Real beyond Realism: the multiple faces of collage in Greek avant-garde art in the 60s and 70s

Transcript of Real beyond Realism: the multiple faces of collage in Greek avant-garde art in the 60s and 70s

964

Ett intresse för det verkliga bortom, och ofta i strid med, realismens estetiska konventioner karakteriserar det gre-kiska avantgardet under 1960- och 70-talen. Detta tar sig inte sällan uttryck i användningen av olika collagetekni-ker. Införlivandet av ”readymade-dokument” i form av tex-ter eller bilder i visuella eller litterära konstverk – i stort sett för första gången i en grekisk kontext – sammanfal-ler både med ett förnyat intresse för politiska, sociala och vardagliga ”verkligheter” och ett övertagande av avantgar-distiska strategier och intressen, såsom integrerandet av liv och konst, hos en ny generation av grekiska författare, konstnärer och filmskapare. I denna presentation har vi samlat ett urval arbeten från olika konstarter, vilka under-söker problematiken kring ett verkligt bortom realismen genom användningen av avantgardetekniker som inter-media-montage och re-inskription av dokument.

HISTORIA OCH TEORIDen grekiska konstens historia är präglad av frånvaron av historiska avantgarderörelser, vilka uteslöts ur den for-malistiska receptionen av modernismen under 1930-talet och dess sammankoppling med ett sökande efter nationell identitet. 1960-talet var i Grekland ett decennium präglat av politisk instabilitet åtföljd av ekonomisk tillväxt och en intensiv modernisering kopplad till statens politiska och ekonomiska beroende av USA. Såren från det grekiska inbördeskriget (1940–1949) behövde alltjämt läkas. I kul-turella termer kom den ”höga” konstens två kanons att etableras av 1930-talets ”modernistgeneration” (idealism) och av den illegala kommunistiska vänstern (social rea-lism). Vid samma tid började dock en ung generation av avantgardekonstnärer att samlas kring alternativa littera-tur-, konst- och filmtidskrifter, där man återupptäckte det historiska avantgardet som sammanfördes med Beat och undergroundkultur. Den instiftade diktaturen 1967 fick denna kulturella blomstring att avstanna. Men motståndet mot diktaturen kom, i några fall, att inspirera till ett anam-mande av avantgardistiska konstformer och praktiker i en politiskt engagerad konst utförd av en ”Ny vänster”.

Under tidigt 1960-tal övergav den grekiska konsten idealismen till såväl form som innehåll. Tio års krig följt av tio års politiskt förtryck hade framkallat tvivel på den referentiella sanningen hos bilder och texter. Yngre konst-närer började rikta sitt intresse mot det vardagliga, det urbana och det privata. De utmanade 1930-talets idealism såväl som den traditionella vänsterns konservativa estetik.

Deras arbete var inte mindre politiskt, men det avvek från den etablerade vanan med uppenbara politiska budskap. Vid decenniets mitt introducerades avantgardistiska tekni-ker och praktiker för (i stort sett) första gången. Interme-diala arbeten, överskridandet av genrer och blandningen av olika diskurser förkroppsligade samtidigt politiska och estetiska val: såsom integrationen av liv och konst, tan-ken på det personliga som politiskt (till exempel genom kvinnors erfarenheter), utmaningen av traditionella kate-goriseringar etc. Det är inte någon tillfällighet att dessa strategier korsar de traditionella gränserna mellan konst-arter. Tekniken eller snarare ”kategorin” collage smälter samman dessa val genom, till exempel, införlivandet i ver-ken av material ur varukultur och urbana miljöer (reklam, pressbilder, etc.) eller av tryckt material som anknyter till ”lägre” textuella diskurser och genrer eller av visuellt do-kumenterad ”muntlighet” i visuella eller textuella collage, i visuell poesi, prosafiktion eller film.

Uppkomsten och spridningen av collagets medium i Grekland bör förbindas med en ny, intensiv undersökning av arvet från dadaism och surrealism. Detta kan även, i sin tur, kopplas till omläsningen av psykoanalys och marxism. Inflytandet från Max Ernsts collageromaner, å ena sidan, och den marxistiska, dialektiska rörelsen i det berlinska fotomontaget, å andra sidan, kan urskiljas i såväl avant-gardepraktiker som i spridningen av en ny visuell kultur i Grekland. Eftersom den politiska dimensionen av dadaism och surrealism undertrycktes av den grekiska modernis-men under 1930-talet, så var detta första gången som det historiska avantgardets politiska engagemang länkades till samtida krav och en samtida politisk situation.

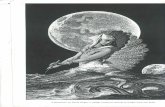

KONSTNÄRERNA OCH VERKENDe första collagen publicerades i tidskriften Pali under tidigt 1960-tal. De collage som gjordes av tidskriftens chef-redaktör, surrealistpoeten Nanos Valaoritis, påverkade av Ernsts collageromaner [fig. 1, 2], visade sig bli inflytelse-rika. Därutöver präglades tidskriftens utseende som så-dant, åtminstone delvis, av en surrealistisk collage-estetik, då den illustrerades av bilder hämtade från gravyrer från artonhundratalet [fig. 3, 4].

Den politiska dimensionen hos surrealismen koppla-des till samtida frågor av de medverkande i Pali; till ex-empel, enligt Valaoritis, den individuella frigörelsen ”från etablerade begränsningar och tabun”. Denna tanke skulle senare få ett radikalt politiskt innehåll i arbetet och tän-

Elena Hamalidi, Maria Nikolopoulou & Rea Walldén ÖVERS. FRÅN ENGELSKAN JESPER OLSSON

DET VERKLIGA BORTOM REALISMEN: COLLAGETS MÅNGA ANSIKTEN I GREKISKT 1960- OCH 70-TALSAVANTGARDE

965

Elena Hamalidi, Maria Nikolopoulou & Rea Walldén

REAL BEYOND REALISM: THE MULTIPLE FACES OF COLLAGE IN GREEK AVANT-GARDE ART IN THE 60S AND 70S

An interest in the real beyond and often against the aes-thetic conventions of realism characterizes the Greek avant-garde art of the 1960s and the 1970s. This is often expressed through different techniques of collage. The incorporation of ready-made “documents” in the form of texts or images into works of visual or literary art, almost for the first time in Greece, coincides both with a renewed interest in political, social and everyday “realities”, as well as with the adoption of avant-garde strategies and inter-ests – such as the integration of life into art – by a new generation of Greek writers, artists and filmmakers. In this presentation, we collect a selection of works from different arts which take part in the problematic of a real beyond realism, using the avant-garde techniques of inter-media montage and document re-inscription.

HISTORY AND THEORYThe history of Greek art is marked by the absence of his-torical avant-gardes, which were excluded by the formalist reception of modernism during the 1930s and its inter-linking with the quest for national identity. The 1960s in Greece were a decade of political instability, accompanied by economic growth and intense modernization connected to the state’s political and economic dependency on the United States. The wounds left by the Greek Civil War (1940–49) had yet to heal. In cultural terms, the two can-ons of “high” art were set by the modernist “Generation of the Thirties” (idealism) and by the illegal Communist Left (social realism). At the same time, a young generation of avant-garde artists started to assemble around alternative literature, art and film magazines, rediscovering the his-torical avant-gardes and bringing them together with the Beat and underground culture. The dictatorship imposed in 1967 interrupted the cultural flourishing. However, the resistance against it, in some cases, inspired the adoption of avant-garde art forms or practices in a politically en-gaged art by a kind of “New Left”.

In the early 1960s, Greek art shifted away from idea-lism both in form and content. Ten years of war, followed by ten years of political oppression, had led to a mistrust of the referential truth of images and texts, which were at the service of opposing ideologies, although realism was still the aesthetic mainstream. Young artists shifted their interest to the everyday, the urban and the private. They challenged the idealism of the 30s, as well as the conser-vative aesthetics of the traditional Left. Their work was no

less political but it deviated from the mainstream habit of overt political messages. By the mid-1960s, avant-garde techniques and practices were introduced (almost) for the first time in Greece. Intermediality, the transgression of genres and the mixing of language discourses embodied simultaneously political and aesthetic choices: such as the integration of life into art, the notion of the personal as political (e.g. women’s experience), the challenge of tra-ditional categorizations etc. It is not by chance that these strategies traverse the traditional borders between the arts. The technique, or rather the “category” of collage fuses these choices together in visual or textual collages, in Vi-sual poetry or prose fiction or film, by the incorporation of urban and commodity culture imagery (ads, press ma-terial), printed matter alluding to “low” textual discourses and genres, visually documented “orality”.

The emergence and diffusion of the medium of collage in Greece should be related to an intense re-examination of the Dadaist and Surrealist legacy. This was also con-nected to the re-reading of psychoanalysis and Marxism. The impact of Max Ernst’s collage novels, on the one hand, and of the Marxist dialectical approach of Berlin photo-montage, on the other, can be recognized in Greek avant-garde practice, as well as in the emergence and diffusion of a new visual culture. The reason for this diffusion was the politicization of the collage practice. Since the political dimension of Dada and Surrealism were suppressed by the Greek Modernism of the 1930s, it was in the 1960s and 1970s that for the first time the political engagement of these historical avant-garde movements was connected to contemporary requests and the current political situation.

THE ARTISTS AND THE WORKSThe first collages appeared in the magazine Pali in the ear-ly 1960s. The collages of the magazine’s main editor, the Surrealist poet Nanos Valaoritis, after Max Ernst’s collage novels [fig. 1, 2], proved to be of some influence. Moreover, the whole magazine was partly imbued with Surrealist col-lage aesthetic, since it was illustrated with images derived from nineteenth-century engravings [fig. 3, 4].

The political dimension of Surrealism was connected to contemporary preoccupations by the contributors to Pali; such as the emancipation of the individual “from the established limitations and taboos”, according to Valaoritis. Further, this notion acquired a radical political content in the thought and work of the anarchist Nikos Balis, who

966

kandet hos anarkisten Nikos Balis, som illustrerade sin egen tidskrift [Mavros Ilios / Svart sol] (1981–1982) med sina egna collage, enligt utsago hämtade från hans – fiktiva – bok med titeln Hommage à Max Ernst [fig. 5].

Trots att kretsen kring Pali förde samman surrealis-men med Beat- och undergroundkulturens samtida uttryck och former, så förblev de relativt bundna till de historiska avantgardena. Likväl skulle en alternativ visuell kultur spira ur detta klimat under 1970-talet. Det första collaget inspirerat av dada återfinns antagligen på en flyer för den ”avantgardistiska” litteraturtidskriften [Lotos / Lo-tus] (1968–1971), utformad av dess utgivare, konstnären och poeten Costis (Triantafyllou) [fig. 6]. Det var dock i Leonidas Christakis tidskrifter som influenserna från det surrealistiska collaget, uppblandade med arvet från det dadaistiska fotomontaget, skulle kombineras med intryck från popkonst eller sådana motkulturella uttryck som teck-nade serier [fig. 7–12].

De första tecknen på denna motkultur kan spåras till-baka till Pali och, bland annat, Panos Koutrouboussis arbe-ten. Redan i hans teckningar från sent 1950-tal förenas det surrealistiska arvet med influenser från tecknade serier i ett slags illustrationer med drag av fantastik, karikatyr och grotesk. Under 1960-talet använder Koutrouboussis colla-get i serier som kombinerar ovan nämnda drag med en fascination för science fiction. Dessa serier, såsom Maschi-nen Reich, koncipierades som enskilda bilder – ett slags måleri, faktiskt – eftersom bilderna aldrig fogades sam-man i ett narrativ [fig. 13–17].

Under 1970-talet blev collaget ett tecken på en poli-tisk identitet och tillhörighet till vänstern. För konstnärer som intresserade sig för det ”verkliga” men ville utmana realismen hos en kommunistisk kanon, blev det berlinska fotomontagets marxism än en gång ett passande medium, och kunde underlätta konstnärers kritik av konsumism och institutionalisering av konsten. De första collagen i denna kontext producerades redan 1965, i Paris, av Chrysa Romanos. I några av sina collage [fig. 18, 19] skulle hon, dialektiskt, sidoordna bilder ur massmedier och konsum-tionskultur med bilder av fattigdom och politisk oro i syfte att problematisera den politiska samtiden. I några fall kon-stituerar de sidoordnade bilderna delar av en konstruk-tion, till exempel en skjutbana på ett nöjesfält eller ett spelbord, och erinrar om vissa popkonstverk, betecknande människans öde inom ramen av en internationell impe-rialistisk politik. I Sidor ur en dagbok från 1973 utnyttjar Romanos intermedialiteten för att introducera personliga eller triviala dokument ur sitt vardagsliv som konstnär: fotografier av henne själv med sin make eller av deras hus på landet, anteckningar och skisser till hennes konstruk-tioner, inköpslistor, kartor, fragment av kuvert och sidor ur en bok.

Den dadaistiska praktiken med dialektiska sidoställ-ningar av fragmenterade bilder ur verkligheten ligger också bakom den kompositionella strukturen hos de nya realisternas målningar under 1970-talet, särskilt hos Jan-nis Psychopedis (som i synnerhet tycks ha tagit intryck av de kritiska realisterna vid galleri Poll i Berlin). I sina målningar och collage samordnar Psychopedis fotojourna-listiskt material ur massmedia med scener ur samtida gre-

kiskt liv – migranter, arbetande människor, politiska de-monstranter som attackeras under diktaturen – eller med bilder approprierade från konstverk i skiftande realistiska stilar. Användningen av dadaistiskt fotomontage i kom-bination med approprieringar tillåter honom att utforska realismens kritiska potential, att samordna olika visuella språk, såväl som att kritisera en tilltagande varufiering och institutionalisering av konsten [fig. 20a–20b].

Under 1970-talet övervann för första gången en del neo-avantgardistiska författare och filmskapare de tidigare strikta generiska och mediala gränserna. Litterära arbeten experimenterade med textuella collage och, till viss del, med intermediala modi, och ifrågasatte den litterära dis-kursens institutionella villkor. Här vill vi i första hand lyfta fram texter som exploaterar ett visuellt register.

I Michael Mitras visuella poesi blandas receptionen av en fotomontagets marxistiska tradition med (försenade) influenser från poesia visiva och konkret poesi i en prak-tik som vill förena konsten med livspraxis. I sin To Alo-thi tis Perigrafis (Deskriptionens alibi, 1976) [fig. 21–28], bygger Mitras på visuella kontraster mellan massmediala bilder och texter, reklam, foton av mekaniska detaljer och urbana landskap, tryckt material med skiftande typsnitt (som emellanåt anspelar på specifika hög- eller låglitterära genrer), handskrifter, diagram, olika språk (journalistiskt, teknokratiskt, byråkratiskt) och, slutligen, kontrasten mel-lan skriftligt och muntligt. Därigenom syftar han inte till att dialektiskt producera ny mening, utan, enligt hans eget manifest [fig. 29], till att undergräva den litterära institu-tionen genom att öppna det litterära språket för vardag-liga och populärkulturella erfarenheter, och för läsaren. Mitras prosatexter [fig. 30] utforskade också gränserna för berättandet genom användningen av triviala element och genom införlivandet av skiftande koder (till exempel tra-fikskyltar) i texterna.

1976 vänder sig också poeten Costis (Triantafyllou) till den visuella poesin i en gest av ”utsuddande”, vilken vi-sualiserar författarens skrivkramp. I Silence. Le poème ce trouve sur le ruban [fig. 31] använder han – i stället för att göra sig av med det – skrivmaskinens färgband som ett slags palimpsest som bär på spåren av hans skrivande på en ”bränd”, tom sida, som han beskriver det. Detta slags collage konceptualiserades som ett ”tyst” vittnesmål om skrivprocessen och komponerades genom en samordning av antiteser (färgbandets och den brända sidans materiali-tet mot den konceptuella dimension av frånvaro och tom-het som visualiserades av den vita sidan; svart mot vitt). Genom Silence, hans första blandmediala verk, ifrågasatte Costis författarens auktoritet genom att, på ett ironiskt sätt, förvandla dikten till ett förlorat dokument.

Överskridandet av genrer, intermedialitet och appro-priering karakteriserar även Natsha Hadjidakis kort roman

, , Möt henne på kvällen: an-teckningar kring en förlorad roman (publicerad första gången 1979). Hadjidakis kortroman är situerad i London, Paris och Aten, och är strukturerad som ett textuellt col-lage, där fragment ur en realistisk berättelse, självreferen-tiella anteckningar kring hur texten ska skrivas, annonser ur Time Out [fig. 32], kyrkliga texter, reklam [fig. 33], poli-siära efterlysningar och till och med beskrivningar av ljud, likt ljudspåret från en film [fig. 34], samexisterar sida vid

967

illustrated his magazine, [Mavros Ilios / Black Sun] (1981–1982), with his own collages allegedly derived from his own -actually fictional- book titled Hom-mage à Max Ernst [fig. 5].

Despite the fact that the circle around Pali brought together Surrealism with Beat and underground culture, in their collage practice they remained rather attached to historical avant-gardes. Nevertheless, this climate favoured the emergence of an alternative visual culture, which was diffused during the 1970s. The first collage influenced by Dadaist practices most probably is to be found on a flyer advertising the “avant-garde” literary magazine [Lotos/ Lotus] (1968–1971) made by its publisher, artist and poet, Costis (Triantafyllou) [fig. 6]. Still, it was in the magazines of Leonidas Christakis that the influence of Surrealist collage, merged with the legacy of Dadaist ty-pocollages was combined with Pop influences or with such manifestations of counterculture as comics [fig. 7–12]

The first signs of this counter-culture are to be traced back to Pali and the work of Panos Koutrouboussis, among others. In his drawings, already since the late 1950s, the heritage of Surrealism merged with comics’ influences in a drawing/ illustration which draw on the fantastic, cari-cature and grotesque. During the 1960s, Koutrouboussis used collage in comics that combined these characteristics with the fascination for sci-fi imagery, and that were con-ceived as single pieces – a kind of painting actually – even in series like Maschinen Reich, since his images were not connected through a narrative. [fig. 13–17]

During the 1970s, collage became a sign of political identity, namely of attachment to the Left. For artists who were interested in the “real” but challenged the Commu-nist canon of Realism, the Marxist tradition of Berlin Pho-tomontage proved once more in history to be the proper medium. Moreover, in some cases, the parallel employ-ment of Dadaist and neo-avant-garde practices facilitated artists’ criticisms of consumerism, current political situa-tions and the institutionalisation of art.

The first collages in this context were produced already in 1965 in Paris by Chrysa Romanos. Romanos in some of her collages [fig. 18, 19] dialectically juxtaposed images of commodity culture and mass media imagery on the one hand, with images of poverty and political upheaval on the other, in order to criticize consumerism, as well as the political situation. In some cases the juxtaposed groups of images constitute the parts of a construction, e.g. a shoot-ing gallery in an amusement park or a gambling table reminding us of Pop Art works, and signifying man’s fate in the context of international imperialist politics. In 1973, in her Pages from a Diary [fig. 20] Romanos employed in-termediality and introduced personal or trivial documents of her everyday life as a woman artist: photographs of her-self with her husband and of their country house, notes and preparatory sketches for her constructions, shopping lists, maps, fragments of envelopes and pages of a book.

The Dadaist practice of dialectical juxtaposition of frag-mented images of reality also underlie the compositional structure of the paintings of the Greek New Realists of the 1970s, especially of Jannis Psychopedis who seems to be drawing on the practices of Berlin Critical Realists as-sociated with the Poll gallery. In his paintings and collages

Psychopedis juxtaposes mass media imagery, painted after photojournalist material, with scenes from contemporary Greek life – migrants, men of labour, protesters violently attacked in political demonstrations or during the dictator-ship – or with images of appropriated works of art in vari-ous Realist styles. Thus, the employment of the Dadaist photomontage strategies along with appropriation enables him to explore Realism’s critical potential, to juxtapose various visual languages, as well as to sharply criticize commodification and institutionalization of art, when it comes to Pop Art. [fig. 20a–20b]

In the 1970s, certain neo-avant-garde writers and film-makers overcame the limits of genres and media for the first time. Literary texts experimented with textual col-lages and to some extent intermediality, questioning liter-ary discourse and the institution of literature. This text will mainly focus on the texts that explore the visual.

In the Visual Poetry of Michael Mitras the reception of the Marxist tradition of photomontage, merged with (delayed) influences of Poesia Visiva and Concrete, was employed along with neo-avant-garde practices to the ul-timate end of the integration of art in the praxis of life. In his To Alothi tis Perigrafis (The Alibi of Description, 1976) [fig. 21–28], Mitras builds on visual contrasts of mass me-dia images and texts, ads, photos of mechanical parts and urban landscape, printed matter with different typefaces sometimes directly alluding to specific high or low literary genres, hand script, tables, as well as of different languag-es (journalistic, technocratic, bureaucratic), finally, textual-ity and orality. Thereby he does not aim at dialectically producing a new meaning, but, according to his manifesto [fig. 29], at subverting the institution of literature by open-ing literary language up to the popular cultural, everyday experience and the reader and by experimenting with gen-res or languages considered low. Mitras’ prose texts [fig. 30] also explored the limits of narrativity through the use of the mundane and the inscription of different codes (e.g. traffic signs) in the text.

In 1976 the poet Costis (Triantafyllou) also turns to Vi-sual Poetry through a gesture of “erasure” which visualizes the writer’s block. In Silence. Le poème ce trouve sur le ruban [fig. 31], instead of throwing his typewriter ribbon away, he uses it as a kind of palimpsest bearing the traces of his writing on a “burned” blank page – as he calls it. This kind of collage was conceived as a “silent” testimony to the process of writing and was composed by pairs of antitheses (the sense of materiality of the typerwritter rib-bon and of the “burned” white page versus the conceptual character of absence and the void visualised by the blank page; black versus white). Through Silence, his first work in mixed media, Costis questions the writer’s authority, ironically making the poem a lost document.

Transgression of genres, intermediality and appro-priation also characterise Natasha Hadjidaki’s novella,

, Meet Her, in the Evening: Notes for a Lost Novel (first published also in 1979). Had-jidaki’s novella is set in London, Paris and Athens. It is structured as a textual collage, where coexist fragments of realistic narrative, self-referential notes on how to write the text, Time out classifieds [fig 32], ecclesiastical texts, ads [fig. 33], police announcements, even descriptions of

968

sida. Olika genrer (poesi och prosa, novell, kortroman, ro-man) och konstnärliga medier korsas, vilket undergräver referentialiteten och understryker läsandets performativa dimension. Växlingen mellan diskurser och användningen av engelska texter [fig. 35–36] problematiserar det litterära språkets standardiserade former och tillåter det vardag-liga och triviala att invadera berättelsen. Användningen av visuellt material (till exempel reklam, slagord, bilder ur skräckfilmer) lyfter fram ett mardrömslikt och filmiskt drag hos texten, och förstärker därutöver problematise-ringen av berättandet och den litterära diskursens gränser [fig. 37–38]. Hadjidaki utforskar även collaget i sina dikter, och i olika texter publicerade i avantgardistiska tidskrifter [fig. 39–40].

Inom filmen kommer användningen av termen ”col-lage” att konfronteras med ytterligare begreppsliga kom-plikationer, eftersom redigeringen och samexistensen av skiftande material alltid, från början, är införlivade i det filmiska språket. Följaktligen måste man vad gäller filmen, för att definitionen inte ska bli trivial, observera en speci-fik medvetenhet om dessa filmiska möjligheter. Tanken på ett ”dokument” är inte mindre komplicerad, eftersom de dokumenterande kapaciteterna hos filmen är särskilt tyngda av ideologi. Realismer som förespråkar antingen sannolikhet eller överensstämmelse har upprepade gånger visat sig vara konstellationer av konventioner för avbild-ning. Den avantgardistiska filmen undersöker och under-gräver sådana konventioner, såväl visuella som narrativa.

Någon avantgardistisk film fanns inte i Grekland före 1970-talet. Det är då som tre av de viktigaste avantgardis-tiska filmskaparna framträder med sina arbeten: Kostas Sfikas, Antoinetta Angelidi och Thanassis Rentzis. Dessa var alla politiskt engagerade i vänstern och involverade i den nya grekiska filmrörelsen. Därutöver satt både Sfi-kas och Angelidi i redaktionen för tidskriften

[Synchronos Kinimatografos / Sam-tida film], medan Rentzis på egen hand producerade tid-skriften [Film] (vilken ofta innehöll dadaistiskt in-spirerade collage). Dessa tre filmares arbeten ifrågasatte regelmässigt sociala verkligheter och estetiska konven-tioner genom utnyttjandet av avantgardistiska strategier, bland annat olika former av collage.

Emellertid utmärker sig Angelidis arbeten, och i syn-nerhet hennes film från 1977, Idées Fixes / Dies Irae, genom dess mer konsekventa utforskning av potentialen hos en filmisk heterogenitet [fig. 41–44]. Filmen använder collage av bilder och texter (på grekiska, franska, engelska, och från olika källor såsom reklam, politisk teori, slagord och självreferentiella anteckningar), och skapar mening genom samordningen av tecken och deras införande i skiftande kontexter. Den exploaterar den betydelse som skapas ge-nom syntesen eller oöverensstämmelsen mellan bild och ljud, mellan att visa och berätta, mellan skådespelare som agerar och stillbilder, projicerade ord, recitationer och mu-sik. Dessutom bryter den upp konventioner för berättande och representation som moment i en medveten feministisk strategi. I den del av filmen som inleds med orden ”père-peur” (fader-fruktan) och slutar med orden ”père-encore” (fadern-alltjämt) avfärdar filmen det sinsemellan besläk-tade aristoteliska berättandet och det oidipala förloppet som patriarkala strukturer genom medel hämtade från en

psykoanalytiskt färgad diskurs. I filmens andra del rym-mer varje tagning en referens till en konstnärlig rörelse – dadaism, lettrism, surrealism, hyperrealism etc. – där alla bilder och diskurser visas konspirera för att spärra in kvinnor. ”The film partition” publicerades i Synchronos Kinimatografos som ett separat konstverk [fig. 45].

969

sounds, like the soundtrack from a movie [fig. 34]. Genres (poetry-prose, short story, novella, novel) and art media are transgressed, creating an open self-referential text, that subverts referentiality and emphasises the performativity of its reading. The variety of discourses, the use of English texts and words [fig. 35–36] subverts the standards of lit-erary language, and allows the mundane and the trivial to invade the narrative. The use of visual documents (e.g. ads, slogans, horror film images) highlight the nightmar-ish and cinematic character of the text, further questioning the limits of narrative and literary discourse [fig. 37–38]. Hadjidaki further explores collage in her poems and texts published in avant-garde magazines [fig. 39–40].

In cinema, the use of the term “collage” enters into additional conceptual complications, because editing and the co-existence of different materials are always already incorporated in the cinematic language. Consequently, in order for our definition not to be trivial, one has to look in a film for a particular consciousness of these cinematic possibilities. Furthermore, the notion of “document” is no less complicated, as the documenting abilities of cinema are particularly heavy with ideology. Realisms, promoting either verisimilitude or faithfulness, have been repeatedly shown to be constellations of representational conven-tions. Avant-garde filmmaking interrogates and subverts such conventions, both visual and narrative.

There is no avant-garde cinema in Greece before the 70s. It is then that appears the work of the three most important Greek avant-garde film-makers: Kostas Sfikas, Antoinetta Angelidi and Thanassis Rentzis. They were all politically engaged in the Left and involved in the New Greek Cinema movement. Moreover, both Sfikas and An-gelidi were for some time in the editorial board of the magazine [Synchronos Kinimatografos / Contemporary Cinema], while Rentzis published single-handed the magazine [Film] (which often included Dadaist-inspired collages). The work of all three film-makers questions social realities and aesthetic conventions, using avant-garde strategies, among which several forms of collage.

However, the work of Angelidi, and particularly her 1977 film Idées Fixes / Dies Irae, differs significantly be-cause it explores more thoroughly the possibilities of cinematic heterogeneity [fig. 41–44]. It uses collages of images and texts (in Greek, French, English, and from dif-ferent sources, such as advertisements, political theory and slogans, self-referential notes), creating meaning through the juxtaposition of signs and their insertion into different contexts. It exploits the meaning created by the synthesis or disaccord between image and sound, between showing and telling, between actors acting and filmed still photos and projected words and recitations and music. It also breaks the representational and narrative conventions, as a deliberate feminist strategy. In the part beginning with the words “père-peur” (father-fear) and ending with the words “père-encore” (still/more of the father), the film denounces the interrelated Aristotelian narration and Oedipus trajec-tory as patriarchal structures by means of a psychoanalyti-cally inspired discourse. In the second part of the film, each shot is a reference to a different art movement – Dadaism, Lettrism, Surrealism, Hyperrealism etc – where images

and discourses all are shown conspire to confine women. The “film-partition” was published in Synchronos Kinima-tografos as an independent art-work [fig 45].

970

1. Nanos Valaoritis, « ’ …» [And the wedding took place at the palace…], [Pali/ Again], 1965, 5, 41, collage.

2. Nanos Valaoritis, « …» [But his wife got jealous], [Pali/ Again], 1965, 5, 43, collage. 3. [Pali / Again], 1964, 2–3, cover conceived by Nikos Stangos and Nanos Valaoritis.The ma-gazine was partly imbued with Surrealist collage aesthetic, since some of its illustrations drew on the illustration of 19th century novels.4. [Pali / Again], 1963, 1, 45. The magazine’s layout was partly imbued with Surrealist collage aesthetic, since some of its illustrations drew on the illustration of 19th century novels.

971

5. Salckin O. Silab & Co [Nikos Balis], [Mavros Ilios / Black Sun], 1981, 1, cover. The collages by the anarchist Nikos Balis were allegedly derived from his own – actually fictional – book titled Hommage à Max Ernst.6. Costis (Triantafyllou), collage on a flyer advertising the magazine [Lotos / Lotus], 1968, 21x29,7 cm.

972

7. Panderma, special issue on the comics of Lazaros S. Zikos, 1973, cover by Lazaros Zikos, drawing and collage with his own photo as a child. 8. Panderma, 1974, 8, cover illustrated with a collage by an unknown, found by Lazaros S. Zikos.9. Panderma, mid 1970s. The publisher, Leonidas Christakis, partly followed some principles of the Dadaist typocollage in his magazines’ layout.10. Super-Panderma, 1975, 13–14. One of the issues on the Baader-Meinhof case. On the upper left, a drawing by Costis (Triantafyllou) from his series [Onirodromio / Dreamdrome]. The

973

publisher, Leonidas Christakis, partly followed some principles of the Dadaist typocollage in his ma-gazines’ layout.11. [IliosAnthilios / SunCounterSun], [Kouros], 1974, 25. Special issue with poetry by Katerina Papaiakovou. Montage by Leonidas Christakis.12. [IliosAnthilios / SunCounterSun], [Kouros], 1974, 25. Special issue with poetry by Katerina Papaiakovou. Montage by Leonidas Christakis. An actual rasor was affixed on this page.

974

13. Panos Koutrouboussis, The Fountain of Love, 1967, collage, mixed media on paper (magazine cut-tings, torn paper & strips, liquid enamel, ink / ball-pen drawings and details, felt-tip markers, gouache), 31x21cm.14. Panos Koutrouboussis, “Marrir in the Tower of Thoughts” (: Maschinen Reich series), 1967, collage, mixed media on paper (magazine cuttings, torn paper & strips, liquid enamel, ink / ball-pen drawings and details, felt-tip markers, gouache), 18.5x 25.5 cm.15. Panos Koutrouboussis, “Son of Sag-ath” (: Maschinen Reich series), 1968, collage, mixed media on paper (magazine cuttings, torn paper & strips, liquid enamel, ink / ball-pen drawings and details, felt-tip markers, gouache), 11.1x15.2 cm.

975

16. Panos Koutrouboussis, “Vitch-oxrio of the Gates” (: Maschinen Reich series), 1969, collage, mixed media on paper (magazine cuttings, torn paper & strips, liquid enamel, ink / ball-pen drawings and details, felt-tip markers, gouache), 21.1x 25.8 cm.17. Panos Koutrouboussis, “Enypix Coronica” (: Exo-epidemics series), 1970, collage, mixed media on paper (magazine cuttings, torn paper & strips, liquid enamel, ink / ball-pen drawings and details, felt-tip markers, gouache), 21.6x14.8 cm.

978

20. Chrysa Romanos, three screen-prints from the folio, Some Pages from a Diary with a Postscript by Pierre Restany, 1973, 65x50.20a. Jannis Psychopedis [Hirafetisi / Emancipation], coloured pencils on canvas, 50x80 cm.

979

21. Michael Mitras, [The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition, cover.22. Michael Mitras, [The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition.23. ” [An Arithmetic Event”]. The printed text is an excerpt of prose descri-bing a man’s dream. The handwritten words or phrases exist in the printed text (“his mouth”, “the sun and the laughter of the girls”, “voices”, “end”). Michael Mitras [The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition. 24. The use of an ad of a “system of learning foreign languages”, the images of cassette recorders and tapes, as well as the parallel use of imperatives (“Listen carefully to the instructions”, “Read on page 87”) point at the standardization of language through mass culture. Michael Mitras,

[The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition, collage.

980

25. In the handwritten text in Greek, Mitras ironically notes the sense of imbalance created when the “accepted system of language construction” is called in question. Michael Mitras,

[The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition. 26. Michael Mitras, From [The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry col-lection, Athens, 1976, self-edition, collage.27. Self-portrait of the author, collage. Michael Mitras, [The Alibi of De-scription], Visual Poetry collection, Athens, 1976, self-edition. 28. “ [Literary Comments on a Mechanical Object]. Michael Mitras, [The Alibi of Description], Visual Poetry col-lection, Athens, 1976, self-edition, collage. 29. Michael Mitras, “ ” [The Rise and Fall of Conven-tional Literature], [Sima / Signal], 1975, 1. Michael Mitras, manifesto.

981

30. Michael Mitras, “Incomplete model of literary description (a short story)” in [Hroniko /Chronicle], 4, 1973, 88–89. The text consists of eight columns, each presenting an aspect of a road accident: kilometers (1), road signs (2 & 3), mechanical parts of the car (4), an advertisement for a car (5), description of a car trip (6), a newspaper article on a car accident (7), “an addition by the writer” (8). 31. Costis (Triantafyllou), Silence. Le poème ce trouve sur le ruban, 1976, charcoal and typerwritter ribbon on paper, 110x70 cm.

Fig. 27

982

32. London Time Out personal ads (in English) are included in the text. Natasha Hadjidaki,[Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost no-

vel], Egnatia, Thessaloniki 1979.33. Advertisements (in English) are included in the text. Natasha Hadjidaki,

[Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost novel], Egnatia, Thessaloniki 1979.34. This part of the narrative is written as a script. The first column describes the action while the se-cond column describes the sounds. Natasha Hadjidaki,

[Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost novel], Plethron, Athens 2009 (second edition).

983

35–36. Slogans in English are included in the text. Natasha Hadjidaki, «» [“The childhood of the tree of knowledge”], [Tram], 1976, 3, 194–97. This text was

later incorporated in the novella[Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost novel], (1979).37. The writer’s self-portrait as a vampire (collage). Natasha Hadjidaki, «

» [“The childhood of the tree of knowledge”], [Tram], 1976, 3, 191. This text was later incorporated in the novella Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost novel (1979). The collage nevertheless was not included in the first edition.

984

38. Proust says “HULK HITS TOWN”, juxtaposing high and low culture. Natasha Hadjidaki, «» [“The childhood of the tree of knowledge”], [Tram],

1976, 3, 191. This text was later incorporated in the novella Meet her in the evening: Notes for a lost novel (1979). The collage was not included in the first edition.39. Natasha Hadjidaki, “ ” [“Vivid Energy/Act”], [Sima / Sign] 1976, 2/14, col-lage and a manifesto on the periodical and the avant-garde. 40. Natasha Hadjidaki, “ ” [Self-Portrait] from the poetry collection [Acrylics], Athens, 1976. The appropriated work of art that frames the poem is The Sacrifice of Iphi-genia by Paul Delvaux.

985

41. Antoinetta Angelidi, “Mimesis / Naked Woman”. Photogram from the film Idées Fixes / Dies Irae by Antoinetta Angelidi. Techniques: Filmed actress in front of commercial photo. The words “femme nue” are painted on the filmed panels, while the word “mimesis” is written on the camera lens.42. Antoinetta Angeldi, “The State”. Photogram from the film Idées Fixes / Dies Irae by Antoinetta Angelidi. Techniques: Filmed actors in front of commercial photo. The word “state” is projected on the actor’s body. The frame is erased by a material line. Visible shooting equipment. The words spoken by the actors are a collage from texts of different sources, mainly advertisements and political slogans, in Greek, French and English.

986

43. Antoinetta Angelidi, “External Use”. Photogram from the film Idées Fixes / Dies Irae by Antoinetta Angelidi. Techniques: Projected words on actress’s body. On the soundtrack, a French troubadour song, followed by a Greek political song.44. Antoinetta Angelidi, “The Death of Marat and the Internationale”. Photogram from the film Idées Fixes / Dies Irae by Antoinetta Angelidi. Techniques: Filmed actress (the director) re-enacting David’s painting “The Death of Marat”. The word “horizon” is written on a glass in front of the lens. On the soundtrack the International played out of tune on a music box.

987

45. Antoinetta Angelidi, Page of the magazine Synchronos Kinimatografos (1978, 17/18, p.112), where the “film-partition” of Idées Fixes / Dies Irae by Antoinetta Angelidi was published. On the left-side co-lumn: a series of the film’s photograms. On the right-side column: the spoken words that accompanied them. They were in Greek or in French, taken from different sources, including very personal material. In the beginning of the text, a line of names is visible “Cage / Duchamp / Ernst / Magritte / Monk / Straub / Wilson”, followed by the self-referential “montage des citations”. The second part of the page begins with a syntax-game: a phrase is re-arranged in all possible ways.