ITunes Booklet Parma, Book 15 (1756-57) Venice (1742 and ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of ITunes Booklet Parma, Book 15 (1756-57) Venice (1742 and ...

ITunes Booklet

Parma, Book 15 (1756-57)Venice (1742 and 1749)and other sources

COMPLETEKEYBOARD SONATASVOLUME SIX

CARLO GRANTEplaying the Bösendorfer 280 Vienna Concert

ScarlattiDomenico

2

CD 1 (74:58)PARMA, Book 15: Sonatas 1-20

1. P15-1 (K.514) in C major: Allegro 3:42

2. P15-2 (K.515) in C major: Allegro 3:06

3. P15-4 (K.516) in D minor: Allegretto 5:17

4. P15-3 (K.517) in D minor: Prestissimo 3:10

5. P15-5 (K.518) in F major: Allegro 5:13

6. P15-6 (K.519) in F minor: Allegro assai 3:41

7. P15-7 (K.520) in G major: Allegretto 4:37

8. P15-8 (K.521) in G major: Allegro 4:08

9. P15-9 (K.522) in G major: Allegro 3:52

10. P15-10 (K.523) in G major: Allegro 2:22

11. P15-11 (K.524) in F major: Allegro 4:26

12. P15-12 (K.525) in F major: Allegro 2:31

13. P15-13 (K.526) in C minor: Allegro comodo 5:47

14. P15-14 (K.527) in C major: Allegro assai 3:34

15. P15-15 (K.528) in B-flat major: Allegro 3:10

16. P15-16 (K.529) in B-flat major: Allegro 2:58

17. P15-17 (K530) in E major: Allegro 3:30

18. P15-18 (K531) in E major: Allegro 3:33

19. P15-19 (K.532) in A minor: Allegro 3:16

20. P15-20(K.533) in A major: Allegro assai 3:03

CD 2 (73:26)PARMA, Book 15: Sonatas 21-36

1. P15-21 (K.534) in D major: Cantabile 4:39

2. P15-22 (K.535) in D major: Allegro 3:22

3. P15-23 (K.536) in A major: Cantabile 5:49

4. P15-24 (K.537) in A major: Prestissimo 3:29

5. P15-25 (K538) in G major: Allegretto 4:03

6. P15-26 (K.539) in G major: Allegro 5:23

7. P15-27 (K.540) in F major: Allegretto 4:19

8. P15-28 (K.541) in F major: Allegretto 4:31

9. P15-29 (K.542) in F major: Allegretto 4:54

10. P15-30 (K543) in F major: Allegro 4:35

11. P15-31 (K.544) in B-flat major: Cantabile 4:53

12. P15-32 (K545) in B-flat major: Prestissimo 2:48

13. P15-33 (K.546) in G minor: Cantabile 6:57

14. P15-34 (K.547) in G major: Allegro 4:32

15. P15-35 (K.548) in C major: Allegretto 4:15

16. P15-36 (K.549) in C major: Allegro 4:56

CD 3 (78:14)PARMA, Book 15: Sonatas 37-42

1. P15-37 (K.550) in B-flat major: Allegretto 4:24

2. P15-38 (K.551) in B-flat major: Allegro 4:34

3. P15-39 (K.552) in D minor: Allegretto 4:42

4. P15-40 (K.553) in D minor: Allegro 4:15

5. P15-41 (K.554) in F major: Allegretto 5:29

6. P15-42 (K.555) in F minor: Allegro 3:53

VENICE 1742

7. V42-3 (K.45) in D major: Allegro 3:37

8. V42-9 (K.51) in E-flat major: Allegro 3:09

9. V42-10 (K.52) in D minor: Andante moderato 8:58

10. V42-16 (K.58) in C minor Fuga 2:51

11. V42-17 (K.59) in F major: Allegro 2:01

12. V42-19 (K.60) in G minor 2:03

13. V42-20 (K.61) in A minor 2:52

14. V42-21 (K.62) in A major: Allegro 3:09

15. V42-23 (K.63) in G major: Capriccio. Allegro 2:08

16. V42-24 (K.64) in D minor: Gavotta. Allegro 1:49

17. V42-25 (K.36) in A minor: Allegro 2:13

18. V42-26 (K.65) in A major: Allegro 1:55

19. V42-27 (K.38) in F major: Allegro 2:35

20. V42-28 (K.66) in B-flat major: Allegro 3:41

21. V42-29 (K.67) in F-sharp minor: Allegro 2:20

22. V42-30 (K.68) in E-flat major 5:33

CD 4 (73:56)VENICE 1742 continued

1. V42-34 (K.70) in B-flat major 2:12

2. V42-35 (K.71) in G major: Allegro 2:01

3. V42-36 (K.72) in C major: Allegro 2:30

4. V42-37 (K.73) in C minor: Allegro-Minuetto- Minuetto 6:46

5. V42-38 (K.74) in A major: Allegro 1:32

6. V42-39 (K.75) in G major: Allegro 2:22

7. V42-40 (K.76) in G minor: Presto 2:16

8. V42-41 (K.37) in C minor: Allegro 3:46

9. V42-42 (K.77) in D minor: Moderato e cantabile-Minuet 6:34

10. V42-43 (K.33) in D major 3:40

11. V42-44 [a] (K.78a) in F major: Giga. Allegro 2:56

12. V42-44[c] (K.94) in F major: Minuet 1:52

13. V42-45[a] (K.79) in G major: Allegrissimo 2:02

SCARLATTI: THE COMPLETE KEYBOARD SONATAS. VOL. VICarlo Grante, piano

3

14. V42-45b (K.80) in G major: Minuet 1:34

15. V42-46 (K.81) in E minor: Grave-Allegro- Grave-Allegro 10:34

16. V42-47 (K.82) in F major 2:36

17. V42-48 (K.83) in A major 5:25

18. V42-49 (K.84) in C minor 2:46

19. V42-50 (K.85) in F major 3:09

20. V42-51 (K.86) in C major: Andante moderato 7:21

CD 5 (74:51)VENICE 1742 continued, VENICE 1749, and miscellaneous sources (Boivin Roseingrave-Cooke)

1. V42-53 (K.88) in G minor: Grave-Andante moderato-Allegro-Minuet 10:01

2. V42-54 (K.89) in D minor: Allegro-Grave- Allegro 7:27

3. V42-55 (K.90) in D minor: Grave-Allegro- (12/8)-Allegro 13:34

4. V42-56 (K.91) in G major: Grave-Allegro- Grave-Allegro 9:44

5. V42-57 (K.31) in G minor: Allegro 4:42

6. V42-58 (K.92) in D minor 5:25

7. V42-60 (K.93) in G minor: Fuga 3:15

8. V49-4 (K.102) in G minor: Allegro 3:10

9. V49-5 (K.103) in G major: Allegrissimo 3:14

10. V49-20 (K.117) in C major: Allegro 6:55

11. Boivin - v. III, 1 4:16

12. Boivin - v. III, 3 3:06

CD 6 (73:21)Miscellaneous sources continued (Boivin-LeClerc, Bologna, Cambridge-Fitzwilliam, Granados, Haffner, London-Worgan, Milano-Noseda, Munster)

1. Boivin-LeClerc 2-16 (K.95) in C major: Vivace 1:52

2. Boivin v. III,10 2:54

Photo: ©Merisi’s Vienna

3. Boivin-LeClerc 5:6 (K.97) in G minor: Allegro 6:19

4. Bologna 3:29

5. Cambridge-Fitzwilliam 13-5 (K.145) in D major 4:03

6. Cambridge-Fitzwilliam 13-7 (K.146) in G major 3:01

7. Granados 10 (Catalonia 31) 3:23

8. Haffner 5 4:16

9. London 14248, f 15v-16r 3:24

10. London-Worgan 41 (K.141) in D minor: Allegro 3:36

11. London-Worgan 42 (K.142) in F-sharp minor: Allegro 4:05

12. London-Worgan 43 (K.143) in C major: Allegro 4:43

13. London-Worgan 44 (K.144) in G major: Cantabile 4:57

14. Milano-Noseda L22-8 2:10

15. Münster 2-51 (K.452) in A major: Andante allegro 3:21

16. Münster 2-52 (K.453) in A major: Andante 5:07

17. Münster 5-21a 3:57

18. Münster 5-22 (K.147) in E minor 8:44

CD 7 (32:03)Miscellaneous sources continued (Barcelona, Catalonia, New Haven, Paris-Arsenal, Roseingrave-Cooke)

1. New Haven X-1 4:43

2. New Haven X-2 3:32

3. Paris (A) 4:21

4. Roseingrave-Cooke 12 (K.35) in G minor: Allegro 3:57

5. Roseingrave-Cooke 28 (K.39) in A major: Allegro 2:00

6. Roseingrave-Cooke 30 (K.40) in C minor: Minuetto 1:54

7. Roseingrave-Cooke 43 (K.42) in B-flat major: Minuetto 1:40

8. Roseingrave-Cooke 6 (K.32) in D minor: Aria 2:24

9. Roseingrave-Cooke 9 (K.34) in D minor: Larghetto 2:11

10. Barcelona 11 3:09

11. Catalonia 34 2:10

4

DOMENICO SCARLATTI (1685–1757)

LIFEDomenico Scarlatti was born in Naples on October 26, 1685, the sixth of ten children of Alessandro Scarlatti. He shares his birth year with Joh. Seb. Bach and G.F. Handel. His first teachers were probably members of the large Scarlatti family, and his musical talents developed so quickly that at the age of fifteen he was employed as an organist at the Royal Chapel in Naples, with a special additional payment for the post of clavicembalista di camera.

In the summer of 1702 his father was asked to compose an opera for the Medici court. He took Domenico with him to Florence. There Domenico certainly became acquainted with Bartolomeo Cristofori, the ingenious inventor of the first properly working piano action, and evidently learned to play this new cimbalo con piano e forte, whose idiomatic touch—as Maffei pointed out in 1711—was not easy for an organist and harpsichordist. In 1704 Domenico went to Rome in order to continue his composition studies under the guidance of Bernardo Pasquini and Gaetano Greco. In 1705, on his way to Venice, where he hoped to study with Francesco Gasparini, whom he had apparently already met in Rome, he also visited Florence. A letter from Alessandro Scarlatti to Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici, written on May 30, 1705, asked the Prince

to help his son. It confirms that this musical prince was aware of Domenico’s keyboard virtuosity, but he did not employ him, as Alessandro had hoped; in his reply he said that Domenico had “truly such a wealth of talent and spirit as to be able to secure his fortune anywhere, but especially in Venice” and confined himself to recommending him to a Venetian patrician. From 1705 to 1709, before returning to Rome, Domenico Scarlatti probably stayed in Venice, where he met the Irish harpsichordist Thomas Roseingrave (1690–1766) who, deeply impressed by Scarlatti’s playing, became his admiring follower for the next four years in Italy, and later, in England, his enthusiastic promoter.

It is still unclear where Domenico Scarlatti met Handel. Thanks to the famous music patron Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, both artists met in his palace and were invited to compete on organ and harpsichord. Handel’s first biographer, John Mainwaring, reported in 1760:

“The issue of the trial on the harpsichord hath been differently reported. It has been said that some gave the preference to Scarlatti. However, when they came to the Organ, there was not the least pretence for doubting to which of them it belonged. Scarlatti himself declared the superiority of his antagonist…Though no two persons ever arrived at such perfection on their respective instruments, yet it is remarkable

that there was a total difference in their manner. The characteristic excellence of Scarlatti seems to have consisted in a certain elegance and delicacy of expression. Handel had an uncommon brilliancy and command of finger: but what distinguished him from all other players who possessed these same qualities, was that amazing fullness, force, and energy, which he joined with them.”

Wasn’t the mention of the “elegance and delicacy of expression” with which Scarlatti played a hint that he did use the pianoforte which Cardinal Ottoboni had owned since 1706?

In Rome Domenico enjoyed from 1709 to 1714 the patronage of the exiled Polish Queen Maria Casimira and from 1714 on, that of the Marquis de Fontes, the Portuguese ambassador to the Vatican, who eventually paved the way for Scarlatti’s employment as maestro di capella at the Royal Chapel in Lisbon. Before leaving Rome, however, from 1714 to 1719, Domenico was employed as maestro of the Capella Giulia in the Basilica of St Peter’s. When he abandoned this post, he allegedly announced that he would go to England; however, no evidence of his stay in London has yet been traced. There is proof, though, that in November 1719 Scarlatti arrived in Lisbon, where he spent the years 1719 to 1729 (with various interruptions for visits to Sicily, Naples

5

and Rome) as maestro of the Royal Court Chapel. This position obliged him inter alia to teach harpsichord playing not only to the young daughter of King João V, Maria Barbara, but also to the king’s younger brother, Don Antonio di Braganza. Before leaving Italy in 1719, Scarlatti apparently oversaw the acquisition by the Portuguese court of a Cristofori piano from Florence, for which King João eventually paid Cristofori the high sum of 200 Louis d’or. It is certainly no mere coincidence that Giustini’s Sonate / Da Cimbalo di piano, e forte / detto volgarmente di martelletti, printed in Florence in 1732, were dedicated to Scarlatti’s pupil in Lisbon: A Sua Altezza Reale Il Serenissimo D. Antonio Infante di Portogallo.

The ailing health and finally the death of his father recalled Scarlatti twice—in 1724 and 1725—to Italy, where in 1724 he met Quantz and Farinelli in Rome (in 1737 the famous castrato would eventually join the Spanish court) and in 1725 Hasse in Naples. He was again in Rome in 1727 and also in 1728, when he married Maria Catarina Gentili, by whom he had six children. She died in 1739, and by 1742 Domenico was married for the second time, this time to a Spanish lady, Anastasia Ximenes, by whom he had four more children. In 1729 the Portuguese princess Maria Barbara married the Spanish Crown Prince Ferdinando VI. Scarlatti was asked

to follow her to the Spanish court and accepted this offer, which freed him from his duties as maestro di capella. After a period in Seville, from 1729 to 1733, he lived mainly in Madrid until his death, apart from one possible visit to Lisbon. In Spain Scarlatti, who eventually called himself Domingo Escarlatti, composed most of his keyboard sonatas. His patroness, Princess Maria Barbara, soon ordered more pianos from Florence (she became Queen Maria Barbara in 1746). When she died, her last will and testament tells us that at least five of her instruments had been pianos, one of them equipped with both quills and hammers (cimbalo con penne e martelletti). The maintenance of Cristofori’s complicated hammer action must have created problems in Spain, and this may have been the main reason why two of her pianos were changed into harpsichords with quills only.

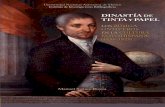

In addition to a huge list of keyboard pieces, Scarlatti left at least 17 separate sinfonias and a harpsichord concerto, to say nothing of the many vocal works he composed in Naples and Rome before coming to the Iberian Peninsula, where his music strongly influenced such local composers as Carlos Seixas and Antonio Soler. With the support of King João V of Portugal, he was created a Knight of the Order of Santiago, whose insignia Scarlatti wears in a famous portrait of about 1740 painted by Velasco.

Scarlatti “repaid” the king in 1738 by dedicating to him his thirty printed Essercizi per Gravicembalo. In a note to the reader and user of these “exercises” Scarlatti writes: “Reader, whether you be Dilettante or Professor, in these Compositions do not expect any profound Learning, but rather an ingenious Jesting with Art, to train you in the Mastery of the Harpsichord. Neither Self- interest, nor Ambition led me to publish them, but Obedience.” Domenico’s Essercizi met with great interest everywhere in Europe and his reputation increased tremendously. In London Roseingrave immediately issued a pirated edition, in which he included 12 additional Scarlatti sonatas, probably from that earlier period when he had enthusiastically followed the composer around Italy.

During his last five years Scarlatti became too ill to leave his house. A sense of detachment from the world is clearly expressed in his only surviving letter. He apparently turned to religion, which resulted in the composition of a Missa quattuor vocum and a beautiful Salve Regina for soprano, strings and continuo. He is likely to have himself supervised the copying out of his sonatas, which may have been done by his former pupil, Antonio Soler. He died in Madrid on July 23, 1757, leaving behind two large manuscript collections of the keyboard sonatas (Parma and Venice) and various other works.

© 2009 Eva Badura-Skoda

6

DOMENICO SCARLATTI’S KEYBOARD SONATAS

Recording all the sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti on the piano is an undertaking of great moment and fascination: a journey through shared cultural experience, as well as one that explores the subtle thought processes of a musical genius, with his Italianate approach to art. For this important and taxing artistic endeavor I am greatly thankful to my wife Doriana, for her loyal support.

Introduction SOURCES

The “vexed question” for anyone approaching Domenico Scarlatti analytically and with a proper concern for his language (even before showing a respectable acquaintance with the history of musical instruments) is that of the sources; that is to say, of the composer’s autographs—in this case nonexistent. Scarlatti’s music began to become more widely known in Europe after 1739, the year his thirty Essercizi per gravicembalo (Exercises for the Harpsichord) were published in London—though advertised in January 1739, the notice may possibly postdate the edition by one year. As far as dating the Essercizi is concerned, one of the sentences in Scarlatti’s dedication to João V, the Portuguese king, “these compositions first saw the light under your

gracious Majesty’s lofty patronage, in the service of your most deservedly favoured Daughter”—raises the possibility that they were written between 1714, the year Scarlatti became maestro di cappella to the Portuguese ambassador in Rome, and 1729, when Princess Maria Barbara married the son of Felipe V, the King of Spain, who would become Scarlatti’s new patron. The original edition of the Essercizi was shortly followed by Roseingrave’s augmented reprint of the same year, which added a further twelve previously unpublished sonatas. Scarlatti’s music now began to excite the enthusiasm of musicians, both professional and amateur, and of the general public: proof of the interest roused by these strange and masterly compositions in his contemporaries can be seen in the “Twelve Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti” by Charles Avison, in the many quotations and allusions in certain of Handel’s concertos, and in the way in which the writer Laurence Sterne has his Tristram Shandy describe the character of his own father, in “musicalese,” as a sort of con furia person, like Avison’s Sixth, (perhaps a useful linguistic hint for the performer as to the correct interpretation of E29?). But while eighteenth-century England’s role in the promotion and sale of music was to lead to its growing importance as an international center of musical life, in Italy, on the other hand, little or nothing was known about the son of Alessandro

Scarlatti.

Between 1752 and 1757 several hundred of the sonatas were copied out to form the two collections known today as Parma and Venice, from the cities to whose libraries these valuable manuscripts belong. We thus have fifteen volumes in Parma (463 sonatas) and thirteen in Venice (374 sonatas), both sets completed during the years 1752–1757; the Venice library (the “Marciana”) also possesses two earlier volumes, from 1742 (61 sonatas) and 1749 (41 sonatas). Adding together the 30 Essercizi, the 463 in Parma and all the remainder unique to Venice and other collections, we reach a figure far higher than the 555 sonatas in Kirkpatrick’s catalogue, 493 of them (Essercizi and Parma) in a musically satisfying sequence. During the whole of the eighteenth century Scarlatti was known by his more youthful works alone: familiarity with the later sonatas did not become widespread until the work of Carl Czerny, in his incomplete edition of 1839, and that of Alessandro Longo, who published almost all the sonatas in 1906, in an edition for piano containing many editorial additions. The first monograph, by Walter Gerstenberg, appeared in 1933, followed shortly afterwards by those of Sacheverell Sitwell in 1935 and Cesare Valabrega in 1937.

For this complete Scarlatti recording we shall be using “catalogue” numbering

7

consisting of city or edition, letters and numbers. (Parma has priority, both in order and catalogue arrangement, in the case of those sonatas that appear in other editions or manuscripts as well.) Thus we have the sigla E1-30 for the Essercizi 1 to 30 and P1:1 to P15:42 for all the sonatas in Parma. Sonatas contained in collections other than Parma and Essercizi are identified by their source, followed by the number showing the order in which they appear in that source. For example, because the letter E identifies the Essercizi, E1 is Kirkpatrick’s K1, while P1:1 means the first sonata in the first volume of Parma, i.e. K 148.

As shown by the three primary collections (Essercizi, Parma and Venice), the sonatas are almost always arranged in groups of thirty. Besides Scarlatti, the Portuguese Seixas and the Spaniards Soler and Albero also left collections of thirty sonatas, usually short and consisting of a single movement. Why were these pieces assembled in thirties? Is there a practical significance—a sonata a day for a month? Or was it perhaps symbolic? In his Memorial do Convento, the Nobel Prize writer José Saramago describes the thirty steps of a ceremonial staircase, built for João V in memory of the thirty pieces of silver for which Judas betrayed Christ. And thirty was also the age of Jesus Christ when he was baptized.

Other manuscript collections of Scarlatti sonatas—or ones that include some

Scarlatti sonatas—are referred to by the name of the city in which they are to be found: Barcelona, Bologna, Cambridge, Coimbra, Lisbon, London–Worgan (the second name comes from the eighteenth-century collector), Madrid, Milan, Montserrat, Münster, Naples, New Haven, Paris, Tenerife, Turin, Valladolid and Vienna; others bear the name of the editor (Roseingrave, Clementi) or publisher (Avison, Haffner, Johnson, Cook—linked to Roseingrave in the 1739 edition). The Essercizi is the only collection whose name is taken from its title.

It is interesting to note the way the Roseingrave and Cook edition mixes Scarlatti sonatas with unpublished movements by Roseingrave himself. Two introductory pieces, in the style of a French ouverture, set the scene for the dotted rhythms of Essercizio 8. Roseingrave’s intelligent rearrangement of Scarlatti’s sonatas offers a convincing performing order for all 42 numbers in the edition, including the final fugue, which is followed by a Minuet of his own composition. There are also a number of interesting textual “revisions,” justified here by the statement “carefully revised and corrected from the errors of the press by Thos. Roseingrave….” Given the different order of the Essercizi in this collection and the credibility of their new arrangement, we can quietly begin to trust such reorderings (Parma,

especially)—in print, on the concert platform and, nowadays, on disc—and say goodbye without regret to any claims of evident chronological order, chiefly based, as they are, on conjecture. An unfamiliar order will do no damage to the music.

Odd ornaments and notational oddities: “great curves,” trills,

“tremoli”In “The keyboard music of Domenico Scarlatti: a re-evaluation of the present state of knowledge in the light of the sources”; Brandeis University, 1970, a brilliant and painstaking investigation into the various Scarlatti MSS, Joel Sheveloff devotes considerable attention to a particular aspect of Scarlatti’s notation that he calls “great curves,” sort of non-phrasing slurs over parts of the text that may require notes under them to be left out. In modern editions this strange feature, which Kirkpatrick calls “calligraphic slurs,” is either left to be interpreted by the editor as he thinks best or simply just omitted. When these “curves” indicate a da capo, with an alternative ending for the repeat, a metrical distortion can sometimes occur (see E 18, for example). In sonata P3:4 (K 110), however, the sequence of structural units may even have to be rethought and the player might have to revise his whole strategy: omitting bars 44 and 105 would lead to a serious metrical elision and a

8

rethinking of the entire structure. This particular oddity appears in Venice 1749, but is missing from the collection known as London. That the omission of everything under the slurs (i.e. bars 44 and 105) is intentional is confirmed by the versions in Cambridge and New Haven; Parma 3, however, restores the bars in question.

In her article The notation of Scarlatti’s MSS: problems and observations (Minutes of the Scarlatti Conference, Siena 1985, in “Chigiana,” XL 1990) Emilia Fadini neither advocates nor condemns the practice of playing trills from the note above, since “As we know, Italian performance practice, like that of Spain and Portugal, did not regard the almost compulsory French way of starting the trill from the upper note as the norm. Here too, therefore, it will be up to the performer to decide whether to start the trill from the main note, the one above or the one below, with or without appoggiatura, judging from the context alone.” Deo Gratias! Trilling from the upper note is defended by traditionalists in academic circles, who respect the practice as deriving from a more codified French system of ornamentation, but we are also influenced more empirically by recordings of the great performers—Ross and Kirkpatrick especially, but also others such as the pianists Gould (for Bach) and Horowitz (for Scarlatti). The latter, in turn, under the guidance of his “teacher”

Kirkpatrick, trill from above even in an extended conjunct melodic line, which is really not the place for it—but he does it so beautifully! Nothing “on paper” is more important in music than conviction and inner coherence in performance.

Many aspects of Scarlatti’s writing (or at least what we may suppose to have originated with him) can lead in some cases to uncertainty. The word “tremulo,” for instance, which appears in the following sonatas: P3:29 (K 96), P3:27 (K 114), P3:13 (K 115), P3:9 (K 118), P2:17 (K 119), P2:29 (K 28), P5:5 (K 132), P2:9 (K 136), P2:6 (K 137), P1:25 (K 172), P1:28 (K 175, P2:12 (K 183), P2:23 (K 187), P4:18 (K 194), P4:21 (K 203), P4:22 (K 204a), P4:1 (K 208), P6:25 (K 272), P7:21 (K 291), P14:27 (K 510), P15:12 (K 525) and P15:30 (K 543), has been officially approved by Kirkpatrick as equivalent to the word “trill” and treated by him as the same ornament. We are indebted to Barbara Sachs for an article in which she reviews the credible assumptions, rather than mere guesses, that this ornament sign might demand an interpretation different from that of the trill. Whenever the instruction tremulo appears, always in the right hand, the third and fourth fingers are free, or the second and third, or in many cases all three, so that rapid repetitions are possible with those fingers. In fact, the performer, trained and tireless as he must

be if he is to storm the mighty mountain, immediately sees—and (we have to add) feels in his fingers—what is essentially a guitar “tremolo.” Such a solution is actually put forward in Nicolò Pasquali’s 1757 treatise on fingering, in which he suggests that the same note be repeated three or five times. Moreover, Christophe Rousset points out, as a sort of contre-exemple idéal to convince anyone who doubts the sign does have a precise meaning, that in one Scarlatti sonata tremolo appears no less than five times placed right above tr, which should logically disqualify the two signs from meaning the same thing. Who could take issue with him? If anything, Sachs writes, this example might suggest playing both ornaments in sequence, treating the second one as repeated notes at the end of a trill, thus reviving an ornamental formula from both the treatise of Lorenzo Penna (1672) and the keyboard music of Gregorio Strozzi (1687). Sachs thus restores the same meaning to the tremolo, i.e. the repetition of a single string, that was taught by Marini and Castello and is still valid today.

What should the performer do? Not act like a doctrinaire preacher, obviously, concerned more with the text than with its meaning, but treat the tremolo sometimes as a trill and at others as quick, light repeated notes.

9

Chronology“There is at present no evidence to controvert the astounding hypothesis that most of the remainder [beyond the thirty in the first edition, known as the Essercizi] of Scarlatti’s 554 sonatas date from the very last years of his life, for the most part 1752 onwards.” (Ralph Kirkpatrick, “Domenico Scarlatti’s Early Keyboard Works,” The Musical Quarterly, XXXVII – 1951. “Since every manuscript of keyboard music in the composer’s hand been lost and copies cannot be connected with dates of composition, no evidence existed then or exists now to overrule Kirkpatrick’s theory. The burden of proof, that dates of transmission closely approximate those of composition, always falls on the propounder. The unlikelihood of such a late burst requires something more positive than dates on scribal copies to become credible.” (Joel Sheveloff, “Domenico Scarlatti: Tercentenary frustrations,” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 71, no.4).

The two major studies contradicting Kirkpatrick’s claim to have established a chronological order for Scarlatti’s keyboard works—that of Giorgio Pestelli, based on stylistic considerations, and the one by Joel Sheveloff, comparing manuscript sources with printed editions—provoked

Kirkpatrick to a devious response (“a study in reverse scholarship,” as Sheveloff calls it), a sort of reductio ad absurdum, in which with a buffoonish logic he proposes, given the shortage of documentation, that Scarlatti did not himself actually write the sonatas, but merely prepared an outline of them for their true author, Queen Maria Barbara. He called this the “Barbarian” conjecture (reminding us of the attribution of Shakespeare’s plays to Bacon); but I for one cannot accept it as valid, in view of the strong consistency of the language in both the Essercizi and the rest of Scarlatti’s work, and the recurrent use of motives and procedures such as the ubiquitous falling tetrachord and the “walking bass” 1-5, to mention only two examples, besides the unfailingly compact structure of every piece. Such linguistic coherence does much to undermine Kirkpatrick’s argument that creative thought could possibly be expressed in sketches or simple “ground-plans” that would later be developed by a second person.

Faced with a substantial body of compositions of roughly the same length and all called “sonata,” it is fairly natural to regard them as a whole and to view each item as part of a larger set. This leads one to see each individual sonata as existing both inside and outside its own system of reference, that being the sum of the known Scarlatti sonatas. In his ground-

breaking study (“Domenico Scarlatti - Life and Works, 1953) Ralph Kirkpatrick established guidelines for a formal analysis of the Scarlatti sonata that are still valid today, even if less refined and extensive than present views. As Kirkpatrick sees it, after the exposition of the main thematic and rhythmic material, there comes in both halves of the sonata a shift to a subsidiary tonality, a point which he calls the “crux”; all events which follow are termed “post-crux.” Beyond a shadow of doubt, the “big K” had grasped the shape of Scarlatti’s sequentially repeating syntactical units, sometimes known as “interconnected tiles,” a theory that is of growing interest to scholars today.

Rita Benson and Kathleen Dale succeeded in arranging the sonatas by “form” and “mood,” while Christopher Hail, a devoted (if mysterious) “promoter” of Scarlatti, floods the internet with extremely relevant information, even going so far as to rearrange the sonatas by tonal sequence. In this “hit parade”—which concerns only the first half of each sonata—the vanguard is led by 84 sonatas whose key-structure is a simple I major, V major; these are followed by 60 built on I major, V major, and then by a group of sonatas in the minor that use the straightforward pattern I minor, V minor. Among the “unique” examples, whose key-sequence is not found elsewhere, is Essercizio 7, one of the Avison transcriptions, with

10

its I minor, V minor, IV minor, VII minor, III minor and III major. The most famous classification—controversial, admired, but in fact only found worth discussing at all because of its provocative chronology—is the 1967 study by Giorgio Pestelli, then still in his twenties, who confidently assigned an order of composition to the sonatas on the basis of their language, style and formal structure. According to Pestelli, Scarlatti’s output can be classified as follows:

1) Venice 1705-17092) Rome 1709-1719 The violin sonatas Close to the toccata In the margins of the suite The polyphonic sonatas: 1) the fugues 2) the other polyphonic sonatas3) The pre-Essercizi4) The choice a) “Essercizi” b) “… vague idea of dances” d) “Along the pathway of the toccata…” e) “…in the sphere of the étude”5) The great flowering after the Essercizi a) The “easier” style b) The “varied” style c) 1738-1745 I - Allegri alla breve; II - Ternary movements; III - Études; IV - Andanti; V - Search for remote keys6) The last decade, 1746-1757 a) The galant moment

b) Allegri alla breve c) “Simplified” Allegri alla breve d) Ternary movements e) “Amplified” ternary movements f) Études g) “Amplified” andanti h) Counterpoint in “middle style”; the shadow of Frescobaldi i) The “Werthersstimmung” j) The revival of the toccata k) The late sonatas

Tradition and innovation in Scarlatti’s musical language

Sutcliffe underlines the historical potency of “impurity” in Scarlatti’s mixed style. “After all, if Scarlatti was intent on purity, he was certainly at liberty to ignore the outside voices that seem to press in on his musical world—that is what all composers to a greater or lesser extent had always done.” This may be understood as meaning that Scarlatti did not feel competitive pressure from important figures of the previous generation (the so-called Anxiety of Influence suggested by Harold Bloom in 1973, according to which every poem can be seen as a faulty reading of an earlier one—hence the phenomenon of “strong” and “weak” poets). In the world of music, works become “relational events,” rather than “closed and static entities.”

In escaping, to a very large extent, the influence (or rather, the judgment) of his

father Alessandro, Domenico perhaps did not suffer from this kind of anxiety, thanks to his family life in Spain; on the other hand, he did not allow this newly achieved independence to reject the lessons of Italian tradition, which continued to make every work of his compact and coherent, regardless of their style or shape. Chris Willis finds “performative rhetoric which animates the Italian toccata” in certain pieces by Scarlatti that are neither anchored in, nor divorced from, Italian tradition. Scarlatti too was faced with the task of writing music similar enough to that of the previous generation to be well received by his audience, but without loss of respect for his originality. Brahms, for instance, offers us music of great originality that has no direct references to the past but, at the same time, includes deliberate (though hidden) allusions to it. These allusions serve to recall the music of his predecessors at a subconscious level, which allows his music to be regarded as very original. If Scarlatti had any “anxiety” of this kind, he disguises it—or possibly manages it—so well that we are left with a sense of balance between continuity and a break with his forerunners.

The poetic aspect of Scarlatti’s Spielfreude (delight in performing) has been described in an original way by Peter Boettinger, who speaks of “the childish pleasure of treating single notes as if they were fresh snow:

11

intact and smooth.” Hence, in joining up the notes, the adult performer could in some sense be regarded as distrustful of such naivety, with Scarlatti’s own outlook a “distrust of this dis- trust.” Summing up, we have here a case of the Peter Pan syndrome, together with the ability of a composer to create devices that are proof against both time and the instrument itself.

The concept of Finermusik (finger music), a work which Pagano uses to refer to certain procedures in Scarlatti, seems to be equally matched by that of Augenmusik (eye music); together they mark the two opposite sides of the creative process, the musical material providing the first and its elaboration (or even better, its design) the second.

Sutcliffe notes that Scarlatti often “thinks through his fingers and his inspiration comes from a symbiosis of hands and keyboard.” Valabrega writes: “Scarlatti’s creative force is striking and his musicality is of the utmost fluidity. His is an incomparable openness, a vein of Mediterranean song, shining and fluent, through which the art of the harpsichord is brought to its ultimate perfection.” An “instrumental demon,” he calls him. Is it in fact this “demon” which is at the root of those reports, ranging from mere anecdote to historically reliable accounts, that surround the figure of Scarlatti the harpsichord virtuoso? Charles Burney mentions a meeting between

Roseingrave and Scarlatti, apparently in the first decade of the eighteenth century, at a private assembly in Venice, in which our man Roseingrave was showing what he could do at the harpsichord, until “a grave young man dressed in black and in a black wig, who had stood in one corner of the room, very quiet and attentive while Roseingrave played, being asked to sit down to the harpsichord, when he began to play, Rosy said, he thought ten hundred d—ls had been at the instrument; he had never heard such passages of execution and effect before.”

More apocryphal—totally so, according to Graham Pont, the author of an article about the incident—is the story of a certain battle of the keyboards in Rome between Scarlatti and Handel, told by the biographer of the “great Saxon,” John Mainwaring. This, says Pont, is quite as unfounded as a report by Scarlatti himself (relayed again by Mainwaring) of a masked ball in Venice in which he heard somebody playing the harpsichord that “could only be the famous Saxon or the devil himself.” The theatrical aspect of Scarlatti’s keyboard music, with its element of social interaction, even provocation, is underlined with searing frankness by Diderot in a passage from his La Religieuse, which is worth quoting, as told succinctly—and with no mincing of words—by Daniel Heartz:

“In her last convent Sister Suzanne was one day taken to the Mother Superior’s room, where she was obliged to sit down at the harpsichord and play Couperin, Rameau and Scarlatti. The aged abbess, with one hand on Suzanne’s bare shoulder, went through the stages of first, sighing, then gasping and finally orgasm. Diderot leaves us to imagine the sequence of pieces that corresponded to these three stages.”

Have times changed at all?

12

NOTES by CARLO GRANTE

The last book of the Parma collection contains an exceptional number of sonatas, 42 in all. The first 30 of these comprise the 13th book of the Venice collection, and all 42 sonatas can be found in the Münster prime source (2 in book 1A, and 40 in book 1B).

The title page of Münster 1B provides an overview of the compositional period of these sonatas (1756-7), but as Christopher Hail states

“‘Composed’ could also mean edited or revised rather than completely new; I have taken that into account in attempting to assign dates to the individual sonatas. It would be nice to be able to believe the Münster title-page literally, but the source for the information is unknown. The fact that nos. 31-42 were not set aside for a Parma libro [book] 16, that they also finish Münster 1B and that none of these 12 were copied into Venice 13, certainly implies that Scarlatti had set down his sonata-writing pen for good. The Salve regina in A major is said to have been his last work (Boyd pages 202-204) and is in a different style from these sonatas. Charles Burney was shown a book of 42 pieces by Scarlatti in 1772, most of them unknown to Burney, and which their owner, L’Augier, said Scarlatti

composed for him in 1756. Burney also stated the book contained several slow movements. It is hard to believe Burney would not have recognized the Roseingrave-Cooke edition of 42 pieces. The only known manuscript which fits all these conditions is Parma 15, but it is unlikely that L’Augier ever owned it (the location of the Parma collection between 1757 and 1899 is unknown, but its condition, its freedom from annotations, and the fact that it was purchased for the Parma Palatine library from a Bologna bookseller make its provenance as part of Farinelli’s legacy believable).”

The above historical analysis prepares the context for the many questions (especially regarding the dates of composition on the one hand and the compilation of manuscript sources on the other) that inevitably accompany many of the works contained within this, the 6th volume, of the complete recording of Scarlatti’s keyboard works.

Parma, Book 15 (1756-57)This collection of Scarlatti’s keyboard sonatas was the last to be compiled. It can be considered either a single collection of 42 works, for the aforementioned reasons, or, assuming that 30 sonatas is the standard size for a collection of Scarlatti sonatas, it could alternatively be considered a

collection comprising 30 sonatas plus 12 extra. Following the publication of the “30 Essercizi,” 30 works became almost standard when compiling Scarlatti’s works, as was also the standard for compilations of other composers’ keyboard works

If one considers these sonatas to be Scarlatti’s last, Pestelli’s interesting approach of categorizing Scarlatti’s toccata-style and his Spanish style as both compositional styles and compositional periods (respectively early and late) allows the listener, performer, or scholar to identify the direction towards which the composer leans.

Furthermore, the degree to which particular Scarlattian compositional fingerprints are reiterated in a group of sonatas, and the degree of refinement of those fingerprints, can be used to determine the degree to which the works are stylistically consistent.

The first pair of sonatas, P15:1 (K.514) and P15:2 (K.515) features the use of arpeggios as initial thematic statements. Scarlatti’s use of this thematic opening is quite different than Beethoven’s famous “chord-themes,” though it did have a certain amount of influence on Clementi (of whom Beethoven was in part, in his early and middle-period piano writing, an epigone). The same arpeggiated opening can be found throughout Parma 15, in sonatas P15:16, P15:18, P15:19, P15:28,

13

P15:34, and most notably in P15:22.

The sonata that follows, P15:3 (K.517), is a rather popular “perpetuum mobile” in Scarlatti’s toccata-style. It was described by Pestelli thus: “…a rethinking of Alessandro’s [Scarlatti’s] toccata style...the Alberti bass, rather than pedestal of a melody, is here used in condition of absolute parody of rights with the other thematic devices of the music….” Clark remarks on the similarities between measure 52 of this sonata and Rameau’s “Les Cyclopes” (1724), where the same feature of reversed broken chords can be found. The indication “La que sigue se debe tañer primero” at the end of the manuscript page of P15:3 suggests that P15:4 (K.516) should in fact be played before this one, hence the position of these items in this album’s track list. The 3/8 meter, D minor Allegretto of P15:4 (K.516) readies the stage for this sonata’s turbulent companion. The stylistic fingerprint exhibited in this sonata (parallel “dancing” thirds moving in stepwise motion beneath a higher, sustained note in the right hand) can be found elsewhere in Scarlatti’s body of work, for example measures 40-61 of P5:6 (K.133).

P15:5 (K.518) is an example of the “anapest” sonatas that feature the characteristic short-short-long rhythmic unit throughout. This compositional fingerprint can also be found in sonatas P10:15-19 (K.372-376), P10:21 (K.378),

P12:14 (K.424), and P12:20 (K.441).

P15:5 (K.518)’s companion sonata, P15:6 (K.519), combines Spanish and Italian musical features. The Italian features manifest in the prolonged tonic sections which bring both the “A” and “B” sections of this sonata to a close.

Sutcliffe remarks that Parma 15:7 (K.520)’s stylistic fingerprint is a suspended/syncopated figure in the tenor voice, found in measures 48-57. Chris Willis comments on the suspension:

“... although the final arrival on the tonic is a reward worth waiting for, and will sustain us through repetitions of both halves, in retrospect it is not this but the longer and highly evocative preamble itself which constitutes the most significant and memorable ‘event’ of the compositionally similar sonatas: P14:14 (K.497); [and] P15:39 (K.552).”

Sitwell considers this the most brilliant of all Scarlatti’s “military” pieces, “…inspired by the mounting of the guard below the Buen Retiro, or other palace window, but reaching to ultimate heights of fantasy….”

Its companion sonata, P15:8 (K.521), is a mix of a siciliana and of a Spanish dance for guitar. It shares similarities with P15:4 (K.516) and P15:19 (K.532), both also found in Parma, Book 15.

Pestelli draws comparisons between the beginning of sonata P15:9 (K.522) and the beginning of Alessandro Scarlatti’s popular song “Su, venite a consiglio.” Though this comparison is remarkably insightful, I have chosen instead to portray the sonata’s more staccato, dance-like qualities in this recording as are suggested by the presence of short shakes and passagework.

In measures 1-73 of sonata P15:10 (K.523), Sutcliffe finds “...a syntactical plot involving the collision between periodic and sequential impulses—or the modern manners of a Galant style and the older ways of the learned....” The Scarlattian idioms found in this sonata include the constant use of intervallic leaps as a thematic device, and once again the ascending five-note bass figure at the cadential ending of each half of the piece.

Sutcliffe also points out the syntactically improper unit used to begin P15:11 (K.524). Scarlatti begins sonatas P3:15 (K.106), P7:2 (K.275) and P15:11 (K.524) in a similar way.

P15:11 (K.524)’s companion sonata, P15:12 (K.525), exhibits similar characteristics to, and shares a key (F major) with, the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 10, No. 2. This Beethoven sonata demonstrates typical Scarlattian two-part writing and opens (as Scarlatti’s sonatas often do) with a canon at the octave.

14

The following pair of sonatas, P15:13 (K.526) and P15:14 (K.527), are both in the key of C, although in the two different modes. The first, P15:13 (K.526), is in the minor mode and contains many features characteristic of Scarlatti’s more melancholic sonatas (three of his most poignant such works, from Parma, Book 14, are in F minor, a preferred key for this stylistic genre of his).

The light, joyous character of P15:14 (K.527) in C major provides a cathartic contrast to the sadness of the previous sonata. Pestelli notes that this sonata’s opening uses “a light Galuppi-like writing and contains one of the ‘wittiest’ among Scarlatti’s developments....”

Stylistic fingerprints found here include single-note syncopations in the right hand, which are typically decorated with short trills separated by rests that are clearly demonstrated in sonata P14:18 (K.501). Phrygian cadences, march-like left hand accompanying chords, and sudden mutatio toni (changes of mode) can also be heard in P15:14 (K.527). Scarlatti once again chooses to end both the “A” and “B” sections of this sonata with an ascending 5-note figure in the bass, just as he did in P15:10 (K.523).

The next sonata, P15:15 (K.528), is a comic, witty work punctuated throughout by hyperbolic leaps followed by its companion

sonata, P5:16 (K.529), which Pestelli notes has a “stampede” dance character. The instrumental features used in this sonata are the same ones found in the previous one; the second half is characterized by sudden changes of mood (demonstrated by Iberian guitar-like stresses on the first beat of each bar). Again—a feature often found in this Parma book—both halves of the sonata are brought to a close with the ascending five-note bass figure.

This five-note figure is also found in sonata P15:17 (K.530). Benton comments that the “distant and unanticipated tonalities used in the development are given cohesion and plausibility by the drive of the sequence” which is a feature that can also be heard in P15:30 (K.543).

I have already commented on the arpeggiated opening of P15:17 K.530’s companion sonata, P15:18 (K.531). Despite the fact that instrumental figurations in this sonata are not pattern-based, they are always coherent and recognizable. It is interesting to note that this practice is similar to Chopin’s approach to instrumental writing.

Pestelli describes the work’s unfolding thus: “it begins in the most conventional of ways, but it soon enters, on the thread of a chain of thirds, a new expressive world, made of far calls and silences.... It is maybe the only work by Scarlatti upon which a breath of

transcendence hovers....”

The sonata that follows, P15:19 (K.532) in A minor, is a Spanish dance in triple meter, “proud and beautiful in Flamenco manner with much grinding of guitars” (Sitwell). The arresting character of this sonata is underlined by the consistent use of shakes on the strong beat of each bar. Its (supposed) companion, P15:20 (K.533), is a duple-meter work in A major. This sonata is a toccata-like, etude-like piece in two parts, featuring wonderfully self-coherent instrumental writing.

P15:21 (K.534), an “Arcadian” sonata marked “cantabile” is unique within Scarlatti’s output due to the unusual harmonic structure found in the first half of the piece, not found in any other Scarlatti sonata: I-II-VII-V-v-V. The sonata’s telling character manifests through the use of several themes and their identical treatment in both halves of this work.

K.534’s companion sonata, P15:22 (K.535), presents a variety of themes, passages and moods, held together in short syntactic units. Most of the material in this sonata appears to originate in the first few bars. Its opening is a D major replica of the opening of V42:51 (K.86). K.86 is in C major and is found in an “Arcadian” setting, as is often the case of Scarlatti’s slow C major sonatas. In the opening of P15:22 (K.535), he uses D Major’s associations with the trumpet

15

to construct the arpeggiated figure into a trumpet-like exclamation.

It is unclear whether or not sonatas P15:23 (K.536) and P15:24 (K.537) were originally conceived and composed as a pair. Sutcliffe, in addressing this ambiguity, points to “registral disparities which would seem unaccountable if the two sonatas had been written at the same time and conceived as a whole.” Christophe Rousset comments, “One could imagine Scarlatti searching through the oddments in his drawers to form pairs belatedly.” He cites the F-sharp 3 in the second half of K.537, which one would expect to be transposed from the C-sharp 3 in measure 63, to illustrate his point: “Why avoid this note if it was playable two pages earlier [in P15:23 (K.536)]?” The latter of these two sonatas features a changing hypermetric organization, a technique also used in Scarlatti’s “vamp” sonata P4:17 (K.193), and his F minor “melancholic” sonata P2:27 (K.69).

P15:25 (K.538) and P15:26 (K.539) are a pair of sonatas in G major, a key often used for both dances and brilliant, extreme displays of virtuosity. Like P15:7 (K.520) and P15:9 (K.522) (both also found in Parma, Book 15), in this pair of sonatas the leading-note of the dominant is immediately flattened in the second half. The music then suddenly returns to the tonic by way of a descending tetrachord in

the tenor voice.

The sonatas P15:27-30 (K.540-43) are all in F major. According to Pestelli, measures 35-38 of P15:28 (K.541) contain a “melodic fragment...that disguises, curiously, possibly inadvertently, another Christmas chant, known as Pastorale by Couperin.”

This syntactically idiosyncratic sonata is formed of contrasts and melodic “blanks.” Suttcliffe describes it as a work “that strongly suggests the contingent nature of musical time.” The dominant material in this sonata first appears in bar 19 and is the least thematically distinctive music in the whole piece. It consists of a routine left-hand figuration, and a two-chord shape in the right-hand of which the purpose is unclear. One could argue that the right hand merely punctuates the hectic repeated accompaniment without diverting or distracting from the accompaniment’s course.

The right hand also suggests cadential closure—note the sudden use of a thicker texture and trills—however the left hand does not acknowledge these repeated cues. Scarlatti is effectively building the emotional and musical core of the piece around a syntactically meaningless accompaniment.

Ironically, the phrase from measures 19’2 to 27’1 is a perfect eight bars in length,

in contrast to the characteristic opening “stampede” that plays with rhythmic nuances within the framework of a two-part idiom. Could Scarlatti be asking us to “fill in our own melody” from bar 19?

Parma 15:30 (K.543) is the last item in the last book (book 13) of the Venice collection. Though it stands alone as a closing work, it can also be paired with the sonata that follows it in the Parma collection, P15:31 (K.544); this piece is, according to Bojankino, “caught up in the threads of an indefinable malaise suggesting a sort of tedium that musical expression had most certainly not known before.” The use of shakes on certain notes suggests a deliberate attempt to alter the piece’s contemplatively serene and introspective atmosphere, replacing it with a sense of unrest.

The sonata P15:32 (K.545) is closely related to several sonatas in Parma, Book 15. It is paired with P15:31 (K.544) by way of a common key (though P15:32 employs a slower tempo), and, with sonata P15:24 (K.537), forms a pair of transversal, etude-like pieces connected by the typological consistency of the instrumental writing used within. P15:32 (K.545) is also closely related to sonata P15:34 (K.547). Not only do the two sonatas share a common key, each half of each sonata closes in a similar manner.

16

Scarlatti’s unique style of keyboard writing goes beyond the traditional two-part “Italian writing” that typifies 18th-century Italian keyboard literature. The early sonata E4 (K.4) provides a typical example of his style; parts appear and disappear (a feature that became not only characteristic of Chopin’s keyboard writing but also a Debussyste fingerprint), single voices are split into two, and sequences of broken intervals (often with inversions and changes of direction) are frequently used. Landowska even finds similarities with the opening of J.S. Bach’s Prelude No. 8 in D-sharp minor (from the 2nd book of the Well-Tempered Clavier).

Sutcliffe comments that the next sonata, P15:33 (K.546), is imbued with a “certain sense of fatalism, of a melancholia ritually expressed.”

This is followed by P15:34 (K.547), an amplified “Allegro alla breve.” In spite of this work’s resemblance to early sonatas in the Parma collection (due to the use of imitative horn and trumpet calls), Pestelli categorizes it (along with sonatas 1, 5, 9, and 26 of Parma, Book 15) as coming from the final period of Scarlatti’s compositional output.

The next sonata, P15:35 (K.548), is notable for the mix, coalescence and clash of styles found therein. Ample commentary on the work can be found in Sutcliffe’s

scholarly work on Scarlatti, in the chapter “Heteroglossia.” He writes,

“For all the apparent refinement of notation, what the ear accepts is the insistent repetition of a melodic cluster that always sounds dissonant against the changing harmonies. The following texture, featuring purely diatonic sixths in the right hand and bass octaves, with a clean gap between the hands, forms an effective antidote to this exotic display. The strange melodic cluster is an outcrop of the previous material, specifically the flourish heard every two bars from bar 22’1.

The cluster is briefly heard again at bar 40, followed by a reintroduction of the syncopations from 22, in a passage that seems like a parody of the exotic. (Note the rough voice leading at bar 43, which is even more apparent at 48.) It may not be that, but it does lighten the mood by being less static. Such apparent jauntiness should not necessarily be thought of as antithetical to flamenco, which involves more than just pain and harshness; the ‘sadness’ of cante jondo is a ritual aspect of its expression, not unlike what one finds in the blues. It might be preferable to think of Scarlatti as moving between more or less stylized forms of the idiom; this is in any case inevitable, given the

very act of composition and its high-artistic context. Stylization is also tied up with the question of how the composer ‘hears’ his source material.”

The tertiary modulation from G major to E-flat major in the next sonata, P15:36 (K.549), directly links Scarlatti to Beethoven and Schubert. Scarlatti not only employs this unusual modulation in the left hand, he also embellishes the sonata with sustained trills, and writes passagework spanning five octaves.

The conjunct, ascending triplet figuration in Parma 15:37 (K.550) sounds, during its first utterances, like a decorative dance element. It then develops into fully complete ascending scales, all the while retaining the triplet rhythm. This development is both genuine and ingenious—one can clearly appreciate why Brahms liked Scarlatti’s music so much. This ascending interval of an octave eventually became a musically theatrical gesture, developing into a “dominant arrival” that is so typical of Beethoven’s music.

Its companion sonata, P15:38 (K.551) could be dubbed a “courtly sonata,” elegantly dancing and entertaining, delicate and witty, expressive and at times thoughtful. Scarlatti excels in writing stylistically idiosyncratic music. Sutcliffe comments

“Often such contexts feature light, half-heard collisions, as in Ex. 5.5, from

17

the Sonata in B-flat major, K.551. In bar 39 two scales, one travelling twice as fast as the other, are superimposed, leading to all sorts of strange parallel intervals. The effect is particularly noticeable given the straightforward obedient imitation between the hands in the previous three bars.”

This sort of refined keyboard heterophonia is exemplified in the long descending scales of Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto found directly preceding the solo before the coda. The pianist Maurizio Pollini, though referring to a passage a few measures later, remarked upon the dissonances produced by piano and orchestra due to such harmonic asynchronicity.

Christopher Hail comments on the French characteristics featured in sonata P15:39 (K.552) thus: “the off-beat notes held within broken chords in mm. 66-72, for example, are present in many Couperin pieces: Les juméles, 12ême ordre, 1716, to give a single example.”

Sonata P15:40 (K.553) was considered by Pestelli to be “an exception in this last group of sonatas.” It is written in F minor which is the relative minor key of the F major sonata [P15:41 (K.554)] which follows. Sitwell describes P15:41 (K.554) as, “a kind of passepied or step dance,” whereas Pestelli considers it an “audacious experimentalism. Its beginning

is something unique” and he continues, saying it is “almost a game: born out of the pleasure of closing in a circle the intervals of thirds contained within two octaves from one C to another.”

For the aforementioned reasons, the final sonata of Parma, Book 15, P15:42 (K.555), should be viewed as neither the closing piece of this particular assembly of works, nor of the Parma collection. Its opening is reminiscent of the “flamboyant” P2:16 (K.120) sonata; according to Sitwell, it features “A neat ‘Northern’ start, then change of climate to the serenading south...”

Venice 1742 and Venice 1749The Venice 1742 prime source is a collection of 61 sonatas compiled in 1742. In line with the labelling system adopted in the Essercizi and the Parma sonatas, these sonatas are labelled with the alphanumerical formula V42, followed by the number of the item in the collection, and then the K. number in parentheses. Many sonatas in this collection also appear in the 15 books of the Parma collection (compiled between 1751-2? and 1757), and the 13 books of the Venice source (compiled 1752-1757). This overlap between collections and dates allows us to cross-reference sonatas and attempt to guesstimate their dates of composition. Of course, following an Ante Quem criterium we can see that none of

these sonatas, many of which appear in the large Parma and Venice collections, could have been composed after 1742.

33 sonatas from Venice 1742 do not appear at all in the Parma collection (which was used as the reference collection for this complete recording). Rather than appearing in this recording in a musically satisfying order, as the Parma sonatas do, these Venice 1742 sonatas appear on the track list in the same numerical order as they are found in the source. The “missing” numbers are the numbers of sonatas also present in the Parma collection, which can be found elsewhere in this complete recording.

Despite the fact that some scholars perceive a more frequent use of an “older,” Italianate stylistic approach in these sonatas, by 1742 Scarlatti had already spent many years in the Iberian Peninsula and many of his well-known idiosyncratic features can be found in these sonatas. One Italianate feature found throughout this Venice collection is a style of compositional writing called “melo-bass” by William Newmann. Melo-bass is a work (or part of a work) written in two-part writing with an accompanying bass exhibiting melodic features (as opposed to a continuo bass line). Bearing this aesthetic principal in mind, we can take the presence of a figured bass to be external evidence of Scarlatti’s “continuo sonatas.” Examples include the “Polonaise-Minuet”

18

V42:37 (K.73), the Zipoli-like V42:45b (K.80), the “viola d’amore” sonata V42:55 (K.90), and the “violin sonatas” V42:46 (K.81), V42:54 (K.89), and V42:56 (K.91). V42:56 (K.91) is also a “trio” sonata, like V42:53 (K.88). Other “melo-bass” sonatas seem paradoxically to create harmonic completeness within a minimalist two-part texture, demonstrated in the numerous “Galant” sonatas found in Parma book 8 (included in volume 3 of this complete recording). This harmonic completeness is often achieved by the motion of each part to fill the rhythmic voids of the other, as is the case in the aforementioned sonata V42:37 (K.73).

Sonata V42:42 (K.77), though void of any continuo indications, leaves enough space and fantasy to possibly be considered a work for a one-part (string or wind) instrument with keyboard accompaniment. In this recording, these “continuo sonatas” (albeit with continuo indications only sparingly noted in the score) have been performed with very conservative, and at times rarefied harmonic fillings in order to preserve the melo-bass nature of the music and its top-bottom contour as clearly and authentically as possible. Why use a modern piano, and not a harpsichord, as a continuo instrument for this Baroque music? The argument in favour of an instrument with the ability to produce both nuances and terrace dynamics is musically self-evident

and, in the case of sonata V42:53 (K.88), is justified by the presence of forte and piano dynamics in the manuscript. These may provide external evidence missing in similar sonatas by Scarlatti.

The frequent occurrence of sonatas with “Italianate” features in Venice 1742 has led some to suspect that works exhibiting the contemporary Italian compositional styles of the day may belong to Scarlatti’s earlier period (though by the year 1742 Scarlatti had lived on the Iberian Peninsula for almost two decades). Scheveloff says that sonatas V42:10 (K.52) and V42:58 (K.92) form a group with sonatas E8 (K.8), P2:27 (K.69), P5:22 (K.147) that seems “arranged from some sort of large homogeneous ensemble work, like a string fantasia or concerto grosso.” The works certainly exhibit a striking stylistic similarity, especially among those from Venice 1742, in which P2:27 (K.69) appears as no. 32. Incidentally, these three Venice 1742 sonatas (Nos. 10, 32, and 58) all use the 4-part “luthée” style, as well as a “blue” mood. They seem to indicate a Scarlattian reminiscence of the Baroque styles that still dominated on the Continent. This use of counterpoint is the freest one can find in this period and is often syncopated. It is integrated into Scarlatti’s unique sense of melody and cantabile style. Several other sonatas can be assumed to be the product of a composer still influenced by

trending continental styles. The sonata V42:17 (K.59) resembles V42:19 (K.60) (which sounds like a Galuppi allegro), due to its typical brilliant 2-part writing (like a courant by Zipoli, says Pestelli) and with its swift harmonic rhythm (the cadential close in the first half resembles that of the first published sonata, E1 (K.1)). Sonatas V42:23 (K.63), “Capriccio” and V42:24 (K.64) “Gavota,” clearly pay homage to continental practices. According to Pestelli, both works, along with V42:38 (K.74) “may belong to an overall type of gavotte, given the original title [of No. 24] and the strong rhythmic similarity that unifies the three sonatas, regardless of the fact that [No. 23] is called ‘Capriccio,’ a term here conventionally used, not a stylistic reality.” According to Chase, however, one can find “evidence of the guitar technique ... in Scarlatti’s predilection for building up chords with fourths instead of thirds (a conspicuous instance, among many is ... [V42:24] ...).”

The passacaglia-like sonata V42:20 (K.61), despite having no real ostinato bass line, puts one in mind of Scarlatti’s big Fandango; Scarlatti gives a sense of rhythmic acceleration within this sonata thanks to successive diminutions in the variations.

Another Italian sonata is V42-51 (K.86), which, according to Suttcliffe, “suggest a Corellian trio sonata.” Georges Beck argues that this is really an allegro, not an

19

andante (as indicated in the score). His argument is supported both by its similarity to the brilliant D major sonata P15:28 (K. 535) and other gestures that could lend themselves to an allegro rendering. I have not followed such hints in this recording, in favour of preserving an “Arcadian” feel (as exhibited in other C major sonatas). The stress placed on higher melodic notes is the primary element of inspiration and requires the sonata to be played at a slower tempo. The style of sonata V42:57 (K.31) brings the listener to Venice. Its thematic suggestion, says Pestelli, “... seems to originate equally in a Concerto [opus 3:8, 1712] by Vivaldi and in Toccata by Alessandro Scarlatti.” Sonatas V42:16 (K.58) and V42:47 (K.82) are fugues and fugue-like works taking elements from continental traditions.

Another sonata with a concerto-like beginning is V42:41 (K.37), which, like V42:9 (K.51) is a 2-part etude. Both sonatas feature similar imitating arpeggios.

Etude-like pieces such as V42:26 (K.65) that puts one in mind of Clementi’s Etude No. 47 by using the same ingenious device to bring out a tune using alternating hands, V42:50 (K.85) which has a 2-part allegro finale, and V42:45a (K.79), a brilliant G major sonata, show four different sides to Scarlatti without once exhibiting Iberian influences. V42:49 (K.84), with

its thunderous, pre-Beethovenian style, is possibly the most original item in this whole collection. Sonata V42:9 (K.51) is, however, an entirely different case. It is also an etude-like piece, but it does exhibit Iberian influences due to the use of a Phrygian cadence on the dominant (in a sudden minor mode).

V42:3 (K.45) is an example of stylistic “bilingualism” in that it uses both clear, orderly toccata-like Italian writing, and the unsettling (but interesting) ruptures, staggered voices, changes of moods, and removed accents typical of Scarlatti’s musical heteroglossia.

The sonata V42:21 (K.62) exhibits a quintessential feature described by Pestelli “of that type of sonata dear to Scarlatti, called [by Della Corte & Pannain], lo Scherzo in uno....” In this type of writing, a chord (usually only in one hand) is reiterated on each beat of a bar in ternary meter. The other hand moves melodically or, in certain instances, as a ground bass.

V42:29 (K.67), in F-sharp minor, bears a strong resemblance to one of the Essercizi, E25 (K.25). The two pieces share a key and exhibit the same moods and a similar style of writing. Though the harmonic structure of both works is different, they have a sense of mutual instrumental complementarity. This 2-part writing consists of mostly eighth notes in one hand and sixteenth

notes in the other. The hand playing the more melodic part is different in each sonata.

Other sonatas that seem to look to more conventional continental Baroque styles are V42:34 (K.70), a 2-part finale allegro, V42:36 (K.72), which is a Bach-like prelude comparable to WTC II – 2), V42:48 (K.83) a 2-part polyphonic exercise, V42:30 (K.68), a minuet, V42:40 (K.76), a 2-part prelude with added voices coming from nowhere (a typical Scarlattian feature, like a sonic equivalent of Escher’s drawings), and V42:58 (K.92), which uses a dotted rhythm also found in E-flat (K.8) and P5:21 (K. 238). This rhythm perhaps signifies an “older style” such as a French overture or a Portuguese musical idiom. Hail finds in it “the grand and tragic baroque style of some of the slow arias in Handel’s operas, ‘Cara speme’ from Julius Caesar (1723) for example.”

V42:28 (K.66) presents unmistakeably Scarlattian features. It begins with musical laughter, followed by repeating short syntactic units. It presents triplets both as ground units and as broken chords above an accompaniment.

All 42 sonatas (except for V49:4 (K.102), V49:5 (K.103)) in the manuscript collection known as Venice 1749 (from the year of compilation) appear in Parma books 1, 2, 3 and 5. According to Pestelli,

20

V49:4 (K.102) is “one of the sonatas which contains an allusion to a Christmas song known as the Pastorale of Couperin: mm. 29-36.” V49:20 (K.117), according to Vignal,

“...takes on an unexpected dimension and size, following a procedure which will become inconceivable with Haydn and Mozart. At bar 14, the opening idea is reprised in the dominant, which, for an ear used to the classicism of Vienna, would seem to indicate a rather short first section. Yet the first section has 83 bars, and the second is just as long.”

Miscellaneous sourcesThe remaining sonatas in this final volume of the Scarlatti’s complete keyboard sonatas do not belong in any of the Parma or Venice collections. They are instead found in smaller assemblies of works by Scarlatti (often alongside works by other composers). Some were previously catalogued by Kirkpatrick, others were reprinted by Sheveloff in his seminal book, The Keyboard Music of Domenico Scarlatti: A Re-Evaluation of the Present State of Knowledge in the Light of the Sources (Brandeis University, Ph.D., 1970 Music), without a K number. As previously mentioned, the Roseingrave-Cooke collection of Scarlatti sonatas was edited by Thomas Roseingrave and printed by B. Cooke in

1739. Roseingrave-Cooke sonata no. 6 (K.32), in D minor, could well be an “aria of similitude,” representative of emotions or situations presented by 18th-century Italian opera librettos. If this music were to be set to words by Metastasio, they could not be more representative of an irreparable loss than “Io dico all’antro addio.” Spontini’s setting does not evoke painful emotions to the extent that Scarlatti’s music does in this slow minuet, which is possibly the saddest music he ever wrote. Roseingrave-Cooke sonata no. 9 (K.34) is another slow minuet, sad and thoroughly exhaustive in spite of the scarcity of its materials. Roseingrave-Cooke sonata no. 12 (K.35) is a beautiful, Paradisi-like two-part toccata that invites the interpreter (as it certainly did in this recording) to eschew motor-like inevitability in favour of expressing the melancholic mood. Roseingrave-Cooke sonata no. 28 (K.39) has the ability, according to Suttcliffe “...for present purposes, of corresponding to most listeners’ idea of a typical piece of Scarlatti.” Three of its most recognizable features include a typically Baroque perpetuum motion, the reiteration of short units, and audacious instrumental writing (the opening, with pairs of notes played repeatedly in alternating hands, is also found in E24 (K.24)).

London 14248 is a collection found in the British Museum (manuscript 14248)

that, aside from one piece by Domenico Scarlatti, also contains pieces by Corelli, Durante, Handel, Muffat, Pasquini, and Alessandro Scarlatti, among others. The opening of this sonata is only dubiously Scarlattian; its fugue-subject sounds rather Bachian, especially the answer at the subdominant and its thematic gestures (all too similar to Bach: D minor fugue BWV 565 for organ—too obvious to sound like a Scarlattian idiosyncrasy). In spite of this, the sonata as a whole is a small Baroque keyboard masterpiece.

Fernando and Maria Barbara are mentioned on the title page of the London-Worgan collection, so we know that it was compiled after 1746. John Worgan edited 24 sonatas from this collection which were published in London (12 in 1752 and 12 in 1771), hence the London-Worgan name. Though Sebastian Albero’s name also appears beneath the title of this collection, it was later removed. The four sonatas included in this recording have K numbers but do not appear in any other collection. The most famous of these, London-Worgan 41 (K.141), is the so-called “Toccata” (though Scarlatti did not give it that title). This sonata exhibits more Iberian influences than any other sonata in this album, though it is usually performed as a showpiece. Its exoticism comes less from the guitar-like repeated notes, but rather the rasgueado effects and the frequent,

21

reiterated Phrygian cadences. The other three sonatas are eloquently Scarlattian due to the presence of quintessential and familiar features, including the use of grace notes and reiterated short motives (London-Worgan 42 (K.142) and London-Worgan 43 (K.143)), and a near-arcadian sonata, this time in G major (London-Worgan 44 (K.144)).

Due to similarities with the handwriting used for Bologna 1:10 and Münster 3:59 (both of which are the same sonata, P12:1), Hail believes that Scarlatti was the scribe of both Bologna 1 and Münster 1-3. Hail believes that the Bologna sonatas were written thirty years earlier than the Münster ones, which accounts for the several striking differences which occur between sonatas appearing in both versions. The Bologna sonata included in this recording does not have a K number. Though it is less self-coherent than other fugues in Scarlatti’s output, it is a successful example, nonetheless.

The Münster collection consists of five volumes containing 358 Scarlatti sonatas in total. The four sonatas recorded here demonstrate four of the composer’s stylistic traits. Münster 2:51 (K.452) is an “Arcadian” sonata in a slow minuet setting. Münster 2:52 (K.453) is a beautiful “anapest” sonata. Münster 5-21a is an interesting “Galant” sonata that is too “Galant” to be by Scarlatti, as is indicated by the abundant use of left-hand Alberti-

bass. (To my ears, of all Scarlatti’s sonatas, K.95, despite being catalogued by Kirkpatrik is, aside from Münster 5-21a, the least Scarlattian.) The final Münster sonata included on this recording is a beautiful, effective, melancholic sonata in E minor (Münster 5-22 (K.147)).

The Milano-Noseda collection includes both a toccata attributed to Alessandro Scarlatti, and a Giga which Pestelli attributed to Domenico Scarlatti. The beautiful sonata “L22-8,” included in this recording, is possibly the most Scarlattian of all the works brought to light in Scheveloff’s book. It is a short compendium of Scarlattian features, including typical changes of mode (and mood), short and telling melodic gestures, and near-vamp ostinato reiterations.

The New Haven collection can be found in the library of Yale University’s School of Music. Sonatas 13-24 of this collection were likely composed before 1749, as many of them appear in the Venice book of the same date. It is possible that they were copied directly from the London-Worgan manuscript, as they all appear in the London-Worgan collection but do not duplicate Worgan’s publications of 24 sonatas from the collection in 1752 and 1771. Sonatas 25-31 were likely copied at the same time, though an original source for them as a unit is unknown. Sonata no. 28 of this collection is dated 1754 when it also appears in Münster 4, and sonatas 29-

31 could have been written after 1757 if they were by Soler rather than Scarlatti. In spite of this, the New Haven collection itself was not compiled until 1771 at the earliest.

The Boivin-LeClerc collection is known for Elisabeth Catherine Boivin, a Parisian bookseller whose name appears on the title page of each volume in the collection, though it was probably edited by Charles-Nicolas LeClerc (who also obtained publishing privileges). It is difficult to date the volumes in this collection as so few original copies remain. The absence of any Scarlatti editions in Boivin catalogues from 1737 and 1738, and their sudden appearance in catalogues from 1742 (BL 3-4 appear in LeClerc’s 1742 catalogue, and BL 1, 3, and 4 appear in the 1742 Boivin catalogue) has affected the way some scholars choose to date the work. Christopher Hail suggests that they could all be dated, arguably, 1738. The sonata Boivin III, 1 is a Baroque perpetuum mobile exhibiting typically Scarlattian features (especially in the audacious keyboard writing) that leave little doubt as to its authenticity. Boivin V, III, sounds like a sketch for Boivin V, III, 10. Both sonatas sound like “juvenile” works composed when Scarlatti was still living in Italy, without the influence of Iberian music.

The Haffner collection was compiled in 1754. The first four sonatas in this collection appear in Venice 1749, and all

22

the sonatas in the Haffner collection can also be found in Parma book 2. This C major sonata (Haffner 5) appears to be a successful amalgamation of two sonatas; one by a Galant composer and the other by Domenico Scarlatti. It is a delightful piece worthy of inclusion on this album.

The Paris-Arsenal collection comprises 13 remaining sonatas from what was originally a collection of 24 sonatas attributed to Scarlatti known as “Musique italienne.” The sonata recorded on this album exhibits many Scarlattian features, namely the “nervous” embellishments on strong beats that contradict the otherwise calm or sad mood of the piece.