Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling (2012)

Transcript of Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling (2012)

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling

Thomas Herzog

Arab culture is an originally oral culture in which the spoken word occupies a centralposition. All important foundation texts of Arab culture are orally performed and trans-mitted texts: pre-Islamic poetry and prose, the Qurʾān – which according to Islamictradition was finally written down more than three decades after the first revelations –and tales about the ‘heroic age’ of the Muslims, the conquest of the Prophet and theearly Muslims. This original orality explains why oral performance and transmission playan important role alongside literacy in Arab-Islamic culture to this day. In this chapterthe most important stages of oral epic narration will be traced from the jāhilīya, the pre-Islamic period (lit. ‘the time of ignorance’), to the heyday of the cultivation of popularoral narratives from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries. The writing down of theQurʾānic revelation , marking the beginning of an era of parallel orality and literacy,and, from the third Islamic century onward, the existence of diglossia – the dichotomyof a learned standard language, in which ‘true’ texts are composed, and a vernacular ofthe unlettered, whose verbal productions cannot claim any truth – explain why Arabculture has not developed any narratives that are openly designated as epics, while itnevertheless possesses a genre that might be termed ‘epic’.

If epic is understood in its widest sense as a narration of events that are of impor-tance to a society and provide a grounding in its (primordial) past, as a narration thatcreates and consolidates identities and provides an orientation in the presence of thenarrative,¹ then the art of oral epic composition and narration was known to the Arabsfrom earliest times. For the pre-Islamic Arabs, who led the life of nomads in a desolateexpanse of desert, filled by the whiteness of glaring heat, poetry played a prominent roleand was even the centre of their cultural creativity. In the pre-Islamic era, practicallyeach of the nomadic groups (tribes, clans) on the Arabian Peninsula counted among itsranks a shā‘ir or poet. The shā‘ir was endowed with a special power of speech and wasbelieved to be inspired through the world of spirits; his speech was both prophecy andspellbinding magic word. His main function, however, was that of a mouthpiece of hisclan; he went to battle with his tribesmen, derided their enemies (h. ijāʾ ‘satire’) and coun-tered their poets’ attacks, praised his clan’s past deeds of prowess and exalted their heroes( fakhr); he was the living memory and historian of his clan.² Poets have repeatedly con-

¹ See Assmann 1997 and Halbwachs 1925.² The second caliph ‘Umar b. al-Khat. t. āb (r. 13–23/634–644) is reported to have said that poetry is

the dīwān (register, memory) of the Arabs.

tributed to victory by their presence in the front-line and have given consolation to thesurvivors of a battle by their poetic exaltation of the slain. Clans and tribes gatheredhabitually for poetic contests, frequently in connection with pilgrimages to the deitiesof pre-Islamic Arabia.³ To no small degree the weal and woe of a clan depended on thepoetic talent of their shā‘ir; a clan or tribe without a renowned poet counted for noth-ing.⁴ The shā‘ir often had as associates one or more rāwīs, ‘rhapsodes’, transmitters of theclan’s traditions in poetry and prose.⁵ We owe to them the preservation of (probablyonly a small part of ) pre-Islamic poetry⁶ and at least partially also the transmission ofmostly short prose narratives, some with inserted poems, about the so-called ‘days ofbattle’ of the Arabs before they united under the banner of Islam.⁷

These tales about pre-Islamic tribal feuds⁸ are recollections of small skirmishes, indi-vidual cattle-raids (ghazwa) or murders,⁹ but also of great wars between mighty tribalfederations, which lasted for decades, and they are told again and again in the evening

Thomas Herzog628

³ In this way the famous mu‘allaqāt, the ‘suspended (verses)’, came about; they were the verses of thebest poets that were attached to the Ka‘aba in Mecca, which was a sanctuary already in the pre-Islamic era. Every pupil in the Arab world even today can quote by heart the ‘suspended verses’ ofImruʾ l-Qais and of ‘Antara b. Shaddād, to mention only the most famous of these poets. For themu‘alaqāt, see Lecomte 1993.

⁴ For the pre-Islamic tribal poets, see Blachère 1952–66: II, 383 ff. See also Fahd 1997. The traditionof oral poetry is still alive on the Arabian Peninsula today; see Sowayan 1985 and 1992; Kurper-shoek 1994–99; Caton 1990.

⁵ For the rāwī, see Jacobi 1995. [See further ch. 5 on performance and performers by J. Harris and K.Reichl in this volume.]

⁶ The debate about the purely oral character of this tradition (see Zwettler 1978:85–88) and theearly use of writing, at least as a mnemotechnic help (see Sezgin 1967–2007:53 ff.; Brockelmann1943–49: II, 14 ff.; 22–33), has not yet been settled. Fuat Sezgin, who transfers insights fromresearch on the Prophet’s sayings and deeds (h. adīth) to the transmission of poetry, conjectures withgood reason that written poetry collections existed already in the early Islamic period. According toJacobi (1987:21) there are no unequivocal proofs for a written transmission as early as the sixthcentury. J. T. Monroe (1972) and M. Zwettler (1978) apply Parry’s and Lord’s oral theory (Lord1960) to Old Arabic poetry and reach the conclusion that the Old Arabic qas.īda is basically anorally composed genre in Parry’s and Lord’s sense. They have, however, expressed reservations aboutthe uncritical application of the oral theory, formulated with regard to long anonymous South Sla-vic epics, to the Old Arabic poems, which are neither consistently narrative nor anonymous and arein addition relatively short. Hence, as Jacobi notes, ‘their theories are in the end not as revolutionary… as it a first seemed’ (1987:22). It can nevertheless be supposed that pre-Islamic poetry was com-posed orally and probably for long periods of its early history was also transmitted orally. [Seefurther ch. 2 on the oral-formulaic theory by J. M. Foley and P. Ramey in this volume.]

⁷ For the ayyām al-‘arab see the authoritative work by Caskel 1931. Tribal feuds did not, of course,disappear after the introduction of Islam, but only few of them have been incorporated into thecorpus of the ayyām al-‘arab, which was put together in writing in the third Islamic century (ninthcentury). The reason for this is on the one hand the interest especially in the pre-Islamic ‘paganperiod’ from a cultural and historical point of view, on the other that the acceptance of Islam meantthe entry into a principally inner-Islamic peaceful society (umma).

⁸ The technical term for an ayyām report is h. adīth, the same word which was later used for theaccounts of the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muh. ammad.

⁹ ‘Tribes among which there was no contract muwāda‘a,‘ahd […], are in a state of war, i. e. they try toraid each other’s herds in armed raids. […] Even an assault on a family, a murder, counts as a “day”’(Caskel 1931:2).

tribal meetings (majālis).¹⁰ In the second Islamic century (8th c.) the traditions of theayyām al-‘arab (as well as pre-Islamic poetry¹¹) were collected and written down by Arabphilologists and preservers of documents about the pagan prehistory of the Arabs.¹²With reference to the preserved traditional layers of the Old Arabic epic material, Cas-kel has clearly demonstrated how extended epics can arise from even the smallest singlenarratives. He has convincingly shown how, the more remote the historical ‘day of bat-tle’, the more these narratives developed from brief reports to voluminous ‘chains oflegends’, in which several ‘days’ are woven into a narrative unity. Similarly, we canobserve ‘the predilection for romantic¹³ instead of realistic motifs and, instead of conciseaccounts, the preference for elaborately constructed tales’ (1931:76). The ‘battle days’ ofsome clans which occurred shortly before unification under Islam (at least ideally) havebeen transmitted as brief single tales; the long wars that were presented as having lastedfor decades and were thought to have been the feuds of whole tribes, ¹⁴ such as the warsof Basūs and Dāh. is, were placed several generations before the Prophet Muh. ammad.Caskel writes that ‘these wars were not real. They are the product of a tradition, in thecourse of which several “days” coalesced and were put into a frame. […] The process ofgiving theses stories a frame was still fluid when the texts were written down […]. Therewere certainly no wars of Dāhis and Basūs, just as there was no war between the Bakrand the Tamīm, about which we could possibly read if the unsettling of the Old Arabictradition by Islam had happened fifty years later.’¹⁵

The revelation of the Qurʾān, the ‘collection of the texts recited by the ProphetMuh. ammad between c. 610 and 632 as divine revelations issued to him’ continues the

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 629

¹⁰ Caskel notes (1931): In the majālis ‘even today the “days” of the present time are told.’As evidenceCaskel quotes Leachmann’s report from the military camp of Ibn Rashīd in 1910 [The GeographicJournal, March 1911, 271]: ‘At night the conversation in the diwans is of a most enlightened char-acter, chiefly consisting of battle stories or family history […]’ Caskel continues: ‘As the heroes ofthese tales one might think of men like, in the present time, H. uwāyt.āt.–Shāikh ‘Awda Abū T.ayah,“the greatest fighting man in Northern Arabia”, of whom Lawrence [of Arabia] writes: “He saw lifeas a saga. All the events in it were significant: all personages in contact with him heroic. His mindwas stored with poems of old raids and epic tales of fights […]”’ (1927:94).

¹¹ The hypothesis that the largest part of pre-Islamic poetry was faked, advanced simultaneously by theEgyptian T. āhā H. usain (1926) and by D. S. Margoliouth (1925), is meanwhile considered to havebeen proved wrong.

¹² Famous transmitters are al-As.mā‘ī (d. 213/828) and Abū ‘Ubaida (d. 210/825), as well as Ibn al-Kalbī (d. 204 or 206/819 or 821). The old ayyām books of these authors have been lost. Remnantshave, however, been preserved in the works of later authors, as for instance in the Kitāb al-Aghānīof Abū l-Faraj al-Isfahānī (d. 356/967) and especially in the ‘Iqd al-Farīd of Ibn ‘Abd ar-Rabbih (d.328/940), both of whom tried to harmonize diverging sources, an effort that has not always led to asmooth result without contradictions. In the Abbasid era (second/eighth – seventh/thirteenth cen-tury) knowledge of the ‘days’ of the pagan Arabs was part of ‘humanistic education’ (Caskel). Greatuniversal historians and encyclopaedists of the post-classic period like Ibn al-Athīr (d. 630/1224)and an-Nuwairī (d. 732/1332) used the reports about the ayyām al-‘arab for the section on the pre-Islamic history of Arabia.

¹³ Such as giving shelter, vendetta, heroic deeds.¹⁴ This is unhistorical, as Caskel says, ‘because these tribes form no political, but an ideal and genealo-

gical unity’ (Caskel 1931:76).¹⁵ Caskel 1931:76–77. The ‘war of the Bakr and Tamīm’ could have been the title of the collection of

many ‘days’ of these two tribal federations shortly before the advent of Islam.

cultural tradition, i. e. the tradition of the oral recitation of poetic and aestheticallypleasing texts; from a literary point of view, the Qurʾān certainly has such poetic andaesthetic qualities. Although the Qurʾān is not composed in a poetic metre, it neverthe-less contains frequent passages in rhymed prose (saj‘), and it was probably recited by theProphet in a expressive and aesthetically impressive manner, not unlike the poetry of thepre-Islamic era. The poetic as well as the oral character of the Prophet’s revelations isunderlined by the words which ‘a figure clothed in light’ – the Archangel Gabriel accord-ing to Islamic tradition – spoke in the Prophet’s first revelation in a cave near Meccaaround the year 610:

‘Iqraʾ bi-smi rabbika / alladhī khalaq /khalaqa l-insāna min ‘alaq / iqraʾ wa-rabbuka l-akram /alladhī ‘allama bi-l-qalam / ‘allama l-insāna mā lam ya‘lam […]’¹⁶

Recite: In the Name of thy Lord who created, created Man of a blood-clot. Recite: And thyLord is the Most Generous, who taught by the Pen, taught Man that he knew not.

Orality is implied by the imperative iqraʾ of the verb qaraʾa, which means primarily ‘torecite’ and has taken on the meaning ‘to read’ only in the course of a later semanticdevelopment.¹⁷ While the Qurʾānic revelation continues oral tradition, it also marks thebeginning of the era of writing. For, in the early period of preaching Islam, the Qurʾān’srecitator, the Prophet, found himself in a precarious competitive relationship to theadherents of Old Arabian polytheism and their preachings. The Prophet was repeatedlyblamed for being no more than another of these poets (shā‘ir) or magicians who tellinvented tales.¹⁸ Modern Qurʾān scholarship is of the opinion that the Qurʾān was writ-ten down very early on, an event which gave the Arabs a written ‘book’ (like earlier theJews and the Christian with whom they were in contact);¹⁹ this opinion is founded onthe fact that it was vital for the survival of the young religion to distance itself from thereproach of poetry and magic. According to the Qurʾān scholar Angelika Neuwirth it isprecisely this (dangerous) closeness to the modes of poetic reciting that makes it prob-able that even in the earliest period the Qurʾān was in fact not entirely recited andmemorized without some help of writing.²⁰ At the latest, with the writing down of theQurʾān in its canonical form under the third caliph ‘Uthmān (r. 23/644–35/656), theQurʾān changed from the realm of primary orality to that of secondary orality, i. e. oralrecitation on the basis of a fixed written text. The written text, which came aboutthrough the necessity to distance the Prophet from the poets and seers of the pre-Islamicperiod, to preserve the divine revelation verbatim,²¹ to eliminate competing versions andto be on a par with Jewish and Christian ‘possessors of the book’, also marks a mentalchange: the transition to an era in which written texts are seen as composed by culturalauthorities and hence endowed with a claim to being true, while oral works, especiallythose in the vernacular, in colloquial Arabic, which have not been put down in writingby authorities, are assigned an inferior status. From this we may understand how the

Thomas Herzog630

¹⁶ Sura 96 Sūrat al-‘Alaq/The Blood-Clot [i. e. the embryo], 1–5. English translations are taken fromArberry 1964 (here, p. 651).

¹⁷ According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet was illiterate. The word Qurʾān comes from the sameroot as qaraʾa; it is a text to be recited. See also below n. 2.

¹⁸ These reproaches have found their way into the Qurʾān in the form of vehement rejections; see,e. g., sura 21, 3; 5 (Sūrat al-Anbiyāʾ/The Prophets). According to unanimous opinion, this sura was

writing down of the Qurʾān and the rise of a class of literate religious scholars, who havethe monopoly of interpretation and who, following the Prophet, have defended theQurʾān against all assimilation with poetry or legend (ust.ūra),²² have determined theattitude of Arabic-Islamic culture vis-à-vis oral fiction and in consequence oral epic aswell. Nevertheless the Islamic scholarly world is until today characterized by the co-exis-tence of orality and literacy. Central texts of religion, philosophy and all kinds of sciencewere transmitted by word of mouth, side by side with their recording in writing; in fact,listening to the Prophet’s tradition from the mouth of an authorized transmitter hasalways had a higher value than simply reading it in a manuscript.²³ The Arabic poetrywhich was cultivated in the courts during the first five Islamic centuries was always orallyrecited and partially also orally transmitted. The Qurʾān itself is memorized to this dayand comes fully alive only in oral recitation (as a text intended for aural reception),while the written book of the Qurʾān often only serves as a prop for memory and aguarantor of the correct recitation of God’s word (with the exception of blind recitators,who of course have no written props).

With the unprecedented victorious spread of Islam within only a few years over ahuge territory with a non-Muslim and often non-Arab population, which was slowly butsteadily Islamized, attacks of the Prophet’s enemies on him and on the Qurʾān werepushed into the background. The definition of what is truth and what is lies, of what ishistory and what is legend was now in the hands of a cultivated class of specialists thatbelonged to the ruling Muslim minority. In that early period the narrative Jewish, Chris-tian and South-Arabian traditions, which had probably circulated orally before, were writ-ten down. According to Franz Rosenthal, these ‘historical novels’, as he calls them, ‘becamea part of historical literature which was no longer transmitted by storytellers, but by theordinary process of written or oral scholarly transmission, and the novelistic origin ofwhich was no longer realized’ (1952:164). The wish to collect and write down theseSouth-Arabian legends and tales about the Jewish prophets (called isrāʾīliyāt) stems fromthe fact that the Qurʾān repeatedly either talks about or alludes to events of South-Ara-bian history and Jewish religious history, on the presupposition that those listening to theQurʾān preached by the Prophet would already be familiar with these stories.²⁴ These stor-ies, however, are never told consecutively from beginning to end as in the Hebrew Bible.²⁵

As the knowledge of South-Arabian history or of the Hebrew Scriptures could notbe expected of the newly converted Muslims in the conquered territories, and was oftenlacking also in native Muslim families, it had to be supplied in order to provide anunderstanding of the Qurʾān. These narrative traditions were therefore collected andwritten down, in particular by converted Jews and/or Yemenites, the most famous ofwhom was the Yemenite Wahb b. al-Munabbih (d. 110/728 or 114/732).²⁶ It can beassumed that these narratives, in addition to their place in Muslim exegesis and historio-graphy, were soon also transmitted in the milieu of oral popular narratives, in particular

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 631

revealed in Mecca; it therefore belongs to the suras of the early period, in which Muh. ammad metwith much hostility and was in the end forced into emigration (h. ijra) from Mecca to the oasis ofYathrib, the later Medina. ‘The evildoers whisper one to another, “Is this aught but a mortal like toyourselves? What, will you take to sorcery with your eyes open?” […] Nay, but they say: “A hotch-potch of nightmares! Nay, he has forged it; nay, he is a poet [shā‘ir]! Now therefore let him bring usa sign, even as the ancient ones were sent as Messengers”’ (Arberry 1964:323).

at a period when an increasing number of people became Islamized; no traces of thishave, however, been preserved from the early Islamic era.²⁷

In the time of Wahb b. al-Munabbih, the second Islamic century (8th c.), the prosenarratives about the life and deeds of the Prophet and the conquests during and after hislife-time were written down. Summary descriptions of the Prophet’s military expeditions(his ‘battle days’, ayyām), which are called maghāzī, arose as early as the first half of thesecond/eighth century, also from the pen of Wahb b. al-Munabbih, and, at a somewhatlater date, the best-known older work of this genre, the Kitāb al-Maghāzī by ‘Umar al-Wāqidī (d. 207/822) was composed (Leder 2005). Together with other sources, thesetales furnished the building blocks of the Prophet’s biography, the Sīrat an-Nabbīy orSīrat Rasūl Allāh.²⁸ The natural continuation of the maghāzī and sīra literature werethe so-called futuh. (conquest) books, at first works about the conquest of individualcountries, as for instance the Kitāb futūh. ash-Shām (Book of the conquest of Syria) andthe Kitāb futūh. al-‘Irāq (Book of the conquest of Mesopotamia) by Wahb b. al-Munab-bih, both lost today.²⁹ Later on comprehensive descriptions were written, such as the

Thomas Herzog632

¹⁹ The Qurʾān calls itself a ‘book’ (kitāb) in sura 2, 2 (al-Baqara/ The Cow), which was revealed at arelatively late date: ‘That is the Book, wherein is no doubt, a guidance to the godfearing’ (Arberry1964:2).

²⁰ See Neuwirth 1987:102. Neuwirth argues from a philological point of view with reference to Syriacqeryānā that the Qurʾn, at least for a certain period of its genesis, was a lectionary or a collection oftexts for liturgical recitation.

²¹ According to Islamic doctrine, the Qurʾn is the direct word of God: in his revelations, extending overtwenty years, God is believed to have communicated the text to the ProphetMuh. ammad with exactlythese words and sounds. On the various schools of Qurʾnic interpretation, see Goldziher 1920.

²² This reproach, in the form of a vehement rejection, has also found repeated expression in the Qurʾ-ān, as, for instance, in sura 6 (al-An‘ām/Cattle), 25; 28–29: ‘And some of them there are that listento thee [the Prophet], and We lay veils upon their hearts lest they understand it, and in their earsheaviness; and if they see any sign whatever, they do not believe in it, so that when they come tothee they dispute with thee, the unbelievers saying, “This is naught but the fairy-tales of the ancientones [asāt. īr (pl. von ust.ūra) al-awwalīn].” […] they are truly liars. And they say, “There is only ourpresent life; we shall not be raised.”’ (Arberry 1964:123–24).

²³ This is the reason why Islamic scholars, in their early years and often during their entire life-time,travelled to search for knowledge (ar-rih. la fī t. alab al-‘ilm), to hear as many traditions about theProphet and scholarly works directly from the mouth of an authorized transmitter (samā‘a) and toreceive from him a licence (ijāza) for (oral) transmission. See also Berkey 1992:24.

²⁴ How many of the Meccan listeners to the Qurʾān actually knew these events and stories is difficultto assess. It is nevertheless clear that the Qurʾān presupposes such a knowledge.

²⁵ In this the Qurʾān resembles pre-Islamic poetry, which also merely alludes to events that could besupposed to be known to the poet’s audience. Here the Qurʾān is decidedly different from the con-secutive narratives of the Bible.

²⁶ Important collectors in addition to Wahb b. al-Munabbih were Ka‘b al-Ahbār, (d. 32/652–653), aYemenite Jew before his conversion to Islam and an authority on Biblical history and the South-Arabian tradition; ‘Abdallāh b. Salām (d. 43/663–664), a Jew from Medina, who was converted toIslam by the Prophet himself; and Ibn Sharya, whose historicity is disputed.

²⁷ See below, p. █, on the so-called qis.as. al-anbiyāʾ.²⁸ The most important sīra author is Ibn Ish. āq (d. 151/768). The original is lost; his work is preserved

only in Ibn Hishām’s (d. 215/830) revision. See further Busse 1987:264–68.²⁹ To Ibn ‘Abd al- H. akam (d. 257/871) is due a book on the conquest of Egypt and Northern Africa

(Kitāb futūh. mis.r wa-l-maghrib); Ibn Qūt. īya (son of Gothic mother) (d. 367/977) wrote a work onthe conquest of Spain, etc.

famous Kitāb futūh. al-buldān (Book of the conquest of the countries) by al-Balādhurī(d. 279/892).

It is highly likely that in addition to the sīra, maghāzī and futuh. literature com-posed by learned authors there circulated unauthorized, orally performed and trans-mitted popular sīra, maghāzī and futuh. narratives from the earliest Islamic periodonward.³⁰ Already from this period we have reports about spontaneous preachers andorators who told events from the life of the Prophet and his companions (sīra), fromhis and his successors’ conquests (maghāzī and futuh. ) to their audience in the mosquesor the bazaars in an attempt to familiarize them with the teachings of Islam. These pop-ular preachers, generally called qās.s. (plural qus.s.ās.; also mudhakkir or wā‘iz) (Pellat 1978),inserted into their sermons not only canonical South-Arabian legends and the isrāʾilīyāt( Jewish Biblical tales), but also inauthentic narratives about the Prophet, tales from Ira-nian tradition and fantastical legends of all kinds of provenance, which resulted in theirbeing forbidden to preach in the mosques. If one believes the criticism of the religiousscholars, who were concerned about their monopoly of interpretation, then thesepreachers of religious ‘truths’ have to be seen in the vicinity of mountebanks and popularentertainers. It is said that already ‘Alī b. Abī T. ālib, the Prophet’s son-in-law, hadexpelled the qus.s.ās. from the mosque of Bas. ra. Many more interdictions followed, butapparently failed, since these narrators, while they did not preach any more in the mos-ques, had considerable success outside the mosques among the gullible masses. From thisearly period no texts of the popular maghāzī have been preserved; the extant texts comepredominantly from the seventeenth century, some also from the fifteenth century.³¹The popular maghāzī of these late manuscripts are in part based on ‘historic’ events,but they are also in part creations of pure imagination. Their main hero, apart fromMuh. ammad, is especially his cousin and son-in-law ‘Alī b. Abī T.alib. From the twelfthcentury onward we have numerous learned, but also popular, often romance-like elabo-rated manuscript texts of the genre qis.as. al-anbiyāʾ, stories about the pre-Islamic pro-phets, in which Islamic as well as extraneous narrative traditions about the prophetsbefore Muh. ammad (Qurʾān, South-Arabian legends, isrāʾilīyāt) were woven into consis-tent narratives.³² According to Rudi Paret the popular futuh. tales were composed in theperiod between the ninth and eleventh century (possibly earlier in oral form)(1970:746). These ‘romance-like enlarged legendary accounts’ of the great Islamic con-quests after Muh. ammad’s death – of ash-Shām (Syria), al-Irāq (Mesopotamia), Mis. r(Egypt) – have generally been attributed to al-Wāqidī, the author of canonical futūh.books, but cannot come from his pen on account of their style and contents; they are

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 633

³⁰ It can be inferred from the ‘novellistic style of the accounts of some early Islamic historiographerssuch as Saif b. ‘Umar [who lived at the end of the second/eighth century] that in that period theprocess of popular fictionalization was already in full swing’ (Heath 1990:428).

³¹ About half of these texts name an enigmatic (Abū l-) H. asan al-Bakrī as rāwī (transmitter/ redactor/author – the various nuances of this word are fluid), who is placed by Paret in the end of thethirteenth/ beginning of the fourteenth century. Paret bases his chronology on the traditional phi-lological method, which, however, is not fully adequate to this type of literature. See Paret1930:155–56.

³² See Nagel 1967, 1986a and 1986b; Rippin 2002.

most probably anonymous, popular works, which were ‘widely disseminated particularlyduring the Crusades as an incitement to the warriors for the faith’.³³

The fact that, beginning with the ninth century, an increasing number of manu-scripts of popular narratives concerning the legendary life of the prophets (qis.as. al-anbiyāʾ) and the Islamic conquests (maghāzī and futūh. ) have come down to us, is anindication of a fundamental change in the Arabic language and culture of this time.While in the first two Islamic centuries (7th–8th c.) Arabic was the living language ofthe dominant minority in the conquered territories and underwent a process of standar-dization and adaptation in the works of Arab lexicographers and grammarians,³⁴ in thecourse of Islamization and Arabization there arose a situation of diglossia, in which agrammatically and lexically standardized, highly nuanced and complex written languagewas confronted by grammatically simpler, lexically reduced and regionally varying verna-cular Arabic dialects. At the same time as this freezing of Classical Arabic into a purelanguage of writing and of the elite, starting roughly in the beginning of the fourthIslamic century (10th c.) (Fück 1950:86) and the powerful rise of spoken dialects, thepolitical unity of Islam under a universal Islamic-Arab caliphate began to succumb to aspreading process of erosion. The old Arab elite was to a growing degree supplanted by aformerly unfree, at any rate non-Arab military class, which alone could guarantee thesafety of the Arab Empire – at one time united and centrally administrated, but nowbroken up into single dominions – against the inroads of the Turks and Mongols fromthe East and the European Crusaders from theWest. At the end of this development wehave the Mongol conquest of Bagdad, the seat of the caliph, the murder of the lastAbbasid caliph in Bagdad in 1258 and the definitive assumption of power by the Mam-luks, a dynasty of originally military slaves, in the person of Sultan Baybars I in Egyptand Syria in 1260. While in the first three Islamic centuries (7th–9th c.) the elite wasArab or at least thoroughly Arabicized and the people accepted Arabic only slowly andfor a long time still continued to compose, narrate and communicate in the old ‘pre-Islamic’ languages, the situation changed fundamentally from the tenth century onward.Now the ruling class often had an insufficient command of Arabic, and occasionallyneeded an interpreter to communicate with their administration, while the peoplebecame predominantly Arabicized from the twelfth century onward. In view of the lackof interest and also the linguistic incompetence of the elite, who often belonged to themilitary class, literature in Classical Arabic, which had flourished in the previous centu-ries, lost an important economic and cultural basis in the courts. At the same time thecreative power of Arabic popular literature was greatly boosted. The time of Islamicsynthesis had arrived (Heath 1990: 424).

From the ninth and tenth centuries onward, in addition to the popular legends ofthe prophets and the tales of conquests, there flourished various types of folktales likethe Arabian Nights, a collection of tales that gained world-fame in Europe but was longlooked down upon in the Arab world on account of its popular nature.³⁵ We also find

Thomas Herzog634

³³ Brockelmann 1943–49: I, 142 (margin no. 136).³⁴ This process of standardization also comprises lexical and syntactic changes which the Bedouin

poetic language underwent when it developed to become the cultural and administrative languageof an empire in the first/seventh and second/eighth centuries.

³⁵ See Littmann 1960; Gerhardt 1963; Miquel 1977 and 1981; Mahdī 1984–94 and 1995.

popular poetry that freed itself, at least partially, from the metrical rules of ClassicalArabic poetry (Heath 1990:434). In the period beginning with the eleventh/twelfthcentury, on the stage of popular narrative a predominant role was played by the genreof the oral sīra (plural siyar), a popular pseudo-historical heroic tale about the biographyof the main protagonist.³⁶ This exceedingly productive genre can with some justificationbe seen as a synthesis of (mostly) Arabic narrative material with a form that wasimported from the Iranian area, an area that had once again become linguistically andpolitically independent of the Arab world. Both before and after Islamization, Iran had aflourishing tradition of popular heroic narratives,³⁷ of which some are also known inArabic versions – such as Sīrat Fīrūz Shāh (The history of Fīrūz Shāh)³⁸ and Qis.s.atBahrām (The tale of Bahrām).³⁹ Apart from the synthesis of form, these popular siyaralso represented a synthesis of content with regard to Islamic and Islamized cultures;they provided a kind of survey of almost the entire Islamic and pre-Islamic culture,which was now common to all Muslims. At times they engaged in a process of sortingout the transmitted heritage, of ordering and evaluating it anew, and of mentally separ-ating the traditions worthy of preservation from those that did not conform to the Isla-mic order. The popular siyar at first creatively continued the form and spirit of theirpredecessors; later, however, the newly composed siyar themselves became models fornew tales about the more recent past, for which there were no exemplars in Old Arabianor non-Arab history. The ayyām al-‘arab and futūh. narratives were thus continued (withthe addition of the originally Iranian episodic, often cyclically expanded heroic biogra-phy) in the Sīrat az-Zīr Sālim, the Sīrat ‘Antara b. Shaddād and the Sīrat Dhāt al-Him-ma. The Sīrat az-Zīr Sālim and the Sīrat ‘Antara b. Shaddād are continuations of theayyām al-‘arab narratives about the so-called Basūs war between the tribes of the Bakrand the Taghlib.⁴⁰ The historical ‘Antara of the Sīrat ‘Antara b. Shaddād was one of theauthors of the poems that were suspended on the Ka‘ba on account of their poetic qua-lities (mu‘allaqāt, see above); elements of pre-Islamic history were hence preserved in thischaracter. The Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma (wa-Bat. t.āl), on the other hand, treats of tribalfeuds and the jihād on the border of Syria/Mesopotamia and the Byzantine Empire atthe time of the Umayyads (7th–8th c.) and the Abbasids (8th–13th c.).⁴¹ It continues inan entirely pseudo-historical way the genre of the futuh. in the form of the popular

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 635

³⁶ Surveys of scholarship on the siyar are found in Canova 1977; Heath 1984; Canova 2003b; andHerzog 2006:5–10. Easy access to the contents of the most important siyar is provided by Lyons1995.

³⁷ On Iranian epic, see Rypka 1968:44–45, 151–166 and 617–648. See also Hanaway 1970. [See alsoch. 25 on medieval Persian epic and narrative by J. Rubanovich in this volume.]

³⁸ This tale deals with early Iranian history; its main hero is the son of the Achaemenid king Darius II.See Grant 2003

³⁹ Also called Qis.s.at Bahrām Gūr. The action takes place in the time of the Sassanian dynasty. SeeHanaway 1974; Pantke 1974. The Sīrat Iskandar, the popular romance of Alexander the Great, doeslikewise not orignate in an Arabic milieu. See Doufikar-Aerts 2003 [and also in ch. 25 ( J. Rubano-vich) pp. █–█.].

⁴⁰ On the Sīrat az-Zīr, see Oliverius 1965 and 1971; Gavillet-Matar 2005. On the Sīrat ‘Antara b.Shaddād, see Norris 1980; Heath 1996; Herzog 2005; see also Cherkaoui 201a and 2001b.

⁴¹ On the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, see Steinbach 1972 and Ott 2003. The text has been edited inseventy parts in Cairo (see Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma).

heroic legend.⁴² One of the other conquest siyar that have their basis in an Arab tribalmilieu is the decidedly popular Sīrat Banī Hilāl (or Sīra hilālīya). The Sīrat az-Zīr Sālim,mentioned already, serves as its ‘prologue’; here, as in the ayyām al-‘arab narratives, wefind the formation of legendary cycles, into which several, originally independent tradi-tions are woven to form one great narrative. This narrative has as its subject the forcedemigration of the Banū Hilāl from the Arabian Peninsula and their move to the west toMorocco (which took place in the eleventh century).⁴³ Although the Sīrat Saif b. DhīYazan does not have its origin in history, it does use South-Arabian legendary traditionsas they were collected by men likeWah. b b. al-Munabbih as a background to its colourfultale, packed with demons and witchcraft (Paret 1924). One of the reasons for seeing an‘Islamic synthesis’ in these popular Arabian siyar is that some of their pre-Islamic, inreality pagan Arab heroes – such as ‘Antara b. Shaddād and Saif b. Dhī Yazan – are re-interpreted as forerunners of the Prophet Muh. ammad (Paret 1927: 12–13). The figureof ‘Antara b. Shaddād – the son of an Abyssinian slave-girl and an Arabian sheikh, whohas fallen in love with his cousin ‘Abla and has to fight for a long time to be acknowl-edged as a free warrior – illustrates the process of sifting and re-arranging the inheritedtraditions. The Sīrat ‘Antar begins with a long auctorial passage in which the contrastbetween ‘Antar, who has paved the way for Islam, and his enemies, who persist in theirpagan vices, is underlined:

[We are told of] the courageous bedouins of pre-Islamic times (‘urban al-jāhilīya ash-shuj‘ān),how they adored false gods and how they retreated full of veneration to idols and oracleshafts. The Devil (ash-shait.ān) had led them astray […]. Every one of them wanted to beesteemed alone of all the world – the brave among them were fervently hated. They did notfear God and did not seek his nearness; they had no awe of him and did not hold him inrespect.When God, however, wants to destroy a people he lets pride and arrogance enter theirhearts. Then he humiliates them, subdues them with the help of the lowliest and despisesthem. This is easy for him. This he did with the help of the slave […]. ‘Antar b. Shaddād, whoin his time was like a spark that sprang from kindling wood. Through him God subdued thetyrants at the time of ignorance (al-jabābira fi zaman al-jāhilīya), so that he [‘Antar] mightpave the way for the coming of your lord Muh. ammad, the noblest of men. (Sīrat ‘Antara: I,3–4)

This contrast is repeatedly mentioned throughout the epic. ‘Antar and his friends areshining examples of the Bedouin ideals; he is the protector of the poor, the weak andthe women; he is generous, brave and lofty, filled by a true sense of honour. His enemies,however, accord to the negative stereotype of the pre-Islamic bedouin: they are selfishtyrants, who hate the courageous and the noble and again and again resort to treacher-ous tricks in battle. The words, too, which the narrator puts in the mouths of ‘Antar’senemies are meant to show that they have fully submitted to the spirit of paganism.They repeatedly swear by the pre-Islamic deities, something that ‘Antar never does; even

Thomas Herzog636

⁴² On the parallels in Digenis Akritis, see Grégoire and Goossens 1934. [See also ch. 17 on medievalGreek epic poetry by E. Jeffreys in this volume.] The Sīrat Hamza is also a jihād narrative; it tellsthe story of Hamza b. ‘Abd al-Mut. allib, the Prophet’s uncle (see Qis.s.at H. amza; Meredith-Owens1986).

⁴³ The Sīrat Banī Hilāl has been well researched; see, inter alia, Pantůček 1970; Saada 1985; Connelly1986; Slyomovics 1987; Galley and Ayyub 1983; Nacib 1994; Reynolds 1995.

his mother swears by ‘the one and only [God], by him who has ordered dawn to light upin the sky’.⁴⁴ In addition, a certain parallelism between ‘Antar and the Prophet is devel-oped. Like the Prophet, ‘Antar causes offence to his tribe by his conduct and is rejectedby some of the influential members of his tribe. ‘Antar, too, questions the pre-Islamicorder, not by preaching a new religion which introduces new social norms, but by hisdemand to be recognized as a fully free Arab, even if he is the fruit of a union that is notlegitimized through the marriage of freeborn partners and although the colour of hisskin is black. Like the Prophet, ‘Antar emigrates from his tribe and temporarily fightsagainst it until he is finally recognized and can return. When one thinks of the enor-mous impact of the Prophet’s biography on the Islamic world, this parallel is not surpris-ing; it underscores once again the Islamic character of the narrative material and of thetale itself. In a further development of the siyar genre, the ‘urban’ siyar, which were com-posed shortly before and during the Mamluk period, leave the Arab tribal milieu: theSīrat al-H. ākim bi-Amrillāh, whose plot is centred on the Fatimid caliph H. ākim bi-Amrillāh (r. 386/996–411/1021); the Sīrat al-Malik az.–Z. āhir Baybars, which untilrecently was extremely popular;⁴⁵ and smaller cycles on Ah.mad ad-Danaf and ‘Alī az-Zaibaq, two clearly untypical protagonists.

In the Arabic East (Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Iraq), the places where the popular siyarwere performed prior to the Ottoman period (before the sixteenth century) were in allprobability the same as those where the qus.s.as. had recited their works at an earlier time:in front of the mosque, in the h. ammām (public bath), on public squares and streets andduring the men’s social gatherings in the evening. Al-Maqrīzī (d. 845/1442) reports thatduring the fifteenth century groups were to be found in the evenings on Cairo’s most-frequented thorough-fare of the time, the Khat. t. Baina al-Qas. rāin, in which the siyar undakhbār were recited and other kinds of entertainment provided:

When the days of the Fāt. imids were coming to an end […] this place turned into a bazaar[…], a promenade where the nobles and their like walked on foot in the evening to see theenormous multitude of candles and lanterns and everything that men long for and thatdelights their eyes and gladdens their senses. There used to sit a number of groups, wheresiyar, akhbār and poems were recited and where all kinds of games and pastimes wereindulged in. There was such a crowd in this place, whose number cannot be calculated andwhich can be neither related nor described. (Maqrīzī: 1853–54: II, 28, lines 18 ff.)

From the sixteenth/seventeenth centuries onward, the siyar were probably recited moreand more in the simple coffee-houses of the common people. For the eighteenth andnineteenth centuries, at any rate, we have, from the descriptions of European travellersand from Arabic sources, ample evidence of the style of these coffee-house narrators,who performed the siyar into the 1960s in Syria and Egypt. The ‘Encyclopedia of theTrades of Damascus’, the German Carsten Niebuhr, who travelled in the service of theking of Denmark, the authors of the Description de l’Égypte and the Englishman E.W.

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 637

⁴⁴ Sīrat ‘Antar b. Shaddād, Paris, BnF MS arabe 3790, fol. 113b, line 1.⁴⁵ On the Sīrat Baybars, which has been well researched, see Wangelin 1936; French translation by

Bohas and Guillaume 1985 ff., as well as number of articles by Bohas, Guillaume, and Herzog (seethe bibliography in Herzog 2006); Vidal Luengo 2000; Garcin 2003; Zakharia 2004; and thedetailed monograph Herzog 2006.

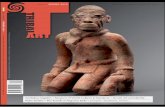

Lane give us an essentially identical picture:⁴⁶ the popular narrators patronize the coffee-houses in order to recite the popular siyar to the guests from a raised seat, with or with-out the rabāba, a one-stringed fiddle. As Lane writes:

Reciters of romances frequent the principal kahwehs (or coffee-shops) of Cairo and othertowns, particularly on the evenings of religious festivals, and afford attractive and rationalentertainments. The reciter generally seats himself upon a small stool on the mas. t. abah, orraised seat, which is built against the front of the coffee-shop: some of his auditors occupythe rest of that seat, others arrange themselves upon the mas. t. abahs of the houses on theopposite side of the narrow street, and the rest sit upon stools or benches made of palmsticks;most of them with the pipe in hand; some sipping their coffee; and all highly amused, notonly with the story, but also with the lively and dramatic manner of the narrator. The reciterreceives a trifling sum of money from the keeper of the coffee-shop, for attracting customers:his hearers are not obliged to contribute anything for remuneration: many of them give noth-ing; and few give more than five or ten fad. d. ahs.⁴⁷

24 – ‘A Shá’er, with his accompanying Violist, and part of his Audience’ (Lane, p. 393)

Thomas Herzog638

⁴⁶ See Qāsimī 1960, 112–14; Niebuhr 1772:106–7; Panckoucke 1826:161–62.⁴⁷ Lane 1860:391. Compare Kremer 1863: II, 305–6.

The performance sometimes assumed theatrical traits. According to the information ofthe late owner of the Damascus coffee-house an-Nawfara, Ah.mad ar-Ribāt. /Abū S·ālih. ,some narrators ran up and down in the coffee-house and, with a helmet on their headsand a wooden sword in their hands, imitated the actions of the heroes (Aswad 1990:59).The h. akawātī (narrator) Abū Ah.mad al-Mun‘ish is said to have recited the Sīrat al-Mal-ik az. -Z. āhir Baybars by heart and in dialect and to have imitated the protagonists’ way ofspeaking, while walking from one end of the coffee-house to the other. Despite his greatage, Abū Ah.mad al-Mun‘ish rushed on the imaginary enemies of his hero and‘destroyed’ them with his wooden sword.⁴⁸ Often the coffee-house narrators would recitetheir texts freely or use a manuscript merely as a memory aid.⁴⁹ Only the Sīrat ‘Antar,which is predominantly composed in Classical Arabic and therefore occupies a specialposition, was apparently regularly read from manuscripts. There was no lack of coffee-houses in which narrators were active, although perhaps not all coffee-houses have nar-rators, as the ‘Encyclopedia of the Trades of Damascus’ maintains (Qāsimī 1960:112).According to Johann Gottfried Wetzstein, the Prussian consul in Damascus, in the1860s the Sīrat Baybars alone was recited every evening in three dozen coffee-houses;Seetzen speaks of thirty narrators in Cairo in 1809, while Lane assumes the existence ofabout one hundred narrators in the Cairo of the 1820s and 1830s.⁵⁰ Lane distinguishesthree groups of narrators, decreasing in number: about fifty narrators of the Sīrat BanīHilāl, called shu‘arā (poets), who are accompanied by the rabāba and chant the versesfrom memory (1860: 392); about thirty muh. addithīn (storytellers), who recite the SīratBaybars – a work ‘written in the most vulgar style of modern Egyptian Arabic’ – frommemory and without instrumental accompaniment (400); finally about six ‘antarīya,who recite the Sīrat ‘Antar from a book. Lane adds that the inserted verse passages werechanted, while the prose was read ‘in the popular manner’. In addition to the Sīrat‘Antar, which was only imperfectly understood by their audience, the ‘antarīya also per-formed the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, the Sīrat Saif b. Dhī Yazan and sometimes too AlfLaila wa-Laila, the Arabian Nights (414). According to Niebuhr, who travelled in Syriaand Egypt during the second half of the eighteenth century, the adventures of RustāmZāl, a Persian hero from the Shāh-nāma, the history of the Ayyūbids and the tale of Bah.lūl-dāne, a clown at the court of Harūn ar-Rashīd, were also told in the coffee-houses(1772:106–7). There is no reason to doubt that the repertoire of these narrators com-prised also the Romance of Alexander, other siyar sha‘bīya (popular siyar) and all kindsof tales. Niebuhr calles the narrators ‘poor scholars (Mullâs)’, which indicates their socialorigin (107). Some of the Syrian narrators of the late nineteenth and the twentieth cen-turies, whose traces I have followed in an earlier study, come from both a poor and an

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 639

⁴⁸ Aswad 1990:61. The term h. akawātī (pl. h. akawātīya) is used for popular narrators in Syria.⁴⁹ Such a memory aid is, e. g., the manuscript Ahlwardt 1896, no. 9164 (Spr 1355) of the Sīrat Bay-

bars; see Herzog 2006:33, 432 and 437. In al-Budayrī῾s local chronicle H. awādith Dimashq al-yau-mīya from the eighteenth century we read about the h. akawātī Sulaimān al-H. ashīsh, who told theSīrat az. -Z. āhir, the Sīrat ‘Antara, the Sīrat Saif and curious anecdotes from Turkish and Arabic(nawādir gharība min at-turkī wa-l-‘arabī), although he was illiterate. Budayrī 1959:43.

⁵⁰ Wolff 1864. – Seetzen is said to have been informed by the sheikh of narrators in 1809 that ‘inKahira there are thirty public narrators under him’ (Wangelin 1936:307–8, where unfortunately nosources are given).

uneducated background (Herzog 1994:19–21). Abū l-H. ann, a h. akawātī from Aleppo,was a demobilized soldier of the Ottoman Empire, who earned his living as a narratorafter his return to his home town in 1920, an occupation that he followed until 1960.⁵¹Abū ‘Alī Shāhīn, who was active in Damascus coffee-houses from 1890 until 1920,worked in the sericulture trade and his colleague Abū Ah.mad al-Mun‘ish was a sweetsvendor during the day. By their performances in the evening they supplemented theirincome (Aswad 1990: 57, 61).

The siyar were not only publicly performed in the coffee-houses, they were also readprivately; people would frequently borrow a written version from a scribe or manuscriptlender (warrāq) either to read the sīra on their own or to read it out aloud in a circle offamily, friends and acquaintances. These private readers were persons who were unableto assist the narrators’ recitals in popular coffee-houses on account of their social posi-tion or their sex, or who were living away from the towns and had no coffee-houses withsiyar performances in their vicinity. In my study of the manuscripts of Sīrat Baybars inthe possession of Abū Ah.mad, I was able to show on the basis of readers’ annotations inthe manuscripts that a number of them were used for reading and reciting in the villagesaround Damascus in the first half of the twentieth century (Herzog 1995:66–80).

Like the popular maghazī and futuh. narratives, the popular siyar were put intowriting at a very early time. On the one hand this was done to preserve an exception-ally successful version as a model for future narrators.⁵² Having a siyar in written formmade it possible, on the other hand, to enjoy the stories as a private reader. From asearly as the twelfth century we have two accounts by doctors who in their youth read(and also copied) stories (ah. ādith) about ‘Antara b. Shaddād. Thus the physician andminor poet Abū al-Muʾayyad Ibn as.–S·āʾigh, who lived in the middle of the sixth/twelfth century, earned his bread in his younger years by copying ah. ādīth of ‘Antar.⁵³In the same period, the Bagdad physician and mathematician as-Samawʾal Ibn Yah.yaal-Maghribī (d. c. 575–76/1180) mentions in his autobiography that between the agesof ten to thirteen he loved to read stories and tales of past centuries, long poems andlegends, like the tales about ‘Antar, Dhāt al-Himma wa-l-Bat. t. āl, Alexander the Great,al-‘Anqāʾ, at.–T.araf b. Lūdhān and others (Schreiner 1898: 127). The fifteenth-centurywriter as-Sakhāwī (830(1427–902/1497) tells a story about the miller Khalīl fromnear the Bāb al-Qarāfa in Cairo who possessed a number of notebooks (kurrāsa) ofthe Sīrat ‘Antar and the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma as well as tales about the great Arabhero ‘Amr b. al-‘Ās and about the Prophet’s companions. Khalil, as-Sakhāwī writes,gave these notebooks to Sheikh Badr ad-Dīn Sharabdār, a famous popular preacher, tobe recited to a paying audience, which the latter, however, declined for unknown rea-sons. This story about a miller shows that the popular siyar, maghāzī and futūh. also

Thomas Herzog640

⁵¹ Interview with Muh. ammad Yah.yā H. amawī, Aleppo, 5 February 1994 (by Thomas Herzog).⁵² Nevertheless the transmission of the siyar basically takes place orally. The manuscripts of the Sīrat

az-Zīr Sālim and the Sīrat Baybars, for instance, document that orality frequently played a role inthe transmission of these siyar. It can be shown that some of these texts are dictated texts; M.Gavillet Matar (2005:70) has identified cases of phonetic orthography that have arisen thanks todictation in a Berlin manuscript of the Sīrat az-Zīr Sālim. Some texts have clearly been writtendown from memory, probably going back to an oral performance; see Herzog 2006:147.

⁵³ Yaktubu: probably in the sense of ‘copy’. Ibn Abī Us. aybi‘a 1884: II, 290–97.

circulated among tradesmen.⁵⁴ Most of the extant manuscripts of the popular siyardate from the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries;⁵⁵ some siyar have beenpreserved in manuscripts from the twelfth century.

All popular siyar share a number of characteristics. They are generally anonymousproductions, with no known author, despite their attribution to famous authors, as withthe popular futuh. narratives. They are composed in a kind of kunstsprache, an idiom, inwhich elements of Classical Arabic are combined with traits of colloquial Arabic.⁵⁶Although in terms of plot the siyar are situated in a popular milieu, they contain oftenintertextual references, not only to other popular maghāzī, futūh. and siyar, but also toscholarly works, for instance in the field of historiography.

This shows that men of a certain level of education were also involved in the com-position and transmission of these siyar, a fact that contradicts the widely held thesis ofthe purely popular character of this type of literature.⁵⁷ The authors/ redactors/ narra-tors of the popular siyar often rely greatly on a limited number of narrative patterns andmotifs, which they combine ever anew with the plots and figures of the narratives.⁵⁸ As arule, the siyar are divided into episodes; these sometimes have a title in the manuscripts,and form self-contained units.⁵⁹ As is true of most anonymous popular epic tales, thereare as many versions of a sīra as there were performances. Even in the frequent casewhen a sīra was not fully recited from memory, the recital from manuscripts neverthelessleft room for free invention. The siyar finally developed into extended narratives with atendency to form cycles of tales. Many siyar are characterized by a large number ofstereotypical expressions; furthermore, the language of the passages in rhymed prose(saj‘) is highly formulaic.⁶⁰

The formulaic nature of the passages in rhymed prose in the popular siyar points tothe hybrid oral-written character of the siyar transmitted in manuscripts. As Claudia Otthas shown in connection with the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, the medium of these texts is, ofcourse, writing, while their conceptualization is mostly due to orality, but also to lit-eracy.⁶¹ The oral theory developed by Parry and Lord in connection with the Homeric

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 641

⁵⁴ See Sakhāwī 1934–36: VII, 224–25 (quoted from Shoshan 1993:350).⁵⁵ They have often found their way into the archives of European libraries. For the Sīrat Baybars, see

Herzog 2006:31 ff.⁵⁶ This variety of Arabic is often termed ‘Middle Arabic’; see Fück 1950:57–62; Blau 1966–67: pas-

sim. I try to avoid this term, because it suggests a developmental stage in the history of Arabic (aswith Middle High German, Middle English etc.), which does not apply, however, to the diglossicsituation of Arabic.

⁵⁷ On the intertextuality fo the Sīrat Baybars and learned Arabic historiography, see Herzog2006:358–92.

⁵⁸ This trait is typical of popular improvised tales, in which within the framework of a basic plot, thenarrator builds new episodic adventures for his heroes from a limited number of linguistic andnarrative units.

⁵⁹ The episodes in the popular siyar can be compared to the episodes of a television serial; on thewhole they form complete stories which can be understood even by an infrequent listener whoknows only the basic plot and the main characters of the narrative.

⁶⁰ On the formulaic character of the passages in rhymed prose in the manuscript of the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, see Ott 2003:141 ff. On the Sīrat Baybars, see Herzog 1994 and Guillaume 2004.

⁶¹ On the difference between the conceptual and medial aspects of orality, see Raible 1994 and Kochand Oesterreicher 1994.

epics and South Slavic heroic poetry cannot be applied mechanically to the Arabic siyar:the texts have not been composed purely orally, but rather in an interplay of orality andliteracy, both in creation and transmission; and almost all siyar, with the notable excep-tion of the Sīrat Banī Hilāl,⁶² are in prose or rhymed prose rather than in verse.⁶³ Thereis nevertheless a justification for applying the oral theory to the Arabic popular siyar.The passages in rhymed prose in the siyar are characterized by a high incidence of for-mulas, as shown by Ott in the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma and by Guillaume in the SīratBaybars, which leads to the conclusion that the written text reflects an original orality.These formulas do not usually advance the action, but are rather found in descriptionsor at turning-points of the narrative. Ott has pointed out the presence of formulas in theSīrat Dhāt al-Himma at places where the times of the day are indicated, where land-scapes or the beauty of a man, woman or horse are described, where the sudden arousalof fear, surprise, anger or joy is expressed and where battles and fights are depicted. Thedescriptions of battles are in their entirety formulaic to such a degree that they can becalled ‘themes’ in the terminology of the oral theory (2003:145). A brief example is thedepiction of dawn, which is identically expressed in the Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma studied byOtt and in the Sīrat ‘Antara b. Shaddād, in the Sīrat Baybars and without doubt also inother popular siyar:

fa-lamma as. bah. a s.–s. abāh.wa-ad.ā‘a bi-nūrihi wa-lāh. […]

and as morning dawned/ and shone and gleamed with its light […]⁶⁴

With reference to four siyar (Sīrat ‘Antara, Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, Sīrat az-Zīr Sālim andSīrat Banī Hilāl), Madeyska was able to show that in addition to fixed formulas there aremore often variable formulas which consist of keywords and variable words for whichsynonyms can be substituted. For the concept ‘to be killed’, for examples, the followingvariable formula is found:⁶⁵

saqā/asqā/sharibakaʾs

al-h. imām/ar-radāl/al-‘at. ab/al-mahālik/al-maniyyāt/at-talaf/al-ajal

The keyword is kaʾs ‘cup’ (underlined in the middle), the formula is ‘to drink the cup ofdeath’, where ‘to drink’ can be replaced by ‘to give to drink’ (saqā) or ‘to sip’ (asqā, shar-iba) and ‘death’ (al-h. imām) by synonyms such as ‘destruction’, ‘doom’ etc. (ar-radāl etc.).

Thomas Herzog642

⁶² Until the recent past and partly until today, wandering bards (called shā‘ir) recited the Sīrat BanīHilāl from memory in the villages of Upper and Lower Egypt. Although their performance is basedon a memorized text, every performance creates a new text with the help of previously acquiredformulas, themes, and narrative patterns. On the performance of the Sīrat Banī Hilāl in Egypt, see,inter alia, Connelly 1986; Slyomovics 1987; Reynolds 1995; on Algeria, see Nacib 1994. See alsothe ‘Sirat Bani Hilal Digital Archive’ (edited by D. Reynolds) at ‘http://www.siratbanihilal.ucsb.edu/’.

⁶³ See Guillaume 2004:56–58, and Ott 2003:144. On the question of whether the siyar can be called‘epics’ comparable to the texts that formed the basis of Parry’s and Lord’s theory, see below, p. █.

⁶⁴ See Ott 2003:145, and Guillaume 204:59.⁶⁵ Madeyska 1993:52 (quoted in Ott 2003:149).

The beginning of a new episode is also stereotypically formulaic. In the Sīrat Baybars, thenew episode, after mentioning the calm and stability at the end of the previous episode,almost always starts with the words:

ilā an kāna yawm min al-ayyām / kāna l-malik jālis / fī s. adr al-majālis / yaqz. ān ghair nā‘is […](Guillaume 2004:60)

Until one of these days / the king was sitting / at the head of the council, / fully awake andnot sleepy […]

Also formulaic are the passages that describe the orally conceived rituals of the coffee-house performance in the manuscript texts (Ott 2003: 155–60). They comprise thenaming of the narrator, the qālā r-rāwī formula (the narrator said), which occurs at thenarrative’s intersection points (qāla r-rāwī/qāla n-nāqil, yā sāda ya kirām); calls to prayerwith the so-called s.allū formula, a blessing of the Prophet (s.allā llāhu ‘alā nabīyyinā Muh.ammad, s.allā llāhu ‘alaihi wa-sallama), with variants; appeals to the audience to listen(ayyuhā s-sāmi‘ […], ‘O listeners […]’); the basmalla formula, the ritual expression bismil-lāh (in the name of God); finally the night formula, which refers back to the narrativesituation and which is always used when the recital is interrupted, generally at a particu-larly dramatic point in the narrative: wa-l-lail amsā wa-tamām al-h. adīth fi-l-juzʾ illī(alladhī) warā’uhu, ‘Night has come on and the continuation follows in the next part.’Finally, all siyar passages containing direct speech are lexically, morphologically and syn-tactically very close to dialect and colloquial speech. Here the attempt to transfer oralspeech into the written medium is most noticeable (Ott 2003: 151).

So much for the dominance of conceptual orality in the manuscripts of the siyar.The siyar in manuscripts (and, from the end of the nineteenth century, in numerousprinted editions) also exhibit the opposite phenomenon, i. e. conceptual literacy: theendeavour, in terms of style and self-presentation, to approach as closely as possible themodel of learned historiography, written in Classical Arabic. Examples of this are thefrequent hypercorrect passages, which demonstrate the (failed) effort to employ an eru-dite manner of writing, and above all the choice of words, which are meant to provethat the sīra in question is a text that has been collected, compiled, transmitted, writtendown and copied according to the established scholarly norms.⁶⁶ All the siyar with whichI am familiar contain an attribution to a learned transmitter, redactor or author. TheSīrat ‘Antara b. Shaddād, for instance, states at its very beginning that the famous poly-grapher al-As.mā‘ī (d. 213/828) was one of the rāwīs of this sīra. The text underlines itstrustworthiness by identifying him as one of the transmitters of the h. adīths of the Pro-phet Muh. ammad.⁶⁷ After citing several other canonical h. adīth-transmitters and claimingthem to be authors of the sīra, the text affirms that each of them transmitted (rawā)what he saw (mā shahida) […] and what he had heard from trustworthy people whowere present at the (pre-Islamic) Bedouins’ battles.⁶⁸ The text of the Cairo edition ofSīrat Baybars claims in a very similar way to be based on the eye-witness report (mā

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 643

⁶⁶ See the examples in Ott 2003:163–68.⁶⁷ Wa-huwa min jumlati man rawā l-h. adīth ‘an rasūli l-lāh. Qis.s.at ‘Antara: 5.⁶⁸ Wa-sami‘a ‘amman yūthaqu bihi mimman h. ad. ara waqā‘ia al-‘urbān. Qis.s.at ‘Antara: 5–6.

shāhadūhu wa-mā ‘āyanūhu) of the ‘renowned noble scholars’ ad-Dīnārī and ad-Duwai-dārī and on what they learned from other trustworthy sources.⁶⁹

This attribution to a learned authorship brings us back to the break which hadoccurred with the writing down of the Qurʾān and with the formation of a written,educated literature in the Classical language by an elite that had the monopoly of defin-ing what was to be counted as truth and what as a lie. The criticism of the Prophet’sadversaries that his preaching was nothing but poetry, led pre-modern Arab scholars topostulate a contrast between learned, serious, allegedly factual and popular, allegedlynon-factual narratives and to characterize the latter as lies.⁷⁰ Learned scholars in Arab-Islamic culture often vigorously denounced the imaginary world of storytelling, espe-cially when it touched on the field of history. These scholars often characterized suchstories as mere inventions or dangerous lies which do not serve God and waste the timeof the believers,⁷¹ and then juxtaposed them with trustworthy accounts in the officialhadith and historiographical traditions.⁷² In order not to be condemned in this way, thecomposers of the siyar passed their works off as the texts of great scholars, as historiogra-phical scientific accounts rather than fictional epic narratives. Unlike listening to popu-lar fairytales or texts like the Arabian Nights, pre-modern Arab listeners and readers ofsiyar simply could not understand these texts as works of imagination, since they weretrapped by the implicit prohibition on invention or the propagation of fictional eventsand persons, especially if they were meant to relate closely to the history of the umma,the Muslim nation. Arab pre-modern audiences had to perceive the narratives either asmore or less true accounts about the past or as more or less sophisticated lies, or as anintricate mixture of both. Even if some audiences may have more or less consciouslyexperienced the storyteller’s historical narration as a moment of playful imagination situ-ated in the forbidden no-man’s-land where truth and lies cohabit, pre-modern Arabicsociety could not overtly articulate their pleasure, but had to conceal it and pretend thatthey were listening to serious, truthfully transmitted, educational accounts of history. Ina typically elitist stance, Rudi Paret denied the popular futuh. narratives their qualifica-tion as epics, precisely because of their guise as historiographical accounts and their ‘lowartistic level’ (an appraisal basically also applicable to the siyar).⁷³ With this opinion he

Thomas Herzog644

⁶⁹ As-sādāt al-kirām al-mashhūrīn bi-l-‘ilm wa-‘ulwi l-maqām ad-Dīnārī wa-d-Duwaidārī wa-mānaqalūhu min as-sāda min ikhwānihim al-ladhīna ya‘timidūna min kalāmi s.–s.idq ‘alaihim. Sīrat al-Malik al-Z. āhir: 10–11; practically identical to Paris, BnF MS arabe 4981, fol. 1b–2a.

⁷⁰ The following remarks on fiction and Arabic siyar are taken from Herzog 2010.⁷¹ The famous Tāj ad-Dīn as-Subkī (d. 771/1370) wrote: ‘The copyists have the duty to keep away

from copying books that do not serve God, such as the Sīrat ‘Antar and various other works ofimagination, which waste your time and which are of no use to religion.’ ‘Al-kutub al-latī lā–yanfa‘allāh bihā ka-Sīrat ‘Antar’ (Myhrman 1908:186).

⁷² At the end of the fifteenth century, the faqīh al-Wansharīsī (d. 1508) cites the fat.wa of one of hiscolleagues, Ibn Qad.d.āh. , who stated that it was forbidden to sell the popular siyar and other narra-tives of notoriously untruthful character. A reader of the Sīrat ‘Antar could neither be an imām, nora witness in court, because he was incapable of distinguishing truth from lies. A person believing liesof that kind, should be considered a liar himself or herself. Grunebaum 1963: 573, note 73. Grune-baum cites Peres 1958:33.

⁷³ ‘An sich würde manches für eine positive Antwort [auf die zuvor gestellte Frage: “Kann die legen-däre futūh. -Literatur als arabisches Volksepos bezeichnet werden?” T. H.] sprechen. Der Gegenstand,die arabisch-islamischen Eroberungen, bietet sich als Stoff zu einem Epos sozusagen von selber an.

misses the peculiar Arabic tension between orality and literacy and between official,learned, ‘true’ narration in the standard language and unofficial, fictional, ‘lying’ narra-tion in the colloquial vernacular. In a culture of parallel orality and literacy, it is essentialthat, in order to effectively defend in learned circles the claim of truth for its canonicaltexts (which are of ultimately oral origin), all competitive storytelling about one’s ownhistory must be looked down upon, and even, if possible, forbidden and nipped in thebud. Next to the Qurʾān and the official maghāzī, futūh. and qis.s.as. al-anbiyāʾ narratives,therefore, no epic, explicitly so named, could be tolerated. If epic, however, is understoodas defined above (p. █), then the Arabs have known oral epic compositions and narra-tives from the earliest period onward.

References

Ahlwardt,W. 1896. Die Handschriften-Verzeichnisse der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin. Verzeich-niss der arabischen Handschriften. Vol. 8. Berlin. 1896.

Arberry, Arthur J., trans. 1964.The Koran Interpreted. London: OUP.Assman, Jan. 1997. Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen

Hochkulturen. Munich: Beck.Aswad, Nizār al-. 1990. ‘Al-h. akawātī fī Dimashq.’Al-Maʾthūrāt ash-sha‘bīya 18:56–63.Berkey, Jonathan Porter. 1992.The Transmission of Knowledge in Medieval Cairo: A Social History

of Islamic Education. Princeton: Princeton UP.Blachère, Régis. 1952–66. Histoire de la littérature arabe des origines à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. 3

vols. Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve.Blau, Joshua. 1966–67. A Grammar of Christian Arabic, Based mainly on South-Palestinian Texts

from the First Millenium. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 267, 276, 279. 3vols. Louvain: Secrétariat du Corpus SCO.

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 645

[…] Dazu kamen die Möglichkeiten im sprachlichen Ausdruck. Wie ich schon in anderem Zusam-menhang bemerkt habe, wäre im Arabischen ein Epos denkbar, das in sinnvollem Wechsel von denSprachformen der Prosa und der Reimprosa Gebrauch macht und durch Liedeinlagen in seinerinneren Struktur aufgelockert und akzentuiert wird.Aber Stoff und sprachliche Mittel allein reichen nicht aus, um ein literarisches Kunstwerk herzus-tellen. Dazu bedarf es vor allem der Genialität eines Künstlers. Und daran fehlte es. Die arabisch-sprachige Welt hat keinen Firdausi hervorgebracht. Die Literaten, die sich mit der Futūh.–Literaturabgaben und sie vor allem der breiten Masse mundgerecht und schmackhaft zu machen suchten,waren – sagen wir es unverblümt – kleine Geister. Mit ihrer Schwarzweißmalerei vertraten sie einprimitives Lebensgefühl, zu primitiv, um großartig zu sein, gradlinig und ungebrochen, aber ebendeshalb auch ohne innere Spannung. Von Tragik fehlt in der Darstellung jede Spur. Alles Gesche-hen verläuft an der Oberfläche. Die mangelnde Tiefe wird durch Quantität und Hypertrophieersetzt.Dazu kommt ein Weiteres. Der Verfasser oder Überlieferer hatte gar nicht die Absicht, dieGeschichte der arabisch-islamischen Eroberungen nur als Stoff zu benützen, um daraus ein litera-risches Kunstwerk zu schaffen. […] im Grunde genommen wollte er Historiker sein und als solcherernst genommen werden. Das beweisen die vielen in den Text eingestreuten Isnāde [Überlieferer-ketten zur Bezeugung der Wahrhaftigkeit des Überlieferten – analog zu den Prophetentraditionen:h. adīth; T. H.]. Unter diesen Umständen konnte sich die legendäre Futūh.–Literatur nicht zum Eposentwickeln. […] Sie ist weder Fisch noch Fleisch: einerseits Pseudohistorie, die als echte Historiegelten möchte, andererseits Dichtung, die sich selber nicht wahrhaben will und deshalb im Ansatzzur Entwicklung einer eigenen literarischen Gattung steckengeblieben ist.’ (Paret 1970:746–47) –Compare also Guillaume 1996.

Bohas, Georges, and Jean-Patrick Guillaume, trans. 1985 ff. Le Roman de Baïbars. 10 vols. to date.Paris: Sindbad.

Brockelmann, Carl. 1943–49. Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur. 2nd ed. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill. [2vols. supplement, 1937–42.]

Budayrī, Ah.mad ash-shaikh Ah.mad al-Budairī al- H. allāq. 1959. H. awādith Dimashq al-yawmīya.Cairo.

Busse, Heribert. 1987. ‘Arabische Historiographie und Geographie.’ In Gätje 1987: 264–97.Canova, Giovanni. 1977. ‘Gli studi sull’ epica popolare araba.’ Oriente Moderno 57:211–26.–, ed. 2003a. ‘Studies on Arabic Epics.’ Oriente Moderno n. s. 22 (83): v–xxi, 255–574 (second

issue).–. 2003b. ‘Twenty Years of Studies on Arabic Epics.’ In Canova 2003a: v–xxi.Caskel,Werner. 1931. ‘Aijām al-‘Arab. Studien zur altarabischen Epik.’ Islamica 4:1–99.Caton, Steven C. 1990. ‘Peaks of Yemen I Summon’: Poetry as Cultural Practice in a North Yemeni

Tribe. Berkeley: U of California P.Cherkaoui, Driss. 2001a. Le Roman de ‘Antar. Une perspective littéraire et historique. Paris: Présence

Africaine. 2000.–. 2001b. ‘The Pyramidal Structure in Arabic siyar: The Example of Sirat “Antar.”’Al-‘Usūr al-

Wustaa 13: 6–9.Connelly, Bridget. 1986. Arab Folk Epic and Identity. Berkeley: U of California P.Doufikar-Aerts, Faustina. 2003. ‘Sīrat al-Iskandar: An Arabic Popular Romance of Alexander.’ In

Canova 2003a: 505–20.Encyclopaedia of Islam. Ed. B. Lewis, C. E. Bosworth, P. J. Bearman et al. New edition. 12 vols.

Leiden: Brill, 1960–2004.Fahd, T. 1997. ‘Shā‘ir. 1. In the ArabWorld. A. Pre-Isalmic and Ummayyad Periods.’ Encyclopaedia

of Islam, IX, 225.Fück, Johann. 1950. ‘Arabīya.Untersuchungen zur arabischen Sprach- und Stilgeschichte. Abhandlun-

gen der Sächsischen AW zu Leipzig, Philologisch-Historische Klasse 45,1. Berlin: Akademie-verlag.

Galley, Micheline, and Abderrahman Ayoub, eds. and trans. 1983. Histoire des Beni Hilal et de cequi leur advint dans leur marche vers l’ouest. Versions tunisiennes de la Geste hilalienne. Paris:Colin.

Garcin, Jean-Claude, ed. 2003. Lectures du ‘Roman de Baybars’. Marseille: Parenthèses.Gätje, Helmut, ed. 1987. Grundriß der Arabischen Philologie. II. Literaturwissenschaft. Wiesbaden:

Reichert.Gavillet Matar, Marghérite, ed. and trans. 2005. La geste de Zīr Sâlim d’après un manuscrit syrien. 2

vols. Damascus: Institut Français du Proche-Orient.Gerhardt, Mia I. 1963.The Art of Storytelling: A Literary Study of the 1001 Nights. Leiden: Brill.Goldziher, Ignaz. 1920. Die Richtungen der islamischen Koranauslegung. An der Universität Upsala

gehaltene Olaus-Petri-Vorlesungen. Veröffentlichungen der ‘De Goeje-Stiftung’ 6. Leiden:Brill.

Grant, Kenneth. 2003. ‘Sīrat Fīrūzšāh and the Middle Eastern Epic Tradition.’ In Canova 2003a:521–28.

Grégoire, Henri, Roger Goossens. 1934. ‘Byzantinisches Epos und arabischer Ritterroman.’ ZDMG88: 213–32.

Grunebaum, G. E. von. 1963. Der Islam im Mittelalter. Zürich: Artemis. [Rev. translation of Med-ieval Islam: A Study in Cultural Orientation, 2nd ed. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1953.]

Guillaume, Jean-Patrick. 1996.‘Y-a-t-il une littérature épique en arabe?’ In L’épopée: mythe, histoire,société. Ed. J.-P. Martin and F. Suard. Littérales 19. Nanterre: Centre des sciences de la littéra-ture. 91–107.

–. 2004. ‘Les scènes de bataille dans le Roman de Baybars. Considérations sur le “style formu-laire” dans la tradition épique arabe.’ In Zakharia 2004: 55–76.

Thomas Herzog646

Günther, Hartmut, Otto Ludwig et al., eds. 1994. Schrift und Schriftlichkeit/ Writing and Its Use.Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch internationaler Forschung/ An Interdisciplinary Handbook ofInternational Research. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 10. Ber-lin: de Gruyter.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1925. Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Paris: Alcan.Hanaway, William L., Jr. 1970. ‘Persian Popular Romances before the Safavid Period.’ Ph. D. The-

sis. Columbia University, New York.Hanaway, William L., Jr., trans. 1974. Love and War: Adventures from the Fīrūz Shāh Nāma of

Sheikh Bīghamī. Persian Heritage Series 19. New York: Scholars Facsimiles and Reprints.Heath, Peter. 1984. ‘A Critical Review of Modern Scholarship on Sīrat ‘Antar ibn Shaddād and the

Popular Sīra.’ Journal of Arabic Literature 15: 19–44.–. 1990. ‘Arabische Volksliteratur im Mittelalter.’ In Neues Handbuch der Literaturwissenschaft.

Vol. 5. Orientalisches Mittelalter. Ed.Wolfhart Heinrich.Wiesbaden: AULA. 423–39.–. 1996.: TheThirsty Sword: Sīrat ‘Antar and the Arabic Popular Epic. Salt Lake City: U of Utah

P.Herzog, Thomas. 1994. ‘Présentation de deux séances de h. akawātī et de deux manuscrits de la Sīrat

Baybars recueillis en Syrie en 1994.’ Maîtrise d’arabe, sous la direction de Claude Audebert etde Jean-Paul-Pascual. Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence.

–. 1995. ‘Présentation, classification et analyse linguistique d’une collection de manuscrits de laSīrat Baybars.’ DEA d’arabe, sous la direction de Claude Audebert et de Albert-Louis de Pré-mare. Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence.

–. 2005. ‘Wild Ancestors – Bedouins in Mediaeval Arabic Popular Literature.’ In Shifts andDrifts in Nomad-Sedentary Relations. Ed. Stefan Leder and Bernhard Streck. Nomaden undSesshafte 2.Wiesbaden: Reichert. 421–41.

–. 2006. Geschichte und Imaginaire. Entstehung, Überlieferung und Bedeutung der Sīrat Baibarsin ihrem sozio-politischen Kontext. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

–. 2010. ‘“What they saw with their own eyes…” – Fictionalisation and “Narrativisation” of His-tory in Arab Popular Epics and Learned Historiography.’ In Fictionalizing the Past: HistoricalCharacters in Arabic Popular Epics. Ed. Sabine Dorpmüller. Cairo: American U of Cairo P.█–█.

H. usain, T. āhā. 1926. Fi-š-ši‘r al-ǧāhilī. Cairo.Ibn Abī Us. aybi‘a. 1884. ‘Uyūn al-anbāʾ fī t. abaqāt al-at. ibāʾ. Ed. A. Müller. 2 vols. Königsberg.Jacobi, Renate. 1987. ‘Die altarabische Dichtung (6.–7. Jahrhundert).’ In Gätje 1987: 20–31.Jacobi, Renate. 1995. ‘Rāwī.’ Encyclopaedia of Islam, VIII, 466.Koch, Peter, and Wulf Oesterreicher. 1994. ‘Schriftlichkeit und Sprache.’ In Günther, Ludwig et al.

1994: 587–604.Kremer, Alfred von. 1863. Ägypten. Forschungen über Land und Volk während eines zehnjährigen

Aufenthalts. 2 vols. Leipzig.Kurpershoek, P. Marcel, ed. and trans. 1994–99. Oral Poetry and Narratives from Central Arabia. I.

The Poetry of Ad-Dindan. II. The Story of a Desert Knight. III. Bedouin Poets of the DawāsirTribe. 3 vols. Leiden 1999.

Lane, Edward William. 1860. An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians.5th ed. London. [Rpt. with an introduction by Jason Thompson, Cairo and New York,2003.]

Lawrence, Thomas Edward. 1927. Revolt in the Desert. London: Jonathan Cape.Leder, Stefan. 2005. ‘Al-Wāk. idī, Muh. ammad b. ‘Umar b.Wāk. idī.’ Encyclopaedia of Islam, XI, 101.Lecomte, G. 1993. ‘Mu‘allak. āt.’ Encyclopaedia of Islam, VII, 254.Littmann, Enno. 1960. ‘Alf Layla wa-Layla.’ Encyclopaedia of Islam, I, 358.Lord, Albert Bates. 1960. The Singer of Tales. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. [Re-edition with a

CD and a new introduction by Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy, 2000.]Lyons, M. C. 1995.The Arabian Epic: Heroic and Oral Story-Telling. 3 vols. Cambridge: CUP.

24 Orality and the Tradition of Arabic Epic Storytelling 647

Madeyska, Danuta. 1993. Poetyka Siratu. Studium o arabskim romansie rycerskim. Warsaw: Wydaw-nictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Mahdī, Muh. sin, ed. 1984–94.The Thousand and One Nights (Alf Layla wa-Layla). 3 vols. Leiden:Brill.

Mahdī, Muh. sin. 1995.TheThousand and One Nights. Leiden: Brill.Maqrīzī, Taqī ad-Dīn: Taqī ad-Dīn Ah.mad. 1270/1853–54. al-Mawā‘iz. wa-l-i‘tibār fī dhkr al-khit.

at. wa-l-āthār. II. Boulaq.Margoliouth, D. S. 1925. ‘The Origins of Arabic Poetry.’ JRAS 3:417–49.Meredith-Owens, G. M. 1986. ‘Hamza b. ‘Abd al-Mut. t. alib.’ Encyclopaedia of Islam, III, 152.Miquel, André, trans. 1977.Un conte des ‘Mille et Une Nuits’, ‘Ajîb et Gharîb’. Paris: Flammarion.–. 1981. Sept contes des ‘Mille et Une Nuits’ ou il n’y a pas de contes innocents. Paris: Sindbad.Monroe, James T. 1972. ‘Oral Composition in Pre-Islamic Poetry.’ Journal of Arabic Literature

3:1–53.Myhrman, David W., ed. and trans. 1908. Tāj ad-Dīn as-Subkī. Kitāb mu‘īd an-ni‘am wa-mubīd

an-niqam. Luzac’s Semitic Text and Translation Series 18. Leiden: Brill; London: Luzac.Nacib, Youssef. 1994. Une geste en fragments. Contribution à l’étude de la légende hilalienne des

Hauts-Plateaux algériens. Paris: Publisud.Nagel, Tilman. 1967. Die Qis.as. al-anbiyāʾ. Ein Beitrag zur arabischen Literaturgeschichte. Ph. D.