The Pathophysiology of Aldosterone in the Cardiovascular System

Integration of Racial, Cultural, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Factors Into a Gastrointestinal...

-

Upload

hms-harvard -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Integration of Racial, Cultural, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Factors Into a Gastrointestinal...

E

IG

HRA

*a*

Bocingsrtftfeat2aow2ictpcdcboi

Dseeriwwem

CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY 2009;7:279–284

DUCATION AND TRAINING

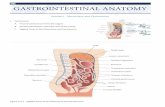

ntegration of Racial, Cultural, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Factors Into aastrointestinal Pathophysiology Course

ELEN M. SHIELDS,*,‡ DANIEL A. LEFFLER,*,‡ AUGUSTUS A. WHITE III,‡ JANET P. HAFLER,§ STEPHEN R. PELLETIER,‡

ICHARD P. O’FARRELL,*,‡ ROXANA LLERENA–QUINN,� JANE N. HAYWARD,¶ SHEILA SALAMONE,#

NDREA M. LENCO,# PAOLA G. BLANCO,*,‡ and ANTOINETTE S. PETERS‡,�,**

Division of Gastroenterology, ¶Media Services, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; �The Academy Center for Teaching and Learning,# ‡ §

nd the Office of Curriculum Resources, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; Tufts University Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; and the*Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Boston, Massachusetts

mesct

bii3diimdtpWcd2od2

twe

dd

ackground & Aims: Our study describes a faculty devel-pment program to encourage the integration of racial,ultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic factors such as obesity,nability to pay for essential medications, the use of alter-ative medicine, dietary preferences, and alcoholism in aastrointestinal pathophysiology course. Methods: We de-igned a 1-hour faculty development session with longitudinaleinforcement of concepts. The session focused on showinghe relevance of racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomicactors to gastrointestinal diseases, and encouraged tutorso take an active and pivotal role in discussion of theseactors. The study outcome was student responses to coursevaluation questions concerning the teaching of culturalnd ethnic issues in the course as a whole and by individualutorials in 2004 (pre-faculty development) and in 2006 to008 (post-faculty development). Results: Between 2004nd 2008, the proportion of students reporting that “Issuesf culture and ethnicity as they affect topics in this courseere addressed” increased significantly (P � .000). From006 to 2008, compared with 2004, there was a significantncrease in the number of tutors who “frequently” taughtulturally competent care according to 60% or greater ofheir tutorial students (P � .003). The tutor’s age, gender,rior tutor experience, rank, and specialty did not signifi-antly impact results. Conclusions: An innovative facultyevelopment session that encourages tutors to discuss ra-ial, cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic issues relevant tooth care of the whole patient and to the pathophysiologyf illness is both effective and applicable to other preclin-

cal and clinical courses.

isparities in health care are pervasive.1– 8 In an attempt tofoster the provision of consistent and equal care, medical

chools have been encouraged to address and discuss from thearliest stages differences of race, culture, ethnicity, and socio-conomic status and how they impact the patient–physicianelationship, as well as the understanding and management ofllness to provide consistent and equal care.9,10 To determinehether preclinical and clinical courses at our medical schoolere addressing issues of culture, socioeconomic status, and

thnicity, the newly formed Cross Cultural Care (CCC) Com-

ittee in the fall of 2003 petitioned the medical school assess-ent group to add 2 questions to the anonymous studentvaluation forms. The questions were designed to measuretudents’ perception of the frequency of teaching issues ofulture and ethnicity in the overall course and in the individualutorial groups.

The Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology course was invited toecome the first course at Harvard Medical School to explicitly

ntegrate the discussion of social, ethnic, and cultural factorsnto the pathophysiology tutorials. In 2006, we designed a0-minute program to teach tutors how to interweave theiscussion of racial, cultural, socioeconomic, and ethnic issues

nto tutorials. We specifically addressed the issues of obesity,nability to pay for essential medications, use of alternative

edications, alcoholism, and culturally and ethnically relatedietary preferences. These factors were picked because we believedhat these issues are central to the discussion of both the patho-hysiology of illness and to excellent care of the whole patient.hen our 2006 results showed that we had improved tutor dis-

ussion of CCC but the results did not reach significance, weesigned a full-hour program for tutors with modified triggers in007 and used this program again in 2008. This article describesur 1-hour intensive faculty development program with longitu-inal reinforcement for training tutors and compares it with the004, 2006, 2007, and 2008 data.

MethodsFormat of the GastrointestinalPathophysiology CourseThe Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology Course includes

wo to three 90-minute, problem-based learning tutorials eacheek with 7 to 9 students and 1 tutor.11 In 2006, we modified

ach of the course’s 3 cases by adding CCC discussion triggers.

Medical Student Subcommittee ReviewAfter setting up the tutorial case triggers in 2006, we

ecided to modify them slightly in 2007 to improve the ease ofiscussion. We asked a group of students interested in CCC to

Abbreviation used in this paper: CCC, cross-cultural care.© 2009 by the AGA Institute

1542-3565/09/$36.00

doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.012rew

Cecttbtfb

4Sgoifdsiatr

PdWdtefwrfttsppa

rdfdeC

Fao(g

yaTqtvRaprfpcbpanFtpopthcdw

mwwpm

Fafy

280 SHIELDS ET AL CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY Vol. 7, No. 3

eview our proposed modifications. The committee reviewedach case and gave us helpful feedback. An acknowledgementas given to each student at the end of each case.

Triggers Added to Existing Tutorial Cases in2006 and Modified in 2007Tutorial case 1. The case focuses on a 39-year-old

aucasian janitor with severe reflux esophagitis, Barrett’ssophagus, and high-grade dysplasia. The triggers added to thisase were massive obesity and the patient’s inability to pay forhe proton pump inhibitor medication. The addition of theseriggers provided a forum for the discussion of physicians’iases in dealing with obese patients. It also guided the studentsoward a practical solution for obtaining essential medicationsor patients who are unable to pay for them through a hospital-ased Medication Assistance Counselor.

Tutorial case 2. This case details the illness of a2-year-old Chinese American travel agent with Crohn’s disease.he eventually needs an extensive ileal resection, but after sur-ery her diarrhea worsens despite the use of cholestyramine. Inur revised case, the patient is found by the hospital nutrition-

st to be taking a Chinese herbal preparation sent to her by heramily in Hong Kong that contains senna, a cathartic. When sheevelops oxalate kidney stones, her dietary preferences are re-pected with ethnic foods that are low in oxalate. The herbal pills used as a trigger to encourage discussion of stereotyping andlternative medicine use as well as the diagnostic and therapeu-ic confusion that can occur if alternative medicine use is notecognized.

Tutorial case 3. The third case describes a 75-year-oldolish pipe fitter with Hepatitis C who is a daily and heavyrinker of alcohol with his buddies at a Veterans of Foreignars (VFW) Post. The new triggers added were Polish ethnicity,

rinking with his buddies at the VFW Post, and his reluctanceo go to Alcoholics Anonymous. The patient’s insistence onating heavily salted foods had been present previously, but theood choice was switched to snacks he could readily obtainhile drinking at the VFW Post. We focus on helping students

ecognize that the war trauma involved and the close cultureormed among his friends at a VFW Post could serve as a barriero his stopping drinking. The emphasis is placed on the mul-iple resources and organizations that are available to help himtop drinking and the importance of abstinence to improve hisortal hypertension. We also discuss his cultural and dietaryreferences for salty snacks that contribute to his worseningscites.

Faculty Development SessionThe 30-minute faculty development session in 2006

esulted in improvement in CCC discussion, but when theseata did not reach significance we created a 1-hour eveningaculty development session that presented racial disparity data,iscussed the relevance of triggers to pathophysiology, andncouraged tutors to make up their own questions to stimulateCC discussion.The 1-hour faculty development session consisted of 5 parts.

irst, there was a 5-minute overview defining cross-cultural carend its relevance to clinical medicine (A.S.P. and R.L.-Q.). Sec-nd, there was a 10-minute discussion by the course directorH.M.S.) on disparities in health care and their relevance to

astrointestinal diseases.12–15 A review of the baseline and prior sears’ tutor data for an active CCC discussion was presented asway of encouraging tutors to improve their own performance.hird, interactive learning groups of tutors developed their ownuestions to use in their tutorials to promote the discussion ofhe CCC case triggers. At the end of the 15-minute time inter-al, the questions were put on the blackboard and copied by.L.-Q. for later distribution to the tutors. The fourth part was10-minute overview presented by H.M.S. on how to interweaveathophysiology and the trigger elements. Specifically, the dataelating obesity to a higher risk of reflux and of increased riskor adenocarcinoma of the esophagus were reviewed. The im-act of a Crohn’s patient taking a Chinese herbal preparationontaining senna, a known cause of melanosis coli which maye recognized during colonoscopy, was discussed. The im-roved 5-year survival and decreased portal hypertension in anlcoholic if he/she can be convinced to stop drinking and theeed to curtail salt for control of ascites were discussed.16 –23

inally, there was a 20-minute review of a 5-minute mockutorial video of one of the tutors (D.A.L.) discussing case 3 (theatient with alcoholism and hepatitis C) with a volunteer groupf students. The discussion focused on the difficulty of stop-ing alcohol drinking and what options are available to assisthe patient in his attempts to stop drinking. The video showsow to guide the discussion of CCC material. After the videooncluded, tutors reflected on how they could lead a similariscussion with the questions they had just developed. Tutorsere given readings on cross-cultural care.24,25

Weekly Tutor Meetings With ReinforcementBeginning in 2007 and continuing in 2008, we held a

eeting for tutors each week in which 10 minutes of the hourere devoted to tutors’ discussing their anecdotal experiencesith attempts to weave cross-cultural care issues into the patho-hysiology tutorial. An expert facilitator was available at eacheeting (A.S.P. or R.L.-Q.).

igure 1. Students’ perception of the statement, “Issues of culturend ethnicity as they affect topics in the course were addressed” asollows: frequently, sometimes, or never. Compared with the baselineear of 2004, the proportion of students noting “frequently” increased

ignificantly for 2006 (P � .000), 2007 (P � .000), and 2008 (P � .000).aitastcps

2Tamifsca

i2

qt2ictfc

wtadi

odace

Ftnsic

Ft2b

March 2009 INTEGRATION OF CULTURAL AND ETHNIC FACTORS 281

EvaluationWe analyzed student responses to the same 2 questions

bout the teaching of culture and ethnicity issues that werencluded in all course and tutorial evaluations. The first ques-ion asked, “Issues related to culture and/or ethnicity as theyffect the topics in this course were addressed,” as part of thetudents’ overall evaluation of each course. The second ques-ion asked, “This tutor actively teaches culturally competentare,” as a component of the students’ tutor assessment. The 3ossible responses to both items were as follows: frequently,ometimes, or never.

Although the school evaluated CCC teaching beginning in004, we did not initiate formal curricular changes until 2006.herefore, the 2004 data, unbiased by any interventions, serves a baseline against which the 2006, 2007, and 2008 data areeasured. To understand changes in frequency of CCC teach-

ng, we also analyzed the personal characteristics of tutors whorequently discussed cross-cultural care to determine whetheruch tutors differed in age, sex, teaching experience, rank, spe-ialty, or teaching grades from those who did not discuss CCCs frequently.

Approval for these studies was obtained from Harvard Med-cal School’s Committee on Human Studies in 2006, 2007, and008.

Data Analysis and Statistical MethodsWe analyzed anonymous student responses to the 2

uestions described earlier by using 2-tailed Z tests for propor-ions and compared 2004 data with data collected in 2006,007, and 2008. To determine if there were specific character-

stics of the tutors who actively taught CCC frequently, wehose to look at the sample of tutors who had at least 60% ofheir students perceiving them to be actively teaching CCCrequently and looked at their tutoring experience, rank, spe-

igure 2. Students’ response to the statement, “This tutor activelyeaches culturally competent care,” either frequently, sometimes, orever. Compared with the baseline year of 2004, the proportion oftudents saying their tutor actively taught CCC “frequently” significantly

ncreased in 2007 and 2008 (P � .05), but was not significantly in-reased in 2006.

ialty affiliation, age, and sex in comparison with those tutors s

ith less than 60% frequency. The tutors’ evaluation scores forheir overall performance were correlated with their scores forctively teaching cultural issues. The chi-square test was used toetermine the correlation between tutors’ overall teaching rat-

ngs and their ratings of frequently teaching CCC.

ResultsCourse EvaluationIn the evaluations for the Gastrointestinal Pathophysi-

logy course between 2004 and 2008, the proportion of stu-ents reporting that “Issues of culture and ethnicity as theyffect topics in this course were addressed” changed signifi-antly. In 2004, 18% of students said issues of culture andthnicity were discussed “frequently.” This increased signifi-

igure 3. Individual tutor percentages for students’ perception that theutor was actively teaching CCC “frequently” in 2004 compared with006, 2007, and 2008. In 2007 and 2008 the proportion of tutors ratedy 80% or greater of their students as “frequently” teaching CCC was

ignificantly higher than in 2004 and 2006 (P � .05).c(

syiiqplcno

tc2tia8a2if

anc2r

dtgH2pier(s

Fss

T

A

S

P

S

NtG

282 SHIELDS ET AL CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY Vol. 7, No. 3

antly to 40% in 2006, 51% in 2007, and 65% in 2008 (P � .000)Figure 1).

In 2006 only, we analyzed the change in evaluations for thisame question for all the preclinical courses for the academicears 2003–2004 and 2005–2006. The majority (13 of 18) ofndividual first- and second-year courses did not change signif-cantly from 2004 to 2006 with regards to their ratings for thisuestion. Four courses, including the Gastrointestinal Patho-hysiology course, had statistically significant increases at a P

evel of confidence of .05 in the proportion of students sayingulturally competent care issues were discussed frequently (dataot shown). We have no information regarding the methods thether 3 courses used to improve their evaluations.

Tutor EvaluationIn 2006, the proportion of students who perceived

heir tutor as actively teaching CCC frequently increasedompared with 2004, but was not significantly different. In007 and 2008, the proportion of students who perceivedheir tutor as actively teaching CCC frequently significantlyncreased compared with 2004 (P � .05) (Figure 2). In 2007nd 2008, significantly more tutors compared with 2004 had0% or greater of his/her students perceiving the tutor to bectively teaching CCC frequently (P � .05) (Figure 3). In008 there were 8 tutors who had 100% of his/her students

n the tutorial perceive that they were actively teaching CCCrequently (Figure 3).

Tutor CharacteristicsThere were a total of 49 tutors from 2004, 2006, 2007,

nd 2008 who had 60% or more of their tutorial studentsoting that they were teaching CCC frequently (Table 1). Weompared their characteristics with the group of 41 tutors from004, 2006, 2007, and 2008 with less than 60% of their students

able 1. Characteristics of Tutors With Frequency Ratings of

2004 (n � 22)

�60%(n � 6,27%)

�60%(n � 16,

73%)

�

(n4

ge, y�35 5 (83%) 10 (63%) 8�35 1 (17%) 6 (38%) 2

exFemale 2 (33%) 6 (38%) 3Male 4 (66%) 10 (63%) 7

rior experienceYes 2 (33%) 6 (38%) 5No 4 (66%) 10 (63%) 5

pecialty and rankGI fellow 2 (33%) 6 (38%) 3GI faculty 1 (16%) 7 (44%) 4Medicine attendings and

residents2 (33%) 3 (19%) 3

Other 1 (16%) 0

OTE. Tutors from 2006–2008 as a group were significantly more likeaching CCC “frequently” compared with 2004 (P � .003).I, gastrointestinal.

ating them as actively teaching CCC frequently. No significant .

ifference in frequency of teaching CCC was noted with regardo age (�35 years vs �35 years), sex, prior experience as aastrointestinal tutor, academic rank, or primary specialty.owever, compared with 2004 tutors, the tutors in 2006 to

008 as a combined group were significantly more likely to beerceived by 60% or greater of their tutorial students as teach-

ng CCC frequently (P � .003). Tutors with excellent overallvaluation scores as teachers were significantly more likely to beated by their students as also actively teaching CCC frequentlyP � .005) compared with those tutors with less good overallcores as teachers (Figure 4).

igure 4. A tutor’s overall evaluation score as a teacher on a Likertcale (in which 1, the lowest score, is the best score), is correlatedignificantly with his/her “active” teaching of CCC “frequently” (P �

% or �60%

6 (n � 23) 2007 (n � 22) 2008 (n � 23)

,�60%

(n � 13,57%)

�60%(n � 16,

73%)

�60%(n � 6,27%)

�60%(n � 17,

74%)

�60%(n � 6,26%)

) 6 (46%) 11 (69%) 2 (33%) 7 (41%) 4 (67%)) 7 (54%) 5 (31%) 4 (67%) 10 (59%) 2 (33%)

) 3 (23%) 4 (25%) 1 (17%) 4 (24%) 3 (50%)) 10 (77%) 12 (75%) 5 (83%) 13 (76%) 3 (50%)

) 7 (54%) 6 (38%) 4 (67%) 12 (71%) 3 (50%)) 6 (46%) 10 (63%) 2 (33%) 5 (29%) 3 (50%)

) 2 (15%) 3 (19%) 1 (17%) 3 (17%) 3 (50%)) 6 (46%) 6 (37%) 1 (17%) 7 (41%) 2 (33%)) 3 (23%) 4 (25%) 1 (17%) 4 (24%) 1 (17%)

2 (15%) 3 (19%) 3 (50%) 3 (17%) 0

be perceived by 60% or greater of their tutorial students as actively

�60

200

60%� 103%)

(80%(20%

(30%(70%

(50%(50%

(30%(40%(30%

0

ely to

005).

itiopbrisoctmTptdcecca

iqat1sTtcot

2ttphioCir

awtettchaC

rc

dplb

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

March 2009 INTEGRATION OF CULTURAL AND ETHNIC FACTORS 283

DiscussionThis study shows that an innovative program consist-

ng of a 1-hour faculty development session, cases with CCCriggers, and weekly longitudinal reinforcement was successfuln significantly improving students’ perception of the frequencyf discussion of CCC in both the overall gastrointestinal patho-hysiology course, and by individual tutors. Our data suggest,ut do not prove, that it was the faculty development programather than the case changes that led to the significant increasen discussion of cross-cultural care. The faculty developmentession focused on helping tutors to understand the relevancef the racial, cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic triggers toourse specific gastrointestinal diseases, and encouraged tutorso take an active and pivotal role in generating questions they

ight use to stimulate students’ discussion of these factors.hus, the CCC discussion was interwoven with discussions ofathophysiologic concepts in a preclinical tutorial rather thanaught as a separate course or curriculum as others haveone.26 –28 Although there is no direct evidence to prove thatross-cultural care curricula improve the quality of care deliv-red to patients, the hope is that medical students will learn keyross-cultural attitudes, knowledge, and skills from the tutorialurriculum that ultimately will help to improve patient carend decrease physician biases.9

In the spring of 2004, only 18% of the second-year studentsn the Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology course checked “fre-uently” for the statement “Issues of culture and ethnicity wereddressed” on their course evaluation forms, putting the gas-rointestinal pathophysiology course in the lowest ranks of the8 preclinical courses for teaching CCC. In 2008, 65% of thetudents checked “frequently” for the same course statement.he tutors also improved with 74% of the students in all the

utorials noting that their tutor actively taught CCC frequentlyompared with 43% in 2004. We chose 2004 rather than 2005 asur baseline data because 2004 data were free of interventionso improve CCC discussion.

Our program may have succeeded for 2 reasons. First, in007 we used students to review our proposed modifications tohe 2006 case triggers. Second, to increase the enthusiasm ofhe tutors for trying to seamlessly weave in CCC with patho-hysiology, we put the emphasis on the following: (1) reviewingealth care disparities data and how they directly affect gastro-

ntestinal diseases; (2) encouraging the tutors to create theirwn questions for CCC discussion; (3) showing the relevance ofCC to gastrointestinal pathophysiology; and (4) weekly shar-

ng of tutor anecdotes regarding CCC discussion in their tuto-ial groups with an expert facilitator.

We found no impact of the tutor’s sex, age, prior experiences a gastrointestinal tutor, rank, or specialty in determininghether a tutor actively taught CCC frequently. Our data imply

hat all tutors, even first time tutors who are interested andnthusiastic, can learn to interweave cross-cultural factors intoutorials with focused training. The frequency of discussion ofhese topics did not detract from the tutors’ overall grade as aommunicator of pathophysiologic principles. Rather, it mayave helped because tutors with the highest ratings as teacherslso were significantly more likely to be perceived as teachingCC frequently.

In summary, an innovative faculty training program, that iseadily applicable and adaptable to other preclinical and clinical

ourses, was able to significantly increase the frequency of 2iscussion of racial, ethnic, and sociocultural factors in a patho-hysiology course. Ultimately, we hope these discussions may

ead to an improvement in physicians’ recognizing and avoidingias in their care of patients.29 –32

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new healthsystem for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National AcademyPress, 2001.

2. Department of Health and Human Services. National healthcaredisparities report, 2006. Rockville, MD: Agency for HealthcareResearch and Quality, 2006.

3. Clancy C. Improving care quality and reducing disparities. ArchIntern Med 2008;168:1135–1136.

4. Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, et al. Physician perfor-mance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med2008;168:1145–1151.

5. Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination and obesity. ObesityRes 2001;9:788–805.

6. Peyton S, Chaddick J, Gorsuch R. Willingness to treat alcoholics;a study of graduate social work students. J Stud Alcohol 1980;41:935–940.

7. Brawley OW, Jani AB. Disparities in cancer care. Curr Probl Cancer2007;31:114–122.

8. Kauh J, Brawley OW, Berger MZ. Racial disparities in colorectalcancer. Curr Probl Cancer 2007;31:123–133.

9. Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual ap-proaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med 2003;78:560–569.

0. Hobgood C, Sawning S, Bowen J, et al. Teaching culturally appro-priate care: a review of educational models and methods. AcadEmerg Med 2006;13:1288–1295.

1. Shields HM, Guss D, Somers SC, et al. A faculty developmentprogram to train tutors to be discussion leaders rather thanfacilitators. Acad Med 2007;82:486–492.

2. Lloyd SC, Harvey NR, Hebert JR, et al. Racial disparities in coloncancer. Cancer 2007;109(Suppl):378–385.

3. Morris AM, Wei Y, Birkmeyer NJO, et al. Racial disparities in latesurvival after rectal cancer surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:787–794.

4. Martinez SR, Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. Treatment disparities in His-panic rectal cancer patients: a SEER database study. Am Surg2006;72:906–908.

5. Sloane D, Chen H, Howell C. Racial disparity in primary hepato-cellular carcinoma: tumor stage at presentation, surgical treat-ment and survival. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:1934–1939.

6. Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, et al. Body-mass index andsymptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med2006;354:2340–2348.

7. Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity andthe risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complica-tions. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:199–211.

8. Cooper BT, Chapman W, Neumann CS, et al. Continuous treat-ment of Barrett’s oesophagus patients with proton pump inhibi-tors up to 13 years: observations on regression and cancerincidence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:727–733.

9. Lennard-Jones JE. Constipation. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS,Sleisenger MH, eds. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal andliver disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002:199–200.

0. Ahmed S, Gunaratnam NT. Melanosis coli. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1349.

1. Gardiner P, Graham R, Legedza ATR, et al. Factors associatedwith herbal therapy use by adults in the United States. Altern TherHealth Med 2007;13:22–28.

2. Menon KVN, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

R

Ds

A

cRMBh

C

tIp

284 SHIELDS ET AL CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY Vol. 7, No. 3

treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:1021–1029.

3. Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. In: SchiffER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, eds. Schiff’s diseases of the liver.9th ed. Volume 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins,2002:1033–1034.

4. Kesar L. Care across cultures. Proto Magazine of MassachusettsGeneral Hospital 2007;Winter:20–25.

5. Swartz MH. Caring for patients in a culturally diverse society. In:Swartz MH, ed. Textbook of physical diagnosis. 4th ed. Philadel-phia: WB Saunders, 2002:51–78.

6. Lum CK, Korenman SG. Cultural-sensitivity training in U.S. med-ical schools. Acad Med 1994;69:239–241.

7. Pena Dolhun E, Munoz C, Grumbach K. Cross-cultural educationin U.S. medical schools: development of an assessment tool.Acad Med 2006;78:615–622.

8. Flores G, Gee D, Kastner B. The teaching of cultural issues inU.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med 2000;75:451–455.

9. Ko M, Heslin KC, Edelstein RA, et al. The role of medical educa-tion in reducing health care disparities: the first ten years of theUCLA/Drew Medical Education Program. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:625–631.

0. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, et al. Cultural competenceand health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health

Affairs 2005;24:499–505. m1. Whitcomb ME. Preparing doctors for a multicultural world. AcadMed 2003;78:547–548.

2. Taylor JS. Confronting “culture” in medicine’s “culture of noculture.” Acad Med 2003;78:555–559.

eprint requestsAddress requests for reprints to: Helen M. Shields, MD, Beth Israel

eaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Massachu-etts 02215. e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (617) 667-5826.

cknowledgementsThe authors are grateful to Vinod Nambudiri for compiling and

oordinating the case reviews by Chitra Akileswaran, Edith Gurrola,achel Jimenez, Vinod Nambudiri, Amy Salzman, Peter A. Samuel,arie-Adele Sorel, Monica Soni, and Kara Wong. The authors thankrian Hyett, MD, Erin Kane, and Field Willingham, MD, MPH, for theirelp with faculty development.

onflicts of interestThe authors disclose the following: Dr Shields received support for

his project from the Leo E. Wolf and Natalie W. Wolf Fund at Bethsrael Deaconess Medical Center. Dr White received support for thisroject from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts. The re-

aining authors disclose no conflicts.