Dynamics of Self-Esteem in “Poor-Me” and “Bad-Me” Paranoia

Transcript of Dynamics of Self-Esteem in “Poor-Me” and “Bad-Me” Paranoia

Dynamics of Self-Esteem in ‘‘Poor-Me’’ and ‘‘Bad-Me’’ ParanoiaAlisa Udachina, PhD,* Filippo Varese, PhD,Þ Margreet Oorschot, MSc,þ Inez Myin-Germeys, PhD,þ

and Richard P. Bentall, PhDÞ

Abstract: The dynamics of self-esteem and paranoia were examined in41 patients with past or current paranoia and 23 controls using questionnairesand the Experience Sampling Method (a structured diary technique). For someanalyses, patients were further divided into three groups: a) individuals whobelieved that persecution is underserved (‘‘poor me’’; PM), b) individuals whobelieved that persecution is justified (‘‘bad me’’; BM), and c) remitted patients.The results revealed that PM and especially BM patients had highly unstablepsychological profiles. Beliefs about deservedness of persecution fluctuatedover 6 days. BM beliefs were associated with low self-esteem and depression.Measured concurrently, paranoia predicted lower self-esteem in the BM patients.Prospectively, paranoia predicted lower subsequent self-esteem in BM patientsbut higher subsequent self-esteem in PM patients. Our results suggest thatparanoia can serve a defensive function in some circumstances. The reasons forinconsistencies in self-esteem research in relation to paranoia are discussed.

Key Words: Schizophrenia, paranoia, deservedness, self-esteem,Experience Sampling Method.

(J Nerv Ment Dis 2012;200: 777Y783)

Paranoid delusions are one of the most common symptoms ofpsychosis and are present in up to 90% of first-episode schizo-

phrenia spectrum patients (Moutoussis et al., 2007). Both emotionaland cognitive processes seem to play an important role in theirgenesis (Bentall et al., 2009). An early psychological model of para-noia argued that paranoid patients are able to counter feelings of lowself-esteem by generating external (other-blaming) explanations fornegative eventsVa bias that exists in psychologically healthy indivi-duals but is exaggerated in people with paranoid delusions (Bentallet al., 1994). However, the validity of this attributional account hasbeen questioned by some studies that have reported a negative asso-ciation between paranoia and self-esteem (e.g., Freeman et al., 1998;Thewissen et al., 2011). The attributional model was later revised tosuggest dynamic and nonlinear relationships between attributionsand self-views (Bentall et al., 2001). This modification allows for eitherlow or normal self-esteem, depending on recent experiences, and pre-dicts highly unstable self-esteem in paranoid patients. In line with thisproposition, two recent studies reported that instability of self-esteemrather than negative self-beliefs per se is characteristic of paranoia(Thewissen et al., 2008, 2007).

Trower and Chadwick (1995) argued that there is not one buttwo distinct types of paranoia: ‘‘poor me’’ (PM) and ‘‘bad me’’ (BM).Although both PM and BM patients believe that they are being per-

secuted, PM individuals blame others for their mistreatment and seethemselves as innocent victims, whereas BM individuals accept theblame for the persecution and see themselves as bad. According to thisview, the defensive paranoid attributional style operates in PM but notin BM patients. Although stability of PM and BM beliefs was initiallyimplied (Trower and Chadwick, 1995), Chadwick et al. (2005) lateraccepted the possibility of change in these beliefs. This account iscompatible with the revised attributional model (Bentall et al., 2001),as both propose that, at least in some circumstances, paranoid beliefsmay protect against low self-esteem.

To date, only a small number of studies have examined per-ceived deservedness of persecution, but available findings havegenerally supported the notion that PM and BM beliefs are associatedwith distinct psychological profiles. Freeman et al. (2001) found thatparanoid individuals who were convinced that harm was deservedwere more depressed and had lower self-esteem than did those whothought their harm was unjustified. Chadwick et al. (2005) found that,in comparison with PM patients, BM patients were more depressedand more anxious and held more negative self-views. Similarly,Morris et al. (2011) found that BM patients reported more shame anddepression than PM patients did; PM patients were also more gran-diose. Only one study to date has examined the development ofperceived deservedness over time (Melo et al., 2006). However, themost interesting observation was that in the course of several weeks,some patients switched between BM and PM beliefs, pointing to thedynamic nature of the psychological processes underlying paranoiddelusions.

Although these findings confirm the importance of distin-guishing between PM and BM paranoia, many issues pertaining todeservedness beliefs remain unresolved. First, although early researchindicates that perceived deservedness may fluctuate over time (Meloet al., 2006), no studies to date have examined its stability in a sys-tematic way. Second, psychological profiles of PM and BM have beeninvestigated using questionnaire designs, but these methods lackecological validity. Third, self-esteem research in relation to paranoiahas largely ignored the proposition that the paranoid process is dy-namic in nature and specifically that paranoid attributions may in-fluence future self-representations, as proposed by Bentall et al.(2001). Finally, no studies have investigated a possibility that therelationship between paranoia and self-esteemmay vary depending onbeliefs about deservedness of persecution.

In our study, in addition to conventional questionnaire mea-sures, we used an Experience Sampling Method (ESM; Hektner et al.,2007; Oorschot et al., 2009), which is ideally suited for addressingthese issues. An array of psychological factors implicated in paranoiawas assessed in a sample comprising PM patients, BM patients, re-mitted patients, and healthy controls. ESM is a structured diary tech-nique that allows the assessment of symptoms, mood, and behavior inthe context of daily life (Palmier-Claus et al., 2010). It has high eco-logical validity as it takes into account a wide range of environmentalfactors influencing behavior. Because the variables are measured re-peatedly and with high frequency, this method allows the systematicexamination of changes invariables of interest over time and permits theestimation of temporal relationships between variables.

On the basis of previous work (Chadwick et al., 2005; Meloet al., 2006), we predicted that BM patients would be more depressed

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012 www.jonmd.com 777

*Clinical Psychology Unit, Department of Psychology, The University of Sheffield,Sheffield, UK; †Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, University ofLiverpool, Liverpool, UK; and ‡Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology,South Limburg, Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON,Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Send reprint requests to Alisa Udachina, PhD, Clinical Psychology Unit,Department of Psychology, The University of Sheffield, S10 2TN, UK. E-mail:[email protected].

Copyright * 2012 by Lippincott Williams & WilkinsISSN: 0022-3018/12/20009Y0777DOI: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318266ba57

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

and would have lower self-esteem than the PM patients would. Be-cause earlier studies also suggest that paranoia is associated with dra-matic fluctuations in self-esteem (Thewissen et al., 2008; Thewissenet al., 2007), we expected that both deservedness beliefs and self-esteem would be highly unstable in acutely paranoid patients.However, we did not make specific predictions about PM and BMgroups, and these analyses were exploratory in nature. Finally, wepredicted that the relationship between paranoia and self-esteemwould vary depending on the participant group. Specifically, weexpected that paranoia would be associated with lower self-esteemin BM patients as beliefs that one is being persecuted and deserves itare bound to damage self-esteem. In the PM group, on the other hand,we expected that paranoia would be associated with higher self-esteem as beliefs that the malevolence of others is undeserved mayalleviate the distress associated with thinking that one is a target.We expected that this PM/BM dissociation would be especiallypronounced when the effect of paranoia on subsequent self-esteemwould be examined, as the attributional model specifies a causal roleof paranoid thinking on beliefs about the self (Bentall et al., 2001).

METHODS

ParticipantsFifty-four patients with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Asso-

ciation [APA], 1994) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, ordelusional disorder with either current paranoid or a history of per-secutory ideation were recruited from local inpatient and outpatientfacilities. Twenty-three healthy controls with no current or past psy-chiatric problems requiring treatment were recruited through a com-

munity panel. Patients’ diagnoses and current or past paranoid statuswere confirmed by clinical staff. Current paranoid status was alsoconfirmed using the persecutory subscale of the Persecution andDeservedness Scale (PaDS; Melo et al., 2006) (91.5).

Of 77 participants who were invited to participate, 9 patientsdid not return the booklets, 3 patients completed fewer than 20 validreports, and 1 patient did not comply with the research protocol. Thefinal study sample comprised 41 patients (11 inpatients and 30 out-patients) and 23 controls.Written informed consent was obtained fromall participants.

For the purpose of some analyses, the patients were divided intothree separate groups according to their PaDS scores at the initialassessment. Those with PaDS persecution scores lower than 1.5 wereconsidered remitted. The remaining patients were divided into PM andBM according to a median split of their PaDS deservedness scores.Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants inthe final sample are summarized in Table 1. The groups were com-parable in age and sex. However, there was a significant differencefor IQ and years of education. Post hoc Bonferroni tests showedthat PM patients had a lower mean IQ than the controls (p G 0.01)and all patient groups had fewer years of education than the controls(p G 0.05).

Measures

Questionnaire MeasuresThe PaDS (Melo et al., 2006) assesses paranoid ideation and

perceived deservedness of persecution. The persecution subscaleincludes 10 statements implying that the individual is an object of

TABLE 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 64)

PM (n = 14) BM (n = 15) Remitted (n = 12) Controls (n = 23) F/W2 p-Value of F/W2Group

Differences

Age, mean (SD), yrs 39.36 (15.37) 39.93 (11.84) 41.67 (12.20) 37.78 (15.21) F3,60 = 0.21 0.89 VSex (female), n 7 6 4 10 W

23 = 0.78 0.85 V

Years of education,mean (SD)

12.00 (1.92) 12.53 (2.00) 12.83 (2.04) 15.04 (2.36) F3,60 = 7.68 G0.001 PM, BM, R G C

IQ, mean (SD) 100.68 (14.30) 107.00 (13.93) 110.80 (12.59) 117.61 (11.12) F3,57 = 5.78 G0.01 PM G CMarital status, n

Married or livingtogether

2 2 0 6 V V V

Widowed 0 1 0 1 V V VDivorced 4 2 3 0 V V VNever married 8 10 9 16 V V V

Work situation, nUnemployed 11 11 10 3 V V VPaidemployment

1 2 1 9 V V V

Studying 1 2 1 8 V V VRetired 1 0 0 3 V V V

PANSS, mean (SD)PANSS-Positive 2.44 (0.82) 2.49 (0.68) 1.59 (0.47) 1.06 (0.12) F3,57 = 27.44 G 0.001 PM, BM 9 R, CPANSS-Negative 2.01 (0.82) 1.96 (0.66) 1.73 (0.90) 1.05 (0.07) F3,57 = 9.58 G0.001 PM, BM, R 9 CPANSS-General 1.96 (0.58) 2.07 (0.43) 1.77 (0.69) 1.11 (0.12) F3,57 = 17.32 G0.001 PM, BM, R 9 C

Medication, nAntipsychotic 13 14 12 V V V VAntidepressant 5 1 2 V V V VMood stabilizing 1 1 3 V V V V

PANSS indicates Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PM, poor me; BM, bad me.

Udachina et al. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012

778 www.jonmd.com * 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

malevolence (e.g., ‘‘There are times when I worry that others might beplotting against me’’) rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0Y4) averaged toyield a persecution score (PaDS-Persecution). Each persecution itemis followed by a deservedness item (e.g., ‘‘Doyou feel like you deserveothers to plot against you?’’ rated on a 5-point Likert scale [0Y4]),which participants are instructed to answer only if they score higherthan 1 on the related persecution item. A total deservedness score(PaDS-Deservedness) was calculated as the mean score on all com-pleted deservedness items. The subscales have excellent reliability(Melo et al., 2006).

The Self-esteem Rating ScaleYShort Form (SERS-SF; Lecomteet al., 2006) is a 20-item self-report measure of self-esteem. Half of theitems assess negative self-esteem (e.g., ‘‘I wish I were someone else’’)and half measure positive self-esteem (e.g., ‘‘I feel that I am a verycompetent person’’), rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1Y7). Cronbachalpha was 0.93 for negative and 0.95 for positive self-esteem.

The Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care (BDI-PC; Becket al., 1997) is a seven-item screening instrument that reflects DSM-IV(APA, 1994) criteria for major depressive disorder. Respondents areasked to describe their mood in the past 2 weeks. Each item is rated on a4-point scale (0Y3). Cronbach alpha was 0.92 in the current sample.

The Quick Test (Ammons and Ammons, 1962) was used toestimate the premorbid intelligence of the participants. The adultversion comprises a list of 50 words presented in a successive order ofincreasing complexity, which have to be matched to pictures.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al.,1987, 1988), administered in the form of a semistructured interview, isa widely used measure of psychopathology in schizophrenia. It hasthree subscales (a Positive Syndrome, a Negative Syndrome, and aGeneral Psychopathology Scale) and has good reliability and validity(Kay et al., 1988).

The ESM is a within-day self-assessment technique (Hektneret al., 2007; Oorschot et al., 2009; Palmier-Claus et al., 2010). Eachparticipant received a digital wristwatch and a set of self-assessmentdiaries for each day. The wristwatch was programmed to emit a signal(beep) at unpredictable times 10 times a day on six consecutive daysfrom 7:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. and participants were asked to completethe diary report immediately after each beep to minimize memorydistortions. The time at which participants indicated they completedeach report was compared with the actual time of the beep. Reportscompleted more than 15 minutes after the beep and participants whocompleted fewer than 20 valid reports were excluded from the anal-yses. The ESM has previously been used with psychotic patients ingeneral (for a review, see Myin-Germeys et al., 2009) and withparanoid patients in particular (Thewissen et al., 2008) and has beenshown to be a feasible, reliable, and valid methodology.

ESM MeasuresAll ESM items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1Y7). ESM

Paranoia was assessed as the mean score on three statements derivedfrom the PaDS-Persecution (‘‘I worry that others are plotting againstme,’’ ‘‘I feel that I can trust no one,’’ and ‘‘I believe that some peoplewant to hurt me deliberately’’; Cronbach > = 0.94). Principal com-ponents analysis (PCA) of the items identified one factor (eigenvalue91) explaining 90% of the variance.

ESM Deservedness was calculated as the mean score on threestatements derived from the PaDS-Deservedness, each associatedwith one of the paranoia items (‘‘Do you feel you deserve others toplot against you?’’ ‘‘Do you feel you deserve to have no one you cantrust?’’ ‘‘Do you feel you deserve to be hurt?’’). For each item, scoreswere recorded only if a score on a related ESM persecution item washigher than 1.

ESM Self-esteem was assessed as the mean score on fourstatements (‘‘I like myself,’’ ‘‘I am a good person,’’ ‘‘I am ashamed ofmyself’’ [reverse scored], ‘‘I am a failure’’ [reverse scored]; Cronbach

> = 0.84). PCA of the items identified one factor (eigenvalue 91)accounting for 67% of the variance.

Depression was defined as a mean score of three statements (‘‘Ifeel sad,’’ ‘‘I feel lonely,’’ ‘‘I feel guilty’’; Cronbach > = 0.82) formingone PCA factor (eigenvalue 91) explaining 73% of the variance.

ProcedureParticipants met a researcher twice, with an interval of 7 to 11

days. At the initial meeting, participants completed the PaDS and theQuick Test and received the diary booklets and a digital watch alongwith the instructions about how to fill in the diaries. At the secondmeeting, participants handed back the diaries, completed the SERS-SF and the BDI-PC, and underwent the PANSS.

Statistical AnalysesTo examine the convergent validity of the questionnaire and

ESM measures of paranoia, deservedness, self-esteem, and depres-sion, we calculated Spearman correlations between these measures.Spearman correlations were also calculated to estimate the relation-ships between perceived deservedness of persecution, paranoia, self-esteem, and depression. For these analyses, we calculated mean scoreson each ESM variable for every participant and analyzed them asparticipant-level variables.

To estimate the validity of patient groups and to examine theirpsychological profiles, we a) assessed group differences on PANSSsubscales and questionnaire ratings using one-way analyses of variancewith post hoc Bonferroni tests and b) estimated group differences onESM measures using multilevel linear regressions. Regressions wereperformed with the categorical variable group (controls, PM, BM, andremitted, with controls as the reference category) as the predictor and theESM variables as the dependent variables in separate models. Multi-level linear modelling techniques are a variant of the more often usedunilevel linear regression analyses and are ideally suited for the analysisof ESM data, in which repeated observations (beep level) are nestedwithin persons (participant level). In ESM data, the observations fromthe same individual are more similar than observations from differentindividuals and the residuals are not independent. Unlike conventionalregression techniques, multilevel regression techniques take this intoaccount (Oorschot et al., 2009).

To investigate group differences in instability of deservednessand self-esteem, we performed multilevel regressions using group asthe predictor and ESM instability of deservedness and ESM instabilityof self-esteem as dependent variables. We defined instability as theaverage absolute difference in ESM scores between two succeedingreports for each individual over 60 reports (indicating themean changefrom moment to moment).

Finally, we investigated the association between self-esteemand paranoia. First, we examined the effect of current ESM paranoiaon current ESM self-esteem in the entire sample. This model wasthen modified by entering group and group� current ESM paranoiainteraction as additional predictors. Second, we examined whethercurrent ESM paranoia predicted ESM self-esteem at the next mo-ment (t + 1) in the entire sample; current ESM self-esteem wasentered as a possible confounder. This model was then modified byentering group and group � current ESM paranoia interaction asadditional predictors.

Main effects and interactions were estimated using Wald test.Multilevel regressions were performed using standardized scores ofESM variables using the XTREG command of Stata 9.0.

RESULTS

CorrelationsStrong associations between questionnaire and averaged ESM

measures of paranoia (rS = 0.82), deservedness (rS = 0.69), self-esteem

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012 Self-Esteem Dynamics in Paranoia

* 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.jonmd.com 779

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

(rS = 0.76 for SERS-SF positive; rS = j0.72 for SERS-SF negative),and depression (rS = 0.70) ( p G 0.001 for all relationships) support theconvergent validity of the two forms of assessment. The belief thatpersecution was deserved was associated with higher paranoia, lowerself-esteem, and more depression; these findings were consistent wheneither questionnaire or ESM measures were used (Table 2), furthersupporting the convergent validity of the two assessment methods.

Group DifferencesMean scores on study variables stratified by group together

with the results of statistical analyses are presented in Table 3 (exceptPANSS shown in Table 1). By design, both PM and BM patients

reported more positive symptoms and higher PaDS persecution thandid remitted patients and controls (all p G 0.01) and BM patientsreported higher PaDS deservedness than did individuals from allother groups (all p G 0.001). All the patient groups showed morenegative symptoms and general psychopathology than the controlsdid (all p G 0.05).

On questionnaire measures, PM and BM patients reportedhigher negative self-esteem, lower positive self-esteem, and moredepression than controls ( p G 0.01). BM patients also showed highernegative self-esteem, lower positive self-esteem, and more depres-sion than remitted patients ( p G 0.05), who in turn reported lowerpositive self-esteem than healthy controls ( p G 0.01). Although the

TABLE 2. Correlations Between Deservedness of Persecution, Paranoia, Self-Esteem, and Depression

Deservedness of Persecution

PaDS-Deservedness (No. of Observations = 43) ESM Deservedness (No. of Observations = 41)

ParanoiaPaDS-Persecution 0.40** 0.52**ESM Paranoia 0.37* 0.49**

Self-esteemSERS-SF Negative Self-esteem 0.42** 0.56**SERS-SF Positive Self-esteem j0.38* j0.51**ESM Self-esteem j0.59** j0.54**

DepressionBDI-PC 0.34* 0.48**ESM Depression 0.46** 0.59**

Spearman rho. For ESM measures separate means were calculated for each participant.PaDS indicates Persecution and Deservedness Scale; ESM, Experience Sampling Method; SERS-SF, Self-esteem Rating ScaleYShort Form; BDI-PC, Beck Depression Inventory for

Primary Care.*p G 0.05.**p G 0.01.

TABLE 3. Mean (SD) Scores for Study Variables (Stratified by Group) and Group Differences

PM(n = 14)

BM(n = 15)

Remitted(n = 12)

Controls(n = 23) F/W2

p-Valueof F/W2 Group Differences

Questionnaire measuresPaDS-Persecution 2.58 (0.56) 2.83 (0.86) 0.78 (0.46) 0.54 (0.51) F3,60 = 61.83 G0.001 PM, BM 9 R, CPaDS-Deservedness 0.31 (0.30) 2.09 (0.82) 0.44 (0.44) 0.74 (0.99) F3,43 = 20 G0.001 BM 9 PM, R, CNo. of Deservedness observations 14 15 9 9SERS-SF Negative Self-esteem 3.82 (1.41) 4.51 (1.39) 2.87 (0.97) 2.28 (0.48) F3,57 = 14.99 G0.001 PM, BM 9 C, BM > RSERS-SF Positive Self-esteem 3.69 (1.25) 3.01 (1.15) 4.29 (1.24) 5.67 (0.61) F3,57 = 22.84 G0.001 PM, BM, R G C, BM G RBDI-PC 1.03 (0.69) 1.40 (0.80) 0.56 (0.53) 0.11 (0.22) F3,59 = 17.19 G0.001 PM, BM 9 C, BM 9 R

ESM measuresESM valid reports 46.73 (6.96) 46.46 (7.68) 46.83 (9.70) 50.42 (5.40) W

23 = 5.99 0.11 V

ESM Paranoia 3.28 (2.31) 3.93 (2.17) 1.20 (0.47) 1.06 (0.18) W23 = 50.84 G0.001 PM, BM 9 R, C

ESM Deservedness 1.34 (0.87) 2.91 (1.54) 1.29 (0.52) 1.28 (0.63) W23 = 30.08 G0.001 BM 9 PM, R, C

No. of Deservedness observations 438 575 118 146ESM Self-Esteem 5.46 (1.35) 3.94 (1.26) 5.79 (0.98) 6.21 (0.69) W

23 = 59.37 G0.001 BM G PM, R, C, PM G C

ESM Depression 2.26 (1.26) 3.62 (1.74) 1.69 (1.11) 1.29 (0.59) W23 = 50.16 G0.001 BM 9 PM, R, C, PM 9 C

InstabilityESM Deservedness Instability 0.31 (0.79) 0.58 (0.75) 0.33 (0.46) 0.10 (0.33) W

23 = 8.68 G0.05 BM 9 PM, C

ESM Self-esteem Instability 0.47 (0.70) 0.62 (0.64) 0.30 (0.35) 0.25 (0.47) W23 = 22.17 G0.001 BM, PM 9 R, C

For ESM measures, separate means were calculated for each participant and subsequently aggregated to obtain group means.ESM indicates Experience SamplingMethod; PaDS, Persecution and Deservedness Scale; PM, poor me; BM, bad me; SERS-SF, Self-esteem Rating ScaleYShort Form; BDI-PC, Beck

Depression Inventory for Primary Care.

Udachina et al. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012

780 www.jonmd.com * 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

mean negative self-esteem score for the BM patients was higherthan that for the PM patients, this difference was not significant( p = 0.58).

On the ESM variables (Table 3), PM and BM patients reportedhigher levels of paranoia than the remitted patients and controls(all p G 0.001). With regard to deservedness of persecution, BMpatients reported higher levels than individuals from all other groups(all p G 0.001). Patterns of group differences for self-esteem anddepression were virtually identical. BM patients reported lowerself-esteem and more depression than participants from all othergroups, including PM patients (all p G 0. 001), whereas PM patientsshowed lower self-esteem and more depression than the controls(all p G 0.05).

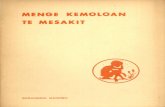

Instability of Deservedness and Self-esteemThe intraindividual ranges of ESM deservedness ratings in

currently paranoid patients identified as BM and PM by the PaDSare depicted in Figure 1. Whereas the median deservedness scoresremained typically close to 1 in the PM group and were typicallyhigher than 1 in the BM group, three PM patients showed mediandeservedness ratings higher than 1 and six BM patients had a mediandeservedness rating of 1. The range of deservedness scores for BMpatients suggests considerable fluctuation in deservedness judgementsover the 6 days of assessment.

Mean scores for instability of deservedness and self-esteem,together with the results of statistical analyses, are presented in

Table 3. BM patients reported greater instability of deservednessthan PM patients and healthy controls (both p G 0.05). However,the analyses for instability of self-esteem showed that the PM andBM groups did not differ on this variable (W21 = 1.20, p = 0.27).Instead, currently paranoid patients in general (PM and BM) showedgreater fluctuations than did either remitted patients or controls(all p G 0.05).

Relationship Between Paranoia and Self-EsteemIn the entire sample, current paranoia was associated with low

self-esteem (A [SE] = j0.22 [0.03], p G 0.001). Analyses with groupand group � current paranoia as additional predictors, however,revealed a significant group � current paranoia interaction: paranoiawas associated with low self-esteem inBMpatients, whereas therewasno association between self-esteem and paranoia in other groups(Table 4).

When the association between current paranoia and subse-quent self-esteem was examined, paranoia predicted lower self-esteem in the whole sample (A [SE] = j0.09 [0.03], p G 0.001).However, controlling for current self-esteem eliminated this effect (A[SE] = j0.01 [0.03], p = 0.78). Analyses with group and group �current paranoia as additional predictors again revealed a significantgroup � current paranoia interaction: current paranoia predictedlower subsequent self-esteem only in BM patients, whereas it pre-dicted higher self-esteem in PM patients, suggestive of a protectivefunction of paranoia in the PM group specifically (Table 4).

DISCUSSIONCurrently paranoid patients showed elevated levels of negative

self-esteem and depression. Consistent with previous research(Chadwick et al., 2005; Freeman et al., 2001;Melo et al., 2006;Morriset al., 2011), low self-esteem and depression were especially stronglyassociated with BM beliefs.

Most patients initially classified as PM and BM according tothe PaDS tended to maintain this position over the study period, al-though a few changed their stance. The most dramatic fluctuations inperceived deservedness were observed among BM patients. Thisobservation is in line with the results of Melo et al. (2006), who foundthat in a sample of acutely paranoid patients, BM beliefs were asso-ciated with particularly dramatic fluctuations in deservedness. Thelatter observation may reflect the fact that compared with PM indi-viduals, BM patients hold profoundly negative views about them-selves and therefore should be more motivated to escape them. Wefound that self-esteem was highly unstable in currently paranoidpatients (PM and BM), also consistent with previous research(Thewissen et al., 2008, 2007). It could be argued that because self-esteem is associated with perceived deservedness, fluctuations inself-esteem should mirror the shifts in deservedness. Thus, greaterfluctuations in self-esteem should be observed in BM patients.However, this was not the case in our study. We found that the dif-ference in self-esteem instability between the PM and BM groupswas nonsignificant, although there remains a possibility that this

TABLE 4. Multilevel Model Estimates B (SE) (Stratified by Group)

PM (n = 14) BM (n = 15) Remitted (n = 12) Controls (n = 23) W23

GroupDifferences

Effect of current paranoia on current self-esteem j0.03 (0.04) j0.38** (0.04) 0.07 (0.14) j0.08 (0.17) 40.68** BM G PM, REffect of current paranoia on subsequent self-esteem 0.09* (0.04) j0.08* (0.04) 0.14 (0.11) 0.09 (0.08) 12.30** BM G PM, R

PM indicates poor me; BM, bad me.* p G 0.05.** p G 0.01.

FIGURE 1. The intraindividual ranges of ESM deservednessscores over 6 days of assessment in patients identified aspoor-me and bad-me. Each column represents a singleparticipant. The thick horizontal line represents the medianESM deservedness score for the participant. The tinted columnrepresents interquartile range, and dots represent outliers.ESM indicates Experience Sampling Method.

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012 Self-Esteem Dynamics in Paranoia

* 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.jonmd.com 781

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

difference failed to reach statistical significance because of thelow numbers of participants in the groups. Overall, these findingssuggest that acute paranoia involves a markedly unstable psycho-logical profile. These results are consistent with the account ofBentall et al. (2001), which predicts highly unstable psychologicalfunctioning in paranoid individuals as they are constantly engagedin self-regulation.

Our results also paint a complex picture of the relationshipbetween paranoia and self-esteem.Measured concurrently in the entiresample, current paranoia was associated with lower self-esteem, asfound in some previous studies (Freeman et al., 1998; Humphreys andBarrowclough, 2006; Thewissen et al., 2010). However, when weexamined the variations in the relationship between concurrentparanoia and self-esteem across different participant groups, we foundthat this relationship was entirely accounted for by the BM patientsand there was no association between concurrent paranoia and self-esteem in the other groups.

Even more interesting results emerged when we investigatedthe temporal relationship between paranoia and self-esteem. Paranoiapredicted lower subsequent self-esteem in the BM patients, but thisrelationship was reversed in the PM patients, in whom paranoiaresulted in higher self-esteem. Consistent with our results for BMpatients, research has found that in nonclinically paranoid individualswho normally hold BM beliefs (Fornells-Ambrojo and Garety, 2005),paranoia is associated with low self-esteem (Combs and Penn, 2004;Martin and Penn, 2001). It is possible that the discrepancy betweenthe concurrent and prospective relationships observed in PM patientsis due to the fact that recruitment of paranoia in response to negativeself-views requires time; this is why the increase in self-esteem isevident only with some delay.

The observation that paranoia had a beneficial effect for self-esteem in PM patients is consistent with Trower and Chadwick’saccount of paranoia that asserts that only PM beliefs defend againstnegative self-evaluations. Our results are also compatible with therevised attributional model that suggests that PM beliefs may serve aprotective function for self-esteem (Bentall et al., 2001). Consistentwith this account, it was found by Melo et al. (2006) that externalattributions for negative events (the proposed mechanism for pro-tecting against negative self-thoughts) are found only in PM patients.

Some limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, wesought to explore heterogeneity in paranoid patients and had a largenumber of participant groups, but the number of participants in eachgroup was limited. Second, our longitudinal assessments were de-manding for the patients, resulting in some dropouts and a relativelyshort assessment period, which precluded us from establishing thestability of deservedness over longer time frames. Melo et al. (2006)observed patients for up to 52 days and found that some patientschanged from PM to BM in that time. Finally, we used self-reportmeasures, which may be open to self-presentation bias.

CONCLUSIONSIn sum, our results confirm that emotional processes and self-

esteem play an important role in paranoid delusions, as found inprevious research (Bentall et al., 2009), but demonstrate the limita-tions of examining the relationship between emotion, cognition, andpsychosis by cross-sectional designs alone. The relevant psycholog-ical processes, and presumably the biological mechanisms that un-derpin them, are dynamic in nature. Our findings show that BM andPM beliefs are associated with distinct psychological profiles, withBM beliefs characterized by more depression and low self-esteem.Although deservedness judgements remain relatively stable in theshort-term, acute paranoia, and especially BM paranoia, is associatedwith a highly unstable psychological presentation. Finally, the rela-

tionship between paranoia and self-esteem varies across subgroupsand time. Measured concurrently, BM but not PM paranoia is asso-ciated with lower self-esteem. Measured prospectively, paranoiapredicts lower self-esteem in individuals with BM beliefs but higherself-esteem in those with PM beliefs. The evidence that PM paranoiaprotects against negative self-views over time is consistent with thehypothesis that attributional mechanisms play an important role inparanoid symptoms (Bentall et al., 2001).

It is likely that previous inconsistencies in psychological re-search in relation to paranoia could be explained by failure to accountfor deservedness of persecution and disregard for the dynamic natureof paranoid process. Future research should address these issues andconcentrate on investigating factors determining perceived deserved-ness of persecution.

DISCLOSURESThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCESAmerican Psychiatric Association (1994)Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders (DSM-IV).Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Organization.

Ammons RB, Ammons CH (1962) The Quick Test (QT)VProvisional manual.Psychol Rep. 11:111Y161.

Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R (1997) Screening for major depression disordersin medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care.Behav Res Ther. 35:785Y791.

Bentall RP, Corcoran R, Howard R Blackwood N & Kinderman P (2001) The self,attributional processes and abnormal beliefs: Towards a model of persecutorydelusions. Behav Res Ther. 32:331Y341.

Bentall RP, Kinderman P, Kaney S (1994) The self, attributional processes andabnormal beliefs: Towards a model of persecutory delusions. Behav Res Ther.32:331Y341.

Bentall RP, Rowse G, Shryane N, Kinderman P, Howard R, Blackwood N, Moore R,Corcoran R (2009) The cognitive and affective structure of paranoid delusions:A transdiagnostic investigation of patients with schizophrenia spectrumdisorders and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 66:236Y247.

Chadwick PD, Trower P, Juusti-Butler T-M, Maguire N (2005) Phenomenologicalevidence for two types of paranoia. Psychopathology. 38:327Y333.

Combs DR, Penn DL (2004) The role of subclinical paranoia on social perceptionand behavior. Schizophr Res. 69:93Y104.

Fornells-Ambrojo M, Garety PA (2005) Bad me paranoia in early psychosis: Arelatively rare phenomenon. Br J Clin Psychol. 44:521Y528.

Freeman D, Garety P, Fowler D, Kuipers E, Dunn G, Bebbington P, Hadley C (1998)The London-East Anglia randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behaviourtherapy for psychosis IV: Self-esteem and persecutory delusions. BrJ ClinPsychol.37:415Y430.

Freeman D, Garety P, Kuipers E (2001) Persecutory delusions: Developing theunderstanding of belief maintenance and emotional distress. Psychol Med.31:1293Y1306.

Hektner JM, Schmidt JA, Csikszentmihalyi M (2007) Experience SamplingMethod. Measuring the quality of everyday life. London: Sage Publications.

Humphreys L, Barrowclough C (2006) Attributional style, defensive functioningand persecutory delusions: Symptom-specific or general coping strategy? Br JClin Psychol. 45:231Y246.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987) The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scalefor schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 13:261Y276.

Kay SR, Opler LA, Lindenmayer JP (1988) Reliability and validity of the Positiveand Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenics. Psychiatr Res. 23:99Y110.

Lecomte T, Corbiere M, Laisne F (2006) Investigating self-esteem in individualswith schizophrenia: Relevance of the Self-esteem Rating ScaleYShort Form.Psychiatr Res. 143:99Y108.

Martin JA, Penn DL (2001) Social cognition and subclinical paranoid ideation. Br JClin Psychol. 40:261Y265.

Melo S, Taylor JL, Bentall RP (2006) ‘Poor me’ versus ‘bad me’ paranoia and theinstability of persecutory ideation. Psychol Psychother. 79:271Y287.

Udachina et al. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012

782 www.jonmd.com * 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Morris E, Milner P, Trower P, Peters E (2011) Clinical presentation and early carerelationships in ‘poor-me’ and ‘bad-me’ paranoia. Br J Clin Psychol. 50:211Y216.

Moutoussis M, Williams J, Dayan P, Bentall RP (2007) Persecutory delusions andthe conditioned avoidance paradigm: towards an integration of the psychologyand biology of paranoia. Cognit Neuropsychiatry. 12:495Y510.

Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, Lataster J, Delespaul P, van Os J (2009)Experience sampling research in psychopathology: opening the black box ofdaily life. Psychol Med. 39:1533Y1547.

Oorschot M, Kwapil T, Delespaul P, Myin-Germeys I (2009) Momentaryassessment research in psychosis. Psychol Assess. 21:498Y505.

Palmier-Claus JE, Myin-Germeys I, Barkus E, Bentley L, Udachina A,Delespaul PA, Lewis SW, Dunn G (2010) Experience sampling research in

individuals with mental illness: Reflections and guidance. Acta PsychiatrScand. 123:12Y20.

Thewissen V, Bentall RP, Lecomte T, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I (2008) Fluctuationsin self-esteem and paranoia in the context of daily life. J Abnorm Psychol.117:143Y153.

Thewissen V, Bentall RP, Oorschot M, Campo JA, van Lierop T, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I (2011) Emotions, self-esteem, and paranoid episodes: An experiencesampling study. Br J Clin Psychol. 50:178Y195.

Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall RP, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, van Os J(2007) Instability in self-esteem and paranoia in a general population sample.Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 42:1Y5.

Trower P, Chadwick PD (1995) Pathways to defence of the self: A theory of twotypes of paranoia. Clin Psychol. 2:263Y278.

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease & Volume 200, Number 9, September 2012 Self-Esteem Dynamics in Paranoia

* 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.jonmd.com 783

Copyright © 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.