The architectural patronage of Miklós Bethlen in late seventeenth-century Transylvania

Art, Artists & Patronage: Qawwali in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Transcript of Art, Artists & Patronage: Qawwali in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Widely considered to be the birthplace of khānaqāhī qawwālī (qawwālī performed in a Sufi shrine) as an

accepted medium for zikr (remembrance of Allah) within the Chishti silsilā (Sufi order), Hazrat Nizamuddin

Basti is home to a vibrant tradition even today. The khānaqāhī qawwāl (a performer of mystical songs

associated with a Sufi shrine) associated with Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya continue to draw inspiration

from the rauzā (sacred tomb) of the saint and his celebrated disciple Amir Khusrau, who is widely

acknowledged to be the progenitor of khānaqāhī qawwālī. In the spirit of collaborative fieldwork, this paper

puts forth and analyzes the traditional system of art-artist-patronage from both points of view – the

sajjādānashīn (successors of a Sufi saint) and pīrzādagān (children of a spiritual leader) as custodians of the

dargāh (Sufi shrine built around the tomb of a saint) and the qawwāl as ritual performers, both tied together

in the same space through their commitment to spiritual duty. Beginning with contextualizing the practice of

khānaqāhī qawwālī in history, the paper moves to a detailed analysis of the practice in Hazrat Nizamuddin

Basti in Delhi based primarily on oral history sources. It looks at the decorum and order of events in a khānaqāhī

qawwālī session before ending with a look at the domain of filmī qawwālī (a dramatized style of qawwālī

derived from Indian films) and the emergent techno qawwālī as examples of genre diversification reflecting

the delicate balance between the dargāh and the market forces.

The emergence of a mystical and spiritual path in Islam within a couple of centuries after Prophet Mohammed

presents us with an interesting and vibrant tradition called Sufism. The innate notion of Sufism is the notion of

a covenant between God and humankind, such that He has ‘friends’ whom He loves very much. In today’s

Sufi parlance, these are the Allahwāle, a term which attempts to convey the idea of them being the ones

who are friends of God, and are thus close to Him.

123

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 123

For Kenneth Avery: “The very word sūfī, if derived from the Arabic word for wool (sūf), reflects the wearing of

ascetic woollen garments characteristic of eastern Christian monks.”1 A number of charismatic individuals

appeared on the landscape of Islam, who came to be revered as spiritual masters. No formal orders or

brotherhoods existed back then, and thus, the relations between the pīr (Sufi guide) and the murīd (disciple

of a Sufi guide) were of utmost importance, even though they were informal. Some of the early Sufis were

Abu Yazid al-Bistami (d. 874), Junayd (d. 910), Mansur al-Hallaj (executed in 922) and Abu Bakr al-Shibli (d. 946).

Written sources reveal that by the 10th century, techniques and rituals were in the process of being developed

for the generation of altered state of experiences, both individually as well as in a social setting. For much of

mainstream Islam, all such practices were frowned upon, and seen as unnecessary ‘innovations’ (and perhaps

even deviations) from the path clearly laid down by Prophet Mohammed. One of the major techniques used

to induce and sustain these altered state of experiences was that of aural stimulation – recitations from The

Holy Qur’ān, chanting, listening to poetry and music. This practice came to be known as samā’ (spiritual

concert), and is basically an extension of the practice of zikr. Jean During explains the notion of samā’ in the

following way:

“Samā’, which literally means ‘audition’, denotes in the Sufi tradition, spiritual listening, and more

particularly listening to music with the aim of reaching a state of grace or ecstasy, or more simply

with the aim of meditating, of plunging into oneself, or as the Sufis say, to ‘nourish the soul’. It thus

operates in a mystical concert, of spiritual listening to music and songs, in a more or less ritualised

form.”2

Chishti Sufism and Khānaqāhī Qawwālī

Among the multiple forms of samā’, the Indian subcontinent witnessed the birth of khānaqāhī qawwālī. As

the name suggests, it sprung from the shrines and the oral history narratives of Sufis and qawwāl suggest the

shrine of Hazrat Sheikh Khwaja Syed Muhammad Mu’inuddin Chishti ‘Gharib Nawaz’ (1141-1230) in Ajmer as

the birthplace of khānaqāhī qawwālī. The story goes that he noticed the use of music as a means in worship

among the various communities of Hindustan upon his arrival. This made him think that the use of music as a

form of samā’ might be a useful strategy to make the message of Chishti silsilā more accessible. There are

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

Aga Khan Trust for Culture124

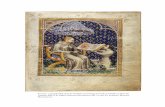

Page 122:Sufis dancing rapturously

Folio 62A from the Diwan of

Amir Hasan Dihlawi

Attributed to ‘Abd al-Salim

Courtesy: The Walters Art

Museum, Baltimore

Right:The Dargah at Nizamuddin

19th century, Opaque water

colour on paper, S1986.531

Reproduced by kind permission

of the Smithsonian Unrestricted

Trust Funds, Smithsonian

Collections Acquisition Program

and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler

Gallery, Washington DC

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 124

wide-ranging differences as far as opinions about the form of samā’ at the time, but most Sufis and qawwāl

are in unison that the daf (a kind of tambourine) was the only musical instrument which was used. Most

accounts say that the poetry recited was Persian kalām (poems) in tarz (musical tune) which were the

beginnings of a unique synthesis of Persian maqām (system of melodic arrangements) and Hindustani rāgas

(structured patterns of melodic notes).

However, in terms of granting structural coherence to the genre, Amir Khusrau (1253-1325) is widely believed

to be the progenitor of khānaqāhī qawwālī. He is said to have rounded up a group of twelve boys who came

to be called the Qawwāl Bachche.3 He trained them in the art of khānaqāhī qawwālī and taught them the

fundamentals of music, poetry and the adab-ādāb (codes of decorum and obedience) of being amidst

Sufis. Samad bin Ibrahim was the eldest in that group, and his unbroken lineage is claimed by some qawwāl

to join with Ustad Tanras Khan, court musician of Bahadur Shah Zafar (reign: 1837-57), the last Mughal emperor

of Dehli. The senior-most qawwāl in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti today, Me’raj Ahmed Nizami claims that he is a

fourth generation descendant of Ustad Tanras Khan, and is thus, the khalīfā (head of an artistic lineage) of

the Qawwāl Bachche gharānā (artistic lineage), a claim disputed by more than a few qawwāl as well as

some classical musicians. Quite a few other members of the qawwāl birādarī (group or community) in Hazrat

Nizamuddin Basti are related through a complex pattern of kinship, which can form the subject matter of a

paper by itself.

In terms of the ethos and the worldview with which khānaqāhī qawwālī is inextricably connected, I find it

useful to take recourse to the following couplet:

Har qaum rāst rāhe dīn-e wa qiblagāhe

ma qibla rāst kardim samt-e kajkulāhe4

All people have their paths and focus of worship,

I focus my worship on the tilted cap of my beloved.5

The lines above are iconic because they depict the symbolism underlying the samā’ experience. The first line

is said to have been uttered by Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya (1238-1325) when he saw a group of people offering

prayers at the bank of river Yamuna. Amir Khusrau, his favourite disciple, who was standing next to him, is said

127

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi

Left: Image of Pīr Khwaja GhulamMuinuddin Nizami, thegrandfather of Pīr KhwajaAhmed Nizami Syed Bokhari,the current sajjādānashīn andmutawallī, Dargāh HazratNizamuddin Auliya. (Courtesy:Pīrzādā Syed Farid Nizami)

,

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 127

to have responded with the second line thus expressing the essence of tasawwuf (Sufism or Islamic mysticism),

the philosophy of nisbat (association with a Sufi figure or lineage) – creating a relationship with one’s pīr and,

through him, with the shajarā (genealogical tree) of the order going up to Hazrat Ali, Prophet Mohammed

and, ultimately, Allah.

Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari narrates an interesting story, which strengthens the point made above,

using the example of the popular Persian kalām of Amir Khusrau given below, and rendered in the compilation

by Ghaus Muhammad Nasir Niazi Qawwal:

Namidānam che manzil būd shab jāye ke man būdam

ba-har sū raqs-e-bismil būd shab jāye ke man būdam

I do not know what house it was the place I was last night,

doomed birds were in a flurried dance the place I was last night.6

Once, Amir Khusrau had gone to Panipat to meet Sheikh Sharafuddin Bu Ali Shah Qalandar, who told him

about his nightly parvāz (spiritual flight) to the skies. In his discourse, he is said to have said something that

hurt Khusrau. Bu Ali Shah said that he sees lots of mashāikh (Sufi guides) in his parvāz but never sees Hazrat

Nizamuddin Auliya. Khusrau returned to Dehli and narrated the incident to his pīr who smiled and asked

Khusrau to go back to Panipat and ask Bu Ali Shah, during his next parvāz, to look for a hujrā (a cell or a

chamber) where only a select mashāikh sit. Khusrau did as commanded by his pīr, and Bu Ali Shah agreed

to look for the hujrā mentioned by Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. Upon his return at the time of the early morning

namāz (obligatory Muslim ritual prayer), Bu Ali Shah is said to have exclaimed that he saw Hazrat Nizamuddin

Auliya sitting in that hujrā along with other prominent mashāikh like Huzoor Al-Syed Muhiyuddin Abu

Muhammad Abdul Qadir al-Gilani al-Hasani wal-Hussaini (1077-1166) and Hazrat Sheikh Khwaja Syed

Muhammad Mu’inuddin Chishti, and Prophet Mohammed himself was the mīr-e-majlis (head of the assembly)

of that special gathering. This is the special kaifiyat (mystical arousal) and raqs (whirling) in which Khusrau is

supposed to have written the final couplet of the kalām mentioned above:

Khudā khud mīr-e-majlis būd andar lā-makān Khusrau

Muhammad shamm’-e-mehfil būd shab jāye ke man būdam

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

Aga Khan Trust for Culture128

Right: Image of Pīr Zamin Nizami Syed

Bokhari Khwaja GhulamMuinuddin Nizami, the father ofPīr Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed

Bokhari, the currentsajjādānashīn and mutawallī,

Dargāh Hazrat NizamuddinAuliya. (Courtesy: Pīrzādā Syed

Farid Nizami)

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 128

The banquet’s host was the Lord himself in that placeless place, Khusrau,

Mohammed was the conclave’s candle the place I was last night.7

There are numerous such stories pertaining to the core kalām of the khānaqāhī qawwālī repertoire, granting

them the context from which they are said to have emerged. Thus, there is a kind of circularity between the

text and the context such that the two reinforce and complement each other.

Khānaqāhī Qawwālī and Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

With this, we now turn to the specific case of khānaqāhī qawwālī in Delhi. Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s

khānaqāh (Sufi shrine with residential and training facilities) is located in Ghiyaspur in the north-west edge of

Humayun’s Tomb enclosure. Initially a thatched mud structure, it is now a spacious, two-storey building

comprising a large hall flanked by a verandah of stone pillars. Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya is said to have lived

in a small room on the upper storey but would often climb down for prayers and to meet visitors. The expenses

of the khānaqāh were met from the futuh (unsolicited gift) offered by disciples and visitors. It is said that Hazrat

Nizamuddin Auliya’s khalīfā (head of a spiritual lineage) Hazrat Nasiruddin Mehmood ‘Chiragh-e-Dehli’

observed that in the later years of his life, the flow of offerings into his pīr’s khānaqāh became almost like a

tributary of river Yamuna.

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s wisāl (union with the divine Beloved) took place in 1325, and, in accordance with

his wish, he was buried nearby within the bounds of Ghiyaspur.

“Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq (r. 1325-51) had a dome constructed over the mausoleum, while his

successor, Firuz Shah Tughlaq (r. 1351-88), enclosed the burial chamber with doors made from

sandalwood… Nawab Farid Khan replaced the brick and mortar dome by a marble dome in 1562…

Nawab Murtaza Khan, governor of Delhi, constructed a spacious courtyard around the mausoleum

in 1653. In 1820, Nawab Faizullah Bangash covered the ceiling of the chamber with copper plates,

in which beautiful Persian calligraphy in mother-of-pearl was inlaid. Akbar Shah II (r. 1806-37) had a

golden cupola fixed atop the dome in 1823. Later in the 19th century, Nawab Sir Khurshid Jah Bahadur

of Hyderabad was responsible for installing an exquisite marble railing around the sarcophagus.”8

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi 131

Left:A khānaqāhī qawwālī session inprogress in the same placewhere the Urs Mahal nowstands in Hazrat NizamuddinBasti. c. late 1950s. (Courtesy:Pīrzādā Syed Farid Nizami)

The overt narrative by Sufisexcludes qawwālī by youngboys as being be-shar’ but thisis an example of an exceptionto that rule. At the back arenotes containing the shijrā ofHazrat Nizamuddin Auliya andthe lyrics of “Kāfir-e ‘Ishq-amMusalmānī Marā Darkār Nīst…”,a popular ghazal by AmirKhusrau rendered in thiscollection by GhausMuhammad Nasir Niazi &Group.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 131

Such a continuous chronology of interventions around the rauzā of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya bears testimony

to his spiritual prowess and exalted position among the Chishti Sufis in the Indian subcontinent.

For a long time now, the shrine has been managed by the sajjādānashīn and pīrzādagān. Theoretically, there

should be only one successor in a clear line of descent from the Sufi saint, but this rarely happens in reality.

“At the major shrines of the Chishti silsilā, such as Ajmer Sharīf or Nizāmuddīn Auliyā, entire communities

of such representatives have a hereditary share in managing the shrine’s spiritual and material

benefits. Here too, however, one or several individual leaders stand out as the official representative

or sajjādānashīn, though often under different titles.”9

At present, there are two main claimants to this exalted position as far as Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya

is concerned – Khwaja Syed Hasan Sani Nizami, who is in charge of Khwaja Hall (also known as Qawwālī Hall),

and Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari who heads the Urs Mahal. The multiplicity of claimants in the

dargāh gets exacerbated by the fact that Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya never married and thus all the claimants

either seek authority through their familial connections with his sister or through the spiritual lineage which

springs from him. Khwaja Syed Hasan Sani Nizami’s branch is called the Nabīragān, a family whose family

lineage connects with Baba Fariduddin Ganjshakar’s son-in-law Hazrat Khwaja Syed Badruddin Ishaq Nizami

and his son Hazrat Khwaja Syed Muhammad Imam Nizami who was adopted by Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya;

while Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari’s branch is called the Hindustāniyān, and their family lineage

connects with the families of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s sister Bibi Zainab and his grandfather’s brother Hazrat

Syedna Musa Bokhari. The captions of the shajarās of both claimants gives additional information about the

complicated web of connections members of both families invoke to grant themselves a position of authority.

The primary function of the sajjādānashīn and pīrzādagān is to maintain the shrine, facilitate offerings by

devotees, act on their behalf by forwarding their concerns to the saint, and accept offerings on behalf of

the saint. In effect, they are caretakers of the shrine and refer to themselves as such, using the term khuddām

(attendants). The qawwāl come under the category of ‘servants’ of the shrine and are in a subservient

relationship with the khuddām. The qawwāl recites mystical poetry and is the central figure of samā’, the

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

Aga Khan Trust for Culture132

Right:A khānaqāhī qawwālī session in

progress in the same placewhere the Urs Mahal now

stands in Hazrat NizamuddinBasti. c. late 1950s. (Courtesy:

Pīrzādā Syed Farid Nizami)

Instruments such as the banjoused in this performance is

usually not permitted by Sufis. Inaddition, a qawwāl is also not

supposed to raise his handwhile performing in the

presence of mashāikh but this isan example of an exception to

that rule.

Pages 134 - 135:Meraj Ahmed Nizami at Dargah

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 132

Aga Khan Trust for Culture136

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

Hazrat Muhammad Rasoolullah

Hazrat Ali

Hazrat Syedna Abdullah Khullame

Hazrat Syedna Ali Bokhari

Hazrat Syedna Syed Ahmed

Hazrat Syedna Khwaja Nizamuddin Auliya

Hazrat Syedna Musa Bokhari

Hazrat Syedna Abdur Rahman

Hazrat Syedna Abdullah

Hazrat Syedna Abu Bakr

Hazrat Syedna Azizuddin

Hazrat Syedna Kamaluddin

Hazrat Syedna Abdul Rashid

Hazrat Syedna Syed Ahmed

Hazrat Syedna Syed Daulat

Hazrat Syedna Fazlullah

Hazrat Syedna Hasan

Hazrat Syedna Syed Abdul Sami

Hazrat Syedna Mahmood

Hazrat Syedna Niamatullah

Hazrat Syedna Khairullah

Hazrat Syedna Ubaidullah

Hazrat Syedna Mujibuddin

Hazrat Syedna Rasool Bakhsh

Hazrat Syedna Sirajuddin

Hazrat Syedna Sharfuddin

Hazrat Syedna Ghulam Muinuddin

Hazrat Pir Zamin Nizami Syed Bokhari

Hazrat Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari

Hazrat Muhammad Rasoolullah

Hazrat Ali

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Badruddin Ishaq

(Son-in-law of Hazrat Baba Fariduddin Ganj-i-Shakar)

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Muhammad Imam Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Daud Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Alimuddin Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hussain Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Mubarak Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Muhammad Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Khwaja Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Jalaluddin Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Ayoob Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Abu Muhammad Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Abdullah Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Abdul Qadir Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Abdul Qadir Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Fazl-e-Ali Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hidayat Ali Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hussain Ali Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Ashiq Ali Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hasan Nizami

Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hasan Sani Nizami

SHAJARĀ 01 SHAJARĀ 02

Shajarā 01: Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed

Bokhari refers to his family askhāndān-e-khwāharzādagānal mahrūf Hindustāniyān. Theyare yakjaddī khwāharzāde of

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya –yakjaddī because the

ancestor of Hazrat NizamuddinAuliya and Hazrat Syedna AbuBakr is the same person, Hazrat

Syedna Abdullah Khullame;khwāharzāde because they

descend from Hazrat SyednaAbdullah who married Hazrat

Nizamuddin Auliya’s sisterHazrat Bibi Zainab. Through theformer relation, Hazrat Syedna

Abu Bakr was the paternalnephew of Hazrat Nizamuddin

Auliya and through the latterrelation, he was the maternal

nephew of the saint as well. Inaddition to this familial relation,

the term musallādār, usuallyused for Hazrat Syedna AbuBakr indicates that he was akhalīfā of Hazrat Nizamuddin

Auliya by virtue of having beengranted the musallā (jānamāzor the prayer mat) of the saint.

The mazār of both HazratSyedna Abu Bakr and his sonHazrat Syedna Azizuddin are

within the compound ofDargah Hazrat Nizamuddin

Auliya.

Refrence: “Mir Khurd,” SyedMuhammad bin Mubarak al-

Alawi al-Kirmani, Siyar al-Auliya(Persian lithograph) (Dehli:

Matba-i Muhibb-i Hind, 1885)(reprint edition: Islamabad:

Markaz-i Tahqiqat-i Farsi-i Iran uPakistan, 1978), p. 603.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 136

core activity of zikr within the Chishti silsilā. Thus, ritually, he holds an important position. However, the social

status of the qawwāl is fairly low because of the ambivalent position of music-making within Islam. This

dichotomous social and cultural position of the qawwāl plays out over and over again in numerous

circumstances, from regular qawwālī occasions in Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya on Thursday evenings

to special occasions such as the urs (death anniversary of a Sufi) of the saint and his beloved disciple, Amir

Khusrau.

In terms of numbers, the sajjādānashīn and their family members at Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya are

between 400-500, and the qawwāl birādarī is in the range of 150-200. This huge group of people survives,

mainly, through their ritual entitlements within the offerings made by devotees. At the time of writing there

were seven qawwāl who had a right to mu’atād (token payments distributed from a shrine’s resources):

• Khalil Ahmed Nizami (Hapur gharānā)

• Meraj Ahmed Nizami (Qawwāl Bachche gharānā)

• Mohammed Hayat Nizami (Sikandarabad gharānā)

• Ghulam Hussain Niazi (Hapur gharānā)

• Ghulam Qadir Niazi Nizami (Hapur gharānā)

• Chand Nizami (Sikandarabad gharānā)

• Ghulam Rasool, who does not belong to any artistic lineage and was inducted into the group of

qawwāl as a special case.

The mu’atād is distributed thrice a year – on the urs of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya (17th of the Islamic month of

Rabi-us-Sāni), the urs of Hazrat Amir Khusrau (17th of the Islamic month of Rajab), and on 10th of the Islamic

month of Muharram. During both urs, Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti qawwāl distribute venues amongst themselves,

making sure each venue gets covered. At the end of the urs, they usually sit together in the Urs Mahal, pool

in the nazrānā (formal offering in a samā’ gathering) received, and divide it equally amongst themselves. In

2009, during the urs of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, this amounted close to Rs. 10,000/- per group.

Khānaqāhī Qawwālī: Order of Events and adab-ādāb

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Shajarā 02 (Opposite page): Hazrat Khwaja Syed Hasan SaniNizami refers to his family askhāndān-e-nabīragān. Theydescend from Hazrat KhwajaSyed Badruddin Ishaq, who wasthe son-in-law of HazratNizamuddin Auliya’s pīr BabaFariduddin Ganj-i-Shakar.According to Mir Khurd’s Siyaral-Auliya, Hazrat NizamuddinAuliya also received spiritualknowledge from SyedBadruddin Ishaq and adoptedhis son Hazrat Khwaja SyedMuhammad Imam Nizami(known popularly as ‘DadaMaulana’), whose mazār lies tothe west of Chaunsath Khambain Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti.Muhammad Imam learnt TheHoly Qur’ān from HazratNizamuddin Auliya and wasgranted the permission toaccept disciples and inductthem into what would later becalled the Chishti Nizami silsilā.

Irfan Zuberi 137

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 137

A standard khānaqāhī qawwālī occasion proceeds in the following manner:

1. Qur’ānkhānī (recitation from The Holy Qur’ān):

• fātehā, prayer for the dead which is usually conducted by the Sufi leader of the gathering.

• qir’at, recitation of passages from The Holy Qur’ān which is done by the Sufi leader and other

competent members of the gathering.

• shajarā, genealogy of the saint which is usually recited by the Sufi leader.

• duā, intercessory prayer for the entire community in general, and everyone present in particular

which is usually conducted by the Sufi leader.

2. Qawwālī performances, either by groups taking turns or panchāyatī (communal singing) with the

following structure of repertoire recited:

• rang, which celebrates the wisāl of the Sufi saint in whose memory the gathering is being held.

The compositions of rang usually sung are “Āj rang hai ai mā…” and “Mohe apne hī rang mein

rang le rangīle…” both of whom are attributed to Amir Khusrau and have been rendered by

Mohammed Ahmed Warsi Nasiri in this compilation.

• qaul (saying of Prophet Mohammed adapted in the samā’ format), which is also a hadīs (saying

or action of Prophet Mohammed) and is thus considered to be especially auspicious. It also

establishes a spiritual relationship with Hazrat Ali, and through him, with Prophet Mohammed. The

most commonly sung qaul is “Man kunto maulā…” whose musical composition is attributed to

Amir Khusrau and has been rendered in the compilation by Mohammed Ahmed Warsi Nasiri.

• na’t, which is the praise of Prophet Mohammed.

• manqabat, which is usually in the praise of Sufi saints mentioned in the shijrā.

• nisbatī kalām, which is poetry which emphasizes links with a Sufi figure or lineage and turns

people’s hearts towards tasawwuf.

3. Qur’ānkhānī and fātehā usually conducted by the Sufi leader.10

Thus far, we have placed the qawwāl in the centre of our discussion. However, it is more than apparent from

above that no khānaqāhī qawwālī occasion is complete without the participation of Sufis – as mīr-e-mehfil

(head of the samā’ gathering), participants and overseers of the session. First and foremost, Sufis emphasise

Aga Khan Trust for Culture138

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 138

upon the adab-ādāb of the session by drawing upon a framework, which has been laid down and adhered

to (at least in principle) for as far as memory goes. Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali lays down the etiquette

thus:

1. Listening requires three things: the (appropriate) time, place, and companions. [These are referred

to by Sufis as zamān, makān and ikhwān respectively.]11

2. Some novices are not considered suitable: those who have no ‘taste’ for it; those whose passions

are still strong so that there is an undesirable gratification of desires; those who are ignorant of spiritual

and theological knowledge; and those whose heart is preoccupied by worldly concerns.

3. The listeners should be silent, attentive, still and sit with a bowed head. If one is overcome by wajd

(spiritual whirling) resulting in involuntary movements, one should return to a quiet state as soon as

this passes. In fact, the most perfect form of trance is that which produces complete stillness.

4. Restraining oneself from ecstatic activity or from weeping is desirable, but dancing and weeping is

acceptable provided there is no deception or pretence in these activities.

5. The assembly’s approval should be sought for whatever activities are carried out including following

the particular group’s customs.12

These are still considered to be the overarching principles governing samā’ in general and khānaqāhī

qawwālī in particular. Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari, sajjādānashīn and mutawallī (caretaker of a

Sufi shrine) Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya lists the following restrictions on samā’ in addition to the ones

mentioned above:

• ba-shar’ (in accordance with Islamic law) and (one who has performed ablutions in accordance

with Islamic law) – Sufis, qawwāl and other participants should ideally belong to the path of Sufism.

• ba-wazū (one who has performed ablutions in accordance with Islamic law) – Sufis, qawwāl and

other participants should do the ritual ablutions before sitting in a samā’ gathering.

• qawwālī by women is considered be-shar’ (in contradiction with Islamic law); qawwālī by young

boys is also frowned upon.

• qawwālī should be conducted only with the use of daf; all other musical instruments are not

considered appropriate for use; and

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi 139

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 139

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi 141

• if one feels kaifiyat, one should act with as much perseverance, inner strength and patience to

prevent oneself from hāl khelnā (expressing a state of ecstasy) which is largely considered to have a

derogatory connotation.

A significant exception to this structure of rules and regulations relates to kaifiyat since such a state is inevitable

for advanced mashāikh and other Sufi adepts. According to oral history sources, Khwaja Syed Muhammad

Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki (1173-1235) passed away during a state of wajd emanating from hearing the

following lines attributed to Sheikh Ahmed-e Jami (1048-1141):

Kushtgān-e khanjar-e taslīm rā, har zamān az ghaib jān-e dīgar ast13

Those killed by the dagger of submission get a new life from the unseen world.14

However, it needs to be underlined here that the khānaqāhī qawwālī occasion is one that is governed by

strict rules and regulations and it is the Sufis’ responsibility to ensure that all participants stay as close to them

as possible.

Even so, the realist in Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari is quick to point out that, “out of all the restrictions

prescribed for samā’, what we can and do insist upon in this day and age is to ensure that no qawwāl sings

filmī songs or songs which turn the people towards the world and its associated elements, discourage filmī

tunes, discourage men-women competitions and other such improper practices. There exist some khānaqāhs,

whose names should not be disclosed on purpose, where men-women competitions are held because that

is what brings people into the khānaqāhs. I’ve personally gone there and written to the sajjādānashīn to

discontinue such practices because they bring a bad name to tasawwuf. But then again, to insist upon

anything more than this would mean discontinuing samā’ in khānaqāhs altogether!”

Apart from the role of stressing upon the adab-ādāb of khānaqāhī qawwālī occasions, Sufis are also expected

to play the role of mentors to the qawwāl in terms of telling them about the appropriateness of the performed

repertoire, correcting pronunciation and ensuring an overall aural decorum in keeping with the principles of

Chishti Sufism. On numerous occasions, I have noticed both Khwaja Syed Hasan Sani Nizami and Pir Khwaja

Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari intervene in khānaqāhī qawwālī sessions in progress for one or more reasons

mentioned above. For example, Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari stopped the hāzirī (presenting oneself

Left:Pir Zamin Nizami Syed Bokhari,sajjādānashīn and mutawallī,Dargah Hazrat NizamuddinAuliya, conducts a fātehā intāq-e-buzurg, a privatechamber adjacent to thedargāh compound. c. mid-1960s. (Courtesy: Pīrzādā SyedFarid Nizami)

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 141

Aga Khan Trust for Culture142

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

before a Sufi saint) of Mohammed Ahmed Warsi Nasiri & Group in tāq-e-buzurg (a place where a group of

Sufis sit and meditate or preach) because the harmonium (a free-standing hand-pumped reed instrument),

dholak (a cylindrical drum) and tablā (a percussion instrument which consists of a treble and a bass drum)

were too loud to hear the kalām being performed, and the primacy of poetry demanded that the instruments

be toned down to the basic minimum. Similarly, Khwaja Syed Hasan Sani Nizami regularly corrects the Persian

pronunciation of the qawwāl at the khānaqāh of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and, on more than one occasion,

has stopped a hāzirī in progress because he did not find the qawwāl attuned enough to the standards he

expects from the khānaqāhī qawwālī sessions he presides over.

This is the decorum expected at the various ritual locations in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti where khānaqāhī

qawwālī is held. However, for more reasons than just a simple lack of economic patronage, the genre has

moved beyond khānaqāhs and into films, clubs, hotels, wedding parties and performance spaces that have

nothing in common with the ritual context the genre is usually tied to. Understandably, Pir Khwaja Ahmed

Nizami Syed Bokhari is quite vehement in his rejection of such a move while voicing innate desires of qawwāl

when he says, “I ask qawwāl not to term what they sing outside khānaqāh as qawwālī because it brings a

bad name to the entire gamut of tasawwuf. Sadly, commercialisation has meant that the qawwāl sing kalām

which is bāzārī (catering to market tastes) and i’shqiyā (pertaining to human love) – kalām which leads people

on the “wrong path” instead of turning them towards love for God and His Prophet. But this shift towards the

market is also inevitable given that qawwālī has become an occupation rather than a spiritual responsibility.

The transformation is crucial and gets reflected in all arenas including pīrī-murīdī (relationship between a Sufi

guide and disciples) relations.”

Filmī and Techno Qawwālī: Future Trajectories of the Genre

Celluliod representations of qawwālī began with “Āhein nā bharīn shakwe nā kiye…” from Zeenat (1944).

Subsequently, over the next few decades, it got incorporated as a regular feature in the Hindi film soundtrack,

and came to be called filmī qawwālī. In terms of the notion of authenticity vis-à-vis khānaqāhī qawwālī,

musical characteristics of filmī qawwālī include:

1. a closed-ended, non-improvisational form;

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 142

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi 143

2. a time limitation of 6-8 minutes on an average;

3. vocal timbres represented are more akin to crooning rather than a chest-based voice production

as far as khānaqāhī qawwālī is concerned;

4. “cinematic unmooring” or the disconnection between the performer and the audience; and

(perhaps most importantly)

5. the metaphor of spiritual love gets transformed into human love, through its visual representation as

well as through the use of lyrical tropes.15

The late 1990s heralded the onset of the most recent qawwālī incarnation, techno qawwālī. Its emergent

characteristics are:

1. substitution of traditional instrumentation with synthesizers, hyped-up bass and other sampled

electronic sounds; and

2. modernizing pulse-like enhancement of the rhythmic line inducing zikr-like repetition which is visually

represented through a trance-like headbanging.

According to khānaqāhī qawwāl Ghulam Qadir Niazi Nizami: “The electronic arrangement and rhythms used

explains the techno part but I want to ask the composers and singers of these songs about which element of

qawwālī they wish to project through their work? For example, the song “Ali Maulā…” from Kurbaan (2009)

opens with an incomplete and inverted ruba‘i (prefatory opening, usually a quatrain, in a khānaqāhī qawwālī)

whose first line is used later in the song to fit the rhythmic pattern of the song, which proceeds like any other

film song. Just picking up the name of Hazrat Ali does not make a song Sufi!”

The point to be noted is that, in contrast with its predecessor of filmī qawwālī, techno qawwālī indulges in the

borrowing of only certain elements of a khānaqāhī qawwālī, integrating them into the overall structure of the

continuously evolving Hindi film song. Aesthetically, whereas a filmī qawwālī was one-step removed from

khānaqāhī qawwālī and indulged in structural borrowing, techno qawwālī represents the fractalisation of the

entire structure of qawwālī and dismemberment into its various constituent ornamental embellishments used

as stand-alone musical material. For khānaqāhī qawwāl, this shift signifies the mainstream music industry’s

representation of the broader genre of Sufi music, represented through Sufi rock, Sufi fusion, sūfīānā (an

adjective of sūfī) and the like.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:49 Page 143

145

Left:A group of qawwāl offer hāzirīin front of the rauzā of HazratNizamuddin Auliya while adevout fans the audience.(MAS)

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:50 Page 145

Aga Khan Trust for Culture146

Jashn-e-Khusrau: A Collection

Coming back to the question of patronage, the khānaqāhī qawwāl operate in a situation, which is slipping

from their hands at a rapid pace given the direction the mainstream representation is heading towards. For

them, the real and present danger is that of being squeezed out completely if they don’t toe the line of the

market. The following line by Amir Khusrau represents their situation quite appropriately:

Bahut kathin hai dagar panghat kī…

The path to the well (of nectar) is very difficult…

This conveys the difficulty of the road ahead, which is fraught with problems for khānaqāhī qawwālī as a

genre and khānaqāhī qawwāl as a community. Perhaps one of the few sources of comforts vis-à-vis this issue

is that the genre of khānaqāhī qawwāl is self-propagating due to its salient characteristic of being a ritual

duty of the performers. The shrines will always be the safe havens of the khānaqāhī qawwāl, providing them

with an avenue for sustained patronage. The network of the patron and artist enshrined together in a web of

patronage around Sufi shrines is something which has survived for over 750 years and should be celebrated

as a viable traditional system. Whether this avenue is or will be viable by itself for the khānaqāhī qawwāl

community is an entirely different question altogether, and needs a much more thoroughgoing engagement

with the landscape of Chishti shrines in the Indian subcontinent.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:50 Page 146

Art, Artists and Patronage: Qawwālī in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti

Irfan Zuberi 147

Oral history sources based on interviews with:Sajjādānashīn and Pīrzādagān

Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari – 15 September 2010 and

2 February 2011

Farid Ahmed Nizami – 20 December 2010

Navid Pasha Nizami – 20 November 2010

Qawwāl

Fariduddin Ayaz Qawwal – 12 & 22 June 2010

Ghulam Hussain Niyazi Qawwal – 28 October & 1 November 2010

Ghulam Qadir Niyazi Nizami Qawwal – 15 September 2010

Iftekhar Ahmed Qawwal – 6 October 2009 & 28 September 2010

Mer’aj Ahmed Nizami Qawwal – 4 & 30 August 2010

Mohammed Ahmed Warsi Nasiri Qawwal – 29 September 2010

Notes and References:1. Kenneth S. Avery, A Psychology of Early Sufi Samā’: Listening andAltered States (London & New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), p.1.

2. Jean During, Musique et extase: L’audition mystique dans latradition soufie (Paris: Albin Michel, 1988), p.13.

3. There are differing accounts about the number of young boys

rounded up by Amir Khusrau with the numbers ranging from 3 to 12.

The present paper is taking the view of Fariduddin Ayaz of the

Qawwāl Bachche gharānā as being the closest to an ‘authentic’

oral history account given his knowledge about the artistic lineage

he claims to be affiliated with.

4. There is substantial debate around this couplet in terms of

attribution. This point has been alluded to in Sunil Sharma’s paper in

this volume as well. While oral history sources attribute it as a stand-

alone couplet with the first line being said to have been uttered by

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and the second by Amir Khusrau, I have

recently seen it in the dīvān (collection of poetry) of Amir Hasan Sijzi,

published from Hyderabad in 1933, as a complete ghazal.

5. Translated by Dr. S. M. Yunus Jaffery and Prof. Paul Edward

Losensky.

6. Translated by Dr. S. M. Yunus Jaffery and Prof. Paul Edward

Losensky.

7. Translated by Dr. S. M. Yunus Jaffery and Prof. Paul Edward

Losensky.

8. Abdur Rahman Momin, “Delhi: Dargah of Shaykh Nizamuddin

Awliya”, in Dargahs: Abodes of the Saints, eds. Mumtaz Currim &

George Michell (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2004), p. 35.

9. Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound,Context, and Meaning in Qawwali (Pakistan: Oxford University Press,

2006), p. 92.

10. Ibid., p. 116.

11. Pir Khwaja Ahmed Nizami Syed Bokhari, Foreword, Jashn-e-

Khusrau proceedings.

12. al-Ghazali, Abu Hamid Muhammad, Ihyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn (Revivalof the Religious Sciences), quoted in Kenneth S. Avery, A Psychologyof Early Sufi Samā’: Listening and Altered States, pp. 45-6.

13. It is worth noting that this line has also been “poetically quoted”

by Amir Hasan Sijzi. The interested reader will find it to be the last line

on folio number 86 of the dīvān of Amir Hasan Sijzi in the digital man-

uscript collection of Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. The

link to a low-resolution JPEG image of the folio is http://www.thedig-

italwalters.org/WaltersMss/W650/data/W.650/sap/W650_000086_sap

.jpg.

14. Translated by Dr. S. M. Yunus Jaffery.

15. Natalie Sarrazin, Sublimating the Sufi: Sonic Imaging of Qawwaliin Hindi Film, paper presented at the conference of Society for

Ethnomusicology, Wesleyan University, Connecticut, October 2008.

05 Jashn e Khusrau Proceedings_Paper_Irfan Zuberi_SH_Layout 2 15-09-2011 AM 8:50 Page 147