Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

Transcript of Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

Manufacturing techniques of Olivapendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

Emiliano R. MELGAR

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 216

2007). During the Classic period (AD 200-650), thistendency continued in Teotihuacan, where manyshell objects have been recovered in different partsof the city (Kolb 1987). Therefore, it is not surprisingthat 2532 archaeological shell artefacts were foundat Xochicalco (Fig. 1a), an important fortified site inthe state of Morelos that dates back to theEpiclassic period (AD 650-900) (Sáenz 1963, 1967).This great quantity of shell materials, mostly of mari-ne origin, is noteworthy because the site is locatedon a series of hills in the Morelos Valley, more than

MUNIBE (Suplemento/Gehigarria) nº 00 000-000 DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIÁN 2003 ISSN XXXX-XXXXMUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria nº 31 216-225 DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIÁN 2010 D.L. SS-1055-2010

ABSTRACT

At the Epiclassic (AD 650-900) site of Xochicalco, in the Western Valley of Morelos, México, archaeologists have recovered an abundanceof Oliva shell pendants (also known as tinklers). These pendants had once formed necklaces and were placed in the most ancient offerings insi-de the main structures of the settlement. Through experimental archaeology and the analysis of manufacturing traces using Optic Microscopy(OM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), I identified the different tools and techniques employed in shell production. Surprisingly, thependants presented three different technologies, despite the fact that they were part of the same necklace and offering. This heterogeneity pro-bably reflects different working groups or shell workshops, especially when considering that, in the later stages of the site, the shell objects pre-sent a stronger standardisation in their manufacture and seem all to come from one shell workshop at the Acrópolis in the Main Plaza.

RESUMEN

En el sitio Epiclásico (650-900 d.C.) de Xochicalco, en el Valle Oeste del estado de Morelos, diferentes arqueólogos han recuperado obje-tos de adorno elaborados a partir de caracoles de diferentes especies de Oliva (también conocidos como cascabeles), varios de ellos for-mando sartales en las ofrendas más antiguas enterradas en sus estructuras principales. A través de la arqueología experimental y el análisisde huellas de manufactura con Microscopía Óptica (MO) y Microscopía Electrónica de Barrido (MEB), pude identificar las diferentes herra-mientas y técnicas empleadas en la elaboración de las piezas. Llama la atención la identificación de la utilización de tres tecnologías diferen-tes para su elaboración, sin importar si formaban parte de un mismo sartal u ofrenda. Probablemente esta heterogeneidad se debe a que fue-ron producidos por distintos grupos de artesanos o talleres de concha, ya que en las etapas más tardías del asentamiento los objetos presen-tan una marcada estandarización tecnológica en su manufactura y que solo existe un taller de concha ubicado en la Acrópolis de la PlazaPrincipal.

LABURPENA

Xochicalco leku Epiklasikoan (K.o. 650-900), Morelos estatuko mendebaldeko bailaran, arkeologoek Oliva espezieko barraskiloz (cascabelizenez ere ezagunak) egindako apaingarriak berreskuratu dituzte, egitura nagusietan lurperatutako eskaintzak, sortak osatzen dituztela.Arkeologia esperimentalaren eta manufaktura-arrastoak Mikroskopia Optiko (MO) eta Ekorketako Mikroskopia Elektroniko (EME) bidez aztertuz,piezak egiteko erabiltzen zituzten tresnak eta teknikak identifikatu ahal izan dira. Deigarria da apaingarriak egiteko hiru teknika desberdin era-biltzen zituztela, sorta berekoa izan ala ez. Agian, heterogeneotasun horrek esan nahi du zenbait artisauk egin zituztela edo zenbait maskor-tai-lerretan egin zituztela, kokalekuko etapa berantiarrenetan, objektuen manufakturan estandarizazio teknologiko nabarmena ageri baita eta mas-kor-tailer bakarra baitago Plaza Nagusiko Akropolian.

Emiliano R. MELGAR(1)

(1) Museo del Templo Mayor, Seminario 8, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc, México D.F., C.P. 06060 ([email protected]).

1. INTRODUCTION

Shell productions were highly valuable prestigegoods for, Mesoamerican groups, especially forthose living inland, far away from the coasts, due totheir foreign, rare and exotic character (Hohmann2002: 4, Moholy-Nagy 1995: 7, 8). During theMiddle pre-Classic period (1200-400 BC), greatamounts of shell objects were used to visually mani-fest prestige and hierarchies within the settlements,as is the case in Teopantecuanitlán, Guerrero (Solís

Manufacturing techniques of Olivapendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

Técnicas de manufactura de colgantes de Olivaen Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

KEY WORDS: Shells, pendants, Epiclassic, manufacture, Xochicalco. PALABRAS CLAVE: Caracoles, objetos de adorno-colgantes, Epiclásico, manufactura, Xochicalco.GAKO-HITZAK: Barraskiloak, belarritakoak, Epiklasikoa, manufaktura, Xochicalco.

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 217

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010

two hundred kilometres away from the PacificOcean coastline and more than three hundred kilo-metres away from the Gulf of Mexico. Moreover,these distances would have been even greatergiven the prominent mountain slopes betweenXochicalco and the coasts, and the fact that circu-lation routes between the littoral and the CentralHighlands followed the major rivers, like the Balsasriver in the Pacific and the Blanco river in the Gulf ofMexico (Kolb 1987). These long distances likelyincreased the value of shells and esteem for them,as seems to be witnessed by the fact that most ofthe molluscs were found associated with offeringsand tombs in the main structures. In addition, shellswere found in middens that resulted from the lootingand destruction of the most important part of the set-tlement before it was abandoned around AD 900-1000 (Garza and González 1995: 100, 2006: 125).

Of the shells recovered at Xochicalco, the pen-dants made out of the Oliva genus stand out forbeing the most ancient malacological ornaments(AD 650) that were placed in offerings (Fig. 1b).They, moreover, present the widest distributionwithin the site and are the only recycled objects sub-sequently used to elaborate inlays in the later con-texts of the site (AD 750-900). For these reasons, itwas relevant to determine what species had beenused, from which littoral they came and what kind ofobjects were made out of them.

2. TAXONOMY AND TYPOLOGY

The shells´ taxonomical identification was con-ducted before undertaking a typological analysis.Taxonomical identification is based on the work ofMyra Keen (1971) for Pacific species and that ofTucker Abbott (1982) for Caribbean ones. Themollusc reference collection of the Laboratory of

Paleozoology at the INAH in Mexico City was usedas well, with the guidance of specialists such asbiologists Belem Zúñiga and Norma Valentín. Themorphological and functional typological analysisfollows the frame proposed by Lourdes Suárez(1977) and Adrián Velázquez (1999).

Three hundred Oliva pieces belonging to fivedifferent species were analyzed (Fig. 2), represen-ting 11.86% of the total assemblage and 18.66%of the shell objects. Four species are from thePanamic-Pacific malacological province: Olivajulieta, O. incrassata, O. porphyria and O. splendi-dula, which extends from the Sea of Cortés to theNorth of Perú (Keen 1971). An additional species,O. sayana, originates from the Caribbean Seawhich includes part of the Gulf of Mexico, Florida,and all of the Antilles, as well as the Atlantic coastof Central America, Colombia, Venezuela and nor-thern Brazil (Abbott 1982).

218

S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

EMILIANO R. MELGAR

Figure 2. Oliva species identified: O. splendidula, O. sayana, O. porphyria,O. incrassata and O. julieta.

Figure 1. The localization of Xochicalco in Mexico (a) and the shell offerings at the site (b).

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 218

The 290 Oliva shell objects (fig. 3) were classi-fied into two functional groups: ornaments and evi-dences of production. These were sub-dividedinto three categories: pendants, recycled pen-dants, and inlays as well as into two families, auto-morphic (the pieces which man-made modifica-tions do not change too much the original shape ofthe mollusc) and xenomorphic (the pieces whichman-made modifications do not maintain the origi-nal shape of the mollusc) and twelve types, full,spireless, half spireless, quadrangular, rectangu-lar, triangular, trapezoidal, band, tooth, eccentric,undetermined, and debitage (table 1). The distri-bution of the shell objects showed seven majorconcentrations: one in the Acrópolis and derivedcontexts (Elements 1 and 77 of the Sector B, andthe Drainage of the Sector A), other in the PlumedSerpents´ Pyramid, another in the Element 46 atthe Structure 6 in Sector G, another one in the twotemples of the Sector H, other in the Sector Museo,other one in the Altar at Sector I and the last one atthe entrance of the site in Sector Loma Sur (Fig. 4).

3. TECHNOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

The data about what shell species were usedto manufacture what kind of objects show that O.

219Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010 S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

Figure 3. Objects and debris from Oliva shells: spireless pendants (a and c), debitage (b and f), geometric inlays (d and e), and complete automorphic pendants (g).

Figure 4. Spatial distribution and quantity of Oliva pieces at Xochicalco (Mapcourtesy of the Xochicalco Project).

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 219

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010

porphyria was preferentially used for elaboratingfull pendants in the earliest offerings (AD 650).Furthermore, these pendants were the only onesrecycled and re-used for inlays in the later con-texts (AD 750-900). Also noticeable is the factthat, in each string there are pendants with diffe-rent type of holes.

In order to distinguish the shape and quality ofsuch perforations, it was necessary to perform atechnological analysis through experimentalarchaeology and manufacturing analysis rese-arch. According to the uniformity criteria of theexperimental archaeology (Ascher 1961: 807), theproduction activities are normative in human

220

S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

EMILIANO R. MELGAR

Table 1. Type, quantity and provenance of the shell objects

Category of object Type of object Species Number of pieces ContextsPendants

Complete Oliva porphyria 50 Sector G, Plumed Serpents´ Pyramid“ ” “ ” 1 Sector E, Structure 2“ ” “ ” 36 Sector H, Structure C“ ” “ ” 15 Sector H, Structure E“ ” “ ” 6 Sector I, Altar“ ” “ ” 5 Sector Acrópolis, sub-Structure“ ” Oliva incrassata 2 Sector G, Plumed Serpents´ Pyramid“ ” Oliva julieta 1 Sector G, Plumed Serpents´ PyramidSpireless Oliva julieta 2 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1W“ ” Oliva incrassata 2 Sector G, Element 46“ ” Oliva splendidula 1 Sector A, Central Zone“ ” “ ” 1 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1W“ ” Oliva sayana 1 Sector B, Courtyard 2“ ” “ ” 1 Sector I, Altar

Half spireless Oliva porphyria 1 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1WUndetermined “ ” 1 Sector B, Element 1“ ” “ ” 1 Sector B, Element 77“ ” “ ” 12 Sector Museo, Structure 2“ ” “ ” 1 Sector H, Structure 7“ ” Oliva sayana 1 Sector Museo, Structure 2“ ” Oliva sp. 1 Sector Museo, Structure 2

Inlays Quadrangular Oliva porphyria 2 Sector B, Element 1“ ” 1 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1E

Rectangular “ ” 2 Sector B, Element 1“ ” “ ” 2 Sector B, Element 77“ ” “ ” 2 Sector A, Drainage“ ” “ ” 1 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1WTriangular “ ” 2 Sector B, Element 1“ ” “ ” 3 Sector B, Element 77

Trapezoidal “ ” 1 Sector A, DrainageTooth “ ” 1 Sector B, Element 1Band “ ” 1 Sector A, Drainage

Undetermined “ ” 1 Sector A, DrainageRecycled pendants Debitage Oliva porphyria 5 Sector Acrópolis, Structure 7

“ ” “ ” 12 Sector A, Drainage“ ” “ ” 23 Sector B, Element 1“ ” “ ” 20 Sector B, Element 77“ ” “ ” 3 Sector B, Courtyard 2“ ” “ ” 26 Sector G, Element 46“ ” “ ” 1 Sector H, Structure C“ ” “ ” 3 Sector Loma Sur, Structure 1W“ ” “ ” 29 Sector Museo, Structure 2“ ” Olivas sp. 1 Sector Museo, Structure 2“ ” “ ” 1 Sector A, Drainage“ ” “ ” 2 Sector G, Element 46

Oliva sayana 3 Sector Museo, Structure 2Total 290

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 220

societies, and artifacts are produced and usedfollowing rules that determine what specific featu-res each object has. As a result, the use or pro-duction of similar objects, elaborated under thesame rulings, should be characterized by identi-cal attributes (Ascher 1961: 793, Velázquez2007:7). Therefore, standardised attributes indica-te the use of a certain tool, made from a determi-ned material, employed in a specific manner andunder certain conditions, all of which will leavecharacteristic and distinguishable traces on theworked materials, in this case, shells (Binford1991: 22, Velázquez 2007: 7).

Since 1997, following this uniformity criteria, thesame tools and manners are being reproduced atthe Experimental Archaeology Shell Workshop inthe Templo Mayor Museum with more than 600experiments (Fig. 5), with similar tools as thoserecorded in several historical sources and archaeo-logical contexts, which were supposedly used bythe various groups in pre-Hispanic México. Suchtools are flakes and blades of obsidian and chert,grindstones made of basalt, andesite, riolite, limes-tone, sandstone, granite, and slate, among others(Velázquez 2007: 57–58).

Subsequently, the resulting traces of manufac-ture were compared with the archaeological mate-rial on three levels: macroscopic, stereoscopicmicroscopy (10X, 30X and 63X), as well asScanning Electron Microscopy, or SEM (100X,300X, 600X and 1000X).

All of the archaeological pieces (290) werechecked macroscopically and stereoscopicallyand compared with the experimental ones drilledwith flakes (obsidian and chert burins) and abrasives(sand, volcanic ash, powder of obsidian, and powderof chert) and reed, obtaining the following results (fig. 6):

1) Seven pendants had conical perforationswithout visible striations; they are similar to thoseones drilled with abrasives.

2) Nineteen pendants had circular striations inthe conical perforation, they match with those onesdrilled with flakes.

3) Thirty-one pendants showed regular perfo-rated edges with lines, they are similar to thoseones drilled with flakes.

4) One-hundred-and-ten pendants had irregu-lar edges with lines, they are similar to those onesdrilled with flakes.

5) One-hundred-and-eight pieces (inlays, pen-dants and recycled pendants) showed parallel stria-tions; they are similar to those ones cut with flakes.

For the analysis with the SEM, thirty pendantswere chosen based on their good preservationand the representativeness of their modifications,four from each context, except two contexts thathad only one piece (Sector A and Sector E). Fivepatterns were identified (Fig. 7):

1) Five pieces presented walls that were pier-ced by lines measuring approximately 1.3 µmwide, which united to form greater strokes, similarto the experimental perforations that had beenmade using sand and reed (Fig. 7a-b).

2) Nine pierced pieces showed fine lines mea-suring two µm, which resembled perforationsmade with obsidian flakes (Fig. 7c-d).

3) Nine pendants showed parallel bands oftwo to four µm, which are similar to drill holes madewith chert burins (Fig. 7e-f).

4) Four presented walls that were crossed byfine lines measuring two µm, which resembled chan-neled perforations produced with obsidian flakes.

5) Three recycled pendants and inlays werealso analyzed with Stereoscopic Microscopy andSEM. They revealed well defined parallel linesresulting from cuts made with stone tools; but the

221Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010 S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

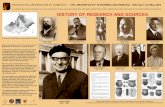

Figure 5. Experimental archaeology on shell pieces (drawing by Julio Romero).

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 221

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010

re-used pendants also showed flanges becausetheir cuts were not regularized. With the SEM, allcases revealed walls that were crossed by finelines measuring about two µm resembling cutsmade with obsidian flakes.

Also, all of these traces are different if we com-pared them with other tools like powder of chert andreed or volcanic ash and reed (Fig. 7g-h).

4. DISCUSSION

Based on this information, it is clear that a greatdiversity of tools and techniques was used to pier-ce and perforate the Oliva pendants, whose distri-

bution did not influence the conformation of eachstring in the earliest offerings. This could be a resultof different groups of artisans or workshops thatproduce them, perhaps without any control by theelite. In contrast, only the O. porphyria pendantswere re-used and recycled for inlays and all exhibitcuts made with obsidian flakes. The homogeneityof this technique coincides with the existence of acentralized workshop located in the Acrópolis,where the remaining shell objects analyzed withstereoscopic microscopy and SEM reflect a notice-able standardisation of tools and techniques: shellwas abraded with basalt, cut with obsidian flakes,and drilled with chert burins (Melgar 2007).

222

S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

EMILIANO R. MELGAR

Figure 6. Stereoscopical comparison between experimentally drilled holes and archaeological ones: (a and b) using obsidian flakes; (c and d) using sand and reed;(e and f) edge made using obsidian flakes.

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 222

223Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010 S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

Figure 7. SEM comparisons between experimentally drilled holes and archaeological ones: (a and b) using sand and reed; (c and d) using obsidian flakes; (e andf) using chert burins; (g) using powder of chert, (h) and using volcanic ash with reed.

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 223

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010

In addition, this analysis suggests that thewider distribution of Oliva pendants is a directresult of the fact that their production is less timeand work consuming (2-15 hours of work) than thatof other objects, such as inlays, beads, and pen-dants (50-100 hours of work).

Finally, attention is drawn to the fact that theonly type of shell object which was re-used or recy-cled in the site is pendants. The xochicalcasreworked these pendants with transversal and lon-gitudinal cuts that required much more time thanduring the production of the original object.However, none of the inlays were placed as offe-rings and they were treated more like garbage. Alikely explanation may be that the pendants, whichmay have once been the prized possession ofwarriors, were reworked as a gesture of desecra-tion. This is consistent with the more general pat-tern observable during the final years of the site'soccupation, before the last great pillage and fire.At that time, there are evidence of conflicts bet-ween the leading groups and the destruction ofobjects of power such as the iconographicallyreliefs which were covered with stucco (Garza andGonzález 2005: 202).

5. CONCLUSIONS

As it has been observed, the automorphicpendants made, as prestige goods, out of variousspecies of Oliva, mostly originating from shorelinesof the Pacific Ocean, are the most ancient shellobjects placed in offerings at Xochicalco.

Each string of pendants displays different per-foration manufacturing techniques. Thanks toexperimental archaeology and the analysis ofmanufacturing traces using stereoscopic micros-cope and a scanning electron microscope, it waspossible to identify three different processesemployed in the elaboration of these pieces: sandwith reed, chert burins and obsidian flakes. Thisheterogeneity of tools used to produce the samemodification could be a result of different groups ofartisans or workshops that made them, probablywithout any control by the elite. It also contrastswith a standardisation of tools identified in the latercontexts, where all objects were abraded withbasalt, cut with obsidian flakes and drilled withchert. In this way, only the inlays made from re-used pendants match this manufacturing ten-dency, all being cut with obsidian. Also these pen-dants stand out for being the only shell objects re-used at the site, possibly as a desecration ofwarrior insignias, as a reflection of conflicts opera-

ting then among leading groups, before the finalabandonment of the site.

Finally, it is important to stress the necessity ofthis kind of study for other shell material collec-tions in order to identify manufacturing patternsand to infer aspects of production and organiza-tion, and perhaps styles and technological tradi-tions across time.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We address special thanks to Silvia Garza,Norberto González, Claudia Alvarado, AdriánVelázquez, and all the members of the XochicalcoProject and the Experimental Archaeology ShellWorkshop to Norma Valentín, Belem Zuñiga, andAntonio Alva, and finally Ana Laura Solís, VictorSolís, Kim Richter, for their comments and sugges-tions Virginia Fields, Bruce Bradley and VictoriaStosel for helping us with the English translation.

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABBOTT, R. T.1982 Kingdom of the Seashell. Bonanza Books, New York.

ASCHER, R.1961 “Experimental Archaeology”. American Anthropologist, 63

(4): 793–816.

BINFORD, L.1991 Bones, ancient men, and modern myths. Academic

Press, London.

GARZA, S. & GONZÁLEZ, N.1995 “Xochicalco”. In: Wimer, J. (Ed.): La Acrópolis de

Xochicalco. Instituto de Cultura de Morelos, Cuernavaca:89–144.

1998 “La Pirámide de las Serpientes Emplumadas”.Arqueología Mexicana, V (30): 22–25.

2005 “Un marcador en Xochicalco, Morelos”. In: Benavides, A.,Manzanilla, L. & Mirambell, L. (Coords.): Homenaje aJaime Litvak. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México:195–203.

2006 “Cerámica de Xochicalco”. In: Merino Carrión, L. & GarcíaCook, A. (Eds.): La producción alfarera en el México anti-guo. Volumen III. La alfarería del Clásico tardío (700-1200d.C.). Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia,México: 125–159.

HOHMANN, B. M.2002 Preclassic Maya Shell Ornament Production in the Belize

Valley, Belize. PhD, The University of New Mexico.Albuquerque. (unpublished).

KEEN, M.1971 Sea Shells of Tropical West America. Stanford University

Press, Stanford.

224

S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

EMILIANO R. MELGAR

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 224

KOLB, C. C.1987 Marine Shell Trade and Classic Teotihuacan, Mexico. BAR

International series, 364.

MELGAR, E.2007 “Las ofrendas de concha de moluscos de la Pirámide de

las Serpientes Emplumadas, Xochicalco, Mor”. RevistaMexicana de Biodiversidad, 78: 83–92.

MOHOLY-NAGY, H.1995 “Shells and Society at Tikal, Guatemala”. Expedition, 37

(2): 3–12.

SÁENZ, C. A.1963 “Exploraciones en la Pirámide de las Serpientes

Emplumadas, Xochicalco”. Revista Mexicana de EstudiosAntropológicos, 19: 7–25.

1967 Nuevas Exploraciones y Hallazgos en Xochicalco 1965-1966. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia,México.

SOLÍS, R. B.2007 “Los objetos de concha de Teopantecuanitlán, Guerrero:

Análisis taxonómico, tipológico y tecnológico de un sitiodel Formativo”. Bachelor, Escuela Nacional deAntropología e Historia en México.

SUÁREZ, L.1977 Tipología de los objetos prehispánicos de concha.

Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México.

VELÁZQUEZ, A.1999 Tipología de los objetos de concha del Templo Mayor de

Tenochtitlan. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia,México.

2007 La producción especializada de los objetos de conchadel Templo mayor de Tenochtitlan. Instituto Nacional deAntropología e Historia, México.

225Manufacturing techniques of Oliva pendants at Xochicalco (Morelos, México)

MUNIBE Suplemento - Gehigarria 31, 2010 S.C. Aranzadi. Z.E. Donostia/San Sebastián

munibeconchas21.qxd:munibevertebrados2007.qxd 31/8/10 11:31 Página 225

![Structural characterization and reactivity of Cu(II) complex of p- tert-butyl-calix[4]arene bearing two imine pendants at lower rim](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/631fe67f962ed4ca8e03e9b8/structural-characterization-and-reactivity-of-cuii-complex-of-p-tert-butyl-calix4arene.jpg)

![Adrian Cosmin BOLOG, George BOUNEGRU, About the Bulla Type Pendants Revealed at Apulum [Despre pandantivele de tip bulla descoperite la Apulum]](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/63152aa2511772fe45103cee/adrian-cosmin-bolog-george-bounegru-about-the-bulla-type-pendants-revealed-at.jpg)