'OUTHERN CHOOL EWS Objective - Tennessee Virtual Archive

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of 'OUTHERN CHOOL EWS Objective - Tennessee Virtual Archive

Factual 'OUTHERN CHOOL EWS Objective

VOL II, NO. 5 NASHVILLE, TENN. $2 PER YEAR NOVEMBER 1955

Three Courts Annul State School Laws " School ' l

Cons t r u c.· l ion Exp enditures Sin ce 1949 I lj;:

'li

Aloboma ,. ' ArtcCIIUaS r ~ Delaware ~

II lllsf, of Columbia I.-I<! en florida d: cr. Gtorgla

~ t)' 1 l(elltVCkY Sit

:l! ' Louisiana ill be; MarYJand .~

~ Mississippi .r...., Itt ~ n Mirth Carolina

ll" i::.izC Oldohoma Jll:l f1 South Carolina ) ~

Yl Tennessee th

' ·>?~ WeJt VIrginia

( In Millions of Dollars)

0 50 100 150 200 , , , , , - 110 1

2

Ela1 ~ 44 I 35 I

250 ,

- 3 ~ 60 ~

~ 60.5 l4

-~-Se;it

it ~ Expended Approved

300 350 400 , , ,

50

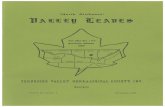

liJ I ~ L.i Spuued on by rapidly growing numbers of school age !n='daildren and by realization of the need for more adequate di¥t.wJcling, Southern states have, in the past six years, spent 'CIS(• approved more than two and a half bilUon dollars for blaCIDIIStruetion of new (acilities. The figures shown in the

r !Ao2Move bar graph are, of necessity, incomplete. They do, !f Jt however, show something of tho relative rate of cons~c~U.. in the states and tho Dist rict of Columbia faced With goesJ IIIe problem of racial integration in their schools. While ~1141 appears to have marked d1e start of the period of in-

tens:ive school construction, Ligures for the whole period in some cases were unavailable. By way o( further explanation it sh ould be noted that the Alabama figure of $1l0 million approved represents an amount of school bonds authorized by the state legislature but subject to approval by the voters in a referendum scheduled for Dec. 6. The tota.l of $2,556,500,000 does not include approximately $85 million spent during the period in Missouri which is not included in the graph.

n»l I. ~Deludes state, tout and redcrnl Cund~ us.i $ Z. lxpe.ndltures since 1951 •j\sf.o

3. Program began prior Co 1949 4. Expenditures for latest biennium

x: c~il\T ;:.\l~egro Teacher Tenure Is Surveyed

. A sense of insecurity, marked by a ~COIISistent if weakly held fear of loss .3"'ol jobs, hanging over many Negro ~:~ 1te.chers is one result of the Supreme !II ~Court's decisions against public 1 ;3Cbool segregation and subsequent ~'l:Ourt attacks on the South's biracial &I ilpattern of education, according to an ~i ;~xdusive survey by SouTHERN SCHOOL !..;.;:'b:ws. t«iill However, there is no indication tvlll" .hat either this fear or other compul-

lions will lead Negro teachers to suplOft continued segregation in the

~ools. / Perhaps one reason for this is that ••fi ob losses as a result of desegrega-11' ion or of pressure arising from the r1~ chool s e greg a t i o n issue have

10 tntounted to less than 300 out of the 1PProximately 75,000 Negro school

h. ~l eachers in the Southern and border ~~ lates. Furthermore, apparently few

! fegro educators fear that the public /chools of the region, so long in de

eJopment, will be abandoned. These reasons, plus the fact that

!aching is one of the better-paying lfOfessions open to Negroes in an rea where teachers generaUy are ' short &upply, probably explains •hy there has been no widespread )llc:ern about. this aspect of the school !gtegation question. .ESS 'DISCOURAGING' So far, only in Oklahoma, where

esegregation has occurred in some 50 of the state's 1,800 school districts.

/

has the displacement of Negro teachers raised much apprehension. And even there, John W. Davis, teacher tenure director for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, found in July that the situation "was not nearly as discouraging as a good many people think."

At last accounting, 144 teachers and 21 principals had lost their jobs as a result of desegregation. Only four teachers had been integrated into mixed schools and these as counselors for Negro students. But. one principal has _bee~. p_romotE;d. ~? s_u= perintcndent m a L1ttle D1x1e dis trict.

Next largest number of displacements because of integration was reported in West Virginia, whe:e state school authorities are conumtted to a policy of desegregation. Here .o~y seven Negro teachers and 1~ prtnCJpals have been displaced, w1th 46 of the state's 55 counties desegregated or moving in that direction. But 83 of the state's total 973 Negro ~eache~ had been integrated along With then· s tudents.

Some displacement reportedly has occurred in Missouri, but since ~ecords in this highly decentraltzed school system are no longer kept on a racial basis, statistics were not available. In September, however, the office of the NAACP teacher tenure director indicated that the teachel'

situation in that state had been worked out satisfactorily. FIVE IN TEXAS

In Texas, five Negro teachers have been displaced in Kames County. In

(See TEACHER TENURE, Page 2) ..................................... , Johnny Can Bead

SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS Bc~nnins witlt the first issue

or Volume II, SOtrniERN SCHOOL NEWS hna been made more read· able for the busy educator, public officialll, school board allor· ne:r ••.

The Page 1 summary gives you the whole month's aetivitiee in capsule (orm.

Then, tlte " lead" on each state report summarizes what has happened in slightly extended form.

Finally, under the topical b ead· in18 you will find more detailed accounts o£ these events: "Legal Action," "School Boards and ~hoolmen," "Le~slative Ac· tion," " In the Colleges," " What They Say," and eo on. A new deportment has been added this m onth. It'e called: "Community Action."

Only SotJTUERN SCHOOL NEWS offers a complete, unbiaaed n1onthly roundup of' the biccest education s tory in the South today.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••c•••••••

C OURTS in three states-two of them state supreme courts-struck down constitutional or statutory provisions for public school segregation during

October. Again it was a busy month on the legal front, as elsewhere and notably in the

Deep South groups opposed to desegregation drew new recruits to their ranks. SoUTHERN ScuooL NEWs counted at

least 21 private organizations opposing compliance with the Supreme Court decisions that were active in one or more of the 17 traditional segregation states save Kentucky and West Virginia. Oklahoma reported the first organization of a Citizens Council, a movement which was spreading out of Mississippi into Alabama, Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina, Texas and other states.

• The three major court rulings were

in Florida, Texas and Tennessee. In Florida, in a case involving ad

mission to the University of Florida and remanded to the state court by the U.S. Supreme Court, a &-2 decision by the state Supreme Court nullified state segregation laws. However, the court allowed time for integration by orderly procedures.

In Tennessee a federal district judge held that "the Supreme Court had said very definitely, if it has said anything, in its latest pronouncement that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional and all provisions, state or local, calling for racial discrimination must yield to this principle." At the same time, and over protests of counsel for Negro students seeking immediate admission to Memphis State College, the court upheld a Tennessee plan for gradual desegregation of the state college system, beginning at. the graduate level. It was the first ruling in any court dealing with a "step-bystep" integration plan.

In Texas the state Supreme Court ruled that schools may proceed with desegregation without regard to state laws, declaring invalid provisions of the state constitution and the school laws which required racial segreaation. In the main opinion Associate Justice Few Brewster called "utterly without merit" the argument that Texas segregation laws were unaffected by the U.S. Supreme Court decision.

• Reports coming to SSN after school

opening showed meanwhile that seven more schools in Oklahoma now have mixed classes; that one more county in West Virginia has ordered desegregation (effective in January), and that 24 of Kentucky's 224 districts have adopted desegregation.

Little or no segregation activity was reported from the states of the Deep South, where the accent was on the organization of protest groups.

A state-by-state summary of key developments follows:

Alabama The U.S. Supreme Court ordered

two Negro women admitted to the University of Alabama without waiting for the outcome of an appeal from a federal district court order opening the doors of the university t.o all qualified Negroes. Several of the governors attending the Southern Governors Conference at Point Clear expressed the view that school segregation will not be an issue in the 1956 elections.

Arkansas A federal district judge at El Do

rado said he expected to order integration at Bearden school district within a year. The Hoxie school reopened without incident but with many absentees. Representatives of White America, Inc. filed suit against members of the school board, alleging irregularities, while the board obtained in federal court a restraining order against interference with the operation of the schools.

Delaware Dover High School (integrated) set

up a unique athletic policy calling for

segregated games away from home but requiring visiting teams to play return games in Dover against integrated squads. The House of Repr~ sentatives passed the pending $44 milljon school bond bill. retaining the controversial "C" classification.

District of Columbia Parents and school authorities were

involved in a controversy over a teacher shortage and overcrowding of the schools-conditions traced in part to administrative problems flowing from the integration of the school system.

Florida The Supreme Court in a &-2 ruling

knocked out Florida school segregation as a legal principle, holding compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court decision to be "our inescapable duty." However, it said the federal ruling does not require "a clear legal duty" to admit Negro students to schools "at any particular time in the future." One of the justices said the ruling did not go far enough and the other minority member questioned integration on principle. Biracial committees were at work in one-third of Florida's counties to survey the school situation and make recommendations.

Georgia Atty. Gen. Eugene Cook and Ex

ecutive Secretary Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People traded verbal blows over the issue of whether, as Cook charged, the NAACP was "subversive." Forty-four Negro parents filed a school admission petition in Waycross--Georgia's sixth such petition- while the State School Boards Association, meeting in Athens, said that the "legal conflict between federal and state authority must be resolved before local school boards can do anything more than study the question of racial integration in our schools."

Kentucky Twenty-four of Kentucky's 224

school districts reported desegregation, involving some 300 Negro children who were attending mixed classes.

Louisiana The state was still awaiting the

outcome of litigation over a $100,000 state fund for use in combating integration efforts and attempts in St. Helena and Orleans parishes (counties) to gain admission of Negro children to all-white schools.

Maryland Mixed classes were reported in

eight of 22 counties having Negroes of school age, plus Baltimore Cit.y. The Maryland Petition Committee, opposing integration, renewed its

(See COURTS VOID, Page 2)

Index State Page Alabama ........................ 9 Arkansas ........................ 3 Delaware ....................... 14 District of Columbia . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 Florida .... .. .................... 4 Georgia ......................... 15 Kentucky ................. . ..... 16 Louisiana ... .. . .......... . ...... 16 Maryland .. .............. . ...... 10 Mississippi .. . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .. . . .. 7 1\Jlssou ri . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ....... 14 North ~Lhta ................... 13 Oklahoma ................. . .. . .. 12 South Carolina .. . . .. . . . . .. . ... . .. ll Tennessee .................. . .... 8 Texas ...... .. ..... . ............. G Virginia ......................... 12 West VU'ginia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

lo Ar ,. U• :3 td 10

•P n ol

~· \P re ·d ·v

'" "' '" ·h ;,, 4v yt

"' ,., til

"' ~ •·S

,. " u ~II ·S 4 t

Je

PAGE 2 NOVEMBER 1955-SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS l(ansas S Is Revived Courts Void

State Laws (Continued From Page I)

activity in Baltimore and Carroll counties. Montgomery County school officials reported that 10 Negro teachers, displaced with the closing of four sub-standard elementary schools had been reassigned-some of them ~ formerly aU-white schools.

M1ssissippi Not a single effort was made by

Negroes to enroll in white schools in Mississippi, a roundup of school opening news showed. Meanwhile steps were being taken to close the "gap" between the quality of white and Negro facilities in the dual school system. Citizens Councils were o~ganized in four additional commuruties.

Missouri School children were settling into a

second year of classwork in integrated schools without incident. "The whole subject has virtually disappeared from the newspapers," wrote SSN Missouri Correspondent Robert Lasch. Meantime, a study arising out of school integration yielded these first findings: (1) Integration can make possible a sharp reduction in the average size of elementary classes; (2) integration in a large city system can mean mixed classes for only 10 per cent of the students though the Negro population may be more than 33 per cent; (3) when optional integration takes place in high schools, as many as one-third of the Negroes eligible to transfer to a mixed school may choose to remain at their old school instead.

North Caroli.na Gov. Luther H. Hodges suggested

that North Carolinians someday may have to operate their schools on a ''local option" basis--meaning, apparently, that local districts would be free to desegregate their schools or abandon them as they wished. The plan as yet has not taken any concrete form. The Advisory Committee on Education reported to the governor that it is "pleased with the present operation of our schools and the growing acceptance of ~e . thou~ht that racial pride and raC181 mtegrtty make most probable the substantial success of voluntary racial separation in our schools."

Oklaltoma Seven more schools reported mixed

classes to bring to a total of 271 the number of Oklahoma schools which have integrated their pupils. The Oklahoma Education Association opened its doors to Negro teachers. A late count showed that 143 Negro teachers had lost their jobs; however, one former principal of a Negro school had become superintendent of a district which included a white elementary school.

South Carolina A Negro minister who was an

originator of the Clarendon County case left South Carolina after some gunplay which was ~e first reported instance of violence in the state over the school segregation issue. Meeting at Columbia, local groups began organizing the Citizens Council movement on a statewide basis.

Tennessee Federal Judge Marion S. Boyd,

ruling in a five-month-old college entrance case, held Tennessee's school segregation laws unconstitutional but upheld a state plan for gradual desegregation of th.e slate college system. The newly formed Tennessee Society to Maintain Segregation announced plans for a statewide organization and said it would cooperate with the Citizens Councils in Missis-sippi and other states.

Texas The Texas Supreme Court declared

invalid provisions of the state constitution and state school laws requiring segregation. This was the celebrated Big Spring case. A survey showed kH?tween 1 and 2 per cent of Texas' Negro scholastics are attending mixed classes in the 65 districts that have been desegregated.

Virginia Doubt was cast on the prospect for

a special session of the General As-

A New Book ,

Finds 3 'Unfinished Tasks WHITE AND NEGRO SCHOOLS

IN THE SOUTH, Truman Pierce, J ames Kincheloe, R. Edgar 'Moor~, Galen Drewry and Bennie Carnuc.bael, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Clilts, N.J ., 338 pages.

FOUR SCHOLARS, educators all, have taken a sharp look at edu

cation in the South and have, on the basis of their findings, identified three major "unfinished tasks" !acing the school systems of the region.

And they have gone further. White a.nd Negro School$ in the SOttth not only offers a wealth of statistical data on educational resources of the region, but on the basis of these data it presents the authors' conclusions on several aspects of the biracial school system and points out methods by which the job of educating the region's growing numbers can be tackled.

Subtitled "An Analysis of Biracial Education," the closely documen~ed volume is the result of an exhaustive study financed by the Kellogg Foundation and the Fund for the Ad-

Teacher Tenure (Continued from Page 1)

Montgomery County, Maryland, one supervisor has been displaced. Ten Negro teachers have been re-assigned to mixed schools along with the.ir pupils, although Negro teachers generally have been excluded, for the time kH?ing, from all-white schools.

In Kentucky, whet·e the 1,386 Negro teachers are, on the average, conceded to have higher scholastic and experience qualifications than the 19,482 white teachers, "a few'' Negro teachers are out of their jobs, according to press reports. However, the state department of education has received no official confirmation. In Kentucky's Floyd County, one of the first in the state to desegregate, though in the reverse, white students in the mining area this year are attending the formerly all-Negro school where the only Negro in the state teaching a mixed class is located.

The threat of loss of jobs also has been dangled before the eyes of Negro teachers in several Deep South states in efforts to keep them from pressing for school desegregation. The effort of the Georgia Board of Education by resolution (later rescinded) to oust all teachers who supported the NAACP or desegregation and the Alabama attempt by legislative action to accomplish the same end in the Black Belt counties are the best known examples.

S.C. CASE Similar threats reportedly have

been used in Clarendon County, South Carolina, where one Negro teacher reported her contract was not renewed because her father-in-law had signed the petition instigating the new famous court action that ultimately resulted in the May 17, 1954, Supreme Court decision.

But the displacements and firings which have occurred still are far below expectations. For example, even in Oklahoma, Negro education lead-

sembly to deal with the segregationdesegregation problem as the state stHI awaited a report from the Commission on Public Education. A sixth NAACP petition was filed in Virginia requesting integration, this one in Charlottesville. (SSN was in error last month in this space in reporting that "Norfolk Negroes denied admission to aU-white school with school board later turning over building for aU-Negro occupancy." The incident occurred in Newport News, not Norfolk, and was correctly reported elsewhere in the October issue.)

West Virginia Greenbrier County, scene last year

of a disturbance when an unsuccessful effort was made to integrate schools, decided to try again in January after a federal district court ruling. It was the first legal action of its kind in West Virginia. Meanwhile, the NAACP implied or threatened suits elsewhere in the state.

TRUMAN PIERCE Studiu South's Schools

vancement of Education. The study was directed by Dr. Truman Pierce

ers have estimated that 450 of tltc state's 1,600 Negro teachers will ultimately lose their jobs as desegregation proceeds, and in West Virginia an estimated 10 per cent of tl•e Negro teachers may be displaced, official sources reported.

Outside the region, New Mexico reported 20 of its approximatE>ly 25 Negro teachers now are instructing mixed classes, with no displacements among them. The state has a total of about 7,200 teachers, with approximate quality reported in the qualifications and salary scales of the white and Negro groups.

Similarly, Kansas has a small numoor of Negro teachers, 340 out o£ a total classroom complement of 16,889 (including pub I i c and private schools). While figures on the integration or displacement of Negro teachers are not available, some dissatisfaction with the teacher situation in Topeka, the scene of the Supreme Court case decided May 17, 1954, bas been reported in the daily press.

Beside the fear of loss o£ jobs, listed as the greatest apprehension, there were other reasons for the uncertainties surrounding Negro teachers in the 13 states responding to the SSN questionnaires.

The white directors of Negro education in Florida, Georgia and Alabama listed fear of abandonment of the public schools as the second greatest fear. In Tennessee the fear that greater professional preparation would be required ranked second, while in West Virginia it was the fear of lack of cooperation from white teachers, official sources reported. ln Florida, fear of unpleasantness and unfair treatment stemming from the attitude of white school administrators and in Oklahoma !ear that after kH?ing displaced, opportunities in other occupations would be limited were the major concerns of Negro educators.

This listing of causes of uncertainty among Negro teachers, of course, represents nothing definite. It is nothing more than the informed opinion of individual educators or school administrators, white and Negro, in the various states. Only in South Cat·olina has any study of a definite nature been made on this topic, and il in the summer of 1953.

HOWARD STUDY Conducted by Hurley H. Doddy, as

sistant professor of education, and C . Franklin Edwards, associate professor of sociology at Howard University, this study recorded the fears harbored by 150 teachers and principals in South Carolina who had returned to summer school for graduate study. Published in the 1955 Winter issue of The Joun~.aL of Negro Education, the results listed the 12 most prevalent apprehensions in the following ordPr:

(1) Demands for increased professional preparation would be greater.

(2) Fewer couples would be employed at the same schools.

(3) New ways would be intro-

from the George Peabody College at Nashville Tenn. A year's research by the four ~uthors, assisted by a broad array of scholars, educat~rs and school administrators, went mto ~e making of this book which has as lts s tated purpose "to set forth, .analyze and interpret facts concernmg the dual school systems of the South to the end that the findings may be u~eCul in efforts to deal intelligently wtth the segregation issue and ~ther pr~blems in southern education dunng the years immediately ahead."

Like its predecessor in the area of southern education, the popularly known Ashmore Report, thls most ~ecent study defines the South as mcluding 13 states: Alabama, Arkansas. Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana Mississippi, North Carolina Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tenne~, Texas and Virginia.

1952 DATA USED Also like the Ashmore Report (The

Negro and the Schools, Harry S. A:hmore, University of North Carolma

(See A NEW BOOK, Page 11)

duced to evade granting equality in employment, pay and other benefits.

(4) Great amount of job displacement would occur.

(5) Greater hostility toward Negro teachers by white school officials would develop.

(6) White students would not show t•espect.

(7) Negro teachers would not receive jobs equal to their training and experience.

(8) Despite the Supreme Court ruling, schools would remain about as before.

(9) White teachers would not cooperate.

(10) Negro teachers would be worse off after desegregation than before.

(11) Negro teachers would not know how to conduct themselves.

(12) The public schools would be abandoned.

LAWS ALTERED However, a review of news stories

on the topic of teacher tenure and status published in the daily press since September, 1954, would indicate why concern for their jobs may well be uppermost in the minds of many Negro teachers. For while states such as Oklahoma, Mississippi and Georgia do not have teacher tenure laws, efforts have been made or cons idered in the past year to alter tenure laws in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky and Virginia.

In Tennessee the last session of the General Assembly adopted an amendment to the teacher tenure law which leaves it up to local boards of education "to determine the fitness of such teacher(s) for reemployment in such vacancy on the basis of the board's evaluation of ... competence, compatibility and suitability to properly discharge the duties required . . . considered in the light of the kH?st interest of the students in the school where the vacancy exists."

The Tennessee Department of Education maintains that this amendment merely insures local jurisdiction in the matter oi teacher employment. However, a prominent Nashville attorney who has spoken publicly on segregation has recommended similar tenure law amendments as one method of getting around the touchy problem of employing Negro teachers in mixed classes in state moving toward desegregation.

North Carolina abandoned its teacher training law last year, and the Virginia Board of Education has approved the introduction of a 30-day dismissal clause in its law providing for continuing teacher contracts.

PLEDGE PROTECTION Something of the interest Negroes

have in this aspect of the segregation-desegregation question was demonstrated last month in Charlottesville, Va., at the state meeting of the NAACP where top spokesmen pledged legal support to protect the l('nure of Negro teachers in the state.

While developments relating to the

By ANNA 1\tARY l\1lJRPHY Topeka Daily Capital

TOPEKA, A three-judge federal district

panel ruled here Oct. 29, that the peka Board of Education is ing .. in good faith toward desegregation."

An "option" feature of the "" .......... -desegt·egation plan was earlier this fall by the resenting Negro parents one oi the original actions, Topeka Board of Eclucation, to the Supreme Court school

"Desegregation," ruled the "docs not mean there must be mingling of the races in all districts. It only means they may be prevented from intenningling going to school together because race."

The Topeka plan has accompiiSIIllt.~f!' the latter, the court said.

By Step No. 3 of the Topeka nu.1 .. ,;~· effectiv(' this fall, the board pupils the option of school in the district where live or continuing to attend former school.

Because of th" options, NAACP's latest suit had alleged purported plan of desegregation. not in conformity with the decree the U. S. Supreme Court."

During the hearing, circuit iud,.,..,.Walter Huxman told both lack of good faith is the only auE!Stlalt""' W(' are concerned with now, we do not consider this the final

The NAACP contended the feature, combined with the Negroes live in the districts sen.-~ ....... by the three former Negro would keep those ever being anything but schools."

The board's argument mandatory attendance was "immediate compulsory inte~alia:r:-and not "abolition of segregation." Step three achieved latter, the board said, and the upheld it.

question or teacher tenure and----.... , ...... -.. have occurred at a slow pace, they have occurred at all, the remains that this is an area of tense inter~st to Negroes in the ing profession since it is among most lucrative and respected pations open to th('m in many of the South. In Alabama, ample, wh('re Negro teachers'ave',.Oi(IJ::rl. salary in 1952 was only $2,359 in parison to the $2,541 average the white teachers, the median iru:clllr•ll:!!...:

Cor Negroes as a whole in was only $882 as compared to.....-• . -.""·· for the whites, according to the census report.

Perhaps in anticipation of •ll.li:•~•:a•.:..

on the segregated school Southern stales, beginning 1949, started on programs of ization which have about .., .. .mn .. ..., some portions or the biracial tional systems. Among the benefit from this rush to protect "separate but equal" theory by ing facilities equal in fact Negro teachers. While for Negro teachers still are white teacher averages, salary in practically all of the states been equalized at the state level, any discrimination in salary occun-ing in local supp'lenlentallOIJrthc minimum foundation now in efTect throughout region.

SALARIES EQUAL In six stales-Kentucky,

Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee. ginia, and West Virginia-wbert Negro teachers generally are qualified in terms of degrees and experience than white Negro salaries, on the averagt. equal or higher.

Just what effect the tensions by these Uncertainties rttt~\Jllll"JI'~~,'~ the status of Negro teach~ have on the quality of educatiCI' the South is not clear.

In Tennessee, at least, an quality of work" has been one an education official reported.

i,~1Court to Order Integration ~ LITTLE ROCK, Ark. He said there was no question be' ~ Bearden School District took fore the court of the law involved

1 a prominent role in October de- b~t that the problem was to detervelopments on the Arkansas school ~me what could be worked out with

~. scene when Federal District Judge m the .law for the best interests of

SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS-NOVEMBER 1955-PAGE 3

• Ill Arkansas' Bearden District

John E. Miller said he expected to all parties. order racial integration there within No date was set for a final deter-a year.

The Hoxie School District, which reopened schools on an integrated basis Oct. 24 after a harvest recess, remained in the news with a state court suit alleging administrative irregularities filed against the school

• board and others by pro-segregation forces, and a federal court suit filed by the school board against pro-segregation forces.

'.. tn its federal court suit filed at 11 · Little Rock with Judge Thomas C. ~ Trimble, the Hoxie school board

- asked for and got a temporary restrainingorder to keep the pro-segregation forces from interfering with the re-opening of schools on an integrated basis. Still pending is the heart or the suit-a request for a declaratorY judgment to the effect that the Arkansas law requiring racial segregation in schools is nullified by the Supreme Court ruling and that the school board would be subject to civil and criminal liability if it rescinded its integration ordet·.

National and state NAACP attorneys representing 24 Negro children

· filed a complaint Oct. 28 in federal .... district court at Fort Smith, Ark ..

r· atainst the board and superintendent l o£ the Van Buren Independent School

District of Crawford County, asking an end to racial segregation.

A temporary injunction was asked f!' .oending a final declaration. The r:· t:l' ~lain tiffs asked that a statutory three

udge district court be convened and : T .hat a "speedy hearing" be granted.

t.ttorneys who signed the complaint r ~ 'Were Thurgood Marshall of New York

:iity, chief counsel for the NAACP; .::: , U. Simpson Tate of Dallas, regional

~AACP attorney; D. L. Grace of Fort :1 • ;mith and Robert L. Carter, address ~: anlisted.

The civil action is styled CaroLyn t lane Abernathy, et al, v. J. J. Izzard

11 board pYesident, et at __ Latest figures show Negroes consti

ute 2.2 per cent of enrollment in Van "9uren Schools.

The suit was the first of its kind in :::

11 ~kansas since the May 17, 1954 Suu· ., preme Court decision and is the first P • NAACP court challenge of school ~' - ;egregation in Arkansas. .II!~ Other developments included: c: _ (1) The Biggers-Reyno School -~ .. District, which earlier had announced ~ t. it would begin integration Oct. 24,

1." announced it had decided to con

•' linue segregated schools this fall. r:t ~ (2) Residents of Star City in Lin-n.... oo1n County, in the plantation section ~.1 , ){ southeast Arkansas, circulated a

• petition against a proposed rally by ~e White Citizens Council of Arkan

&$- sas and council leaders cancelled the !'! meeting after the county sheriff in

formed them the town didn't want :he rally.

(3) A leader of White America, .Inc., an Arkansas organization, said

'.: )lis forces would resist racial integrar. " lion in the schools "even to the point ,. ;f destroying the public school sys-a ,em."

.. (4) The Arkansas Athletic Asso,.:iation ruled that Negroes cannot ~pete in high school athletic con.ests with white students if objections

. U'e raised by one of the participating earns.

On Oct. 4 in federal district court 1t El Dorado, Judge John E. Miller old the Bearden School District he

r" •xpected to order racial integration n the district schools within a year. The suit (Alvin J. Matthews , et al.

'· the Board of Directors of Bearden lchool District No. 53 of Ouachita :ou.nty) had been filed in 1952 seekng equalization of facilities, but the ;upreme Court decision activated a IOrtion of the suit which asked for ·acial integration.

"The court will nol sanction or •PProve any discrimination on a raial basis," Judge Miller said.

mination in the case. Bearden Supt. Tom Ford said the

distt·ict had about 600 white students and 300 Negro students.

Defense Atty. Lamar Snead of Camden told the court that both sides had met several weeks ago to attempt to solve the problem but found school facilities at Bearden were inadequate for both races.

Judge Miller said future school construction at Bearden must take into account the Suprcn.e Court ruling against school segregation.

The Bearden suit is not being sponsored by the NAACP.

HOXIE BOARD SUED On Oct. 3 at Walnut Ridge, Amis

Guthridge of Little Rock, attorney for White America and for a prosegregation group at Hoxie, filed suit in Lawrence County Chancery Court against Hoxie school officials and others, alleging several irregularities and asking the court to compel school officials to meet with his group to air grievances. The racial issue was not mentioned in the complaint.

The group represented by Guthridge bas been feuding with the board since the integration of about 25 Negroes with 1,000 white students began in the pre- harvest summer session.

Plaintiffs in the suit are Herbert Brewer, J ewel Barnett, Floyd Cole, John J ohns, Gracon Lamb and Ali McMullen. The defendants are Leslie Howell, L . L. Cochran, Howard Vance, Guy Floyd, and Leo Robert, all board members; Supt. K. E. Vance, B. B. Vance and Howard Vance. doing business as B. B. Vance & Sons; Mrs. Leslie Howell, Mrs. L. L. Cochran and Mrs. Guy Floyd, wives of board members and teachers in the Hoxie schools.

The suit char~ed that Howard Vance, as one of the owners of B. B. Vance & Sons, a lumber and building material firm, had sold materials to the district in violation of state law. The suit alleged that the district had paid $952.43 to the firm since Aug. 9, 1954, and asked the court to order a refund of that amount. Later, the suit was amended to allege the total sales were $4,181.38.

The suit also charged that the three wives of directors had been employed by the district in violation of state law.

Action in the suit is still pending.

INTERFERENCE ENJOINED On Oct. 14, Federal Judge Thomas

C. Trimble at Little Rock issued a temporary order restraining segregationists from interfering with the operation of schools at Hoxie. At a hearing Oct. 20, the hearing was postponed until Oct. 31 to permit study of whether a federal court has jurisdiction, and the restraining order was extended to that date.

The order also restrains the foes o( integration from threatening or intimidating school officials and from seeking to persuade parents from sending their children to integrated classes.

Spokesmen for groups fighting integration denied there had be~n acts or threats of violence at Hoxte and said the legal action was brought to counter the pending suit at Walnut Ridge.

The suit (Hoxie School District No. 46 of Lawrence Ccnmty, et al, v. Herbert Brewer, et al. CiviL Action No. J-918, in the U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Arka.nsa.s, Jonesboro Division) named the Hoxie school board members and Supt. K. E. Vance as plaintiffs.

Defendants are Herbert J3rev.:er, leader of the Hoxie group opposrng integration· Amis Guthridge of Little Rock, attorney for White America, Inc.; James D. Johnson of Cro~ett and Curt Copeland of Hot Sprmgs, leaders in the White Citizens Council of Arkansas, White America, the White Citizens Council, and ~e Committee Representing Segregation in the Hoxie Schools.

wee: ruftl at+ny Qen off Jc 4:5

Among Ute pro-integration forces gathered Oct. 20 for a federal court hearing on a complaint fU ed by Ifoxie school officials are (£rom the left) J~mes Sloan m of Walnut Ridge Bill Penix and Roy Penix of Jonesboro, Leslie R. Rowell of Hoxie and Edwin E. Ounnway of Little Rock. Howell is chairman of the Hoxie school board. The otl1ers are lawyers.

The suit said operation of integrated schools "was effective for several weeks with satisfactory reaction from pupils and the local community" but that on Aug. 3, the defendants began to challenge the board's action.

School officials charged in the suit that the segregationists trespassed on school property, "repeatedly threatened to set up a picket line to obstruct ingress of children to these schools, organized a boycott attempting to persuade the children's parents to withdraw them from these schools" and threatened harm to the school officials.

LOSSES, COSTS CrrED The complaint contended that the

school district had suffered a reduction in attendance that would directly cause an immediate loss in revenue of $15,000 a year to the district. And the restoralion of segregation would cost another $4,500, the officials said.

Filed with the complaint were affidavits from the superintendent of schools and Raymond Saunehes, a faculty member, and Jewel Thorn, a farmer who lives near Hoxie. Supt. Vance's complaint told of threats, and the other men reported on a mass meeting.

The complaint asked that the court first issue the temporary restraining order, then a preliminary injunction and ultimately a permanent injunction against interference or threats by the foes of integration.

JUDGMENTS REQUESTED J udge Trimble was asked to de

clare: (1) That the board has the right

and duty to refuse to obey Arkansas Jaws which contradict the laws of the United States by requiring segregation.

(2) That the board is authorized and required by the 14th Amendment to desegregate without regard to whether the Arkansas law is repealed.

(3) That the plaintiffs would be subject to civil and criminal liability if they restored segregation at Hoxie.

Johnson termed the action a "deft publicity move" by the school board's attorney. He said the defendants would attempt to claim a $500 bond posted in federal court by the plaintiffs for the "false and damaging accusations."

At the Oct. 20 hearing, W. H. Gregory of Little Rock, attorney for Guthridge and the other defendants, filed a motion for dismissal in which he said the court was with.out jurisdiction in the case.

Judge Trimble said he wasn't certain that he had jurisdiction and directed attorneys for both sides to prepare briefs on that question, exchange them with each other and file them with the court by Oct. 29. The question of jurisdiction then will be considered Oct. 31, Judge Trimble said.

ther, Roy Penix, who are law partners; Edwin E. Dunaway of Little Rock, and J ames Sloan III of Walnut Ridge.

On Oct. 4 at Little Rock, John W. Hamilton of St. Louis, editor of the White Sentinel, official organ of the National Citizens Protective Association, spoke at the meeting of the Little Rock chapter of White America.

Hamilton, who said he was proud to be a believer in white supremacy, told of riots, demonstrations and racial tensions which he listed as results of integration "up north."

"There is more racial trouble in Chicago today than in the whole South," he said.

Hamilton said be was "amazed" to learn that the Urban League at Little Rock was supported by the Community Chest. He said the Urban League was not a benevolent or charitable organization.

"The Urban League is a Negro political pressure organization out to stuff the Negroes down your throat," Hamilton told the audience of about 60 persons. He urged Little Rock citizens to "call up the Community Chest and tell them you won't give a penny" that would be passed on to the Urban League.

On Oct. 8, Dr. J . Curtis Dixon of Atlanta, Ga., vice president and executive director of the Southern Education Foundation, said at a Hot Springs meeting of the Arkansas Association of School Administrators, a group affiliated with the Arkansas Teachers Association for Negroes, that integration was not "an impossible problem."

It can be solved, he said, by "sitting down at the conference table in a spirit of goodwill and understanding.

"Integration won't be brought about in state departments of education," be said. ''It will be brought about on the local level."

WHITE AMERICA'S PLANS On Oct. 15, Amis Guthridge, of

Little Rock, an attorney for White America, Inc., said his group would take the following steps to maintain segregation:

(1) Seek passage of a state law modeled on an Alabama act which sets up several ways in which local school districts can "assign" white and Negroes to separate schools.

(2) Fight for election of public officials "in cluding a governor and legislators" who will maintain segregation.

(3) Seek legislation to withdraw s tate financial aid from Henderson State Teachers College, Arkansas Tech and Arkansas State College because they admitted Negroes to classes.

(4) If all else fails, seek to abolish the public school system.

board members who would "reduce the millage rates to nothing." He said this would destroy the "public status" of the schools, permitting the buildings to be rented, leased or sold to private corporations to operate. Guthridge said existing state laws would permit such a move.

ATHLETIC POLICY In a policy statement adopted Oct.

12, the executive committee of the Arkansas Athletic Association said that Negroes may participate in high school athletics with white students only through mutual agreement of the participating schools. All 457 white high schools in the state are members of the AAA.

The committee ruled that a school canceling a game during the present school year with a team that includes Negroes will not have to forfeit the game or pay the minimum guarantee.

On Oct. 14, the Biggers-Reyno school board in Randolph County in northeast Arkansas announced it had decided to continue segregated schools this fall. The board had announced earlier that racial integration would begin when schools opened Oct. 24.

Glen Cox, a board member, said the action was taken after a mother wrote the board to ask that integration be on a voluntary basis. Cox said White America, Inc., had promised to pay $150 toward the expenses of two Negro students who will be sent to schools at Pocahontas and Jonesboro. One of the Negro students is in grade school, the other in high school.

On Sept. 29, the Hoxie school board failed to appear for a meeting which had been requested in a petition signed by 50 electors and citing an Arkansas law which requires school boards to meet when so petitioned.

Hoxie reopened its racially integrated schools Oct. 24 without incident but with a high rate of absenteeism. Supt. K. E. Vance estimated about half of the high school and junior high students were present. A smaller percentage of elementary students were in the classrooms, he said.

Vance said the high school and junior high attendance was about normal for this time of year because many pupils still are picking cotton. But he said integration was a factor in the absenteeism in all grades. He said it was possible some parents of elementary pupils kept their children at home "just to see what is going to happen."

Most of the Negro pupils were on hand for the re-opening after the harvest recess. Generally, they sat on one side of the classroom apart from the white students and stayed together during recesses.

Normal enrollment is about 25 Negroes and about 1,000 whites.

INTEGRATION SUGGESTIONS On Sept. 29, five ways of integrat

ing public schools were suggested at an organizational meeting of the Hot Springs school board's Advisory Committee on Integration.

Dr. Imon Bruce, superinte.ndent of schools, told the committee of 28 members, including five Negroes, that under the Supreme Court ruling "we are obliged to plan integration." He suggested five methods:

(1) Creation of an auto mechanics course open to Negroes and whites on a voluntary basis.

(2) Opening some senior high school courses to Negroes at the new all-white school in cases where similar courses are not offered at the Negro school.

(3) Integration on the high school level but allowing students to remain at their present schools if they so desire.

(4) Start integration at the first grade level. Assisting Gregory as attorney for

the defendants was M. V. Moody of Little Rock. Attorneys for the plaintiffs include Bill Penix and his fa-

Guthridge said the Latter could be accomplished by electing school

(5) Integrate at the elementary level,

,,., puUMI'!ft!nn

l

' I I I s I t )

e r )

::1 .. ;I c: n e f.

'" q fn iv :S I< lr st •h :>I e 0 :.I u ~. tn

Ia Ar t. U• :3 td \0

•P rs ol ,, IP re -d -y

'" sl Ill

'" nf

~v VI ft• )~ .a ~· c; ;S

"' h ,, , .. J@ . ... le

r• us )I ch >II s 4

d :S Je

~

PAGE 4-NOVEMBER 1955-SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS

Florida Supreme Court Bans School Segregation As a 'Legal Principle'

Supreme Court mandate and should be ended immediately. Justice Elwyn Thomas joined in this dissent.

MIAMI, Fla. THE Florida Supreme Court last month, in a case which has been

before it since 1949, knocked out segregation as a legal principle.

The state's highest court, by a vote of 5-2, held that "our inescapable duty" is to abide by the desegregation ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Conflicting state laws, such as the constitutional provision against the mingling of races in the schools, have no force and effect, and stat~ agencies have no authority to bar a student merely on grounds of color, the court said.

But, the court added, the federal ruling does not require "a clear legal duty" to admit Negro students to schools "at any particular time in the future."

"On the contrary, the clear import of the federal ruling and indeed its express direction is that the state courts shall follow equitable principles in the determination of the precise time in any given jurisdiction when members of the Negro race shall be admitted to white schools.

LAWS NULLIFIED "The Supreme Court of the United

States said in that decision that these cases call for the exercise of the traditional powers of an equity court with particular reference to its faculty of adjusting and reconciling public and private needs and the practical flexibility in shaping its remedies."

School officials, after a study of the decision, said its net result is to nullify the state segregation laws. But it also allows time for integration by orderly procedure,

Biracial committees are at work in about a third of Florida's counties to survey the situation and make recommendations.

- - ~' ._·_ -===-:::- ~

- .:~·· ~- \!:::: ~ 11\~: ~ ~

LEGAL ACTION

The Florida Supreme Court opinion involved the case of Virgil Hawkins, 46-year-old Negro publicist for Bethune Cookman College, who bas been fighting for six years for admission to the law school of the University of Florida.

The appeal was denied by the Florida Supreme Court. The case went to the U. S. Supreme Court, and was remanded to the Florida court for a ruling in keeping with the federal court's integration decision.

The court held that the board of control, which administers the state's system of higher education, "cannot lawfully refuse to admit (Hawkins) to the University of Florida Law School merely because he is a Negro."

It added that admission of Hawkins to the university presents ''grave and serious problems affecting the welfare of all students and the institutions themselves, and will require numerous readjustments and changes at the institutions of higher learning.'' These changes, the state board of control said, "cannot be made satisfactorily overnight."

NAME COMMISSIONER To see that the rights of Hawkins

are protected and the situation solved " without public mischief," the Supreme Court appointed a commissioner to take testimony from Hawkins and the university "and such witnesses as they may produce to show whether or not the university law school is ready at this time to accept Negro students.''

Circuit Judge John A. H . Murphree of Gainesville, where UF is located, was designated for this duty. He was instructed to "conduct all necessary hearings and file a transcript without recommendations or findings of fact." His report must be completed in four months.

The court specifically said that Judge Murphree's investigation "must be limited in scope to the conditions that may prevail and that may lawfully be taken into account in re-

spect to the college of law at the University of Florida.''

On the basis of Judge Murphree's findings, the Supreme Court will determine when Hawkins shall be admitted to the university.

"We adopt this procedure pursuant to the directive of tM implementation decision to the effect that we retain jurisdiction during this period of transition so that we may properly take into account the 'public interest' as well as the 'personal interest' of (Hawkins) in the elimination of such obstacles as otherwise might impede the systematic and effective transition to the accomplishment of the result ordered by the Supreme Court of the United States."

PRINCIPLE DISCUSSED While the court majority limited

the scope of the decision, two supplementary opinions dealt with the whole question of segregation. One held the court did not go far enough, the other questioned integration on principle.

Justice Glenn C. Terrell, senior member of the court, in a special concurring opinion, agreed with the majority, but was critical of the federal ruling.

"Segregation is not a new philosophy generated by the states that practice il," he wrote.

"When God created man He allotted each race to his own continent according to color-Europe to the white man, Asia to the yellow man, Africa to the black man, and America to the red man.

"But we are now advised God was in error and must be reversed.''

Declaring the "separate but equal" doctrine has resulted in huge sums being spent for school facilities ~or white and Negro students, Justice Terrell continued:

"The dove and the quail, the turkey and the turkey buzzard, chicken and guinea, it matters not where they are found, are segregated. Place the horse, the cow, the sheep, the goat and the pig in the same pasture and they instinctively segregate.

"The fish in the sea segregate in schools of their kind.

'LAW FOLLOWS NECESSITY' "In a democracy, law does not pre

side, but follows a felt necessity or public demand for it. The genius of the people is as resourceful in devising means to evade a law they are not in sympathy with as they are to enforce one they approve.

"States with segregated schools have them from a deep-seated conviction. They are as loyal to that conviction as to any other philosophy to which they are devoted.

"They are as honest and law abid- . ing as the people of any state where integrated schools are the rule. Convinced of the justice of their position, they will not readily renounce it if they are required to forfeit abruptly their conviction.

"There is no agitation for a change; the whites and Negroes are, as a rule, satisfied with what they have, and have made remarkable progress with it.

'RACES UNPREPARED' Justice Terrell said the two races

at-e "totally unprepared in mind and attitude" for non-segregated schools.

"The degree of one's culture and manners may resolve these differentials, but they will not resolve under the impact of court decrees or statutes. Closing cultural gaps is a long, tedious process and one for the home, the school and the church rather than for the courts and legislature."

Stating that segregation was a "natural" process, as evidenced in churches, residential areas and other aspects, the senior Supreme Court justice wrote:

"Are we to build now at a cost of millions to the taxpayers new schools so that Negroes and whites can go to school together?"

Another dissent was written by Justice H. L. Sebring, who has recently retired to become dean of the Stetson University Law School.

Justice Sebring held that segregation is unlawful by United States

The Sebring opinion said: "The only federal judicial guide that we have as to what the states must do to provide 'equal educational opportunities' to their citizens within the purview of the 14th Amendment is laid down in Brown v. the Board of Education, supra (the desegregation ruling), which expressly holds that in the field of education the doctrine of separate but equal has no place.

"That it is our judicial duty to give effect to this new pronouncement cannot be seriously questioned.

"Therefore, whatever may be our personal views and desires in respect to this matter, we have the binding obligation, imposed by our oath of office, to apply to the issue at hand the federal constitution as presently interpreted by the Supreme Court of the United States, and give force and effect to this new principle that the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place in the field of public education in Florida, even though our own constitution and statutes contain provisions that require in our schools the separation of the races.''

Comment on the Supreme Court's opinion and its meaning came from varied sources. Chairman Fred Kent, of the state board o! control, technically the defendant in Hawkins' suit which resulted in the ruling, said:

"No action will be taken on any decision or applications now pending before it (board of control) until the Supreme Court bas considered Judge Murphree's findings and given the board the benefit of its decision on integration.

"The board of control will comply carefully with all the provisions of the decision and will cooperate to the fullest with Judge Murphree and obtain for and present to him all the facts in its possession, which he might consider helpful in carrying out the wishes of the Supreme Court.''

Chief Justice E. Harris Drew of the Florida Supreme Court said that "it could not be concluded" from the Hawkins opinion tJ1at all petitions by Negroes for admission to the University of Florida, or to the public schools, or any other state supported institutions, would be handled in the same manner.

EACH CASE DIFFERENT "Each case will have a different

set of facts and must be handled individually on the basis of those facts and conditions," be said.

Thomas D. Bailey, state superintendent of schools, said the opinion, in his view, was consistent with the U. S. Supreme Court decision, as well as with the official stand taken by Florida's Atty. Gen. Richard W. Ervin in the "friend of the court" brief filed in the federal proceedings.

"Any implementation of the U. S. Supreme Court decree is dependent on local conditions pertaining to social and educational factors," Bailey declared.

"The Florida Supreme Court decision, which stresses equality as a factor in arriving at the decision, established a pattern which may preserve the orderly functioning of our public school system."

Atty. Gen. Ervin said he considered the court opinion "a very wise and helpful one in that it allows time for additional fact-finding and study to take place."

"U the solution to this whole problem of racial integration of the public schools is to be found, I believe the answer will be found in study.

''We have constantly maintained that the problem cannot be solved by precipitative coercive action in any direction. We argued this contention to the U. S. Supreme Court and that court in its decree last May recog-

SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS cou s.,tho" s,hool N.., ;, tho ofll<lol P'bllootlo• of tho S~'lho" Ed,,.,;,, ~

R -•· Service en ob·1ective feet-finding egency estebl11hed by southern eporllng • • . f 'd'

d'tors and educetors with the e1m o prov1 1ng eccurate, newspeper e I bl' rr· . I d . unbiased informetion to school edministrators •. ~u 1c o cc1a s an Interested

I 't' developments in education em1ng from the U. S. Supreme ay Cl 11ens on , . . Court opinion of Mey 17, 1954 declaring segregat1on 1n the publ1c .schools unconstitutional. SERS is not an edvocete, is neither pro·segregat1on nor anti-segregation, but simply reports the feels es it finds them, stele by state.

Published et 1109 19th Ave., S., Nathville, Tenn.

OFFICERS Virginius Debney . . . . . · · • · · • · Thomes R. Wering . .... · · · · • ·

......... Chairman . . . . . . . Vice·Cheirman

. Executive Director Don Shoemaker . . . . · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Frenk Ahlgren, Editor, Memphis

Commerciel Appeal, Memphis, Tenn.

Gordon Blackwell, Director, Institute for Reseerch in Social Science, University of N.C.

Harvie Brenscomb, Chancellor, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Virginius Debney, Editor, Ric:hmond Times-Dispetch, Richmond, Ve.

Colemen A. Herwell, Editor, Nashville Tennessean, Nashville, Tenn.

Henry H. Hill, President, George Peabody College, Neshville, Tenn.

Charles S. Johnson, President, fis~ University, Neshville, Tenn.

C. A. McKnight, Editor, Charlotte Observer, Cherlotte, N.C.

Charle1 Moss, ~ecutive Editor, Neshville Benner, Neshville, Tenn.

Don Shoemaker, Exec:. Director Sou. Education Reportin9 Service

Thomes R. Waring, Editor, Cheri••· ton News & Courier, Charleston, s. c.

Henry I. Willett, Superintendent of Schools, Richmond, Ve.

P. B. Young Sr., Publisher, Norfolk Journal & Guide, Norfolk, Va.

CORRESPONDENTS

ALABAMA Williem H. McDoneld, Editorial Writer, Montgomery Advertiser

ARKANSAS Thomas D. Devis, Asst. City Editor, Arkensas Gaulle

DELAWARE William P. Frenk, Steff Writer, Wilmington News

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Jeanne Rogers, Educetion Writer. Weshington Post & Times Herald

FLORIDA Bert Collier, Staff Writer, Miami Herald

GEORGIA Joseph B. Perham, Editor, The Macon News

KENTUCKY Weldon James, Editorial Writer, Loui1ville Courier.Journal

LOUISIANA Merio Fellom, Politicel Reporter, New Orleans Item

MARYLAND Ed9ar L. Jones, Editorial W riter, Baltimore Evening Sun

MISSISSIPPI Kenneth Toler, Mississippi Bureau, Memphis Commerciei-Appeel

MISSOURI Robert Lesch, Editoriel Writer, St. Louis Post-Dispetch

NORTH CAROLINA Jey Jenkins, Releigh Bureau Chief, Cherlotte Observer

OKLAHOMA Leonard Jeckson, Staff Writer, Oklehoma City Oklehoman-Timll

SOUTH CAROLINA W. D. Workmen Jr., Special Cor· respondent, Columbie, S. C.

TENNESSEE Jemes Elliott, Staff Writer, Nash· ville Banner

Wellece Westfeldt, Staff Writer, Nashville Tennessean

TEXAS Richerd M. Morehead, Austin Bu· reau, Delles News

VIRGINIA Overton Jones, Editorial Writer, Richmond Times.Dispetch

WEST VIRGINIA Frenk A. Knight, Editor, Charltl· ton Gazette

MAIL ADDRESS P.O. Box b I Sb, Acklen Stetion, Nashville 5, Tenn.

nized the validity o{ this position in refusing to set a mandatory deadline.

"The decision of the Florida Supreme Court is consistent with that philosophy."

Virgil Hawkins, whose long court fight was ended by the decision, said, "I am not a test case. 1 want to be a lawyer. I've wanted to be a lawyer aU my life."

From Hawkins' attorney, Horace E. Hill, came word that he "wanted to give judicious study" to the decision "in the light of precedent set by the U. S. Supreme Court.''

There was little newspaper comment on the ruling.

The Miami Daity News editorialized that "the decision undoubtedly will have the effect of delaying integ~·ation in any Florida school from six months to a year or more.

"The fact is the attitude of the federal courts, beginning with the district courts, is ultimately going to be more to the point here in Florida and elsewhere.

"The court itseli, recognizing the probable question of jurisdiction during the transition period before any actual integration, held it was the province of the state courts to permit integration only after it can be shown that no harm to the public will result.

"That may be the very question that will eventually be forced into the federal courts-here in Florida and elsewhere."

While a score or more of have been filed with local boards for admission of Negro dren to white schools, a large her requesting continued ""•"""natllltl were presented to the ty board.

They were placed on the desk Chairman A. Franklin Green and mained unopened until the the meeting when Green read a ter from the Citizens Council Pinellas asking that the petitions returned in a month.

Green handed the unopened die to Supt. Floyd Christian instructions to return them in cordance with the request.

"They can have them back now so far as I am Christian said.

Pinellas officials have they intend to obey the Court mandate and have a hi,.,a&l .:"

committee working on the That program was praised as cellent" by Dr. George Mitchell. ecutive secretary of the Souther. Regional Council.

In the celebrated Platt case in County, the Circuit Court ruled

(Sec FLORIDA, Next page)

---~--------~

""' ~IICounty In West Virginia ...,.~ Will Desegregate Again

CHARLESTON, W.Va. 0 th d h \ • R ACIAL S E GREG AT I 0 N in n e ay e announced his plan ~ for ~cDowell, Mingo and Logan

:.. Greenbrier County, scene of counties, Logan said representatives ~ ... 'West ViJ·ginia's major incident of of ~e Mercer County Boor·d of Edu-.. 1 1954, started a slow walk to oblivion cation had conferred on a settlement

Oct. 12. of an injunction suit against them. The board of education made it a Nutter did not divulge the results

casualty of the times in unanimously of the conference, but he said he had • submitting to a recommendation in turned "thumbs down" on the plan

, • Cederal district court to desegregate offered by the Mercer School Supt. ~- the public schools in two steps. W. R. Cook and Joseph Sanders, a t-

~ With the beginning of the second torney for the board. semester on Jan. 18, 1956, Greenbrier The NAACP leader stated that he

, I.. schools will be open to all children in told Cook and Sande1·s what would their districts, regardless of race. be ~tisfactory as a means of inte-

• 1

• Next fall, desegregation will become g1·ahng Negro and white children in ~ • all-encompassin.g. Mercer County, and they went back I),,. ed t p. • Segregat schools were frowned o rmceton to confer with the board. -... , ::.upon by Federal Judge Ben Moore of The NAACP filed a suit Sept. 27 in

• ',Charleston in a special term of court federal . court requesting that Judge ~\,iat the Greenbrier County seat, Lew- Moore ISSUe a permanent injunction ~It, isburg-a staid old community with restraining the Mercer board from :: • strong southern sympathies situated continuing segregation. Cook has

: near the Virginia border. previously said his board wanted to integrate next year when a school building program is completed. JNFOR~fAL STATEMENT

: 1

Judge Moore, in an informal e·..,. statement of views at the end of a ~

1 three-day hearing, spelled out a plan

1 for ending aJleged disc1·imination against Greenbrier County's 400-odd Mcgro school children.

The action, in which an iniunction • ~Nas sought against the board of edu-

cation, was brought by the .Nauonal Association for the Advancement of Colored People to hasten integration

9 1.,. in the county schools. ::w- The NAACP wanted an immediate

change. The majority of the board • • wanted to wait until next year. ':" -.· Judge Moore took the position that

';egregation could be brought to an ~nd either by injunction or by agree

•• ic.c.~nent among parties to the sult. As for ~~ ! C !lis injunction power, he declared,

'Government by injunction is one of .he worst of aJl evils."

'fi •r Such a power should be used sparngly, he continued, and as an alter

:.; utive a meeting of minds on a less .. ;evere course could achieve the same

-esults. Judge Moore was critical of the

..d ~-•IJreenbrier board for not starting de;egregation this term. He said the nembers allowed a "public demonltralion a year ago to intimidate

~- .hem ... " i:r. He recognized the fact that if inte

gration were started immediately. :..w) disruption in school curricula would ~ result. But he said he saw nothing

wrong with starting desegregation on a voluntary basis next semester.

He proposed integration in January r on a "first-eome-first-served" basis, ~bserving that some schools in

reenbrier are crowded. An over~~· he said, could be held on a

, , 1 l"ouUng list.

INJUNCTION DENIED :: .. T. G. Nutter1 head of the NAACP in

West Virginia, was no~ pleased with ~ this proposal when it was first pro-

pounded and asked for an injunction. ~ "!o this the judge replied: "I'm not go-1 : ,...1ng to issue an injunction unless I

think it's necessary." •j The board quickly went into an ex

a: .,..-ecutive session and in fou r minutes ~> "" returned to the courtroom to an:· nounce through Supt. D. D. Harrah

that it would comply "both in the let-:.., t.er and the spirit of the rccommenda-.. tion."

Five days after the hearing, firs t in West Virginia on the integration question, Sheldon E. Haynes of Lewisburg, lawyer who handled the

1 board's case, said public sentiment : regarding the outcome of the pro

ceeding was "very good." Apparently encouraged by this

turn of events in Greenbrie1· County. II ,Nutter announced Oct. 18 that the

NAACP would press its fight for ra~ cia! integration by sending letters to

t: . three counties which still have segre-1'1 gated systems.

NEW SUITS THREATENED . He said he had started preparing ~quiries to be sent to the superin

tendents in McDowell, Mingo and Logan counties relative to the progress they have made towa1·d integration. U none has been made, Nutter added, suits in federal district court similar to the one in Greenbrier might follow.

A 10-minute board meeting in Raleigh County on Oct. 20, open to the public but attended by fewer than half a dozen outsiders, b•·ought ap~rov~ of a program to begin integration m the first three grades with the opening of the 1956-57 term.

From T. G. Nutter of Charleston. state president of the NAACP came the immediate observation: .:That's not anything."

He said he would insist on total integration by this J anuary and that his group plans to file suit in federal court to restrain the Raleigh board from continuing to segregate Negro and white pupils in public classrooms. He also referred to Judge Ben Moore's recommendation in Greenbrier County that integration be started with the end of the cu1·rent semester on Jan. 18 .

PROBLEMS DIFFERENT While the Greenbrier board voted

to accept Judge Moore's recommendation, A. P. Leeber of the Raleigh County school group noted that the problem was "differen~" in his area because of a larger Negro population. President Dale Covey of the Raleigh board asserted, "That's about all we can do."

The NAACP was not represented at the Raleigh meeting. George White, president of the Raleigh branch, said tha~ a committee had planned to attend, but that his illness prevented it.

The Raleigh board ol"iginally intended to integrate eight schools in seven scattered communities beginning with the current school term, but abandoned the program when residents protested that such a move would be discriminative against their towns.

Jn Chn.-lcston, Virgil L . Flinn, superintendent of the state's largest (Kanawha County) school system, announced on Oct. 7 that there have been "no incidents or demonstrations" since desegregation was started Sept. 6.

Negro and white students in the first, second and seventh grades were integrated this term, and the school board hopes to complete desegregation in all grades by September, 1956.

Early this month the Charles ton chapter of the NAACP, at its first fall meeting, expressed a desire to stimulate the employment of Negroes in Kanawha County plants.

"We are terribly disturbed about the employment situation as far as Negroes are concerned," Willard L. Brown, president. of the organization. said. "We should try to get employment in general for Negroes throughout the county."

JUDGE BEN MOORE Suggestion Accepted

There was considerable comment by West Virginia newspapers following the Greenbrier hearing before Judge Moore. The Charleston Gaze!te, the state's largest newspaper, sa1d:

"West Virginia can well feel proud of the outcome o! the state's first school integration hearing . . . not only because of the judicious and common-sense manner in which the court proceeding was conducted, but also for the general acceptance it has received ... "

The West Virginia Board of Control has begun a study of the industrial school system leading toward integration at a future but unspecified date.

Board President James M. Donohoe said at mid-month that the board's aim is to integrate the Negro and white girls now separately housed in two schools. Similar plans for integration of the boys' industrial schools also are under consideration.

He stated that the white schools presently are overcrowded, while the Negro schools have an abundance of beds. By desegregating, Donohoe says the facilities could be utilized more efficiently.

The board's integration plan was kept in mind in preparing budgets for the schools which will be subrnitt~ to the state's budget-fixing body, the Board of Public Works, in December.

,, ~ ':"

iN THE : COLLEGES ;:\

West Virginia's colleges, in the meantime, are experiencing one of the greatest student enrollments in history. College officials attribute the increase to the return of Korean War vetet·ans entering under the G. I. Bill of Rights.

A news service poll brought little discussion of the integration issue, but Dr. William J. L. Wallace, president of West Virginia State College, a previously all-Negro school until the summer of 1954, said there is "growing acceptance of the institution by the citizens of Kanawha County (where it is located.) Integration ... has been a contributing factor."

Florida (Continued From Page 4)

the five Platt children, dismissed on charges that they were of Negro descent, are entitled to attend any white school in Florida.

The children were dropped from the rolls of the Mount Dora school at the insistence of Sheriff Will.is V. McCall.

Allen Platt, a fruit picker who came from South Carolina, insisted h.is children were part Cherokee Indian and had no Negro blood. He appealed to Florida's Gov. LeRoy Collins and

SOUTHERN SCHOOL NEWS-NOVEMBER 1955-PAGE 5

'Shortco~nings' of D. C . Systein Arouse Parents

WASHINGTON, D. C.

I N THE LAST MONTH, Washington parents have adopted a get

tough policy toward the shortcomings of the public school system.

Forgetting self-interest complaints of the past, Negro and white parent groups united in their demands to District commissioners and the board of education for immediate remedy of overcrowded classrooms and a teacher shortage.

During the hearing on the subject, a white mother told the school board: "Integration is going smoothly at our school where one-fifth of the pupils are Negro. But the present crowded conditions can jeopardize the situation by breeding dissension in the community."

The speaker lives in Southeast Washington, a section of the city where residents were reluctant to accept integration because of longrunning racial conflicts over housing and recreation issues.

Other parent spokesmen repeatedly said they wanted proper school facilities for all children. They demanded higher educational standards for all.

Two days before the new term opened, principals ol 4.{) grade schools were notified they would be short from one to two teachers. This meant that two or more grades were combined in one classroom. Parents became aroused.

MISCALCULATIONS The teacher shortage resulted from

admin..istrative miscalculations and lack of funds. Grade school administrators counted on picking up 50 teacher salaries from secondary schools where enrollment was expected to drop. Junior and senior high officials, however, already had hired a full complement of teachers.

For an unexplained reason, officials !ailed to get together in their planning. Some school officials claimed administrative channels had become clogged since the reorganization ol top level staff under integration. Others said there was a "lack of direction" f rom Supt. Hobart M. Corning.

The board of education last month refused to let a fraternity, founded by Negroes, conduct an essay contest in Washington high schools on the theme: "Desegregation, A Way Station; Integration, Our Destination."

In recommending the denial, Corning said the subject of the essay is "too advanced and philosophic."

James Carr, spokesman for the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., told board members that Washington is the only area in which the or~anization's request had been turned down.

"Alabama, Georgia, Florida and even Mississippi have not denied high school students the ril!ht to participate," Carr said. He added that the national contest has been endorsed by the National Education Association.

NEGRO M'DffiERS OBJECT Two Negro board members, West

A. Hamilton, a member of the fraternity, and Mrs. Margaret J. Butcher, whose father was a founder, objected to the denial.

Mrs. Butcher said: "II the school board is so timid it won't let students discuss its own positive action on integration, there's something wrong with the board." Hamilton said the subiect no longer is controversial.

Board member Robert R Faulkner said, "It's a one-sided subject." Mrs.

the Federal Bureau of Investigation for the protection of his rights.

Judge T1·uman G. Futch approved Platt's petition for mandamus after examining birth records and other family documents.

Sheriff McCall termed Judge Futch's ruling "disgraceful."

"In my book they're still mulattoes," McCall said. "I will continue to enforce the laws laid down by the state of Florida and let tl1em mandamus me in every case."

P. B. Howell Jr., attorney for the school board, said he will appeal the decision to the Supreme Court.

Butcher replied, "Only in the minds o! people who make it so."

Mrs. Manson Pettit, new board member from Southeast Washington said: ,

"I don' t feel the topic is pertinent and timely in the District. We've not reached a way station, we've gone beyond it. rd hate to sec us lose ground. I don't feel the subject is too deep. But there still is a great deal of tension in the area in which I reside. I have a feeling we have a small geyser. It's just bubbling but it could erupt. rm not being tfuud."

Mrs. Butcher said, "The reason we have potential geysers is that few youngsters and oldsters know what democracy means."

ESSAY REQUEST DENIED Comlng said, "Our feeling is we've

been so busily engaged doing things along this line, it is better to be doing than talking."

The school board by a 5 to 2 vote denied the fraternity's request.

A Georgetown University professor c1·eated a stir in the Washington area last month by his published statements on the Negro and the Supreme Court decision on school segregation.

According to a news account in the Arlington (Va.) Sun, Prof. Charles C. Tansill in a talk before the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties in Arlin~Iton County described the Negro as a "moron" and said Negroes have contributed nothing significant to Western culture.

Tansill later told The Washhtgton Post and Times Herald he had not used the word "moron" during the talk. Many of the opinions he expressed, Tansill said, were not his own.

"All I did was read .from books," he added.

'ACCO~fPLISHED NOTHING' In an exclusive interview published

Oct. 18 in the Washington Daily News Tansill was quoted as saying: "The Negro race has contributed nothing-ever-they've been in contact with the whites for 6 ,000 years and they've accomplished nothing. Nothing."

The News said Tansill told the A:rlington meeting that school integration would make morons of us alland emphasized the "menace of the Supreme Court to American liberties."

Following publication of the News interview, the Rev. Edmund B. Bunn, president of GeorgetoWJI University, "publicly disavowed" Tansill's remarks and promised to take "proper action" in his case.

Father Bunn told The Post he had written identical letters to three Arlinsrton residents who protested Tansill's talk. They read in part: