Focus on Clinical Inertia

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Focus on Clinical Inertia

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Changing Provider Behaviorin the Context of ChronicDisease Management: Focuson Clinical InertiaKim L. Lavoie,1,2 Joshua A. Rash,3

and Tavis S. Campbell31Department of Psychology, University of Quebec at Montreal (UQAM), Montreal, QuebecH3C 3P8, Canada2Montreal Behavioural Medicine Centre (MBMC), Research Centre, Hopital du Sacre-Coeurde Montreal, Montreal, Quebec H2J 1C5, Canada3Department of Psychology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N 1N4, Canada;email: [email protected]

Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017. 57:263–83

First published online as a Review in Advance onSeptember 7, 2016

The Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicologyis online at pharmtox.annualreviews.org

This article’s doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104952

Copyright c© 2017 by Annual Reviews.All rights reserved

Keywords

clinical inertia, therapeutic inertia, diagnostic inertia, clinical practiceguidelines, evidence-based medicine

Abstract

Widespread acceptance of evidence-based medicine has led to the prolifer-ation of clinical practice guidelines as the primary mode of communicatingcurrent best practices across a range of chronic diseases. Despite overwhelm-ing evidence supporting the benefits of their use, there is a long history ofpoor uptake by providers. Nonadherence to clinical practice guidelines isreferred to as clinical inertia and represents provider failure to initiate orintensify treatment despite a clear indication to do so. Here we review ev-idence for the ubiquity of clinical inertia across a variety of chronic healthconditions, as well as the organizational and system, patient, and providerfactors that serve to maintain it. Limitations are highlighted in the emergingliterature examining interventions to reduce clinical inertia. An evidence-based framework to address these limitations is proposed that uses behav-ior change theory and advocates for shared decision making and enhancedguideline development and dissemination.

263

Click here to view this article'sonline features:

• Download figures as PPT slides• Navigate linked references• Download citations• Explore related articles• Search keywords

ANNUAL REVIEWS Further

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Evidence-basedmedicine (EBM): asystematic applicationof the scientificmethod into health-care practice with thegoal of providingoptimal care topatients

Clinical practiceguidelines (CPGs):systematicallydevelopedrecommendationsinformed by a reviewof evidence andassessment of thebenefits and harms ofalternative careoptions

Clinical inertia:failure to initiate orintensify treatmentdespite a clearindication andrecognition to do so

Evidence-based medicine (EBM), whose origins date back to the mid-nineteenth century (1), is thesystematic application of the scientific method into health-care practice with the goal of providingoptimal clinical care to patients (2). Inherent in this definition is the expectation of explicit andjudicious use of current best evidence to guide clinical decision making. EBM is a constantlyevolving process; as more evidence becomes available, old tests and treatments are replaced withmore accurate, powerful, effective, and safer ones. Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have becomethe primary mode of communicating current best practices across a range of clinical disorders (3).The ultimate goal of practice guidelines is to facilitate the translation of the most recent evidenceinto practice to improve patient care and outcomes (4).

Despite their widespread availability and strong evidence supporting the benefits of their use(5–7), there is a long history of poor uptake of CPGs by providers, with many studies reporting ratesof nonadherence at or exceeding 50% (8–10). Rates of provider nonadherence to guidelines are saidto be responsible for up to 80% of myocardial infarctions and strokes in the context of suboptimallytreated hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (11). Practice guidelines have been criticized forbeing overly simplistic, impractical, biased, and not broadly applicable and for representing a threatto professional autonomy and the provider-patient relationship (4, 12). However, the intentionof CPGs is not to provide a black and white, cookbook approach to diagnosis and treatment, butrather to facilitate a bottom-up approach that integrates the best external evidence with clinicalexpertise that considers individual patients’ goals, values, and preferences when making decisionsabout care (1).

Provider nonadherence to CPGs is increasingly referred to as clinical inertia. This term wasinitially introduced by Phillips et al. (13) in 2001 and defined as provider failure to initiate orintensify treatment despite a clear indication and recognition of the need to do so. Other termshave been used to describe the same behavior, including therapeutic inertia, physician inertia,and diagnostic inertia (14–16), but they are generally synonymous and reflect conscious providerinaction in the face of available and explicit evidence-based guidelines and recognition of the needto act.

In an era of chronic disease that demands the practice of EBM to achieve optimal clinicaloutcomes, overcoming the problem of clinical inertia is imperative. Here we review current def-initions of clinical inertia and summarize its prevalence and impact across a range of chronicdiseases. We also review barriers to provider adherence to CPGs and summarize the efficacy ofprovider-focused interventions. Finally, we propose the adoption of a theoretical framework forunderstanding and overcoming the problem of clinical inertia that is grounded in health behaviorchange theory and can be used to improve future implementation strategies.

DEFINING CLINICAL INERTIA

To consider provider behavior as reflecting clinical inertia, at least two conditions must be met:(a) The patient fails to meet clearly defined and measurable treatment targets, and (b) the patientfails to receive appropriate intensification of therapy within a defined and reasonable period oftime (11). Clinical inertia may also apply to the failure to stop or reduce therapy that may nolonger be needed; although this side of clinical inertia also has important clinical consequences(17), it has received far less attention.

One issue regarding the definition of clinical inertia is how to distinguish true clinical inertiafrom what may in fact be appropriate clinical inertia, which reflects reasonable decisions not tointensify treatment despite the available evidence. This may occur with more complex cases (e.g.,a frail elderly patient with diabetes and hypertension) or when age, comorbidities, polypharmacy,and potential adverse drug reactions may render guideline-recommended therapies inappropriate

264 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

(13) or unsafe (18). More recent definitions of clinical inertia take these concerns into account(19) and suggest that true clinical inertia occurs only when the following criteria are met: Theprovider (a) is aware of the existence of implicit or explicit guidelines; (b) believes that this guidelineapplies to the patient; (c) has resources available to apply the guideline; and (d ) does not followthe guideline despite awareness, belief, and available resources to do so. Although this may bethe most appropriate and balanced definition of clinical inertia, most studies to date have definedclinical inertia based on observations of providers’ failure to intensify treatment in the context ofpatients not meeting measurable therapeutic targets. However, without systematically consultingclinical data such as medical charts, it is impossible to verify the extent to which clinical inertia maybe appropriate (e.g., in the context of severe comorbidities) or the result of patient nonadherence.

THE PROBLEM OF CLINICAL INERTIA: PREVALENCE AND IMPACT

Evidence for clinical inertia comes from epidemiological studies, direct observation, or an analysisof provider behavior during clinical visits. The challenge in reporting prevalence rates of clinicalinertia is that it has been defined inconsistently and measured imprecisely across studies. In general,it is easier to measure clinical inertia in relation to conditions where treatment targets, intensifi-cations, and timelines are well defined, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Rates ofclinical inertia have been studied most extensively within the context of these conditions and to alesser extent in the context of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and aretypically quantified as instances when providers fail to intensify treatment among diagnosed pa-tients who are not meeting targets. These cases do not consider the reasons for provider inaction,some of which may be appropriate, representing a major limitation in this area of research.

Diabetes

There is little question that the timely initiation and intensification of insulin, glucose-loweringmedication, or both in diabetes is associated with clinically relevant benefits, including improvedglycemic control and a reduction in microvascular complications (20–23). Despite this, a reviewby Phillips et al. (13) revealed that in the United States, only 65% of patients were diagnosedaccurately, and among those, only 73% were given pharmacological therapy. It is not surprising,therefore, that hemoglobin A1c values met American Diabetes Association targets in only 7% ofpatients. A more recent study using a retrospective cohort of more than 81,000 patients with type 2diabetes from the United Kingdom reported that over 50% of patients with poor glycemic controldid not receive intensification of oral antidiabetic medication within 7 years of treatment (24).Finally, a study from Canada using administrative data from more than 80,000 patients compared4-month drug intensification by specialists and general practitioners among 2,652 matched caseswith uncontrolled diabetes (25). Although specialists intensified treatment in a greater proportionof cases (45.1%) than general practitioners did (37.4%), overall rates were less than 50% (26).

Hypertension

Similar to diabetes, clinical inertia is prevalent in the management of hypertension. The reviewby Phillips et al. (13) indicated that in the United States, only 69% of patients were diagnosedaccurately, and among those, just over half (53%) were given pharmacological therapy. Thisexplains why only about 45% of patients had adequate blood pressure (BP) control. In a morerecent study of more than 21,000 respondents of a nationally representative survey in five Europeancountries and the United States, Wolf-Maier et al. (27) reported that among those with poorly

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 265

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

controlled BP, only 14–26% of patients in Europe and 32% of patients in the United States receivedtreatment intensification. Finally, in a study conducted within Veteran Affairs (VA) primary careclinics, clinical inertia was identified in 66% of cases. Moreover, among victims of clinical inertia,nearly one-quarter had no follow-up appointment scheduled, and nearly 77% of those who didsee their provider did so after a delay of 45 days (range: 29–78 days) (28).

Suboptimal management of hypertension has been shown to have a major impact on BP control.For example, in a sample of more than 7,000 hypertensive patients from the United States whowere followed for an average of 6.4 appointments over the course of a year, Okonofua et al. (16)calculated that clinical inertia accounted for 19% of the variance in BP control. Furthermore, theauthors estimated that BP could be controlled in 20% more patients (an increase from 45.1% to65.9%) in one year if clinical inertia could be reduced by 50%.

Dyslipidemia

Clinical inertia is also common in the context of dyslipidemia, for which the review by Phillipset al. (13) revealed that only 47% of patients in the United States were diagnosed accurately, andamong those, the minority (17–23%) were given pharmacological therapy. This helps to explainwhy low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels reach National Cholesterol EducationProgram targets in only 14–38% of patients. More recently, clinical inertia in dyslipidemia wasevaluated in a sample of 22,888 patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) (29). Only 32% ofthe 6,538 patients who failed to meet treatment targets (LDL-C ≥ 100 mg/dL) received intensi-fication of cholesterol-lowering therapy within 45 days of their elevated laboratory test. Finally,an 18-month, retrospective cohort study (30) used medical records from 253,238 members of theKaiser Permanente Medical Care Program who had poor control of dyslipidemia, diabetes, orBP to quantify clinical inertia, which was defined as the failure of the provider to intensify phar-macotherapy within 6 months. Clinical inertia was observed in 41.4% of patients with elevatedLDL-C levels, as well as 30.3% of patients with elevated hemoglobin A1c levels, 28.8% withelevated systolic BP, and 17.6% with elevated diastolic BP.

Asthma

In developed countries, asthma is often the most prevalent chronic disease in children and one ofthe most common conditions affecting adults (31, 32). Despite the availability of guidelines forthe treatment of asthma and robust evidence that following guideline recommendations improvesoutcomes (33, 34), provider adherence to CPGs to manage asthma is poor. For example, a retro-spective study of asthma care delivered to 345 patients at a tertiary adult emergency department(ED) in Canada reported 69.6% overall compliance with guidelines (35). Controller (i.e., inhaledcorticosteroid) use was prescribed in only one-third of children and adults in the ED and on dis-charge. Studies have also shown that in the nonacute care setting, few physicians prescribe ongoingdaily controller medication or written self-management plans, even in adults and children with arecent acute care visit for asthma (36). Moreover, even when they are prescribed, the cumulativeduration of available prescriptions covers less than 50% of the follow-up period (37).

One possible explanation for these high rates of clinical inertia may be diagnostic inertia.Lougheed et al. (38) assessed ED management of asthma in 2,671 children and 2,078 adultstreated at 16 Ontario hospitals by means of questionnaires and chart reviews. Objective measuresof airflow rate were documented in only 27.2% of pediatric visits and 44.3% of adult visits.Given that CPGs make specific recommendations about treatment intensification based on lungfunction (39, 40), the failure to measure this at the point of care will make it difficult to implementguideline-recommended therapy.

266 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects 65 million people worldwide (41) andis the third-leading cause of death in the United States after CVD and cancer (42). Althoughstudied less extensively than in other diseases, diagnostic and clinical inertia in COPD are alsoprevalent concerns. A comprehensive review by Cooke et al. (43) in 2012 reports that in 2002, only10 million adults in the United States were diagnosed with COPD, despite Third National Healthand Nutrition Examination Survey estimates that 24 million adults had impaired lung function.The most common reason for the underdiagnosis of COPD was the lack of objective lung functiontesting (spirometry). One survey of primary care practices revealed that despite 66% of providersowning a spirometer, 38% said they were unfamiliar with the test and 34% said they were nottrained to administer or interpret it (44).

With regards to clinical inertia, Cooke et al. (43) reported that 23–38% of COPD patients fail toreceive any guideline-recommended drug therapy (45–47). However, these rates vary dependingon disease stage, with one study reporting higher rates of treatment (81%) among patients withsevere COPD compared to those with moderate (72%) and mild (44%) disease (48). Amongthose receiving treatment, one study conducted among patients seen at a university-based familymedicine clinic reported that treatment intensity is often suboptimal, with only 55% of patientsreceiving stage-recommended therapy (49). Specifically, Chavez & Shokar (49) reported thatonly 22%, 5%, 28%, and 13% of patients with mild, moderate, severe, and very severe COPD,respectively, were being treated at stage-recommended levels.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH CLINICAL INERTIA

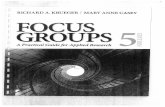

To address the problem of clinical inertia, factors that explain its high prevalence must be eluci-dated. Reasons for clinical inertia involve a complex interaction between three types of factors:organizational and system, patient, and provider factors, for which previous reports have estimatedtheir relative contributions at 20%, 30%, and 50%, respectively (11) (see Figure 1). Reviews (4,11, 13, 15, 50) and textbooks (19) that detail these factors have been published, so we considerthem only briefly here with an emphasis on modifiable, provider-related factors.

Organizational and System Factors

Time constraints are one of the most cited organizational and system-related factors associatedwith clinical inertia. Providers often have several competing demands [e.g., high patient volumes,teaching and research responsibilities, acquiring continuing medical education (CME) credits,office management, staff supervision] (13, 14, 51) that may interfere with the ability to keep upwith constantly evolving clinical guidelines and prevent the thorough assessment, diagnosis, andtimely provision of treatment initiation or intensification (52). This may be complicated furtherby the lack of available resources to implement guideline-recommended therapy (e.g., limited sup-port staff, diagnostic equipment, access to laboratory services, office space), as well as inadequatereimbursement for implementing guideline-recommended therapy (4). Factors associated with thepractice setting (e.g., primary care, inner-city or rural setting, lack of or limited access to multidis-ciplinary expertise or specialists) may also contribute to clinical inertia (50). For example, someresearchers have argued that the lack of availability of multidisciplinary team–based care, whichis often the case in primary care, may be an important factor associated with increased clinicalinertia in primary (relative to tertiary) care settings (50, 53–55). Finally, access to care, prescriptiondrugs, or insurance (which may also be considered a patient factor) is an important contributor to

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 267

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Organizational andsystem factors Provider factors Patient factors

Time constraints• High patient volumes• Competing demands

Knowledge• Insufficient awareness or

familiarization with guidelines• Large volume of guidelines• Inaccessibility of guidelines

Demographics• Older age, female sex, socioeconomic

and cultural characteristics, and lowhealth literacy and education

Medical history• ComorbiditiesAgreement with and applicability

of guidelines• Uncertainty about applicability• Uncertainty about implementation• Uncertainty about accuracy or

consistency of risk factor values

Beliefs, attitudes, and preferences• Unwillingness to accept diagnosis

and/or take medication• Preference for or against treatment

Resources• Lack of support staff and equipment• Inadequate or poor reimbursement

Setting• Primary care, inner-city, or rural• No access to multidisciplinary team

Access to care• Poor access to care or inadequate

(or absent) insurance coverage

Cognitive biases• Overestimating care provided• Underestimating treatment needed

Self-efficacy• Lack of confidence in

ability to enact guidelinesTreatment adherence

• Patient beliefs about risks and benefitsof treatment

• Provider perceptions of nonadherencemay create negative expectancy biasMotivation

• Overcoming old habits and routines• Readiness to make a change

Lifestyle factors

• Smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity,and alcohol use

Figure 1Organizational and system, provider, and patient factors associated with clinical inertia.

clinical inertia. In one study, 38% of patients with COPD reported that insurance-related issueslimited access to prescription drugs and 14% reported limited access to physician office visits (48).Furthermore, 58–67% of providers reported that insurance coverage for needed treatment wasinadequate or unreasonable (48). However, it is noteworthy that clinical inertia is common in VAhospitals and in countries such as Canada, where medication costs may be less of an issue (37, 56).

Patient Factors

Patient-related factors may also underlie clinical inertia. One such factor involves patient demo-graphics, including older age, female sex, and socioeconomic or cultural background (which mayundermine health literacy) (50). For example, in a cross-sectional retrospective study of 1,729medical and insurance claims, Nau & Mallya (57) reported that among patients with diabetes,men were more likely than women to receive lipid tests (82.4% versus 79.4%) and lipid-loweringmedication (45.5% versus 33.2%). Furthermore, patients with more education and better healthliteracy appear less likely to experience clinical inertia (50).

Another factor relates to patients’ medical history. Many studies have indicated that treatmentis less likely to be initiated or intensified if patients have complex comorbidities (e.g., a psychiatricor neurological disorder, substance abuse, terminal illness) because this may raise questions aboutthe applicability or appropriateness of existing guidelines (50).

Patient-related beliefs, attitudes, and preferences have also been linked to clinical inertia. Forexample, clinical inertia may reflect a patient’s unwillingness to accept their diagnosis or take a

268 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Cognitive biases:systematic deviationsfrom standards injudgment

Self-efficacy: beliefor confidence in theability to implementguidelines and enactmeaningful change

medication to manage what they may experience as an asymptomatic disease (e.g., hypertensionand dyslipidemia) (50). EBM emphasizes patient preferences, and in some cases, patients mayopt for lifestyle modifications (e.g., dietary changes or increases in physical activity) prior to theinitiation or intensification of medications (58).

Patient nonadherence, the reasons for which are multifactorial (e.g., medication cost, diseasenonacceptance, fear of side effects, poor outcome expectancies, forgetfulness) and exacerbated byprovider factors [e.g., poor communication skills (14)], may also contribute to clinical inertia. Forexample, medication adherence was found to predict 3-year treatment intensification in a cohort of2,065 insured patients with type 2 diabetes newly started on hypoglycemic therapy (59). Patients inthe lowest quartile of adherence were less likely to have their medication appropriately intensifiedthan patients in the highest quartile (27% versus 37%), which equated to 53-fold lower oddsof treatment intensification after having an elevated hemoglobin A1c. Established or suspectedpatient nonadherence by providers may also contribute to clinical inertia by creating a negativeexpectancy bias (50). In these cases, providers may fail to provide guideline-recommended therapyowing to low expectations of adherence and perceived helplessness to change patient behavior.Some researchers have argued that clinical inertia and lack of patient adherence go hand in handand that this represents a shared failure to give preference to the long-term benefit of treatmentintensification (60).

Finally, lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity), by virtue of raising thebar for achieving clinical targets, may also be linked to clinical inertia (14). For example, theEUROASPIRE study reported that, despite treatment intensification, patients with coronaryheart disease failed to achieve BP targets, and nearly 50% of patients remained above target lipidlevels 6 months after percutaneous intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, or hospitalizationfor acute ischemia or myocardial infarction (61). This study further revealed concomitant increasesin obesity (from 25% to 38%) and diabetes (from 17% to 28%) between EUROASPIRE I andIII, suggesting an important role for lifestyle factors in explaining the treatment failures.

Provider Factors

The strongest contributors to clinical inertia are factors related to the provider and have beenthe most intensely studied (4, 11, 13, 28, 50). In general, five factors have been identified: (a) lackof knowledge or awareness of clinical guidelines, (b) lack of agreement with guidelines or theirapplicability, (c) cognitive biases, (d ) motivational factors, and (e) low self-efficacy to implementguidelines.

Lack of knowledge or awareness. Lack of awareness or familiarity with evidence-based guide-lines for chronic disease management has been reported as a major contributor of clinical inertia(4, 50, 52, 62). In a review of 46 surveys, Cabana et al. (4) observed that lack of awareness wasreported as a barrier to guideline implementation in a median of 54.5% of respondents. Similarly,41% of respondents had not heard of nationally endorsed BP guidelines in a US survey of pri-mary care physicians (63). In the context of COPD, only about half of primary care physicians arereportedly aware of CPGs (48), and only 25% said they used them for clinical decision making(64). Recent reviews continue to note this as an important barrier (65), which may be exacer-bated by the large number of guidelines and the time required to keep them constantly updated(62).

Lack of agreement and applicability. Another important provider-related factor is lack ofagreement with guidelines or their applicability to certain patients. Multiple reasons for this

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 269

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

problem have been identified, including doubting the credibility of the evidence, doubting thatthe benefits of therapy outweigh the risks, the perception that guidelines would reduce providerautonomy, and the belief that guidelines undermine the provider-patient relationship by reduc-ing patient choice (4). Guidelines have also been criticized for being overly simplified, leadingto disagreement about their applicability to individual patients or populations (4, 50). This lat-ter claim is not entirely unfounded, given that guidelines are typically informed by randomizedcontrolled trials with strict inclusion or exclusion criteria that may limit their applicability tocertain patients. Provider beliefs about applicability may also be influenced by patient factorssuch as demographics (e.g., age, sex), medical history, comorbidities, patient preferences, andperceptions of patient adherence. Uncertainty regarding the accuracy, consistency, or both ofrisk factor values may also contribute to perceptions of guideline applicability. This is partic-ularly prevalent in the treatment of hypertension, in which discrepancies between office andhome BP are common (53). Other reasons have to do with the nature of the guideline it-self. Guidelines have been criticized for being written in a way that does not always facilitatetheir use. Cabana et al. (4) noted that across 23 surveys, 17%, 11%, 10%, and 4.5% of physi-cians reported that guidelines were not easy to use, inconvenient, cumbersome, and confusing,respectively.

Cognitive biases. Cognitive biases represent systematic deviations from standards in judgment.In the context of clinical inertia, providers may have systematic cognitive biases that underminethe timely delivery and intensification of treatment. For example, providers routinely underesti-mate the need to intensify therapy (11). A study by el-Kebbi et al. (66) reported that physiciansdid not intensify diabetes therapy over a 2–3-month period among diabetic patients owing to mis-perceptions of control in 41% of cases—despite most patients being obese (body mass index =32 kg/m2). Similarly, health-care providers have been shown to overestimate the care they pro-vide (67). In a survey about the use of CPGs for the treatment of hypertension, US primary careclinicians overestimated the proportion of patients who were prescribed guideline-recommendedmedication (75% perceived versus 65% actual) as well as the proportion of patients whose BPlevels were below target levels set at their previous visit (68% perceived versus 43% actual)(68).

Motivational factors. Motivation reflects a general desire or willingness to engage in a particularbehavior and may be influenced by both extrinsic (e.g., money, praise, status, power) and intrin-sic motivators (e.g., pleasure, behavior is consistent with personal goals or values) (69). Clinicalinertia may reflect a lack of provider motivation to change practice behavior. Habits are hardto change, even those related to clinical practice, where as many as 20% of providers report alack of motivation (i.e., desire or perceived importance) as a barrier to the provision of guideline-recommended therapy (4). A related factor that may serve to undermine motivation is outcomeexpectancies, which is the expectation that behavior will lead to a particular outcome (70). In thereview by Cabana et al. (4), 26% of providers reported negative outcome expectancies, whichcould be influenced by perceived lack of treatment efficacy, guideline nonapplicability, or patientnonadherence, to be a barrier to following CPGs.

Self-efficacy. Providers’ belief or confidence in their ability to implement guidelines and enactmeaningful practice change represents another barrier to the timely delivery or intensificationof treatment. Cabana et al. (4) observed that a median of 13% of respondents across 19 surveysreported limited self-efficacy as a barrier to the implementation of CPGs. Similar results were

270 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Science-practice gap:the divide betweenresearch literatureconcerning clinicalinterventions and itsapplication to patients

reported in a survey of 154 clinicians treating COPD patients (71). Self-efficacy beliefs may beinfluenced heavily by organizational barriers such as time and available resources.

INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE CLINICAL INERTIA

Various strategies have been employed to encourage providers to bridge the science-practice gapby changing clinical practice behavior. Interventions may be grouped into five broad categories:educational approaches, practice audit and feedback, decision support approaches, incentives, andmultifaceted interventions (see Table 1 for a summary of definitions and examples).

Educational approaches range from passive interventions, such as the dissemination of printedmaterials, the use of opinion leaders to impart knowledge, and traditional didactic lectures andconference presentations, to more active approaches, including academic detailing and engagingforms of CME (e.g., practical workshops). Educational approaches target provider knowledge orawareness of guideline-recommended therapy. A recent review of 105 CME studies reported that58% of 105 studies improved physician practice behavior (e.g., prescribing), with more activeforms of CME and those using multiple media formats (e.g., slides, videos), multiple instructiontechniques (e.g., didactic lectures, interactive group discussions, practical exercises), and multipleexposures showing greater efficacy (72). In contrast, more passive forms of CME show smaller butreliable effects on changing practice behavior.

Audit and feedback involves reviewing clinical performance over a specific period of time viachart audits, patient surveys, or direct observation and giving providers specific feedback on thequality of their performance. This approach helps providers recognize cognitive biases (e.g., over-estimation of care). According to reviews by Mostofian et al. (73) and Yen (74), audit and feedbackhas been associated with a range of effects on provider behavior, with studies showing small (16%decrease in physician compliance) to large effects (70% increase in physician compliance). Fur-thermore, the larger positive effects (74) were associated with lower baseline compliance amongproviders, and feedback was most effective when delivered prior to making decisions about clinicalcare (73).

Decision support approaches are information systems designed to improve clinical decisionmaking by analyzing patient-specific variables (e.g., clinical data) and using the data provided togenerate treatment recommendations. These approaches are passive and often involve remindersor simplified decision algorithms for preventive interventions, prescribing, and dosing. They targetprovider knowledge or awareness of guideline-recommended therapy, cognitive biases, and self-efficacy. Decision support systems reportedly improved provider performance in 64% of studies(75) and were particularly effective when triggered automatically during clinic practice (68% ofstudies) (76). Reminders can also have large effects on practice behavior. One review reported thatcomputerized prompts for prevention activities improved physician performance in 76% of trials(75). However, decision support systems need sufficient data to code and trigger a response andthe support system and reminders in place to trigger appropriate provider behavior.

Incentives come in the form of financial or other rewards (e.g., institutional accreditation).Incentives target provider motivation. Although effective in 70% of studies (77), this approachtargets extrinsic rather than intrinsic motivations, meaning that the behavior may extinguish inthe absence of ongoing reinforcement.

Multifaceted interventions do not encompass a single approach but rather seek to combinemultiple approaches to optimize efficacy. In general, approaches that combine more than onestrategy (e.g., education, audit and feedback, reminders, simplification of treatment regimens)have been found to be highly effective in changing physician practice behavior, with overall successrates exceeding 70% (74, 78, 79).

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 271

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Tab

le1

Cha

ract

eris

tics

ofin

terv

enti

ons

tore

duce

clin

ical

iner

tia

Beh

avio

rch

ange

met

hod

Defi

niti

onB

ehav

ior

chan

geth

eory

App

roac

hP

rovi

der

barr

iers

addr

esse

dE

ffica

cyE

xam

ple

Oth

erco

nsid

erat

ions

Edu

cati

onal

appr

oach

es

Pri

nted

educ

atio

nal

mat

eria

lsD

istr

ibut

ion

ofpr

inte

dre

com

men

datio

nsfo

rcl

inic

alca

re(e

.g.,

prac

tice

guid

elin

es)

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

sL

owM

aile

dgu

idel

ines

and

mai

led

guid

elin

espl

used

ucat

ion

outr

each

did

notc

hang

epr

escr

iptio

nof

NSA

IDs

rela

tive

tono

inte

rven

tion

(90)

.

Hig

hly

vari

able

and

diffi

cult

tode

term

ine

qual

ities

ofm

ore

succ

essf

ulin

terv

entio

ns(9

1)

Loc

alop

inio

nle

ader

sT

rans

mis

sion

ofop

inio

nsof

heal

th-c

are

prov

ider

swho

are

deem

edin

fluen

tial

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

sL

owA

one-

page

,dis

ease

-spe

cific

sum

mar

yen

dors

edby

anop

inio

nle

ader

show

edsm

all

impr

ovem

ents

inph

ysic

ian

pres

crip

tion

ofca

rdio

vasc

ular

med

icat

ion

(92)

.

Effe

ctiv

ely

used

with

othe

rst

rate

gies

;hig

hly

vari

able

and

diffi

cult

tode

term

ine

best

way

toop

timiz

eus

e(9

3)

Aca

dem

icde

taili

ngA

ctiv

ein

form

atio

ntr

ansf

erth

roug

hpr

esen

tatio

nsby

atr

aine

dpe

rson

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

sL

owR

elat

ive

toco

ntro

l,el

ectr

onic

and

dire

ct(f

ace-

to-f

ace)

acad

emic

deta

iling

incr

ease

dlik

elih

ood

oflip

idte

stin

gfo

rdi

abet

ics(

94).

Pro

duce

ssm

allb

utre

liabl

eef

fect

sw

hen

used

alon

eor

com

bine

dw

ithot

her

met

hods

(95)

CM

EP

assi

vefo

rms

incl

ude

info

rmat

ion

prov

ided

via

educ

atio

nalc

onfe

renc

es,

lect

ures

,or

mee

tings

;act

ive

form

sin

clud

eta

ilore

dle

arni

ngan

dpr

actic

alw

orks

hops

Var

iabl

eA

ctiv

eor

pass

ive

Pas

sive

:lac

kof

know

ledg

ean

daw

aren

ess

Act

ive:

mul

tiple

Mod

erat

eT

wo

2–3-

hin

tera

ctiv

ese

min

ars

toim

prov

eco

mm

unic

atio

nw

ithch

ildre

nw

ithas

thm

ain

crea

sed

use

ofco

ntro

ller

med

icat

ion

and

redu

ced

asth

ma-

rela

ted

hosp

ital

visi

ts(9

6).

Mos

teffe

ctiv

ew

hen

(a)b

oth

inte

ract

ive

and

dida

ctic

,(b

)hig

hly

atte

nded

,and

(c)c

hang

ing

sim

ple

beha

vior

s(97

)

Aud

itan

dfe

edba

ckap

proa

ches

Aud

itan

dfe

edba

ckR

esul

tsof

revi

ewso

fclin

ical

perf

orm

ance

(e.g

.,ch

arts

,su

rvey

s,ob

serv

atio

n)ar

efe

dba

ckto

the

prov

ider

Non

eA

ctiv

eC

ogni

tive

bias

esM

oder

ate

Aud

itsof

acut

eas

thm

apr

oced

ures

wer

ean

onym

ized

and

fed

back

topr

ovid

ers,

whi

chin

crea

sed

use

ofpe

akflo

wby

45%

(98)

.

Mos

teffe

ctiv

ew

hen

(a)d

eliv

ered

bya

supe

rvis

oror

colle

ague

,(b

)per

form

ance

islo

wto

begi

nw

ith,(

c)pr

ovid

edm

ultip

letim

es,

and

(d)c

lear

targ

ets

are

used

(99)

Dec

isio

nsu

ppor

tap

proa

ches

Ana

lysi

sof

patie

ntda

taN

ewcl

inic

alin

form

atio

nco

llect

eddi

rect

lyfr

ompa

tient

san

dgi

ven

toth

epr

ovid

er

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

sM

oder

ate

Pat

ient

self-

repo

rts

ofde

pres

sed

moo

din

unre

cogn

ized

depr

esse

dpa

tient

sw

ere

fed

back

toph

ysic

ians

,whi

chim

prov

ed12

-mon

thre

cogn

ition

and

trea

tmen

tofd

epre

ssio

n(1

00).

The

circ

umst

ance

sun

der

whi

chth

isst

rate

gyis

mos

teffi

caci

ous

are

noty

etkn

own

272 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Dec

isio

nsu

ppor

tsys

tem

sIn

form

atio

nsy

stem

sth

atan

alyz

epa

tient

-spe

cific

clin

ical

vari

able

s(e

.g.,

prev

entiv

eca

re,d

isea

sem

anag

emen

t,pr

escr

ibin

g)

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

s,la

ckof

agre

emen

t

Mod

erat

eR

elat

ive

tous

ualc

are,

aco

mpu

ter-

assi

sted

deci

sion

supp

ortp

rogr

amta

rget

edan

dre

duce

dth

epr

escr

ibin

gof

9in

appr

opri

ate

med

icat

ions

inan

ED

sett

ing

(101

).

Mos

teffe

ctiv

ew

hen

(a)a

dvic

egi

ven

for

patie

nts

and

prac

titio

ners

,(b)

requ

irin

gpr

ovid

erre

ason

for

over

ride

,an

d(c

)eva

luat

edby

deve

lope

rs(7

6,10

2)L

imita

tions

:ale

rts

may

bedi

srup

tive,

prov

ider

may

not

agre

ew

ithad

vice

,and

cont

inge

ntup

onqu

ality

ofda

ta(1

5)

Rem

inde

rsM

anua

lor

com

pute

rize

dpr

ompt

sdi

rect

ing

phys

icia

nsto

perf

orm

asp

ecifi

ccl

inic

alac

tion

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

sM

oder

ate

Com

pute

rize

dre

min

ders

ofpa

tient

-spe

cific

reco

mm

enda

tions

for

elev

ated

gluc

ose

impr

oved

the

timel

yin

tens

ifica

tion

oftr

eatm

ent

(103

).

Use

def

fect

ivel

yw

ithot

her

stra

tegi

es(1

04)

Sim

plifi

catio

nof

regi

men

The

use

ofsi

mpl

ified

deci

sion

algo

rith

ms

for

trea

tmen

tre

gim

ens

Non

eP

assi

veL

ack

ofkn

owle

dge

and

awar

enes

s(gu

idel

ine

com

plex

ity)

Mod

erat

eA

sim

plifi

edfo

ur-s

tep

algo

rith

mto

man

age

hype

rten

sion

impr

oved

timel

yin

tens

ifica

tion

ofan

tihyp

erte

nsiv

em

edic

atio

ns(1

05).

The

circ

umst

ance

sun

der

whi

chth

isst

rate

gyis

mos

teffi

caci

ous

are

noty

etkn

own

Ince

ntiv

eap

proa

ches

Eco

nom

icin

cent

ives

Fina

ncia

lrew

ards

orpe

nalti

esfo

ren

gagi

ngin

spec

ific

clin

ical

prac

tices

Lea

rnin

gth

eory

(pos

itive

rein

forc

emen

tor

puni

shm

ent)

Pas

sive

Lac

kof

mot

ivat

ion

Mod

erat

eP

rovi

der

finan

cial

bonu

s(e

.g.,

$1,0

00fo

ra

20%

impr

ovem

ent)

impr

oved

phys

icia

nim

mun

izat

ion

beha

vior

by25

.3%

(106

).

Effe

ctsd

ono

ttra

nsfe

rto

patie

ntou

tcom

es(7

7)

Mul

tifa

cete

dap

proa

ches

Mul

tifac

eted

Use

oftw

oor

mor

ein

terv

entio

nsV

aria

ble

depe

ndin

gon

inte

rven

tions

used

Act

ive

and

pass

ive

Mul

tiple

Hig

hE

duca

tiona

lout

reac

h,au

dita

ndfe

edba

ck,r

emin

ders

,opi

nion

lead

ered

ucat

ion,

and

regi

men

sim

plifi

catio

nim

prov

edth

ead

optio

nof

targ

eted

prac

tices

intr

eatm

entI

CU

s(1

07).

Has

been

rate

das

the

mos

tsu

cces

sful

inte

rven

tion

stra

tegy

toch

ange

phys

icia

nbe

havi

orfo

ra

desi

red

outc

ome

(73)

Abb

revi

atio

ns:C

ME

,con

tinui

ngm

edic

aled

ucat

ion;

ED

,em

erge

ncy

depa

rtm

ent;

ICU

,int

ensi

veca

reun

it;N

SAID

,non

ster

oida

lant

i-in

flam

mat

ory

drug

.

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 273

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Behavior changetheory (BCT):the application oftheoretically informedmethods to targetidentified barriers andbring about desiredbehavior change

Shared decisionmaking (SDM):empowering patientsto assume a central orshared role in makingdecisions about theirmedical care

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT APPROACHES TO OVERCOMINGCLINICAL INERTIA

Despite the existence of several provider-focused interventions and evidence for their efficacy,current rates of clinical inertia suggest that they remain inadequate for changing practice behavior.An examination of the objectives, designs, and intervention strategies employed across approachesreveals several limitations. As summarized in Table 1, with the exception of some multifacetedinterventions, most approaches have been designed to address a single provider barrier. Giventhe range of provider factors associated with clinical inertia, those focusing on a single barriermay be less likely to succeed than those that aim to address a range of provider factors becauseof one major flaw: They make the assumption that the targeted barrier is the problem, when, infact, barriers may be multiple and vary across providers. Furthermore, the majority of approachesreviewed involve the passive dissemination of knowledge, which is less effective than more activeapproaches (e.g., practice audits with feedback) that involve provider participation (73).

Most approaches to date have targeted one barrier in particular: provider knowledge or aware-ness of CPGs. Interventions that target behavior change should logically be inspired by behaviorchange theories (BCTs); however, with the exception of incentives [which are inspired by learningtheory and operant conditioning (80)] and possibly some forms of active CME, few approachesappear to be based on BCTs. In fact, a study of 110 accredited CME programs offered to physiciansin Canada reported that 96%, 47%, and 26% used strategies that targeted knowledge, compre-hension, and practice skills, respectively. Finally, few approaches address barriers inherent inimplementing guidelines (e.g., impractical, inconvenient, or biased guidelines) (4, 12).

TOWARD THE USE OF AN EVIDENCE-BASED FRAMEWORKFOR OVERCOMING CLINICAL INERTIA

We propose the use of an evidence-based framework to adequately address clinical inertia that em-phasizes the use of BCT. We also make recommendations for integrating strategies for overcomingpatient-level barriers that promote shared decision making (SDM) and suggest a framework forimproving guideline development and dissemination.

Overcoming Provider Barriers Using Behavior Change Theory

BCT provides a framework for designing interventions that address specific behavior gaps in thecontext of clinical inertia. First, BCT can help us understand what barriers should be targeted.For example, behavioral assessment can be used to identify whether CPGs are not being adoptedfor reasons related to lack of knowledge or awareness, lack of agreement, cognitive biases, lack ofmotivation, lack of self-efficacy, or a combination of these reasons. This information can be usedto group providers in terms of their barriers and offer interventions that target those issues.

Second, BCT offers a framework for overcoming particular barriers. For example, BCT wouldrecommend adopting motivational approaches (e.g., motivational interviewing, inspired by self-determination theory) (81) that are designed to enhance intrinsic motivation and confidence (82)to overcome barriers in motivation or self-efficacy. For a complete list of BCT-inspired approachesthat could be used to overcome specific provider barriers, see Table 2.

Finally, BCT provides a mechanism for understanding why some interventions fail. For ex-ample, although some audit and feedback approaches have been successful, others have actu-ally decreased physician compliance with CPGs. This may be explained by learning theory,which posits that receiving negative feedback about poor performance may be experienced

274 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Tab

le2

Pro

vide

rin

terv

enti

ons

toov

erco

me

clin

ical

iner

tia

Pro

vide

rba

rrie

rIn

terv

enti

onty

peB

ehav

ior

chan

geth

eory

Defi

niti

onSt

rate

gies

Lac

kof

know

ledg

ean

daw

aren

ess

Edu

catio

nN

AT

hepr

oces

sof

lear

ning

via

the

acqu

isiti

onof

know

ledg

eP

rint

edm

ater

ials

,lec

ture

s,co

nfer

ence

s,ac

adem

icde

taili

ng,t

heIn

tern

et,a

ndw

ebin

ars

Lac

kof

agre

emen

tA

ttitu

deor

beha

vior

chan

geC

ogni

tive

beha

vior

alth

eory

(108

)B

ehav

ior

isth

ere

sult

ofou

rin

terp

reta

tions

(tho

ught

s)of

our

envi

ronm

ent(

exte

rnal

stim

uli).

Cog

nitiv

ere

stru

ctur

ing

Hea

lthbe

liefm

odel

(109

)B

ehav

ior

chan

geis

influ

ence

dby

perc

eive

dsu

scep

tibili

tyto

apr

oble

m,s

erio

usne

ss,b

enefi

tsof

actio

n,an

dba

rrie

rs.

Cog

nitiv

ebi

ases

Att

itude

orbe

havi

orch

ange

Cog

nitiv

ebe

havi

oral

theo

ry(1

08)

Cog

nitiv

ere

stru

ctur

ing

Hea

lthbe

liefm

odel

(109

)

Lac

kof

mot

ivat

ion

Att

itude

orbe

havi

orch

ange

Self-

dete

rmin

atio

nth

eory

(81)

Beh

avio

ris

dete

rmin

edby

the

degr

eeto

whi

chit

isdr

iven

auto

nom

ousl

yan

dco

nsis

tent

with

anin

divi

dual

’sgo

als

and

valu

es.

Mot

ivat

iona

lint

ervi

ewin

g(6

9)

Tra

nsth

eore

tical

mod

el(1

10)

Lev

elof

read

ines

sto

chan

gede

term

ines

beha

vior

chan

ge.

We

mov

eth

roug

hfiv

est

ages

ofch

ange

:pre

cont

empl

atio

n,co

ntem

plat

ion,

prep

arat

ion,

actio

n,an

dm

aint

enan

ce,t

hela

tter

thre

eof

whi

chin

dica

tere

adin

ess.

Mot

ivat

iona

lint

ervi

ewin

g(6

9)

(Con

tinue

d)

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 275

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

Tab

le2

(Con

tinu

ed)

Pro

vide

rba

rrie

rIn

terv

enti

onty

peB

ehav

ior

chan

geth

eory

Defi

niti

onSt

rate

gies

The

ory

ofpl

anne

dbe

havi

or(1

11)

Inte

ntio

nis

influ

ence

dby

attit

ude

tow

ard

the

beha

vior

,su

bjec

tive

norm

s,an

dpe

rcei

ved

beha

vior

alco

ntro

l.

Mot

ivat

iona

lint

ervi

ewin

g(6

9)

Reg

ulat

ory

focu

sth

eory

(112

)B

ehav

ior

isde

term

ined

fund

amen

tally

byth

ede

sire

topu

rsue

plea

sure

(pos

itive

outc

omes

)and

avoi

dpa

in(n

egat

ive

outc

omes

)

Per

sona

llyre

leva

ntin

cent

ives

Soci

alco

gniti

veth

eory

(70)

Beh

avio

ris

influ

ence

dby

mod

elin

got

hers

we

iden

tify

with

,pos

itive

outc

ome

expe

ctan

cies

,and

confi

denc

e(s

elf-

effic

acy)

inou

rab

ility

tosu

cces

sful

lyen

gage

ina

beha

vior

.

Mot

ivat

iona

lint

ervi

ewin

g(6

9),

cogn

itive

rest

ruct

urin

g,ex

posu

re(b

ehav

iora

lex

peri

men

ts),

and

goal

sett

ing

and

prob

lem

solv

ing

Lac

kof

self-

effic

acy

Att

itude

orbe

havi

orch

ange

Cog

nitiv

ebe

havi

oral

ther

apy

(108

)C

ogni

tive

rest

ruct

urin

g

The

ory

ofpl

anne

dbe

havi

or(1

11)

Mot

ivat

iona

lint

ervi

ewin

g(6

9)

Abb

revi

atio

n:N

A,n

otap

plic

able

.

276 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

negatively (as a punishment) and result in reduced motivation and frequency of enacting thetarget behavior. Anticipation of negative feedback may also create anxiety and lead to avoid-ance of participating in such interventions. Similarly, according to self-determination theory,incentive-based interventions would only be expected to work if (a) providers were highly moti-vated by financial rewards, (b) accepting financial rewards did not conflict with other values, and(c) the financial rewards are offered. Furthermore, behavior change strategies that rely on extrin-sic rewards may undermine behavior change for intrinsic reasons (i.e., I want to practice EBMbecause I value excellence, altruism, and accountability) and may not be feasible in the longterm.

Overcoming Patient Barriers by Promoting Shared Decision Making

Two important, modifiable, patient-related factors associated with clinical inertia are treatmentnonadherence and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. One of the most promising methods for im-proving patient adherence (both to therapy and lifestyle recommendations) is adopting an SDMapproach (83). SDM aims to empower patients to assume a central role in decision making abouttheir care and includes the following elements: (a) reciprocal exchange of information betweenthe patient and provider, (b) negotiation of treatment options and outcomes, and (c) reaching con-sensus about the course of action. This approach has succeeded at increasing patient adherenceacross a variety of conditions (84, 85), and although it may appear to undermine the practice ofEBM, we argue that this is not the case. In fact, integrating SDM into EBM may actually en-hance both provider compliance and patient adherence to guideline-recommended therapies byhelping to simultaneously overcome barriers related to provider knowledge and agreement withthe applicability of guidelines, as well as cognitive biases related to overestimates of the quality ofcare.

Overcoming Guideline-Related Barriers via Improved Developmentand Dissemination

Often overlooked are limitations inherent to guidelines themselves. Improving the way in whichwe develop and disseminate guidelines may have a major, positive, and rapid impact on guide-line uptake. Rogers (86) describes guideline characteristics that affect provider adoption andcould be used to guide intervention development and dissemination practices. They include rel-ative advantage (is the new recommendation significantly superior to the previous one?), com-patibility (is the guideline consistent with the provider’s beliefs and values?), complexity (howdifficult is it to understand and implement the guideline?), trialability (can the provider testsome or all of the recommendations with relative ease?), and observability (are there oppor-tunities for the provider to observe the results of guideline implementation among respectedpeers?). One study validated these criteria in 23 trials and reported that trialability, observabil-ity, and low complexity were the three guideline characteristics associated with greater guidelineadoption (87). This knowledge could be used to improve guideline development and dissemi-nation strategies in conjunction with existing frameworks. For example, the Guidelines Inter-national Network, which represents 103 organizations from 47 countries, maintains a databaseof more than 6,100 guidelines and offers a Guideline for Guidelines that includes training ma-terials (88). This group has also made available the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research andEvaluation (AGREE I and II) instruments for guideline evaluation (89). The GuideLine Imple-mentability Appraisal (GLIA) instrument is also available for assessing the quality of guidelineimplementation.

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 277

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Clinical inertia is a major barrier to achieving optimal clinical outcomes among patients with a widerange of chronic diseases. CPGs are not without their limitations, and development and dissemi-nation strategies could be improved by simplifying them and making them more accessible for trialpurposes. In an effort to improve the effectiveness of provider-focused intervention strategies, wepropose using an evidence-based framework that incorporates BCT that identifies what barriersto target and how to target them. The fact that most provider-focused interventions to date havenot been inspired by any evidence-based BCT is a major limitation of current approaches. Adher-ence to CPGs by providers does not guarantee good outcomes. Strategies that engage patients inthe treatment process are also important for overcoming clinical inertia, and we propose adopt-ing an SDM model to optimize both patient and provider adherence to guideline-recommendedtherapies.

SUMMARY POINTS

1. Despite the widespread availability of CPGs and strong evidence supporting the benefitsof their use, provider nonadherence to CPGs is prevalent in chronic diseases such ashypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, with rates that exceed 50%.

2. True clinical inertia occurs when a patient fails to meet clearly defined and measurabletreatment targets and their provider does not intensify treatment in accordance withguideline recommendations despite awareness of the guidelines, belief in their applica-bility, and available resources to do so.

3. Clinical inertia involves a complex interaction between organizational and system factors,patient factors, and provider factors, with their relative contributions at 20%, 30%, and50%, respectively.

4. Provider-focused interventions to change clinical practice behavior have had modestsuccess, but most often target one particular barrier: provider knowledge or awarenessof CPGs.

5. Interventions designed to improve clinical inertia should be grounded in BCT and in-corporate SDM and improved guideline development and dissemination.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings thatmight be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Kim L. Lavoie receives salary support in the form of investigator awards from the CanadianInstitutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Fonds de la recherche du Quebec – Sante (FRQS).Joshua A. Rash is supported by trainee awards from Alberta Innovates Health Research (AIHS)and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Tavis S. Campbell receives support inthe form of investigator awards from CIHR.

278 Lavoie · Rash · Campbell

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

LITERATURE CITED

1. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. 1996. Evidence based medicine:what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 312:71–72

2. Rosenberg W, Donald A. 1995. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ310:1122–26

3. Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, eds. 2011. Clinical Practice GuidelinesWe Can Trust. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press

4. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, et al. 1999. Why don’t physicians followclinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 282:1458–65

5. Carlhed R, Bojestig M, Wallentin L, Lindstrom G, Peterson A, et al. 2006. Improved adherence toSwedish national guidelines for acute myocardial infarction: the Quality Improvement in CoronaryCare (QUICC) study. Am. Heart J. 152:1175–81

6. Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. 1993. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review ofrigorous evaluations. Lancet 342:1317–22

7. Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. 2009. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines onquality of care: a systematic review. Qual. Saf. Health Care 18:385–92

8. Sager HB, Linsel-Nitschke P, Mayer B, Lieb W, Franzel B, et al. 2010. Physicians’ perception ofguideline-recommended low-density lipoprotein target values: characteristics of misclassified patients.Eur. Heart J. 31:1266–73

9. Balder JW, Scholtens S, de Vries JK, van Schie LM, Boekholdt SM, et al. 2015. Adherence to guidelinesto prevent cardiovascular diseases: the LifeLines cohort study. Neth. J. Med. 73:316–23

10. McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, et al. 2003. The quality of health care delivered toadults in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:2635–45

11. O’Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Johnson PE, Rush WA, Biltz G. 2005. Clinical inertia and outpatientmedical errors. In Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation, Vol. 2: Concepts and Method-ology, ed. K Henriksen, JB Battles, ES Marks, DI Lewin, pp. 293–308. Rockville, MD: Agency Healthc.Res. Qual.

12. Grahame-Smith D. 1995. Evidence based medicine: Socratic dissent. BMJ 310:1126–2713. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El-Kebbi IM, et al. 2001. Clinical inertia. Ann. Intern.

Med. 135:825–3414. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. 2009. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J. Manag.

Care Pharm. 15:690–9515. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, Coderre K, Nichols J, Belletti DA. 2009. A narrative review of clinical

inertia: focus on hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 3:267–7616. Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. 2006. Therapeutic inertia is

an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension 47:345–51

17. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. 2010. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiplemedications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch. Intern. Med. 170:1648–54

18. Hicks PC, Westfall JM, Van Vorst RF, Bublitz Emsermann C, Dickinson LM, et al. 2006. Action orinaction? Decision making in patients with diabetes and elevated blood pressure in primary care. DiabetesCare 29:2580–85

19. Reach G. 2014. Clinical Inertia: A Critique of Medical Reason. New York: Springer20. Asche C, Bode B, Busk A, Nair S. 2012. The economic and clinical benefits of adequate insulin initiation

and intensification in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 14:47–5721. UK Prospect. Diabetes Study Group. 1998. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or

insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes(UKPDS 33). Lancet 352:837–53

22. Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, Miyata T, Isami S, et al. 1995. Intensive insulin therapy prevents theprogression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependentdiabetes mellitus: a randomized prospective 6-year study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 28:103–17

www.annualreviews.org • Provider Behavior in Disease Management 279

Ann

u. R

ev. P

harm

acol

. Tox

icol

. 201

7.57

:263

-283

. Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

nnua

lrev

iew

s.or

g A

cces

s pr

ovid

ed b

y C

onco

rdia

Uni

vers

ity -

Mon

trea

l on

07/1

0/17

. For

per

sona

l use

onl

y.

PA57CH14-Campbell ARI 26 November 2016 13:14

23. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HAW. 2008. 10-year follow-up of intensiveglucose control in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 359:1577–89

24. Khunti K, Wolden ML, Thorsted BL, Andersen M, Davies MJ. 2013. Clinical inertia in people withtype 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of more than 80,000 people. Diabetes Care 36:3411–17

25. Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A, Zinman B, van Walraven C. 2005. Clinical inertia in response to inadequateglycemic control: Do specialists differ from primary care physicians? Diabetes Care 28:600–6