Otto Neurath’s War Economics

Transcript of Otto Neurath’s War Economics

XIII Convegno AISPE “Gli economisti e la guerra”

11-13 dicembre 2014 Università di Pisa

Monika Poettinger

Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, Milano

Otto Neurath’s War Economics

[Otto Neurath, Modern Man in the Making, London, Secker and Warburg, 1939, p. 87]

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

2

INTRODUCTION

The Viennese Otto Neurath (1882-1945)1, once stigmatized as a volcanic revolutionary, poor in theory as

rich in reforming enthusiasm, has only recently been rediscovered as an economist and his economic

writings have been republished and partially translated in English2. This paper analyzes the early years of

Otto Neurath’s scientific activity, at the beginning of the twentieth century, when particular attention was

given by him to war economics.

Otto Neurath excluded any kind of ethical prejudice from restricting economic analysis. Acquiring methods

as war and smuggling should, in his view, be studied exactly as market exchange and production. “That

pillage – he wrote – is prohibited by law, should not impede economists from studying it. Why should the

consequences of trade and domestic manufacture be worth to be analyzed, while the effects of smuggling

are ignored? In consequence of such considerations war has been vastly ignored by economists as a form of

acquisition (…)” 3.

Far away from any interventionist stance, Neurath considered the Balkan wars and WWI as an

extraordinary occasion to gather information4 about the emerging of barter trade, even at international

level5, the centralized administration of production, the controlled distribution of consumption goods and

the destabilizing or even vanishing of financial systems. His extraordinary efforts in this field were

recognized not only with a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and an official commendation

from the Austrian government, but also with the appointment as director of the Museum of War Economy

in Leipzig in 19166.

Above all, studying a war economy in its development meant, for Neurath, the possibility to demonstrate

that a certain grade of administrative control over the economy, based on a general system of in-kind

1 A complete biography of Otto Neurath is to be found in: Enza L. Vaccaro, Vite da naufraghi. Otto Neurath nel suo

contesto, Tesi di Dottorato in metodologia delle scienze sociali – ciclo XV – Università La Sapienza Roma; and: Nancy Cartwright, Jordi Cat, Lola Fleck, Thomas E. Uebel, Otto Neurath: Philosophy Between Science and Politics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008. The most recent publication on Otto Neurath is: Günther Sandner, Otto Neurath: Eine politische Biographie, Vienna, Paul Zsolnay Verlag, 2014. 2 Rudolf Haller and Ulf Höfer (eds.), Otto Neurath. Gesammelte ökonomische, soziologische und sozialpolitische

Schriften, Wien, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1998; Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath. Economic Writings: Selections 1904-1945, Dordrect, Springer, 2006. 3 Otto Neurath, Das Begriffsgebäude der Wirtschaftslehre und seine Grundlagen, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte

Staatswissenschaft“, vol. 73, n. 4., 1917, p.493. 4 Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschatliches Archiv“, 1, 1, 1913, p.23.

5 See: Otto Neurath, Grundsätzliches über den Kompensationsverkehr im internationalen Warenhandel,

„Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 13, 2, 1918, pp.23-35. 6 Nancy Cartwright, Jordi Cat, Lola Fleck, Thomas E. Uebel, Otto Neurath: Philosophy Between Science and Politics,

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 19-21.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

3

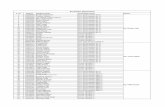

calculations, could prevent what he considered the worst trait of market economies: economic crises. An

isotype in particular, of his volume of 1939, bears testimony of such stance. The image illustrates a statistic

on coal production in the United States between 1914 and 1936, underlining how in 1917, a year of war,

production steadily remained on its maximum capacity, showing no sign of seasonal or cyclical fluctuation.

As early as 1913, in his essay: Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehre7, Neurath went a step further: “The

present underemployment of existing forces, that is typical of our Ordnung, incites to war: it is necessary,

for example, to defend oneself from foreign wares and foreign laborers or oblige others to buy our wares

or accept our workers, and all of this because it is not spontaneous to enter in cooperative relations

between states; furthermore it is easy to alleviate the costs of war thanks to reparations; and lastly because

at times war frees productive forces that would otherwise be bound. The uneconomic construction of our

Lebensordnung is the cause why at present war causes lesser evils than in a more economical

Lebensordnung the case would be” 8.

To eradicate war, in Neurath’s view, mankind had only two alternatives. The first would have been to

render it uneconomical. A second opportunity to foster peace, obviously, would have been to abandon the

present inefficient Lebensordnung for a more effective one. To decide, though, which Lebensordnung to

implement in reality was not the task of an economist. Neurath continued so, instead, to offer to the

attention of politicians economic organizational alternatives to market economy, all the while steadily

collecting statistical data and transforming it in easily understandable isotypes, in order to enable the

largest possible strata of population to decide about their future.

7 Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913.

8 Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p.500.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

4

WAR ECONOMICS AS A NEW FIELD OF STUDY

“The highest union of individuals under the rule of law which is achieved at present is that of the state and the nation; the highest

imaginable is that of the whole of mankind” (Friedrich List)9

Otto Neurath has been reevaluated in the 1980s as the empiricist philosopher at the heart of the first

Vienna Circle and for his contribution to epistemology10, but he remains largely ignored as an economist,

particularly by historians of economic thought11. Merit of Robert Haller and Thomas E. Uebel to have

republished Neurath’s economic writings, even translating a selection of them in English12. A complete and

critical appraisal, though, of the role of Neurath in the history of economic ideas is still lacking.

One of the reasons for this misjudgment might have been the negative estimation of Neurath’s economic

writings felled by contemporaries13. The holistic approach of Neurath, trying to unify economics long before

his efforts to unify the whole of science, could not be welcomed in an historical moment when taking side

in favor of one of the leading schools of thought was essential in progressing in one’s academic career.

Neurath’s attempt to redefine the content, the scope and the language of economics amidst the most

controversial debates raging between Berlin and Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century brought

many a mockery and severe critic to his writings. Political coloring and his participation to the Munich

Soviet republic in 1919 also played a part in the rejection of his ideas. Certainly the Bavarian experience

ended his short-lived academic career as professor of economics at Heidelberg, where he had obtained his

habilitation in 1817, but never taught.

9 The quotation from List’s Introduction to his “Nationales System der politischen Ökonomie” was put by Neurath on

top of his article on War Economics published in 1910. Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.153. 10

The most recent account on this philosophical school is: Alan Richardson and Thomas Uebel (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Logical Empiricism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007. Thomas Uebel has been throughout the decisive driving force behind the rediscovering of the Vienna Circle and also the republication of Otto Neurath’s work. The manifold volumes he edited are extensively quoted in the following. 11

See: Thomas E. Uebel, Neurath’s Economics in Critical Context, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.1-108. 12

Rudolf Haller (ed.), Otto Neurath. Gesammelte ökonomische, soziologische und sozialpolitische Schriften, 2 vols., Wien, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1998; Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer. 13

Particularly harsh the opinion of von Mises, who countered many of Neurath’s theses, from the socialist calculation debate to the problem of homo oeconomicus. Mises, remembering his participation to Böhm-Bawerk’s seminar, affirmed: “Especially disruptive was the nonsense that Otto Neurath asserted with fanatical force” (Ludwig von Mises, Memoirs, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009, p.32). On this also: Heinz D. Kurz, Marginalism, Classicism and Socialism in German speaking Countries 1871-1932, in: Ian Steedman (ed.), Socialism and Marginalism in Economics 1870-1930, London, Routledge, 1995, p.13.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

5

The negative perception of contemporaries, however, must not be exaggerated14. Neurath’s curriculum in

economics was outstanding. After precocious studies under the guidance of his father, the economist

Wilhelm Neurath15, he completed his graduation in Berlin under the supervision of the head of the younger

German historical school, Gustav Schmoller, and the economic historian Eduard Meyer. Between 1905 and

1906, back in Vienna, he then attended the renown economics seminar held by Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk16.

Essays by Neurath were printed in Schmoller’s Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 17, in Böhm-

Bawerk’s Zeitschrift für Volkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung18, and in Weber’s Archiv für

Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik19. Neurath also joined the Verein für Socialpolitik and his writings are

present among its published and unpublished proceedings20.

Undoubtedly the part of Neurath’s economic thought that gained him ample recognition even among

contemporaries was war economics. His contribution to its definition as an autonomous field of study with

its own rationale and meaningfulness was generally appreciated by fellow economists and intellectuals. His

very reputation as an economists was mainly based on his writings on the issue. Max Weber, in the chapter

on the sociological categories of social action of Economy and Society, discussed at length Neurath’s work

on war economics, by dealing with in-kind calculations as opposed to monetary calculation21.

“It is true – wrote Weber - that the problems of a non-monetary economy , and especially of the possibility

of rational action in terms of calculations in kind, have not received much attention. Indeed most of the

attention they have received has been historical and not concerned with present problems. But the World

14

Uebel gives a colorful listing of all negative judgments by contemporaries on Otto Neurath, from Lujo Brentano’s definition of Neurath as a “romantic economist of the Ancient Egyptian school” to the alternative stigmatizations as a “bourgeois professor” or as “communist” by Bukharin and Gesell. See: Thomas E. Uebel, Neurath’s Economics in Critical Context, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.75. 15

On the influence of Wilhelm Neurath on the ideas of his son, see: Thomas E. Uebel, Otto Neurath's Idealist Inheritance: "The Social and Economic Thought of Wilhelm Neurath", „Synthese“, 103, 1, 1995, pp. 87-121. 16

The seminar is justly famous given the participation, next to Neurath, of Otto Bauer, Rudolf Hilferding, Emil Lederer, Joseph Schumpeter and Ludwig von Mises. On this seminar see: Harald Hagemann, Capitalist Development, Innovations, Business Cycles and Unemployment, Joseph Alois Schumpeter and Emil Hans Lederer, GREDEG CNRS, 22 November 2012, pp.3-5. 17

Otto Neurath, Zur Anschauung der Antike über Handel, Gewerbe und Landwirtschaft, „Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik“, III, XXXII, 1906, pp. 577-606; Otto Neurath, Zur Anschauung der Antike über Handel, Gewerbe und Landwirtschaft, „Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik“, III, XXXIV, 1907, pp. 145-205. 18

Otto Neurath, Nationalökonomie und Wertlehre, eine systematische Untersuchung, „Zeitschrift für Volkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung“, Vol.20, 1911, pp.52-114. 19

Otto Neurath, Aufgabe, Methode und Leistungsfähigkeit der Kriegswirtschaft, „Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik“, n.44, 1918. 20

The contributions have been republished in English in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.292-298. For a critical appraisal see: Heino Heinrich Nau (ed.), Der Werturteilsstreit. Die Äusserungen zur Werturteildiskussion im Ausschuss des Vereins für Sozialpolitik (1913), Marburg, Metropolis Verlag, 1996. 21

For the English version see: Max Weber, Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Volume 1, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1978, pp.104-107.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

6

War, like every war in history, has brought these problems emphatically to the fore in the form of the

problems of war economy and the post-war adjustment. It is, indeed, one of the merits of Otto Neurath to

have produced an analysis of just these problems, which, however much it is open to criticism both in

principle and in detail, was one of the first and was very penetrating. That “the profession” has taken little

notice of his work is not surprising because until now he has given us only stimulating suggestions, which

are, however, so very broad that it is difficult to use them as a basis of intensive analysis. The problem only

begins at the point where his public pronouncements up to date have left off” 22.

As Weber credited him, Neurath wrote earliest about war economics. His interest in war economics had

been sparked by his father who, himself had written some unpublished material on the issue. He so

published about Kriegswirtschaft from the very beginning of his brief career as an academic economist, in

1909, up to 1818, when he increasingly became concerned with the problem of socialization, economic

planning and administrative economics. In his articles particular attention was given to the differences

between the economic crisis brought about by war and cyclical crises. Neurath tried to depict a very precise

macroeconomic scenario in which real and monetary consequences of war could be analyzed in their effect

on well-being of people. Great care was taken in comparing such modern scenario with ancient economies

where war was considered just one means of acquisition among many and the differences in the underlying

living order procured completely different results.

His analysis always began with a resume on the history of thought concerning war and economics. It is not

difficult to retrace Neurath’s historical presentation of the problem to the influence of the younger

historical school. In fact he explicitly made reference to Gustav Schmoller23 , but also to historians like Franz

Oppenheimer24 and Theodor Mommsen25. Looking back in history, it was easy to find a conception of war

completely opposite to the liberalist one. Aristotle would look at war just as a kind of hunt, and many Greek

and Roman authors would see in war a possibly gainful occupation26. “In this view, -observed Neurath - war

is a natural source of income just like agriculture, robbery, fishing; by contrast, lending money for interest

and commerce were considered unnatural” 27.Given these premises, on hand of many contemporary

authors, among them Diodorus, Polybius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Plutarch, Livy and Appian, he acutely

22

For the English version see: Max Weber, Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Volume 1, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1978, p.106. 23

Gustav Schmoller, Die geschichtliche Entwicklung der Unternehmung, Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot, 1890. 24

Franz Oppenheimer, Der Staat, Frankfurt am Main, Rutten und Loening, 1907. 25

Theodor Mommsen, Römische Geschichte, vols. 1–3. Leipzig, Weidmann, 1854–56. 26

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, p.117. See also: Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 440. 27

Ibid.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

7

analyzed the effects of war on the distribution of income in antiquity, in order to draw a comparison with

the present.

Neurath distinguished wars fought by enlisting part of the peasant population and wars waged through

mercenaries. Whenever farmers were concerned, a short war could enrich, through booty, the whole

population, while a long war could damage little proprietors who worked their land by themselves, while

benefiting large landholders who employed slaves. In case of mercenary troops, they could be a vent for

surplus population and constitute a body of future subjects once granted the property of conquered land.

Considering the practices on the distribution of plunder, general consensus in favor of war could be easily

obtained, because positive economic consequences were particularly evident to troops and enlisted

population. In modern times, instead, when no such practices existed, common man could not easily

evaluate the economic effects of warfare as “the ‘warrior used to booty’ whose heroic deeds were

described by the ancient authors”28.

In antiquity warfare further procured new areas of production and slave labor. If these effects, though, had

to be considered positive or negative for an economy depended on the changes in comparative advantages

following the new acquisitions and the productivity of slave labor. Merchants usually expected gains from

war, thanks to the removal of competition and the opening of new markets, the same held for money

lenders. Negative consequences for the trading and financial sectors, instead, would be limited in ancient

economies by the small development and impact of these sectors. Generally the positive effects for all

strata of population would so overcome the negative ones, in the victorious country obviously.

“In the Middle Ages – observed Neurath further – and at the beginning of modern times, the same view of

war was held as in antiquity. To the victorious it seemed a blessing, to the defeated it was one of the

greatest scourges. Changing fortunes of war could ravage many countries” 29. In the centrally ordered

economies of the time, military administrations and market regulations stood on the same plane and were

both controlled by the government. Not everyone approved war as a way of acquisition. That war could be

profitable, though, nobody denied. This view remained prevalent till the colonial wars of the 17th century,

when authors like Caspar Klock30 extensively discussed the question of war income31.

28

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.156. 29

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.157. 30

On the importance of Klock in the history of economic thought see: Bertram Schefold, Einleitung, in: Kaspar Klock, Tractatus juridico-politico-polemico-historicus De Aerario, Hildesheim, Olms, 2009, vo. 1, pp. V-CXIII. 31

Caspar Klock, Tractatus juridico-, politico-, polemico-historicus de aerario, Nürnberg, 1651.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

8

Neurath was aware that, historically, it had been the spreading of liberalism that had eliminated every

aspect of state administration from the theory of economics, even if the founders of classical political

economy had still been concerned with those issues, along with the prevailing interest in the market

economy. The study of the market economy had had the advantage of allowing a strict theoretical analysis

of specific relationships and problems, but many aspects, as the consequences of war, had so been

completely neglected. Up to the 18th century, on the contrary, war had still been considered one out of

many income sources of wealth, the costs and benefits of which were confronted in order to decide a line

of action32. In 1767 Adam Ferguson still entitled a chapter of his An Essay on the History of Civil Society “Of

National Defense and Conquest”33, while in 1776 Adam Smith already dedicated a chapter of the fifth book

of The Wealth of Nations to “The Expense of Defense”34. It might be concluded that at the end of the 18th

century, the expanding of trade had rendered wars and protectionism more a hindrance than a support to

economic growth. Free traders had further introduced ethical considerations in the economic discourse,

purging it of the notion of wars of aggression. As a result wars were considered only a means of defense

and were evaluated as a cost. “The fact that political economists have given so little consideration to war

within their systems, and that the number of dedicated investigations in no way corresponds to the

importance of the subject, - Neurath stressed - is connected with the great influence the English free

traders still have. They often denied the possibility that a war could enrich people; for them, war was

nothing but a disturbance of commercial economy”35.

But as English economic conditions had favored the emergence of free trade theories, so German

circumstances had inspired protectionist theories by Friedrich List and some of his contemporaries36.

Friedrich List even suspected a certain malevolence on part of English free traders, bent on excluding other

nations from the development path of their country, by imposing free trade as a universal economic policy.

So long as states did not share the same economic situation, protectionism might be needed to avoid

complete economic subjection of less developed states37. List’s voice, though, had remained a fairly isolate

one among the choir of liberalism of the nineteenth century.

32

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, p.117. 33

Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of civil society, Edinburgh, 1767. 34

Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, London, Strahan, 1776. 35

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.154. 36

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, p.118. 37

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.159-160.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

9

“When we leaf through the encyclopedic works on economics of the last century – wrote Neurath – as the

Dictionary of Economics or the Paperback Encyclopedia of State Administration, it is useless to look for

articles on war and its consequences. The same happens with treatises and manuals” 38. An exception were

some empirical studies, related to the Napoleonic Wars, that had tried to quantify and analyze the effects

of warfare on the well-being of the population or the wealth of a state39. In this regard Neurath would

often quote Patrick Colquhoun40 and Joseph Lowe41. Particularly interesting the work of Gustav von

Gülich42, who tried to construe a complete history of trade characterized by war cycles.

At the bend of the century Neurath noticed that the growing dimension of troops and the related financial

and taxation problems had revived the field of war economics. In 1913, in his brief article on the definition

of war economics as an autonomous discipline43, Neurath reviewed such contributions, spanning the first

decade of the twentieth century. He quoted Riesser on the financing problems preceding and following a

war44, Jöhr on the specific case of Switzerland45 and Sombart’s Kriegs und Kapitalismus46. In his Die

Kriegswirtschaft47 he further cited Adolph Wagner48 and Carl August Struensee49.

All these researches analyzed singular problems, but a complete and general study of the issue was still

missing50. “In contrast – noted Neurath – to how special problems are treated, questions concerning the

wide-ranging interconnections of the phenomena are usually only hinted at”51.

38

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, p.345. 39

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, pp.343-344. 40

Patrick Colquhoun, A Treatise on the Wealth, Power, and Resources of the British Empire, London: Joseph Mawson, 1814. 41

Joseph Lowe, The Present State of England in Regard to Agriculture, Trade and Finance; With a Comparison of the Prospects of England and France, London, 1822. 42

Ludwig Gustav von Gülich, Geschichtliche Darstellung des Handels, der Gewerbe und des Ackerbaus der bedeutendsten handeltreibenden Staaten, Bd. 1–5, Jena, Frommann, 1830–1845. 43

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, pp.342-348. 44

Jakob Riesser, Finanzielle Kriegsbereitschaft und Kriegführung, Jena, G. Fischer, 1909. 45

Adolf Jöhr, Die Volkswirtschaft der Schweiz im Kriegsfall, Zürich, Kuhn & Schürch, 1912. 46

Werner Sombart, Krieg und Kapitalismus, München, Duncker & Humblot, 1913. 47

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaft, „Jahresbericht der Neuen Wiener Handelsakademie“, 16, 1910, pp. 5-54. The essay was reprinted as Otto Neurath, Durch die Kriegswirtschaft zur Naturalwirtschaft, Munich, Callwey, 1919. The English translation, based on a draft by Marie Neurath, has been published as: Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.153-199. 48

Adolph Wagner, Finanzwissenschaft, Bd. 1-4, Leipzig, C.F. Winter, 1910. 49

Carl August Struensee von Carlsbach. Über die Mittel, deren ein Staat . sich bedienen kann, um zn seinen außerordentlichen Bedürfnissen, besonders in Kriegszeiten, nötige Geld zu erhalten, in: Carl August Struensee von Carlsbach, Abhandlungen über wichtige Gegenstände der Staatswirthschaft, Bd. 1, Berlin, J. F. Unger, 1800, pp.167-434. 50

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, p.118; Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, p. 343; Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

10

Neurath so arrived at the conclusion that a new theory had to be born for which he proposed the

denomination Kriegswirtschaftslehre52. He had no doubt: “That a specific theory is needed in relation to

war follows from the fact that a war crisis starkly distinguishes itself from the recurrent crises of our

economic order. While ‘normal’crises, for example, have a slow preparation and constrain the whole

economy to successive liquidations, usually starting in a precise sector and then expanding to others, a war

crisis appears abruptly and concerns all sectors of the economy at once. (…) In this sense it is not enough to

take the peace economy and study how war changes its single components, as the monetary system,

credit, production, etc. It is necessary to study all relationships as a whole, as has not been done for a long

time” 53. Neurath would so define war economics as the systematic study of the positive and negative

consequences of war54, a study that would allow to show, at least schematically “how the economic

situation of specific groups of the population can change during the war” 55. To this end “a kind of inventory

of real incomes would have to be designed which then could give an approximate survey of the distribution

of pleasures and displeasures”56.

The reason why such a theory had not been developed yet was that the existing economic theory would

not allow the analysis of different economic orders, taking for granted that only the market order could and

should exist and be studied. Too much, observed Neurath, had economists looked upon astronomy as the

scientific theoretical model of reference. It was useless to search for a universally valid economic order.

Economic orders, instead should have been studied like different machines capable of performing the same

task, machines as dissimilar as could a steam machine be in respect to an electric engine57.

The war economist should so compare, on the base of empirical observations, the economic orders of

singular states in order to reconstruct all interdependencies and evaluate the consequences of war on the

economy in its entirety. Such issues, concluded Neurath, should be researched in depth well before the

reality of a war would constrain to immediate measure taken without the necessary thought58.

gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 439; Otto Neurath, Die Naturalwirtschaftslehre und der Naturalkalkul in ihren Beziehungen zur Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, vol.8, 2, p.245. 51

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.153. 52

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, pp.342-348. 53

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, p.343. 54

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 439. 55

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.153. 56

Ibid. 57

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, p.347. 58

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, pp.119-121.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

11

FIRST ATTEMPTS TOWARD A MACROECONOMICS OF WAR

“The present time is absorbed by the significance of war for the human kind” (Otto Neurath)59

In his first essay on Kriegswirtschaft, written in 1909 for Schmoller’s Jahrbuch, Neurath specifically tackled

the problem of convertibility of Girogeld in times of war60, studying the monetary consequences usually

associated with a war economy. The views expressed in the article were only reinforced in time and can be

traced in all his subsequent publications on war economy. In nuce they already contained Neurath’s idea

that an in-kind economy would sustain the strains of war much better than a monetary one. A quite

revolutionary thesis that was discussed, during his lifetime, by Arthur Wolfgang Cohn 61.

In case of war, noted Neurath, the necessity of gold and silver reserves at disposition of the state was

heightened by the imperative to sustain the international financial credibility of the country and to buy

abroad goods that were no longer available inland. Internally precious metals were needed to confront the

frequent runs on banks and the hoarding of reserves by individuals. Neurath considered inevitable to

suspend convertibility and suggested to do so as soon as possible. All reserves should so be put at disposal

of the government to obtain loans from the international market and buy whatever primary necessity

goods were needed to nourish the population or win the war. Internal payments, instead, should be

cleared through giro credit transfers, eliminating money completely from the circulation. Accounts would

be used and needed only for such transfers, while withdrawals would be prohibited62. If such measures

would not prove sufficient to guarantee the regular functioning of the economy, the state should switch

toward in-kind payments, both internally and externally.

The sketched schema of Neurath’s first article on war economy was fully developed in 1910 in the lengthier

essay on Kriegswirtschaft, published on the journal of the new trade academy in Wien, where Neurath

taught at the time63. The treatise not only elaborated and extended the reasoning lines of the previous one,

59

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 438. 60

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, pp.117-121. 61

The most complete analysis of Neurath’s monetary thought is to be found in: Arthur Wolfgang Cohn, Kann das Geld abgeschafft werden?, Jena, Fisher Verlag, 1920. A more recent appraisal is: Peter Mooslechner, Some Reflections on Neurath's Monetary Thought in the Historical Context of the Birth of Modern Monetary Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel, Neurath’s Economics in Critical Context, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.101-114. 62

Otto Neurath, Uneinlösliches Girogeld im Kriegsfalle, „Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich“, 33, 1909, pp.119-121. 63

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaft, „Jahresbericht der Neuen Wiener Handelsakademie“, 16, 1910, pp. 5-54. The essay was reprinted as Otto Neurath, Durch die Kriegswirtschaft zur Naturalwirtschaft, Munich, Callwey, 1919. The English translation, based on a draft by Marie Neurath, has been published as: Otto Neurath, War Economics, in:

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

12

but added an analysis of the non-monetary consequences of war, in particular those regarding the

distribution of wealth.

Neurath began with an illuminating and provocative statement. He candidly observed that, contrary to the

catastrophic predictions of free traders, “in recent times great wars are not as damaging as might have

been expected, either to the defeated or to the victorious side, and that, on the contrary, something like an

economic boom can be observed during or shortly after the war” 64. He rejected the idea, though, that this

favorable result would be the consequence of some kind of efficiency effect: “Such deliberations – he

contended – start from the assumption that a fixed amount of economic forces and a fixed amount of

money are available, to be used one way or another, whereas in fact things are much more complicated” 65.

War as the selection of the fittest also in the economic sphere had no appeal for Neurath. He, instead,

attributed the positive economic consequences of war to an essential characteristic of modern economies:

the underemployment of resources. Neurath’s thesis on this point merits a lengthier quotation.

“As a consequence of our institutions, - he wrote - especially those regulating money, credit and market

affairs, we are forced to restrict our productive capacity to a certain degree. Cartels intentionally bring it

about that less is produced than could be consumed by the population. Even states themselves artificially

try to prevent saturation with all commodities, partly by their destruction, partly by protective tariffs. Since

then we intentionally do not utilize fully or even waste the available manpower and productive capacities,

there are always sufficient reserves. If disturbances of a certain kind occur as, for example, in the case of

war, restrictions can be removed and productive forces are liberated. In the course of this, wealth may rise

far above the pre-war level” 66.

In the eyes of Neurath, war could so act as a Keynesian policy ante litteram, liberating an economy from an

underemployment equilibrium. War could have, though, a very different economic outcome in case of an

economy already in a full employment situation. “If, however, - noted Neurath – all our powers and means

were already in full operation in peace time, war could cause much more devastation. Even then wounds

may heal quickly; but only in rare cases, for example, if foreign property is seized, could war bring great

Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.153-199. 64

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.160. 65

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.162. 66

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.161.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

13

economic advantages; an economic recovery, however, would not be possible during the war, and the

victorious state would more frequently suffer serious harm as well”67.

Image 1 Assembling of airplane parts in the Karosseriefabrik in Wien-Favoriten (Source: “Österreichs Illustrierte Zeitung” 13. August 1916/Copyright Vienna Library in the City Hall)

67

Ibid.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

14

Obviously this line of thought could not be an incitement to wage war in order to obtain full employment.

Neurath used these considerations, on the opposite, to underline the fallacies of the present economic

order and advocate its complete reformation. “Every reform of our economic system – he considered –

which allows all our powers and capabilities to develop more fully, would therefore be in the interest of

world peace” 68. First step toward such a reform would be to exchange productivity to profitability as

criterion of economic decisions, a feat possible only by switching toward in-kind calculations from

monetary calculation. These hints would be fully developed by Neurath only in further writings. The

remaining part of the essay on Kriegswirtschaft, instead, contained an accurate investigation of the causal

relationships behind the increase in productivity observed in war times69.

The first apparent consequence of war detected by Neurath was a general raising of prices, caused by

increased demand of certain goods: foodstuff, weapons and military provisions. The need for some goods,

then, that could not be imported any more, stimulated inland production and speculations. Shortages could

even inspire innovations and technological advancements. At the same time scarcity of labor could result in

wage increases. “The enrichment of some circles of the population, entrepreneurs, speculators and

workers, reasoned Neurath - indirectly means an enrichment of all those who have goods to sell to these

people. The advantages of the war can therefore far exceed its burdens for wide circles of the

population”70.

To this positive demand effect Neurath also added a monetary one. The increased circulation of paper

money, in his view, had the effect of a stimulus to production and that of a protective duty, in case a sum

would be charged for exchanging paper money against metal. Industries which had artificially limited their

production could so enlarge it with little costs and great profits. Demand could accelerate the velocity of

circulation too, with an ulterior stimulating effect.

The boom could surely be followed by a crisis, but to eliminate crises war was no solution: “in our economic

order a permanent advance without crises is not possible; but this is true for times of peace as it is for times

of war. These obstructions are not caused by production and consumption, not by the political order or the

68

Ibid. 69

In the opinion of Neurath the only study done with a sufficient measure of completeness on the matter had been Henry George’s analysis of the effect of the American Civil War on the economy of the American states. See: Henry George, Social Problems, Chicago and New York, Belford, Clarke and Company, 1883. 70

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.163.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

15

distribution of income, but by the market economy and the credit system” 71. It would be necessary to

change the existing economic order with an economy in kind to overcame cycles.

Lastly, Neurath tried to ascertain the effect of war on the distribution of income in modern economies.

However the state administration managed war demands in terms of goods, through in kind transfers or

not, the consequences on the income distribution would be mixed and not conducible to a definite

direction. The war demands in terms of money, instead, would decidedly influence income distribution in a

precise way, depending on the financing adopted, through taxes or loans.

In antiquity, noted Neurath, war equipment constituted the way through which everyone contributed to

finance a war and the effect was progressive. Booty, then, granted advantages to all. The alternative use of

treasury for financing war would not increase inequality in a particular way. In modern financial economies,

instead, financing war by taxes could be done progressively, while interests on loans would be paid only to

owners of public debt, so favoring only a very limited part of the population or perhaps even foreigners. As

a consequence it would make sense to favor progressive taxes above loans, whose yield was regressive, to

finance wars.

Nonetheless, also the opposite held if, as Neurath underlined, “raising a loan can lead to making goods

available which a nation’s economy possesses but cannot bring into circulation, because there was not

enough money” 72. Here again different effects would follow if loans were drawn from hoarded funds or the

circulating money. In the first case the loan would bring into circulation new funds stimulating production,

an effect not dissimilar from absorbing money that could have financed over-speculation. Such a policy

management would not be simple. “The aim of the loan policy – concluded Neurath – as well as that of the

tax policy often is to increase the real income of the population, possibly to change its composition, and

simultaneously to increase money income. It is difficult, however, to achieve these different goals at the

same time” 73.

As a general rule Neurath held that loans had a much greater stimulating effect than taxes74 and that inland

war requirements should have been covered through inland loans and external ones through foreign loans.

71

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.163. 72

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.174. 73

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.175. 74

„Experience has shown that use of loans often stimulates enterprise and speeds the movement of goods. The state can distribute orders in grand style, workers are employed, more taxes can be paid. These beneficial effects have been noticed particularly in England where it led to the overestimation of loans by many authors. But even disregarding these favourable effects, loans can mean a much smaller burden on a nation than a tax yielding the same amount”.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

16

Image 2 Advertisement for the subscription of war loans in Austria („Zeichnet 7. Kriegsanleihe“, 1917)

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.176.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

17

Neurath further considered indispensable that a state actively managed its own debt on the market, so as

to control its cost and avoid speculation excesses. “Political economy thereby returns to the view which

ruled in the 18th century under the influence of mercantilism. Measures to influence exchange rates of

money and bonds was at the time equally familiar in practice and in theory. Turning away from extreme

economic liberalism means that old traditions are taken up again, now also in monetary theory” 75.

Regarding the disturbances that war could cause to the monetary system of the state, Neurath, as in 1909,

suggested to abolish convertibility immediately, in order to salvage reserves and put them at disposition of

the State as its treasure. One last point deserves to be mentioned on the matter, because absent in the

preceding article and of a certain theoretical value. As seen, Neurath considered that an increased

monetary circulation in war could result in increased production depending on the underemployment of

resources. Another condition, though, was necessary for an issue of paper money to result in augmented

production: “the mood of the population” 76. “Where confidence in the future is strong – wrote Neurath - ,

it is easy for the economy to go on in a lively and prosperous way; but if business is sluggish and speed of

circulation reduced, an increase in money would push the state into repeated issues. There will be no

increase in production, no corresponding increase of tax capacity, no increase of capability to buy bonds –

nothing but a general inflation”77. In the case that hyperinflation and severe financial disturbances could

not be controlled the state would have to recur to in-kind payments, of which war history brought ample

proofs.

Neurath concluded: “The main result of our investigation may be expressed as follows: war forces a nation

to pay more attention to the amount of goods which are at its disposal, less to the available amounts of

money than it usually does. (…) Money reveal itself more clearly as only one of the many means to provide

goods. (…) If productive capacity is intact but not money affairs, one last possibility remains – economy in

kind”78.

75

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.178-179. 76

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.190. 77

Ibid. 78

Otto Neurath, War Economics, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.193.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

18

THE PRACTICE OF WAR ECONOMICS

“Particularly the field of war, in which we often meet the most extreme form of political calculation – the so called machiavellism –

is the strange crossroad of ancient impulses, traditional behavior and cold blooded reflection” (Otto Neurath)79

As seen, Neurath defined the task of war economics to divide states in homogenous groups and compare

them in regard to the prevalence of a monetary or an in-kind economic system, the permanence of

Gemeinschaft-like social structures, the distribution of land, property and income, the kind of military

service adopted, constrictive or not, and the grade of employment of resources80. Thanks to a research

assigned to him by Eugen von Philippovich and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk81, Neurath had a unique

opportunity to experiment his newly defined science in the reality of the Balkan Wars. He so visited Sofia

and Belgrade during mobilization and at the beginning of hostilities. The study had been financed by a

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and would be published in 1913 in a series of articles82 and in

the essay on Serbia’s success in the Balkan War83.

Following the interpretative scheme outlined in 1910, Neurath examined in detail Serbia’s economy before

and during the war to ascertain the superiority in armaments, food and transports that had been decisive

for Serbia’s success against Turkey. In his eyes Serbia had profited from the relative backwardness of its

economy. Serbia’s agriculture, with a prevalence of little proprietorship, presented an homogeneous

economic and social structure, characterized by the institution of Zadruga. These informal cooperatives

diffused credit, functioned as educational centers and provided technological help. These traits of Serbia’s

economy, the prevalence of agriculture and the Gemeinschaft-like structure, guaranteed that the negative

effects of war would be limited to a minimum. In the same direction operated the relative homogeneity of

religion and ethnicity of Serbia, both societal stabilizers.

Although the winter harvest after the declaration of war could not be completely saved, the reduction in

production could be contained and both troops and population could be supported through war. The

trading war with Austria had spurned Serbians to look for foreign markets, stimulating entrepreneurship, as

79

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 442. 80

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 1, p.347. 81

See: Thomas Uebel, Vernunftkritik und Wissenschaft. Otto Neurath und der erste Wiener Kreis, Vienna, Springer Verlag, pp.310-312. 82

Otto Neurath, Kriegswirtschaftliche Eindrücke aus Galizien, „Der Österreichische Volkswirt“, vol. 5, 18, 1913, pp.355-358; Otto Neurath, Die Ökonomischen Wirkungen des Balkankrieges auf Serbien und Bulgarien, „Jahrbücher der Gesellschaft österreichischen Volkswirte“, 1913, pp.1-19. 83

Otto Neurath, Serbiens Erfolge im Balkankriege, Vienna, Manz, 1913. For the English version, see: Otto Neurath, Serbia’s success in the Balkan War, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp.200-234.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

19

had the necessity to provide weapons and military provisions. Also the management of reserves, the use of

gold to back up foreign loans, the control over the circulation of money had been sources of success for

Serbia.

Obviously the surprising success of Serbs had also been the result of Turkey’s weakness. “The political

situation – observed Neurath – was extremely favourable” but “in addition their stage of development

allowed them to enjoy the advantages of an agrarian state based mainly on an economy in kind while they

were already drawing some benefit from a money economy since they were able to raise international

loans. The simplicity of its economic conditions strengthened the impact of this peasant democracy.

National and religious factors supported political and military actions in every respect, and helped to create

a general enthusiasm” 84.

The schema detailed by Neurath in his previous theoretical essays is easily recognizable in the study on

Serbia and the Balkan states. Considering that data were not easily available, Neurath succeeded in

detailing all major points of his theoretical reasoning. Starting with the prevailing agriculture, to the

presence of Gemeinschaft-like structure, to the questions of religion and ethnicity, Neurath correctly

represented the life order of Serbia. He further sketched the capacity of government to administer the

money market and obtain foreign loans, whereas communities and cooperatives maintained the

agricultural activity and managed the distribution of goods. All the while Neurath used whenever possible

in-kind statistics.

The Balkan wars became, so, for Neurath an extraordinary occasion to collect data85 about the emerging of

barter trade, even at international level86, the centralized administration of production, the controlled

distribution of consumption goods and the destabilizing or even vanishing of financial systems. The same

endeavor guided Neurath during WWI.

Ernst Lackenbacher remembered Neurath in 1914 as a the “redbearded giant” that in Galicia entertained

his fellow officers on the field with vivid historical reconstructions87; but the engineer Neumann recalled,

instead, how Neurath convinced a General of the Austrian Army to create a special department of the War

Ministry to collect information a and data. “We should found a department for war economy – he

remembered Neurath to have said - and start work seriously. We are learning a lot from successes, even

84

Otto Neurath, Serbiens Erfolge im Balkankriege, Vienna, Manz, 1913. For the English version, see: Otto Neurath, Serbia’s success in the Balkan War, in: Thomas E. Uebel and Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Otto Neurath Economic Writings Selections 1904–1945, Dordrecht, Kluwer, p.233. 85

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre als Sonderdisziplin, „Weltwirtschatliches Archiv“, 1, 1, 1913, p.23. 86

See: Otto Neurath, Grundsätzliches über den Kompensationsverkehr im internationalen Warenhandel, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, 13, 2, 1918, pp.23-35. 87

Ernst Lakenbacher, Excerpts, in: Marie Neurath, Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Empiricism and sociology, Dordrecht, Springer, 1973, pp. 12-14.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

20

more from failures, but nobody has time to keep a record of our experiences for the benefit of the future.

Through such neglect, they will all be lost and wasted”88.

The Scientific Committee of War Economy was so established in 1916 as part of the Austro-Hungarian

Ministry of War and Neurath was appointed head of the General War and Economics section89. In this

position, Neurath dedicated all his efforts to gather as much figures as possible on the war economy, in

form of statistics but also posters, medals and maps that would help analyze how war had changed the

everyday life of common people90.

Image 3 Balkan Peasants photographed for the book W. F. Bailey, The Slavs Of The War Zone, London,

Chapman & Hall, 1916

88

G. Neumann, Military Life, in: Marie Neurath, Robert S. Cohen (eds.), Empiricism and sociology, Dordrecht, Springer, 1973, p.10. 89

Nader Vossoughian, The War Economy and the War Museum: Otto Neurath and the Museum of War Economy in Leipzig c.1918, in: Elisabeth Nemeth, Stefan W. Schmitz, Thomas E. Uebel (eds.), Otto Neurath’s Economics in Context, Vienna, Springer, 2008, p.133. 90

Otto Neurath, Das wissenschaftliche Kommittee für Kriegswirtschaft des K. und K. Kriegsministerium. Entwurf eines Arbeitsplanes, Kriegsarchiv, Archiv der Republik, Vienna.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

21

His extraordinary efforts in this field were rewarded not only with an official commendation from the

Austrian government, but also with the appointment as director of the Museum of War Economy in

Leipzig91. The museum had as its scope to exhibit to the widest possible public the economic conditions of

Germany during WWI, not only in their monetary form, but also in their informal part. The trading and the

banking sectors would surely be represented through graphs and statistics, but also the innovations

stimulated by shortages and the entire life of single products from production to consumption would be

showed. The expositions should have been interactive, engaging the spectator directly in the

comprehension of the processes through which a peace economy was transformed into a war economy92.

The only major achievement of the museum became the exhibition on War Bolckade and War Economy

held in August 1918. The display exactly followed Neurath’s war economics in showing how war had slowly

diffused an in-kind economy at the expense of the monetary economy. As a consequence the

communitarian spirit had been strengthened, the state had increasingly intervened in economic relations,

agriculture had gained importance and all resources had been directed toward Germany’s self-sufficiency.

Shortly after the closing down of the exhibit, war ended and so the experience of Neurath in the museum.

Leipzig, though, was only the first step in Neurath’s career as a museum director93. It also represented the

beginning of the development of a universal pictorial language that would result in ISOTYPE94.

Isotypes satisfied the enlightenment ideal of Neurath as a universal means of diffusing knowledge,

particularly regarding the economic order. In regard to war economics, Neurath dedicated to it two

silhouettes of Modern man in the making, his book on the economic and social history of mankind through

isotypes. The silhouettes (Image 4) represented, at the eve of WWII, a comparison of different coalitions of

states in terms of in-kind statistics. Instead of evaluating the economic power of the nations through

monetary indexes, Neurath synthetized it in simple and understandable isotypes depicting the availability

of goods.

Such representations might seem a childish result for serious economic research, and Max Weber did not

hesitate to classify Neurath’s in-kind calculations as primitive and short sighted95. To their efficacy there is

91

Nancy Cartwright, Jordi Cat, Lola Fleck, Thomas E. Uebel, Otto Neurath: Philosophy Between Science and Politics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp. 19-21. 92

Otto Neurath, Die Kriegswirtschaftslehre und ihre Bedeutung für die Zukunft, „Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Kriegswirtschaftsmuseum zu Leipzig“, 4, 1918. 93

In inter-war Vienna Neurath directed the Museum of Town Planning (1919-24), and the Social and Economic Museum (1924-34). See: Hadwig Kraeutler, Otto Neurath. Museum and Exhibition Work, Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, pp. 101-174. 94

Hadwig Kraeutler, Otto Neurath. Museum and Exhibition Work, Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, p.115. 95

For the English version see: Max Weber, Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Volume 1, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1978, p.106.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

22

little to counter: it might be noted that in none of the coalitions examined Germany attained the better

results.

Image 4 Relative economic power of different prospective coalitions in a world war as represented through

isotypes in 1939 (Otto Neurath, De Moderne Mensch Ontstaat, Amsterdam, 1940, pp. 84-85)

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

24

FROM WAR A NEW ECONOMICS

“History shows well enough the great influence that theories exercise through their capacity to influence the public opinion with

their strictly formulated results” (Otto Neurath)96

Following the thought of Otto Neurath from 1909 to the end of the experience in the Museum of War

Economy in Leipzig, it is evident how the study of war economy had inspired an entirely new definition of

the economic science97. Increasingly in every further articles on Kriegswirtschaft, Neurath expressed his

dissatisfaction with the current economics, all the while introducing a new theoretical framework for

economic research.

“Economics so far – he so wrote in 1916 – is strictly related to the monetary economy and has so almost

completely ignored the natural in-kind economy”98. This made necessary to retrieve a conceptual world for

the discipline that allowed to research the monetary economy as the in-kind economy, that comprised

home economy, political economy and market economy. Such conceptual world began with a new object

for the theory and practice of economics: wealth. A wealth defined not through monetary measures but in-

kind99.

Starting with this definition Neurath’s economic science could study of the widest possible assortment of

organizational structures and classifying them as to their economy, i.e. their capability to increment the

wealth of mankind. Depending on the group of people the happiness of which was object of study, it could

include family’s economy, political economy and also cosmopolitan economy, all subdivisions that, taken

from Aristotle to Friedrich List, were now granted validity in new fields. Not only past economies, but also

present and future orders of life (Lebensordnungen) possessed the right to be studied and classified as to

their effects on people’s sensations (Lebenstimmungen). Economics became thusly a comparative science

based on empirical data statistically collected, but consisting of an infinite number of models, many of

which with no relation whatsoever to reality. In this sense Neurath excluded any kind of ethical prejudice

from restricting economic analysis. Acquiring methods as war and smuggling should, in his view, have been

96

Otto Neurath, Die Naturalwirtschaftslehre und der Naturalkalkul in ihren Beziehungen zur Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, vol.8, 2, p.245. 97

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft“, 69, 1913, pp.433-501. 98

Otto Neurath, Die Naturalwirtschaftslehre und der Naturalkalkul in ihren Beziehungen zur Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, vol.8, 2, p.246. 99

Otto Neurath, Die Naturalwirtschaftslehre und der Naturalkalkul in ihren Beziehungen zur Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, vol.8, 2, p.246.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

25

studied exactly as market exchange and production, being evaluated, by economists, only in their effect on

people’s Lebenstimmungen.

It comes as no surprise that the most famous image of Neurath, that of the ship, is to be found for the first

time in his essay Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehreof 1913. “We are like seamen – wrote Neurath – who

on open sea are constrained to reconstruct their vessel, changing its entire structure, by substituting beam

by beam, with pieces they are carrying along with them or find drifting. They cannot make port so they will

never be able to eliminate the ship entirely and rebuild it completely. The new ship always comes out of

the old one through a continuous restoration“ 100.

Neurath’s images bore a strong message: no science would ever be complete, no science could be rebuilt

from scratch. A statement firstly made, with rhetorical vehemence, discussing war economics. Through it

Neurath attacked the pretense of scientists to produce perfect and complete systems of thought with no

defects or anomalies, allowing no changes or amelioration. Such ‘systematists’ were “born liars” because a

perfect system, in economics as in science, could only remain an eternal aim, never to be attained101. Trying

to build such a deceitful system was neither the way of science nor of philosophy: “In logic, or physics,

biology or philosophy we cannot put some undisputable statements on top and then logically derive from

them an entire chain of thought. Inadequacies always contaminate the entirety of this ideal world, starting

from the premises as from later consequences. No precaution can prevent this outcome, nor renouncing all

previous knowledge, starting from a tabula rasa, to achieve a better result” 102. A clear accusation toward

the systematic turn taken by the Austrian school103.

Neurath had identified many cases under which, in a market economy, the results of exchange were sub-

optimal. For example when a consumer had to choose among two identical products with identical prices,

or when limited rationality claimed the scene as with differentials in stock prices104. The major distortion to

economy, in terms of Lebenstimmungen, though, was consequent to the widespread adoption throughout

the market economy of a calculation based on prices. Such calculations, along with the institution of credit,

constrained the production to maximize profits, so causing recurrent crises of overproduction. Would the

100

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 457. 101

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 456. 102

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p. 456. 103

Otto Neurath, Die Naturalwirtschaftslehre und der Naturalkalkul in ihren Beziehungen zur Kriegswirtschaftslehre, „Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv“, vol.8, 2, p.258. 104

Otto Neurath, Das Begriffsgebäude der Wirtschaftslehre und seine Grundlagen, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft“, vol. 73, n. 4., 1917, pp. 499.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

26

economy be ruled by the maximization of productivity instead of profitability, crises, for Neurath, would no

longer plague the world.

To the naïve arguments of pacifists, then, Neurath countered that the origin of present wars, wars between

social classes as wars between nations, was to be found in the lack of economic efficiency of the present

economic and life order. He wrote: “The present underemployment of existing forces, that is typical of our

Ordnung, incites to war: it is necessary, for example, to defend oneself from foreign wares and foreign

laborers or oblige others to buy our wares or accept our workers, and all of this because it is not

spontaneous to enter in cooperative relations between states; furthermore it is easy to alleviate the costs

of war thanks to reparations; and lastly because at times war frees productive forces that would otherwise

be bound. The uneconomic construction of our Lebensordnung is the cause why at present war causes

lesser evils than in a more economical Lebensordnung the case would be” 105.

War could be avoided only by becoming uneconomical. If detrimental to all parties concerned, war would

become an avoidable choice. To this end Neurath considered the best solution to forge broad alliances that

possessed the same economic power, i.e. an equal amount of productive forces106. Obviously another

opportunity existed to foster peace: abandoning the present inefficient life order for a more effective one.

From war, from the spreading of in-kind calculations could then emerge an entirely new Weltanschauung

capable of molding the world to diffused wealth and general peace. An utopia that was worth to guide an

economic calculus not just bent on the past but projected toward the future.

105

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, p.500. 106

Otto Neurath, Probleme der Kriegswirtschaftslehere, „Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswirtschaft“, I, 3, 1913, pp. 465-66.

Monika Poettinger Otto Neurath’s War Economics

27

CONCLUSIONS

Inspired by his father’s critique of modern capitalism, Otto Neurath looked at war as to a sudden and

ubiquitous shock for the present economic order that could reveal and perhaps cure many of its

malfunctions. He so dedicated many writings of his brief academic career, spanning from the beginning of

the twentieth century to 1918, to define a field of study dedicated to war economics. He gained ample

recognition for his efforts, before and during WWI. His writings were published by the main journals of the

time, the most important economists and sociologists discussed his theses. The vehemence of some critics

only demonstrated that Neurath’s outrageous reasoning was felt as threatening by the newly emerging

orthodoxy.

In the first essays on war economics Neurath attempted to sketch a dynamic macroeconomic schema that

could help to evaluate the effects of war on the distribution of wealth in ancient and modern economies. In

doing so he touched many crucial points of economic theorization, from the active management of public

debt to fiscal and monetary stimuli to demand. Unsatisfied by the results obtainable in remaining inside the

fences of an economic system, Neurath further investigated how, through a redefinition of the economic

science as a whole, it would be possible to create a conceptual framework for economics that would allow

to study, along the same lines, war and peace economics, state administration and market order.

As a mechanic who had to compare machines, different as a diesel motor could be in respect to a steam

machine, could recur to PS evaluation to decide which one would be more effective, Neurath opted for a

measurement in terms of wealth creation, to offer a criteria of choice between diverse economic orders.

His economics, born out the acute observation of war conditions, became so the science of collective

wealth, as representative of the individuals’ sensations and measured through in-kind statistics.

Such an economics would encompass all possible life orders, comparing them as to their capacity of

enriching people’s life: a science for dreamers and utopians as much as of bureaucrats and technicians.

Neurath could so dream away economic crises and wars, by simply substituting a criteria of productivity to

the one of profitability, by using in-kind measures instead of prices. A peaceful revolution born out of the

catastrophe of war.