Francesco Medici, "Speak to us of Beauty. On 'Twenty Drawings' by Kahlil Gibran", «FMR», 26...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Francesco Medici, "Speak to us of Beauty. On 'Twenty Drawings' by Kahlil Gibran", «FMR», 26...

Parlaci della bellezzaM

AN

UZIA

NA

Testo di Francesco Medici

Speak to Us of BeautyM

AN

UZIA

NA

Text by Francesco Medici

“il William Blake del XX secolo”.Nel 1908 Gibran riuscì persinoad aggiudicarsi la medaglia d’argentoal Salon du Printemps.Fin dall’infanzia, da quando restòfolgorato dalle intuizioni di Leonardoe di Michelangelo (aveva senz’altroben presenti i Prigioni quando eseguìla sua Donna con veste), lavorò senzasosta con matita, tavolozza e colorirealizzando centinaia di disegnie dipinti, tanto che il suo ultimodesiderio prima di morire fu chequalcuno si occupasse di raccoglierlitutti insieme ed esporli, affinché lagente potesse ammirarli e “forseamarli”. Oggi le sue tele sono esibitenelle maggiori gallerie e musei delmondo, incluso il Metropolitan diNew York, e le mostre dei suoi lavorisi succedono sempre più numerose inAmerica, Medio Oriente ed Europa.Ma Gibran, prima ancora che artistadella penna e del pennello, fu unmistico. Ecco perché gli strumentidella critica, letteraria o d’arte,si sono spesso rivelati inadeguatia interpretare il suo genio creativo.Inoltre gli studiosi si sono soloraramente preoccupati di indagareil suo operato figurativo,considerandolo espressionesubordinata o minore rispetto allasua poesia. Eppure la sua pittura siarmonizza così profondamente conla sua scrittura – il suo pensieropoetante – da rendere impossibileconcepire l’una senza l’altra.Vicino all’Isla-m e alle grandi religionid’Oriente, Gibran crebbe in unafamiglia di fede maronita (cioècristiana di rito orientale) per poisviluppare un credo sincretico, deltutto personale e originale, da moltidefinito “gibranismo”. L’arte e lapoesia non furono mai per lui un

102

Su Venti disegni di Kahlil GibranFrancesco Medici

“Speak to us of Beauty” è la sempliceesortazione con cui un anonimopoeta si rivolge ad al-Mus

¨tafà,

personaggio centrale del celeberrimo“poème en prose” di Kahlil GibranThe Prophet.Che cos’è la bellezza? Si raccontache una volta qualcuno lo abbiachiesto al grande poeta indianoRabindranath Tagore e che questiabbia risposto: “Ne sono da sempreavvinto e posseduto. Ho tentatomolte volte di comunicare attraversole parole cosa sia la bellezza, maho sempre fallito. La bellezzaè un’esperienza impossibileda esprimere.”Quando nel 1919 a New Yorkcomparve nelle librerie TwentyDrawings, il pubblico degliaffezionati lettori di Gibran ne fudisorientato e la critica espresse solopochi e tiepidi commenti. Sebbenele sue opere letterarie in edizioneoriginale fossero infatti tuttecorredate da splendide illustrazioni,si trattava del primo volumepubblicato in vita dall’autore– e sarebbe stato anche l’ultimonel suo genere – che contenevaesclusivamente una selezionedei suoi dipinti.Ancora oggi pochi sanno che Gubra-nH–alı-l Gubra-n (1883-1931) – questoil suo nome arabo completo dipatronimico –, libanese di nascita estatunitense di adozione, oltre chepoeta fu un pittore di straordinariotalento. Studiò all’Académie desBeaux-Arts di Parigi e fu allievo dialcuni dei maggiori artisti dell’iniziodel secolo scorso, tra cui AugusteRodin, che sembra lo abbia definito

ı-

MA

NUZ

IAN

ASu

Ven

ti d

iseg

ni

di K

ahlil

Gib

ran century”. In 1908, Gibran was

even awarded the silver medal atthe Salon du Printemps. From earlychildhood, when he was dazzledby the intuitions of Leonardo andMichelangelo (he must have beenaware of the Tuscan’s Slaves whenhe painted Woman with Garment),the artist used pencil, palette andcolour to endlessly produce hundredsof drawings and paintings, to theextent that his last wish before dyingwas that someone see to gatheringand displaying all of his work,so that people could admire and“perhaps love” it. His canvasesare currently exhibited in someof the most important galleriesand museums the world over,including the Metropolitan in NewYork, and exhibitions of his workare regularly held in America,the Middle East and Europe.But before being an artist of the penand of the paintbrush, Gibran wasa mystic, and it is for this reasonthat the instruments used by thecritics, whether literary or of the arts,have often proved to be inadequatein approaching his creative genius.Furthermore, scholars have onlyrarely been concerned with thestudy of his figurative production,considering it to be a subordinateor minor form of expression ascompared to his poetry. And yet,his painting so deeply harmonizeswith his writing – his poetizedthought – that it is impossible toconceive of one without the other.Close to Islam and to Easternreligions, Gibran grew up in a familyof Maronite faith (that is, Christianof Eastern rite), but would laterdevelop a syncretic credo that wasentirely personal and original, and

102

On Twenty Drawingsby Kahlil GibranFrancesco Medici

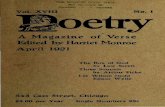

“Speak to us of Beauty” is the simpleexhortation used by an anonymouspoet to address Almustafa, the maincharacter in the celebrated poèmeen prose by Kahlil Gibran titled TheProphet. What is beauty? It is saidthat at one time the great Indian poetRabindranath Tagore was asked thesame question, and that the words heused to answer it were: “I have alwaysbeen charmed and possessed by it.I have ofttimes attempted to usewords to communicate what beautyis, yet I have always failed. Beautyis an experience that cannot beexpressed.”When, in 1919, Twenty Drawingsappeared in bookshops in New York,Gibran’s devoted readers weredisoriented by it, and the critics’comments were lukewarm. Althoughthe original editions of his literaryworks were all embellished bysplendid illustrations, this was thefirst volume published during thelife of the author – it would also bethe last of its kind – to exclusivelycontain a selection of his paintings.Still today, there are very few whoknow that Gibran Khalil Gubran(1883-1931) – the Arabic namecomplete with patronymic of theartist, born in Lebanon but Americanby adoption – in addition to being agreat poet, was also an extraordinarilytalented painter. He studied at theAcadémie des Beaux-Arts in Paris,and trained with some of the majorartists of the beginning of the lastcentury, including Auguste Rodin,who it is said defined him “theWilliam Blake of the twentieth

All the drawings reproduced inthese pages are by Kahlil Gibran,and are now in the GibranMuseum at Bisharri, in Lebanon.These drawings were broughttogether and published in KahlilGibran, Twenty Drawings, Knopf,New York 1919.

Pages 101 and 111Crucified, 1918.Detail and whole.

Page 103Mother and Child, 1919.

Pages 104-105Flight, 1916.

Page 106The Blind, 1915.

MA

NUZ

IAN

AO

nT

wen

ty D

raw

ings

by K

ahlil

Gib

ran

107

1919), con il saggio introduttivodi Alice Raphael già comparso sullaprestigiosa rivista americana “TheSeven Arts” nel 1917, dimenticatoda quasi un secolo, rivede oggi laluce in Italia (Venti disegni,Giuseppe Laterza, Bari 2006).È una raccolta di acquarelli cherappresentano la forma umana inquanto immagine e personificazionedella Bellezza, icona della Vita,emanazione dell’Eterno. Gli sfondiappaiono indistinti, oppure popolatida vaghe figure appena schizzate,ectoplasmatiche, come barlumi disogni.Le creature gibraniane – persinonelle opere che tentano una possanzascultorea – sono senza peso, senzamuscolatura, quasi volatili, calatein una dimensione atemporale,oltremondana, iperuranica,perché appartengono all’inconsciodell’autore. O, meglio, all’inconsciocollettivo, al “nostro comune mondodi visione”, perché tutti “siamo figlidelle forme e dei colori”. Lo Spiritosi esprime e si comunica nella visioneinteriore della vita umana, fatta diluce e di contorni estetici. Talvoltala matita si unisce al pennello perrifinire e far risaltare il soggetto,perché la gradazione di colore èestremamente delicata (raramentecompaiono tonalità più vivaci dirosso e di blu), tanto che all’iniziosembra che il colore utilizzato siaminimo, ma poi ci si accorge che ètutto colore, soltanto diffuso in modoimpercettibile, eppure sufficientea modellare le forme.Gibran fu definito un “visionario”,ma non si riteneva tale o, almeno,non più di quanto potesse esserlochiunque altro: “Per avere unavisione basta aprire gli occhi.”

esercizio intellettuale ma spirituale,un mezzo per elevare l’uomo allaconoscenza del divino. In Gibran lastessa ispirazione artistico-poeticadiviene rivelazione, epifania di Dio,“un passo dalla natura versol’infinito”, un ponte dalla materiaallo spirito. L’arte pittorica ècontemplazione della bellezzaumana, manifestazione dellaperfezione sensibile, colta nella suanudità – il nudo è praticamente ilsolo soggetto pittorico gibraniano –,prova della realtà immanentedel Creatore presente nelle suecreature.La bellezza, come si leggenell’eponimo sermone di The Prophet,deve essere “sentiero e guida”nell’esistenza di ciascuno. Coincide,anzi, con la vita stessa, perché “doveè la bellezza, lì sono tutte le cose”.Essa è pertanto arbitro ed essenzadell’arte gibraniana, un’arte che sifa esperienza mistico-estetica, viad’accesso alle verità primigenie eassolute, ineffabili ed escatologiche,dell’uomo. Gibran crea ispirato daun profondo amore e riconoscimentodel bello che gli consente di esprimereil suo messaggio universale rivoltoa tutta l’umanità. La traslucidapurezza dei suoi dipinti conduceal luogo più sacro, il cuore stessodell’essere umano, perché “ogniquadro è un ritratto, un autoritratto”.L’artista Kahlil Gibran si situa cosìal crocevia tra Oriente e Occidente,senza appartenere necessariamenteall’uno o all’altro, tra simbolistie visionari, tra classici e romantici,ed è proprio nella fusione di questetendenze opposte, nella conciliazionedei contrari, che egli arrivaa superare scuole, fedi e tradizioni.Twenty Drawings (Knopf, New York,

107

in the reconciliation of opposites,that he comes to surpass schools,faiths and traditions.Twenty Drawings (Knopf, NewYork 1919) with its prefatory essayby Alice Raphael and previouslypublished in the prestigious Americanjournal The Seven Arts in 1917,forgotten for nearly a century,presently and once again sees thelight in Italy (Giuseppe Laterza,Bari 2006). It is a collectionof watercolours that representthe human form as image andpersonification of Beauty, iconof Life, emanation of the eternal.The backgrounds appear to beindistinct, or populated by vaguefigures that are merely sketched,ectoplasmic, like the glimmer ofdreams.Gibranian creatures – even thoseportrayed in works that attemptto obtain a sculptural vigour – areweightless, they have no musculature,and are nearly volatile, deliveredinto a dimension that is atemporal,other-worldly, beyond the heavens,because they belong to the author’sunconscious. Or, better yet, to thecollective unconscious, to “our worldof vision”, because “we are creaturesof form and color”. The Spirit isexpressed and communicated in theinner vision of human life, madeof light and aesthetic contours. Thepencil, at times, joins the paintbrushin order to perfect and emphasize asubject, the gradation of the colourbeing extremely delicate (livelier redand blue hues are rarely seen); itappears, at first, that only a minimalamount of colour has been used,but we gradually realize that whatwe are looking at is really all colour,diffused imperceptibly, yet sufficient

by many defined “Gibranism”. Artand poetry for Gibran were neveran intellectual exercise, rather, theywere a spiritual one, a means ofelevating man to a knowledge ofthe divine. In Gibran, artistic-poeticinspiration becomes revelation,epiphany of God: “Art is a step fromnature towards the Infinite”, it isa bridge between matter and spirit.Pictorial art is the contemplationof human beauty, the manifestationof sensitive perfection, perceivedin its nakedness – the nude beingpractically the only subject inGibran’s painting –, proof of theimmanent reality of the Creatorpresent in his creatures.Beauty, as may be read in theeponymic sermon of The Prophet,must be “way and guide” in theexistence of each one of us. Betterstill, it coincides with life itself –because “where beauty is, thereare all things”. It is, thus, the arbiterand the essence of Gibranian art, anart that becomes mystical-aestheticexperience, pathway to the originaland absolute, ineffable andeschatological truths of man. WhenGibran creates, he is inspired bydeep love for and acknowledgementof beauty, and this allows him toexpress his universal message to allof humanity. The translucent purityof his paintings leads towards amore sacred place, the heart itselfof the human being, because “everypicture is a portrait, a self-picture”.The artist Kahlil Gibran stands atthe crossroads between East andWest, without necessarily belongingto either one, between symbolists andvisionaries, between classicists andromantics, and it is precisely in thefusion of these opposing tendencies,

AboveCentaur and Child, 1916.

Page 108The Rock, 1916.

Page 109The Triangle, 1918.

appare coperto da un velo. È ancorala bellezza a rappresentare il beneassoluto, Dio che si cela nell’intimodell’uomo, la nostra comune realtàoriginaria: “la bellezza è la vita,quando la vita svela il suo voltosacro.” Ricercare la bellezza significaallora tendere a Dio perché essarappresenta l’immagine divinanel mondo, ma nella sua tensioneascetica l’uomo è ostacolato dallasua parte terrena e temporale:“C’è qualcosa di grande in me chenon riesco a far uscire. È un io piùgrande, silenzioso, che siede e guardaun io più piccolo agitarsi in azionidi ogni genere. Tutto ciò che facciomi sembra falso, non corrispondea ciò che voglio esprimere. Sonocostantemente consapevole di unanascita che deve avvenire. È come seda anni un bambino volesse venirealla luce e non potesse. Continuaattesa, continuo travaglio e nessunparto.” È la bellezza il medium, “lavia che conduce all’io ucciso dall’io”,al nostro essere più profondo. Solofiltrando l’esistenza umana attraversol’icona della bellezza si riesce acoglierne l’essenza divina.Il motivo della lotta o dell’incontrodell’uomo con la sua natura bruta èrappresentato da Gibran nella seriedei centauri, soggetto di chiaraascendenza michelangiolesca erodiniana. L’individuo è raffiguratonella sua duplice natura: pur legatoindissolubilmente all’esistenzaterrena (gli zoccoli sono ben piantatial suolo), il busto umano dellacreatura favolosa si inarca e lebraccia si protendono verso il cielonel tentativo di elevarsi dalla suacondizione bestiale. È il drammadell’anima, i cui slanci rimangonospesso miseramente frustrati dalla

110

La pratica visionaria comincia infattidal reale, dal visibile conosciuto,per giungere all’invisibile ignoto.Per antitesi, nella sua produzioneletteraria e pittorica, il tema dellacecità ricorre di frequente ed èadoperato in senso ambivalente.Vi è chi, lontano dalla luce spirituale,vive all’oscuro di ogni consapevolezza(blind-hearted) e chi, al contrario,ha sviluppato una percezione e unrapporto diretto con il divino e con lesue manifestazioni senza farsi sviareda ma-ya-, dall’illusione del mondofenomenico. Nel Corano è Dio stesso,descritto come “la luce dei cieli edella terra”, a invitare gli uomini ad“abbassare i loro sguardi” (24, 30),a distogliere i loro occhi spiritualidall’inganno consueto e dalle falsitàdelle cose sensibili. È il motivodel fosco ritratto dell’uomo con ilcopricapo, Il cieco. Illuminati sonocoloro che riescono a scorgere lasfera interiore del proprio essere,l’“Io più grande”, cioè Dio nell’uomo,secondo la concezione fondamentaledei s.u-fı- (i mistici islamici).Essi possono allora chiudere gliocchi a ogni cosa imperfetta incontemplazione di Dio che è estraneoa ogni imperfezione: la vera bellezzaè “un’immagine che si vede anchecon gli occhi chiusi”.Anche Madre e figlio è unarappresentazione del principio suficodell’“Io più grande”. La natura piùpiccola dell’uomo è sorretta daquella più grande (dalle sembianzematerne, perché Gibran nutrivaun’idea femminile del divino).L’“Io più grande”, Dio, è vicinissimo– “vicino all’uomo più della suastessa vena giugulare” (Cor. 50, 16)– ma questi, pur anelando a Lui, nonlo vede, perché il volto del divino gli

MA

NUZ

IAN

ASu

Ven

ti d

iseg

ni

di K

ahlil

Gib

ran Self”. The smaller nature of man

is upheld by the greater one (whosesemblance is maternal, because forGibran the notion of the divine wasa feminine one). The “Greater Self”,God, is very close – “closer to manthan the jugular vein itself” (Kor. 50,16) – but although he desires Him,he does not see Him, because theface of this divine being appearsbefore him covered with a veil.It is again beauty that representsabsolute good, God hidden in theintimacy of man, our commonoriginal reality: “beauty is lifewhen life unveils her holy face.”The search for beauty thus meansinclining to God because it representsthe divine image in the world; butthe ascetic tension in man is heldback by that part of him that isworldly and temporal: “There’ssomething big in me and I can’t getit out. It’s a silent greater self, sittingand watching a smaller me do allsorts of things. All the things I doseem false to me; they are not whatI want to say. I am always consciousof a birth that is to be. It’s justas if for years a child wanted to beborn and couldn’t be born. You arealways waiting, and you are alwaysin birth pain. Yet there is no birth.”Beauty is the medium, the “paththat leads to self self-slain”, to ourdeepest being. Only by filteringhuman existence through the iconof beauty are we able to perceivedivine essence.The motif of man’s struggle orhis encounter with brute nature isrepresented by Gibran in his seriesof centaurs, a subject clearly derivedfrom Michelangelo and Rodin. Theindividual is portrayed in his dualnature: although indissolubly bound

110

to provide shape to the forms.Gibran was defined a “visionary”,but he did not consider himselfto be one, at least, no more thananyone else: “To see the vision is butto open our eyes.” The practice ofthe visionary, in fact, initiates fromwhat is real, from the known visible,in order to attain the unknowninvisible. By antithesis, the themeof blindness frequently recurs inthe artist’s literary and pictorialproduction, and it is used in anambivalent sense. There are thosewho, far from the spiritual light,live unknowing of any awareness(“blind-hearted”), and those who,instead, have developed a perceptionof and a direct relationship with thedivine and its manifestations withoutbeing distracted by maya, by theillusion of the phenomenal world.In the Koran it is God himself,described as “light of the heavensand the earth”, who invites mento “lower their eyes” (24, 30), touse their spiritual eyes to look awayfrom habitual deception and fromthe falseness of things of the senses.This is the motif in the dark portraitof a man who wears something overhis head titled The Blind. Those whoare able to perceive the inner sphereof their being, the “Greater Self”– that is, God in man, based on thefundamental conception of the Sufi(Islamic mystics) – are illuminated.They may then close their eyesto each and every imperfect thingin contemplation of God, whois extraneous to each and everyimperfection: true beauty is“an image you see though youclose your eyes”.Mother and Child is also a portrayalof the Sufic principle of the “Greater

MA

NUZ

IAN

AO

nT

wen

ty D

raw

ings

by K

ahlil

Gib

ran

113

insieme che assumono le formesuggerite nei titoli: “Voglio chequesta mostra altro non sia cheun’espressione della relazione tra laforma umana e tutte le altre – alberi,rocce –, che rappresenti insomma lostretto legame tra le varie forme divita.” Inoltre per Gibran è necessarioche la gente reimpari “la castità delnudo” perché il corpo, che racchiudein sé bellezza e libertà, è il simbolopiù vero e più nobile della vita stessa:“Spesso disegno corpi nudi perchéla vita è nuda. Se disegno unamontagna come un insieme di formeumane o dipingo una cascata comecorpi umani che precipitano, èperché vedo nella montagna uninsieme di cose viventi e nella cascatauna precipitosa corrente di vita.”Anche la pietra è parte dellacreazione, proprio come l’uomo:“Tu e la pietra siete una cosa sola.Vi è differenza solo nei battitidel cuore. Il tuo cuore batte un po’più rapido.” In La roccia, simbolodi forza e solidità, i corpi siraggruppano delineando i contornidi un pugno serrato, a simboleggiarel’immortalità dell’esistenza, la suaeternità.“Bellezza è eternità che si contemplaallo specchio. Ma voi siete l’eternitàe siete lo specchio.” È lo Spiritodivino che chiede all’uomo di viveresecondo la bellezza, principio unitivodell’essere. L’esistenza, permeatadi gioia e di dolore, di materia edi spirito, mirandosi nello specchiodella bellezza può contemplare ilvolto dell’eternità. All’uomo comune,che confonde la bellezza con i suoidesideri insoddisfatti, Gibran diceche “la bellezza non è un bisogno,ma un’estasi”. Solo chi, come unBuddha, trascende ogni desiderio,

natura corporale. In Centauro ebambino è la donna a essereraffigurata nella sua dualità, nell’attodisperato, compassionevole, vano,lacerante, di sottrarre l’innocenzadel neonato al basso, oscuromondo materiale (dunya-), luogodell’afflizione, di cui lei stessa èineluttabilmente prigioniera. Ma,attraverso i suoi delicati e aggraziaticentauri, Gibran intende ancheindagare la misteriosa relazionetra il microcosmo dell’uomoe il macrocosmo. L’individuo, purconscio di essere intimamentecorrelato alla creazione e ai suoisviluppi cosmici, non riesce infattia definire il proprio rapporto diappartenenza con l’universo e conDio.L’arte gibraniana vorrebbe tentaredi esprimere proprio quell’unità chepone in stretta relazione l’uomo e lanatura, recuperando ogni elementoframmentario dell’esistenza perricondurlo a Dio. È la teoriasviluppata dai s.u-fı- della wah.datal-wugu-d (unità dell’Essere),secondo cui Alla-hè il solo essere vero e tutto ciò cheesiste non è che la manifestazionenella molteplicità dell’unicità divina.Ne deriva che l’unica via direalizzazione per l’uomo, chepartecipa della medesima esistenzadi tutte le cose create e presenti innatura, è quella di essere ricompresonel suo Creatore. Per Gibran l’artenon deve imitare la natura, macercare piuttosto di svelarne i misteri:“L’arte nasce quando la segretavisione dell’artista si accorda conla manifestazione della natura pertrovare nuove forme.” La cascata,La roccia e La montagna mostranoperciò corpi umani raggruppati

113

Creator. For Gibran, art must notimitate nature, its purpose being,rather, to unveil its mysteries: “Artis born when the artist’s secret visioncoincides with the manifestation ofnature in the search for new forms.”The Waterfall, The Rock, TheMountain, hence, are works thatreveal human bodies groupedtogether to assume the form that issuggested in the titles: “I want thisexhibit to be just the human formin its relation to other forms – trees,rocks – other forms of life – thatpeculiar wiry something.” Moreover,for Gibran, people must necessarilyonce again learn “the chastity of thenude”, because the body, enclosingwithin itself beauty and freedom,is the truest and noblest symbol oflife itself: “I always draw the bodiesnaked because life is naked. If I drawa mountain as a heap of humanforms or paint a waterfall in theshape of tumbling human bodies,it is because I see in the mountaina heap of living things, and in thewaterfall a precipitate current oflife.” The stone, like man, is also apart of creation: “You and the stoneare one. There is a difference only inheart-beats. Your heart beats a littlefaster.” In the work titled The Rock,it being a symbol of strength andsolidness, bodies are grouped todelineate the contours of a closedfist, thus symbolizing the immortalityof existence, its eternity.“Beauty is eternity gazing at itself inthe mirror. But you are eternity andyou are the mirror.” It is the divineSpirit that asks man to live accordingto beauty, the uniting principle ofbeing. Existence, permeated by joyand pain, by matter and spirit, maycontemplate the face of eternity by

to worldly existence (his hooves arewell-set in the ground), the humanbust of the fabled creature is archedand his arms are outstretched towardsthe sky, as he attempts to raisehimself from his beastly condition.It is the drama of the soul, whoseimpulses often remain miserablyfrustrated by corporeal nature. InCentaur and Child, it is a womanwho is portrayed in her duality, inthe desperate, compassionate, vain,lacerating act of keeping the innocenceof the newborn child from the lowly,obscure material world (dunya), aplace of affliction, where she herselfis inevitably a prisoner. But throughhis portrayal of delicate and gracefulcentaurs, Gibran’s purpose is alsothat of examining the mysteriousrelationship between the microcosmof man and the macrocosm. Man,although conscious of beingintimately related to the creationand to its cosmic developments,is incapable of defining his placein the universe and his belongingto God.It would be the purpose of Gibranianart to attempt to express preciselythat unity responsible for the closerelationship between man andnature, regaining each fragmentaryelement of existence in order to leadman back to God. This is the theorydeveloped by the Sufi of the wahdatal-wugud (the unity of Being) basedon which Allah is the only truebeing, and all else is nothing buta manifestation of the multiplicityof divine oneness. What derives fromthis is that the only way for man tofeel accomplished, as he participatesin the same existence of all thingscreated and present in nature, is forhim to be recomprehended in his

Page 112Woman with Garment, 1916.

Page 115The Waterfall, 1919.

ancora il dissidio interiore di ogniessere umano – due amori distinti madi pari intensità, due nature opposte,a rappresentare la sofferenzaestrema, lo strazio. Come scrisseMikhail Naimy, amico e biografodell’artista: “Esiste forse dolorepiù grande di quello dell’amoreche diventa una croce per chi ama?E del resto, quale gioia può esseremaggiore di quella dell’Amore checonduce alla croce, e dalle sofferenzedella croce alla beatitudinee all’emancipazione dell’Amoretrionfante?”La bellezza è infine per Gibran“un cuore in fiamme e un’animaincantata”, cioè la sola via checonduce al vero. Ma la via e la metanon sono diverse, la via stessa allafine diventa meta. Il primo passoè anche l’ultimo.

114

guardando con gli occhi dellospirito dalle vette supremedella consapevolezza, è capacedi comprendere il significatodella bellezza che è irriducibile auna sensazione corporea e sconcertala mente. La bellezza è appuntonell’estasi, nell’uscire fuori di sédella mente che abbandona ogniesperienza sensibile e intellettualenel raggiungimento di uno stato dicomunione e di identificazione con ildivino. Volo, che sembra rimandareal mito di Icaro, allude forse alfallimento di chi ritiene di potercomprendere Dio attraversoil solo intelletto. Oppure raffigurasemplicemente la tensione gioiosa,innata in ciascun individuo, ditornare a Dio, anzi di farsi Dio.Per il cristiano Gibran l’incarnazionedell’ideale sufico dell’“Uomoperfetto” (al-Insa-n al-Ka-mil), coluicioè che ha conseguito lo stato piùelevato di prossimità a Dio, è Gesù,l’amato “Maestro di luce”, mitoineguagliabile di bellezza estetica espirituale, prova certa dell’assolutapresenza di Dio all’uomo.La crocifissione è, secondo l’artista,la massima espressione dellagrandezza di Cristo, evento liberatoredalla materia la quale è la sola causadella sofferenza dell’individuo cheanela all’infinito. Crocifissorappresenta due figure umane che nesostengono una terza e dimostra inmodo esemplare come ci si possaservire dell’immagine tradizionale delCristo tra i due ladroni anche insenso simbolico – non vi sono infattielementi religiosi espliciti qualicroce, sangue o chiodi (ugualmenteallusivo è Il triangolo, che sembrarappresentare una sacra deposizione).Ciò che l’artista intende rendere è

MA

NUZ

IAN

ASu

Ven

ti d

iseg

ni

di K

ahlil

Gib

ran figure, and proves in exemplary

fashion how the traditional imageof Christ between the two thievesmay also be used in a symbolicsense – there are no explicit religiouselements such as the cross, bloodor nails to be seen here. (The Triangleis equally allusive, as it seems torepresent a sacred deposition.)That which the artist means toexpress is again the inner strifeof every human being – two lovesthat are distinct but of equalintensity, two contrasting natures,thus representing extreme suffering,agony. In the words of Gibran’sfriend and biographer MikhailNaimy: “What greater pain canthere be than the pain of lovebecoming a cross to the lover?On the other hand, what joy canbe greater than the joy of Loveleading to the cross, and from thepains of the cross to the bliss andemancipation of Love triumphant?”In short, beauty for Gibran is“a heart inflamed and a soulenchanted”, the sole path thatleads to truth. But the path andthe destination do not diverge;in the end, the path itself becomesdestination. The first step takenis also the last.

(Translation from Italianby Sylvia Notini)

114

looking at its own reflection in themirror of beauty. To the commonman who confuses beauty with hisunsatisfied needs Gibran saysthat “beauty is not a need but anecstasy”. Only he who, like Buddha,transcends every desire, observingthrough the eyes of the spirit fromthe highest peaks of awareness,is capable of understanding themeaning of beauty that cannot bereduced to a corporeal sensation,and that disconcerts the mind.Beauty lies, precisely, in ecstasy,in the mind’s emerging from itself,and that in so doing abandons eachand every sensitive and intellectualexperience in the achievementof a state of communion andidentification with the divine.Flight, which seems to refer tothe myth of Icarus, perhaps alludesto the failure of he who is convincedthat God may be understood throughintellect alone. Or perhaps it issimply the portrayal of the joyousand innate tension in each individualthat accompanies a return to God,rather, a becoming God.For the Christian Gibran, theincarnation of the Sufic ideal of the“Perfect Man” (al-Insan al-Kamil),that is, he who has obtained thehighest level of proximity to God,is Jesus, the beloved “Master oflight”, unequalled myth of aestheticand spiritual beauty, unwaveringproof of the absolute presenceof God before man. In the artist’sopinion, the crucifixion is the highestexpression of the greatness of Christ,an event that signifies freedom frommatter, the sole cause of sufferingman’s longing for the infinite.Crucified portrays two human figuresthat cling to and uphold a third

Francesco MediciFrancesco Medici is a literary criticand translator, and one of Italy’sforemost experts in the work of theLebanese poet and painter KahlilGibran. He has translated in ItalianGibran’s theatrical texts Lazarusand His Beloved (Lazzaro e ilsuo amore, 2001) and The Blind(Il cieco, 2003), and the collectionof unpublished writings andfragments entitled La stanza delProfeta (2004), and The Prophet(Il Profeta, 2005 and 2006). He isalso the author of the comparativestudy Il dramma di Lazzaro. KahlilGibran e Luigi Pirandello (2002),and Kahlil Gibran. Venti disegni(2006), which reproduces TwentyDrawings by Gibran. He hasrecently published the monographLuzi oltre Leopardi. Dalla formaalla coscienza per ardore (2007).

MA

NUZ

IAN

AO

nT

wen

ty D

raw

ings

by K

ahlil

Gib

ran