D D D D D D D D D D D D D D D D D D - City and County of ...

Danti, M. D. and M. Cifarelli. In Press. “Assyrianizing Contexts at Hasanlu Tepe IVb?: Materiality...

Transcript of Danti, M. D. and M. Cifarelli. In Press. “Assyrianizing Contexts at Hasanlu Tepe IVb?: Materiality...

Assyrianizing Contexts at Hasanlu IVb?: Materiality and Identity in Iron II Northwest

Iran

Michael D. Danti and Megan Cifarelli

In Press

To appear in John D. A. MacGinnis and D. Wicke, eds. The Provincial Archaeology of the

Assyrian Empire. Proceedings of the conference held at the University of Cambridge, McDonald

Institute for Archaeological Research December 13th-15th 2012. (Cambridge: McDonald

Institute for Archaeological Research).

Introduction

In this paper, we briefly survey and reappraise some of the evidence for Neoassyrian

contact at the Iron II (1050–800 BC) settlement of Hasanlu Tepe in the southern Lake

Urmia Basin, located east of Assyria in the western Zagros Mountains of Iran. A

complete survey of the recent revisions to our understanding of Hasanlu is beyond the

scope of the present work, and up-to-date assessments are available in several sources

(Muscarella 2006; Cifarelli 2013; Danti 2011, 2013a, 2013b; Danti and Cifarelli In

Press). Our intention is to highlight a particular pattern educed from the Hasanlu early

Iron Age dataset: potential Assyrian imports and assyrianizing material culture, broadly

construed herein for sake of argument, are concentrated in Hasanlu’s monumental

temples Burned Building II (BBII) and, to a lesser extent, Burned Building IV East

(BBIVE) of Hasanlu’s Lower Court (Figure 1). This pattern is at odds with previous

theories that have viewed assyrica (i.e., Assyrian imports and assyrianizing emulations)

as key mechanisms for the enhancement of the power and authority of Hasanlu’s elites.

Almost immediately after Robert H. Dyson began the first scientific excavations at

Hasanlu Tepe in 1956, scholars began to posit the mechanisms by which assyrica were

transmitted to northwestern Iran and recontextualized, as well as the meanings and

impacts of assyrica among the autochthonous populations. Our ability to interpret this

evidence has been somewhat hindered by several factors. First, during the span of the

Hasanlu Project (1956–1977), knowledge of Urartian material culture and that of the

southern Caucasus and eastern Anatolia more generally was somewhat limited or the

sources were difficult to access. Published comparanda from Assyria, Babylonia, and

Elam were better known, more widely disseminated, and easily accessible, particularly

for western scholars trained and versed in the archaeology of Syria, Mesopotamia, and

Iran. The absence of indigenous writing in northwestern Iran and a lack of archaeology in

the area between Assyria and the southern Lake Urmia Basin made Hasanlu a veritable

protohistoric archipelago of archaeological understanding. Assyrian texts and material

culture provided an important interpretative tool for tackling the recently discovered

culture of Hasanlu, and hence select objects and object classes received preferential

coverage in publication. These specialized analyses led to theorizing without the benefit

of the full explication of the massive dataset — in particular, the full range of contexts

and a diachronic perspective played but small roles in discussions of assyrica vis-à-vis

local identity, agency, and materiality.

Although this region is often referred to as lying at Assyria’s eastern periphery, poorly

known buffer states in the naturally fortified western Zagros, such as the kingdom of

Musasir/Ardini, were Assyria’s immediate neighbors. The recent flurry of archaeological

activity in Iraqi Kurdistan will doubtless help to fill this gap in our knowledge and

enhance our understanding of northwestern Iran. Nevertheless, Hasanlu is unique in

terms of the wealth of evidence for contact with Assyria, Urartu, Babylonia, and Elam —

other excavated sites around the lake such as Kordlar, Geoy, and Haftavan were more

closely tied to the southern Caucasus and eastern Anatolia. At Hasanlu, close contacts

with both northern Mesopotamia and the southern Caucasus can be traced back to at least

the earliest Bronze Age (Hasanlu Period VII) with heightened connections in the Middle

Bronze Age (Hasanlu Period VI). The Late Bronze Age (Hasanlu Period V) is more

enigmatic, but by the Iron I (Hasanlu Period IVc) ties to northern Mesopotamia are again

attested. Hasanlu’s 800 BC destruction level — this date represents a chronological

approximation tied to the pooled mean of short-lived radiocarbon samples from Burned

Building III (Danti 2011) — probably the result of an Urartian attack, provides an

unparalleled source on northwestern Iranian connections to neighboring regions. We

must not lose sight of the fact that the well-preserved settlement that was savagely sacked

and burned— preserving 13 monumental buildings, over 255 victims and enemy

combatants, and thousands of objects — was the product of a long development, a

palimpsest of the Late Bronze and early Iron Age. Hasanlu developed into a typical

northwest Iranian citadel center (characterized by a high, central fortified citadel

surrounded by a Lower Town with low density occupation and cemeteries) no later than

the latter part of the Late Bronze Age. At least five such centers were evenly spaced

across in the southern Lake Urmia Basin (Danti 2013b): only Hasanlu has been

excavated.

As early as 1959, Edith Porada raised the issue of Assyrian influence on Hasanlu

following the remarkable discoveries there in 1958 in the famous Period IVb destruction

level, and in more detail in her 1967 chapter Notes on the Gold Bowl and Silver Beaker

from Hasanlu in Arthur Upham Pope’s monumental A Survey of Persian Art. Porada

suggested that Hasanlu artifacts exhibited a Local Style heavily influenced by Assyrian

contact, as well as other regions. She compared the styles of the Hasanlu Gold Bowl (also

called a beaker) and Silver Beaker and argued that both were the products of a local

tradition. She dated the Gold Bowl to the late 2nd Millennium BC and the Silver Beaker

to the 9th Century BC and noted the latter bore the evidence of influences from Late

Assyrian monumental art (Porada 1967). Subsequently, Irene Winter assessed this Late

Assyrian impact on Hasanlu in greater depth in her seminal chapter Perspectives on the

“Local Style” of Hasanlu IVb (1977). Winter listed many of the likely Assyrian imports

at Hasanlu, key among them Assyrian linear style cylinder seals, frit objects, and ivories,

as well as the far more abundant assyrianizing local imitations in portable art and

architectural features. The following two quotes best capture Winter’s early thinking on

the cultural processes underlying assyrica at Hasanlu,

Despite the large number of Assyrian objects found at the site of Hasanlu

thus far, there is none which directly provides a model for the scenes

found in the local style works . . . on the whole, the clear ties of scenes

relating to Assyrian art in the local style of Hasanlu are not to works in

comparable scale, but rather to the palace reliefs of Assurnasirpal and the

bronze doors from Balawat. The presence of glazed terracotta wall tiles in

Burned Building II and elsewhere at Hasanlu (e.g., HAS. 58-362a–g,

HAS. 59-773, -819; HAS. 60-303, and -513; HAS. 62-163, -446; HAS.

70-360), which are clearly modeled after similar tiles known from the 9th

century Assyrian palaces at Assur and Nimrud, is a further and equally

significant link to Assyrian monumental architecture (1977: 376–77).

… although the Assyrianizing elements that mark the Hasanlu local style

undergo a transfer in context from major to minor scale, reference is

consistently to Assyrian public monuments and royal iconography, and

this focus is reinforced by the use of decorated wall tiles imitating the elite

buildings of the West (1977: 377).

Winter concluded that the Hasanlu local style was an emulation of a selective, narrow

subset of secular Assyrian visual culture, rather than a wholesale imitation,

The residents of Hasanlu do not take supernatural motives from

Assyrian art, although they have ample models (viz. cylinder

seals); they clearly have a system of their own. They take rather

the emblems of authority and power associated with Assyrian royal

monuments (1977: 380).

Winter asserted Hasanlu’s elites conveyed and enhanced their power and authority

through displays of assyrica, and incorporated Assyrian and assyrianizing architectural

forms and elements into buildings to “increase monumentality” and to “make a public

show” (Winter 1977: 380–81). Since Winter’s pivotal work, other scholars have similarly

interpreted Hasanlu’s assyrica as the co-option of Neoassyrian themes and iconography

— particularly as expressed in the monumental narrative art of Assurnasirpal II and

Shalmaneser III — to convey, legitimize, and reinforce elite secular power, authority, and

prestige (Marcus 1989, 1996; Collins 2006).

Somewhat contrary to these assertions, our recent work on Hasanlu IVb demonstrates

that assyrica is surprisingly rare in the elite residences of the citadel and largely absent

from the graves of the Low Mound, that is, in contexts in which one would predict a

heavy emphasis on public displays of secular power and authority. In these contexts, we

see a diverse range of sources and inspirations for elite material culture. Assyrica is

largely concentrated in Hasanlu’s Iron II temples dubbed BBII and BBIVE — not just the

well-known ivories and cylinder seals, but also other categories of material culture of

potential Assyrian origin or inspiration.

By and large, the Iron II/Period IVb destruction deposits in BBII and BBIVE, where

thousands of objects were recovered, constitute temple furnishings and treasuries. Many

other objects were associated with the victims and enemy combatants found in the

destruction level, particularly at the north end of BBII. For the most part, we are able to

isolate the objects worn and used by those who died in BBII, but the incomplete and

error-prone excavation records from several areas make this work a difficult and time-

consuming challenge. These temples of the Lower Court were constructed sometime in

early Period IVc (1250–1050 BC), that is the early Iron I, or possibly as early as the end

of Period V (1450–1250 BC), the later Late Bronze Age (Danti 2013a, 2013b). Dyson

and Voigt have argued that, from its inception, BBII emulated northern Mesopotamian

temples in terms of its architectural plan (Dyson and Voigt 2003). Most significantly,

although little has been published on the subject, the entrances to both BBII and BBIVE

were flanked by aniconic stone stele (Akkadian sikkanu), cultic features well attested in

the archaeological and textual record of Syria, particularly in the Late Bronze Age

(Hutter 1993; Durand 2005). The contents of the storerooms of BBII and BBIVE

represent the culmination of an established practice of storing and displaying treasures in

a cultic (as opposed to a more secular) context. The longevity of this collecting practice at

Hasanlu is demonstrated through the discovery of heirloom objects in these contexts,

such as the 2nd millennium BC mosaic glass vessel discussed by Marcus (1991), as well

as direct parallels between stored objects and goods found in burials in the Low Mound

cemeteries dating back to the Middle Bronze Age (Cifarelli 2013). As the assyrianizing

contexts at Hasanlu appear to be mostly confined to these temples, and not other parts of

the citadel, the Lower Town, or the cemeteries, and the evidence for contacts with

northern Mesopotamia forms a continuum stretching into the 2nd millennium BC, we are

rethinking the associations between Late Assyrian iconography and secular power, as

well as the cultural mechanisms responsible for the transmission and incorporation of

assyrica into Hasanlu society and the development of the Hasanlu Local Style.

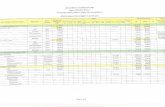

Hasanlu IVb Object Distributions

The rapid and thorough destruction of the Hasanlu IVb citadel sealed building contents,

permitting a detailed discussion of the distribution of object types. To date, much of the

published information on artifact distributions has been anecdotal, weighted toward

exotica, or presented in a piecemeal and cursory fashion. Dyson and other researchers

have preliminarily analyzed some object classes in the important BBI/BBII complex to

determine building functions, especially to delineate religious versus secular spaces, and

patterns in the use of ground floors and second stories, including ornaments (Dyson 1989:

figs. 18a–b), containers (Ibid., figs. 19a–b)), weapons (Ibid., figs. 23a–b), and seals and

sealings (Marcus 1989: figs. 10–11). More comprehensive and in-depth spatial analyses

have also been completed for horse gear in the Iron II citadel (de Schauensee 1989: fig.

4) and, for the entire Iron II settlement, all known ivories (Muscarella 1980: 5) and seals

and sealings (Marcus 1996: figs. 8–14). Much work remains to be done. Here we focus

on those finds that evidence potential connections between Hasanlu and Assyria. The

present work cannot adequately deal with certain larger categories of material culture, in

particular the abundant personal ornament, plaques, and weapons, found in the Terminal

Hasanlu IVb destruction level.

Tile and Wall Knobs

Perhaps the strongest evidence of the emulation of Assyrian monumental architecture at

Hasanlu is the assemblage of glazed terracotta and copper/bronze wall tiles, knob

plaques, and knobs (Winter 1977: 376–77). The choice of such ornamentation has been

assumed to be inspired by Assyrian monumental buildings, and the stylistic attributes of

the tiles themselves (form, color scheme, and decorative motifs), presumably all the

products of local ateliers, cover the Local Style spectrum — from the indigenous to the

highly and demonstrably assyrianizing.

Nearly all of the approximately 67 occurrences were discovered in BBII in dispositions

that indicate many were affixed to walls (Figure 2). Others may have been stored in BBII,

although there is nothing specific to indicate this. While much has been made of this

“Assyrian” feature of the monumental buildings (e.g., Winter 1977; Nunn 1988; Marcus

1989 and 1996), as early as 1965 Porada pointed out the relationship between the

Hasanlu glazed wall tiles and knob plaques with those from the Elamite sites of Choga

Zanbil and Tal-i Malyan (Porada 1965: 123–4). The Elamite examples were stored in

temple storerooms and decorated temples and ziggurat platforms rather than palaces

(Basello 2012; Tourtet 2011). Many Hasanlu examples are assyrianizing; however, they

manifest an architectural practice that is not, perforce, purely Assyrian in inspiration.

Furthermore, their use in temple decoration complicates the interpretation of their role as

signals of secular power and authority and, tentatively, would be more likely tied to the

prestige and character of the cult(s) of the deity (deities) housed by these temples.

Ivories

At first glance, ivories exhibit a distribution pattern similar to that of the aforementioned

wall ornaments (Figure 3). Unlike the wall ornamentation, most of which was in use at

the time of Hasanlu’s destruction, the bulk of all other Hasanlu assyrica lay within the

collapse layers of the upper stories of BBII, a large part of which was dedicated to

storage, an interpretation reinforced by the co-occurrence of a number of sealings

produced with Local Style seals (Marcus 1989, 1996). By far, most of the ivory objects

are carved in the Local Style, which in many aspects emulate Assyrian monumental art

(Winter 1977; Muscarella 1980). Muscarella has identified a small percentage as

“Assyrian Style” (Muscarella 1980: 148), at least one of which (HAS64-1047; MMA

65.163.2a, b; 3a, -c from BBII) is of exceptional quality and has been dated to the late 9th

or early 8th century BC (Muscarella 1980: 148–9, no. 280; Collins 2006: 27). “North

Syrian” style ivories, often understood to have come into Hasanlu via Assyrian

connections, are present in greater numbers on Hasanlu’s citadel (Figure 3). Georgina

Herrmann has recently revived Helmuth Kyrieleis’ hypothesis that a group of

assyrianizing ivories from Nimrud, identified by Barnett as “North Syrian” style, were in

fact made in Urartu (Herrmann 2012). It would be interesting indeed to examine the

“North Syrian” ivories at Hasanlu to determine their relationship to Urartian ivory and

wood carving styles and techniques, but that remains outside the scope of this study. In

terms of the Assyrian style ivories, the notion that they arrived at Hasanlu as part of a

“royal gift” from an Assyrian king (Winter 1977; Muscarella 1980; Collins 2006) is

rather difficult to support, given the scarcity of other evidence of Assyrian royal interest

in the settlement.

Seals and Sealings

In her landmark study of the Hasanlu seals and sealings, Michelle Marcus distinguishes

between Central Assyrian Style, Provincial Assyrian Style, and Local Style seals, among

others (Marcus 1996). There is no evidence for the practice of sealing at Hasanlu before

Period IVb, although cylinder seals occur as personal ornaments in burials of earlier

periods (Marcus 1994, 1996; Cifarelli 2013). A total of 31clay sealings were excavated

from citadel destruction contexts, many of which were found amid the second floor

deposits of BBII and BBV. All were created with Local Style seals. A total of 52 cylinder

seals were found in Hasanlu IVb deposits along with 19 stamp seals. Of the cylinder

seals, Marcus classifies 6 (11.50% of cylinder seals) as Central Assyrian Style and 15 as

Provincial Assyrian Style (28.80% of cylinder seals). Assyrian and assyrianizing seals

compose a significant percentage of the cylinder seal assemblage, but were not seemingly

used for sealing — all but one were found in the Terminal Hasanlu IVB destruction

deposit. Marcus concludes these cylinder seals were worn rather than used for sealing,

and further argues that Assyrian Style seals were symbols of elite status (Marcus 1996:

49–50). The question remains: by whom? Assyrian Style seals seem to have occasionally

functioned as pin ornaments and as parts of bead necklaces, but nearly none were found

in use-related contexts. Firstly, none come from Hasanlu Iron II burials. All the Central

Assyrian Style seals are from storage contexts (evaluated on the basis of associated finds

occurring in high numbers, matrix, superposition, and provenience) in the Citadel’s

Lower Court complex, in:

1) a BBII Room 5 cylinder seal hoard amid the collapse layer of an upper-story

storeroom (Marcus Nos. 57, 61–62);

2) BBII Room 7 in an unrecorded context, but by default in the collapse of an

upper-story storeroom (No. 60);

3) BBIV-V Room 1 associated with a lion pin (HAS72-160) — Marcus lists the

context as “directly above floor level” (No. 58, Marcus 1996: 115) while the

excavator records “…on top of a few fallen bricks associated with bones which

might be of a child or children skulls [SK334]” (Hasanlu Notebook 61: 92–4);

and,

4) the Lower Court Gate Room 1 atop a stone column base (No. 59) — Marcus

does not mention that this seal was found with a lion pin (HAS60-18).

During Marcus’s study of the seals and sealings, other Hasanlu researchers usually

assessed and provided context information from the original excavation records. In the

past, such intermediary middle-range interpretation characterized the research of the

Hasanlu Project, like many other contemporary large-scale archaeological publication

projects.

Thus we see all Central Assyrian Style seals come from the Lower Court, especially

temple BBII, in upper-story storage contexts. Seal No. 58 was associated with the

fragmentary skeleton of child SK334 (skeletal elements unanalyzed): this deposit,

consisting of a large number of objects and a few scattered human remains amid fallen

brick, represents part of the upper-story collapse, and hence direct association between

the human skeleton and the seal remains uncertain.

Turning to the 15 Provincial Assyrian Style Seals, 9 (60%) were found in groups in

upper-story collapses (Nos. 63–64, 68, 70, 73–77) — Marcus (1996: 121–23) lists Seals

68, 70, and 73 as found on floors, but according to the excavation records these seals lay

“loose in fill” (Nos. 70 and 73) or definitively in second story collapse (No. 68). One seal

was found on the Low Mound surface (No. 66) and another in an excavation dump (No.

71) probably from the excavation of BBIW. This leaves Seal 65 from BBIII Room 9, for

which there are no notes beyond this, and another three seals that Marcus identifies as

found directly on the floor of the BBII temple “beside” the skeletons of high status

individuals (SK147, SK263, and SK141, respectively Seal Nos. 67, 69, and 72). Again,

this context is notoriously difficult to interpret due to the haste with which it was

excavated and recorded, and Marcus did not have all of the excavation data at her

disposal. Seal 72 (HAS60-901, Marcus 1996: 122–23, fig. 94, pl. 22), a heavily worn

stone seal, was attributed by the excavation supervisor to SK141, one of the numerous

victims found near the main (north) entrance of temple BBII Room 5. Sex was

undetermined due to the poor preservation of the skeleton, but the associated personal

ornaments, including a bead necklace, rings, bracelets, and a suspiciously high number of

lion pins — nine in total — suggests a female. There is no other recorded provenience

information for the seal, and this was a very poorly excavated and recorded area. There is

no indication the seal was found “beside” SK141, and the most obvious interpretation is

that this heavily worn/smoothed seal formed part of the necklace — the seal had a

copper/bronze suspension pin with a loop. Marcus implies it was suspended from one of

the lion pins (1996: 50), which is certainly possible, but it raises the issue of the missing

eight other pin ornaments in this lion-pin group. SK141 was lying with the cranium

“inclined, back against the back of head of Burial 13 [SK138],” another victim with

personal ornament including a bead necklace. Given the disposition of these bodies and

problematic excavation methods and recording, it is unclear with which skeleton Seal 72

was associated, and there is no record of the seal lying “beside” the body or on a building

floor. Provincial Assyrian Style Seal 67 (Marcus 1996: 120–21, fig. 89, pl. 21) was found

with a skeleton (sex unspecified) we provisionally identify as an armed and looting

enemy combatant (SK147) killed when the building collapsed, again “together with many

beads” (Marcus 1996: 120). The seal could easily be counted among the large amount of

loot associated with this individual. Finally, re-examination of the excavation records

proves Seal 69 (Marcus 1996: 121–22, fig. 91, pl. 21) was not directly associated with

SK263, nor was it on the floor — regardless, SK263 was associated with a bead necklace.

These corrections, in conjunction with the fact that no Assyrian style seals were found in

burials, let alone high status burials, proves there is very little evidence for the notion that

the Hasanlu elite wore Assyrian Style cylinder seals as status markers. In summary, most

Central Assyrian and Provincial Assyrian Style seals were stored in buildings at the time

of Hasanlu’s destruction, particularly BBII with 7 (33%) of these two categories in its

temple storerooms/treasuries. While some seals probably formed the parts of bead

necklaces and others might have served as lion pin ornaments, the majority of these

objects represent the cult paraphernalia of the deities worshipped in the Lower Court

temple complex.

Glazed Terracotta Vessels

As noted by Young in his groundbreaking study of Hasanlu ceramics (1963: 55), glazing

is quite rare in the Iron II Hasanlu ceramic assemblage (n=60) and occurs on local style

vessels as well as those of Late Assyrian origin or inspiration (Figures 4–6). The total

number of glazed vessels provided here excludes miniature, specialized vessels such as

cosmetic containers and objects variously listed as composed of “frit,” “paste,” or

“faience” in the excavation records. At the time of Young’s research, the earliest glazed

vessels belonged to the Iron II. Re-examination of the excavation records postdating

Young’s study has revealed a heretofore-unreported glazed assemblage of early Period

IVB (early Iron II) to Period IVc (Iron I) date. This material lay below the final Iron II

brick floor of the temple cella/Room 6, and is thus associated with an earlier phase(s) of

the building. These glazed vessels and sherds were found with poorly preserved ivory

fragments. As with the later Iron II glazed vessels, both local Iron I to early Iron II

vessels and foreign influences or imports are attested (Figure 7). Later Iron II glazed

vessels from the citadel destruction (n=39) are generally confined to the cultic context of

Burned Building II (n=29 or 74% of glazed Iron II citadel vessels, Figure 4). Only two

glazed vessels are known from Iron II graves (Hakemi and Rad 1950: 30–31, fig. 30

shows one), and we are aware of none from the early Iron Age occupation deposits of the

Low Mound. One small jar type predominates the BBII assemblage and was found in a

massive upper-story storeroom collapse layer at the south end of the building among the

ivory inlays and other exotica (Figure 6). Assyrian reliefs show these jars were stored on

racks, thus possibly explaining their association with ivories at Hasanlu — the remains of

decorated racks or shelves — and point to Assyria as a potential source of the jars and

possibly their unknown contents.

Sheet Metal Vessels

As de Schauensee has indicated, while many sheet metal vessels and implements at

Hasanlu appear to be Assyrian in inspiration, closer inspection belies this assumption (de

Schauensee 1988: 47). In particular, phialia and mesomphalos phialia were found in

abundance on the citadel, but also in elite graves of Hasanlu V, IVc, and IVb. While such

bowls have often been attributed to Assyrian manufacture or inspiration (Luschey 1939;

de Schauensee 1988; 49), the sheer number of phialia at Hasanlu and their early

appearance in the later LBA or Iron I (Danti 2013b) raises some issues in this regard, and

we are inclined to agree with Howes Smith (1986: 2–3) and view these bowls as part of a

broader Near Eastern tradition. Certainly Assyrian connections are attested by the

occurrence of lustration pails, although as noted by de Schauensee the proportions of the

Hasanlu pails are generally squatter (1988: 49). The single decorated lustration pail from

Hasanlu is incised with a double register of winged bulls running to the right (de

Schauensee 1988: Pl. 20). While de Schauensee compares this motif with incised garment

decorations on Assyrian reliefs, it bears a much closer resemblance to the decoration on

Urartian sheet bronze belts such as the one in Curtis, 2012, fig. 31.25-6, which is

unfortunately, like so many Urartian bronze belts, unprovenanced.

Miscellaneous Assyrica

Finally, there are some items with clear connections to Assyria from the citadel. The bone

or ivory animal-headed handle of an Assyrian style fly whisk was found within the

famous Gold Bowl along with other objects being looted by three enemy combatants,

presumably from the upper-story storerooms of BBIW, conventionally interpreted as an

elite residence (Danti In Press). Animal-headed whetstones similar to those known from

Assyrian reliefs were also used at Hasanlu, and even some of the weapons and equipment

carried and worn by the enemy combatants at Hasanlu have close ties to Assyria (Danti

In Press). These connections are intriguing, but such items are rare at Hasanlu, derive

from very different contexts, and were in wide circulation in the early Iron Age Near

East: it is critical to note that the depiction of an object type in Assyrian reliefs does not

make an item Assyrian in origin or necessarily assyrica in the emic perspective.

What’s Missing?

As many have commented, it is extremely difficult to determine the mechanisms by

which Assyrian objects were transmitted to Hasanlu, and even more difficult to parse out

the ways in which the craftsmen working in the Local Style had access to the motifs and

styles of Assyrian artistic production. While there are numerous Assyrian texts that

illuminate the relationship between the Urmia region and Hasanlu from a purely Assyrian

perspective, there are few examples of writing from Hasanlu itself, and each extant

example is an inscription on a portable object. The lack of writing at Hasanlu, as well as

the fact that none of the sealings found in the citadel were made by Central and

Provincial Assyrian seals, certainly suggests that the settlement was well outside the

sphere of direct Assyrian influence or involvement.

There are any number of possible pathways for the indirect transmission of Assyrian

objects and motifs. One likely mode for the transmission of Assyrian motifs is through

the medium of textiles, which are portable and well documented as goods traded by

Assyria. Unfortunately, while there is evidence for textiles in the storage rooms on the

Citadel, they are not well enough preserved (Love 2011). In any case, the emulation of

Assyrian motifs at Hasanlu was highly selective, and examples of Assyrian imperial

iconography are conspicuously absent. There are no depictions of the state god Assur or

signs of Assyrian religious belief or ritual and apotropaic magic attested among the few

terracotta figurines and amulets. Wall paintings are absent and glazed bricks were not

used in any significant number in the excavated areas of the settlement. The only possible

exception is a single Assyrian style ivory (HAS64-1047; MMA 65.163.2a, b; 3a, -c from

BBII) that appears to depict a wingless genius holding a horned animal, again, a portable

object that could have passed through many hands before it found its way into a

storeroom at Hasanlu.

Summary and Conclusions

Across the diverse range of Hasanlu Period IVb contexts, we see that assyrica are

concentrated in Hasanlu’s monumental temple BBII, and by increasingly lesser degrees

the Lower Court area and finally the citadel as a whole. The assyrianizing and ‘north

syrianizing’ character of Hasanlu’s Lower Court temples was quite deliberate — when

we use these terms we are not merely referring to material culture but entire monumental

contexts. The questions remains as to why? The answer lies somewhere below the Period

IVb destruction level in the unexcavated Iron I and Late Bronze Age levels — the periods

in which this cultic complex emerged.

To our mind, the cultic context of assyrica raises some issues with previous

interpretations of the role of Assyrian material culture within the local milieu. First and

foremost we must remember that Hasanlu IVb was the product of 400–500 years of

development, and that the structures of the citadel were centuries old and have Iron I or

later Late Bronze Age precursors. The destruction of the Iron I site by fire surely resulted

in the loss of material culture, but it is apparent that much also survived. In this vein, we

see many of the so-called heirloom items of Hasanlu IVb, such as the Gold Bowl and the

mosaic glass vessel, as possible relicts of earlier treasuries — there are few obvious

heirlooms in the Period IVb destruction level, the Iron I destruction by fire surely reduced

their numbers (recall the ivory fragments and glazed vessels fragments from the Iron I

cella of BBII). A steady stream of Assyrian and North Syrian material culture was

probably arriving at Hasanlu in the later LBA and Iron I. Thus, the Hasanlu Local

Style(s), like the Hasanlu citadel(s), developed over centuries as the product of close ties

to Mesopotamia, especially Assyria, as well as other neighboring regions.

To return to the point raised by Porada, the local style originates in the later 2nd

millennium BC. Seen another way, it emerged in tandem with the Middle Assyrian style,

and both Middle Assyrian and the Hasanlu Local Style share common Late Bronze Age

influences. More importantly, the Hasanlu assyrica are concentrated in an

assyrianizing/’north syrianizing’ built environment that was archaizing by the time of

Hasanlu’s Period IVb destruction. We don’t see such connections elsewhere in the Lake

Urmia Basin at Kordlar, Geoy, Haftavan, and Masjid-e Kabud, or further afield at

Zendan. The Hasanlu temple complex appears to be a focal point, and we would argue

this suggests Ushnu-Solduz was a focal point. Understanding how this relates to the

intervening buffer states immediately west of Ushnu-Solduz will be difficult to gauge

until we fill in archaeological gaps in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Sources Cited Basello, Gian Pietro. 2012. “Doorknobs, Nails or Pegs? The Function(s) of the Elamite and Achaemenid Inscribed Knobs.” In Gian Pietro Basello and Adriano V. Rossi (eds.) Dariosh Studies II. Persepolis and its Settlements: Territorial System and Ideology in the Achaemenid State (Napoli: Università à degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”), pp. 1–66. Cifarelli, Megan. 2013. “The Personal Ornaments of Hasanlu VIb–IVc.” In Michael D. Danti, Hasanlu V: The Late Bronze and Iron I Periods. Hasanlu Excavation Reports 3. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology), pp. 313–22. Collins, Paul. 2006. “An Assyrian-Style Ivory Plaque from Hasanlu, Iran.” Metropolitan Museum Journal Vol. 41: 19–31. Curtis, John E., ed. 1988. Bronze-Working Centres of Western Asia c. 1000–539 B.C. New York: Kegan Paul. Curtis, John E. 2012. “Assyrian and Urartian Metalwork: Independence or interdependence.” In S. Kroll, C. Gruber, U. Hellwag, M. Roaf & P. Zimansky (eds.) Biainili-Urartu (Leuven: Peeters), 427–443. Danti, Michael D. In Press. “The Hasanlu Gold Beaker in Context: All That Glitters…” To appear in Antiquity. _____. 2011. “The ‘Artisan’s House’ of Hasanlu Tepe, Iran,” Iran XLIX: 11–54. _____. 2013a. “The Late Bronze and Early Iron Age in northwestern Iran,” in Daniel T. Potts, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 327–76. _____. 2013b. Hasanlu V: The Late Bronze and Iron I Periods. Hasanlu Excavation Reports 3. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology). Danti, M. and Cifarelli, M. In Press. The warrior graves at Hasanlu, Iran. Iranica Antiqua (To appear in 2015). de Schauensee, M. 1988. “Northwest Iran as a bronze-working centre: The view from Hasanlu. “ In J. E. Curtis (ed.), Bronzeworking-Centres of Western Asia c. 1000-539 B.C. (London: Keegan Paul International), pp. 45–62. ______. 1989. “Horse Gear from Hasanlu.” Expedition 31/2–3: 37–52.

de Schauensee, Maude, ed. 2011. Peoples and Crafts in Period IVB at Hasanlu Tepe, Iran. University Museum Monograph 132. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology). Durand, J.-M. 2005. Le culte des pierres et les monuments commémoratifs en Syrie amorrite. Florilegium marianum 8. (Paris: SEPOA). Dyson, Robert H., Jr. _____. 1989. “The Iron Age Architecture at Hasanlu: An Essay.” Expedition 31/2–3: 107–27. Dyson, Robert H., Jr. and Mary M. Voigt. 2003. “A Temple at Hasanlu.” In Naomi F. Miller and Kamyar Abdi (eds.) Yeki Bud, Yeki Nabud. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph 48 (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology), pp. 219–36. Hakemi, A. and R. Mahmud. 1950. Rapport et resultats de fouilles scientifques à Hasanlu, Solduz. Guzarishha-yi bastan-shinasi 1: 87–103. Herrmann, Georgina. 2012. “Some Assyrianizing ivories found at Nimrud: could they be Urartian?” In S. Kroll, C. Gruber, U. Hellwag, M. Roaf & P. Zimansky (eds.) Biainili-Urartu (Leuven: Peeters), pp. 339–50. Howes Smith, P. H. G. 1986. “A Study of 9th–7th Century Metal Bowls from Western Asia.” Iranica Antiqua XXI: 1–88. Hutter, M. 1993. Kultstelen und Baityloi. Die Ausstrahlung eines syrischen religiösen Phänomens nach Kleinasien und Israel. In B. Janowski, K. Koch, and G. Wilhelm (eds.), Religionsgeschichtliche Beziehungen zwischen Kleinasien, Nordsyrien und dem Alten Testament. OBO 124. (Freiburg/Göttingen: Universitätsverlag/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 87–108. Layard, A.H. 1849. The Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray. Love, Nancy. 2011. “The Analysis and Conservation of the Hasanlu IVB Textiles.” In M. de Schauensee (ed.) Peoples and Crafts in Period IVB at Hasanlu Tepe, Iran (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum), pp. 43–56. Luschey, Heinz. 1939. Die Phiale. (Bleicherode am Harz: C. Nieft). Marcus, M. 1989. “The Seals and Sealings from Hasanlu IVb.” Expedition 31/2–3: 53–63. ———. 1991. “The Mosaic Glass Vessels from Hasanlu, Iran: A Study in Large-Scale Stylistic Trait Distribution.” Art Bulletin 73: 536–60.

_____. 1994. “In his lips he held a spell.” Source: Notes in the History of Art (Essays for Edith Porada) 13: 9–14. ———. 1996. Emblems of Identity and Prestige: The Seals and Sealings from Hasanlu, Iran’ University Museum Monograph 84. Hasanlu Special Studies 3. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum). Muscarella, Oscar White. 1980. The Catalogue of Ivories from Hasanlu, Iran, University Museum Monograph 40. Hasanlu Special Studies 2. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum). ———. 2006. “The Excavations of Hasanlu: An Archaeological Evaluation.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 342: 69–94. Nunn, Astrid.1988. Handbuch der Orientalistik: Die Wandmalerei und der glasierte Wandschmuck im Alten Orient. Volumes 1–2; Volume 6 (Leiden: E. J. Brill). Pope, Arthur Upham (Ed.). 1967. A Survey of Persian Art (New York: Oxford University Press). Porada, Edith. 1959. “The Hasanlu Bowl.” Expedition 1: 18–22. ———. 1965. Ancient Iran. (London: Methuen). ———. 1967. “Notes on the Gold Bowl and Silver Beaker from Hasanlu.” In Arthur Upham Pope (Ed.) A Survey of Persian Art (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 2971–2978. Tourtet, Françelin. 2011. “Distribution, Materials and Functions of the ‘Wall Knobs’ in the Near Eastern Late Bronze Age: From South-Western Iran to the Middle Euphrates.” In Katrien De Graef and Jan Tavernier (eds.) Susa and Elam. Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives. Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009. Mémoires de la Délégation en Perse 58. (Leiden: E. J. Brill), pp. 173–190. Winter, Irene J. 1977. “Perspective on the ‘Local Style’ of Hasanlu IVb: A Study in Receptivity.” In Louis D. Levine and T. C. Young, Jr. (eds.) Mountains and Lowlands: Essays in the Archaeology of Greater Mesopotamia. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 7 (Malibu: Undena), pp. 371–386. Young, T. Cuyler, Jr. 1963. Proto-Historic Western Iran, an Archaeological and Historical Review: Problems and Possible Interpretations. PhD diss., University of Penn-sylvania, Dept. of Anthropology. Philadelphia.

Captions

Figure 1. The Iron II Citadel of Hasanlu Tepe (11 Meter Grid). Figure 2. Hasanlu Tepe: The distribution of glazed terracotta and copper/bronze wall tile

and wall plaques in the southern Iron II Citadel Figure 3. Hasanlu Tepe: The distribution of ivories in the southern Iron II Citadel. Figure 4. Hasanlu Tepe: The distribution of glazed terracotta vessels in the southern Iron

II Citadel. Figure 5. Hasanlu Tepe: Glazed terracotta vessels from the Iron II destruction level. Figure 6a (top). Assyrian relief depicting vessels (Figure 6b, bottom) similar to glazed terracotta jars from the Iron II destruction level of Hasanlu BBII (Figure 6b). Figure 6a from Layard 1849: Pl. 30. Figure 7. Hasanlu Tepe: Glazed terracotta vessels of the Iron I to early Iron II from below

the floor of the BBII temple cella (Room 6).

20 10

Mudbrick Wall

Bench

20MN

BB VII

BB VI South

BB VII East

BB III

BB VIII

Stair

Stair

6

BB I West

BBV

BBIV-V

BB IV East

BB IV

BB IIBB X

BB IEast

Lower Court

UpperCourt

Lower CourtGate

BB IX

3

6

11

BB VI North

Figure 1

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

23 24 25 26

27 28 29 30 31 32 33

2221

23 24 25 2627 28

29 30 31 32 332221

W

X

AA

Z

BB

CC

DD

Y

I

VIC

Modern Village of Hasanlu

Modern Village of Hasanlu

Canal1520

510

1520

510

5

1 Meter Contour IntervalHASANLU TEPE

LILIV

X

VI

V

LIII

IV

LII

Low Mound

North Cemetery

Excavation Unit

O

N

M

High Mound

V

W

X

AA

Z

BB

CC

DD

Y

South Street

20

1020

M

NStair

Stair

6

BB

I W

est

BB

V

BB

IV-V

BB

IV E

ast

BB

IV

BB

IIB

B X

BB

IEa

st

Low

er

Cou

rtU

pper

Cou

rt

Low

er C

ourt

Gat

e

BB

IX

3

2728

2930

3132

33

2425

2627

2829

3031

3233

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

21

3

23

1

2

11 8

1

933

Figure 2

20

1020

M

NStair

Stair

6

BB

I W

est

BB

V

BB

IV-V

BB

IV E

ast

BB

IV

BB

IIB

B X

BB

IEa

st

Low

er

Cou

rtU

pper

Cou

rt

Low

er C

ourt

Gat

e

BB

IX

3

2728

2930

3132

33

2425

2627

2829

3031

3233

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

9

3

99

5

21120

589

31

Figure 3

20

1020

M

NStair

Stair

6

BB

I W

est

BB

V

BB

IV-V

BB

IV E

ast

BB

IV

BB

IIB

B X

BB

IEa

st

Low

er

Cou

rtU

pper

Cou

rt

Low

er C

ourt

Gat

e

BB

IX

3

2728

2930

3132

33

2425

2627

2829

3031

3233

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

V W X AA

Z BB

CC

DD

Y

212

2

1

2

11 23

2

Figure 4

64-312

70-D25

64-310 64-103

64-?

64-114

64-319

64-15364-113

64-30664-104

64-661

64-458

64-155

BBII Room 2

0 5 cm

62-509

62-583

64-694

72-N84

62-85464-56

60-230

58-521

BBII Room 2

Figure 5