Justice outside the common ethical conceptual instantiations which

remains an ineffable possibility of pure unmediated relation with an absolute Other.

Furthermore, this renders possible readings of the text as a parable of individualism against

the conformism of Hegelian ethics – or even a wider totalitarian oppressive subordination of

the individual to the will of the collective.12 Thus, perhaps bizarrely considering the violence

of Abraham’s act, the action is given its own credence and authority by residing in an absurd

faith that God would not allow Isaac’s death, despite having commanded it. So, then

Abraham becomes the quintessential existential hero in his appeal to a higher Law.

Strangely, as a progenitor of Meursault rather than Eichmann, Silentio’s Abraham

represents an extreme embodiment of an individual who challenges the claims of family,

society and community. Nevertheless, whatever may be gained, such a philosophical

position runs the risk of being lost in the terror of irresponsibility. Silentio, is alive to these

objections and in quoting the stark demands of Luke 14.16 he is exposing the sacrificial

limits and demands of the religious life. He thereby is dissecting the anguish and difficulty of

the task of being an individual with an absolute duty to God (99-103).

In conclusion, one may regard the aporetics of the text not as a solution to problems

of ethics and its relation to the Absolute, but an exacerbation of them which seeks

constantly to unsettle and traumatise the individual – lest a quiescent moral torpor settle.

The playful irony of authorship is a testament to the contradictions inherent in confession

and as such destabilises the very notions of authority and translation of the specificity of the

call to answer in an authentic response-able being. What emerges from a reading of Fear

and Trembling, then, is a plurality of views which circle endlessly around the problem of

answerability and responsibility. Thus, whether we agree with R. M. Green’s assessment of

the text as a “theological shock treatment” (qtd. in Lippitt 140) or Edward F. Mooney’s

rehabilitation of the text by propounding an ethic of care, selfless love and receptivity, the

trauma of the act – sacrifice of Self and Other – is held is dramatic suspension, in a dialectic

without being resolved. Silentio’s perpetual bafflement is not merely propensity towards

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

20

irrationalism and obfuscation, but a product of the very existential crisis in which any

individual finds him/herself when faced not only with Genesis 22, but all ethical actions.

III

CODA: Derrida’s Gift of Death

It speaks to us of the paradoxical truth of our responsibility and of our relation to the gift of death of each instant. [...] It stands for Jews, Christians, Muslims, but also for everyone else, for every other in its relation to

the wholly other.

Jacques Derrida, The Gift of Death

For Derrida, in his reading of Kierkegaard and Genesis 22, the aporetics of responsibility,

secrecy, guilt and sacrifice are the central traumas which rebound in violence of trembling –

an unknown agitation of bodily “symptomalogy [..] as enigmatic as tears” (55). This “strange

repetition ties us to an irrefutable past (a shock has been felt, a traumatism has already

affected us) to a future that cannot be anticipated and which is repeated in its affliction”

(54). The trauma abounds and contaminates all ethical relations – indeed, Derrida’s

masterful dissection is a dissemination of the lines of influence which are traced back

towards not an origin of guilt or sin, but certainly a “common treasure, the terrifying secret

of the mysterium tremendum that is a property of all three so-called religions of the Book,

the religions of the races of Abraham” (64). This mysterium tremendum is transmitted as a

secret repressed significance through epochs (Platonic or Christian or even secular) in a

complex interrelationship between sacrifice and the gift of death. Invoking the trembling,

terror of the sacred which is “nothing other than death itself, a new significance for death, a

new apprehension of death, a new way in which to give oneself death or to put oneself to

death” (31), Derrida explicates the experience of sacred violence as:

The gift made to me by God as he holds me in his gaze and in his hand while

remaining inaccessible to me, the terribly dissymmetrical gift of the mysterium

tremendum only allows me to respond and only arouses me to the responsibility it

gives me by making a gift of death [en me donnant la mort], giving the secret of

death. (33)

The core of the paradoxical logic of the gift of death resides uneasily in a secretive collusion

between the demands of God as the absolute Other with which absolute irreplaceable

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

21

individuality is inextricably entwined and the call of responsibility to the duty of the general

which seems to undermine the very foundation of unique finite being. Derrida extends

Kierkegaard’s ‘suspension of the ethical’ to all acts, to relations of the individual with all

other others. He posits a paradox of irresponsibility, and even madness, within the

responsible decision. The aporia of responsibility ultimately stems from the radical

dissymmetry of the singularity of the finite mortal and his/her responsibility (read

Abraham’s response to the Absolute) and the annihilating yet infinite Goodness of the gift

(read God’s Absolute call which is to be obeyed despite its mystery and secrecy). This

creates an original guilt in which “guilt is inherent in responsibility because responsibility is

always unequal to itself: one is never responsible enough” (51). Thus, Derrida reveals a

“double response or allegiance to the general and the singular, to repetition and to the

unique, to the public sphere and to the secret, to discourse and silence, to giving reasons as

well as to madness, each of which tempts the other” (de Vries 175).

In a formulation that certainly invokes the economic problem of scarcity of resources

(love, time, attention) endemic in Biblical context,13 Derrida reads the sacrifice of Isaac as a

fable of morality itself in that the “absolutes of duty and responsibility presume one

denounce, refute, and transcend, at the same time, all duty, all responsibility, and every

human law” (66). This, however, is not an isolated act of originary ritualised myth, it is an in

which we collude on a daily basis: it is “the most common and everyday experience of

responsibility” (67). Simply put, Derrida ties us in an insoluble contradictory bind of

irresponsible responsibility because by “being responsive and responsible one must, at the

same time, also be irresponsive and irresponsible” (61). By loving and devoting oneself to an

other, we unavoidably deny other others. By valuing the singular, we disregard the general.

By binding “one to the absolute singularity of the other” we are propelled into the “space or

risk of absolute sacrifice” because there are an infinite number of others and an

innumerable generality of others (68). Thus, Derrida writes:

I can respond only to one (or to the One), that is, to the other, by sacrificing the

other to that one. (70)

For Derrida there is something intrinsic and unavoidable about this condition we find

ourselves mired in: it happens as soon as we “enter into a relation with the other, with the

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

22

gaze, look, request, love command, or call of the other” (68). The horror of our finitude and

inadequacy, as well the very limits of the laudable valuation of the particular, “condemns

concepts of duty and responsibility to paradox, scandal and aporia” (68). Like Abraham, we

cannot but betray, sacrifice and offer a gift of death. We must respond by sacrificing ethics

or that which presumes to oblige a sacrifice “in the same way, in the same instant, to all the

others” (68). Mount Moriah is an everywhere.

In conclusion, Derrida’s insights draw us closer to the secret terror of the story of

Abraham and Isaac which now has become a figure not just for terroristic acts of

unjustifiable abomination but an expression of the very economy of ethical sacrifice at the

heart of our moral life. The secret and silent scream of Isaac represents the darkness of a

moral system which is complicit in and perpetuates violence and suffering though it may

attempt to hide or repress such paradoxes and scandals. The knee-jerk reaction which

would easily condemn the story as barbaric belies the monstrous and “monotonous

complacency” of our own “discourses on morality, politics, and the law, and the exercise of

its rights (whether public, private, national or international) (86). This it is for us to realise

that not only is it true that “society participates in this incalculable sacrifice, it actually

organizes it” (86). That Abraham was willing to proceed with his task represents his

disturbing position as “the most moral and the most immoral, the most responsible and the

most irresponsible of men” perhaps makes him a deeply problematic and contradictory

moral hero for our times. In this way, his violent legacy which rebounds and is transmitted

from generation to generation demands our attention.

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

23

ENDNOTES

1 The term ‘rebounds’ is loosely derived from Maurice Bloch’s anthropological study of ritual and violence, Prey

into Hunter: The Politics of Religious Experience (1992). I extend the term to encapsulate a sense of the perpetuation, contamination and ongoing inheritance of structures of sacrificial religious violence ritualised in modern eruptions of terror. 2

This insight is inspired by a reading of Bernhard Waldenfels’s article “Levinas and the Face of the Other.” in The Cambridge Companion to Levinas (2006): p 63-81. See also Slavoj Zizek, “Smashing the Neighbour’s Face.” (Lacan.com n.pag.) 3

In the Afterword to his Letter to a Christian Nation, Sam Harris explicitly refers to blood sacrifice as an example of religious primitivism and barbarism. After a list of such practices all over the world and throughout history, he writes:

It is essential to realize that such obscene misuses of human life have always been explicitly religious. They are the product of what people think they know about invisible gods and goddesses, and of what they manifestly do not know about biology, meteorology, medicine, physics, and a dozen other specific sciences that have more than a little to say about the events in the world that concern them. And it is astride this contemptible history of religious atrocity and scientific ignorance that Christianity now stands as an absurdly unselfconscious apotheosis. The notion that Jesus Christ died for our sins and that his death constitutes a successful propitiation of a ‘loving’ God is a direct and undisguised inheritance of the superstitious bloodletting that has plagued bewildered people throughout history. (Harris n.pag.)

4 See Sherwood, “Binding-Unbinding: Pre-Critical ‘Critique’ in Pre-Modern Jewish, Christian and Islamic

Responses to the ‘Sacrifice’ of Abraham/Ibrahim’s Son.” in her forthcoming book, Biblical Blaspheming: Binding-Unbinding (2012). 5

This connection is not merely rhetoric and it is not made flippantly: Sherwood has pointed to the allusions to Genesis 22 and the contested and charged use of the word dhabaha in the letter found after the ‘9/11’ attacks. Rather than references to any political context the use of religious injunctions is marked: ghazwah (raid); the word for slaughter of animals for ritual sacrifice dhabaha – a term which is an echo of Genesis 22 which in the Qur’an refers to Ibrahim as dhabih allah ‘intended sacrifice of God’; and, the emphasis on sacrifice and obedience. Thus, Sherwood argues that these refer back to the “primal scene of sacrifice” and is a “particularly deviant citation and mutation of the ‘Abrahamic’” (n.pag.). 6

The historical and anthropological evidence pointing to sacrifices is disputed and my reading is certainly contentious. In A History of God Karen Armstrong shows that despite the fact that sacrifice was common in the pagan world, there is no precedence for Isaac’s sacrifice given the promise and gift he represented as well as the very different conception the deity represented (27). Similarly, Geoffrey Hartmann’s response to this line of reasoning by arguing that, “the displacement of human by animal sacrifice was not a burning issue that needed legislation” and that in any case child sacrifice was usually only reverted to in crisis of which he claims there is no “indication” in Genesis (34). Nevertheless, I would counter these claims by pointing towards the prevalence of sacrifice as a foundational act of culture and the persistent ritualistic domestication of modes of sacrifice that use a scapegoat. See my argument later which uses the work of René Girard in this respect. 7

See Carol Delaney, Abraham on Trial: The Social Legacy of Biblical Myth, 1998. 8

See John Lippitt, Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling p 83-87. 9

For the rhetorical implications behind the use of pseudonyms in Kierkegaard’s work see John Lippitt p 8-11. I follow Lippitt in referring to the author of the text as Johannes de Silentio, rather than attributing any idea directly to Kierkegaard and thereby simplifying a complex literary interplay of ironic distance. 10

Kierkegaard offers an exposition of a tax-gatherer (67-70) which perhaps has parallels with Jean-Paul Sartre’s discussion of bad faith and his portrait of the Parisian waiter. 11

For a similar use of the term “corrective” see Lippitt p 144. The term “dialectical corrective” is also offered by Jerry H. Gill in his paper “Faith Is as Faith Does.” (see Perkins, p 205-217). He argues that in fact Kierkegaard’s project is an exercise in reductio ad absurdum where he “juxtaposes an irrationalist view of faith, through de Silentio, to the rationalist view in order to give rise to a higher view” (204). 12

See the discussion of R. M. Green in Lippitt p 144-146. 13

See Regina Schwartz’s discussion of religious violence manifested in the story for Cain and Abel in her book The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism, 1997. Despite arguing for an ethic of plenitude and generosity, she does emphasise that the Old Testament in some respects refers to limitations of blessings and resources which exacerbates this problem of responsibility and giving. Could one counter Derrida’s insistence

Matthew Rumbold Aesthetics & Modernity II

24

on an economic scarcity with reference to an alternate, though perhaps idealised sphere: the infinite nature of maternal love (a mother who does not love any of her children any less) and a creative use of a variety of resources, beyond quantification and (ap) portioning of value. Noticeably, despite a brief passing allusion, women are absent from Derrida’s discussion. For a gendered analysis see Kelly Oliver, “Fatherhood and the Promise of Ethics.” Diacritics 27.1 (Spring 1997): 44-97.

Bibliography

Books

The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha. Eds. Robert Carroll and Stephen Prickett.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Armstrong, Karen. A History of God. London: Vintage Books, 1999.

Auerbach, Eric. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. 50th Anniversary

Edition. Trans. Willard R. Trask. Introduction Edward W. Said. Princeton, N.J.; Oxford:

Princeton University Press, 2003.

Critchley, Simon and Robert Bernasconi, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Levinas. Cambridge; New

York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. London: Bantam Press, 2006.

Derrida, Jacques. The Gift of Death. Trans. David Wills. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Eagleton, Terry. Sweet Violence: The Idea of the Tragic. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

Eliot, T. S. Collected Poems 1909 – 1962. 1963. London: Faber and Faber, 2002.

Fried, Michael. The Moment of Caravaggio. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Hartmann, Geoffrey. The Third Pillar: Essays in Judaic Studies. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Kant, Immanuel. The Conflict of the Faculties. Trans. Mary J. Gregor. Lincoln; London: University of

Nebraska Press, 1979.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Fear and Trembling: A Dialectical Lyric by Johannes de Silentio. Trans. Alastair

Hannay. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Proper Names. Trans. Michael B. Smith. London: Athlone, 1996.

Lippit, John. Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling: Routledge Philosophy Guidebook. London:

Routledge, 2003.

Neiman, Susan. Moral Clarity: A Guide for Grown-Up Idealists. London: Bodley Head, 2009.

Perkins, Robert L., ed. Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling: Critical Appraisals. University, Alabama:

University of Alabama Press, 1980.

Schwartz, Regina M. The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1998.

Sherwood, Yvonne. Biblical Blaspheming: Binding-Unbinding. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2012. Unpublished Forthcoming Book.

de Vries, Hent. Religion and Violence: Philosophical Perspectives from Kant to Derrida. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Articles

Boehm, Omri. “The Binding of Isaac: An Inner-Biblical Polemic on the Question of ‘Disobeying’ a

Manifestly Illegal Order.” Vetus Testamentum. 52.1 (January 2002): p 1-12.

Crocker, Sylvia Fleming. “Sacrifice in Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling.” The Harvard Theological

Review. 68.2 (April 1975): p 125-139.

Gill, Jerry H. “Faith Is As Faith Does.” in. Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling: Critical Appraisals. Ed.

Perkins, Robert L. Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1980: p 205-217.

Jegstrup, Elsebet. “A Questioning of Justice: Kierkegaard, the Postmodern Critique and Political

Theory.” Political Theory. 23.3 (August 1995): p 425-451.

Mleynek, Sherryll. “Abraham, Aristotle, and God: The Poetics of Sacrifice.” Journal of the American

Academy of Religion. 62.1 (Spring 1994): p 107-121.

Mooney, Edward F. “Understanding Abraham: Care, Faith, and the Absurd.” in. Kierkegaard's Fear

and Trembling: Critical Appraisals. Ed. Perkins, Robert L. Alabama: University of Alabama

Press, 1980: p 100-115.

Oliver, Kelly. “Fatherhood and the Promise of Ethics.” Diacritics 27.1 (Spring 1997): 44-97.

Waldenfels, Bernhard. “Levinas and the Face of the Other.” in The Cambridge Companion to Levinas.

Eds. Simon Critchley and Robert Bernasconi. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University

Press, 2002: p 63-81.

Wynne, Vincent W. “Abraham’s Gift: A Psychoanalytic Christology.” Journal of the American

Academy of Religion. 73.3 (September 2005): p 759-780.

Electronic Resources: Articles

Cavanaugh, William T. “Does Religion Cause Violence?” Harvard Divinity Bulletin. 35.2&3

(Spring/Summer 2007): p 1-12. Harvard Divinity School. Web. 17 August 2012.

< http://www.hds.harvard.edu/news-events/harvard-divinity-bulletin/articles/does-religion-

cause-violence>

Goldman, Peter. “Christian Mystery and Responsibility: Gnosticism in Derrida’s The Gift of Death.”

Anthropoetics IV 1 (Spring/Summer 1998).

<http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0401/pg_DERR.html>

Harris, Sam. Letter to a Christian Nation: Afterword. Sam Harris Official Website. Web. 16 August

2012.

< http://www.samharris.org/site/full_text/afterword-to-the-vintage-books-edition/>

Kant, Immanuel. “What is Enlightenment?” University of Columbia. Web. 16 August 2012.

< http://www.columbia.edu/acis/ets/CCREAD/etscc/kant.html>

Zizek, Slavoj. “Smashing the Neighbour’s Face.” Lacan.com. 14 August 2012. Web.

< http://www.lacan.com/zizsmash.htm>

Electronic Resources: Images

Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da . The Sacrifice of Isaac. 1603. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Art

and the Bible. Web. 14 August 2012.

< http://www.artbible.info/art/large/2.html>

Rembrandt, Harmensz. van Rijn. The Angel Prevents the Sacrifice of Isaac. 1635. Hermitage, St.

Petersburg. Art and the Bible. Web. 14 August 2012.

< http://www.artbible.info/art/large/274.html>