The architectural patronage of Miklós Bethlen in late seventeenth-century Transylvania

Ming Imperial Patronage of the Wudang Mountains and the Daoist God Zhenwu

Transcript of Ming Imperial Patronage of the Wudang Mountains and the Daoist God Zhenwu

Foreword 6Steven High

Foreword 7Fang Qin

Acknowledgments 8

Introduction 11Fan Jeremy Zhang

Gold and Jade: The Material World of the Early Ming Princes 18David Ake Sensabaugh

Architecture during the Reign of the Yongle Emperor 27Tracy Miller

Recent Archaeological Finds from Princely Tombs in Hubei 34Fan Jeremy Zhang

Tibeto-Chinese Buddhist Art in the Ming

43Rob Linrothe

Ming Imperial Patronage of the Wudang Mountains and the Daoist God Zhenwu 49Noelle Giuffrida

Royal Taste and Ming Painting 55Lennert Gesterkamp

Chinese Ceramics from Ming Dynasty Princely Tombs in Hubei 62Laurie Erin Barnes

Catalogue

Gold and Silver 70

Jewelry and Jade 88

Buddhist Works 133

Daoist Works 144

Paintings 168

Porcelain 180

Clothing and Others 197

Bibliography 212

Maps 216

Chronological Table of Ming Emperors 219

Glossary and Index 220

Index 221

contents

49

Ming Imperial Patronage of the Wudang Mountains and the Daoist God Zhenwu

noeLLe Giuffrida

Imperial devotion to and patronage of Daoist gods, rituals, and institutions flourished during the Ming dynasty. Emperors, empresses, and eunuchs in Beijing, as well as princes enfeoffed in territories throughout the country, sponsored Daoist activities, many of which involved commissioning works of art. Emperors ordered the compilation and printing of new editions of the Daoist canon featuring woodblock-printed illustrations. They commis-sioned the performance of Daoist rituals, many on a grand scale, at court and at sacred sites throughout the country, sending court officials and eunuchs as emissaries. Imperial largesse also extended to new temple-building projects and renovations to existing sites with freshly commissioned statues, paintings, and a wide variety of ritual paraphernalia such as vestments, banners, tablets, scriptures, incense burners, bowls, vases, candlesticks, and bells. Many of the Daoist statues included in this volume can be linked to Ming imperial patronage of the Wudang Mountain range in Hubei province, home to the Daoist god Zhenwu (the Perfected Warrior). This essay outlines some of the historical contexts and material evidence of royal support for the god and temples on Wudang. Because the Daoist pantheon remains, for the most part, understudied and often misidentified, statue sets are reconstructed and the identifying characteristics of a selection of Daoist figures are highlighted.

the yonGLe emperor’s patronaGe of daoism and Zhenwu

Zhu Di (1360–1424), the Yongle emperor, stands out as one of the most significant imperial patrons of Daoism during the

Ming dynasty. His involvement began during his early years as the Prince of Yan in Beijing.1 Under the guidance of his advisor Yao Guangxiao (1335–1418), also known by his monastic name Daoyan, Zhu Di decided to attack the armies of his newly installed nephew and usurp the throne for himself. As he prepared to advance with his soldiers, Zhu Di reputedly had a vision of an armored deity with long, loose hair who was surrounded by banners. After Yao identified the figure as Zhenwu, the future emperor loosened his own hair and took up his sword, thereby leading his forces to eventual victory.2 Zhu Di and his advisors thus asserted that the god had sanctioned his ascension. Shortly afterward, he ordered the compilation of a new Daoist canon in 1406, supervised by members of the Zhengyi (Orthodox Unity) school, including the 43rd Celestial Master Zhang Yuqu (1361–1410) and the 44th Celestial Master Zhang Yuqing (1364–1427).2 Concerned with bolstering his legitimacy as emperor, Zhu Di ordered the building of numerous temples dedicated to the god, including the Temple of the Perfected Warrior (Zhenwu miao) in Beijing, the Hall of Imperial Peace (Qin’an dian) in the Forbidden City, and a massive complex of temples on Zhenwu’s reputed home, Wudangshan, from 1412 to 1424.4 He also renamed the range Mountain of Supreme Har-mony (Taiheshan), designating it the most important sacred site in the country.

Zhenwu’s history extends back to the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) when the god was known as Xuanwu (Dark Warrior) and represented as a tortoise entwined with a snake.

50 Giuffrida

Emerging as an anthropomorphic martial deity associated with the north around the tenth century, the entwined animals eventually transformed into the god’s vanguard (cat. 80). Zhenwu, also known as Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heaven (Xuantian shangdi), appears with long, unbound hair flowing down his back and bare feet that refer to his forty-two-year period of meditation and cultivation in the Wudang Mountains. He wears armor under his black robe, suggesting his essentially martial nature, confirming his rank and power as a military commander, and signifying his regality as an emperor on high. Zhenwu served as protector of the country and its people, grantor of legitimacy to rulers, vanquisher of demons and converter of malevolent forces, and bestower of a variety of worldly benefits to individuals at all levels of society. Though Zhenwu received considerable imperial patronage during the Northern and Southern Song periods (960–1279) as well as in the Tangut Xia (1038–1227) and Mongol Yuan (1271–1368) eras, royal support for the god reached its zenith during the Ming.

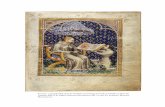

The Yongle emperor commissioned the production of Records and Pictures of Auspicious Responses by the Emperor of the Dark Heaven in the Great Ming (Da Ming Xuantian shangdi ruiying tulu), an illustrated book preserved in the Daoist canon. It visually and textually documents seventeen miraculous episodes reported during a key phase of the projects at Wudangshan in the early fifteenth century—all of which were considered to be evidence of Zhenwu’s approval of these endeavors.5 Several entries depict marvelous horticultural signs, while others reveal huge beams of wood and metal bells magically floating in the water for easy retrieval.6 Others represent occasions when the god materialized anthro pomorphically, each accompanied by a specific date and time. For instance, on August 17, 1413, Zhenwu descended on his black cloud and appeared above the Palace of the Jade Void of the Dark Heaven (Xuantian yuxu gong) with two attendants (fig. 6-1). One carried Zhenwu’s seven-star sword of the three terraces (san tai qixing jian) while another bore the god’s flag, which featured the seven stars of the Northern Dipper asterism (Beidou).

commissioninG rituaLs and sendinG statues to wudanGshan

Zhu Di’s restoration and building of temple complexes at Wudangshan prompted the creation of numerous statues and objects for veneration, for the performance of Daoist rituals, and for the adornment of sacred spaces. Highly skilled artisans from

the capital crafted these items using sumptuous materials such as red lacquer, jade, silk, bronze, silver, and gold. Sets of ritual utensils usually included an incense burner (cat. 77), bottles, candle stands, silk lamp covers, incense boxes, and other tools. The court also sent lavish donations of bells, stone chimes, dragon tablets (longpai), multiple copies of Daoist scriptures, incense, and candles. In addition to the Palace of the Jade Void mentioned earlier, three other complexes received significant imperial largesse in the early fifteenth century: the Palace of the Purple Empyrean (Zixiao gong), the Palace of the Southern Precipice (Nanyan gong), and the Palace of the Five Dragons (Wulong gong). Under Zhu Di, the Marquis of Longping Zhang Xin, Vice Minister Guo Jin, and the emperor’s son-in-law Mu Xin led more than two hundred thousand artisans and soldiers who remained at Wudangshan for the duration of the project. Zhang Yuqing selected more than six hundred Daoist clerics who arrived on the mountain to staff the temples and perform periodic rituals.

In 1416, Zhu Di commissioned one of the largest surviving Ming statues of Zhenwu for the Golden Hall (Jindian) at the Palace of Supreme Harmony (Taihe gong) located on the range’s highest peak (fig. 3-9). This finely crafted, five-ton bronze exemplifies many iconographic and stylistic characteristics common to other Ming statues of the god, suggesting that it may have served as a

Fig. 6-1. Zhenwu Appears above the Palace of the Jade Void, Da Ming xuantian

shangdi ruiying tulu 大明玄天上帝瑞應圖錄 (DZ 959), 1444–45. Bibliothèque

nationale de France, Chinois 9548 (952)

51

model for other fifteenth-century images. The broad-shouldered, beefy-armed god sits with legs pendant and bare feet set fairly wide apart. His long hair is slicked back close to his head before descending down his back. His long beard extends straight down to his chest, upon which armor is revealed from underneath a robe gathered above his waist by a medallion-decorated belt. This imperially commissioned statue, its attendants, and the Golden Hall itself displaced a fourteenth-century bronze hall, effectively reclaiming Wudangshan for Zhu Di from its former Mongol Yuan imperial patrons.

Ming editions of gazetteers, veritable records, and books within and beyond the Daoist canon contain detailed descrip-tions of imperially commissioned rituals, statues, and other materials for Wudangshan’s temples by the Yongle emperor and later Ming rulers.7 Many sponsored Purgation Rites of the Golden Register (Jinlu zhai) at Wudangshan to solicit blessings, male heirs, and longevity for the emperor and his family.8 In all, at least eight Ming emperors sent statues, ritual paraphernalia, and other materials on at least twenty-seven different occasions. They included Zheng tong (r. 1436–49) Chenghua (r. 1465–87), Hong-zhi (r. 1488–1505), Zhengde (r. 1506–21), Jiajing (r. 1522–66), and Wanli (r. 1572–1620).9 By the middle of the fifteenth century, eunuchs were charged with organizing and supervising donations and projects. Imperial edicts indicate that objects and craftsmen from the imperial court made the three-month journey to Wudangshan. A typical trip would involve dozens of yellow imperial boats and more than eighty artisans traveling to Hubei. Artists carved platforms for statues on site from imported Henan jade, and this process, along with the installation of statues, often lasted more than two months. Wang Zuo, Grand Eunuch of the Interior Court (neigong taijian), served in the court of Jiajing. He worked at Wudangshan from 1539 to 1557, supervising many aspects of imperially commissioned projects from architectural renovations to the installation of new statues.10 As a prince, Zhu Houcong, the Jiajing emperor, had lived in Huguang near Wudangshan with his father, Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519), Prince Xian of Xing, who was a Zhenwu devotee and annual visitor to the mountain. Zhu Houcong’s refusal to honor the previous Hongzhi emperor, as prescribed by ritual codes, prompted the Great Rites Controversy that concluded with the Jiajing emperor posthumously elevating his own parents. Thus the series of renovation projects at Wudangshan sponsored by Zhu Houcong beginning in the second year of his reign and continuing for more than thirty years, stemmed not only from the emperor’s

Daoist beliefs and the need for Zhenwu’s protection and support, but also as an act of his loyalty to his father. For example, in 1552, Jiajing commissioned a huge memorial arch (pailou) at the foot of the Wudang range proclaiming Dark Peak that Governs the World (zhishi xuanyue) (fig. 6-2).

Because several Ming emperors commissioned sets of statues for Wudangshan, temples accumulated multiple sets of images. A typical grouping included a seated Zhenwu (cat. 79) accompanied by an entwined turtle and snake (referred to as shuihuo yizuo) thus connoting connections with Daoist neidan (inner alchemy). Four additional attendants, a numinous official (lingguan) or jade lad (jintong), jade maiden (yunü) (cat. 81), flag holder (zhiqi), and sword holder (pengjian) completed the core of Zhenwu’s retinue. On several occasions, the god’s entourage expanded to include a group of four, ten, or twelve celestial lords (tianjun) and celestial marshals (yuanshuai) as his assistants, reinforcing his connection with the Daoist Thunder Department (leibu).11 These specific combinations of statues echo standard groupings found in fifteenth-century texts on thunder rites, including the Golden Book of Perfect Salvation of the Numinous Treasure of Highest Purity (Shangqing lingbao jidu dacheng jinshu).12 For instance, in 1494, a set of statues installed in the Palace of the Southern Precipice incorporated twelve marshals from three groups: Deng, Xin, Zhang, and Tao, the Four Great Celestial Lords of the Thunder-clap; Gou, Bi, Pang, and Liu, the Four Great Celestial Lords of the Thunder Gate; and Ma, Zhao, Wen, and Guan, the Four Great Celestial Marshals of Upper Purity.13 Sur viving Ming woodblock-printed ritual manuals, illustrated scriptures, and compendia help us to decode the iconography of these celestial lords and marshals such as Gou, who has a third eye and wields a hammer and spike (fig. 6-3 and cat. 82).14

Wudangshan attracted pilgrims from all over the country during the Ming dynasty. Devotees who journeyed there followed pilgrimage routes that highlighted sites linked to episodes from Zhenwu’s hagiography. While most surviving visual narratives of the god take the form of murals, hanging scrolls, painted albums, or illustrated books, we can also identify a few narrative sculptures. In one such work (fig. 6-4a), Zhenwu sits astride an entwined turtle and snake wielding a sword, only the hilt of which remains in his right hand. The temple behind him represents the Yongle-era Golden Hall. Five robed, dragon-faced figures are positioned at the bottom (fig. 6-4b). Supported by individual clouds, each figure gazes reverently up at the god while wearing a Daoist cap and holding up a hu, a type of object

52 Giuffrida

Fig. 6-2. Stone memorial arch at the foot of Wudangshan, 1552. H. 39 ft. 4 in. (12 m)

Fig. 6-3. Celestial Marshal Gou of the Thunder Gate (Leimen gou yuanshuai 雷門苟元帥), Precious Scripture of the Jade Pivot

(Yushu jing 玉樞經), 15th–16th century. Accordion-folded, woodblock-printed book, 13 x 5 in. (33.2 x 12.5 cm) each page. The

British Library, ORB 99/161

held by subservient officials before the emperor. The five longjun (dragon lords) can be connected to an episode from Ming-period hagiographies of Zhenwu. According to the Chronicle of Sacred Revelations of the Emperor on High of the Dark Heaven (Xuantian shangdi qisheng lingyi lu), five dragon lords escorted Zhenwu during his apotheosis, when he ascended from Wudangshan to the court of the Jade Emperor.15 Although there are many individual and groups of dragon deities, either dragon deities (longshen) or dragon kings (longwang), within Daoist, Buddhist, and local pantheons, the survival of dragon lord statues at Wudangshan (cat. 84) suggests that sculptural assem-blages representing this story may have also existed.

Buddho-daoist hyBrids

Statues representing additional deities also appeared in temples on Wudangshan during the Ming. Images of Taiyi Jiuku tianzun (Celestial Worthy of the Great Unity, Savior from Suffering)

(cat. 86) and Doumu (Primordial Goddess, Mother of the Dipper) (cat. 85) demonstrate continuing hybridity and borrow-ing between Daoist and Buddhist traditions. In many ways, Jiuku tianzun represents a Daoist version of the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion, Guanyin.16 Both possess the ability to perform miracles, transform into multiple forms, and respond to appeals from people from all walks of life. Jiuku tianzun also adopts a few elements of Guanyin’s iconography such as the healing willow branch and hou lion vehicle.17 In painting, he wears a blue robe and often holds a willow branch in his right hand and a bowl of elixir in his left (fig. 6-5). However, his moustache, beard, Daoist crown with suspended jewel, as well as the nine-headed lion mount assert his identity as a male Daoist deity, compared with the androgynous or motherly Guanyin. Sculptural forms of Jiuku tianzun sometimes incorporate additional Daoist visual markers like the three-legged curved armrest associated with images of Lord Lao as one of the Three Pure Ones (Sanqing), Daode tianzun (Celestial Worthy of the

53

Fig. 6-4a. Zhenwu Ascending from Wudang to the

Celestial Court, 15th or 16th century. Bronze, H. 47/ in.

(121 cm). The British Museum, BM OA 1990.12-15.1

Fig. 6-4b. Detail of dragon lords Fig. 6-5. Celestial Worthy of the Great Unity, Savior from Suffering (Taiyi Jiuku

tianzun 太乙救苦天尊), late Ming or early Qing dynasty. Hanging scroll, ink

and colors on paper. The Baiyun Abbey, Beijing

Way and Its Power). Beliefs about Jiku tianzun also shared territory with the salvific powers of the bodhisattva Dizang who could rescue one’s deceased relatives from regions of hell. Thus many images of Jiku tianzun served in mortuary contexts. Similarly, the Daoist goddess Doumu yuanjun shares several iconographic features with the Buddhist goddess of dawn, Marīcī. The sow or boar serves as a vehicle for both deities, either as a single animal or a group of seven pulling a chariot with the goddess inside (fig. 6-6). Doumu’s identity as a Daoist goddess comes from her role as the mother of the stars of the Northern Dipper asterism, which is sometimes represented by seven sows.

54 Giuffrida

and temples on Wudangshan—balances our picture of imperial patronage of religious art during the period. The statues, steles, and ritual implements preserved in Hubei province included in this volume evince the vibrancy and variety of Daoist visual culture throughout the Ming dynasty.

notes

1. As the Prince of Yan, he added to and restored halls at Changchun gong (Palace of Perpetual Spring) now known as Baiyun guan (White Cloud Abbey). See Wang, Ming Prince and Daoism, 91, 93, 251.2. Shin-yi Chao, Daoist Ritual, State Religion and Popular Practices, 97.3. The new canon was presented at court in 1422, but the task of carrying out the printing, completed in 1445, took place under the Zhengtong emperor.4. The Qin’an dian, initially established in 1420, is located behind the rear garden of Kunning palace (the empress’ palace), inside the Xuanwu gate.5. DZ 959. The episodes correspond to the start and completion of construction on the great roof of the main hall of the Palace of the Jade Void.6. Qianlin or langmei (betel nut plum) trees reputedly first bloomed and fruited once Zhenwu had achieved the Dao. Blossoms and fruit supposedly appeared in abundance during the spring of 1413. The beam and bell were reputedly incorporated into Yongle-reign halls.7. For an extensive survey of Ming imperial patronage of Wudangshan, see deBruyn, “Le Wudang shan”; and Yang Lizhi, “Mingdi chongfeng zhenwu,” 73–109.8. For an overview of texts on the Golden Register rite, see Schipper, Taoist Canon, 995, 998–1000, and 1006–08. Yongle commissioned a rite at the end of the major work at Wudangshan, but it ended up being performed one day after his death in 1424. 9. Major sources for records of imperial patronage of the mountain include Ren Ziyuan, Chijian dayue Taihe shan zhi (1431 edition). 10. Wang Zuo, Dayue Taihe shan zhi (1556). 11. Several Daoist traditions, including Tianxin (Celestial Heart), Qingwei (Pure Tenuity), and Shenxiao (Divine Empyrean), created complex systems of divine bureaucracy and codified elaborate exorcistic thunder rites in liturgical manuals beginning in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.12. ZWDS 698, compiled by Zhou Side (1359–1451), a prominent Daoist priest at the courts of the early Ming. Chapter thirty-five lists several cadres of thunder deities within the instructions for a Zhenwu jiao (offering ritual). For more on thunder rituals in the Ming, see Meulenbeld, “Civilized Demons,” 244–50.13. Ren Ziyuan, Chijian dayue Taiheshan zhi (1431), juan 2.14. Another celestial lord, Deng Tianjun, also typically wields a mallet and spike, but Deng has avian features.15. A similarly sized bronze sculpture, dated by inscription to 1616, featuring the five dragon lords at its base, is in the collection of the Wudang Museum.16. For a discussion of Jiku tianzun in medieval Chinese texts, see Mollier, “Guanyin in a Taoist Guise,” 177–208.17. For example, see Guanyin Bestowing a Son, hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, late 16th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.152.

In her multiple armed form, she holds a sun and moon, the latter of which relates to her ability to dispense the beneficial elixir crafted in the lunar environment by a hare.

Though the Yongle emperor’s dedication to Tibetan Bud-dhism and Tibeto-Nepalese style, mercury-gilded bronze statues crafted in imperial workshops during the era are often men-tioned, this brief exploration that spotlights his significant support for Daoist institutions and art, continued by subsequent Ming rulers and their families—particularly in honor of Zhenwu

Fig. 6-6. Primordial Goddess, Mother of the Dipper (Doumu Yuanjun

斗姆元君), late Ming or early Qing dynasty. Hanging scroll, ink and

colors on paper. The Baiyun Abbey, Beijing