Perfectly True, Perfectly False: Cardsharps and Fortune Tellers by Caravaggio and La Tour

Transcript of Perfectly True, Perfectly False: Cardsharps and Fortune Tellers by Caravaggio and La Tour

Gail Feigenbaum, “Perfectly True, Perfectly False: Cardsharps and Fortune Tellers by Caravaggio and La Tour,” in Caravaggio: Reflections and Refractions, ed. Lorenzo Pericolo and David M. Stone (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 253–71.

12

Perfectly True, Perfectly False: Cardsharps and Fortune Tellers by Caravaggio and La Tour

Gail Feigenbaum

Cardsharps and gypsy fortune tellers are among Caravaggio's most famous subjects, and for his followers all over Europe, these subjects became a badge of affiliation with the master. Today their appeal and popularity may seem so obvious as to require no explanation-the actors are attractive, the scenes are gently funny, and as in theater, the spectator enjoys being let in on the joke. No doubt these paintings worked their charm on their original owners for the same reasons. Their very charm, however, makes it easy to forget that these were not somehow natural or conventional subjects for painting. Caravaggio invented them. Iconographic precedents for them that have been adduced by scholars, myself included, serve mainly to demonstrate just how new Caravaggio's compositions were. Tracing the literary sources reveals how painters transformed them by selecting and emphasizing quite different aspects of the subject than writers did. The aim of this chapter is to analyze how Caravaggio exploited the obvious appeal of these subjects in order to thematize critical aspects of the role of the painter and his viewer.

The painter of such subjects plays the role of "the fiend that lies like truth," to quote a line from Shakespeare written at the time Caravaggio was painting in Rome. 1 This conceit is embedded in the early literature on realism in painting and not least in Bellori's descriptions of Caravaggio's paintings such as The Cardsharps, wherein words like "fraudolente," "falsa," "£into" reinforce the notion of a representation that purports to stand in for reality but which can only be, in its very substance, a counterfeit.2 Gaspare Murtola's madrigal of 1603 about Caravaggio's Fortune Teller develops the same premise, rhyming "fingi" and "dipingi" to warn the listener that true appearances deceive and false appears as if true, while tricking and being tricked, cheating and being cheated, flip quickly back and forth from praise to blame.3

The metier of the painter who practises or, it can be argued in the case of Caravaggio, invents the new naturalism is deception, which is also the

254 CARAVAGGIO

metier of card cheats and gypsy fortune tellers. If the painter deceives, what then is the role of the one who is willing to pay for the pleasure of being tricked-the man (much less likely a woman) who buys the painting? The argument presented here is that the complicity between the cheat and his willing victim is at the heart of the matter. For in the case of a painter who, in Bellori's words, "tradusse si puramente il vero," collusion between the cheat and his willing victim signifies the complicity between the painter who makes a picture that purports to be a tranche de vie, but which by its very nature can only be false, and the spectator who is disposed to accept this image as true. 4 To identify the operation of this conceit is to bring into focus the active circuit of reception of such pictures, thereby offering an insight into the creation of the demand or market for paintings by the Caravaggisti, which represent an act of being tricked and by which a spectator consciously and eagerly submits to being tricked. Display of such a painting of inganno ignites a performance of sophisticated viewing. It is a performance that accentuates the advanced taste of a collector whose appreciation for the new realism is gently teased by his being "taken in" by the painter's illusionism. Lurking in the background is the frisson of anxiety that such an eager collector might even have risked paying a rather too high price for a canvas, betting on the success of an untested painter of a novel, low-genre subject of a man being cheated. And there can be no doubt that collectors of such paintings would have understood fully the play and con of any game, as their own gambling habits were more likely than not to skirt the stern admonitions of civil and curial authority.

Not every artist who took up these subjects in Caravaggio's wake would follow him in this regard by holding up a mirror to the circuitry of production and reception of low subjects treated in a naturalistic manner and painted in high style. But one painter who took the self-conscious embodiment of deception and complicity themes even further than Caravaggio was Georges de La Tour. Three paintings by Caravaggio and their three counterparts by La Tour are the focus here: Caravaggio's famous The Cardsharps in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (Fig. 12.1) and his two versions of the Fortune Teller in the Capitoline Museum, Rome (Fig. 12.2) and the Louvre, Paris (Fig. 12.3); La Tour's twin Cheat with the Ace of Clubs in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (Fig. 12.4) and Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds in the Louvre, Paris (Fig. 12.5), and his Fortune Teller in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (Fig. 12.6). Much has been written about these pictures, including this writer's extensive analysis of the subjects and their transformations by the Caravaggisti.5 Here the focus is instead on the activation of the metaphor of trickery as it informs the roles of the painter, the painting, the collector, and the viewer of such pictures.

Caravaggio had come to Rome from his native Lombardy and was still a struggling young artist when, around 1596, Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte bought The Cardsharps, probably from the rigattiere Costantino Spata who kept a shop across the street from the cardinal's palace.6 This was

.g te is D,

te

=r

se JY ty

21, 1at Jn irt

Jd on ed of ;es rts he he re,

:he m, ng by lOr or,

till ria 1no I' as

Gail Feigenbaum 255

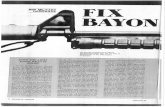

Caravaggio's big break, as the forward-thinking cardinal was so taken with the picture that he took the artist into his household and became his patron and protector.7 The Cardsharps depicts two young men playing cards-almost certainly the very popular game primiera, an ancestor of poker (Fig. 12.1).8 One of them, a sweet-faced adolescent dressed in expensive finery-burgundy velvet and dainty lace trim at the wrist and collar-is an easy mark. His opponent, a bravo donning bright livery, leans forward, watching with his arm braced on the table, his body tense and at the ready. In this instant of suspense, the cheat is waiting for the mustachioed rogue, who peers histrionically over at the boy's hand, to signal which card to draw from the ones concealed behind him in his britches. At the same time, the histrionic trickster signals to his accomplice within the scene: he also includes the knowing viewer, who would have recognized that his gloves have been deliberately slit to allow his trained fingertips to feel the raised pinpricks of marked cards.9 The game is played in a bare interior that is usually identified as a tavern or asteria, so the splendid Ushak carpet introduces a conspicuous marker of luxury that is out of place in such a setting. 10

Cardinal Del Monte most likely acquired Caravaggio' s Fortune Teller, now in the Capitoline (Fig. 12.2), at about the same time as The Cardsharps. They share a similar minimal setting and life-sized figures shown between half- and three-quarter length. In The Fortune Teller, a handsome youth

12.1 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 128.2 em.

(Photo: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas I Art Resource, NY)

12.2 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Fortune Teller, Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome, oil on canvas, 115 x 150 em.

(Photo: Scala I Art Resource)

256 CARA V AGGIO

entrusts his hand to a pretty gypsy who tells his fortune at the same time as she stealthily eases the ring off his finger. The Cardsharps and The Fortune Teller had similar dimensions and black frames in Del Monte's posthumous inventory, and scholars once assumed they were pendants. But the inventory rounds measurements to the nearest palma, and most of Del Monte's pictures were in black frames. In fact, the dimensions and proportions of the actual paintings differ enough that it is unlikely that Caravaggio conceived them as pendants. Rather it was Del Monte's display of them that made them so, as he at some point installed them near one another in one of the smaller gallerie in his vigna. Their novel style, roughly similar size and shape, and shared themes of deception brought them into a companionable association that impressed itself on artists and visitorsY Whether conceived by artist or collector, the iconographic coupling was fateful, as the Caravaggisti seized upon the subjects with relish, at times even splicing them into a single composition. When La Tour later painted his card cheats and fortune tellers in similar formats, scholars similarly speculated that they had been conceived as pendants. But again, there is no evidence that this was the painter's intentionY Caravaggio' s other Fortune Teller in the Louvre (Fig. 12.3) is usually dated slightly later than the Capitoline version. While the two paintings are quite similar, the

te 1e 's s. st .d at ty le

ly to II

as

!d ly re er m 1e

Gail Feigenbaum 257

models, poses, and some details of costume are different. No ring is visible now, and we do not know whether it has been rubbed off or was never there.

Like Caravaggio's cardsharps, La Tour's swindlers in Cheat with the Ace of Clubs (Fig. 12.4) and Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds (Fig. 12.5) dominate their bare setting, but instead of Caravaggio's signature raking light, La Tour closed the stage with a dark backdrop, adding an ambiguous hint of dimension with a lighter strip at the right, suggesting a corner. Four figures gather around a plain, narrow table. A youth studying his cards is ripe for the plucking, ostentatiously embroidered, plumed, and beribboned. His pile of coins glitters for all to see in contrast to that of the cheat who conceals his in shadow under his elbow. The presence of these coins is a reminder that there are no coins on the table in The Cardsharps. Presiding over the table is a courtesan dressed in a rich brown velvet dress trimmed in gold and cut low to expose an ample expanse of flawless skin. Her yellow-brown hair, smoothed flat to her skull, frames her perfect oval face. Her necklace is of pearls, which were purported to increase the skill of the wearer. She controls the action with her eyes, her shifty glance signaling the maid to divert attention by pouring the wine and alerting the cheat that it is time to make his move. The cheat sneaks a glance over his shoulder as

12.3 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Fortune Teller, Musee du Louvre, Paris, oil on canvas, 99 x 131 em.

(Photo: RMN-Grand Palais I Art Resource, NY)

12.4 Georges de La Tour, Cheat with the Ace of Clubs, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, oil on canvas, 97.8 x 156.2 em.

(Photo: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas I Art Resource, NY)

12.5 Georges de La Tour, Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds, Musee du Louvre, Paris, oil on canvas, 106 x 146 em.

(Photo: RMN-Grand Palais I Art Resource, NY)

Gail Feigenbaum 259

he slides an ace from his sash and tips his hand to the viewer. La Tour's wit is displayed not only in the biting characterizations of the figures, but also in the well-rehearsed and practised coordination of the maneuvers of this little band of con artists. Their conspiracy is so obvious to the spectator, while not a whiff of suspicion clouds the face of the dupe.

Like Caravaggio's two versions of The Fortune Teller, La Tour's two versions of the Cheats may appear almost identical at first sight, but compared side by side, they show themselves to be deliberate variations on a theme. No consensus has been reached regarding precedence, as the technical and stylistic evidence is both strong and confusing.13 Auxiliary cartoons were probably used to transfer the individual figures onto the canvas, and the spacing amongst the figures differs between the two versions. Costume details of color, pattern, and jewelry differ, as do such features as the ribbons of the cheat's sleeves, which are tied in bows in one painting and dangle loose in the other. Other subtle changes make a more marked effect, such as the ripe, ovoid perfection of the Kimbell's courtesan's face, cheeks blushed with pink. In the Louvre picture, her face is almost imperceptibly narrowed and given a yellow cast so she looks harder, shrewder, and more practised. Her necklace is shifted off to one side and she, too, seems crooked. Likewise, the cheat in the Louvre picture is more harshly characterized and, though clean-shaven in contrast to his counterpart, he is cast wholly into shadow. Most striking is the difference in the portrayal of the victim. While his costume is ostentatiously flamboyant in both versions, the Kimbell version with the shiny pink sleeves and long embroidered tunic is far more excessive. A hint of a pleased smile plays about the boy's lips in the Kimbell picture. In the Louvre version, his isolation is accentuated, as he is not only pushed further away from the cheating company, but is fully absorbed in the game in a way that closes off access to his inner life. The two pictures are quite different in handling. The Kimbell painting is executed with broad rapid brushwork that registers moving highlights on surfaces. The Louvre painting is comparatively austere in its effect, more meticulously built up and attentive to details of drawing and texture.

Tantalizing references to paintings of such subjects by La Tour appear in inventories of eminent French collectors but, knowing nothing about the original destination or commission of either of his surviving Cheats, one can only speculate on the artist's motives for changing the temperament of the two paintings while insisting on a relationship both of pronounced resemblance and subtle differentiation: for instance, a Parisian client with a taste for Simon Vouet's brighter palette might have preferred a rather less sober picture than his counterpart in Lorraine.

La Tour's Fortune Teller (Fig. 12.6) is blonder in tonality than the paintings of card cheats, with an illuminated background as in Caravaggio's. Five actors line up overlapping in a frieze upon a shallow stage. Planted a little stiffly, a fine-looking youth holds the center of the composition with his

12.6 Georges de La Tour, Fortune Teller, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, oil on canvas, 101.9 x 123.5 em.

(Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art I Art Resource, NY)

260 CARA V AGGIO

bright red sash tied in a bow, and his jutting elbow clad in a gorgeous pink banded sleeve. He holds out his upturned palm to a beady-eyed old gypsy who pinches a large coin above it as she tells his future. Age and exposure to the elements are written in the dark creases of her face and neck. Her ugliness is a foil to the brood of pretty gypsies who are her companions, including the dark beauty at the left who is carefully extracting the youth's purse from his pocket. Another of La Tour's memorable inventions, standing between and behind the old gypsy and the dupe is the young woman, whose pale, perfect egg of a face sets off her incomparable sidelong glance. She quietly snips the links of the gold chain hanging precariously over one shoulder of the young man, holding it up so that he will not register the weight of the medal suspended from it when it is gone.

La Tour's and Caravaggio' s six pictures have in common the crucial element of a willing victim. Their contemporaries would have recognized these young men dressed in fine clothes-handsome, confident, and nai:ve-as modern-day youths who stand in for the prodigal son. They are descendents of the irresistible protagonist of the biblical parable: the youth who comes of age and sets out to seek his fortune. He falls in with worldly company, squanders

pink ypsy 1re to iness ding from -veen pale, ietly er of f the

nent )Ung lern-f the ·age 1ders

Gail Feigenbaum 261

his patrimony, and is reduced to living in squalor. While the prodigal's eventual homecoming to a forgiving father was also a frequent subject, Northern Renaissance artists relished the genre potential of the prodigal's dissipation amidst wine, women, and gambling. In general, their approach was explicitly moralizing and frequently took the form of tavern scenes where a merry company indulging in drinking and gambling is likely to cross over into drunkenness and brawling. Amid the debauchery, the prodigal is recognizable in his finery, and neither he nor his purse fares well. In Italy, by contrast, the prodigal son theme was rarely made explicit in painting, but, as in Spain and France, his story is retold in widespread picaresque literature and related theatrical forms. In Caravaggio' s treatment, the prodigal theme is effectively sublimated, overt moralizing is absent, and the connection seems rather to be with the picaresque.

The Netherlandish Caravaggisti enthusiastically appropriated The Cardsharps and reinoculated it with the prodigal tradition to pose a robust warning against immoral conduct. In Dirck van Baburen' s and Hendrick ter Brugghen' s works, the gamblers are portrayed as mercenary troops, who were notorious gamblers and who often played for stray pieces of armor that had been scavenged from fallen enemies.14 The theme was thoroughly secularized and most richly developed in the picaresque and criminal literature in Spain and England.

The world into which the prodigal son and his picaresque cousins wander may have been real and rough, but it inspired outstanding literature and art. Passages from Elizabethan tales, such as Thomas Dekker's The Belman of London: Bringing to Light the Most Notorious Villanies That Are Now Practiced in the Kingdom, read like descriptions of paintings of the Caravaggisti.15

Published in 1608, this tract is couched as an eyewitness chronicle of the bellman who walks about the city by night with his lantern and candle, exposing with relish the seamy underworld of crimes and con games for his readers, who are specified as gentlemen, lawyers, merchants, citizen farmers, and masters of households. While it pretends to be a helpful guide warning readers of the schemes and treachery to which they might fall prey should they go about the city at night, it is a decidedly entertaining account for the delectation of those who were of a social status that tended to insulate them from such dangers. Many of the nefarious doings Dekker describes involve expert bands of swindlers who gain the confidence of young heirs dressed in fine satins and often referred to as prodigals. These predators and their prey are the characters played by the figures in La Tour and Caravaggio.

Painters of different nationalities and sensibilities colored their depictions of these themes with their own moral judgments. None of the French Caravaggisti was inclined to the Netherlandish didacticism, and La Tour least of all. Vouet's versions tend toward a broad rustic comedy, a buffoonish commedia dell'arte spirit. Valentin's scenes threaten to end violently. A dark undercurrent also runs through La Tour paintings, suggesting an indictment of society that is more cynical than biblical. Still, the typical prodigal

262 CARA V AGGIO

iconography lingers in La Tour's Cheats, with wine and women as agents of corruption. Callot's famous print The Prodigal Son, a clear source for La Tour, makes vivid the proximity. Despite his wit, La Tour's bitter transposition of the parable stages it as a contest between appearance and truth, holding out no hope for redemption.

La Tour's willing victim in the Cheat is imbued with the obtuseness of a dumb animal, a characterization that brings to mind the French word bete in both its senses as "beast" and "stupid." His pudgy face is contrasted to the vulpine features of the cheat, whose foxy cunning will be the boy's ruin. To read the paintings in a physiognomic key, be it animal or human, is instructive. It registers a translation into the visual of the animal vocabulary that is pervasively employed in contemporary dictionaries of criminal slang, and tracts on the criminal underclass published in French, English, Italian, Latin, and German. 16 Thomas Dekker described this criminal activity as "city hunting," comparing the predators and their quarry to con men and rabbits or "conys." To read about swindlers and cheats in the period literature is to enter a veritable barnyard argot of predators and victims. Foxes and wolves circled chickens and geese; plump fowls were plucked; lambs were fleeced or led to the slaughter. Gulls and dupes, the former deriving from a bird thought to be exceptionally stupid, were common terms for victims of deceit. The young victims are callow, the adjective meaning "featherless," "unfledged." To swindle is plumer in French slang, the old expression being to pluck the chicken without making it cry, so the victim is done for before he even notices. Typical of this is this passage from the seventeenth-century tract The Complete Gamester:

These rooks [crows] are in continual motion walking from one table to another til they can discover some inexperienced young gentleman, being unskilled in the quibbles and devices there practiced; these they call lambs; then do the rooks, more properly called wolves, strive who shall fasten on him first, fastening him close, and engaging him in some advantageous bets, and at length gets all his money, and then the rooks laugh and grin saying, the lamb is bittenY

In Caravaggio's The Cardsharps (Fig. 12.1) and in La Tour's Cheats (Figs. 12.4 and 12.5), the youth is such a lamb to the slaughter, with his creamy neck exposed to the wolves and foxes. The metaphor also applies to the young man surrounded by four cunning women in La Tour's Fortune Teller (Fig. 12.6). There is no mistaking the import of the design of the gypsy's tapestry robe, prettily patterned with rows of birds of prey whose beaks and talons menace the dumb bunnies below. La Tour's paintings straddle the interlude between Giacomo della Porta's treatise on physiognomy and LeBrun's lectures, which employ resemblances between human and animal features as a means to indicate character. La Tour belonged to the generation preceding La Fontaine and Perrault, and their moralizing tales of sly foxes and wolves in disguise and vulnerable victims in fine new clothes do not seem distant.

E con: thes also best civil quo be s dee trea pai1

I ad bee sub for am1 slm gla ha\ by con Cm eU

l elal vie syr wit ten a v an La ass pat wo car thE we car COl

ga1 cht

for

; of >Ur,

t of out

>fa )ete ted >y's t, is ary ng, ian, :ity bits s to ves i or ght fhe

the ces. 1lete

'igs. tmy the

eller sy's

idle and mal tion )Xes not

Gail Feigenbaum 263

Each of La Tour's three compositions pivots on a sidelong glance so conspicuous that it invites further attention. Today's viewer probably reads these looks as shifty, perhaps by instinct. But for contemporaries, they were also explicitly, literally freighted. Erasmus in his Manners for Children, the best-selling book of its century and ubiquitous in La Tour's France (as La civilite puerile), cautions that for an honest person, "sint oculi ... non limi, quod est suspiciosorum et insidias molientium" ("the glance ... should not be sidelong, which is a sign of cunning, of a person contemplating a wicked deed").l8 The painter stages all of this-the shifty gaze as a clear sign of treachery-for the benefit of the spectator who takes it in, and who, like the painter, is privy to what everyone in the picture is up to.

It is a given that an educated collector would have had knowledge of a classical literary canon, would know his Virgil and Cicero, would have been able to appreciate the fine points of a painter's interpretation of subjects drawn from this tradition. It must be stressed that the audience for La Tour's gambling pictures would likewise have been alert to the amusing analogies of animal physiognomy and common underworld slang, and would have recognized the corruption signaled by the shifty glances. La Tour also could take it for granted that his audience would have understood the rules and play of the card game. As we read in a letter by Cardinal Del Monte recounting an evening spent in the high-spirited company of Cardinal Aldobrandini-nephew of Pope Clement VIII-and Cardinal F arnese, there was a gioco d 'azzardo in which "si fece gran ba ttaglia et Aldobrandino et io perdessimo se bene io pili di lui."19

It is this quite practical and intimate order of knowledge rather than an elaborate reading of card symbolism that La Tour enlists in order to elicit his viewer's complicity. Attempts to interpret The Cardsharps according to card symbolism have failed to convince. The very plenitude of meanings associated with every number in every suit in the vast contemporary literature on cards tends to undermine the method so that one is forced to pick and choose from a very large range of possible meanings for the cards, which can generate an almost unlimited array of interpretations.20 More likely here is that both La Tour and Caravaggio assume their viewers' knowledge of gambling, an assumption borne out by the fact that the Roman cardinals and noble French patrons who bought their paintings were no strangers to gambling.21 They would have appreciated the fact that La Tour and Caravaggio chose their cards to set up a winning hand of 55 points in the game of primiera or prime, the most popular card game of its day.22 "To describe what Primero [sic] is would be little less than useless," remarked an early commentator, "for there can scarcely be anyone so ignorant as to be unacquainted with it."23 The artists could count on their audience to be in the know, thoroughly versed in the game, to recognize the dynamics of play and tactics of the con artists who are cheating their way to the winning hand of prime, or cinquantacinque.

Primiera, a lively game depending on chance but with good opportunities for skill and daring in bidding and bluffing, was much written about and held

264 CARA V AGGIO

rich potential for allegorical interpretation. In a sixteenth-century poem by Mellin de Saint-Gelais, for example, the struggle for control of Italy among Francis I, Pope Clement VII, and Charles V was rendered as a game of prime: politics, military deployments, the respective assets and weaknesses of the rulers are represented in the terms of the play of the game.24 This is not to suggest that the paintings by La Tour and Caravaggio operated as political allegories of this kind, but rather that such games often carried a heavy symbolic freight. Games of chance are related to time and the future: their basic accessories-dice and cards-are also those of the fortune teller. Time, the future, destiny, and political power can be represented as games, and Mikhail Bakhtin describes the images of games encountered in literature-not to mention paintings-as condensed formulas of life and historic process.25 It is worth asking the next question: how are fortune and destiny tied up with religious views in Counter-Reformation Europe with the concept of chance as divine-the will of God written in every roll of the dice-and gambling and cheating as abuse? Notice the glittering pile of coins in La Tour's Cheats and the coin crossing the palm in his Fortune Teller. They force the questions of where the essential coin is in Caravaggio' s two versions of The Fortune Teller. And in the absence of coins on the table, what is at stake in Caravaggio's The Cardsharps? Some dimension of moralizing refuses to be scrubbed absolutely from the paintings.

If the moralizing dimension in the paintings of La Tour and Caravaggio does not assume the form of explicit judgments and warnings, it seems to operate in the more elusive vein of Cervantes's nearly contemporary Novel as ejemplares. Published in 1613 (though written earlier) after Caravaggio's death, they bring to life a picaresque underworld with characters that could have walked out of one of his paintings. Walter Friedlaender saw a parallel between Caravaggio's Fortune Teller and Cervantes's treatment of the inconsequential adventures of young cavaliers in a gentle and romantic manner, smilingly and ironically.26 An affinity between Caravaggio and Cervantes is even more compelling in the story Rinconete y Cortadillo, which must reflect Cervantes's experience of having being stationed in Naples with the Spanish navy. Rinconete, the title character-it is easy to slip and call him the hero-sounds like Caravaggio's cheat come to life when he boasts: "I know a bit about card tricks, I can keep a card back, recognize marked cards. I'm not slow when it comes to marking cards so you can know them by touch. I'd sooner rally a band of sharpers than a regiment in Naples." Cervantes's exemplary novellas, with their vivid characters drawn from the piazza, have much in common with what in painting came to be called "genre subjects." Their plots are driven by deception, and they are populated by characters who seem to be something that they are not, whose very appearances deceive. Ostensibly, they are offered as moral examples, yet their complexity and ambiguity defeat any attempt to extract that example. By convention, literary or pictorial, a moral is expected in Cervantes and Caravaggio, but both creators are evasive, too

>em by among f prime: . of the . not to •olitical heavy

e: their ·.Time, es, and re-not :ess.25 It 1p with ance as ng and ats and :ions of e Teller. io's The ;olutely

tvaggio to

Novel as aggio's

that r saw a nent of >mantic ;io and , which Naples •lip and rhen he :ognize rou can

uacters •ainting :eption, lat they 'ered as attempt :toral is ive, too

Gail Feigenbaum 265

sympathetic, or at least ambivalent, in their delineation of characters to make an example of them.

Long after the publication of Cervantes's Novelas ejemplares, his gypsies and cheats flourished both on the pages and stages of Europe. If Caravaggio' s connection was indirect-through common literary sources, popular theater, and a kindred sensibility-La Tour's connection may have been both direct and mediated through theater. The porcelain-skinned beauty with the oblique glance in La Tour's Fortune Teller can be identified as the character Preciosa, who is the protagonist of Cervantes's exemplary novel La Gitanilla (The Gypsy Maid).27 La Tour and his patrons would have found it difficult to avoid some acquaintance with Cervantes's La Gitanilla, as it was translated into French the year after its original publication, having gone into five editions during La Tour's lifetime. Several popular contemporary French plays were inspired by the story.28 In Cervantes's intricate plot of mistaken identities concealed and revealed, Preciosa, daughter of nobility, was kidnapped by a gypsy woman who hid the child's true identity and reared her as a gypsy. Ignorant of her own past, Preciosa grew up to be the loveliest of the gypsies and skilled in their ways. When a handsome cavalier falls in love with her, she makes him prove his worth by living in disguise as a gypsy. The many twists and revelations that follow are not germane to La Tour's painting, but the mechanisms by which the plot unfolds with knowledge selectively revealed and concealed to various actors and to the reader are of the essence. Cervantes sets Preciosa apart from her gypsy companions by her fair skin, for "neither sun nor wind, nor all those vicissitudes of weather ... could impair the bloom of her complexion or em brown her hands." By means of Preciosa' s complexion, La Tour reveals her true identity to the viewer, who shares this privileged knowledge only with the old gypsy hag, who both controls and embodies deceit. Corruption is skin-deep.

In appropriating the characters of Preciosa and the old gypsy and deploying them in a vignette of fortune telling and thievery, La Tour mines La Gitanilla more as citation than narrative. La Tour did not select a particular episode to depict from a story that brims with promising possibilities. Unlike Cervantes, La Tour neither extolled the joys of gypsy liberty nor told the wildly romantic story of the dashing cavalier who lives as a gypsy out of love for Preciosa. In fact, La Tour's portrayal of Preciosa conflates and reduces her history and character in a way that does not conform to Cervantes's milder characterization. In his opening lines-"gypsies had been sent into the world for the sole purpose of thieving" -Cervantes established that thievery is the basic condition of gypsy existence, but he does not mention Preciosa's participation in such crimes and, in general, keeps theft offstage. In La Tour's appropriation of La Gitanilla's characters instead of the plot, he selects, focuses on, and abstracts his themes, without distraction. He stages Preciosa in pure terms of appearance and deceit, so that the essence of the story can be seen-noble birth, knowledge and ignorance, beauty and ugliness.

266 CARA V AGGIO

La Tour took La Gitanilla not to illustrate, but as a point of departure for his own virtuoso construction and dissection of an image true and false. The rather indeterminable costume of the young man and several anomalies in its details have troubled experts. For example, the beautiful bow of his red sash would not normally have been tied front and center, and his jerkin may well be worn back to front. An embroidered strip of fabric serves as an improvised collar. The incongruities even led some scholars to challenge the authenticity of the painting, but subsequent research turned up a solid old provenance and the inescapable conclusion that the oddities were La Tour's own. I have argued that these improvisations and inversions are intended to signal to the viewer that-like Preciosa-this young man with his very dirty fingernails is not quite as he first seerns.29 Away from horne, a young man with an undistinguished social background and a handsome appearance, tricked up with a fine-or fine enough -suit of clothes, could pass himself off as someone above his station. La Tour's young man brings to mind a story like the one told by Fran<;ois de Calvi in his more or less contemporary Histoire generale des larrons (1631 ), in which a band of vagabonds near Paris dress up a youth in an improvised set of fine clothes, and then live it up at an inn while they pass him off as the nephew of the Dutch arnbassador.30 He is, in the words of Thomas Dekker, "a man dressed above his quality." The wary expression of La Tour's young man suggests that he is so preoccupied in fooling others with his false appearance as a gentleman that he is oblivious to the quick fingers stealing his purse and gold chain.

In La Tour's Fortune Teller, all the actors engage in trickery and are themselves deceived. No one among them knows the whole truth. Both the lies and the truth are known only to the painter, who shows them to the canny spectator. The moral that appearances are deceiving is complicated by the milk-white skin of Preciosa. For just as in the case of the handsome young man who is a poseur, and whose appearance gives us both the false and the true about him, it is precisely Preciosa's appearance that reveals the truth about her identity. La Tour goes in here for a triple cross: the gypsies' true nature is fraudulent, and so their appearance here is authentic and true. To offer them your palm is to play the willing victim. The young man is not merely a willing victim but also perpetrates his own deception by passing himself as someone he is not. And Preciosa, ignorant of her true nature, has been tricked into a life of duplicity that is false to her genuine character. Yet her very appearance betrays-to the viewer of the painting-both the truth about her noble origins and the false life she leads with the gypsies.

In the fortune teller pictures by Caravaggio and La Tour, complicity shades into seduction. Beauty itself is the fatal weapon that easily overpowers an all-too-willing victim. A susceptible young man with a head full of dreams and ambition succumbs to the charms of a lovely seductress. Seduction is a game of pretense, of conquest, with winners and losers. There is no mistaking the import of the exchange of glances between the lovely gypsy and the handsome youth dressed to the nines in Caravaggio's two versions of The Fortune Teller.

c Sl w

P< to is

tc vi cc tr OJ

p< tr tr tr fc a

cc is

a si C<

st v tl

c C<

tre for e. The 'in its :l sash y well wised nticity

I have to the

ith an ;ed up neone .1e one 'ale des 1inan sshim homas Tour's is false inghis

1d are >th the canny

by the tgman 1e true about

tture is rthem willing meone into a

'arance origins

shades an all-

ns and :lgame ing the ldsome ? Teller.

Gail Feigenbaum 267

Caravaggio's young man is ripe to be lured into a relationship that he must surely know will make a fool of him. And La Tour's cavalier, though he is watchful and guarded, stands no chance while surrounded by such gorgeous gypsies. Both painters allegorize seduction as a model of relations between painter and spectator. These paintings are beautiful, and beauty is the weapon to which succumbs the all-too-willing victim of a spectator whose pleasure it is to be seduced by the painting.

All of these pichtres turn on the theme of deception painted truthfully to nature. Each of the paintings of cheats is compositionally centered on a vignette of complicity, on a tacit communication between insiders, who con a willing victim. It is precisely this set of triangulated relations within the painting that is extended and mirrored in the relationship between the onlooker and the painting, or, by extrapolation, the man who created the painting. The painter tips his hand, literally and figuratively, to ensure that the viewer is shown the false cards and that he detects the connivance between the cheat and his accomplice-the exaggerated glances and furtive gestures in the La Tour and the theatrical gaze and gesture in The Cardsharps are acted out for the spectator's benefit. And the spectator must register the fact that this is a performance. Moreover, the full appreciation of each of these paintings is predicated on the viewer's assumed knowledge of the game of primiera and the fact that a winning hand is at stake in this cheating play. So the scene of complicity within the painting is restaged in the act of viewing. The spectator is included, he or she is in the know.

Yet another set of relations is being restaged in the act of viewing, and this time the viewer takes the part of the dupe. For at the same moment that the viewer is enjoying the insider's pleasure of knowing what is really going on in the painting, he is being fooled into believing that what he sees is real, tricked by the painter's ability to simulate the appearance of reality by moving pigment around the flat surface of a canvas. It is a brilliant illusion for which the equivalent Italian term is inganno, or deception. The figures, who resemble people one would find in the streets of Rome or Lorraine, seem to pop into three dimensions, to occupy space and move, to watch, listen, and react to each other. Bellori tells this kind of story in his famous description of Caravaggio pulling a youth and a gypsy off the street to serve as models for The Fortune Teller. Truth to nature-in Bellori's terms, the painter as naturalista-is a problem whose complexity and contradictions are modeled in the deceptive simulation of what is itself a deception. Represented within the painting are conspirators and the dupe who plays eagerly into their hands. The actors stand in for the painter whose new naturalistic manner tricks his complicit victim of a viewer who is willing to believe painted lies even while knowing that they are false and that he is being deceived.

The theme of deception seeps into the social environment in other ways. Caravaggio's cardsharps and fortune tellers-like his fruit still lifes and concerts-belonged to the first generation of portable easel paintings that were being collected, bought, and sold as commodities. Cardinal Del Monte

268 CARA V AGGIO

probably acquired the paintings through a dealer. At this early date, a dealer could occupy a place almost anywhere on a social continuum between the rigattiere, who sold used goods, to a rather more elevated gentleman who himself owned a stock, "a collection" of pictures from which he let acquaintances make acquisitions. Such middlemen performed a service, negotiating the painting's trip from the artist's easel to the walls of the cardinal's gallery.31 Such men earned their living from these transactions, partnering with the artist to sell his work and get a good price from the cardinal, sometimes uneasily-perhaps deceiving or cheating the artist of his rightful share of the proceeds and perhaps fooling the customer into paying a higher price than the going rate. So lurking in the iconography of The Cardsharps is yet another web of deceptive relations in which middlemen orchestrate a transaction in which both painter and buyer are vulnerable to being duped.

In their cheats and fortune tellers, Caravaggio and La Tour portray with unprecedented truth to appearances all that is false. They both chose to transfigure low subjects by treating them in a refined manner appropriate for high subjects such as sacred history. This practice is the converse of their conscious introduction of low motifs, indices of truth-the soles of dirty feet, the rustic actors-into sacred subjects, and once again it is not coincidence but a kindred mentality that links the two painters in this regard. Moreover, their lifelike treatment of the themes of deception is the converse of their aim in religious painting to create an image of truth by means of a perfect technique, a truth that is perfectly true.32

La Tour's and Caravaggio's cheats offer a modern twist on the oldest con game in the history of art: the trompe l'oeil of Zeuxis painting grapes that fooled the birds and of Parrhasius painting a veil over the grapes that fooled Zeuxis. 33 The point is that this is a contest of the imitation of nature in the form of a game. What is new circa 1600 is that the game itself is false-as if Zeuxis had painted a bunch of fake plastic grapes in the first place. As I have already said, in these high-style low-life pictures of gypsies and cardsharps, the artists portray with unprecedented truth to appearances all that is false. La Tour's Fortune Teller presents a young man whose true self is betrayed by his lying appearance, who fools only himself as he is seduced by the lies and beautiful appearances of gypsies whose own true metier is deception. And one of these gypsies, Preciosa, is, but is not, a gypsy. Like the young man, Preciosa is not what she appears to be and yet, at the very same time, she is truly what she appears to be. Her true nature, concealed even from herself, is betrayed to the spectator by her appearance. La Tour constructs a hall of mirrors whose dizzying reflection is caught in the illusory mirror of nature-the artist's canvas. Echoing in Bellori's later play of words such as counterfeit, feigned, fictive, false, and fraudulent, the madrigal written in 1603 by Gaspare Murtola on Caravaggio' s Fortune Teller which I evoked in the beginning, captures the crucial theme of being bewitched by the painter into believing what is false as true:

a dealer between ntleman :h he let service,

ls of the sactions, from the artist of

mer into ;raphy of ddlemen ,erable to

tray with chose to

propriate ;e of their dirty feet, dence but )Ver, their 2ir aim in echnique,

)ldest con rapes that hat fooled n the form s if Zeuxis ve already the artists La Tour's

y his lying i beautiful ne of these :iosa is not y what she ,etrayed to :ors whose the artist's it, feigned, tre Murtola

the hat is false

I do not know who is the better magician The woman you depict Or you who paint her Through her sweet charms She is longing to dispossess us Of our heart and blood. You make her, who seems depicted Look alive You make others believe That she breathes and lives.34

Gail Feigenbaum 269

The painter deceives by making an image as convincing as nature itself. But here the object depicted embodies the falseness of appearances. The more perfectly the artist counterfeits nature, the greater and the more beautiful his lie, and the greater the fool who is willing to pay for the privilege and pleasure of believing him.

Notes

1 Shakespeare, Macbeth, act 5, scene 5. The catalogue Caravaggio & His Followers in Rome (The National Gallery of Canada and The Kimbell Art Museum, 2011) was published too late to be considered in this essay.

2 Bellori, 204.

3 "Non so qual sia pili maga I o la donna, che fingi I o tu chela dipingi."

4 Bellori, 203.

5 Feigenbaum 1996 treats the subjects of deception in the work of Caravaggio and his followers; it discusses Italian, French, and Netherlandish reception of the subject; identifies specific visual, literary, and theatrical sources for some of the paintings; and explains the play of the game and techniques of the cardsharps. It also introduces the idea of allegorization of naturalistic painting in these themes of deception, and discusses the practice of gambling among the classes who bought pictures of card players. The study has been overlooked in the literature on Caravaggio, possibly because it appeared in an exhibition catalogue devoted to Georges de La Tour, with the exception of Porzio 1998, which incorporates several of my arguments, particularly about Cervantes.

6 Corradini and Marini 1998.

7 Spezzaferro 1971 and Wazbinski 1994 remain the fundamental studies.

8 Also variously called primero, primera, or prime.

9 See Feigenbaum 1996, 156, on this technique of cheating. Moffitt 2002 identifies the man with the moustache as a gypsy because of his dark skin and striped sleeves, and his interpretation of this painting and the two versions of The Fortune Teller turns on an emphasis of the ethnicity of the gypsies and contemporary attitudes toward them.

10 On Caravaggio's carpets, though this painting is not discussed, see Varriano 1986.

11 For Del Monte's inventory, see Frommel1971; the paintings are noted in the inventory, f. 464r, in the "Galleria Contigua" to the "Gallaria Nova Stretta":

270 CARA V AGGIO

"Un gioco di mana del Caravaggio con Cornice negra di palmi cinque"; "Una Zingara del Caravaggio grande Palmi cinque con cornice negra." In proximity to these two paintings was also "Un' Quadretto nel quale vi e una Caraffa di mana del Caravaggio di Palmi dua."

12 Feigenbaum 1996, 152.

13 Wind 1997.

14 See Feigenbaum 1996, 161-62.

15 For The Belman of London and Lantenz and Candlelight, see Judges 1930, 303-65.

16 See, for example, Modo nuovo de intendere Ia lingua zerga, 1545, a dictionary of low-life slang.

17 Cotton, 334.

18 Erasmus, 3, as translated in Revel1989, 169.

19 Zapperi 1994, 87.

20 See Wind 1989.

21 One of his patrons, Governor La Ferte of Lorraine, for example, was a notorious gambler, for which see Reinbold 1991, 153, but the continuous efforts to outlaw or reduce gambling among all classes attest to the fact that it was widespread and presented a problem.

22 Singer 1816. See also Feigenbaum 1996, for further bibliography.

23 Singer 1816, 245.

24 See Bakhtin 1984, 232.

25 Ibidem.

26 Friedlaender 1955, 84. On popular Italian sources such as the zingaresca, a gypsy song commonly sung with gestures and staged informally in piazzas, see Feigenbaum 1996, 169; Olson 2006; and more generally Bragaglia 1958, 87-114. Zingaresche were written down and elaborated, as evidenced by such manuscripts as the "Commedia di un villano e d'una zingara che da Ia ventura" for which see Bragaglia 1958, 93. Caravaggio would have seen zingaresche, but it is difficult to gauge the sensibility of these performances or what might have been their impact on the paintings.

27 Feigenbaum 1996, 176. Cuzin 1977, 22, noted a connection to La Gitanilla, and Preciosa was suggested by Odile Basch Jacobs in her unpublished master's thesis, Queen's College, London, for which reference thanks are owed to Leonard Slatkes. Gaskell1982, 263-70, does not consider this iconography beyond the Dutch tradition.

28 Preciosa became so entrenched in the French imagination that she eventually became the inspiration for the character of Esmeralda in Victor Hugo's Hunchback of Notre Dame.

29 Feigenbaum 1996, 176 and 181, nn. 68 and 69.

30 Calvi, 13-14.

31 See Cavazzini 2010.

32 Spezzaferro 1971.

";"Una ·oximity to a dimano

303-65.

:1ary of

t notorious to outlaw

,espread

;ca, a Jiazzas, 1958, by such la ventura" ·esche, but aighthave

zilla, and aster's !d to raphy

.rentually o's

Gail Feigenbaum 271

33 Pliny, Natural History, 35:35.

34 Murtola, madrigal472, for which see Cinotti 1983,485: "Non so quale sia pili maga I 0 la donna che fingi, I 0 tu che la dipingi. I Di rapir quella e vag a I Coi do lei incanti suoi I II coree 'I sangue a noi. I Tu dipinta, che a pare I Fa, che viva si veda. I Fai, che viva, e spirante altri la creda," as translated in Pericolo 2011, 139.