FERTILIZER SUBSIDIES: A STUDY OF POLICY EFFECTS ON MAIZE IN KENYA.

Transcript of FERTILIZER SUBSIDIES: A STUDY OF POLICY EFFECTS ON MAIZE IN KENYA.

密级: 论文编号:

中国农业科学院

学位论文

肯尼亚玉米化肥补贴政策影响研究

FERTILIZER SUBSIDIES: A STUDY OF POLICY EFFECTS ON

MAIZE IN KENYA.

博士研究生:OCHOLA, R.V.Odhiambo

指 导 教 师:聂风英 研究员

申请学位类别:管理学硕士

专 业:农业资源利用

研 究 方 向:农业政策补贴

培 养 单 位:农业信息研究所

研究生院

2015年5月

Secrecy: No.

Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences

Dissertation

TITLE

FERTILIZER SUBSIDIES: A STUDY OF POLICY EFFECTS ON

MAIZE IN KENYA.

MSc.Candidate:OCHOLA, R.V. Odhiambo

Supervisor: Nie Feng ying

Major: Utilization Sciences of

Agricultural Resources

Specialty: Fertilizer Subsidy Policy

Effects on Maize in Kenya.

Unit: AgriculturalInformation

Institute

May 2015

独创性声明

本人声明所呈交的论文是我个人在导师指导下进行的研究工作及取得的研究成果。尽我所知,

除了文中特别加以标注和致谢的地方外,论文中不包含其他人已经发表或撰写过的研究成果,

也不包含为获得中国农业科学院或其它教育机构的学位或证书而使用过的材料。与我一同工作

的同志对本研究所做的任何贡献均已在论文中作了明确的说明并表示了谢意。

Declaration of Originality

I hereby declare that this thesis was composed and originated entirely by myself under the guidance of

my supervisor. To the best of my knowledge, in addition to information derived from the published and

unpublished works of others that has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given in

the bibliography, the thesis does not contain any other published or unpublished research work by others,

or any materials for another degree or diploma from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and

other educational institutions. The works contributed by other colleagues have been stated and

acknowledged.

关于论文使用授权的声明

本人完全了解中国农业科学院有关保留、使用学位论文的规定,即:中国农业科学院有权保留

送交论文的复印件和磁盘,允许论文被查阅和借阅,可以采用影印、缩印或扫描等复制手段保

存、汇编学位论文。同意中国农业科学院可以用不同方式在不同媒体上发表、传播学位论文的

全部或部分内容。

Authorized Use Agreement

I fully understand the regulations concerning reservation and usage of the thesis in the Chinese

Academy of Agricultural Sciences: CAAS retains the right to keep the copies and disks of the thesis,

allow it to be accessed and borrowed, and compose it by photocopy and scan. CAAS can also

disseminate and publish the full and part of the thesis in different ways and on different media.

学生签名/Student‘s signature: Ochola, Robert Vicky Odhiambo Date: 28th May, 2015

导师签名/Supervisor‘s signature: Prof. Nie Feng ying Date: 28th May, 2015

I

摘 要

“加速农资准入国家计划” (NAAIAP)补贴项目成立于 2006 年,是一种安全保障计划,旨在

解决贫困农户中的粮食不安全和贫困问题。本研究利用截面数据,通过对 200名农民数据进行线

性回归分析,多项类别变量回归分析和 Probit分析而得,数据来自于 2009/2010季度农业的数据,

由此估算 NAAIAP 项目对塔纳河北面的贫困和弱势农户的补贴影响。研究中包含和排除的控制错

误集中在农民实际上已经收到凭证。观察指出,那些具有小学教育水平的老年男性农民,其主要的

收入来源是农业,收入水平达平均 1美元一天。这些农民平均拥有 4英亩土地,其中只有一半是

用于生产,并且没有金融服务,主要归因于缺乏抵押品和低水平的年销售收入,同时存在路边市场

和一般信息不对称。模型结果表明, 各种由使用化肥而得的收入的投资回报对过去的化肥使用,

在合适的季节使用化肥以及公共财政支持,如集团储蓄,具有敏感的残余效应。因此这些发现证

实本研究的重要性,能为政策制定者提供更深的洞察力,并提供有价值关于政策的影响,设计和规

划目标的实现的信息。

关键词:化肥,补贴,小户型农户,政策,商业,加速农资准入国家计划,肯尼亚

II

ABSTRACT

The National Accelerated Agricultural Inputs Access Programme (NAAIAP) a subsidy programme

established in 2006 was envisioned as a safety net programme that would address the problem of food

insecurity and poverty among resource poor farmers. This study using cross-sectional data obtained

from 200 farmers employs Linear Regression, Multinomial Logistic and Probit analysis and data from

the 2009/2010 agricultural season to estimate the subsidy effects of the NAAIAP program on poor and

vulnerable farmers of Tana River Sub-County. To control for errors of inclusion and exclusion the study

focused on those farmers who had actually received vouchers. Observations point to predominantly

aging male farmers with primary level of education and whose main source of income was farming

earning them an average of $1 a day. These Farmers owning on average four(4) acres lack titles to their

pieces of land for which only half was utilized for production, had not accessed financial services

despite such services being within reach a factor that could be attributed to their lack of collateral and

low levels of realized annual incomes from sales though roadside markets and general information

asymmetries. Model results show that returns on investments to various income categories from using

use of fertilizer is sensitive to residual effects of previous fertilizer application, timing or use of fertilizer

during the right season, and communal financial support structures such as group saving. These findings

therefore confirm the importance of this study providing deeper insight to policy makersand providing

valuable information which has implications on policy, design, targeting and programme

implementation.

Key words: Fertilizer, Subsidy, Smallholder farmer, Policy, Commercialization, NAAIAP, Kenya.

III

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 Introduciton ........................................................................................................... 1

1.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1

1.1.1 Background......................................................................................................... 1

1.1.2 Agricultural sector policies................................................................................. 6

1.2 Problem Statement .................................................................................................. 11

1.3 Research Objective ................................................................................................. 12

1.4 Research Question................................................................................................... 12

1.5 Research Hypothesis ............................................................................................... 12

1.6 Justification for the study ........................................................................................ 13

1.7 Conceptual Framework ........................................................................................... 14

1.8 Scope of the study ................................................................................................... 16

1.9 Definition of Terms ................................................................................................. 16

1.10 Limitations to the study......................................................................................... 17

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................... 18

2.1 Fertilizer Subsidies and Input Use .......................................................................... 19

2.2 ―Smart‖ Subsidies ................................................................................................... 21

2.2.1 Design of ―Smart‖ Subsidy Programmes ......................................................... 21

2.3 Maize Value Chain and Fertilizer Subsidies ........................................................... 23

Chapter 3 STATUS OF THE FERTILIZER AND MAIZE SECTORS IN KENYA ........... 32

3.1 Status of The Fertilizer Sector In Kenya ................................................................. 32

3.1.1 Fertilizer and Fertilizer subsidy Policy in Kenya ............................................. 33

3.1.2 Major developments in the fertilizer sector ...................................................... 34

3.1.3 Evolution of maize marketing in Kenya ........................................................... 36

3.1.4 Fertilizer demand and supply trends................................................................. 38

3.1.5 Fertilizer production and consumption ............................................................. 39

3.1.6 Drivers of Fertilizer Supply and Demand......................................................... 43

3.1.7 Fertilizer types and cost .................................................................................... 45

IV

3.1.8 Fertilizer subsidies Programs in African Countries .......................................... 46

3.1.9 Smart Subsidies ................................................................................................ 47

3.2. The National Accelerated Agricultural Inputs Access Programme (NAAIAP) ..... 51

3.2.1 Overview Of The Programme .......................................................................... 51

3.2.2 Project Components.......................................................................................... 52

3.3 The Status of The Maize Subsector In Kenya......................................................... 53

3.3.1 Maize production .............................................................................................. 54

3.3.2 Technical efficiency and allocative efficiency.................................................. 57

3.3.3 Maize marketing ............................................................................................... 58

3.3.4 Maize consumption........................................................................................... 60

Chapter 4 DATA ANALYSIS ........................................................................................... 63

4.1 Study Area ............................................................................................................... 63

4.2 Agriculture in Tana River County ........................................................................... 64

4.2.1 Farming Systems in Tana River County. .......................................................... 64

4.2.2 Sample frame .................................................................................................... 64

4.3 Types and Sources of data....................................................................................... 66

4.4 Data analysis ........................................................................................................... 66

4.5 Econometric Model ................................................................................................. 66

4.6 Model 1: Estimating Fertilizer subsidy effects on Household income; The

Multinomial Approach ..................................................................................................... 67

4.6.1 Model 1Results ................................................................................................. 69

4.7 Model 2: Estimating Fertilizer subsidy effects on Commercialization; The Probit

Approach. ......................................................................................................................... 71

4.7.1 Model 2 Results ................................................................................................ 72

4.7.2 Determinants of Commercialization................................................................. 72

4.8 Definition of Variables ............................................................................................ 74

Chapter 5 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ........................................................................ 77

5.1 Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................... 77

5.1.1 Background information ................................................................................... 77

V

Chapter 6 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .................................................. 85

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................... 88

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................................................... 96

VI

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1-1 .Kenya‘s Agriculture growth (real GDP) .......................................................... 1

Figure 1-2 Conceptual Framework of the NAAIAP Programme ..................................... 15

Figure 1-3 Conceptual Framework for the study.............................................................. 16

Figure 3-1 Economic (GDP) and Agricultural (Value Added) growth 1960 - 2014......... 33

Figure 3-2 Price of DAP in Mombasa and Nakuru (Constant 2007 KSh. per 50Kg bag) 38

Figure 3-3 Fertilizer Consumption in Kg/Ha of arable land ............................................ 39

Figure 3-4 Fertilizer ―Double‖Value chain....................................................................... 40

Figure 3-5 Trends in Consumption, Commercial Imports and Donor Imports of

Fertilizers in Kenya 1990/91 - 2010/11 ........................................................................ 41

Figure 3-6 Trends in the consumption of various Fertilizer products. ............................. 42

Figure 3-7 Fertilizer Supply Chains in Kenya. ................................................................. 45

Figure 3-8 World Fertilizer Consumption (Kg/Ha) .......................................................... 46

Figure 3-9 The Concept of Access Gap ............................................................................ 48

Figure 3-10 Price and quantity effects of a subsidy.......................................................... 49

Figure 3-11 Deadweight loss and Inefficiencies of a Subsidy.......................................... 50

Figure 3-12 Cropping zones of Kenya ............................................................................. 54

Figure 3-13 Fertilizer adoption and maize production costs in Kenya. ............................ 58

Figure 3-14 Maize value chain in Kenya.......................................................................... 60

Figure 3-15 Trends in Kenya‘s Maize production and consumption. ............................... 61

Figure 4-1 Location of the Study Area ............................................................................. 63

VII

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1-1 Key Crop Production Statistics .......................................................................... 2

Table1-2 Categories** Of Agricultural Land ('000 Hectares) ............................................ 2

Table 1-3 Gross Marketed Production At Current Prices 2006 - 2012 (Ksh.. Million)...... 3

Table 1-4 Maize Production ('000 Tonnes) And Average Prices (Ksh.. Per 100kg) To

Producers 2006 - 2012. ................................................................................................... 3

Table 1-5 Value Of Agricultural Inputs, 2005 - 2012 (Ksh. '000) ...................................... 5

Table1-6 Transitional Milestones In Agricultural Policy Reforms ..................................... 6

Table 3-1 Evolution Of Maize And Fertilizer Market Policy Reforms Starting In 1988 . 34

Table 3-2 Summary Of Key Policy Issues In The Fertilizer Markets .............................. 37

Table 3-3 Distribution Of Fertilizer Use Consistency By Agro Ecological Zones........... 41

Table 3-4 Fertilizer Usage By Smallholder Farmers ........................................................ 42

Table 3-5 Agricultural Input Indices, 2009 - 2013 ........................................................... 43

Table 3-6 Value Of Purchased Agricultural Inputs, 2009 - 2013 (Ksh.. Millions) ........... 44

Table 3-7 Market Prices For Fertilizer – National Cereals Produce Board ...................... 45

Table 3-8 Government Subsidized Fertilizer Distribution: Oct – Nov. 2012 ................... 47

Table 3-9 Reforms In The Maize Market 1979 to 2012 ................................................... 53

Table 3-10 Variation Of Maize Productivity By Agro-Regional Zone ............................. 55

Table 3-11 Average Maize Production From 2005 - 2009 ............................................... 56

Table 3-12 Maize Production, Consumption And Domestic Values (2004 - 2010) ......... 56

Table 3-13 .8Maize Production, Pricing And Marketing (2009 - 2013)........................... 57

Table 3-14 Sale To Marketing Boards Of Selected Crops, 2009 - 2013 .......................... 58

Table 3-15 Production And Transport Cost Of Maize To Nairobi.................................... 59

Table 3-16 Comparison Of Yields, Costs And Returns For Maize In Kenya And Uganda ..... 59

Table 4-1 Crop Statistics Tana River County.................................................................... 64

Table 4-2 .NAAIAP Inputs Distributed To Farmers In Galole Division .......................... 65

Table 4-3 Sample Villages Selected Through Purposive Sampling ................................. 65

Table 4-4 Number Of Farmers Sampled Per Village ........................................................ 66

VIII

Table 4-5 Multinomial Logit Regression Results For Annual Household Income .......... 69

Table 4-6 Probit Regression Results For Commercialization........................................... 72

Table 4-7 Description Of Variables .................................................................................. 74

Table 5-1 Descriptive Statistics For Farmers Personal Information ................................. 77

Table 5-2 Descriptive Statistics Group Membership And Activity .................................. 78

Table 5-3 Descriptive Statistics Land Ownership And Production .................................. 79

Table 5-4 Descriptive Statistics Type And Access To Financial Service.......................... 81

IX

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

AATF African Agricultural Technology Fund

AFC Agricultural Finance Corporation

AFC Agricultural Finance Corporation

AFRICOG African Center for Open Governance

AGMARK Agricultural Markets Development Trust

AGRA Alliance for a Green Revolution In Africa

ASAL Arid and Semi-Arid Lands

ASALs Arid and Semi-Arid Lands

ASDS Agricultural Sector Development Strategy

C.I.F Cost Insurance and Freight

CAN Calcium Ammonium Nitrate

CSRP/KMDP Cereal Support Programme/Kenya Maize Development Programme

DAP Diammonium Phosphate

DDCs District Development Committees

DFRD District Focus for Rural Development

ECA East and Central Africa

EEC/WB European Economic Commission/World Bank

ERS Economic Recovery Strategy

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FAOSTAT FAO Statistics

FBOs Faith Based Organization

FISP Farm Input Subsidy Programme

FRS Famine Relief Stocks

GBHL Grain Bulk Handlers Limited

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GoK Government of Kenya

HYVs High Yielding Varieties

IADP Integrated Agricultural Development Programme

IFDC International Fertilizer Development Center

IFIs International Financial Institutions

IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute

IMF International Monetary Fund

KEBS Kenya Bureau of Standards

KENFAP Kenya National Federation of Agricultural Producers

X

KFA Kenya Farmers Association

KGGCU Kenya Grain Growers Cooperative Union

Kgs Kilograms

KIPPRA Kenya Institute Of Public Policy Research and Analysis

KNTC Kenya National Trading Corporation

KRDS Kenya Rural Development Strategy

KTDA Kenya Tea Development Authority

MAFAP Monitoring African Food and Agricultural Policies

MAP Monoammonium Phosphate

MOP Muriate of Potash

MT Metric Tonnes

NAAIAP National Accelerated Agricultural Inputs Access Programme

NARC National Rainbow Coalition

NCPB National Cereals and Produce Board

NEP National Extension Programme

NGOs Non-Governmental Organizations

NPK Nitrogen Phosphorus Potasium Fertilizer

NTBs Non-Tariff Barriers

OPV Open Pollinated Variety

PRSP Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

SAPs Structural Adjustment Programs

SGR Strategic Grain Reserves

SRA Strategy for Revitalization of Agriculture

SSA Sub - Saharan Africa

STATA Data Analysis and Statistical Software

T&V Training and Visit

US$ United States Dollar

USAID United States Agency for International Development

VAT Value Added Tax

WFP World Food Programme

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

1

Chapter 1 Introduciton

1.1 INTRODUCTION

“The rest of the world is fed because of the use of good seed and inorganic fertilizer, full stop. This

technology has not been used in most of Africa. The only way you can help farmers get access to it is

give it away free or subsidize it heavily.” Stephen Carr, former World Bank Specialist on Sub-Saharan

African Agriculture, quoted in Dugger, 2007.

1.1.1 Background

1.1.1.1 An overview of the Agriculture sector in Kenya

Kenya‘s economy is dependent on agriculture, which contributes to rural employment, food

production, foreign exchange earnings and rural incomes. The agriculture sector directly accounts for

about 26 per cent of Kenya‘s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 27 percent indirectly through linkages

with manufacturing, distribution and other service related sectors. The sector accounts for 65 percent of

Kenya‘s total exports, 18 percent and 60 percent of formal and total employment respectively (KIPPRA,

2013).

Figure 1-1 .Kenya’s Agriculture growth (real GDP)

Source:www.knbs.or.ke

In 2012 the sector recorded a growth of 3.8 percent compared to a suppressed growth of

1.5percent in 2011 with marketed production rising by 3.9 percent from Ksh. 331.8 billion in 2011 to

Ksh. 344.6 billion, marketed maize production increased by 29.6 percent on account of higher marketed

volumes buoyed by improved prices paid to farmers (Kenya Economic survey 2013, Deloitte, 2013).

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

2

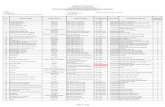

Table 1-1 Key Crop Production Statistics

Commodity 2011 2012 % change

Tea ('000 Tonnes) 377.9 369.4 -2.2

Coffee ('000 Tonnes) 36.3 49.0 35

Fresh Horticultural Produce ('000 Tonnes) 216.2 205.7 -4.9

Maize (Million Bags) 34.4 40.0 16.3

Wheat ('000 Tonnes) 105.9 162.7 53.6

Rice ('000 Tonnes) 80.2 83.6 4.2

Source. Kenya Economic Survey 2013.

Total maize output in Kenya has for a long time been determined by maize yield levels per unit

area and maize statistics have both captured total planted area and productivity as key indicators for

food security in a country whose food security needs are closely tied to the levels of annual maize

production. Kenya being a primarily agriculture based economy performance in the maize subsector

(Table 1-1) has had great bearing on both food security and overall economic growth. Kenya is a

country whose land mass is 80% arid and semi-arid less than 12% of the entire land mass is considered

high potential and suitable for maize production;The(table 1-2)breakdown of the categories of

agricultural land and its spread over 8 provinces (these have now been replaced by counties). Of the

entire total land area only 13% is considered high potential, 6% medium and 81% is low potential land.

Table1-2 Categories** Of Agricultural Land ('000 Hectares)

Province High

potential

Medium

potential

Low

potential

Total Other land Total land

area

Central 909 15 41 965 353 1,318

Coast 373 796 5,663 6,832 1,472 8,304

Eastern 503 2,189 11,453 14,145 1,431 15,576

Nairobi 16 - 38 54 14 68

North –

Eastern

- - 12,690 12,690 - 12,690

Nyanza 1,218 34 - 1,252 - 1,252

Rift Valley 3,025 123 12,220 15,368 1,515 16,883

Western 741 - - 741 82 823

TOTAL 6,785 3,157 42,105 52,047 4,867 56,914

Source: Economic Survey, 2014 ** The three categories are defined as follows *High Potential – annual rainfall of 857.5mm or

more ** Medium Potential – annual rainfall of 735mm-857.5mm and ***Low Potential – annual rainfall of 612.5mm or less.

Increasing maize production in Kenya has been approached both from the farm level and national

level. At the farm level, productivity and maximization of available farm size has been a major focus,

while at the national level overall output and enhancing the productivity potential of fragile land

ecosystems has been top priority. Producing higher yields on available land potential (Table 1-2) has

therefore remained a major focus for research and policy makers in an effort to generate extra

production to feed the nation.

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

3

Table 1-3 Gross Marketed Production At Current Prices 2006 - 2012 (Ksh.. Million)

Crop 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Maize 7,170.20 7,969.20 8,326.60 4,566.40 5,070.30 10,145.30 13,153.00

Rice 1,145.80 1,096.29 889.10 1,309.90 2,642.36 4,111.78 2,323.38

Vegetables 17,822.90 22,354.30 16,128.70 16,253.60 18,646.40 26,251.20 20,225.40

Fruits 1,737.30 1,797.90 2,071.20 2,283.50 2,789.10 3,535.40 4,680.00

Cotton 235.48 340.62 445.76 387.04 567.46 1,430.00 450.00

Pulses 43.48 24.40 33.41 53.93 40.64 69.34 97.46

Tea 45,162.00 43,887.00 55,383.10 64,684.80 87,960.10 100,145.50 100,262.30

TOTAL 75,323.16 79,476.71 85,285.87 91,548.17 119,726.36 147,699.52 143,203.54

Source: Economic Survey 2014

Since Independence the sector has been plagued by various challenges key being low

productivity (Table1-4), lack of or low value addition levels, under – developed and inefficient

markets (inputs and outputs) and inefficient land use patterns especially in densely populated high

potential areas. Because of unpredicted weather and poor infrastructure, producers and consumers

of agricultural products in Kenya face volatile market prices, with periods of surplus production

(Table 1-3) providing a boom for consumers and periods of deficit benefiting a relatively few

number of producers who are net sellers and hurting the majority of consumers (Ariga and Jayne).

Table 1-4 Maize Production ('000 Tonnes) And Average Prices (Ksh.. Per 100kg) To Producers 2006 - 2012.

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Prod. For

sale

470.7 508.8 340.5 191.0 294.6 405.8 387.3

Ave. prices

to producers

1,535.4 1,566.4 2,445.4 2,391.3 1,721.4 2,499.9 3,396.0

Source: Economic survey, 2014

Major constraints to the sector include inadequate budgetary allocation, reduced quality and

quantity of extension services, poor farmer organization and lack of structured trading, low absorption

of modern technology – primarily due to inadequate research – extension – farmer linkages, high cost

and increased adulteration of key inputs, limited capital and access to affordable credit, high post –

harvesting crop losses and heavy livestock losses due to diseases and pests, low and declining soil

fertility, inappropriate legal and regulatory framework, lack of coherent land policy, imposition of

multiple taxation on farm produce, weak surveillance on offshore fishing, inadequate infrastructure

especially poor rural roads, lack of appropriate water harvesting and storage, inadequate storage and

processing, and inadequate markets and marketing infrastructure (USAID 2010). To facilitate higher

maize yields research has focused primarily on identifying short-term productivity needs and long term

sustainable soil potential use,fertilizer use, weed control, modern technological extension, insect and

disease mitigation measures, sustainable and environmentally safe tillage operations are some of the

technologies that have continued to be put forward in managing productivity and total output. This push

for productivity has not been without its fair share of challenges however the overall maize productivity

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

4

and food security situation has continued to rise over the years from a low of 1,143,000MT in 1960 to

2,600,000MT in 2012 (http://www.indexmundi.com/ ). Production of maize is expected to rise even

further with the introduction of key government incentives like fertilizer and seed subsidies (Table 1-5).

The effect of these subsidies is specifically targeted at increasing productivity and production at the

household level.

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

5

Table 1-5 Value Of Agricultural Inputs, 2005 - 2012 (Ksh. '000)

Input 2005 2006 2007 2008 2008 2010 2011 2012

Fertilizers 3,727,000 3,560,000 3,595,000 6,160,000 5,680,000 6,022,000 9,397,400 7,737,600

Insecticides 213,995 246,791 284,712 1,349,165 2,563,584 2,801,664 2,187,015 2,936,510

Fungicides 543,573 626,879 723,202 406,382 772,177 843,889 658,751 884,504

Herbicides 270,846 312,355 360,350 265,299 504,101 550,917 430,053 577,433

Plant hormones 15,586 17,974 20,736 53,227 101,138 110,530 86,281 115,850

Fuel 1,454,045 1,631,729 1,809,413 1,009,869 2,254,294 2,648,100 4,309,360 5,218,743

Power 3,406,955 3,299,865 3,590,587 6,252,131 7,515,706 7,170,200 11,261,440 19,559,057

Seed 2,694,000 2,528,000 2,548,000 3,661,000 3,182,000 4,227,000 3,337,900 3,573,800

Source: Economic Survey, 2014

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

6

Enhancing the performance of smallholders through promotion of intensive farming is critical to

future agricultural growth. This includes the provision of quality and timely support services including

extension to promote good agricultural practices, optimal usage of modern inputs, infrastructural

development to reduce post-harvest losses and overall cost of doing business, and storage facilities. It is

expected however that with productivity improvement comes surplus production and a need to

exchange surplus produce for cash income to support the smallholder basic needs.

Kenya‘s agricultural sector comprises six major sub–sectors which include industrial crops, food

crops, horticulture, livestock, fisheries and forestry. According USAID (2010) basing on 2008 statistics

and production values the sub sectors can be valued as indicated below:

Industrial crops including tea (US$ 738 million); coffee, (US$ 91 million); sugar (US$ 164

million); pyrethrum (US$ 1.2 million); sisal (US$ 19 million); tobacco and coconuts.

Food crops include maize (US$ 951 million) and wheat (US$ 136 million); rice (US$ 16

million); beans (US$ 174 million).

Horticultural products – vegetables, flowers and fruits (US$ 2.4 billion) both domestic and

export.

Livestock – dairy (US$ 1.5 billion) and beef (US$ 1.0 billion)

Fish – both fresh water and marine fish (US$ 120 million)

1.1.2 Agricultural sector policies

Agricultural policy in Kenya can be classified into four distinct phases (Table 1-6) characterized by

significant turning points as discussed below:

Table1-6 Transitional Milestones In Agricultural Policy Reforms

Phase Characterization of role of agriculture Rationale

Post-independence(1960s

– 1980s)

Focus was on agriculture as the main driver of

the country‘s economic growth.

To achieve the post-independence goal

of greater welfare to the citizens.

Agriculture parastatals formed to support credit

and inputs supplies, production and marketing

of major crops and livestock products.

Government was suspicious of private

sector and markets and thus had to

actively intervene to direct the economy

to achieve both productive and welfare

objectives.

Large allocation of government resources and

transfer of land from white settlers to

indigenous, focus on development technologies

appropriate for ASAL.

Improve productivity and bring new

land under production.

Introduction of price controls on agricultural

products, market incentives and annual price

reviews.

Steady increase in incomes of the

farmers vis-à-vis those in

non-agriculture sector.

Control of imports Achieve self-sufficiency in the products

the country could produce.

Liberalization (1980s – Removal of price controls, in products and input Market reforms through the SAPs led

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

7

Phase Characterization of role of agriculture Rationale

1990s) markets, dismantling trade restriction and

transfer of commercial functions from public to

private sector; reduction in government scope in

provision of inputs and credit facilities to

mainly public goods.

by the Bretton Wood Institutions (IMF,

World Bank), external influence.

Emphasis switched to integrated rural

development project taking up poverty

alleviation and food security investment in rural

infrastructure in the rural area.

Decentralize development planning,

coordination, project implementation,

management away from the

headquarters to the district and bring

development closer to the people.

Emphasis on industrial transformation. Shift from reliance on agriculture as the

back bone sector to industrialization in

order to become a new industrialized

country by 2020.

Stakeholder

Participatory

Approaches to Policy

Making (2001 – 2007)

Accelerating policy and Institutional reforms Create opportunities for rural

communities and private sector to

effectively carry out their activities.

Introduction of appropriate technology and

practices.

Improve agriculture sector productivity

and competitiveness.

Crop development sector prioritized as to

address the poor extension service, financial

services, infrastructure, marketing and

distribution through the SRA.

Agriculture as a priority sector of

alleviating poverty in the country.

Source: Jayne

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

8

Before 1964 (The Colonial Period)

Agricultural policy mainly focused on the Colonial agricultural systems and protecting the interests

of the colonial masters with little attention if any paid to African agriculture. Priority was placed on

enhancing and facilitating acquisition of prime land for white settlement and establishing key crops that

would be the reserve of the white colonial masters. European farmers and settlers were supported to

establish and undertake agricultural activities in the agriculturally rich areas of the country with

exclusive land ownership rights. Africans were alienated through control of labour supply through poll

taxation and development of residence labour (squatter system), legal control of production of specific

crops (sisal, coffee, wheat, dairy), Africans were legally restricted from occupying particular areas and

agriculture was then restricted to limited cultivation around restricted residential villages or ―reserves‖

where the colonial masters also determined the type and extent of crop production. Pricing, marketing

and credit policies were used to subsidize settler agricultural production and stifle African agriculture.

These policies generated problems of landlessness and land degradation.

Nzuma, (2013) Citing Brown, (1970) indicates that to effectively implement agricultural policy,

extension and research divisions were established in the then Department of agriculture. The

establishment of these divisions then encouraged the development of sisal, coffee, and pyrethrum

industries for the large scale European farmers. To control production and marketing, several production

and marketing boards/organizations were formed to organize production and marketing and set a basis

for economic growth and achievement of agricultural policy objectives. These boards included; the

Kenya Co-operative Creameries (1931) for dairy products, the Coffee Board (1933) for coffee, and the

Pyrethrum board (1938) to oversee the production and marketing of pyrethrum. Other existing boards

established during this period included the sisal board, the flax board, the passion fruit board, and the

pigindustry board.

In 1950 with the introduction of the Swynnerton plan of 1954 a major shift in the agricultural

policy environment occurred. With emphasis on increased expenditure on extension, research, credit

and market development to support commercial farming, this plan gave life to post – war policies which

saw the implementation of water supplies, soil conservation, farming systems research, livestock

development, and fertilizer and pasture research. However this plan did little to improve African

settlement problems and it also highly discouraged land fragmentation, it also gave co – operative

marketing great importance although it was felt that marketing was too important to be entrusted to

Africans. This eventually resulted in the establishment of marketing boards to control the marketing

system. Some of the boards that were formed in this period include the Coffee Marketing Board in 1946,

the Tea Board in 1951, the maize and produce control board in 1950, the wheat board in 1952, and the

cotton lint and seed marketing board in 1955 (Nzuma, 2013).

1964 to 1980s (The post-independence period)

Immediately after independence and against the backdrop of restrictive regulations in the pre

independence period overall economic and agricultural policy was influenced by the need for

self-determination and rapid economic growth for all citizens. Agricultural policy at this time was

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

9

concern with supporting a smooth transfer of prime land from white settlers to indigenous Kenyans with

help from state – supported agencies in the production and marketing of produce (such as NCPB for

maize) (Ariga and Jayne). It was widely believed that to achieve rapid economic development a lot of

focus needed to be placed on the improvement of the agricultural sector and to enable citizens to freely

engage in farming and take up the opportunities for production that had been left by the colonial masters.

The government therefore emphasized equitable allocation of land, greater access to productive land,

and bringing of new land into agricultural production. Marketing and pricing of agricultural products,

research and development, extension and livestock production became key aspects of the overall

government policy. Focus on research and extension to maintain and increase productivity and

development of livestock through ranching and conservation of natural resources was emphasized

alongside maintenance of rural infrastructure. This periodsaw a rapid establishment of parastatals to

support production and marketing of major crops such as coffee, tea, sisal, pyrethrum, cotton, sugar, rice,

maize, wheat and livestock products. Cooperative societies like Kenya Farmers Association (KFA)

provided inputs to farmers, credit support was provided through Agricultural Finance Corporation

(AFC).

Research and development focused on producing technologies that were relevant to the vast Arid

and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) like small-scale irrigation and the use of water harvesting technologies.

These policies were implemented through programs such as Smallholder Production Service Program

(SPSP) and Integrated Agricultural Development Programme (IADP). The effect of these policies was

that agricultural productivity and cash crop production increased with a resultant growth in GDP of 6%.

The downside however was that this period saw an increase in instances of bad governance, corruption

and rent seeking resulting in indebtedness and poor service delivery to farmers. Marketing monopolies

mushroomed resulting from state owned enterprises having exclusive rights to certain cash crop trade

regulation and pricing.

1980s to 1990s (The liberalization period)

The challenges that emerged from the post-independence period created a need for restructuring

state owned enterprises to provide better services and to eliminate monopolistic tendencies that were

hampering efficient operation of markets. In the 1980s the government therefore introduced market-led

reforms (commonly known as SAPs – Structural Adjustment Programs) partly as a result of the pressure

from external development partners‘ insistence on financial reforms and reduction in state control on

state owned enterprises. Market liberalization involved removal of price controls in product and input

markets, dismantling of trade restrictions and transfer of commercial functions from the public to

private sector. In addition there was marked reduction in government services like extension, marketing,

dipping of cattle, credit and artificial insemination.

A main characteristic of this period was the District Focus for Rural Development (DFRD) a

programme introduced in 1983 to transfer planning and implementation of rural development projects

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

10

from the ministries to the local level with the District taking up the role of ruraldevelopment planning,

project implementation, coordination and management of development resources through its District

Development Committees (DDCs). With the support of development partners districts could also invest

in rural infrastructure like storage facilities, rural access roads and marketing facilities. In 1983 and

1991 saw the approval of the National Extension Programme (NEP) I and II which introduced a new

extension methodology the T & V (Training and Visit).

The inability to compete in a more liberal environment saw the collapse of key state owned

enterprises formed during the post-independence period. DFRD resulted in improvement and access of

services to the rural areas to some extent. However due to the lack of participatory policy and

development planning process, the private sector and the rural clientele could not determine the

direction and priority areas of focus in government planning and project implementation. Capacity

constraints also ensured that the private sector was unable to take up the roles initially carried out by the

state owned enterprises. This had the effect of exposing farmers to market forces and cost-sharing in

services, something that lead to uncertainties and poor performance due to inadequate market

information and investment asymmetries.

1990s to 2000s (The participatory stakeholder period)

The lack of involvement of the private sector in the liberalization and the planning and

implementation of government projects created a need for a platform that would bring together the

government and the private sector. With the experience from the reform period the government also saw

the need to involve the private sector using participatory methodologies so that the private sector could

effectively take up the roles that were given up by the government. To provide a framework for

participatory development the government published the Poverty Reduction strategy Paper (PRSP) in

2001. This was done through a consultative process that brought together the public, private and civil

society groups led by the International Financial Institutions (IFIs). This saw the government

committing to create opportunities for rural community development and the private sector to operate

efficiently and effectively and accelerating policy and institutional reforms particularly on the legislative

and regulatory reforms that created bottlenecks in private sector involvement.

Through its Kenya Rural Development Strategy (KRDS) the government sought to improve

agricultural sector productivity and competitiveness through adoption of appropriate technologies and

practices. The government recognized the need for stakeholder involvement in rural development

through the multi – sector approach. The KRDS brought together Non – Governmental Organizations

(NGOs), private sector, religious groups, civil societies, and other development partners.

The year 2003 saw the installation of a new government, the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC)

and with it saw the renewed spirit for economic recovery through tabling of the Economic Recovery

Strategy (ERS) a precursor of the PRSP. ERS proposed macroeconomic stability, strengthening of

institutions of governance, rehabilitation and expansion of physical infrastructure and investment in

human capital. The productive sectors of agriculture, trade and industry, and tourism were to be the

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

11

prime movers of economic growth (GoK, 2004a). In the Agricultural sector the main policy document

for implementing the ERS was the Strategy for Revitalization of Agriculture (SRA).

Kenya‘s overall guiding policy is the Vision 2030, a national long – term development blue – print

to create a globally competitive and prosperous nation with a high quality of life by 2030, that aims to

transform Kenya into a newly industrializing, middle income country providing a high quality of life to

all its citizens by 2030 in a clean and secure environment (www.vision2030.go.ke). The vision is

anchored on three key pillars (Economic, social and political governance) of which agriculture falls

within the economic pillar. At sector level agricultural development is guided by the Agricultural

Sector Development Strategy – ASDS (2009 – 2020) which came into effect in June 2009. The ASDS

aims to increase agricultural productivity, commercialization and competitiveness of the agricultural

commodities to enable sector contribute to the national goals of food security, increased export for

foreign exchange earnings and employment creation. The ASDS seeks to progressively reduce

unemployment and poverty, and to spur agriculture back to growth trends (ASDS 2010). The vision of

the ASDS is: A food – secure and prosperous nation and its overall goal is to achieve an average growth

rate of 7 percent per year over the next 5 years through its strategicmission of creating an innovative,

commercially oriented and modern agriculture (ASDS, 2010).

The government has also developed specific commodity specific policies to address key challenges

and constraints. These Include Food and Nutrition Policy (2007); National Cassava Industrial Policy

(2007); National Seed Industry Policy; Horticultural Policy (2007); National Agricultural Sector

Extension Policy; National Oil Seeds Industry Development Policy; National Rice Development

Strategy (2008-2018); Sessional Paper on Cereals and Produce (Draft); And Nut Crops Development

Policy among Others (USAID 2010). Other key sector challenges include diminishing agricultural land,

over-reliance on rain fed agriculture, poor cropping choices, poor extension services, and disorganized

markets. Solutions for these challenges can be found in land consolidation, long term land leasing,

making farming commercial, ensuring that technology matches the changing environment, production

of drought tolerant crops, diversifying eating habits; crop insurance; organized markets that will

discover prices more transparently, and improved quality to reduce post-harvest losses.

1.2 Problem Statement

Agriculture which is the backbone of many economies in the world today and especially so in the

Sub – Saharan Africa is characterized by low technological innovation and a resounding little if any,

improvement in yield per unit area of land in the last 40 years. These problems in agricultural

productivity growth have been made even worse by climate change, Agricultural sector policy

implementation, crop pest and diseases, inadequate and inefficient irrigation technologies and

unsustainable farming systems.

These underlying problems have ensured that in addition to numerous biotic and abiotic production

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

12

constraints the productivity of small holder farmers in SSA remains low (AATF, 2010) some of these

productivity constraints could be mitigated using simple technologies like water harvesting and

conservation, supplementary irrigation, plastic mulch and micro – irrigation, land management practices

and policies, revamping agricultural extension, post – harvest loss technologies, labor productivity

enhancing, disease resistant and high yielding maize varieties, dry land technologies, integrated farming

systems that combine fish, livestock and crops and use of organic and inorganic fertilizers to improve

crop yield. Dowardet al., (2007) highlights the factors limiting smallholder agriculture in Malawi as

being high levels of poverty, low productivity, increased vulnerability, seasonality, high dependence on

maize, price fluctuation, land pressure, poor market development and infrastructure, fragility of casual

labor markets and ‗coping strategies‘ of poor people.

Crop production the major driver for rural development in most African countries is closely linked

to land productivity. Soil being the medium for plant growth and stability is critical for crop production

and is a key factor determining land productivity. Studies by ECA (2003) show that soils in SSA are

naturally low in nitrogen and deficient in phosphorus, sulphur, magnesium and zinc. In addition, low

soil depth reduces crop anchorage and ability to extract nutrients and water.

Food security concerns are currently escalating in Sub – Saharan Africa due to poor soil

management practices on the fragile soils (Omotayu, 2009) Global hotspots of soil degradation with

high priority of soil restoration and C sequestration include SSA, Central and South Asia, China, the

Andean Region, the Caribbean, and the acid savannas of South America(Lal,2004). As the world moves

towards a larger population of close to 9 billion people by 2050 the future of tropical agriculture lies in

the reclamation and bringing to better use fragile soils which make up a big part of the soils in Sub

Saharan Africa.

1.3 Research Objective

This study seeks to (1) determine the effects of ―Smart‖ (government) fertilizer subsidy programs

on the annual income of farmers in the maize sector, (2) Effects of determinants/factors that affect

commercialization of smallholder farmers, (3) analyze policy implications of fertilizer subsidy

programmes in light of their effectiveness and justification in smallholder farming.

1.4 Research Question

Does participation in a ―Smart‖ (government) fertilizer subsidy program have any effect on

incomes and market commercialization in the smallholder maize sector? Are the effects substantial

enough to justify the effectiveness of government funded subsidy programs?

1.5 Research Hypothesis

Small-holder farmers are defined as those marginal and sub marginal farm households whose

contribution to the total value of agricultural output is significant in many countries. Many countries are

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

13

currently implementing agricultural and poverty reduction strategies that explicitly support the linkage

to and inclusion of smallholders in markets. It is however not certain the efficacy of such strategies to

the overall welfare of the farmer especially if the programs do not translate into sustainable benefits

through the market led approaches. It is believed that investments in modern technology and entering

new markets that may provide smallholders with better prospects can be extremely difficult due to the

need for economies of scale. This study seeks to prove that public investments in smallholder farmers

through smart subsidies can enable farmers to establish their presence in the market and thus break the

poverty cycle.

1.6 Justification for the study

Approximately 1.5 billion people are engaged in smallholder agriculture across the world. They

include 75% of the world‘s poorest people whose food, income, and livelihood prospects depend on

agriculture. They mainly live in rural communities (Ferris S., Robbins P., Best R., Seville D., Buxton A.,

Shriver J., & Wei E., 2014). Studies from several countries in Africa and Asia show that 50-70% of

smallholders are not transitioning from subsistence to commercial farming (Ferris S., Robbins P., Best

R., Seville D., Buxton A., Shriver J., & Wei E., 2014). Agriculture remains the best opportunity for the

estimated 1.5 to 2 billion people living in smallholder households to escape poverty (Ferris S., Robbins

P., Best R., Seville D., Buxton A., Shriver J., & Wei E., 2014). In developing countries a

significantnumber of the working population residein rural areas and depend on agriculture fortheir

livelihood (Sharma V. P., Jain D., & De S., 2012). Today, agricultural developmentis seen not just as a

vehicle for supportingindustrialization, but also as a modeof inclusive growth, pro-poor

economicdevelopment, food security andenvironmental sustainability [ibid]. However, Farmers face

several marketing constraints these include infrastructure: lack of physical infrastructure reflected in

inaccessible roads, lack of market facilities, power and electricity. Inputs: lack of and/or access to

quality seeds and other inputs including production andtrading capital. Post-harvest losses: High levels

of post-harvest losses. Assembly cost: lack of economies of scale leading to high cost of assembly.

Quality of produce: high levels of crops rejected at both farm level and at company warehouses

because products did not meet market standards. In some cases, farmers were not compensated for

rejected products. Risk: high levels of price and market uncertainty. Market information: unreliable

information on market trends or scheduling of production decisions to meet market needs. Farmers and

other market intermediaries were not aware of important information on prices and marketing, grades

and standard information further up the marketing chain (Freeman H.A, & Silim S.S, undated). The cost

of acquiring information is high, rural assemblers face high opportunity costs, lack of alternative market

outlets and the cost of finding and/negotiating with alternative markets is too high, market

intermediaries misinform farmers, farmers and market intermediaries rely on their own funds to finance

production and trading activities, farmers lose cash due to high cost of enforcing contracts and

production and marketing are characterized by high levels of uncertainty [ibid]. The smallholder

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

14

agriculture sector remains unprofitable and is characterized bylow uptake of improved farm inputs,

weak linksto markets, high transport costs, few farmerorganizations, poor quality control and lackof

information on markets and prices (Chirawa E, & Matita M., 2012). Farmers sell early part of

theirmaize but a greater proportion of maize is soldin the beginning of the marketing season making

households vulnerable to the effects ofchanges in food prices especially where realizedharvests were not

sufficient to meet householdrequirements [ibid]. The income gained from farm production mainly goes

to household consumption since the main target of thehouseholds is ensuring food sufficiency and

security (Balcha Y., 2013). Studies show that income growth generated by agriculture is up to four times

more effective in reducing poverty than growth in other sectors (Ferris S., Robbins P., Best R., Seville

D., Buxton A., Shriver J., & Wei E., 2014).Moving from push (selling what you grow) to pull (selling

what the consumer demands) however requires significant supply chain coordination [ibid].Statistically,

50% of smallholders will not be able to link to a commercial market [ibid]. Therefore, it is important to

keep in mind that the challenge is not merely of creating linkages to lucrative markets, but also of

adequately assessing smallholder conditions, including their market options and methods of optimizing

their market performance—all while ensuring thatthat these options are manageable for the

smallholders[ibid]. According to analysis from several market-focused teams, most smallholder farmers

in areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa rarely have enough surpluses to sell in the marketplace because of

limited land size and poor access to technologies that can improve productivity [ibid].

Use of modern technology is seen as the key to achieving the ―African Green Revolution‖ dream

for the continent. With the key to food security being in the hands of smallholder farmers, use of

modern technology has to be affordable to the majority who remain poor and vulnerable to changes in

the output and input markets. Governments in Africa have been implementing Farm Input Subsidy

Programmes (FISP) on and off from the early 1980s with mixed results in various countries. The case of

Malawi is cited as one of the most successful case studies of the use of ―smart‖ subsidies for increased

productivity and production. Malawi has however met certain challenges in its implementation that call

for closer analysis and understanding, key question being the sustainability of FISP programs and

linking farmers to more sustainable support systems after achieving increased production. This study

therefore seeks to examine the effects of ―smart‖ fertilizersubsidies and their effects on the farmer and

their relationship with the output market and whether these subsidies can create a sustainable

environment for smallholder farmers to thrive.

1.7 Conceptual Framework

The relational and causal aspects of the study will be based on the assumption that fertilizer

subsidies are a significant reduction in the production costs of a farm and that they also enhance a

farmers decision to produce a surplus for consumption and marketing.

Households are assumed to maximize utility with respect to consumption ( ),

production ( ), input use ( ), sales ( ), and purchase ( ) of each good i=1,2…N. Goods

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

15

consumed include self-produced agricultural goods, market commodities and leisure goods. Agricultural

products ( ) use labor and other variable inputs and land ( ). Stands for market price, is

the endowment of good i, represents exogenous transfers and other incomes and and

correspond to household consumption and production characteristics respectively.

The cash constraint states that all purchases of the household must be

less than or equal to sales and other exogenous income ( ) such as remittances. The resource balance

equation states that the consumed and sold quantity cannot exceed

production, endowment and purchased quantity of each good i. In the case of inputs , the resource

balance states that sales, input use and consumption cannot exceed endowment and purchase quantity of

each input i. corresponds to the production function that relates all inputs and outputs.

Fertilizer subsidies affect the farmer‘s expenditure on inputs the study thus seeks to isolate the

effect of fertilizer subsidies on the cost of inputs and the resultant advantages it offers to the farmer in

terms of higher productivity, reduced operational costs and market participation in the maize value chain

This relational concept can best be illustrated by the framework below. This framework is the

authors own development.

Figure 1-2 Conceptual Framework of the NAAIAP Programme

Legend Voucher Redemption

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

16

Figure 1-3 Conceptual Framework for the study

1.8 Scope of the study

This study is based in Tana River County, Tana River district and it focuses on the maize farmers

who have received subsidy support in the NAAIAP programme. The study seeks to examine the

NAAIAP programme with the view of understanding its effects on the smallholder farmer and its

overall effects on the maize market.

1.9 Definition of Terms

“Smart” Subsidy

A subsidy is a form of assistance provided by the government to a subset of the public that lowers

the cost of producing a good or the price that a consumer pays for a good. Federal Reserve Bank of

Boston (2011). Minde and Ndlovu (2007b) describe "smart" subsidies as those involving; Specific

targeting to farmers who would not otherwise use purchased inputs (or to areas where added fertilizer

can contribute most to yield improvement); Measureable impacts, Achievable goals, Result oriented,

Timely duration of implementation i.e. being time-bound or having a feasible exit strategy.

Smallholder farmers

Small-holder farmers are defined as those marginal and sub marginal farm households that own

or/and cultivate less than 2.0 hectare of land, they constitute about 78 per cent of the country‘s farmers.

These small holders owned only 33 percent of the total cultivated land; their contribution to national

grain production was nonetheless 41percent. In addition their contribution to household food security

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 1

17

and poverty alleviation is disproportionately high and is increasing. Moreover, as the national

population increases, so does the number of small holdings Singh et al.,(2002).

1.10 Limitations to the study

The NAAIAP programme is implemented in 104 districts across the country. This study focuses

only on one of the NAAIAP Counties and is further narrowed down to three sites (villages) within the

county. The study was also not able to exhaustively cover all the farmers who had benefited from this

programme due to limited time and resources.

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 2

18

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Farmers in developing countries generally face bigger risk than their counterparts in the

industrialized countries. Small holders, because of their low resource endowment, tend to be highly

vulnerable to production risks due to natural conditions and climatic shocks, as well as to the marketing

risks due to price fluctuation, opportunistic buying behavior etc. Bijman et al.,(2007). In order to better

understand what makes smallholder farmers "small" it is useful to consider the lens of poverty as the

key attribute of smallholder production. In turn, poverty can be defined as asset scarcity, in all of its

dimensions, including natural, physical, financial, human and social. In Kenya, for example, only 4% of

poor have access to credit through banks and another 3% through cooperatives Badiane et al., (1997).

Small-holder farmers are defined as those marginal and sub marginal farm households that own or/and

cultivate less than 2.0 hectare of land, they constitute about 78 per cent of the country‘s farmers. These

small holders ownonly 33 percent of the total cultivated land; their contribution to national grain

production was nonetheless 41per cent. In addition their contribution to household food security and

poverty alleviation is disproportionately high and is increasing. Moreover, as the national population

increases, so does the number of small holdings Singh et al.,(2002). Smallholder contribution to the

total value of agricultural output is significant in many countries of Asia. Small farmers are

characterized by smaller application of capital but higher use of labor and other family owned inputs,

and a generally higher index of cropping intensity and diversification Thapa G, (2010). Small holder

families constitute more than half of the national population [..] these small holder families nonetheless

constitute more than half of the nation‘s totals of hungry and poor Singh et al.,(2002). Despite their

constrained resources and their greater vulnerability to diverse happenings, the smallholding farmers

use farm inputs to a proportionately greater extent than the large holding farmers Singh et al.,(2002).

Smallholder farming is important in terms of poverty reduction, food security and wider rural

economic development in developing countries. Their importance derives from their prevalence, their

role in agricultural and economic development and the concentration of poverty in rural areas. Most

smallholders are vulnerable to economic and climatic shocks and spread their risk by diversifying their

sources of livelihood, often including significant off-farm income generating activities. Investments in

alternative crops and entering new markets that may provide them with better prospects can be

extremely difficult due to the need for economies of scale. Many countries have agricultural and poverty

reduction strategies that explicitly support the inclusion of smallholders in markets KENFAP, (2011).

The agriculture sector contributes 26% directly to gross domestic product (GDP) and 27% indirectly

through linkages with service and manufacturing sectors. The sector contributes 65% of export earnings

in the country. The smallholders' farmers in Kenya account for 75% of the agricultural output and 70%

of marketed agricultural produce. Lack of finance or appropriately packaged financial services pose

great challenge to smallholder agricultural productivity in Kenya [making] it difficult for farmers to

procure inputs needed to increase farm productivity KENFAP, (2011).Little progress can probably be

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 2

19

achieved in small holder farming in Africa without addressing the problems associated with soil and

land degradation. About 55% of Africa‘s land area is unsuitable for agriculture. Only 11% of the

continent, spread over many countries, has high quality soil that can be effectively managed to sustain

more than double its current population. Most of the remaining arable land is of medium or low

potential with at least one major constraint for agriculture. This land is at high risk of degradation under

low input system Jama et al., (2008).

2.1 Fertilizer Subsidies and Input Use

Fertilizer contributes to increase crop production in several ways. First, by replenishing nutrients [..]

Second, fertilizer enables adoption of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) [..] Third, in the nutrient-poor

soils of the tropics, fertilizer use can increase both crop yields and biomass (IFPRI). Studying the logic

of the food tightrope problem leads to the identification of the following approaches in dealing with it -

reducing farmers input costs through input subsidies. In the short run, however, the food price tightrope

can be a major constraint to development in poor rural economies. Governments have tried to address

this through different combinations of input subsidies, output price subsidies for farmers and for

consumers, and social protection to raise the incomes of the poor Dorward et al.,. With the partial or

complete removal of explicit subsidies to smallholders, hybrid maize seed purchases and fertilizer use

declined in the early 1990s in this region and population growth has outpaced grain production growth

in most of eastern and southern Africa Eleni. G. (2009). The use of inorganic fertilizers is one way to

improve crop yields in developing countries outside those in Africa. The use of fertilizer accounted for a

50-75% increase in crop yields from the mid - 1960. Unfortunately, in Africa only a small proportion of

farmers use fertilizers and the amounts used are often inadequate. On average each hectare receives less

than 9kg of nitrogen and 6kg of phosphorus. Typical crop requirements per hectare are at least 60kg of

nitrogen and 30kg of phosphorus. Chemical fertilizer use per hectare of farmland in Africa is about 10%

of the world‘s average, by far the lowest. Fertilizer use is low largely because of its high cost and it

contributes significantly to the unprofitable nature of smallholder farming that is often seen in much of

Africa. Few subsistence farmers can afford to use fertilizers, which in many parts of Africa can cost

nearly four times as much as they do in North America or Europe Jama B. and Pizarro G. (2008). SSA

displays a combination of high soil nutrient deficits and very low fertilizer use (3% globally; 7kg/ha

compared to 150kg/ha in Asia) that comes from a set of failures on input and output markets. On the

demand side, poor price incentives, high seasonal and variable production due to increasing rainfall

variability, lack of liquidity, credit or insurance and lack of knowledge about fertilizer undermine

farmers capacity to adopt the technology or to reap the benefits of its use[..]on the supply side. They

have also had negative impacts on the development of the private sector and on competition, when

distribution schemes and procurement procedure did not encourage them; they have become highly

politicized, too costly and as such unsustainable in the long run. Druilhe Z et al., (2012). Since 1980,

fertilizer consumption in Africa has increased only 0.64%, even though the population grew by 75%.

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 2

20

Because of low use of inputs, yield increase with improved crop varieties is estimated at 88% in Asia

but only 28% in Africa. Jama B. and Pizarro G. (2008).It is worth mentioning that African smallholder

farmers use too little fertilizer because they lack information on how to use fertilizer effectively and

profitably, because they are risk averse in the face of uncertain rainfall, or because they lack the cash to

pay for it because of low income and poorly functioning credit markets Minot N. et al., (2009).

The causes [of low fertilizer use] range from lack of credit, long distance between farmers and the

nearest fertilizer retailer, weak market infrastructure, and lack of government support Ariga et al., Duflo

et al., (2009) in a study on nudging farmers to use fertilizers in Kenya found out that small time-limited

reductions in the cost of purchasing fertilizer at the time of harvest induce substantial increases in

fertilizer use, as much as considerable larger price cuts later in the season. Gurara and Oslami (2012) In

a similar study in Malawi found that in the absence of the fertilizer input subsidy program, fertilizer

intake is expected to fall significantly. A study by Holden and Lunduka (2010) based on household

survey data shows that only about 20% of households are willing to buy a full package at the market

price (Mk 9000) in June -July 2009 while close to 90% are willing to buy it at subsidized price (Mk

1000).Many farmers in Kenya do not use fertilizer (95%), citing lack of financing as a constraint;

however with government and NGO projects, fertilizer use is seen to be increasing steadily Awuor, T.M.

(2003).The poverty and human development report of 2007(R&AWG (2007)) showed that 87% of

Tanzanian farmers interviewed by the research and analysis group [failed to use fertilizers] due to the

high costs of agricultural inputs and services Msuya E.E. et al., (2008). Widespread use of fertilizer on

maize by smallholder farmers is constrained by problems of profitability and affordability Dorward and

Chirwa(2011). Jayne et al., (2003) also found out that there are opportunities to reduce domestic

marketing costs through [..] reducing port fees, coordinating the timing of fertilizer clearance from the

port with up-country transport, reducing transport cost through the port, rail, and road improvements,

reducing high fuel taxes, and reducing the uncertainty associated with government distribution

programs that impose additional marketing costs on traders. Estimated reductions in farm-gate price of

fertilizer [...] range from 11to 18%.

Studies have found out that the maize price has the expected positive and significant effect on

adoption and intensity of use of fertilizer. A 1% increase in maize price increases the probability of

fertilizer adoption by 5% and fertilizer use among adopters by 1.04%. A.D Alene et al., (2008)

Government‘s policy environment and public investment in support of input market development

[...] have been successful in rationing fertilizer use and productivity of smallholder maize production

Ariga J. et al., (2010). In many countries, the withdrawal of state input delivery systems has led to

reduction in fertilizer use as commercial distribution systems compete with subsidized government

programs Ariga et al.,.

Studies on factors driving the increase in fertilizer use by smallholder farmers in Kenya find out

that liberalization of input and maize markets and public investment in support of smallholder

agriculture, leading to rapid private - sector investment in fertilizer retailing and maize marketing,

which in turn has increased farmers‘ use of fertilizer on maize, geographic differences in

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 2

21

agro-ecological potential are also fundamental factors influencing whether farmers use fertilizer or not.

Fertilizer price levels, household resource endowments, and education also influence producers‘

decisions on fertilizer use Ariga J. et al., (2010), female-headed households used fertilizer more

intensively than male headed households in Tanzania Winter-Nelson And Temu(2005). Modern variety

adoption has a positive and significant impact on the intensity of fertilizer use, variety adopters using

12% more fertilizer per ha than non-adopters. The probability of adoption of fertilizer tends to decrease

with access to land per capita and the intensity of fertilizer use decreases even significantly with land

per capita with a 1% increase in land per capita reducing fertilizer use among adopters by 0.3% .

Distance to the fertilizer market has a negative and significant impact on adoption. Since fertilizer

markets are more distant than output markets, there is considerable potential to increase fertilizer use

through improved input distribution system A.D Aleneet al., (2008)

Fertilizer subsidies can decrease the many risks that resource poor farmers have and therefore can

play an important role in increasing their food production Jama B. and Pizarro G. (2008). Input subsidies

can rapidly address or help with many, but not all of the supply and demand problems. They most

immediately and importantly increase profitability of on-farm use and, if sufficiently large, can bring

down the price sufficiently to also address the affordability problem( Dorward et al.,.)

2.2 “Smart” Subsidies

A subsidy is a form of assistance provided by the government to a subset of the public that lowers

the cost of producing a good or the price that a consumer pays for a good. Federal Reserve Bank of

Boston, (2011). Smart subsidies are mechanisms to provide subsidized goods and services designed

both to promote market development and to enhance the welfare of the poor. Below–market-cost

provision of goods and services, generally by private-sector suppliers, from which the poor in particular

are likely to benefit Minot N. et al., (2009). Minde and Ndlovu (2007b) describe "smart" subsidies as

those involving; Specific targeting to farmers who would not otherwise use purchased inputs (or to areas

where added fertilizer can contribute most to yield improvement); Measureable impacts Achievable

goals Result oriented Timely duration of implementation i.e. being time-bound or having a feasible exit

strategy. Minot N. et al., (2009) proposes that governments can avoid the mistakes of the past by

implementing "smart subsidies" which are [implemented through input vouchers] designed to target the

poor and to support, rather than undercut, the development of private input distribution markets.

2.2.1 Design of “Smart” Subsidy Programmes

Well-designed subsidies have the potential to bring about a more equitable distribution of

economic well-being than that generated by an unfettered free-market economy. Subsidies may

simultaneously generate a more just distribution of economic well-being while also promoting efficient

operation of the market economy. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (2011). A common approach to

designing smart subsidies for fertilizer use involves input vouchers. The idea is simple. Farmers are

中国农业科学院硕士学位论文 Chapter 2

22

given vouchers that they can take to local, often small scale, private input suppliers to acquire fertilizer

(or seed or pesticides). The cost of the fertilizer for the farmer is reduced by the value of the voucher.

The supplier having provided fertilizer to the farmer in exchange for the voucher and any additional

cash cost beyond the value of the voucher, takes the voucher to a bank or other designated agency and is

reimbursed for its value, plus a handling fee Minot N. et al., (2009).Voucher programs provide an

opportunity to train farmers and input suppliers on efficient and profitable fertilizer use. Under this

system, farmers are given vouchers that let them acquire fertilizer cheaper from private input suppliers.