I Bequeath

Transcript of I Bequeath

IIBequeath…Bequeath…

FFROMROM GenerationGeneration TOTO GenerationGeneration

Domestic violence is a widespread crisis. In recorded history, it has been

found that domestic violence has been the most avoided and secret social

crisis.1 However, with the increased documentation of the prevalence of

domestic violence and the heightened awareness and education domestic violence

has become more accepted as a social problem rather than a family problem.

And although there are more and more men stepping forward as victims of

domestic violence at the hands of women, the tables are more often turned in

this patriarchal society where we are still searching for answers and

solutions.

Only recently has research been conducted regarding the prevalence of domestic

violence and its impact on the individuals and society. Prior to the

seventies, domestic violence was highly on a don’t ask, don’t tell policy. It

still carries with it multiple stigmas and misunderstandings, particularly for

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 1 of 25

male victims. And, in many ways, it remains a “domestic” issue, where law

enforcement is reluctant to become involved in family matters.

My name is Luka

I live on the second floor

I live upstairs from you

Yes I think you've seen me before

If you hear something late at night

Some kind of trouble. some kind of fight

Just don't ask me what it was

Just don't ask me what it was

Just don't ask me what it was

I think it's because I'm clumsy

I try not to talk too loud

Maybe it's because I'm crazy

I try not to act too proud

They only hit until you cry

And after that you don't ask why

You just don't argue anymore

You just don't argue anymore

You just don't argue anymore

Yes I think I'm okay

I walked into the door again

Well, if you ask that's what I'll say

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 2 of 25

And it's not your business anyway

I guess I'd like to be alone

With nothing broken, nothing thrown

Just don't ask me how I am

Just don't ask me how I am

Just don't ask me how I am19

As awareness of the problem grows, so does support of the fact that something

has to be done, socially and legally18, to change and intervene in the cycle

of the civil wars, which are fought in many homes every day.

Domestic violence has many contributing factors, both for the perpetrator and

the victim. There is an abundance of literature and studies done to discuss

the prevalence of domestic violence, the risk factors involved and proposed

interventions for successfully reducing familial violence. Amongst the

characteristics discussed are prototypes of the individual, the family of

origin, and distorted thinking patterns involved in justifying and defending

the abuse.

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 3 of 25

As is evidenced in much of the research, a high proportion of batterers were

victims themselves at one time, most often through experiencing child abuse or

witnessing parental domestic violence incidents.1,17 Coupled with substance

abuse (particularly early onset of substance abuse), these are two of the most

predominating risk factors for the existence of domestic violence.

Another strong predictor of domestic violence is the batterer’s need for power

and control17, despite the long utilized interventions focusing on anger

management. Although anger or stress may be a trigger, it is definitely not

the cause. The cause of domestic violence is better described as a method of

coping with the underlying belief system that violence is a cure-all,

especially where one person has the upper hand. Many men who abuse also

believe that they are superior, have the final word, and have the right to be

domineering in their inter-gender relationships.1,10 It is also supported by

research that those who become violent while intoxicated often use the alcohol

as a scapegoat for their behavior. However, it is also shown that those

incidents which occur while the batterer is intoxicated are often more severe

than those which occur during sobriety. A substance abuse counselor for the

courts stated that “’While [he couldn’t] say drinking is the cause of domestic

abuse, it definitely pours gasoline on the fire,” he said. “If we can get

them sober, we have a good chance of not seeing them again,” he said. “Most

of the time, if they are not drinking, they are not hitting their wives.” 3

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 4 of 25

6

Most batterers utilize the same techniques of control and share an underlying

belief system of relationships. For example, many batterers feel that by

threatening their partner or using physical violence they will produce

change.14 In addition, batterers often hold strong traditional gender role

stereotypes, are overly jealous, and expects his partner to be a “mind

reader”, often anticipating and always fulfilling his needs.14 In short, a

batterer expects his partner to be a puppet and him the master. She is not

to speak her mind or think for herself. In addition, they also have a

tendency to have other underlying psychological problems. “More than 50% of

batterers suffer from alcoholism, antisocial personality, or recurrent

depression.”8 Some believe that if the batterer perceived a sense of equality

in the relationship and between women and men as a whole, the violence would

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 5 of 25

sharply decrease or even cease, thus looking at socialization and

resocialization of men.12

Domestic violence, as does substance abuse, becomes a classic example of a co-

dependent relationship. The more traditional the batterer is in his idea of

gender roles and the more power he holds (or believes he should hold) in the

relationship, the higher the likelihood that domestic violence will occur. 1

The abuser is driven by an internal belief that his partner needs to be

controlled and submissive, wherein the controlling and violent behavior

follows close behind.1 This is often a result of the batterer witnessing

domestic violence as a child, experiencing child abuse (especially physical),

and attributing violence to resolution. 1 The proceeding violence becomes the

center of the relationship of which everything else revolves, both for the

abuser and the victim. 8 It becomes a predictable pattern of unpredictable

rage, ever increasing in its intensity. And as the cycle of violence

continues, so does the cycle of emotional co-dependence.8 The behavior

becomes accepted, and expected. An emotional resistance to the tolerance

builds, as does the body build a physical tolerance to substances. The victim

is then able to take more and more abuse, wherein the abuser needs to increase

the level of abuse to feel the same sense of control, power, and adrenaline. 8

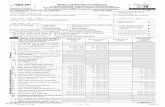

Table 1: Characteristics of Domestic Violence:

Parallels with DSM-IV Criteria for Substance-Related Disorders8

1. Loss of control: The abuser is contrite after the abuse,

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 6 of 25

promises not to do it again, yet inevitably the abuse recurs.

2. Continuation despite adverse consequences: The victim

experiences emotional, sexual, and physical damage and loss of

self-esteem; the abuser experiences remorse and guilt at times,

but the abuse continues.

3. Preoccupation or obsession: The abuser is preoccupied with

controlling the victim and (if sexual violence is involved)

with maintaining access to sexual gratification.

4. Development of tolerance: Initially a testing of violence; the

victim gets desensitized and tolerates increasing levels; the

violence escalates in frequency and/or intensity and/or

diversity.

Domestic violence and substance abuse share many of the same thinking

distortions, personality characteristics, and self-defense mechanisms.2

Domestic violence and addictive disorders do not merely coexist –

they actually share many features. These include loss of control,

continuation despite adverse consequences, preoccupation or

obsession, tolerance and withdrawal, involvement of the entire

family and, in fact, of multiple generations, and use of the

defenses of denial, minimization, and rationalization. In both

cases it is difficult for the partner to leave.8

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 7 of 25

Although some abusers may be seen as exhibiting poor impulse control2, this

would only be accurate if the abuser is unable to control his anger and

aggression in other social areas and contexts of his life (i.e. at work, a

restaurant) and against others other than his partner or children. By

confining his behavior, however, the batterer shows that he does have impulse

control in many situations, thus leading us to believe that his abuse is not

merely an issue of poor impulse control. Many functional alcoholics can

control the time and place they consume alcohol, just as many batterers are

able to control their rage and aggression in social situations but not when

they are in the privacy and “safety” of their own home. 10 In addition, both

addicts and batterers often try to convince loved ones that they are sorry,

they will change, and “it will never happen again”. Regardless of whether or

not the perpetrator is authentic in their promises, they rarely follow through

and have a quick rate of relapse. While studies agree that substance abuse

does not increase the instance of domestic violence in and of itself, there is

a clear link between the two.10

Another example of a common cause relates to the frequent co-

occurrence of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and early-

onset (i.e., type II) alcoholism. ASPD is a psychiatric disorder

characterized by a disregard for the rights of others, often

manifested as a violent or criminal lifestyle. Type II alcoholism

is characterized by high heritability from father to son; early

onset of alcoholism (often during adolescence); and antisocial,

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 8 of 25

sometimes violent, behavioral traits. Type II alcoholics and

persons with ASPD overlap in their tendency to violence and

excessive alcohol consumption and may share a genetic basis. 2

It was also surprising that many batterers increased their violence purely

with the belief that they had been drinking, indicating that the effect of

alcohol is a secondary effect to the physical act of drinking.4, 2 There is

also evidence to suggest that, although alcohol is not the cause of domestic

violence, those with more of a propensity or acceptance of violence may be

more willing to use that violence while intoxicated due to decreased

inhibitions and increased probability that the batterer will “interpret his

partner's behavior as arbitrary, aggressive, abandoning, or overwhelming.

Batterers may be more likely than non-batterers to misinterpret the actions of

their partners in this manner, and substances enhance the

misinterpretation.”17 There is also a strong belief that one is led to domestic

violence, and often substance abuse, from a high risk taking personality (i.e.

Type A Personality).2

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 9 of 25

…He Promised

Aside from promises made, promises are not kept. Domestic violence has high

morbidity rates for victims, especially when the batterer is under the

influence. 10 And although the high morbidity rates for partners of alcoholics

are not present, the family dynamics and abuser characteristics contain many

parallels. For example, both contain a high degree of denial. The abuser

believes that he can change his actions at any time, but repeats his

destructive behavior at the expense of his family. When substance abuse is

used as an “escape” from the troubles of home and family life, it is found

that the instance of domestic violence increases.9 Often times, the

consumption of alcohol is used as an excuse for intolerable behavior, trying

to remove the guilt and often times increasing the instance of abuse when the

subject just believes they have consumed alcohol.10, 17, 20

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 10 of 25

Table 2: Other Parallels Between Domestic Violence and Addictions8

Domestic violence and addictive disorders have the following common

features:

1. They adversely affect intimacy and sexuality.

2. They constitute family disorders, and adversely affect all

family members across generational lines.

3. They involve ritualization of behavior. The cycle of violence

and the cycle of addiction both include periods of escalation of

behavior, often followed by a time of contrition and promises to

change and give up the behavior, followed by a time of

increasing tension and then a return to behavioral acting out.

4. They involve the use and abuse of power for personal gain and

gratification. There is ego expansion and relief of tension when

using substances and with the exertion of or threat of violence.

5. They initially tend to be restricted to the home environment,

but in late disease stages may involve behavior expressed in the

workplace.

6. They result in shame, guilt, decreased self-esteem, and

emotional numbness.

7. They are characterized by denial, minimization, and

rationalization.

8. Domestic partners and family members have great difficulty

intervening with or abandoning the affected individual.

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 11 of 25

Many abusers also justify their behavior, stating that they are entitled to

drink after a long day at work, or they are warranted in hitting their partner

due to her disobliging and obstinate actions. Many of these beliefs

contributing to domestic violence are often linked to rigid, traditional,

gender stereotypes and the notion of male dominance and authority. Another

theory is that alcohol triggers chemicals in the brain that are also

associated with higher rates of aggression, such as serotonin and

testosterone.2 Additionally, the level of marital satisfaction and financial

stress have also found to be indicators of abuse.9, 17

There are additional other theories of why men batter and, in effect, how to

begin to intervene and break the often generational cycle of violence. For

example, Prince and Arias13 state that the batterers perceived locus of

control could be a significant contributor to the physical and emotional

violence bestowed. For example, they state that when a man perceives himself

as having a low external locus of control, he is more likely to batter than a

man who perceives himself as having a high external locus of control. Prince

and Arias also examine the role of a perceived low internal locus of control

on the reason why a man will batter his partner1:

Low Internal Locus of Control

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 12 of 25

Low Self

Esteem

Violence used in response to

frustration

High Self

Esteem

Violence used to gain a sense of

control

It was found that low self-esteem not only affected the perceived locus of

control, but also increased the instances of stress within the relationship,

alcoholism, as well as a higher approval of domestic violence. 1

One explanation for this phenomenon may be that men who feel

powerless because of low self-esteem, or who feel little control

over others, or life events have a high need for power…. Another

hypothesized that men who view intimacy with women as dangerous,

threatening and uncontrollable can become highly anxious and

angry. The research suggest that these feelings of psychological

discomfort may then lead to behaviors such as violence against the

partner to control women and to reduce men's anxiety and anger.1

This variance in motivation and justifications used for battering and the

subordinate and co-dependent effect it often has on women makes it very

difficult to not only design but implement an effective intervention. And, as

is true with many addicts, those who batter will have a high rate of

recidivism unless they identify their behavior as a problem and are

intrinsically motivated to change.

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 13 of 25

The question remains, then, how do we change an abuser’s external motivation

for change (e.g. avoiding prison) to an internal motivation (e.g. not wanting

to hurt or dominate their partner)? For it has been identified in research

that those men who are internally motivated to change their behavior have a

lower attrition rate and a higher rate of success when entering batterer

intervention programs, as long as it is not being used as another control

tactic against their partner. 1

Not only is the batterer’s source of motivation important, so is the

intervention method used. One of the first programs utilized to address the

underlying issues of the abuser to help curtail further episodes was AMEND

(Abusive Men Exploring New Directions). Although this program was innovative

and helped break new ground in the field of domestic violence, its success was

very limited. The recidivism rates for domestic violence, with or without the

presence of substance abuse, is very discouraging.15 The nature of this

program was far removed from the actual incident for which the perpetrator was

convicted. This, according to the author, was the program’s downfall. They

state that this type of program must be initiated with the perpetrator no more

than twenty-four hours following the domestic violence, providing little

opportunity for the partner to recant or step back from any legal action. In

addition, it is stated that the program must be centered on the needs of the

perpetrator, including:

1. “the need to learn about rational and irrational beliefs;

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 14 of 25

2. the need to learn anger control techniques;

3. the need to develop communication skills;

4. the need to learn stress management skills;

5. the need to participate in a support group utilizing shared

experiences and peer support to help in overcoming violent

behavior.”15

Clearly, this program will not work for everyone, even if it is initiated with

in the first twenty-four hours. It does not address the strong denial of the

batterer, as they may not even believe that they have a problem, justifying

away their violent behavior. Additionally, many believe that domestic

violence is not an issue of anger at all5, and solely an issue of power and

control. Another program has a very similar framework, providing an outline

to follow in order of occurrence:

1. Instruct and support the alcoholic-batterer in abstaining from

alcohol use and violence through direct appeal, and through

appropriate treatment modalities (or through legal or formal

sanctions such as restraining orders, job jeopardy, etc.)

2. Confront denial and projection of responsibility.

3. Incorporate recovery programs for addiction concomitant with

anger management and self-control techniques.

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 15 of 25

4. Address relapse issues common to both problems, such as

resentment, self-pity, and self-defeating patterns of behavior.

5. Teach assertive communication skills.

6. Educate all parties on the techniques of effective problem

solving, thereby empowering each individual in the system to

behave in his or her personal best interest.

7. Address the needs of the family system. These are inter-

generational problems, and prevention is a primary objective.5

A batterer’s personality has been found to be very instrumental in the type of

intervention used. In an attempt to understand the cycle of violence and

internal drive which leads to domestic violence, many researchers and

theorists have looked at the underlying personality factors of the batterer

and place them into broad categories for treatment. For example, some look at

batterers as being one of the following types:

reactive (violence is isolated to the family and the batterer is

remorseful, basing his violent tendencies on poor impulse control and

anger management)

instrumental (may exhibit borderline tendencies, is the most dangerous

type who is co-dependent and jealous with a need for power and control

in the relationship in line with his view of women and traditional

gender stereotypes)

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 16 of 25

antisocial (very manipulative and selfish, exhibits other violent or

criminal behavior, highest tendency of substance abuse, and uses his

partner purely as a means to an end). 7, 12

Intervention methods need to be carefully constructed for the type of batterer

that is being treated. There are multiple studies that show that batterers

show many different characteristics, despite the striking commonalities. For

example, depending up the severity and venue for which the violence takes

place, the perpetrator may have differing underlying psychological problems or

motivations for the abuse. And, instead of focusing primarily on

aggressiveness and anger management, many programs are beginning to shift by

placing equal weight on changing the perpetrator’s distorted thinking patterns

and self esteem. Psychodynamic therapy, therefore, has been found to work well

for dependent men18 whereas cognitive behavioral therapy appears to be more

effective with those men who exhibit antisocial, narcissistic, or avoidant

personality traits, which seems to compromise most of the identified

batterers.12, 21 In addition, there is a strong focus on the abuser’s own family

of origin, often which itself was abusive, providing the abuser with the

belief that violence is just and is appropriately used to resolve

conflicts.1,17 Thus, family systems states that by providing a stronger family

unit in conjunction with couples counseling could well be the answer.12

However, this would be difficult as research suggests that a batterer is not

ready for couples counseling until an individual intervention is successfully

completed and he exhibits the new, learned (and violence free) behavior for at

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 17 of 25

least six months or a year.1 Taking this into consideration one could employ

a similar, but alternative model of intervention is utilized. In the FRAMES

model, the batterer is given more control over his own program and treatment

while still providing a consistent model to be followed.

Feedback: Provide feedback to increase awareness of his/her

situation and the ways in which it is harmful.

Responsibility: Emphasize that it is the individuals own decision

to change.

Advice: Provide advice to identify the problems and discuss the

necessity for change.

Menu: Provide a choice of strategies for change.

Empathy: Express acceptance and understanding of the person.

Self–Efficacy: Instill client's perception that he or she can

implement a changed strategy.16

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 18 of 25

As is true with children, groups, and communities, the more the recipient of

the program is included in the decision making process, the more invested they

will be in the program itself. By offering them a choice of strategies, they

are able to choose the one they are most comfortable with, admitting that they

have a problem and that they believe that some intervention strategy will help

reduce their violence. It places additional responsibility on the abuser by

stating that now that they are aware that their behavior is unacceptable and

there are alternative ways to act and react, thus making it their decision and

ultimate responsibility towards recovery. As is true in addiction, no one can

make them change. Batterers must change their belief system that justifies the

violence they commit in their relationships.5 In addition, the FRAMES model

emphasizes the need to go where the client is, both by providing a choice of

intervention methods and empathy.

In addition, the criminal justice system needs to become more intimately

involved with domestic violence. Police who repeatedly answered domestic

violence calls and later pressed charges, along with court mandated treatment,

led to the most significant decrease in continued violence. Victims self

reports show that if there is a 50% decrease of recurring violence in the six

months following a case settlement. Police can step up and take their part in

lowering incidents of domestic violence as well. When police coordinated

their efforts with other programs and criminal justice intervention, there was

a marked decrease in recidivism.18

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 19 of 25

6

The loss of control and effects of alcohol and drug abuse

contribute significantly to the severity of beatings in abusive

relationships. FBI statistics indicate that thirty percent of

female homicide victims are killed by their husbands or

boyfriends. Battering, unlike the disease of addiction, is a

socially learned behavior which can be reversed if the motivation

for change is realized. Techniques to control one's behavior and

social skills can be relearned to eliminate the violent behavior,

just as life manageability can be attained through a commitment to

recovery. Just as abstinence from a drug is alone insufficient for

true recovery, elimination of violent behavior is just the first

of many steps toward breaking the cycle of domestic violence.11

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 20 of 25

By understanding contributing factors to domestic violence and providing

appropriate intervention methods based upon underlying personality and

psychological factors, we can take the next step in domestic violence

intervention and prevention.

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 21 of 25

1. Albee, Reid D. Batterer’s Intervention Programs, Why Are They Needed, Are

They Effective? An Overview Of The Causes of Intimate Partner Violence

and Overview of Batterer Intervention Programs and Standards. Retrieved

November 6, 2002, from

http://www.umm.maine.edu/BEX/students/ReidAlbee/rabatterysyn.html

2. Alcohol Alert. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism No. 38 October 1997.

Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa38.htm

3. Associated Press. Substance Abuse not Key in Most Domestic Violence.

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 337-344. Haight-

Ashbury Publications, San Francisco, California. Retrieved November 6,

2002, from http://www.s-t.com/daily/07-97/07-22-97/a03sr024.htm

4. Bennett, Larry W. Ph.D Substance Abuse and Woman Abuse by Male Partners.

Applied Research Forum: National Electronic Network on Violence Against

Women. February 1998. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.vaw.umn.edu/finaldocuments/Vawnet/substanc.pdf

5. Family Crisis Center. Adult Violence Intervention Program (Avip)

Frequently Asked Questions (Faq). Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.family-crisis-center.org/avipfaq.html

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 22 of 25

6. Family Crisis Center. Equality Versus Power and Control. Retrieved

November 6, 2002, from

http://www.family-crisis-center.org/equality_power.html

7. Governor's Office Of Child Abuse And Domestic Violence Services. The

Profile of Domestic Violence Offenders. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://gov.state.ky.us/domviol/profile.htm

8. Irons, Richard R. MD, FASAM and Schneider, Jennifer P. MD, Ph.D. When

Domestic Violence is a Hidden Face of Addiction. Journal of Psychoactive

Drugs, Vol 29, pages 337-344, 1997. Haight-Ashbury Publications, San

Francisco, California. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.jenniferschneider.com/articles/domestic.html

9. Kenny, Maureen Ph.D. Domestic Violence: Abuse in Families. Retrieved

November 6, 2002, from

http://www.texaspsyc.org/associations/246/files/Abuse_in_Families.doc

10. Lillak, Dale Kay M.S. Alcohol, Drugs and Domestic Violence: What’s The

Connection? Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.modernlife.org/all_staples1999to2000/1999Months/Octoberissue/

AlcoholDomesticViolenceConnection.htm

11. Mackey, Robert Ph.D., C.A.C., DVS. Facts On: Alcohol, Drugs and Domestic

Violence. Center of Alcohol Studies. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.dui.com/oldwhatsnew/Rutgers/domestic.html

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 23 of 25

12. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Male Batterers.

Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/malebat.htm

13. Kaufman Kantor, Glenda and Jasinski, Jana L. Dynamics of Partner

Violence and Types of Abuse and Abusers. Family Research Laboratory,

University of New Hampshire. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.nnfr.org/research/pv/pv_ch1.htm.

14. The Problem: Predictors of Domestic Violence. Retrieved November 6,

2002, from http://www.ncadv.org/problem/predictors.htm.

15. Roberts, A.R. (1984) "Intervention with the Abusive Partner" in ROBERTS,

A.R. (ed.) Battered Women and their Families: Intervention Strategies

and Treatment Programs Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1984. pp.

84-115. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.wise.infoxchange.net.au/DVIM/DVMen-robertsar.htm

16. Stewart, Lynn and Cripps Picheca, Janice. Improving Offender

Motivation for Programming. Living Skills and Family Violence

Prevention Programs Correctional Service of Canada. Retrieved

November 6, 2002, from

http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/pblct/forum/v13n1/v13n1a6e.pdf

17. Substance Abuse and Woman Abuse by Male Partners. Retrieved November 6,

2002, from http://www.enter.net/~wrmc/sawa.html

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 24 of 25

18. Tolman, Richard M. and Edleson, Jeffery L. Intervention for Men Who

Batter: A Review of Research. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.umm.maine.edu/BEX/students/ReidAlbee/rabatterysyn.html

19. Vega, Suzanne. Luka. Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.vega.net/solitude.htm#luka.

20. von der Pahlen, Bettina The Role Of Alcohol And Steroid Hormones In

Human Aggression. Department of Mental Health and Alcohol Research

National Public Health Institute Helsinki and Finland and Department of

Psychology Åbo Akademi University Åbo, Finland. Retrieved November 6,

2002, from http://www.ktl.fi/publications/2002/A15.pdf

21. White, Robert and Gondolf, Edward. Implications of Personality Profiles

for Batterer Treatment: Support for the Gender-Based, Cognitive-

Behavioral Approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15 (2000), pp. 467-488.

Retrieved November 6, 2002, from

http://www.iup.edu/maati/Publications/BattererCharacteristicsAbstracts.s

htm

Nicole De Smet, LISW I Bequeath: From Generation to Generation Page 25 of 25