Isabella D'Este's Evolution of Art Patronage - Digital Commons ...

Clientelism and Patronage in Indian Elections: A study of 2009 Lok Sabha elections

Transcript of Clientelism and Patronage in Indian Elections: A study of 2009 Lok Sabha elections

Clientelism and Patronage in Indian Elections: A study of the 2009 Lok Sabha Election1

Sarthak Bagchi

Doctoral Fellow, Department of South Asia

Leiden University Institute for Area Studies

Rough Draft for the 7th Annual Nordic NIAS Council Conference at the University of Southern

Denmark, Sonderborg Campus, November 4-6, 2013.

Abstract

The gamut of studies on client-patron relationships has always defined it as a dyadic,

hierarchical, vertical and asymmetrical mode of “exchange” between a voter and a politician

involving the recurring transfer of tangible material benefits from the politician to the voter

in return for a continuous electoral support. Any clientelistic exchange from the western

point of view has always been an exploitative one where the rich political class exploits the

poor and vulnerable voters. However in the Indian democratic context, a typical clientelistic

relationship shows a lot of transformations making it more horizontal and symmetrical in

nature with a lot of bargaining power going to the voters. Due to these transformations

clientelistic politics are often mistaken as programmatic/populist politics and vice-versa. This

paper suggests on a working definition of clientelism which helps in drawing certain

boundaries to clientelistic relationships, based on the exclusionary factor in such relations.

The paper further examines the Lok Sabha elections of 2009 to find out the types of voters

(based on a variety of social indices) which indulge in such clientelistic exchanges in India

and probably seeks to move away from the western notion of an ‘exploitative’ clientelistic

exchange relationship.

1 This paper is a working paper, based on my M.Phil thesis, which deals with some secondary level

data analysis to understand clientelism and patronage in Indian Elections. I wish to thank my supervisor Prof. K. C. Suri, Department of Political Science, University of Hyderabad, for initiating me into research on clientelism and introducing me to quantitative research methods in Political Science. I also wish to thank Mr. Sanjay Kumar and his team at lokniti, Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi for giving me access to their datasets and also patiently helping me in my quantitative analysis.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

2

“the essence of all competitive politics is bribery of the electorate by politicians... the

farmer who supports a candidate committed to high support prices, the businessman who

supports an advocate of low corporation taxes, or the consumer who votes for candidates

opposed to a sales tax...”

- Robert Dahl, 1959, A Preface to Democratic Theory

Robert Dahl, one of the leading scholars on democratic theory and institutions, had said

these lines hinting towards the multiple agents and multiple ways by which politicians tend

to secure votes from a selected group or class of voters. It is perhaps, these multiple forms

in which clientelism exists and functions within a democratic setup that makes this area, an

interesting one to probe in political science. A client-patron relationship, when defined

generally, is shown as a hierarchical, asymmetrical mode of “exchange” between a principal

(voter) and an agent (politician) involving the recurring transfer of tangible material benefits

from the agent to the principal in return for a continuous electoral support (Kitschelt and

Wilkinson, 2007. pp.7). This simple reciprocal exchange relationship between those who can

deliver the resources and those who can deliver their support in return of these resources

has been the focal point of many studies not only in political science but even in

anthropology and sociology. In fact, the whole gamut of patron-client linkages, reflects, as

James Scott suggests, an attempt on the part of the anthropologists to come to grips with

the mosaic of non primordial divisions (Scott, 1972. pp.92). In this paper I will try to arrive at

a working definition of clientelism with reference to the democratic context within which it

is practiced in India. In pursuit of this working definition, I start of by defining clientelism

generally in the first section. The second section traces the historical development of

clientelism in the realm of studies in political science. The third section follows up this

development in the Indian context and shows the changes, clientelism has accrued over the

years as it is practiced in India. In the fourth section I formulate some hypotheses, based on

the global literature of clientelism and test them in the Indian context to arrive at certain

clarity about the way in which clientelism is practiced in India. The final section is the

concluding one, in which I also pose certain questions worth probing in the future.

I. What is clientelism? Some definitions.

In his work, ‘Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia’, 1972, James Scott

defines a “patron-client relationship – an exchange relationship between roles – as a special

case of dyadic (two – person) ties involving a largely instrumental friendship in which an

individual of higher socioeconomic status (patron) uses his influence and resources to

provide protection or benefits, or both, for a person of lower status (Client) who, for his

part, reciprocates by offering general support and assistance, including personal services, to

the patron” (Scott, 1972). A key characteristic of any clientelistic relation is its distributive

aspect, which becomes clear with Javier Auyero's definition of clientelism as, “the

distribution of resources (or promise of) by political office holders or political candidates in

exchange for political support, primarily – although not exclusively – in the form of vote”

(Auyero, 1999. pp. 297). The characteristic features on the basis of which clientelism is

defined can be identified as – Hierarchical arrangements, bonds of dependence and control,

highly selective, particularistic, material exchange, highly individualistic, a cluster of bonds of

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

3

dominance, a realm of submission, informal though tightly binding and understanding and

lastly as a mechanism of domination and as a strategy of electoral mobilization (see, Auyero,

1999; Scott 1972, Kitschelt and Wilkinson, 2007; Schaffer, 2007; Berenschot, 2011; Escobar,

2002; Chubb, 1982; Keefer and Vlaicu, 2005; Ippolito-O’Donnell, 2006; Hopkin, 2006,

Kettering, 1988; Wantchekon, 2003).

Clientelism, in short, may be viewed as a more or less personalized, affective, and reciprocal

relationship between actors, or sets of actors, commanding unequal resources and involving

mutually beneficial transactions that have political ramifications beyond the immediate

sphere of dyadic relationships” (Lemarchand and Legg, 1972). Wantchekon, from his field

experiments in Africa has shown that the positive response to clientelist appeals by regional

or ethnic candidates may indicate that ethnic solidarities can help enforce clientelist

bargains (Wantchekon, 2003). Similarly, Kanchan Chandra while studying the ethnic

mobilisation of patronage politics in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh has found out

that in patronage redistribution scenarios, one-one interactions are necessary and vital but

on a group level and not on a personal level. She suggests that, “By joining a group, the

voters magnify the value of her vote….. a number of individuals organized as a group can

bargain more effectively with candidates than the same number of individuals voting

individually….. Joining a group allows individual members to increase the odds that they or

the micro-communities that they represent will receive greater priority in the allocation of

benefits than individuals who are outside the group.” (Chandra, 2004: 55).

These contrary findings regarding the characteristics of clientelism show the diverse types in

which clientelism exists and operates in different parts of the world. It is due to these spatial

and societal modifications like that between Latin America, Africa and India for example that

it becomes an interesting area of research in comparative politics.

II. Historical Development of Clientelism

To understand any modern phenomenon in its totality, it becomes necessary to understand

it in its emergence. The patron-client relations are not a new development in modern

political societies but have been found to have existed in early chiefdoms, in ancient city-

states and empires, in feudal systems, in western and Third World democracies, in military

dictatorships, and in modern socialist states (Lande, 1983). Quoting authors like Critchley,

Carl H. Lande showed that “patron-client relationships were important throughout European

history, appearing in unbroken succession in the forms of Roman clientage, early Germanic

warrior - followship, and medieval vassalage and serfdom. There is ample evidence of the

importance of patron-client relationships during later phases of European history, although

they appeared in somewhat different institutional settings.” (Lande, 1983; 444). In political

science literature, research on patron-client relationship has been largely seen through the

prism of political clientelism2, which can be defined as a pillar of oligarchic domination that

reinforces and perpetuates the role of traditional political elites.

2 I am using clientelism and political clientelism interchangeably since this thesis deals with the

political implications of clientelistic relations, although I am not discounting the economic and social

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

4

The basic difference between a patron-client relation and any other traditional coercive

bond is the reciprocity factor, which not only determines but also defines this relation.

James Scott points out the power imbalance between the patron and the client, and how

the client enters into an unequal exchange relation, in which he is unable to reciprocate

fully. The power imbalance exists because of the patron’s ability to supply goods and

services which the client and his family need for their survival and well being. This power

imbalance often binds the client with a debt of obligation and makes it easy for the patron

to enjoy compliance of the client, which is another important feature of a patron – client

relation. The greater the imbalance between the client and the patron, the greater will be

the compliance of the client (Scott, 1972).

Two more characteristic features of a patron-client relation as per Scott are daily face-to-

face interaction between the patron and the client and the diffuseness in the relation, which

helps it succeed as long as both have something to offer to each other. In fact the very

affective nature of such a relationship owes it a legitimacy that is denied to other power

relationships of a coercive nature. Even in traditional patron-client relations, the client can

look for a more promising leader who can deliver better goods, than his existing patron. This

is exactly where modern patron-client relations seek a conjuncture with the traditional ones.

In modern clientelistic exchanges, the drive of clients to shift to the aegis of a better patron

is credited to the initiation of democracy in such societies. Democracy, or competitive

electoral politics, to be more precise, has improved the client’s bargaining position with a

patron by adding to his resources by increasing the number of prospective patrons that a

client can choose from (Scott, 1972. pp. 109). Scholars like Martin Shefter and Simona

Piattoni believe that democracy undercuts clientelism by giving more bargaining power to

the voters as compared to the politicians, who might not see clientelism anymore as an

effective vote mobilizing strategy in a secret ballot system (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, 2007.

pp.4-5).

The legal and institutional nature of the democratic system turns clientelism into a shameful

aspect of the informal sector (Chavez and Stoller, 2002). Clientelism, for a long time was

assumed to be a vestige of early modern development and it was believed that political and

economic modernization would render it obsolete and ultimately end it (Roniger, 2004).

However, as is quite evident, clientelism is still functioning in almost all parts of the world,

although with different degrees, with different types, at different levels and with different

meanings. In fact in countries like the United States of America and the United Kingdom,

where bribery is prohibited in the election (vote-buying) according to their respective

constitutions, clientelism in the form of pork-barrelling and patronage was popular in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth century in the absence of coherent implementation of

programmatic policies (Kuo, 2011). In fact, research now suggests that in both of these

advanced democracies clientelistic practices like pork-barrelling and patronage actually

created institutional legacies favourable to the emergence of programmatic politics (Kuo,

2011: 13). This progressive evolution of clientelistic politics from pork-barrelling and

implications, however still, only from the standpoint of probing the politics behind clientelism, I refer to clientelism as political clientelism.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

5

patronage giving rise to programmatic politics can also be viewed as a reason for the

legalizing of interest-group politics and lobbying3 in such advanced democracies.

It is believed that widespread clientelism in Latin American democracies inhibits the

potential power of organized popular groups under new political rules and frustrates the

promise of institutional change (Escobar, 2002). One major debate ensuing from the study of

clientelism in Latin America is, as Susan Stokes point out, ‘whether poverty gives rise to

clientelism or does clientelism gives rise to poverty?’ (Stokes, 2007). This question has its

origins in the belief that parties in Latin American countries like Argentina, Brazil and Mexico

traditionally try to woo poor voters by giving them cheap monitory benefits or other tangible

private goods, which holds higher value for them as compared to other relatively well-off

voters (Brusco et. all, 2004, Desposato 2007 and Fox, 1994). However, over the course of

time, traditional ideas of a dominating authoritarian clientelistic relation of subordination in

Latin American countries has now given way to more evolved forms of clientelism like semi-

clientelism and distributive clientelism4 (Fox, 1994 and Rubio, 1997). This kind of semi-

clientelism enable poor people in Mexico to gain access to whatever material resources the

state has to offer without having to forfeit their right to articulate their interests

autonomously (Fox, 1994).

Since clientelistic domination depends on strong, everyday, face-to-face interactions, it has

limitations in terms of massive vote-getting capacity (Auyero, 1999). In today's republican

societies, based on electoral systems and the separation of powers, clientelism no longer has

a formal institutional character. But as is evident from the above examples, it maintains its

currency through new, ever more subtle informal forms depending on the level of

development of the economic and political system. Clientelism, as it is known today has

many different versions like, Allocational policies, pork-barrel spending, traditional

patronage and vote buying etc. (Schaffer, 2007.pp.5). However the underlying goal of all

these different versions of clientelism is similar in nature, that is, to provide tangible

material benefits to the voter or a select group of voters in order to attain electoral support.

While allocational policies and pork-barrel spending are targeted towards a particular class

of voters and communities in general, patronage and vote buying deals with clientelism at a

more individual level (ibid.)

3 The debate on whether lobbying should also fall under clientelistic politics is an ensuing one, but

unfortunately out of the scope of this paper. Primarily due to the legally legitimate status accorded to it and I am dealing with clientelistic practices which are deemed illegal and negative in nature. 4 Bianca Rubio makes a distinction between distributive clientelism, which she calls ‘inclusionary’ and

an extractive clientelism, which she calls ‘exclusionary’. She describes exclusionary clientelism as one which relies more heavily on constraints tending to be overwhelmingly based on the discretionary enforcement of the law. Patrons in exclusionary clientelism depend on their power to provide clients with selective exemptions from law enforcement in exchange for both political subordination and for material contribution like bribes and other pay offs (Rubio, 1997). For further distinctions between these two types of clientelism, refer to ‘ Rubio, Blanca, 1997. Clientelism in Flux: Democratization and Interest Intermediation in Contemporary Mexico. Mexico.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

6

III. Development of Clientelism in India

The extent to which such clientelist structures have penetrated electoral politics in India can

be viewed at two levels, firstly at the vote buying level (candidate centric) and secondly at

the local intermediary or party patronage level. Scholars like Ward Berenschot through their

field research have shown that not all exchanges between politicians and voters are unequal

and exploitative as the patron-client relationship in older literature suggests (Berenschot,

2011). Similarly ethnographic accounts of Aril Ruud suggests that though politics and

patronage politics specifically, is seen to be a ‘nungra’ or dirty thing in rural West Bengal,

people still prefer to maintain strategic ties with the local level leaders and politicians in

order to extract benefits from state resources and get both group as well as individual

benefits from time to time (Ruud, 2009. pp. 122). This shows that though the voters might

be sceptical about the moral character of the local politician, but they still don’t have any

reticence as long as the politician exhibits his capacity to deliver. Studies on clientelism in

local level politics have shown that, for long term stability, a government has to mix

clientelistic politics with the delivery of welfare benefits from programmatic policies to the

voters like the Left Front government did in West Bengal during its more than three decades

of rule (Bardhan, et al. 2009). Scholars like Carolyn Elliot, on the other hand believe that in

democratic polities like India there has been a gradual shift from clientelism to

programmatic welfare policies (Elliot, 2011).

The modern democratic settings in India, like many other developing countries have given

certain rights to the clients, which has increased their reciprocity in a patron-client relation,

and shifted the bargain in their favour. The democratization has dented the capacity of a

patron to command compliance by diktat and coercion. Clientelism as practiced in the

everyday politics in India indicates away from coercion and diktat that characterizes the

western notion of a traditional relationship to a linkage that is built on persuasion and driven

by inducements and incentives. Overt dependence of clients on their patrons for day-to-day

needs has metamorphosed unequal coercive bonds of domination over the period of time

into more reciprocal familial ties, where a client/voter no longer feels obligated to support

his patron, but does so out of unquestioning gratitude.

One of the most wide-spread modes of a clientelistic exchange being used in India,

especially during the elections is that of vote buying, which is immediate payment of cash or

other material benefits in exchange of votes, often a day or so before the elections (Schaffer,

2007). Scholars like Susan Stokes find vote buying to be undemocratic in nature since vote

buying allows politicians and governments to ignore the interests of the poor people, frees

them from being accountable, undermines the autonomy of the vote sellers and also

reduces the chances of vote sellers to participate in collective deliberations, which is an

important aspect of democracy, thereby hindering in the smooth functioning of democracy

(Stokes, 2007). Vote buying according to stokes, also induces people to choose immediate

small time private gains in the form of material payments in exchange of votes over the

latent but better and larger public goods under a programmatic policy. Susan Stokes in her

discussion on clientelism formulates the notion of a ‘Perverse Accountability’, which a

clientelistic exchange relation gives rise to (ibid.). The extensive social networking that a

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

7

politician needs in order to maintain the smooth functioning of his/her clientelistic network,

results in the accumulation of information regarding the voting patterns of the members of

such a network. Stokes suggests that based on this information then, the party/candidate

can hold a voter accountable for his/her vote by either punishing/rewarding him/her for it

(ibid.). This type of reverse accountability is termed 'perverse accountability' by Stokes.

Instead of the voters holding a politician accountable for his/her actions, clientelism enables

the parties or candidates to hold voters accountable for their actions, turning the very idea

of democracy on its head.

However, in an electoral democracy like India, with a secret ballot system, where every

voter can keep his vote a secret, monitoring compliance on the part of the politicians

becomes a problematic area. Though booth observers and rural voting trends can be used as

a tool in that effect, but the accuracy of such tools is highly debatable. Thus, for a politician

who hands out money to the voters with the expectation that they will vote for him, there

exist no full proof chance of him securing their votes. Such a situation is alarmingly close to

the chances of a politician hoping to secure votes through the promise of a programmatic

policy before elections.

A criticism for vote buying is attributed to the fact that the practice of buying votes invites

people to vote out of a concern for their own economic well-being rather than the public

good. Scholars like Kitschelt and wantchekon also suggest that the immediate monetary

payoff offered in vote buying often leads poor voters to discount long term policies for a

stable economic growth (Brusco, Nazareno and Stokes, 2004).

The inter-subjective barrier arises due to the various interpretations related to vote buying

which occurs with variation in culture and society. These various interpretations are also one

of the main reasons for the difficulties arising in curbing the practice of vote buying. There

exist instances of voters taking the payment made while vote buying as either a gift, or as a

reparation or compensation for all the wrongs done by the government thereby making it a

matter of right for the poor, as a threat to compulsorily vote, as a sign of virtue, generosity

and kindness, as a sign of vice and even as a sign of strength which only shows that the

candidate spending so much just before an election is confident of his win influencing voters

to align their support with the strong, confident candidate and of course squeezing some

tangible benefit in the process by receiving payments from him (Schaffer and Schedler,

2007). Arguments might even be raised over the effect immediate cash payment has over

the rationality of voters. However, with almost all candidates in an election fray nowadays

offering some or the other form of direct payment, making such offers a common factor

instead of an exceptional occurrence, the voters’ rationality hardly gets affected.

Expenditure in vote buying during elections can thus be seen as becoming a necessary

condition to contest in the elections, if not a sufficient condition to win. Looking at the

problem from a vantage point, might give us a double faceted view. While on the one hand,

the practice of handing out cash to voters might act as a motivation for them to vote (if one

discounts negative vote buying from the equation here), thereby increasing participation,

one of the two conditions put forward by Robert Dahl for the deepening of democracy.

However, on the other hand, the rising costs of campaign expenditure, which also includes

the cost of buying votes, can act as an impediment for newcomers to enter the electoral

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

8

race, creating an invisible yet rigid entry barrier, which ultimately paves way for the

incumbents to stay in power, as they are better placed to channel the required resources.

This in effect, fails Dahl’s second condition for the deepening of democracy, participation

(Dahl, 1971).

Patronage through mediation or brokerage at the local level is another popular method of

clientelistic exchange between the principal and agent in India. This mainly includes the

‘naya netas’, who represent their constituencies outwards and the state inwards, operating

with a mix of traditional patronage as well as pork-barrel spending (Krishna, 2007). This type

of a working apparatus makes for an interesting study to see how these ‘naya netas’ at the

local level leadership in different parties operate within the framework of clientelistic

linkages in order to dole out the benefits of programmatic policies to their constituencies.

‘Naya netas’ or political fixers are a prominent feature of India’ democracy as they act as the

facilitators of clientelistic exchanges between voters and politicians. Ward Berenschot

defines political fixers as, ‘intermediaries who use political contacts and knowledge of

official procedures to facilitate the interaction between citizens and state institutions’

(Berenschot, 2011. pp. 382). Political fixers often act as the lubricants in the democratic

functioning, by channelling the demands of the citizens to often unresponsive state

institutions on one hand and supplying government officials with the necessary information

to implement policies and to uphold regulations on the other (Ibid.). This two way

interaction makes them indispensable for both power-holders and citizens. Political fixers

most of the times, tend to belong to one party or the other. This explains the strong

emerging trends of party-based clientelism. Thomas Markussen in his empirical studies,

shows that in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, members belonging to the patron’s party are more

likely to benefit from an important poverty alleviation scheme and that this discrimination is

more effective than other forms of discrimination, such as discrimination based on shared

language, religion, caste or place of living (Markussen, 2010). As Joop De Wit and Erhard

Berner suggest, ‘a patronage mediated through such political fixers might be a more

attractive avenue to gain access to state resources for poorer citizens than the more ‘civic’

forms of collective action, because demonstrations, rallies or letter writing are time

consuming and often perceived to be less effective (Ibid.). With the changing times, the type

of people playing this mediator or fixer has also changed. From the earlier traditional upper

caste, landowning local power-holder, political fixers are now coming from the lower caste

but educated young men, who become popular on the basis of their capacity to deliver.

Anirudh Krishna puts it as, ‘Relative effectiveness more than ease of access determines why

villagers prefer to consult one type of local leader in far greater numbers’ (Krishna, 2007.

pp.143).

Voters find the mediation of political fixers in gaining a water/electricity connection, a

college admission or a hospital bed, much more alluring and tangible prospect than the

more abstract long-term benefits that reservation or educational policies might bring

(Berenschot, 2011). Empirical studies are now showing that the ties of dependence on the

political fixer are now slowly changing into bonds of trust and familial orientations, bringing

a new solidarity in client-fixer relations.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

9

We can now see that in India, while on one hand the overt dependence of the voters on

‘naya netas’ and vice-versa. An increase in the daily interface between the two has made the

client-fixer relation more reciprocal and symbiotic in nature. On the other hand, given the

limitations of vote buying strategies in a secret ballot system, politicians in India, have

learned to mix clientelistic vote buying with programmatic appeals and have learned to buy

votes on a ‘wholesale’ basis by appealing to entire communities or ethnic groups, promising

them certain resources upon election, which of course will be diverted to them from the

state coffers and hence, the scope and magnitude of the promises (and in turn, resources)

have only been increasing manifold over the years. Clientelism being a primarily exchange

relationship, depends a lot on direct exchange between the principal and the agent. It

concerns goods from which non-participants in the exchange can be excluded (Kitschelt and

Wilkinson, 2007). Under programmatic politics, parties support issues and policies which

target or directly benefit a very large group of voters, in which only a fraction of voters may

actually end up supporting the party/candidate. However, in clientelistic relationship, as

Kitschelt and Wilkinson point out, the politician’s delivery of a good is contingent upon the

voting actions of specific members of the electorate (Ibid.). In clientelistic exchanges, the

candidates target a range of benefits to individuals or identifiable small group of individuals

who have already given their support or promised to give support to their benefactor. Such

range of goods, given to individuals and small groups are called private goods, or excludable

goods – such as public sector jobs and promotions, or preferential access to scarce resources

like land, public housing, education, social insurance etc. These private goods, help in

creating a long-term patron-client relation. Short-term clientelist exchange on the other

hand, constitutes exchange of private goods like money and other tangible goods like

clothing, food and even liquor, in some cases.

We can thus say that, clientelistic goods are those excludable goods from which the

beneficiaries can be excluded or included based upon the choices they make while voting in

elections or even while declaring their support for a candidate or party before the elections.

Whereas, programmatic goods are those goods, which are given out to an entire class or

group of voters in which every member of the targeted group stands an equal opportunity

to gain from the good, by virtue of him/her belonging to the group and not by virtue of

his/her political obligation.

A clientelist exchange relationship in that sense would be an exchange relationship in which

a politician offers an excludable good to a voter, which is contingent upon his/her direct

support to the politician among all other things.

This will become more clear if we can illustrate it with an example, like in the north Indian

state of Uttar Pradesh, the samajwadi party which came to power in 2011 Assembly

elections announced a Rs.1000 monthly unemployment bonus for all the unemployed

youths of the states falling under the age of 35 years. This means every unemployed youth

in Uttar Pradesh under the age of 35 years is entitled to get a thousand rupees allowance

every month from the state government, irrespective of the fact that he/she is a supporter

of the samajwadi party or not. This payment is also not contingent upon whether the

beneficiary of this scheme voted for the party in the elections or not. This payment of a

thousand rupees is also not a one-time payment like clientelistic exchanges of vote buying

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

10

but rather a continuous payment till the party remains in power (also to be continued

further if the party retains power in the next election or the new party in power deems it fit

to be continued).

On the other hand if we take a politician who distributes Rs.1000 as a one-time payment to

voters during a election campaign and asks them to vote for him in the upcoming elections.

In a secret ballot system where the politician would not be able to monitor whether the

person who has taken money from him will be voting for him or not, this kind of payment

also can be discounted as a welfare policy, hypothetically, as at least it is causing an

immediate welfare of the voter who is getting Rs.1000 for his vote. However, such a

payment comes with a lot of expectations and conditions. The politician for instance will be

relying on a close knit organization of party workers who will be monitoring the activities of

voters over a period of time and then will be narrowing down to a list of voters who are

most likely to vote for the candidate, and money will be given to only them in order to

ensure their support. The candidate does not spend much time and effort in wooing voters

which are completely in opposition to his candidature. It is also not advisable to spend much

resource to woo the core supporters of the party to which the candidate belongs, as these

people are anyways expected to vote for him.

In an electoral market of homogenous prices for individual votes like the ones that exist in

India, parties or candidates try to woo votes collectively by outbidding each other in the

programmatic policies or populist schemes they announce for select classes of voters,

because while clientelistic exchanges have a limited resource, the resources to support

programmatic policies are much large. Another example might elaborate this point more

clearly, like in Tamil Nadu for example if both DMK and AIADMK engage in vote buying in a

constituency, while both will be offering the same price for the voters, the difference will be

seen largely in the populist schemes both the parties will be announcing in their respective

manifestos like Gold jewellery, rice @ 2 rupees/kilo, laptops for students, monthly

scholarships for college students of a particular class, gender specific schemes for school

children etc. A quick look at the extent of clientelism in the Lok Sabha elections of 2009,

across different states and across different parties would now help us understand the extent

of clientelism in India.

IV. View from the ground: A study of Lok Sabha elections 2009

The 2009 General Elections took place in India, between April and May 2009. With an

electorate of around 714 million voters, to elect 543 legislators, this election was said to be

one of the largest democratic elections in the world till date (The Hindu, March 3, 2009).

The Centre for Study of Developing Societies, took out a survey for this election, through

the lokniti group of political scientists. The survey interviewed over 36,000 respondents

from all across India to gauge the Indian voters on a number of social and economic

aspects as well as political issues. In this section, I analyze certain results from this survey

to test some hypotheses and see if the theories of clientelism propounded by the western

literature on the issue, fits the Indian context or not?

The main problem arising out of the study of literature on clientelism is the sense in which

western literature treats clientelism as an endemic problem of poor, underdeveloped and

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

11

relatively new democracies, where voters are content with attaching just a material value of

a limited transaction to their votes instead of the ideal democratic values. Such a kind of uni-

directional thinking treats clientelism as a vertical exchange relationship, ignoring the

bargaining power that democracy has given to the client in a competitive electoral market.

The client in such markets, like those found in the Indian elections, is now much better

placed to choose between alternate patrons making the entire relationship more horizontal.

Also the ways in which clientelism is mixed with programmatic policies is not dealt with

clearly in the scope of such literature which generally views clientelism as undemocratic and

a reason as well as consequence of poverty (stokes, 2004) and underdevelopment in

developing democracies like India. Clientelism is witnessed in its various forms like vote

buying as well as patronage and pork-barrel, in the Indian democratic framework, even

when there is a strong secret ballot system and there are legal restrictions on candidates

handing out cash/gifts to voters in order to buy their votes. The literature that we have so

far seen fails to give an explanation to the reason behind this phenomenon.

The study of a literature on clientelism, when seen in context of the process being practiced

in the Indian democratic framework, raises certain pertinent questions. What is the extent

to which politicians and parties in India engage in clientelistic exchanges? If they do, in a

significant manner, what is the impact of such clientelistic exchanges on the electoral

outcomes, simply put, how much does clientelism matter in elections in India? These are

some of the questions which need to be answered in order to obtain a clear understanding

of clientelism in India. In India, where electoral outcomes are said to be determined by

ethnic attachments, castes, issues, partisanship etc., commonsensical logic derides the use

of any kind of clientelism. In view of so many factors already influencing the voters while

voting for a particular party or candidate it basically seems illogical for politicians to spend

excessive amounts in buying votes, that too in a secret ballot system, yet they do. Over the

years, increasing evidence from the ground suggests that Indian elections see a host of

clientelistic exchanges which are often mixed with as well as mistaken for populist promises.

Q. If this is true, how much clientelism exists in India and to what extent do political parties,

candidates and voters engage in clientelism?

We will be trying to find the answer to this question by testing the following hypothesis:-

Hypothesis 1: Clientelistic exchange is found more among poor, rural, less educated voters

and among those who are found to be at the lower levels of the caste structure.

Results - the analysis was done at the national level, with the help of the NES 2009 dataset.

At this juncture, it would be useful to understand what I mean by clientelism in the following

analysis. While voting in elections, voters have many considerations which determine their

final vote choice. These considerations vary from party, candidate to caste, community,

mohalla/factional support, programmatic appeal of the party or even personal leadership

and/or charisma of any particular leader etc. In order to understand clientelism among

Indian voters, I have defined clientelist voters as those voters who vote for a party or

candidate in return for some given benefit or some expected benefit to them or members of

their family. I have combined the two different vote choices, that for a party and that for a

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

12

candidate into one category, which I call, the clientelist vote choice. So in my analysis, I study

only those voters in India, who have made a clientelist vote choice (voted for a

party/candidate in return for some given benefit or certain expected benefit to them or

members of their family). This was done, keeping in mind the restrains of a secondary level

data analysis and also taking into account the highly individualized and particularistic nature

of a clientelistic exchange relationship.5 By defining clientelism in such a way I am trying to

narrow my focus on the voter, who above all other considerations listed here, considers the

individual benefit obtained/expected by him or members of his family or the benefits from a

party or candidate to be the most influencing factor in determining his vote choice.

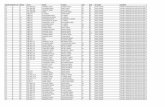

Before we start with the testing of the hypotheses, it would be useful to see, the extent of

clientelism in India. A basic frequency check in Table 1 shows the percent of voters making a

clientelist vote choice at the national level. It appears that 6% of the Indian voters have

made a clientelist vote choice.

Table 1: Clientelist vote choice in India

Number of

Respondents

Percentage out

of total

respondents

Voters who have voted for clientelist benefit from a

party/candidate

2148 6 %

Voters who have voted for a party/candidate for

other considerations

34493 94 %

Total respondents 36641 100.0%

Source: NES 2009, lokniti, CSDS, New Delhi

This is clearly not in tandem with the general perception about clientelism which exists in

India where people think a lot of voters actually vote in return of petty favours or money

and liquor. Table 2 however, shows us a different picture of clientelism in India.

5 The Author agrees to the fact that, the so called ‘benefits’ that voters claim to be driving their vote

choice towards any particular party or candidate, can be a programmatic benefit and a product of a welfare scheme as well, and need not necessarily be a clientelistic exchange benefit. However, the Lokniti questionnaire, offers several such options to the respondents, to declare if their vote choices were motivated by leadership, party programme, caste/ community linkages etc. For more details on the NES 2009 questionnaire, one can visit the lokniti website at www.lokniti.org.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

13

Table 2: Perceptions on clientelism in India

Number of

Respondents

Percentage

out of total

respondents

Total

Respondents

Voters who think money/liquor is rarely given to

buy votes in their locality

3043 60 %

Voters who think money/liquor is often given to

buy votes in their locality

1987 40 %

5030

Voters who feel obligated to vote for politician

from whom they receive gifts/money/liquor

1202 30 %

Voters who vote as they wish despite taking

gifts/money/liquor from politicians

2854 70 %

4056

Voters who feel that in their locality most of the

voters vote in the expectation of favours from

the winning candidate

3416 62 %

Voters who feel that in their locality very few

voters vote in the expectation of favours from

the winning candidate

2071 38 %

5486

Source: NES 2009, lokniti, CSDS, New Delhi

It is quite clear from the above data that a lot of people think that clientelistic exchange

between a voter and a politician takes place quite often in their locality. However, since

these questions are based on merely perceptions of people, dealing in the complexities of

these individual perceptions is beyond the scope of this paper. One perception which I think

is very important and integral in shaping the way we look towards clientelism in the Indian

democratic context is the way people perceive it to affect their democratic right of freedom

of choice to vote. As we can see, an overwhelming 70 percent of the voters feel that they

are free to vote as they wish, even if they accept gifts or favours from politicians in

clientelistic exchange. This fact, surely goes on to show that the way clientelism is practiced

in India has come a long way from the repressive hierarchical manner in which it used to

exist in traditional patron-client relations of earlier times. Democracy indeed as changed the

perception of clientelism among voters and has given them a bargaining power or sorts6.

6 A counter point can be mentioned here by pointing out that even after more than 60 years of

democratic rule and 15 General elections and several more smaller elections to state and different

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

14

However, a detailed statistical analysis will give us a better and coherent understanding of

the clientelist voters in India, which is statistically significant as well.

Hypothesis: Clientelistic exchange is found more among poor, rural, less educated voters and

among those who are found to be at the lower levels of the caste structure.

A profile of the clientelist voters can be hence formulated in accordance to this hypothesis.

The relation between clientelist vote choice and independent factors like caste, class,

locality, level of education and political participation can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Distribution of clientelistic voters within various independent factors

Variable Voters (in %)

Caste

Scheduled Castes 7.5

Scheduled Tribes 4.1

Other Backward Castes 6.4

Upper Castes 5.6

Class

Poor 5.5

Lower 6.9

Middle 6

Upper 5.1

Locality

Rural 6.2

Urban 5.3

other legislative bodies, around 30% of the voters still feel that they will have to give up their democratic right to make their own choice if they sell their vote in an electoral market for a designated price or if they agree to exchange it in return of some petty favors or gifts. This can surely be raised as a point in order to challenge the penetration of democracy over the last six decades.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

15

Variable Voters (in %)

Literacy

Non-literate 6.3

Lowly-literate 5.9

Moderately-literate 6.2

Highly-literate 5.1

Political Participation

No Participation 5.5

Low Participation 6.4

Moderate Participation 7.5

High Participation 9.1

N = 36641

The data in the above table shows the distribution of clientelist voters with respect to the

various socio-economic factors like caste group, class, locality, levels of education and

political participation. The percentage of voters in each column describes the percentage of

voters from that category who have made a clientelistic vote choice in the 2009 lok sabha

elections. The values here might appear to be very close to each other, but when seen

statistically these minute difference in the percentage of voters stand out quite significantly

in a cross-sectional large sized sample survey like the one used in NES 2009.

We can see that when we take voters who have opted for a clientelistic vote choice, among

different caste groups, clientelism is more among the voters from the Scheduled Castes and

Other Backward Castes and relatively less among the voters from Scheduled Tribes and

Upper Castes (Which includes the general/open category as well).

But more striking and surprising is the distribution of clientelist voters in different classes of

people. It is surprising to see that the proportion of clientelist voters is high among the

middle and lower classes as compared to the poorer ones.This challenges our thinking that

the voters from the poor classes are generally susceptible to clientelist benefits.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

16

When we see the distribution of clientelist voters across different localities we find that a

larger percentage of clientelist voters are found in the rural areas as compared to the urban

areas. This is in accordance to the prevalent theories on clientelism which state that

clientelism is found more in rural areas as compared to urban since it is easier to monitor

compliance in a patron-client deal in rural areas than in urban localities.

When we take the percentage of clientelist voter across different levels of literacy we find

that the highly literate voters are less influenced by clientelistic vote choice while voting, as

compared to the non-literates. However what is interesting is to see voters who have a

moderate level of education, at least till matriculation, showing more clientelistic vote

choice than even those with a lower level of education, say till a primary school level.

We can also see that as political participation7 increases among voters, they tend to be

more and more influenced by clientelist vote choice while voting. An explanation on part of

this can be that voters participate in election rallies and meetings in return of certain petty

exchanges of gifts, money or even liquor, as is common knowledge in any election campaign

in Indian elections. However, the theory suggests that those who participate in such election

activities like political rallies, campaigning and door-to-door canvassing are politically

mobilized voters who have already committed their support to the party, based on

leadership, charisma or programmatic appeal or several other factors, but least of all

because of the money and gifts that the party promises to provide them with. Still in India, it

is clear from the data below that a rise in political participation shows a rise in clientelistic

vote-choice.

Therefore, we can say that in India, our hypothesis is almost true as far as locality, literacy

level and caste is concerned, creating only an exception in the bracket of class. This means,

in India, it is not the poor who show clientelistic tendencies but a significant amount of

middle class voters and voters from the lower class engage in party-based clientelism.8

7 For this particular factor, I have created an index of political participation combining three questions

from the NES 2009 into one common question. For the sake of arriving at an index of level of political participation of the voters, I have combined their attendance in election meetings, rallies, and processions etc. and their participation in door-to-door campaigning and canvassing etc. 8 The regression analysis upon which this claim is based on is not included in this paper due to the

space constraints. However the author will be happy to discuss the regression analysis details. The statistical analysis in this paper is a tool to present a set of facts, and given the importance of the facts being presented here, it was thought wise to make space for the facts in place of the statistical techniques like regression analysis.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

17

V. Conclusion

So far we have seen the different definitions of clientelism, the emergence and gradual

evolution of clientelism in the realm of political studies and also the development of

clientelism in India. The paper also showed some revelations about the way in which

clientelism is practiced in the democratic context of Indian elections. Although the western

literature on clientelism suggests that it is the poor, uneducated voters from the rural areas,

who are more vulnerable to clientelistic exchanges during and even before/after elections,

evidence from the Indian case suggests that it is not only the poor and non-literate voters,

but even voters from the middle class and lower class who are showing significantly high

clientelist vote choice. Also, while theory would suggest that voters from the lowest level of

the caste structure will ideally be more vulnerable to a clientelist exchange, in India again, as

evidence suggests voters from the Scheduled Tribes (tribals) show less dependence on

clientelist vote choice while voting. These are definitely interesting points which will be

valuable for further detailed research on clientelism in India. Another observation which

could be made from the analysis was that in India, as political participation increases, in the

form of attending election meeting/rallies, taking part in door-door canvassing and

distribution of pamphlets, etc. the dependence of voters on the clientelist vote choice also

increases.

The probable reason for so many theories, turning turtle in the Indian context cannot be

possibly explained so easily and hence is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it is quite

evident from the above analysis that India is a very specific case to observe the growth and

practice of clientelism and study some of the answers to the failure of western theories of

clientelism lies in its specificities. The mixing of clientelistic exchanges with programmatic

promises by the politicians in India, have certainly blurred certain boundaries of clientelism,

as prescribed in the literature. However, what is needed is not to see clientelism as

something averse to democracy, as it is clientelism, which has been transformed by the

initiation of democracy in the developing world and not the other way round, especially

when one goes to see the various ways in which it is manifested and practiced now.

References

1. Auyero, Javier, 1999, ‘From the client’s point(s) of view: How poor people perceive and

evaluate political Clientelism’, Theory and Society, Vol.28, Kluwer Academic Publishers,

Netherlands. pp. 297-334.

2. Bardhan, Pranab, Sandip Mitra, Dilip Mookherjee and Abhirup Sarkar, 2009, ‘Local

Democracy and Clientelism: Implications for stability in rural West Bengal’, Economic

and Political Weekly, February 28, 2009, Vol. XLIV, No. 9. pp. 46-58.

3. Berenschot, Ward, 2011, ‘Political Fixers and Rise of Hindu Nationalism in Gujarat,

India: Lubricating a Patronage Democracy’, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies,

Vol.XXXIV, No.3. Routledge Publishers. pp. 382-401.

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

18

4. Brusco, Valeria, Marcelo Nazareno and Susan C. Stokes, 2004. ‘Vote Buying in

Argentina’, Latin America Research Review, Vol. 39, No.2 (2004). The Latin American

Studies Association. pp. 66-88.

5. Chandra, Kanchan, 2004. ‘Patronage-democracy, limited information and ethnic

favouritism’ and ‘India as a patronage-democracy’, Chandra, Kanchan, Why Ethnic

Parties Succeed: Patronage and Ethnic Head Counts in India, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge. pp. 47-81, 115-142.

6. Chaves, Miguel Sobrado and Richard Stoller, 2002, ‘Organizational Empowerment

versus Clientelism’, Latin American Perspectives, Vol.XXIX, No.5, Clientelism and

Empowerment in Latin America, September, 2002. pp. 7-19.

7. Chubb, Judith, 1982, Patronage, Power and Poverty in Southern Italy: A tale of two

cities, Cambridge University Press, New York.

8. Dahl, Robert A, 1959, A Preface to Democratic Theory, University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

9. Dahl, Robert A, 1971, Polyarchy, New Haven: Yale University Press.

10. Desposato, Scott W., 2007. ‘How Does Vote Buying Shape the Legislative Arena and

Economy?’, Schaffer, Frederic C (ed.), Elections for sale: The causes and consequences

of vote buying, Lynne Rienner, London. pp. 123-141.

11. Elliot, Carolyn, 2011, ‘Moving from clientelist politics towards a welfare regime:

evidence from the 2009 Assembly election in Andhra Pradesh’, Commonwealth and

Comparative politics, Vol.49:No.1, February, 2011, Routledge. pp. 48-79.

12. Escobar, Cristina, 2002, ‘Clientelism and Citizenship: Limits of Democratic Reform in

Sucre, Columbia’, Latin American Perspectives, Issue. 126, Vol. XXIX, No. 5, Clientelism

and Empowerment in Latin America, September, 2002, Sage Publications. pp. 20-47.

13. Fox, Jonathan, 1994. ‘The Difficult Transition from Clientelism to Citizenship; Lessons

from Mexico’, World Politics, Vol. XXXXIV, No.2, Cambridge University Press. pp. 151-

184.

14. Hopkin, Jonathan, 2006, ‘Conceptualizing Political Clientelism: Political Exchange and

Democratic Theory’, paper presented at APSA Annual Meeting, Philapdelphia, August

31- September 3, 2006.

15. Ippolito-O’Donnell, Gabriela, 2006, ‘Political Clientelism and Quality of Democracy’,

paper submitted at 20th World Congress of the International Political Science

Association (IPSA), to the Panel “Assessing the quality of democracy. Experiences and

criteria," Fukuoka, Japan, July 9-13 2006.

16. Keefer, Philip and Razwan, Vlaicu, 2005, Democracy, Credibility and Clientelism, World

Bank Report, 2005.

17. Kettering, Sharon, 1988, ‘The Historical Development of Political Clientelism’, The

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol.18, No.3, winter, 1988. pp. 419-447.

18. Kitschelt, Herbert and Steven I. Wilkinson, 2007, ‘Citizen-politician linkages: an

introduction’, Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson (eds.), Patrons, Clients and

The Power of Knowledge: Asia and the West, Conference 2013

19

Policies; Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political Competition, Cambridge

University Press, New York. pp. 1-20.

19. Krishna, Anirudh, 2007. “Politics in the middle: mediating relationships between the

citizens and the state in rural North India”, Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson

(eds.), Patrons, Clients and Policies; Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political

Competition, New York, Cambridge University Press. pp.141-158.

20. Kuo, Didi, 2011. The Decline of Clientelism in Advanced Democracies: Towards a

Working Theory, draft from PHD dissertation, Harvard University.

21. Lande, Carl H, 1983, ‘Political Clientelism in Political Studies: Retrospect and Prospects’,

International Political Science Review, Vol. IV, No.4, Sage Publications ltd. pp. 435-454.

22. Lemarchand, Rene and Keith Legg, 1972, ‘Political Clientelism and Development: A

Preliminary Analysis’, Comparative Politics, Vol. IV, No.2. pp. 149-178.

23. Markussen, Thomas, 2010, Inequality and Political Clientelism: Evidence from South

India, Discussion Paper, Dept. of Economics, University of Copenhagen. Available at

SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1690923

24. Roniger, Luis, 2004, ‘Political Clientelism, Democracy and Market Economy’,

Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 3, April, 2004. pp. 353-375.

25. Rubio, Bianca Heredica, 1997. ‘Clientelism in Flux: Democratization and Interest

Intermediation in Contemporary Mexico’, Documento de trabajo; Division de studios

internacioneles, Issue: 31, Centro de Investigacion y Docencia Economicas, 1997.

26. Ruud, Arild Engelsen, 2009, ‘Talking Dirty About Politics: A View From a Bengali Village’,

in Fuller, C.J., Veronique Benei (eds.), The Everyday State and Society In Modern India,

Social Science Press, New Delhi. pp.115-135

27. Schaffer, Frederic C (ed.) 2007, Elections for sale: The causes and consequences of vote

buying, Lynne Rienner, London.

28. Schedler, Andreas and Frederic Schaffer, 2007. ‘What is vote buying?’, Schaffer,

Frederic C (ed.), Elections for sale: The causes and consequences of vote buying, Lynne

Rienner, London. pp. 17-30.

29. Scott, James C., 1972, ‘Patron-Client Politics and Political Change in Southeast Asia’, The

American Political Science Review, Vol.66, No.1, APSA. pp. 91-113.

30. Stokes, Susan, 2007, ‘Is Vote Buying Undemocratic?’, Frederic C. Schaffer (ed.) 2007,

Elections for sale: The causes and consequences of vote buying, Lynne Rienner, London.

pp. 81-99.

31. Stokes, Susan, 2007. ‘Political Clientelism’, Carles Boix and Susan C. Stokes (ed.) 2007,

The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

32. Wantchekon, Leonard, 2003. ‘Clientelism and Voting Behaviour: Evidence from a Field

Experiment in Benin’, World Politics, Vol.55, No.3, Cambridge University Press. pp. 399-

422.