Morte D'Arthur

Transcript of Morte D'Arthur

Who controls destiny?: fortune, prophecies, and freewill in Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur

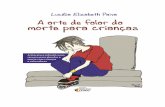

King Arthur on the Wheel of Fortuna. London, British library, MS Additional10294, f. 89

Abstract: The ideas of Fortuna and Providence participate in thenarrative of Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur providing structural patternsand express the popular idea of divine powers influencing humanlife and leading man through his destiny. Malory combines his ownfeelings and impressions about the time when he lived with thepopular perception about destiny and free will to create arealistic moral outlook over the political system of the late XVcentury. To a great extend he adopts Thomas Aquinas idea that Godprovide man with good and bad thus giving him choices andproviding justice. By including elements such as prophecies,prophetic dreams and trial by battle Malory never lose theconnection between divine forces and human’s life. Personallyinterested in every aspect of man’s life is only the goddessFortuna. Although Malory obscures her participation behindChristianity and reduces it to her function she still reachesevery aspect of life. The image that he suggests is close to theBoethian idea of adverse goddess under the influence of God.Merlin is the one who acts as instrument of these divine powersand directly leads Arthur through his destiny. The King ispersonification of his political and moral system and through thespin of the Wheel of life he becomes merit of time and structure.Lancelot, although exemplar knight never achieves happiness inhis earthly life mainly because always place his life under theinfluence of external powers- chivalric code, woman, God. Galahadon the other hand become happily married and provides example ofsuccessful life outside of the system of the Arthurian court. Hisdeath influences to a great extend the final disintegration ofthe Round Table fellowship but Mordred’s treason is what presentsfree will and destiny at the same time.

I. Introduction

What we have today as Arthurian literature is a probably the

biggest and most popular narrative account in history. The

stories about King Arthur and the Round Table Knights are product1

of historical and cultural evolutions, and bear the influences of

many traditions and deliberate alterations. The beginning can be

traced back to ancient Celtic mythology since when the narratives

have suffered a long process that changes the story

significantly.

My dissertation concentrates on one particular version of

these stories, the late medieval composition, Morte D’ Arthur

composed by Sir Thomas Malory. Although there are historical

records for three people who might be this Malory (as I discuss

below) we can be sure that the Morte was written during a time of

great conflict as the Hundred Years War between England and

France drew to an end and the War of the Roses began. We also

know that Malory himself had a fairly eventful political life,

including spending time in prison. His version of Arthur’s tales

is not just knightly stories, but also reflect the social and

cultural times in which he lived. I will focus in particular on

the ideas of who controls an individual’s life – destiny,

fortune, or a person’s free will. I will relate these themes to

the figure of the goddess Fortuna. Although she is not an active

personage in Malory’s story, elements of her tradition persist.2

So the question is who is in control of human destiny? Is there

free will or is everything ruled by predestined path?

In order to understand that I will include brief discussion on

the image of the goddess Fortuna in one of the most important

earlier medieval writing- Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy. In Ethics

and Eventfulness John Mitchell made a full analysis of the idea of

destiny and fortunes in his text and some other key medieval

writings including Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde where Fortuna guide

Pandarus and rules over the affair between the lovers. In these

texts Fortuna appears as a servant of the Christian God,

combining the functions of several pagan deities1 and the idea of

the Wheel of life2. The tradition of the goddess Fortuna provides

answers to questions about the purpose of human life, free will

and destiny in a time when the world becomes more and more

anthropocentric. Malory’s own struggles with the new perspectives

1 More about Fortuna and the functions that she assumes from pagan deities such as Fate, Astrology, Adventure , etc. can be found in Patch, H., The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Literature, (Cambridge, 1927)2The Wheel of life is a representation of the cyclic view of life and the structured pattern form birth to death. It is controlled by universal divine forces and unlike the Wheel of Fortune can’t be influenced by anyone. More on the subject in general can be found in Patch, H., The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Literature, (Cambridge, 1927). Norris Lacy’s edition The Fortunes of King Arthur (Cambridge, 2005) discusses the problem of Fortuna and the Wheels regarding the Arthurian tradition from Nennius to Malory.

3

and political powers are reflected in his text and the characters

that he creates, especially Arthur as the king and representative

of the world in Morte and Merlin- advisor and prophet who leads

the king to his destiny. The result should be to find out how

Malory adapts the ideas of fortune and free will to the changes

in the humanist theory of late medieval age.

II. Arthurian tradition and Sir Thomas Malory

In his book about the evolution and development of the

Arthurian literature, Roger Loomis3 traces the story to its

ancient sources. He analyzes the routes that take every main

character to become the one that we know today. A similar thing

is done by Lori Walters in her introduction to Lancelot and Guinevere:

a casebook. She is interested in the dissemination of the story

regarding the characters of Lancelot, Guinevere and Arthur.

Arthur’s first written account by the Welsh cleric Nennius in the

Historia Brittonum is dated sometimes in IX century. Before that,

Arthur exists in folklore and tales and is depicted as the

British king who fought against the Saxon invasion in VI century.

Guinevere appears as his wife ca. 1100 in the Welsh Culhwich and3 Loomis, R. S., The development of Arthurian Romance, (London, 1963)

4

Olwen, but is known before that in tales about abducted women or

an otherworldly mate that become a wife of an earthly man.

Lancelot on the other hand bears the tradition of the Fair

Unknown- the brave knight who appears in moments of need. He

stays unnamed until the early XII century when Chrétien de Troyes

identifies him as Sir Lancelot4.

One of the most important characters for my analysis is

Merlin. Loomis finds him first in the Welsh tradition where he is

known as Myrddin. Later on he is merged with the image of the

madman and prophet Lailoken. According to Loomis, Merlin was

associated with Arthur by Geoffrey of Monmouth in early XII

century, but other scholars5 state that he is associated with the

king from the earliest written record, Nennius’ Historia Brittonum.

Geoffrey of Monmouth composes Historia Regum Brittaniae ca. 1130 and

constructs the modern interpretation of Merlin as a Christian

prophet, scholar and advisor of Arthur. In Geoffrey’s version the

king’s downfall is explained by Guinevere’s treason. Her fairly

4 Walters, L. J., ed., Lancelot and Guinevere: a casebook, (New York and London, 1996), Introduction, pp. xii- xxxi5 Littleton, C. Scott and Malcor, Linda A., ‘Some notes on Merlin’, Arthuriana, Vol. 5, No 3, Fall 1995, p.87

5

positive image in the Welsh tradition now turns to the worse and

she helps Mordred to take over Arthur’s kingdom6.

The most popular interpretation is proposed by the XII century

French author Chrétien de Troyes. His verse romances become very

famous outside of France and had been translated and influenced

Arthurian stories in Italy, Spain, Germany and even Scandinavia

as well as Britain. It can be said that he made the king into a

popular fiction character and he is the one who introduce the

love triangle between Lancelot, Guinevere and Arthur as the

reason for the downfall of the Round Table. As Walters points

out, that is his answer to the Tristram- Isode- Mark triangle7.

Tristram and Isode have a tradition of their own that

eventually become part of the Arthurian literature. Tristram

originates in the Pictish king Drust or Drustan, son of Talorc

lived in VIII century. He is linked with Isode and Mark in the

Welsh tradition where the love story is added and fully developed

in XI century in France. Although the version by Chrétien de

Troyes is lost, the German author Gottfried von Strassburg,

6 Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the King of Britain, trans. and ed., Lewis Thorpe, (Harmondsworth, 1980), p. 2577 Walters, L. J., ed., Lancelot and Guinevere: a casebook, Introduction, p. xiii

6

influenced by the French romance tradition, compose prose Tristan

around 12108.

This brief account of the Arthurian literature leads us to

the last medieval British interpretation of the legend. Sir

Thomas Malory composes his Morte D’ Arthur in 1469- 70 while in

prison. Almost nothing is known about his life as most of the

information that we have comes from his book, so scholars argue

about identifying the author as one of the three Thomas Malorys

who lived in that time.

Most popular and accepted is Sir Thomas Malory of Newbolt

Revel or The Warwickshire candidate9. He lives in the right time,

has the necessary title and military experience, but his track

record of different crimes poses a moral problem. Some scholars

find it difficult to accept that someone with such a criminal

background could compose a story about noble chivalry and honour.

In his study The Ill- Framed Knight William Mathews suggests Thomas

Malory of Studley and Hutton, also known as the Yorkshire

8 Loomis, R. S., The development of Arthurian Romance, (London, 1963), pp. 79- 829 Other studies discussing the identity of Sir Thomas Malory are: Vinaver, E.,The works of Sir Thomas Malory, (Oxford, 1967); Filed, P. J. C., The life and times of SirThomas Malory (Cambridge, 1993); Archibald, E., A Companion to Malory (Woodbridge,1996)

7

candidate, as the one who composed Morte D’ Arthur. Although there

is limited information about him, Mathews uses linguistic

analysis to place the text in the right area for this author

geographically. However Thomas McCarthy argues that this Malory

was too young at the time of the composition of the book and

there is no information about imprisonment. It seems that

McCarthy prefers the third candidate as the Thomas Malory who

composes Morte D’ Arthur. Sir Thomas Malory of Papworth St. Agnes

(The Cambridge candidate) is the right age- according to McCarthy

he would have been 45 years old by the time of composition. In

one document he is referred as a knight and it is possible that

he was in prison although there is no evidence for that. McCarthy

points out that this Malory is also linguistically and

geographically acceptable and he even compare him with Sir

Tristram- both receive education in France, thus suggesting that

in the characters of Morte D’ Arthur we can find personal

characteristics of the author10. Any of the three candidates is

possible as the Thomas Malory who composed Morte D’ Arthur but most

importantly they all have a political career, lived in the same

10 McCarthy, T., An introduction to Malory, (Cambridge, 1991), p. 165- 166

8

time period, probably been in prison and the message that we will

find in Morte regarding the purpose of human life and human

destiny can be relevant to each of them. Although from Morte D’

Arthur we can’t say if Malory is Lancaster or Yorkshire in the War

of the Roses, McCarthy’s suggestion about his relation to the

character of Sir Tristram shows that Malory alters his characters

to present his own personal ideals and beliefs. Moorman’s opinion

is also relevant here; he states that in fifteenth century

chivalry lost its military and political importance, but to

Malory it was embodiment of stability and standards which were

absent in his life.

Malory is not an author in the modern sense of the word.

Writers from the medieval period were proud to borrow from famous

sources, thus giving more authority to the narrative. He even

pretended to borrow for that reason alone. As a result the whole

book is “second- handed”, and some parts are straightforward

translation11. Malory drew little from his English sources. The

Alliterate Morte Arthur and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur are composed sometimes

in the late XIV century and on them Malory based his Tale of the King

11 Ibid, p. 134

9

Arthur and Emperor Lucius, Tale of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere, and the

Death of Arthur. Aside from that he rarely uses any other English

sources, but often relies on “the french book”. It is however

not just one book that Malory uses for completing Morte D’ Arthur.

The Suite du Merlin, prose Lancelot and Tristram, Queste Del Saint Graal and

Le Morte le Roi Artu are proven to be his main sources12.

Although he is not the original author of the story there

are some parts of the text that are his innovation and artistic

interpretation. Most of the battle scenes come from Malory’s

imagination and scholars generally agree that his main interest

lays there- in battles and knightly adventures. In particular the

source for his Tale of Sir Gareth is still unknown- and some major

scenes such as the healing of Sir Urray are probably his

innovation, serving to prove his point about chivalry, love and

religion. What Malory changes, omits or highlights in terms of

prophecies and ideas of individuality and free will is the main

question that will be discussed in this dissertation.

12 Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur. The Winchester manuscript, ed., Cooper, H., (Oxford,1998), Introduction, pp. xix- xxi

10

The first edition of Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur is published in

1485, only fifteen years after its composition, by William

Caxton, the first English printer. Although he was persuaded by

“many noble and divers gentlemen of this realm of England” to

print an edition of knightly tales about “the Sangrail, and of

the most renowned Christian king”13, the immediate impact of this

is that Caxton makes Morte easily accessible and even more

popular. Caxton and Malory address the elite social and political

groups, but in fact reach a wider readership of anyone who could

read and had the money to buy а book. This means that Malory is

presenting ideals of knighthood as he saw them to a wider public

and by placing King Arthur among Alexander the Great and

Charlemagne, Caxton gives him historical authenticity and made

him a moral example of a fifteen century social and political

life. By the first part of XVII century Morte is published a few

more times but the interest gradually subsided. The Renaissance

public was not interested in medieval chivalric romances and even

critiqued their immorality and views them as propaganda of the

13 Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur. The Winchester manuscript, ed., Cooper, H., (Oxford,1998), p. 529

11

popish doctrine14. That is until the discovery of the Winchester

manuscript in 1934. This threw new light on Malory’s original

text. An extensive research of the manuscript made by Professor

Eugene Vinaver led to his edition of The works of Sir Thomas Malory

combining Caxton’s edition and the manuscript. J. Bennett says

that this edition “give a fresh impetus to Arthurian and in

particular to Malorian studies”15. Vinaver’s intention is to

produce a text that is the closest to what Malory intended to

write and since its first publication this has been one of the

main sources in studying Malory and Morte D’ Arthur.

However, for my purposes the best source is an edition of the

Winchester manuscript without Caxton’s alterations. That is the

closest version of the text that we have to the original of Tomas

Malory. My primary source and citations come from the edition of

The Winchester Manuscript published in 1996 by Helen Cooper. She

presents the text in modern English punctuation and grammar, thus

making it easier to read and cite and provides useful commentary

14 Dean, C., Arthur of England. English attitude to King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table in the Middle ages and Renaissance (Toronto, Buffalo, London, 1987), p. 10415 Bennett, J. A. W., Essays on Malory (Oxford, 1963), Preface, p. v

12

which helps understand how Malory developed the Arthurian tales

into his Morte D’ Arthur

III. Historical context

The end of the middle ages is a period marked by the chaotic

process of transition to Renaissance ideals. Man becomes the

centre of the earthly universe and the system that provided

structure in the past, now becomes inadequate to lead to

salvation and give answers to existentialist questions. With the

revival of classical humanist ideas comes the concept of human

free will and individuality despite the Christian or political

system of the middle ages.

Robert Merrill suggests an interesting approach that will

give a better understanding, not just about Malory’s moral

outlook, but also an answer for this dissertation proposed

question. He writes one of the most important studies for

discussing the changes that arise at the end of the medieval

period. His approach is based on psychoanalytical and

sociological analysis combined with the historical knowledge for

Malory’s life and time. He examines the struggles of the Knights

13

of the Round Table to accommodate the known cultural code of

chivalry to the new renaissance perception of human life as a

question of free will where man is more important than the

political, social or religious system.

To fully grasp what Merrill calls “cultural crisis” in Morte we

need to know the historical context in which it is composed. The

fifteenth century proves to be a period of great conflict.

England is in the Hundred Years’ War at the time when Malory is

supposed to be born and soon after its end the War of the Roses

start. This leads to a difficult and dangerous life for a knight

in the late middle ages; as Jeffrey Morgan points out, this is a

time of rapid political, social and religious changes and Malory

marks a point of balance between Medieval and Renaissance

perceptions and ideas16. It is a time of critical shift between

“institutionally controlled system of moral and metaphysical

principles to a somewhat chaotic notion of individualism”17. So

it is not surprising when some scholars speak of Malory’s

nostalgia for the chivalric code and structured way of life.16 Morgan, J., Malory’s double ending: the duplication Death and Departing ined. Hanks, D. T., Sir Thomas Malory. Views and Re- views (New Your, 1992) p. 10017 Merrill, R., Sir Thomas Malory and the cultural crisis of late Middle Ages, (New York,1987), p. 5

14

Christopher Dean, in his study Arthur of England suggests that

Malory composes Morte D’ Arthur as a moral lesson for his

contemporaries. He argues that Malory’s knights are still firmly

in the middle ages but they see that the chivalric code fails

them, and are unable to find new code or system to belong to.

Johan Huizinga speaks of the idea of chivalry as socio-

cultural structure in late middle ages and Malory use this as

basis for his Morte D’ Arthur. The code that it presents was as

strong as religion and XV century was a time of renewed interest

in it. Huizinga says that this is a “naïve and imperfect prelude

to the renaissance”18 but also a very influential way of life. In

his times the idea of chivalry is the clearest code that he could

refer to. The Pentecost Oath that Arthur and the Round Table

Knights swore is simple- honour, friendship and mercy19. However

by the end of his book Malory realizes that this code is

superficial and cannot be fulfilled by human sinners. His knights

stand before a system that can’t provide salvation despite their

best efforts. Both Christian and chivalric codes prove to be

18 Huizinga, J., Man and ideas, (London, 1960), p. 19719 Le Morte Darthur, III. 15, p. 57

15

inadequate and many knights realize that at last. They are faced

with the medieval beliefs that the institution, political or

religious, is stronger and more important than the individual. At

the same time these institutions fail their ultimate test (The

Grail Quest) and the Round Table knights find themselves lost in

the chaos. The concept of free will and individuality is hardly

seen in Morte but it exists, behind the Grail Quest and Merlin’s

prophecies, Malory gives his knights choices.

Merrill’s point is similar- Malory tries to find a middle

ground with his characters- between the system and the

individual, between medieval and renaissance ideals. He concludes

that Malory belongs to the “analytic or deconstructive tradition

of the later middle Ages”20 and Morte D’ Arthur is not just about the

tragedy of the Round Table fellowship with its transcendental

ideas but also about the options of here and now that some

knights seem to find. As Elizabeth Pochoda points out in her

study Arthurian Propaganda for the later English Middle Ages, the

Arthurian stories had status of history21. Malory however

20 Merrill, R., Sir Thomas Malory and the cultural crisis of late Middle Ages, p. 421 Pochoda, E., Arthurian Propaganda, (Chapel Hill, 1971), p. 29

16

idealized that world to the utmost and fails to respond to the

personal and individual aspects of life. Pochoda’s approach

focuses on the political systems and the ideals of life as

historical fact and her work sheds light on the socio- cultural

aspects reflected on Malory’s text. A consequences of her study

is that prophecies and dreams in Morte D’ Arthur can be included in

the sphere of the popular belief system still existing in late

middle ages. Malory uses them as basis to create a symbolic

universe expressing his ideas about fate and purpose of human

life in his controversial times. My analysis will show that not

all of Malory’s knights operate within the bounds of this kind of

medieval thinking. Some of them overcome the idealized

restrictions of the Round Table fellowship and head for a life of

personal choices and responsibilities, something often regarded

as a mark of modern mentality. It is in these changes to the

concept of the individual as someone in control of their destiny

and the need for personal responsibility that we can see Malory

drawing on and changing the concept of Fortune in his text.

IV. The tradition of the goddess Fortuna in Morte D’ Arthur

17

To begin with Fortuna has a long tradition in Arthurian

literature. In a study edited by Norris Lacy we see the

interactions of that tradition from Nennius’s Historia Brottonum to

Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur. In his book The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval

Literature, Howard Patch tries to summaries every possible function

of Fortuna that survives to the medieval period. Fortuna

successfully implements itself into Christianity as a servant of

God who personally influences human destiny by assuming functions

of other deities, all of whom had some relation to human well

being and fate. As a result the medieval person sees Fortuna in

almost every aspect of life- she guides travellers in sea and

land, sets adventures, intervenes between lovers and even assumes

some control over death. It is a conventional medieval view that

she operates under God’s rule and kings and conquerors are prone

to fall under her influence22.

IV.1. The Wheel of life and the Wheel of Fortune

Patch finds traces of her cult and functions as long ago as

the orphic mythology where is mentioned the Wheel of life. But

the image that is most popular is created by Boethius in his

22 Patch, H., The goddess Fortuna in medieval literature, (Cambridge, 1927)

18

Consolation of Philosophy. The ideas set out in his text become so

influential that even today they are used as a basis for every

analysis of Fortuna. The work is composed in the first quarter of

the VI century in Latin while Boethius is in prison, awaiting his

sentence. It is divided into five parts in prose and verse

producing a dialogue between lady Philosophy and the author.

Boethius expresses his sorrow for the misfortunes in his life

that until this moment was pleasant, politically and socially

productive. Throughout the text he is reminded that every gift

given by Fortuna is liable to change and can be taken back.

Philosophy reminds him that earlier in his life Boethius receives

plenty of gifts and so now complaint is not justified23. Boethius

creates an image of a fickle, unstable goddess, who spins her

Wheel and controls human life, gives and takes, and leads a

person through his destiny to his end on her own accord and

without any feeling:

So with imperious hand she turns the wheel of changeThis way and that like ebb and flow of the tide,

And pitiless tramples down those once dread kings,Raising the lowly face of the conquered-

Only to mock him in his turn;

23 Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. S. J. Tester (London, 1973), Bk. II, v. I, pp. 179- 181

19

Careless she neither hears nor heeds the criesOf miserable men: she laughs

At the groans that she herself has mercilessly caused.So she sports so she proves her power,

Showing a mighty marvel to her subjects, whenThe self- same hour

Sees a man first successful, then cast down.24

Boethius explicitly shows that Fortuna has full control over

the Wheel and can change its direction whenever she wants thus

bestowing or withholding gifts of love, happiness, and riches. At

the end he concludes that all fortunes are good, despite how man

sees them, because they are divinely bestowed as a reward or

punishment thus successfully implementing her in the Christian

tradition as servant of God. In the quote above Boethius refers

to Fortuna’s Wheel that follows her capricious nature which is

something that we see in Morte D’ Arthur- references to events

happening by adventure or by fortune are the clearest example.

But in the pattern of Arthur’s life we can see the interaction

between courses followed by two Wheels: the line from birth to

death, giving an impression of both progress and cycle

implemented in the idea of the Wheel of life, and the random

turning of the Wheel of Fortuna in which any gain can be easily24 Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, Bk. II, v. I, pp. 179- 181

20

turned into loss. It is important to distinguish between the

Wheel of life and the Wheel of Fortune, although for many

medieval authors there is no difference. Malory certainly refers

to Fortuna and her Wheel in many occasions but the overall

structure of the book follows a universal pattern implemented in

the concept of the Wheel of life. The book starts with the events

around Arthur’s conception. The movement upwards encompasses the

time between Christmas when Arthur first pulls the sword out of

the stone and establishes himself on the throne as a king of

Britain. The highest point of the cycle is reached when he

becomes Emperor and after that the movement continues in the

downfall until the death of Arthur. Malory uses the life and

death of Arthur as a mark of the value of time and a symbol of

the late medieval social code presented in Morte D’ Arthur; a code

which suggested that any success in life is temporary and could

not be relied upon.

Christopher Dean applies the idea of the Wheel of life, with

its constant and predictable movement to the chivalric code and

the system of the Arthurian world25. First Malory shows а chaotic

25 Dean, C., Arthur of England, pp. 93- 94

21

universe ruled by emotions and magic. This is the rule of Uther

Pendragon who starts a war because his adulterous love to lady

Igraine and conceives a son through magic and deceit. His death

brings even more chaos when barons and lords fight for the crown.

By establishing the Round Table and the Pentecost Oath Arthur

provides justice and mercy, but above all he establish order. The

main achievement of the chivalric code may be seen in the Grail

Quest- accepting the Quest provides the opportunity for

expressing true virtues and high religious devotion. The end of

the Round Table comes with the Quest when knights’ individual

failures overwhelm the ideals of the fellowship. After the end of

the Grail Quest the Arthurian society falls apart very fast,

without a chance to find salvation as group or a new ideal. Dean

finds two reasons for that. First there is The Grail Quest itself

which fails to bring about any changes in their lives. Only

Galahad completes the Quest and ascends to heaven, all the other

knights return to their everyday life or die during the Quest.

Dean separates religious and secular experience pointing out that

Lancelot returns to the point from where he started- in Camelot

22

and with Guinevere26 in a society ruled by internal struggles,

personal conflicts and mutual hatred. So to a great extent

chivalry loses its lure without its greatest purpose- providing

meaningful life and path to salvation. Second and most

destructive however, is the complete devotion to an idealized

woman. Lancelot’s love for Queen Guinevere is stronger than his

social obligations as required by the Pentecost Oath and

ultimately leads to the full destruction of the chivalric order.

Arthur himself is the personification of the late medieval

society- idealized but incapable of containing the order that he

created. By presenting him through the structure of the Wheel of

life Malory express the idea that everything follows a natural

course and through Arthur’s downfall he symbolically expresses

the crumbling universe of late fifteenth century. Importantly,

Morte D’ Arthur doesn’t end with Arthur’s death and vague promise

for the return of the king. Not even with the deaths of Lancelot

and Guinevere. Malory gives us the name of the next king-

Constantine and stories of some of Arthur’s knights who went to

the holy lands to fight the Turks or returned to their home

26 Ibid, p. 96

23

countries. Malory thus leaves the end open for the next king with

the new system and adventures.

T. L. Wright also observes this idea and proceeds to explain

that Malory’s narrative follows a course form disorder and

rebellion, to Pentecost Oath of chivalry to final battle. The

Oath itself is a result of the wedding quest and arises from the

adventures that close this first section of Morte D’ Arthur27.

Wright’s analysis suggests that the beginning of Morte describes

a time when the chivalric code flourishes and the Arthurian

political and social system is established. When Merlin leaves

the narrative at the end of this part the notion of events is

already set by his prophecies. The following tales describe the

Arthurian world to its greatest point- the successful war against

Rome and the Grail Quest where we see also the signs of its end

in the speech given by Arthur where he explicitly say that his

knights would never be together again. He does not refer only to

them being physically in the same place but also in the same

27 Wright, T. L., The Tale of king Arthur: beginning and foreshadowing, in Luminasky, R. M., Malory`s originality. A critical study of Le Morte Darthur (Baltimore, 1964), p. 21

24

frame of mentality where the fellowship is above individual

conflicts.

In other words Arthur’s Wheel of life and the wheel of the

system that he represents are similar if not the same and follow

the same course- from chaos to order to chaos. They follow a

predictable path and Malory use it as a structure in which he

inserts all other elements of destiny and free will to provide

his readers with complete picture of the common perceptions about

the purpose of human life in late XV century.

IV.2. Functions of Fortuna in Morte D’ Arthur

Howard Patch distinguishes nine functions of Fortuna within

Christianity and we will see how they are used by Thomas Malory

in Morte D’ Arthur. Some of them overlap other functions and it is

hard to separate them clearly, but inevitably Fortuna intervenes

in every aspect of human life. Originally her main interest is in

the king and his destiny, but in Morte she assumes more general

role and influence the life of every knight.

Fortuna of love intervenes in love affairs by bestowing or

withholding gifts, helping lovers or not. Sometimes she is

distinguished from Love as Fortuna usually is the one who prevent25

the lovers being together. This aspect is linked to the role of

the lady in courtly love whose rejection can inspire nobility,

bravery, adventures and knightly deeds. Richard Barber28 points

out that Malory is uneasy with the emotional and courtly aspect

of chivalry and as a result he is not very interested in love

affairs. He has no choice especially when has to deal with

Lancelot and Guinevere, but mostly this aspect of Fortuna is not

present in his Morte.

Fortune of the Sea is something that becomes very popular

and important as a theme. Personal life and career are compared

with a vessel, boat or ship that is left in the merciful hand of

a violent sea. Fortuna is in control of the winds and streams.

Man is completely in her mercy as he can’t do anything to control

the elements so this concept excludes free will altogether. As a

ruler of the sea Fortuna appears in several scenes in Morte when

the character physically is incapable of taking any control over

the boat. Tristram sails to Ireland when he is injured and the

most important example is the saving of Mordred as baby who is

put on a ship by Arthur in his attempt to destroy a threat to his

28 Barber, R., Chivalry and the Morte Darthur, in Archibald, E., and Edwards, A. S. G., eds., A companion to Malory (Cambridge, 1996)

26

kingdom29. As was said before Malory wants to provide his knights

with choices and free will so in moments when the tradition of

Fortuna gives her full power he provides reasonable explanation

on why they submit to her.

Fortune as a Guide is always present. She helps the knight

to find their right way and, as Patch says, she provides the

adventures. So every adventure that a knight undertakes is

governed by Fortuna. Every mention in Morte of something

happening by chance, by fortune, or by adventure is actually an

obscure way of saying that it is the doing of Fortuna. This

function is close to the idea of Fortune of Combat that is

perhaps the most popular in Morte. Malory describes many battles

as he is a warrior and that is his main interest. This Fortune

not just starts wars but also act as a judge. Here she is in

conflict of the divine judgment provided by God in trial by

battle where the final ordeal is not based on strength and

experience but on divine vindication for the rightful. Although

Fortuna acts under God’s superiority Malory describes a scene

where the victory is unjust. King Mark killing Sir Amant “by

29Le Morte Darthur I. 27, p. 31

27

misadventure”30 provides example of Fortuna’s intervention in

battle and as Kennedy says leaves us with faith that this is part

of a divine plan directing all things31. Here Fortuna also takes

responsibility for death. This is an old association when death

and Fortuna work together but by her Wheel the goddess can single

handedly cause death which gives her certain superiority.

Fortune of Fame is the one who is responsible for knightly

worship. This function may be combined with the idea of Personal

Fortuna. It was already said that Fortuna is interested in

individual fate so every one of her functions has personal

characteristics. She performs deeds assigned by divine powers and

her action serves to provide the fulfilment of a predestined

path. In Morte D’ Arthur Malory use the idea of destiny through the

image of Merlin and his prophecies but he also leave space for

free will and chance.

IV.3 Ruling powers in Morte D’ Arthur

Jane Bliss observes that two ruling powers exist in Morte D’

Arthur- God and Fate (Destiny, Fortuna). God gives the code of

30 Le Morte Darthur, X. 14, p. 23431 Kennedy, B., The idea of providence in Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, p. 12

28

Christian chivalry, set the rules and punish sins. As we will see

he also gives power to Merlin, so he can perform miracles and

through divine knowledge lead Arthur to his destiny. Fortuna

appears whenever some event happens “by fortune” or “by

adventure”. Jane Bliss says that “the force of destiny is

introduced as soon as Mordred’s begetting is accomplished”32. She

relates the downfall of King Arthur and the Round Table

fellowship to only one side of Fortuna, the one that brings bad

luck and misfortune. For Bliss the idea of Fortuna is appealing

because she is the executor of the divine will; she is the one

who is personally interested in human life and fate and actively

perform punishment or bestowal through her Wheel. But Malory

presents more complicated world of popular beliefs in divine

forces that can’t be separate only into good and bad. Some parts

of Morte D’ Arthur are close to the orthodox position of St. Thomas

Aquinas who describes a God who offers good and evil options

between which man can choose. On the basis of his decision

follows a man’s punishment (or reward) in life and afterlife.

This theory assumes the existence of free will where man has a

32 Bliss, J., Prophecy in the Morte D` Arthur, Arthuriana, Vol. 13, No I, Spring2003, p. 10

29

choice and some control over his destiny but just as Fortuna’s

words in Consolation suggest: “For this is my nature, this is my

continual game: turning my wheel swiftly I delight to bring low

what is on high, to rise high that is down. Go up, if you will,

but on this condition, that you do not really think it wrong to

have to go down again whenever the course of my sports

demands”33. So on a basic level man can choose to provide his

life in the hands of the goddess or take personal responsibility

for it.

The role of Fortuna is obscured behind Christianity and

religious zeal. Malory’s characters often exclaim the name of God

and Merlin channels divine powers when he performs miracles: “and

God and I shall make him to speak”34. Malory’s use of Fortuna is

implied rather than fully allegorical. By using terms such as

“chance”, “adventure” and “fortune” or “misfortune” he shows that

there is a power ruling over man’s actions but for a XV century

audience Fortuna is suitable image for that, so that Malory does

not need to introduce her as a figure in the text for his readers

33 Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy, Bk. II, pr. I34 Le Morte Darthur, I. 4, p. 7

30

to think of her as events unfold. However, Moorman argues that in

Morte D’ Arthur the tragedy lies in man himself not external powers.

The idea of Fortuna is used more as a description for the

irrational chances in life than actually to explain it. Guinevere

reaches this conclusion much later when she says to Lancelot:

“for through thee and me is the flower of kings and knights

destroyed”35 and ultimately takes responsibility for the death of

Arthur and the collapse of the Round Table fellowship. On the

other hand Lancelot never takes personal responsibility for his

actions. He follows her example and devotes his life to hermitage

once again submitting to external influence.

Just like Boethius, Malory does not give Fortuna full power

over human destiny. She acts under the superior rule of God and

Providence. They are universal powers and rarely deal with human

beings and their every day struggles, unlike Fortuna. This

establishes the basic idea of separate powers- individual and

universal- which are responsible for different aspect of human

fate. Fortuna governs earthly life through the spin of her Wheel.

Providence and God conduct control over the immortal soul. This

35 Le Morte Darthur, XXI. 9, p. 520

31

separation is observed by Boethius in Book II of Consolation of

Philosophy where Fortuna has power only over the earthly body. Her

powers cause after death: “it is clear also that the felicity

which Fortune bestows is brought to an end with the death of the

body”36. In other words, the soul survives after physical death

and this concept of body and soul as separate areas of divine

influence is seen in the double ending of Morte D’ Arthur. The

battle between King Arthur and the traitor Mordred lead to their

physical deaths. Arthur is badly wounded and after ensuring that

his sword Excalibur is returned to the Lady of the Lake, he

departs on a barge, accompanied by Morgan le Fay, The Queen of

the Northgales, and the Queen of the West lands and Dame Nenive.

Whitaker point out that the story cannot be completed if

Excalibur is not returned to the Lady of the Lake. She connects

the disposal of the sword with Arthur’s survival37. Arthur’s last

words to Sir Bedivere are:”For I will into the vale of Avalon to

heal me of my grievous wounds; and if thou hear never of me, pray

for my soul.”38 Soon after that Sir Bedivere finds a chapel and

36 Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy, Bk. II, pr. 437 Whitaker, M., Arthur’s kingdom of adventure. The world of Malory’s Morte Darthur (Cambridge, 1984), p. 2838 Le Morte Darthur, XXI. 5, p. 516

32

the hermit explains that some ladies brought a body to him for

burial. However we are never told for sure that this is Arthur.

Malory leaves the question open and says that “yet some men say

in many parts of England that King Arthur is not dead… and men

say that he shall come again…”39. As a result of all this we can

say that the physical body of the king is dead which is what

happens naturally at the end of the full spin of the Wheel of

life. His soul however continues to exist and wait its returning

as part of the fulfilment of a prophecy- the glorious king will

return to establish order and rule again.

Jeffrey Morgan sees the two episodes- the death and

departure- as different endings of two stories. One, when Arthur

dies is tragic while the other one leaves hope for his return.

Morgan considers Arthur’s death not as a tragedy but a “tragic

view of life”40 caused by a chaotic universe controlled by

prophecy, chance and emotions. This universe is similar to the

one that Malory lives in and through this observation Morgan

argues Kennedy’s idea that the double ending suggests hope for

39 Le Morte Darthur, XXI. 6, p. 51740 Morgan, J., Malory’s double ending: the duplication Death and Departing in ed. Hanks, D. T., Sir Thomas Malory. Views and Re- views, p. 102

33

better life after death. Kennedy assumes that there is some

structure, horizontal and vertical, but at this point in Morte D’

Arthur all traces of any kind of structures are gone- the

chivalric code and Round Table fellowship have failed and in the

last pages Malory reveals individual struggles and life of chaos:

Guinevere removes herself from the intrigues in the court;

Lancelot fight Gawain, and many knights leave the realm

altogether, finding their place within their home lands or

Jerusalem.

To summarize, we can say that, as St Thomas Aquinas

proposed, Providence provides choice to man and gives him some

control over his earthly life but with a perspective that relates

more to the afterlife and the immortality of man’s soul than his

wealth or wellbeing on earth. Fortuna appears as fickle goddess

spinning her wheel and bestowing or withholding earthly gifts

depending on her own desire. However in Morte D’ Arthur Fortuna is

not simply a bad force. Instead, Malory uses her as a function of

his primary divine forces- Providence and God. His text is too

much concentrated on earthly life- the here and now, for Fortuna

to be removed entirely. Divine forces are channelled and

34

prophecies are used but with the idea that they serve man in his

earthly life, so most of the events in Morte fall under Fortuna’s

control. The Grail Quest is the only time when knights confront

the idea of afterlife and salvation, but that Quest can be

achieved only by Galahad- the most pious and righteous of all.

Otherwise Malory’s knights are more interested in happiness and

worship in their earthly lives. Even when they undertake the

Grail Quest they do so more for earthly fellowship and glory than

for heavenly reward. Mordred’s treason is result of his jealousy

and greed and in no way suggests that he is concerned about his

afterlife. Guinevere shows a late turn towards personal

responsibility, but also become a nun, living in prayer and

fasting with the hope that after her death she will “have a sight

of the blessed face of Christ Jesu, and at Doomsday to sit on His

right side”41. Malory’s interest in Morte D’ Arthur is to present the

struggles of earthly life and by using the idea of a force like

Fortuna he emphasizes human weaknesses and failures. He doesn’t

make her a character but, her influence appears in the background

through events which happen “by fortune” or “by adventure”.

41 Le Morte Darthur, XXI. 9, p. 520

35

Fortuna’s absence as a person leaves space for his characters to

express free will and take responsibility for their actions

because they cannot turn to her or invoke her as characters do in

earlier medieval writings. For example in Chaucer’s Troilus and

Criseyde the author says “But natheles, Fortune it naught ne

wolde/ of oothers hond that eyther degen sholde”42 and Troilus

exclaims: “O cruel Jove, and thou, Fortune adverse”43. They

submit their whole life to the idea of empyreal power that will

have personal interest in their destiny. Malory steer away from

this point of view and although he include the ideas of

controlling deities he insist that every person is provided with

choices and create different characters that presents different

attitudes toward destiny and free will.

IV.4 Divine interventions

Rather than discussing Fortuna, Beverley Kennedy

distinguishes four representations of Divine intervention in

Morte D’ Arthur44- Merlin, trial by battle, the option of Lancelot to

achieve the Holy Grail and the death of King Arthur. To these

42 Chaucer, G., Troilus and Criseyde in The Riverside Chaucer, ed., Benson, L., (Oxford, 1987), V. 1763-4, p. 58343 Ibid. IV. 1192, p. 55344 Kennedy, B., The Idea of providence in Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, pp. 5- 19

36

four elements of Providence listed by Kennedy I want to include

two more: prophecy and prophetic dream. Jane Bliss points out

that this is the structural element of Morte D’ Arthur that creates

the causality of the action45. The narrative is polyphonic, based

on cause- effect situation where nothing is accidental and

everything leads to something. This is the so called “salvation

history” that uses prophecy as a structural element and creates

connection between things separate in time and space. We are

never sure who is in control and what forces drive the world- God

or Fortuna or maybe as Kennedy conclude- a combination of both.

Merlin’s role is to advise the king and protect his immortal soul

but he also makes the most important prophecies in Morte. And to

prevent these prophecies being forgotten, Malory includes

prophetic dreams in the narrative that appear as divine

intervention at the end of the book.

IV.4.1. Merlin- instrument of destiny

Merlin’s image in Morte is derived from the Suite du Merlin

where he is more of a magician and never explains his actions.

Malory enhances his Christian prophetic powers and insists on

45 Bliss, J., Prophecy in the Morte Darthur, p. 1

37

divine knowledge for them. “God and I shall make him speak”46

says Merlin and Uther Pendragon proclaim his heir in his last

breath. After Mordred’s conception Merlin shows not just

knowledge of Arthur’s actions but also that God is displeased

with the King47. Merlin is usually very clear in his predictions-

he makes sure that Arthur understands the consequences of his

actions. Thomas Wright also express the same opinion and conclude

that “Malory portrays Merlin in two important offices: he is the

agent through whom God’s will and “grace” are expressed, and he

is the omniscient strategist who leads Arthur to victory over the

rebel kings”48. At the end of the war with the eleven kings,

Merlin stops Arthur from chasing them after their defeat49.

Kennedy offers two reasons: first, because of the chivalric code

that will be established soon and that calls for fairness and

respect and second, once more, to show divine will. If Arthur

continues pursuing his enemies after their defeat he will step

over the border of protecting his divine approved rights, to

vengeance and as a result “fortune will turn and they shall46 Le Morte Darthur, I. 4, p. 747 Le Morte Darthur, I. 20, p. 2348 Wright, T. L., The Tale of king Arthur: beginning and foreshadowing, in Lumiansky, R. M., Malory’s originality. A critical study of Le Morte Darthur, p. 2349 Le Morte Darthur, I. 17, p. 18

38

increase”50. For once Merlin can’t allow eventual loss in this

battle- Arthur is on the way to establish himself as a British

king and Merlin has to ensure he fulfils his role. On secular

level, sin such as vengeance doesn’t fit with Malory’s image of

Arthur as moral and righteous ruler. On religious level, his soul

will not be saved after his death and the opportunity for Arthur

to return from Avalon will be lost. With the natural, almost

casual way in which Merlin refers to fortune’s ability to change,

complimented with the idea of Arthur’s soul, makes Fortuna in

this example to act as a punisher of sin in the name of God. In

this one scene Malory connects earthly life with afterlife and

presents the picture of Fortuna operating under God’s rule.

About Merlin T. L. Wright says that he “assumes a special

task- that of bringing about the reign of Arthur”51. So when

Merlin arrives at the court of Uther Pendragon his actions are in

no means related to the king’s desires but to the heir he and

Igraine will produce. Morte D’ Arthur starts with the unrequited

love of Uther Pendragon for lady Igraine for which the King

50 Ibid, I. 17, p. 1851 Wright, T. L., “The tale of King Arthur”: beginning and foreshadowing, p. 23

39

initiates war with the duke of Cornwall, her husband. Her

rejection reflects on him very strongly and he fell sick. Merlin

is mentioned by Sir Ulfius as the one who can provide help to

Uther in this moment and “by adventure”52 he finds him. The

adventure is a function of the goddess Fortuna as we saw before

and by inserting this small element in the text Malory ordain

divine intervention to set in motion the path of Arthur’s Wheel.

Not surprisingly Merlin already knows that the king needs his

help. We are never told how he obtains this knowledge and in this

specific interaction he never mentions the name of God so we

can’t say with confidence that his knowledge is divinely

inspired. Although Malory never states that the disguise he made

for Uther, Ulfius and himself is due to magic Merlin’s role is

highlighted by his image of sorcerer corresponding to the general

idea of Uther’s reign in time ruled by chaos, magic and emotions.

The important thing to be observed here is that Merlin made a

bargain, the result of which is Arthur’s begetting. Merlin’s

role is in close connection with Arthur’s destiny and that’s why

he appears to help Uther Pendragon. His agreement with the king

52 Le Morte Darthur, I. 1, p. 4

40

and his demands are known from the beginning and as T. L. Wright

explains Merlin’s contribution to the birth of Arthur and the

prophetic purpose of the bargain are added by Malory53. Combining

this with the fact that prophecy has a tendency to make things

happen and especially in narrative54, Arthur’s conceiving become

almost inevitable. So when Merlin says: “this is my desire: the

first night that ye shall lie by Igraine ye shall get a child on

her…” he does not leave space for chance or accident or any other

option for the future to stay unfulfilled. When he appears in

Uther’s court to claim baby Arthur Merlin makes sure that he is

christened and successfully removes him from the royal court

ensuring that he will not get caught up in the riots after

Uther’s death only few years later. Later on Merlin establishes

the royal lineage when he channels divine powers: “and God and I

shall make him speak”55 and in his last breath Uther points out

his heir: “I give him God’s blessing and mine; and bid him pray

for my soul, and righteously and worshipfully that he claim the

crown, upon forefaiture of my blessing”56. Malory makes explicit53 Wright, T. L., “The tale of King Arthur”: beginning and foreshadowing, p. 2454 Bliss, J., Prophecy in the Morte Darthur, p. 455 Le Morte Darthur, I. 4, p. 756 Ibid.

41

connection between Arthur’s political right to the crown and his

foretold destiny. In his attempt to make his story more realistic

by closing the gap between romance and history Malory brings

together prophecy, fate and politics. Fortuna plays her role by

meeting Sir Ulfius and Merlin setting the basis for destiny to

unfold and to establish the reign of one of the most renowned

Christian kings.

Although Merlin’s character is related to and often perform

his pagan powers as sorcerer Malory insist on stronger connection

with Christianity. He omits many prophecies from his sources,

reduce the use of magic and establish Merlin as instrument for

achieving divine will. He acts in the name of God and he often

does things or orchestrates events on religious feasts and sacred

places which confirm his connection with divine forces. This

trait becomes stronger under the reign of Arthur. He counsels the

Archbishop of Canterbury to assemble all lords and gentlemen in

London by Christmas. With the scene in the church yard where

Arthur pulls out the sword Merlin provides the point from which

Arthur begins to establish his kingship and is especially

symbolic that this happen on religious place. On this day not42

Merlin, but Jesus will provide a miracle: “as He was come to be

king of mankind, for to show some miracle who should be rightwise

king of this realm”57. With this statement Malory assures two

things- the future king is appointed through God’s will and by

comparing him with Christ he will repeat the universal pattern.

Huizinga explains it as a fulfilment of the historical ideal of

life which is the life of Christ and the apostles58. Once more

the life of Arthur is presented in the context of repeated cycle

with no way out. Christ’s life and Fortuna’s Wheel are

allegorical expressions of the inevitability of destiny and

despite all efforts Arthur is unable to change his path.

So Merlin foretold Arthur’s conception and his establishment

as a king, he arrange the scene in the church yard where Arthur

pulls the sword and help him on his way to the throne all this in

attempt to fulfil divine wish and prophesied destiny. Earlier in

my analysis I spoke about his care for Arthur’s immortal soul. He

stops him form chasing after the defeated eleven kings so he will

not cross any Christian virtues. But then Merlin never intervenes

57 Ibid., I. 5, p. 858 Huizinga, J., Men and ideas, p. 83

43

and doesn’t try to prevent Arthur from committing incest

unwittingly. In the forest, after Arthur’s confrontation with Sir

Pellinore Merlin appears to him as a small child and reveals his

lineage: “for king Uther is thy father, and begot thee on

Igraine.”59 Arthur does not believe- he thrust on the obvious

fact that the child is too young and have no way of knowing his

parents or who he is. When Merlin appears as an old man he

confirms his previous words and reveals the second part of the

information: “ye have done a thing late that God is displeased

with you, for ye have lain by your sister, and on her ye have

begotten a child that shall destroy you and all the knights of

your realm.”60 Surprisingly this prophecy is not received with

the needed attention. Malory continues with assuring us and

Arthur that he is the rightful monarch and son of King Uther and

Queen Igraine. The important thing of the prophecy is that Arthur

commits sin and Merlin does nothing to prevent it although he

surely has some divine knowledge of the future. He either chooses

not to prevent it or some other forces intervene. It is possible

that Providence does reveal only near future and Merlin is simply

59 Le Morte Darthur, I. 20, p. 2260 Ibid., I. 20, p. 23

44

unable to interfere or at least to warn Arthur. Or the incest is

another example of misfortune that set the cause- effect

narrative of Malory. At the end of this tale we see how King

Arthur tries to derive destiny from its course in an episode

similar to the biblical scene of Herod who tries to kill baby

Jesus. Malory inserts it in the narrative casually at the very

end of the tale but reveal that Arthur can’t change destiny

despite his best efforts. Both kings act under the influence of

prophecy, but because of the Christian, moral and chivalric

considerations Arthur can’t just slaughter innocent babies. He

finds a compromise that subsequently acts as a loophole for

Fortuna. He put all babies in a ship and “by fortune the ship

drove unto a castle and was all to- riven, and destroyed the most

part save that Mordred was cast up...”61. In this brief quote we

see Fortuna using some of her function to direct Mordred’s

destiny- she guide the ship through the sea and by chance Mordred

is saved. This set a constant undertone of Morte D’ Arthur where the

motion of events is ruled by Fortuna to the anticipated tragic

end. After all Mordred is needed as the figure that will bring

61 Le Morte Darthur, I. 27, p. 31

45

destruction. In Morte D’ Arthur everything has its place and

function and so is Mordred’s treason. Generally scholars see this

as punishment for Arthur’s sin- he commits and act that

displeases God and Mordred is seen as executing divine

punishment. However in the context of cause- effect narrative

Mordred is result of the sin and the final confrontation is a mix

of free will, interpersonal conflicts, divine ordeal and chance.

At the end cruel Fortuna plays her role as an accident misfortune

change the direction of the events. Chance is one of the

functions of the goddess and when an adder struck a knight in his

foot we can assume that this is doing of Fortuna. Ironically such

simple act brings the whole kingdom to its destruction. In this

scene God and Fortuna clash as the two forces who foretold the

end and work together to reach a fulfilment of an earlier

prophecy. By providing Arthur with two opposite dreams

immediately after each other Malory reveals the two spheres of

influence. Fortuna executes her will over the earthly body by her

Wheel and God will save the soul of the king. The two dreams and

the actions of the characters correspond to the double ending and

by inserting the element of chance Malory separates secular and

46

divine influences. In the grand scheme of things he employs the

Boethian idea that God is omniscient, beyond time and controls

every event in a pattern usually invisible to man. Although the

first impression is that God and Fortuna act in conflict, in fact

for XV century author is simply impossible to assume that there

is power stronger than God especially a pagan deity. His focus on

misfortune and chance just reminds how over idealized is the

Arthurian world and how easily influenced is by human actions.

The religious context of the Grail Quest is forgotten and Malory

returns to chaotic system of visions and emotions. In his last

expression of free will Arthur attack Mordred and kill the

traitor but he no longer can prevent the downfall.

Jane Bliss argues that through the biblical echo that we saw

earlier Merlin creates something holy (the chivalric order and

the Round Table fellowship) that Arthur corrupts and God will

punish him. On the other hand Gardner state that Arthur’s mistake

is his firm believes in Fortune and the strong foundation of his

system- it is God’s will after all. But this is more in the

context of Malory’s sources, especially Suite du Merlin. He removes

most of the emphasis on sin and God’s punishment along with most47

of the prophecies and instead uses the salvation and cyclical

view of history to create a narrative with socio- cultural

meaning and moral lesson expressing human nature. In this line of

thoughts, both Bliss and Gardner are right in their arguments-

Arthur as creator of the system and the chivalric code believe

that since it is fulfilment of divine will it is also completely

protected. He neglects personality and free will as part of his

life and that of his knights which are revealed in the Grail

Quest. Undertaking a religious challenge should express their

piety and confirm that the idealized society actually exist on

earth. Instead we see the opposite picture and Malory use it as

an example that man is sinful and traitorous despite what the

official system presents. So the fallout is as much punishment as

it is natural end of the corrupted Arthurian world.

So far Merlin foretold Arthur’s birth and his kingship. We

also established that his role is to lead the young king to his

rightful place that is predestined. Arthur becomes a king “by

adventure and by grace”62 and his marriage to Guinevere is

another way to secure his place in the British throne as a

62 Le Morte Darthur, III. 1, p. 50

48

rightful king on secular level. However on the question of

destiny this is the time when Merlin made the second most famous

prophecy in Morte D’ Arthur. He “warned the King covertly that

Guinevere was not wholesome for him to take to wife, for he

warned him that Lancelot should love her, and she him again”63.

In the text Malory never leaves any indication that their love

will eventually lead to the destruction of the Arthurian kingdom

and the Round Table fellowship. He only claims that Guinevere

will be unfaithful. In matters of his personal life Arthur

appears to be very independent; as we see that he doesn’t take

into consideration this prophecy. He says that his “heart is

set”64 and leave the question outside of the divine

interventions. Same thing is also observed by Jane Bliss, that

God is not mentioned in Merlin’s prediction about Lancelot and

Guinevere and their relationship is a result of free will and

desire supplemented by the fact that prophecy inevitably become

reality in narrative65. At least that is how Arthur and his

knights see things. Love depends on human emotions and can’t be

63 Ibid.64 Ibid.65 Bliss, J. Prophecy in the Morte Darthur, p. 11

49

controlled by Providence or Fortuna and as sir Palomides says to

Tristram “love is free for all men”66. The warning has nothing to

do with the future of his kingdom and Arthur pushed it in the

background. His main concern as a king is stability of the system

that he creates and Guinevere with the Round Table assures that.

He probably believe that he can be good husband and prevent the

adultery but fails to foresee how this can affect him in the

future. When it comes to his kingdom and royal power, he relies

on Merlin’s divine knowledge and advises something that we saw

earlier with Mordred. By prophesying Guinevere’s infidelity

Merlin place the event in reality as something that it will

happen. He also gives the possibility of Arthur to choose other

women for his wife. By giving choice to Lancelot between his love

for the Queen or his religious devotion God provide opportunity

for exercising free will. So adultery is not so much a central

theme but another possibility for the character to choose and

another way for destiny to be fulfilled.

After the main prophecies are made Malory removes Merlin

from the narrative. He presents the tragedy in his life when as a

66Le Morte Darthur, X. 86, p. 277

50

prophet and magician he has inclination not only on Arthur’s

destiny but also on his own future. Merlin is aware that Dame

Nenive will bring him to his death but he also teaches her every

magic that he knows. With his death the main prophetic figure,

the instrument of executing divine will is removed from the

narrative. Malory introduces a pleiad of women who reveal future

and perform magic, like the Lady of the Lake and dame Brusen. In

terms of destiny, Providence ceases the active influence when the

wheel of life is set in motion and Arthur fall into the path of

his fate. The magical and otherworldly powers disintegrate in the

hands of many women that are closer to the pagan goddess and are

just as deceitful as she is. The important thing is that Merlin

can’t prevent his fate from happening and thus with his own death

he once more proves that destiny can’t be adverted.

IV.4.2. Arthur’s prophetic dreams

Medieval dream theory distinguishes five kinds of dreams,

systemized by Macrobius and Aristotle. The first two categories

insomnium and visum are false and so do not fall within Malory’s

interest. They don’t provide any revelation or knowledge and

Malory wants to send a message through every element of his text51

so he uses dreams from the three categories that do provide this.

Somnium is a revelation given by otherworldly authoritative

figure. Visio is revelation through vision and oraculum is also a

true dream but coached in fiction. They all send a true message

and Arthur’s dreams are always in one of these three categories.

Goyne explains that this categorization of dreams was popular in

the fifteenth century and Malory consciously applied it in Morte

D’ Arthur67. For this dissertation the important element is that

Malory was able to use specific kinds of dream, vision and

prophecy as way of giving true forecasts of the future. This

means that the characters who receive knowledge through such

dreams or prophecies can exercise a certain level of free will in

choosing how to react to them, but they do not have full control

as what they are told remains up to God, who provides the

options. Malory’s knights are also dealing with the expectations

of the chivalric code as summed up in the Pentecostal Oath, which

tells them how they should behave and also assumes that a good

knight is a worthy man. The combination of all these elements

67 Goyne, J., Arthurian dreams and Medieval dream theory, Medieval perspectives, vol. 12, 1997, pp. 79- 80

52

results in the popular perspective on what human life is that is

reflected in Malory’s Morte as I will go on to show.

The dream that follows the act of incest is purely

symbolical and Malory never explains its meaning. Just because it

happens in this specific moment I am willing to suggest that it

prophecies Mordred’s future role in Morte. Arthur “thought there

was come into his land griffins and serpents, and he thought they

burnt and slew all the people in the land; and then he though he

fought with them and they did him great harm and wounded him full

sore, but at the last he slew them.”68 The first part presents

the Civil War started with the treason and the subsequent battle

that he fought with Mordred. The ending however differentiates

from what actually occurs in Morte. Malory suggests the

possibility that Arthur may keep his place on the British throne

by successfully defeating his enemy. Same thing is expressed much

later when Gareth appears in another dream to propose way out of

the fallout. These dreams however are in the context of divine

revelation and can be related to the double ending. They present

not an outcome that will occur in Arthur’s earthly life but refer

68 Le Morte Darthur, I. 19, p. 21

53

to his soul and the afterlife complimenting the prophecy for his

return. The sin that the king commits will be punished but his

soul will sail way to Avalon because after all Arthur is one of

the best Christian kings. His punishment is revealed by another

dream: “he sat upon a chaflet in a chair. And the chair was fast

to a wheel, and thereupon set King Arthur in the richest cloth of

gold that be made. And the king thought there was under him, far

from him, a hideous deep black water, and therein was all manner

of serpents and worms and wild beast, foul and horrible, and he

fell among the serpents and every beast took him by a limb”69.

This dream provides Arthur with vision on his future. Fortuna

will spin her Wheel and the king will fall, alone and

dishonoured.

The source for this dream is the French Le Mort de Roi Artu,

part of the Vulgate cycle but Malory describes just the basic

elements of it. In his source Fortuna holds an interrogation by

asking Arthur specific questions about his actions and deed. She

explicitly made the point that his fall of the Wheel is

punishment for that and thus stress on the idea of divine

69 Ibid, XXI 3, p. 510

54

judgment. Alison Stone points out that this is the only image of

Arthur and Fortuna in the whole illustrative tradition of the

Lancelot- Grail tradition70. Usually we can see depictions of

significant moments of the story like Arthur drawing the sword

out of the stone or the adulterous relationship between Lancelot

and Guinevere. By illustrating this moment from the story the

author of Le Mort De Roi Artu inevitably draws the attention to it

suggesting that Fortuna holds significant importance for the

story. She acts as executor of divine will and judgment under the

superiority of God.

IV.4.3. Trial by battle

One other kind of divine intervention is probably more

obvious. Trial by battle is one of the systems of judicial

process in the Arthurian world of Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur and the

only one that suggests the direct operation of divine will. Trial

by battle expresses the idea that God will stand on the side of

the righteous and will give him strength to win the battle. For

example the young and inexperienced Gareth successfully defeats

70 Stone, A., Illustration and the fortunes of Arthur, in Lacy, N., The Fortunes of King Arthur (Cambridge, 2005), p. 118

55

the Red Knight who we know “hath seven men’s strength”71. But in

spite of such examples, Beverly Kennedy concludes that King

Arthur usually does not accept trial by battle as a righteous and

final verdict72. It is also true that Arthur never fights a

battle when the odds are not on his side and never allows combat

between unequal opponents. There is one exception: his early

battle with Sir Accolon. Arthur is imprisoned by Sir Damas

through the magic of Morgan le Fay. We are told that Damas is a

false knight and a coward who fights his brother, Sir Outlake,

for their lands. Damas does not have the right to the lands and

uses other knights to fight instead of him under the threat of

death by starvation in prison. Malory poses a dilemma to Arthur-

he can refuse the battle since it is morally wrong which would go

against the Pentecost Oath and also meant that by the rules of

trial by battle he should lose. But then he will die shamefully

imprisoned. Malory makes it possible for Arthur to undertake the

battle by giving him the motive of saving other knight and

putting stop to the cruel practice of Sir Damas. As a result

71 Ibid, VII 2, p. 12372 Kennedy, B., Adultery in Morte D’ Arthur, Arthuriana, vol. 7, No 4, winter 1997, pp. 63- 91

56

Arthur assumes his rightful role as protector and judge and so

the outcome of the battle must be for him to win. Kennedy points

out that this scene is largely invented by Malory and also adds

that Arthur never abandons his faith in God’s grace. There is a

complication in that- the king is under the impression that he

fights with Excalibur and the scabbard given to him by the lady

of the Lake. They posses magical powers and while he uses them in

battle he “shall lose no blood”73. Using magical armour is not

permitted by the knightly code but on the other hand this battle

is not the conventional trial of right and wrong. Malory

justifies Arthur’s participation on the wrong side through his

desire to bring justice but also assures his victory through the

use of magical sword and scabbard.

This episode reveals that King Arthur prefers not to put his

trust only in God for such ordeals. He carefully follows Merlin’s

advice and uses his magical sword and scabbard to ensure victory.

Malory constructs Arthur in terms closer to an actual political

figure than the one of myth- his Arthur is more rational and

practical than ideal.

73 Le Morte Darthur, I. 25, p. 30

57

IV.4.4. Lancelot

In contrast Kennedy points out that Lancelot is the knight

who has ultimate belief in the divine ordeal of trial by battle.

He agrees to fight Mordred and to prove his and Guinevere’s

innocence of the accusation of adultery. Arthur refuses because

he knows that, just like him, most of the Round Table fellowship

will explain Lancelot’s inevitable victory in rational terms-

Lancelot’s superior strength. As we said before Arthur can’t

accept an unequal ordeal, so he is left with one option to

resolve the final conflict- to refer the case to the courts of

law. When Lancelot disrupts this by rescuing Guinevere, Arthur is

forced into war against Lancelot and the siege of Joyous Gard

becomes a form of royal trial by battle.

Just like the transition from belief that external powers

control human life to taking responsibility for personal choices

and action that we saw happen to Guinevere, Malory makes the same

transition with the judicial process. At the beginning of Morte D’

Arthur he relies more on divine ordeal, embodied by Lancelot-