PÉTREQUIN P., ERRERA M., CASSEN S., GAUTHIER E., HOVORKA D., KLASSEN L. et SHERIDAN A., 2011.- From...

-

Upload

univ-fcomte -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of PÉTREQUIN P., ERRERA M., CASSEN S., GAUTHIER E., HOVORKA D., KLASSEN L. et SHERIDAN A., 2011.- From...

FROM MONT VISO TO SLOVAKIA:THE TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE FROM GOLIANOVO

P. PÉTREQUIN1–M. ERRERA2–S. CASSEN3–E. GAUTHIER1–D. HOVORKA4–L. KLASSEN5– A. SHERIDAN6

1 Laboratoire de Chrono-environnement, UMR 6249, UFR Sciences, 16, route de Gray 25030 Besançon, France2 Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren, Belgique, et Musée régional de Préhistoire, Orgnac-l’Aven, France

3 Laboratoire de recherches archéologiques, université de Nantes, UMR 6566 BP 81227, 44312 Nantes Cedex 3, France4 Constantine the Philosopher’s University, Andeja Hlinku 1, Nitra, Slovak Republic

5 Moesgard Museum, 8270 Højbjerg, Denmark6 Archaeology Department, National Museums Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EH1 1JF, UK

E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected];[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62 (2011) 243–2680001-5210/$ 20.00 © 2011 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

DOI: 10.1556/AArch.62.2011.2.1

Abstract: Two fragments of large jadeitite axeheads were discovered in a Lengyel enclosure at Golianovo (Republic ofSlovakia), close to Nitra. Spectroradiometric analysis and macroscopic characteristics indicate that, in all probability, these two ar-tefacts – which are exceptional in this region of Europe – had come from the Neolithic quarries on Mont Viso, in the Italian Alps, some950 km away as the crow flies.

The two axehead fragments from Golianovo probably belong among the early Durrington type axeheads, which appear atthe end of the 6th millennium BC. They were found associated with a large enclosure of the early Lengyel Culture (the Lužiankyphase), dating to the beginning of the 5th millennium.

Within a Europe that was divided between a ‘jade Europe’ in the west and a ‘copper Europe’ in the east, the Alpine axe-heads from Golianovo constitute an important ‘route marker’ illustrating the circulation of socially valorised objects from northernItaly towards southeast Europe around 5000 BC. These early contacts are confirmed by the presence of axeheads made from Alpinejades in the enclosure at Kamegg and in the cemetery at Friebritz-Süd in Lower Austria, at Semerovce in Slovakia, and probably alsoin the cemetery at Alsónyék-Kanizsa in Hungary.

Keywords: jadeite, axeheads, exchange, Lengyel, Golianovo

From the end of the 6th to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, axeheads of ‘Alpine jades’ (jadeitites,omphacitites, eclogites and certain amphibolites) circulated in their thousands over considerable distances in wes-tern Europe. At the peak of the phenomenon – that is to say, from the middle of the 5th millennium until the begin-ning of the 4th these socially valorised axeheads, both large and small, reached as far as Denmark, Ireland andScotland, Brittany, Spain and the Atlantic fringe of the Continent (Fig. 1). Towards the south, they appeared in Cor-sica, Sardinia, the Italian peninsula and Sicily. An easterly extension, as far as the shores of the Black Sea at Varna,Durankulak and Svoboda, has recently been recognised, with the Svoboda hoard constituting the largest hoard ofAlpine axeheads known from the whole of Europe.1 The recognition of this eastwards extension, via Croatia,2 haspermitted us to trace an axis along which objects and ideas travelled, linking the Black Sea, Varna, the Balkans,North Italy and the Gulf of Morbihan – a fundamental axis of contacts between the Neolithic west and the Chalco-lithic east (in the Balkans), whose existence had previously been suspected.3

Overall, the circulation of Alpine axeheads took place over a distance of 3,000 kilometres from west to eastas the crow flies (from Brittany to the Black Sea) and 1,900 kilometres from the north to the south (from Denmarkto Sicily ; measurements made using Google Earth). Thus, during the apogee of the phenomenon – that is to say,between 4700 and 3700 BC, over the course of a millennium – at least 1820 axeheads longer than 13.5 cm (with a

1 TSONCHEV 1946; ERRERA et al. 2006; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN

et al. in press 2011a.

2 MILOSEVIĆ 1999; PETRIĆ 1995; PETRIĆ 2004.3 CASSEN 2003.

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 243

few as long as 46 cm) were mobilised. This represents an overall weight of around 900 kg of precious jades, not coun-ting the several thousand smaller axeheads, shorter than 13.5 cm, which were also circulating.

1. ORIGIN OF THE ALPINE JADES

Ever since A. Damour4 first defined the mineral jadeite, on the basis of Neolithic axeheads discovered inFrance, there have been uncertainties – and many hypotheses – about the origin of the Alpine jades. It was Damour5

who is to be credited with claiming Mont Viso – in the Italian Alps, 70 km south-west of Turin – as the possible ori-gin of the jades used during the European Neolithic. Moreover, several potential source areas on Mont Viso were

Fig. 1. Distribution of large (>13.5 cm) axeheads of Alpine jades, of all types. CAD: E. Gauthier and J. Desmeulles. Document: JADE, P. Pétrequin

4 DAMOUR 1863; DAMOUR 1865. 5 DAMOUR 1881.

244 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 244

pointed out by the Italian pioneers of Alpine geology, in particular S. Franchi,6 who was familiar with the series ofaxehead roughouts found at Alba, Cuneo,7 and also V. Novarese8 and A. Stella.9 According to the research underta-ken by these researchers who were used to working in mountainous terrain, the Mont Viso massif, and also that ofBeigua (the geologists’Voltri Group), to the north of Genoa, must have been exploited during the Neolithic.

Later on, despite the increasing sophistication of the analytical methods developed for identifying the rocksused to make Alpine axeheads,10 the question of the specific origin of the Alpine jades remained stubbornly unclear,for three reasons: because this research was not accompanied by new prospection of the terrain by the Neolithic ar-chaeologists; because no solid body of raw material specimens was being built up; and because of the idea that Neo-lithic people were only using secondary deposits and erratic cobbles.11 The idea of using secondary sources did notsuffice to explain the very long distance exchanges of Alpine axeheads, which extended as far as 1,650 km as thecrow flies. (This distance was calculated using Google Earth.)

It was not until May 2003 when the large Neolithic extraction and working areas on Mont Viso were dis-covered, between 1,500 and 2,400 metres above sea level,12 together with evidence for smaller-scale activities on Bei-gua.13 Thus, it had been during summer, high-altitude expeditions during the Neolithic that the precious, tough andlight-capturing Alpine jades were exploited, in a context that had been highly ritualised.14 This accorded with thetheoretical models that had been constructed on the basis of ethnographic research.15 This discovery in 2003 allo-wed the real work of research to begin, going beyond the stage of petrographic and mineralogical analysis of Neo-lithic axeheads.

Our research, in contrast to what had been done before, focused on:– the construction of a reference collection of raw material specimens of Alpine jades (which currently

comprises over 400 specimens16)– the undertaking of a comparative analytical method that is non-destructive, namely diffuse-reflectance

spectroradiometry17

– the systematic recording of large Alpine axeheads across the whole of Europe (Fig. 1), to develop a spa-tial and chronological approach based on a new typological classification of axeheads18

Today, we can say that the phenomenon of producing and circulating large jade axeheads:– began around 5400–5300 BC with the production of small adze heads, and also of highly polished axe-

heads and ring-discs of jadeitite;– developed from 4800 BC with a larger-scale production of long adze heads, mostly of eclogite or om-

phacitite, often very long; these spread over the southern half of France and reached Brittany and the Gulf of Mor-bihan, following two ancient networks over which the Cardial Neolithic had spread – one route following the valleysof the Rhone and the Yonne, the other along the Atlantic façade;

– reached its apogee around the middle of the 5th millennium with the large-scale production of axeheads,mostly of jadeitite;19 these products eventually reached most of western Europe, in particular Germany, followingthe expansion of the Michelsberg culture from the Paris Basin,20 and Britain and Ireland, as part of the Neolithic co-lonisation of this archipelago;21

6 FRANCHI 1900; FRANCHI 1904.7 TRAVERSO 1898–1901–1909.8 NOVARESE 1903.9 STELLA 1903.

10 CAMPBELL–SMITH 1963 and the English school, such asWOOLLEY 1983; followed by COMPAGNONI et al. 1995; RICQ–DE

BOUARD 1996; D’AMICO et al. 1995; D’AMICO et al. 2003; GIUSTETTO–COMPAGNONI 2004.

11 RICQ–DE BOUARD 1996; VENTURINO GAMBARI 1996;D’AMICO–STARNINI 2006.

12 ERRERA 2004; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. 2005; PÉTRE-QUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. 2007a; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. 2007b ;PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. 2008.

13 PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. in print 2011.14 PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. 2009; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN

in print 2011.

15 PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN 1993; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN

2006; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. 2002; PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. 2003;PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN et al. 2006.

16 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.17 ERRERA 2002; ERRERA et al. 2006; ERRERA et al. 2007;

PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. 2005; PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. 2009;PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA in print 2011; SHERIDAN et al. 2010.

18 PÉTREQUIN–CROUTSCH et al. 1998; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN

et al. 2002; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. in print 2011b; PÉTREQUIN–ER-RERA et al. 2006; PÉTREQUIN–SHERIDAN et al. 2008.

19 PÉTREQUIN–SHERIDAN et al. in print.20 JEUNESSE et al. 2003.21 PÉTREQUIN–SHERIDAN et al. 2008; PAILLER–SHERIDAN

2009.

245TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 245

– thereafter it declined slowly during the first half of the 4th millennium, ending with the production ofsimple workaday wood-working tools that were less socially valorised than the earlier axeheads.22 The distributionof these tools progressively shrank until it extended only over several hundred kilometres.

Thus, the production of Alpine jade artefacts followed a pattern that is found around the world and acrossmany cultures, whereby a tool is, at one point, removed from its initial technical function and becomes the objectof a social reinterpretation.23 During the expansion and the apogee of the Alpine jade system – when the two cen-tres of social intensification, the Morbihan in the west and Varna in the east, were acquiring large jade axeheads (Fig.1) – these precious ‘object-signs’ were incorporated into a nexus of religious beliefs that underlay their social use(as is the case with the ethnographic examples from New Guinea24). The movement of these objects did not followa simple ‘down the line’ pattern of diffusion, where the number of items decreases with distance from the source.25

If the production and dissemination of Alpine jade axeheads seems to us to be a fundamentally novel phe-nomenon, albeit one with indirect links to the ‘copper and gold Europe’ of the east,26 there is still much that remainsto be discovered about the diffusion of these axeheads into central Europe and the Balkans, that is, the heart of thearea involved in the earliest copper metallurgy.

Two axeheads found at Golianovo (Republic of Slovakia) therefore represent a good way to explore ingreater detail an axis of diffusion that stretched across the Alps from north Italy towards Austria, Slovakia, the CzechRepublic and ultimately Hungary.

2. MINERALOGICAL ANALYSES OF JADE AXEHEADS IN AUSTRIA, SLOVAKIA AND THE CZECH REPUBLIC

The first polished tools in jadeitite and nephrite were described in the Republic of Slovakia from the mid-20th century. Numerous authors27 supposed that these rocks came from the Silesian part of the Czech massif (southof Poland and north-east of the Czech Republic). After detailed petrographic study, it became clear that the majo-rity of these polished axeheads were in fact of calc-amphibolite (nephrite); items of jadeitite are much rarer. Usinga polarising microscope and X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrometry, J. Schmidt and J. Štelcl28 were able to identifyeight axeheads of jadeitite among the collections of the Museum of Moravia at Brno; six are small polished axeheadsbetween 5.5 and 10.6 cm long, and two are fragments.

The raw material used for these artefacts is green, with yellow or brown tinges and sometimes with lighterflecks. The analyses showed that the rock was mostly of jadeite (sometimes with a laminar structure), with other ac-cessory minerals, namely zircon, sphene, paragonite (?) and epidote. The XRD spectra revealed the presence of py-roxenes of the jadeite-diopside series, together with other minerals: chlorite, anatase and very probably actimite andanalcime.

In Austria, a single fragment of an Alpine axehead was discovered in the enclosure of Kamegg and identi-fied as being of jadeitite.29 These initial analyses revealed a zonal structure with jadeite crystals whose centres aredarker than the periphery; electron microprobe analysis revealed the presence of accumulations of sphene and, morerarely, epidote and opaque minerals. An Alpine origin had been proposed for this axehead, although the precise lo-cation could not be identified due to the lack of relevant reference material from the Italian Alps. A more recent studyof the Kamegg axehead, using spectroradiometric analysis to enhance the information gained through microscopy,has allowed us not only to identify the rock more specifically as an omphacitite, but also to pinpoint the area of ex-traction in the Viso massif (in the Vallone Bulè).30

In Slovakia, several hundred thin sections have been made (Note 1), and other forms of analysis applied,as used in geoscience. Only three jadeitite axehead fragments have been identified: one from Sobotište and the twofrom Golianovo which are the subject of this contribution. A fourth fragment, also found at Golianovo but held inprivate hands, was not available for analysis.

22 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. 2006.23 LEMONNIER 1986; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN 2006.24 GODELIER 1996; PÉTREQUIN–PÉTREQUIN 2006.25 RENFREW 1975.26 KLASSEN–CASSEN et al. in print; KLASSEN–DOBEŠ et al. in

print.

27 See SCHMIDT–ŠTELCL 1971 for references.28 SCHMIDT–ŠTELCL 1971.29 PŘICHYSTAL–TRNKA 200130 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print.

246 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 246

The axehead fragment from Sobotište (in Trnava county, around 60 km to the north of Bratislava) is a sur-face find and cannot be dated directly.31 This small polished axehead fragment measures 7.5 cm in length and 5.0cm wide at the cutting-edge. The colour is a turquoise green. On the surface, the rock has small pits, the largestmeasuring 1 mm across. From examination in thin section and through chemical analysis, it would appear that thezoned structure of pyroxene, from the centre towards the edge of each tiny crystal of jadeite (smaller than 0.2 mm),is highly characteristic: the jadeite is in the centre, while the outer edge is of omphacitite.32 The accessory mineralsinclude zircon, rutile, xenotime and those belonging to the epidote family. The result of the analyses has allowed usto show that the Sobotište axehead is very similar to certain jadeitite axeheads found in north Italy, in particularthose from the site of Pozzuolo del Friuli / Sammardenchia (Friuli).33

This important finding has allowed us to propose an origin for this axehead in the western Alps,34 since nojadeitite exists in the eastern Alps, the Bohemian Massif or the Carpathians.

An initial analysis of the two axeheads fragments from Golianovo35 led the researchers to the same con-clusions, although without being able to pinpoint the potential area of origin due to the lack of reference material.

3. THE CONTEXT OF THE GOLIANOVO AXEHEADS

The site of Golianovo (Nitra county, Republic of Slovakia), close to Nitra, is a large circular enclosure withthree concentric ditches, extending over a maximum diameter of 230 m, according to old photographs.36

Most of the archaeological evidence, including the two axeheads in question, had been collected from thesurface during prospecting by amateurs.

The pottery – some of which was found during archaeological trial-trenching – can be attributed to theearly phase of the Lengyel culture, and more specifically to the Lužianky group (phase LgK Ia),37 dating to the ope-ning centuries of the 5th millennium BC. This chronological phase marks the beginning of the use of painted pot-tery in the Lengyel culture, with its dark designs on a red background, possibly around 4900 BC.

Among the complete and fragmentary polished axeheads that have been gathered at the Golianovo enclo-sure, there are examples made of various kinds of greenschists (amphibole schists), of serpentinite, of silts, of quart-zites and of gneiss;38 these objects correspond to utilitarian axeheads for working wood. The two fragments of Alpinejade axeheads therefore constitute the exception in this assemblage of relatively common, regionally-available rocks.Furthermore, outside of Italy, these may be the earliest known Alpine axeheads.

4. THE FIRST AXEHEAD FROM GOLIANOVO (INV. JADE 2008_323)

This is a fragment from the butt end, not of an axehead, but in fact of an adze (Fig. 2), with an asymmetri-cal, biconvex section in the form of a thin ‘D’. The length is currently 4.9 cm; before thin-sectioning, it had been5.2 cm. The width is 3.8 cm and the thickness, 1.2 cm. The polish is very regular and glossy. The surface, markedlycracked and whitened, bears the marks of having been destroyed by fire, recalling three axeheads of the same type,also in jadeitite, that had been found at Sammardenchia (Friuli, Italy) (SAM 77, 85 and 125/197).39 This allows usto propose that certain imported Alpine axeheads had been deliberately destroyed by burning, a phenomenon thathas often been noted among axeheads found in non-domestic contexts.40

The jadeitite is a pale green colour, with a markedly convoluted internal structure and occasional light greenor brown speckles. The characteristics of the thin section and the results of the analyses are described by D. Ho-vorka.41 Being familiar with the variability and diversity of the jadeitites in the Alps, we noted the marked presenceof rutile, which is statistically one of the most abundant minerals in the jadeitites of Mont Viso – more so than in those

31 HOVORKA et al. 1998; HOVORKA et al. 2008; SPIŠIAK–HOVORKA 2005.

32 HOVORKA et al. 1998.33 D’AMICO et al. 1995; D’AMICO et al. 1997.34 HOVORKA et al. 1998.35 SPIŠIAK–HOVORKA 2005; HOVORKA et al. 1998.

36 BÁNESZ–NEVIZÁNSKY 1993; KUZMA–TIRPÁK 2001.37 NOVOTNÝ 1962.38 KUZMA–TIRPÁK 2001; BŘEZINOVÁ et al. 2002.39 Compare D’AMICO et al. 1997.40 LARSSON 2000.41 HOVORKA et al. 2008.

247TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 247

248 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

Fig. 3. Comparison of the spectrum for Golianovo JADE 2008_323 with seven spectra from the JADE reference collection of Alpine rocks.The closest similarities are with the specimens from Mont Viso,

in particular those from the Neolithic working areas at Oncino/Bulè and Porco. Document: M. Errera

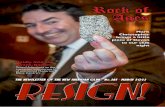

Fig. 2. Golianovo (Slovakia): butt of large axehead with an asymmetrical biconvex section, heavily burnt, jadeitite. Spectroradiometric analysis:KLAS_484 and KLAS_485. Inventory N: JADE 2008_323. Photo: P. Pétrequin

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 248

249TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

Fig. 5. Comparison of the two spectra of Golianovo JADE 2008_323 with spectra from the database of large Alpine axeheads from Europe.Document: M. Errera

Fig. 4. Comparison of the spectra of Endmembers _157, _158 and _162 (to which the Golianovo axehead JADE 2008_323 belongs)with spectra from the JADE reference collection of Alpine rocks. An origin in the Viso massif is highly probable. Document: M. Errera

Endmember type Comparanda from theJADE reference database Provenance of the raw material samples

Endmember_157 BMus_350, _351 Onci_163 0,909Yes(but)

Oncino; Point 124, Porco, terrace above Abri Jadéite.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 20/05/07

Alpn_104 0,898Yes(but)

Bobbio Pellice; Col Barant North, point E.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2008

Onci_160 0,894Yes(but)

Oncino; point 124, Porco, terrace above Abri Jadéite.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 10/05/07

Onci_147 0,904Yesbut

Oncino, 108/12B; Bulè, Circle of Blocks, Shelter C,№ 10. Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2007

Endmember_158 Udin_101, _102 Onci_140 0,882 YesOncino; 108/12B; Bulè, Circle of Blocks, Shelter C№ 3. Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2007

Alpe_548 0,877Yes(but)

Oncino; Vallone Bulè, Col de Luca 1.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 13/07/03, 2003g

Endmember_162 KLAS_009, _010 Onci_014 0,815Yes(but)

Oncino; Porco, trial trench on terrace above Abri Jadéite.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 23/09/04

Alps_596 0,842Yesbut

LM 145: Ponte Erro; bed of the Erro, 100 m above bridge,in alluvial fan of the river Orba.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 29/04/2005

Alpn_000 0,837Yesbut

LM 434: Oncino; vallon des Milanais, Point 171.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2007

Alpe_723 0,812Yesbut

LM 413: Bussoleno (Val de Susa), Trte Gravio.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2002

Onci_086 0,795Yesbut

Oncino, Bulè; Point 81, Pyramide.Collected by P. Pétrequin, 2006

Onci_147 0,784Yesbut

Oncino; Point 108/12B; Bulè, Circle of Blocks,Shelter C № 10. Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2007

Onci_160 0,781Yesbut

Oncino; Point 124, Porco, upper-terrace aboveAbri Jadéite. Collected by P. Pétrequin. 10/05/07

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 249

Fig.

6.C

ompa

riso

nof

the

spec

tra

ofE

ndm

embe

rs_1

57,_

158

and

_162

(to

whi

chth

eG

olia

novo

axeh

ead

JAD

E20

08_3

23be

long

s)w

ithsp

ectr

afr

omth

eda

taba

seof

larg

eA

lpin

eax

ehea

dsfr

omE

urop

e.D

ocum

ent:

M.E

rrer

a

250 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AXEHEAD

№FINDSPOT

SPECTRUM

№ROCKTYPE

basedonmacroscopicexamination

MUSEUMorCOLLECTION

End

mem

ber_

157

2008

_007

0ST

RA

TH

BL

AN

ESt

irlin

gD

umbr

ock

BM

us_2

32,

BM

us_2

33Sa

ccha

roid

alja

deiti

te,s

light

lybr

ecci

ated

,lig

htgr

een

with

mid

-gre

encr

ysta

ls,V

iso

type

Gla

sgow

,G

lasg

owM

useu

ms

A19

64.2

9

2008

_016

4B

IEB

RIC

HW

iesb

aden

,H

esse

nB

Mus

_350

,B

Mus

_351

Jade

itite

,fin

e,pa

legr

een,

milk

y,w

hite

obliq

uefo

liatio

nL

ondo

n,B

ritis

hM

useu

m№

1979

.4-1

.1

2008

_032

3G

OL

IAN

OV

OK

LA

S_48

4,K

LA

S_48

5Ja

deiti

te,p

ale

gree

n,w

ithco

nvol

uted

stru

ctur

e,V

iso

type

,hea

vily

burn

tPr

ivat

ely

owne

d

End

mem

ber_

158

2008

_032

5A

BB

EV

ILL

ESo

mm

eM

oulin

Qui

ngno

n

AR

CH

_003

,A

RC

H_0

04,

AR

CH

_294

,A

RC

H_2

95

Jade

itite

,ver

yfi

ne,f

olia

ted,

Vis

oB

ulè

type

,so

me

dark

gree

nsp

eckl

esSa

int-

Ger

mai

n-en

-L

aye,

MA

N№

1898

3

2008

_066

3IL

EA

UX

MO

INE

SM

orbi

han

Poin

tedu

Bro

hel

(Ile

d’A

rz)

AR

CH

_022

,A

RC

H_0

23Ja

deiti

te,v

ery

fine

,whi

tein

clus

ions

,V

iso

type

Sain

t-G

erm

ain-

en-

Lay

e,M

AN

7337

6

2008

_143

7PO

ZZ

UO

LO

DE

LFR

IUL

IFr

iuli,

Ven

ezia

Giu

liaSa

mm

ar-

denc

hia

UD

IN_1

01,

UD

IN_1

02L

ight

gree

nfo

liate

dro

ckU

dine

,Mus

eoFr

iula

nodi

Stor

iaN

atur

ale

SAM

146,

mus

ée21

78

End

mem

ber_

162

2008

_002

7D

UN

FER

ML

INE

Fife

Pitr

eavi

eH

ouse

SCT

L_0

12,

SCT

L_0

13L

ight

gree

n,nu

mer

ous

crac

ks,b

recc

iate

d,V

iso

type

,mar

ked

patin

aE

dinb

urgh

,Nat

iona

lM

useu

ms

Scot

land

NM

SX

.AF

448

2008

_006

9ST

IRL

ING

Stir

ling

(ant

érie

ure-

men

tStir

lings

hire

)pr

èsde

Stir

ling

SCT

L_0

44,

SCT

L_0

45Ja

deiti

te,l

ight

grey

-gre

en,v

ery

sacc

haro

idal

Edi

nbur

gh,N

atio

nal

Mus

eum

sSc

otla

nd

NM

SX

.AF

1084

(anc

ien

NM

SX

.L.

1926

.11)

2008

_017

6B

RÜ

HL

Erf

t-K

reis

(Ber

ghei

m),

Nor

-dr

hein

-Wes

tfal

en

KL

AS_

009,

KL

AS_

010

Jade

itite

,gre

y-gr

een,

sacc

haro

idal

,V

iso

type

Bon

n,R

hein

isch

esL

ande

smus

eum

№30

234

2008

_030

3SI

ND

OR

F(K

erpe

n-Si

ndor

f)R

hein

-Erf

t-K

reis

Nor

drhe

in-W

estf

alen

Erf

taue

KL

AS_

211,

KL

AS_

212

Jade

itite

,pal

egr

een,

sacc

haro

idal

,V

iso

Porc

oty

peco

ll.pa

rt.K

och

2008

_030

7SO

DE

N(O

bern

burg

-So

den)

Kre

isM

ilten

berg

,B

ayer

nK

LA

S_20

4,K

LA

S_20

5

Jade

itite

,sac

char

oida

l,w

ithla

rge

light

gree

ncr

ysta

lsan

dse

vera

lmid

-gre

en,V

iso

Porc

oty

pe

Wür

zbur

g,M

ainf

ränk

isch

esM

u-se

umS

1529

2008

_038

8A

RZ

ON

Mor

biha

nT

umia

cV

AN

N_0

30,

VA

NN

_031

Jade

itite

,lig

htgr

een,

with

ast

ruct

ure

feat

urin

gla

rge

tran

sluc

entc

ryst

als

Van

nes,

Poly

mat

hiqu

e83

4

2008

_082

8PL

OE

ME

UR

Mor

biha

nK

erha

mC

arn_

017,

Car

n_01

8Ja

deiti

te,l

ight

gree

n,sa

ccha

roid

al,

seve

ralb

lack

spec

ks,V

iso

type

Car

nac,

Mus

éeR

82.6

0.11

2008

_104

0V

ILL

ER

OY

Yon

neB

ois

Car

taud

SEN

S_00

2,SE

NS_

005

Jade

itite

,gr

eyto

light

gree

n,sa

ccha

roid

al,

Vis

oPo

rco

type

Sens

,Mus

éedo

nE

.Baz

in,

SAS.

G.1

9

2008

_109

1G

RA

ND

SON

Vau

dC

orce

lette

sB

sPr_

196,

BsP

r_19

7

Jade

itite

,ve

ryco

arse

-gra

ined

,blu

ish

patc

hes

(gla

ucop

hane

)to

war

dsth

ebu

tt,si

mila

rto

Pont

invr

ea?

Lau

sann

e,M

usée

d’A

rché

olog

ieet

d’H

is-

toir

eIV

9796

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 250

from the Beigua massif, even though this does not constitute a definitive determinant in itself, unless complementaryarguments are used to buttress this evidence.42 However, this type of jadeitite, when viewed with the naked eye, pos-sesses all the characteristics of the jadeitites from Mont Viso, and in particular those of Oncino/upper Bulè.

Two diffuse reflectance spectroradiometric analyses were carried out;43 the reference numbers of the re-sultant spectra are KLAS_484 and KLAS_485 (Fig. 3, bottom). The absorption beween 432 nm and 436 nm indi-cates jadeite, even though that between 1915 nm and 1934 nm shows the presence of aqueous inclusions in thismineral and also in quartz and/or feldspar. The absorptions between 2000 nm and 2500 nm indicate a light retro-morphism, whose nature is hard to specify as the characteristics are not marked. Thus, we are dealing with a jadei-tite that is probably quartzo-feldspathic and lightly retromorphosed (Note 2).

Comparisons with the reference collection of Alpine raw material samples (Figs 3 and 4) indicate that themost likely origin for this spectrofacies (Spectrofacies_345) is the Mont Viso massif and more precisely, Oncino/Bulèand Porco, even though we cannot altogether exclude the possibility that the Beigua massif had been the sourcearea. Nevertheless, three pieces of evidence (namely the presence of rutile, macroscopic examination and spectro-radiometric analysis) all point in the same direction: an origin of the jadeitite in the quarries of the southern area ofMont Viso.

Other polished axeheads that have been analysed using spectroradiometry belong to the same spectrofacies(Figs 5 and 6). These include one axehead from Sammardenchia (JADE 2008_1437, SAM 146), which could havebeen contemporary with the Golianovo example. As for other polished axeheads, these all belong to different and latertypes, dating to the second half of the 5th millennium and the beginning of the 4th. Their distribution in Europe oftencoincides with the most remarkable geographical concentrations of Alpine axeheads (Fig. 1,Gulf of Morbihan, Scot-land, the Paris Basin, Germany), and chronologically these axeheads are not of the same date as that proposed for theGolianovo axehead (early Lengyel). However, we should keep the Golianovo-Sammardenchia coincidence in mind,because – as noted above and discussed further below – both these axeheads belong to the same period.

5. THE SECOND AXEHEAD FROM GOLIANOVO (INV. JADE 2008_324)

This is represented solely by the blade section, and comes from a large axehead (Fig. 7), of medium thick-ness, with a biconvex section. The length is 5.7 cm (originally 6.1 cm); the width, 6.6 cm; thickness: 1.9 cm. Veryregular, lustrous polish.

The rock is dark green and very clearly saccharoidal, with probable hollow-centred (atoll) garnets on theventral face – a distinctive feature of the jadeitites and omphacitites of the Viso massif.44

The initial analyses45 had showed that jadeitite was dominant, with violet amphiboles (barroisite), relict pla-gioclase, minerals from the epidote family, apatite and ilmenites bordered by sphene. This range of accessory mi-nerals seems fairly similar to that seen in raw material specimen LM 010 in the JADE reference set,46 from the highvalley of the Po, immediately below Mont Viso.

Two spectroradiometric analyses were undertaken (reference numbers KLAS_482 and KLAS_483: Fig. 8,bottom). The absorption around 436 nm, and that around 1900 nm, indicates an omphacititic jadeitite; the absorp-tions between 2000 nm and 2500 nm indicate that it has been lightly retromorphosed (Note 3). The specific gravityof the rock (3.29) is consistent with this lithological identification.

Taking the results of this spectroradiometric analysis on their own, and comparing the axehead spectra withthose from the reference set of raw material samples (Figs 8 and 9), one might conclude that Endmember_201 (towhich this second Golianovo axehead belongs) could equally well have come from the Beigua massif as from MontViso. However, the two Mont Beigua specimens in question (Fig. 9, from Olbicella and Sassello) consist of smalltablets of heavily fissured jadeitite, incapable of being used to produce polished axeheads. The value of the ma-croscopic comparison of the Golianovo axehead with the raw material reference samples is therefore demonstrated:

42 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.43 See ERRERA 2002; ERRERA et al. 2006; ERRERA et al.

2007; ERRERA et al. in print 2011 for details of this method.

44 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.45 HOVORKA et al. 200846 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.

251TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 251

the presence of the hollow-centred (atoll) garnets is a signature characteristic, which allows us to pinpoint the ori-gin of the second Golianovo axehead in the Mont Viso massif, and probably in the quarries of Bulè or Porco.

Fig. 7. Golianovo (Slovakia): blade of a large axehead with a biconvex section, omphacititic jadeitite. Spectroradiometric analysis:KLAS_482 and KLAS_483. Inventory N: JADE 2008_324. Photo: P. Pétrequin

252 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

Fig. 8. Comparison of the two spectra of Golianovo JADE 2008_324 with seven spectra from the JADE reference collection of Alpine rocks.While similarities exist with specimens both from Mont Viso and from Mont Beigua, the most plausible origin is the Viso massif,

in particular those from the Neolithic working areas at Oncino/Bulè and Porco. Document: M. Errera

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 252

The five other very large Alpine axeheads that belong to the same spectrofacies (Endmember_201) as thesecond Golianovo axehead (Figs 10 and 11) are distributed in a random fashion over western Europe, occurring invarious axehead types whose dates extend over the whole of the 5th and 4th millennia BC.

It thus appears that both of the Golianovo axeheads started their lives in the high-altitude quarries on MontViso, probably at Bulè or Porco where the abundance of good quality jadeitites is highest, by far, in the whole of the

Fig. 9. Comparison of the spectrum of Endmember 201 (to which the axehead Golianovo JADE 2008_324 belongs) with spectra from theJADE reference collection of Alpine rocks. An origin in the Viso massif is probable, if one takes into account certain macroscopic criteria.

Document: M. Errera

253TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

Endmember type Comparanda from theJADE reference database Provenance of the raw material samples

Endmember_201 ANNE_007, _008 Onci_137 0,905 Yes (but)Oncino; Point 99/4, Circle of Blocks,Shelter A, № 64. Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2007

Alpe_697 0,851 Yes (but)Paesana, torrent bed of Po.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 2002

Onci_027 0,874 Yes butOncino; Porco, trial trench Abri Jadéite, –17 cm.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 23/09/04

Alps_307 0,870 Yes butOlbicella; gorges of the Orba, under a viaduct.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 26/06/04

Alps_774 0,860 Yes butLM 240: Oncino, Bulè, Point 82.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 22/08/05

CBar_006 0,862 Yes butBobbio Pellice; Barant Nord, Point 9.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 09/09/08

Alps_163 0,849 Yes butSassello; downriver from theErro gorge near the ford of Mioglia.Collected by P. Pétrequin. 14/05/2004

Fig. 10. Comparison of the two spectra of Golianovo JADE 2008_324 with spectra from the database of large Alpine axeheads from Europe.Document M. Errera

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 253

AXEHEAD

№FINDSPOT

Preliminary

analysis

SPECTRUM

№ROCKTYPEbasedon

macroscopicexamination

MUSEUMorCOLLECTION

End

mem

ber_

201

2008

_151

AL

LE

RST

ED

T(W

olm

irst

edt-

Alle

rste

dt)

Ohr

ekre

is,

Sach

sen-

Anh

alt

jade

itite

KL

AS_

088

Mid

gree

nw

ithso

me

whi

tecr

ysta

ls,r

etro

mor

phos

edec

logi

t?

Hal

le,A

rchä

olog

isch

esL

ande

smus

eum

von

Sach

sen-

Anh

alt

63:5

32

2008

_324

GO

LIA

NO

VO

jade

itite

.Sp

ecif

icgr

avity

=3.

29

KL

AS_

482,

KL

AS_

483

Jade

itite

,dar

kgr

een,

very

sacc

haro

idal

,ver

ypr

obab

lyho

llow

garn

ets

onve

ntra

lfac

e,V

iso

Bul

èty

pe

Priv

atel

yow

ned

2008

_509

CA

RN

AC

Mor

biha

nSa

int-

Mic

hel

VA

NN

_063

,V

AN

N_0

64Ja

deiti

te,m

id-g

reen

with

dark

gree

nsp

ots

and

whi

tish

Van

nes,

Poly

mat

hiqu

e78

0

2008

_618

EV

RE

UX

Eur

eja

deiti

teB

sPr_

103

Jade

itite

,fol

iate

d,be

dsal

tern

atel

ylig

htgr

een

and

mid

-gre

enE

vreu

x,M

usée

1139

2008

_656

HA

UT

E-S

AV

OIE

(to

leve

lof

regi

onon

ly;c

o-or

dina

tes

take

nas

Ann

ecy)

Hau

te-

Savo

ieA

NN

E_0

07,

AN

NE

_008

Mid

-gre

en,l

ight

lysa

ccha

roid

al,

jade

itite

?A

nnec

y,M

usée

-Châ

teau

19.5

36

2008

_754

MO

NT

LA

UR

Aud

eL

esPi

cart

sja

deiti

teC

arc_

054,

Car

c_05

5

Jade

itite

,pal

egr

een,

fine

-gra

ined

,fol

iate

d,fa

intw

hitis

hpa

tche

s

Car

cass

onne

,ex

cava

tion

find

sst

ore

434

Fig.

11.C

ompa

riso

nof

the

spec

trum

ofE

ndm

embe

r20

1(t

ow

hich

the

axeh

ead

Gol

iano

voJA

DE

2008

_324

belo

ngs)

with

spec

tra

from

the

data

base

ofla

rge

Alp

ine

axeh

eads

from

Eur

ope.

Doc

umen

t:M

.Err

era

254 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 254

interior Alps.47 Furthermore, the roughouts of this type of axehead/adze head, with a pointed butt and curvilinearblade which merges progressively with the body, are very numerous on Viso (Fig. 12), with examples in jadeitite and(more commonly) in omphacitite and eclogite. It would appear, therefore, that the polished axe/adze heads from Go-lianovo could have resulted from the selection of artefacts – of jadeitite or of fine-grained omphacitite – for use in long-distance exchanges. This selection began at the quarries, where the finest jades were particularly highly prized.48

Fig. 12. In all probability the two axehead fragments from Golianovo belong to the Durrington type, whose roughouts in jade are abundantlyrepresented at the Neolithic working sites on Mont Viso, as at Oncino/Vallon des Milanais (top) or Vallon Bulè (bottom). Photo: P. Pétrequin

47 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011. 48 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.

255TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 255

Certain roughouts (or fragments) of this type of axe/adze head are not unknown among the quarries of the Bei-gua massif and in the production zone around that massif (as, for example, at Rivanazzano (Pavia, Lombardy49). Howe-ver, these roughouts are made from rocks of mediocre quality; the fine, translucent and luminous jadeitites are absent.

49 D’AMICO–STARNINI 2006.

256 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

Fig. 13. Chronological classification and evolution of Alpine jade axehead types, along the axis Mont Viso (Italy) – Gulf of Morbihan(Brittany, France). The Durrington type appeared from the end of the 6th millennium but as short, thin forms. Around the middle of the 5th mil-

lennium, this type underwent a marked development with the emergence of the perfectly symmetrical ‘teardrop-shaped’ variant.Drawing: P. Pétrequin

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 256

(This observation has been made by P. Pétrequin, on the basis of examining the collections of the Museo Civico diArcheo-logia Ligure in Genoa and the Museum of Casteggio). We can therefore perceive two different behaviours by the pro-ducers of flaked roughouts according to whether rocks came from theViso massif or from the Beigua massif, as follows:

– on the one hand, on Mont Viso, side by side with the production of small workaday tools, there was alsothe specialist production of larger items made from the finest jades; this would have taken place during seasonal vi-sits to this mountainous, hard-of-access area, far from permanent settlements. The quality and the symbolic powerof these latter roughouts, for objects that were longer than the everyday tools, made them very good candidates foruse in long-distance exchanges, by virtue of the high social value placed on them;

– on the other hand, in the Beigua massif, most of the roughouts resulted from the exploitation of secon-dary deposits, in torrent beds, at lower altitudes, in zones that were easily accessed, and which sometimes lay in thesame area as permanent settlements (for example in the region of Sassello). The rocks, of a lower quality than thosefrom Mont Viso, were used to make workaday tools, of low social value; and the distance travelled by these toolsin exchanges rarely exceeded 200 to 250 km as the crow flies from the source areas (Note 4).

6. TYPOLOGY AND DATE OF THE GOLIANOVO AXEHEADS

We are well aware that the attribution of the Golianovo axehead fragments to one or other of the types ofAlpine axeheads that have been defined by programme JADE is risky.50 However, to judge by their shape and trans-verse section (Figs 2 and 7), these two fragments can be accommodated comfortably within the Durrington type (Fig.13). This type, more or less in the shape of a drop of water (‘teardrop’, according to Campbell Smith’s English ty-pology51), is characterised by its squat proportions, with a pointed but and a lenticular or oval section that is moreor less flattened.

Chronologically, the Durrington type belongs to two periods, with subtle differences in form between the two.At the end of the 6th millennium and the very beginning of the 5th this axehead type is known in northern

Italy from several jadeitite examples, of which only two are from a well-dated context: one is from Lugo di Grez-zana (Verona, Venice), associated with a jadeitite disc-ring in a village of the Fiorano culture, with a single radio-carbon date around 5500–5300 cal BC;52 the other is from the eponymous settlement at Fiorano Modenese (Modena,Emilia Romagna), and was similarly associated with a jadeitite disc-ring;53 this is from a context dated to the period5600–4900 BC.54 In these two cases, as with the two Golianovo axeheads, the Durrington-type axeheads have asection that is not very thick. A little later, the Durrington type seems to disappear (or at least to become rare) du-ring the first half of the currency of the Square-Mouthed Pottery Culture, as seen in the cemetery of Chiozza at Scan-diano (Reggio Emilia, Emilia Romagna), where the Bégude type and its variants predominate.55 The same is true ofthe small cemeteries of this culture in the region of Parma in western Emilia.56

From the middle of the 5th millennium or slightly before that, the ‘teardrop’-shaped Durrington type ofaxehead – this time, with a thick section – underwent a remarkable development, in particular to the north-west ofthe Alps, in France, Germany and Great Britain. In hoards, it is often assoiated with axeheads of Altenstadt-Green-law type,57 of which the earliest example, in the mound of Mané er Hroëck à Locmariaquer (Morbihan)58 is no ear-lier than 4600 BC. Here, among other grave goods, the Durrington-type axeheads were associated with others ofBégude type and with a large jadeitite disc-ring.

In our opinion, in view of their archaeological context (dating to the earliest centuries of the 5th millennium:see above, paragraph 3), the Golianovo axeheads probably belong to the earliest version of the Durrington type,which developed in northern Italy during the second half of the 6th millennium and the beginning of the 5th in Early

50 PÉTREQUIN–CROUTSCH et al. 1998; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN

et al. 2002; PÉTREQUIN–SHERIDAN et al. 2008.51 CAMPBELL SMITH 1963.52 MOSER 2000; FERRARI et al. 2006.53 BAGOLINI–PEDROTTI 1998.54 FERRARI et al. 2006.

55 BAGOLINI–BARFIELD 1971.56 BERNABÒ BREA et al. 2006.57 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. 2009.58 HERBAUT 2000; PÉTREQUIN–SHERIDAN et al. 2008;

CASSEN et al. 2009; CASSEN et al. in print 2011.

257TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 257

Fig. 14. Distribution of large Alpine jade axeheads of Bégude type, partly contemporary with the Golianovo axeheads.At the end of the 6th millennium or at the beginning of the 5th these two axeheads found in Slovakia were created at the quarries onMont Viso and circulated via the Alpine cols, Lower Austria and the Danube valley. Alpine axeheads of other types are indicated by

white circles. CAD: J. Desmeulles, E. Gauthier and P. Pétrequin

59 PESSINA–D’AMICO 1999.60 See, inter alia, COCCHI GENICK 1994, II, fig. 17.

61 PESSINA 2000; PESSINA–TINÉ 2008.

258 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 258

Neolithic contexts: Vhò, Fiorano and Fagnigola (Sammardenchia phase). These contexts are linked by the use of Fio-rano-style pottery. Three burnt axeheads, of which at least two are of jadeitite from Viso, have been found at Poz-zuolo del Friuli/Sammardenchia, on the eponymous site, even though the association with the Fiorano style of potteryhas not been definitively demonstrated.59 Yet another example is known from old excavations at Palude Brabbia (Va-rese, Lombardy); this had probably been associated with a ring-disc of jadeitite.60

Fig. 15. During the 5th millennium, a jade Europe (whose epicentre lay in the Gulf of Morbihan) was opposed to a copper and gold Europe(with Varna as its epicentre). In this context, the two Alpine jade axeheads discovered at Golianovo represent importations in an early

Lengyel context, for a ceremonial and ritual use during the first half of the 5th millennium. CAD: E. Gauthier and J. Desmeulles ;documentation L. Klassen and P. Pétrequin

259TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 259

Thus it is in this context of the earliest Neolithic of northern Italy, preceding the earliest phase of the Square-Mouthed Pottery Culture,61 that one finds the Durrington-type axeheads with a narrow section that are typologicallyclosest to the two examples from Golianovo.

7. FROM MONT VISO TO GOLIANOVO

It would seem from the foregoing that the transfer of jade axeheads – albeit occasional and in small num-bers – from Mont Viso towards Golianovo is among the earliest, if not the earliest example of the movement of Al-pine axeheads yet identified in Europe (Note 4). The Golianovo axeheads, produced at the end of the 6th millenniumor at the very beginning of the 5th reached the Republic of Slovakia around the 49th–48th centuries BC. This shouldnot surprise since the existence of transalpine exchanges between Friuli and Austria have already been clearly de-monstrated through the presence of long, Danubian-tradition shoe-last adze heads at Sammardenchia during the pe-riod 5500–4700 BC62 and through certain Austrian stylistic influences on the decoration of Fiorano pottery (namely‘musical notes’ decoration63).

The north-easterly exchange of Alpine jade objects around 4800–4700 BC was followed by similar move-ments of axeheads of Bégude type64 (Fig. 14) as follows:

– At Villach/Kanzianberg (Austria), a hoard of large axeheads said to be of ‘serpentine’ could be contem-porary with the level containing Balkan- or Square-Mouthed Pottery Culture-style ‘pintaderas’ (stamps).65 This hoardis certainly not related to the late Square-Mouthed Pottery (of the Kanzianberg-Lasinja group) found on this site.66

– At Kamegg (Austria), a butt of a Bégude-type axehead of omphacitite from Mont Viso comes from aninternal ditch of a concentric enclosure.67 This monument belongs to the early Lengyel culture (Moravian PaintedWare Ia-b phase68) and the internal ditch is dated to 4700–4500 BC by two radiocarbon dates.69

Furthermore, at Friebritz-Süd (Austria), this time in a grave (tomb No. 138) that is particularly richly fur-nished (with five pots, two flint blades, two flint trapezes and a necklace of cylindrical spondylus shell beads), a smalladze head of Alpine rock – said to be of ‘serpentine’– was found. It is of a type that is classic in Italian Square-Mouth-ed Pottery Culture contexts.70 This cemetery is also attributed to the early Lengyel phase.

There is another possible example (which needs to be checked through inspection in the hand) of an axe-head of Bégude type in tomb 3060 in the cemetery at Alsónyék-Kanizsa in Hungary. This, too, was particularly rich.I. Zalai-Gaal71 dates it to Lengyel I, at the transition from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic.

One probably Alpine axehead found at Semerovce, near Krupina (Slovakia),72 is of particular interest, be-cause it is probably of Rarogne type (variant Krk). This constitutes one of the rare examples of where axeheads tra-velled from the Beigua massif towards Croatia (as in the example from Vrbnik, Krk Island73), and Bulgaria (tomb1 at Varna II74). In the oldest of the Carnac-type mounds in the Gulf of Morbihan in Brittany (Mané er Hroëck àLocmariaquer75), a Rarogne-type axehead is dated to the mid-5th millennium or a little before that. This type of jadeaxehead, with a slightly expanded blade, seems to have been influenced by the earliest copper axeheads that pro-bably appeared in north Italy during the first half of the 5th millennium.76

It is thus possible, if not probable, that further examples of these axeheads that demonstrate the movementof Alpine objects towards (or beyond) Hungary remain to be identified.

The exchanges along the axis Mont Viso–Golianovo are relatively well-dated. They would have begunaround 4900 BC, with a break (at least a break in the movement of Alpine jade axeheads) around 4500–4400 BC.This period of expansion (between 4900 and 4500 BC) is roughly the same as that proposed for the movement of

62 D’AMICO et al. 1997; FERRARI–PESSINA 1999; PESSINA–D’AMICO 1999.

63 BAGOLINI–PEDROTTI 1998.64 PÉTREQUIN–CROUTSCH et al. 1998; THIRAULT 1999.65 PEDROTTI 1990.66 RUTTKAY 1996.67 PŘICHYSTAL–TRNKA 2001; TRNKA 2005; PÉTREQUIN–ER-

RERA et al. in print.68 STADLER–RUTTKAY 2007.

69 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print.70 NEUGEBAUER-MARESCH et al. 2001.71 ZALAI-GAÁL 2008, Abb. 15 et 16.72 MITSCHA-MÄRHEIM–PITTIONI 1934.73 PETRIĆ 1995; PETRIĆ 2004.74 PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. in print 2011a.75 HERBAUT 2000; CASSEN et al. in print 2011.76 KLASSEN–CASSEN et al. in print 2011.77 Mapped in TODOROVA 2002 and elsewhere.

260 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 260

Bégude-type axeheads along the axis linking Mont Viso with the Gulf of Morbihan (Fig. 13); the chronological pa-rallelism is striking and relates to the main period of production on Mont Viso, when roughouts were simultaneouslymoving both to the north-west and to the north-east. However, while the movement towards north-west Europe re-ceived a new impetus around the middle of the 5th millennium and continued until the beginning of the 4th millen-nium, the movements towards the north-east, to Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovenia seem to have tailed offduring the second half of the 5th millennium.

This situation demands an explanation, especially since the circulation of Alpine jades involved a smallnumber of artefacts being used for ritual purposes (in the large enclosures – Golianovo, Kamegg), one being usedas an exceptional grave good in a rich grave (Friebritz) and some ended in the remarkable hoard of very long po-lished axeheads at Kanzianberg.

One might equally ask why the transfers of Alpine objects towards the north-east involved axe/adzeheadsof jades, while the ring-discs of jadeitite (or serpentinite) did not follow them. It may be that the ‘Danubian’ tradi-tion of using spondylus shell77 operated as a brake on the expansion of jade ring-discs, at a time when the quantityof spondylus in circulation was considerable in Lengyel contexts.78

8. THE EUROPE OF JADE AND THE EUROPE OF COPPER

Along with the two jadeitite axeheads from Golianovo, the first metal finds appear in the Lužianky groupof the Lengyel culture in Slovakia.79 These early metal artefacts are by no means rare: they appear in appreciablenumbers not only in the Lengyel culture in Slovakia, but also in neighbouring Lengyel groups80 and in neighbou-ring but differing cultural groups (Theiß, Herpály81). In fact, the number and distribution of metal objects shows aclear increase during the early 5th millennium BC when compared with earlier examples that had appeared duringthe early and middle Neolithic in more easterly and south-easterly parts of Europe, from the middle of the 6th mil-lennium onwards.82

Two observations pertaining to these metal finds are crucial for our understanding of the relationship bet-ween them (and early metallurgy in general) and the distribution of Alpine axes in Slovakia and other parts of south-east Europe. The first is the fact that, with the exception of awls, these numerous early metal objects are all itemsof personal adornment, be it jewellery (e.g. rings and beads) or dress accessories (pins). The second observation re-lates to the find contexts of these artefacts: they were discovered in comparatively large numbers in settlements andgraves. All the available data indicate that these early metal artefacts did not have any different meaning from thatof the other types of jewellery made from rare and exotic materials, such as spondylus shell. They were certainlyassigned a prestige value, but there are no indications that they had any special symbolic or ritual importance.

This situation changes with the appearance of the first massive, cast copper objects, especially differenttypes of shafthole axehead (hammer axeheads and somewhat later axe-adzes83). While there is no doubt that thesewere also assigned a prestige value, as is apparent from their regular appearance in richly furnished graves (e.g. inSlovakia in the Tiszapolgár-cemeteries of Tibava and Velke Raškovce84), their almost complete absence from sett-lement sites, as well as their frequent appearance in hoards and as stray finds, possibly representing single deposi-tions at special sites in the landscape, clearly suggests that these metal artefacts had a strong ritual connotation.

The map shown in Fig. 15 offers a graphic representation of Pétrequin’s fundamental observation that, du-ring large parts of the 5th and at the beginning of the 4th millennium BC Europe was divided in two halves.85 In thewestern half, large axeheads of Alpine jade acted as objects of power and were the subject of strong ritual beliefs.86

In the eastern part of the map, the same function was fulfilled by heavy shafthole tools of copper and by various typesof gold artefact. Consequently, the distributions of the two groups of artefacts are generally mutually exclusive.

78 KALICZ–SZENASZKY 2001.79 NOVOTNÁ 1995a; NOVOTNÁ 1995b; PERNICKA 1995.80 E.g. ZALAI-GAÁL 1996.81 HORVÁTH 1990, 51, Abb. 54; KALICZ–RACKY 1990, 134,

Abb. 205.82 HOREDT 1976; KUNA 1981; KALICZ 1992.

83 DRIEHAUS 1952; SCHUBERT 1965.84 ŠIŠKA 1964; VIZDAL 1977.85 PÉTREQUIN–JEUNESSE 1995, 120; PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et

al. 2002; described in detail in KLASSEN–CASSEN et al. in print 2011.86 PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. 2009.87 TOČIK–BUBLOVÁ 1985; TOČIK–ŽEBRÁK 1989.

261TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 261

The two fragments of Alpine axeheads from Golianovo apparently constitute an exception, as they werefound within the distribution area of heavy shafthole tools and are thus far outside the closed distribution area of theAlpine jade axeheads. The explanation for this has to be sought in the early date of the Golianovo axeheads as com-pared to the comparatively late date for the onset of the production and distribution of heavy shafthole copper toolsin Slovakia. While the Golianovo finds have to be dated to the early 5th millennium BC, the heavy shafthole coppertools in this area cannot presently be dated any earlier than the second half of the 5th millennium BC. This is alsotrue for the aforementioned gold finds from Tiszapolgár contexts, and for the onset of copper mining at the westernSlovakian site of Špania-Dolina Piesky.87 The mining activity here probably started in Brodzany-Nitra times and wasthus roughly contemporary with the Tiszapolgár Culture. The metal produced at this and possibly other sites in theSlovakian Ore Mountains is characterised by two different distinctive trace element compositions and has been iden-tified in locally produced heavy shafthole tools from the beginning of the 4th millennium onwards.88

It therefore appears that the Golianovo axes were imported into Slovakia before metal-related ritual beliefsemerged in this area. The same must be true of the other Alpine axeheads, discussed above, that had previously beenidentified from Moravia, Austria and probably Hungary: all of these must pre-date the time of the heavy shaftholecopper tools and gold artefacts in these regions.

The only exception within the geographical area of interest here may be the axehead from Semerovce (seeabove), which is considerably later than the finds from Golianovo. As is apparent from the splayed blade ends of thisexample, this special type owes its existence to the incorporation of metal- related ideas that probably originated inthe Balkans, where the production of heavy copper tools in the late Vinča culture must date back to c 4750 BC.89

Thus, the importation of this kind of object probably did not conflict with the metal-related ritual beliefs that pre-dominated over large parts of south-eastern Europe.

The comparatively abundant finds of axeheads of alpine jade in Bulgaria90 are either of metal-related types(as in the case of the Rarogne-type axehead from Varna II, grave 1), or were heavily re-shaped and given a rectan-gular cross-section – another metal-related trait. Several finds from the large hoard from Svoboda even show tracesof having been rubbed with gold. This action may well relate to the conversion of the imported western Europeantypes, with their distinct jade-related ritual connotation, into south-east European types with a symbolic meaning thataccorded with the metal-related ideas that dominated this part of Europe at that time.

It may well be that re-shaped alpine axeheads were also present in Slovakia and other non-Bulgarian partsof south-east Europe during the second half of the 5th and the early 4th millennium BC. These finds are hard to iden-tify from the literature, as they are often rather small and do not have distinctive shapes. While some types of alpinejade are of a rather spectacular, partly translucent green colour and can be identified from this trait alone, others areless distinctively coloured, and range from a duller green to almost black. Re-shaped axeheads of these types ofrock can therefore only be identified by specialists studying the axeheads in their respective museums.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was undertaken as part of Projet JADE (Agence Nationale de la Recherche 2007–2010): « In-égalités sociales et espace européen au Néolithique: la circulation des grandes haches en jades alpins », administe-red by la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme et de l’Environnement, Besançon.

NOTES

Note (1): This work has been undertaken through the IGCP/UNESCO project, “Raw materials of the Neo-lithic stone implements on the Old Continent” (1999–2002), under the direction of one of us (D. Hovorka)

88 SCHUBERT 1982.89 ŠLJIVAR et al. 2006; BORIĆ 2009.

90 PÉTREQUIN–CASSEN et al. in print 2011a.91 HOVORKA et al. 2008.

262 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 262

Note (2): HOVORKA et al.91 have published the results of fairly detailed analyses carried out on this axehead,using petrological thin-sectioning, SEM microprobe analysis and X-ray diffraction spectrometry. The principal cha-racteristic is the presence of zonal Na-clinopyroxenes (jadeite/omphacite), in which the jadeite seems to be con-centrated in the heart of the crystals, indicating that the jadeite is older than the omphacite. HOVORKA et al. alsonoted the presence of rutile, frequently bordered by ilmenite, and of sphene. Albite, mica and one epidote werenoted principally as pseudomorphs of plagioclase. No quartz is present. The rock, completely recrystallised, had the-refore been formed in a phase of high pressure, followed by a phase of re-equilibration in a blueschist facies. Thisinterpretation accords with the results of the spectroradiometric analysis (jadeitite, probably quartzo-feldspathic,lightly retromorphosed). However, one should note that the presence of omphacitite can be overlooked during spect-roradiometric analysis because its spectrum overlies that of jadeite. The diffractometry results presented byHOVORKA et al.92 do not show any omphacite; spectroradiometry has not hitherto been able to distinguish clearlybetween quartz and feldspars (including albite). Retromorphosed minerals (amphiboles, chlorites and epidotes)cannot be identified when retromorphosis has not been very important.

However, there is a problem regarding the chronology of the appearance of Na-clinopyroxenes. The presenceof an aqueous phase, which is necessary for the formation of jadeite (as marked by the presence of inclusions) butwhich is absent from omphacite (which forms in the eclogite facies) indicates, in our opinion, that jadeite recrystal-lised from omphacite, and not vice versa. This is an important point and it needs to be resolved by petrologists.

The aforementioned analyses are in accord with those undertaken on comparative raw material specimensfrom the Alps, even though the zonal character of the material was not observed in these specimens, and that quartzis present93.

Note (3): HOVORKA et al.94 have published the results of fairly detailed analyses carried out on a fragmentof the blade, using petrological thin-sectioning, SEM microprobe analysis and X-ray diffraction spectrometry. Theprincipal characteristic is the presence of Na-clinopyroxenes in which omphacite seems to have invaded the core ofthe jadeite, indicating that the jadeite is older than the omphacite. The authors noted the presence of rutile, fre-quently bordered by ilmenite, and above all various generations of amphiboles and of plagioclases, most commonlyaltered by minerals of the epidote group; a dark mica and apatite are present. Quartz was not noted. The rock hadbeen affected by metamorphic processes of an intermediate gradient.

This interpretation accords fairly well with the results of spectroradiometric analysis (omphacititic jadei-tite, lightly retromorphosed); the retromorphic minerals (amphiboles, chlorites, epidotes) cannot be identified whenretromorphosis has not been very important. However, a problem remains with the chronology of the appearance ofthe Na-clinopyroxenes. (See Note 2 above.)

The aforementioned analyses are in accord with those undertaken on comparative raw material specimensfrom the Alps, in particular as regards the possible presence of jadeititic nuclei (sample LM 240 of the JADE refe-rence collection95).

Note (4): This excludes the later episodes of production on Beigua East, whose products reached Bulgaria.

Note (5): However, the date when small axeheads of Alpine jades began to circulate towards southern Italyis still very poorly known; it could as easily lie at the end of the 6th millennium BC, to judge from the southern dis-tribution of jadeitite ring-discs in peninsular Italy and as far south as Sardinia.96

92 HOVORKA et al. 2008, fig. 5, axe A.93 See in particular sample LM 145 and its corresponding

diffractogram: PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.94 HOVORKA et al. 2008.

95 PÉTREQUIN–ERRERA et al. in print 2011.

263TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 263

REFERENCES

BAGOLINI–BARFIELD 1971 = B. BAGOLINI–L. H. BARFIELD: Il neolitico di Chiozza di Scandiano nell’ambito delle culture padane.Rendiconti. Edizioni della Società di Culture Preistorica Tridentina 6 (1971) 107–178.

BAGOLINI–PEDROTTI 1998 = B. BAGOLINI–A. L. PEDROTTI: L’Italie septentrionale. In: Atlas du Néolithique européen, volume 2A: l’Europe occidentale. ERAUL 46. Liège 1998, 233–341.

BÁNESZ–NEVIZÁNSKY 1993 = L. BÁNESZ–G. NEVIZÁNSKY: Sídlisko lengyelskej kultúry v Golianove. AVANS 1993, 23–24.BERNABÒ BREA et al. 2006 = M. BERNABÒ BREA–L. SALVADEI–M. MAFFI–P. MAZZIERI–A. MUTTI–M. SANDIAS: Le necropoli dei

Vasi a Bocca Quadrata dell’Emilia occidentale: rapporti con gli abitati, rituali, corredi, dati antro-pologici. In: A. Pessina–P. Visentini (ed.): Preistoria dell’Italia settentrionale. Studi in riccordo di Ber-nardino Bagolini. Atti del Convegno, Udine, settembre 2005. Edizioni del Museo Friulano di StoriaNaturale, Udine 2006, 169–185.

BORIČ 2009 = D. BORIČ: Absolute dating of metallurgival innovations in the Vinca culture of the Balkans. In: T. L.KIENLIN–B. W. ROBERTS (eds): Metals and Societies. Studies in honour of Barbara S. Ottaway. Ver-lag Dr Rudolf Habelt, Bonn 2009, 191–245.

BŘEZINOVÁ et al. 2002 = G. BREZINOVÁ–J. HUNKA–L. ILLÁŠOVÁ: Archeologicky prieskum v Golianove. ŠtZ 34 (2002) 91–104.CAMPBELL–SMITH 1963 = W. CAMPBELL SMITH: Jade axes from sites in the British Isles. PPS 29 (1963) 133–172.CASSEN 2003 = S. CASSEN: Importer, Imiter, Inspirer? Objets-signes centre-européens dans le Néolithique armori-

cain. L’Anthropologie 107 (2003) 255–270.CASSEN et al. 2009 = S. CASSEN–P. LANOS–P. DUFRESNE–C. OBERLIN–E. DELQUE-KOLIC–M. LE GOFFIC: Datations sur le site

(Table des Marchands, alignement du Grand Menhir, Er Grah) et modélisation chronologique duNéolithique morbihannais. In: S. Cassen (ed.): Autour de la Table. Explorations archéologiques etdiscours savants sur des architectures néolithiques à Locmariaquer, Morbihan. Laboratoire de re-cherches archéologiques, CNRS et Université de Nantes. Nantes 2009, 737–768.

CASSEN et al. in print 2011 = S. CASSEN–C. BOUJOT–S. DOMINGUEZ BELLA–M. GUIAVARC–H-C. LE PENNEC–M. P. PRIETO MAR-TINEZ–G. QUERRE–M. E. SANTROT–E. VIGIER: Dépôts bretons, tumulus carnacéens et circulations àlongue distance. In: P. PÉTREQUIN–S. CASSEN–M. ERRERA–L. KLASSEN–A. SHERIDAN (ed.): Jade.Grandes haches alpines du Néolithique européen. Ve et IVe millénaires av. J.-C. Cahiers de la MSHEC.N. Ledoux. Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté, Besançon, in print.

COCCHI GENICK 1994 = D. COCCHI GENICK: Manuale di Preistoria II: Neolitico. Octavo Ed., Firenze 1994.COMPAGNONI et al. 1995 = R. COMPAGNONI–M. RICQ–DE BOUARD–R. GIUSTETTO–F. COLOMBO: Eclogite and Na-pyroxenite

stone axes of southwestern Europe: a preliminary petrologic survey. Bollettino Museo Regionale diScienze Naturali Torino, supplemento al vol. 13/2 (1995) 329–359.

D’AMICO et al. 1995 = C. D’AMICO–R. CAMPANA–G. FELICE–M. GHEDINI: Eclogites and jades as prehistoric implements inEurope. A case study. European Journal of Mineralogy 7/1 (1995) 29–41.

D’AMICO et al. 1997 = C. D’AMICO-G. FELICE–G. GASPAROTTO–M. GHEDINI–M. C. NANNETTI–P. TRENTINI: La pietra levigataneolitica di Sammardenchia (Friuli). Catalogo petrografico. Miner. Petrogr. Acta 40 (1997) 385–426.

D’AMICO–STARNINI 2006 = C. D’AMICO–E. STARNINI: L’atelier di Rivanazzano (PV): un’ associazione litologica insolita nelquadro della “pietra verde” levigata in Italia. In: A. Pessina–P. Visentini (eds): Preistoria dell’Italiasettentrionale. Studi in riccordo di Bernardino Bagolini. Atti del Convegno, Udine, settembre 2005.Edizioni del Museo Friulano di Storia Naturale, Udine 2006, 37–54.

D’AMICO et al. 2003 = C. D’AMICO–E. STARNINI–G. GASPAROTTO–M. GHEDINI: HP metaophiolites (eclogites, jades and oth-ers) in neolithic polished stone in Italy and Europe. Periodico di Mineralogia 73 (2003) 17–42.

DAMOUR 1863 = A. DAMOUR: Notice et analyse sur le jade vert. Réunion de cette matière minérale à la famille deswernérites. Comptes Rendus hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences (1863)861–865.

DAMOUR 1865 = A. DAMOUR: Sur la composition des haches en pierre trouvées dans les monuments celtiques et chezles sauvages. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences LXI. Séances du 21 et 28 août (1865)1–13.

DAMOUR 1881 = A. DAMOUR: Nouvelles analyses sur la jadéite et sur quelques roches sodifères. Bulletin de la SociétéFrançaise de Minéralogie 4 (1881) 157–164.

DRIEHAUS 1952 = J. DRIEHAUS: Zur Datierung und Herkunft donauländischer Axttypen der frühen Kupferzeit. AGeo2 (1952) 1–8.

ERRERA 2002 = M. ERRERA: Déterminations spectroradiométriques de cinq lames polies déposées au Musée du Cin-quantenaire à Bruxelles. Notae Praehistoricae 19 (2002) 131–140.

ERRERA 2004 = M. ERRERA: Découverte du premier gisement de jade-jadéite dans les Alpes (été 2004). Implica-tions concernant plusieurs lames de hache néolithiques trouvées en Belgique et dans les régions li-mitrophes. Notae Praehistoricae 24 (2004) 191–202.

ERRERA et al. 2006 = M. ERRERA–A. HAUZEUR–P. PÉTREQUIN–T. TSONEV: Etude spectroradiométrique d’une lame de hachetrouvée dans le district de Chirpan (Bulgarie). Interdisciplinary Studies 19. Archaeological Instituteand Museum, Sofia 2006, 7–24.

264 P. PÉTREQUIN et al.

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

AArch_02_2011_imp-utan:ActaArch_2011_2_tord 11/18/11 3:16 PM Page 264

265TWO AXEHEADS OF ALPINE JADE

Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 62, 2011

ERRERA et al. 2007 = M. ERRERA–P. PÉTREQUIN–A. M. PÉTREQUIN–S. CASSEN–C. CROUTSCH: Contribution de la spectro-radiométrie à la compréhension des transferts longue-distance des lames de hache au Néolithique.Société Tournaisienne de Géologie, Préhistoire et Archéologie 10/4 (2007) 101–142.

ERRERA et al. in print 2011 = M. ERRERA–P. PÉTREQUIN–A. M. PÉTREQUIN: Spectroradiométrie, référentiel naturel et étude de ladiffusion des haches alpines. In: P. Pétrequin–S. Cassen–M. Errera–L. Klassen–A. Sheridan (ed.):Jade. Grandes haches alpines du Néolithique européen. Ve et IVe millénaires av. J.-C. Cahiers de laMSHE C.N. Ledoux. Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté, Besançon, in print.

FERRARI et al. 2006 = A. FERRARI–P. MAZZIERI–G. STEFFE: La fine della culture di Fiorano e le primi attestazioni della cul-tura dei Vasi a Bocca Quadrata: il caso del Pescale (Prignano sulla Secchia, Modena). In: A. Pessina–P. Visentini (ed.): Preistoria dell’Italia settentrionale. Studi in ricordo di Bernardino Bagolini. Edi-zioni del Museo Friulano di Storia Naturale, Udine 2006, 103–128.

FERRARI–PESSINA 1999 = A. FERRARI–A. PESSINA (ed.): Sammardenchia – Cueis. Contributi per la conoscenza di una comu-nità del primo neolitico. Edizioni del Museo Friulano di Storia, Udine 1999.

FRANCHI 1900 = S. FRANCHI: Sopra alcuni giacimenti di roccie giadeitiche nelle Alpi occidentali e nell’Appennino li-gure. Bollettino del R. Comitato Geologico d’Italia 4/1–2 (1900) 119–158.

FRANCHI 1904 = S. FRANCHI: I giacimenti alpini ed appenninici di roccie giadeitiche. In: Atti del Congresso Interna-zionale di Scienze Storiche, Roma 1903, V (IV). Archeologia, Accademia dei Lincei. Roma 1904,357–371.

GIUSTETTO–COMPAGNONI 2004 = R. GIUSTETTO–R. COMPAGNONI: Studio archeometrico dei manufatti in pietra levigata del Piemontesud-orientale: valli Curone, Grue e Ossona. In: M. Venturino Gambari (ed.): Alla conquista del-l’Appennino. Omega Edizioni, Torino 2004, 45–59.

GODELIER 2006 = M. GODELIER: L’énigme du don. Fayard ed., Paris 2006.HERBAUT 2000 = F. HERBAUT: Les haches carnacéennes. In: S. Cassen (ed.): Eléments d’architecture. Exploration

d’un tertre funéraire à Lannec er Gadouer (Erdeven, Morbihan). Mémoire 19. Association des Pub-lications Chauvinoises, Chauvigny 2000, 387–395.

HOREDT 1976 = K. HOREDT: Die ältesten Kupferfunde Rumäniens. JMV 60 (1976) 175–181.HORVÁTH 1990 = F. HORVÁTH: Hódmezôvásárhely-Gorzsa. Eine Siedlung der Theiß-Kultur. In: W. Meir-Arendt

(Hrsg.): Alltag und Religion. Jungsteinzeit in Ost-Ungarn. Frankfurt 1990, 35–51.HOVORKA et al. 1998 = D. HOVORKA–Z. FARKAS–J. SPIŠIAK: Neolithic jadeitite axe from Sobotište (Western Slovakia). Geo-

logica Carpathica 49/4 (1998) 301–304.HOVORKA et al. 2008 = D. HOVORKA–J. SPIŠIAK–T. MIKUŠ: Aeneolithic jadeitite axes from Western Slovakia. AKorr 38

(2008) 33–44.JEUNESSE et al. 2003 = C. JEUNESSE–P. LEFRANC–A. DENAIRE: Groupe de Bischeim, origine du Michelsberg, genèse du

groupe d’Entzheim. La transition entre le Néolithique moyen et le Néolithique récent dans les ré-gions rhénanes. Cahiers de l’Association pour la Promotion de la Recherche Archéologique en Al-sace. 18–19. Zimmersheim 2003.

KALICZ 1992 = N. KALICZ: A Legkorábbi fémleletek Délkelet-Európában és a Kárpát-medencében az i. e. 6–5. évez-redben (The oldest metal finds in southeastern Europe and the Carpathian Basin from the 6th to the5th millennium BC). ArchÉrt 119 (1992) 3–14.