Pietro De Laurentis, \"Zhang Shen’s Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy (Fashu Tongshi). A...

Transcript of Pietro De Laurentis, \"Zhang Shen’s Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy (Fashu Tongshi). A...

Ming Qing Yanjiu XVI (2011) ISSN 1724-8574

Pietro de Laurentis

ZHANG SHEN’S COMPREHENSIVE EXPLANATIONS ON CALLIGRAPHY (FASHU TONGSHI 法書通釋)

A CALLIGRAPHY COMPANION OF THE EARLY MING DYNASTY�

ABSTRACT: This paper presents an early Ming companion on Chinese calligraphy, the Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy (Fashu tongshi 法書通釋) as well as the life of its author Zhang Shen 張紳 (fl. half of the fourteenth century). By analysing the content and the quotations included therein, the present article traces the history and outlines the structure of Zhang’s compendium, while providing also a preliminary translation of the introductory sections of the ten chapters which constitute the entire work. Also, at the same time, through the analysis of biographical materials about the author, Zhang’s life, his official career, personality, and literary works are elucidated. It is concluded that Zhang Shen, an expert classicist as well as a Confucian scholar, whose purpose in his Explanations is to expose and clarify a series of fundamental questions related to the study and practice of calligraphy, which are pertinent to the analysis and interpretation of classical treatises of calligraphy.

1. Introduction In the history of Chinese literature, a very important role is played by certain texts related to aesthetic speculation, as well as by treatises and manuals concerning the actual explanation of artistic matters, � I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Vincent D’Orazio who has kindly read the manuscript and polished my English.

Pietro De Laurentis

62

especially in the area of calligraphy and painting. It is apparent that in the area of calligraphy and painting we notice that since the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 AD), the Chinese have produced an extremely rich tradition of histories, catalogues, compendia, manuals, and many other literary compositions which focus on a wide variety of topics. Such works, despite being dated and quite removed from contemporary trends of Chinese arts, are used today as a fundamental reference for those devoted to Chinese traditional performing arts or artistic historiography. Unfortunately, despite their importance, Western scholars have not dedicated much effort to philological studies in this field. Therefore only a few of those Chinese literary compositions have attracted the attention of non-Asiatic sinologists. Many reasons can be posited for this remission, one reason being their complexity and abstruseness of technical terminology which can be an obstacle to true comprehension of classical treatises. A solution to this problem would be the translation and commentary of these classical treatises on calligraphic technique into Western languages, so that both the theoretical and the aesthetic aspects can be more fully appreciated.1

As we turn to the philological evidence of calligraphic texts, then, we are faced with the problem of which source to follow. Texts on

1 William Acker (1904-1974), translator of the monumental anthology of treatises on Chinese paining Records of Famous Painters from All Dynasties (Lidai minghua ji 歷代名畫記) by Zhang Yanyuan 張彥遠 (ca.817-ca.877), writes that: “The appreciation of the beauty of the swift, strong “calligraphic line,” whether in writing or painting was natural to greater numbers of people than could ever have been the case elsewhere, and it was inevitable that the feeling for the sensitive brush line should become the chief means of judging works of art among a people so well trained to understand just this quality. [...] It seems to me that the early appearance in China of a literature on painting might be said to be in large part due to the existence of the great art of Chinese calligraphy practised by practically the whole of the intelligentsia of the country, and even more directly, to the prior development of a literature on the aesthetics and technique of writing.” Moreover, in relation to Zhang Yanyuan’s other work, the Essential Records on Calligraphy (Fashu yao lu 法書要錄), Acker states that “it is my hope, later, to translate in full a number of the texts contained in the Fa Shu Yao Lu”, but unfortunately he did not fulfill his wish. See Acker 1954: xiii, 215, note 1.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

63

calligraphy are amongst the first pure compositions on aesthetics to have been written by the Chinese,2 hence possessing a pronounced philological tradition of which many modern compositions are merely adaptations of former concepts and phrases. From a historical viewpoint, Chinese texts on calligraphic technique appear relatively late, after evaluations about calligraphers and their works have already existed for many centuries. Actually, technical compendia appear by the beginning of the seventh century, as mentioned for the first time by Sun Guoting 孫過庭 (ca.646-ca.690) in his Manual of Calligraphy (Shu pu 書譜) which is itself a composition on both technical and aesthetic topics.3 During the eighth and ninth centuries, we notice that these types of compositions noticeably increase, as do the compilation of the first two specific anthologies of calligraphic texts, namely the Essential Records on Calligraphy (Fashu yao lu 法書要錄) in ten juan by Zhang Yanyuan 張彥遠 (ca.817-ca.877), author of the Records of Famous Painters from All Dynasties (Lidai minghua ji 歷代名畫記 ), and the anonymous Swamp of Ink (Mo sou 墨藪) in two juan a few decades later,4 where texts concerning technical matters are fully recorded for the first time.5 However, not only are most of these compositions brief and concise, but they also seem quite obscure. Therefore we notice that they do not actually explain technical matters, but rather hint at them in suggestive ways. The question becomes, are these texts to be considered the product of literati’s aesthetic speculation, or should they be seen as simple learning tools for children and novices? Nevertheless, they are still very important and useful, because they reveal many concrete aspects of Chinese traditional literacy and aesthetics which are not found elsewhere. It becomes evident that

2 On the early calligraphic texts, see Zhang Tiangong 2000. 3 On Sun Guoting’s Manual of Calligraphy, see De Laurentis 2008. 4 In Lu Fusheng 1993, 1:9-29. 5 This is the case of two of the very first calligraphic treatises that have been

translated into a Western language, the famous Diagram of the Arrangement of the Brush (Bizhen tu 筆陣圖) attributed either to Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (303-361) or Wei Shuo 衛鑠 (272-349), but very likely a posthumous forgery, and its Colophon (Ti Bizhen tu hou 題筆陣圖後) attributed to Wang Xizhi. See Richard Barnhart 1964, Original texts in Fashu yao lu, 1:5-9.

Pietro De Laurentis

64

there is the utmost urgency to interpret them as accurately as possible in their original form.

Starting with the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), many other collections which record technical treatises have been compiled, such as the highly influential Collection of the Ink Pond (Mochi bian 墨池編preface dated 1066) by Zhu Changwen 朱長文 (1039-1098) in twenty juan,6 and the Anthology of the Calligraphy Garden (Shu yuan jinghua 書苑菁華 , prior to 1237) in twenty juan by Chen Si 陳思 (fl. thirteenth century).7

However, it is only in the fourteenth century that compositions actually explaining the ancient terms and concepts do appear. This is the case of the Essential Precepts of the Hanlin Academy (Hanlin yao jue 翰林要訣) in one juan by Chen Yiceng 陳繹曾 (fl. first half of the fourteenth century),8 the anonymous Secrets of Calligraphy (Shufa sanmei 書法三昧),9 and the Essentials of the History of Calligraphy (Shu shi hui yao 書史會要) in nine juan by Tao Zongyi 陶宗儀 (fl. first half of the fourteenth century).10

With the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties (1644-1911) this tradition of exegetical texts becomes more prevalent with the publication of large and small works, such as the Precept on Calligraphy (Shujue書訣), and the Course on Calligraphy for Children (Tongxue shu cheng 童學書程) by Feng Fang 豐坊 (fl. first half of the sixteenth century) both in one juan,11 the Scattered Records of the Ink Pond (Mochi suo lu 墨池瑣錄) by Yang Shen 楊慎 (1488-1559),12 the Garden of Calligraphy of Ancient and Modern Times (Gujin fashu yuan 古今法書苑) in seventy-six

6 1580 reprint in six juan of the 1568 edition in twenty juan published by the

Taiwan National Library. 1733 edition in twenty juan included in Lu Fusheng 1993, 1: 202-445.

7 Southern Song edition reprint by the National Library of China. 8 In Lu Fusheng 1993, 2: 842-846. 9 Included in the Correct Commentary on Calligraphy (Shufa zhengzhuan 書法正傳), see

note 17. 10 In Lu Fusheng 1992, 3: 1-91. 11 Ibid., 840-862. 12 Ibid., 800-807.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

65

juan by Wang Shizhen 王世貞 (1526-1590), 13 the two impressive collections of the eighteenth century, the Catalogue of Calligraphy and Painting from the Peiwen Study (Peiwenzhai shuhua pu 佩文齋書畫譜 ) compiled by Sun Yueban 孫岳頒 (1639-1708) and others in 1708, and the Records of One of the Six Arts (Liu yi zhi yi lu 六藝之一錄) by Ni Tao 倪濤 (fl. eighteenth century, work completed prior to the Complete Collection of the Four Treasuries -Siku quanshu 四庫全書 which was finalized in 1784), as well as the Correct Commentary on the Technique of Calligraphy (Shu fa zheng zhuan 書法正傳) by Feng Wu 馮武 (d. 1627),14 the Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy by [Ge] Hanxi ([Ge] Hanxi shufa tong jie [戈]漢谿書法通解, preface 1750) by Ge Shouzhi 戈守智 (courtesy name Hanxi, 1720-1786),15 the Correct Model for the Calligraphy (Shu fa zhengzong 書法正宗) by Jiang He 蔣何(fl. eighteenth century) (preface dated 1782) and so forth.16

One of the most important texts in this stream of calligraphic compendia is surely the Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy (Fashu tong shi 法書通釋 ) (hereafter also abbreviated in Explanations) by Zhang Shen 張紳 (fl. half of the fourteenth century) not to be confused with the above-mentioned Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy by [Ge] Hanxi which was indeed very likely influenced by Zhang’s composition, as its title seems to indicate (see chapter 3).

The present study will briefly discuss Zhang Shen’s life, and then will focus on the basic features of his Explanations by outlining its compositional structure along with a preliminary translation of the introductory sections written by Zhang himself. 2. The Author Ming biographical sources contain several pieces of information on Zhang Shen.17 However, the most complete account on his life is found in the Gazetteer of the Licheng Sub-prefecture [Compiled during] the

13 In Lu Fusheng 1992, 5: 1-712. 14 In Lu Fusheng 1996, 9: 804-870. 15 1750 edition reproduced by the Tianjin Ancient Bookstore; in Lu Fusheng 1996,

10: 460-510. 16 In Yu Yu’an (ed.) 1999, 7: 75-128. 17 Tian Jizong 1966, 3:87; Zhou Junfu 1991b: 871.

Pietro De Laurentis

66

Qianlong Reign Period [1736-1796] (Qianlong Licheng xian zhi乾隆歷城縣志) edited by Li Wenzao 李文藻 (1730-1778) and published in 1773. Zhang Shen’s biography is included in juan 40, at the beginning of the Ming dynasty literati (wenyuan 文 苑 ) section of the arranged biographies (liezhuan 列傳). The full text is as follows:

張紳字仲紳,一字士行,自稱雲門山樵,亦曰雲門遺老,濟南衛人。少從事戎馬間,洪武中禮部主事劉康薦其明經。老儒達於治體,可備顧問。十五年驛召至京授鄠縣儒學教諭。十七年十二月以通政使蔡瑄薦擢都察院右僉都禦史。十八年授浙江左布政使。紳有才幹,不屑屑於世事。慷慨激烈,詞辨縱橫。終日亹亹不休。工大、小篆,精於賞鑑。法書、名畫多所品題。撰法書通釋一卷。詩格清健,若不經意而自成一家。朱彝尊明詩綜謂齊東自周公謹後復有此人。據實錄及列朝詩、明詩綜、陸通志、舊志。

按:陸通志載張紳濟南人。舊志謂濟南衛人,實錄謂登州人。蓋紳本登州人而籍於濟南衛也。陸志又雲以勇略薦而實錄雲耆儒。明初薦舉以耆儒爲最重。紳與鮑恂、餘銓、張長年同徵而紳後至。恂、銓、長年皆授文華大學士。恂等力以老疾辭乃放,歸田裏而獨用紳,可謂曠典矣。紳詩載於列朝詩集、 明詩綜者皆琅然可誦。鄉人爲詩在邊華泉先者,紳也。漁洋好表章鄉前輩,乃無一言及之,何哉?18

Zhang Shen’s courtesy name was Zhongshen, according to other sources it was Shixing. He called himself Woodman of the Yunmen Mountain (present day Yunfeng Mountain, Shandong province),19 as well as Veteran of the Yunmen Mountain. 20 He was a native of

18 Fenghuang chubanshe 2004, 4: 630. 19 On Ming dynasty toponyms see, Tan Qixiang 1996, vol. 7. 20 In the Corals in the Iron Net (Tie wang shanhu 鐵網珊瑚) attribute to Zhu Cunli 朱

存理 (1444-1513) we find a colophon by Zhang Shen who signs himself as “Yunmen shanren” 雲門山人(Mountaineer of Yunmen), as well as Yunmen shan lao qiao” 雲門山老樵 (Old Woodman of the Yunmen Mountain) in another colophon included in the Records of Calligraphy and Paintings by Mr. Sun (Sun shi shu hua chao 孫氏書畫鈔) by Sun Feng 孫鳳 (d.u.). See Lu Fusheng 1993, 3:735, 908. From the Sequel to the Essentials on the History of Calligraphy we also learn that Zhang Shen had the literary name (hao 號) Youxuan 友軒. See Xu Shu shi huiyao, in Zhou Junfu 1991a, 72: 362.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

67

Jinanwei (lit. “the Jinan guard”).21 As a young man he participated in military campaigns, and during the Hongwu reign period (1368-1398) he was recommended for appointment as classicist (mingjing 明經) by Liu Kang22 (d.u.) who had the position of bureau secretary in the Ministry of Rites. [At that time] experienced erudites arrived at [possessing the qualities for] governing the state, and so they could be taken as counselors [for government]. On the fifteenth year [of the Hongwu reign period] (1384) [Zhang Shen] was summoned by express dispatch to the capital where he was assigned as instructor in the Confucian school of the Hu county (present day Shaanxi province). On the twelfth month of the seventeenth year [of the Hongwu reign period] (from January 12, 1385 to February 9, 1385)23 due to the recommendation of Cai Xuan (d.u.) he was selected as assistant censor-in-chief in the Censorate. In the eighteenth year [of the Hongwu reign period] (1385) he was assigned as Left provincial administration commissioner for Zhejiang. [Zhang] Shen was able and skilled, he did not get involved in the trivial matters of the human world. He was vehement, eloquent, and unbridled. Until his last days he did not show any sign of fatigue, nor did he spend time resting. He was proficient in the lesser and greater zhuan and was particularly skilled in the connoisseurship and appraisal. As for famous calligraphies and paintings, many are those for which he gave ratings and inscribed colophons. He composed the Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy in one juan. His poetry was clear and vigorous, and he [happened to] create his own style without even paying much attention to it. Zhu Yizun (1629-1709) in his Anthology of Ming Poets said that after Zhou Gongjin [i.e. Zhou Mi 周密 (1232-1298), poet and calligrapher] [died], [it was like] he existed again in Shandong (lit. “Qi at East”).

21 Toponym registered in the Monograph on the Military System (Bing zhi 兵志) of the

History of the Ming. See Ming shi, 90: 2197. 22 In the Sequel to the Cang shu (Xu Cang shu 續藏書) by Li Zhi 李贄 (1527-1602)

published posthumous in 1609, the name of Liu Kang is recorded as Liu Yong 劉 庸, a personage not attested in the sources. In Zhou Junfu 1991a, 106: 47.

23 On the the conversion of historical dates from the Chinese lunar calendar, see Chen Yuan 1956, as well as the informatic system provided by the Academia Sinica Computing Center, available online at the web address http://db1x.sinica.edu.tw/ sinocal/ (accessed December 15, 2010).

Pietro De Laurentis

68

Accounts based on the Veritable Records [of the Ming],24 the Brief Biographies of the Anthology of Poets from the [Ming Dynasty],25 Anthology of Ming Poets, the Comprehensive Gazetteer of [Shandong] by Lu [Yi], and the Old [Licheng] Gazetteer.26

Note: the Comprehensive Gazetteer of [Shandong] by Lu [Yi] records Zhang Shen as a man of Jinan. The Old [Licheng] Gazetteer says that he came from Jinanwei whereas the Veritable Records [of the Ming] state that he was native of Dengzhou (present day Shandong). Very likely [Zhang] Shen was born in Dengzhou, but eventually got inscribed in the official registers of Jinanwei.

The Comprehensive Gazetteer of [Shandong] by Lu [Yi] also says that [he] was recommended for officialdom because of his courage and tactical skill, but the Veritable Records [of the Ming] say that it was because he was a virtuous and experienced erudite. At the beginning of the Ming the practice of recommending officials for their experience and scholarship was at its height. [Zhang] Shen, Bao Xun, Yu Quan, Zhang Changnian were all summoned at the same time, while [Zhang] Shen arrived later. [Bao] Xun, [Yu] Quan, [Zhang] Changnian were all appointed grand academicians of the Wenhua Palace. [Bao] Xun and the others sought to be exempted from their official posts for aging and health reasons, hence they got freed from official posts and went back to their countryside hamlets, whilst [Zhang] Shen alone continued to serve. It can be well said that this was unprecedented regulation.27

24 One of the main historical sources of Ming history, extensively used by the

compilers of the History of the Ming. See Franke 1968: 7, 8-23. 25 By Qian Qianyi 錢謙益 (1582-1664), in Zhou Junfu 1991a, 11: 155-156. 26 The title “Lu tongzhi” is very likely to be considered as a short for “Lu Yi

Shandong tongzhi” 陸釴山東通志 , that is “Lu Yi’s Comprehensive Gazetteer of Shandong.” Accordingly, the two characters ‘jiu zhi’ 舊志 can be interpreted as ‘jiu Licheng xianzhi’ 舊歷城縣志, which means “old Gazetteer of the Licheng County,” a work compiled by Song Zufa 宋祖法 and Ye Chengzong 葉承宗 in 1640. These two texts are briefly treated in Wolfgang Franke 1968:244, 270.

27 Events registered with minor textual differences, in the Monograph on Selections and Recruitement of Officials (Xuanju 選舉) and in Bao Xun’s biography of the History of the Ming (Ming shi 明史). See Ming shi, 71: 1712, 137: 3946.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

69

Those poems by [Zhang] Shen that are included in the Collection of Poems from the Various Dynasties and the Anthology of Ming Poets are all limpid and worthy of being declaimed. [Zhang] Shen was one of those who wrote poetry before Bian Huaquan (i.e. Bian Gong 邊貢, 1476-1532, native of Licheng),28 [However], the Yuyang [Mountaineer] (i.e. Wang Shizhen, 1634-1711) 29 loved to praise those from past generations who came from his same region (i.e. Shandong), but he did not write a single word about him (i.e. Zhang Shen). How can this be?

The oldest source to mention Zhang Shen is the Records of Listed Officials from the [Ming] Dynasty (Guochao lie qing ji 國朝列卿紀) by Lei Li 雷禮 (1505-1581),30 where Zhang Shen is recorded as a man of the Gui 貴 county (xian 縣)31 in the Chizhou 池州 prefecture (fu 府) (present day Anhui province) of the [Southern] Metropolitan Area (i.e. around Nanjing) (zhili 直 隸 , lit. “directly attached”). 32 Another relatively old source, the previously mentioned Sequel to the Essentials of the History of Calligraphy, states that Zhang Shen was registered as a man of Kunshan 崑山 (present day Suzhou area in Jiangsu province), where his parents had moved from Shandong during the Yuan dynasty. 33 In the majority of the colophons recorded in various sources, such as the Corals and Pearls [of Calligraphy and Painting] (Shanhu munan 珊瑚木難) by Zhu Cunli 朱存理 (1444-1513), as well as in those quoted in other sources, Zhang Shen calls himself “Zhang Shen of the Qi Commandery” (Qijun Zhang Shen 齊郡張紳),34 which is not a Ming dynasty toponym, but an ancient administrative unit in

28 One of the “ten talented scholars of the Hongzhi reign period (1488-1505)” (Hongzhi shi caizi 弘治十才子). See Chang Bide 1978: 941.

29 Native of Kaifeng 開封 from a family of Shandong background (Xincheng 新城), he wrote works on poetical criticism. See Hummel 1967: 832.

30 Guochao lie qing ji, in Zhou Junfu 1991, 37: 750. 31 During Ming times, the toponym ‘Guizhou’ is actually registered in the

Xunzhou 潯州 prefecture (present day Guangxi province). See Tan Qixiang 1996, vol. 7, map. 74-75.

32 Twitchett and Mote 1998: 10. 33 Zhu Mouyin 朱謀垔 (d.u.), Xu Shu shi huiyao 續書史會要 [Sequel to the

Essentials on the History of Calligraphy] (compl. 1611), in Zhou Junfu 1991, 72: 362. 34 Lu Fusheng 1992, 3: 338, 1994, 6: 522.

Pietro De Laurentis

70

Shandong including the Licheng county.35 Besides these accounts, in a colophon included in the Corals in the Iron Net (Tie wang shanhu 鐵網珊瑚) attributed to Zhu Cunli, Zhang Shen signs himself as ‘Woodman from Mount Jingnan’ (Jingnanshan qiaozhe 荊南山樵者 ), West of present day Suzhou.36 However, the Biography of Zhang Shen as well as the other sources quoted thereby, seem to stress Zhang’s affiliation to the Shandong area, being either with Jinanwei or Dengzhou. In case Zhang Shen was not born in Shandong, then, we must presume that his family possessed a strong cultural attachment to the Shandong area, to the point that, Chen Qi 陳頎 (fl. half of the fifteenth century)37 in his Tingyu Palace Records of Various Worthies (Tingyulou zhu xian ji 聽雨 樓 諸 賢 記 ) considered him “an outstanding literatus of the North”(北方豪傑之士).38

As for Zhang Shen’s birth and death, there are no precise dates, but, judging from the accounts recorded in the sources, he was appointed due to his expertise in 1385, therefore he must have been at that time considerably mature, very likely over forty years of age, and consequently he must have been born under the Yuan, during the first half of the fourteenth century. Regarding his death, we have no relevant information, but, from the Diary of the Weishui Study (Weishui xuan riji 味水軒日記) by Li Rihua 李日華 (1565-1635) we know that he must have been alive during 1404 (jiashen甲申 year of the Yongle 永樂 reign period), at over 60 years of age.39 Therefore we can further infer that Zhang Shen must have died during the first decades of the fifteenth century. From the various accounts we learn that Zhang Shen was renown at his time both for tactical skill and literary knowledge, and that through such qualities, either the former or the latter, he eventually entered officialdom. If the account on him being born in the Jinanwei is correct, very likely he might have been involved or trained in military matters since his childhood. In fact,

35 Gu Zuyu 2005: 1458. Quoted in Morohashi 1960, 12: 1082. 36 Lu Fusheng 1992, 3: 746. 37 Chang Bide 1978: 597. 38 Quoted in Recorded Events on Ming Poets (Ming shi jishi 明詩紀事) by Chen Tian

陳田 (fl. late ninenteenth century), in Zhou Junfu 1991, 12: 791. 39 See Lu Fusheng 1992, 3: 1237.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

71

during the Ming dynasty a system of ‘guards and garrisons’ (weisuo 衛所) was created in order to insure military protection to the strategic areas of the empire, as well as to tie military families to their specific zone,40 and Jinan was just a guard in the Northern Metropolitan area. In addition, at the beginning of the Ming a new administrative system was built up, and it was common for the emperor’s circle to recruit officials through the personal recommendation of dignitaries. Evidently enough, Zhang Shen must have been so impressive a figure in his regional environment that he was considered particularly fit for occupying an official post.

From the passage quoted we also know that Zhang Shen had a vigorous temper, was a skilled orator, and was also a talented poet.41 All these characteristics seem to be reminiscent of the matching balance of the traditional qualities fundamental for a ‘literatus-knight’ (shi 士), namely civil virtue (wen 文) and military power (wu 武).42 At the same time, though, through the clear instructive and exegetical approach of his Comprehensive Explanations and the numerous colophons that he inscribed, not only did he show his appreciation of calligraphy as an art form,43 but, we can also say, he manifested his ‘educational’ commitment as a Confucian scholar. For this reason, then, his enlightening explanations and discussions of technical terms

40 See Twitchett and Mote 1998: 62, 100. 41 Eleven brief compositions by Zhang Shen, such as colophons, poems, and lyrics

are recorded in the Recorded Events on Ming Poets, whereas various calligraphy catalogues such as the Collected Studies on Calligraphies and Paintings of the Shigu Hall (Shigutang shuhua hui kao 式古堂書畫彙考) by Bian Yongyu 卞永譽 (1645-1712), include many of his colophons. See Zhou Junfu 1991, 12: 792-795; Lu Fusheng 1994, 6: 522, 550, 654-655, 656, 659-660.

42 The earliest account on such an educational procedure is found in the sons of aristocracy of the Zhou 周 (1045-256 B.C.) who were taught the so-called six arts (liu yi 六藝), namely ritual, mathematics, writing, archery, chariottering, and music. See Loewe and Shaughnessy 1999: 583.

43 Willard Peterson has recalled the importance of calligraphy, painting, and artistic pursuits in general for Confucian literati of the late Ming, by mentioning, for instance, Wang Shizhen, author of the Garden of Calligraphy of Ancient and Modern Times, whose artistic efforts can at least be partially compared with those of Zhang Shen. See Twitchett and Mote 1998: 772-773.

Pietro De Laurentis

72

are especially useful for understanding from a simpler perspective the somewhat obscure and remote language of calligraphy, and therefore do still provide an important tool for classical calligraphic studies. Besides his Confucian foundation, though, we also learn that Zhang Shen was somewhat attracted by Taoism as well. In fact, in a colophon included in the Collected Studies on Calligraphies and Paintings of the Shigu Hall (Shigutang shuhua hui kao 式古堂書畫彙考) by Bian Yongyu 卞永譽 (1645-1712), we find Zhang Shen’s signature as “taoist of the Yunmen mountain” (Yunmenshan daoren 雲門山道人 ) dated January 1, 1386 (yichou 乙丑 12.15). 44 Together with Zhang’s relationship with the Yunmen mountain indicated by his self-given names, we can infer that at some point in his life, perhaps during his last years, he became close to Taoist philosophy and, at least in theory, to the life of a recluse. From some sources, in fact, we know that he died while in the service of the Left provincial administration commissioner for Zhejiang, 45 thus his longing for retreat to the Yunmen mountain was perhaps more symbolic rather than a real solution for his life.

3. The text The Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy do not appear in the bibliographic catalogue of the History of the Ming (Ming shi 明史) compiled by Zhang Tingyu 張廷玉 (1672-1755) and others (completed in 1739), which was mainly based upon the earlier Catalogue of Books from the Qianqing Hall compiled by Huang Yuji 黄虞稷 (1629-1691).46 The earliest record of Zhang Shen’s Explanations is found in the Sequel to the Essentials on the History of Calligraphy (Xu Shu shi hui yao 續書史會要) by Zhu Mouyin 朱謀垔 (d.u.) completed in 1611,47 and a brief bibliographic account is also found in the Abstracts of the General Index of the Complete Collection of the Four Deposits.48 The Abstracts record an

44 Lu Fusheng 1994, 6: 290. 45 Such as the Brief Biographies of the Anthology of Poets from the [Ming Dynasty] (Lie chao

shi ji xiaozhuan 列朝詩集小傳) by Qian Qianyi 錢謙益 (1582-1664), in Zhou Junfu 1991a, 11: 156.

46 Wilkinson 2000: 895. 47 In Zhou Junfu 1991, 72: 362. 48 Ji Yun 1971, 114: 2374.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

73

edition kept by Confucius’ descendant Kong Zhaohuan 孔昭焕 (d. 1783), that, unfortunately, has not survived to our present day, but might have been perhaps a close version of Zhang Shen’s original work, since Kong was a native of Shandong as well. Since neither the original edition of the Complete Collection of the Four Deposits nor other pre-modern collectanea included Zhang Shen’s work, the earliest edition nowadays available of the Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy is found in the collection Yimen guangdu 夷門廣牘 (literally, “Broad Compositions of the Seclusive Residence”),49 a series of books edited by Zhou Lüjing 周履靖 (fl. second half of the sixteenth century) and cut in 1598 at Jinling 金陵 (present day Nanjing) by his firm Jingshan shulin 荆山書林.50 The series contains a total of 109 titles and 106 juan arranged according to thirteen different categories. The fourth of these, that of ‘calligraphy’(shufa 書法 ), contains three texts, Zhang Shen’s Explanations, the Primer for Official Seeking a Salary (Ganlu zishu 干祿字書) by Yan Yuansun 顏元孫 (668-732), and the Collection for Studying the Ancients (Xuegu bian 學古編) by Wu Yan 吾衍 (1268-1311) covering juan 28-30. Zhou Lüjing was himself versed in calligraphy and painting,51 and he also included a section on painting texts entitled “swamp of painting” (hua sou 畫藪) for a total of seven texts (juan 31-37), six of which were composed by him. The Abstracts of the General Index of the Complete Collection of the Four Deposits (Siku quanshu zongmu tiyao 四庫全書總目提要 ) (hereafter abbreviated in Abstracts) do not give Zhou’s publishing work a high

49 In the Abstracts the word yimen 夷門 is explained as “self-dwelled seclusive

residence”(自寓隱居). Ibid., 134: 7. 50 Zhou’s preface dated 1597 (year dingyou 丁酉 of the Wanli 萬曆 reign period),

prefaces by Huang Hongxian 黃洪憲 (1541-1600) and He Shiyi 何士抑 (d.u.) dated 1598 (year wuxu 戊戌 of the Wanli reign period). Reproduction of the 1598 edition in the Photo-printing of Ten Rare Editions of Collectanea from the Yuan and the Ming Dynasties. On Zhou Lüjing, see Ye Junqing 2007. According to Wu Kuang-ch’ing the collection was cut in 1603, but there is no account of such a date in the sources. See Wu Kuang-ch’ing 1943: 249.

51 Mingren zhuanji ziliao suoyin, 332.

Pietro De Laurentis

74

rating, mainly because of the inaccurate edition of the texts included.52 The compilers of the Abstracts criticize Zhou for having missed, after the ‘broad elegance’ (bo ya博雅) section, the three sections “honoring life” (zun sheng 尊生), ‘calligraphy’, and ‘swamp of painting’ which, according to them, appear only in the index. 53 Actually, such a criticism should be regarded as the result of the editorial shortcomings of the edition consulted by the compilers of the Abstracts, for we know that the actual 1598 edition of the Yimen guangdu does include those three complete sections.

The Yimen guangdu edition of the Explanations was eventually used for the publication of modern collections of classical texts, and therefore it can be said that it is nowadays the one and only existing edition of Zhang Shen’s work.54

The Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy which differ from the other two texts of the calligraphy section, are not redacted by Zhou Lüjing alone, but are also edited by the calligrapher and painter Chen Jiru 陳繼儒 (1558-1639).55 In the Boat of Paintings and Calligraphy from Qinghe (Qinghe shu hua fang 清河書畫舫) by Zhang Chou 張丑 (1577-1643) there is a quotation from the Records of Softly Tangling Antiques (Ni gu lu 妮古錄) by Chen Jiru where we learn that on April 7, 1595 he had bought a hand-written copy of the Comprehensive Explanations and the Essential Precepts of the Hanlin Academy by Chen Yiceng at the Wutang 武唐 market.56 Therefore we are very likely to presume that

52 In the bibliographic criticism of the Yimen guangdu we read: “所收各書,真僞雜出,漫無區別。” (As for each book that has been included, both originals and forgeries appear in mixture, without any differentiation throughout [the collection]). Ji Yun 1971, 134: 2771.

53 Ibid.. 54 The present study is based upon the Congshu jicheng chubian edition where, on the

second page, we read: “初編各叢書僅有此本” (The First Series [of the Collection of Collectanea] as well as every other collectanea has only this [i.e. the Yimen guangdu edition of the text]). See Wang Yunwu 1936, 1621: 1-108; Lu Fusheng 1992, 3: 307-322.

55 Fashu tongshi, 1. 56 Lu Fusheng 1992, 4: 271. Professor Craig Clunas suggests that the character tang

唐 should be read as 塘, resulting then in a famous market in the city of Yangzhou 揚州 in modern Jiangsu.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

75

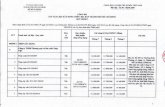

the version published in the Yimen guangdu was based upon this hand-written copy. The work consists of two juan57 (shang 上 and xia下) which comprise ten different chapters (pian 篇) in total, namely: eight methods (bafa 八法), structure (jiegou 結構) in the first juan; holding and wielding [the brush] (zhi shi 執使 ), sheet and detail [composition] (pianduan 篇段), following the ancient [models] (cong gu 從古), establishing the patterns (li shi 立式), distinguishing the scripts (bian ti 辨體), denominations [of strokes] (mingcheng 名稱), efficient tools (li qi 利器), and summarizing discussions (zong lun 總論) for the second juan. Each of these ten sections are made of an introductory paragraph composed by Zhang Shen himself, and a series of excerpts and quotations from previous treatises. The composition bears no preface nor postface, however, as the arrangement of its content fully expresses, the Explanations were meant to provide a thorough tool for the study and practice of calligraphy by mixing Zhang Shen’s own views with the ideas conveyed by pre-existing works. Only in the last chapter of the book, which summarizes the content, do we find a general description of the whole work:

通釋之作共得十篇,屬辭比事,以類相從。58

The work Comprehensive Explanations reaches in total ten chapters [of length]. It creates entries and arranges topics which follow one another in an ordered sequence.

The compound ‘tongshi’ 通釋 (comprehensive explanations) is not used as a title for the first time in Zhang Shen’s companion, but it had been previously used by Confucian scholars dealing with exegetic topics, such as in the Comprehensive Explanations on the Geographic Section of the Comprehensive Mirror [for Aid in Government] (Tongjian dili tongshi 通鑒地理通釋 ) by Wang Yinglin 王應麟 (1223-1296), 59 and the

57 In the “Biography of Zhang Shen” included in the Gazetteers of the Licheng County

(see previous translation) the text is recorded in one juan. As already pointed out in the Abstracts, this must have been a copying error rather a different edition of the text. See Ji Yun 1971, 114: 2374.

58 Ibid. 90-91. 59 Ji Yun 1971, 47: 1031; Chang Bide 1976: 369.

Pietro De Laurentis

76

Comprehensive Explanations (Tongshi 通釋) Lü Zuqian 吕祖謙 (1137-1181) which are described in the Abstracts as follows:

通釋三卷,如說經家之有綱領,皆錄經典中要義格言。60

The Comprehensive Explanations in three juan seem to discuss of the basic principles of the Confucian school, as they all record the essential meanings and the instructive maxims of the classics.

As we have seen while discussing Zhang Shen’s life, he served as an instructor in the local Confucian school in the Hu county, therefore his training into the classics as well as in works such as the two philological works above-mentioned can be imagined accordingly. Thus, Zhang’s choice of titling his work ‘comprehensive explanations’ might have come from his acquaintance of these Confucian exegetical texts, from which he perhaps got inspiration to compile an analogous companion dealing with a calligraphic topic. No wonder, then, that in the sixth chapter “establishing the patterns” he admonishes: 如經學文字,必當真書[...]61 Texts on Confucian classics must be written in the standard script [...]

Throughout the Explanations we notice Zhang Shen’s attempt at clarifying and exposing calligraphy in a plain and accessible sequence. As we can see from the ten chapters into which he divided his companion, the themes were developed throughout a logical progression.

The first chapter is devoted to the discussion of the “eight methods of the character yong” (yongzi bafa 永字八法),62 which has been, at least from the eleventh century onwards,63 the most popular set of brush-strokes and brushwork precepts for calligraphic training. At the same time, a series of different single brush-strokes and more complex elements are treated as well, through both the quotation of ancient sources and Zhang’s own illustrative notes. Zhang pursues a

60 Ji Yun 1971, 47: 1041. 61 Fashu tongshi, 68. 62 Ibid., 1-28. On the eight methods, see De Laurentis 2010. 63 On early compendia of calligraphic technique, see De Laurentis 2011.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

77

detailed discussion of technical terms, trying to associate ancient words and definitions with those in common usage in his time.

The second chapter, “structure”,64 focusses on the compositional devices governing the structure of characters by quoting a wide range of calligraphic sources, not only do the various entries deal with theoretical principles, but they also treat a large set of characters by combining those with similar structural features into uniform groups, as well as attaching an appendix with illustrative clues on regards of the writing order of particularly articulated characters. The first two chapters occupy 45 pages out of the total 110, nearly half of the whole work, and therefore are grouped, also because they deal with strict technical issues, in the first juan of the Explanations.

The third chapter, “holding and wielding [the brush]”,65 discusses the technical skills required to hold and wield the brush properly, again with the aid of copious citations from ancient texts.

In the fourth chapter, “sheet and detail [composition]”,66 Zhang Shen moves towards more subtle and less descriptive topics, such as those of “style”, “variation”, “demeanor.” The discussion treats aesthetic questions regarding the sequenced uniformity to be expressed throughout the whole composition by adjusting and modulating dialectical qualities such as convergence/divergence, hiding/exposure, dark/light, fat/slim and so forth.

The fifth chapter, “following the ancient [models]”, 67 openly reminds the reader to grasp the diacronic connections amongst the various scripts of the Chinese writing system, that is to possess the relevant palaeographical knowledge to decipher correctly components and elements from archaic scripts and follow them while writing according to the modern scripts.

In the sixth chapter, “establishing the patterns”, 68 Zhang Shen provides some basic principles for writing with efficacy, and then lists a series of calligraphies in the standard, the zhang cursive (zhangcao 章

64 Ibid., 28-45. 65 Ibid., 47-60. 66 Ibid., 60-64. 67 Ibid., 64-68. 68 Ibid., 68-78.

Pietro De Laurentis

78

草), the flying-white (feibai 飛白), the semi-cursive, cursive, and the mixed scripts (zati 雜體), alerting the reader not to follow the last category.

The seventh chapter, “distinguishing the scripts”,69 continues the discussion about the same scripts just treated in the fifth section, by describing the history and formal characteristics of each one.

In the eighth chapter, “denominations [of brush-strokes]”,70 Zhang Shen lists the configurative variations of six basic brush-strokes, namely the dot-stroke (dian 點), the horizontal stroke (heng 横), the vertical stroke (shu豎), the hook-stroke (lit. “hooping stroke”) (ti 趯), the halberd-stroke (ge 戈), the left-falling stroke (pie 撇), the right-falling stroke (lit. “wave-stroke”) (bo 波), plus five general terms.

The ninth chapter, “efficient tools”,71 is related to the so-called “four treasures of the literatus’s study” (wenfang sibao 文房四寶 ), namely brush (bi 筆), ink (mo 墨), paper (zhi 紙), and ink-stone (yan 硯).

The tenth and conclusive chapter, “summarizing discussions”,72 represents a condensed outline of the whole work, for it records those quotations that Zhang Shen was not able to include in the other nine chapters, and consequently deals with different topics.

An important characteristic of the Comprehensive Explanations is that Zhang Shen quotes a great number of sources. Its ten chapters, in fact, include citations from over fifty works, spanning from personages of the Six dynasties period, such as Tao Yinju 陶隱居 (i.e. Tao Hongjing 陶弘景, 456-536),73 to Zheng Zijing 鄭子經 (i.e. Zheng Biao 鄭杓, fl. early fourteenth century) of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). 74 From this perspective, thus, we can regard Zhang Shen’s Explanations as one of the embryonic philological studies in regards of calligraphic education that will greatly develop during the next four centuries and that we have briefly surveyed in the introduction.

69 Ibid., 78-86. 70 Ibid., 87-90. 71 Ibid., 90-96. 72 Ibid., 96-107. 73 Ibid., 33. 74 Ibid., 55.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

79

Below we provide a preliminary translation of the introductory parts of the Comprehensive Explanations for they most directly convey Zhang Shen’s views and attitude towards the practice of calligraphy.

4. Translation of the Introductory Sections of the Ten Chapters Composing the Text 4.1 Eight Methods (with components and elements attached)

八法篇第一偏旁附

八法之道,肇自隸楷。崔、蔡、鍾、張皆祕其說。二王之後,傳之永師。降及歐、虞尤宗其法。誠以所用該於萬字,墨道之最不可不明也。八法者,永字八筆是矣。一曰側,二曰勒,三曰努,四曰趯,五曰策,六曰掠,七曰啄,八曰磔。而八法之外亦有增明,故衛夫人筆陣、歐陽率更八訣,翰林密論廿四條,學者不可以莫之考也。今於八法之下,以類比附,亦自簡而詳,由約而博之義。75

The way of the eight methods started from the clerical (li) and standard (kai) [scripts]. Cui [Yuan 瑗] (77-142), Cai [Yong 邕] (132-192), Zhong [You 繇] (151-232), Zhang [Zhi 芝] (d. 192) all kept secret its theory. After the Two Wangs (i.e. Wang Xizhi, 303-361 and his seventh son Wang Xianzhi 王獻之, 344-386) they were transmitted to [the buddhist monk Zhi 智]yong. Reaching at Ou[yang Xun 陽詢] (557-641) and Yu [Shinan 世南] (558-638), they especially followed their technique. Certainly [it can be said that] what is be attributed to them is comprised in the ten thousand characters: [Thus] they are by far what one should absolutely understand in the Way of the ink. These eight methods are just the eight strokes of the yong character. The first is called dot-stroke (ce), the second horizontal stroke (le), the third vertical stroke (nu), the fourth hoop-stroke (ti), the fifth whip-stroke (ce), the sixth left-falling stroke (lüe), the seventh short-left falling stroke (zhuo), the eighth right-falling stroke (zhe). Besides the eight methods there are also additions and explanations, such as the Diagram of the Brush by Lady Wei, the Eight Precepts by the director of the Court of the Watches Ouyang (i.e. Ouyang Xun),76 the Secret Discussion of the Hanlin Academy in Twenty-

75 Fashu tongshi, 1-2. 76 Very likely a posthumous forgery, included in Shu yuan jinghua, juan 2.

Pietro De Laurentis

80

four Paragraphs, 77 students cannot but examine anyone of them. In the present composition, after the eight methods, I will attach and compare [the other glosses] according to fixed categories, with the intention of making [people obtain] the exaustive from the simple, and [reach] the vast from the concise.[...]

4.2 Structure (forms and configurations) 結構篇第二形勢

結構之道,隨字賦形。長短、廣狹、疏密、肥瘦,各有其態。或橫或豎,如坐如臥。或斜或正,如立如行。或上短下長,或上長下短,或一字三停,或一字中斷。或二字無重立,或兩字並成。或全用一、二、三、四字以合成,或省用一、二、三、四字以輳成。或上覆下承,或左顧右盻,或豎開以夾別字,或橫圻而裹別字。繁簡不同,小大亦異,不有結構,安可成形?故宋高宗雲:“正書之字,八法俱備,皆可正讀,所謂楷法是也。”78

The way of composing and constructing [consists in] following the [peculiarities of] characters and structuring the forms. As for the long and short, wide and narrow, loose and tight, fat and slim [forms], each has its configuration. Some [characters] are horizontal, some are vertical, some seem like sitting, others are like lying down. Some are oblique, some are straight, some are like standing up, others are like proceeding. Some [characters] are short in their upper part and long in their lower part, some are long in their upper part and short in their lower part. In some cases one character is [composed] of three parts, in others one character is torn in the middle. In some cases two characters are not erected in repetition [as components in one character], in others two characters are juxtaposed together [composing one single character]. In some cases [one character] uses completely one, two, three or four characters in order to complete [its structure], in others, one character avoids using one, two, three or four characters in order to fit [its structure]. In some [characters] the upper part is dominant and the lower part acts a support. In some [characters] the left and right parts are oriented to each other. Some [characters] are opened up vertically in order to contain other [smaller] characters, others are split horizontally in order to include other [smaller] characters. Since the complexity and the simplicity [of characters] are different, as well as their

77 Author unknown, included in Shu yuan jinghua, juan 2. 78 Fashu tongshi, 28-29.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

81

dimensions, how can the shape be obtained without structuring principles? Thus Gaozong of the Song (i.e. 趙構 (1107-1187, r. 1127-1162) said: “As for characters in the standard script, [as] they are comprised of the eight methods, they will all be read correctly. This is what is called the standard method [of characters].”79[...]

4.3 Holding and Wielding [the Brush]執使篇第三

執筆之法,謂之執使者。執,謂執筆,使,謂運用。故孫過庭有執、使、轉、用之法。姜堯章雲:“執謂淺深長短。使謂縱橫牽制。轉謂鉤環盤紆。用謂點畫向背。”執之在手,手不主,運之在腕。腕不知執,是也。其法具後。80

The methods of holding the brush are called holding and wielding. Holding refers to holding the brush, wielding to moving and applying. Thus Sun Guoting had the methods of holding, moving, turning, and applying. Jiang Yaozhang (i.e. Jiang Kui 姜夔, 1163-1202) said: “Holding refers to narrow, deep, long and short [in keeping the brush]. Wielding refers to [directing the brush] vertically and horizontally, pulling and restraining [it]. Turning refers to [producing] hooks, loops, circles, and whirls. Applying refers to [configuring the shape of strokes], as well as to convergences and divergences.”81 Holding it (i.e. the brush) depends on the hand, but the hand does not command it, whereas moving it relies in the wrist. This is just [meaning that] the wrist is not aware of holding the brush. Such methods are all as follows.[...]

4.4 Sheet and Detail [Composition] (temperament, variations, demeanor) 篇段篇第四 情性 變化 風神

古人寫字正如作文:有字法,有章法,有篇法。終篇結構首尾相應。故雲:“一點成一字之規,一字乃終篇之主。”起伏、隱顯、陰陽、向背有意態。至於用墨、用筆,亦是此意。濃淡、枯潤、肥瘦、老嫩,皆要相稱。故羲之能爲一筆書。蓋禊序自「永」字至

79 In Lu Fusheng 1993, 2: 2. 80 Fashu tongzhi, 47-48. 81 Quotation actually from “Mr. Sun” (孫氏. i.e. Sun Guoting) corresponding to

Columns 193-196 of his Manual of Calligraphy. See Jiang Kui, Xu Shu pu, Baichuan xuehai 百川學海 edn. (1273) in Wang Yunwu 1936, 1621:4. For a reproduction and transcription of the Manual of Calligraphy, see Tanimura Kisai 1979.

Pietro De Laurentis

82

「文」字筆意顧盻。朝向、偃仰、陰陽、起伏、筆筆不斷,人不能也。書平[i.e. 評]稱褚河南字裏金生,行間玉潤,以爲行款。中間所空素地,亦有法度。疏不至遠,密不至近。如織錦法,花地相間,須要得宜耳。

82

The writing of characters by the ancients was just like composing a text: there was a style (fa) for characters, for paragraphs, and for the whole sheet. The structure [of characters] throughout the sheet was mutually connected from the beginning to the end. Therefore it is said: “One dot-stroke character becomes the rule for the whole character, one character acts like the founding principle for the whole column.” 83 Rising and falling [movements of the brush], hidden and manifest [configurations], yin and yang [modulations], convergences and divergences [of forms], all possess stylistic expression (yitai). As for the application of the brush and of the ink, the meaning is the same as this. Deep and light, dry and moist, fat and slim, old and tender, all [of these characteristics] have to mutually match. Thus [Wang] Xizhi was capable of making a calligraphy with a single movement of the brush. Hence, in the Preface of the Orchid Pavillon Collection84 from the character yong to the character wen the aesthetic sense of brush-strokes is connected to each other. [In regards of] its facing and direction, its pushing down and lifting up, its yin and yang, its rising and falling, each stroke is unbroken [in its connection to the others]. [This is something] that [common] men are not capable of. Calligraphic critics state that [in regards of] Chu Henan’s (i.e. Chu Suiliang 褚遂良, 596-658) calligraphy, gold was born from within the characters, and the moisture of jade [permeated] the columns. With this he created the pattern [of his calligraphies]. As for the space left blank inside the composition, it has norms and patterns as well. Looseness [amongst brush-strokes] should not reach remoteness, and compactness should not reach nearness. Similarly with the technique of brocade, where the flowers and the background alternate, it is necessary to be just appropriate.

82 Fashu tongshi, 60-61. 83 Quotation from Sun Guoting’s Manual of Calligraphy (Shu pu), column 317-318,

last character zhun 准 instead of zhu 主. 84 The most famous calligraphy in East Asia, written by Wang Xizhi on April 22,

353. Original lost, only copies from the Tang and later periods survive. For reproduction and discussion, see Liu Tao 1997a:41-45; Liu Tao 1997b: 353-355.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

83

4.5 Following the Ancient [Models] 從古篇第五

自蒼頡始造書契而古文、篆、隸相以生。今之真書,即古隸法。行草二體,皆自此生。故善書者筆蹟,皆有本原偏傍,俱從篆、隸。智者洞察,昧者莫聞。是以法篆則藏鋒,折撘則從隸。用筆之向背,結體之方圜、隱顯之中,皆存是道。人徒見其規模乎八法而不知其從容乎六書。近時惟吳興趙公爲能知此,其他往往皆工點畫,不究偏旁。古法蕩然,非爲小失。然而古人祕此,論說罕聞。間有二、三爲著於此。85

After Cang Jie created writing marks for the first time,86 the ancient script, the zhuan script, and the clerical script have arisen accordingly. The standard script of the present day is the ancient clerical script, from which the semi-cursive and cursive scripts have all been born. Therefore regarding the compositions by those who excell in calligraphy, they all possess [the quality of] examining the origin of elements and components, and they all follow the zhuan and clerical scripts. Those who are wise perceive it clearly, whereas for those who are stubborn there is no one who has heard anything [about it]. Hence, comforming to the zhuan script means to hide the tip of the brush [while tracing a brush-stroke], whereas turning [the tip] is for [those who] follow the clerical script. As for the divergences and the convergences in brushwork, the squared and curved [configurations] of character-structuring, and within the hiding and exposing [devices], all of these [features] contain such a principle. People see that [those features] are regulated upon the eight methods, but they do not know that they take their shape from the six scripts. In recent times only Master Zhao from Wuxing (present day Zhejiang province) (i.e. Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫, 1254-1322) has been one who was capable of knowing such [principle]. Whereas all the others just practice brush-strokes, without investigating [the nature of] components and elements. [In this way] the old style vanishes, and this is surely not a small loss. However, the ancients rather kept these principles secret, thus treatises and discourses are rarely heard. There are two or three compositions, that I will record hereby.

85 Fashu tongshi, 64-65. 86 Mythical inventor of writing, annalist of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi 黄帝).

See Qiu Xigui 2000:44.

Pietro De Laurentis

84

4.6 Establishing the Patterns 立式篇第六

凡寫字,先看文字宜用何法。如經學文字,必當真書,詩賦之類,行、草不妨。又看紙、筆、卷、冊合用字體大小,務使相稱。然後尋古人寫過樣子,如小楷有黃庭、樂毅、畫贊、曹娥,各自法度不同。今所寫當用何者爲法?凝神存想,乘興下筆。立一字爲一篇之主,分其章,辨其句。爲之,起伏隱顯。爲之,向背開合。爲之,暎帶變換。情狀可以生,形勢可以定,始可言書矣。唐韓方明授筆要說雲:“欲書先當想,看所書一紙之中是何詞句、言語多少及紙色目相稱,以何等書與今書體相合,或真或行或草,與紙相當。有難書之字,預須心中佈置”。今擇漢魏而降以及晉唐遺刻之美者,真、行、草書,以類相從,列爲十等,具錄於後。87

When writing characters, one should first see which script is suitable for the text [chosen]. For example, texts on Confucian classics must be written in the standard script, whereas for poems and rhapsodies the semi-cursive and the cursive might as well be adopted. In addition, one should pay attention to the dimension of characters that is appropriate for the paper [used], the brush, the scroll or the codex, so that the [various tools] are complementary to each other. Afterwards one should look for samples written by the ancients, such as for the small standard script there is the [Classic of] the Yellow Hall, the [Discouse] on Yue Yi, the Appraisal of the Portrait of [Dongfang Shuo], the [Stele of] Cao E.88 Each [script] has its different norms and patterns. At the present time, about what one is writing what should be taken as a norm? Concentrate the spirit and reserve the thoughts, and then one will wield down the brush in accordance with one’s emotions. One character represents the ruling principle of the whole sheet, diving the chapters of the text and distinguishing its sentences. In writing it [represent] the rising and falling [movements of the brush], and the hidden and manifest [configurations]. In writing it [express] the divergencies and convergences [of forms], and their closings and openings. In writing it [show]

87 Fashu tongshi, 68-69. 88 For reproduction and discussion, see Liu Tao 1997a (ed.), Zhongguo shufa quanji

18, 104-108, 93-98, 109-114; Liu Tao 1997b: 368-369, 366-368. 369-370. No Wang Xizhi’s versions of the Stele of Cao E has survived.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

85

the mutual reflections and the variations of [strokes and components]. Only when emotional states can arise and configurative forms can be set up [in one composition], can this start to be called calligraphy. The Essential Discussions on Teaching [the Technique of] the Brush by Han Fangming (fl. end of the eighth century) of the Tang (618-907) says: “Before writing, it is necessary to think properly and examine the phrases and sentences for the sheet of paper one is going to write, how many words are included, the colour and the shape of the paper, and the type of script that conforms to the present ones. The standard, the semi-cursive or the cursive [scripts] may all be appropriate for the paper [used]. In case there are characters that are difficult to write, it is necessary to arrange them in advance within one’s mind.” 89 I have here selected the best examples amongst the surviving inscriptions from the Han and Wei onwards, as well as from Wei and Tang times. [These works in] the standard, the semi-cursive, and the cursive scripts are arranged according to their [own] category. I have listed them in [circa] ten levels, and they are recorded as follows. […]

4.7 Distinguishing the Scripts 辯體第七

自鳥蹟科鬥之後,創制大、小二篆。二篆之後,始有隸法。鍾、王以來又復變爲今體,爲之真楷。隸以降乃有行押之變,又爲草書。世有後先,體多殊異,皆爲論著,所以各體可知矣。90

After the [written signs of the] imprints of birds and [characters resembling] tadpoles, the major and lesser zhuan scripts were created and regulated. After the two zhuan scripts it appeared for the first time the clerical script. Since Zhong [You] and Wang [Xizhi] this changed again into the modern script, making it the correct standard script. After the clerical script, the variation of the semi-cursive occurred, which eventually became the cursive script. The order of succession of the ages [of calligraphy], [as well as] the great differences of scripts have all been treated in books, whereby scripts can be learned.

4.8 Denominations [of Brush-strokes] 名稱第八

八法之變,形狀不同,古人遺蹟往皆有名稱,如蹲鴟、隼尾之類。其法甚多,今爲蒐訪類聚,略其用筆之旨,學者庶有考焉。91

89 Text included in Shu yuan jinghua, juan 20. 90 Fashu tongshi, 78-79.

Pietro De Laurentis

86

As for the variations of the eight methods and the dissimilarities of shapes and forms, in the compositions of the ancients there are denominations such as the squatting kite, and the hawk’s tail. Their techniques are extremely numerous, hereby they are sought and collected, outlining the principles of their brushwork [methods], with the hope that the students might take reference from them.

4.9 Efficient Tools 利器第九

上古無筆墨,以竹挺[i.e. 梃]點漆,書於竹木之上。竹剛漆膩,畫不能行,首重尾輕,形如科斗,故曰科斗書。後世筆墨既有,書學日盛,字體屢更。學者必求筆墨之良者用之,又知所以用之之道,方可致力而臨池之功成。於是錄前人之餘論,以爲此篇雲。92

In the remote antiquity there was no brush nor ink. By dipping a bamboo stick into lacquer-paint people wrote onto bamboo and wood. The bamboo [stick] was hard and the lacquer-paint was greasy, therefore [the act of] tracing [strokes] could not proceed [smoothly], the head of characters was heavy, whereas the tail was light, [so that] the shape [of strokes] resembled that of tadpoles, and therefore [this type of writing] was called tadpole script (kedoushu).93 In later times, after the appearance of brush and ink, the study of writing developed day by day, and the form of characters repeatedly varied. Students must search for refined brushes and inks and use them, as well as they have to know the technique of using them, so that the skill of practising calligraphy can reach perfection through one’s endeavours. Thus, I have recorded here the extant discussions from the ancients by making this chapter which goes […]

4.10 Summarizing Discussions 總論第十

通釋之作共得十篇,屬辭比事,以類相從。至於眾舉傍通,提綱會要,論博義廣,莫得而拘者,萃爲此篇。蓋又爲諸篇之綱要也。94

91 Ibid., 87. 92 Ibid., 90-91. 93 Passage very similar to the incipit of the Collection for Studying the Ancient

[Calligraphic Models] (Xuegu bian 學古編 ), quoted in Tsun-hsuin Tsien 2004:188. Included in the Yimen guangdu, juan 30.

94 Fashu tongshi, 90-91.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

87

The work Comprehensive Explanations reaches in total ten chapters [of length]. It creates entries and arranges topics which follow one another in an ordered sequence. As for the presentation of the multitude of topics and the thoroughness and exhaustiveness of the content, the exposition of fundamentals and the assembling of essentials, the discussions [included] are extensive and the meaning [expressed] comprehensive. Those [items] which I have obtained, but were [previously] included, are collected in this chapter, which can also act as an example for all the others.

Fig. 1

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

89

REFERENCES ACKER, William, Some T’ang and pre-T’ang Texts on Chinese Painting, Leiden: E.J.

Brill, 1954. BARNHART, Richard, “Wei Fu-jen’s Pi Chen T’u and the Early Texts on

Calligraphy,” Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America 18, 1964: 13-25. CHANG Bide 昌彼德 et al. (eds.), Mingren zhuanji ziliao suoyin 明人傳記資料

索引 [Index to Biographical Materials on Ming Figures], Taibei: Guoli zhongyang tushuguan, 1965, rpt.,1978.

�� Songren ziliao zhuanji suoyin 宋人傳記資料索引 [Index to Biographical Materials of Song Figures], 6 vols.,Taibei: Dingwen shuju, 1976.

CHEN Si 陳思 (fl. first half of the thirteenth century) comp., Shu yuan jinghua 書苑菁華 [Anthology of the Calligraphy Garden], 20 juan, prior to 1237, Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2003.

CHEN Yuan 陳垣 (1880-1971) comp., Ershi shi shuo run biao 二十史朔閏表 [Table for a Historical Calendar of Twenty Dynasties], Beijing: Beijing daxue yanjiusuo guoxuemen, 1926, rpt., Beijing: Guji chubanshe, 1956.

DE LAURENTIS, Pietro (畢羅), “Sun Guoting zhi zhiqi: Shu pu wenti kao” 孫過庭之志氣:書譜文體考 [Sun Guoting’s Aspirations through his Shu pu: A Study on the Literary Form of the Manuscript], Yishushi yanjiu 藝術史研究 10, 2008: 107-130.

�� “Sun Guoting shengping kao” 孫過庭生平考 [A Study on the Life of Sun Guoting], Shufa congkan 書法叢刊 [Journal of Calligraphy] 108 2009.3:73-81.

�� “Cong yongzi ba fa shuoqi: gudai shufa zhong hanzi yu bihua de guanxi chutan” 從“永字八法”說起:古代書法中漢字與筆畫的關係初探[The Eight Methods of the Character Yong: The Relation between Characters and their Strokes in Classical Chinese Calligraphy], in Sun Xiaoyun 孫曉雲 and Xue Longchun 薛龍春 (eds.), Qing xun qi ben: gudai shufa chuangzuo yanjiu guoji xueshu taolunhui lunwenji 請尋其本:古代書法創作研究國際學術 討論會 論文集 [Let us Turn to the Origin: Proceedings from the International Symposium on the Creative Process in Classical Chinese Calligraphy], Nanjing: Nanjing daxue chubanshe, 2010: 51-69.

�� “On the Forbidden Classic of the Jade Hall (Yutang jin jing 玉堂禁經), an Eleventh Century on Calligraphic Technique”, Asia Major 24.2 2011 (forthcoming).

Pietro De Laurentis

90

FENG Wu 馮武 (d. 1627), Shu fa zheng zhuan 書法正傳 [Correct Commentaries on Calligraphy], Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 1985.

FENGHUANG CHUBANSHE 鳳凰出版社 (ed.), Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng-Shandong fu xian zhi ji 中國地方志集成-山東府縣志輯 [Collectanea of Chinese Gazzetteers-Compilation of Gazzetteers from the Prefectures and the Counties of Shandong], 95 vols., Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe, 2004.

FRANKE, Wolfgang, An Introduction to the Sources of Ming History, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore: University of Malaya Press, 1968.

GE Shouzhi 戈守智, (courtesy name Hanxi, 1720-1786), Hanxi shufa tongjie 漢谿書法通解 [Hanxi’s Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy], 8 juan, Tianjin: Tianjin guji shudian, 1984.

GOODRICH, L. Carrington, and Chao-ying Fang (eds.), Dictionary of Ming Biography 1368-1644, New York: Columbia University Press, 1976.

GU Zuyu 顧祖禹, (1631-1692) comp., Du shi fangyu jiyao 讀史方輿紀要 [Essential Records of Geography from Historical Sources], 130 juan, 5 vols., Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2005.

HUANG Dun 黄惇, Zhongguo shufa shi – Yuan Ming juan 中國書法史-元明卷 [History of Chinese Calligraphy, Yuan and Ming Volume], Nanjing: Jiangsu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2001.

HUMMEL, Arthur W. (ed.), Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period (1644-1912) Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1943-1944, rpt., Taibei: Ch’eng-wen Publishing Company, 1967.

INSTITUTS RICCI (ed.), Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise, 8 vols., Paris-Taibei: Instituts Ricci 2001.

JI Yun 紀昀 (1724-1805) et al., Siku quanshu zongmu tiyao 合印四庫全書總 目提要及四庫未收書目禁燬書目 [Attached Edition of the Abstracts of the General Index of the Complete Collection of the Four Deposits and of the Catalogue of Books not Included in the Complete Collection as well as of those Prohibited and Destroyed], 5 vols., Taibei: Taiwan yinshuguan, 1971.

KANDA Kīchirō 神田喜一朗 and Tanaka Yoshimi 田中親美 (eds.), Shodō zenshū 書道全集 [Complete Collection of Calligraphy], 28 vols., Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1954-1968.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

91

LIANG Piyun 梁披雲 (ed.), Zhongguo shufa dacidian 中國書法大詞典 [Great Terminological Dictionary of Chinese Calligraphy], 2 vols., Hong Kong: Shu pu chubanshe, 1984.

LIU Tao 劉濤 (ed.), Zhongguo shufa quanji 18-19 Wang Xizhi, Wang Xianzhi 中國書法全集 18-19 王羲之、王獻之 [Complete Collection of Chinese Calligraphy Vols. 18-19: Wang Xizhi (303-361) and Wang Xianzhi (344-386)], Beijing: Rongbaozhai, 1991, rpt., 1997.

LOEWE, Michael and Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

LU Fusheng 盧輔聖 (ed.), Zhongguo shuhua quanshu 中國書畫全書 [Complete Texts on Chinese Calligraphy and Painting], 14 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 1992-1999.

��, (ed.), Zhongguo shuhua wenxian suoyin 中國書畫文獻索引 [Index to Texts on Chinese Calligraphy and Painting], 2 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2005.

LUO Zhufeng 羅竹風 (ed.), Hanyu dacidian 漢語大詞典 [Great Dictionary of the Chinese Language], 13 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai cishu chubanshe, 1994.

MOROHASHI Tetsuji 諸橋轍 (ed.), Dai Kanwa jiten 大漢和辞典 [Great Chinese-Japanese Dictionary], 13 vols., Tokyo: Taishūkan shoten, 1957-1960.

NI Tao 倪濤 (fl. eighteenth century), Liu yi zhi yi lu 六藝之一錄 [Records of One of the Six Arts], Siku quanshu edn., 406 juan, 9 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1991.

PAN Yungao 潘運告 (ed.), Mingdai shu lun 明代書論 [Calligraphy Treatises of the Ming], Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 2002.

QIU Xigui 裘錫圭, Wenzixue gaiyao 文字學概要 [Introduction to (Chinese) Grammatology], trans. Mattos, Gilbert and Norman, Jerry, Chinese Writing, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

SUN Yueban 孫岳頒 (1639-1708) et al. (eds.), Peiwenzhai shuhua pu 佩文齋書畫譜 [Catalogue of Calligraphy and Painting from the Peiwen Study], Siku quanshu edn., 100 juan, 1708, 5 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1991.

TAN Qixiang 譚其驤 (ed.), Zhongguo lishi ditu ji 中國歷史地圖集 [Historical Atlas of China], 8 vols., Beijing: Cartographical Publishing House, 1982-1987, rpt. 1996.

Pietro De Laurentis

92

TANIMURA Kisai 谷村憙齋, Tō Son Katei Sho hu – Shakubun kaisetsu 唐孫過庭書譜-釋文解説 [Transcription and Examination of the Shu pu by Sun Guoting of the Tang], Tokyo: Nigensha, 1979.

TAO Zongyi 陶宗儀 (fl. half of the fourteenth century), Shu shi hui yao 書史會要 [Essentials of the History of Calligraphy], Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1984.

TIAN Jizong 田繼綜 (ed.), Bashijiu zhong Mingdai zhuanji zonghe yinde 八十九種明代傳記綜合引得 [Combined Indices to Eighty Nine Collections of Ming Dynasty Biographies], 3 vols., Beiping: Harvard-Yanching Institute, 1940, rpt., Taibei: Ch’eng-wen Publishing Company, 1966.

TIANJIN TUSHUGUAN 天津圖書館 (ed.), Gaoben guji shanben shumu shuming suoyin 稿本古籍善本書目書名索引 [Draft Version of the Index of Rare Editions of Books], 3 vols., Jinan: Qi Lu shushe, 2003.

TSIEN Tsun-hsuin, Written on Bamboo and Silk, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962.

TWITCHETT, Denis and Mote, Frederick (eds.), The Cambridge History of China vol. 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, pt.2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

WILKINSON, Endymion, Chinese History: A Manual, Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard Asia Center, Harvard University Press, 2000.

WANG Yunwu 王雲五 (ed.), Congshu jicheng chubian 叢書集成初編 [First Series of the Collection of Collectanea], 3467 vols., Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1935-1937.

WU Kuang-ch’ing, “Ming Printing and Printers,” in Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 7.2 (February 1943): 203-260.

YE Junqing 葉俊慶, Zhou Lüjing ji qi Yimen guangdu yanjiu 周履靖及其《夷門廣牘》研究 [A Study on Zhou Lüjing and his Yimen guangdu], unpublished master thesis, Taibei: Zhongzheng daxue, 2007.

YU Shaosong 余紹宋 (1882-1940), Shu hua shulu jieti 書畫書錄解題 [Bibliographical Explanation of Recorded Texts on Calligraphy and Painting], 1932 edn. rpt. with addenda, Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2003.

YU Yu’an 于玉安 (ed.), Zhongguo shufa lunzhu huibian 中國書法論著匯編 [Collection of Texts on Chinese Calligraphy], 10 vols., Tianjin: Tianjin guji chubanshe, 1999.

Zhang Shen’s Fashu Tongshi

93

ZHANG Shen 張紳 (fl. half fourteenth century), Fashu tongshi 法書通釋 [Comprehensive Explanations on Calligraphy], 3 juan, in Yimen guangdu, juan 4, in Wang Yunwu 1936, 1621: 1-108, Lu Fusheng 1993, 3: 307-322.

ZHANG Tiangong 張天弓, “Lüe lun Zhongguo gudai shufa lilun piping zijue de wenti” 略論中國古代書法理論批評自覺的問題 [Brief Discussion on the Question of Critical Consciousness in Chinese Calligraphy Ancient Theory], in Zhongguo shufa 中國書法 [Chinese Calligraphy] (2000-12): 60-64.

ZHANG Tingyu 張廷玉(1672-1755) et al. comp., Ming shi 明史 [History of the Ming], 332 juan, 1736, Beijing: Zhonghua, 1974.

ZHANG Yanyuan 張彥遠 (ca.817-ca.877) comp., Fashu yao lu 法書要錄 [Essential Records on Calligraphy], 10 juan, ca. 840s, Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe, 1964. rpt., 2003.

Zhongguo guji shanben shumu bianji weiyuanhui 中國古籍善本書目 編輯委員會 (ed.), Zhongguo guji shanben shumu shuming suoyin-zibu 中國古籍善本書目 -子部 [Index to Rare Editions of Chinese Ancient Books-Philosophers’ Section], 2 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1994.

ZHOU Junfu 周駿富 a) (ed.), Mingdai zhuanji congkan 明代傳記叢刊 [Collected Publications of Ming Dynasty Biographies], 160 vols., Taibei: Mingwen shuju, 1991.

�� b) (ed.), Mingdai zhuanji congkan suoyin 明代傳記叢刊索引 [Index to the Collected Publications of Ming Dynasty Biographies], Taibei: Mingwen shuju, 1991.

ZHOU Lüjing 周履靖 (fl. second half of the sixteenth century), Yimen guangdu 夷門廣牘 [Broad Titles from the Seclusive Residence] in Yingyin Yuan Ming shanben congshu shi zhong 景印元明善本叢書十種, 109 juan, 1597, Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, n.d..

ZHU Changwen 朱長文 (1039-1098) comp., Mochi bian 墨池編 [Collection of the Ink Pond], 6 juan, 1066, 2 vols., Taibei: Zhongyang tushuguan, 1970.