Flórez Estrada, Álvaro, 1765-1853 Exámen imparcial de las ...

Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo's Musical Patronage in Florence, 1765–1790, as Reflected in the...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo's Musical Patronage in Florence, 1765–1790, as Reflected in the...

JOHN A. RICE

Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo’s Musical Patronage in Florence, 1765–1790, as Reflected in the Ricasoli Collection

An expanded version of a paper given at the inaugural conference for the Ricasoli Collection, University of Louisville, March 1989, and the meeting of the AMS-Midwest Chapter, Chicago, September 1989; updated in March-April 2014; further revised and published on Academia.edu

in December 2016

The publication in 2012 of a thematic catalogue of the Ricasoli Collection of printed and manuscript music1 and the digital publication of the collection itself on the IMSLP website brought back memories of an international conference held in 1989 to celebrate the preservation of the collection (through the efforts of Robert L. Weaver) and its acquisition by the Dwight 1 The Music Library of a Noble Florentine Family: A Catalogue Raisonné of Manuscripts and Prints of the 1720s to the 1850s collected by the Ricasoli Family now Housed in the University of Louisville Music Library. With Essays on the History of the Collection and on Music in the Ricasoli Chapels and Household by Robert Lamar Weaver, ed. Susan Parisi, catalogue compiled by John Karr, Caterina Pampaloni, and Robert Lamar Weaver, Sterling Heights, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 2012.

2

Anderson Music Library at the University of Louisville. The new accessibility of the Ricasoli Collection suggested the idea of publishing online an updated, expanded version of the paper I gave on that happy occasion more than two decades ago.

Members of several branches of the Ricasoli family of Tuscany assembled the music collection now in Louisville during the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, but the most important contributors to the collection were Pietro Leopoldo Ricasoli Zanchini (1778–1850) and his wife Lucrezia Rinuccini (1779–1827), both enthusiastic musicians and generous patrons.2 The collection testifies to the vigor and diversity of the musical life that Florence enjoyed during the period in which it was formed. In it are represented many of the genres successfully cultivated in Florence, including comic and serious opera, ballet, church music, oratorio, the sonata, and the concerto. In it too are represented many of the musicians who performed and composed in Florence, or whose music was performed there.

As a reflection of Florentine musical life, the Ricasoli Collection also bears witness to the patronage of Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo, who ruled Tuscany from 1765 to 1790 (and who gave his name to Pietro Leopoldo Ricasoli). The grand duke directed his patronage in several directions. As protettore of the leading theaters of Florence he was generous in his subsidies, and exercised correspondingly large influence over important theatrical decisions. He had in his service several musicians, both vocal and instrumental, who spent much of their time in Florence performing not only at court but also in churches and theaters. In addition to virtuosi di camera the court also supported an orchestra, chorus, and maestro di cappella for the performance of sacred music in the court chapel and, on special occasions, in the Duomo and other churches. Pietro Leopoldo made sure that his many children were given musical instruction; this tutoring represented a livelihood, and an important source of prestige, for several Tuscan musicians.3

The small size of Pietro Leopoldo’s capital enhanced the effect of his musical patronage. According to a census made in 1765, the year of his arrival, Florence had some 73,000 inhabitants, of whom only 106 were full-time professional musicians.4 If those figures are even 2 See Robert Lamar Weaver, “The Ricasoli Collection: Its History and Cultural Background,” and “Music in the Chapels and Household, 1777–1850: Evidence from the Ricasoli Archives,” in The Music Library of a Noble Florentine Family, 3–69. 3 On Pietro Leopoldo as musical patron and other aspects of musical life in Florence during the second half of the eighteenth century see Marita McClymonds, “Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito and Opera Seria in Florence as a Reflection of Leopold II’s Musical Taste,” Mozart-Jahrbuch 1984/85, 61–70; John A. Rice, Emperor and Impresario: Leopold II and the Transformation of Viennese Musical Theater, 1790–1792, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1987, 14–45, 187–203, 270–74; Marcello De Angelis, La felicità in Etruria, Florence: Ponte alle Grazie, 1990; Robert Lamar Weaver and Norma Wright Weaver, A Chronology of Music in the Florentine Theater 1751–1800, Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 1993, 35–80; Christine Siegert, “Zwischen öffentlicher Präsenz und höfischer Exklusivität: Musikerrinnen in der Florentiner Gazzetta toscana, 1766 bis 1790,” Musik, Frau, Sprache: Interdisziplinäre Frauen- und Genderforschung an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hannover, ed. Kathrin Beyer and Annette Kreutziger-Herr, Herbolzheim: Centaurus-Verlag, 2003, 263–76; Christine Siegert, “Cherubinis Vater: Ein Florentiner Musiker in der zeiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts,” Studien zur italienischen Musikgeschichte 16, ed. Markus Engelhardt (Analecta musicologica 37), Laaber: Laaber-Verlag, 2005, 229–52; Christine Siegert, Cherubini in Florenz: Zur Funktion der Oper in der toskanischen Gesellschaft des späten 18. Jahrhunderts (Analecta Musicologica, vol. 41), Laaber: Laaber Verlag, 2008. 4 Antonio Zobi, Storia civile della Toscana dal MDCCXXVII al MDCCCXLVIII, II, Florence: Milini, 1850, Appendice V, summarizes the findings of a census taken in 1765, which puts at thirty-one the

3

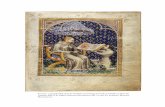

remotely accurate, it is easy to understand how the grand duke could have influenced the musical life of the capital. And it is easy to understand how his musical activities could have helped to shape private collections of music such as that assembled during his reign by the Ricasoli family. Traditions of Musical Patronage in Vienna and Florence Peter Leopold, archduke of Austria, was born in Vienna in 1747; he grew up at the Habsburg court, surrounded by music-making and musical patronage. His mother Empress Maria Theresa saw to it that Leopold, like all his siblings, had thorough musical training. Leopold’s tutor Count Franz Thurn reported to Maria Theresa in 1762 that the fifteen-year-old archduke “was inclinded much more to the harpsichord than the violin.” The empress responded: “The violin must be attended to, and that is already the fourth time this has been ordered.” It was not the violin, however, that Leopold played on 24 January 1765, a few months before travelling south to begin his reign as grand duke of Tuscany, when he directed from the keyboard the premiere of Gluck’s Il parnaso confuso at Schönbrunn. This performance was undoubtedly the highpoint of Leopold’s experiences as a practicing musician, and we are thus fortunate to have a painting of the occasion in which Leopold is depicted at the harpsichord (Fig. 1).5

The reasons for Leopold’s musical training were never clearly stated. Certainly a knowledge of and an appreciation for music were among the social graces expected of an eighteenth-century gentleman. It is also true that a long-standing tradition encouraged Habsburg princes and princesses to musical proficiency. Leopold’s namesake Emperor Leopold I had been a competent composer; his mother Maria Theresa, a student of Wagenseil, was a talented singer; his brother Joseph, emperor from 1765 to 1790, played the keyboard and cello; Marie Antoinette was one of several of his sisters who played the keyboard. Behind the training was the assumption that Leopold, as sovereign, would have to make crucial decisions about music with repercussions beyond the theater and the concert room. And in fact he faced many such decisions both in Florence and, when he succeeded his brother Joseph as emperor, in Vienna.

number of Maestri e professori di musica in Florence, and at seventy-five the number of suonatori diversi. 5 Adam Wandruszka, Leopold II., Erzherzog von Österreich, Grossherzog von Toskana, König von Ungarn und Böhmen, Römischer Kaiser, 2 vols. Vienna: Herold, 1963–1965, is still the most satisfactory biography of Leopold. On Leopold’s youth in Vienna see Wandruszka, I, 15–120. For Count Thurn’s report see Alfred von Arneth, Briefe der Kaiserin Maria Theresia an ihre Kinder und Freunde, 4 vols., Vienna: Braumüller, 1881, IV, 27. The empress’s response, “Das Violinspiel soll gepflegt werden und das ist schon das vierte Mal, dass das angeordnet wird,” is quoted in Wandruszka, I, 51. For a description of the premiere of Gluck’s Il parnaso confuso see the preface to the opera, edited by Bernd Baselt in Gluck’s Sämtliche Werke, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1970.

4

When Gian Gastone, grand duke of Tuscany, died in 1737, with him died the Medici dynasty that had ruled Tuscany for over a century. Tuscany became a pawn in the diplomatic chess game of Europe. The War of the Polish Succession was settled in 1738 by assigning Lorraine to Stanislaus, claimant to the throne of Poland and father-in-law of King Louis XV of France, for his lifetime, after which it was to revert to the French monarchy. In exchange for Lorraine the house of Habsburg-Lorraine gained the throne of Tuscany, left vacant by the death of Gian Gastone. Archduke—later Emperor—Francis ruled Tuscany as grand duke from 1738 to 1765. Francis lived in Vienna and exercised his grand-ducal power through the Regency, a governmental bureaucracy consisting mostly of noblemen from Lorraine. Shortly before his death in 1765 Francis abdicated the grand-ducal throne in favor of his second-born son Leopold. The eighteen-year-old grand duke, together with his new wife Maria Luisa, daughter of the king of Spain, arrived in Florence on 13 September 1765.

In Florence, as in Vienna, the ruling family had long dominated musical patronage. Through the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century the Medici family kept for itself the role of Tuscany’s leading patron of music.6 The main theaters of Florence often received subsidies from the grand duke or his relatives, many of whom had singers and instrumentalists on their payroll. Members of the Medici family hired maestri di cappella to compose and direct music for theater, chamber, or church. Money bought influence. Even though theaters that described themselves in printed librettos as “sotto la protezione del Granduca [or Principe] di Toscana” were nominally run by academies (societies of wealthy Florentines, most of them noblemen, who, from the late seventeenth century on, hired impresarios to arrange operas or other entertainment), the Medici princes were in fact more than protectors: they had a say in many 6 On Medici patronage of music during the seventeenth century and first half of the eighteenth see Robert Lamar Weaver and Norma Wright Weaver, A Chronology of Music in the Florentine Theater, 1590–1750, Detroit: Information Coordinators, 1978, to which this account is greatly indebted.

Fig. 1. Archduke Leopold directing a performance of Gluck’s Il Parnaso confuso at Schönbrunn in 1765. Detail of a painting attributed to Johann Franz Greipel

5

important matters such as repertory, composers, impresarios, and casts. Their control over, and their interest in, these matters varied from period to period, from prince to prince, but it generally corresponded to the willingness of an individual prince to provide financial support. A prince who wished an academy or impresario to do his will was usually a generous prince. One of the most enthusiastic, influential, and generous of Medici patrons of music was Prince Ferdinand (1661–1737), brother of Grand Duke Gian Gastone.7 The music-loving prince made his villa at Pratolino a thriving operatic center. Twenty-one singers are known to have been on Ferdinand’s payroll at one time or another—a relationship that benefited both the patron and the musician. For the prince it meant a relatively dependable supply of singers on whom to draw for performances at his villa; for the singers it meant a steady income from the prince. The prince’s reputation as a patron of wealth, generosity, and good taste was spread by his singers, who, when they were not needed by Ferdinand, sang in the greatest theaters of Italy; the singers, in boasting of their service to the prince in printed librettos, increased their own prestige. Ferdinand also supported composers, including Alessandro Scarlatti and Handel, whom he met in Germany, invited to Italy, and supported with commissions and letters of recommendation. Music interested Ferdinand’s brother Gian Gastone less than it did Ferdinand, but the grand duke nevertheless fulfilled what was by the early eighteenth century practically an obligation, and subsidized the main theaters of Florence. Financial records of the Accademia degli Infuocati for the year 1722 put the grand duke’s contribution at just over 47 scudi, a small fraction of total receipts of just over 2120 scudi, but crucial in keeping the academy from operating in the red.8 In return Gian Gastone received the benefit of being named in librettos as the academy’s protettore, but—and this is no doubt related to the small size of his contribution—he does not seem to have taken an active part in running the theater.9 As successor to the government of the Medici grand dukes, the Regency that governed Tuscany from 1738 to 1765 kept intact the system of laws and regulations built up by the Medici; it also maintained its traditions, including the patronage of musicians and musical institutions. A series of theatrical regulations promulgated by the Regency in the 1740s bears witness to the interest that the Lorrainian government had in the musical life of Florence and to the power that the Regency wielded over musical institutions. Some rules dealt with the scheduling of the various theaters so that one theater might not rob another of its audience. These rules gave certain privileges to the Accademia degl’Immobili, the most aristocratic of the academies, devoted to the presentation of opera seria in the largest theater in Florence, the Teatro di Via della Pergola. Some rules specified the kind of financial arrangements that the academies might enter into with the impresarios they hired to manage the opera. Admission and subscription prices were fixed. Other regulations sought to maintain order in the theaters, forbidding “extraordinary applause that might be found indecent to the dignity of a theater qualified by the protection of this sovereign,” and specifying the nights on which the Regency permitted the wearing of masks in the theater. In their pervasiveness these regulations went beyond any Medicean theatrical rules. They made explicit what had for a long time been implicitly acknowledged by all concerned: that the grand-ducal court could tightly control the

7 Mario Fabbri, Alessandro Scarlatti e il Principe Ferdinando de’ Medici, Florence: Olschki, 1961. 8 Weaver and Weaver, 1590–1750, 42. 9 On the production of opera during the reign of Gian Gastone see William C. Holmes, Opera Observed: Views of a Florentine Impresario in the Early Eighteenth Century, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993

6

theaters of Florence, wielding through them much influence over the musical life of the Tuscan capital.10 It should be clear from the above that Archduke Leopold, when he became Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo in 1765, inherited a government that regarded the supervision and patronage of theater and music as among its major concerns. Operatic Subsidies During the spring of 1767 Felice Alessandri’s comic opera Il matrimonio per concorso was performed in the Teatro di Via del Cocomero in Florence. The libretto, dedicated to Grand Duchess Maria Luisa, is embellished with a portrait of her. The preface, addressed by impresario Giovanni Roffi to her, expresses gratitude for “the sovereign patronage that this theater enjoys,” and goes on to explain why such patronage benefits the ruler as well as the ruled:

The amusement of the public, together with the admiration of an ecstatic crowd of spectators, manifests itself so openly when theatrical productions are made worthy of the longed-for presence of our august masters, because it is possible honestly to assert that the happy age of the Tuscan theater’s revival has arrived, and because the productions will soon be envied, or at least imitated, by the most cultured of foreign nations. What glory for us! What moral profit will surely be derived for the people, on whom the theater has so much influence, when it is instructive and well regulated, so that it leads to their improvement.11

We can sense in Roffi’s convoluted prose some of the richness of symbolic meaning the theater held for eighteenth-century minds. “The public” was for Roffi a much larger group than the audience in the Cocomero. The public in a wider sense, the population of Tuscany, was pleased when the theater could present performances worthy of the sovereign—that is, performances whose lavishness grand-ducal patronage made possible. When Roffi wrote of “the happy age of the Tuscan theater’s revival” he hinted at a more important risorgimento: the revival of Tuscany itself under Pietro Leopoldo’s leadership. Only as a symbol of the state—of its wealth, its taste, its orderliness—can performances on the stage of the Cocomero be understood as something to be imitated and envied “by the most cultured of foreign nations.” The patronage to which Roffi alluded consisted of subsidies paid by the grand-ducal court directly to the impresario, who submitted a bill after each opera season. Payments to Roffi consisted partly of remuneration for grand-ducal boxes in the theater and partly of an honorarium to the impresario. Once Pietro Leopoldo granted subsidies to some impresarios it was difficult to deny them to others. This was clear to Antonio Fabbrini, impresario of the small Teatro di Via Santa Maria, who wrote to the grand duke early in 1768, asking for an annual subsidy for this theater. He pointed out that Pietro Leopoldo had already displayed his generosity to three other 10 Weaver and Weaver, 1590–1750, 49–55, summarize and discuss the regulations. 11 La pubblica ilarità congiunta all’ammirazione di una folla estatica di spettatori, si manifesta tanto svelatamente, allora quando le sceniche rappresentazioni son fatte degne delle sospirata presenza delli Augusti nostri Padroni, che si può asserir francamente esser giunta l’epoca fortunata del loro risorgimento in Toscana, e che verrano invidiate, o almeno imitate ben presto da quelle delle più culte straniere Nazioni. Qual gloria allora per noi! qual vantaggio morale dovrà derivarne nei popoli, su i quali ha tanta influenza la comica istruttiva e ben regolata perchè divengan migliori (Il matrimonio per concorso, dramma giocoso per musica, Florence: Anton Giuseppe Pagani, 1767, 4).

7

theaters, the Pergola, the Cocomero, and the Teatro della Piazza Vecchia di Santa Maria Novella. Fabbrini’s appeal was at least partly successful: a note at the top of the letter records that the sum of Lire 333.6.8 was granted the impresario, though no mention was made of an annual subsidy.12 By 1780 it had become the custom for all impresarios to submit bills to the court after every season. Grand-ducal payment records show that the court granted a total of 11,245 Lire to five impresarios to defray the costs of theatrical productions during Carnival 1780 (see Appendix 1). The largest payment, 4560 Lire, went to Andrea Campigli, impresario of the Pergola: 4000 Lire “per il suo solito onorario,” and 560 Lire for the renting of two boxes. Pietro Leopoldo’s largesse was not limited to Florence. He granted large sums to the impresarios of other Tuscan cities such as Siena and Pisa to help pay for performances during his stays in those cities.13 Grand-ducal subsidies allowed the impresarios to hire better singers and composers, to commission more elaborate costumes and scenery, than they could otherwise have afforded. The subsidies thus presumably improved the quality of Tuscan theater. But there was another reason why Pietro Leopoldo went to such great expense. By means of his subsidies he encouraged impresarios to become financially dependent on the court; the more dependent they were, the more open to grand-ducal influence.14 Grand-Ducal Singers One way in which Pietro Leopoldo influenced the theaters, and Florentine musical life in general, was through his virtuosi di camera, singers hired mostly for the performance of chamber music and sacred music at court. But they also played an important role in the theaters, concert-rooms, churches, and oratorios of Florence. As employees of the court, they were likely to do what pleased the sovereign when decisions had to be made concerning repertory, casting, style of performance, and so forth. We have seen that the Medici grand dukes and princes had long made it a practice to put singers on their payrolls. But during the Regency few singers claimed the patronage of the grand-ducal court in librettos. This no doubt reflected the absence of Grand Duke Francesco (Emperor Francis I), whose musical interests are revealed more clearly in Viennese music (especially the predominance of opéra-comique during the 1750s and early 1760s) than in the music of Florence.15 During his first decade in Tuscany Pietro Leopoldo went a long way toward reviving the Medici tradition of largesse toward singers. By allowing his name to appear in librettos next

12 Florence, Archivio di Stato (hereafter abbreviated AS), Imperiale e Reale Corte (hereafter abbrievated IRC), Filza 202, No. 117. 13 Pietro Leopoldo made payments of 2000 Lire each to the impresarios of the principal theaters of Siena and Pisa “per le opere rappresentate in occasione della sua permanenza nelle dette città di aprile, e maggio [1767],” according to a payment record dated 12 June 1767 (AS, IRC, Filza 1745, No. 61). 14 For further discussion and documentation of operatic subsidies in Florence, see Siegert, Cherubini in Florenz, 199–201. 15 On the patronage of singers by the Medici grand dukes and princes see Weaver and Weaver, 1590–1750, 65–69 and, on the paucity of singers receiving grand-ducal patronage under the Regency, 71. On Emperor Francis’s large role in establishing French culture and taste in Vienna see Bruce Alan Brown, Gluck and the French Theatre in Vienna, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991, 30–34.

8

to the names of his virtuosi di camera, he made himself known throughout Italy, and beyond the Alps as well, as an enthusiastic patron of vocal music. At least seven professional singers associated themselves with Pietro Leopoldo in librettos, describing themselves as “virtuoso del Granduca di Toscana” or “al servizio del Granduca di Toscana.” Dates in Table 1 are the earliest and latest years in which the singers are known to have been in Pietro Leopoldo’s service; in some cases a singer may have retired from the theater by the later date, but was still on the grand-ducal payroll. Not all these singers received money from the grand duke; Antonio Goti, for one, had to be satisfied with the honor of being able to call himself a grand-ducal virtuoso in printed librettos. Male sopranos and altos, specialists in opera seria and church music, were the main beneficiaries of grand-ducal patronage. Opera seria, more aristocratic in tone, more expensive and prestigious than opera buffa, befitted a sovereign’s dignity. This was as true in Florence as it was in Naples, for example, where the Royal Theater of S. Carlo limited itself almost entirely to the performance of opera seria and ballet. “A simply play of fantasy, that is to say, a lightweight commedia giocosa, cannot merit the honor of Your Royal Highness’s attention.” These words, again from Roffi’s preface to Il matrimonio per concorso (1767), are not meant to be taken completely seriously; but they do reflect the comparatively low status of the genre and help explain why Pietro Leopoldo directed his patronage of singers mainly toward those who specialized in opera seria. The patronage of musici may also reflect their usefulness as performers in the court chapel and other churches, where female sopranos were not normally allowed to sing. The tenor Boscoli and the bass Gherardi were engaged, in contrast, for their comic abilities. In planning for the production of an opera buffa, Florian Gassmann’s I rovinati, at the grand-ducal villa of Poggio a Cajano in October 1773, Count Franz Thurn, Maggiordomo maggiore, instructed the grand-ducal music director to use Boscoli and Gherardi in the production.16 At least four of Pietro Leopoldo’s virtuosi—Giovanni Manzoli, Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci, Antonio Goti, and Giacomo Veroli—were natives of Tuscany; a fifth, Tommaso Guarducci, was a native of Montefiascone or Viterbo, just south of the Tuscan border.17 Three were singers of international renown: Manzoli, Guarducci, and Tenducci. The first two of these were already past their prime and near retirement when they entered Pietro Leopoldo’s service. He may have awarded them positions at his court to take advantage of their retirement in or near Tuscany, or to induce them to retire there. These aging primi uomini could no longer demand the enormous fees they had earned in their prime; yet their names were still familiar to music-lovers all over Europe and commanded the same respect they always had.

16 Thurn to Eugenio di Ligniville, 1 August 1773, AS, IRC 5434, fol. 85. 17 Veroli and Goti were both natives of Arezzo, according to the portrait of Veroli reproduced here, the libretto for L’arrivo d’Enea in Lazio (in which Veroli performed), and a libretto for La fiera di Sinigaglia, in which Goti performed. The portrait of Manzoli announces his Florentine birth. Tenducci was probably born in Siena; see Dale E. Monson, “Galuppi, Tenducci, and Montezuma: A Commentary on the History and Musical Style of Opera Seria after 1750,” Galuppiana 1985: Studi e ricerche, Florence: Olschki, 1986. Guarducci, usually said to have been born in Montefiascone, is described as “da Viterbo” in the libretto Venere placata (Livorno, 1760).

9

Table 1. Professional Singers in Grand-Ducal Employ, 1765–1790 _______________________________________________________________________ Giacomo Veroli (1766–1790), soprano18 Tommaso Guarducci (1766–1790), soprano19 Giovanni Manzoli (1768–1790), soprano20 Giusto Ferdinando Teducci (1772–1776), soprano21 Antonio Boscoli (1773–1775), tenor22 Giovanni Battista Gherardi (1773–1790), bass23 Antonio Goti (1774–1777), soprano24

18 The appointment of Giacomo Veroli to grand-ducal service was announced in the Gazzetta toscana (henceforth abbreviated GT), 1766, p. 62 (article dated 17 April): “Come pure S. A. ha premiato largamente il buon servizio del Sig. Giacomo Veroli esperto Professore di musica accordandoli luogo nella sua Real Cappella, e dichiarandolo musico di Corte con annua generosa pensione, e colla libertà di scegliere a suo modo una stagione per profitare di una recita, ec.” Veroli was still on the grand-ducal payroll at the time of Pietro Leopoldo’s departure for Vienna in 1790 (AS, IRCL, Filza 123, fols. 105–123). 19 Guarducci’s appointment was announced in GT 1766, p. 123 (article dated 27 July): “Questa mattina si è portato all’Imperiale il Sig. Tommaso Guarducci a render le dovute grazie a S. A. R. del dono ricevuto per mano di sua Ecc. il Sig. Conte di Thurn di una superba scatola d’oro smaltata a basso rilievo, e dell’onore compartitolo nel dichiararlo Virtuoso di Camera con una grossa annua Pensione, e con la libertà di poter profittare altrove di qualunque recita.” Guarducci was still on the grand-ducal payroll at the time of Pietro Leopoldo’s departure for Vienna in 1790 (AS, IRCL, Filza 123, fols. 105–123). 20 The appointment of Manzoli was announced in GT 1767, p. 202 (article dated 5 December): “questo rinomato cantore oltre ad aver riportato l’onororio di 600. zecchini per le recite fatte nel passato autunno in questo teatro di via della Pergola, è stato graziato da S. A. R. di un’annua pensione di scudi 300. avendolo ammesso al ruolo de’ Suoi Virtuosi di Camera.” Manzoli was still on the grand-ducal payroll at the time of Pietro Leopoldo’s departure for Vienna in 1790 (AS, IRCL, Filza 123, fols. 105–123). 21 The appointment of Tenducci was announced in GT 1772, 22 (article dated 8 February): “il medesimo ha ricevuto un Diploma col quale S. A. R. nostro Sovrano si è compiaciuto dichiararlo suo virtuoso di Camera, e di ammetterlo all’attual servizio.” Tenducci described himself in librettos as in Pietro Leopoldo’s service until 1776; he seems to have severed his connections with the grand duke when he returned to England shortly thereafter. 22 Boscoli is referred to as “recently admitted to the sevice of the grand duke” in a letter from Count Thurn to Ligniville dated 1 August 1773 (AS, IRC 5434, fol. 85). He described himself as in Pietro Leopoldo’s service in the libretto for a production of Paisiello’s La frascatana, Reggio, 1775. 23 Gherardi is referred to as “recently admitted to the service of the grand duke” in a letter from Count Thurn to Ligniville dated 1 August 1773 (AS, IRC 5434, fol. 85). He was still on the grand-ducal payroll at the time of Pietro Leopoldo’s departure for Vienna in 1790 (AS, IRCL, Filza 123, fols. 105–123). 24 Goti’s appointment is documented in a letter from Count Thurn to Ligniville, 22 July 1774: “Essendo degnata S. A. R. di benignamente accordare la Patente di Virtuoso di Camera al Sig.re Antonio Goti, senza però verun Emolumento annesso alla medesima; Mi do l’onore di trasmetterla a V.S. Ill.ma accio si compiaccia voler ben farlgliela passare” (AS, IRC, 5434, fol. 99). Goti described himself in librettos as in Pietro Leopoldo’s service from 1775 to 1777.

10

Several of the grand-ducal virtuosi had sung in Vienna, and would have thus been familiar to Pietro Leopoldo by reputation if not by experience. Guarducci sang in Vienna from 1752, including the premiere of Gluck’s L’innocenza giustificata in 1755. Veroli was hired in Vienna during the season 1760–61, but does not seem to have had important roles to sing.25 Manzoli (Fig. 2) sang in Vienna several times in the early 1760s, creating the roles of Rinaldo in Traetta’s Armida and Apollo in Gluck’s Tetide (1760). His performance in Hasse’s Alcide al

bivio (1760) was greeted with acclaim. Small wonder that Joseph, writing to his brother the grand duke in October 1765, should envy Pietro Leopoldo’s luck in being able to hear Manzoli, and express disappointment in his brother’s news that the musico’s powers of execution had declined: “Je vous envie bien le plaisir que vous avez eu d’entendre chanter Manzuoli, et la nouvelle que vous me dîtes, qu’il chevrote, est bien triste.”

25 On Veroli’s employment in Vienna see Gustav Zechmeister, Die Wiener Theater nächst der Burg und nächst dem Kärntnerthor von 1747 bis 1776, Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1971, 244. Metastasio mentions Manzoli’s Viennese triumph in a letter to Princess Belmonte dated 13 October 1760: “Il nostro Manzoli è divenuto l’idolo del paese e per la voce, e per l’azione, e per il suo docile, e savio costume, col qual distinguesi da’ suoi pari, non meno che per l’eccellenza nell’arte” (Opere postume del signor abate Pietro Metastasio, ed. Abate Conte D’Ayala, vol. 2, Vienna: Alberti, 1795, 267). Joseph’s letter to Pietro Leopoldo is published in Alfred Ritter von Areth, Maria Theresia und Joseph II. Ihre Correspondenz sammt Briefen Josephs an seinen Bruder Leopold, 3 vols., Vienna: C. Gerolds Sohn, 1867–68, I, 147.

Fig. 2. Giovanni Manzoli fiorentino. The poem reads: “Cigno gentil della città de’ fiori, / E delle Tosche Muse unica spene, / Merti la prima palma e i primi onori, / Anche in giostro del Ciel con le sirene.” (Graceful swan of the city of flowers, only hope of the Tuscan muses, you deserve the palm and the first honors, even in heavenly competition with the sirens.)

Not only did Joseph and Pietro Leopoldo like Manzoli; so did Grand Duchess Maria Luisa, who could have heard him, along with Tenducci and Guarducci, in some of their many performances at the Spanish court during the 1750s. Referring to the period of mourning that followed the death of Emperor Francis (Grand Duke Francesco) in 1765, Horace Mann, the British legate in Florence, wrote to his friend Horace Walpole:

The Court is still en retraite, which is to last till six weeks complete from the death.... The Great Duchess is extremely tired of this rigour. She wished to hear Manzoli, but was told that any deviation from what had been described from Vienna would displease there. But what hurts here still more is that the theatres are not to be opened for a full year, for such is the etiquette at Vienna.26

As it turned out, the grand duchess had no need to fret. The theaters opened sooner than expected; and, as we know from Joseph’s letter quoted above, the grand-ducal couple were able to hear Manzoli within a month of Mann’s letter, perhaps at a private concert at court.

They also heard Veroli (Fig. 3), a native of Arezzo who sang the title role in L’arrivo d’Enea in Lazio, a componimento drammatico presented in honor of the new grand duke and duchess by the Florentine nobility on St. Leopold’s Day, 15 November 1765. Pietro Leopoldo saw himself represented on stage as a new Aeneas arriving in Italy. Foreign domination glorified through allegory: how better could the Florentine nobility pay hommage to its new sovereign? In 1766 Veroli was granted the post of grand-ducal virtuoso, and the following year we find him performing with Manzoli in Traetta’s Ifigenia in Tauride (a production organized and supervised by the grand-ducal court), and singing extravagant praise of the ruling couple in a cantata composed by Gluck as a prologue to Traetta’s opera.

Unlike some of his musical colleagues at the grand-ducal court, Veroli was never one of the great primi uomini of his time. Nor was he past his prime when entered Pietro Leopoldo’s service. He seems to have begun singing publicly only around 1760. During the next twenty years he sang important roles throughout Italy, though conspicuously few in Florence itself, where he was more in demand as a singer of church and chamber music than of opera. In this he resembled Pietro Leopoldo’s other virtuosi. None of them made regular appearances in Florentine theaters: there was no permanent opera company in Florence as there was, for example, in Vienna. But all of them contributed to Tuscan musical life, not only in occasional—sometimes very special—operatic performances, but also in concerts, church music, and oratorio.

The veteran soprano Tenducci (Fig. 4) took part in one special operatic production shortly after being hired as a grand-ducal virtuoso: a series of performances of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice in September 1771. With these performances Tenducci marked his return to Italy after twelve years in London and Dublin. Tenducci sang the role of Orfeo, which he had sung in London the previous year. The Gazzetta toscana, a weekly newspaper published in Florence from 1766 that contained much information about musical life in Tuscany, praised Tenducci’s performance: “Sig. Ferdinando Tenducci, who portrays Orfeo, and who will soon

26 Mann to Walpole, 20 September 1765, in Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, ed. W. S. Lewis, 48 vols., New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937–1983, XXII, 338–40.

12

make his name famous once again in all of Italy, distinguishes himself not only with his beautiful voice but also with his musical and dramatic skills.”27

Pietro Leopoldo knew Gluck’s pathbreaking opera: he had witnessed the original production in Vienna in 1762.28 He must have been pleased with Tenducci’s performance. Within a few months he hired him as virtuoso di camera. He did not forget Tenducci’s performance as Orfeo. At a concert at court in March 1772 Tenducci sang, at Pietro Leopoldo’s request, “Che farò senza Euridice.”29

27 Il sig. Ferdinando Tenducci che rappresenta Orfeo, e che presto renderà celebre il suo nome ancora a tutta l’Italia, si fa distinguere non solo per la bella voce, quando per il possesso dell’arte musica, e comica (GT 1771, 145 [article dated 14 September]). 28 Leopold Mozart attended one of the first performances of Gluck’s Orfeo in Vienna; he wrote to his friend Lorenz Hagenaueer that he saw Archduke Leopold in the audience (see Mozart: Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, ed. Wilhelm A. Bauer, Otto Erich Deutsch, and Joseph Heinz Eibl, 7 vols., Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1962–75, I, 50–53). 29 “Tenducci fu onorato dalla R. A. S. colla richiesta dell’aria ‘Che farò senza Euridice’ cantata con incontro universale nel Teatro di Via del Cocomero, di cui il Real Duca aveva espressamente fatto portare lo spartito” (GT 1772, 45–46 [article dated 21 March]).

Fig. 3. Giacomo Veroli d’Arezzo professore di musica all’attual servizio di S. A. R. Pietro Leopoldo. Engraving by R. Faucci after a drawing by Carlo Mariotti. The text at the top—“Auritas cantu duceret quercus” (“He would lead the attentive oak with his song”), which refers to Orpheus, is a paraphrase of a line of Latin verse from Carlo d’Aquino’s Della Commedia di Dante Alighieri trasportato in verso latino eroico cantica I. (Naples, 1728): “Auritas cantu potuit qui ducere quercus" (itself a paraphrase of Horace, Odes book 1, No. 12: “Blandum et auritas fidibus canoris / Ducere quercus”).

Fig. 4. Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci, grand-ducal virtuoso, 1772–1776

The grand-ducal singers also took part in the performance of oratorio. Tommaso Guarducci (Fig. 5), in semi-retirement since 1770, and dividing his time between Florence and his country estate in Montefiascone, seems to have been a specialist in the genre. He sang in a series of oratorios in the 1770s remarkable for the number of works by the Bohemian composer Joseph Mysliveček. Several of Pietro Leopoldo’s other virtuosi—Goti, Gherardi, and Manzoli—shared the stage with Guarducci in some of these performances. Table 2. Tommaso Guarducci as a Performer of Oratorio in Florence _______________________________________________________________________ Year Title Composer Grand-Ducal Virtuosi in Cast 1770 Messiah Handel Guarducci 1771 Adamo ed Eva Mysliveček Guarducci, Goti 1773 La passione di nostro Signore Mysliveček Guarducci, Gherardi 1775 Salomone esaltato al trono Zanetti Guarducci, Manzoli 1776 Isacco figura del redentore Mysliveček Guarducci, Gherardi, Goti

14

An almost annual occasion during Lent in Florence was the performance of Pergolesi’s

Stabat Mater for soprano, alto, and string orchestra. One of the earliest of these performances was at the express request of the grand-ducal couple.30 Pietro Leopoldo’s musici (Veroli and Manzoli made themselves particular specialists in these parts) sang the Stabat Mater year after year, until its performance became a hallowed tradition. It is not surprising to find that the Ricasoli Collection contains two manuscript scores of Pergolesi’s masterpiece: a full score (Fig. 6) and a vocal score.

Fig. 5. Tommaso Guarducci

30 “Vollero i Reali Sovrani in questa sera aver la soddisfazione d’udire la Stabat Mater del Pergolese a maraviglia cantata da’ Sigg. Ricciarelli, e Raaff” (GT 1766, 47 [article dated 18 March]).

15

Fig. 6. Title page of one of two manuscript scores of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater in the Ricasoli Collection, Sacra 84b Instrumentalists Payment records in the Archivio di Stato, Florence, document the existence of a small group of musicians employed by Pietro Leopoldo for the performance of chamber music at court. In early 1768 the group included of seven instrumentalists, in addition to the maestro di cappella Carl’ Antonio Campion: the flutist Niccolò Dôthel, the harpist Anna Wettel, the cellist Francesco Piantanida, the oboist Antonio Domenichini, the timpanist Carlo Paternat, and the violinists Giuseppe Codacci and Giorgio Chelotti (see Appendix 2). These were later joined by several other musicians, including the violinists Giovanni Felice Mosell and Pietro Nardini, the doublebass player Giuseppe Corona, and a horn player whose name caused much confusion to Italian typesetters and scribes, who spelled it variously Gaspero Bluntschi, Giovanni Blunckti, and Gaetano Blentschi.

Niccolò Dôthel was principal flutist in the Pergola as well as a member of Pietro Leopoldo’s permanent staff. He was also a prolific composer, publishing much chamber music for flute in Florence, Paris, and London, including quartets for flute and strings, sonatas for flute, violin, and cello, and flute duets. The Ricasoli Collection contains a set of eight sonatas for flute and keyboard (Profana 236) attributed on their title pages to “N. D,” whom the editors of the thematic catalogue have speculatively (but not unreasonably) identified as Dôthel.

16

Fig. 7. Keyboard part for a Sonata in G for flute and keyboard, in a set of eight sonatas attributed to “N. D.” probably Niccolò Dôthel. Ricasoli Collection, Profana 236. As a flute virtuoso in eighteenth-century Italy Dôthel was something of a rarity. Equally rare are portraits of flutists by eighteenth-century Italian artists. Indeed the only one I know is a portrait of an unknown flutist in the Brooklyn Museum (Fig. 8). The anonymous painter might be Angelo Crescimbeni, whose many portraits of musicians in Padre Giovanni Battista Martini’s collection in Bologna are similar in style to the Brooklyn portrait. Is the handsome flutist in a red coat the celebrated Niccolò Dôthel? The violinist Giovanni Felice Mosell, the most distinguished member of a family that included several professional musicians, served for many years as concertmaster of the Pergola orchestra. Like Dôthel he published a considerable amount of music, much of it in Florence. His Tre sinfonie a più strumenti obbligati (Florence: Nicccola Pagani and Giuseppe Bardi) are among the few concert symphonies published in Italy during the eighteenth century. Mosell also wrote string quartets, of which there are two in manuscript in the Ricasoli Collection (Profana 135).

Two other members of Pietro Leopoldo’s ensemble, the oboist Antonio Domenichini and the violinist Giorgio Chelotti, became members of the orchestra of the Teatro degli’ Intrepidi when it was inaugurated in 1779.31

31 AS, IRC, Accademia degli’Intrepidi, Filza 14.

17

The most celebrated of Pietro Leopoldo’s instrumentalists was the violinist Pietro Nardini (1722–1793; Fig. 7). A native of the Tuscan seaport of Livorno, and a student of Tartini, Nardini earned a reputation as one of the finest violinists of the eighteenth century and an excellent composer for his instrument. His career brought him to many of Europe’s musical capitals before he returned to settle in his native land in 1769. His duties at the grand-ducal court were loosely defined.32 In exchange for his salary he seems to have been expected to display his virtuosity as a soloist in violin concertos and chamber music. Nardini performed in innumerable concerts during the 1770s and 1780s, reigning as undisputed leader of Florentine instrumental music.

32 Modern sources call Nardini variously “court music director” (New Grove) or Konzertmeister (Clara Pfäfflin, Pietro Nardini: Seine Werke und sein Leben, Stuttgart: Find, 1935), but he does not seem to have played either of these roles, at least officially In announcing his appointment the GT said only that Nardini was “arrulato con provvisione al servizio di Corte e della Real Camera.” A document in the records of the Maggiordomo maggiore (the official in charge of the financial side of court life) gives Nardini’s title simply as suonatore di violino (AS, IRCL, Maggiordomo maggiore, Filza 19, cited by Pfäfflin).

Fig. 8. Portrait of an unidentified flutist by an unknown eighteenth-century Italian painter, possibly Angelo Crescimbeni (Brooklyn Museum). The paucity of flute virtuosos in eighteenth-century Italy suggests the possibility that this is Niccolò Dôthel.

18

The young Bohemian composer Adalbert Gyrowetz, passing through Florence in the mid 1780s, heard Nardini play. As a favor to the Gyrowetz, Nardini “played a violin sonata, even though he was very old at the time. Nardini considered his purity and sureness of tone, his well controlled, firm command of the bow to be the cardinal virtues of his playing, although he also performed very difficult passages with extraordinary bravura.”33

Nardini was a prolific composer for the violin, but most of his published music appeared before he settled in Tuscany. It is likely that his activity as a composer was mostly limited to the roughly thirty years of his international career. If so, this would help to explain the conspicuous absence of any music by Nardini from Ricasoli Collection.

In addition to his permanent musical staff, Pietro Leopoldo assembled a much larger group of musicians who were on call for part-time work. These professori di musica giornalieri formed an orchestra around the core of permanent employees, and performed with them in court concerts and in services at the court church of S. Felicita. Together they constituted what Burney called “the Gr. Duke’s band.”34 Like his vocal virtuosi, Pietro Leopoldo’s instrumentalists divided their time between performances at court, in churches, theaters, and private residences.

The official responsible for organizing concerts at court was the Marchese Eugenio di Ligniville, Prince of Conca (1730–1778; Fig. 10). One of the many nobles of Lorraine who settled in Tuscany during the Regency, Ligniville took an active part in its government, serving as postmaster-general; he retired from this position in 1766, and shortly thereafter Pietro

33 Adalbert Gyrowetz, Biographie, ed. Alfred Einstein, Leipzig: Siegel, 1915, 19. 34 Burney, Music, Men and Manners, 120. Typical in size and composition was the group assembled for Sunday Mass at S. Felicita on 9 March 1766 (AS, IRCL, Filza 1745, No. 1). The chorus consisted of sixteen singers (four on a part), including the grand-ducal virtuoso Veroli; the orchestra consisted of eight violins (including the grand-ducal instrumentalists Codacci and Chelotti), two violas, one cello, two doublebasses, two oboes (including the grand-ducal instrumentalist Domenichini), one bassoon, two horns, two trombones, and timpani (the grand-ducal instrumentalist Paternat).

Fig. 9. By posing with a piece of music paper, but without his violin, Pietro Nardini conspicuously projected the image of a composer and music director, instead of an instrumentalist.

19

Leopoldo appointed him court music director. 35 Ligniville was a musician and a composer of merit, especially in a strict polyphonic style. His contrapuntal skills are evident in his Stabat Mater a 3 voci in canone, published in Bologna and Florence in at least two editions, and dedicated to Pietro Leopoldo. The title page of Florentine edition, a copy of which is in the Ricasoli Collection (Sacra 47; Fig. 11), describes its author as “Direttore della Musica della Real Corte di Toscana.”36 35 On Ligniville see Duccio Pieri, “Il Marchese Eugenio de Ligniville. Sovrintendente alla musica della Real Camera e Cappella: Un inedito Gluck fiorentino e una querelle musicale con Charles Antoine Campion,” Philomusica on-line 5 (2006), http://riviste.paviauniversitypress.it/index.php/phi/article/view/05-01-SG04/57 Ligniville’s retirement from the position of postmaster general was announced in GT 1767, 165 (article dated 3 October); his appointment as music director was announced in GT 1768, 173 (article dated 8 October). 36 RISM lists two undated editions of Ligniville’s Stabat Mater, one published in Bologna and one in Florence. GT 1767, 66 (article dated 18 April) provides us with a terminus ante quem for the earliest edition: “Fra le molte spiritoso produzioni in musica, che fin’ ad ora si sono sentite del Sig. March. di Ligniville Generale delle Poste in Toscana, per cui ha meritato il pieno voto dell’accreditato Accademia de’ Filarmonici di Bologna, fa prova del suo ingengoso talento una Stabat Mater dal medesimo messa sulle note in canone a tre voci, che presentemente si vede manifestata al pubblico in un libretto stampato in rame.” Since the title page of the edition of which a copy is in the Ricasoli Collection describes Ligniville as Pietro Leopoldo’s music director, and GT announced Ligniville’s appointment to that

Fig. 10. The Marchese Eugenio di Ligniville, portrait by Angelo Crescimbeni, from Padre Martini’s collection of musical portraits in Bologna. Ligniville holds the text of Horace’s Odes, book 3, Ode 3, “Iustum et tenacem propositi virum non civium ardor prava iubentium (“The man who is tenacious of purpose in a rightful cause is not shaken from his firm resolve by the frenzy of his fellow citizens clamoring for what is wrong”): probably a reference to his conservative taste in music.

20

Ligniville’s duties as music director must have been challenging. He kept track of the differing—and often conflicting—schedules of court musicians. He arranged for the appearance of traveling virtuosi, as when Mozart, touring Italy with his father in 1770, performed before Pietro Leopoldo. “Everything went off as usual,” wrote Leopold Mozart to his wife in Salzburg, “and the amazement was all the greater as Marchese Ligniville, the director of music, who is the finest expert in counterpoint in the whole of Italy, placed the most difficult fugues before Wolfgang and gave him the most difficult themes, which he played off and worked out as easily as one eats a piece of bread. Nardini, that excellent violinist, accompanied him.”37

Fig. 11. Title page of Eugenio di Ligniville’s canonic Stabat Mater in an edition dedicated to Pietro Leopoldo. Ricasoli Collection, Sacra 47

When the duke and duchess of Gloucester visited Florence in April 1772 Pietro Leopoldo took them to the opera. On the the following day the grand duke invited them to a concert at court, in which some of his finest musicians took part. The Gazzetta toscana described the concert proudly as a “grand academy of music, wherein the renowned amateurs Sig. Ottavio

position only in October 1768, it is likely that this edition was published later than the one mentioned by GT in April 1767. 37 Leopold Mozart to his wife, Mozart: Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, ed. Wilhelm A. Bauer, Otto Erich Deutsch, and Joseph Heinz Eibl, 7 vols., Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1962–75, I, 331; translated by Emily Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 3rd edition, New York: Norton, 1985, 125. Mozart received a generous fee of Lire 333.6.8 for his performance at Pietro Leopoldo’s villa of Poggio Imperiale; see Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart: Die Dokumente seines Lebens, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1961

21

Guarazzi and Signora Angiola Branchi and the celebrated professionals Manzoli, Guarducci, and Veroli sang several arias; also performed were some concertos for the violin by the celebrated Sig. Pietro Nardini, for the transverse flute by Sig. Dotel, and for the cello by Sig. Piantanida.”

Such occasions were not rare in Florence. Pietro Leopoldo’s singers and instrumentalists constituted was one of the chief ornaments of his court, a worthy musical counterpart to the grand-ducal treasury of the visual arts, the Uffizi; no wonder he was eager to show it off to foreign dignitaries. This ensemble of exceptional musicians gave Tuscan music a focus; it set standards of virtuosity and creativity. By attacting such musicians to Tuscany, by convincing them to stay there and serve him, and by assembling them into a finely tuned ensemble, Pietro Leopold set his personal stamp on music life in the capital. Church Music The grand duke expressed interest in church music through his patronage of Carl’ Antonio Campion, for many years his maestro di cappella (Fig. 12). Like Ligniville, Campion was a native of Lorraine. Born in Lunéville in 1720, Campion may well have come to Tuscany with the Lorrainian noblemen who formed the Regency government in 1738. He is said to have studied with Tartini. From 1752 Campion served as maestro di cappella at the cathedral of Livorno. In 1762 he was appinted maestro di cappella to the grand-ducal court in Florence, a position he kept when Pietro Leopoldo took over the government in 1765.38 As maestro di cappella Campion wrote and directed music for the court chapel, the court church of Santa Felicita, and, on special occasions, for other churches of Florence as well. The Gazzetta toscana provides us with information about some of his performances, which brought together many of Pietro Leopoldo’s virtuosi, both vocal and instrumental. Manzoli and Veroli took part in a grandiose celebration of the birth of the grand duke’s first son Francesco (later Emperor Francis II) in 1768. The service featured a Mass and Te Deum by Campion; it is described in detail in the Gazzetta toscana:

The musicians, both vocal and instrumental, who make up the staff of this royal chapel, wishing to demonstrate in public view their gratitude to the royal sovereign and to celebrate the birth of the royal first-born son, Francis Joseph, agreed to sing a solemn Te Deum and decided to do it in the Temple of Santissima Annunziata, as that which is best shaped for the harmony, and the most capable of holding the great quantity of instruments and singers... All the music was conducted by Sig. Carlo Antonio Campion, Maestro della Real Cappella, by whom it was composed with great beauty and felicity for this occasion... The Mass was sung a due cori and the Te Deum a quattro: in addition to the choir lofts at the organs [facing each other across the nave], the whole choir behind the main altar was filled with musicians, conducted by Sig. [Bartolomeo] Cherubini; the

38 On Carl’Antonio Campion (as he frequently signed his name in documents in AS, ICRL) see Constantin Floros, Carlo Antonio Campioni als Instrumentalkomponist, dissertation, University of Vienna, 1955, “Musicisti livornesi: Carlo Antonio Campioni,” in Rivista di Livorno, 1955, 134–150; Mario Fabbri and Enzo Settesoldi, “Precisioni biografiche sul musicista C. A. Campion,” in Rivista italiana di musicologia III (1968), 180–88; and John A. Rice, “Music in the Duomo during the Reign of Pietro Leopoldo I (1765-1790),” in Cantate Domino: Musica nei secoli per il Duomo di Firenze, ed. Piero Gargiulo, Florence: Edifir, 2001, 259-74. On the grand-ducal court’s production of church music during the early 1770s, when the young Luigi Cherubini was a member of the cappella, see Siegert, Cherubini in Florenz, 234–47.

22

number of singers and players exceeded 150. In addition to the voices of tenor, contralto, and bass there were four sopranos in the first chorus: Sig. Giovanni Manzuoli, Sig. Veroli (both in Royal service), Sig. Luciani, and Sig. Bianchi. Sig. Manzuoli sang the first motet and Sig. Luciani the second.39

One of Campion’s most elaborate productions of church music was the celebration of Mass at the Convent of San Domenico nel Maglio on the feastday of Saint Rosa of Lima, 30 August 1771; from the Gazzetta toscana we learn that at least four grand-ducal musicians in addition to Campion took part:

The production was the work of the distinguished Sig. Carlo Campion, Maestro di Cappella in the service of H. R. H. He himself conducted, while that most famous master of the violin Pietro Nardini directed the large orchestra. Nardini had all his fine students on one side; on the other side was Sig. Mosel with the most expert masters of the same instrument. This numerous orchestra of more than forty players, with every kind of instrument more than doubled, and including the excellent Sig. Piantanida with his cello, was joined by about twenty-four voices of the best singers; the well-known Sig. Giacomo Veroli with his student and others distinguished themselves ex tempore with various solo concertos [“cadenzas” is probably meant] that were completely new, both in the Gloria and the Credo. The liveliness and profundity appropriate to church music was communicated to the large audience of foreigners, nobility, and people. So

39 GT 1768, 51–52. Quoted in Mario Fabbri and Enzo Settesoldi, “Precisazioni biografiche sul musicista C. A. Campion,” Rivista italiana di musicologia 3 (1968), 180–88.

Fig. 12. Carolus Antonius Campion Loth[aringius] (Carl’Antonio Campion of Lorraine). Bronze medal by Giovanni Zanobio Weber. From the website Numisbids.com

23

much beautiful, majestic harmony reached its culmination in the violin concerto after the Epistle, in which the above-mentioned Sig. Pietro Nardini demonstrated the extent to which he alone possesses the command of this difficult instrument, played by him with every imaginable delicacy and unsurpassable perfection.40

When Charles Burney passed through Florence in 1770 he witnessed another spectacular performance of church music, this time a solemn mass at a convent just outside Florence. Manzoli and Veroli took part, though not apparently Campion:

It cost more than 300 zecchins. The music of the mass was composed by signor Soffi, Lucchese. There was a trio in the 1st part of it for Manzuoli, Verole, and the 2nd maestro del annunciata – Verole beat time, the composer not being present, to the chorus. The band, vocal and instrumental, was very numerous. Manzuoli sang a motet charmingly, very well composed by Monzi of Milan; with less voice, I think, even in a small church, than he had in the opera house, when in England.41

Campion’s duties at court were administrative as well as musical. He organized the professori di musica giornalieri, kept careful records of who performed at every service, and saw to it that the musicians were paid. Campion presented Count Thurn, the maggiordomo maggiore, at regular intervals a detailed listing of all musicians employed during the intervening period, their wages per service, and the total wages of all musicians. Thurn approved the payment to Campion of a lump sum, and the maestro di cappella then distributed payment to the musicians. The Gazzetta toscana evidently reflected grand-ducal sentiments with its frequent, consistently favorable comments on Campion and his music. An article about the music for Holy Week services in 1768 shows that the sovereign took a personal interest in the work of his maestro di cappella:

The divine offices, on three successive days, were celebrated in the royal chapel in the daily presence of the royal patrons . . . The music, which was sung in the church of Santa Felicita as well as in the royal chapel, is a new composition of Sig. Carlo Campion, maestro di cappella in the service of this royal court; the music, collected in a book, had been presented beforehand to His Royal Highness.42

40 Del celebre Sig. Carlo Campion Maestro di Cappella all’attual servizio di S. A. R. ne’ fu la produzione: Egli stesso la diresse, regolando insieme la copiosa orchestra il rinomatissimo Professore di violino Sig. Pietro Nardini, che da una parte aveva tutti suoi bravi allievi, dall’altra da il Sig. Mosel con i più esperti Professori di simil strumento. A questo numerosa orchestra composta da più di 40. suonatori di strumenti, e in ogni genere più che raddoppiati, frai quali col suo violoncello anche l’eccellente Sig. Piantanida, erano unite circa 24. voci dei migliori Professori nel canto; talchè l’abbastanza noto Sig. Giacomo Veroli col suo scolare, ed altri molto si distinsero coll’eseguire improvvisamente vari concerti a solo, sì nella Gloria, che nel Credo espressamente scritto di nuovo. È restata impressa nella numerosa udienza di Forestieri, Nobiltà, e Popolo la vivacità e profondità propria d’una musica di chiesa. Diede compimento a tanta armonia tutta bella, tutta maestosa, il concerto del violino dopo l’Epistola, nel quale il prelodato Sig. Pietro Nardini fece gustare fin dove in lui solo è arrivato il possesso di questo difficile istrumento suonato da esso con tutta l’immaginabile delicatezza and inarrivabile perfezione (GT 1778, 142 [article dated 4 September]). 41 Charles Burney, Music, Men and Manners in France and Italy, 1770, ed. H. Edmund Poole, London: Folio Society, 1969, repr. London: Eulenburg, 1974, 114 42 GT 1768, 67; quoted in Mario Fabbri and Enzo Settesoldi, “Precisioni,” 187.

24

In 1772 Pietro Leopoldo rewarded Campion: “Signor Carlo Antonio Campion, . . . having many times presented various works to H. R. H. our sovereign, received recently from His Royal Munificence, as a token of gratitude, a superb snuffbox of gold, filled with zecchini.”43 As a composer, a performer, and an administrator, Campion played an active role in the musical life of Florence for many years—in the course of which he enjoyed Pietro Leopoldo’s support and encouragement. A Handel Revival During the early years of his reign Pietro Leopoldo showed an interest in supporting genres and styles that may have been unfamiliar to his Tuscan subjects. He hired as his maestro di ballo the French dancer and choreographer Antoine Pitrot, one of the pioneers in the genre of heroic pantomime ballet, before that genre had become firmly established in Italy.44 He organized the performance in the Pergola of several innovative operas by Tommaso Traetta in 1768–1769.45 Yet another instance of Pietro Leopoldo’s support of a genre relatively new to Florence is his encouragement of a remarkable series of performances of Handel’s vocal music during the early years of his reign. Alexander’s Feast, Messiah, Acis and Galatea and possibly Judas Macchabeaus received what seem to have been their first performances outside the British Isles in Florence between 1768 and 1772. These performances came about largely through the musical interests of an important English resident of Florence, but they were welcomed by the grand duke, and his musicians took part in them.46 The eccentric English expatriot George Nassau Clavering, Third Early Cowper (1738–1789) was one of the richest residents of Florence (Fig. 13). And he was generous: a collector of paintings and patron of poets and scientists as well as musicians. Within a few months of Pietro Leopoldo’s arrival in Florence, Cowper had established close ties with the grand duke. It was rumored that his beautiful young English wife, whom he married in 1775, was one of the grand duke’s mistresses; but even before his marriage Cowper wielded considerable influence at court, influence extending to musical matters. Cowper had several of Handel’s works performed at his Florentine villa. The Gazzetta toscana had nothing but praise for the first of his Handel programs, a performance of Alexander’s Feast in Italian translation on 21 April 1768; less than a week later it was repeated, at Pietro Leopoldo’s request, at the Pitti Palace. The performances were directed by Salvador Pazzaglia, Cowper’s music director. According to the Gazzetta toscana, “the cantata earned the satisfaction of both Their Royal Highnesses.”47

43 GT 1773, 99; quoted in Mario Fabbri and Enzo Settesoldi, “Precisioni,” 187–88. 44 Rice, Emperor and Impresario, 187–203; Weaver and Weaver, 1751–1800, 46–49. 45 Rice, Emperor and Impresario, 22–32; De Angelis, La felicità, 74–78; Siegert, Cherubini in Florenz, 149–55. 46 The Florentine Handel revival is discussed in greater detail, with reference to the secondary literature on the subject, in John A. Rice, “An Early Handel Revival in Florence,” in Early Music XVIII (1990), 26–71. 47 GT 1768, 79, 83.

25

The approval of the grand duke and duchess would have led Florentines to suspect that further performances of Handel’s music were forthcoming. In August 1768 they could read in the Gazzetta toscana that Cowper had procured more of Handel’s works from England, including Messiah. That oratorio was performed, again in Italian, in August 1768. Pazzaglia conducted a chorus and orchestra that together numbered about forty musicians. Cowper dedicated the printed libretto to Pietro Leopoldo, “who, as a sign of his approval, wished, on Saturday last, to hear this production at the Regio Palazzo de’ Pitti, with the same number of musicians as was needed at the rehearsal.”48 Payment records in the Archivio di Stato in Florence (Appendix 3) show that precisely forty musicians took part in the performance at court, in addition to the conductor Pazzaglia: three vocal soloists, a chorus of sixteen (four on a part), nine violins, two violas, one cello, two double basses, two oboes, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and organ. The soloists included a singer who was to have a significant role in the history of opera: the baritone Francesco Bussani, who more than twenty years later created the role of Don Alfonso in Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Cowper had Alexander’s Feast performed again in October, and several more performances of Il convito di Alessandro and Il Messia were given during 1769 and 1770—some at court, and some under the auspices of the accademie, societies of Florentine music lovers. The 48 GT 1768, 141.

Fig. 13. George Nassau Clavering, Third Early Cowper, with Florence in the distance. Portrait by Johann Zoffany

26

performance of Il convito di Alessandro at the Pitti Palace on 18 August 1769 was much less lavish than that of Messiah described above: only twenty-five musicians took part, again including Bussani (Appendix 4). Tommaso Guarducci took part in a performance of Il Messia at one of these concerts, on 8 April 1770; but for the most part Pietro Leopoldo’s vocal virtuosi were absent from the Handel revival.

One of the Florentine musicians who might be expected to have taken a particular interest in Handel’s music was the contrapuntally minded Marchese di Ligniville. The Gazzetta toscana reported the performance of Messiah and Alexander’s Feast in Ligniville’s palace during March 1772, with the participation of Manzoli and Veroli. The following month Acis and Galatea was performed in “a magnificent and sumptuous academy of vocal and instrumental music, honored by the royal presence of our sovereigns,” which featured the performance of “a superb cantata... set to music by the famous Hendel.”49

The performances organized by Ligniville were the last major public manifestations of Florentine enthusiasm for Handel’s vocal music during Pietro Leopoldo’s reign. But Handel may have continued to interest music lovers in Tuscany. The Ricasoli Collection includes manuscripts of several of his works, mainly oratorios and related genres, including full scores of Alexander’s Feast (Fig. 14) and Judas Maccabaeus and an incomplete set of orchestral parts for Messiah. The presence in the Ricasoli Collection of much of the music performed during the Florentine Handel revival of 1768–1772 suggests that the revival led to a long-lasting appreciation of Handel’s choral music in Florence, and perhaps to further, less publicized performances of Handel’s music in the palaces of the Ricasoli and other Tuscan music lovers.

49 GT 1772, 50, 57.

Fig. 14. Title page of a manuscript full score of Handel’s Alexander’s Feast in Italian translation. Ricasoli Collection, Profana 90

27

Music Teachers for the Grand-Ducal Family A family portrait attributed to Johann Ulrich Moll, painted about 1781, shows Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo and his wife Maria Luisa surrounded by their many children (Fig. 15). Through the open window we see the Duomo of Florence; the setting is probably a room in the Pitti Palace. In front of the window stands Pietro Leopoldo’s oldest son, Francesco, who would later succeed his father as emperor in Vienna. Francesco, like many of his siblings, was a musician, a violinist. At the keyboard of what is probably a square piano is the oldest of the archduchesses, Maria Theresa, one of the most talented of the grand-ducal children; she is apparently the only one to whom Florentine musicians dedicated compositions. Not in the picture, because he was born only in 1788, is Pietro Leopoldo’s last born son, Rodolfo, who eventually became the archbishop of Olmütz, in what is now the Czech Republic. As Archduke Rudolph he begame a good pianist and composer, and the most important musical patron of all of Pietro Leopoldo’s children: he studied with Beethoven, who dedicated to him, among other works, the Archduke Trio and the Hammerklavier Sonata, and who originally planned the Missa Solemnis to celebrate his royal patron’s ordination as archbishop. Pietro Leopoldo, following Habsburg tradition, obviously gave his children sound musical training. This training represented for the grand duke yet another avenue of musical patronage, which must have been eagerly sought by Tuscan musicians. Those hired to teach the archdukes and duchesses enjoyed not only a stable income but also the prestige of being closely associated with the court.

Fig. 15. Pietro Leopoldo and his family, as depicted around 1781, possibly by Johann Ullrich Moll

28

One of these musicians was Salvador Pazzagia, who published his Sei sonate da cimbalo per il piano, e forte coll’accompagnamento del violino in 1780. The Ricasoli Collection includes two copies of this set (Profana 153a and 153b). On the handsome title page (Fig. 16) Pazzaglia identified himself “maestro di musica della Real Famiglia di Toscana” and dedicated the sonatas to Archduches Maria Teresa. Pietro Leopoldo’s growing family needed more than one teacher, and in 1783 Pazzaglia was joined by Filippo Maria Gherardeschi, a prolific Tuscan composer of music for church, theater, and chamber. Gherardeschi dedicated his Tre sonate per cembalo o fortepiano, which he published in Florence in 1785, to Archduchess Maria Teresa.50 One of these sonatas can be found in the Ricasoli Collection. A manuscript Sonata per cembalo del Sig. Filippo Gherardeschi (Profana 69) also appears, heavily revised, as the first of the Tre sonate of 1785. The work opens with an Andante grazioso in C major (Fig. 17). Above an Alberti bass Gherardeschi spins a lyrical melody characterized by dotted rhythms and syncopations. This is a good composition for teaching. Graceful and simple, it could have been played to charming effect by the young archduchess Maria Teresa.

Fig. 16. Salvador Pazzaglia’s Sei sonate da cimbalo per il piano, e forte, dedicated to Pietro Leopoldo’s eldest daughter. Ricasoli Collection, Profana 153b

50 The publication of Gherardeschi’s Tre sonate was announced in GT 1785, 140 (27 August). On Gherardeschi see Stefano Barandoni, Filippo Maria Gherardeschi (1738–1808): Musicista “abile e di genio” nel Granducato di Toscana, Pisa: Edizioni ETS, 2001 (the Tre sonate discussed on pp. 138–40).

29

Fig. 17. Filippo Gherardeschi, Sonata per cembalo. Ricasoli Collection, Profana 69 Tuscan Pianos and Piano Building Both Filippo Gherardeschi and Salvador Pazzaglia wrote piano music for their grand-ducal patrons. They were not the only late eighteenth-century musicians in Tuscany who wrote music with titles that explicitly associate it with the piano. Beginning in 1784 Vincenzio Panerai, “professor di cimbalo e d’organo, maestro di cappella e di musica fiorentino,” published a series of twenty-four sonatas, most of them written specifically for cimbalo a piano-forte; many of them have parts for other instruments as well. The Ricasoli Collection includes one of these sonatas, for piano six hands (Profana 152, Fig. 18). All this piano music suggests that Florence was emerging during Pietro Leopoldo’s reign, almost a century after Cristofori invented the instrument there, as one of the earliest major Italian centers of piano composition and performance.

30

Fig. 18. Vincenzio Panerai, Suonata XXIII. in rondò a sei mani per cimbalo a piano-forte. Ricasoli Collection, Profana 152

The grand-ducal court played a role in this development. The dedication to Archduchess Maria Teresa of works that require the piano (Pazzaglia’s Sei sonate da cimbalo per il piano e forte) lead one to suspect that the court favored the piano over the harpsichord, a suspicion confirmed by Pietro Leopoldo’s patronage of Tuscan piano builders. In an article dated Pisa, 11 August 1784, the Gazzetta toscana praised the piano maker Giuseppe Zannetti and reported that Pietro Leopoldo had bought an instrument from him: “Our most clement sovereign, protector of the noble arts, deigned to buy one two years ago, and it has fully satisfied every expectation.”51 Zannetti was not the only Tuscan piano builder patronized by the grand duke. An article in the Gazzetta toscana dated 27 November 1784 describes another piano, this one built by the Florentine maker Francesco Spighi on commission from the grand duke and duchess.52 These articles should not be taken to mean that the piano completely superceded the harpsichord during Pietro Leopoldo’s reign. Harpsichords continued to be built in Florence into the 1790s. One of the busiest builders of keyboard instruments in Florence during the late eighteenth century was Vincenzio Sodi. A beautifully decorated single-manual harpsichord built by Sodi in 1791 or 1792 can be admired in Luigi Tagliavini’s collection of keyboard instruments

51 GT 1784, 131–32, quoted in Mario Fabbri, “Francesco Zannetti, musicista volterrano ‘dell’estro divino,’” in Chigiana 19 (1962), 161–82. 52 GT 1784, 190 (27 November).

31

(Fig. 19).53 But by patronizing Tuscan piano builders and by hiring for his children’s education teachers who composed music specifically for the piano, Pietro Leopoldo contributed to an interest in the piano and in piano music among Florentine composers and music lovers—interest clearly evident in the Ricasoli Collection’s rich holdings in late eighteenth-century Tuscan piano music.54

Fig. 19. A harpsichord by built by Vincenzio Sodi between 1791 and 1792

The 1780s: A Decade of Regulation and Centralization From near the beginning of his reign, Pietro Leopoldo showed an interest in wide-ranging governmental reform. Inspired not only by the reforms begun by his mother in Vienna and continued by his brother Joseph, but also by the progressive ideas of Tuscan government officials, he set to work streamlining the bureaucracy and moving Tuscany toward a free-market economy. In 1786 he promulgated a new criminal code that abolished torture and the death penalty, a document admired by enlightened statesmen and intellectuals in many parts of Europe. Perhaps most important was an idea so radical that it never came to fruition. Beginning in 1779 53 Maria Virginia Rolfo, Vincenzio Sodi: Life and Work, MM thesis, University of South Dakota, 2011; and Clavicembali e spinette dal XVI al XIX secolo: Collezione L. F. Tagliavini, ed. Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini and John Henry van der Meer, Bologna: Grafis, 1987, 23–4, 114–121. 54 For a more detailed discussion of this point, see John A. Rice, “The Tuscan Piano in the 1780s: some builders, composers and performers,” Early Music XXI (1993), 4–26.

32

he and his minister Francesco Maria Gianni created a written constitution for the government of Tuscany. Although it was not put into effect, the very fact that Pietro Leopoldo conceived of such a thing testifies to his ambition to systematize and rationalize every aspect of government.55 Around the same time as Pietro Leopoldo began to work on the constitution, his passion for systematization began to affect musical life in Tuscany. After fifteen years in which he seems to have been satisfied with the theatrical regulations promulgated by the Regency, he issued a series of decrees from 1779 to the mid 1780s that confirmed and extended grand-ducal control over the theaters. In his Relazioni sul governo della Toscana, a voluminous description of Tuscany and its government compiled by Pietro Leopoldo at the end of his reign as a guide for his successor, the grand duke summarized the contents of his theatrical legislation and explained his reasons for devoting so much effort to it during the last decade of his reign. His personality comes through these words: his is an enlightened despot, moralistically regulating the lives of his subjects for their own good, down to the smallest detail, whether they like it or not:

The Tuscans are extremely fond of theaters and masking. Masks were previously permitted throughout the fall and Carnival, from the Christmas feast days until Lent. But the excessive dissipation to which they gave rise, and the facility and incentive they gained for dissolute behavior—owing to the custom that during the masking the theaters and galleries are in darkness, and owing to the almost general use of the bautta, a most difficult disguise to penetrate, which aids greatly in dissolute behavior—obliged the government to suppress them in the fall and not to permit them at Carnival except from the Sunday of Septuagesima on, excluding Sundays and high holidays. This time is sufficient, and it is necessary that the government not allow itself to be persuaded to increase it or prolong it, notwithstanding the many pressures that will be brought to bear, since nothing but trouble will result.

There was on the occasion of Carnival an excessive number of theaters both in Florence and in the surrounding country and in the smaller cities and territories of the grand duchy. In these theaters the actors were either local people, who wasted much time in preparing the plays, and ignored their affairs, or professional actors, mostly people without ethics or religion, or Tuscany actors, who were mostly vagabonds or bad women, who, unable to support themselves in their meager earnings, introduced to the countryside all the vices of the large cities.

It was therefore decreed, after these problems were analyzed, that masking be abolished in all of Tuscany, except in Florence, Siena, Pisa, and Livorno, since in the smaller cities it gives rise to nothing but quarrels, arguments, and disruptions; that in Florence there should remain open five theaters only, fixing for the same the time of their opening, except in Carnival, when all were permitted to be open; that, except for Pisa, Siena, and Livorno, where only one theater was to be open, in all other cities the theater was not to open except in Carnival, with comedies in prose without ballets; and that except for the cities to which the privilege had been granted, in all other places the theaters had to be destroyed and no spectacle was permitted. Companies of foreign actors were prohibited, and it was established that the impresarios of the theater, before the opening of the same, must submit to the Presidente del Buon Governo [i.e. the minister of police] the list of subjects chosen, both for spoken plays and ballets, from which are excluded all subjects whose performance had previously caused complaints in various parts of Tuscany. These provisions relative to spectacles and theaters produced an excellent effect and it is essential to