J. Bintliff, B. Noordervliet, J. van Zwienen, K. Wilkinson, B. Slapsak, V. Stissi, C. Piccoli and A....

Transcript of J. Bintliff, B. Noordervliet, J. van Zwienen, K. Wilkinson, B. Slapsak, V. Stissi, C. Piccoli and A....

PH

AR

OS

V

OLU

ME X

IX.2 2013

Phar sJOURNAL OF THE NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE AT ATHENS

VOLUME XIX.2 2013

PEETERS

Fieldwork Reports & Studies

97016_Pharos_19_2_Cover.indd 2-497016_Pharos_19_2_Cover.indd 2-4 13/03/14 11:2513/03/14 11:25

CONTENTS

John Bintliff, Bart Noordervliet, Janneke van Zwienen, Keith Wilkinson, Bozidar Slapsak, Vladimir Stissi, Chiara Piccoli & Athanasios Vionis The Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project, 2010-2012 seasons ....................................................................................... 1

Jan Paul Crielaard, Elisabeth Barbetsea, Xenia Charalambidou, Maria Chidiroglou, Mark Groenhuijzen, Maria Kosma & Filiz Songu The Plakari Archaeological Project. Preliminary report on the second field season (2011) .............................................................................................. 35

Torsten Mattern Theisoa (Lavdha). Vorbericht über die Arbeiten 2011 und 2012 ................. 57

Joanita Vroom Digging for the ‘Byz’. Adventures into Byzantine and Ottoman archaeo - logy in the eastern Mediterranean .............................................................. 79

Stuart MacVeagh Thorne, Mieke Prent, Athanassios Themos & Eleni Zavvou Kastraki Keratitsas: preliminary results of the architectural study of an Early Helladic fortification in Laconia ....................................................... 111

Pharos 19(2), 1-34. doi: 10.2143/PHA.19.2.3015344© 2013 by Pharos. All rights reserved.

The Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia project,

2010-2012 seasons

JOHN BINTLIFF, BART NOORDERVLIET, JANNEKE VAN ZWIENEN, KEITH WILKINSON, BOZIDAR SLAPSAK, VLADIMIR STISSI, CHIARA PICCOLI

& ATHANASIOS VIONIS

Abstract

This article summarizes the work undertaken by an international team at the ancient sites of Koroneia, Hyettos, Thespiai, Askra, Haliartos and Tanagra and in their countrysides, during the 2010, 2011 and 2012 seasons. The problems with defining urban infrastructure and bounda-ries at Koroneia are tied to the eventual virtual reality reconstruction of the ancient city at its Hellenistic peak, while geomorphic research has been measuring the effect of settlement on the local landscape around the town. Work at ancient Askra, Haliartos and Thespiai has been carried out in connection with publication of older survey programmes, while continuing geophysical tests outside of the walls of Tanagra city are ongoing to discover the limits of the pre-Roman and much larger town plan.

Keywords

Boeotia – landscape and geoarchaeology – virtual reality – topographic research – ceramic analysis – surface survey.

Introduction

This project completed its last surface ceramic survey collection in 2011 and is now in a phase of studying the finds from previous urban and rural surveys, and adding supplementary material for these surveys through documenting surface architec-ture and undertaking geophysical tests. All these operations are in connection with the final publication of the individual major and minor sites studied by the current project (directed by Prof. John Bintliff and Prof. Bozidar Slapsak, assistant directors Prof. Vladimir Stissi and Dr Athanasios Vionis), and its predecessor the Cambridge-Bradford Boeotia Project (directed by Prof. John Bintliff and Prof. Anthony Snodgrass).

97016.indb 1 13/03/14 10:50

2 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Ceramic surface survey at the ancient city of Koroneia

In the summer of 2011 the Leiden team (led by Prof. Bintliff, Bart Noordervliet and Janneke van Zwienen) with the assistance of an international group of staff and students completed the surface ceramic survey of this ancient city (Figure 1). In 2010-11 we had continued with the gradual infilling of the city hill through a regular grid of approximately 20 x 20 m survey units. Following our previous methods, each such unit is first walked by two students, one crossing the square in a north-south direction, the other east-west, counting the density of surface pottery in a strip 1 m wide by 20 m long. A surface visibility measurement is also taken of these strips to allow correction to more realistic densities. Subsequently the entire square is walked by the students, converging from opposite sides of the square, in order to collect a large sample of the surface finds. As noted in the report for 2009,1 experiments by Mark van der Enden have shown that a concen-tration on ‘feature pottery’ is permissible owing to its greater value for chrono-logical and functional analysis, so that most of the finds bagged by students were in this category. However special allowance is now made for the low recognisabil-ity and frequently small size of cookware and other coarsewares, through targeted collection strategies.

The total area covered by the ceramic survey runs now to 921 units of average 400 m2, although some parts of the city hill were left unsurveyed owing to precipitous slopes or dense scrub vegetation (left blank in the preceding figure). Some other units were overgrown sufficiently to disallow the counting of surface artefact density, but still with care we could collect samples of ceramics (Figure 2). Our main aim, which was achieved in the summer of 2011, was to fill in all accessible areas not so far surveyed and to clarify the edges of the built-up town as well as extramural activity zones.

One of the notable problems in Boeotia is the extraordinary density of surface pottery of pre-modern date in the rural landscape. It is normal for carpets of ceramics to extend one or two kilometres out from ancient major towns and villages, and these increase in density as one approaches the boundaries of such settlements. In the absence of standing city walls, a fringe of recognisable extra-mural cemeteries, or other indications, locating the formal edge of an ancient nucleated settlement is therefore extremely difficult. In our previous researches in Boeotia we have been able to observe that surface domestic sites of all sizes from a family farm to the largest urban site have a tripartite zonation:2

1 Bintliff et al. 2009-10, 35-41. 2 Bintliff et al. 2007.

97016.indb 2 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 3

Figure 1. Survey units at Koroneia on an aerial photograph (B. Noordervliet)

97016.indb 3 13/03/14 10:50

4 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 2. Units surveyed with a distinction between those where density of artefacts could be measured and pottery collected, and those where vegetation only allowed the collection

of ceramic samples (B. Noordervliet)

97016.indb 4 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 5

1. The core of the site, the focus of sustained domestic occupation, with the highest surface density of finds and those with the freshest appearance (brought to the surface from archaeological settlement deposits).

2. A site halo surrounds the site core. This consistently shows a lower level of surface finds’ density to the core, and is a mixture of mostly worn sherds and a minority of freshly-broken material. On closer examination this zone runs from some tens of metres in a farm site to several hundred metres for a city site, and seems to be made up of rubbish dumping, burials, extramu-ral ‘infield’ gardens, site erosion outwards due to agriculture and weather, and occasionally sanctuaries and industrial areas.

3. Beyond this can be found, often in Boeotia at least, but not always, an off-site secondary impact zone of the site, a thinner carpet of surface sherds which declines with distance and varies in radius with the size of the site core. In the case of large cities this zone can be observed for several kilome-tres distance, for farm sites a few hundred metres. The material is usually worn and in Boeotia is believed to be almost entirely due to the artificial transport of settlement rubbish into the community’s agricultural fields for manuring purposes. As has been observed in many Near Eastern landscapes, offsite carpets tend to be of only one or two phases of landscape use, gener-ally when population and farming reached rare high peaks requiring increased production from the countryside. Within this carpeted rural zone can also be found farms, hamlets and cemeteries, but they are generally dis-tinct from such offsite ceramic spreads through the quantity and/or quality of surface finds.

In 2006 density measurements had been taken in the rural landscape surrounding the city of Koroneia3 and it was clear that this city formed no exception to the tripartite scheme just presented. It was therefore anticipated that defining the borders of the town would create a research challenge, since up to 2010 only one short stretch of possible city wall had been identified. In the 19th century, Western travellers had still been able to observe more substantial city wall traces complete with towers, but the only other defensive or boundary walls we had recognised at the site since commencing intensive survey there, were on the acropolis, and these were of late Archaic-Early Classical and Late Antique date.

The city survey has been designed not merely to cover the entire town surface but also its immediate extramural sector, where urban cemeteries and other activ-ities would be expected. Much of the work carried out in the 2010 field season was indeed carried out in what we believed was the inner halo (zone 2, above) or

3 Bintliff & Slapsak 2006.

97016.indb 5 13/03/14 10:50

6 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

immediate extramural area round the city walls. A major aim was to try to use the quality of the surface finds, and their size and freshness, to seek distinctions between intramural occupation debris and the dumping of secondary rubbish beyond the city walls. By and large this proved successful, but in some grids the nature of recent land use made such an analysis hard or even impossible: an area left without cultivation for some years will produce little surface material and this will be in a very eroded form, whilst an area subjected to unusually heavy cultiva-tion can also see its finds diminished in their size and lose their freshness. Figure 2 displays the density of surface finds, corrected for visibility, by the time of the conclusion of our city survey in 2011, excluding grid squares with very low visibil-ity (3/10 or less of the soil visible) owing to sample error in such conditions. It is clear that remarkable densities continue to the foot of the Koroneia hill, well into areas we now know to be extramural cemetery zones. Except for one clear small area in the far south where a stream-course coincides with a dramatic drop in density, no other bordering areas show likely steep fall-offs in sherd densities appropriate to being outside the built-up urban zone within the putative city walls.

Fortunately three independent sources of evidence came to our aid, allowing a check on our purely ceramic estimates of the city’s edge, which had been based more on the condition of sherds rather than density. Firstly, advanced mapping by B. Noordervliet recognised two stretches of city wall foundation in the north-west part of the city site, one on the north-facing and another on the west-facing lower slopes of the Koroneia hill (Figures 3-4). These foundations are in soft limestone and would not have been used above ground because of this rock’s susceptibility to disintegrate in the open air. Now that parts of these sections are being eroded due to lack of maintenance of the terraces in which they are embed-ded, individual wall blocks are literally ‘melting’ into loose sand. Taken together

Figure 3. Foundations of the Lower City wall, facing northwards, in the north-west hill

perimeter

Figure 4. Foundations of the Lower City wall, west-facing section, lower hill perimeter

97016.indb 6 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 7

with a putative but much shorter stretch of wall located in an earlier season on the southernmost side of the city-hill, these discoveries provide a much-needed independent check on the line of the pre-Roman fortifications of the city.

An unexpected second form of evidence emerged from the surface ceramics themselves. A series of large roof tiles of Classical-Hellenistic type bore a distinc-tive stamp which clearly represents the city of Koroneia (Figure 5), a simple stamped monogram combining a Koppa (an early form of Kappa) and a Delta, and sometimes also an Alpha. Koroneia’s early coinage bore the Koppa sign, and the combination on these tiles should represent the Demos or People of Koroneia. Our working hypothesis is that these tiles are official roofing for the city wall, a proposal well supported by the distribution of the tiles, which predominantly (but not entirely) lie in the general neighbourhood of the projected wall-line (Figure 6). Particular importance can be attached to further discoveries of stamped tiles with the city of Koroneia’s monogram after those noted for 2010, in 2011. Apart from examples found to the extreme north-east at the foot of the city hill and clearly in an extramural cemetery zone, and a new example by the earlier discovered Classical cemetery somewhat to the south of this near a rock-cut tomb, more spectacular finds of this artefact were revealed by new agricultural bull dozing in the north-west high up on the steep edge of the city hill.

Figure 5. Official city tile of the people (Damos) of Koroneia.

97016.indb 7 13/03/14 10:50

8 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 6. Distribution of official stamped roof tiles across the city survey grid by 2012; in green, the suggested line of the Classical-Hellenistic Lower City wall with an extramural area

in blue (J. van Zwienen & B. Noordervliet)

97016.indb 8 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 9

Here the creation of small steep terraces for cultivation had cut through thick slopewash and archaeological deposits, revealing a significant sequence which could be interpreted by our geomorphologist, Dr Keith Wilkinson (Winchester University). A line of Classical city wall, including a square tower, was exposed, associated with a whole series of well-preserved stamped city-wall tiles (Figure 7). In Figure 8 we can see the outer face of a wall tower. Dr Wilkinson’s study of the hill sediments in this locality showed that the wall had been built atop a steep slope, which was subsequently coated with hill wash parallel to that slope and containing urban waste. Over this series came a horizontal thick layer of almost sterile recent soil now cut through by the modern terrace creation.

Evidence of a different kind but equally decisive for our final understanding of the plan of Koroneia came from the discovery of a new industrial quarter in the south of the city hill, close to a new Classical and Roman cemetery, south of the earlier discovered potters’ quarter on the eastern lower slopes of the city hill. This clearly allowed us to confine the borders of the town on the south-east, and made it clear that the southernmost sectors of our survey, covered in earlier seasons,

Figure 7. Disturbed deposits around the ancient city wall with fragments of official stamped roof tiles, north-west upper hill sector

97016.indb 9 13/03/14 10:50

10 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

although showing domestic activity and agricultural installations, must now be assigned to extramural and indeed rural settlement (blue outline in Figure 6). This was supported by a tombstone in the south-west of the town near to a large slop-ing sector which we had proposed as an extramural cemetery in earlier seasons.

Yet a third element can be added to the cumulative sources for defining the maximum extent of the ancient city. As noted in previous preliminary reports in Pharos, two cemetery locations have already been identified during our progressive survey of the town site. One lies on the north-east lower hill perimeter and pro-duced Archaic to Hellenistic grave goods. A second lies on the eastern lower slopes and is distinctive for the large quantity of architectural finds, including a tomb-stone of Roman age. During the 2010 summer season an almost continuous dis-tribution of fineware ceramics ranging from late Geometric to Hellenistic in age was recovered during survey of the north-facing lower slopes of the city-hill. At one notable locality where the hill turns south, and near the stream which borders

Figure 8. The outer face of a city wall tower on the north-west upper city hill

97016.indb 10 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 11

the west side of the city, a spectacular density of special finds was observed. The micro-collection of this material (largely of miniature vessels) was carried out under the supervision of Prof. Stissi (Figure 9) and appears to represent votives from an extramural sanctuary. Immediately nearby were also robbed grave cham-bers and wider finds presumed to derive from burials contemporary with the sanctuary, of Classical to Hellenistic age. From this point running almost without interruption along the foot of the hill eastwards, and reaching to the small emi-nence of the Crusader tower, we found a series of foci appearing to represent burial finds of proto-historic to Hellenistic date.

One problem with all this material is the absence of a ceramic assemblage that can verify continued use of these areas for burial during Roman times, despite the clear evidence that the city remained a large nucleation during the Early Empire. This is a wider problem in Roman Greece, since both grave and sanctuary depos-its lose their distinctive assemblages and in their place come ceramic and other finds which look equally at home in a domestic context. Given, as noted above, that the extramural sectors of ancient Boeotian cities are covered with dense finds of pottery, there is serious doubt if specific Roman burial finds can be separated from dumping of urban refuse into the immediate extramural area. Indeed the discovery in 2009 of the north-east Roman cemetery was not due to any unusual

Figure 9. Sanctuary deposit from outside the north-west city wall

97016.indb 11 13/03/14 10:50

12 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

ceramic finds but rather to the agglomeration of broken architecture in one field just outside the suspected city wall line. We therefore were fairly certain that the pre-Roman cemeteries discovered in 2010 continued into Roman times on the north lower slopes of the city hill, but were unable so far to isolate ceramic signals that differed from domestic debris. It was thus a relief, as well as a remarkable discovery, when amidst this burial zone we came across a very unusual artefact (Figure 10), the lid of a Roman stone sarcophagus. One of us, Prof. Bintliff, must confess that in thirty-two years of field survey in Boeotia, this is the first time he has found such an object in the field, and that should not surprise, since they have usually found their way into museum courtyards or been recycled into post-Roman buildings.

We are now able to define the maximum extent of the ancient city through combining wall indications (physical foundations and wall tiles), cemeteries, and what seem now clearly to have been immediately extramural industrial quarters on the east and south-east (Figure 11). The town was clearly, even at its most expansive, much smaller than previously envisaged, little more than 30 hectares. The uneven spread of the urban plan reflects today the very steep and unusable western hill

Figure 10. Roman sarcophagus from the extramural cemetery zone on the northern slopes of the city hill

97016.indb 12 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 13

Figure 11. Key elements for identifying urban boundaries and urban infrastructure (J. van Zwienen & B. Noordervliet)

97016.indb 13 13/03/14 10:50

14 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

edge and the more gentle slopes to the north, east and south, a contrast Dr Wilkinson has shown to be due completely to a contrasted bedrock geology (Figure 12). The dominant low grade metamorphic bedrock of the western half of the hill creates steep rocky topography poorly suited to the gentle stable slopes required for urban construction, whereas the high grade metamorphic rocks of the eastern hill are very suitable for buildings. Notably the rare exposures of limestone in the northern part of the hill were widely mined for city architecture.

Turning now to our provisional reconstructions of the long-term occupational history of the city-site, although previous visitors to Koroneia had seen prehistoric material, if rare, we had till 2010 discovered hardly any such finds on the hill, and those identified tended to be isolated. In contrast the 2011 season produced a regular trickle of prehistoric sherds and some stone tools along the northern lower hill slopes.

Figure 12. Geological division between the unstable low-grade metamorphic geology of the western side of the Koroneia hill, and the stable high-grade metamorphic basis of the eastern city hill. The map also shows the very slight surface exposures of limestone in the far north of the hill com-pared to its wide use in the ancient structures and terraces over the eastern hill (K. Wilkinson)

97016.indb 14 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 15

Sporadic traces of Early Iron Age ceramics seem to mark the beginnings of the historic city, although it is only by the Archaic era that the spread of finds suggests genuine urbanism, a scenario we have also observed at our other Boeotian cities such as Thespiai, Hyettos and Tanagra. The Classical and especially Early Hellenistic periods witness the maximum expansion of the town, also observed in Boeotia in general, a time of maximum rural and urban populations in this province of Greece. Contraction is currently indicated by a reduced spread of Early Roman material, while we currently propose that the Late Roman town was even more confined in extent, and was largely focussed on the acropolis and an extramural suburb in and around the Forum/Agora (which lay on a lower plateau below and east of the acropolis; see Figure 11). The acropolis itself was rewalled in Late Antiquity, to judge from two exposures, whilst inside it, the former public zones appear to have been given over to unpretentious domestic settlement (including agricultural processing from several finds of large recepta-cles and a large press base), and an impressive multi-storeyed central public building (on which see below). It would then compare well to the class of Kastra which dominate the archaeological record of nucleated settlements in the Late Antique Balkans.4

Ceramic analysis of the city grids is still in progress, and we still await evidence for a clear focus for the dispersed finds of prehistoric ceramics and lithics, and the same goes for the interval after the Late Roman activity on the acropolis and nearby, the so-called Early Byzantine ‘Dark Ages’ of the 7th-9th centuries AD. We might suggest that occupation could have continued within the Kastro, for which a parallel has been identified by our project at the fortified hilltop village of Ayios Konstantinos near ancient Tanagra in eastern Boeotia. Till 2011, Medieval and Post-Medieval material remained confined to the immediate surroundings of the Crusader tower at the foot of the city hill, encouraging our belief that this had been a small community settled around the tower itself. But where was the usual Greek village whose products provided the subsistence base for the Frankish lords and their household? The 2011 season answered that question. Immediately below the Crusader tower in the north-east of the site, in the first flat ground of the northern Koroneia plain, amidst a Classical and Roman cemetery, we discovered a settlement of the Middle and Late Byzantine period (Figure 13).

Another feature of the August 2011 season was the detailed planning of several built structures surviving on the surface of the site. This was carried out within the framework of a one-week European training school, the staff responsible being Hanna Stöger and Eric Dullaart (both of Leiden University), working with Total Stations. Just outside the city to the north-east is a small hillock crowned by one face of the Crusader tower, around which giant fragments lie from its collapsed

4 Liebeschuetz 2007.

97016.indb 15 13/03/14 10:50

16 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

internal vaulting. Planning this monument adds an additional piece of evidence to our much older work on similar towers in Boeotia.5 Inside the city itself this team planned two important ruins, both of Late Antique date, at least in their final form. One is a series of rooms immediately inside the present entrance track in the far south of the acropolis. Speculation that this was a church has now been replaced, after clearance of concealing vegetation, by a series of interlocked rooms and spaces that either represents small houses or shops/workshops (Figure 14). The small rooms are built of varied materials, including recycled pillars, an altar or monument base, recycled fine cut blocks, small stones, tiles and mortar, and show more than one phase. Traces of similar ‘scruffy houses’ can be seen in the northern acropolis, also utilising spolia pillars.

The other major planning project on the acropolis was to try and make more sense of the extensive and complex, collapsed Late Roman structure almost at the summit of the acropolis and in its northern sector. Dr Inge Uytterhoeven (Leuven University) had already dated this structure to the 6th century AD from the massive tiles inset into its vaults, and informed us that earlier suggestions of a bathhouse (hence the local name for the acropolis ‘Loutro’) must be rejected. Vegetation clearance revealed a much larger building than was earlier apparent (Figure 15), although almost all the visible walls are in fact giant multiple collapsed

5 Lock 1986.

Figure 13. The Frankish tower with the location of the Byzantine-Frankish period village below it in the olive groves on its far side

97016.indb 16 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 17

vaults, probably from the ground floor. The new plans, and the discovery that the largest standing section preserved a confluence of three vault lines, as well as evidence that some sections of vaults are in situ, should allow Dr Inge Uytterhoeven to suggest the form of the building. Current theories are either an episcopal palace or the residence of the governor of the Late Antique town.

In the years 2010-2012 our urban architecture specialist Dr Uytterhoeven worked over the entire Koroneia city site to undertake detailed recording of the numerous surface architectural pieces which had been noted during the course of survey in the summer of 2009. The 1250 pieces so far recorded were located to fine precision by B. Noordervliet and J. van Zwienen with the aid of a Differential GPS device, and their analysis will greatly aid our refining of the functional infra-structure map of the ancient town.

Geological, geomorphological and land use research at ancient Koroneia

In 2011 and 2012, Dr Wilkinson, with the assistance of his students, conducted geomorphological studies (including sediment coring) on and around the ancient town, to clarify the age and nature of the alluvial and slopewash deposits on and around the city (Figure 16). The chief aim of this research was to study landscape change in the area of the ancient town and the changing shoreline of nearby Lake Copais. In 2010 Dr Rob Shiel (Newcastle University) continued his mapping of soils and land-use in the hinterland of the ancient city of Koroneia.

Figure 14. The ‘scruffy Late Antique houses’ of the south acropolis

97016.indb 17 13/03/14 10:50

18 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 15. One line of collapsed vaulting of the extensive 6th century AD public building near the

summit of the acropolis

Figure 16. Geomorphological coring near Koroneia: Dr K. Wilkinson and his team. In the right background the city hill of Koroneia, in the left background the smaller

Crusader tower hill

97016.indb 18 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 19

During Dr Wilkinson’s geophysical probes within the city itself, traces of sub-surface architecture were revealed in the Agora-Forum areas, using non-destructive magnetic resonance readings, suggesting public buildings. Further geophysical tests will continue in 2013.

Virtual reality reconstruction of ancient Koroneia

Between 2011 and 2013 Chiara Piccoli (EU Project PhD, Leiden University), has continued to develop the Virtual Reality model of the ancient city of Koroneia (Figure 17), in collaboration with the ongoing studies at that site. This is intended to form a local heritage resource for village schools in the Koroneia region and will be completed during 2014. In connection with the EU Project CEEDS, Piccoli also organized study visits by other members of the EU consortium to Boeotia, where teams from Goldsmiths’ College, London University and the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig conducted experiments on the visual and mental procedures employed in the analysis of surface survey ceramics.

The ancient city of Hyettos

Between 2011 and 2012 the Leiden team (led by Prof. Bintliff, B. Noordervliet and J. van Zwienen) completed the mapping of surface architecture remains at this ancient city, covering in all 38.68 hectares of ground on the acropolis and in the

Figure 17. Early stage virtual reality reconstruction of the acropolis and lower town of Koroneia in Hellenistic times (C. Piccoli)

97016.indb 19 13/03/14 10:50

20 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 18. Location of GPS-located points where significant surface architectural pieces are present at Hyettos (B. Noordervliet & J. van Zwienen)

97016.indb 20 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 21

lower town and around it. More than 500 locations were identified and mapped where significant pieces of ancient architecture survive on the surface (Figure 18), a remarkable count when we consider that the city lies along a major route to the coast from north-east Boeotia, and lies within sight of the modern village of Loutro and not far from a second larger village, Pavlo. These pieces will be studied by Dr Uytterhoeven. They include a capital which seems to belong to an urban sanctuary, whose plentiful finds of high quality Classical fineware and figurines were noted in the original surface survey of the city in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the same time J. van Zwienen began to make a more detailed surface topographic map of the city site with a Differential GPS-device, since the existing 1:5000 map shows little detail in the rather flat lower town. The next illustration fits the vertical air photographs to our original survey grid and a first version of the new digital elevation model (Figure 19).

The third Boeotia final monograph (on the others see below) will deal with the city and countryside of ancient Hyettos. Restudy of the ceramic finds began in 2010 and continued in 2011 and 2012, and will hopefully be completed in 2013. In parallel geophysical work, following a pilot study in 2012, will be conducted in 2013 and 2014 by Prof. A. Sarris (University of Crete). The remote sensing programme is needed to prepare a town plan, and also to define the city borders in order to assist the Ephorate in creating the archaeologically protected zone. In addition, in 2012 a geodetic team of Leiden students led by B. Noordervliet and Prof. Bintliff made microscale topographic maps for the 17 rural sites discov-ered by an earlier survey in the hinterland of Hyettos in order to analyze their locational priorities (Figures 20-21).

Figure 19. A digital elevation model of Hyettos acropolis and lower town with the original surface survey grid as well as the vertical air photograph overlaid onto it (J. van Zwienen & E. Farinetti)

97016.indb 21 13/03/14 10:50

22 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 20. Bart Noordervliet and students on the acropolis of Hyettos, setting up the base-station for the Differential GPS device in use for detailed site recording. The light ‘rover’ sends location and height measurements to the base station over

a distance of up to 6 or 7 kilometres

Figure 21. Digital elevation model of the topographic placing of sites CN 10, 11, 12 and 14 in the rural hinterland of ancient Hyettos city (B. Noordervliet)

97016.indb 22 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 23

The ancient city of Thespiai

The first monograph of the Boeotia Project is already published,6 and dealt with the southern rural hinterland of the ancient town of Thespiai. The second mono-graph will present the urban survey of Thespiai itself.7 In 2010 Prof. Snodgrass assisted Prof. Bintliff with the completion of the catalogue of all finds in the Thespiai Museum deriving from the older Boeotia Project. In 2012 the ceramic restudy programme also finished all the material from this ancient city, which has already had a full architectural survey and trial geophysics in earlier years.

The ancient village of Askra and the Valley of the Muses

The fourth Boeotia monograph will deal with the surface ceramic finds from the small town of Askra and its countryside – the Valley of the Muses – surveyed in the 1980s. In 2012 a first group of several of the survey sites and the site of Askra itself were revisited by Prof. Bintliff, Prof. Snodgrass and a digital mapping team as the first step towards final publication of this survey zone. The Middle Byzantine church at Askra was formally planned for the first time, by Dr Vionis (University of Cyprus), Yasemin Ozarslan (Koc University) and Yannick Boswinckel (Leiden University), revealing new details of its episcopal structures (Figures 22-23). The redating of the survey ceramics began in 2011. Dr Kalliope Sarri with the assistance of Ms Gry Nymo restudied the prehistoric finds from the city and rural survey of the Askra and the Valley of the Muses, as part of the preparations for the publica-tion of this older fieldwork. In 2012 Prof. Snodgrass assisted Prof. Bintliff with the completion of the catalogue of all finds in the Thespiai Museum deriving from the older Boeotia Project.

It is planned for 2013 to continue geophysical tests at Askra with a team led by Prof. Frank Vermeulen from Ghent University, as the town plan is completely unknown, and also to continue the 2012 checking of surface architecture survey to see if more remains have appeared in recent years.

The ancient city of Haliartos

The fifth Boeotia monograph will cover the ancient city of Haliartos and its coun-tryside. Aerial photography and geophysics in recent years, up to 2011 (work of the Ljublana University team), have already revealed important details of the town plan at the city. No study was done in 2012 in this sector, but the remote sensing work will be continued in 2013 and 2014 and the ceramic finds will be redated in 2015.

6 Bintliff et al. 2007. 7 For a recent report, see Bintliff 2012.

97016.indb 23 13/03/14 10:50

24 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Figure 22. Recording the Episcopal church at Askra. Blocks to support the dome were tentatively identified in the foreground. The north wall of the church is in

the rear of the image

Figure 23. The recording study of the Askra church in 2012, following the interpretation of Dr A. Vionis, shows from the rear to the front of this view: a

water cistern, two storage rooms and then, by the north wall of the church, a vault with aniconic wall paintings, all probably dating to the 10th century AD

97016.indb 24 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 25

The ancient city of Tanagra

The sixth Boeotia monograph will cover the town and country survey of ancient Tanagra. The ceramic dating is complete but there remains continuing examina-tion by geophysics of that part of the ancient town lying outside the Late Roman walls, a task which was continued in 2011 by the Ljubljana team. This remote sensing work will continue in 2013 to define the extent of the extramural areas of the ancient city left outside the smaller Late Roman circuit-wall. The 2011 research was directed by Prof. Bozidar Slapsak, with Sara Popovic (University of Ljubljana) responsible for architectural survey, and Rok Plesnicar (BA), for geo-physical survey.

The goal of the architectural survey was to document surface structures pertain-ing to the standing city wall as known from previous publications. Somewhat less than one third (750 m) of the total wall outline could be recorded. Cleaning revealed unmistakeably and invariably Late Roman building techniques, mixed (limestone and sandstone blocks, stone and brick in-between), with ample use of spolia (including blocks arguably from an earlier, Classical city wall), and regular use of mortar. All structural remains recorded are precisely georeferenced and integrated into the CAD and GIS database so we can now integrate the wall line properly into our base document (the magnetometry map). In 2011, S. Popovic was entrusted with directing the city wall structural survey. Including the north-ernmost part of the west wall between the Thebes gate tower 14 and the corner tower 16, and the west part of the north wall between towers 16 and 27, some 700 m of the wall were documented altogether. The idea behind this choice was to compare the stretch of the west wall, which would according to our magnetom-etry results maintain the same line since the Classical period, and the north stretch, which our geophysics clearly defines as late, possibly Late Roman. In terms of location, valuable corrections of the wall line and the position of the towers could be made. However, the problem of the assumed north gate, the earlier scholar Roller’s Delion gate, could not be resolved, and besides precise layout, the only information to add concerning the bastion assumed by Roller to be part of the gate structure,8 is that it contains a large cistern. In terms of building material and building technique, however, there appears to be no difference between the two parts. Indeed, the local dark grey limestone blocks, which misled Roller to date the whole of the wall circuit to the 4th century BC are omnipresent, and may well have been to some extent part of the early wall. Within the structure documented, however, they are deployed as spoliae, often turned wrongly to their side, but normally located on the front, with sandstone blocks and sometimes architectural

8 Roller 1974.

97016.indb 25 13/03/14 10:50

26 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

members in the middle. All blocks and in-fill are bound with chalk and mortar. Thus, to judge from the building technique, the visible city wall was built in one go, and that in Late Antiquity, to accommodate the reduced city population and institutions.

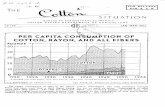

This city wall, previously published by Roller as Late Classical,9 and now clearly in its current form defined as Late Roman, cuts off parts of the regular urban planning grid of the Classical city dated to the 4th century BC (Figure 24). In 2005, magnetometry survey revealed that situation in the north-west part of the town, and the goal of this year’s survey was to check areas to the north-east and east of the present wall as well. Magnetometry survey was done by R. Plesnicar in 2011 over those areas available for prospection to the north-east and east of the late wall circuit. However patchy and lacking architectural detail, the map shows clear traces of streets in the same grid as within the perimeter of the late walls.

In all parts surveyed, the grid continues, so currently we estimate the extent of the Classical city to be over 60 ha as compared to under 30 ha of the Late Roman walled city. However, at one point at least, the grid appears also to cross the assumed line of the walled Classical city in the east, so we must be cautious there and permit the possibility that we have the urbanized area or some suburbs descending down towards the Asopos river (Figure 24).

Observation of surface structures and morphology beyond the visible city wall circuit is done as a series of targeted surveys aimed at verifying assumptions and propositions developed from the data already at hand. As a result, two short stretches of Classical city wall were found: one was documented in 2006 some 100 m north beyond the late wall, 15 m long and 3 m wide, but preserved mainly as one line of limestone blocks and forming the south front of the wall; the other was detected and documented in 2011 on the acropolis hill south beyond the late wall, 6 m long and 2.7 m wide, also preserved mainly as one line of limestone blocks and forming the south front of the wall. In surface morphology, the Clas-sical acropolis wall can be traced from tower 1 of the late wall direction east, down the line of the Classical wall documented in 2011, then around the east, and down the north acropolis slope, entering the late wall precinct just east of the temple theatre terrace, thence following the terrace westward up to the late west wall, and then rejoining tower 1 at the top. There are a number of points and sectors argu-ably representing segments of the lower city Classical wall, notably in its south part, while in the east and north, the urban outline is difficult to impossible to follow through surface morphology because of its recent transformations by agri-cultural use.

9 Roller 1974.

97016.indb 26 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 27

Figure 24. Tanagra city geophysical surveys north and east of the standing Late Antique enceinte reveal clear traces of the much larger town gridplan of Classical times. Also visible are provisional

suggestions of the line of the Classical city wall and its acropolis, as well as possible extramural suburbs, outside of the standing Late Roman urban fortifications (B. Slapsak)

97016.indb 27 13/03/14 10:50

28 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

The 2011 results call for continuation of fieldwork on ancient Tanagra: we know now that the urban structure is detectable by geophysics also beyond the Late Roman wall where intensive land use caused much destruction during the last half century, and we expect to have just from this survey precious new data on urban dynamics. The acropolis plateau should be one of the privileged areas to survey fully because, until now, we thought it comprised a miniscule area on the top of the hill. It is clear that we have a considerable surface there, which may hide some of the most important religious buildings of Tanagra. On the other hand, further architectural survey is needed to complete the outline of the Late Roman wall, and to record the key functional areas not yet documented.

Research in the countryside of Tanagra

In 2012 Dr Vionis and student Andreas Charalambous (University of Cyprus) carried out chemical analysis of 50 samples of Medieval coarseware pottery (amphorai, cooking pots, jugs and jars), from the surface collection already made from rural sites in the vicinity of Tanagra using a non-destructive technique (XRF), to clarify local production. Dr Vionis and his team also recorded a digital-elevation model of two Medieval and Post-Medieval rural sites near Tanagra (Ayios Thomas and Guinossati) for future publication of these settlements. Geo-physical tests at Ayios Thomas will begin in 2013.

The Medieval and Post-Medieval Virtual Reality Research Programme at Tanagra, Haliartos and Mazi

A separate architectural project on a number of standing Byzantine-Early Modern monuments in the regions of Tanagra (Ayios Thomas) and Haliartos was under-taken within the framework of the Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project in late August 2011 by Dr Vionis and Chiara Piccoli. A permit was issued to Dr Vionis by the General Directorate of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Antiquities of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism for the architectural recording and study of six monuments in Boeotia: the churches of Ayios Thomas Oinofyton (1 km south-east of the ancient city of Tanagra), Ayios Polykarpos (500 m north-west of ancient Tanagra), Ayia Aikaterini (2 km south-west of ancient Tanagra), Ayios Dimitrios (outside the contemporary village of Ayios Thomas-Liatani), the chapel of Zoodochos Pigi at Mazi (between the contempo-rary village of Mazi and the deserted village-site of Palaiomazi in the wider upland region of Haliartos town), and the Frankish tower of Haliartos (at the entrance of the contemporary town on the way to Thebes). The recording of these monu-ments was completed in August 2011. The recording team consisted of Dr Vionis,

97016.indb 28 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 29

Chiara Piccoli, Leon Theelen, and a number of students from the Universities of Leiden and Cyprus.

The aforementioned monuments were chosen because each one of them forms the most substantial part of deserted village- and hamlet-sites identified through intensive surface survey by (a) the Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project in the region of ancient Tanagra in 2000-2005 (i.e. the Byzantine-Medie-val sites of Ayios Thomas, Ayios Polykarpos, Ayia Ekaterini, and Ayios Dimitrios) and (b) the Durham-Cambridge Boeotia Project in 1979-1997 (i.e. the Ottoman deserted village of Dushia around the chapel of Zoodochos Pigi at Mazi, and the Frankish site around the tower of Haliartos). Apart from the immense and most vital contribution of ceramic surface field-survey to the study of post-Classical Greece, another way of examining traces of past human activity remains the stand-ing building evidence.10 Remaining Medieval and post-Medieval monuments in Boeotia, still providing evidence from above (rather than below) ground, however, are primary sources of information to be combined with textual/historical or other references. Thus, the aim of this architectural project was (a) to produce detailed and accurate plans of the monuments (as a means of recording their state of pres-ervation and making them available to the local community and other researchers in the field of Byzantine-Medieval rural architecture) and (b) to visualise in a 3D environment each monument in order to understand and interpret its interior use and movement within it.

For the recording of the standing structures we used a Reflectorless Total Station (Robotic Total Station), while the data was (and is still being) processed through AutoCAD, a CAD software application for 2D and 3D design and drafting. Although this is a precise method of producing the desired plans and 3D reconstructions, it is a time-consuming process, especially when it comes to the processing of the measurements with the aid of the computer software. So far, the 3D-reconstruction of two of the churches (Ayios Dimitrios and Zoo-dochos Pigi) (Figure 25) and the Haliantos tower, and the plans of all six have been produced.

This is not the first time that the Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project and its predecessor, the Durham-Cambridge Boeotia Project, have shown interest in the post-Roman monuments and housing of the Boeotian countryside. The British historian Dr P. Lock, for instance, studied the surviving feudal towers of Boeotia and Euboea and dated them in the 13th–15th centuries;11 similarly, N. Stedman, Prof. F. Aalen and Dr E. Sigalos examined standing examples of the traditional

10 Vionis 2008. 11 Lock 1986.

97016.indb 29 13/03/14 10:50

30 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

long-house in most regions of Boeotia.12 Recently, more advanced recording tech-niques were employed for recording and studying traditional housing in Boeotian villages. Joep Verweij (former BA student at Leiden University) recorded in 2007 two surviving longhouses in the village of Ayios Georgios through stereographic photographing and produced an AutoCAD 3D model of these structures.13 Addi-tionally, Piccoli further developed this approach by using a Robotic Total Station for recording, in 2009, ten traditional houses in the villages of Mazi and Evange-listria.14

The church of Ayios Thomas is located in the middle of a deserted hamlet site with the site-code TS5, 1 km south-east from the ancient city of Tanagra. The village is approximately 1.5 ha in size, while the study of its ceramic assemblage suggests that the site was occupied from the 11th to the middle of the 14th century, reaching its peak from the middle of the 12th to the middle of the 13th century. It has been suggested that the church was constructed in the mid-12th century and converted into a Frankish feudal tower with chapel in the 14th century.15 The church of Ayios Polykarpos is located in the middle of the tiny deserted hamlet-site of TS21, 0.5 ha in size, 0.6 km north-west of the ancient city. The church is dated to the 12th century, while large ancient square blocks (from ancient Tanagra?) have been used for the construction of its apse. The church of Ayia Ekaterini is located in the middle of the large deserted hamlet-site of TS15, 2 km south-west of ancient Tanagra. The site occupies an area of approximately 2 ha, while surface ceramic finds are also dated from the 11th to the 14th centuries. The church was rebuilt in Early Modern times, while architectural observation of the eastern apse has revealed an earlier phase of Ayia Ekaterini (Middle Byzan-tine?). The church of Ayios Dimitrios, rebuilt in Early Modern times, is located on the top of a gentle hill, in the middle of the large deserted village-site TS30, occupying an area of 2.3 ha, in the upland Guinosati valley, west of the contem-porary village of Ayios Thomas.16 Architectural observation on the north and east wall has revealed that Ayios Dimitrios was also built on top of an earlier (Middle Byzantine?) church. Finally, Zoodochos Pigi, between the contemporary village of Mazi and the deserted site of Palaiomazi, is located at the site of Dushia, an aban-doned çiftlik of the late 16th to 18th centuries. The church was originally built in the Ottoman period (probably in the 16th century); the northern and western walls had collapsed and were rebuilt by local people recently. The southern and eastern walls preserve a remarkable series of fresco paintings of the Late Ottoman

12 Stedman 1996; Bintliff et al.1999; Sigalos 2004. 13 Bintliff et al. 2007, 37-42. 14 See her report in Bintliff et al. 2009-10, 50-55. 15 Simatou & Christodoulopoulou 1993, 54-55. 16 Vionis 2008, 33.

97016.indb 30 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 31

Figure 25. 3D-visualisation of the Byzantine church of Zoodochos Piyi (C. Piccoli)

Figure 26. Professor A. Snodgrass (right) giving a public lecture in the main square of the village of Askra, assisted by Dr A. Vionis (left).

97016.indb 31 13/03/14 10:50

32 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

period, depicting Saints (on the southern wall), Church Fathers and the Virgin (on the eastern apse), while the stone-built temple screen preserves fresco paint-ings of Christ enthroned and the Virgin, very good samples of Post-Byzantine provincial art (Figure 25).

Public outreach of the Boeotia Project

Finally the project received two requests in 2012 to give public community lec-tures about its research. The first came from the village of Askra and led to a public lecture by Prof. Snodgrass (Figure 26) and Prof. Bintliff on the settlement history of the Valley of the Muses and the origins of the modern village of Askra. The second came from the village of Ayios Georgios and led to a public lecture by Prof. Bintliff and Dr Vionis on the archaeology of ancient Koroneia city and the origins of the village of Ayios Georgios. Our project is delighted to com-municate its results to local communities and intends to deepen such work in future years.

J.L. BINTLIFF B.L. NOORDERVLIET

University of Leiden [email protected]@arch.leidenuniv.nl

J.M. VAN ZWIENEN K. WILKINSON

[email protected] University of [email protected]

B. SLAPSAK V. STISSI

University of Ljubljana University of [email protected] [email protected]

C.B.M. PICCOLI A. VIONIS

University of Leiden University of [email protected] [email protected]

Acknowledgements

The Project is directed by Prof. John Bintliff (Leiden University) and Prof. Bozidar Slapsak (Ljubljana University). Former director of the project Prof. Anthony Snodgrass has visited on various occasion to share his unique knowledge about the region and the project. He is also involved in publishing the upcoming volumes on the Boeotia Project. The Assistant Academic Director is Prof. Vladimir

97016.indb 32 13/03/14 10:50

THE LEIDEN-LJUBLJANA ANCIENT CITIES OF BOEOTIA PROJECT 33

Stissi (University of Amsterdam) and the Assistant Field Director is Dr Athanasios Vionis (University of Cyprus). Bart Noordervliet and Janneke van Zwienen com-bine their roles as Project Digital Field Recording Specialists with being our over-all Project Managers and Mark van der Enden (Leicester University), Leon Theelen and Yannick Boswinckel (Leiden University) have been successively man-agers of the Ceramic Laboratory. The GIS specialist is Dr Emeri Farinetti. Ceramic analysis was the responsibility of Dr Kalliope Sarri, Gry Nymo, Prof. Stissi, Mark van der Enden, Prof. Jeroen Poblome (Leuven University), Dr. Philip Bes (Leuven University), Dr Rinse Willet (Leuven) and Dr Athanasios Vionis (University of Cyprus). Epigraphy is in the care of Prof. Albert Schachter (McGill University) and Dr Fabienne Marchand (Oxford University). The architectural specialist is Dr Inge Uytterhoeven (Koc University) and the geological and geomorphological research is done by Dr Keith Wilkinson (Winchester University) and his team. Our accommodation at the Ecclesiastical Research Centre of Evangelistria is due to the kind support of Bishop Yeoryios of Thebes and Livadhia. The Project is enabled through the good offices of the Netherlands Institute at Athens, whose staff, and in particular the Director Dr Kris Tytgat, have provided their usual excellent assistance throughout the year. Prof. Vassilis Aravantinos and his succes-sor Dr Alexandra Charemi as Director at the Thebes Museum and their staff were perfect support for our work in Boeotia. A major part of the funding is made available through the Interuniversity Attraction Pole network of the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (BELSPO). The research of Dr Hanna Stöger is supported by the EU Project ARCHAEOLANDSCAPES, that of Chiara Piccoli (Ph.D. Researcher at Leiden University) by the EU Project CEEDS.

References

BINTLIFF, J.L. 2012. Contemporary issues in surveying complex urban sites in the Mediter-ranean region: the example of the city of Thespiai (Boeotia, Central Greece). In: F. Vermeulen, G-J. Burgers, S. Keay & C. Corsi (eds), Urban Landscape Survey in Italy and the Mediterranean, Oxford, 44-52.

BINTLIFF, J. et al. 1999. The traditional vernacular architecture of Livadhia. In: Livadhia: Past, Present and Future, Proceedings of the 1997 Conference, Livadhia, 85-99.

BINTLIFF, J.L., P. HOWARD et al. (eds) 2007. Testing the Hinterland: The Work of the Boeotia Survey (1989-1991) in the Southern Approaches to the City of Thespiai, Cambridge.

BINTLIFF, J. & B. SLAPSAK 2006. The Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project: 2007 season, Pharos. Journal of the Netherlands Institute at Athens XIV, 15-27.

BINTLIFF, J.L., B. SLAPSAK, B. NOORDERVLIET, J. VAN ZWIENEN & J. VERWEIJ 2007. The Leiden-Ljubljana Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project: summer 2007 – spring 2008, Pharos. Journal of the Netherlands Institute at Athens XV, 17-42.

BINTLIFF, J.L., B. SLAPSAK, B. NOORDERVLIET, J. VAN ZWIENEN, I. UYTTERHOEVEN, K. SARRI, M. VAN DER ENDEN, R. SHIEL & C. PICCOLI 2012. The Leiden-Ljubljana

97016.indb 33 13/03/14 10:50

34 JOHN BINTLIFF ET AL.

Ancient Cities of Boeotia Project 2009 seasons, Pharos. Journal of the Netherlands Institute at Athens XVII.2, 1-63.

LIEBESCHUETZ, J.H.W.G. 2007. The Lower Danube region under pressure: from Valens to Heraclius. In: A. Poulter (ed.), The Transition to Late Antiquity on the Danube and Beyond, Oxford, 101-134.

LOCK, P. 1986. The Frankish towers of central Greece, BSA 81, 101-123.ROLLER, D.W. 1974. The date of the walls at Tanagra, Hesperia 43, 260-263.SIGALOS, E. 2004. Housing in Medieval and Post-Medieval Greece, BAR I.S 1291, Oxford.SIMATOU, A.M. & R. CHRISTODOULOPOULOU 1993. Agios Thomas Tanagras. In: 13th

Symposium of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Archaeology and Art, Athens, 54–55.STEDMAN, N. 1996. Land-use and settlement in Post-Medieval central Greece: an interim

discussion. In: P. Lock & G.D.R. Sanders (eds), The Archaeology of Medieval Greece, Oxford, 179-192.

VIONIS, A.K. 2008. Current archaeological research on settlement and provincial life in the Byzantine and Ottoman Aegean: a case-study from Boeotia, Greece, Medieval Settlement Research 23, 28-41.

97016.indb 34 13/03/14 10:50