Pride Lands: The Lion King, Proposition 187, and White Resentment

Transcript of Pride Lands: The Lion King, Proposition 187, and White Resentment

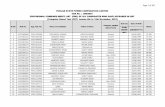

Pr d L nd : Th L n n , Pr p t n 8 , nd h tR nt ntB b l h

Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory,Volume 57, Number 3, Autumn 2001, pp. 121-152 (Article)

P bl h d b n v r t f r z nDOI: 10.1353/arq.2001.0001

For additional information about this article

Access provided by Wellesley College Library (4 May 2015 12:48 GMT)

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/arq/summary/v057/57.3.elahi.html

BABAK ELAHI

Pride Lands:The Lion King, Proposition 187,

and White ResentmentFor )enny, KaMa, and Roxanne

My son, Alexander, is a white male with blue eyes and blond hair. He hasnever discriminated against anyone in his little life (except possiblyyoung women visitors whom he suspects of being baby-sitters). But pub-lic policy now discriminates against him. The sheer size of the so-called'protected classes' that are now politically favored, such as Hispanics, willbe a matter of vital importance for as long as he lives. And their size is ba-sically determined by immigration.

Peter Brimelow, Aiien Nation (1995)

Peter brimelow's highly sentimental passage about his son's vul-nerability to the "protected classes" exemplifies a kind ofWhite re-

sentment that has dominated much of public middle-class discourse inthe past decade. Brimelow's comments rely on a personalized image ofWhite patriarchy in his emphasis on his son's white skin, blue eyes, andblond hair. Alexander, this apparently guiltless heir of an Anglo-Amer-ican tradition, is under threat from an unholy alliance between liberalgovernment and non-White minorities grouped in questionable racialcategories—i.e., Hispanics. In the 1990s, this image of the threatenedfair heir became a political rallying cry (for Brimelow and others likeWilliam Bennett) as well as a popular theme in films such as Braveheartand The Lion King, both of which tell stories of avenging sons. Thepolitical rhetoric of Peter Brimelow on immigration has a clear affinityto the racial allegory to be found in such seemingly harmless popular

Arizona Quarterly Volume 57, Number 3, Autumn 2001Copyright © 2001 by Arizona Board of Regents

issN 0004-1610

122 Babak Elahi

media as the enormously successful The Lion King. Together—alongwith other public texts—they provide a structure of meaning for manyWhite readers/spectators who, like Brimelow, feel that they have beendispossessed as a result of an "open" immigration policy and a "gener-ous" welfare system. Placed in the context of popular discussions of im-migration and race, and in the narrower context of its own "tributary"media, The Lion King's allegory of White resentment becomes clear.Two kinds of popular press can be read alongside The Lion King to

show how the ideology of White resentment constitutes a pattern cut-ting across these cultural areas. The first kind of press related to the filmis what, borrowing Paul Smith's term, I will call its "tributary media"(quoted in Willis 7)—popular press surrounding the film. This presshighlights the film's coming of age narrative, particularly in the contextof the father-son relationship. Stretching Smith's term, I also look atone article in English Journal that recommends the use of The Lion Kingin high school English courses to teach how archetypes work in Hamlet.In light of this emphasis on the patriarchal mythology and archetypesof the film, the threat of the villains can be read as both sexually andracially "marked" as non-white, non-heterosexual-male. Thus, a read-ing of these tributary media leads to a discussion of the wider mythol-ogy of race and sex in the film. The color-contrasts, mise-en-scene,voice-overs, and narrative of the film clearly suggest that Scar and thehyenas are non-White or, at least in the color-scheme of the film, non-blond. The second kind of popular press that connects with the themesof race and patriarchy in The Lion King are popular editorials on immi-gration—including, specifically, Peter Brimelow's book-length editor-ial, Alien Nation—that circulated in the public sphere in the Summerand Fall of 1994.The pattern of White resentment, a pattern that clearly cuts across

film, popular press, and other forms of discourse has, in fact, a long his-tory in U.S., White, middle-class discourse. Indeed, the myth of awhite patriarchy under attack from an alliance between radical Whitegovernment and non-White invading hordes goes back to the birth ofHollywood when Thomas Dixon's The Clansman, William Denning'sand Woodrow Wilson's historical writing, and D. W. Griffith's TheBirth of a Nation provided a structure of feeling similar to 1 990s racialresentment.

Pride Lands 123

'the lion king' and its tributary press

Sharon Willis argues that in the North American public sphere, somuch informed by the talk-show format, "public opinion" tends to beseen as a kind of meteorological "event," like the weather. "A singularlyshaping force within this public sphere," she continues "is the regularmedia discussion around the film industry." Willis turns to Paul Smith'sdefinition of the "tributary media" of a film: "Part of the discursive roleof reviews and journalistic criticism (as opposed to the popular dis-course that the industry describes as 'word of mouth') is to set parame-ters for cultural discussion, and one of the centrally important strategiesin that task is the attempt to construct intentions for any given film—that is, the attempt to affirm or confirm that the film's meaning is notaccidentally produced" (7-8). By reading some of the tributary presssurrounding The Lion King, we can see how an industry magazine, likePremiere, can function as an aid to consumption, "affirming or confirm-ing" a particular meaning in the film, and suggesting that the produc-tion of that meaning was intentional on the part of its auteur or, in thecase of Lion King, its producer, Jeffery Katzenberg.The narrative of The Lion King is a bildungsroman. It describes

Simba's (Matthew Broderick) exile from and return to the kingdom towhich he is heir. The Pride Lands—ruled by Simba's father, the benev-olent Mufasa (James Earl Jones)—is plunged into chaos and ruin whenScar (Jeremy Irons) teams up with a pack of hyenas to assassinate Mu-fasa, blame his death on Simba, chase him off the Pride Lands, andusurp the monarchy. After a time in exile, Simba returns with the helpof some new friends, including a baboon mystic (Robert Guillaume), todefeat Scar, chase off the hyenas and take his rightful place as king.Lion King's tributary press confirms and highlights the theme of coming-of-age and the importance of a father figure in the son's process of mov-ing from boyhood to manhood. A review of the film in Premiere notonly focuses on this theme, it does so by presenting then Disney Presi-dent Jeffery Katzenberg as a kind of auteur whose own life experiencesprovide the impetus for the story, and whose reaction to the finishedproduct provides its preferred reception.1 In both authorship and recep-tion, father-son symbolism is central.Ari Posner's July 1994 Premiere article, "The Mane Event," begins

124 Babak Elaki

with a bold statement about Jeffrey Katzenberg who is pictured promi-nently on the first page of the article: "Jeffrey Katzenberg can recall theexact moment when he became a man" (81). According to Posner'ssources, including chief of animation Peter Schneider, this coming-of-age moment "guided the making of the film," The Lion King. That mo-ment happened in 1973 when Katzenberg worked as a "lowly assistant"for New York mayor John Lindsay who was being investigated concern-ing a "minor scandal." Katzenberg, or "Squirt, as he was known in thosedays," is scheduled to testify before a grand jury. "But then one night"writes Posner in dramatic style, Katzenberg "is awakened, handed aplane ticket, and told to 'get out of town.'" During a promotional tripfor The Little Mermaid in 1989, Katzenberg tells a version of this story toother animation executives on a plane, a kind of "group encounter ses-sion in the sky" (82). Others tell about their "moment," and Katzen-berg provides the impetus for "a story set in Africa" that deals with thevery "moment," and "it literally was that—a moment," when a boy be-comes a man.

For Katzenberg, the transformation from Squirt to man takes placeas a commitment to language and the law—he chose to testify in frontof a grand jury. The importance of word and law in Katzenberg 's com-ing-of-age story translates into the importance of the monarch and thefather in King. But before discussing how the father-king myth plays it-self out on the screen, I want to discuss how Katzenberg's own responseto the film is a preferred reading that highlights precisely the patriar-chal myth in his own life and in the film. Katzenberg, Ari Posner tellsus, wept at the opening of the film, which was dedicated to the memoryof former Disney President Frank Wells who died in a helicopter acci-dent earlier that year. Katzenberg wept because, presumably, he saw aparallel between the Mufasa-Scar-Simba relationship on screen and theWells-Eisner-Katzenberg relationship in the Disney management team.According to other articles in Premiere and other popular journals,Katzenberg saw himself as the heir apparent to Wells's position, but felthe was betrayed by Eisner.2 "Katzenberg is unabashed about his attach-ment" to the film and to Wells. "Sitting in his immaculate office daysafter Wells' death, he describes the memorial service. 'We ended thecelebration of this extraordinary man's life with the First A.M.E. Churchcoming in and singing "Circle of Life." So last night, we go into amovie theater, and our movie started playing "Circle of Life," and' he

Pride Lands 125

says, ? started crying again'" (Posner 86). The "Circle of Life," the film'spseudo-ecological message, is actually an anthem for the royal succes-sion of power, or in Katzenberg's case the corporate succession of power.As the song plays, all the animals of the Pride Lands gather around acentral jutting rock and arrange themselves by species and bow down toMufasa, the Lion King. Katzenberg's identification with Wells can beread in the context of this praise to the monarch. It was, in fact, afterMichael Eisner (then ceo) did not promote Katzenberg to Wells' posi-tion that Katzenberg left Disney to co-found DreamWorks.In this relationship between the auteur's life and the film's narrative

of power and hierarchy, the patriarchal element of the film becomescentral. In an important scene in The Lion King, Simba confronts his fa-ther's, Mufasa's, ghost reflected in a pool of water. Rafiki, a baboon mys-tic (the conventional "helper" figure in classical folk tales), tells Simbathat his father lives on within him; he can run but not hide from his fa-ther—his father's image and his father's voice. Seeing his father's facein his own reflection, Simba enters the symbolic order—in this case,the adult realm of a Manichean cosmos and personal responsibility—when his own unsatisfying reflection magically transforms into a perfectand whole image of his father's face. Juliet Mitchell argues that the La-canian "subject is created from a general law" that is related to the sub-ject through "the speech of others." Furthermore, this subject is "not anentity with an identity [but] a mirage arising when the subject formsan image of itself by identifying with other's perception of it" (8). Thecoming-of-age moment occurs when Simba sees his father's face in hisown reflection and hears his father's voice tell him "remember who youare." Read in psychoanalytic terms, the transformation from "cub" to"lion" occurs at the moment when Simba accepts the law of the father,and moves from the imaginary to the symbolic domain. Katzenbergshares this movement into the symbolic with Simba as he relives hisearly adult experience. The father or father figure is the privileged sub-ject by which all other subjects are measured. In Katzenberg's memoryof his early political work, law and logos are the representations bywhich all other representations are measured. Indeed, The Lion Kingitself arises out of this early experience with word and law.Stretching Paul Smith's definition of tributary media, I want to turn

to an article published in English journal in 1996. By looking at how thefilm is used in a public context like the high-school classroom, we can see

I2Ó Babak Ehhi

how meanings similar to those that Posner's article affirms and confirmsin the text are confirmed and affirmed elsewhere, in a slightly differentway. Paternal authority is not only part of the message that the creators"put into" the film; it is also an idea that audiences clearly take from it.Consider how Rosemarie Gavin teaches Hamlet. She writes in a

journal designed for secondary school teachers that her students andcolleagues "cannot find much that is heroic in the Danish prince. . . .He doesn't even assume the throne but leaves it to a foreign prince be-fore he, himself, dies" (55)· Playing upon the narrative similarities be-tween The Lion King and Hamlet, Gavin pairs the two texts in such away that "students discover that both Hamlet and Simba represent themythical archetype of the exiled child whose role is to restore worldorder and who has an heroic task. Students also realize that they too areunique individuals on heroic journeys" (56, emphasis added). Gavin'spedagogical project seems to be to normalize precisely those elementsin Hamlet that complicate notions of nationalism, political power, andthe normative individual self. The anti-heroic elements of Hamlet arewell known, but it is important that Gavin (along with her colleaguesand students) are especially troubled by his anti-patriotic qualities—"he doesn't even reclaim the throne but leaves it to a foreign prince."Ultimately, she argues that both Hamlet and Simba are archetypal he-roes—exiled children who return to avenge their fathers and restoreworld order. While she may be teaching students about a presumablyahistorical archetype that transcends time, place, and culture, she isalso implicitly teaching a specifically historical and social lesson aboutthe symbology of father-and-son in nationalist discourse.And, indeed, the parallels between Lion King and Hamlet (and, one

might add, Oedipus Rex, The Odyssey, and Henry ÍV) are clearly there.However, in drawing parallels between Shakespeare's play and Katzen-berg, Minkoff, and Allers' film, there is no place in Gavin's pedagogicalworld order for hyenas. Gavin draws certain parallels in her essay—be-tween Hamlet and Simba, the murdered fathers, Gertrude and Sarabi,Scar and Claudius, "Timon and Pumbaa are as faithful as Horatio" (55).It is clear that the hyenas are precisely what destroy the "world order"that Simba (and the student-spectator) must restore, but nowhere doesGavin mention the hyenas directly. She absents the abject from herteaching of the texts and its myths. This blind-eye that she turns on the

Pride Lands 127

villains may have something to say about how those villains pose athreat to the heroes and helpers. Just as Mufasa, early in The Lion King,tells Simba not to venture into the elephant graveyard, the realm of theheinous hyenas, Gavin seems to be telling her students not to enterinto a consideration of otherness. It is as if the characters of the hyenasconstitute a semantic danger zone that threatens to deconstruct herreading of the text as analogous to Hamlet.

I see Gavin's article as a case study that shows how audiences in gen-eral might respond to The Lion King. Gavin's classroom is rife with in-stitutional, ideological, and personal limits to what student-spectatorsshould or should not respond to. However, Gavin's and Posner's articlesdo give us a sense of how a broadly understood tributary media guidesconsumption/reception of Lion King in a particular direction, a direc-tion that strongly emphasizes patriarchal identification. As such, bothof these articles—and the film's tributary media in general—avoid anyconsideration of the potentially racial connotations of the theme of pa-triarchy. Most popular articles on the film avoid or trivialize its racial ifnot racist connotations.

SHARP CONTRASTS AND RACIAL MARKINGS

In "A Short History of Disney-Fascism," Matt Roth has already dis-cussed The Lion King as an allegory of suburban resentment against aracialized inner city (40). In the 1990s, this was the latest manifesta-tion of what Roth sees as a fascist tendency in Disney characterizationfrom Stromboli in Pinocchio to Jafar in Aladdin. Roth reads the vilifica-tion of Whoopi Goldberg's and Cheech Marin's "street voices" for thehyenas Shenzi and Banzai as part of a fascist anti-urbanism in Disneydiscourse. Hollywood film of the 1990s was marked by this kind ofresentment of alterity in such films as Falling Down. What Lion Kingshares with Failing Down, and with discourses of white resentment ingeneral, is the stark contrasts it sets up between the White family—par-ticularly the White father—and dark threats from across the tracks oracross the border. To be sure, even in a film like Falling Down, theracialized construction of the threat to the family is mitigated by thefather's own insanity—the Michael Douglas character is clearly por-trayed as psychotic. And yet, the father's psychosis is itself brought on

128 Babak Elahi

by the socioeconomic—and in some ways, ethnic—chaos he witnesseson the street. As Sharon Willis argues, the racial element in films likeFalling Down is presented in "color contrasts" (2).As an animated film, The Lion King represents race through sharp

color contrasts and racialized "markings." These seemingly harmlessimagings resonate with public discussions of the racialized and sexual-ized threats perceived to be impinging on the White home. "Whilepopular films built of sharp contrasts seem to assign a general weight-lessness to social identities," Willis "proposes to assess the gravity ofthose social identities and to investigate the massive ideological workthey perform" (2). Willis claims that Hollywood film in the mid-1990stended to rely heavily on "marking" through high contrast. These con-trasts perform both an aesthetic and an ideological function; they makeart while they also mark—or point to—racialized identities. Willis ar-gues that "'marking' [is] a common technique for managing racial dif-ference to the profit of 'whiteness'" (4).The terms "sharp contrast" and "marking," as well as "management"

and "profit," seem to apply very well to a reading of Disney animation."Animated film" according to Roger Noake, "deals with illusion—theillusion of projection and the phenomenon of the persistence of vision.It deals with the way in which an audience responds to this illusion andaccepts or conspires with it" (no).' This notion of conspiring with theillusion is highly suggestive of how identification works in all film (ani-mated or live action), and especially in this case. As the Posner andGavin articles suggest, audiences conspire with this animated film tobelieve in a happy and magic animal kingdom; they also conspire to be-lieve in a specific coming-of-age scenario in which the son fills in thefather's shoes, and opposes racialized and sexualized others. While thiskind of identification and narrativization is also at work in live-actionfilm, animated film can claim—though, of course, falsely—that it ismore fantastic, less naturalistic, and less documentary, than live actionfilm. It can be and is claimed that animated film is harmless.James Snead argues that cartoons encourage a "rhetoric of harmless-

ness" in order to "camouflage the political" and often racist meanings offilms like Song of the South and even Fantasia (85, 89). This rhetoric of"harmlessness," I would argue, continues to be at work in the produc-tions of the "new" Disney. The color contrasts in The Lion King are

Pride Lands 129

clear enough. The villainous and shiftless hyenas—Shenzi (WhoopiGoldberg), Banzai (Cheech Marin) and Ed (Jim Cummings)—are adifferent color (mostly ash-gray, black, and even green) from the "good"characters (the blond lions). According to Roth, the hyenas "clearlyrepresent poor blacks and Hispanics," and "when their populationspreads out, their wasteland, for no apparent reason, spreads with them"(18, 16). Scar, the King's jealous brother, has a darker coat (closer tobrown or dirt than blond) and a black rather than auburn mane. Scar'sphysical weakness is itself a threat to the patriarchy. His sexual deca-dence is a direct threat to Simba. And his alliance with the hyenas is athreat to the kingdom—the Pride Lands.Rather than relying on black extras or white actors in black-face or

brown-face, as early Hollywood film did in narrating White supremacy,Disney (both under the leadership of Walt and in its manageriallystrained 1990s manifestation) can narrativize a racist ideology by thehigh contrast of painted and otherwise animated characters rather thanactors.4 The bright golden—blond—color of Simba, Mufasa, NaIa, andthe other members of the pride can be sharply contrasted to the darkershades of Scar, and to the black/blue/gray coloring of the hyenas. Colorand species stand in—iconically—for race. It may be argued that thesesharp contrasts and "markings" are empty and abstract. And especiallyin a film in which the patriarch's (Mufasa's) voice is rendered by a blackactor (James Earl Jones), any claim of a racial or racist ideology mayseem tenuous at best. However, since it is only Jones's voice, one notedfor its deep bass and impeccably articulated pronunciation, and not hisface that is part of the film, and since the voice of the heir is renderedby Matthew Broderick, it is clear that some kind of racial ideology is atwork here. I want to reveal this racial ideology under the film's "harm-lessness" by examining how the film's ail-too familiar narrative ofthreatened-then-restored kingdom can be read in terms of racial andsexual threats to the boundaries of territory and identity.

PRIDE LANDS

The happy kingdom, which is threatened and restored in The LionKing, is the normative father's kingdom, the realm ofWhite patriarchy.The threat posed to it is the reversal of the "natural" order of predator

I30 Babak Elahi

and prey, though, as Matt Roth points out, this order is anything butnatural. Roth argues that the film's "eco-speak" sets up a bizarre foodchain in which zebra and antelope "reverently bow down before a LionKing who makes no bones about wanting to eat them" ( 16). All the an-imals genuflect before the blond lion's power except the hyenas who areabject scavengers in a system that otherwise serves the lions. The hye-nas are not only excluded from the food chain, they are excluded fromthe territory itself. Thus, rather than representing a harmonious eco-system in which even scavengers must have a place, the "Circle ofLife" represents a border, a bounded territory. It is the hyenas' unholyalliance with Scar—the dark, intellectualized and effeminate outcast—that poses the threats of appetite and consumption. Here, we can ex-tend Matt Roth's critique of what he calls Disney "fascism" to under-stand the psycho-social connotations of the elaborate relationships inthis text between predator and prey.The first predatory threat to Simba comes from his Uncle Scar. Early

in the film, Simba asks Mufasa about "that shadowy place," and Mufasareplies that it "lies beyond our borders," and tells Simba never to gothere. Everything he has just told his heir about the Circle of Life ap-plies, apparently, only to a bounded space beyond which—we must as-sume—is the chaos of death. Soon after this injunction ("don't gothere") Scar—anthropomorphized by Jeremy Iron's "sexually decadent"voice, as Ari Posner called it in Premiere (81)—seduces Simba into dis-obedience. Scar's threat to Simba in this scene is both predatory andsexual. Simba asks Scar what he will become when Simba becomesking, and Scar says, "a monkey's uncle," that is, surprised. Clearly, this'60s slang is aimed at adult viewers, lobbed over the heads of a veryyoung audience. However, when Simba himself says "You're so weird,"Scar suggestively replies, "You have no idea." While kids might laugh atthis comment, they have watched Scar torment a mouse and know hehas a mean streak. Adult viewers recognize the real danger of sadism inScar's voice. Furthermore, since Scar is significantly darker—despitebeing a member of the pride—his threat is also a racial one.Scar's darker coloring, scraggly white beard, and emaciated frame

call to mind two racial stereotypes: the despotic oriental and the de-generate White. First he is reminiscent of the Eastern despot most fa-mously characterized in the twentieth century in Sax Rohmer's "insidi-ous Dr. Fu-Manchu":

Pride Lands 131

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high shouldered, with abrow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan . . . long magneticeyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cun-ning of an Eastern race. . . . Imagine that awful being, and youhave a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril in-carnate in one man. (25-26)

Scar, of course, has the advantage of already being a cat, but his lean-ness, his long face, and sunken cheeks are much like the SatanicShakespearean features of Fu-Manchu. Scar, however, is not an eviloutsider, but a sinister insider. In this role, he also calls to mind theracial degenerate exemplified in Austin Stoneman, the White villain ofThomas Dixon's The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku KluxKlan. In a chapter introducing Lydia Brown, Stoneman's mixed-racehousemaid, Dixon pays special attention to Stoneman's physical defor-mities as the result of his association with darker people, especiallydarker women. Though she is his maid, Lydia holds a mysterious andvaguely sexual sway over him, resulting in the depletion of his man-hood. Her "sleek tawny face and catlike eyes" seem to affect him physi-cally (94)· And his own animal, even catlike features indicate his de-generacy. For example, "the nostrils of his eagle-beaked nose [breathe]rapacity" (99). And when Stoneman receives a mysterious letter fromLydia, "his yellow fingers closed on the missive, [and] his eyes flashedfor a moment with a catlike humour," while the "woman's face wore themask of a sphinx" (100). Like Stoneman and other "degenerates," Scaris a peculiar combination of intellectual vigor and physical infirmity; heasks Simba, with his characteristic irony, to be excused "for not jump-ing for joy" about Simba's future succession to the throne; "bad back,you know." As a despotic yet frail mastermind behind an alien invasionof the Pride Lands, Scar is a synthesis of these racializing discourses ofthe yellow peril and the disloyal and degenerate intellectual.'Bram Dijkstra argues that the fantasy of a cat-like female threat to

masculinity first crystallized in the early twentieth century and that itcontinues to be part of popular cultural treatments of gender and sexu-ality. The film relies on a popular cultural synthesis of femininity andracial otherness, what Dijkstra describes as the creation of "hungry anddangerous" monsters in twentieth-century American pulp fiction andfilm. Though not female himself, Scar's intellectualized and effeminate

132 Babak Elahi

characteristics, along with the characteristics of his successor—the lion-ess Sheera in The Lion King U—draw upon a history of such figures whosealliance with racial others made them degenerate threats to the cult ofmasculinity.6 By playing out predatory threats, and eventually restoringthe "normal" food chain, The Lion King attempts to show how a Whitepatriarchal order might be threatened and then restored.The second predatory threat to Simba comes shortly after he asks

his mother for permission to go to the watering hole—a ploy to get hisfriend (half-sister?) NaIa to go with him to the elephant graveyard. AsSimba's mother licks him clean, he persuades her to allow him to go.But no sooner has Simba escaped his mother's licks then he faces amore real and sinister threat; he is almost literally devoured by hyenas.The female hyena Shenzi is the most threatening of these figures as shejokes, "make mine a cub sandwich." Beginning with Scar's threateninglooks, and reaching a climax with Shenzi's threat to eat Simba, anxi-eties about predator becoming the prey build for the audience. Symbol-ically, the tension about being consumed and absorbed points to theabsorption not of the body itself but of identity, of a sense of self. Bythe time he is in exile, it is his identity—"remember who you are," saysRafiki—that Simba must regain, as if all that threatened to swallowhim up had swallowed up his memory of what he was—the blond maleheir. In exile, Simba does not stay true to his predatory instincts, butdescends the food chain to eat insects in a jungle paradise. As his exilesuggests, these threats to identity are related to the threat to territory.Simba is alienated from both instinct and habitat.To counter the threats to predatory identity, the film plays out a con-

quest of gendered, racialized, and sexualized space, thus restoring boththe self and homeland. The film's narrative movement toward this res-olution maps racialized territory onto filmic space. The filmic space inLion King is layered with potential meaning in the way that Ellah Sho-hat has argued the cinema of empire is layered.7 In this model, un-mapped territory is described as feminine, as virgin land that must bepenetrated. In the case of the Pride Lands, it is a sexually decadent andthreatening realm that must be contained and avoided. The geographyof Lion King is divided into the realm of the Pride Lands and the "darkplace" of the elephant graveyard. The central landmark of the PrideLands is Pride Rock, a crag that juts out over the savanna. Through the

Pride Lands 133

use of a multiplane camera, a process designed by Ub Iwerks at Disneystudios in the 1930s and developed further by Disney animators since,the illustrations are shot in a way that gives the illusion of depth. Anumber of simulated shallow focus shots, 360 "pans" and "crane" shotsin the opening sequence establish the centrality of Pride Rock and thesubmission of all else to this central image. The sequence ends with a"crane" shot directly above Pride Rock, where Rafiki stands holding upSimba for the animals of the Savanna standing at attention and groupedby species.The Circle of Life can be understood as the space and group of iden-

tities that it hierarchizes: a bounded territory and a class system with itsrulers, its bureaucrats, its foot soldiers, and its outcasts; at its center risespatriarchal power. The most dangerous space within The Pride Lands isthe dry riverbed. It is here that Mufasa is killed as a herd of wildebeests,ushered in by Scar and the hyenas, overrun the unsuspecting Simba. Topreview some of what I will say later, this film can be read as structurallysimilar to arguments against immigration as a natural disaster, a flood,or a stampede. The anti-immigration argument that says an unscrupu-lous liberal elite allows a horde of immigrants to overrun Americaseems to be depicted visually in this scene in which a stampede kills thefather and exiles the son. The Pride Lands must be policed. And earlyin the film this policing is represented in the form of a prairie dog—akind of underground police—who reports that hyenas have entered thePride Lands. The Circle of Life, then, is really a border that separatespredator not from prey but from scavenger.The realm outside the Pride Lands is the cavernous structure of the

elephant graveyard where Scar's hyena henchman hide out in cracks,crevices and caverns. On the savanna, characters stand out againstsparse drawings of open plains, while in the graveyard scenes, the illus-trations of caves and bones threaten to obliterate the drawings of NaIaand Simba. Furthermore, as Mufasa tells Simba, the Pride Lands aremarked by "all that the light touches," making the realm of Scar andthe hyenas a dark danger zone. Entering that space, one risks being de-voured by the sexually and racially abject. The realm outside the PrideLands is the realm of the man-eating female. This characteristic of theoutside comes across even more convincingly in the sequel, SimbasPride. In this film, Sheera—the dark leader of the Outlander lions—

134 Babak Ehhi

resembles the hungry and dangerous females that Dijkstra has found tobe so prominent in twentieth-century popular cultural representationsof racialized sexuality.A third space disrupts the Pride Land-graveyard dichotomy when

Simba goes into exile and meets Timon (Nathan Lane) and Pumbaa(Ernie Zaballa), a free-spirited and fun-loving meerkat and warthogduo who live by the motto, "hakuna matata"—don't worry, be happy.Timon and Pumbaa's jungle paradise might be read as a college frater-nity—a homosocial space that allows the young initiate to do whatmight be frowned upon at home or in the classroom. This homosocialjungle promotes eating bugs and farting just as the homosocial space ofthe fraternity encourages drinking beer and farting, and, perhaps, eat-ing bugs. This might be read as the buddy-movie section of the film inwhich Simba bonds with Timon and Pumbaa and learns to live for thepresent. Taking Rosmarie Gavin's reading of King in relation to Hamlet,we might also compare the Simba-Timon/Pumbaa relationship to thePrince Hal-Falstaff relationship in Henry IV. This space, then, is alsothreatening in that Simba risks forgetting his true identity as king,choosing hedonism over royal responsibilities. Just as Scar's sexuality,Shenzi's appetite, and the elephant carcasses threatened to devourSimba, Timon and Pumbaa's "lifestyle" threaten to render him impo-tent—eating bugs instead of hunting wildebeests, cavorting with ameerkat and a warthog instead of producing an heir with NaIa (MoiraKelly). He seems incapable of being the Pride Land's mane man whilehe is on Timon and Pumbaa's turf.To dispel this threat, the narrative calls for Simba's childhood friend

NaIa and his mystic monkey guide Rafiki to come and remind him ofhis identity and his responsibility. The song "Can You Feel The LoveTonight" brings Simba and NaIa together in a scene that ends withSimba's normative heterosexual gaze falling upon NaIa reclining in abed of grass. Shortly after this, Simba looks into a pond and sees his fa-ther's face reflected back; it is this internalizing of the father throughthis reflection that reinstates Simba's masculinity within the territoriallaw of the father: the Circle of Life, the (b)order of the predator. Thisresumption of normative roles culminates in the aggressive defeat ofScar and the hyenas, and the production of offspring by NaIa and Simba.Ultimately, then, the potentially transgressive space facilitates ratherthan subverts Simba's re- installment into a normative subject position:

Pride Lands 135

the King of the Pride Lands, sovereign to a bounded territory, returningfrom exile to reclaim the throne-phallus, Pride Rock. The film ends byrestoring both territorial and identitarian borders.

NATIVIST IDEOLOGIES OF INCEST AND

MISCEGENATION IN 'THE LION KING'

But there is an unresolved dilemma at the heart of this film—the sug-gestion of incest between NaIa and Simba, and between their daughterand an "outlander" in the sequel, Simba's Pride. As Matt Roth observesof Lion King, Mufasa is the only breeding male in a pride of many fe-males, making Simba and NaIa, as far as we know, half-siblings. Thistendency to keep reproduction "all in the family," so to speak, leads tonarrative contortions in Simbas Pride. The story is about star-crossedlovers, Simba's daughter Kiara, and Sheera's son Kovu. However, as theindustry magazine Variety reported in 1996, Michael Eisner was con-cerned about any suggestion that Kovu might be Scar's offspring—mak-ing Kovu and Kiara cousins (Fleming 4-6). 8 To avoid any suggestion ofincest, the writers for Pride make Kovu Scar's handpicked heir—to fol-low in his "paw prints"—rather than his biological offspring in order toavoid any suggestion of kissing cousins. However, as Roth's observationabout Lion King suggests, Kiara is already the product of inbreeding. Thesuggestion of incest seems almost unavoidable.Incest is, in fact, an important element of The Lion King as an al-

legory of White resentment and nativism. In his discussion of thenativist discourse of the 1920s, Walter Benn Michaels argues that en-dogamy replaced exogamy as a way of securing purity of blood—at leastin the discourse of nativism as he reads it in both fictional and non-fictional representations. The only way to secure purity of "Pride" in theLion King saga is through endogamy. As Michaels puts it in referenceto William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, "keeping women in thefamily turns out to be identical to keeping them from Jews" (7). The LionKing's narrative distortions around family ties point to its concern forpurity of blood and the keeping of women and natural resources (thegame animals) from hyenas. Thus, in Simbas Pride, which tries to nar-rate assimilation rather than exclusion, the hyenas are completely ab-sent. "Outlanders" are allowed back into the pride, but even this nar-rative of assimilation requires the death of a gendered and racialized

136 Babak Elahi

other—Sheera, the dark matriarch of the "outlanders." Sheera, whohas threatened to eat Kiara and Kovu, must die before Kovu can returnto Simba's pride. In the seemingly harmless form of animated film, TheLion King plays out some of White American audiences' longest stand-ing and deepest fears about racial and sexual penetration of boundedterritory, and the subversion of normative identity through miscegena-tion. It resolves these fears through expressions of White resentment.

WHITE RESENTMENT AND NEW NATIVISM

Nativism, according to Juan F. Perea, combines a number of "cul-tural antipathies and ethnocentric judgements . . . into a zeal to destroythe enemies of a distinctly American way of life." Perea defines na-tivism further as "a preference for those deemed natives; simultaneousand intense opposition to those deemed strangers, foreigners" ( 1 ). Withevery wave of what gets called "new immigration" (1840s, 1880S-1910S,1980s to present), there is a surge of (new) nativism. Leo Chavez, forexample, argues that "'new' nativism sounds strikingly similar to 'old'nativism" in that it relies on a rhetoric of scarce resources, invading orinundating foreigners and their ethnic/cultural strangeness, as well asthe stress they place on the native economy. "In the discourse of con-temporary social sciences, immigrants have become the less moral, un-deserving, and threatening Other in society," concludes Chavez (73).Kevin Johnson points specifically to the racist undertones of Propo-

sition 187, a California bill that proposed to cut off social services andpublic education to illegal immigrants, and which passed into law in1994, as an example of the "new nativism." Johnson quotes one of thedrafters of the bill, Barbara Coe: "You get illegal alien children, ThirdWorld children, out of the schools and you will reduce the violence.The fact is . . . You're not dealing with a lot of shiny faced, little kiddies.. . . You're dealing with Third World cultures who come in, they shoot, theybeat, they stab and they spread their drugs around in our school system. Andwe're paying them to do it" (quoted in Johnson 179). Clearly, this is thefear—or at least the rhetoric of fear—about a child being (b)eaten bythe Third World Other.Like nativism, white resentment requires borders. Cameron McCar-

thy describes resentment as "a process of fabricating one's own identitythrough the strategy of negating the other and the tactical and strate-

Pride Lands 137

gic deployment of moral evaluation and emotion" (275). Furthermore,McCarthy also argues that discourses of racial resentment "loop backand forth through the news media to the classroom, from the film cul-ture and popular music to the organization of affect in urban and subur-ban communities . . ." (277). Just as the tributary press surrounding TheLion King emphasizes its patriarchal themes in what can be read as anallegory of race, so, too, can The Lion King be read as a text that informsa broader politics of White resentment, particularly in relation to thedebate over immigration that coincided with its release.A number of articles on immigration and Proposition 187 appeared

in the L.A. Times in the Summer and Fall of 1994, and they use a rhet-oric of resentment similar to the narrative of resentment that I've out-lined in analyzing King." Nicknamed the "Save Our State" bill, Propo-sition 187 argues that the influx of immigrants into California woulddeplete that state of its economic resources. The L.A. Times articles onthe 187 debate that most strikingly reproduce a rhetoric of resentmentare those that divide space into realms of chaos and order, and usefather-son symbolism to depict the restoration of order.10Many of the L.A. Times articles on Proposition 187 and immigration

in general, provided a mapping of territory similar to what I have dis-cussed in relation to The Lion King. While the sexual connotations ofthese articles are not as pronounced as the ftlmic signifiers in The LionKing, there is still a clear binary opposition between the chaos "South"of the border and the stability "North." It is this chaos that threatens todestroy California's economy just as the hyenas destroyed the "Circleof Life." For example, Brian O'Leary Bennett, a conservative critic ofProposition 187, quotes Ronald Reagan's description of an imaginedshining city that sounds a lot like the Puritan "city on the hill," but alsolike the Pride Lands where everything is touched by light:

I've spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don'tknow if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it.But in my mind it was a tall proud city built on rocks strongerthan oceans, wind-swept God-blessed and teeming with peo-ple of all kinds living in harmony and peace . . . and if therehad to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors wereopen to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That'show I saw it and see it still. (B7)

138 Babak Ehhi

Ronald Reagan's city is built on rocks like Pride Rock and, not inciden-tally, like the Puritan City on the Hill; all kinds of people live in har-mony as in a circle of life; doors are open to those with iron will andlion's heart. By invoking the words of a former President and a formerGovernor of California who violently opposed the United Farm Work-ers strikes of the 1960s and '70s, O'Leary Bennett criticizes 187 withone hand, while condemning immigration with the other. Ultimately,Reagan's shining city is the space of First World harmony while to theSouth is to be found the realm of Third World chaos that threatensto spill over into the U.S. O'Leary Bennett repeats one of the mostcommon arguments about immigration (from either side of the 187fence)—that if immigrants enter illegally and are not given propermedical care and schooling, disease and crime will increase. O'LearyBennett argues that in the absence of mechanisms of assimilation "wewill see spring up among us a generation of ignorant and troubled chil-dren who, lacking our common language and political and social ideals,will evolve into a huge, parallel underclass" (B7). The language of"springing up," and of "evolving," the complete Othering of those wholack "Our" political and social ideals "naturalizes" the illegal alien to adisaster akin to floods.The flood analogy came up more than once in the journalistic dis-

course on immigration during the debate over Proposition 187. For ex-ample, Sebastian Rotella writes that "for now the impact on the migra-tory flow manifests itself in myriad ripples" (B4). The discourse onimmigration seemed to force even "neutral" articles like this one intothe same rhetorical figures and metaphors of immigration-as-natural-disaster that the anti- immigration writers used. Rotella writes aboutTijuana's "floating population" of migrants from further South, whothreaten to overrun San Diego and points North in the same way thatwe see Simba and Mufasa overrun by a wildebeast stampede that killsMufasa.This meteorological representation of immigration overlaps with a

kind of bestiary of illegal immigration. Rotella describes his conversa-tion with border-crosser Estela Hernandez, whose "barefoot daughterscampered up and down the dirty concrete embankment" (emphasisadded). Reduced to animalistic figures, border-crossers in search of workare reduced to the chaotic movements of a feminized Third Worldthat threatens to consume a besieged First World. A bird-like figure in

Pride Lands 139

Rotella's bestiary provides sage words from the Third-World animalkingdom:

From his perch high above the battle ground of Smuggler'sCanyon, the fast-talking vendor named Ramon has watchedinnumerable countrymen go northward during the past sevenyears. In January, he said, they will seep over the Border Patroldeployment like the winter floods that periodically wash acrossthe canyon floor. . . .[The Border Patrol] are not going to stop it. The vendor said

"The people are many. Hunger is a powerful thing." (B4)Rotella uses his informant as a figure with bird's-eye view, who natural-izes and depoliticizes the movement of labor northward as a natural tidethat rises and falls, swells and floods. This depoliticization of global re-lations of capital and labor divides the world into the chaotic, evenscavenging character of the Third World, and the beleaguered charac-ter of the First.One L.A. Times article in particular reiterates the patriarchal theme

of The Lion King with uncanny faithfulness. The article covers a dem-onstration against Proposition 187 during which: "An anti-Proposition187 demonstrator who was kicked and beaten when he prevented otherdemonstrators from burning an American flag was presented with aU.S. flag Friday by a San Diego congressman who supports Proposition187." David Phillips, Jr., the defender of the flag, is commended by U.S.Rep. Randy (Duke) Cunningham (R-San Diego) for his "courage inrisking injury to protect the flag" (Perry A24). The description of thisavuncular, if not fatherly, gesture on the part of "Duke," is followed im-mediately by the information that "Phillips' father served in Vietnam."The father's proof of loyalty to country colors the son's involvementwith a group that would burn an American flag. The drama of savingthe flag and receiving one redeems the son from his potential transgres-sion. "Duke" Cunningham, whose nickname recalls the great Holly-wood image of masculinity, stands in fatherly relationship to David,a political science major. The article features a photograph of Phillipsholding the folded flag in front of him, looking contemplatively offframe. In the meantime, the message of the 187 protesters is ignored;indeed, it doesn't register. The story is not about any argument against187. It is rather a dramatization of a native son pitted against "about

140 Babak Ehhi

250" subversives. The narrative driving this news story is the return ofthe prodigal son, just as Simba returns from the land of hakuna matata:the restoration of national feeling along with the endorsement of thelaw of the father. The article contains both the spirit (David's father,the image of "the Duke,") and the letter (a state representative, Cun-ningham's endorsement of 187) of the father who tells the son—likeSimba's father—to "remember who you are." I'm not arguing, here, thatDavid Phillips really returns to the fold, but that the way the L.A.Times covers this story turns a political debate over immigration into amini-narrative of staying true to one's father's values.By contrast to how David Phillips—a white demonstrator—is repre-

sented, Latino anti-187 activists are represented as nameless groups.Numbers rather than individuals, they were either a nameless mass ofdemonstrators, groups of students leaving class upon the encourage-ment of unscrupulous teachers, masses of criminalized Mexicans, orshadowy victims of their parents' illegal immigration. One picture inparticular features a Latino demonstrator, his teeth bared at the camera,left fist raised in protest: an almost savage image framed at an acute an-gle (Feldman and Garcia A3). What Carl Guttierez-Jones has calledthe "criminalization of Chicana/os" in legal and journalistic discoursein Texas and California seems to be at work in the coverage of 187 bythe L.A. Times. In this stereotype of the Chicano as criminal, "theCortina Revolt (1859), the zoot suit-US servicemen's riots (1943), theChicano Moratorium (1969), and even the King verdict riots (1992)have all acted as defining moments for the Anglo establishment, inas-much as these legal interactions have been read in the media and thecourts as symptoms of a racially defined criminal penchant" (1). Muchof the reporting on Proposition 187 seems to continue in this tradition.For example, when James Coleman argued on September 12, 1994 thatpeople who enter or stay in the U.S. illegally are criminals "by defini-tion," he turned etymology into ontology; he naturalized a definition(B7). That definition, then, ceases to be a legal one; it ceases to havea history going back to the Guadalupe-Hidalgo Treaty of 1848, or toother moments in U.S. history when U.S. (white) identity is con-structed by the legal (or cultural) definition of otherness, but becomescommon sense. The figurative father-son relationship between DukeCunningham and David Phillips contrasts with these depictions of ille-gal immigrants and Latino demonstrators as criminals or angry subver-

Pride Lands 141

sives. The L.A. Times was not, of course, biased in any active way.Rather, what I'm pointing to is how a discourse of resentment—as Mc-Carthy argues—loops back and forth between seemingly "harmless"family entertainment, the "framing" of legislation, journalistic cover-age of public opinion, and the rhetoric of popular polemics. In this in-stance, immigrants were consistently "naturalized" as a force akin tofloods, while white fathers and sons were "naturalized" as the rightfulcitizens of California and the United States.

THE FAIR SON

Peter Brimelow also relies on the father-son image to frame his argu-ment against non-white immigration to the U.S. The epigram withwhich I begin this essay sums up the emotional rhetoric of Brimelow'sbook: "My son, Alexander, is a white male with blue eyes and blondhair. He has never discriminated against anyone in his little life (exceptpossibly young women visitors whom he suspects of being baby-sitters).But public policy now discriminates against him. The sheer size of theso-called 'protected classes' that are now politically favored, such asHispanics, will be a matter of vital importance for as long as he lives.And their size is basically determined by immigration" (11). LikeSimba, Alexander—or at least his economic future—is at the mercy ofdevouring non-White immigrants whom Brimelow falsely characterizesas chronically on welfare or as "naturally" criminal. To counter what hecalls anecdotal evidence of immigrant success—itself a "melting pot"variety of the White discourse of immigration—Brimelow refers toshootings and other crimes involving immigrants to marshal his anec-dotal evidence. Like the "Third World" threats to school children thatBarbara Coe rants about, these crimes constitute a physical and socio-economic threat to White "shiny" children from "aliens."Brimelow's central argument is that the open-door immigration pol-

icy of the liberal elite in Washington is dissolving the political power ofthe (white) people of the U.S. and assigning that power to a new peo-ple (of color). For Brimelow, the most recent immigrants to the U.S.are racially different from and even antagonistic to the predominantlywhite, Northern and Western European demography of the U.S. priorto 1965. Brimelow feels that the race-based restrictions of the 1920shad it just about right. According to his statistics, before 1965 nearly

142 Babak Ehhi

90 percent of Americans were white. Then he claims that "it is simplycommon sense that Americans have a legitimate interest in their coun-try's racial balance. It is common sense that they have a right to insistthat their government stop shifting it. Indeed, it seems to me that theyhave a right to insist that it be shifted back" (264). Beyond the fact thatthis statement relies on the fantasy that this 90 percent is homogeneousand that the remaining 10 percent has been culturally negligible, Bri-melow's argument relies on vague notions about race that date back tothe turn of the last century when social Darwinism was at its peak inthe United States." Brimelow seems not to be concerned with the factthat his call for a certain racial balance is tantamount to "ethniccleansing." He does realize, and is proud of the fact, that he echoes thecall for racist quotas expressed by politicians and demagogues of the1910s and '20s. Brimelow echoes the rhetoric of those anti-immigra-tion writers of the 1910s who argued, along with Madison Grant, that"Democratic ideals among an homogeneous population ofNordic Blood,as in England or America, is one thing, but it is quite another for thewhite man to share his blood with, or intrust his ideals to, brown, yel-low, black, or red men" (Introduction xxxii). As Daniel Kanstroom ar-gues, Brimelow echoes the ideas of Oswald Spengler who "adopted an'organic' view of culture, analogizing it to a living organism, with a con-comitant analogy of birth, growth, decline, and death" (307). Read asan allegory, The Lion King also echoes Spengler's notion of The Declineof the West. Brimelow fears a modern decline of the West.In one passage of Alien Nation Brimelow quotes the "California for

Americans" movement of the 1870s as an ideal to pursue today: "theChinese 'have never adapted themselves to our habits, mode of dress,or our educational system. . . . Impregnable to all the influences of ourAnglo-Saxon life, they remain the same stolid Asiatics ' that havefloated on the rivers and slaved in the fields of China for thirty cen-turies of time'" (214). Calling this statement "a highly rational andvery specific complaint about the difficulty of assimilating immigrantsfrom what was then a pre-modern society," Brimelow goes on to "con-cede" that "the Oriental [and it is amazing how dated much ofBrimelow's diction is] has modernized. Today, immigrants from the areaare often viewed (perhaps naively) as the most, well, 'Anglo-Saxon' ofthe current wave" (215). The parenthetical comment about the mis-

Pride Lands 143

guided acceptance of Asian immigrants again harks back to nativistand eugenicist discourse of the 1910s. Lothrop Stoddard's The RisingTide of Color, which argued that immigration from Asia and Southernand Eastern Europe to the U.S. amounted to racial suicide, included achapter on "Yellow Man's Land," a chapter that worried about naiveWestern views of a modernizing Japan. Jack London's 25 September1904 article for the San Francisco Examiner, "The Yellow Peril," per-forms a similar kind of rhetorical move in which the white race is callednaive for not recognizing the potential danger from the East with Kore-ans and Chinese as foot soldiers for the wily Japanese (340-50).What is most important about Brimelow's book, however, is not its

overt argument for race-based quotas, but rather, an emotional subtextthat sets up an alien threat to the rightful heirs of white patriarchy.Brimelow is British by birth but is proud of having gone through theappropriate legal avenues to gain U.S. citizenship; however, his mainsymbolic claim to U.S. citizenship is through his son, Alexander JamesFrank Brimelow. Little Alexander is recognizable as American by hislooks as his father suggests in his dedication:

"For Alexander James Frank Brimelow, born New York Hospi-tal, August 30, 1 99 1. This fair child of mine / Shall sum mycount . . .' —Shakespeare, Sonnet II."

This brief dedication sums up the emotional rhetoric of Brimelow'soften defensive book—his son's birth, heritage, and fair complexionmake him an "American" in the sense that nativists of the first fewdecades of this century imagined Americanness—as rooted in romanti-cally imagined racial characteristics of Anglo-Saxons and NorthernEuropeans. Indeed, the word "fair" can be read as the telltale heart ofracist anti- immigration sentiment in the 1990s. The group for whomBrimelow advocates most, the group that organized support for Proposi-tion 187, calls itself fair: Federation for American Immigration Re-form. Despite all of Brimelow's disclaimers—that he is not a racist, thathe is not a nativist, that he is only a proponent, like his countrymanThomas Paine, of common sense—despite all this, Brimelow's main cri-teria for membership in the American nation is fairness in the racialsense. His argument is that America is racially white and should bekept that way through strict immigration laws. His "fair" son embodies

144 Babak Elahi

what is "fair" about a call for new racist quotas in immigration legisla-tion. Indeed, Juan F. Perea calls Brimelow on his use of the term fair inhis dedication in Immigrants Out:

I dedicate this book to my spouse, Jan, and to my sons Alexan-der and Daniel. With hope that this nation will recognize thebeauty in their brown hair, and their beautiful hazel, brown,and blue eyes. And with hope that they shall be fair children,of full fairness and decency. May their fairness and compassionnot be limited to those who are fair only in complexion.

Perea, in what is clearly a witty counter-dedication to Brimelow's, rec-ognizes that at the heart of Brimelow's argument is not any logical orhistorically accurate understanding of immigration, but something morepotent: a myth of American whiteness based on a father-and-son mo-tif. What frames Brimelow's tables, "facts," and charts—his "commonsense," so to speak—is the image of a fair father passing on a white ter-ritory to a fair son, or the son passing it back to his father, as in thiscase. Brimelow sets up his son as the great white hope that will "sum hiscount." This white hope is threatened by an alliance between liberalgovernment and racially alien immigrants.

PETER BRIMELOW'S PEDIGREE

Brimelow's son even serves to illustrate a deterministic conceptionof "human nature." In arguing that it is not nationalism that leads towar but that all humans are prone to war and violence, Brimelow par-enthetically comments: "My little son jumped, then wheeled to look atme, his face alight with joy, when he first heard the firecrackers re-verberating through the Manhattan canyons in the week before JulyFourth. He was not yet two. But the frenzy to enlist at the outbreak ofwar in the Britain of 1914, in the North and South of 1861, was allthere" (229). This passage makes a (perhaps inadvertent) point aboutrace by recalling the determinism in sociological and historical dis-course of the first part of this century; it relies on the world view associ-ated with literary naturalism—something out of Frank Norris or JackLondon. But what is even more suggestive is Brimelow's use of WWI(what Lothrop Stoddard called the "White Civil War" [vi]) and theAmerican Civil War as proof of some innate human propensity to vio-

Pride Lands 145

lence. The reference to these historical markers inadvertently points toa specific kind of nationalism that Brimelow advocates, a nationalismbased on a notion of U.S. racial purity. These "memories," especiallythose of the Civil War, served in American discourses against Recon-struction at the turn of the century to unite the white race North andSouth. In attempting to define national belonging in his preface, Bri-melow quotes Abraham Lincoln: "The mass immigration so thought-lessly triggered in 1 965 risks making America an alien nation ... in thesense that Americans will no longer share in common what AbrahamLincoln called in his First Inaugural Address 'the mystic chords of mem-ory, stretching from every battle field and patriot grave, to every living heartand hearth stone, all over this broad land . . .'" (xix). The First InauguralAddress, as Brimelow must know, was conciliatory toward the Southand promised to uphold the fugitive slave laws. In fact, the speech wasso conciliatory that Thomas Dixon did not hesitate to use the samepassage in his racist anti-Reconstruction novel of 1905, The Clansmen,upon which D. W. Griffith based The Birth of a Nation.Thomas Dixon's novel—like Brimelow's polemic, like The Lion King

and like the affective subtext in the L.A. Times coverage of Proposition187—relies on a narrative of betrayal by a radical leader and thatleader's ushering in of an "alien, inferior race" (Dixon 47) into thefatherland. In the passage in which Dixon quotes Lincoln, Dixon'sAbraham argues against the radical majority leader Stoneman—whosuffers sexual decadence resulting from his association with an octo-roon woman—favoring a reconciliation with the South (in this fic-tional version, Lincoln's first inaugural address comes after the CivilWar). The fictional Lincoln argues for the colonization of "negroes" inthe "tropics" (46). Notice how similar the rhetoric of this passage is tonativist arguments, then and now: "The duty to exclude carries with itthe right to expel. . . . We can never attain the ideal Union our fathersdreamed, with millions of an alien, inferior race among us, whose as-similation is neither possible nor desirable" (46-47). Now, comparethese words of the fictional Lincoln to Brimelow's words concerningsome anecdotal evidence linking recent Third World immigrants toviolence: "is it really wise to allow the immigration of people [Brimelow isreferring to "a Pakistani," "a gang of Middle Easterners" and "a Jamai-can immigrant"] who find it so difficult and painful to assimûate into theAmerican majority? (7). Of course, this argument is logically fallacious—

146 Babak Elahi

millions of members ofthat "majority" find it difficult and painful to as-similate, and the great majority of immigrants adjust more or less suc-cessfully. But what is important is Brimelow's scapegoating, and the re-lation this passage bears to his fears about his son. His real fears comeout more clearly a few pages later when he discusses the difficulties hisson will face as a "white male with blue eyes" in a society dominated by"protected classes."Brimelow's non-fiction seems to be informed by the same mood of

resentment that informs Dixon's fiction. The "historical romance," asDixon called his Reconstruction trilogy, showed the betrayal of theSouth and of the Union by the traitorous Stoneman. Like Scar and likeBrimelow's democrats, Stoneman wants to gain power by allying him-self with an "alien, inferior race," and allowing that "race" to control aconquered territory—the South. What ultimately breaks up this un-holy alliance is the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, and the plot devicethat establishes the ??? is the return of the exiled son of the South, BenCameron, to restore his territory to its former economic and aristocraticglory. The basic structure here is the conquest of a sovereign territoryby the usurper, and ultimate retribution meted out by the return of theexiled heir, who reclaims a territory in the name and for the law of thefather. Dixon's and Griffith's popularization of this narrative structurecontinues to influence popular representations of the gendered andracialized boundaries of the nation, and the threats to them.

CONCLUSION

In 1915, Thomas Dixon wrote to Woodrow Wilson telling him thatthe President should attend the opening of The Birth of a Nation "notbecause it was the greatest ever produced or because his [Wilson's] class-mate [Dixon] had written the story . . . but because this picture madeclear for the first time that a new universal language had been in-vented" (quoted in Schickel 268). We might, along with Daniel Ber-nards and Clyde Taylor, call this "universal language" the discourse ofwhiteness. Daniel Bernardi has argued that the discourse of whitenesscontinues to place African, Latino, Native and Asian American identi-ties at the bottom of a White-supremacist order. Bernardi goes on toargue that early Hollywood film "voice"—specifically the Biograph and

Pride Lands 147

later films of D. W. Griffith—relied heavily upon the "White Family/White Women" narrative to tell tales of white supremacy. Specifically,Bernardi quotes Nick Browne's assessment of "Griffith's family dis-course" in which family fragmentation "either by loss of a child or bythe death, separation, or violation of a parent" is caused by "a savageand lustful non-white male" ( 1 19). As both Bernardi and Taylor argue,this kind of narrative—threat to the white family from a savage andlustful non-white—continues to be part of Hollywood film discourse.Scar's physical weakness ("bad back, you know," as he puts it), and

sexual ambiguity recall traditional "markings" of monstrous villains inAmerican political demonology. Michael Rogin has defined Americanpolitical demonology as the "creation of monsters as a continuing fea-ture of American politics by the inflation, stigmatization, and dehu-manization of political foes" (xiii). Rogin identifies Austin Stone-man—the Congressional leader in Thomas Dixon's The Chnsman andD.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation—as an early film version of thiskind of monster. Stoneman is crippled and sexually/racially dissipatedthrough his illicit relations with a mulatto. Furthermore, Stoneman isbased on Thaddeus Stevens who, according to one of Dixon's sourcesfor his novel—Woodrow Wilson's historical propaganda—enforced a"policy of rule or ruin . . . [that] put the white South under the heel ofthe black South" (Wilson quoted in Rogin 193). Stoneman, in Dixon'snovel and Griffith's film, allows the South to be ruled and ruined by "analien, inferior race" (47). 12Scar, it seems to me, is an animated version of this monster of polit-

ical and filmic demonology. Like Stoneman he is physically lame andsexually ambiguous. As we learn in the sequel to The Lion King—SimbasPride—Scar's weakness might be connected to his illicit relations with alioness of an alien pride, the "outlanders." Finally, and most impor-tantly, Scar, like Stoneman, is an unscrupulous insider who ushers in an"alien, inferior race." The alliance of Scar and the hyenas is a cinematicrepresentation of broader discourses of nativism and white resentment,discourses that have been renewed repeatedly over the past hundredyears or more. Just as Dixon and Griffith used the novel and film tovoice a broader reaction against the Reconstruction of the 1 860s and1870s, so The Lion King allegorizes and Alien Nation directly expresseswhite resentment about the civil rights movement of the 1960S-70S

148 Babak Eiahi

and the immigration of people from non-European countries sincearound the same time.

Rochester Institute of Technology

NOTES

I'd like to thank Mark Berrettini, Joanne Bernardi, Ed Chan, Melinda Knight,John Michael, Frank Shuffelton, and Sharon Willis for reading and discussing thisessay with me.

? . Much work has been done on reception of Disney animation; deCordova hasargued that the connection of consumer products (toys, clothing, bedding, wall-pa-per) to film production that has been standard procedure at Disney since the '30shas produced "Disney animation's uncontested address to children" (203). Andeven though many of Disney's recent releases have been violent, they have notbeen "expected to have any serious extra-cinematic reference or effect" (85).Disney, then, has had an overwhelming endorsement from parents of the socio-economic middle and the political center. (The apparent agreement about Disneyby those on the far right and far left needs to be looked into at some point.)

2. In his autobiography, Michael Eisner—Disney's ceo—describes how JefferyKatzenberg felt he should step into Well's shoes like a son following his father'sfootsteps (297). See also Brown; "Disney's Virtual President." Eisner himself felt aless-than-fraternal connection with Katzenberg. He documents their discord in hisautobiography (171-200, 293-318). See also "Katzenberg." In fact, one of Katzen-berg's more recent projects—The Prince of Egypt, which was released by Katzen-berg's partnership with Stephen Spielberg and David Geffen of DreamWorks, is, inmy opinion, an allegory for his break from Disney with himself in the role of Mosesand Eisner as Ramses. At any rate, Katzenberg's real relationship with Wells wasnot filial by any means—most sources agree that he simply wanted Wells' job. Butthe July 1994 Premiere article depicts his reaction to Wells' death almost as one of ason mourning the death of a father.

3. For further discussions and definitions of animation as art and industry, seeFurniss 3-12. For a discussion of animation as a form, technique and industry, seeDenslow.4. In addition to Roth, also see a few of the large number of articles and books

recently published on race, class, gender, sexuality, and nation in Disney produc-tion (both old and new): Falperin; Kuenz; Luckett; and Zipes.

5. For a discussion of the pseudo-science of degeneracy, see Dijkstra's examina-tion of Max Nordau's Degeneration (228-231).6. Dijkstra argues convincingly that "at the opening of the new century, biology

and medicine set out to prove that nature had given all women a basic instinct thatmade them into predators, destroyers, witches—evil sisters" (3). Dijkstra's book"provides a genealogy for the cat woman, tiger woman, praying mantis, snake-fanciers, and man-eating tarantulas still prowling about our movie theaters, televi-sion screens, best-seller lists, and comic-book stores" (5). Dijkstra goes on to link

Pride Lands 149

this image of the predatory female to representations of the racially dangerous:"Twisted 'erotic' fantasies of gynecide had opened the door to the realities of geno-cide" (4). I want to borrow Dijkstra's connection of this fantasy of the monstrouswoman to the fantasy of predatory races. For example, Dijkstra's reading of ThomasDixon's "Trilogy of Reconstruction" suggests that The Lion King has an infamouspedigree. In Dixon's The Clansman, Stoneman, as we shall see shortly in some de-tail, enters into "an ungodly alliance" with "Reconstructed" blacks in the south(183). These "bestial hordes" invade the aristocracy of the white South only to hedefeated, ultimately, by the "glorious" return of the Southern White son as leader ofthe KIu Klux Klan (184).

7. The feminization of "terra incognita" in Hollywood films like Raiders of theLost Ark comes from a vision and visualization of empire dating back to techniquesof cartography first developed in the 16th century. See Shohat and Stamm.

8. Fleming tepotts on the dispute within Disney studios: "Sources say that thesequel to the "Lion King" originally called for a romance between two young lionswho are second cousins, hut Disney ceo Michael Eisner was troubled by the notionof incest" (4).

9. Not all of these L.A. Times articles argued against immigration or for Propo-sition 187. However, even those opposed to the discontinuation of social servicesto immigrants (the purported purpose of Prop 187) continue to depict immigrationas a flood that will destroy California's economy. See, for example: Chavez andBanks; Coleman; Ibarra; Lat and Bastillo; Lopez; Mahony; McDonnell; McDonnelland Lopez; Prince; PyIe and Feldman; PyIe and Shuster; and Romero.

10. The words of Pete Wilson appeared over and over again in the L.A. Timesduring the political campaign of summer and fall in 1994, and in a few importantinstances, he represents himself as the state's fathet figure. Wilson saw himself asthe messenger of Proposition 187, and the L.A. Times describes his message in thefollowing way: "The Message: the widely held perception that an 'invasion' of ille-gal immigrants is causing economic hardship and eroding the lifestyles of U.S. citi-zens and authorized immigrants." As for the messenger: in accepting his re-electionto Governor on the same day that 187 passed into law, Wilson gave the followingstatement: "What you have won today is a victory—a victory for working Califor-nians, those who work hard, play by the rules, pay their taxes, raise their childten toobey the law, and respect themselves and others" (L.A. Times Nov. 9, 1994, A3)."Working Californiens" is a phrase that points conspicuously to its binary oppositewithin the 187 discourse as it had developed through the late summer and early fallof 1994—non-Californians on the dole. This demon has been banished not somuch by 187, but by Wilson as the state's champion. What he has championed isthe defeat of a demonized group that does not "play by the rules, pay taxes," nor"raise [its] children to obey the law." Furthermore, Pete Wilson's television ads forthe Governor's race were centered around immigration as he contrasted himselfwith Kathleen Brown, arguing that he wanted "to use the money spent on illegalsto take care of California's kids" (L.A. Times 16 Oct. 1994, A25). As the leader ofa State whose economy has relied on the cheap labor of immigrants (legal or othet-wise), Wilson's claim that the children of immigrants threaten the life-blood of the

I50 Babak Ehhi

children of citizens is similar to The Lion Kings narrative of the predator becomingprey, and the need to restore the proper order of things.

1 1. For further analysis of Brimelow's use of eugenicist ideas see Kanstroom. Forfurther comparison of today's nativism with earlier manifestations of nativism andxenophobia, see Feagin; and Johnson.

12. Dijkstra's discussion of Dixon's novel is especially useful in detailing theway in which racist-sexist ideologies narrate the dissipation ofWhite masculinity asit is consumed by dark women (184).

WORKS CITED

Bernadi, Daniel, ed. The Birth of Whiteness: Race and the Emergence of U .S. Cinema.Ed. Daniel Bernadi. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

---------- . "Introduction: Race and the Emergence of U.S. Cinema." Bernadi 1-14.---------- . "The Voice of Whiteness: D. W Griffith's Biograph Films (1908-1913)."Bernadi 103-28.

Brimelow, Peter. Alien Nation: Common Sense About America's Immigration Disaster.New York: Random House, 1995.

Brown, Corie. "The Third Man." Premiere Nov. 1994: r 10-16.Chavez, Leo. "Immigration Reform and Nativism: The Nationalist Response to theTransnationalist Challenge." Perea 61-77.

Chavez, Stephanie, and Sandy Banks. "Proposition 187 Is Sore Subject for IllegalImmigrant Students." L.A. Times 17 Sep. 1994: Ai+.

Coleman, James. "Illegal Immigrants Are, by Definition, Criminals." L.A. Times 12Sep. 1994: B7.

deCordova, Richard. "The Mickey in Macy's Window: Children, Consumerism,and Disney Animation." Smoodin 203-13.

Denslow, Philip Kelley. "What is animation and who needs to know?" Pilling 1-4.Dijkstra, Bram. Evil Sisters: The Threat of Female Sexuality and the Cult of Manhood.New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

"Disney's Virtual President." Business Week Nov. 14, 1994: 39.Dixon, Thomas, Jr. The Clansman. An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. Lex-ington: University of Kentucky Press, 1970.

Eisner, Michael. Work in Progress. New York: Random House, 1998.Falperin, Leslie. "The Thief of Buena Vista: Disney's Aladdin and Orientalism."Pilling 137-42.

Feagin, Joe R. "Old Poison in New Bottles: The Deep Roots of Modern Nativism."Perea 44-59.

Feldman, Paul, and Jon Garcia. "Emotions High at Last-Minute Protest." L.A.Times 8 Nov. 1994: A3.

Fleming, Michael. "It's All Relative in 'Lion King' Sequel." Variety 9-15 Sep. 1996:4-6.

Furniss, Maureen. Art in Motion: Animation Aesthetics. London: John Libbey, 1998.

Pride Lands 151

Gavin, Rosemarie. "The Lion King and Hamlet: A Homecoming for the ExiledChild." English Journal 85.3 (1996): 55-57.

Goux, Jean-Joseph. Symbolic Economies: After Marx and Freud. Ithaca: CornellUniversity Press, 1990.

Grant, Madison. Introduction. Stoddard xi-xxxii.Gutierrez-Jones, Carl Scott. Rethinking the Borderlands: Between Chicano Culture and

Legal Discourse. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.Ibarra, Rafael. "Looking at Proposition 187 Through the Eyes of an Illegal Valedic-torian." L.A. Times 6 Nov. 1994: M6.

Johnson, Kevin. "The New Nativism: Something Old, Something New, SomethingBorrowed, Something Blue." Perea 165-89.

Kanstroom, Daniel. "Dangerous Undertones of the New Nativism: Peter Brimelowand the Decline of the West." Perea 300-17.

"Katzenberg: No Longer Satisfied Being 'Eisner and Son.'" Newsweek 28 Sept. 1998:58-60.

Kuenz, Jane "It's a Small World after AU: Disney and the Pleasure of Identifica-tion." The South Atlantic Quarterly 92.1 (1993): 63-88.

Lat, Emelyn Cruz, and Miguel Bustillo. "Proposition 187 Sparks More High SchoolWalkouts." L.A. Times 22 Oct. 1994: B2+.

Lion King, The. Dirs. Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff. Buena Vista, 1994Lion King U: Simbas Pride, The. Dir. Darrell Rooney. Buena Vista, 1998London, Jack. "The Yellow Peril." Jack London Reports. Ed. King Hendricks and Irv-ing Shepard. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970. 340-50.

Lopez, Robert J. "7,000 Attend Protest Denouncing Proposition 187." L.A. Times31 Oct. 1994: ¦

Luckett, Moya. "Fantasia: Cultural Construction of Disney's 'Masterpiece.'"Smoodin 214-36.

Mahony, Roger. "Protect the Children from Politics." L.A. Times 25 Oct. 1994:McCarthy, Cameron, et al. "Danger in the Safety Zone: Notes on Race, Resent-ment, and the Discourse of Crime, Violence and Suburban Security." CulturalStudies 11 (1997): 271-300.

McDonnell, Patrick. "Spanish-Language Media Fight Initiative." L.A. Times 7 Oct.1994: Bi+.

McDonnell, Patrick, and Robert J. Lopez, "70,000 March Through LA AgainstProposition 187." L.A. Times 17 Oct. 1994: Bi.

Micheals, Walter Benn. Our America: Nativism, Modernism, and Pluralism. Dur-ham: Duke University Press, 1995.

Mitchell, Juliet, and Jacqueline Rose, eds. Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and theEcole Freudienne. 1982. New York: Pantheon-Norton, 1985.

Noake, Roger. Animation Technique: Phnning and Producing Animation with Today'sTechnologies. Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books, 1988

O'Leary Bennett, Brian. "An Initiative Even Conservatives Can Hate." L.A. Times7 Oct 1994: B7.

Perea, Juan E, ed. Immigrants Out! The New Nativism and the Anti-Immigrant Impulsein the United States. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

152 Babak Elahi

Perry, Tony. "Anti-187 Protester Honored for Halting Burning of Flag." L. A. Times5 Nov. 1994: A24.

Pilling, Jayne, ed. A Reader in Animation Studies. London: John Lihbey, 1997.Prince, Ron. "Americans Want Illegal Immigrants Out." L. A. Times 6 Sep. 1994: