Mysterious Caves of Maresha

Transcript of Mysterious Caves of Maresha

30 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

It Is commonplace In archaeology: an excavatIon provIdes us with more questions than answers. That is certainly true at Maresha.

The site is mentioned several times in the Bible, the first time in Joshua, in connection with the division following the Israelite entry into the land. To Judah was assigned Maresha, a town “with its vil-lages” (Joshua 15:44). However, the earliest remains recovered at the site (known at the beginning of the 20th century by its Arabic name, Tel Sandahanna) date to the eighth century B.C.E. While it is

Ian Stern

31B i B l i c a l a r c h a e o l o g y r e v i e w

theoretically possible that earlier remains may be discovered in the future, it is more probable that the text of Joshua was written at a later date when Maresha had already been established.

Occupation at the site was confined to the mounded tell during the Biblical period. It was a village of a mere 6 acres. In the Hellenistic period (third–second centuries B.C.E.) Maresha expanded to a lower city that surrounded the tell, enlarging the town to 80 acres, a more than 13-fold increase!

Ga

ro

Na

lb

aN

dia

N

32 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

The most amazing aspect of the site is that in the Hellenistic perioda series of extraordinary underground cave com-plexes was created—or rather quarried—under the buildings of Maresha. So far, more than 170 of these underground cave complexes have been iden-tified that include thousands of caves.

Of course it is the geology of Maresha that makes this possible. But the phenomenon seems not to have occurred elsewhere—at least not on this scale.

Maresha is located 24 miles southwest of Jeru-salem and 18 miles east of the Mediterranean coast, in the area known as the Shephelah, between the central mountain range and the coastal plain. This area of Judah is the low hill country.

Geologically, Maresha is unusual. It lies on a layer of hard limestone over softer chalky material. The hard limestone cover prevents the relatively softer, compact and homogenous chalky material from eroding.

The process for creating the cave complexes was rather simple. The limestone crust is up to about 10 feet thick. The ancient stonemasons would first create an opening in this hard upper crust, either as a shaft or as steps. Once they had penetrated into the chalky material, it was possible to hew out large underground chambers that were relatively

stable.When the underground rooms were larger than

6 feet wide, the ceilings were strengthened by quarrying them as vaulted arches or by creating (unexcavated) pillars as supports.

The idea for these underground cave complexes no doubt originated when the city expanded from the small 6-acre village to the 80-acre lower city in the Hellenistic period (although at least one of the rooms of one cave, SC 75, was created already in Iron Age II). The new lower city was thought-fully laid out in insulae, what we would call city blocks. The houses and shops of each insula were separated by streets and narrow alleys.

The building materials for the structures on the surface were rectangular blocks of chalk quarried from beneath the buildings. The subterranean cave complexes were thus an integral part of the build-ings and streets on the surface.

Each complex contains several clusters of caves. The entrances into these systems are via openings or quarried staircases through the floors of the dwellings, their courtyards or in openings between

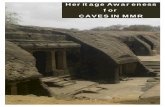

PREVIOUS PAGES: ANCIENT UNDERWORLD. Beneath Hel-lenistic Maresha are thousands of manmade caves hewn from the soft chalk that underlies the hard limestone bedrock of the Judean foothills. The caves were quarried into spacious underground complexes, some supported by vaulted ceilings and massive unexcavated pillars (pic-tured here), that accommodated the everyday building, industrial and even ritual needs of a thriving, multi-ethnic community dominated by the Idumeans, the descendants of the Biblical Edomites, but including Judeans and oth-ers as well.

*See Boaz Zissu, “This Place Is for the Birds,” bar, May/June 2009.

Ga

ro

Na

lBa

Nd

IaN

R u n n i n g H e a d e R

33 B i B l i c a l a r c h a e o l o g y r e v i e w

buildings.To build and maintain the structures that were

above the surface required a continuous supply of stone blocks from the soft chalky layer beneath. These blocks above the surface would have to be replaced due to wear and tear, and this would in turn require further quarrying beneath the surface.

The cave complexes are little short of architec-tural marvels, consisting of room after room. I have already mentioned the vaults and pillars. Another feature: Some of the staircases have beautifully carved banisters, reflecting the high-quality stan-dards of the local population.

The cave complexes had a variety of functions. Aside from their use as a major source of building material for the city, many caves also had an indus-trial function. The olive oil industry was an impor-tant industrial enterprise at Maresha and was often conducted in these underground complexes. To date, 27 olive press factories have been discovered.

Areas of the cave complexes were also used as columbaria for raising doves.* So far, we have found 85 columbaria. Doves were used both as sac-rificial animals and for food. Their droppings were

used as fertilizer. Niches for the doves are gener-ally found in the upper portion of the cave walls, which prevented predators from having easy access to the nests.

Many of the cave complexes were plastered. These were most likely used as water cisterns for the collection and storage of rain water. In many of these systems, the drainage channels to them are obvious. Some of them have banisters leading down the stairs to the cistern. Rope marks at the top of the staircases often locate where vessels were low-ered to collect the water.

We have also found a number of baths—for

RENEWABLE RESOURCE. By the third century B.C.E., Maresha extended well beyond the small, 6-acre mound of the Iron Age town referenced in the Book of Joshua (15:44) to include an expansive, 80-acre lower city that surrounded the existing mound. The new city was orga-nized into regular city blocks, or insulae, separated by narrow streets and alleys built with rectangular blocks of chalk quarried from the caves beneath. As buildings fell into disrepair, the chalk excavated from the ever-expand-ing cave complexes supplied a ready source of fresh building material.

34 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

bathing but possibly also for ritual immersion, similar to later Jewish mikva’ot. Some of them are small rooms that appear to be designed so that an individual can sit inside them, with water chan-nels leading into them. Two baths, discovered on the tell and in my opinion misidentified by earlier excavators, contain staircases leading down to what appear to be areas for immersion.

Some of the cave complexes contain troughs,

suggesting that these areas were used as stables for animals. The height of the troughs indicates that the animals were probably donkeys. U-shaped handles carved into the walls were used to tether the animals in these areas.

The discovery of many loom weights in the cave fill reveals a domestic textile industry. True, these loom weights could have originated in the dwell-ings above the surface and been discarded into the underground areas at a later date. The presence of industrial-size vats quarried into subterranean

COTTAGE INDUSTRIES. Maresha’s inhabitants used the expansive cave complexes below the city for a variety of industrial functions. Among the complexes, for example, are 85 columbaria for raising doves (above), each carved with hundreds of small niches where the sacrificial birds were kept and their droppings gathered for fertilizer. Other caves feature round crushing basins (left) used to grind olives into a mushy pulp that could then be pressed in other installations to produce olive oil. Archaeologists have also identified loom weights in almost every sub-terranean complex, suggesting Maresha had a large but primarily domestic textile industry. Some of the caves also contained carved basins used for dyeing that were perhaps connected to textile production.

Ze

v r

ad

ov

aN

/ww

w.B

IBle

laN

dP

IcT

ur

eS

.co

M

Ze

v r

ad

ov

aN

/ww

w.B

IBle

laN

dP

IcT

ur

eS

.co

M

35 B i B l i c a l a r c h a e o l o g y r e v i e w

walls, however, probably for dyeing, suggests that at least part of the textile operation took place under-ground.

Much of the subterranean area was no doubt used also for storage. The storage niches and silo-shaped rooms are evidence of this.

One of the great mysteries of these caves involves the condition in which we found them. Almost all of the thousands of subterranean rooms were filled with tons of debris that appear to have been dumped into them from the dwellings above. This debris almost reaches the ceilings, even in rooms that had no direct access to the surface. In some of these underground rooms we removed more than 30 feet of fill before reaching the bedrock floor. The material excavated contained unstratified debris, including pottery sherds as well as thousands of whole vessels, coins, jewelry, Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew ostraca (inscriptions on broken pieces of pottery), animal bones, amphora stamps, figurines as well as building stones from the dwellings above. Why the inhabitants would bother to go to such an effort to fill up all of these caves remains a mystery.

But this lack of stratigraphy turned out to have an important advantage. It means that there is no reason to excavate this fill material stratigraphi-cally; there were no occupational layers to sepa-rate and identify. Anyone could excavate this mate-rial. You didn’t have to know anything about how archaeologists carefully excavate stratum by stra-tum, layer by layer.

This provided the opportunity for the Dig-for-a-Day program of the Archaeological Seminars Institute to use Maresha as its key site. These caves could be excavated by people with no train-ing who wanted to experience archaeology for a day—or less. This program allows untrained people, often families of all ages, to excavate unstratified fill guided by professionals.* More than one mil-lion people over the past 27 years have enjoyed the thrill and excitement of participating in an archaeo-logical excavation through this program. And the fees from the program have underwritten the entire excavation, including the processing of all the finds.

During the Hellenistic period, Maresha was eth-nically mixed, not surprising given the city’s history. In the eighth century B.C.E. it was a Judahite vil-lage. After the Babylonian conquest of Judah in the sixth century B.C.E., Judah was severely weakened, and it appears there was an incursion of Edomites from the south into this area, to such an extent that they became the dominant ethnos in Maresha. The

region then became known as Idumea—Greek for Edom. Later in the sixth century the Babylonians were defeated and replaced by the Persians, only to be themselves conquered by Alexander the Great in the mid-fourth century B.C.E. This conquest intro-duced Greek culture to Maresha. After Alexander’s death in 323 B.C.E., his empire was divided princi-pally between two of his warring generals, Ptolemy and Seleucus. The Ptolemies dominated Egypt and the Seleucids dominated Syria. Palestine was a war ground between them. When the Ptolemies domi-nated the area in the third century B.C.E., Maresha

INTO THE DEPTHS. Many of Maresha’s caves were plas-tered and functioned as massive underground cisterns that collected water from drainage channels running from the surface. The cisterns were often so deep that wind-ing staircases with banisters were needed to reach the bottom, while rope marks worn into the rock show that vessels could also be lowered to gather water.

*See Suzanne F. Singer, “The dig-for-a-day experience,” bar, May/June 2010; and dorothy d. resig, “volunteers Find Missing Pieces to looted Inscriptions,” bar, May/June 2010.

rIc

ha

rd

No

wIT

Z

36 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

became the central city of the region.1 As such, it was the seat of various government offices until the Seleucids defeated the Ptolemies at the battle of Paneas in 198 B.C.E., at which point the city came under Seleucid control.

The Seleucids used Maresha as a base to launch attacks on Judea, and therefore it became subject to retaliation from the Maccabees (1 Maccabees 5:66; 2 Maccabees 12:35).

This history is reflected in the Maresha tombs.* The burial grounds outside the city contain mostly early-third to second-century B.C.E. tombs, reflect-ing a syncretism of the styles of the ruling Ptol-emies, with Phoenician influence. Many of them contain inscriptions reflecting the various ethnic groups that resided in the city. These inscriptions, together with the numerous other epigraphic remains, give us a picture of a multi-ethnic society.

Of the approximately 1,300 names from pub-lished ostraca, 30 percent are Nabatean or Arab, 24 percent are Idumean, 28 percent are West Semitic,

9 percent are Judahite (or Judean), 5 percent are Phoenician and the remaining 4 percent are a mix-ture of smaller groups.2

It is especially interesting to look at the intergen-erational names in the tombs. There is an almost complete integration of ethnicities starting in the late Persian period and continuing through the Hellenistic period. The intermixture of the tombs of different ethnicities probably reflects the situ-ation in the city. Everyone seems to have gotten along together.

Among the more puzzling finds from the exca-vation are 17 phalli made of chalk, all of which are

NO STRATIGRAPHY, NO PROBLEM. For reasons that archaeologists still can’t explain, Maresha’s caves were found filled to the brim with earth, stone and debris tossed down from the houses and streets above. With-out any complex stratigraphy to record, the excavation of the cave complexes is handled primarily by volunteers in the Dig-for-a-Day program of the Archaeological Semi-nars Institute in Israel. With professional instruction and supervision, volunteers of all ages are able to spend a few hours unearthing the caves’ many treasures, includ-ing pottery, jewelry, bones, figurines and even inscribed ostraca, all detailing the everyday lives of Maresha’s inhabitants.

UNDER THE INFLUENCE. This beautifully restored tomb located just outside Maresha reflects the Hellenistic styles favored by the city’s inhabitants during the third and second centuries B.C.E., when Alexander the Great’s heirs—the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria—battled each other for control of Palestine. The colorful wall paintings include amphora and columns flanking the gabled entrance to the main chamber (center of photo), as well as a continuous frieze of wild animals, many likely inspired by animals held in the royal zoo in Ptole-maic Alexandria. The tombs also feature inscriptions that reflect the city’s diverse, multi-ethnic makeup.

*See david M. Jacobson, “Marisa Tomb Paintings,” bar, March/april 2004; amos Kloner, “underground Metropolis: The Subterranean world of Maresha,” bar, March/april 1997.

Ga

ro

Na

lBa

Nd

IaN

co

ur

Te

Sy

Ia

N S

Te

rN

/ar

ch

ae

olo

GIc

al

Se

MIN

ar

S I

NS

TIT

uT

e

37 B i B l i c a l a r c h a e o l o g y r e v i e w

circumcised.This brings up another touchy subject. In about

111 B.C.E. the Hasmonean Jewish ruler of Judea, John Hyrcanus I (137–104 B.C.E.), conquered what was then Idumean Maresha. According to the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus, Hyrcanus allowed the surviving Idumeans to remain in Mare-sha if the men agreed to be circumcised and to adopt the “laws of the Jews.” Here are Josephus’s words:

Hyrcanus took also Dora and Marissa [Mare-sha], cities of Idumaea, and subdued all the Idumaeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews [emphasis added]; and they were so desirous

of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to the use of circumci-sion, and the rest of the Jewish ways of living [emphasis added]; at which time therefore this befell them, that they were hereafter no other than Jews.3

While Josephus implies a forced conversion, the Greek historian Strabo (c. 64–24 B.C.E.), who never missed an opportunity to criticize the Hasmo-neans,4 implies a different picture. He is poignantly silent regarding any forced circumcision. He would certainly have mentioned it if it had occurred. But why would Josephus tell of a forced circumcision if it had not occurred? One guess is that Josephus’s source here (as frequently elsewhere) was the his-torian Nicolaus of Damascus, who was zealously anti-Hasmonean.

Although Josephus claims that the Hasmoneans “held” the city,5 the archaeological evidence points to a limited Judean presence at best as seen by the lack of any meaningful Judean remains post-111 B.C.E. Early excavators Frederick Jones Bliss and R.A.S. Macalister discovered 25 Hyrcanus coins in their excavations on the tell,6 statistically marginal at best when seen in the context of the more than 1,300 coins we have discovered so far.

Now back to the phalli. All of them predate the Hasmonean conquest of Maresha.

The depiction of a phallus without a foreskin in the Hellenistic world was considered indecent and was usually an object of ridicule. To conceal their

A MIXED MULTITUDE. Excavation of the caves has revealed hundreds of ostraca inscribed in Aramaic, Greek and Hebrew containing more than 1,300 personal names from Maresha’s diverse community of Idumeans, Judeans, Arabs and Phoenicians. The eight-line Aramaic inscription at right, for example, lists 11 different names that reflect Maresha’s diversity, including the Idumean name Qosnatan (“Qos has given”), the Nabatean Arab name Ab-Awsu (“father of Awsu”) and a possible form of the Hebrew name Shemaryahu (“protection of Yahweh”).

38 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

circumcision, Jews who wanted to live in the world of the Hellenistic gymnasia (where men worked out in the nude) often underwent an operation known as epispasm, a kind of foreskin restoration. The Roman historian Tacitus (56–117 C.E.) viewed circumcision as abominable and summed up its sociological significance: “They [the Jews] adopted circumcision to distinguish themselves from other peoples by this diversity.”7

That the phalli found at Maresha date prior to the Jewish (Hasmonean) conquest of the city is evi-dence of the probability that the Idumeans, along

with many other peoples in the region, already practiced circumcision. Jeremiah 9:24–25 refers to Edomites (ancestors of the Idumeans), Ammonites, Moabites, desert dwellers and Egyptians, in addition to Judahites, who were circumcised. The third-cen-tury B.C.E. Zenon papyri refer to circumcision as a marker that identified runaway slaves from Mare-sha, long before the supposed forced conversion of the Idumeans referred to by Josephus.

In short, the phalli from Maresha are probably not Judean. Josephus’s version of the event needs to be reconsidered. The conversion of the Idu-means may well have been voluntary. The phalli from Maresha indicate that circumcision was practiced here before the Judean conquest of the city. It is quite possible that those Idumeans who remained in Idumea eventually accepted or were understood to have accepted the Judean symbolism of the act. It became part of a broader accultura-tion process with their Judean neighbors.

The Idumeans not only practiced circumcision but they also had ritual purification baths. Amos Kloner, professor emeritus of Bar-Ilan University, who led the Maresha excavations until 1999, has identified approximately 20 small rock-cut cham-bers as ritual purification baths.8 The discovery of such baths at an archaeological site is customar-ily interpreted as something particularly Judean, serving as a kind of ethnic marker. These baths at Maresha, however, predate any archaeological evi-dence of Jewish mikva’ot discovered in Judea.

One of the other mysteries of the site has been the discovery of more than 400 ceramic vessels that were punctured for no apparent reason.9 The default explanation of any puzzling archaeological phenomenon is often “cultic.” I think that is true here. The practice resembles later Jewish Levitical laws of purity. These laws state that if, for example, a person comes in contact with a corpse, that per-son is in a temporary state of impurity (e.g., Leviti-cus 22:4–6). If that person should touch another person or a ceramic vessel, that impurity is passed on. In the case of a ceramic vessel, it can no longer be used and therefore must be broken.

SHARED CULTURE. Josephus records that following Maresha’s conquest by the Hasmonean ruler John Hyr-canus, the Idumeans of Maresha were forced to convert to Judaism and to be circumcised. The discovery of 17 circumcised chalk phalli in the Maresha caves, however, suggests that knives were not the main tool of this con-version. Rather, the phalli, which predate the Hasmonean conquest, indicate the Idumeans already practiced cir-cumcision (as did their Edomite ancestors before them, according to Jeremiah 9:24–25) and therefore may well have converted to Judaism voluntarily, especially consid-ering other cultural commonalities.

CAVE BATHING. Throughout the cave complexes are nearly two dozen rock-cut chambers with small baths that may have been for ritual bathing, similar to Jew-ish mikva’ot in Judea. This example, tucked away at the bottom of a narrow flight of stairs and measuring about 5 feet long and 2.5 feet wide, was a sitting bath in which the bather sat on the bottommost curved step at the very bottom of the photo with their legs and feet extended into the shallow pool. Water would then flow through the channel and opening above (visible at upper left of photo) and wash over the bather. c

ou

rT

eS

y y

eh

oN

ad

av

Me

lTZ

er

ST

er

N/a

rc

ha

eo

loG

Ica

l S

eM

INa

rS

IN

ST

ITu

Te

co

ur

Te

Sy

aS

Sa

F S

Te

rN

/ar

ch

ae

olo

GIc

al

Se

MIN

ar

S I

NS

TIT

uT

e

39 B i B l i c a l a r c h a e o l o g y r e v i e w

But if this rule applied in Idumea, why not just destroy the vessel? Why puncture a hole in it?

One day, while excavating with one of the Dig-for-a-Day volunteers, we discovered one of these punctured vessels. I shared my dilemma with the man who had uncovered the bowl. Why wasn’t the vessel destroyed? Why only punctured? “Simple,” he replied. “Just look up Mishnah Kelim 2–3.” When I

returned home I checked his reference in the Mish-nah, the earliest codification of rabbinic law. The Mishnah states that a pierced clay vessel is consid-ered broken; it is therefore pure and insusceptible to impurity, providing that the hole is large enough to disable the intended use of the vessel. It is then permissible to repair and reuse the punctured ves-sel. This might explain this strange phenomenon of punctured vessels at Maresha if it were not for the fact that the Mishnah was not redacted until about 200 C.E. Our Maresha examples are much earlier—from the third–second centuries B.C.E.—and at a

HOLEY VESSELS. The Maresha cave excavations have unearthed hundreds of Hellenistic-period jars, bowls, pots and juglets deliberately punctured with small holes that would have rendered the vessels unusable. This puzzling phenomenon bears striking similarities to a purification ritual described in the Mishnah (the earliest codification of rabbinic law, redacted c. 200 C.E.) in which ritually unclean vessels could be made pure again by piercing them with small holes, after which the vessels could then be repaired and reused. The resemblance suggests that the purification rites of the Idumeans may have been similar to those of the Judeans.

QOS IN A CAVE. Found throughout the Maresha caves are non-figurative, stylized depictions of the Edomite (and later Idumean) deity Qos. This approximately 4-foot-tall, cross-shaped image carved into a recess probably representing Qos features a rectangular lower body and outstretched arms, together with a simple blockish head adorned with stylized eyes and nose. Such aniconic depictions may indicate that the Idumeans, like their Judean neighbors, had a strong aversion to figurative idols.

co

ur

Te

Sy

aS

Sa

F S

Te

rN

/ar

ch

ae

olo

GIc

al

Se

MIN

ar

S I

NS

TIT

uT

e

co

ur

Te

Sy

IaN

ST

er

N/a

rc

ha

eo

loG

Ica

l Se

MIN

ar

S IN

ST

ITu

Te

biblicalarchaeology.org/mareshaVisit us online to learn how you can volunteer for Maresha’s Dig-for-a-Day program.

c o n t i n u e s o n pa g e 7 6

76 S e p t e m b e r / O c t O b e r 2 0 1 3

site that was predominantly pagan. Since no literary or archaeological

evidence of this practice has been dis-covered in a Jewish context from this period, the question arises: Were the Idumeans involved in a purification rit-ual (albeit with symbolism unknown to us today) centuries before the Jews?

The final question I will discuss relates to the Edomite and later Idu-mean god, Qos. Depictions of Qos at Maresha are schematic or aniconic. Sev-eral depictions like this are incised on some of the walls of the subterranean complexes. Others were found on stone reliefs. Does this suggest something akin to a non-corporeal deity?

Another strange thing about Qos relates to the Bible: He isn’t there. This is in con-trast to the Moabite god Chemosh who is mentioned eight times in the Bible and the Ammonite god Milcom who is mentioned three times. Is the absence of any refer-ence to Qos in the Bible a case of benign neglect?

Can we put all this together? The dis-covery of 17 circumcised phalli from a period before the Hasmonean conquest of Maresha, ritual immersion baths, ves-sels punctured for no apparent reason and therefore perhaps interpreted as connected to a cultic/ritual practice, ani-conic images of the deity, and a Biblical relationship with the Edomite/Idumean deity that can be characterized as non-antagonistic. Is all this just coincidental?

Or does all this suggest the possibility of a connection between Idumean and later Judean rituals prior to the Hasmo-nean conquest of Maresha in 111 B.C.E. and centuries before some of these reli-gious rituals became evident in Judea?

Was there a Judaizing tendency in Idu-mean society at Maresha even before the Hasmonean conquest of the city? Or were these proto-Pharisaic rituals, as it were, practiced by a small minority of Judeans residing in Maresha at that time?

As I said at the beginning of this article, although archaeological excava-tions provide us with new answers, just as often they provide us with new questions.

continued from page 39So it is at Maresha. a1 The Zenon papyri (c. 259 B.C.E.) testify to the intensive commercial ties between Maresha and the Ptolemies.2 Ian Stern, “The Population of Persian Period Idumea According to the Ostraca: A Study of Ethnic Boundaries and Ethnogenesis” in Y. Levin, ed., A Time of Change: Judah and Its Neighbors in the Persian and Early Hellenistic Period (London: T&T Clark, 2007), pp. 205–238.3 Antiquities 13.9.257–258.4 Geography 16.2.34, in Menahem Stern, ed., Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism, vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1974), p. 306. [IA: please confirm]5 Antiquities 13.15.395–397.6 Frederick J. Bliss and R.A.S. Macalister, Excava-tions in Palestine During the Years 1898–1900 (London, Palestine Exploration Fund, 1902), p. 56. 7 Tacitus, Histories 5.5, in Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism, vol. 2, p. 281.8 Amos Kloner, Maresha Excavations Final Report I: Subterranean Complexes 21, 44, 70, IAA Reports 17 (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2003), pp. 15–16; Amos Kloner and Yoav Arbel, “Maresha Area 61 (Subterranean Complex),” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 17 (1996), pp. 157–162; A. Kloner, “The Identity of the Idumeans Based on the Archaeological Evi-dence from Maresha” in Oded Lipschits, Gary N. Knoppers and Manfred Oeming, eds., Judah and the Judeans in the Achaemenid Period (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2010), pp. 565–566, 570; and I. Stern, “Ethnic Identities and Circumcised Phalli at Hellenistic Maresha,” Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 30 (2012), pp. 57–88, based upon a paper delivered at the ARAM conference “The Edomite (Idumeans) and the Nabataeans” in Oxford, England, July 2012.9 See Ian Stern and Vered Noam, “Holey Vessels of Maresha,” forthcoming in ARAM periodical.