Nakao, Shuichiro "A "creole" music in Juba Arabic: Direr dance in Juba, South Sudan," Arabic in...

Transcript of Nakao, Shuichiro "A "creole" music in Juba Arabic: Direr dance in Juba, South Sudan," Arabic in...

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

1

A “creole” music in Juba Arabic: Direr dance in Juba, South Sudan

Shuichiro Nakao

Kyoto University, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Introduction

Juba Arabic (henceforth abbreviated as: JA) has been known basically as a lingua franca of South

Sudan with a few younger native speakers in towns, in contrast to the sister-language Kinubi, the

Arabic-based creole, basically spoken as the mother-tongue of Nubi people scattering in East Africa

(concentrating in Kibera of Nairobi, Kenya, and Bombo and Kampala in Uganda). However, a few

studies have mentioned a “detribalized” South Sudanese population in an urban space (former

colonial forts and headquarters) called Malakia (JA. melekíya, Sudanese Arabic malakīya) who have

maintained a set of cultural and linguistic kinship to Nubi (e.g. Kaye 1991).

This study introduces dirêr [di˩reˑr˥˩], a traditional dance

practiced by Malakians in Juba (the capital of South Sudan)

and a similar dance called dolúka [do˩lu˥ka˩] by Nubi in East

Africa, to argue their synchronic and diachronic relationship,

as a finding of the presenter’s fieldwork in the areas (Map 1).

In conclusion, this study suggests that the historical linguistic

development and divergence of Kinubi and Juba Arabic can

be more empirically explained by the aids of the history of

their speech communities and such cultural legacies together

with which these languages developed.

1. Nubi in East Africa and dolúka1

1.1. The history and definition of Nubi

Nubi is known as a representative of “new” ethnicities in Africa which emerged as a result of

creolization in the course of colonization. They have been identified as muslims by religion, Kinubi

speakers by the native language, and by historical background, descendants of “Sudanese soldiers”

or jihādīya (and their followers, namely wives, children, and slaves) who entered East Africa by the

end of the 19th century after serving in the Ottoman-Egyptian Equatoria Province during the second

half of the century.

1 This part is based on the presenter’s fieldwork funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number 26.2651 in

Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Nairobi (Kenya), and Bombo (Uganda), during August–September 2014.

Map 1. Study areas (East Africa)

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

2

The first jihādīya army were established by Mehmet Ali of Egypt, conscripting Sudanese slaves

after his first expeditions to Sudan in 1820. They became famous for fighting in French intervention

war in Mexico on Napolen III’s side during 1863–7 (Hill & Hogg 1995). A part of these soldiers who

fought in Mexico was allotted to the first governor of Equatoria Province, Samuel Baker, and

succeedingly Charles Gordon and Emin Pasha. Their migration into East Africa began with the

Mahdist Revolt in Sudan (1881–1899), whereby Emin Pasha and a part of his jihādīya were caused

to retreat from the current South Sudanese region to Uganda-Congo border areas. By then, the great

part of his jihādīya had been newly recruited in Equatoria Province (Emin 1888: 497), and not

necessarily related to ex-slaves2. While a few of these soldiers followed the Emin Pasha Relief

Expedition (1886–9) led by H. M. Stanley to the East African coast (now Tanzania), many of them

were left behind in Kavalli (now D. R. Congo), amalgamating northwestern Ugandan and

northeastern Congolese populations by intermarriages (Meldon 1908). This group at Kavalli, was

met by Frederick Lugard and persuaded to serve in then British East African sphere (now Uganda,

Kenya, and Jubaland) as the Uganda Rifles, and later the King’s African Rifles. After retirement,

these soldiers were settled in the suburbs or outskirts of urban spaces, represented by Kibera in

Kenya and Bombo in Uganda3. In short, this group is identified as the ancestors of current Nubi

(proper), although there were more intricate mobilization of jihādīya soldiers in these regions4.

Returning to the topic, however, the “Nubi” identity has not been stable. The well known example

is the “Nubianization” (Hansen 1991, amalgamation to Nubi) of northwestern Ugandan population

that took place during Idi Amin’s regime. Thereby, Islam spread among northwestern Uganda, with

some Nubi cultures and Kinubi as a lingua franca for muslims. In addition to this case, the jihādīya

members who reached Tanzania with Emin Pasha were succeedingly recruited to the German

colonial army (Schutztruppe)5, and after retirement, they were settled in urban spaces in Tanzania,

e.g., in a quarter called Unubini (‘Nubi-land’ in Swahili)6 in Dar es Salaam. They now only speak

Swahili7, but share some cultural practices with Ugandan/Kenyan Nubi communities.

2 For example, see “Bukhita Lado’s Experience,” Bombo Advertizer, Midsummer 1913.

3 Other Nubi settlements are found in many of Ugandan towns (e.g. Kitubulu in Entebbe, Kibuli and

Naguru in Kampala), and in Kenyan towns along the Uganda Railways. There were also Nubi settlements

in Jubaland before its cession to Italian Somaliland, namely in Gobwen, Yonte, and Kismayu, but they

were resettled in Mazeras, near Mombasa in (Kenya National Archive, PC/Coast/1/17/28). 4 For example Luffin (2006) argues their presence in Congo. Kabarega (the king of Bunyoro)’s “new

army” called baruusuura is also known to have contained ex-jihādīya Sudanese. Herman von Wissman of

German East Africa Company and F. Lugard (Meldon 1908) recruited retired “Sudanese” ex-soldiers also

from Cairo. Moreover, there were “Sudanese” recruits from Eritrea in the Schutztruppe (Moyd 2010). 5 Interview with Tanzanian Nubis, S.K. in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), August 13, 2014. Meinhof (1917/8a,

b) recorded “Djabalawi” (Lulubo) and “Kondjara” (Fur) languages by the aid of Schutztruppe soldiers

who had served under Emin Pasha. 6 Leslie (1963: 47) records it as Chang’ombe kwa Wanubi ‘Nubi quarter of Chang’ombe ward.’ During

the presenter’s visit in August 2014, the last Nubi resident there moved off because of urban renewal. 7 It remains unclear if they spoke Kinubi proper. For example, Raddatz (1892) records “Sudan Arabic”

words and phrases, which are in fact almost Egyptian Arabic (not a pidgin), with Turkish military phrases.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

3

1.2. Nubi culture

Besides the linguistic8 and religious ones, symbolic Nubi cultures have been enumerated in many

studies on Nubi, for example, sorts of foods like lúguma, kísra, and gurúsa (sorts of bread, from

Sudanese Arabic lugma, kisra, gurrāsa), handcrafts made of grass like tábaga ‘tray,’ kúta ‘food

cover,’ gúfó ‘basket, hand bag,’ and bíris ‘mat,’ women’s wear like tôb and gurbába and accessories

like kipíni ‘nose pierce,’ suwâr ‘arm ring,’ kisâf ‘nose ring (now rare),’ etc9. Beside material cultures,

Nubi practice a specific physical movement to greet elders (called salâm to úsa ‘face-greeting’); one

takes the elder’s right hand and receives it to touch his/her forehead and chin (Uganda/Kenya) or to

kiss it and touch his/her forehead (Tanzania), like the Turkish salām. Interestingly, such cultural

materials and practices are all necessary for wedding ceremonies and best reserved by women.

On the other hand, many other cultures described in earliest ethnographic accounts are almost lost.

For example, scarification on cheeks which was called ‘one-eleven’ during the Idi Amin’s regime,

spirit (wáragi) distillation, and sorts of witchcraft and spirit possession cult, described as sahara and

sheitan in Meldon (1908). These might be related to similar cults called kujuru, ndawa, goza, gundu,

and tumbura in later accounts (Clark 1972: 69–72, de Smedt 2011: 130, Leslie 1963: 48). These are

practically lost in Uganda and Kenya10

, but at least, túmbura seems to be reserved in Dar es Salaam.

Most songs, necessarily sung for the spirits in such cults were sung in unintelligible ancestral ‘tribal

languages’ (Meldon 1908, Clark 1972: 71).

Among traditional Nubi songs are play-songs of children11

, as given in (1), which is sung in an

unintelligible language (Wani and Tombe could be Bari names), and (2), in Kinubi. Generally

speaking, the melody in Kinubi songs is often, but unnecessarily, influenced by linguistic prosody

(lexical tone and intonation) as in the other tone languages (Schellenberg 2013)12

.

(1) wani, wani tombe, kuru wani tombe

kai kai atin jalaba

mo jalaba mo jalaba jimba [Kibera, A.S.]

8 As for oral linguistic cultural practices, for example, Luffin (2002) describes a language taboo, and

Wellens (2005: xv) mentions a cliché for folktales (íja má jáko, akêr/kúrsana/kúlsana má já lína,

according to the presenter’s fieldwork and analyses). See Hurreiz (1977: 35, 131) for a similar phrase in

Sudanese Arabic. Lethem (1920: 225) and Hillelson (1935: 6) record similar phrases for riddles in

Nigerian or Sudanese Arabic. Nubi riddles are begun with a couple of cliché, kóikói [koi˥koi˥] by the

questioner, and a reply, dia(dia) [dia˩(dia˩)], probably of Lugbara origin. 9 See Clark (1972: 60ff), Minala (2000), de Smedt (2011: 126ff), and the Nubian Cultural Ambassador

contest (in Nairobi, 2013, uploaded on www.youtube.com/channel/UCRh4FDJq6aWdTxlb7LdLZ0Q, last

accessed December 7th, 2014). 10

A candidate introduced túmbura in the Nubian Cultural Ambassador contest. 11

The song (1) is for a sort of marble game, and (2) is for a sort of hand game. 12

The prosodic typological status of Kinubi has been controversial, but the presenter considers that it is

accountable as the tone-sensitive “split-prosodic” system, same as Juba Arabic (Nakao 2013a). Thus, this

study tentatively transcribes Nubi in the Juba Arabic orthography adapted from Nakao (2013a).

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

4

(2) dawíya, dawíya, dawíya Dawiya, Dawiya, Dawiya (personal name)

wedi-ní káki wáyi Give me a khaki

káki fi jwo sondû The khaki is inside a box

sondû m=éndi muftâ The box doesn’t have a key

muftâ fí na sultân The key is with the chief

sultân ázu banâ The chief wants girls

banâ ázu mendîl The girls want handkerchiefs

mendîl fi dukân The handkerchiefs are in the shop

dukân ázu lében The shop wants milk

lében tete bágara The milk is under a cow

bágara áju gési The cow wants grass

gési ázu mátara The grass wants rains

mátara wága, wa-wa-wa! It began raining, wa-wa-wa! [Kibera, Y.H.]

Although it is now practically extinct, there was a dance called kamléle with gallant songs as in (3)

in Bombo, which used to be sung to celebrate a victory, or just to have fun (cf. Minala 2000).

(3) kabaréga kóre mawé Kabarega (King of Bunyoro) cried ‘mommy (in Nyoro)’

katuru-kéri number one Praise to the number one [soldier]

dúrubu dufâ (dúfa) he hit the age-mate [Bombo, M.K.]

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

5

1.3. Wedding and dolúka dance

In addition, probably the most prominent Nubi music is represented in dolúka dance, which is

commonly found in all Ugandan, Kenyan, and Tanzanian13

Nubi communities, and reportedly, even

among the “Nubianized” population in northwestern Uganda (e.g. Lugbara, Kakwa).

As most literatures on Nubi tell, dolúka has been strongly associated with wedding ceremonies,

although apparently there have been many changes (de Smedt 2011: 126–127)14

. For example, an

earlier detailed description on dolúka in Kibera tells that “[t]he music is usually provided by women,

who sit around in a group, beating drums and singing in Kinubi […] and more particularly it is the

special task of the women’s association in Kibera,” and, “in case of big weddings one of the

women’s association are asked to provide the music, whilst at smaller weddings it is the womenfolk

of the married couple who provide the music” (Clark 1972: 66–69), but today, dolúka is usually

provided by specific bands consisting of both male and female members15

. Currently, such dolúka

bands are widely found in every Nubi settlement. For example, Bombo, the largest Nubi settlement

holds several dolúka bands, like older Sports Club (Bombo Sports and Social Club) and Sister Club,

and younger Nukras and Yal Hamam. As well, Kibera also holds its own Sports Club (Kibera Sports

and Social Club), Sister Club, and others like Karuma Across. The most popular name of dolúka

band may be Amani Social Club, which is found at least in Entebbe, Arua, Masindi, etc. in Uganda16

.

Out of weddings, dolúka also takes place on other occasions like get-together parties17

, and the

traditional annual Nubi cultural festival called Chai ‘tea [party]’ in Swahili, during the Easter season

(páska) every year. As Clark (1972) points out, this occasion played a main role in developing the

(international) Nubi voluntary associations, for example, Sudanese Association, which had branches

in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (including Zanzibar) until 1970s. After Idi Amin’s overthrow, Nubi

communities have lost such official international societies, thus Chai festival is playing more

important roles to reinforce the value of Nubi communities who have no home-land.

As a living tradition, dolúka songs continue to be created by the bands, and the lyrics typically

represent celebrations for marriage, gossips among Nubi communities. The language used in dolúka

is basically Kinubi, as next examples show. As a rule, linguistic tone influences the musical melody

as in play songs.

13

According to Tanzanian Nubis (note 5), they mainly play dolúka for wedding, but they sing in Swahili. 14

Oldest references of Nubi attest nothing specifically about dolúka, but many mention Nubi dance

called kungu (Cook 1905, Meldon 1908, 1913). Amery (1905), in reference to which Meldon (1913) was

composed, records dallūka ‘dance’ (which today means ‘clay drum’ in Sudanese Arabic). In

contemporary Nubi, kungú means a ‘song,’ not ‘dance.’ This word may be from Bari dance called kungu

(Seligman 1913). However, note that according to Meldon (1908), kungu was indispensable for wakes,

although today dolúka is tabooed in case of funerals. 15

An interesting linguistic evidence for female dominance in the past is a Nubi word ganáya ‘singer,’

which is now used for both sexes, but apparently from Sudanese Arabic ghannāya ‘female singer.’ 16

Interview with M.K. in Bombo, Uganda, September 9, 2014. 17

de Smedt (2011: 127) notes that dolúka took place almost every Saturday in the past.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

6

(4) iya iya, aiya, ráha Oh, oh, comfort

hanîn taí dé, My sweetheart

jomboí ána (or wé) sélem ne íta My lover (daddy), I greeted you

a ya akwaní I greeted you, oh my brothers

iya iya, aiya, maúa Oh, oh, flowers

na ána akwána taí dôldé To all my brothers

jomboí ána (or wé) sélem no úmon My sweetheart, I greeted them

a ya akwaní Oh my brothers [Bombo, Yal Hamam Group]

The so-considered oldest songs represented in (5)–(7) are sung with cryptic expressions including

loanwords from ancestral ethnic languages like Alur, and they are often unintelligible to the singers

themselves, let alone the normal audiences who usually even do not know the lyrics.

(5) ibe deiya tan-bele Ibn Deiya (personal name), a country far from here (?)

aiya (i)be deiya aiya, Ibn Deiya

ibe deiya weraba Ibn Deiya, weeraba (‘good-bye’ in Ganda)

sála wonusú ána je íja Even if I was told like a folktale/gossip

(wonusú ána ketíri je íja) ([Even if] I was told a lot like a folktale/gossip)

ána miskíni I am poor

má bu=logó hája fogo/min ána Nothing will be taken from me [Kibera, A.S.]

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

7

(6) rannáka mé bi sébu Bed-wetter will not leave [it]

námba rabúru (námbar abúru?) Number 8 (in Alur?)

taâl búlu bára Come pee outside

semeti rujále lébis éma Even if men wear turbans (i.e. phimosis)

dúrubu sôp min wên From where will they be whipped (?) [Kibera, A.S.]

(7) abu jarára nenzilú lel uláya Bottoned one was put down to Europe

lel banâ ta sudân For the girls of Sudan

wúsule/rásulu yôm sába Arrived on the seventh day

mal-rijâl fi midân The men (bridegroom)’s bribe is in the plaza [Kibera, A.S.]

Other new songs continue to be produced by every dolúka band. Such songs often have the

group’s name in the lyrics. For example, the next song mentions Big Six (an old famous dolúka band

flourished in the postwar period) as the composer, with the singer’s band name Yal Hamam as well.

(8) a, bígi wê, a, bígi sikisâ Ah, Big, ah, Big Six (repeated before each stanza)

síta kálasu It’s already 12 o’clock ([saa]-síta)

babá tála=kum bára Father(s), come out!

wédé yáli ta yal-hamámu This is [sic?] the children of Yal Hamam

latá sába kálasu The sun has risen

ya akwanâ tála=kum bára Oh brothers,

wédé lungára ta hamámu This is the drum of Yal Hamam

galí mayâi fi sósi Said that eggs are on a pan

babá, ána áju wedí ne íta Darling (babá ‘father’), I want to give you

wédé dáwa ta áju (or mahába) This is the medicine for the affection

galí tangawúzi fi châi Said that ginger is in tea

babá ána áju ájig íta Darling, I want to feed you, say aah

kedé ámula morú na ána Please, oh please do me a favor [Bombo, Yal Hamam]

Basically, dolúka is played throughout the night, thus it begins around sunset. After heating the

drum heads (to tighten them), a performance is mistily begun with a small drum kóŋkóŋ [koŋ˥koŋ˥]

which is beaten with a stick and provides regular ticks, followed by two (or three) middle-sized

drums fádulu kénya ‘remain in Kenya’ beaten with hands, two middle-sized drums kálif ‘roll’ beaten

with hands and sticks, the largest drum uma-lungára ‘mother of drums’, and koyo [ko˩jo˩] (from

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

8

Lugbara) rattles made of cans and sand18

. Nowadays dolúka singers use audio equipment, and

dolúka songs recorded and edited in studios are played when the band is tired of performance. While

the dolúka band is providing the music, the audiences make lines according to his/her sex group, and

begin to dance (mostly just simply stepping, or “rubbing feet (ádaku kurâ)”)19

.

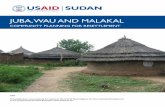

Picture 1. A dolúka music performance at a wedding (Bombo)

Picture 2. A line of dolúka dance (Bombo)

18

Seemingly, the instruments have also undergone some changes. Earlier accounts mention men’s

accompaniment by horn/trumpet (Meldon 1908, Clark 1972), but this tradition seems to be lost today.

Perhaps, it can be attributed to the men’s military band experience (Martin 1991). 19

The word ‘to dance’ differs according to the agent’s sex group (but the usage is not so strict); rógusu

‘to dance (women’s part),’ and tómburu ‘to dance (men’s part).’ The latter may be from Sudanese Arabic

tambar ‘to dance in tumbura (zār)’ (Qāsim 1972: 614, cf. Hillelson 1935: 39–41, 213).

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

9

2. Interlude: Ex-jihādīya descendants in Sudan

Considering their history, it is surprising that Nubi have created such intricate cultural systems, in

parallel with Kinubi, only in a short time. However, it is necessary for studying the origin of Nubi

cultures and language to examine the history and cultural systems of non-Nubi jihādīya descendants

out of East Africa, especially, those who remained in Sudan20

.

Returning to the 19th century Sudan, not all the jihādīya soldiers of Ottoman-Egypt followed

Emin Pasha, but some joined the Mahdists, and the others were defeated and withdrawn to Cairo.

After the occupation of Egypt by the British troops in 1882 after ‘Urābī Revolt, the old jihādīya

soldiers were reorganized as Sudanese battalions of new Egyptian army, who in turn defeated the

Mahdists to establish the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium in the Sudan21

. Among whom was the

father of ‘Alī ‘Abd al-Latīf, whose son founded the White Flag League (1923–1924) to protest

British colonization, manifesting the “Unity of the Nile Valley,” namely the unity with Egypt. This

event led to the evacuation of such Sudanese soldiers by founding new Sudan Defence Force in 1925,

by recruiting local population. Thereby, the retired ex-jihādīya descendants formed colonies in urban

quarters in Sudan called daym, radīf or malakīya ‘civilian’s [square]’22

, and became the core of

civilian urban population of colonial cities (Kenyon 2012, Sikainga 1996).

Remarkably, anthropological and historical studies on northern Sudanese societies have focused

on the jihādīya descendants’ roles of developping modern Sudanese cultures, especially a zār (spirit

possession) variety called tumbura (using a sort of lyre23

), and bridal dances and songs24

by women

(aghānī al-banāt) using goblet drum called dallūka (Kenyon 2012, Makris 2000, Malik 2003,

Sikainga 1996). Comparing these cultures with Nubi equivalents reveals that pre-Nubi jihādīya

cultural systems had already germinated before the migration of Nubi ancestors into East Arica.

This fact is suggestful for historical linguistic study of Kinubi and Juba Arabic, whose divergence

has been assumed to be in a similar period (Owens 1996), but without empirical evidences other than

linguistic similarities. Note well, however, that such cultural systems have been reported only in

northern Sudan, but on the other hand, Juba Arabic is spoken in South Sudan.

20

Other (zār-based) musical practices among ex-jihādīya descendants are found even farther north

beyond Sudan, for example, in Egypt and Montenegro (Nakao 2013b). 21

Lamothe (2011: 102–109) discusses tombura cult and diluka dance of these Sudanese battalions. 22

Similarly, in Uganda, Nubi settlements were called mulki, which is apparently a cognate word. 23

As mentioned in Section 1, Nubi also has played túmbura spirit possession cult using a similar lyre.

Interestingly, the lyre of this type was called (kinanda) kinubi ‘Nubian harp/lyre’ in Swahili. However, it

is unclear if it can be attributed to Nubi. Smidt (1888: 77) reports that it was played by “Nubians” in

Zanzibar, who cannot be the jihādīya of Emin Pasha. The lexime kinubi ‘harp, Nubian’ itself is already

attested as early as Steere (1870). Perhaps, these “Nubians” were to be considered as Sudanese slaves of

Oman, who might have had such tradition (cf. Alpers 1997, at-tanburah (an-nuban) in Oman). 24

Moreover, the Nubi wedding tradition is quite similar to the riverain Sudanese bridal traditions (Al-

Tayib 1991). For example, Sudanese shēla, jirtig, shabbāl, and gata‘ al-rahat ceremonies correspond

Nubi séla, jírtik, sabála, and gata-ráha. Sudanese bridal dance also is reported to include a dance

imitating the movement of birds, which could be similar to Nubi karasa [ka˩ra˩sa˩] dance (Minala 2000).

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

10

3. Malakia in South Sudan and dirêr25

3.1. The history of Malakia in Juba

Actually, the civilians’ square, malakīya is not only found in now Sudan, but also in South Sudan,

but the situations differed because of the Southern Policy. R. C. R. Owen, the governor of newly

established Mongalla Province (during 1908–18) claimed to found an entirely South Sudanese army

instructed in Christianity and English, and disband the old “Arabic”-speaking muslim Sudanese

battalion, which was later incorporated in Sudan Defence Force as Equatoria Corps. However,

despite his intention, almost all newly recruited soldiers settled at Mongalla (north to Juba) became

muslims, speaking a pidgin Arabic (known by various names)26

, due to the intercourse with the old

ex-jihādīya population settled at malakīyas of Mongalla and Rejaf speaking (old) Kinubi27

.

In the late 1920s, the population in the malakīyas of Mongalla and Rejaf were collected as public

workers to build Juba as a new province-cum-district headquarter, and a new residential area was

allotted to them. This area became the Malakia quarter of Juba today, now located in Kator payam28

.

Map 2. Location and structure of Malakia in Juba (adapted from Nakao 2013b)

Throughout the colonial period, the increase of urban population was limited by the British

colonial policy, and the Malakian community remained cut off from rural population and kept old

traditions. The population increase of Juba followed the outbreak of the First Sudanese Civil War in

1955, one year before the independence of Sudan. The term “Juba Arabic” first appeared during this

period, and seemingly, at the same time its speech community expanded drastically so that it fully

became a lingua franca (Nakao 2013c, cf. Nhial 1975, Leonardi 2013).

25

This part is based on the presenter’s fieldwork funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number 23.6924 in

Juba (South Sudan), during September 2012 and September–October 2013. 26

Actually, a similar pidgin Arabic was spoken by British soldiers (Nakao 2013d). 27

Nakao (2013b), Leonardi (2013). A. R. Cook, who collected Kinubi vocabularies (Cook 1905) around

Mongalla notes that it was “spoken and understood over a very large area, from Fajao [in Uganda] on the

Nile, through the Madi and Bari countries to about twenty miles north of Mongalla” (Cook 1945: 222). 28

A payam means an administrative district. Juba consists of Juba Town, Kator, and Munuki payams.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

11

3.2. Malakian culture, dirêr, and the link to Nubi

As the history of Juba tells, Malakians have been one of the oldest residents in South Sudanese

towns, speaking Juba Arabic as their mother tongue. Interestingly, their Juba Arabic variety is

characterized by Nubi-like lexical features (Nakao 2013b for some lexical items, cf. Kaye 1991).

Besides, they share basic cultural systems with Nubi as enumerated above, except that zār cults are

still practically retained in Juba, due to the connections with northern Sudanese malakīya societies.

Just like dolúka of Nubi, Malakian community in South Sudan practices a similar dance called

dirêr for weddings, get together parties, cultural or national festivals. It is performed by expert bands,

using similar drums (kóŋkóŋ, seven care, kelîf, uma-nugára) and rattles (koskôs). Malakia in Juba

has Al-Aman Social Club as their representative band, which was renamed from Manwar (manwâr

[man˩waˑr˥˩] or mánwar [man˥war˩], from British ship “Man-of-War”) in the colonial period.

Picture 3. A dirêr performance at a wedding (Juba)

The songs sung in the dance are also almost identical or related to Nubi dolúka songs. For

example, the most famous song in Malakia is the one shown in (9), which is identical to dolúka song

(7), sung in both Kenya and Uganda. As the dirêr singers and other Malakian elders tell, this song is

at least as old as Juba, namely the migration of Malakia population from Mongalla and Rejaf.

(9) abu jarára jarára le wiláya The buttoned one, buttoned up to the Province [HQ?]

lel-banât ta sudân Young girls of Sudan

nenzilí yôm sába Got down on the seventh day

ma rijâl fi midân With men in the plaza [Juba, Al-Aman]29

29

The presenter has recorded another version in Nakao (2013b), which seems older.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

12

Also, the next examples (10)–(14) can be found relevant to Nubi from the lyrics. The song (10)

appears to be related to the colonial mobilization of Nubi with whom Bangladeshi troops served in

the war. However, as the rest of the lyrics shows, it is sung in a wedding, and the Bangladeshi-Nubi

comradeship can be interpreted here as a metaphor to encourage the new relation by marriage.

(10) aju-bádu kuwési It is good to love each other

kelí nína límu bádu Let us get together

Bangaladési gí rúwa Bangladeshi [troop] is leaving

kelí nína rúsu móyo Let us sprinkle water on them [for celebration]

(kelí nína ómba duwâ) (Let us make a du‘ā’ [from Swahili omba dua])

nas-arúsa fí wéni The bride and her family, where are they?

kedé úmon tála bára Let them come out

Bangaladési gí rúwa Bangladeshi [troop] is leaving

kelí nína límu bádu Let us get together

The next examples represent gossips, seemingly from a Nubi community, as explicitly mentioned

in (12). In the texts, Nubi forms (e.g. na ‘DATIVE,’ rági ‘man, husband’) and Juba Arabic forms (e.g.

le ‘dative,’ rágil ‘man, husband’) are freely mixed30

.

(11) Halíma wé, kélim le Dafálla Halīma, o, tell Daf‘allāh

kedé úwo jíbu sáa haráka To bring a watch at once

dúsuman ganá, kélim na akwána Singers fought, tell brothers

akilí rági ma dáwa A man was poisoned

shulu-rágil ta mára, ána áju má Taking another person’s husband, I don’t want it

kúlu wâi ma tô Every one [should be] his/her own

30

Besides, (11) shows Swahili loanword haráka ‘at once’ and Nubi negative construction áju mâ (gloss:

want NEGATIVE). (12) shows explicitly Nubi word nâ ‘there,’ cf. Juba Arabic inâk ‘there.’

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

13

(12) Nyagwá, Nyagwá kátulu jéna Nyagwa, Nyagwa killed a child

Nyagwá, Nyagwá wé Nyagwa, Nyagwa, oh

Kukú, Kukú kasúra Kuku, Kuku is a witch

Kukú, Kukú kátulu Kenyí Kuku, Kuku killed Kenyi

Nyagwá, samadári ta Dóka Nyagwa, Doka’s (bridal) bed

fi Bómbo nâ There at Bombo

íta gí síbu le munú For whom do you leave it?

Despite that Malakia population, unlike Nubi communities in Uganda and Kenya, do not speak

Swahili or Ganda languages, such languages appear in the lyrics. For example, (13) shows Swahili

expression hodi ‘excuse me (entering the house)’ and karibu ‘welcome,’ and (14) is sung entirely in

Ganda (perhaps newly learned from Nubi dolúka bands).

(13) kóŋ-kóŋ, hódi, karíbu Knock-knock, excuse me, yes please

munú dúgu bâb dé Who’s knocking the door?

dé ána halû It’s me, hello

dé ána ásuma góho I heard a cough

galí gidída taláta, mamá Said that three hens

áse dé ána dába le halû I killed them for Mr. Hello

(14) bas ajudde, bas ajudde The bus is full, the bus is full

kabula-naka Kabula Naka (place name in Uganda)

As a new development of Al-Aman Social Club’s activities, they have begun to participate in Chai

festivals in Uganda in recent years. According to the members, their performance in the competition

won the first prize, and their singings were recorded in Uganda for the first time31

. Herewith, their

history and identity, as descendants of jihādīya soldiers, are thus reconfirmed on a physical reality,

both by Malakians and Nubi32

.

3.3. Malakia and South Sudanese nationalism

Besides, we cannot underestimate the impact of dirêr just as a tradition to Malakians as relatives of

Nubi, when we consider the emergence of South Sudanese popular arts in Juba Arabic.

31

Interview with members of Al-Aman by the presenter, October 2013. 32

However, the intercommunication between Malakians and Nubi has not been completely cut off. There

were ex-King’s African Rifles soldiers who settled in Malakia after their retirement to “come back home”

(Nakao 2013b). Otherwise, Nubi people came and went between Uganda and South Sudan since their

main occupation was traders (Nhial 1975). Also, after the overthrow of Idi Amin, many Nubi took refuge

to South Sudan, and resided near Malakia.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

14

Lorins (2007: 181) mentions a lecture by a founder of Kwoto, a South Sudan-based theater

company famous for using Juba Arabic in Khartoum as a symbol of South Sudanese identity (Miller

2000), wherein he suggests that their activities have Malakians as their precursors, among whom late

Yusuf Fataki, a famous South Sudanese singer who sang in Juba Arabic33

. Yusuf Fataki, born in

Malakia of Yei (a town now in Central Equatoria Province, South Sudan), began his singing career

as a dirêr player. He is best known for a “patriotic” song, Yei Beledina ‘Yei, our country.’

Such patriotic songs are, actually, often sung in dolúka, as represented by the next two songs.

Before the independence of South Sudan in 2011, the phrase junûb wáhid dé ‘one South’ in (15) was

sung as sudân wáhid dé ‘one Sudan,’ and Sudanese president ‘Umar al-Bashīr was also appreciated

(with then vice-president John Garang) in the song (16). Interestingly, in such songs, the Juba Arabic

lyrics show more mesolectal features (influenced by “properer” Arabic), e.g., yóm-na ‘our day’ in

(15), instead of basilectal yôm tanína, etc.

(15) hilâl wáhid dé, ya yúma One crescent moon, mom

hilâl wáhid dé One crescent moon

junûb wáhid dé sáwa One South [Sudan], together

junûb wáhid dé One South [Sudan]

nas Dínka wa Bari Dinka and Bari people

úmon yal-gebíla wáhid sáwa They are same children of one tribe

(16) yóm-na, yóm-na, junubîn lé-na Our day, our day, Southerners for us

aléla yóm-na Today is our day

Baba Sálva rúwa fi Nevásha Father Salva [Kiir] went to Naivasha

rúwa jíbu salâm lé-na And brought us peace

Mama Rebéka rúwa fi Entébe Mother Rebecca [Nyandeng] went to Entebbe

rúwa jíbu salâm lé-na And brought us peace

wíhida wataníya, wíhida National unity, unity

4. Conclusion

So far, we have compared the two musical practices of Nubi and Malakian communities, and argued

that these traditions can be considered as an inheritance from old jihādīya community (of Equatoria

Province) dating back to the late 19th century at latest (As mentioned in Section 2, similar cultural

systems are even seen in ex-jihādīya communities in northern Sudan). At the same time, Malakian

dirêr well exemplifies the social changes in South Sudan during the colonial and postcolonial period,

wherein the disbanded ex-jihādīya community have amalgamated local populations.

33

Miller (2010) mentions that another Kwoto founder agreed with this discourse.

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

15

This summary above can be interpreted for linguistically-oriented interests as follows: First, the

history of Nubi and Malakian cultural systems, represented here by dolúka and dirêr, showing

“homologies between linguistic and cultural creolization” as have been argued for European-based

creoles (Chaudenson 2001: 194), fully supports Owens (1996)’s assumption that proto-creole of the

two languages had stabilized before the departure of Nubi ancestors from South Sudan to East Africa.

Second, however, the other side of the same coin shows that the sociolinguistic status of Juba Arabic

as a lingua franca developed side by side with the urbanization. Thus, the idea implied in preceding

studies that Juba Arabic is has been going through “gradual creolization” is discarded.

References

Al-Tayib, A. 1991. The Changing Customs of Riverain Sudan: IV Marriage. In Sudan: Environment

and People, Second International Sudan Studies Conference Papers, Vol. 3. Durham:

University of Durham. 235–259.

Alpers, E. A. 1997. The African Diaspora in the Northwestern Indian Ocean: Reconsideration of an

Old Problem, New Directions for Research. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 17 (2): 62–81.

Amery, H. F. S. 1905. English-Arabic Vocabulary for the Use of Officials in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Cairo: al-Mokattam Printing Office.

Chaudenson, R. 2001. Creolization of Language and Culture. London: Routledge.

Clark, D. 1972. Kibera: Social Dynamics of a Low Income Neighbourhood in Nairobi. MA thesis,

Makerere University.

Cook, A. R. 1905. Dinka and Nubi Vocabularies. Makerere University, AR/MAK/97/7.

———. 1945. Uganda Memories (1897–1940). Kampala: The Uganda Society.

de Smedt, J. 2011. The Nubis of Kibera: A Social History of the Nubians and Kibera Slums. Ph.D.

thesis, University of Leiden.

Emin Pasha. 1888. Emin Pasha in Central Africa: Being a Collection of His Letters and Journals

(translated by R. W. Felkin). London: George Philip & Son.

Hansen, H. B. 1991. Pre-Colonial Immigrants and Colonial Servants: The Nubians in Uganda

Revisited. African Affairs 90: 559–580.

Hill, R. & P. Hogg. 1995. A Black Corps d’Élite: An Egyptian Sudanese Conscript Battalion with the French Army in Mexico, 1863–1867, and its Survivors in Subsequent African History. East

Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Hillelson, S. 1935. Sudan Arabic Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hurreiz, S. H. 1977. Ja’aliyyin Folktales. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kaye, A. S. 1991. Peripheral Arabic Dialectology and Arabic Pidgins and Creoles. Language of the World 2: 4–16.

Kenyon, S. M. 2012. Spirits and Slaves in Central Sudan: The Red Wind of Sennar. New York:

Palgrave MacMillan.

Lamothe, R. M. 2011. Slaves of Fortune: Sudanese Soldiers & the River War 1896–1898. Suffolk:

James Currey.

Leonardi, C. 2013. South Sudanese Arabic and the Negotiation of the Local State, c. 1849–2011.

Journal of African History 54 (3): 351–371.

Leslie, J. A. K. 1963. A Survey of Dar es Salaam. London: Oxford University Press.

Lethem, G. J. 1920. Colloquial Arabic: Shuwa Dialect of Bornu, Nigeria and of the Region of Lake

Chad. London: Crown Agents for the Colonies.

Lorins, R. M. 2007. Inheritance: Kinship and Performance of Sudanese Identities. Ph.D. thesis, The

University of Texas at Austin.

Luffin, X. 2002. Language Taboos in Kinubi: A Comparison with Sudanese and Swahili Cultures.

Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell’Istituto italiano per l’Africa e

ArCo 2014, Dec. 15-17, Università di Napoli l’Orientale (Minor revisions, Jan. 12, 2015)

16

l’Oriente 57 (3): 356–367.

———. 2006. Les recrues soudanaises de l’État Indépendant du Congo (1892–1894): un épisode

méconnu de l’histoire des Nubi. In L. Denooz & X. Luffin (eds.) Autour de la géographie

orientale... et au delà. Leuven: Peeters. 123–134.

Makris, G. P. 2000. Changing Masters: Spirit Possession and Identity Construction among Slave Descendants and Other Subordinates in the Sudan. Evanston: Northwestern University

Press.

Martin, S. H. 1991. Brass Bands and Beni Phenomenon in Urban East Africa. African Music 7 (1):

72–81.

Meinhof, C. 1917/8a. Djabalawi. Sprachstudien im egyptischen Sudan 8: 63–69.

———. 1917/8b. Kondjara. Sprachstudien im egyptischen Sudan 8: 117–139, 170–195.

Meldon, J. A. 1908. Notes on the Sudanese in Uganda. Journal of the Royal African Society 7: 123–

146.

———. 1913. English and Arabic Dictionary of Words and Phrases Used by the Sudanese in

Uganda. University of London, SOAS, MS.53704. Miller, C. 2000. Juba Arabic as a Way of Expressing a Southern Sudanese Identity in Khartoum. In A.

Youssi (ed.) Aspects of the Dialects of Arabic Today. Rabat: Amapatril. 114–22.

———. 2010. Quelque aspects de la creation artistique et de la littérature sud-soudanaises à Juba et

au sein de la diaspora. Études littéraires africaines 28: 31–44.

Minala, H. M. 2000. Developing Nubian Culture as a Tourist Product: Case Study: Nubians in

Uganda. BA thesis. Makerere University.

Moyd, M. 2010. “All People were Barbarians to the Askari...”: Askari Identity and Honor in the Maji

Maji War, 1905–1907. In J. Giblin & J. Monson (eds.) Maji Maji: Lifting the Fog of War.

Leiden: Brill. 149–179.

Nakao, S. 2013a. The Prosody of Juba Arabic: Split Prosody, Morphophonology and Slang. In M.

Lafkioui (ed.) African Arabic: Approaches to Dialectology. Berlin: de Gruyter. 95–120.

———. 2013b. A History from Below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927–1954. The Journal of

Sophia Asian Studies 31: 139–160. ———. 2013c. Early Steps to Juba Arabic, 1899–1964: Towards a Sociolinguistic History of a

Lingua Franca in Southern Sudan. Paper presented at a seminar, Historical and

Sociological Aspects of Juba Arabic, October 3, Juba.

———. 2013d. Pidgins on the Nile: Tracing Back the History of European Influence on Arabic-

based Pidgins. Paper presented at AIDA10, November 12, Qatar.

Nhial, A. A. J. 1975. Ki-Nubi and Juba Arabic: A Comparative Study. In H. Bell & S. H. Hurreiz

(eds.) Directions in Sudanese Linguistics and Folklore. Khartoum: Khartoum University

Press. 81–93.

Owens, J. 1996. Arabic-based Pidgins and Creoles. In S. G. Thomason (ed.) Contact Languages: A

Wider Perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 125–172.

Qāsim, A. S. 1972. Qāmūs al-lahjah al-‘arabīyah fī al-sūdān. Cairo: al-Maktab al-misrī al-hadīth.

Raddatz, H. 1892. Die Suahili-Sprache, enthaltend Grammatik, Gespräche, Dialekte aus dem Innern

und Wörterverzeichnisse, mit einem Anhange: Sudan-Arabisch, und einer Einführung in die Bantusprachen. Leipzig: Koch’s Verlag.

Malik, S. I. 2003. Exploring Aghani al-Banat: A Postcolonial Ethnographic Approach to Sudanese

Women’s Songs, Culture, and Performance. Ph.D. thesis, Ohio University.

Schellenberg, M. H. 2013. The Realization of Tone in Singing in Cantonese and Mandarin. Ph.D.

thesis, the University of British Columbia.

Seligman, C. G. 1913. The Southern Sudan. In W. Hutchinson (ed.) Customs of the World Vol. 2.

London: Hutchinson. 708–736.

Sikainga, A. A. 1996. Slaves into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Smidt, K. W. 1888. Sansibar: Ein Ostafrikanisches Culturbild. Leipzig: F. A. Brodhaus.

Steere, E. 1870. A Handbook of the Swahili Language, as Spoken at Zanzibar. London: Bell &

Daldy.

Wellens, I. 2005. The Nubi Language of Uganda: An Arabic Creole in Uganda. Leiden: Brill.